Abstract

Impulsivity has been a widely explored construct, particularly as a personality-based risk factor for addictive behaviors. The authors review evidence that (a) there is no single impulsivity trait; rather, there are at least five different personality traits that dispose individuals to rash or impulsive action; (b) the five traits predict different behaviors longitudinally; for example, the emotion-based urgency traits predict problematic involvement in several risky behaviors and sensation seeking instead predicts the frequency of engaging in such behaviors; (c) the traits can be measured in pre-adolescent children; (d) individual differences in the traits among preadolescent children predict the subsequent onset of, and increases in, risky behaviors including alcohol use; (e) the traits may operate by biasing the learning process, such that high-risk traits make high-risk learning more likely, thus leading to maladaptive behavior; (f) the emotion-based urgency traits may contribute to compulsive engagement in addictive behaviors; and (g) there is evidence that different interventions are appropriate for the different trait structures.

Keywords: Addiction, compulsivity, impulsive behavior, personality, rash action

INTRODUCTION

Most addictive behaviors are described, in part, as impulsive. Impulsivity has been shown to play an important role in many different forms of psychopathology. Various facets of impulsivity have been linked to a myriad of DSM-IV [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition; 1] criteria for clinical diagnoses including borderline personality disorder, mania, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), binge eating disorder, pathological gambling, and substance use disorders. Not surprisingly, the DSM-IV describes the essential feature of impulse-control disorders as “the failure to resist an impulse, drive, or temptation to perform an act that is harmful to the person or to others”. Additionally, impulsivity has been incorporated into various etiological theories for a variety of risk behaviors including substance use, cigarette smoking, and eating disordered behaviors.

In this paper, we review research describing a series of advances in the study of personality contributors to impulsive behavior and their relationship to risky behavior in general and substance use in particular. There is considerable evidence that there are at least five different personality traits that contribute to impulsive behavior, and we note the importance, psychometrically, of representing each trait with its own separate score. The different traits play different roles in explaining addictive behavior, as indicated by both cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. We review recent evidence that the traits can be measured in preadolescent children, and that individual differences among children on these traits predict the subsequent onset of addictive behaviors, including alcohol use, binge eating, and smoking. We then consider another body of research that offers a risk model integrating these trait factors with psychosocial learning, to help explain the mechanism by which personality can lead to addictive behaviors. We note recent theory suggesting that certain impulsivity-related traits can lead to the development of compulsive involvement in addictive behaviors; this line of theory has not yet been tested empirically. We conclude by considering both the treatment and research implications of this body of research.

THE HETEROGENEITY OF CONSTRUCTS IN THE DOMAIN OF IMPULSIVITY

Historically, researchers such as Eysenck and Eysenck [2], Cloninger [3] and Tellegen [4] conceptualized impulsivity as a trait within their respective theories of personality. As the study of personality contributors to impulsive behavior has progressed, researchers have realized that many different traits have been included in measures of “impulsivity.” As Depue and Collins [5] noted, impulsivity has been described as a construct containing a mixed amalgamation of lower-order traits including sensation seeking, boredom susceptibility, failure to persevere on tasks, novelty-seeking, unreliability, adventuresomeness, failures of inhibitory control, and lack of planning. Indeed, measures labeled impulsivity reflect constructs as diverse as a short attention span, a tendency to participate in risky behavior, and a lack of cognitive reflection before action.

It is likely that the use of the same term, impulsivity, to refer to many different trait constructs had slowed advances in understanding risk-taking or addictive behaviors. In recent years, this problem has also been considered in the context of advances in psychometric theory that emphasize the need for a single score to reflect a single, homogeneous construct [6–9]. When a single score on a measure actually reflects more than one psychological construct, two sources of uncertainty are built into the meaning of the measure score. The first is that one cannot know the nature of the different dimensions’ contributions to that score, and hence to correlations of the measure with measures of other constructs. Consider the NEO PI-R measure of the five factor model of personality [10]. One of the five factors is neuroticism, which is understood to be composed of six, elemental constructs. Two of the six constructs are angry hostility and self-consciousness. Measures of those two traits do correlate, such that they consistently fall on a neuroticism factor in exploratory factor analyses [11]. However, they are not the same construct. Their correlation was .37 in the standardization sample; they share only 14% of their variance.

It is relatively common for one person to be high in angry hostility and low in self-consciousness, whereas another person is low in angry hostility and high in self-consciousness. The key point is that these two different personality patterns could produce exactly the same score on neuroticism as measured by the NEO PI-R, even though the two constituent traits mean different things and have different external correlates. For example, both by expert rating and measurement, psychopathy involves being unusually high in angry hostility and unusually low in self-consciousness [12]. The science of personality can benefit from the development of theories relating angry hostility to other constructs, and theories relating self-consciousness to other constructs, but the use of a single score, such as an overall neuroticism score, that combines the two constructs produces scores, and hence science, of unclear meaning.

The second source of uncertainty is perhaps more severe than the first. The same composite score is likely to reflect different combinations of constructs for different members of the sample. For some individuals, a given neuroticism score could reflect equal parts angry hostility and self-consciousness; for others, the score could reflect high self-consciousness and low angry hostility; and for others, the reverse could be true. It follows that a correlation using an overall scale score lacks precision. One just cannot know the meaning of scores on a scale that combines multiple constructs. The recognition by impulsivity researchers that scales measuring impulsivity actually reflect multiple constructs indicated that the same imprecision was present in the study of impulsivity [5, 13, 14].

ADVANCES IN UNDERSTANDING THE PERSONALITY UNDERPINNINGS OF IMPULSIVE BEHAVIOR

The recognition by impulsivity researchers of the heterogeneity of items used in measures of impulsivity, together with this recent psychometric emphasis on homogeneity of measurement, has led to a body of research conducted in the last 10 years that has helped clarify the personality underpinnings of impulsive behavior. Whiteside and Lynam [14] provided an important contribution toward the investigation of the specific traits underlying impulsive behavior. They factor analyzed a large set of existing personality measures of impulsivity to determine whether a reliable structure of traits underlies impulsive behavior. The personality measures they examined included the: NEO PI-R [10], Sensation Seeking Scale [SSS; 15], Temperament and Character Inventory [TCI; 3], Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire, Control Style [MPQ; 4], Personality Research Form Impulsivity Scale [PRF; 16], 1–7 Impulsiveness Questionnaire [2], the EASI-III Impulsivity Scale [17], Functional and Dysfunctional Impulsivity Scales [18], and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 [BIS-11; 19]. That set of scales provided a reasonable representation of all of the existing personality dimensions thought to be related to impulsive behavior. Whiteside and Lynam’s [14] factor analysis was designed to identify the set of underlying personality dimensions represented by these many measures.

They identified four separate personality traits related to impulsive behavior. Interestingly, the four resulting dimensions could be understood in the context of the comprehensive five factor model of personality. The first dimension was labeled Urgency, which is the tendency to experience strong impulses usually within the context of negative affect [14]. This trait is associated with the Impulsiveness facet of the Neuroticism scale of the NEO PI-R. Those high in the personality trait of negative urgency are likely to engage in rash, impulsive behaviors when experiencing intense negative affect.

Lack of premeditation was the second dimension identified, and is the lack of a tendency to consider the consequences of an act prior to engaging in the behavior [14]. This trait is associated with low scores on the deliberation facet of the conscientiousness dimension of personality, and captures the tendency to act without planning. Not surprisingly, this trait was the most highly represented among the measures of impulsivity analyzed by Whiteside and Lynam.

The third dimension, Lack of perseverance, is a personality trait related to the self-discipline facet of the conscientiousness dimension of personality. This trait is characterized by a lack of ability to remain focused on a task that may be perceived as boring or difficult.

The fourth dimension, sensation seeking, has been described as both a tendency to enjoy the pursuit of exciting activities and openness to trying new experiences (that may or may not pose a risk). This trait is associated with the excitement seeking facet of the extraversion dimension of personality. Table 1 provides a summary indicating, for each scale studied by Whiteside and Lynam [14], its place on these four dimensions.

Table 1.

Significant Impulsive Behavior Trait Factor Loadings on Various Impulsivity Scales. Whiteside & Lynam, 2001. Significant Factor Loadings (>.50) are indIcated by an X

| Impulsivity Scale | Lack of Premeditation | Urgency | Sensation Seeking | Lack of Perseverance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEO-PI-R Deliberation | X | |||

| MPQ Control | X | |||

| PRF-E Impulsivity | X | |||

| Dysfunctional Impulsivity | X | |||

| I-7 Impulsivity | X | |||

| TCI Impulsivity | X | |||

| EASI-III Decision Time | X | |||

| BIS Nonplanning | X | |||

| BIS Motor Impulsivity | X | X | ||

| NEO-PI-R Impulsiveness | X | |||

| EASI-III Inhibitory Control | X | |||

| Additional items | X | |||

| BIS Attentional Impulsivity | X | |||

| NEO-PI-R Excitement Seeking | X | |||

| I-7 Venturesomeness | X | |||

| EASI-III Sensation Seeking | X | |||

| Functional Impulsivity | X | |||

| NEO-PI-R Self-discipline | X | |||

| SSS Disinhibition | X | X | ||

| EASI-III Persistence | X | |||

| SSS Boredom Susceptibility | X |

It is important to recognize that these four traits are only modestly correlated with each other. Whiteside and Lynam [14] created a scale to represent each of the four traits, and their inter-correlations ranged from -.14 to .45, with a median of .23 (5% shared variance). This finding has been replicated: Cyders and Smith [20] found a median correlation of .25 using questionnaire assessment and .20 using interview assessment. These four constructs are related, but not very highly. It follows that their roles in impulsive behavior should be studied separately, rather than combining the scales to produce a single score.

It is also clear that the four scales are substantively quite different. Urgency refers to a tendency to act rashly or impulsively when emotional; its highest loading is on neuroticism. It can be thought of as an affect-based trait that disposes individuals to impulsive action. In contrast, sensation seeking is not primarily based on affective experience. It is part of the extraversion domain of personality, and involves a basic need to seek stimulation and thrill. The other two traits, lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance, both reflect aspects of low conscientiousness. They do not reflect affect-based impulsive action, nor do they reflect a need to seek stimulation; rather, they reflect two different ways in which a lack of conscientiousness can result in impulsive action. One is a simple failure to plan: when one acts without forethought, one’s actions can prove ill-advised or rash. The other is quite different: a failure to maintain a focus on a task, in the face of distractions, can also result in ill-advised action, but in a different way. Thus, the trait measures do not just differ psychometrically; they reflect substantively different personality processes. We described the Whiteside and Lynam [14] contribution as important, because it clarified the underlying dimensions reflected in past impulsivity research and, most importantly, clarified the need to study each trait construct separately from the others.

THE FACTOR STRUCTURE OF PERSONALITY TRAITS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO IMPULSIVE BEHAVIOR

Smith et al. [21] followed this logic and conducted formal tests of the structure of the four traits. They compared several possible structural models of the traits, using confirmatory factor analysis. First, they found that a single factor model, reflecting the hypothesis that all the traits are expressions of a single impulsivity dimension, fit the data quite poorly (whereas fit values of .90 or higher reflect good fit, the one-factor model fit values were .58 and .49). Next, they tested a four factor model, reflecting the four traits identified by Whiteside and Lynam [14]. That model fit the data well (fit index values of .99 and .98). They then tested a hierarchical model, in which the four factors were included, but also defined as expressions of a single, higher-order impulsivity dimension. That model did not work well: the higher order impulsivity dimension explained less than 1% of the variance in urgency and only 6% of the variance in sensation seeking: there was not an overall impulsivity dimension underlying the four traits. The best-fitting model represented lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance as two separate facets of an overall low conscientiousness dimension, with both urgency and sensation seeking modeled as separate factors. That model preserved the four factors, but included the finding that two of the four factors involved low conscientiousness. In addition to these structural analyses, Smith et al. [21] found good convergent validity in trait assessment across method of assessment and good discriminant validity between traits within method of assessment, using a multitrait, multimethod design.

The next important step in identifying the personality dimensions underlying impulsive behavior involved the recognition that individuals act in rash, impulsive ways when experiencing intensely positive affective states [22]. Although mild increases in positive affect can improve cognitive flexibility [23], verbal fluency [24], and problem solving [25], it is also true that increased positive affect interferes with one’s orientation toward the pursuit of one’s long-term goals, increases one’s distractibility, and makes one more optimistic about the positive outcomes of a situation [26, 27]. Pronounced emotional arousal, whether positive or negative, can lead to less discriminative use of information [28] and poorer decision making [29]. One result of strong positive mood is reduced rational evaluation of the consequences of potential actions and increases in risk-taking behavior, including drug use, sexual encounters, and gambling [30, 31, 32, 33, 34].

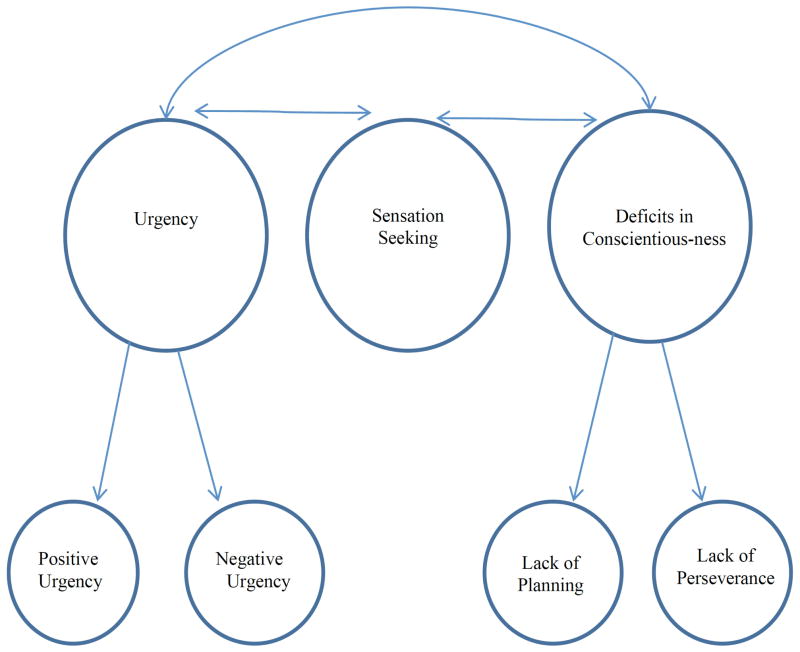

Based on these considerations, Cyders et al. [22] developed a measure of positive urgency, referring to the tendency to act rashly when experiencing intensely positive mood states. To contrast it with the original urgency, they relabeled the original urgency as negative urgency, because of its focus on negative mood states. Cyders and Smith [20] then tested structural models of the five traits. The best fitting model was hierarchical: at the lower level, it included each of the five separate traits. At the higher level, positive and negative urgency were facets of an overall urgency dimension, reflecting emotion-based dispositions toward impulsive action; lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance were again facets of low conscientiousness, and sensation seeking was the fifth factor. Cyders and Smith [20] replicated this structure, and found good convergent and discriminant validity evidence, across questionnaire and interview assessment methods. Fig. (1) depicts this model.

Fig. 1.

The relations between the five constructs of impulsive behavior. A depiction of the relationships between positive urgency, negative urgency, sensation seeking, lack of planning and perseverance.

In factor analyses relating the five traits to the dimensions of general personality as measured by the NEO PI-R, the two urgency traits loaded positively on neuroticism, negatively on agreeableness, and negatively on conscientiousness [35]. Sensation seeking loaded primarily on extraversion and the other two traits had primary, negative loadings on conscientiousness.

THEORY AND RESEARCH CONCERNING THE DIFFERENT ROLES OF DIFFERENT IMPULSIVITY-RELATED TRAITS

A Theoretical Perspective on the Different Functions of the Different Traits

Positive and negative urgency are understood to be emotion-based dispositions to engage in rash action. As we referred to briefly above, intense emotions, whether positive or negative, can undermine rational, advantageous decision making [36, 37, 38, 39, 40] and impair one’s ability to maintain self-control [41, 42, 42]. It is therefore not surprising that, when individuals are experiencing intense emotions, they sometimes engage in actions that are ill-considered and maladaptive, in that they work against one’s long-term interests. For example, heavy alcohol use may be used to manage emotion. Daily diary studies of alcohol use indicate that individuals drink more on days when they experience anxiety and stress [44]. Negative emotional states correlate with a greater frequency of many maladaptive, addictive behaviors, including alcohol and drug abuse [45, 46, 47, 48, 49]. This pattern may also be true of bulimic behaviors; individuals tend to participate in more binge eating and purging behaviors on days during which they experienced negative emotions [50, 51]. Negative emotions are often cited as triggers for binge and purge episodes [52]. For bulimic women, engaging in binge eating produces a decline in the earlier negative emotion [51; but see 53].

Because decision-making is impaired, there is an increased likelihood of maladaptive involvement in such behaviors. Highly emotional individuals, for example, whether unusually distressed or happy, are less likely to modulate their alcohol consumption. For this reason, positive and negative urgency are theorized to relate to problem levels of involvement in a variety of risky behaviors including drinking, drug use, gambling, risky sexual behavior, and others [35, 54].

In contrast, sensation seeking is not an affect-based personality trait. Individuals high in sensation seeking are more likely to try new things and to experiment with a variety of behaviors [15]. It follows that sensation seeking should be particularly associated with the frequency of behaviors such as drinking, sexual activity, and gambling. But since, for high sensation seekers, these behaviors are not primarily engaged in while experiencing unusually intense emotions, judgment is likely to be preserved and sensation seeking should be less predictive of excessive, problem levels of involvement in any one of these behaviors in particular.

Lack of premeditation is understood to refer to a deficit in employing cognitive mediation before action. Although it is certainly true that a tendency to act without forethought can lead to maladaptive drug use or other risky behaviors, this trait does not operate primarily under heavy emotion, and so tends not to involve disrupted reasoning or decision making to the same degree. Similarly, lack of perseverance refers to the inability to remain focused on a task. This trait, too, is not an emotion-based one and so is thought to be most relevant to impaired school or occupational functioning. We next consider both cross-sectional and longitudinal research indicating the different roles of the different traits.

Cross-Sectional Research

To understand the different roles of the five different traits, it is important to study them together, so that the association of any one trait with impulsive behavior is net the influence of the other traits. In cross-sectional studies using that analytic approach, negative urgency has been found to relate to problem gambling [55, 21, 56]; problem drinking and alcohol dependence [57, 22, 55, 58, 59, 60, 21]; illegal drug use [60]; binge eating [61, 22, 58, 62, 55, 63, 21]; risky sex [60]; aggression, including intimate partner violence [64, 60]; compulsive buying behavior [65]; mobile phone dependency (such as excessive reliance on talking with friends by phone when distressed) [66]; cigarette craving [67]; and excessive reassurance seeking [57]. In addition, negative urgency correlates with a general measure of rash behavior undertaken while in an unusually negative mood [68]. Because negative urgency is viewed as the tendency to act rashly when distressed, this set of correlates, though referring to diverse behaviors, is consistent with urgency theory [69].

The recognition of the trait of positive urgency is more recent [22], but a number of cross-sectional correlates of this trait have emerged as well. Positive urgency is associated with pathological gambling [70, 22]; drinking quantity and problem drinking [71, 72]; illegal drug use [73]; risky sexual behavior [73]; smoking [74]; and general rash acts undertaken while in a positive mood [75]. In a laboratory study in which positive mood state was manipulated, positive urgency predicted observed drinking quantity and gambling behavior while in a positive mood [76]. Interestingly, positive urgency is unrelated to eating disorder diagnosis [22].

Positive and negative urgency are substantially correlated, with bivariate correlation estimates ranging from .39 to .71 across studies. There is some evidence that the traits have different correlates: Cyders and Smith [75] found that negative urgency was uniquely associated with rash acts undertaken while in a negative mood, and positive urgency was uniquely associated with rash acts undertaken while in a positive mood. In addition, and consistent with theory, negative urgency differentiates eating disordered women from others but positive urgency does not [22].

Sensation seeking, when considered together with the other four traits, is consistently associated with the frequency of alcohol use, but not with problem drinking [57, 22, 55, 77, 21], and with the frequency of gambling, but not problem gambling [70, 55, 21]. The trait is also associated with risky behavior involvement, such as mountain climbing and bungee jumping [70, 78].

Lack of planning has been associated with school difficulties [21], engaging in risky behaviors likely to have a negative outcome [78], delinquency [60], risky sex [73], and, although less frequently, has sometimes been related to illegal drug use and problem drinking [60, 73]. Lack of perseverance on tasks relates to school difficulties [21] and sometimes to illegal drug use [73].

Empirically, prediction from the individual traits is superior to prediction from aggregate traits in this domain. For example, Stice (2002) found that a global measure of “impulsivity” had an effect size of r = .07 in predicting eating pathology. Fischer, Smith and Cyders (2008) examined prediction of eating pathology using four of the individual five traits (all but positive urgency). They found a much larger effect size for negative urgency (r = .38) than for any of the other traits (sensation seeking: r = .16; lack of planning: r = .16; lack of perseverance: r = .08). Similar findings have been observed for other addictive behaviors.

Longitudinal Research

We next consider prospective research designs; in each case, the influence of a trait is net the influence of the other four traits. In a sample of first year college students in the U.S., positive urgency, but not negative urgency, predicted increased gambling behavior from the beginning to the end of the school year [70]. Positive urgency predicted increased drinking problems across the first year of college [71], and both positive and negative urgency predicted increased quantity of alcohol typically consumed across that period [71, 72]; however, the two traits did not predict increased drinking frequency. Positive urgency predicted increased use of illegal drugs and increases in risky sexual behavior during the first year of college [23]. In addition, as noted above, positive urgency predicted increases in positive-mood based risky behavior and negative urgency predicted increases in negative-mood based risky behavior across the same longitudinal period [75]. Negative urgency, in interaction with sexual assault exposure, predicted increases in eating disorder symptoms during college [79], and increases in negative urgency across a 3–4 week period were associated with increases in drinking to cope, bulimic symptomatology, and excessive reassurance seeking [57].

Sensation seeking predicted increased risky behavior involvement (mountain climbing, bungee jumping, skateboarding, scuba diving, parasailing, and parachuting) across the first year of college [70]. It also predicted increases in risky sexual behavior in college [73] and increases in drinking frequency, but not drinking quantity or alcohol-related problems, during college [71]. Lack of planning did not predict changes in any drug use or other risky behaviors across the first year of college, again when the other traits were included in the models. However, lack of perseverance did uniquely predict increases in risky sexual behavior [73].

So far in this paper, we have shown that the traits predict changes in risky behaviors, including alcohol and drug use, in ways consistent with theory. An important empirical question is whether these traits predict the early onset of addictive behaviors. This question is important for two reasons. The first concerns theory: which of these five traits, if any, contribute to the initial onset of alcohol use, drug use, and other risky behaviors? Or, are the traits relevant only for the maintenance of risky behaviors over time? The second concerns clinical application: early onset of addictive behaviors has been shown to be an important predictor of dysfunction across the lifespan, and is predictive of longer time periods of exposure to risk [80], increased risk for the development of substance use problems over time [81, 82], increased risk for STD’s associated with alcohol use [83], and physical growth impairments among girls who engage in early smoking behaviors [84]. Accordingly, we next consider whether individuals differ on these traits in childhood, prior to the onset of risk behavior.

THE FIVE TRAITS MEASURED IN CHILDHOOD PREDICT THE SUBSEQUENT ONSET OF ADDICTIVE BEHAVIORS

In recent years, there has been increasing evidence that individual differences in personality, including the five personality domains from the comprehensive, five factor model of personality, are present and can be assessed in children [85, 86, 87, 88, 89]. The assessment of the five personality dispositions to rash action described in this paper requires an even more precise assessment of personality in children, because it involves assessment at the lower, facet level of the hierarchy of personality.

Zapolski and Smith [90] and Zapolski, Stairs, Settles, Combs, and Smith [91, 92] reported on the development of questionnaire and interview scales for the five traits. They found that each trait could be assessed with internal consistency reliability, there was good convergent validity of assessment across method, good discriminant validity between the traits within assessment method, and that the traits concurrently predicted different behaviors in theoretically consistent ways. For example, both positive and negative urgency predicted aggressive behavior; lack of perseverance predicted attentional problems; sensation seeking predicted risky behavior involvement; negative urgency predicted risky behavior involvement while in a negative mood; and positive urgency predicted risky behavior involvement while in a positive mood. Gunn and Smith [93] found that the five trait structure was confirmed in a sample of 1,843 5th grade children (ages 10 and 11). Positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking related to 5th grade drinker status, and negative urgency related to 5th grade binge eater and purger status [94, 93, 95]. A combination of positive and negative urgency related to 5th grade smoker status as well [96]. Thus, there is clear evidence that the five trait structure exists in pre-adolescent children, that the traits can be measured reliably and using multiple methods, and that the traits play concurrent predictive roles consistent with what has been observed in adults.

Most recently, longitudinal research has shown that positive urgency measured in 5th grade predicts the subsequent onset of, and subsequent increases in, drinking behavior across the transition into middle school [97]. Negative urgency, again measured in 5th grade, predicts the subsequent onset of, and subsequent increases in, binge eating behavior during the same transition into middle school [98]. Smith and Zapolski [99] found that a combination of lack of planning and lack of perseverance predicted smoking onset in boys across the middle school transition, and that those traits together with positive and negative urgency predicted smoking onset in girls across the same transition. These prospective studies provide the first evidence that the urgency traits are important for the earliest involvement in the addictive behaviors of alcohol consumption and binge eating behavior. We next turn to consideration of how this effect operates; that is, the mechanism by which a personality trait can increase the likelihood of drug use or other risky behavior involvement.

ACQUIRED PREPAREDNESS: A MECHANISM BY WHICH PERSONALITY LEADS TO ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR

It is of course the case that no personality trait automatically commandeers behavior and produces alcohol consumption, drug use, or any addictive behavior. It is thus essential to identify and assess a mechanism by which traits such as positive and negative urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance and sensation seeking influence the early onset of addictive behaviors. One possible mechanism is described by Acquired Preparedness (AP) theory. This theory is an extension of person-environment transaction theory [100, 101]; this latter theory refers to processes in which personality interacts with environmental events to influence subsequent behavior. One type of transaction is known as a selective person-environment transaction: to some degree, individuals select environments as a function of their personalities. Thus, variation in exposure to high-risk environments occurs partly as a function of disposition-based selection of such environments. A second type of transaction is known as a reactive person-environment transaction: as a function of individual differences in personality, people react differently to the same environmental event [100]. Thus, two individuals may not experience an objectively common event in the same way.

The AP extension of this theory holds that when two different individuals experience the same event differently from each other, they can learn different things from that event [102]. The label “acquired preparedness” refers to the idea that individuals are differentially prepared to acquire certain learning experiences as a function of their personalities [102]. In a longitudinal, laboratory study, Smith, Williams, Cyders, and Kelley [103] demonstrated this process. Individuals exposed to precisely the same learning, who experienced precisely the same outcomes from a common behavioral trial, nevertheless formed different expectancies from the experience; their different expectancies could be predicted by prior differences in their personalities [103].

There have now been a number of longitudinal studies testing the AP model. Among college students, Settles, Cyders, and Smith [72] found that positive urgency at the start of college predicted increased endorsement of expectancies for reinforcement from drinking, measured partway through the first year of college, which in turn predicted increases in the quantity of alcohol typically consumed by the end of that year. The relationship between initial positive urgency and quantity consumed at the end of year appears to have been mediated by positive alcohol expectancies. In the same study, the apparent influence of negative urgency at the start of college on typical drinking quantity at the end of the first year was mediated by the motive to drink to cope with distress. These findings are consistent with the AP model: traits predicted changes in learning, which in turn predicted increases in addictive behavior.

Using a different personality representation of disinhibition and testing the AP process over a much longer time interval, Corbin, Iwamoto, and Fromme [104] found that positive, but not negative, expectancies about alcohol partially mediated the influence of sensation seeking and lack of premeditation, (measured during the summer before college entry), on alcohol use and related problems four years later, (i.e., during the fourth year of college).

Support for the AP model has also accrued from studies of early adolescence. Combs, Smith, Flory, Simmons, and Hill [105] found that the apparent influence of the trait of ineffectiveness, measured during the first year of middle school, on eating disordered behavior two years later appears to have been mediated by learned expectancies that thinness leads to overgeneralized life improvement. Pearson et al. [98] found that the predictive relationship between negative urgency, measured in 5th grade, and binge eating behavior one year later appears to have been mediated by learned expectancies that eating helps alleviate negative affect. With respect to drinking behavior, Settles and Smith [97] showed that the relationship between 5th grade positive urgency and 6th grade drinker status appeared to have been mediated by expectancies that alcohol facilitates positive social experiences. The latter two studies may prove informative for efforts to understand the developmental processes underlying addictive behavior involvement. It may be that high-risk personality traits present before adolescence shape the psychosocial learning process in a way that heightens risk for early involvement in addictive behaviors. As is well known, early involvement in these risky behaviors is associated with ongoing difficulties and subsequent dysfunction.

URGENCY, IMPULSIVITY, AND COMPULSIVITY: TOWARD A FULLER UNDERSTANDING OF ADDICTIVE PROCESSES

A new line of theoretical development regarding the urgency traits and addiction concerns the relationship between impulsivity and compulsivity [106]. This relationship is important, because drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and other addictive behaviors are described as both impulsive and compulsive in nature. Typically, initial engagement in many behaviors that can become addictive is described as impulsive. Early binge eating episodes, consumption of a large amount of alcohol, decisions to have sex with someone one has just met, decisions to ingest illegal drugs, or betting far more money than intended are all thought to involve acting on an impulse or acting rashly. We understand decisions such as these to be characterized by a focus on meeting one’s immediate need, or acting on an immediate urge, without sufficient consideration of the possible negative consequences of the act with respect to one’s long-term interests, goals, or health.

Interestingly, when engagement in such behaviors progresses to the point at which a disorder is present, those similar yet more impairing and/or distressing behaviors are characterized as compulsive rather than impulsive. The point at which an individual continues to engage in the same immediate rash action with the awareness that the behavior will be followed by a prolonged cycle of harm is the distinguishing factor between continued engagement in addictive behavior and compulsion. In fact, a key definitional feature of addiction is that one continues to engage in the addictive behavior, despite knowing that doing so will have negative consequences: a person with an addictive disorder is compelled to engage in the behavior [107]. For example, one DSM IV diagnostic criterion for substance dependence is that “the substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance …” [1].

Pearson et al. [106] note that past models, in which impulsivity and compulsivity are considered as existing on opposite poles of a continuum [107], do not appear to be accurate, because (a) many disorders have features of both impulsivity and compulsivity, and (b) empirical data indicate the two are positively related [e.g. 108]. To explain their positive relationship, Pearson et al. [106] make the following argument.

Negative urgency-based impulsive acts, such as alcohol consumption and drug use, provide the negative reinforcement of relief from, or distraction from, the precipitating distress. Through repeated reinforcement, the urgent action becomes consistently chosen. Because negative urgency-based actions are undertaken without due consideration of one’s ongoing interests, they often work against those interests. Thus, over time, individuals more and more frequently engage in actions (such as alcohol consumption) that undermine their pursuit of important, long term goals.

An increasing preference for urgent actions such as alcohol and drug use likely occurs for several reasons. First, alcohol and drug use operate in a general way, in that the immediate reinforcement and distraction from distress they provide can follow a wide range of events that are distressing. Their reinforcement action is not specific to a single source of negative affect. For that reason, their reinforcing effects can be experienced frequently and following a variety of precipitants. Thus, the immediately reinforcing rash behavior comes to be consistently chosen when one is distressed. Second, on each occasion in which one chooses the rash, immediate, reinforcing act, one has missed an opportunity to take a different approach to managing one’s distress. One has missed a chance to engage in responses that focus on solving the problem that led to the initial distress [54, 106]. By repeatedly missing such chances, one tends not to develop problem-solving coping responses to distress. Over time, one has less and less access to responses other than the rash, immediate response of choice. Thus, over time, one is increasingly left with that one response to one’s distress, and the response becomes compelled. Ultimately, when one is distressed, one has only “one tool in the toolbox,” which is the rash action that provides immediate, but short-term relief. Adding to this process is the reality that many rash actions, such as alcohol or drug use, themselves create problematic situations for individuals and often lead to heightened negative affect. As a result, the need for distress relief becomes more and more frequent, thus accelerating the rate at which the rash action becomes the preferred behavioral choice. Eventually, the choice of that response can be described as compulsive, because one engages in it, knowing that the response will bring continued harm in the long run.

This model thus describes the relationship between negative urgency-based impulsivity and compulsivity in terms of the development of a behavioral pattern over time. In contrast to earlier theories that have focused on classifying specific disorders as impulsive or compulsive, Pearson et al. [106] have developed a model that explains the progression of how a behavior begins as impulsive and becomes compulsive over time. We believe this process applies to a wide range of rash behaviors, including both drug and alcohol abuse.

One very important implication of this identification of multiple different personality traits that play a role in impulsive action is that individuals with different personality structures are likely to need different treatment interventions. We next consider that issue.

IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

Zapolski, Settles, Cyders, and Smith [109] reviewed literature concerning effective interventions as a function of personality structure and made a series of recommendations for how clinicians can construct interventions that are appropriate to a client’s personality structure.

Negative Urgency

They argued that negative urgency, the tendency to act rashly when distressed, is likely to benefit from treatments that have proven effective for the symptoms of borderline personality disorder [110]. In particular, individuals high in negative urgency are likely to benefit from developing skills to tolerate distress and regulate their emotions. These skills include learning to adjust emotional reactions by considering the context, learning to experience emotions without acting, learning to adjust reactions through relaxation, prayer, and other soothing activities. Other relevant distress-tolerance skills include learning to identify precipitating events or triggers to emotional reactivity and learning adaptive alternative behaviors in response to those triggers, and learning to evaluate behavioral choices in terms of one’s long-term goals. These types of interventions have proven effective for drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and eating disorders [111, 112, 113].

Positive Urgency

Less is known about possibly effective interventions for positive urgency-based risk, largely because until recently clinical researchers had not fully appreciated the degree to which risky, regrettable behaviors are undertaken in celebratory contexts (such as excessive alcohol consumption or ill-considered sexual activity in contexts such as happy hour, parties after work, celebrations of work successes, and the like). Possible intervention strategies include (a) creative efforts to help individuals appreciate that maintenance of their positive mood might be facilitated by careful consideration of the consequences of prospective actions; (b) teaching clients how to savor one’s success in an integrative cognitive-affective way, by replaying or reviewing the success with colleagues or friends; (c) working with clients to identify alternative, safer behaviors that can enhance one’s existing positive mood; and (d) helping clients identify warning signs that they are at risk to behave impulsively, and develop reminder cues to help them remain cognizant of their long-term interests and goals. The use of reminder cues has been found to be effective for challenges as diverse as condom use and dieting [114, 115].

Sensation Seeking

One important success in efforts to develop targeted prevention programs has been the development of intervention programs for adolescents high in sensation seeking. Prior research has shown that adolescents high on sensation seeking are more likely to engage in a wide variety of potentially reckless behaviors, such using alcohol, having sex while using alcohol, and using marijuana and other drugs [116, 117]. For this group of adolescents, researchers developed media prevention messages that were distinct in that they elicited very high levels of sensory arousal; in the context of a high sensation value message, adolescents were provided a guide to thrill-seeking adventures in the local area [117]. These high sensation value messages have proven effective in reducing substance use among sensation seeking adolescents; interestingly, the positive effects of the intervention were largely specific to that group [118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124]. Clinicians have drawn on these successes in their individual work with clients high in sensation seeking to develop safer, alternative means of seeking stimulation.

Lack of Premeditation and Lack of Perseverance

For individuals who tend to act without forethought, problem solving interventions that teach individuals to engage in cognitive enterprises before acting may reduce some rash acts; that is, teaching individuals cognitive mediation, so they can anticipate both the positive and negative consequences of possible actions, appears effective [125]. For non-persistent, highly distractible individuals, it may be the case that stimulant medications may help them maintain focus on the task at hand [126]. In fact, studies with children suffering from attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) indicate that both stimulant medications and rigorous behavior therapy appear to be equally effective for that group [127].

The recent advances in understanding the personality underpinnings of impulsive behavior provide clinicians with an important new tool. They can assess the trait structure of clients engaging in alcohol or drug abuse, or other addictive behaviors, and tailor their interventions to a client’s particular risk profile.

At present, the most frequently used treatment for addictions is twelve-step facilitation therapy [128]. There is little research on the degree to which individual differences in the five different impulsivity-related traits moderate the effectiveness of this treatment approach. Blonigen and colleagues [129] investigated the association among participation in a twelve-step facilitation program and “impulsivity” (this construct was measured by the Differential Personality Inventory and appears largely to reflect lack of planning) over the course of 16 years. Results indicated that at 1 and 16 year follow-up points, participants who attended AA longer had significantly greater declines in the personality trait. However, this study did not include a control group of non-treated individuals, so conclusions relating the treatment to changes in lack of planning should be tempered. In an investigation designed to test potential moderators of motivational enhancement therapy, results indicated that low scores in lack of planning and/or novelty seeking were associated with greater increases in the target behavior of taking steps to reduce alcohol consumption [130]. In addition to testing specific interventions for individuals high on each of the five impulsivity-related traits, future research should investigate whether existing treatments vary in their effectiveness as a function of the traits of positive and negative urgency, sensation seeking, lack of planning, and lack of perseverance.

THE USE OF THE UPPS-P

Although it is certainly true that further advances can be made in the valid assessment of each of the five traits reviewed in this article, the UPPS-P is a measure that is available in both questionnaire and interview format that has proven reasonably reliable and valid [131]; it can be obtained by contacting either D. Lynam or G. Smith. In light of evidence that there is no single personality trait of impulsivity, but rather a set of only moderately related traits that can dispose individuals to rash, impulsive action, it is important for researchers to use measurement tools that provide separate scores for each of the traits. Clinicians can benefit from using the UPPS-P to help them understand the specific personality precursors to their client’s problem behaviors and then fashion appropriate interventions.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

There have been important recent advances in understanding the personality underpinnings of impulsive behavior. These findings are particularly important for the study of alcohol and drug abuse, because so much initial, heavy use is thought to have an impulsive quality. In this paper, we reviewed evidence that (a) there is no single impulsivity trait; (b) there are at least five different personality traits that dispose individuals to rash or impulsive action; (c) the five traits predict different behaviors longitudinally; for example, the urgency traits predict problematic involvement in several risky behaviors and sensation seeking instead predicts the frequency of engaging in such behaviors; (d) the traits can be measured in pre-adolescent children; (e) individual differences in the traits among preadolescent children predict the subsequent onset of, and increases in, risky behaviors including alcohol use; (f) the traits may operate by biasing the learning process, such that high-risk traits make high-risk learning more likely, thus leading to maladaptive behavior; (g) new theory suggests that the urgency traits may contribute to compulsive engagement in addictive behaviors; and (h) there is evidence that different interventions are appropriate for the different trait structures.

The research we have reviewed here points to several new possible lines of inquiry. First, what additional personality traits are relevant to rash, impulsive behavior? Second, there is a need for further developed theory concerning how personality measures relate to laboratory tasks thought to assess impulsive behavior. Dick, Smith, Olausson, Mitchell, Leeman, O’Malley, & Sher [132] provided a qualitative review of similarities and differences between personality and laboratory tasks, and Cyders and Coskunpinar [133] conducted a meta analysis relating the two. Different personality traits appear to relate to different laboratory tasks; for example, negative urgency, lack of planning, and lack of perseverance correlated with tasks thought to reflect prepotent response inhibition, whereas sensation seeking related to tasks thought to reflect delay response. However, in each case, the effect sizes were small. Validation research, considering issues such as construct representation (the degree to which variation on a task reflects variation on the underlying construct) [134, 8] and construct validity of self-report measures [135, 136, 8], can play a useful role in this line of investigation. There is also a need for systematic investigation of the possible differential effectiveness of different treatments for substance use as a function of variation in personality: do the interventions reviewed above function in meaningfully, reliably different ways for different clients? In addition, research to test the hypothesis that the urgency traits facilitate the development of compulsive use of substances has not yet been done and is clearly necessary. We hope the research reviewed in this paper facilitates advances in the study of impulsive behavior and other areas of inquiry in the coming years.

Although the focus of this article has been on addictive behaviors, we have reviewed evidence tying negative urgency in particular to delinquency, aggression, and intimate partner violence. It thus appears that at least these forms of aggressive crime are related to the tendency to act rashly when distressed, but not to other impulsivity-related traits. Further application of the impulsivity decomposition that we have described to the areas of aggression and criminology may help clarify the personality underpinnings of those forms of externalizing dysfunction, and thus lead to more effective treatments.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this paper was supported, in part, by NIAAA grant RO1 AA 106166 to Gregory T. Smith.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eysenck SBG, Pearson PR, Easting G, Allsopp JF. Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness, and empathy in adults. Pers Individ Dif. 1985;6:613–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM. The Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire: US normative data. Psychol Rep. 1991;69:1047–57. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tellegen A. Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire manual. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Depue RA, Collins PF. On the psychobiological complexity and stability of traits. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22:541–55. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGrath RE. Conceptual complexity and construct validity. J Personal Assess. 2005;85:112–24. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8502_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith GT. On construct validity: Issues of method and measurement. Psychol Assess. 2005;17:396–408. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss ME, Smith GT. Construct validity: Advances in theory and methodology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:89–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Zapolski TCB. On the value of homogeneous constructs for construct validation, theory testing, and the description of psychopathology. Psychol Assess. 2009;21:272–84. doi: 10.1037/a0016699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO personality inventory manual. Odessa: Psychol Assess Res; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCrae R, Zonderman A, Costa P, Bond M, Paunonen S. Evaluating replicability of factors in the revised NEO Personality Inventory: confirmatory factor analysis versus Procrustes rotation. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1996;70:552–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynam DR, Widiger TA. Using a general model of personality to understand sex differences in the personality disorders. J Pers Disord. 2007;21:583–602. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evenden J. Impulsivity: a discussion of clinical and experimental findings. J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13:180–92. doi: 10.1177/026988119901300211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30:669–98. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson DN. Personality research from manual. Goshen: Research Psychologists Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buss AH, Plomin R. A temperament theory of personality development. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickman SJ. Functional and dysfunctional impulsivity: Personality and cognitive correlates. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58:95–102. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency and their relations with other impulsivity-like constructs. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43:839–850. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14(2):155–70. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:107–18. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isen AM, Niedenthal P, Cantor N. An influence of positive affect on social categorization. Motiv Emot. 1992;16:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips LH, MacLean RDJ, Allen R. Age and the understanding of emotions: Neuropsychological and sociocognitive perspectives. J Gerontol B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57B:526–0. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.p526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene TR, Noice H. Influence of positive affect upon creative thinking and problem solving in children. Psychol Rep. 1988;63(3):895–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dreisbach G, Goschke T. How positive affect modulated cognitive control: Reduced perseveration at the cost of increased distractibility. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2004;30:343–3. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nygren TE, Isen AM, Taylor PJ, Dulin J. The influence of positive affect on the decision rule in risk situations: Focus on outcome (and especially avoidance of loss) rather than probability. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1996;66:59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forgas JP. Mood and the perception of unusual people: Affective asymmetry in memory and social judgments. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1992;22:531–47. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Anal. 2004;24:311–22. doi: 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Clarifying the role of personality dispositions in risk for increased gambling behavior. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;45:503–8. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holub SC, Musher-Eizenman DR, Persson AV, Edwards-Leeper LA, Goldstein SE, Miller AB. Do preschool children understand what it means to “diet” and do they do it? Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(1):91–3. doi: 10.1002/eat.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahn BE, Isen AM. The influence of positive affect on variety seeking among safe, enjoyable products. J Consum Res. 1993;20:257–70. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuen KSL, Lee TMC. Could moot state affect risk-taking decisions? J Affect Disord. 75:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zapolski TBC, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Positive urgency predicts illegal drug use and risky sexual behavior. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:348–4. doi: 10.1037/a0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:807–28. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: A neurocognitive perspective. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1458–3. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bechara A. The role of emotion in decision-making: Evidence from neurological patients with orbitofrontal damage. Brain Cogn. 2004;55(1):30–0. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dolan RJ. Keynote address: Revaluating the orbital prefrontal cortex. Malden: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dreisbach G. How positive affect modulates cognitive control: The costs and benefits of reduced maintenance capability. Brain Cogn. 2006;60(1):11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiv B, Loewenstein G, Bechara A. The dark side of emotion in decision-making: When individuals with decreased emotional reactions make more advantageous decisions. Cognitive Brain Research. 2005;23:85–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muraven MR, Baumeister RF. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol Bull. 2000;126:247–59. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tice DM, Bratslavsky E. Giving in to feel good: The place of emotion regulation in the context of general self-control. Psychol Inq. 2000;11:149–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tice DM, Bratslavsky E, Baumeister RF. Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80:53–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swendson JD, Tennen H, Carney MA, Affleck G, Willard A, Hromi A. Mood and alcohol consumption: An experience sampling test of the self-medication hypothesis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:198–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colder CR, Chassin L. Affectivity and impulsivity: Temperamental risk for adolescent alcohol involvement. Psychol Addict Behav. 1997;11:83–97. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:117–28. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. J Pers. 2000;68:1059–88. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin ED, Sher KJ. Family history of alcoholism, alcohol use disorders and the five-factor model of personality. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:81–0. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peveler R, Fairburn C. Eating disorders in women who abuse alcohol. British Journal of Addiction. 1990;85(12):1633–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agras WS, Telch CF. The effects of caloric deprivation and negative affect on binge eating in obese binge-eating-disordered women. Behav Ther. 1998;29:491–03. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(4):629–8. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeppson JE, Richards PS, Hardman RK, Granley HM. Binge and purge processes in bulimia nervosa: A qualitative investigation. Eating Disorders. 2003;11:115–28. doi: 10.1080/10640260390199307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK. Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychol Bull. doi: 10.1037/a0023660. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fischer S, Smith GT, Spillane N, Cyders MA. Urgency: Individual differences in reaction to mood and implications for addictive behaviors. In: Clark AV, editor. The Psychology of Mood. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fischer S, Smith GT. Binge eating, problem drinking, and pathological gambling: Linked by common pathways to impulsive behavior. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;44:789–00. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS impulsivity scale: A four factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19:559–74. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anestis MD, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The role of urgency in maladaptive behaviors. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:3018–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fischer S, Smith GT, Anderson KG. Clarifying the role of impulsivity in bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33:406–11. doi: 10.1002/eat.10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fischer S, Anderson KG, Smith GT. Coping with distress by eating or drinking: The role of trait urgency and expectancies. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:269–4. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Settles RE, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Combs JL, Gunn RL, Smith GT. Negative urgency: A personality predictor of externalizing behavior characterized by Neuroticism, low Conscientiousness, and Disagreeableness. J Abnorm Psychol. doi: 10.1037/a0024948. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anestis MD, Selby EA, Fink EL, Joiner TE. The multifaceted role of distress tolerance in dysregulated eating behaviors. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(8):718–6. doi: 10.1002/eat.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fischer S, Smith GT, Annus AM, Hendricks M. The relationship of neuroticism and urgency to negative consequences of alcohol use in women with bulimic symptoms. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43:1199–9. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:807–28. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Derefinko K, DeWall CN, Metze AV, Walsh EC, Lynam DR. Do different facets of impulsivity predict different types of aggression? Aggressive Behavior. doi: 10.1002/ab.20387. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Billieux J, Rochat L, Rebetez MML, Van der Linden M. 2008 Are all facets of impulsivity related to self-reported compulsive buying behavior? Pers Individ Dif. 2008;44:1432–2. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Billieux J, Van Der Linden M, Rochat L. The role of impulsivity in actual and problematic use of the mobile phone. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2008;22(9):1195–10. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Billieux J, Van Der Linden M, Ceschi G. Which dimensions of impulsivity are related to cigarette craving? Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(6):1189–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the urgency traits over the first year of college. J Pers Assess. 2010;92:63–9. doi: 10.1080/00223890903381825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:807–28. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cyders MA, Smith GT. The acquired preparedness model of gambling risk: Integrating the influences of disposition and learning on the risk process. In: Esposito MJ, editor. The psychology of Gambling. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2008. pp. 2008–25. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104:193–02. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Settles RF, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:198–8. doi: 10.1037/a0017631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zapolski TCB, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Positive urgency predicts illegal drug use and risky sexual behavior. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:348–4. doi: 10.1037/a0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spillane NS, Smith GT, Kahler CW. Impulsivity-like traits and smoking behavior in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:700–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the urgency traits over the first year of college. J Pers Assess. 2010;92:63–9. doi: 10.1080/00223890903381825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cyders MA, Zapolski TCB, Combs JL, Settles RE, Fillmore MS, Smith GT. Manipulation of positive emotion and its effect on negative outcomes of gambling behaviors and alcohol consumption: The role of positive urgency. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:367–7. doi: 10.1037/a0019494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miller J, Flory K, Lynam D, Leukefeld C. A test of the four-factor model of impulsivity-related traits. Pers Individ Dif. 2003;34:1403–18. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fischer S, Smith GT. Deliberation affects risk taking beyond sensation seeking. Pers Individ Dif. 2004;36(3):527–7. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fischer S, Stojek M, Hartzell E. Effects of multiple forms of childhood abuse and adult sexual assault on current eating disorder symptoms. Eating Behaviors. 2010;11:190–2. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM, Cleary SD, Shinar O. Coping dimensions, life stress, and adolescent substance use: A latent growth analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;30:345–57. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anthony JC, Petronis KR. Early-onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;40(1):9–5. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger A. Temperament and adolescent substance use: An epigenetic approach. J Pers. 2000;68:1127–52. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.DiClemente RJ, Hansen WB, Ponton LE, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stice E, Martinez EE. Cigarette smoking prospectively predicts retarded physical growth among female adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(5):363–0. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV, Rabasca A, Pastorelli C. A questionnaire for measuring the Big Five in late childhood. Pers Individ Dif. 2003;34(4):645–64. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Markey PM, Markey CN, Tinsley BJ. Children’s behavioral manifestations of the five-factor model of personality. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(4):423–2. doi: 10.1177/0146167203261886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Measelle, et al. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roberts BW, DelVecchio WF. The rank order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shiner RL. How shall we speak of children’s personalities in middle childhood? A preliminary taxonomy. Psychol Bull. 1998;124(3):308–32. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zapolski TCB, Smith GT. Comparison of parent versus child-report of child impulsivity traits and prediction of outcome variables. 2011. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zapolski TC, Annus AM, Fried RE, Combs JL, Smith GT. The disaggregation of impulsivity in children. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism; Washington, D. C. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zapolski TCB, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, Smith GT. The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment. 2010;17:116–25. doi: 10.1177/1073191109351372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gunn RL, Smith GT. Risk factors for elementary school drinking: Pubertal status and the acquired preparedness model concurrently predict 5th grade alcohol consumption. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:617–7. doi: 10.1037/a0020334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Combs JL, Pearson CM, Smith GT. A risk model for pre-adolescent disordered eating. The Int J Eat Disord. doi: 10.1002/eat.20851. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pearson CM, Combs JL, Smith GT. A risk model for disordered eating in late elementary school boys. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:696–4. doi: 10.1037/a0020358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Combs JL, Spillane NS, Caudill L, Stark B, Smith GT. The acquired preparedness risk model applied to smoking in 5th grade children. 2011. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Settles RE, Smith GT. College student motivations to limit alcohol consumption. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism; Atlanta, GA. 2011, June. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pearson CM, Combs JL, Zapolski TCB, Smith GT. Personality and psychosocial learning predict increased eating disorder symptomatology during the transition into middle school. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Eating Disorder Research Society; Edinburgh, Scotland. 2011, September. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Smith GT, Zapolski TCB. Personality dispositions to rash action increase the likelihood of early engagement in maladaptive behaviors. Paper presented at the biannual meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Montreal, CA. 2011. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 100.Caspi A. Why maladaptive behaviors persist: Sources of continuity and change across the life course. In: Funder DC, Parke RD, Tomilinson CA, Keasey, Widaman K, editors. Studying Lives Through Time: Personality and Development. Washington, DC: Am. Psychol. Assoc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Caspi A, Roberts BW. Personality development across the life span: The argument for change and continuity. Psychol Inq. 2001;12:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smith GT, Anderson KG. Adolescent risk for alcohol problems as acquired preparedness: model and suggestions for intervention. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O’Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, alcohol, and substance abuse: Reaching teens through Brief Interventions. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Smith GT, Williams SF, Cyders MA, Kelly S. Reactive personality environment transactions and adult developmental trajectories. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:877–7. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Corbin WR, Iwamoto DK, Fromme K. Comprehensive longitudinal test of the acquired preparedness model for alcohol use and related problems. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2001;72:222–0. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Combs J, Smith GT, Flory K, Simmons JR, Hill KK. The acquired preparedness model of eating disorder risk. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:475–86. doi: 10.1037/a0018257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pearson CM, Guller L, Spillane NS, Smith GT. A developmental model of addictive behavior: From impulsivity to compulsivity. In: Columbus F, editor. Advances in Psychology Research. New York: Nova Science Publishers; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Skodol AE, Oldham JM. Phenomenology, differential diagnosis, and comorbidity of the impulsive-compulsive spectrum of disorders. In: Oldham JM, Hollander E, Skodol AE, editors. Impulsivity and compulsivity. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Engel SG, Corneliussen SJ, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, le Grange D, Crow S, Klein M, Bardone-Cone A, Peterson C, Joiner T, et al. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(3):244–51. doi: 10.1002/eat.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zapolski TCB, Settles RF, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Borderline personality disorder, bulimia nervosa, antisocial personality disorder, ADHD, substance use: Common threads, common treatment needs, and the nature of impulsivity. Indep Prac. 2010;30:20–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Linehan MM. Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Clyne C, Blampied NM. Training in emotion regulation as a treatment for binge eating: A preliminary study. Behav Change. 2004;21:269– 81. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dimeff LA, Koerner K, editors. Dialectical behavior therapy in clinical practice: Applications across disorders and settings. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Robins CJ, Chapman AL. Dialectical behavior therapy: Current status, recent developments, and future directions. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(1):73–89. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.1.73.32771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dal CS, MacDonald TK, Fong GT, Zanna MP, Elton-Marshall TE. Remembering the message: Using a reminder cue to increase condom use following a safer sex intervention. Health Psychol. 2006;25:438–3. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Horan JJ, Johnson RG. Coverant conditioning through a self-management application of the Premack principle: Its effect on weight reduction. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;2(4):243–9. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Donohew L, Zimmerman R, Cupp P, Novak S, Colon S, Abell R. Sensation seeking, impulsive decision-making, and risky sex: Implications for risk-taking and design of interventions. Pers Individ Dif. 2000;28:1079–91. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stephenson MT. Examining adolescents’ responses to antimarijuana PSAs. Hum Commun Res. 2003;29(3):343–69. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Everett MW, Palmgreen P. Influences of sensation seeking, message sensation value, and program context on effectiveness of anticocaine public service announcements. Health Commun. 1995;7(3):225–48. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lorch EP, Palmgreen P, Donohew L, Helm D, et al. Program context, sensation seeking, and attention to televised anti-drug public service announcements. Hum Commun Res. 1994;20(3):390–12. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Palmgreen P, Donohew L, Lorch EP, Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT. Television campaigns and adolescent marijuana use: Tests of sensation seeking targeting. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(2):292–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Donohew L, Palmgreen P, Lorch E, Zimmerman R, Harrington N. Attention, persuasive communication, and prevention. In: Crano WD, Burgoon M, editors. Mass media and drug prevention: Classic and contemporary theories and research. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]