Abstract

Injection of rats with kainic acid (KA), a non-N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) type glutamate receptor agonist, induces recurrent (delayed) convulsive seizures and subsequently hippocampal neurodegeneration, which is reminiscent of human epilepsy. The protective effect of anti-epileptic drugs on seizure-induced neuronal injury is well known; however, molecular basis of this protective effect has not yet been elucidated. In this study, we investigated the effect and signaling mediators of voltage-gated Na+ channel blockers (Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, Oxcarbazepine, Valproic Acid, and Zonisamide) on KA-induced apoptosis in rat primary hippocampal neurons. Exposure of hippocampal neurons to 10 μM KA for 24 h caused significant increases in morphological and biochemical features of apoptosis, as determined by Wright staining and ApopTag assay, respectively. Analyses showed increases in expression and activity of cysteine proteases, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), intracellular free [Ca2+], and Bax:Bcl-2 ratio during apoptosis. Cells exposed to KA for 15 min were then treated with Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, Oxcarbazepine, Valproic Acid, or Zonisamide. Post-treatment with one of these anti-epileptic drugs (500 nM) attenuated production of ROS and prevented apoptosis in hippocampal neurons. Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, and Oxcarbazepine appeared to be less protective when compared with Valproic Acid or Zonisamide. This difference may be due to blockade of T-type Ca2+ channels also by Valproic Acid and Zonisamide. Our findings thus suggest that the anti-epileptic drugs that block both Na+ channels and Ca2+ channels are significantly more effective than agents that block only Na+ channels for attenuating seizure-induced hippocampal neurodegeneration.

Keywords: Primary hippocampal neurons, Kainic acid, Voltage-gated Na+ channel blocker

Introduction

Epilepsy can be defined as a recurrent paroxystic disorder of cerebral function. It is characterized by brutal and short attacks causing impairment or loss of consciousness, motor activity, sensory phenomena or behavior misfits, isolated or combined symptoms, according to the various types of epilepsy. The genesis of epilepsy is an increase in excitability in an area of the brain, due to an excessive depolarization, which can spread to involve the whole brain [1–3]. To avoid this abnormal depolarization, many current therapies act to blockade increase cellular polarization by inhibiting Na+ influx [4, 5]. Frequency or use-dependent block of neuronal Na+ channels is a prominent short-term effect of several commonly used anti-epileptic drugs. Since the first mutations of the neuronal Na+ channel SCN1A were identified 5 years ago, more than 150 mutations have been described in patients with epilepsy [6, 7]. The growing role of Na+ channel mutations in neurological disease provides increased incentive for developing new and more specific Na+ channel inhibitors for prevention of neurodegeneration.

Voltage-gated Na+ channels (VGSC) are essential for the initiation and propagation of action potentials in neurons [8]. Abnormal VGSC activity is central to the pathophysiology of epileptic seizures and many of the most widely used anti-epileptic drugs including Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, Oxcarbazepine, Valproic Acid, and Zonisamide, are inhibitors of VGSC function [9]. Therefore, these anti-epileptic drugs are also efficacious in the treatment of other nervous system disorders such as migraine, multiple sclerosis, neurodegenerative diseases, and neuropathic pain [9]. It has been recently demonstrated that VGSC blockers can function as neuroprotective agents due to inhibition of apoptotic pathways [10, 11].

Kainic acid (KA), a non-selective agonist of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate/kainate receptors (AMPA/KARs), causes neuronal death in the hippocampus and also causes neuron depolarization and excessive Ca2+ influx, which can initiate intracellular signaling cascades that include nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activation, free radical formation, and mitochondrial dysfunction that, in turn, result in inflammatory responses, cytokine expression, and oxidative stress via production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [12]. The KA model of experimental epilepsy has yielded a detailed understanding of some of the processes involved in epileptogenesis and the generation of spontaneous recurrent seizures [13, 14]. When administered systemically or intracerebroventricularly in animal models, KA produces an epilepsy syndrome similar to human temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). Experimental animals treated acutely with KA develop status epilepticus followed by neurodegeneration in specific brain regions such as the hippocampus, piriform cortex, thalamus, and amygdala. After a latent period of days to weeks, these animals begin to exhibit spontaneous, recurrent limbic seizures—the hallmark of the epileptic state [13, 14]. Much like the human syndrome, there are histopathological changes including cell death in hippocampal subregions. Calpain activation following KA-induced seizure activity in adult rat brain also exhibits a specific spatio-temporal pattern [15–17]. Observations suggest that KA evokes excitotoxicity in hippocampus resulting in proteolytic activation of a pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 subfamily member, nuclear translocation of apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) and endonuclease G (endo G), DNA fragmentation, and nuclear condensation. These strongly suggest that calpain plays a pivotal role in the excitotoxic signal transduction cascade leading to DNA fragmentation. In the hippocampal neuron culture, KA increases the activities of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) such as extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK (p38) [18].

VGSC blockers acting through multiple mechanisms may inhibit voltage-gated and receptor-gated Ca2+ channels, voltage-dependent Cl− channels, and excitatory neurotransmission. However, it is currently unclear how VGSC blockers prevent hippocampal neuron injury. We examined the neuroprotective effects of VGSC blockers on KA-induced hippocampal neuron death by focusing on the apoptotic events that involved activities of calpain and caspases. Our data suggest that VGSC blockers have a therapeutic potential for suppressing KA-induced hippocampal neuron death. However, VGSC blockers, which also possess the ability to block T-type Ca2+ channels may offer higher level of neuroprotection when compared with VGSC blocker alone. These findings prompted us to hypothesize that blockers of both VGSC and Ca2+ channels could have a potent neuroprotective role in hippocampal neurons against KA-induced excitotoxicity.

Materials and Methods

Primary Hippocampal Neuron Cultures and Experimental Treatments

Zero-day-old rat pups were decapitated and hippocampal neurons were isolated and cultured according to published procedures [19, 20] with some modifications. Briefly, after dissection, hippocampi were minced and treated with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) for 20 min. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in a neurobasal medium (GIBCO) containing 1:50 B27 (GIB-CO), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum and were subsequently dissociated by repeated pipetting through a 1-ml Eppendorf pipette tip. Cells were then plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/dish in poly-D-lysine-coated 24-well plates. On days 2 and 4, one-half of the medium was exchanged. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a fully-humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 and 95% air. In order to arrest the growth of non-neuronal cells, 10 μM cytosine arabinoside (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to the culture medium 18–24 h after plating. The medium was replaced at an interval of every 2 days with a maintenance medium containing neurobasal media and 5% B27 supplement (GIBCO). After 7 days of culture in vitro, successful cultures of neurons were selected for further studies. Optimal doses of KA, Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, Oxcarbazepine, Valproic Acid, and Zonisamide (Sigma) were determined for rat primary hippocampal neurons. Cells were treated with KA alone for 24 h to examine the cell death. Also, cells were treated with 10 μM KA for 15 min and then treated with 500 nM VGSC blocker for 24 h. Cells from all treatment groups were used for determination of morphological and biochemical features of apoptosis and analyses of specific protein expression and activity by Western blotting.

Cell Viability

Cell viability was expressed as percentage of viable cells remaining following KA exposure and subsequent treatment versus control hippocampal neurons. We performed trypan blue dye (TBD) exclusion staining followed by cell counting. TBD is excluded by viable cells with intact cell membranes. We added 50 μl of 0.4% TBD to 50 μl of the cell suspension and then counted the number of stained (blue) and unstained (white) cells in each of the four corner squares of the hemacytometer. Cell viability (%) was calculated according to the following equation: cell viability (%) = [number of unstained (viable) cells/total cells counted (stained + unstained)] × 100.

Detection of Apoptosis

Cells from each treatment were washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, sedimented onto the microscopic slide, and fixed. The morphological (Wright staining) and biochemical (ApopTag assay) features of apoptosis were examined, as we described previously [14–16]. After Wright staining and ApopTag assay, cells were counted under the light microscope to determine percentage of apoptosis. ApopTag assay detects apoptotic cells in situ by labeling and detecting DNA strand breaks. At least 500 cells were counted in each treatment and the percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated.

Determination of Intracellular Free [Ca2+] Using Fura-2 Assay

The level of intracellular free [Ca2+] was measured in rat primary hippocampal neurons using the fluorescence Ca2+ indicator Fura-2/AM, as described previously [21, 22] using standards of the Calcium Calibration Buffer Kit with Magnesium (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Measurement of ROS Production

Time-course experiments were performed to compare ROS production in rat primary hippocampal neurons after KA exposure without and with Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, Oxcarbazepine, Valproic Acid, and Zonisamide. ROS production was detected by using the fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF-DA, Sigma), as described earlier [21, 22]. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 30–1,440 min. After each time point (30–1,440 min), each plate was washed twice with Hank’s balanced salt solution (GIBCO) and loaded with 1 ml media containing 5 μM of DCF-DA and the fluorescence intensity was measured at 530 nm after excitation at 480 nm in Spectramax Gemini XPS (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The increase in fluorescence intensity was used to assess the net intracellular ROS production.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed, as we described previously [20, 21]. The autoradiograms were scanned using Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, Seattle, WA) and optical density (OD) of each band was determined using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). We used polyclonal calpain and calpastatin primary IgG antibodies. Also, monoclonal caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2 primary IgG antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used to assess apoptotic pathways. Monoclonal β-actin primary IgG antibody (clone AC-15, Sigma) was used to standardize protein loading in Western blotting. We used horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary IgG antibody (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH) to detect a primary antibody, except in case of calpain and calpastatin where we used HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary IgG antibody (ICN Biomedicals).

Calpain Activity Assay

We determined calpain activity in total cell lysates using a calpain activity assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The calpain activity kit contains a fluorogenic peptide (Ac-LLY-AFC) as calpain substrate, lysis buffer, and reaction buffer. Briefly, cells were lysed in the lysis buffer for 20 min at 4°C. Cell lysates were then incubated with the substrate and reaction buffer for 1 h at 37°C in the dark. Upon cleavage of substrate, the fluorogenic portion (AFC) produced a yellow-green fluorescence at a wavelength of 505 nm following excitation at 400 nm. Fluorescence emission was measured in a standard fluorimeter.

Colorimetric Assays for Caspase-8, Caspase-9, and Caspase-3 Activities

Measurements of caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3 activities were performed using a commercially available caspase-8/caspase-9 assay kit (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) and a caspase-3 assay kit (Sigma). Concentration of pNA released from the substrate was calculated from the absorbance values at 405 nm. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

All results obtained from different treatments of rat primary hippocampal neurons were analyzed using StatView software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) of separate experiments (n ≥ 3) and compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher’s post hoc test. Significant difference between control (CTL) and KA was indicated by *(P ≤ 0.05) or **(P ≤ 0.01). On the other hand, significant difference between a single treatment and a double treatment was indicated by #(P ≤ 0.05) or ##(P ≤ 0.01).

Results

Voltage-gated Na+ Channel Blockers Protect Rat Primary Hippocampal Neurons from KA-Induced Toxicity

We tested the KA toxicity in absence and in presence of one of the voltage-gated Na+ channel blockers in rat primary hippocampal neurons (Fig. 1). To test the KA toxicity alone, we first treated rat primary hippocampal neuron cells with various concentrations of KA that reduced cell viability (Fig. 1a). However, post-treatment at 15 min with 500 nM of a VGSC blocker provided effective protection in rat primary hippocampal neurons, compared with KA treatment only (Fig. 1c). Cells treated with 500 nM of a VGSC blocker alone appeared healthy, confluent, and undamaged, similar to control cells (Fig. 1). After the treatments, cells were also examined for apoptosis by Wright staining and ApopTag assay (Fig. 1a, b). All treatment groups were examined under the light microscope and cells were counted to determine the amount of apoptotic cells. The post-treatment of cells at 15 min with Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, Oxcarbazepine, Valproic Acid, or Zonisamide in the presence of KA significantly decreased apoptotic death (Fig. 1c). Results obtained from Wright staining (Fig. 1a) were further confirmed by the ApopTag assay (Fig. 1b). Compared with control cells, cells treated with 10 μM KA showed a greater than 50% increase (P < 0.01) in apoptotic cells (Fig. 1c). After the post-treatment of cells at 15 min with 500 nM Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, Oxcarbazepine, Valproic Acid, or Zonisamide, there was a decrease in KA-induced apoptosis by three to fourfolds, compared with cells treated with KA only. Our data indicated that Valproic Acid and Zonisamide protected hippocampal neurons better than Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, and Oxcarbazepine.

Fig. 1.

Post-treatment with VGSC blockers prevented KA-induced apoptosis in rat primary hippocampal neurons. Photomicrographs showing representative cells from each treatment group after a Wright staining and b ApopTag assay. The arrows indicate apoptotic cells. c Bar graphs indicating residual cell viability (TBD exclusion assay), and the percentage of apoptotic cells (ApopTag assay). Treatment groups: control; 500 nM Lamotrigine (24 h); 500 nM Rufinamide (24 h); 500 nM Oxcarbazepine (24 h); 500 nM Valproic Acid (24 h); 500 nM Zonisamide (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Lamotrigine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Rufinamide (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Oxcarbazepine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Valproic Acid (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + (15 min post-treatment) Zonisamide (post-treatment at 15 min)

Voltage-gated Na+ Channel Blockers Decrease ROS Production in Rat Primary Hippocampal Neurons

To elucidate further the underlying mechanism of VGSC blocker mediated neuroprotection, we measured fluorescence intensity (as an indication of ROS production) resulting from the oxidation of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin (DCF) in rat primary hippocampal neurons in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2). After KA treatment for 30 min, ROS production gradually increased. At the 1,440 min (24 h) time point, DCF fluorescence appeared stronger than that at the 30 min time point (Fig. 2). Interestingly, post-treatment at 15 min with a VGSC blocker prevented KA-induced ROS production markedly at all experimental time points. The results demonstrated that Valproic Acid or Zonisamide acted as a stronger anti-oxidant (P < 0.01) when compared with Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, or Oxcarbazepine (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of ROS production by VGSC blockers. All treatments (0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, and 1,440 min) were performed in presence of 5 μm DCF-DA. Treatment groups: control; 500 nM Lamotrigine (24 h); 500 nM Rufinamide (24 h); 500 nM Oxcarbazepine (24 h); 500 nM Valproic Acid (24 h); 500 nM Zonisamide (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Lamotrigine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Rufinamide (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Oxcarbazepine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Valproic Acid (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + (15 min post-treatment) Zonisamide (post-treatment at 15 min)

Voltage-gated Na+ Channel Blockers Prevent Ca2+ Influx and Inhibit Activation of Calpain

Calcium (Ca2+) plays numerous roles in neuronal function and therefore blocking Ca2+ channels can yield various effects. We assessed whether the increase in intracellular free [Ca2+] (Fura-2 assay) could stimulate calpain activity during cell death (Fig. 3). Treatment of cells with KA for 24 h caused a significant increase (P = 0.009) in intra-cellular free [Ca2+] compared with control cells (Fig. 3a). Also, there was no significant difference (P = 0.763) between intracellular free [Ca2+] in control cells and those treated with KA plus VGSC blocker, indicating that VGSC blocker was capable of preventing the KA-induced increase in intracellular free [Ca2+]. Our results demonstrated that Valproic Acid and Zonisamide (P < 0.01) acted as a stronger protective agent than other VGSCs (P < 0.05). It may be attributed to their T-type Ca2+ channel blocking properties. Our finding of increased Ca2+ influx (24 h) in KA treated cells (Fig. 3b) suggested activation of the Ca2+-dependent protease calpain and its involvement in cell death. The expression of m-calpain was increased, while expression of calpastatin (endogenous calpain inhibitor) was down regulated in KA treated cells (Fig. 3c). Uniform expression of β-actin served as a loading control for cytosolic proteins. Further, we measured the calpain:calpastatin ratio (Fig. 3c). Our results showed a significant increase in the calpain:calpastatin ratio in KA treated cells when compared with control cells (P < 0.01). The post-treatment with a VGSC blocker attenuated this increase.

Fig. 3.

Determination of intracellular free [Ca2+] and involvement of calpain in neuronal death. a Post-treatment with VGSC blockers decreased intracellular free [Ca2+] (Fura-2 assay) and calpain activity (fluorometric assay). b Western blot analysis to show levels of calpain, calpastatin, and β-actin. c Densitometric analysis showing the calpain:calpastatin ratio. Treatment groups: control; 500 nM Lamotrigine (24 h); 500 nM Rufinamide (24 h); 500 nM Oxcarbazepine (24 h); 500 nM Valproic Acid (24 h); 500 nM Zonisamide (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Lamotrigine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Rufinamide (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Oxcarbazepine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Valproic Acid (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + (15 min post-treatment) Zonisamide (post-treatment at 15 min)

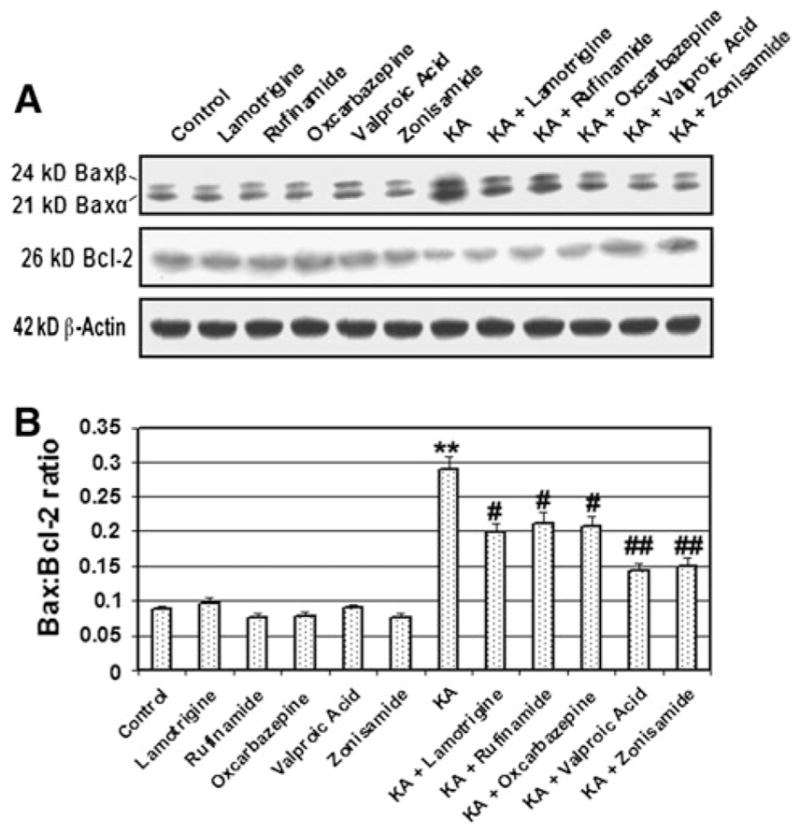

Voltage-gated Na+ Channel Blockers Decreased the Bax:Bcl-2 Ratio

Commitment to apoptosis was measured by examining any increase in the ratio of Bax (proapoptotic protein) to Bcl-2 (antiapoptotic protein) expression (Fig. 4). The antibody used in this investigation could recognize both 21 kD Baxα and 24 kD Baxβ isoforms (Fig. 4). Our results demonstrated that cells treated with KA increased Bax but decreased Bcl-2 expression (Fig. 4a) and thus the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio was found to be significantly increased (Fig. 4b). Cells treated with KA showed threefold increase (P = 0.002) in the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio indicating a commitment to apoptosis, compared with control cells (Fig. 4b). β-Actin expression was used as a loading control. The increase in Bax:Bcl-2 ratio (Fig. 4b) could promote mitochondrial release of pro-apoptotic factors. The post-treatment with a VGSC blocker significantly attenuated this increase compared with cells treated with KA. Notably, VGSC blocker alone did not alter the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio when compared with control cells (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Alterations in Bax and Bcl-2 expression at the protein level. a Representative pictures to show Bax, Bcl-2, and β-actin at the protein level (Western blotting). b Densitometric analysis showing the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio. Treatment groups: control; 500 nM Lamotrigine (24 h); 500 nM Rufinamide (24 h); 500 nM Oxcarbazepine (24 h); 500 nM Valproic Acid (24 h); 500 nM Zonisamide (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Lamotrigine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Rufinamide (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Oxcarbazepine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Valproic Acid (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + (15 min post-treatment) Zonisamide (post-treatment at 15 min)

Post-treatment with Voltage-gated Na+ Channel Blocker Inhibited Activities of Caspases

Caspases belong to a family of cysteine proteases that play central roles in the initiation and execution of the apoptotic process. Caspase-8 and caspase-9 are representative of the initiator caspases, which activate the executor caspases including caspase-3. In order to investigate the effects of VGSC blockers on apoptosis, we used Western blotting (Fig. 5a) and colorimetric assays (Fig. 5b) to determine, respectively, activation and activity of caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3 in the cells treated with KA. Our results showed significant increases (P = 0.001) in the activities of all these caspases in cells treated with KA (Fig. 5). We also observed that post-treatment with VGSC blocker significantly inhibited activities of caspases in cells treated with KA (Fig. 5). No significant difference (P = 0.899) in caspase activity was seen between control cells and cells treated with a VGSC blocker alone.

Fig. 5.

Examination of activation and activity of different caspases. a Western blotting to show levels of caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3, and β-actin. b Colorimetric determination of caspase activities. Treatment groups: control; 500 nM Lamotrigine (24 h); 500 nM Rufinamide (24 h); 500 nM Oxcarbazepine (24 h); 500 nM Valproic Acid (24 h); 500 nM Zonisamide (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Lamotrigine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Rufinamide (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Oxcarbazepine (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + Valproic Acid (post-treatment at 15 min); 10 μM KA (24 h) + (15 min post-treatment) Zonisamide (post-treatment at 15 min)

Discussion

The present study was designed to investigate the potential of different VGSC blockers to protect rat primary hippocampal neurons against the toxic effects of KA. Our results show that VGSC blockers significantly reduce KA-induced hippocampal neuron death. The current study also indicates that Valproic Acid and Zonisamide (both of which block VGSC and T-type Ca2+ channels) are more potent neuro-protective agents than Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, and Oxcarbazepine against KA-induced rat hippocampal neuron death. Our results demonstrate that Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, Oxcarbazepine, Valproic Acid, and Zonisamide attenuate cell death due to inhibition of ROS production, Ca2+ influx, calpain activity, Bax:Bcl-2 ratio, and caspase activities. These findings can be viewed as a stepwise process to neuroprotection.

Free radical damage in neurons has been linked to a number of neurological diseases [24, 25]. Recently, it has been reported that systemic administration of KA induces ROS production in rat brain [26] and damages the hippocampal CA3 subregion. Most of the ROS causing oxidative stress are generated from the mitochondrial electron transport chain. In addition, earlier reported data suggest that ROS generation gradually increases during the first 30 min of KA treatment, followed by a robust increase in the rate of ROS production after 6 h in hippocampal neurons [27]. Therefore, we measured total cytosolic ROS levels via the peroxide-sensitive dye DCF. Consistent with the previous study [26], our data indicated that long-term (1,440 min) exposure of hippocampal neurons to KA causes an increase in ROS levels. We also found that post-treatment with VGSC blockers significantly reduced KA-induced ROS production in hippocampal neurons. Our results suggest that the neuroprotective effect of VGSC blockers in hippocampal neurons may be related to a decrease in mitochondrial ROS production.

Ca2+ influx is a necessary step in neurotransmitter release and one consequence of Ca2+ channel blockade is decreased neurotransmitter release, including excitatory glutamate [28, 29]. This may partly explain the efficacy of T-type Ca2+ channel blockers in treating absence seizures. More importantly, elevated levels of intracellular Ca2+ are thought to activate numerous Ca2+-dependent processes that lead to cell death. Thus, blockade of Ca2+ channels may play a central role in preventing neurodegeneration. Our findings demonstrated that the VGSC blockers used in this study also partially inhibit Ca2+ influx. Valproic Acid and Zonisamide showed the most significant attenuation of Ca2+ influx, which was consistent with previously published data showing that both of these drugs significantly inhibit the T-type Ca2+ channels [30]. Because hippocampal neurons treated with Valproic Acid or Zonisamide showed lower levels of apoptotic death, our results suggest that drugs that block both VGSC and Ca2+ channels may play an important role in neuronal defense mechanisms.

It has previously been reported that calpain plays a crucial role in Ca2+ influx during cell injury and is also activated as a result of Ca2+ influx [21–23]. Calpain also plays a role in initiation of apopototic death by activating Bax, cleaving the endogenous inhibitor of calcineurin, increasing Bad activity, and influencing the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio both directly and indirectly [21]. Increased expression of calpain has previously been shown to coincide with an increase in the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio [21, 22], suggesting that alterations in expression of these Bcl-2 family members play an important role in cell death. Therefore, we examined calpain activity and expression as well as levels of calpastatin (endogenous calpain inhibitor), Bax, and Bcl-2 in hippocampal neurons following exposure to KA and VGSC blockers. Our results demonstrated that post-treatment of hippocampal neurons with Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, Oxcarbazepine, Valproic Acid, and Zonisamide inhibited calpain activity and decreased both calpain: calpastatin and Bax:Bcl-2 ratios.

Caspases are central to the execution of apoptosis and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ischemia [31], traumatic brain injury [31], and epilepsy [32]. In particular, induction of caspase-3 has been reported in rat hippocampal neurons following systemic administration of KA [27], transient global ischemia, and fluid percussion-induced traumatic brain injury. The endogenous calpain inhibitor, calpastatin, can be degraded not only by calpain but also by caspases during apoptosis. Thus, it is possible that caspase-3 may indirectly activate calpain via calpastatin degradation. From our own observations, a decrease in activities of caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3 correlates well with reduction in cell death following VGSC blocker treatment. However, Valproic Acid and Zonisamide showed at least 15% more efficacy than Lamotrigine, Rufinamide, and Oxcarbazepine in inhibition of caspase activities.

The mechanisms involved in pathogenesis of epilepsy are complex and have not been clearly delineated. Consequently, therapeutic regimens are focused on supportive care and they do not address mechanisms of cell death and neuronal injury. Although we have shown that VGSC blockers may reduce KA-induced hippocampal neuron death in vito, it remains to be explored whether these therapies provide neuroprotection in vivo. Interestingly, our findings suggest that blockade of both VGSC and T-type Ca2+ channels results in greater attenuation of the apoptotic cascade than blockade of VGSC alone. Our results have potential clinical significance because therapies that act to attenuate neuronal death in seizure, ischemia, and CNS trauma may also prevent loss of neurological function in affected patients.

Acknowledgments

This paper was dedicated to honor Dr. Abel Lajtha, who had the foresight to establish this journal and significantly contributed new knowledge not only to basic neuroscience but also to medical neuroscience.

Contributor Information

Arabinda Das, Department of Neurosciences, Medical University of South Carolina, 96 Jonathan Lucus Street, Charleston, SC 29425, USA.

Misty McDowell, Department of Neurosciences, Medical University of South Carolina, 96 Jonathan Lucus Street, Charleston, SC 29425, USA.

Casey M. O’Dell, Department of Neurosciences, Medical University of South Carolina, 96 Jonathan Lucus Street, Charleston, SC 29425, USA

Megan E. Busch, Department of Neurosciences, Medical University of South Carolina, 96 Jonathan Lucus Street, Charleston, SC 29425, USA

Joshua A. Smith, Department of Neurosciences, Medical University of South Carolina, 96 Jonathan Lucus Street, Charleston, SC 29425, USA

Swapan K. Ray, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia, SC 29209, USA

Naren L. Banik, Email: baniknl@musc.edu, Department of Neurosciences, Medical University of South Carolina, 96 Jonathan Lucus Street, Charleston, SC 29425, USA

References

- 1.Fuerst D, Shah J, Shah A, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis is a progressive disorder: a longitudinal volumetric MRI study. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:413–416. doi: 10.1002/ana.10509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leite JP, Bortolotto ZA, Cavalheiro EA. Spontaneous recurrent seizures in rats: an experimental model of partial epilepsy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1990;14:511–517. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scharfman HE. The neurobiology of epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7:348–354. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0053-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams PA, Hellier JL, White AM, et al. Development of spontaneous seizures after experimental status epilepticus: implications for understanding epileptogenesis. Epilepsia. 2007;48:157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon SC. Sodium channel gating: no margin for error. Neuron. 2002;34:853–854. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00735-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alekov AK, Rahman MM, Mitrovic N, et al. Enhanced inactivation and acceleration of activation of the sodium channel associated with epilepsy in man. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:2171–2176. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spampanato J, Escayg A, Meisler MH, et al. Functional effects of two voltage-gated sodium channel mutations that cause generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus type 2. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7481–7490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07481.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catterall WA. Molecular properties of voltage-sensitive sodium channels. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:953–985. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.004513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantegazza M, Curia G, Biagini G, et al. Voltage-gated sodium channels as therapeutic targets in epilepsy and other neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:413–424. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Lookeren Campagne M, Lucassen PJ, Vermeulen JP, et al. NMDA and kainate induce internucleosomal DNA cleavage associated with both apoptotic and necrotic cell death in the neonatal rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:1627–1640. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urenjak J, Obrenovitch TP. Neuroprotection–rationale for pharmacological modulation of Na+-channels. Amino Acids. 1998;14:151–158. doi: 10.1007/BF01345256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim DH, Yoon BH, Jung WY, et al. Sinapic acid attenuates kainic acid-induced hippocampal neuronal damage in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-Ari Y, Cossart R. Kainate, a double agent that generates seizures: two decades of progress. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:580–587. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01659-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavalheiro EA, Fernandes MJ, Turski L, et al. Spontaneous recurrent seizures in rats: amino acid and monoamine determination in the hippocampus. Epilepsia. 1994;35:01–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bi X, Chang V, Siman R, et al. Regional distribution and time-course of calpain activation following kainate-induced seizure activity in adult rat brain. Brain Res. 1996;726:98–108. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Araújo IM, Ambrósio AF, Leal EC, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase proteolysis limits the involvement of nitric oxide in kainate-induced neurotoxicity in hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 2003;85:791–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stucki BL, Matzelle DD, Ray SK, et al. Upregulation of calpain in neuronal apoptosis in kainic acid induced seizures in rats. ASN Annual Meeting; August 14–19; 2004. p. DP1-01. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SH, Chun W, Kong PJ, et al. Sustained activation of Akt by melatonin contributes to the protection against kainic acid-induced neuronal death in hippocampus. J Pineal Res. 2006;40:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nunez J. Primary culture of hippocampal neurons from P0 newborn rats. J Vis Exp. 2008;19:895. doi: 10.3791/895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sunanda RaoBS, Raju TR. Corticosterone attenuates zinc-induced neurotoxicity in primary hippocampal cultures. Brain Res. 1998;791:295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01569-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das A, McDowell M, Pava MJ, et al. The inhibition of apoptosis by melatonin in VSC4.1 motoneurons exposed to oxidative stress, glutamate excitotoxicity, or TNF-α toxicity involves membrane melatonin receptors. J Pineal Res. 2010;48:157–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das A, Sribnick EA, Wingrave JM, et al. Calpain activation in apoptosis of ventral spinal cord 4.1 (VSC4.1) motoneurons exposed to glutamate: calpain inhibition provides functional neuroprotection. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:551–562. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters SL, Sarang SS, Wang KK, et al. Calpains mediate calcium and chloride influx during the late phase of cell injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1177–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devi PU, Manocha A, Vohora D. Seizures, antiepileptics, antioxidants and oxidative stress: an insight for researchers. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:3169–3177. doi: 10.1517/14656560802568230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enns GM. Neurologic damage and neurocognitive dysfunction in urea cycle disorders. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2008;15:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henshall DC, Araki T, Schindler CK, et al. Activation of Bcl-2-associated death protein and counter-response of Akt within cell populations during seizure-induced neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8458–8465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08458.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giusti P, Franceschini D, Petrone M, et al. In vitro and in vivo protection against kainate-induced excitotoxicity by melatonin. J Pineal Res. 1996;20:226–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1996.tb00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan DX, Manchester LC, Reiter RJ, et al. Melatonin protects hippocampal neurons in vivo against kainic acid-induced damage in mice. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54:382–389. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981101)54:3<382::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao L. An update on peptide drugs for voltage-gated calcium channels. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov. 2010;5:14–22. doi: 10.2174/157488910789753558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joëls M. Stress, the hippocampus, and epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:586–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bilsland J, Harper S. Caspases and neuroprotection. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:1745–1752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagatomo I, Akasaki Y, Uchida M, et al. Effects of combined administration of zonisamide and valproic acid or phenytoin to nitric oxide production, monoamines and zonisamide concentrations in the brain of seizure-susceptible EL mice. Brain Res Bull. 2000;53:211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]