Abstract

Two new fluorescent probes of protein structure and dynamics have been prepared by concise asymmetric syntheses using the Schöllkopf chiral auxiliary. The site-specific incorporation of one probe into dihydrofolate reductase is reported. The utility of these tryptophan derivatives lies in their absorption and emission maxima which differ from those of tryptophan, as well as in their large Stokes shifts and high molar absorptivities.

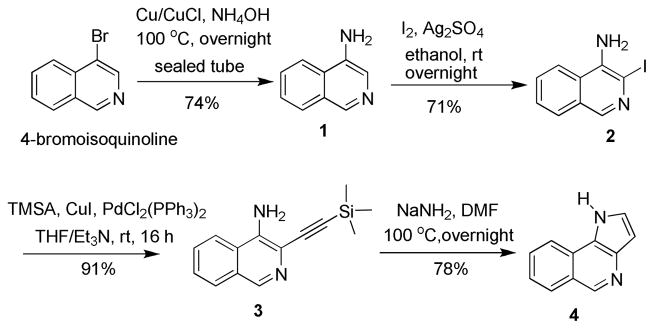

The aromatic amino acid tryptophan (Trp) is often important to protein function and structural integrity, and is also the main source of intrinsic protein fluorescence. Therefore, it has long been used as a probe for protein structure and function studies.1 However, due to its complicated photophysics and multiple occurrence in many proteins of interest, Trp cannot always be used as a suitable optical probe.2 Therefore, it seemed of interest to design novel tryptophan analogues which have more useful spectroscopic properties, and do not perturb the local environment of the target protein. Recently, the incorporation of azatryptophans as fluorescence probes in structurally modified proteins has been described.2 Among the azaindole chromophores, 4-azaindole has been identified as a promising candidate. It has strongly red-shifted fluorescence with a large Stokes shift (~130 nm).2 As its 4-azatryptophan derivative, it has been incorporated into target proteins.1 However, the fluorescence intensity and quantum yield of 4-azatryptophan are much lower than that of tryptophan itself.1 In addition, azatryptophans are hydrophilic, such that their presence in the hydrophobic core of proteins would likely modify protein structure and function.1 To overcome these limitations we have prepared more hydrophobic tricyclic tryptophan derivatives which have larger Stokes shifts (~150–160 nm) and exihibit significantly higher molar absorptivities than that of tryptophan.

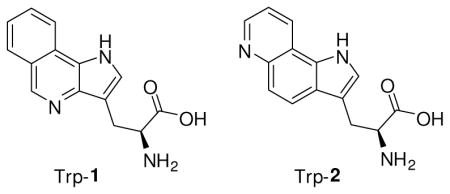

The 1H-pyrrolo[3,2-c]isoquinoline molecule consists of a benzene ring fused to a bicyclic 4-azaindole ring (Figure 1) whereas 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-f]quinoline can be considered to be 4-azaindole modified with a benzo ring spacer that separates the pyridine ring and pyrrole ring.

Figure 1.

Structure of 4-azaindole and the chromophoric moieties of the new tryptophan analogues.

To realize the asymmetric synthesis of the Trp analogues Trp-1 and Trp-2, a stereoselective strategy utilizing the Schöllkopf chiral reagent3 has been adopted. This strategy has enabled the successful synthesis of the unnatural S-amino acids. In recent years, the use of misacylated tRNAs has facilitated the introduction of unnatural amino acids into predetermined positions in peptides and proteins.4–9 Using the same strategy, we describe the incorporation of Trp-1 into position 17 of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR).

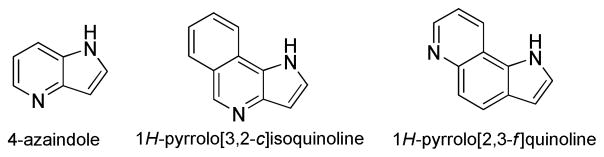

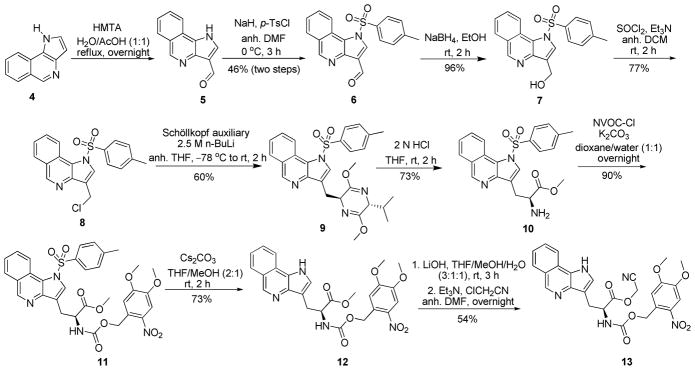

For the asymmetric synthesis of Trp-1, the required indole 4 was prepared in four steps from commercially available 4-bromoisoquinoline according to the method of Briere et al.10 with some modifications. The synthesis began with amination of 4-bromoisoquinoline (Scheme 1). The reaction was carried out using Cu/CuCl couple, which induced the transformation at much lower temperature11 than the reported procedure (autoclave, aq NH4OH, CuSO4, 150–200 °C).12 Iodination with I2 and Ag2SO4 provided 4-amino-3-iodoisoquinoline (2) in satisfactory yield.13 Sonogashira coupling of trimethylsilylacetylene (TMSA) and 4-amino-3-iodoisoquinoline (2) proceeded very smoothly at room temperature. The desired ethynyl derivative 3 was obtained in 91% yield, whereas the reported procedure involved coupling with 4-amino-3-bromoisoquinoline at higher temperature in lower yield.10 4-Amino-3-ethynyl derivative 3 was then heated to reflux with NaNH2 in DMF to effect cyclization into key intermediate 4.10

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Pyrroloisoquinoline 4

Pyrroloisoquinoline 4 was next converted to its respective amino acid derivative. Key intermediate 13 was obtained in nine steps from 4 (Scheme 2). Pyrroloisoquinoline 4 was first formylated under Duff reaction conditions14 to yield aldehyde 5, the latter of which was subjected to N-tosylation with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (p-TsCl) and sodium hydride to afford 6 in 46% overall yield.15 Reduction of aldehyde 6 to alcohol 7 using NaBH4 in EtOH proceeded almost quantitatively.14 Chlorination of alcohol 7 with thionyl chloride afforded 8 in 77% yield.16 Asymmetric synthesis of the amino acid precursor was carried out using the Schöllkopf reagent (R)-2,5-dihydro-3,6-dimethoxy-2-isopropylpyrazine.3 Regioselective lithiation (n-BuLi, THF, −78 °C) of the chiral auxiliary produced the lithium enolate which afforded the adduct 9 from 8 with high diastereoselectivity (only one diastereomer was detectable in the 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra). Mild hydrolysis (2 N HCl) afforded the α-substituted amino acid methyl ester 10.3 Amine 10 was protected as the NVOC carbamate to yield 11 in 90% yield.17 The NVOC group was chosen as it can be removed by UV irradiation.18,19 N-Detosylation of 11 was performed using cesium carbonate in 2:1 THF–MeOH to yield 12 in 73% yield.20 Methyl ester 12 was then hydrolyzed to afford the free acid which was subsequently treated with chloroacetonitrile to afford the requisite cyanomethyl ester 13 in 54% yield.17

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Cyanomethyl Ester 13

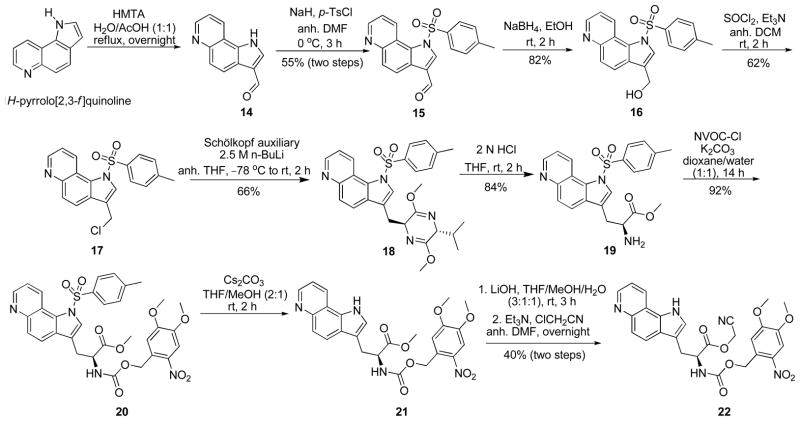

The synthesis of N-NVOC cyanomethyl ester 22 of the 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-f]quinoline followed a similar procedure (Scheme 3). Initially, the commercially available pyrroloquinoline was formylated to yield 1414 which was N-tosylated with p-TsCl and NaH, affording 15 in 55% overall yield.15 Reduction of aldehyde 15 with NaBH4 in EtOH afforded alcohol 16 in 82% yield.14 Chlorination of 16 with thionyl chloride then provided 17.16 Regioselective lithiation (n-butyllithium, THF, −78°C) of the Schöllkopf reagent produced the lithium enolate which afforded adduct 18 with high diastereoselectivity (only one diastereomer was detectable in the 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra).3 Mild hydrolysis (2 N HCl) provided α-substituted amino acid methyl ester 193 which was protected as the NVOC carbamate to yield 20 in 92% yield.17 N-Detosylation of 20 using cesium carbonate in 2:1 THF–MeOH afforded ester 21.20 Hydrolysis of 21 afforded the free acid, which was activated as cyanomethyl ester 22 in 40% overall yield.17 The syntheses of 13 and 22 were quite robust, providing workable routes to these compounds preparatively.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Cyanomethyl Ester 22

Next, we evaluated the photophysical properties of the tryptophan analogues as potentially useful fluorescence probes. The study was carried out using the respective N-acetylated methyl esters to mimic their anticipated behavior when present in proteins. The synthesis of the N-acetylated methyl esters of the Trp analogues (Trp-1 and Trp-2) is illustrated in Scheme S1 in the Supporting Information. Both the methyl esters had larger Stokes shifts and greater molar extinction coefficients than those of tryptophan (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spectroscopic Properties of N-Acetylated Methyl Esters of Trp Analogues in MeOH

| Trp analogue | λabs, max (nm) | ε (M−1cm−1) | λex, max (nm) | λem, max (nm) | ΦF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trp | 280 | 6900 | 280 | 346 | 0.18 |

| Ac-Trp-1-OMe | 260 | 18100 | 260 | 420 | 0.10 |

| Ac-Trp-2-OMe | 272 | 15500 | 272 | 421 | 0.03 |

Tryptophan is commonly used as a fluorophore in biophysical studies and the emission maxima for both Ac-Trp-1-OMe and Ac-Trp-2-OMe are substantially red-shifted from that of tryptophan.21 This means that the emission signals from these Trp analogues can be easily isolated from those of the native tryptophans in the protein. Both the increased molar absorptivity and the shifted emission spectra (distinct from normal tryptophans and the other normal aromatic amino acids) make Trp-1 and Trp-2 potentially attractive probes for protein conformational studies.

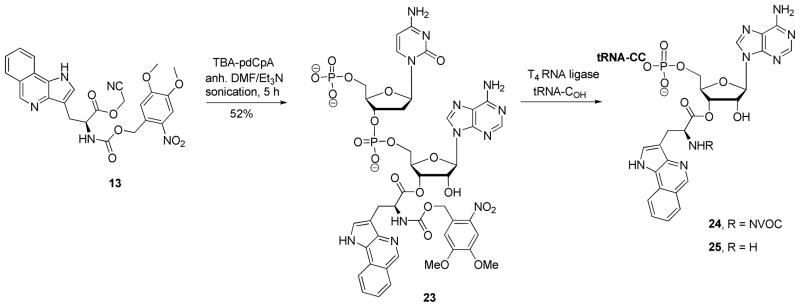

In order to evaluate the properties of Trp-1 as a constituent of the protein DHFR, this amino acid was used to activate a suppressor tRNA (Scheme 4). Treatment of cyanomethyl ester 13 with the tris(tetrabutylammonium) salt of pdCpA22 in anhydrous DMF afforded pdCpA ester 23 in 52% yield.17 The aminoacylated dinucleotide was ligated to an abbreviated tRNACUA-COH transcript in the presence of T4 RNA ligase and ATP17 to afford NVOC-aminoacyl-tRNA 24 Activated tRNA 24 was deprotected by UV irradiation to afford free aminoacyl-tRNA 25.17

Scheme 4.

Preparation of Suppressor tRNACUA Activated with Trp-1

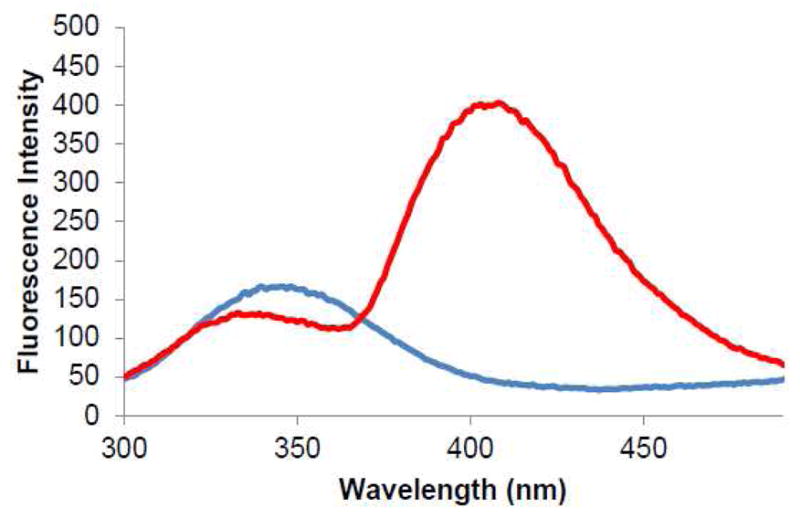

The activated suppressor tRNA was employed in an in vitro protein synthesizing system programmed with DHFR mRNA having a CGGG codon at position 17 of the elaborated protein to introduce Trp-1 into position 17 of DHFR (Figure S1, Supporting Information). To ensure that the modified protein was properly folded, the ability of this modified enzyme to catalyze the reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate was studied.17 Substitution of position 17 with Trp-1 was reasonably well tolerated (Figure S2), affording a construct which consumed NADPH 65% as efficiently as wild-type DHFR under turnover conditions at pH 7.0 and 37 °C. The modified DHFR was subjected to irradiation at 260 nm and exhibited an emission spectrum centered at 409 nm for the incorporated Trp-1 (Figure 2, red curve). Thus, it was possible to selectively excite and monitor Trp-1 in the modified DHFR, which also contains five Trps.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence emission spectra of a modified DHFR (Trp-1 at position 17) (red) and wild-type DHFR (blue). λex = 260 nm.

In summary, we report the synthesis of two new tricyclic tryptophan derivatives (Trp-1 and Trp-2) and demonstrate that Trp-1 can be introduced into DHFR with minimal disruption of function and could be selectively monitored in the presence of five Trp residues in that DHFR, underscoring its potential as a fluorescence probe for studying protein conformation and dynamics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Stephen Benkovic and C. Tony Liu for helpful discussions regarding the photophysical properties of the Trp derivatives. This work was supported by NIH research grant GM 092946.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures, characterization data, and spectra are included. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Merkel L, Hoesl MG, Albrecht M, Schmidt A, Budisa N. Chembiochem. 2010;11:305. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lepthien S, Hoesl MG, Merkel L, Budisa N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802804105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schollkopf U, Groth U, Westphalen K, Deng C. Synthesis. 1981:969. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heckler TG, Zama Y, Naka T, Hecht SM. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:4492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heckler TG, Chang LH, Zama Y, Naka T, Hecht SM. Tetrahedron. 1984;40:87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noren CJ, Anthony-Cahill SJ, Griffith MC, Schultz PG. Science. 1989;244:182. doi: 10.1126/science.2649980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heckler TG, Chang LH, Zama Y, Naka T, Chorghade MS, Hecht SM. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1468. doi: 10.1021/bi00302a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldini G, Martoglio B, Schachenmann A, Zugliani C, Brunner J. Biochemistry. 1988;27:7951. doi: 10.1021/bi00420a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hecht SM. In: Protein Engineering. RajBhandary UL, Koehrer C, editors. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briere JF, Dupas G, Queguiner G, Bourguignon J. Heterocycles. 2000;52:1371. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang F, Zewge D, Houpis IN, Volante RP. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:3251. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernabeu MC, Díaz JL, Jiménez O, Lavilla R. Synth Commun. 2004;34:137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sy W. Synth Commun. 1992;22:3215. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su WG, Jia H, Dai G. WO 2011079804 A1. Certain triazolopyridines and triazolopyrazines, compositions thereof and methods of use there for. 2011 Jul 07;

- 15.Yao CH, Song JS, Chen CT, Yeh TK, Hsieh TC, Wu SH, Huang CY, Huang YL, Wang MH, Liu YW, Tsai CH, Kumar CR, Lee JC. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;55:32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramakrishna VSN, Shirsath VS, Kambhampati RS, Rao VSVV, Jasti V. WO 2004048330 A1. N-arylsulfonyl-3-substituted indoles having serotonin receptor affinity, process for their preparation and pharmaceutical composition containing them. 2004 Jun 10;

- 17.Chen S, Fahmi NE, Wang L, Bhattacharya C, Benkovic SJ, Hecht SMJ. Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:12924. doi: 10.1021/ja403007r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Patchornik A, Amit B, Woodward RB. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:6333. [Google Scholar]; (b) Amit B, Sehavi V, Patchornik A. J Org Chem. 1974;39:192. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson SA, Ellman JA, Schultz PG. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:2722. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bajwa JS, Chen G, Prasad K, Repic O, Blacklock TJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:6425. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tucker MJ, Ovola R, Gai F. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:4788. doi: 10.1021/jp044347q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson SA, Noren CJ, Anthony-Cahill SJ, Griffith MC, Schultz PG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9649. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.23.9649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.