Abstract

Although endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are useful in many applications including cell-based therapies, their use is still limited due to issues associated with cell culture techniques like a low isolation efficiency, use of harmful proteolytic enzymes in cell cultures, and difficulty in ex vivo expansion. Here, we report a tool to simultaneously isolate, enrich, and detach EPCs without the use of harmful chemicals. In particular, we developed magnetic-based multi-layer microparticles (MLMPs) that (1) magnetically isolate EPCs via anti-CD34 antibodies to avoid the use of Ficoll and harsh shear forces; (2) provide a 3D surface for cell attachment and growth; (3) produce sequential releases of growth factors (GFs) to enrich ex vivo expansion of cells; and (4) detach cells without using trypsin. MLMPs were successful in isolating EPCs from a cell suspension and provided a sequential release of GFs for EPC proliferation and differentiation. The cell enrichment profiles indicated steady cell growth on MLMPs in comparison to commercial Cytodex3 microbeads. Further, the cells were detached from MLMPs by lowering the temperature below 32 °C. Results indicate that the MLMPs have potential to be an effective tool towards efficient cell isolation, fast expansion, and non-chemical detachment.

Keywords: Endothelial progenitor cells, Magnetic nanoparticles, Cell separation, Thermo-responsive polymers, Controlled growth factors release

1. Introduction

Stem cells such as endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) have great promise as a renewable source of cells for basic and applied research. For instance, cell-based therapies use EPCs to treat patients with cardiovascular diseases including ischemic heart disease, in-stent restenosis, and peripheral arterial occlusive disease [1,2]. EPCs differentiate into endothelial cells (ECs) and contribute to tissue repair and neovasculature homeostasis by participating in angiogenesis and arteriogenesis [3]. EPCs can be isolated from one of their major sources including peripheral blood, umbilical cord blood, embryo, and bone marrow. However, a major limitation with the EPCs is their limited availability in the sources. For example, the number of EPCs present in peripheral blood of healthy humans is only 0.01%–0.0001% of total mononuclear cells [4]. Moreover, it requires several days of in vitro cultures to produce a great enough number of EPCs to be used in cell-based therapies [4,5].

Several cell isolation and expansion techniques have been developed to generate enough numbers of cells including stem cells for cell-based therapies. Cell isolation methods such as Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifuge [6], fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [7], magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) beads [8] have been used extensively over the last decade. In addition to cell isolation, various cell expansion technologies including microbeads like Cytodex3 microbeads [9] for cell expansion have been developed. These techniques have shown some degree of success, but can be used only for a single purpose, either cell isolation or cell expansion. In addition, each of these procedures is hampered by serious limitations. In particular, harsh chemicals, high shear forces, low isolation efficiency, and elaborate culture time is often associated with the Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifuge for cell isolation [6]. FACS requires fluorescent labeling of the cells and the equipment is very expensive [7]. Further, MACS beads do not support cell expansion and do not provide any proliferation or differentiation growth factors (GFs) [8]. Finally, Cytodex3 microbeads cannot be used for cell isolation, do not provide proliferation or differentiation GFs, and require harmful proteolytic enzymes for cell detachment [9]. In general, all the cell expansion techniques use trypsin and ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) that affect the cellular functionality through every passage by cleaving the cellular proteins [10]. In an effort to avoid the use of proteolytic enzymes, Tamura et al. [11] developed poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-grafted polystyrene microbeads to support cell adhesion and detachment in response to temperature alteration. However, these microbeads are not useful for cell-selective isolation from a crude sample and do not provide enrichment GFs for cell expansion.

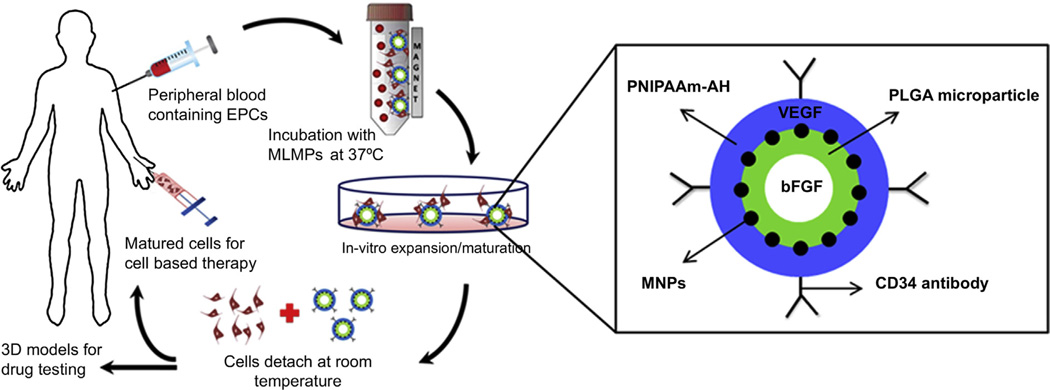

Therefore, to overcome the limitations of currently available cell isolation and expansion techniques and owing to the advantages of EPCs, we report simultaneous cell separation, proliferation, differentiation, and detachment on a 3D surface of magnetic-based multi-layer microparticles (MLMPs). The aim of research was to develop MLMPs that can be used for magnetic EPC separation, enrichment, and detachment. The MLMPs contain four layers as shown in Fig. 1: (1) CD34 antibodies at the particle surface for selectively targeting EPCs in a cell mixture or blood/crude sample. The identified unique cell surface markers for EPC isolation include CD34, CD133/AC133, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2, and kinase domain receptor. Of these, CD34 is the most frequently used marker [12,13]. (2) An outer shell of thermo-responsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-allylamine) (PNIPA-AH) to provide a surface for cell attachment and detachment depending on temperature alteration. At temperatures higher than its lower critical solution temperature (LCST, 32–34 °C), PNIPA-AH becomes hydrophobic, supporting the cell adhesion, whereas at temperatures below the LCST, PNIPA-AH becomes hydrophilic, detaching the cell non-invasively without using proteolytic enzymes. This layer also contains VEGFs which will rapidly be released for EPC proliferation [14,15]. (3) Iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) add magnetic content to the MLMPs for magnetic cell separation, and (4) a biodegradable core of poly(lactide-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microparticles containing basic fibroblast GFs (bFGFs) will eventually be released as PLGA degrades for EPC differentiation [15,16]. The hypothesis is that, when mixed with a cell suspension, only EPCs attach to the MLMPs surface; the cell-particle complexes can be isolated using an external magnetic force; the isolated cells can adhere to the outer layer of PNIPA-AH when incubated at 37 °C; a rapid release of VEGFs from PNIPA-AH and a slow and sustained release of bFGFs from PLGA can enrich EPCs to generate a large-scale suspension culture; and the cells can be detached from the PNIPA-AH surface at the temperatures below the LCST.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of MLMP application in EPC isolation, enrichment, and detachment (left). Magnified schematic of MLMP depicting layer-by-layer assembly of antibodies, polymers, GFs and MNPs (right).

2. Experimental section

2.1. Synthesis of MLMPs

All the chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich and used without further purification, if not mentioned. GFs-loaded MLMPs were synthesized by a layer-by-layer approach. First, PLGA microparticles were synthesized by a double emulsion technique [17,18]. Briefly, aqueous solution of bFGFs (8 ng/ml, 1 ml) was added drop-wise to the oil phase of PLGA (2% w/v, 50:50, with carboxyl end groups, Lakeshore Biomaterials, Birmingham, AL) solution in dichloromethane (5 ml). The resultant primary emulsion solution was then added drop-wise to the aqueous solution of polyvinyl alcohol (0.5% w/v, 20 ml) to form microparticles. After allowing solvent evaporation, the particles were washed via centrifugation (1000 rpm for 5 min for each wash, thrice), collected via freeze-drying, and stored at −20 °C for further use. The wash samples (supernatants) were collected to quantify bFGFs loading efficiency.

Second, iron oxide MNPs (Meliorum technologies, Rochester, NY) were functionalized with amine and silane groups as previously described [19,20]. Briefly, MNPs (10 nm diameter, 74.24 mg) were dispersed in a mixture of DI water and ethanol (1:99) by sonication at 30 W. After 10 min, acetic acid (3 ml) was added, sonication was continued for 10 min, reaction was transferred to magnetic stir plate, to which (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (283.1 µl) and vinyltrimethoxysilane (243.5 µl) were added, and the reaction was stirred vigorously for 24 h. The particles were washed thrice with a mixture of DI water and ethanol. Surface functionalized MNPs were then conjugated to the PLGA microparticles by carbodiimide chemistry [21]. Briefly, PLGA microparticles (20 mg) were added to 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid buffer (MES, 0.1 m, 90 ml), stirred for 20 min, and then N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 160 mg) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, 160 mg) were added. Meanwhile, in a separate beaker, surface functionalized MNPs (14 mg) were sonicated with MES buffer (5 ml) at 40W and then added drop-wise to the reaction, followed by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 2 mg), and the reaction was stirred for 6 h. MNPs-conjugated PLGA microparticles were washed thrice with DI water, collected using a magnet, freeze-dried, and stored at −20 °C for further use.

Finally, N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAAm) and allylamine (AH) were copolymerized on the surface of MNPs-conjugated PLGA microparticles by radical polymerization [21,22]. Briefly, MNPs-conjugated PLGA microparticles (28 mg) were sonicated with DI water (90 ml) at 40 W for 10 min, transferred to a magnetic stir plate, and NIPAAm (300 mg), AH (300 µl), N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (BIS, 10.5 mg), and SDS (1.5 mg) were added to the reaction. After 10 min, ammonium persulfate (APS, 30 mg) and N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED, 39 µl) were added and the reaction was stirred for 4 h in N2 environment. MLMPs were washed thrice with DI water, collected using a magnet, and freeze-dried. Further, VEGFs were loaded in the PNIPAAm-AH layer by adding aqueous solution of VEGFs (8 ng/ml, 0.5 ml) to MLMPs (20 mg) in DI water (5.5 ml). The solution was placed on a shaker at 4 °C for 3 days to allow VEGFs absorption in the PNIPAAm-AH. After 3 days, VEGFs-loaded MLMPs were collected by a magnet and the supernatant was collected to quantify VEGFs loading efficiency indirectly.

2.2. Particle characterization

The particles were characterized at each step of the synthesis procedure by particle sizer with dynamic light scattering (DLS, Brookhaven Instruments, Holtsville, NY) detector and scanning electron microscope (SEM, S-3000N, Hitachi, Pleasanton, CA) to analyze the particle size, surface charge, and surface morphology. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI Technai G2 Spirit BioTWIN, Hillsboro, OR) was performed to observe the presence of multiple layers within the MLMPs. Further, Fourier transform infrared spectroscope (FTIR, Nicolet 6700 FT-IR, Thermo Scientific, Madison, WI) was used to analyze the presence of various chemical bonds in the particle structure during the synthesis. All the sample preparations followed standard procedures [21,23,24]. Moreover, GFs-loaded MLMPs were analyzed for GFs release characteristics. Briefly, the samples were incubated in PBS at 37 °C on a shaker. At predetermined time points over 14 days, the supernatants containing released GFs were collected by separating MLMPs using a magnet, and analyzed using VEGF and bFGF ELISA kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Antibody conjugation

MLMPs were conjugated with CD34 antibodies (anti-human CD34 antibodies, Biolegend, San Diego, CA) via carbodiimide chemistry. Briefly, antibody (10 µg) was added to MES buffer (0.5 ml) along with EDC and NHS (5 mg each) and incubated at room temperature on an orbital shaker. After 1 h of shaking, MLMPs (1 mg) were dispersed separately in MES buffer (0.5 ml) and added to the reaction that was continued for 4 h on the shaker. The antibody-conjugated MLMPs were collected using a magnet and washed thrice with DI water to remove non-conjugated antibodies. Moreover, to determine antibody conjugation efficiency, FITC/Alexa Fluor 647-labeled CD34 antibodies were conjugated to the MLMPs as mentioned above. The antibody-conjugated MLMPs were observed under an enhanced fluorescent optical microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). In addition, the washed (supernatant) samples were analyzed for their fluorescent intensities that were compared to the fluorescent intensities of the standard concentrations of FITC/Alexa Fluor 647-labeled CD34 antibodies.

2.4. Optimization studies

Quantitative analysis of EPC isolation was performed based on three independent factors: (1) incubation time, (2) MLMP concentration, and (3) CD34 antibody concentration. In general, CD34 antibody-conjugated MLMPs and EPCs were mixed together in endothelial basal medium (EBM-2) supplemented with SingleQuots endothelial growth supplement (EGM-2) (Clonetics, Lonza, Allendale, NJ) and incubated in a 50 ml disposable bioreactor tube (Trasadingen, Switzerland) on a rotator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 supply (see Supporting Information for cell culture details). After the incubation period, cell-particle complexes were isolated using a magnet and washed several times with PBS pre-warmed to 37 °C to wash out non-specific cell adhesion to the MLMPs. The washed cell-particle complexes were then left in the room temperature to allow cells to detach from the MLMP surface. MLMPs were separated from the detached cells that were analyzed for isolation efficiency.

First, the effects of incubation time (1, 2, 4 and 6 h) on cell isolation were studied with MLMPs (1 mg) conjugated with antibody (5 µg). The time at which maximal cell isolation occurs was selected for further optimization studies. Second, the effects of MLMP concentration (0.2, 0.75, 1, 2 and 5 mg/ml) on cell isolation efficiency were evaluated while keeping the number of cells (100,000) and antibody concentration (5 µg/mg MLMPs) constant. From this study, the MLMP concentration that isolated the most number of cells was chosen for later studies. Next, the effects of antibody concentration (1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 µg/mg MLMPs) on cell isolation efficiency was evaluated, keeping the number of cells (100,000) and MLMP concentration (from previous study) constant. Finally, the antibody concentration that isolated the most number of cells was chosen for later studies. To quantify the isolated cells, Picogreen DNA assays (Invitrogen) were performed and cross-referenced with that of a hemacytometer count. Direct analysis involved the quantification of DNA from the cells detached from the particle surface, while indirect quantificationwas also performed on the washed supernatant consisting of non-isolated cells.

2.5. Characterization of cell-particle complexes

The cell-particle complexes were characterized to see cell adhesion on the particle surface. The complexes were imaged using SEM and LIVE/DEAD assays (Invitrogen). Briefly, for SEM, the complexes were washed several times with PBS pre-warmed at 37 °C and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution. The cells were then dehydrated in a sequential ethanol solutions followed by lyophilization with tert-butyl alcohol and osmium tetroxide. The specimen were sputter coated with silver and SEM was then performed at low accelerating voltages of 2 kV [11]. In addition, LIVE/DEAD assays were performed on the cell-particle complexes with calcein (0.75 µm) and ethidium homodimer-1 (0.25 µm) as per manufacturer’s instructions [25]. The dye was added and incubated at 37 °C for 40 min. The samples were washed with PBS and imaged at 20× magnification with the appropriate filters to detect live and dead cell populations on the particle surfaces.

2.6. Cell expansion

Taking advantage of sequential release of GFs, cell expansion on the MLMPs surface was studied over a period of time. The experimental and control groups for this study included EPCs cultured over (1) GFs-loaded MLMPs incubated with GFs-deprived media, (2) empty MLMPs incubated with GFs-supplemented media, (3) empty MLMPs incubated with GFs-deprived media, (4) Cytodex3 microbeads (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) incubated with GFs-deprived media, and (5) Cytodex3 microbeads incubated with GFs-supplemented media. Cell were cultured with all these groups in 50 ml disposable bioreactor tubes on a rotator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 supply as explained earlier. The cell-particles complexes were separated from the suspension using a magnet and the supernatant was analyzed to quantify the initial isolation efficiency. The isolated cell-particle complexes were then cultured over a week with media change every 3 days. The cells grown on the particles after specific days of culture were detached from the particle surface, using temperature changes in case of MLMPs and using trypsin EDTA (Invitrogen) in case of Cytodex3 microbeads. Pico-green DNA assays were also performed to quantify the total cell DNA, which was then converted to percentage cell growth.

2.7. Cell detachment

The effects of time (30, 60 and 120 min) at the room temperature on cell detachment from the particle surface were evaluated, keeping the MLMP concentration and CD34 antibody concentration constant (chosen from optimization studies). The cell detachment from particle surface was performed as described earlier and the time at which the number of detached cells was saturated was chosen as optimum detachment time. The detached cells at various time points were quantified using DNA assays as described earlier. After detachment, the cells were further cultured on a glass slide and incubated at 37 °C for 12 h to allow cell adhesion and growth. These samples were observed under a microscope and compared with normal cultures.

2.8. Cell isolation from a mixture of cells and human peripheral blood

Cell isolation from a mixture of two different cell populations was performed to prove the selective isolation efficacy of the MLMPs. Two cell types, HDFs and EPCs (100,000 counts each), were pooled together and mixed with CD34 antibody-conjugated MLMPs. The cell isolation and detachment was performed using previously optimized values as described earlier. The detached cells from the cell-particle complexes were analyzed by immunostaining of CD34 antibodies and by the uptake of acetylated low-density lipoprotein labeled with the fluorochrome Dil (Dil-Ac-LDL, Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA). Briefly, the detached cells were washed several times with PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The cells were then incubated with Dil-Ac-LDL at 37 °C for 4 h. The cells were washed thrice using PBS to remove excess of the stain. The cells were then immunostained with FITC-labeled CD34 antibodies (2.5 µg/ml) and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. The excess of the antibodies from the cells surface were washed off thrice using PBS. Finally, the cell nuclei were then stained with DAPI for about a minute in the dark. The cells were then imaged using fluorescent optical microscope. Moreover, the EPCs were also isolated from human peripheral blood using MLMPs and the cell isolation efficiency was compared with traditional Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifuge procedure (Supporting Information).

2.9. Statistical analysis

The results obtained were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with p < 0.05 and post hoc comparisons (StatView, Version 5.0.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All the experiments were repeated multiple times with a sample size of 8. All the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation if not specified.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of MLMPs

MLMPs were synthesized by a step-by-step process involving 3 major phases, i.e. synthesis of the PLGA microparticles, followed by coating with surface functionalized MNPs and thermo-responsive polymer (PNIPAAm-AH). The schematic depicted in Fig. 1 outlines various layers of the particle and the GFs loaded within them. MLMPs were characterized at each step of synthesis for its surface morphology, particle diameter and chemical composition. The outer layer (PNIPAAm-AH) of MLMPs was investigated separately for its cytocompatibility, transition between hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity, and its effects on cell adhesion and detachment. It was observed that PNIPAAm-AH is highly cytocompatible with EPCs and has a LCST of 33 °C (Supplementary Figs. S1–S3).

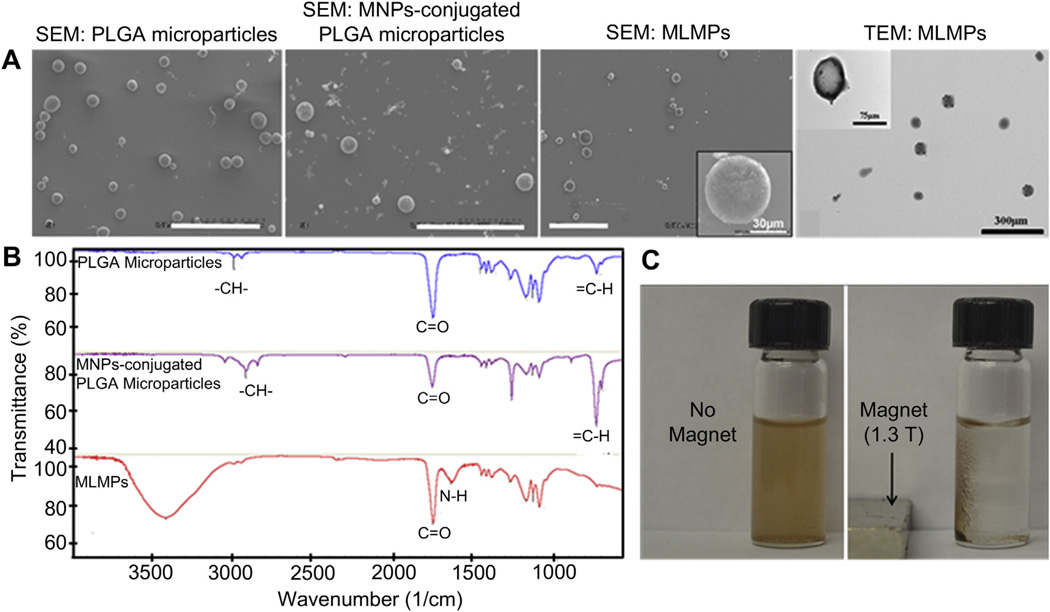

A spherical morphology of the particles and the changes in surface roughness in each step of synthesis were observed in SEM. SEM of PLGA microparticles (Fig. 2A) shows a very smooth surface, which became rougher after conjugating MNPs on the surface of PLGA microparticles (Fig. 2B) and polymerizing PNIPAAm-AH on the surface of MNPs-conjugated PLGA microparticles (Fig. 2C). The entire structure of the MLMPs was in the size range of 50–100 µm (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Table S1). Multiple layers in the MLMPs were observed in TEM (Fig. 2D). In addition, a successful polymerization of NIPAAm and AH monomers onto the MLMPs was confirmed via FTIR. As shown in Fig. 2E, FTIR spectrum of MLMPs was compared with that of PLGA microparticles and MNPs-conjugated PLGA microparticles to confirm the presence of PNIPAAm-AH on the MLMPs surface. The vinyl bonds (700–800 cm−1) on silane-coated MNPs disappeared in FTIR spectrum of MLMPs. The –CH– stretching vibration (2936–2969 cm−1) of the polymer backbone and two peaks in between 1600 and 1750 cm−1 correspond to the bending frequency of the amide N–H group and amide carbonyl group, respectively, which confirms the presence of amine corresponding to the AH. From SEM and FTIR observations, it can be confirmed that PNIPAAm-AH has been coated onto the surface of the MNPs-conjugated PLGA microparticles.

Fig. 2.

Physicochemical characterizations of microparticles. (A) SEM image of PLGA microparticles (avg. size 41 µm), MNPs-conjugated PLGA microparticles (avg. size 53 µm), MLMPs (avg. size 83 µm) (scale bars: 300 µm), and TEM image of MLMPs representing internal structure of the microparticles. (B) FTIR spectra of PLGA microparticles, MNPs-conjugated PLGA microparticles, and MLMPs. (C) Photographs of MLMPs showing particle suspension in absence of a magnet and recruitment of particles in the magnetic field (1.3 T) generated by a magnet.

Magnetic properties of the MLMPs were tested and observed as shown in Fig. 2F. Presence of MNPs adds magnetic content to the MLMPs that can be attracted towards a magnetic field using a magnet. In the absence of magnetic field, the MLMPs are well dispersed in the solution. Further, the superparamagnetic properties of the MLMPs were tested in detail using vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, KLA-Tencor EV7, San Jose, CA) and compared with that of bare MNPs (Supplementary Fig. S4). This indicates that the MLMPs possess magnetic properties enough for magnetic cell separation.

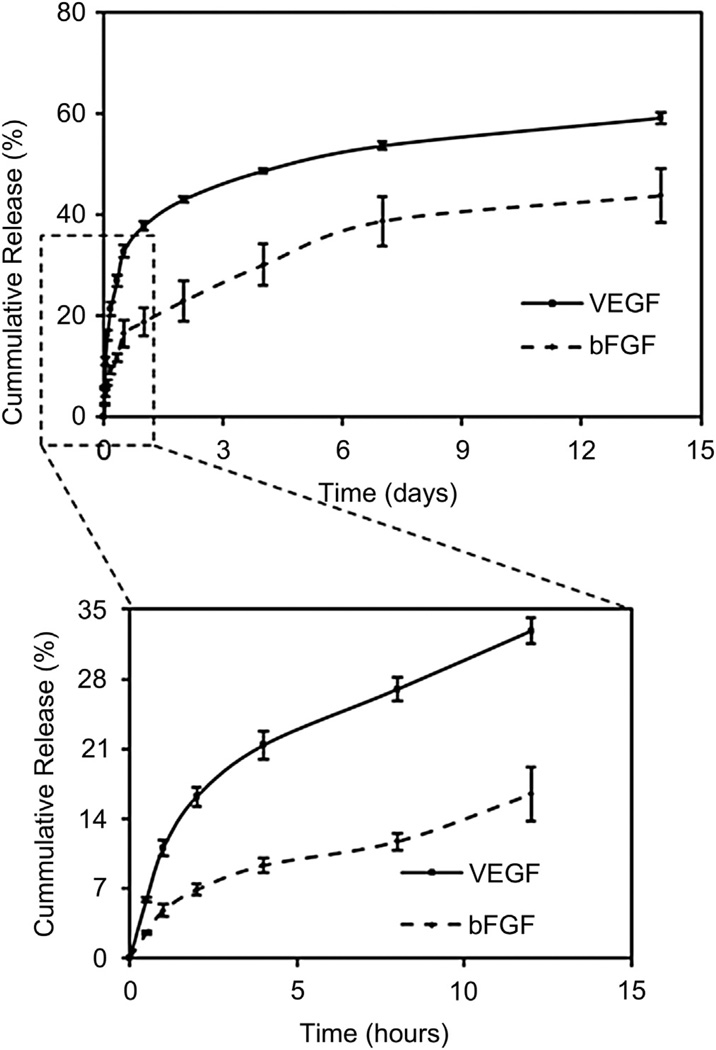

3.2. GFs release profiles

GFs release profiles from core (bFGFs) and shell (VEGFs) were evaluated at individual time points over a period of 14 days. As shown in Fig. 3, both the release profiles indicated an initial burst release followed by a sustained release. The maximal growth factor release of VEGFs from the shell was about 60% at 14 days, while that of bFGFs from the core was about 40%. Specifically, in the initial time points (within 5 h) of the release, there was a significantly higher release of VEGFs (20%) than that of bFGFs (7%). By 12 h of release, the VEGFs release steepened to 32%, while the bFGFs remained at only 12%. The lag phase observed in case of bFGFs is essential so that the bFGFs is available at latter time points for cell differentiation.

Fig. 3.

Release profiles of VEGFs (from the shell) and bFGFs (from the core) over 14 days. Initial release time points (enlarged) indicating lag phase in the bFGFs (differentiation GFs) encapsulated in the core.

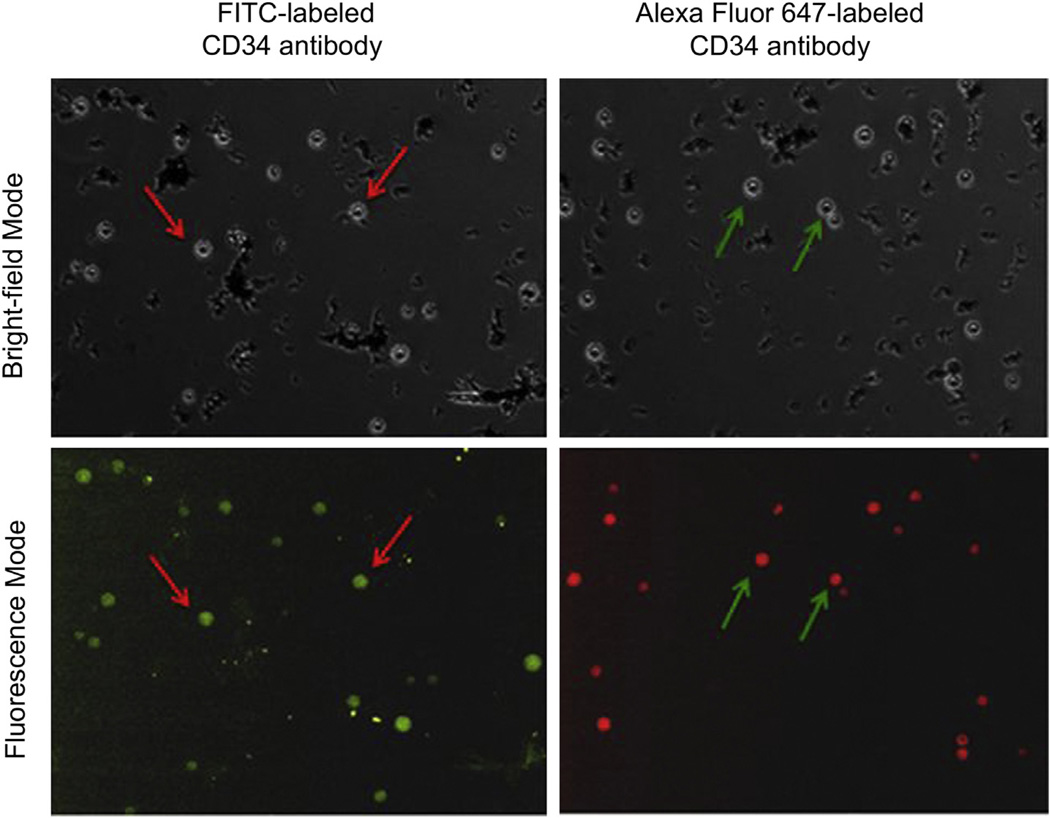

3.3. Antibody conjugation

Qualitative and quantitative confirmation of antibody conjugation was performed by conjugating FITC-labeled or Alexa Fluor 647-labeled CD34 antibodies to the MLMPs. Fig. 4 shows images of fluorescently labeled particles compared with that at monochrome settings. A bright green (in the web version) color from FITC-labeled CD34 antibodies and a bright red (in the web version) color from Alexa Fluor-labeled CD34 antibodies were observed on the MLMPs surface in the fluorescence mode. The antibody conjugation efficiency was measured via indirect method by analyzing supernatant containing non-conjugated antibodies. These observations suggest successful conjugation of CD34 antibodies to the MLMPs.

Fig. 4.

MLMPs conjugated with FITC- and Alexa Fluor 647-labeled CD34 antibodies in monochrome and fluorescence mode.

3.4. Optimization studies

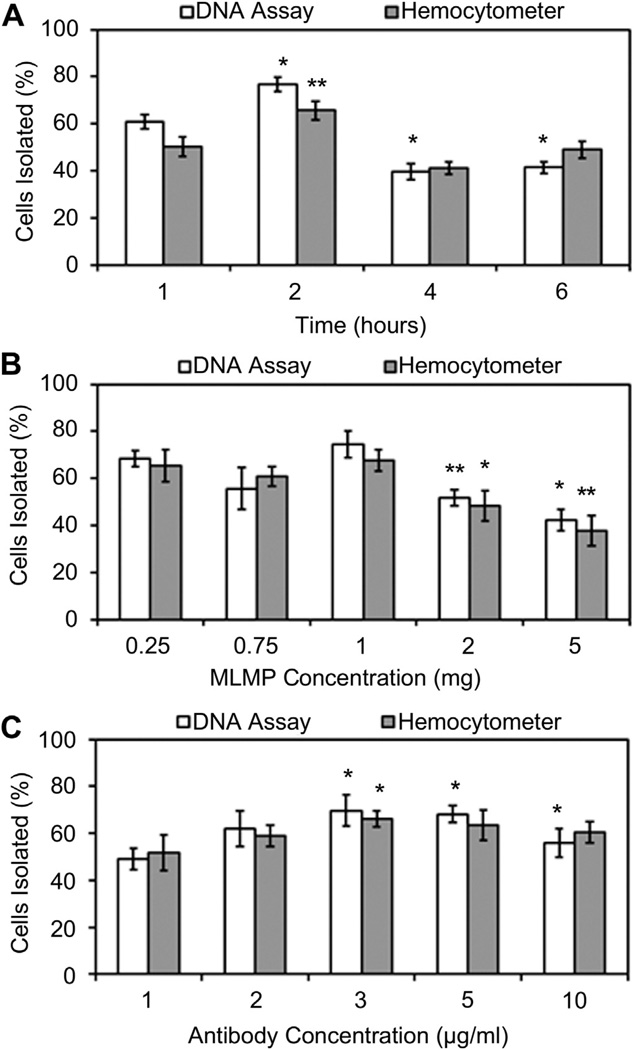

Fig. 5 shows the optimization results of the system with respect to various parameters: incubation time, MLMPs concentration, and antibody concentration. First, while optimizing the particle incubation time with the cells the highest cell isolation efficiency of 77% was observed after 2 h of incubation (Fig. 5A), compared to that of 1, 4 and 6 h. Second, compared to 0.25, 0.75, 2, and 5 mg MLMPs, the maximum cell isolation efficiency (74%) was observed with 1 mg particles (Fig. 5B), keeping the incubation time constant at 2 h. Finally, the highest cell isolation efficiency of 69% was obtained with 1 mg MLMPs conjugated with 3 µg/mg antibody (Fig. 5C). Hemacytometer readings also generated similar results compared to that obtained from the Picogreen DNA assays. Summarizing, the maximum cells can be isolated by 3 µg antibody-conjugated 1 mg particles within 2 h of incubation. These optimized values were used for all further studies.

Fig. 5.

Cell isolation optimization based on (A) EPCs and particles incubation time, (B) MLMP concentration, and (C) CD34 antibody concentration (*p < 0.05).

3.5. Cell expansion

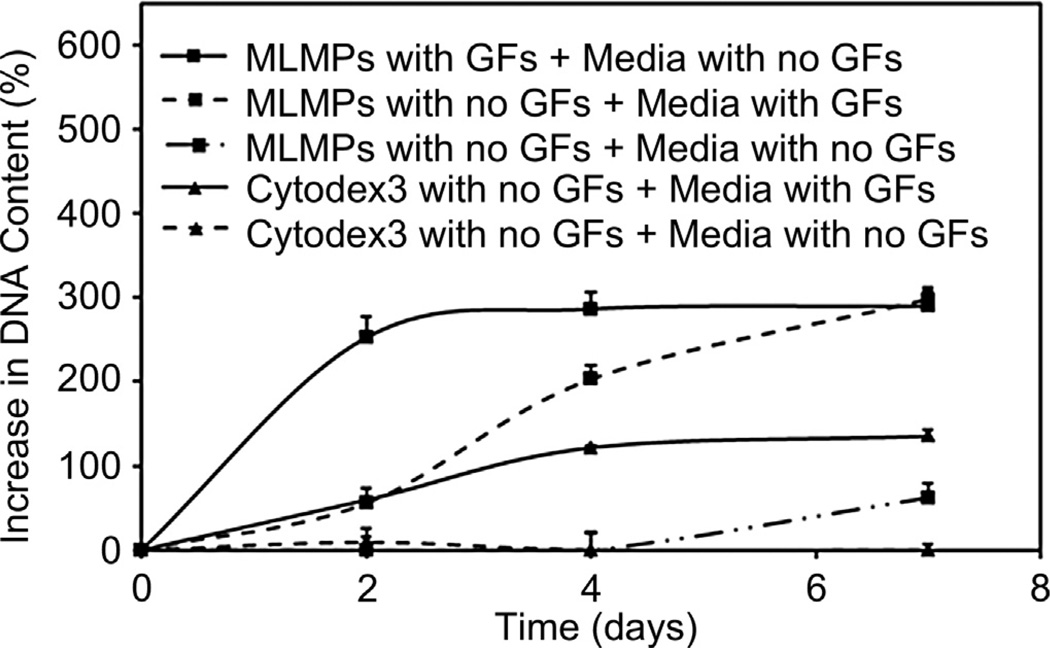

EPC proliferation on the surface of GFs-loaded MLMPs was compared with that of commercially available Cytodex3 microbeads (Fig. 6). The cell proliferation graphs were plotted by considering the initial cell seeding as 100%. Cell proliferation rates varied among the different groups. GFs-loaded MLMPs showed a significant increase in cell growth rates until 7 days. The percent increase in DNA was approximately 300%. Moreover, cells cultured with MLMPs in media containing GF also showed similar profile, but slower growth rate with 290% of DNA increase after 7 days. Cell growth over commercial Cytodex3 beads was a steady increase (135% increase) over time, which was significantly lower than that of MLMPs. Control groups cultured in media deprived of GFs indicated no increase in the cell proliferation.

Fig. 6.

Cell expansion profiles showing increase in DNA content of EPCs proliferating on MLMPs and Cytodex3 microbeads at different culture conditions.

3.6. Cell detachment

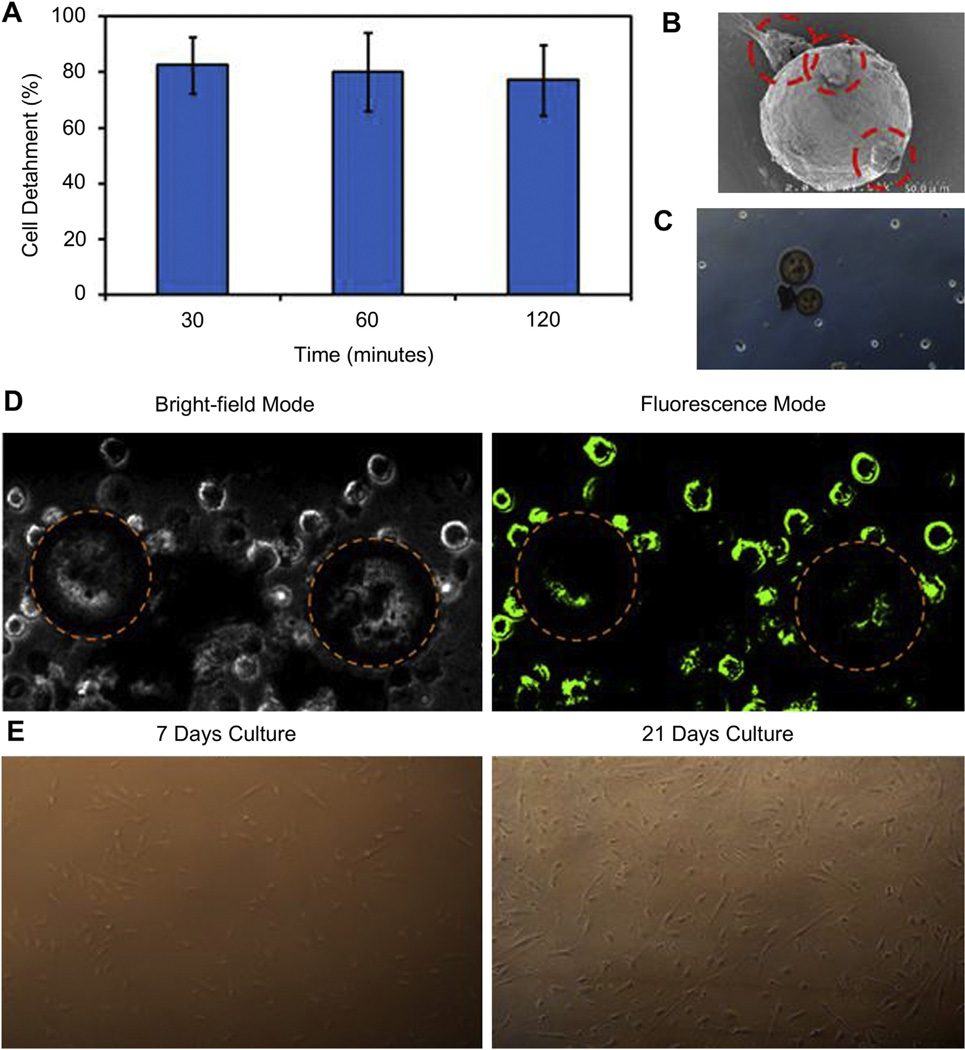

Fig. 7A shows the cell detachment in response to temperature change as a function of time. A detached percentage as high as 80% was observed during the first 30 min and the detachment efficiency remained saturated for 120 min. No significant differences were observed among all three time points. In addition, Fig. 7B shows the SEM image of only a few cells attached to the particle surface after detachment. Further, microscopic images (Fig. 7C) and LIVE/DEAD assays images (Fig. 7D) of the detached cells indicate maximal cell detachment and minimal attachment over the particle surface. The particles are outlined for the purpose of clarity. Most cells were alive (green), and no dead cell population (red) was observed. Further, the detached cells were cultured in culture flasks and grown over time. No morphology differences were observed as in Fig. 7E for cell cultures after 7 and 21 days, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Cell detachment from MLMPs at room temperature. (A) EPCs detachment efficiency as a function of time. (B) SEM image of cell–particle complex showing presence of EPC (dashed red circles) attached over MLMP surface. (C) Microscopic image of EPCs detached from MLMPs over 30 min (D) LIVE/DEAD assay images showing live EPCs stained in green with a small population on the surface of MLMPs (dashed circles represent MLMPs) in monochrome and fluorescence mode, (E) Photomicrographs of growth and proliferation of detached EPCs at 7 and 21 days. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

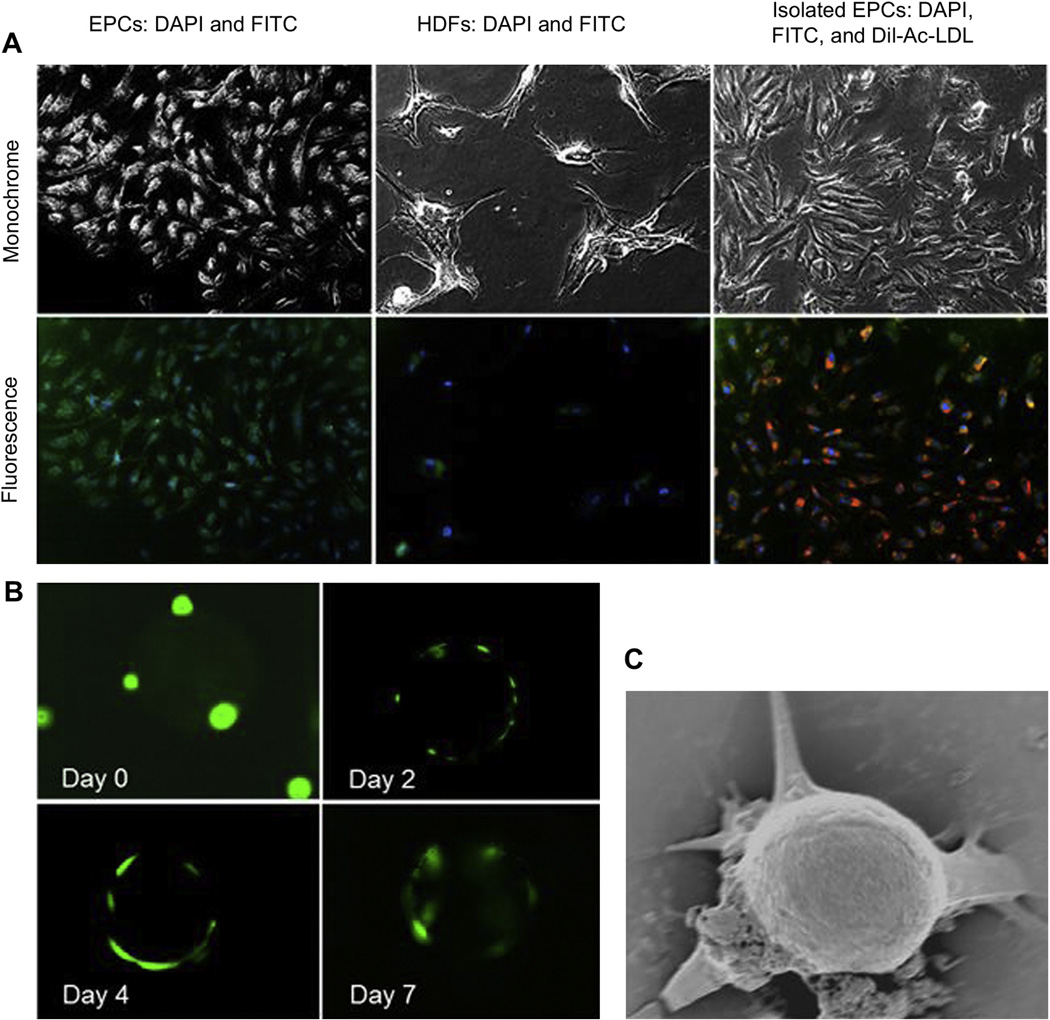

3.7. Cell isolation from a mixture of cells and human peripheral blood

First, both the cell lines, HDFs and EPCs, were tested for the presence of CD34 surface markers by immunostaining with fluorescently-labeled CD34 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 8A, EPCs showed the presence of CD34 markers, while HDFs did not. Second, EPC isolation from the mixture containing HDFs and EPCs was performed. The isolated populations were then cultured and characterized for the specificity of EPC isolation. The isolated cells were characterized as only EPCs by the presence of FITC labeling of CD34 markers, uptake of Dil-Ac-LDL, and the cell morphology (Fig. 8A). The isolated cell-particle complexes were further characterized at various time points using LIVE/DEAD staining and SEM imaging to show the presence of the EPCs on the particle surface. LIVE/DEAD staining indicated the increase in cell number over the particle surface with time (Fig. 8B). All the isolated cells were alive and healthy. In addition, SEM images also verified the presence of cells over the particle surfaces (Fig. 8C). Extensions or sprouts from the cells were observed as well as the presence of extracellular matrix, perhaps due to minor stress exerted during rotary incubation. Moreover, the EPCs were also efficiently isolated from human peripheral blood compared to that using Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifuge procedure in our preliminary data (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Fig. 8.

(A) Immunostaining of EPCs shows presence of CD34 surface markers (green). HDFs do not express CD34 markers (nuclei stained with DAPI). EPCs isolated from a mixture of EPCs and HDFs show the presence of CD34 markers as well as Dil-Ac-LDL taken up by the isolated cells (red). (B) LIVE/DEAD assay images of cell–particle complex show increase in EPC proliferation over MLMP surface at increasing incubation period. (C) SEM image of cell–particle complex indicating attachment and proliferation of cells over the particle surface. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

EPCs, bearing therapeutic potential, can be used as indicators in cardiovascular disorders, with low EPC numbers indicating a higher risk of atherosclerosis [3]. Other than the cardiovascular disorders, the EPCs have been used to treat cerebrovascular diseases due to their capability of neovascularization in the presence of VEGFs [3,26]. Moreover, the EPCs have been explored as therapeutic carriers that are capable of inducing controlled tumor cell apoptosis [27]. The use of EPCs possesses many advantages not only based on their immense potential for cell-based therapy and diagnosis, but also due to the fact that they do not pose any ethical concerns like those of embryo stem cells [3]. Highlighting the advantages of EPCs, efficient and improved isolation techniques are a prerequisite for their utilization in therapy and diagnosis. Here, we attempted to isolate, enrich, and detach the cells using unique multi-layer microparticles to overcome the limitations of the conventional techniques. Cell isolation by MLMPs is advantageous based on the following reasons; (1) increased isolation specificity by conjugation of specific antibodies over the particle surface, (2) ease of cell separation based on its magnetic properties, (3) delivery of GFs: VEGFs for cell proliferation and bFGFs for cell differentiation, and (4) the facilitation of proteolytic enzyme-free cell detachment with the help of temperature-responsive polymeric surfaces. The proposed technique of cell isolation is simple and lacks intense procedures and particular skills.

Culture environments for stem cells are very critical and play an important role in cellular functionalities [28]. For instance, 3D culture environments have been shown as physiologically more suitable for stem cells expansion and differentiation compared to 2D culture environments [29]. Our MLMPs provide 3D culture environments that may positively influence the cellular functionalities such as migration, proliferation, lineage specificity, and differentiation. Since the cells are in contact with the outer layer of MLMPs, characteristics of PNIPAAm-AH and its cytotoxic effects on EPCs play a vital role. PNIPAAm-based thermo-responsive polymers have been well-studied for cell sheet engineering due to their reversible phase transitions at the LCST [30]. The LCST of the PNIPAAm-AH (33 °C, Supplementary Fig. S1) was a characteristic temperature above which the polymer became hydrophobic, supporting the EPCs adhesion and proliferation. And below the LCST, the polymer became hydrophilic, detaching the EPCs without the use of proteolytic enzymes such as trypsin and EDTA. Temperature-responsive cell detachment and mechanical dissociation is known to allow better subsequent cellular adhesion over the surfaces in comparison to enzymatic digestion [31]. Moreover, PNIPAAm-based thermo-responsive polymers have been shown as non-cytotoxic materials [21,22]; similarly in our studies, the polymer did not reveal any advert toxicity to EPCs for 48 h of exposure (Supplementary Fig. S2).

As for the MLMPs, the large sized particles (average diameter: 83 µm) were produced so that they provide sufficiently large surface area for relatively smaller cells (~18 µm in length) to adhere and proliferate. Further, the presence of MNPs facilitated the ease of separation of cell-particle complexes from the cell suspension. The magnetic property of MLMPs also offers the advantage of ease in changing media and performing any experiments because they can be immobilized over a surface in the presence of a magnetic field. Bearing magnetic properties is a major advantage over current techniques such as Ficoll-Paque and Cytodex3 microbeads that require the centrifugation and proteolytic enzymes during the course of cell culture [32]. Although the MNPs are sandwiched between PLGA and PNIPAAm-AH layers, the polymeric layer do not compromise the magnetic properties of the MLMPs (Supplementary Fig. S3).

To achieve a sequential release of GFs, the EPCs proliferation inducing VEGFs were loaded in the thermo-responsive polymeric shell and the EPCs differentiation inducing bFGFs were encapsulated in the PLGA core. The rationale was to release VEGFs first to increase the number of cells growing over the particle surface and then induce the differentiation of these cells by a sustained bFGFs release from the particle core [14–16]. The observed GFs release kinetics was as desired for the effective proliferation and timely maturation. Another benefit of adding GFs in the particle design instead of supplementing the medium with GFs is to save the costs on expensive GFs and achieve a faster differentiation of cells by localized and targeted release of GFs (Fig. 6). PLGA was selected in our studies due to its well-known characteristics including biocompatibility, biodegradation, and the ability to provide a sustained release of payload [24,33]. However, one of the limitations during incubation and GFs release may be the degradation of PLGA core, which may affect integrity of the entire system and may also change the pH (acidify) of the medium. After the development of the proof-of-concept, in the future, PLGA needs to be replaced by a non-degradable polymer such as polystyrene, which provides functional groups from surface modification as well as sustained release profile of GFs.

EPCs express several types of surface markers such as CD34, CD113, VEGFR-2, CD31, CD144, and vWF. Since CD34 was the most predominantly utilized cell surface marker specific for human EPCs [2], we conjugated CD34 antibodies to the MLMPs to capture the EPCs as a proof-of-concept. The binding amount of CD34 antibodies can be increased by increasing the number of functional groups on the particle surface via plasma deposition method, however our conjugation efficiency was similar to or higher than previously reported numbers in case of CD34 conjugated PNIPAAm polymers [34]. After antibody conjugation, the cells and the particles were cultured in bioreactor tubes on a rotator instead of culturing in static conditions. Rotary bioreactor tubes provide the advantage of uniform cell attachment over the 3D surface, compared to that observed in static conditions, leading to higher seeding efficiencies and uniform cell attachment over the surface [35].

The stem cells isolation efficiency is affected by many factors such as incubation time, particle concentration, and/or antibody concentration. Therefore, the optimal culture conditions, at which the most number of cells were isolated, were recorded. A decreased EPCs isolation efficiency was observed during later incubation time points at 4 and 6 h (Fig. 5A). When in the incubation, the particle–particle aggregation may increase with time, which might have accounted for the low number of cells isolated with increasing time as a result of reduced surface area. The cell isolation optimization was essential for efficiency and a more accurate analysis of further cell studies such as cell isolation from a complex cell suspension.

Further, the cell expansion was studied on particle surfaces in different culture media to see if there were any differences in cell growth with GFs supplemented medium and GFs-loaded particles. Interestingly, the cell growth on MLMPs loaded with GFs was significantly higher compared to that of empty MLMPs in GFs supplemented medium (Fig. 6). Localized supply of GFs to the cells growing over the particles seems to have a better effect on cell proliferation thus emphasizing the benefit of GFs loading in the particles compared to that supplied in the medium. Encapsulating GFs in the microparticle structure is not only advantageous for cell proliferation but also in minimizing the use of expensive GFs and proteins by adding in large amounts to the medium. As for cellular differentiation, studies indicated that direct cell–cell contact has an effect on stem cell differentiation [36], while cellular gap junctions are known to play an important role in cell–cell communications and differentiation. Moreover, the material surface properties also influence cellular differentiation even in the absence of differentiation molecules such as GFs [37]. Therefore in the future, the differentiation of cells over the MLMP surface must be analyzed with respect to time and the effect of GFs.

The cell detachment efficiency is affected by incubation time of cell-particle complexes in the room temperature and surface properties of the microparticles. Within the first 30 min, 80% of the cells were detached from the MLMPs surface (Fig. 7A). Similarly, Tang et al. [38] observed about 80% cell detachment within 35 min from PNIPAAm-modified polystyrene culture plates under static conditions at 20 °C. The cell detachment from the PNIPAAm-modified surfaces at temperatures below the LCST is primarily due to the hydration of the PNIPAAm surface, which in turn becomes hydrophilic, detaching the cells. However, 100% cell detachment efficiency was not obtained in our experiments, potentially due to the antibody binding retaining the cells on the particle surface. A remedy for this problem is the use of synthetic peptides that compete with the cell-particle complexes for binding to the antibodies, in turn releasing the cells from the antibody binding. Further, if the cells over-grow on the particle surface, an intact cell sheet may form, which may not be released unless external shear breaks the cell–cell contact apart. An alternative for this limitation is merely avoiding the over-growth of the cells on the particle surface, which can be done by continuous monitoring of cell growth, detaching the cells before confluent, and adding more fresh MLMPs to the culture to provide more surface area for cell attachment. Thus, our MLMPs eliminate the use of proteolytic enzymes such as trypsin for cell detachment since trypsinization has been shown to adversely affect the cellular activities by disrupting extracellular matrix structure due to peptide cleavage [10].

Cell isolation from a complex cell mixture, such as human blood, is a critical step in obtaining a pure population of a specific cell type. As a concept proof, we demonstrated that the MLMPs were able to isolate only EPCs from a mixture of EPCs and HDFs as well as from human peripheral blood. The presence of the cells on the cell-particle complexes was shown by LIVE/DEAD staining (Fig. 8B) and SEM imaging (Fig. 8C). Images obtained by LIVE/DEAD staining indicated substantial cell populations over the particle surface, but these cells appear rounded. This may be a result of loose attachment of the cells or beginning of cell detachment from the surface due to the lowering of surrounding temperature. This limitation during imaging was tried to be kept at minimum by controlling environmental parameters. Further, the isolated EPCs from the MLMPs were confirmed by immunostaining of CD34 markers, uptake of Dil-Ac-LDL, and elongated spindle-shaped cell morphology.

5. Conclusion

The results indicate that the MLMPs have potential to serve as an alternative technology to the current cell isolation and expansion techniques. The sheer forces, associated with cell binding and elution, are minimal to negligible compared to centrifugation or filtration methods, thereby increasing the yield of isolated cells. MLMPs eliminate the use of harsh chemicals such as Ficoll and trypsin involved in conventional cell isolation and expansion techniques by the use of thermo-responsive cell detachment. Isolation using magnetic force simplifies the procedures like separation and washing which are considered to be tedious steps in conventional cell isolation methods. Thus, MLMPs provide the advantages of quick and easy process for cell isolation, enrichment, and detachment. Moreover, the enhancement of EPC numbers via GFs-loaded MLMPs to overcome their major limitation of limited availability would be useful in the diagnosis of diseases, stem cell therapy, cell transplantation, and creating in vitro 3D models for drug screening. Enhancement of EPC numbers would not only be critical for the patients’ recovery and enhance restoration and integrity of diseased tissues, but also would provide new tools and strategies in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the financial support from the American Heart Association (AHA pre-doctoral fellowship award to A.S.W. and AHA Grant-in-Aid award to K.T.N.).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.015.

References

- 1.Marsboom G, Janssens S. Endothelial progenitor cells: new perspectives and applications in cardiovascular therapies. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6(5):687–701. doi: 10.1586/14779072.6.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rafii S, Lyden D. Therapeutic stem and progenitor cell transplantation for organ vascularization and regeneration. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):702–712. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouhl RP, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Damoiseaux J, Tervaert JW, Lodder J. Endothelial progenitor cell research in stroke: a potential shift in pathophysiological and therapeutical concepts. Stroke. 2008;39(7):2158–2165. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.507251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jujo K, Ii M, Losordo DW. Endothelial progenitor cells in neovascularization of infarcted myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45(4):530–544. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawamoto A, Gwon HC, Iwaguro H, Yamaguchi JI, Uchida S, Masuda H, et al. Therapeutic potential of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2001;103(5):634–637. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li R, Nauth A, Li C, Qamirani E, Atesok K, Schemitsch EH. Expression of VEGF gene isoforms in a rat segmental bone defect model treated with EPCs. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(12):689–692. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318266eb7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Say EA, Melamud A, Esserman DA, Povsic TJ, Chavala SH. Comparative analysis of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in age-related macular degeneration patients using automated rare cell analysis (ARCA) and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan CL, Li Y, Gao PJ, Liu JJ, Zhang XJ, Zhu DL. Differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells from human umbilical cord blood CD 34+ cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2003;24(3):212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bardouille C, Lehmann J, Heimann P, Jockusch H. Growth and differentiation of permanent and secondary mouse myogenic cell lines on microcarriers. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;55(5):556–562. doi: 10.1007/s002530100595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert TW, Sellaro TL, Badylak SF. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials. 2006;27(19):3675–3683. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamura A, Kobayashi J, Yamato M, Okano T. Temperature-responsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-grafted microcarriers for large-scale non-invasive harvest of anchorage-dependent cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33(15):3803–3812. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papathanasopoulos A, Giannoudis PV. Biological considerations of mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells. Injury. 2008;39(Suppl. 2):S21–S32. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(08)70012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umemura T, Higashi Y. Endothelial progenitor cells: therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;108(1):1–6. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08r01cp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Han Y, Pang W, Li C, Xie X, Shyy JY, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase promotes the differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(10):1789–1795. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.172452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SY, Park SY, Kim JM, Kim JW, Kim MY, Yang JH, et al. Differentiation of endothelial cells from human umbilical cord blood AC133-CD14+ cells. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(7):417–422. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0988-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang N, Li D, Jiao P, Chen B, Yao S, Sang H, et al. The characteristics of endothelial progenitor cells derived from mononuclear cells of rat bone marrow in different culture conditions. Cytotechnology. 2011;63(3):217–226. doi: 10.1007/s10616-010-9329-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang N, Wu XS. Synthesis, characterization, biodegradation, and drug delivery application of biodegradable lactic/glycolic acid oligomers: part II. Biodegradation and drug delivery application. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1997;9(1):75–87. doi: 10.1163/156856297x00272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGinity JW, O’Donnell PB. Preparation of microspheres by the solvent evaporation technique. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;28(1):25–42. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadajkar AS, Bhavsar Z, Ko CY, Koppolu B, Cui W, Tang L, et al. Multifunctional particles for melanoma-targeted drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(8):2996–3004. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wadajkar AS, Kadapure T, Zhang Y, Cui W, Nguyen KT, Yang J. Dual-imaging enabled cancer-targeting nanoparticles. Adv Healthc Mater. 2012;1(4):450–456. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201100055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahimi M, Wadajkar A, Subramanian K, Yousef M, Cui W, Hsieh JT, et al. In vitro evaluation of novel polymer-coated magnetic nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery. Nanomedicine. 2010;6(5):672–680. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wadajkar A, Koppolu B, Rahimi M, Nguyen K. Cytotoxic evaluation of N-isopropylacrylamide monomers and temperature-sensitive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) nanoparticles. J Nanopart Res. 2009;11(6):1375–1382. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koppolu B, Bhavsar Z, Wadajkar AS, Nattama S, Rahimi M, Nwariaku F, et al. Temperature-sensitive polymer-coated magnetic nanoparticles as a potential drug delivery system for targeted therapy of thyroid cancer. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2012;8(6):983–990. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2012.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menon JU, Kona S, Wadajkar AS, Desai F, Vadla A, Nguyen KT. Effects of surfactants on the properties of PLGA nanoparticles. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012;100(8):1998–2005. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghaly T, Rabadi MM, Weber M, Rabadi SM, Bank M, Grom JM, et al. Hydrogel-embedded endothelial progenitor cells evade LPS and mitigate endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301(4):F802–F812. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00124.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelm JM, Fussenegger M. Scaffold-free cell delivery for use in regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(7–8):753–764. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arias JI, Aller MA, Arias J. Cancer cell: using inflammation to invade the host. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayala R, Zhang C, Yang D, Hwang Y, Aung A, Shroff SS, et al. Engineering the cell material interface for controlling stem cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation. Biomaterials. 2011;32(15):3700–3711. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mortera-Blanco T, Rende M, Macedo H, Farah S, Bismarck A, Mantalaris A, et al. Ex vivo mimicry of normal and abnormal human hematopoiesis. J Vis Exp. 2012;62:e3654. doi: 10.3791/3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vihola H, Laukkanen A, Valtola L, Tenhu H, Hirvonen J. Cytotoxicity of thermosensitive polymers poly(N-isopropylacrylamide), poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) and amphiphilically modified poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) Biomaterials. 2005;26(16):3055–3064. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canavan HE, Cheng X, Graham DJ, Ratner BD, Castner DG. Cell sheet detachment affects the extracellular matrix: a surface science study comparing thermal liftoff, enzymatic, and mechanical methods. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;75(1):1–13. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.GE Healthcare. Amersham Biosciences. Microcarrier cell culture: principles and methods. 2005:1–172. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koppolu B, Rahimi M, Nattama S, Wadajkar A, Nguyen KT. Development of multiple-layer polymeric particles for targeted and controlled drug delivery. Nanomedicine. 2010;6(2):355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar A, Kamihira M, Galaev IY, Mattiasson B, Iijima S. Type-specific separation of animal cells in aqueous two-phase systems using antibody conjugates with temperature-sensitive polymers. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;75(5):570–580. doi: 10.1002/bit.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin I, Wendt D, Heberer M. The role of bioreactors in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22(2):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang J, Peng R, Ding J. The regulation of stem cell differentiation by cell-cell contact on micropatterned material surfaces. Biomaterials. 2010;31(9):2470–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bratt-Leal AM, Carpenedo RL, Ungrin MD, Zandstra PW, McDevitt TC. Incorporation of biomaterials in multicellular aggregates modulates pluripotent stem cell differentiation. Biomaterials. 2010;32(1):48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang Z, Akiyama Y, Yamato M, Okano T. Comb-type grafted poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) gel modified surfaces for rapid detachment of cell sheet. Biomaterials. 2010;31(29):7435–7443. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.