Abstract

The observation that Th17 infiltration in ovarian cancer correlates with markedly improved survival has prompted the question of whether ovarian tumor antigen-specific Th17 responses to could be stimulated by tumor vaccination. Dendritic cells treated with IL-15 and an inhibitor of p38 MAPK signaling (DCIL-15/p38inhib) bias T cell responses toward a Th1/Th17 phenotype, raising the prospect of therapeutic vaccination, but significant barriers remain. Tumor vaccines, including DC vaccination, usually stimulate immune responses, but the lack of clinical responses in cancer patients has been disappointing. Possible reasons may include an inability of anti-tumor T cells to migrate into the tumor microenvironment, and an inability of T cells to retain effector function in the face of tumor-associated immune suppression. We found that ovarian tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cells induced by DCIL-15/p38inhib migrated in response to CXCL12 and CCL22 (both highly expressed in ovarian cancer), and ascites CD14+ myeloid cells. Cocultures showed that ascites CD14+ cells markedly suppressed antigen-specific CD4+ T responses, but suppression could be alleviated by treatment with anti-IL-10 or inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). These results suggest that the efficacy of DC vaccination against ovarian cancer may be boosted by agents that inhibit tumor-associated CD14+ myeloid cell suppression or IDO activity.

Keywords: ovarian cancer; ascites myeloid cells; interleukin 10; indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase; CD4+ T cells

Introduction

Ovarian tumors avail themselves of multiple mechanisms of immune evasion, thus blunting the efficacy of therapeutic vaccination or immunotherapy. Infiltration of regulatory T cells (Treg) confers immune privilege and is associated with a poor prognosis and increased mortality1,2. Further mechanisms include expression of B7-H1 and IDO, both of which correlate independently with increased morbidity and mortality in ovarian cancer patients3,4,5. In sharp contrast, ovarian tumor expression of IL-17 (produced by infiltrating Th17 T cells) correlates with markedly prolonged overall survival among ovarian cancer patients6, leading to the question of whether Th17 cells could be induced or expanded to therapeutic advantage7,8. Recent studies have shown that treatment of ovarian tumor antigen-loaded, cytokine-matured dendritic cells (DC) with IL-15 and a p38 MAPK inhibitor (designated DCIL-15/p38inhib) enhances ERK phosphorylation and biases human CD4+ T cell responses toward a Th1/Th17 phenotype that correlates with strong CD8+ CTL activation9.

Although DC vaccines designed to stimulate Th17 immunity in ovarian cancer patients may hold potential for clinical benefit, a critical question is whether DC-stimulated T cell responses would be abrogated by immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. To address this question, we tested whether coculture of DCIL-15/p38inhib-induced CD4+ T cells with autologous tumor-associated ascites lymphoid or myeloid cell populations inhibits responses to antigen stimulation. DCIL-15/p38inhib-stimulated CD4+ T cells were chemo-attracted by ascites CD14+ myeloid cells and by CXCL12 and CCL22, both of which are present in abundance in ovarian tumor ascites. CD4+ T cell responses were reproducibly inhibited by ascites CD14+ cells. Suppression could be alleviated by inhibition of IDO or blockade of IL-10, but not by blockade of B7-H1 or TGFβ. Addition of IL-2 independently enhanced CD4+ T cell responses to antigen stimulation in the presence or absence of ascites CD14+ cells, but IL-2 did not provide further enhancement of CD4+ T cell responses when combined with anti-IL-10 and IDO inhibition. Collectively, these observations suggest that adjuvant treatments that inhibit IDO, or modulate myeloid cell function may enhance immune response and clinical benefit following DCIL-15/p38inhib vaccination in ovarian cancer patients.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects

Ovarian cancer patients were recruited from patients attending the Women’s Oncology clinic in the Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, under an IRB-approved protocol. Ovarian tumor ascites samples were recovered and blood samples were drawn at the time of surgery.

Lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL)

Epstein-Barr virus-transformed LCL were established from peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) by infection with the B95.8 strain of Epstein-Barr virus, as described9.

Dendritic cell and T cell culture

DC were prepared from plastic-adherent PBL and cultured in the presence of IL-15 and a p38 MAPK inhibitor (Calbiochem/EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) as described9. DC stimulation of peptide tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses was also performed as described9. Ovarian tumor antigens used for T cell stimulation were peptides from CA125, hepsin, matriptase, or a variant of tumor-associated differentially expressed gene 14 (TADG-14v) (Supplemental Digital Content, Table S1)10,11,12.

Cell separation

Ovarian tumor ascites cell populations were separated with magnetic columns, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA). After recovery of CD14+ cells, Treg were recovered with a CD25+CD49d− Treg isolation kit (Miltenyi). First, effector T cells expressing CD8 and/or CD49d were selected (depletion of CD49d+ cells removes contaminating CD25+ effector T cells). Second, CD25+ cells were separated from the remaining CD8−/49d− cells. The purity of the CD14+ ascites cell fraction was typically 95–98% (not shown).

ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were performed, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R & D systems, Minneapolis, MN; eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Ascites CD14+ cells were incubated in DC medium (CellGenix, Antioch, IL) for two days, supernatants were harvested and ELISA was performed for CCL22, CXCL12 and IL-10. Ascites fluids were also assayed for CCL22 and CXCL12.

Migration assays

Migration assays were performed in 24-well Costar plates with 5.0 μm polycarbonate membrane transwells (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). The transwell membranes were incubated overnight at 4° C with 20 μg/ml human fibronectin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in PBS; 100 μl of fibronectin solution was added to the upper chamber and 350 μl to the lower chamber. On the second day, excess fibronectin was aspirated, and the upper and lower chambers were washed once with PBS. Human vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) (CRL-1730, ATCC, Manassas, VA) were added to the upper chambers at 5 × 104/well in 100 μl of F12K medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum medium (Valley Biomedical, Winchester, VA), 50 μg/ml endothelial cell growth supplement (BD Biosciences) and 0.1 mg/ml heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). 400 μL of the supplemented F12K medium was added to the lower chambers. HUVEC-coated transwells were incubated at 37°C in 7% CO2 for two days to reach confluence.

CD14+ ascites cells (1 × 106/well in DC medium) were placed in 24-well Costar plates and incubated at 37°C in 7% CO2 for two days, after which the HUVEC-coated transwell upper chambers were placed in the Costar wells. Upper and lower chambers were drained and 8 × 105 T cells were added to the upper chambers in 100 μl DC medium, with 400 μl of DC medium placed in the lower chambers. Where appropriate, chemokines (CXCL12 and CCL22, R & D Systems) were added to lower chambers at 5 ng/ml, and anti-CCL22 antibody (R & D Systems) was added to lower chambers at 20 μg/ml. Quadruplicate cell counts from the lower chambers were taken after 4 hours.

Coculture assays

Ovarian tumor antigen-specific, DC-stimulated CD4+ T cells were cultured with ovarian tumor ascites cell populations, either in direct contact or in transwell cocultures in which cell contact was prevented by 0.4 μm polycarbonate membranes (Corning). Autologous ascites CD14+ cells, CD8+/CD49+ effector phenotype T cells, CD4+/CD25+ Treg, CD4+/CD25− T cells (5 × 105/well in 500 μl RPMI/10Hu), cell-free ascites fluid (250 μl + 250 μl of RPMI/10 Hu) or medium only were placed in the wells. Tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cells were stained with PKH26 dye (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and 1 × 106 CD4+ T cells in 200 μl RPMI10/Hu were added directly to the wells or to the upper chamber of the transwell cocultures. After incubation for 2 days at 37°C, peptide antigen-loaded, irradiated (7,500 cGy) autologous LCL (2.5 × 105 in 50 μl RPMI10/Hu) and Brefeldin A (3 μg/ml total volume) were added to each contact coculture, or to the upper chamber of the transwell cocultures. After a further overnight incubation, PKH26-labeled CD4+ T cells were harvested for functional assays. Where indicated, 10 μg/mL anti-IL-10, anti-TGFβ or anti-B7-H1 antibodies (R & D Systems) or 200 μM 1-methyl tryptophan (Sigm-Aldrich) were added at the initiation of the cocultures and added at the time of antigen stimulation with peptide-loaded LCL (i.e., two treatments, at day 0 and day 2).

Flow Cytometry

The following reagents and fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies were used in this study for T cell phenotypic and functional analyses: PKH26 membrane dye (Sigma), APC- anti-CD4, APC-anti-CD8a, PE-anti-CD4, PE-anti-CD25, FITC or APC-anti-TNFα, PE-anti-ICOS-L FITC-Annexin-V (all from eBioscience), FITC-anti-CXCR4, APC-anti-CXCR7, PE-anti-hCCR4 (all from R&D Systems), and FITC-anti-CD279/PD-1 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Intracellular expression of TNFα was detected following fixation and permeabilization (fixation/permeabilization buffer concentrate, Cat. No. 00-5123-43, diluent, Cat. No. 00-5223-56, and permeabilization buffer, Cat. No. 00-8333-56, all from eBioscience). All samples were analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer, using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). For analysis of tumor ascites CD14+ cell phenotype, the following monoclonal antibodies were used: FITC-anti-CD14, PE-anti-CD11b (both from R & D Systems), PE-anti-CD11c, PE-anti-B7-H1, PerCP-anti-CD14 (all from BD Biosciences), FITC-anti-CD279/PD-1, FITC-anti-CD83, FITC-anti-CD80, PE-anti-CD86, APC-anti-CD14, and PE-IL-1β (all from eBioscience). Intracellular expression of IL-1β was assayed following overnight incubation of CD14+ cells in the presence of Brefeldin A, followed by fixation and permeabilization as described above.

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase assay

Purified ascites CD14+ cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in RPMI10/Hu supplemented with 100 μM tryptophan. Production of kynurenine, the first stable metabolite of tryptophan downstream of IDO, was measured by spectrophotometry as described13.

Statistics

Data are displayed with error bars representing one standard deviation. Significance was calculated through one-way analysis of variance.

Results

CCL22 and CXCL12 expression in ovarian tumor ascites

ELISAs for CCL22 and CXCL12 expression in a set of nine primary ovarian tumor ascites fluids showed that both CCL22 and CXCL12 were present at high levels in all samples tested (Supplemental Figs. S1A & S1C). Further analysis revealed that the majority of primary ascites tumor and solid tumor cell cultures expressed both CCL22 and CXCL12 (Supplemental Figs. S1B & S1D). Ascites CD14+ cells consistently expressed CCL22 (Supplemental Fig. S1E) in primary culture supernatants, but CXCL12 expression by ascites CD14+ cells was not detected (not shown).

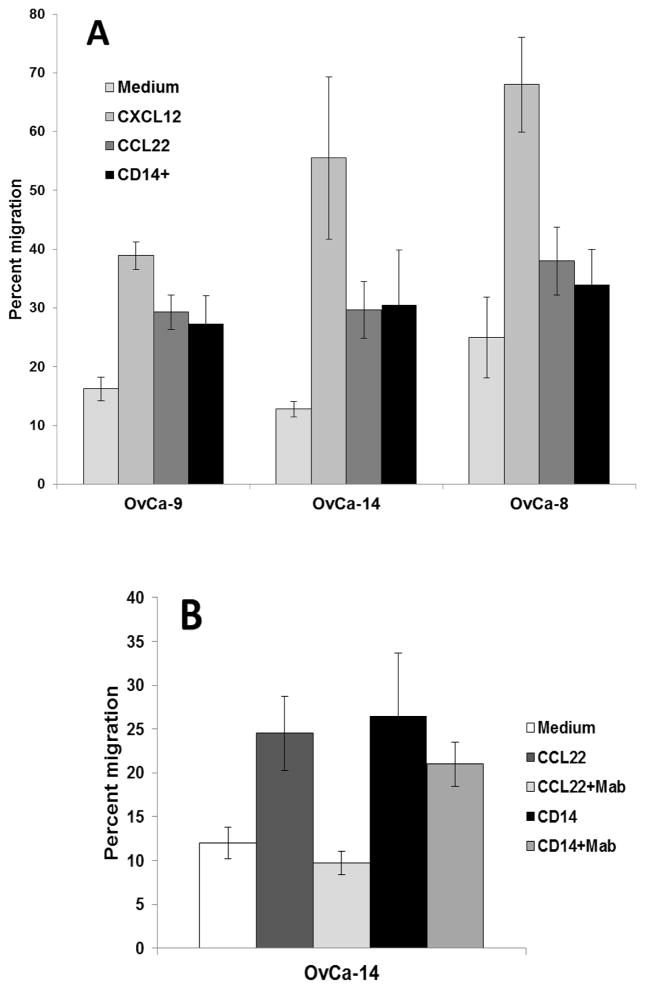

Migration of tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in response to CCL22, CXCL12 and primary ascites CD14+ cells

The migratory capacity DC-stimulated tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cells was tested in a transwell co-culture system in which a confluent monolayer of primary human vascular endothelial cells was established on 5.0 μm pore size polycarbonate membranes. CD4+ T cells migrated across vascular endothelium in response to CCL22 or CXCL12, and showed significant migration (p < 0.03) in response to soluble factors expressed by autologous tumor ascites CD14+ cells from patients OvCa-9 and OvCa-14 (Fig. 1A). CD4+ T cells also showed limited, but not statistically significant, migration in response to ascites CD14+ cells from patient OvCa-8. These observations suggested that ascites CD14+ cells would preferentially attract effector CD4+ T cells by secretion of CCL22. However, transwell coculture in the presence of anti-CCL22 antibodies did not significantly inhibit CD4+ migration across vascular endothelium in response to ascites CD14+ cells (p > 0.19) (Fig. 1B), indicating that other soluble factors mediate ascites CD14+ cell chemoattraction of CD4+ T cells.

Figure 1.

(A) Migration of DC-stimulated ovarian tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cells across 5.0 μm pore size transwells overlaid with primary human vascular endothelium monolayers in response to CXCL12, CCL22 or ascites CD14+ cells. CD4+ T cells were placed in the upper chamber, and chemokines or ascites CD14+ cells were placed in the lower chamber. Fourfold replicate counts of CD4+ T cells in the lower chamber were taken after 4 hours. (B) CD4+ T cell chemoattraction by ascites CD14+ cells is not significantly inhibited by antibodies to CCL22.

Phenotype of ascites tumor-associated cell populations

Myeloid cells and T cells constitute the two most abundant ovarian tumor-associated cell populations. The majority of myeloid cells were CD14+ and co-expressed CD11b, CD11c, low levels of CD80, CD86 and CD83 (Supplemental Fig. S2). Most CD14+ cells also expressed B7-H1 and PD-1, which have been reported to be co-expressed by ovarian tumor-associated DC that mediate immune suppression14, and a variable minority of ascites CD14+ cells co-expressed ICOS-L (Supplemental Fig. S2). For all patients tested, a minority of CD14+ cells expressed IL-1β, and in the case of OvCa-8, a discrete subset of CD14hiIL-1β+ cells was observed. Ovarian ascites CD3+ T cells were distributed between CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, with a low frequency of CD4+CD25+ T cells of regulatory T cell phenotype (Supplemental Fig. S2). Several T cell populations were recovered, including CD8+CD49d+ effector T cells, CD4+CD25+ T cells and CD4+CD25− T cells. The populations recovered with CD8 and CD49d antibody-coupled beads included high proportions of CD4+ T cells that presumably also expressed the CD49d effector cell marker (Supplemental Fig. S3). Subsequent purification of CD25+ T cells recovered predominantly CD4+ T cells, but with variable levels of CD25 expression (Supplemental Fig. S3).

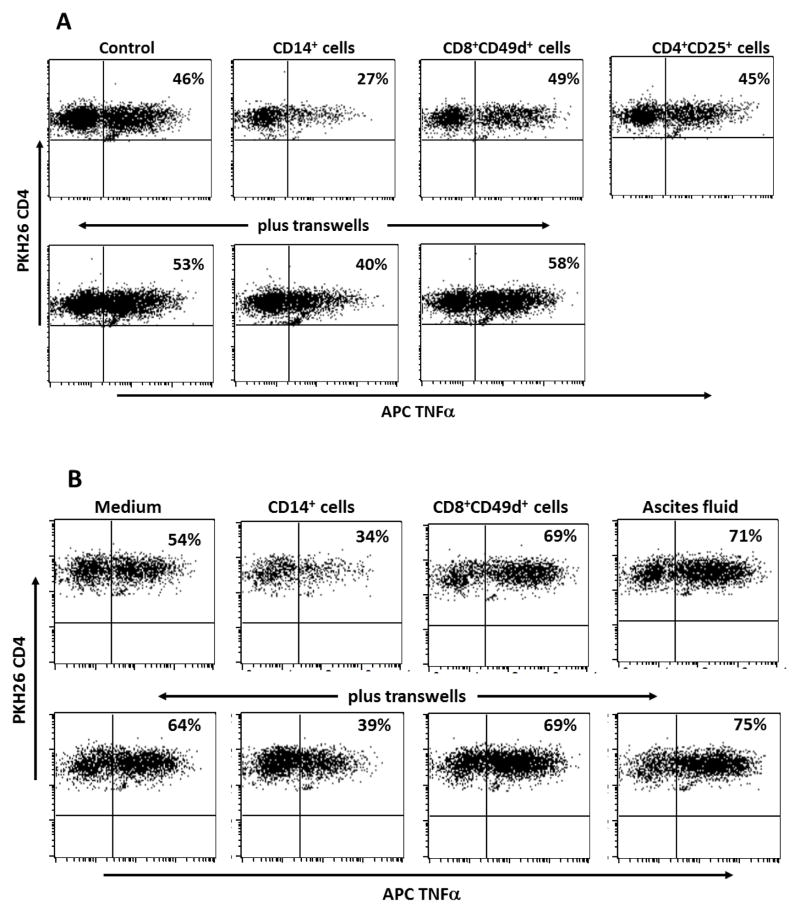

Ascites CD14+ cell suppression of CD4+ T cell responses by soluble factors

DC-stimulated CD4+ T cells from patient OvCa-8 were PKH26-tagged and cocultured for 48 hours in direct contact or in transwells with ascites–derived autologous CD14+ cells, CD8+CD49d+ effector T cells, CD4+CD25+ regulatory phenotype T cells, CD4+CD25− helper T cells, or cell-free ascites fluid. CD4+ T cell responsiveness to antigen stimulation was determined by flow cytometric analysis of intracellular TNFα expression following overnight addition of peptide-loaded autologous LCL. Replicate cocultures indicated that soluble factors mediated immune suppression by CD14+ cells, as T cell responses were inhibited in contact cocultures and to a variable extent in transwell cocultures (Figs. 2A & B). The lack of suppression by tumor-associated Treg was reproducible for all patients tested (n = 4). Cell-free ascites fluid was not immunosuppressive – if anything, CD4+ T cell responses were slightly enhanced. There was no evidence of CD4+ T cell apoptosis following coculture with ascites cell populations, as determined by Annexin V staining (not shown).

Figure 2.

CD4+ T cell responsiveness to antigen stimulation following contact or 0.4 μm pore size transwell coculture with ascites CD14+ macrophages. Patient OvCa-8 DC-stimulated CD4+ T cells specific for ovarian tumor antigen hepsin (peptide 48–84) were cocultured for 48 h with autologous ascites CD14+ cells, CD8+CD49d+ T cells, CD4+CD25+ T cells, or ascites fluid, and then stimulated by overnight addition of antigen-loaded autologous LCL to the cocultures. Effector CD4+ T cells were identified by expression of PKH26 and responses to antigen stimulation were determined by flow cytometric analysis of intracellular TNFα expression. Representative results from two independent experiments (A and B) are presented with responder CD4+ T cells gated on PKH26 (FL2) staining.

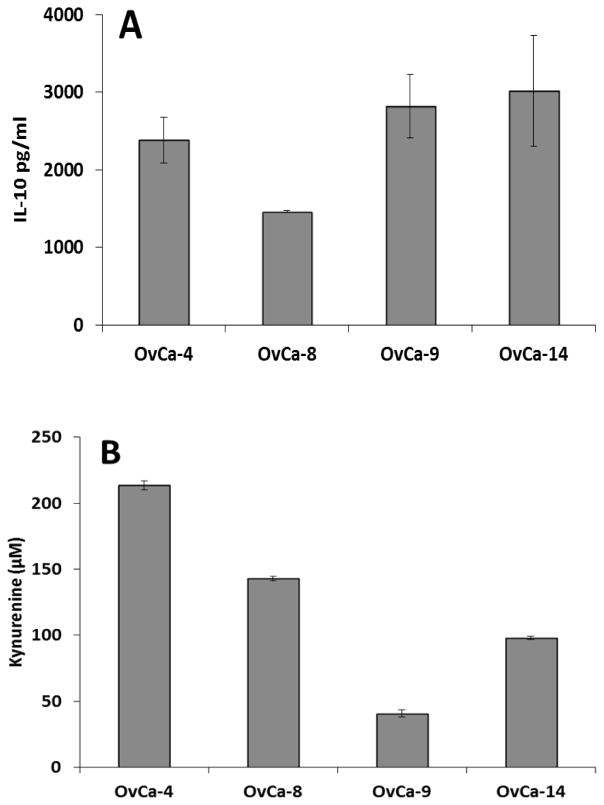

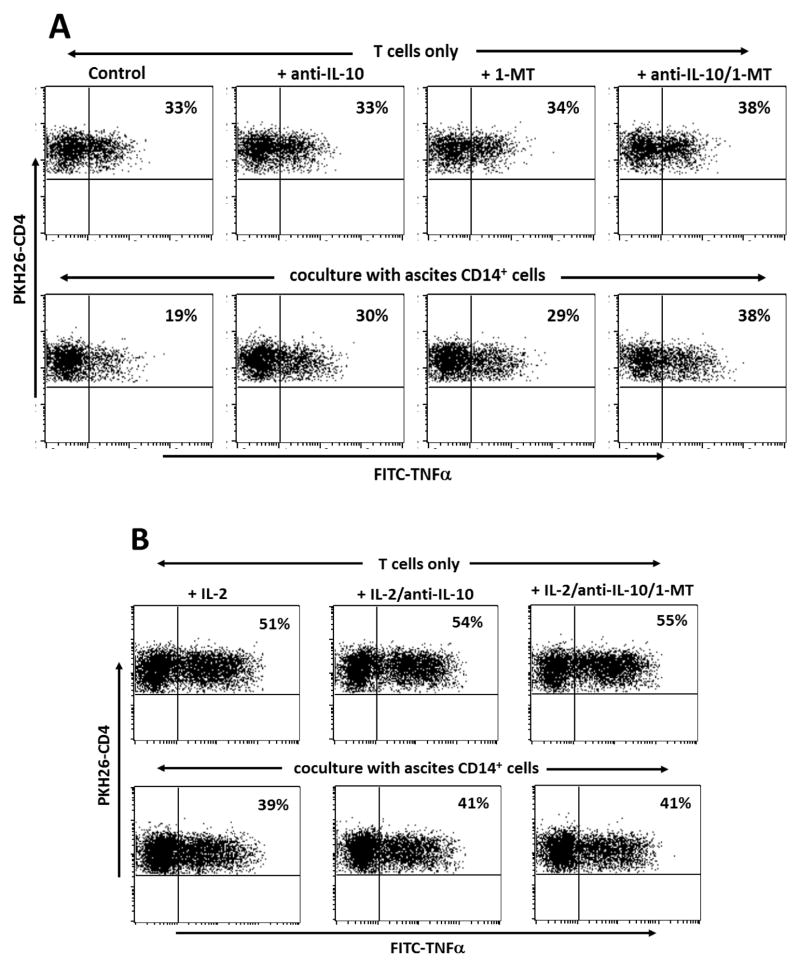

Mechanisms of immune suppression by ovarian tumor ascites CD14+ cells

We have previously reported that ovarian tumor ascites fluids contain increased levels of IL-10 and TGFβ15. Ascites CD14+ cells consistently expressed high levels of IL-10 (Fig. 3A) and showed evidence of IDO activity, as measured by production of kynurenine (Fig. 3B). Addition of anti-IL-10 antibody or 1-methyl tryptophan to cocultures with DC-stimulated antigen-specific CD4+ T cells alleviated immune suppression (Fig 4A). Treatment with both anti-IL-10 and 1-methyl tryptophan in combination further enhanced the T cell response to antigen stimulation, but the gain was additive rather than synergistic. Addition of anti-TGFβ antibodies had no impact on CD14+ cell suppression of CD4+ T cell responses (not shown).

Figure 3.

(A) Expression of IL-10 by ascites CD14+ cells. (B) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity in ascites CD14+ cells, measured by production of kynurenine [23].

Figure 4.

(A) Inhibition of tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses by ascites CD14+ cells is blocked by anti-IL-10 antibodies or addition of 1-methyl tryptophan (a competitive inhibitor of IDO activity). Patient OvCa-4 CD4+ T cells specific for ovarian tumor antigen hepsin (peptide 48–84) were cocultured for 48h with autologous ascites CD14+ cells and then stimulated by overnight addition of antigen-loaded autologous LCL. (B) Antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses are enhanced by IL-2 (50 U/mL, added at initiation of the cocultures) in the presence or absence of ascites CD14+ T cells. Effector CD4+ T cells were identified by expression of PKH26 and responses to antigen stimulation were determined by flow cytometric analysis of intracellular TNFα expression following overnight stimulation with antigen-loaded autologous LCL. Results are presented with responder CD4+ T cells gated on PKH26 (FL2) staining.

Given that ascites CD14+ cells consistently express B7-H1, further experiments were conducted with anti-B7-H1 blocking antibodies. Cocultures with ascites CD14+ cells from patients OvCa-4 and OvCa-8 showed some restoration of CD4+ T cell responses following B7-H1 blockade, but collectively these results did not provide strong evidence of a major role for B7-H1 in immune suppression by ascites CD14+ cells (Supplemental Fig. S4). This was perhaps unsurprising, as PD-1 expression by DC-stimulated CD4+ T cells is reproducibly low to negligible (Supplemental Fig. S5). In the event that anti-tumor T cells express higher levels of PD-1, it is possible that greater sensitivity to B7-H1 inhibition would be observed.

Enhancement of CD4+ T cell responses by IL-2

Treatment with IL-2 markedly enhanced antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses following coculture with ascites CD14+ cells, but the response was still at least partly suppressed relative to cultures of T cells only (Fig. 4B). These observations suggest that IL-2 serves to boost CD4+ T cell antigen responsiveness, but does not impart intrinsic resistance to ascites CD14+ cell-mediated immune suppression, or have any direct action on ascites CD14+ cells. The combination of IL-2 treatment with anti-IL-10 or anti-IL-10 plus 1-MT did not result in any further gain in CD4+ T cell responses. Although it is possible that IL-2 inhibits IL-10 or IDO expression by ascites CD14+ cells, the weight of evidence indicates that the actions of IL-2 on the one hand, and anti-IL-10 or 1-MT on the other, are complementary at the T cell level and the CD14+ cell level, respectively.

Discussion

The finding that Th17 infiltration of ovarian tumors positively predicts patient outcomes suggests that tumor vaccines or immunotherapies that induce Th17 responses may be of therapeutic benefit for ovarian cancer patients. We have recently reported that treatment of cytokine-matured DC with a combination of IL-15 and inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling biases DC-driven ovarian tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses towards a Th1/Th17 phenotype, while diminishing CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg activation9. The ability to stimulate a Th1/Th17-biased antigen-specific CD4+ T cell response is encouraging, but for DCIL-15/p38inhib vaccination to be effective, anti-tumor T cells need to retain effector function in the face of multiple mechanisms of immune suppression.

In this paper, we show that primary ovarian tumor ascites CD14+ myeloid cells consistently inhibited CD4+ T cell responses to antigen stimulation. Ascites CD14+ cells expressed IDO, IL-10, B7-H1 and ICOS-L, all of which may contribute to immunoregulatory function. IDO in particular is widely held to play a pivotal role in regulating the Treg:Th17 balance16,17, and costimulation by ICOS-L-expressing pDC has recently been reported to promote Treg expansion in ovarian cancer18. However, involvement of ICOS-L in Treg expansion may be dependent on context, as ICOS costimulation also supports differentiation and expansion of human Th17 responses19. CD4+ effector T cells stimulated by DCIL-15/p38inhib express low but detectable levels of ICOS (not shown), but the contribution, if any, of ICOS-L to immune suppression by ascites CD14+ cells is not known. Ovarian tumor-associated macrophages can also promote Th17 responses by an IL-1β-dependent mechanism6, and thus the Treg:Th17 balance in the ovarian tumor microenvironment may be influenced by the predominance of IL-1β expression (pro-inflammatory) versus IL-10 expression and IDO activity (anti-inflammatory). We found that a minority of ascites CD14+ cells consistently expressed IL-1β, but the balance in function favored immune suppression, with both IL-10 expression and IDO activity contributing to inhibition of CD4+ effector T cells induced by DCIL-15/p38inhib. Ascites CD14+ cell expression of B7-H1 did not contribute significantly to immune suppression, possibly because DCIL-15/p38inhib-stimulated CD4+ T cells expressed minimal levels of PD-1.

The finding that IL-2 could enhance CD4+ T cell responses to antigen stimulation in cocultures with ascites CD14+ T cells was unexpected, given that IL-2 administration has been associated with expansion of Treg in ovarian cancer20, and IL-2 favors Treg differentiation at the expense of Th17 responses21,22. Furthermore, adjuvant treatment with IL-2 in clinical trials of tumor vaccines contributes to expansion of Foxp3+ Treg, possibly limiting the efficacy of immunotherapy23,24,25 In contrast, one study has found that IL-2 can mediate conversion of freshly isolated Treg from ovarian tumors into Th17 cells, suggesting that local treatment with IL-2 may promote anti-tumor activity26.

In conclusion, effector CD4+ T cells derived by stimulation with DCIL-15/p38inhib retain the potential to migrate in response to chemokines expressed in the ovarian tumor microenvironment, but are vulnerable to suppression by ovarian tumor-associated CD14+ cells with an M2 macrophage phenotype. These observations suggest that the clinical efficacy of DC vaccination for ovarian cancer would be enhanced by adjuvant treatment with drugs that inhibit IDO or modulate myeloid cell function. IDO in particular is considered to play a pivotal role in immune regulation, and it is encouraging that a novel small molecule inhibitor of IDO (INCB024360, Incyte Corp.) is currently in Phase II clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: MJC received grant support from the Arkansas Center for Clinical and Translational Research (NIH UL1RR029884), and the Mary Kay Foundation (009-11). MJC is founder of DCV Technologies Inc., a biotechnology company dedicated to the clinical development of dendritic cell vaccines for the treatment of cancer.

We thank the clinical staff of the Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, UAMS for their invaluable assistance with procurement of blood and tissue samples from ovarian cancer patients.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The remaining authors declare no financial conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

References

- 1.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nature Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf D, Wolf AM, Rumpold H, et al. The expression of the regulatory T cell-specific forkhead box transcription factor FoxP3 is associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8326–8331. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Iwasaki M, et al. Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3360–3365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611533104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamoto A, Nikaido T, Ochiai K, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase serves as a marker of poor prognosis in gene expression profiles of serous ovarian cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6030–6039. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inaba T, Ino K, Kajiyama H, et al. Role of the immunosuppressive enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in the progression of ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kryczek I, Banerjee M, Cheng P, et al. Phenotype, distribution, generation, and functional and clinical relevance of Th17 cells in the human tumor environments. Blood. 2009;114:1141–1149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munn DH. Th17 cells in ovarian cancer. Blood. 2009;114:1134–1135. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-224246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon MJ, Goyne H, Stone PJB, et al. Dendritic cell vaccination against ovarian cancer - tipping the Treg/Th17 balance to therapeutic advantage? Exp Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11:1–5. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.554812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannon MJ, Goyne HE, Stone PJB, et al. Modulation of p38 MAPK signaling enhances dendritic cell activation of human CD4+ Th17 responses to ovarian tumor antigen. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:839–849. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1391-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanimoto H, Yan Y, Clarke J, et al. Hepsin, a cell surface serine protease identified in hepatoma cells, is overexpressed on ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2884–2887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Underwood LJ, Tanimoto H, Wang Y, et al. Cloning of TADG-14, a novel serine protease overexpressed by ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4435–4439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanimoto H, Underwood LJ, Wang Y, et al. Ovarian tumor cells express a transmembrane serine protease: a potential candidate for early diagnosis and therapeutic intervention. Tumor Biol. 2001;22:104–114. doi: 10.1159/000050604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun D, Longman RS, Albert ML. A two-step induction of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO) activity during dendritic cell maturation. Blood. 2005;106:2376–2381. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krempski J, Karyampudi L, Behrens MD, et al. Tumor infiltrating PD-1+ dendritic cells mediate immune suppression in ovarian cancer. J Immunol. 2011;186:6905–6913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santin AD, Bellone S, Ravaggi A, et al. Increased levels of interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-β in the plasma and ascetic fluid of patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Brit J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;108:804–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma MD, Hou DY, Liu Y, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase controls conversion of Foxp3+ Tregs to TH17-like cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Blood. 2009;113:6102–6111. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung DJ, Rossi M, Romano E, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-expressing mature human monocyte-derived dendritic cells expand potent autologous regulatory T cells. Blood. 2009;114:555–563. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-191197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conrad C, Gregorio J, Wang Y-H, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells promote immunosuppression in ovarian cancer via ICOS costimulation of foxp3+ T-regulatory cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5240–5249. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paulos CM, Carpenito C, Plesa G, et al. The inducible costimulator (ICOS) is critical for the development of human Th17 cells. Science Transl Med. 2010;2:55ra78. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei S, Kryczek I, Edwards RP, et al. Interleukin-2 administration alters the CD4+FOXP3+ T-cell pool and tumor trafficking in patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7487–7494. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kryczek I, Wei S, Zou L, et al. Th17 and regulatory T cell dynamics and the regulation by IL-2 in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol. 2007;178:6730–6733. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kryczek I, Wei S, Vatan L, et al. Opposite effects of IL-1 and IL-2 on the regulation of IL-17+ T cell pool. IL-1 subverts IL-2-mediated suppression. J Immunol. 2007;179:1423–1426. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemoine FM, Cherai M, Giverne C, et al. Massive expansion of regulatory T-cells following interleukin 2 treatment during a phase I-II dendritic cell-based immunotherapy of metastatic renal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:569–581. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berntsen A, Brimnes MK, thor Straten P, et al. Increase of circulating CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma during treatment with dendritic cell vaccination and low-dose interleukin-2. J Immunother. 2010;33:425–434. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181cd870f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beyer M, Schumak B, Weihrauch MR, et al. In vivo expansion of naive CD4+ CD25(high) FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in patients with colorectal carcinoma after IL-2 administration. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leveque L, Deknuydt F, Bioley G, et al. Interleukin 2-mediated conversion of ovarian cancer-associated CD4+ regulatory T cells into proinflammatory interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. J Immunother. 2009;32:101–108. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318195b59e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.