In 1977, Zapol and colleagues [1] reported that the pulmonary circulation was injured in patients with ARDS, leading to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary hypertension. The investigators suggested that the pathogenesis was related to competition between alveolar distending pressure and blood flow in these patients who were ventilated with high airway pressure [2], as proposed by West et al. [3]. Pulmonary vascular remodeling also occurs with muscularization of normally non-muscularized arteries. Subsequently, using transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), 24 years later Vieillard-Baron et al. [4] reported an incidence of acute cor pulmonale (ACP) of 25 % during the first 3 days in 75 ARDS patients treated with lung protective ventilation. A few years later, the same group reported a much higher incidence of 50 % in more severe patients, all exhibiting a PaO2/FiO2 <100 mmHg [5]. The same group studied 352 patients and found that the incidence of ACP was related to elevated plateau airway pressure (Pplat) with a safe limit for the right ventricle of 27 cmH2O [6]. Since then, several questions are still unresolved, including: What is the actual incidence of ACP in a larger population? Which are the main variables associated with ACP? What is the impact of ACP on prognosis, if any? Should RV function be monitored, and, if so, how? Should clinicians adjust the ventilatory strategy to RV function? Recently published clinical studies provide answers to some of these questions.

Boissier et al. [7] reported an incidence of ACP of 22 % (95 % CI 16–27 %) in a prospective single-center study of 226 patients using TEE within the first 3 days following diagnosis of ARDS. Patients met the Berlin definition criteria for moderate to severe ARDS [8]. They were ventilated in a volume control mode with a tidal volume of 6 ml/kg, a Pplat of <30 cmH2O and a PEEP of 8–9 cmH2O [7]. In a multivariate logistic regression, independent factors associated with ACP were an infection as a cause of lung injury and the driving pressure (17 cmH2O in patients with ACP versus 14 cmH2O) [7]. The driving pressure is the distending pressure related to tidal volume, and it then depends on tidal volume (i.e., the ventilatory strategy) and also on compliance of the respiratory system (i.e., the severity of injury). Infection as a factor associated with ACP is interesting. As discussed by Boissier et al. [7], circulating cytokines may contribute to myocardial dysfunction. In addition, inflammation, including infection, is an important component of vascular remodeling in chronic pulmonary hypertension. In the acute setting, vasoconstrictors may be more important, but inflammation may also enhance pulmonary vasoconstriction [9]. In the study by Boissier et al. [7], the consequences of ACP for hemodynamics included a significant increase in heart rate, a decrease in systemic blood pressure and the need for hemodynamic support. ACP was independently associated with 28-day mortality and in-hospital mortality, as well as the McCabe and Jackson class, another cause of lung injury than aspiration, driving pressure (per cmH2O) and an elevated plasma lactate (per mmol/l) [7].

In another large prospective multicenter study of 200 patients with moderate to severe ARDS, Lhéritier et al. found a similar incidence of ACP (23, 95 % CI 17–29 %) [10]. The only factor independently associated with ACP was a PaCO2 ≥ 60 mmHg. Data on the driving pressure were not available [10]. This result is interesting because a few years ago Mekontso-Dessap et al. [11] suggested that increased PaCO2 had a major deleterious effect on RV function in very severe ARDS patients, also previously suggested by Vieillard-Baron et al. [4] in 2001. Hypercapnia is a vasoconstrictor of the pulmonary circulation [12]. Elevated PaCO2 can be a consequence of the ventilatory strategy and severity of lung injury, as suggested by the impact of an elevated pulmonary dead space fraction on prognosis [13]. Also, based on the results of the study by Lhériter et al. [10], monitoring RV function by transesophageal echocardiography was much more effective than transthoracic echocardiography. Finally, this study indicated that ACP was not associated with mortality [10]. Why was this result different from the result of the study by Boissier et al.? In the study by Lhéritier et al. [10], almost half of the patients with ACP were ventilated in the prone position compared to only 32 % of patients without ACP. It has been clearly reported that lung protective ventilation in the prone position decreases Pplat [14]. In their cohort of 352 patients, Jardin et al. [6] suggested that the effect of ACP on prognosis depends in part on Pplat with a safe limit at 27 cmH2O.

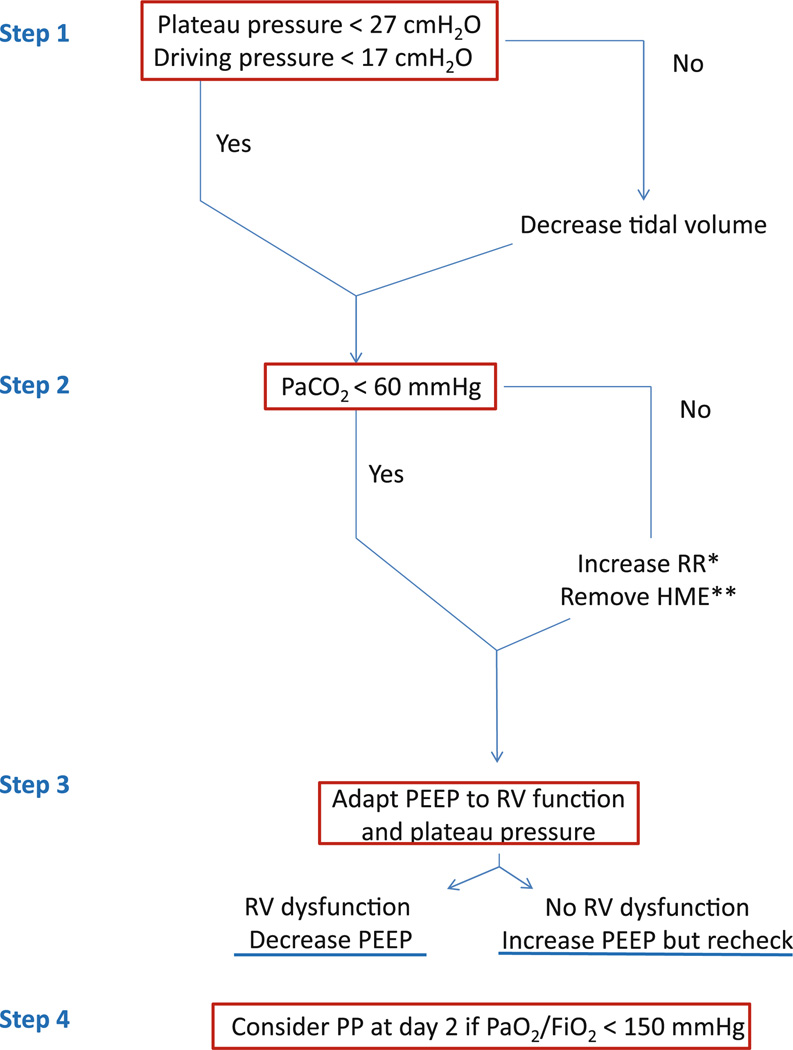

These results prompt us to recommend that clinicians consider monitoring RV function using TEE in moderate to severe ARDS patients and to adapt the therapeutic lung protective ventilation strategy according to the function of the right ventricle. This can be considered an “RV protective approach,” as illustrated in the Fig. 1. Recently, in a randomized clinical trial comparing supine to prone positioning (PROSEVA), Guerin et al. [15] reported a large beneficial effect of the prone position on reducing mortality in severe and persistent ARDS with a PaO2/FiO2 <150 mmHg. The prone positioning may have been effective in part because of the beneficial effects on the pulmonary circulation and the right ventricle. The prone position may be an ideal protective approach for improving the function of the RV because it corrects hypoxemia without increasing PEEP, and it decreases the PaCO2 and Pplat by recruiting collapsed lung zones. This result can be contrasted with the “open-lung” approach, as represented by high-frequency oscillation ventilation (HFO), which worsened mortality, with more circulatory failure and a higher vasopressor requirement [16], perhaps reflecting increased RV failure, as shown by Guervilly et al. [17]. In HFO ventilation, airway pressure remains significantly elevated during all the respiratory cycle.

Fig. 1.

Proposed approach to preventing acute cor pulmonale and limiting its consequences: a right ventricular protective approach. RR respiratory rate, RV right ventricular, HME heat and moisture exchanger, PP prone positioning, PEEP positive end-expiratory pressure. *Avoid any intrinsic PEEP. **Replace HME by a heated humidifier

However, some issues remain unclear. Do we need to turn patients with ACP to the prone position, even though PaO2/FiO2 is still >150 mmHg? Could inflammation-driven pulmonary vasoconstriction be a therapeutic target to reduce injury to the pulmonary microcirculation, for example, with novel therapeutics such as mesenchymal stromal cells or other anti-inflammatory therapies such as statins [18]? What is the effect of isolated RV dilatation without paradoxical septal motion, and is it predictive of imminent ACP/RV failure? How should the level of PEEP be adjusted in individual ARDS patients, providing that the Pplat is maintained below 27 cmH2O? Some preliminary data suggest that the effect of PEEP on the pulmonary circulation and RV function depends on the balance between recruitment and overdistension induced by application of PEEP [11]. Finally, would the RV protective approach, as presented in the Fig. 1, have a beneficial survival effect compared to a more conventional approach? Further clinical and experimental studies will be needed to address these questions.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest None.

Contributor Information

A. Vieillard-Baron, Thorax-Vascular Disease-Abdomen-Metabolism Section, Intensive Care Unit, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, University Hospital Ambroise Paré, 92104 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Faculty of Medicine Paris Ile-de-France Ouest, University of Versailles Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, 78280 Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, France; Service de Réanimation, Hôpital Ambroise Paré, 9, Avenue Charles-de-Gaulle, 92100 Boulogne, France, antoine.vieillard-baron@apr.aphp.fr, Tel.: +33-14-9095603, Fax: +33-14-9095892.

L. C. Price, Royal Brompton Hospital, Sydney Street, London SW3 6NP, UK

M. A. Matthay, Departments of Medicine and Anesthesia, Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA

References

- 1.Zapol WM, Snider MT. Pulmonary hypertension in severe acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:476–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197703032960903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zapol WM, Kobayashi K, Snider MT, Greene R, Laver MB. Vascular obstruction causes pulmonary hypertension in severe acute respiratory failure. Chest. 1977;71:306–307. doi: 10.1378/chest.71.2_supplement.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West JB, Dollery CT, Naimark A. Distribution of blood flow in isolated lung; relation to vascular and alveolar pressures. J Appl Physiol. 1964;19:713–724. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.4.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vieillard-Baron A, Schmitt JM, Augarde R, Fellahi JL, Prin S, Page B, Beauchet A, Jardin F. Acute cor pulmonale in acute respiratory distress syndrome submitted to protective ventilation: incidence, clinical implications and prognosis. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1551–1555. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200108000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vieillard-Baron A, Charron C, Caille V, Belliard G, Page B, Jardin F. Prone positioning unloads the right ventricle in severe ARDS. Chest. 2007;132:1440–1446. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Is there a safe plateau pressure in ARDS? The right heart only knows. Intens Care Med. 2007;33:444–447. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0552-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boissier F, Katsahian S, Razazi K, Thille AW, Roche-Campo F, Leon R, Vivier E, Brochard L, Vieillard-Baron A, Brun-Buisson C, Mekontso Dessap A. Prevalence and prognosis of cor pulmonale during protective ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intens Care Med. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2941-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camprota L, Antonelli M, et al. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intens Care Med. 2012;38:1573–1582. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2682-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wort SJ, Ito M, Chou PC, Mc Master SK, et al. Synergistic induction of endothelin-1 by tumor necrosis factor α and interferon γ is due to enhanced NF-kB binding and histone acetylation at specific kB sites. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24297–24305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.032524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lhéritier G, Legras A, Caille A, Lherm T, Mathonnet A, Frat JP, Courte A, Martin-Lefevre L, Gouëllo JP, Amiel JB, Vignon P. Prevalence and prognostic value of acute cor pulmonale and patent foramen ovale in ventilated patients with early acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intens Care Med. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mekontso Dessap A, Charron C, Devaquet J, Aboab J, Jardin F, Brochard L, Vieillard-Baron A. Impact of acute hypercapnia and augmented positive end-expiratory pressure on right ventricle function in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intens Care Med. 2009;35:1850–1858. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1569-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balanos GM, Talbot NP, Dorrington KL, Robbins PA. Human pulmonary vascular response to 4 h of hypercapnia and hypocapnia measured using Doppler echocardiography. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:1543–1551. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00890.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nuckton TJ, Alonso JA, Kallet RH, Daniel BM, Pittet JF, Eisner MD, Matthay MA. Pulmonary dead-space fraction as a risk factor for death in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1281–1286. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charron C, Bouferrache K, Caille V, Castro S, Aegerter P, Page B, Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Routine prone positioning in patients with severe ARDS: feasibility and impact on prognosis. Intens Care Med. 2011;37:785–790. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, et al. For the PROSEVA study group. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson ND, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, et al. For the OSCILLATE trial investigators; Canadian Critical care Trial Group. High-frequency oscillation in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:795–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guervilly C, Forel JM, Hraiech S, Demory D, Allardet-Servent J, Adda M, Barreau-Baumstark K, Castanier M, Papazian L, Roch A. Right ventricular function during high-frequency oscillation ventilation in adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1539–1545. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182451b4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman G. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2731–2740. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]