Abstract

In this issue of Cancer Cell, Wang and colleagues report that CARM1, a protein arginine methyltransferase, specifically methylates BAF155/SMARCC1, a core subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling/tumor suppressor complex. This modification facilitates the targeting of BAF155 to genes of the c-Myc pathway and enhances breast cancer progression and metastases.

While long studied for its role in modulation of chromatin structure and transcriptional regulation, in the last several years the SWI/SNF (BAF) chromatin remodeling complex has emerged as one of the most widely mutated group of genes in human cancer. The complex utilizes the energy from ATP hydrolysis to mobilize nucleosomes and modulate chromatin structure. Initial discovery of the complex came from yeast in which mutations in genes encoding the SWI/SNF subunits were found essential for transcriptional activation of mating type SWItching and sucrose metabolism, the latter resulting in a Sucrose Non-Fermenting (SNF) phenotype. In mammals, the complex consists of approximately 15 subunits that include both ubiquitously expressed core subunits, such as BAF155/SMARCC1, as well as a number of lineage-specific subunits often encoded by gene families(Wu et al., 2009). The complex has been implicated in the dynamic transcriptional regulation of genes involved in fate specification, proliferation and differentiation, and also in various types of DNA repair.

The SWI/SNF complex was initially linked to cancer in 1998 when biallelic inactivating mutations in the SMARCB1/SNF5/INI1/BAF47 subunit were identified in aggressive pediatric rhabdoid cancers (Versteege et al., 1998). Mouse models established SMARCB1 as a bona fide and potent tumor suppressor (Wilson and Roberts, 2011). With the advent of cancer genome sequencing efforts, it became clear that SMARCB1 is not the only subunit mutated in cancer as recurrent mutations in at least eight SWI/SNF subunits were also identified, collectively occurring in 20% of human cancers (Kadoch et al., 2013). This has resulted in interest in identifying mechanisms by which activity of the SWI/SNF complex is regulated with the hope that such mechanistic understanding may reveal novel opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Arginine methylation, catalyzed by a family of protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs), has long been implicated in the regulation of gene transcription and translation. CARM1 (Coactivator-Associated Arginine Methyltransferase-1), one of nine members of the family, has been shown to methylate substrates involved in chromatin remodeling and gene transcription including histone H3 (at R17), histone acetyltransferases (p300/CBP), splicing factors (CA150, SAP49, SmB, and U1C), and RNA-binding proteins (PABP1, HuR and HuD) (Bedford and Clarke, 2009). CARM1 has also been implicated in cancer. High-level expression of CARM1 has been observed in several cancers, including those of prostate, colon and breast, with levels higher in metastatic breast cancer than in primary. CARM1 has also been shown to stimulate breast cancer growth and serve coactivator roles for numerous proteins that have been implicated in cancer including p53, E2F1, NF-κB, β-catenin and steroid hormone receptors (Bedford and Clarke, 2009). However, the mechanisms by which CARM1 may contribute to breast cancer growth, and whether this activity depends upon enzymatic methylation of targets remains poorly understood.

In this issue of Cancer Cell, Wang and colleagues investigate these mechanisms by searching for novel CARM1 substrates in breast cancer cells (Wang et al., 2014). The authors inactivated CARM1 in a breast cancer cell line in order to identify differentially methylated proteins via a methylation-specific antibody. Interestingly, a 90% knockdown of CARM1 with shRNAs had only modest effect on CARM1 level and activity, necessitating the authors to create a full knockout with the genome-editing Zinc Finger Nuclease technology. The proteins methylated only in cells with intact CARM1 included the SWI/SNF subunit BAF155. Through a series of well-designed biochemical assays, the authors confirmed that BAF155 is a bona fide CARM1 substrate and identified Arginine 1064 (R1064) as the sole methylation site.

Given the emerging links between the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex and cancer, Wang et al. sought to investigate the mechanistic consequence of this modification and to evaluate its cancer relevance. They first tested the effect of BAF155 methylation upon its association with chromatin by generating a methylation-defective BAF155R1064K mutant and used ChIP-seq to compare its binding to that of wild-type (BAF155WT.). BAF155R1064K was readily incorporated into the SWI/SNF complex and showed overlap with the binding of BAF155WT, the majority of which (~74%) was methylated. However, there were also substantial differences, suggesting that CARM1-mediated methylation of BAF155 affected its targeting. Subsequent analysis of the genes preferentially bound by methylation-competent BAF155WT revealed meiosis and c-Myc pathways as the two most significantly enriched pathways. ChIP-PCR on several selected targets confirmed that methylation of BAF155 creates novel binding sites and correlates with increased expression of the associated genes. Notably, when binding of BAF155 was compared to that of other SWI/SNF subunits, the authors identified regions at which BRG1/SMARCA4, a catalytic ATPase subunit, and BAF53/ACTL6A were not detected but SNF5/SMARCB1 and other subunits were. The authors thus propose that BAF155 may exist in sub-complexes capable of binding chromatin, a novel and interesting possibility that awaits confirmation as differential antibody affinities can make such analyses challenging (Figure 1).

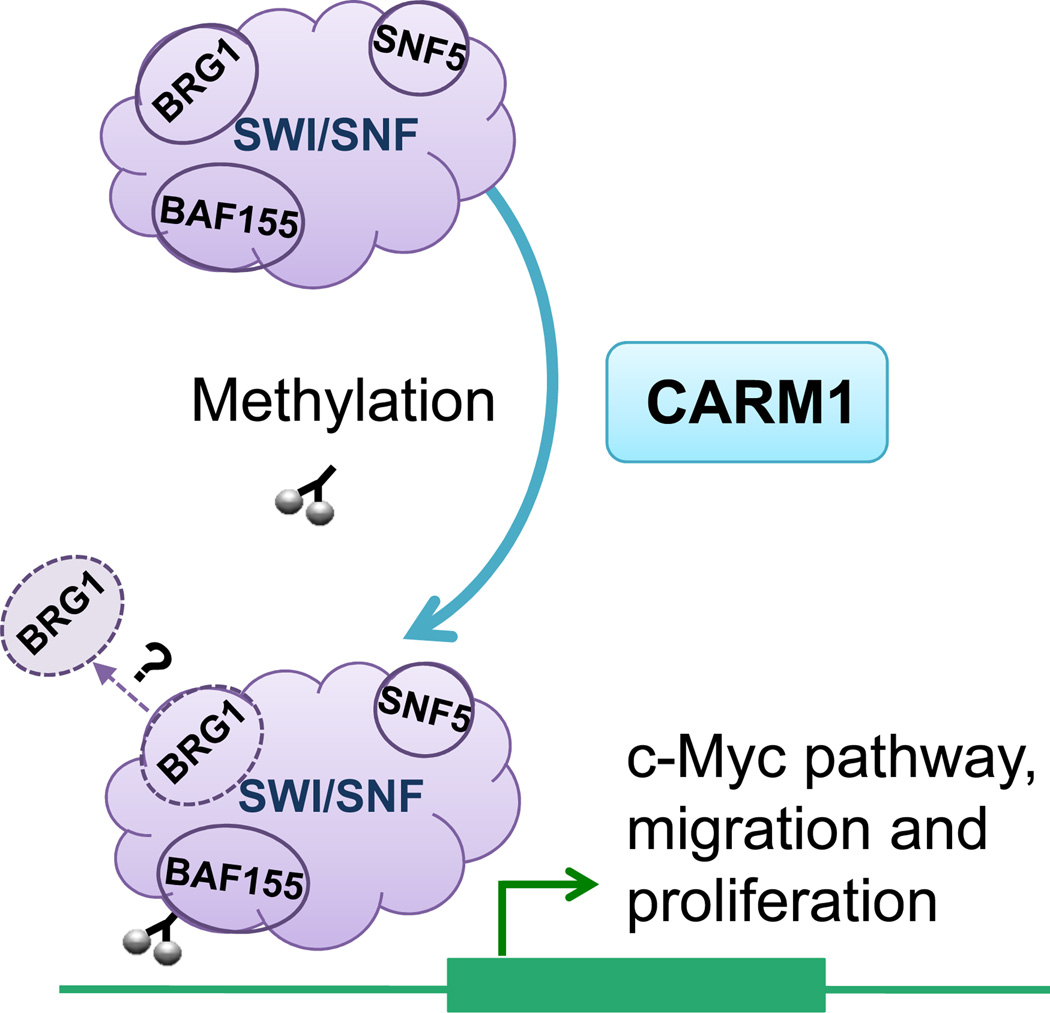

Figure 1. Methylation of BAF155 by CARM1 alters SWI/SNF targeting to activate c-Myc, migration and proliferation pathways.

CARM1 methylates BAF155, a core subunit of the SWI/SNF complex, at R1064, which facilitates binding and activation of c-Myc, migration and proliferation pathways. Methylated BAF155 may exist in a sub-complex lacking BRG1 and BAF53.

Having identified a role for CARM1-mediated methylation of BAF155 in control of the c-Myc pathway, the authors sought to determine whether this may contribute to oncogenesis. Immunohistochemistry for methylated BAF155 (me-BAF155) on clinical breast cancer samples revealed that me-BAF155 was expressed at higher levels in cancer samples than in normal breast tissues. Moreover, me-BAF155 also correlated with advanced stages, with higher levels of me-BAF155 associated with poor survival. Importantly, knocking down BAF155 in MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in impaired proliferation and migration, an effect that was rescued by re-expression of WT BAF155 but not by the methylation-deficient R1064K mutant. This observation was validated and extended in vivo in which MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing wild-type BAF155 but not the R1064K mutant displayed lung colonization and tumor outgrowth.

Collectively, the results in Wang et al. reveal that the elevated levels of CARM1 and BAF155 in aggressive breast cancer may contribute to pathogenesis by CARM1-mediated methylation of BAF155 at R1064, facilitating activation of pro-oncogenic and metastatic pathways. Therapeutic targeting of protein methyltransferases has recently become an area of intense interest in drug development due to increased recognition of roles for these enzymes in cancer pathogenesis. Indeed, two potent and selective CARM1 inhibitors have been reported (Copeland et al., 2009), although substantial work is still needed to determine whether they can ultimately be made into drugs. Enthusiasm may be somewhat tempered by the finding that knock down of CARM1 by 90% was insufficient to mimic the effects of CARM1 knockout as this suggests that complete pharmacologic inhibition might be required in order to achieve a therapeutic effect.

The findings of Wang et al are quite interesting given the well-established function of several other subunits of the SWI/SNF complex as tumor suppressors. There is an emerging theme that the cancer-associated mutations do not inactivate the SWI/SNF complex, but rather result in aberrant function of the residual complex (Wang et al., 2009; Oike et al., 2013). Consequently, it is an exciting possibility that post-translational modifications, such as CARM1-mediated methylation of BAF155, or altered expression levels of individual SWI/SNF subunits (Liu et al., 2011) may also alter SWI/SNF function in a manner that can facilitate, or block, oncogenesis. It will also be of interest, and of potential therapeutic relevance, to elucidate the mechanisms by which modifications and alterations affect the function of this frequently mutated tumor suppressor complex.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bedford MT, Clarke SG. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol Cell. 2009;33:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland RA, Solomon ME, Richon VM. Protein methyltransferases as a target class for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:724–732. doi: 10.1038/nrd2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoch C, Hargreaves DC, Hodges C, Elias L, Ho L, Ranish J, Crabtree GR. Proteomic and bioinformatic analysis of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes identifies extensive roles in human malignancy. Nat Genet. 2013;45:592–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Gramling S, Munoz D, Cheng D, Azad AK, Mirshams M, Chen Z, Xu W, Roberts H, Shepherd FA, et al. Two novel BRM insertion promoter sequence variants are associated with loss of BRM expression and lung cancer risk. Oncogene. 2011;30:3295–3304. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oike T, Ogiwara H, Tominaga Y, Ito K, Ando O, Tsuta K, Mizukami T, Shimada Y, Isomura H, Komachi M, et al. A synthetic lethality-based strategy to treat cancers harboring a genetic deficiency in the chromatin remodeling factor BRG1. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5508–5518. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteege I, Sevenet N, Lange J, Rousseau-Merck MF, Ambros P, Handgretinger R, Aurias A, Delattre O. Truncating mutations of hSNF5/INI1 in aggressive paediatric cancer. Nature. 1998;394:203–206. doi: 10.1038/28212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Sansam CG, Thom CS, Metzger D, Evans JA, Nguyen PT, Roberts CW. Oncogenesis caused by loss of the SNF5 tumor suppressor is dependent on activity of BRG1, the ATPase of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8094–8101. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BG, Roberts CW. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:481–492. doi: 10.1038/nrc3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JI, Lessard J, Crabtree GR. Understanding the words of chromatin regulation. Cell. 2009;136:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, et al. 2014 this issue of Cancer Cell. [Google Scholar]