Abstract

The lentiviruses, human and feline immunodeficiency viruses (HIV-1 and FIV, respectively), infect the brain and cause neurovirulence, evident as neuronal injury, inflammation, and neurobehavioral abnormalities with diminished survival. Herein, different lentivirus infections in conjunction with neural cell viability were investigated, concentrating on type 1 interferon-regulated pathways. Transcriptomic network analyses showed a preponderance of genes involved in type 1 interferon signaling, which was verified by increased expression of the type 1 interferon-associated genes, Mx1 and CD317, in brains from HIV-infected persons (P<0.05). Leukocytes infected with different strains of FIV or HIV-1 showed differential Mx1 and CD317 expression (P<0.05). In vivo studies of animals infected with the FIV strains, FIVch or FIVncsu, revealed that FIVch-infected animals displayed deficits in memory and motor speed compared with the FIVncsu- and mock-infected groups (P<0.05). TNF-α, IL-1β, and CD40 expression was increased in the brains of FIVch-infected animals; conversely, Mx1 and CD317 transcript levels were increased in the brains of FIVncsu-infected animals, principally in microglia (P<0.05). Gliosis and neuronal loss were evident among FIVch-infected animals compared with mock- and FIVncsu-infected animals (P<0.05). Lentiviral infections induce type 1 interferon-regulated gene expression in microglia in a viral diversity-dependent manner, representing a mechanism by which immune responses might be exploited to limit neurovirulence.

Keywords: HIV-1, FIV, type 1 interferon, tetherin, CD317, BST-2, microglia

The immunosuppressive lentiviruses, including human, simian, feline, and bovine immunodeficiency viruses (HIV, SIV, FIV, and BIV, respectively) are widely recognized for their capacity to cause immune dysregulation and eventual immunodeficiency (1, 2). Like many retroviruses, lentiviruses are also highly neurotropic and infection frequently results in the development of neurological disease, termed neurovirulence (3). Lentivirus-mediated neurovirulence is manifested as inflammation within the nervous system with ensuing neuronal damage or death, culminating in behavioral deficits. Neurovirulence is a consequence of the combined effects of cell damage caused by virus-encoded proteins in a molecular diversity-dependent manner coupled with deregulated (antiviral) host-mediated processes (i.e., immunopathology; ref. 4). These virus- and host-associated effects in the nervous system act collectively to reduce host survival and overall fitness (5). Indeed, patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders exhibit reduced survival compared with patients without neurological disease (6). The precise determinants of neurovirulence remain unclear although both host factors (age, genetic background, comorbidities, and immune status) and viral properties (replicative capacity, neural cell tropism, and virus-encoded toxic factors) have been implicated in neuropathogenesis (7). The properties of individual viral strains or quasi-species have been difficult to study among populations infected with HIV type 1 (HIV-1), in part because of immense virus genetic diversity in the setting of an outbred host species. Among animal models, the role of individual lentiviral strains and their relative virulence properties are better defined (2).

Interferons (IFNs) represent the prototype host immune regulators of antiviral responses in most mammals as well as lower species (8). Recently, host restriction factors have come to the forefront of the understanding of lentivirus pathogenesis with the discovery of multiple restriction factors that limit HIV-1, HIV-2, SIV, and FIV infections (9–12). Among the recently described host restriction factors, CD317 (also termed BST-2 or tetherin) has gained wide recognition because it interacts with the HIV-1 Vpu and the HIV-2 and FIV Env, as well as the SIV Nef (13–18). The expression of most of these host restriction factors is induced by type 1 IFNs, including IFN-α and IFN-β (9, 13, 19–23), the activation of which is usually reflected by persistent expression of myxovirus resistance 1 (Mx1; refs. 24, 25). Indeed, several previous studies have implicated IFN-α in HIV neuropathogenesis (26, 27).

FIV is closely related to the other immunodeficiency lentiviruses, including HIV-1 and SIV, in terms of genomic structure, as well as pathogenic properties (28–35). FIV infects lymphocytes (36), macrophages (37), and microglia in the brain, causing immunodeficiency and neurovirulence in domestic cats (38 – 43). We have previously shown that FIV infection of the brain is dependent on myeloid cell infection and results in a specific neurological phenotype caused by neuroinflammation and neuronal loss (42, 44). FIV-mediated neurovirulence is evident in terms of impaired motor and neurocognitive functions, occasionally accompanied by seizures and agitated behavior, thus recapitulating many of the features observed in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (45–48).

In the present study, we investigated the differential neuroimmune responses during lentivirus infections, concentrating on type 1 IFN-related genes because this network of molecules is critical for viral control, including CD317 expression, which had not been previously examined in the brain. By comparing different lentivirus strains, we found type 1 IFN signaling to be virus strain dependent and CD317 expression to influence inflammatory gene expression in microglia, leading to neurovirulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

The use of autopsied brain tissues and biofluids is part of ongoing research (Protocol 2291) approved by the University of Alberta Human Research Ethics Board (Biomedical), and written informed consent documents were signed before or at the collection time. The protocols for obtaining postmortem brain samples comply with all federal and institutional guidelines, with special respect for the confidentiality of the donor’s identity; blood was collected from live patients and healthy volunteers under the same protocol. Human fetal tissues were obtained from 15- to 19-wk aborted fetuses directly from the clinic with written informed consent from the patient approved under Protocol 1420 by the University of Alberta Human Research Ethics Board (Biomedical). All animal experiments were performed according to Canadian Council on Animal Care (http://www.ccac.ca/en) and local animal care and use committee guidelines. The experiments involving FIV-infected cats were part of ongoing studies (Protocol 449) approved by the University of Alberta Animal Care and Use Committee.

Viruses

Culture supernatants from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) infected with either HIV-1 JRFL (HIVJRFL) or HIV-1 SF162 (HIVSF162) were utilized for in vitro infection experiments. Similarly, supernatants from feline MYA1 T cells or PBMCs infected with FIV chimera (FIVch) (49) or FIVncsu (31, 50) were used for in vitro and in vivo experiments. Lentivirus production was measured using reverse transcriptase assay (51).

Cells

HeLa and BHK-21 cell lines were maintained in DMEM (Gibco, Burlington, ON, Canada) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco). SK-N-SH (neuroblastoma) and U373 (astrocytoma) cells were grown in MEM/10% FBS, while the THP1 monocytic cell line was grown in RPMI/10% FBS plus 1% glutamine. All cells were maintained at 37°C 5% CO2. Human and feline PBMCs were isolated from the blood of healthy subjects by Histopaque 1077 (Sigma, Oakville, ON, Canada) purification. Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were then negatively selected from PBMCs by plastic adherence properties of monocytes and monocyte-derived cells. PBLs were maintained in RPMI/15% FBS with phytohemagglutinin-P (PHA-P) stimulation for 3 d, after which cells were stimulated with human interleukin-2 (IL-2) and then mock or lentivirus (HIV/FIV) infected. Supernatants and cell suspensions were collected at d 7 and 10 postinfection.

Tissues

Human fetal tissues were obtained from 15- to 19-wk aborted fetuses with the approval of the Alberta Human Research Ethics Board (Biomedical). Neural cells were isolated and maintained in MEM/10% FBS supplemented with 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, 0.1% dextrose, and gentamicin [human fetal microglial (HFM) medium] as described previously (51). Human fetal astrocytes (HFAs) were used from 5 to 10 passages after tissue collection, while HFM supernatants were collected 7 to 10 d after isolation. Human fetal neurons (HFNs) were cultured in medium containing cytosine arabinoside and used within 2 wk of culture (52). Human white matter tissue was collected at autopsy and stored at −80°C.

Antibodies and reagents

Primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry included mouse monoclonal anti-human HLA-DP, HLA-DQ, and HLA-DR [clone CR3/43; major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II); DakoCytomation, Burlington, ON, Canada]; ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1; Wako, Tokyo, Japan); and mouse monoclonal anti-feline macrophage (MAC387; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). A rabbit polyclonal antibody to LILRA4 (ILT7; Abcam) was used for detecting human and feline ILT7 by immunohistochemistry and Western blotting. The rabbit polyclonal antibody used to detect human BST-2 by immunohistochemistry, immunoprecipitation, and flow cytometry and feline BST-2 by immunohistochemistry was generated as described previously (53). Rabbit preimmune serum was used as control. Western blotting-related antibodies included mouse anti-BST-2 (Abnova, Walnut, CA, USA) and goat polyclonal anti-β-actin antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Mouse anti-feline CD4 and CD8 antibodies used for flow cytometry were acquired from Dr. Peter Moore (University of California, Davis, CA, USA). Antibody signal was amplified using biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse immunoglobulin antibody (immunohistochemistry; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), goat polyclonal anti-mouse/rabbit IgG antibody conjugated to HRP (Western blot; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), and donkey polyclonal anti-rabbit Ig conjugated to PE (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The recombinant IFN-α used for stimulating cells was purchased from PBL Biomedical Laboratories (Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Alberta Animal Care Committee. Adult pregnant cats (queens) were housed in the University of Alberta animal care facility and maintained according to the Canadian Committee of Animal Care guidelines. Queens were negative for feline retroviruses [FIV, feline leukemia virus (FeLV)] by PCR analysis and serologic testing. Animals were injected intracranially (right frontal lobe) 1 d postpartum with 200 μl of virus (104 TCID50/ml; FIVch or FIVncsu or mock infected) by a 30-gauge needle (44). Animals were monitored over 12 wk postinfection, during which time body weight was measured, neurobehavioral were tests performed, and blood samples were collected. Animals were euthanized by pentobarbital overdose at 12 wk postinfection. Brain and plasma were collected and snap-frozen at −80°C for subsequent total RNA or protein extractions. The left hemisphere of the brain was fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) for immunocytochemical analysis.

Transfections and cocultures

BHK cells were grown to ~50% confluence in 6-well plates and then transfected according to the manufacturer’s protocol with 4 μg pCDNA3.0 or pCDNA3.1 human BST-2 (53) diluted in 500 μl Opti-MEM containing 10 μl lipofectamine. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 6 h, the medium was removed, and 2 ml of fresh 10% FBS/DMEM was added. Cells were collected 48 h post-transfection, and BST-2 expression was monitored by flow cytometry. For coculture experiments, 2 ml HFM medium alone or 3 × 105 HFM cells in HFM medium was added after the 6-h incubation. After 48 h, the supernatants were collected, and the cells were solubilized in TRIzol reagent.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

IFN-α and IL-1β protein levels in supernatants from HFM cells cocultured with BHK cells transiently transfected with either empty vector or pCDNA3.1 CD317 were measured using the ELISA for human IFN-α (pan-specific; MABTech, Cincinnati, OH, USA) and the human IL-1α/IL-1F2 DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Burlington, ON, Canada), respectively.

Real-time RT-PCR

Host and viral gene expression was measured by real-time RT-PCR as reported previously (44, 54). HIV/FIV− and HIV/FIV+ tissue suspended in TRIzol reagent was homogenized using a Fast-Prep-24 tissue homogenizer (MP, Solon, OH, USA). RNA was extracted using choloroform:isoamyl alcohol and purified using an RNeasy purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). cDNA from tissue samples was synthesized from 1 μg RNA. In vitro cell culture samples solubilized in TRIzol reagent were prepared similarly, except that RNA template used for cDNA synthesis ranged from 300 ng to 1 μg per sample. All samples were analyzed by semi-quantitative real-time PCR on a MyiQ thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Threshold cycle values were normalized to GAPDH and are represented as average relative fold change (RFC) compared with control. Plasma and neural viral load was determined by quantitative real-time PCR as described previously (44). Briefly, the number of viral copies was determined by comparing threshold cycle values of FIV pol amplicons to a standard curve derived using 10-fold serial dilutions (1010 copies to 100 copies) of in vitro transcribed FIV pol.

Flow cytometry

To measure expression of human BST-2 in BHK-21 cells, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and collected. Samples were incubated with either (1:250) preimmune rabbit serum or rabbit anti-BST-2 serum diluted in PBS/2% FBS for 1 h at 4°C, then washed and incubated with (1:500) PE-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody for 45 min at 4°C. Feline PBMCs were isolated from the blood of FIV−, FIVch and FIVncsu animals at 8 and 12 wk postinfection. PBMCs were stained with mouse anti-feline CD4 and CD8 antibodies, followed by goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to FITC. PBMCs labeled with secondary antibody alone served as control. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using BD FACSDiva and Flow Jo software (TreeStar Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Neurobehavioral assessment

Neurobehavioral parameters in 12-wk FIVmock (n=7), FIVch (n=10), and FIVncsu (n=5) animals were evaluated. Locomotor ability was determined by analyzing the ink footprints formed by cats walking across a suspended plank (44). Distance between the right and left paw placement was measured, and the variance in gait width was calculated. Spatial memory and cognitive ability were measured using a modified T-maze (44). The duration and number of errors to completion of the maze were recorded. The object-memory test was utilized to measure spatial and object memory (44). Animals were required to step over a 6-cm moveable barrier with their forelimbs to reach a food reward. Their ability to remember the height and position of the barrier was monitored using reflective dots placed on the outside of the cat’s hindlimbs. Animal performance was recorded on film. The number of successful attempts was counted and recorded as a percentage of total.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (55). Briefly, HIV/FIV− and HIV/FIV+ paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded brain tissue sections were sectioned and mounted onto slides. Slides were rehydrated; antigen was retrieved using 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and then immunostained with the antibodies indicated above. Signal was revealed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (DAB; brown) and/or 5-bromo-4-chloroindolylphosphate (BCIP; blue; Vector Laboratories) and then dehydrated and mounted in Acrytol (Leica Microsystems, Concord, ON, Canada). Slides were imaged using a Zeiss Axioskop 2 upright microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Neuronal counts

FIV− and FIV+ brain tissue sections (10 mm anterior to bregma) were deparaffinized, and neurons were stained with cresyl violet (0.1%) solution (56). Slides were then dehydrated and mounted with Acrytol (Leica Microsystems). Stained cells were counted at ×400 view in 5 separate fields for each animal. The total number of cells for each treatment group was summed and averaged.

Tissue cultures

HFAs, HFM cells, and HFNs were cultured in 24-well (infection) or 6-well plates (stimulation) at a final 70% confluence (56). Cells were incubated with IFN-α (Sigma; 0, 1, and 10 IU/ml), and samples were collected at 24 and/or 48 h postincubation. HFAs and HFM cells were lysed in 0.5% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 150 mM NaCl) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and immunoprecipitated using preimmune (PI) or anti-CD317 (αCD317) rabbit serum, separated by reducing SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blot using mouse αCD317 antibody. HFM cells incubated with either medium (mock treatment) or HIV-1 were collected at d 1 and 7 postinfection and solubilized in TRIzol, and cDNA was prepared. Human PBLs (huPBLs) and HFM cells were mock infected (HIV−) or infected with one of two strains of HIV-1 (HIVJRFL or HIVSF162) in triplicate. Cells were collected at d 4, 7, and 10 postinfection as indicated and solubilized with TRIzol reagent. Similarly, feline PBLs (fePBLs) were mock infected (FIV−) or infected with one of two strains of FIV (FIVch or FIVncsu).

Deep sequencing analyses

Total RNA from each patient was depleted of rRNA. cDNA libraries were then constructed and subjected to massively parallel sequencing, as described previously (57). Multiplexed reads were deconvoluted according to sequence tags and aligned with the human transcriptome and genome (57). Matching reads were retained if they were above threshold for sequence quality (Q20), did not contain homopolymers, satisfied read-pairing logic, and mapped unambiguously (i.e., to only 1 accession). Putative hits were then subjected to contaminant screening and were removed if they matched non-human species RNA-seq libraries generated in house. All data were normalized within each run by total tag count. Interrun variation of values was accounted for by normalizing to read length followed by a total intensity normalization approach that relies on the assumption that the transcriptome-wide gene expression profiles between individual samples are similar. The average number of tags for each gene within a sampling run was plotted against the average of the same gene in the sampling run being compared. Linear regression was performed, and the slope of the resulting trend line was used to scale the values for comparison between runs. Gene ontology analysis was performed using the DAVID Bioinformatic Resources 6.7 Functional Annotation tool (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/), and gene network analysis was performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, Redwood, CA, USA; http://www.ingenuity.com).

Statistical analyses

Depending on the assay, Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons relative to control, Kruskal-Wallis test, or the Student’s t test was applied. Correlation analyses were performed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r), using GraphPad Prism 5 for OS X (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA; http://www.graphpad.com). Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Host gene expression in brain during HIV-1 infection

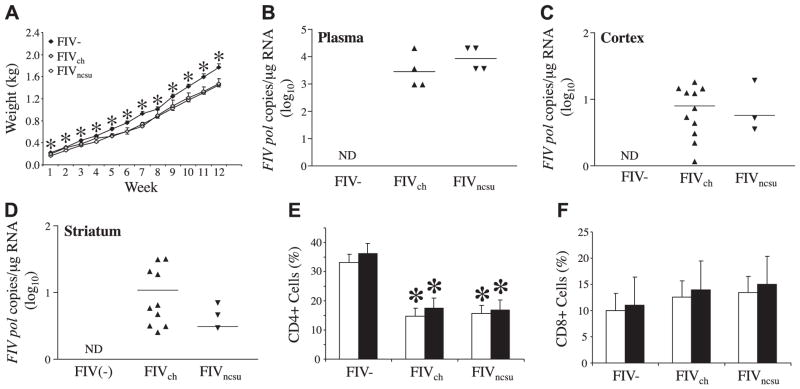

To investigate host responses to HIV-1 infection in the brain using an unbiased approach, we performed deep sequencing of transcriptional profiles in cerebral white matter, because this anatomic region is especially vulnerable to lentivirus infection and injury. Massively parallel sequencing of cDNA prepared from cerebral white matter RNA disclosed differential expression of multiple groups of genes between HIV+ (n=4) vs. HIV− (n=4) autopsied brains. The sequence tag lengths ranged from 36 to 77 nt, and the maximum number of unambiguous tags was from 5,500,000 to 11,700,000, depending on the individual patient sample. Of these, 3,000,000–7,000,000 tags/patient mapped to the human genome; 200–21,000 of the remaining tags mapped unambiguously to bacterial or viral sequences. Genes implicated in microtubule depolymerization and protein complex disassembly were highly induced in HIV+ brains, while genes involved in axonogenesis were comparatively suppressed in the HIV+ brains based on Gene Ontology (GO) analyses (Fig. 1A), underscoring the neuronal injury that occurs during HIV-1 infection. Gene network pathway analyses of differentially expressed host transcripts, comparing HIV+ with HIV− brains showed that the most robust model (IPA score 31) was defined by several pathway hubs frequently implicated in viral pathogenesis including those involving NF-κB, TCR, and interactions among multiple IFN-related genes, including IFN-α, IFIT1, ISGF3, IFNA7, and OAS (Fig. 1B, indicated by asterisks). These findings verified that axonal injury was an integral feature of HIV-1 infection together with the important role of type 1 IFN pathways in the brain during HIV-1 infections.

Figure 1.

Neuronal maintenance genes are suppressed with IFN signaling pathway induction in the brain during HIV/AIDS. A) GO analysis revealed significant overrepresentation (P<0.05; Benjamini’s test) of several functional categories of genes among the transcript tags increased or decreased by ≥4-fold in HIV+ compared with HIV− cerebral white matter specimens. Data are represented as relative-fold enrichment (RFE). B) Network pathway analyses based on brain tag abundances displayed differential expression of specific genes in brains from HIV+ and HIV− persons, disclosing either decreased (green) or increased (red) expression, or having established associations with the input reference dataset (white; IPA 31). Asterisks indicate genes associated with IFN signaling.

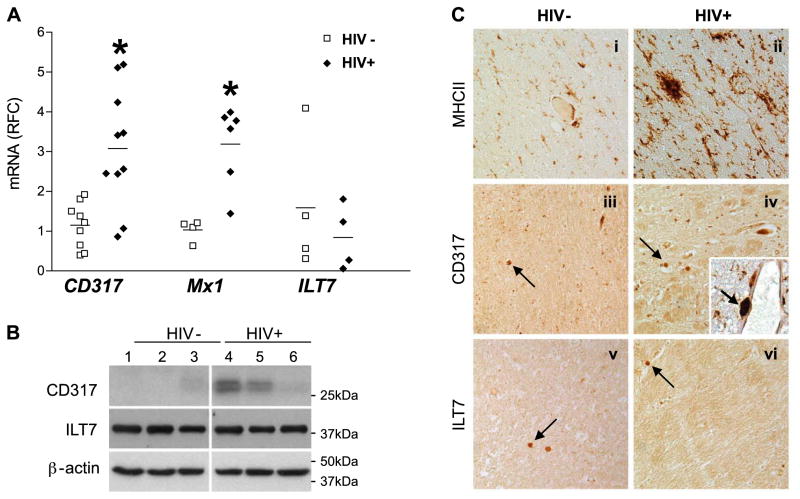

Type 1 IFN-associated gene expression in human brain

IFN signaling is widely recognized for its capacity to modulate the expression of host factors, such as Mx1 and CD317, during HIV-1 infection, although little is known about CD317 and its putative receptor’s expression levels in the brain. In cerebral white matter-derived RNA from HIV+ and HIV− persons, the expression of CD317 was investigated. CD317 transcripts were >3-fold higher in brain tissues from HIV+ compared with HIV− patients (Fig. 2A). Although IFN-α transcript levels did not differ between the 2 clinical groups (data not shown), Mx1 was also induced in brain tissues from HIV-infected persons. Correlation analyses showed that Mx1 and CD317 were closely associated across groups (r=0.744; P<0.01). Immunoblot analysis of white matter from HIV+ and HIV− persons showed that CD317 expression was differentially increased in the brain of HIV+ patients (Fig. 2B). CD317 was detected as a doublet, which is compatible with its differential glycosylation states (58 – 60), although more likely as 2 alternatively translated isoforms (61, 62). In contrast, the expression of a putative receptor for CD317, termed ILT7, was similar for both transcript (Fig. 2A) and protein (Fig. 2B) levels in HIV+ and HIV− persons’ cerebral white matter. To define the cell types expressing each of these molecules, immunohistochemistry was performed. MHC II expression, indicative of the capacity of immune cells to present antigens, was detected in brain sections from HIV− patients (Fig. 2Ci) but was markedly increased in the brains of HIV+ persons (Fig. 2Cii). CD317 immunoreactivity was detected in few cells within the white matter from HIV− patients (Fig. 2Ciii) although its immunoreactivity was more evident in white matter of HIV+ persons (Fig. 2Civ). CD317 was colocalized with MHC II immunoreactivity, particularly in perivascular cells resembling macrophages (Fig. 2Civ, inset). ILT7 immunoreactivity was detected in occasional rod-like cells resembling activated macrophages in brain sections from both HIV− (Fig. 2Cv) as well as HIV+ patients (Fig. 2Cvi). From these studies, it was apparent that type 1 IFN-regulated genes were induced in the brain during HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Figure 2.

Type 1 IFN-related genes are increased in cerebral white matter myeloid cells in HIV/AIDS. A) Among HIV+ and HIV− white matter specimens, CD317 and Mx1 transcript levels were increased in HIV+ brains, while ILT7 transcript abundance was similar across groups. Values are represented as average RFC compared with HIV−. B) Cerebral white matter tissue samples were analyzed under reducing conditions by Western blot using mouse anti-CD317 and rabbit anti-LILRA4 (ILT7) antibodies followed by appropriate secondary antibodies, revealing that CD317 immunoreactivity was higher in the HIV-1+ brains, but ILT7 was similar in both groups. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for β-actin to confirm equal loading of samples. C) HIV− and HIV-1+ paraffin-embedded white matter brain sections were immunolabeled with antibodies to MHC II (i, ii), CD317 (iii, iv), and ILT7 (v, vi). HIV-1+ brain sections displayed increased MHC II and CD317 immunoreactivity compared with HIV− brain sections. Arrows indicate immunostained myeloid cells. Inset: HIV-1+ tissue sections disclosed colocalization of MHC II (DAB; brown) and CD317 (BCIP substrate; blue). Arrowhead indicates double-stained myeloid cell. All images captured at ×200 view. *P < 0.05; Kruskal-Wallis test.

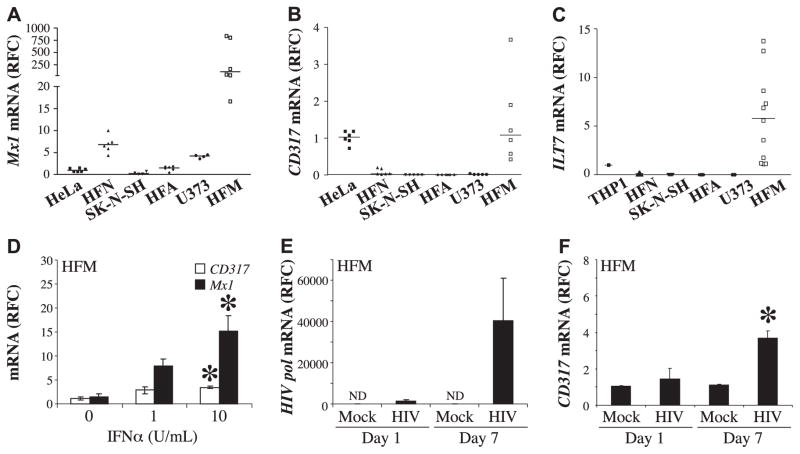

Ex vivo type 1 IFN-associated gene expression human microglia

The above studies showed that type 1 IFN-related molecules, including CD317, were detected in human brain samples; thus, its expression was explored further using cultured primary human neural cells. Mx1 transcript levels were increased in HFA (Fig. 3A); of interest, Mx1 was also increased in HFNs (Fig. 3A). CD317 transcript levels were consistently increased in HFM cells compared with HFAs, HFNs, and immortalized cell lines (Fig. 3B). Further, the constitutive expression of CD317 protein by HFM cells was confirmed by immunopreciptation (Supplemental Fig. S1A) and its cell surface expression by flow cytometry (Supplemental Fig. S1B). Similarly, ILT7 transcripts were detected in HFM cells but not in other cell types (Fig. 3C). Exposure of HFM cells to IFN-α induced both CD317 and Mx1 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3D), which was verified by immmunoprecipitation studies showing induction of CD317 immunoreactivity in exposed microglia (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Although no CD317 transcript could be detected in unstimulated primary human astrocytes, transcript and protein could be induced on IFN-α exposure (Supplemental Fig. S1C). Exposure of HFNs to IFN-α at the same concentrations did not reduce neuronal viability (data not shown). To extend these studies, we investigated the effects of HIV-1 infection of HFM cells, using the HIV-1 SF162 strain. HIV-1 pol transcript levels were detected at d 1 and 7 postinfection (Fig. 3E), indicating active infection accompanied by an induction of CD317 in HFM cells at both d 1 and 7 postinfection (Fig. 3F). Further, the constitutive expression of CD317 protein by HFM cells was confirmed by immunopreciptation (Supplemental Fig. S1A) and its cell surface expression by flow cytometry (Supplemental Fig. S1B). Thus, microglia constitutively expressed CD317 at the cell surface, which was induced by HIV-1 infection likely in an IFN-dependent manner, indicating that myeloid cells such as microglia were able to respond to infection by mounting a prototypic antiviral response.

Figure 3.

Primary human microglial cells constitutively express Mx1, CD317, and ILT7; CD317 expression is induced by IFNα or HIV infection. A–C) Mx1 (A), CD317 (B), and ILT7 (C) transcript levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR from human cultured cells (Hela, THP1, HFN, SK-N-SH, HFA, U373, and HFM), revealing high constitutive expression of all genes in HFM cells. D) HFM cells incubated with IFNα at different concentrations showed induction of CD317 and Mx1 transcripts. E) HFM cells incubated with either medium (mock) or HIV-1SF162 showed that HIV-1 pol transcript was detected at d 1 and 7 postinfection. F) CD317 transcripts were detected at both d 1 and 7 in mock- and HIV-infected HFM cells, but there was a significant increase in HIV-infected cells at d 7. Values were derived from ≥3 biological replicates; and transcript values are represented as RFC. ND, not detected. *P < 0.05; Bonferroni’s test.

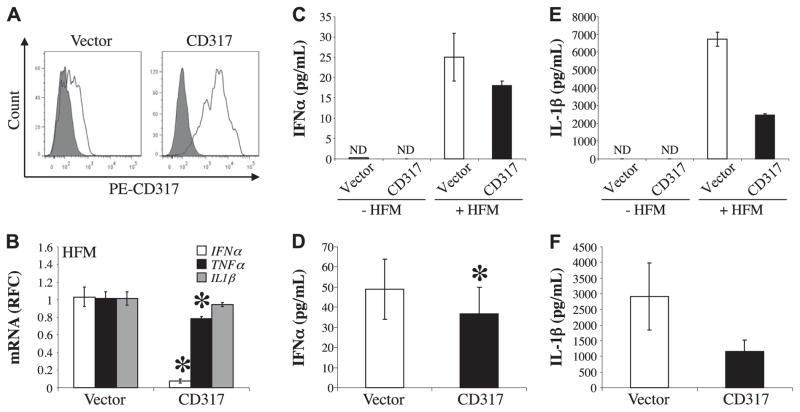

CD317 modulation of host inflammatory responses

To examine the effects of CD317 on neuroimmmune responses, HFM cells were cocultured with BHK cells transiently expressing human CD317, and the immune response was monitored by real-time RT-PCR and/or by ELISA. Human CD317 was expressed in BHK cells by transfection and cell surface protein expression was monitored by flow cytometry (Fig. 4A). Cocultures of HFM cells with BHK cells transiently transfected with either an empty vector or the CD317-encoding vector revealed significant suppression of both human IFN-α and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) transcript levels in cells exposed to the CD317-transfected BHK cells emphasizing the ability of CD317 to modulate immune gene expression (Fig. 4B). The down-regulation of IFN-α and TNF-α was specific as the transcript levels of other immune genes such as that of IL-1β were not suppressed. Analyses of IFN-α protein levels in culture medium, measured by ELISA, confirmed that exposure to CD317-transfected cells reduced IFN-α (Fig. 4C), which was verified by comparing multiple replicate samples (Fig. 4D). Although IL-1β transcript abundance was unaffected, IL-1β protein was reduced by CD317 exposure (Fig. 4E), which was confirmed by multiple replicates (Fig. 4F). Thus, CD317 exposure diminished inflammatory gene expression in human microglia, similar to its previously reported actions in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (63).

Figure 4.

Expression of immune mediators by human microglia is modulated by exposure to CD317. A) BHK cells transiently expressing either pCDNA 3.0 (vector) or pCDNA 3.1 CD317 (CD317) were incubated with preimmune rabbit serum (gray) or with rabbit anti-CD317 serum (white) followed with PE-conjugated secondary antibody and then analyzed by flow cytometry. B) HFM cells (3×105/sample) were incubated with BHK transiently expressing vector or CD317 for 48 h. Human IFN-α, TNF-α, and IL-1β transcript levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR. Values were normalized to human GAPDH to eliminate the contribution from the BHK and are represented as average RFC compared with HFM cells cocultured with BHK transfected with empty vector. C) Representative IFN-α protein levels from the supernatants of BHK cells transiently transfected with empty vector (vector) or pCDNA3.1 CD317 (CD317) either cultured alone (−HFM) or cocultured with HFM cells (+HFM) were measured by ELISA. D) Averaged IFN-α protein detected in the supernatants of HFM cells cocultured with BHK cells transfected with empty vector or construct containing CD317 from 5 independent experiments show significantly suppressed IFN-α levels. E) Representative IL-1β protein levels from BHK ± HFM cells transiently transfected with empty vector or pCDNA3.1 CD317, as determined by ELISA. F) Average IL-1β levels detected in supernatants from 4 independent experiments. ND, not detected. *P < 0.05; Student’s t test.

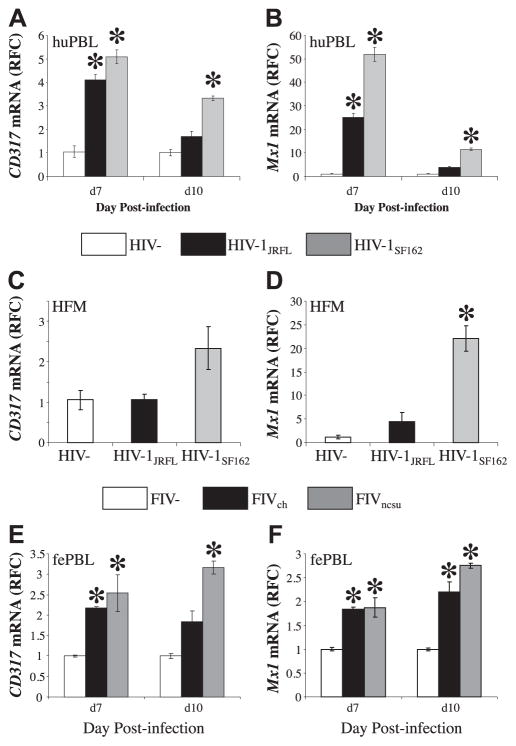

Lentivirus diversity-dependent induction of host responses

Molecular diversity within lentiviruses is a pivotal biomarker of HIV/AIDS disease stage and drug resistance, as well as a determinant of lentivirus cell tropism and pathogenesis (64). Thus, the ability of different lentiviruses to induce type 1 IFN signaling, including CD317 expression, was explored in relation to infection by different lentivirus strains. Human PBLs were infected with HIV-1JRFL or HIV-1SF162 at matched input titers; both viruses are CCR5-dependent viruses, although HIV-1JRFL is derived from the frontal lobe of a patient with HIV-associated dementia, while HIV-1SF162 was cultured from the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with toxoplasmic encephalitis. Mx1 and CD317 transcript levels were examined at d 7 and 10 postinfection. HIV-1SF162 induced Mx1 transcript levels in human PBLs significantly more than HIV-1JRFL- or mock-infected cells. (Fig. 5A). These studies also showed that there was a differential expression of CD317 at both time points (Fig. 5B), with HIV-1SF162 inducing the highest levels of CD317. Despite the differential expression of CD317 and Mx1, virus production was similar for both viruses, evident by reverse transcriptase activity in supernatants (Supplemental Fig. S2A). Likewise, infection of human microglial cells showed that HIV-1SF162 induced expression of CD317, although CD317 expression in HIV-1JRFL-infected microglial cells was similar to mock-infected microglial cells (Fig. 5C). These findings were recapitulated in studies of Mx1 transcript levels, which disclosed a modest increase in HIV-1JRFL-infected cells but with substantially higher Mx1 transcript levels mediated by HIV-1SF162 infection (Fig. 5D). Again, viral gene expression did not differ in microglial cells infected with either HIV-1 strain (Supplemental Fig. S2B).

Figure 5.

CD317 induction is dependent of lentivirus diversity. huPBLs were mock (HIV−) or HIV infected with one of two strains of HIV-1 (HIV-1JRFL and HIV-1SF162) at matched input titers in triplicate. Cells were collected at d 7 and 10 postinfection and solubilized with TRIzol, and cDNA was prepared. A, B) CD317 (A) and Mx1 (B) transcripts were measured by real-time RT-PCR, showing that HIV-1JRFL consistently induced CD317 and Mx1. C, D) Likewise, mock- or HIV-infected HFM cells showed increased CD317 (C) and Mx1 (D) transcript levels in the cells infected with HIV-1JRFL. E, F) Similarly, fePBLs were mock infected, FIV−, or infected with one of two strains of FIV (FIVch and FIVncsu) at matched input titers, revealing that CD317 (E) and Mx1 (F) transcripts were increased in the cells infected with FIVncsu. Values represent average relative RFC compared with HIV− (A–D) or FIV− (E, F). *P < 0.05; Dunnett’s test.

To understand the relationship between FIV infection and type 1 IFN signaling, FIV infection of leukocytes by 2 representative FIV strains, FIVch and FIVncsu, was examined; these viruses diverge substantially at the nucleotide level within the envelope gene (Supplemental Fig. S3). Both viruses induced CD317 expression following infection at matched input titers, but FIVncsu induced higher levels of CD317 transcripts at both time points (Fig. 5E). Similar findings were observed for Mx1 expression (Fig. 5F). At d 7, the expression of Mx1 was similar in both FIVch- and FIVncsu-infected PBLs, while it was significantly higher at d 10 for the FIVncsu-infected PBLs. FIV pol expression in leukocytes was similar for both FIV strains (Supplemental Fig. S2C). These studies indicated that both HIV and FIV infection differentially induced expression of Mx1 and CD317 depending on the individual virus strain.

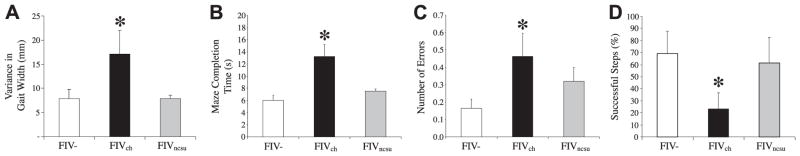

Neurobehavioral analyses

The most immediate and robust indicator of neurovirulence is quantitative neurobehavioral performance for both HIV-1 and FIV infections (65). Executive (memory and decision making) and motor abnormalities (delayed responses and ataxia) represent frequently encountered clinical signs and symptoms among different groups of patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (66). The in vivo effect of the 2 FIV strains, FIVch and FIVncsu, was compared with mock-infected (FIV−) animals. FIVch-infected animals showed increased variance in gait width compared with FIVncsu-infected and FIVmock animals at 12 wk postinfection (Fig. 6A). Analyses of motor speed in terms of maze completion time revealed that FIVch-infected animals were slower than FIVncsu-infected and FIV− animals (Fig. 6B). To assess memory and decision making in the same groups, the number of errors incurred during completion of the maze task was recorded, disclosing that FIVch-infected animals made more errors than FIVncsu-infected and FIV− animals (Fig. 6C). Finally, to assess motor-memory performance, animals performed an object memory task, in which FIVch-infected animals completed fewer successful steps compared with FIVncsu-infected and FIV− animals (Fig. 6D). Overall, these studies demonstrated that FIVch-infected animals exhibited a greater number of deficits indicating more severe neurovirulence, compared with FIVncsu-infected and FIV− animals. These neurobehavioral observations revealed that FIVch-infected animals demonstrated greater neurobehavioral impairment than FIVncsu-infected compared with FIV− animals, providing a model for investigating differential type 1 IFN signaling in relation to neurovirulence.

Figure 6.

FIVch-infected animals exhibit greater neurobehavioral deficits compared with FIVncsu- or mock-infected animals. Neurobehavioral and neurocognitive parameters of 12-wk-old FIV− (n=7), FIVch (n=10), and FIVncsu (n=5) animals were evaluated. A) Gait function was determined by analyzing the width of inked footprints of cats walking across a suspended plank. Distance between the right and left paw placement was measured, and variance in width was calculated showing increased width in the FIVch-infected animals. B, C) Motor speed and memory ability were measured using a modified T-maze; time duration (B) as well as the number of errors (C) made during completion of the maze were recorded, revealing that the FIVch-infected animals were slower and made more mistakes. D) Object-memory test measured spatial object memory; animals were required to step over a 6-cm moveable barrier with their forelimbs to reach a food reward. Their ability to recall the height and position of the barrier was monitored using reflective dots placed on the outside of the cat’s hindlimbs. The number of successful attempts was recorded as a percentage, with the FIVch animals exhibiting worsened performance. *P < 0.05; Dunnett’s test.

Viral burden and immunodeficiency in vivo

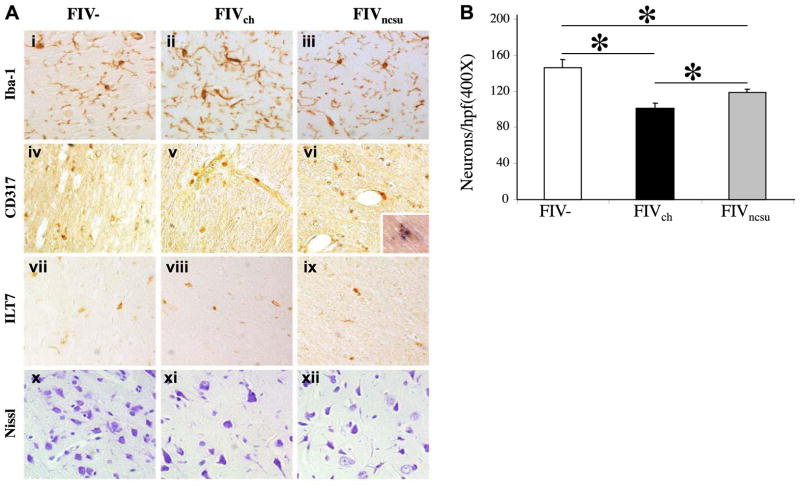

Animals were followed for 12 wk following infection as neonates, during which time their weights were monitored, showing that both FIVch- and FIVncsu-infected animals exhibited less weight gain than the FIV− animals (Fig. 7A). Measurements of viral load at wk 12 postinfection showed that viral pol RNA levels in plasma from both infected groups were similar (3.5–4.0 log10/μg RNA), but viral RNA was not detected in the FIV− group (Fig. 7B). Analyses of viral load in brain showed that pol was detectable in both FIVch- and FIVncsu-infected animals, albeit at lower levels than in plasma, but there was no difference in viral burden in cortex (Fig. 7C) and striatum (Fig. 7D) between groups infected with each virus. These studies were complemented by measuring feline CD4-immunopositive T-cell percentages in blood, which showed that both FIVch- and FIVncsu-infected animals demonstrated significantly depressed CD4+ T-cell counts at 8 and 12 wk postinfection (Fig. 7E). Conversely, blood CD8+ T-cell levels were modestly increased in both FIVch- and FIVncsu-infected animals at both time points (Fig. 7F). These studies indicated that both FIVncsu and FIVch induced similar levels of immunosupression together with comparable levels of viral burden in both plasma and brain.

Figure 7.

In vivo viral load and CD4 T cell suppression are independent of FIV diversity. Animals were infected with either FIVch or FIVncsu 1 d postpartum. A) Weights were recorded on a weekly basis for 12 wk, revealing less weight gain among the FIV-infected animals. B–D) Viral load in plasma (B), cerebral cortex (C), and striatum (D) was measured by semiquantitative real-time RT-PCR using primers for FIV pol, disclosing similar viral copy numbers for each virus, although levels were higher in plasma than in brain. Virus quantity was determined on comparison with a FIV pol standard curve. E, F) At 8 and 12 wk, PBMCs were isolated from blood, and T-cell subpopulations were identified by flow cytometry. Percentages of CD4 (E) and CD8 (F) T cells of total PBMCs are indicated, showing similar levels of CD4 T-cell suppression in both FIV-infected groups. Open bars, 8 wk; solid bars, 12 wk. *P < 0.05; Dunnett’s test.

In vivo host neuroimmune gene expression

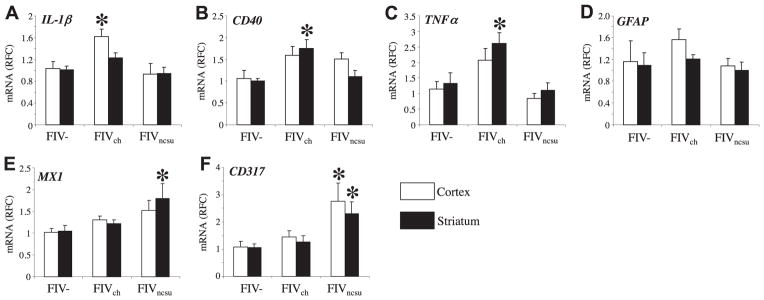

Neuroinflammation is a cardinal feature of lentivirus infections of the nervous system, defined largely by activation of leukocytes and astroglial cells. IL-1β transcript abundance was increased in the cortex of FIVch-infected animals compared with FIV− and FIVncsu-infected animals’ brains (Fig. 8A). CD40 showed increased expression in FIVch-infected animals in both cortex and striatum, including white matter, while FIVncsu-infected animals showed increases in cortex only compared with mock-infected animals (Fig, 8B). Similarly, TNF-α transcript levels were increased in FIVch-infected animals compared with FIVncsu-infected and FIV− animals in both cortex and striatum (Fig. 8C) while GFAP expression did not differ across groups in both cortex and striatum (Fig. 8D). In contrast, Mx1 transcript levels were increased in FIVncsu-infected animals, particularly in the striatum, compared with FIVch and FIV− animals (Fig. 8E). These latter findings were associated with induction of CD317 transcript levels in FIVncsu-infected animals compared with FIVch and FIV− animals in both cortex and striatum (Fig. 8F). Correlation analyses of gene expression in both the cortex and striatum revealed that the expression of both CD317 and Mx1 was positively associated across groups and with other type 1 IFN-related genes including IRF3 and IRF9 (P<0.05), in contrast to other genes, e.g., IFN-α, IL-1β, and TNF-α, which did not show significant positive or negative correlations (data not shown). These observations emphasized the differential expression of immune markers in the brain depending on the individual viral strain in relation to type 1 IFNs.

Figure 8.

In vivo induction of immune genes is FIV diversity dependent. Host gene expression from 12-wk-old uninfected (mock, n=6) and FIV (FIVch, n=12; FIVncsu, n=7)-infected animals was determined. IL-1β (A), CD40 (B), TNF-α (C), GFAP (D), Mx1 (E), and CD317 (F) transcript levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. FIVch-infected animals showed increased CD40 (A), TNF-α (B), and IL-1β (C) levels, while FIVncsu-infected animals displayed increased Mx1 and CD317 levels in cerebral cortex and/or striatum. Results are expressed as average RFC as compared with mock treatment. *P < 0.05; Dunnett’s test.

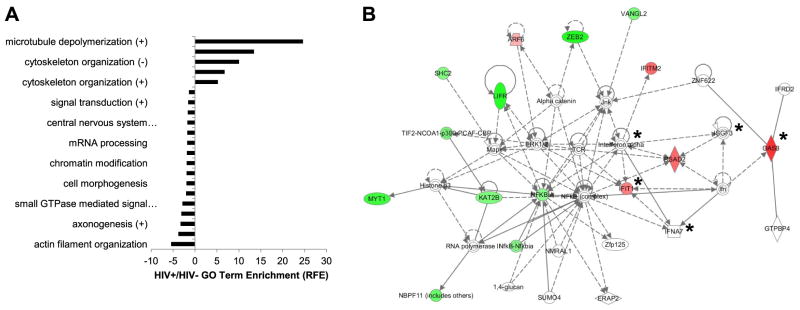

Neuropathological analyses

To verify the above findings, the expression of different immune cell markers was examined in the brains of FIV-infected and mock-infected animals. Iba1 immunoreactivity was present in FIV− animals’ brains (Fig. 9Ai) but increased on cells resembling microglia in the brains of FIVch-infected animals (Fig. 9Aii) compared with FIVncsu-infected animals (Fig. 9Aiii). CD317 immunoreactivity was detectable in mock-infected brains (Fig. 9Aiv) and in FIVch-infected animals (Fig. 9Av) but was increased in the perivascular regions of FIVncsu-infected animals (Fig. 9Avi) and was colocalized within MAC387-expressing myeloid cells (Fig. 9Avi, inset). The putative CD317 receptor, ILT7, was expressed in FIV− (Fig. 9Avii), FIVch-infected (Fig. 9Aviii), and FIVncsu-infected animals (Fig. 9Aix) at comparable levels for all groups. Nissl staining demonstrated that neurons were abundant in the parietal cortex from FIV− animals (Fig. 9Ax), but there were fewer in the FIVch- and FIVncsu-infected animals. Neuronal injury and loss is a key feature of lentivirus neurovirulence, which is accompanied by neurobehavioral deficits. Analyses of cortical neuronal counts showed that Nissl+ neurons were reduced in the brains of FIVch- and FIVncsu-infected animals compared with the FIV− animals, but neuron counts were also reduced in FIVch-infected compared with FIVncsu-infected animals (Fig. 9B). Thus, neuronal preservation was associated with increased type 1 IFN signaling, principally on myeloid cells during FIV infection.

Figure 9.

In vivo neuronal viability is FIV diversity dependent. A) FIV−, FIVch-infected, and FIVncsu-infected paraffin-embedded tissue sections were immunostained with antibodies against Iba1 (myeloid cell activation marker; i–iii), CD317 (iv–vi), and ILT7 (vii–ix), as well as Nissl stained (x–xii). Inset: FIV+ tissue stained for MAC387 (DAB; brown) and CD317 (BCIP substrate; blue), ×600 view. All images except the inset were captured at ×200 view. B) Neuronal density was determined by counting Nissl-stained images of the cerebral cortical regions of FIV− (n=4), FIVch-infected (n=5), and FIVncsu-infected (n=6) sections. Average number of neurons in multiple fields per animal in each group is shown. *P < 0.05; Dunnett’s test.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, type 1 IFN-regulated gene expression in the brain was a prominent feature of lentivirus infection and was associated with reduced in vivo neurovirulence. This study represents the first report of CD317/tetherin/BST-2 expression in the brain showing that CD317 abundance on microglia was increased by both HIV-1 and FIV infections, albeit contingent on the individual lentivirus strain. CD317 expression in brain myeloid cells (microglia) was associated with type 1 IFN signaling in the setting of in vivo neurovirulence. Viral RNA levels in brain, plasma, and cultured leukocytes were seemingly unaffected by the relative CD317 expression or the individual lentiviral strain. In contrast, exposure of CD317 to cultured human microglial cells suppressed both type 1 IFN and proinflammatory cytokine expression, which was mirrored in vivo by increased CD317 on myeloid cells in association with reduced TNF-α and IL-1β expression in the FIVncsu-infected animals that showed limited neurovirulence. The current studies based on unbiased deep sequencing of cerebral white matter extend the understanding of HIV neuropathogenesis by revealing different aspects of axonal injury together with activation of type 1 IFN signaling. Moreover, these observations highlight the importance of lentivirus molecular diversity and associated immune mechanisms leading to differing outcomes in in vivo neurovirulence.

Earlier studies indicated that individual lentivirus strains exhibit differing severities of neurovirulence (67–69). HIV-1 clade diversity at a population level appears to be predictive of neurovirulence, including neurocognitive impairment, depending on the individual study (7, 70), possibly through varying effects on viral mutagenesis (71) within individual viral genes, including env and tat (42, 72–76). Several groups have shown that distinct mutations within brain-derived HIV-1 B clade sequences in env (77–80) and vpr (51) are correlated with the occurrence of HIV-associated dementia. Experimental models support the notion that lentiviral diversity influences neurovirulence. For example, coinfection of pigtail macaques with neurotropic and immunosuppressive SIV strains produces neurovirulence, while monoinfections with each virus fail to produce neurovirulence (81–85). Previous studies of FIV infections also point to strain-dependent neurovirulence (48, 86). Earlier studies from our group indicate that FIV strains vary in their capacity to mediate neurovirulence which in part was related to immunosuppression (42). In fact, this effect was principally attributed to molecular diversity within the env gene (41, 87) without significant differences in brain viral burden.

Here, we compared two neurotropic FIV strains, FIVch and FIVncsu, which belong to the same clade but diverge at a nucleotide level, particularly in the envelope gene. Infection by these viruses resulted in differential severity of neurovirulence, despite similar levels of immunosuppression and viral burdens in both plasma and brain. These findings recapitulate earlier studies that showed viral burden in brain was not a robust predictor of in vivo neurovirulence despite coinfection by different FIV strains (88). Notably, CD317 was highly induced by the less neurovirulent strain, FIVncsu, in conjunction with the IFN-α induced gene, MX1, within the brain. Conversely, the more neurovirulent strain, FIVch, caused TNF-α and IL-1β induction in the brain, similar to observations in the brains of humans with HIV-associated dementia (89–91). HIV Vpu counteracts host restriction in humans by interacting with CD317, resulting in its surface down-regulation and/or degradation (10, 13–15, 53, 92). Recent evidence indicates that FIV Env likely counteracts CD317 restriction of FIV (93). The molecular mechanisms by which this restriction is achieved have not yet been elucidated, although envelope diversity might be an important determinant (94). Germane to this latter issue is that the env gene differs substantially (>20% at the nucleotide level) between the two viruses used in our study, in contrast to the pol gene (unpublished results). The variation in their sequences might be sufficient to allow for differential restriction properties, possibly resulting in the cell surface and/or intracellular accumulation of CD317. Of interest, viral burden in brain, plasma, and cultured leukocytes was similar among different viral strains, suggesting CD317 could exert other actions such as modulation of the host immune responses, ultimately influencing neurovirulence.

The contribution of CD317 to health and development remains uncertain. CD317 is modulated by IFN exposure and is able to regulate the induction of proinflammatory molecules such as TNF-α, which is highly pathogenic to the nervous system during lentivirus infections (95–97). CD317 is an IFN-induced transmembrane protein, which inhibits the release of several enveloped viruses from infected cells, although the precise interactions between CD317 and specific viral proteins vary depending on the viral species (13, 14). CD317 also exerts direct effects on host immune responses by engaging a putative cell surface receptor, ILT7, to regulate the expression of several cytokines implicated in lentivirus pathogenesis, such as TNF-α and type 1 IFNs (63). CD317 is expressed in a majority of cell types, including myeloid cells, (98, 99), which are the cells in the nervous system productively infected by lentivirus. The contribution of host restriction factors, including CD317, to neurovirulence is unknown. CD317-null mice do not exhibit a distinctive phenotype, although infection of CD317-null mice with a virulent retrovirus results in great levels of viral replication and immunopathology compared with wild-type mice (100). Interestingly, the structure of CD317 resembles that of PrP with a glycosylated ectodomain, suggesting that it may play an important yet undefined physiological role (59). A putative receptor for CD317, the orphan receptor ILT7, has been shown to modulate immune responses by down-regulating TNF-α and IFN-α expression, possibly through a mechanism that might involve signaling through the ILT7-FcεRIγ complex (63). This process was described initially in plasmacytoid dendritic cells, but the present data indicate that CD317 exposure to microglial cells, which also express ILT7, results in suppression of immune modulators, including TNF-α and IFN-α, as well as IL-1β. These findings provide a direct link between CD317 expression and the molecules implicated in the immunopathology of lentivirus neurovirulence (89, 101–105). The induction of CD317 by HIV-1 and FIV infections with ensuing suppression of inflammatory molecules might represent a parallel process by which the host immune system counters the pathogenic effects of a neurovirulent virus.

There is precedent for differential modulation of innate immune responses determining outcomes related to neurovirulence. Some reports have indicated a positive correlation between neurological deficits and type I IFN expression in response to viral infection within the brain/cerebrospinal fluid (106). Treatment of patients with pegylated IFNα causes depression and transient delirium, although sustained neurocognitive impairment or ensuing neuronal injury is not evident (107). Of interest, type I IFN receptor-deficient mice infected with a reovirus do not develop neurological signs despite increased viral titers (108). The time course of the immune response to lentivirus infections, particularly IFN production, can affect progression to disease (109). ILT7-related receptors have been previously implicated in HIV-1 disease outcome, specifically in influencing the cytokine secretion profile to control HIV-1 replication (110, 111). The evidence suggests that HIV-1 elite controllers are able to maintain undetectable viral loads in the absence of antiretroviral therapy, because their circulating myeloid dendritic cells produce reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokines, likely as a consequence of distinct expression of LILRB1 and LILRB3 (112), proteins related to ILT7.

SIV infection of African green monkeys (a natural host model) results in a controlled Th1 response with a corresponding strong and rapidly attenuated IFNα response with high brain viral loads in the absence of neurovirulence (113). In contrast, Asian pigtail and rhesus macaques (pathogenic models) combat infection with a heightened Th1 response with a concomitant and sustained type I IFN response, usually with an abundance of virus in the brain (114–116). Corresponding to the type I IFN regulation in African nonhuman primates, we report the rapid up-regulation of several IFN-stimulated genes including CD317 and Mx1 in the brains of FIVncsu-infected animals. In contrast, neurovirulence severity was correlated with IFN-β, MxA, and TNF-α transcript levels in SIV-infected macaques (117). The present studies highlight the close interrelationship between the viral molecular diversity and host responses underlying neurovirulence; individual viral strains exhibited differing levels of neurovirulence independent of viral burden and immunosuppression in matched hosts, but host adaptive responses also varied, with different outcomes depending on the specific virus. These studies raise the possibility of enabling protective strategies through activation of host cellular pathways such as the CD317-ILT7 axis to mitigate the neuropathogenic effects of lentivirus infections. Thus, the development of specific ligands or inducers of ILT7 signaling pathways might be a therapeutic strategy in the future for treating neurological diseases including viral infections in which innate immune responses determine the disease processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.P. and E.A.C. hold Canada Research Chairs (Tier 1) in Neurological Infection and Immunity and Human Retrovirology, respectively. C.P. is an Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (AIHS) Senior Scholar. J.G.W. is an AIHS Fellow. These studies were supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to C.P. and E.A.C.).

Abbreviations

- AIDS

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- BCIP

5-bromo-4-chloroindolylphosphate

- DAB

3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- fePBL

feline peripheral blood lymphocyte

- FIV

feline immunodeficiency virus

- FIVch

feline immunodeficiency virus chimera

- GO

Gene Ontology

- HFA

human fetal astrocyte

- HFM

human fetal microglial

- HFN

human fetal neuron

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HIV-1/2

human immunodeficiency virus type 1/2

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- huPBL

human peripheral blood lymphocyte

- Iba1

ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1

- IFN

interferon

- IL-1β/2

interleukin-1β/2

- IPA

Ingenuity Path Analysis

- MHC II

major histocompatibility complex class II

- Mx1

myxovirus resistance 1

- PBL

peripheral blood lymphocyte

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- RFC

relative fold change

- SIV

simian immunodeficiency virus

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

References

- 1.Clements JE, Zink MC. Molecular biology and pathogenesis of animal lentivirus infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:100–117. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.1.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zink MC, Laast VA, Helke KL, Brice AK, Barber SA, Clements JE, Mankowski JL. From mice to macaques–animal models of HIV nervous system disease. Curr HIV Res. 2006;4:293–305. doi: 10.2174/157016206777709410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Power C. Retroviral diseases of the nervous system: pathogenic host response or viral gene-mediated neurovirulence? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:162–169. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01737-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Scarano F, Martin-Garcia J. The neuropathogenesis of AIDS. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:69–81. doi: 10.1038/nri1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335:936–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vivithanaporn P, Heo G, Gamble J, Krentz HB, Hoke A, Gill MJ, Power C. Neurologic disease burden in treated HIV/AIDS predicts survival: a population-based study. Neurology. 2010;75:1150–1158. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d5bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gannon P, Khan MZ, Kolson DL. Current understanding of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders pathogenesis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:275–283. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834695fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoggins JW, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr Opin Virol. 1:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neil S, Bieniasz P. Human immunodeficiency virus, restriction factors, and interferon. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:569–580. doi: 10.1089/jir.2009.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauser H, Lopez LA, Yang SJ, Oldenburg JE, Exline CM, Guatelli JC, Cannon PM. HIV-1 Vpu and HIV-2 Env counteract BST-2/tetherin by sequestration in a perinuclear compartment. Retrovirology. 2011;7:51. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirchhoff F. Immune evasion and counteraction of restriction factors by HIV-1 and other primate lentiviruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fadel HJ, Poeschla EM. Retroviral restriction and dependency factors in primates and carnivores. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2011;143:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neil SJ, Zang T, Bieniasz PD. Tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by HIV-1 Vpu. Nature. 2008;451:425–430. doi: 10.1038/nature06553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Damme N, Guatelli J. HIV-1 Vpu inhibits accumulation of the envelope glycoprotein within clathrin-coated, Gag-containing endosomes. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1040–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang F, Wilson SJ, Landford WC, Virgen B, Gregory D, Johnson MC, Munch J, Kirchhoff F, Bieniasz PD, Hatziioannou T. Nef proteins from simian immunodeficiency viruses are tetherin antagonists. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauter D, Schindler M, Specht A, Landford WN, Munch J, Kim KA, Votteler J, Schubert U, Bibollet-Ruche F, Keele BF, Takehisa J, Ogando Y, Ochsenbauer C, Kappes JC, Ayouba A, Peeters M, Learn GH, Shaw G, Sharp PM, Bieniasz P, Hahn BH, Hatziioannou T, Kirchhoff F. Tetherin-driven adaptation of Vpu and Nef function and the evolution of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1 strains. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia B, Serra-Moreno R, Neidermyer W, Rahmberg A, Mackey J, Fofana IB, Johnson WE, Westmoreland S, Evans DT. Species-specific activity of SIV Nef and HIV-1 Vpu in overcoming restriction by tetherin/BST2. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000429. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta RK, Mlcochova P, Pelchen-Matthews A, Petit SJ, Mattiuzzo G, Pillay D, Takeuchi Y, Marsh M, Towers GJ. Simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein counteracts tetherin/BST-2/CD317 by intracellular sequestration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20889–20894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907075106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neil SJ, Sandrin V, Sundquist WI, Bieniasz PD. An interferon-alpha-induced tethering mechanism inhibits HIV-1 and Ebola virus particle release but is counteracted by the HIV-1 Vpu protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes R, Towers G, Noursadeghi M. Innate immune interferon responses to Human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22:257–266. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Damme N, Goff D, Katsura C, Jorgenson RL, Mitchell R, Johnson MC, Stephens EB, Guatelli J. The interferon-induced protein BST-2 restricts HIV-1 release and is downregulated from the cell surface by the viral Vpu protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng G, Lei KJ, Jin W, Greenwell-Wild T, Wahl SM. Induction of APOBEC3 family proteins, a defensive maneuver underlying interferon-induced anti-HIV-1 activity. J Exp Med. 2006;203:41–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blasius AL, Giurisato E, Cella M, Schreiber RD, Shaw AS, Colonna M. Bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 is a specific marker of type I IFN-producing cells in the naive mouse, but a promiscuous cell surface antigen following IFN stimulation. J Immunol. 2006;177:3260–3265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavlovic J, Schroder A, Blank A, Pitossi F, Staeheli P. Mx proteins: GTPases involved in the interferon-induced antiviral state. Ciba Found Symp. 1993;176:233–243. doi: 10.1002/9780470514450.ch15. discussion 243–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown JN, Kohler JJ, Coberley CR, Sleasman JW, Goodenow MM. HIV-1 activates macrophages independent of Toll-like receptors. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaritsky LA, Gama L, Clements JE. Canonical type I IFN signaling in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macrophages is disrupted by astrocyte-secreted CCL2. J Immunol. 2012;188:3876–3885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pulliam L, Rempel H, Sun B, Abadjian L, Calosing C, Meyerhoff DJ. A peripheral monocyte interferon phenotype in HIV infection correlates with a decrease in magnetic resonance spectroscopy metabolite concentrations. AIDS. 25:1721–1726. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328349f022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olmsted RA, Barnes AK, Yamamoto JK, Hirsch VM, Purcell RH, Johnson PR. Molecular cloning of feline immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2448–2452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olmsted RA, Hirsch VM, Purcell RH, Johnson PR. Nucleotide sequence analysis of feline immunodeficiency virus: genome organization and relationship to other lentiviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:8088–8092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talbott RL, Sparger EE, Lovelace KM, Fitch WM, Pedersen NC, Luciw PA, Elder JH. Nucleotide sequence and genomic organization of feline immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5743–5747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tompkins MB, Nelson PD, English RV, Novotney C. Early events in the immunopathogenesis of feline retrovirus infections. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991;199:1311–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torten M, Franchini M, Barlough JE, George JW, Mozes E, Lutz H, Pedersen NC. Progressive immune dysfunction in cats experimentally infected with feline immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1991;65:2225–2230. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2225-2230.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novotney C, English RV, Housman J, Davidson MG, Nasisse MP, Jeng CR, Davis WC, Tompkins MB. Lymphocyte population changes in cats naturally infected with feline immunodeficiency virus. AIDS. 1990;4:1213–1218. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolenda-Roberts H, Kuhnt H, Jennings RN, Mergia A, Gengozian N, Johnson CM. Immunopathogenesis of feline immunodeficiency virus infection in the fetal and neonatal cat. Front Biosci. 2008;12:3668–3682. doi: 10.2741/2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elder JH, Lin YC, Fink E, Grant CK. Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) as a model for study of lentivirus infections: parallels with HIV. Curr HIV Res. 2010;8:73–80. doi: 10.2174/157016210790416389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown WC, Bissey L, Logan KS, Pedersen NC, Elder JH, Collisson EW. Feline immunodeficiency virus infects both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1991;65:3359–3364. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3359-3364.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunner D, Pedersen NC. Infection of peritoneal macrophages in vitro and in vivo with feline immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1989;63:5483–5488. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5483-5488.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dow SW, Dreitz MJ, Hoover EA. Feline immunodeficiency virus neurotropism: evidence that astrocytes and microglia are the primary target cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;35:23–35. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(92)90118-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boche D, Hurtrel M, Gray F, Claessens-Maire MA, Ganiere JP, Montagnier L, Hurtrel B. Virus load and neuropathology in the FIV model. J Neurovirol. 1996;2:377–387. doi: 10.3109/13550289609146903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beebe AM, Dua N, Faith TG, Moore PF, Pedersen NC, Dandekar S. Primary stage of feline immunodeficiency virus infection: viral dissemination and cellular targets. J Virol. 1994;68:3080–3091. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3080-3091.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnston JB, Silva C, Power C. Envelope gene-mediated neurovirulence in feline immunodeficiency virus infection: induction of matrix metalloproteinases and neuronal injury. J Virol. 2002;76:2622–2633. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2622-2633.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Power C, Buist R, Johnston JB, Del Bigio MR, Ni W, Dawood MR, Peeling J. Neurovirulence in feline immunodeficiency virus-infected neonatal cats is viral strain specific and dependent on systemic immune suppression. J Virol. 1998;72:9109–9115. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9109-9115.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kenyon JC, Lever AM. The molecular biology of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) Viruses. 2011;3:2192–2213. doi: 10.3390/v3112192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maingat F, Vivithanaporn P, Zhu Y, Taylor A, Baker G, Pearson K, Power C. Neurobehavioral performance in feline immunodeficiency virus infection: integrated analysis of viral burden, neuroinflammation, and neuronal injury in cortex. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8429–8437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5818-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto JK, Hansen H, Ho EW, Morishita TY, Okuda T, Sawa TR, Nakamura RM, Pedersen NC. Epidemiologic and clinical aspects of feline immunodeficiency virus infection in cats from the continental United States and Canada and possible mode of transmission. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1989;194:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Callanan JJ, Thompson H, Toth SR, O’Neil B, Lawrence CE, Willett B, Jarrett O. Clinical and pathological findings in feline immunodeficiency virus experimental infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;35:3–13. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(92)90116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fletcher NF, Brayden DJ, Brankin B, Callanan JJ. Feline immunodeficiency virus infection: a valuable model to study HIV-1 associated encephalitis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2008;123:134–137. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fletcher NF, Meeker RB, Hudson LC, Callanan JJ. The neuropathogenesis of feline immunodeficiency virus infection: barriers to overcome. Vet J. 2011;188:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnston JB, Power C. Feline immunodeficiency virus xenoinfection: the role of chemokine receptors and envelope diversity. J Virol. 2002;76:3626–3636. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3626-3636.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.English RV, Johnson CM, Gebhard DH, Tompkins MB. In vivo lymphocyte tropism of feline immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1993;67:5175–5186. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5175-5186.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Na H, Acharjee S, Jones G, Vivithanaporn P, Noorbakhsh F, McFarlane N, Maingat F, Ballanyi K, Pardo CA, Cohen EA, Power C. Interactions between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 Vpr expression and innate immunity influence neurovirulence. Retrovirology. 2011;8:44. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu Y, Vergote D, Pardo C, Noorbakhsh F, McArthur JC, Hollenberg MD, Overall CM, Power C. CXCR3 activation by lentivirus infection suppresses neuronal autophagy: neuroprotective effects of antiretroviral therapy. FASEB J. 2009;23:2928–2941. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dube M, Roy BB, Guiot-Guillain P, Binette J, Mercier J, Chiasson A, Cohen EA. Antagonism of tetherin restriction of HIV-1 release by Vpu involves binding and sequestration of the restriction factor in a perinuclear compartment. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000856. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Acharjee S, Zhu Y, Maingat F, Pardo C, Ballanyi K, Hollenberg MD, Power C. Proteinase-activated receptor-1 mediates dorsal root ganglion neuronal degeneration in HIV/AIDS. Brain. 2011;134:3209–3221. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maingat F, Viappiani S, Zhu Y, Vivithanaporn P, Ellestad KK, Holden J, Silva C, Power C. Regulation of lentivirus neurovirulence by lipopolysaccharide conditioning: suppression of CXCL10 in the brain by IL-10. J Immunol. 2009;184:1566–1574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vivithanaporn P, Maingat F, Lin LT, Na H, Richardson CD, Agrawal B, Cohen EA, Jhamandas JH, Power C. Hepatitis C virus core protein induces neuroimmune activation and potentiates human immunodeficiency virus-1 neurotoxicity. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore RA, Warren RL, Freeman JD, Gustavsen JA, Chenard C, Friedman JM, Suttle CA, Zhao Y, Holt RA. The sensitivity of massively parallel sequencing for detecting candidate infectious agents associated with human tissue. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohtomo T, Sugamata Y, Ozaki Y, Ono K, Yoshimura Y, Kawai S, Koishihara Y, Ozaki S, Kosaka M, Hirano T, Tsuchiya M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a surface antigen preferentially overexpressed on multiple myeloma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;258:583–591. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kupzig S, Korolchuk V, Rollason R, Sugden A, Wilde A, Banting G. Bst-2/HM1.24 is a raft-associated apical membrane protein with an unusual topology. Traffic. 2003;4:694–709. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andrew AJ, Miyagi E, Kao S, Strebel K. The formation of cysteine-linked dimers of BST-2/tetherin is important for inhibition of HIV-1 virus release but not for sensitivity to Vpu. Retrovirology. 2009;6:80. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barrett BS, Smith DS, Li SX, Guo K, Hasenkrug KJ, Santiago ML. A single nucleotide polymorphism in tetherin promotes retrovirus restriction in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002596. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cocka L, Bates P. Alternatively translated isoforms of the intrinsic antiviral factor of tetherin display distinct biological activities. 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; CROI, Seattle, Washington, U. S. A. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cao W, Bover L, Cho M, Wen X, Hanabuchi S, Bao M, Rosen DB, Wang YH, Shaw JL, Du Q, Li C, Arai N, Yao Z, Lanier LL, Liu YJ. Regulation of TLR7/9 responses in plasmacytoid dendritic cells by BST2 and ILT7 receptor interaction. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1603–1614. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Marle G, Power C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genetic diversity in the nervous system: evolutionary epiphenomenon or disease determinant? J Neurovirol. 2005;11:107–128. doi: 10.1080/13550280590922838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arts JH, Muijser H, Duistermaat E, Junker K, Kuper CF. Five-day inhalation toxicity study of three types of synthetic amorphous silicas in Wistar rats and post-exposure evaluations for up to 3 months. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1856–1867. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robertson K, Liner J, Heaton R. Neuropsychological assessment of HIV-infected populations in international settings. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19:232–249. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9096-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Power C, Gill MJ, Johnson RT. Progress in clinical neurosciences: The neuropathogenesis of HIV infection: host-virus interaction and the impact of therapy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29:19–32. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100001682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Power C, Zhang K, van Marle G. Comparative neurovirulence in lentiviral infections: The roles of viral molecular diversity and select proteases. J Neurovirol. 2004;10(Suppl 1):113–117. doi: 10.1080/753312762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller C, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, MacMillan M, Huitron-Resendiz S, Henriksen S, Elder J, VandeWoude S. Strain-specific viral distribution and neuropathology of feline immunodeficiency virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2011;143:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liner KJ, 2nd, Hall CD, Robertson KR. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) subtypes on HIV-associated neurological disease. J Neurovirol. 2007;13:291–304. doi: 10.1080/13550280701422383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang K, Hawken M, Rana F, Welte FJ, Gartner S, Goldsmith MA, Power C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clade A and D neurotropism: molecular evolution, recombination, and coreceptor use. Virology. 2001;283:19–30. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuiken CL, Goudsmit J, Weiller GF, Armstrong JS, Hartman S, Portegies P, Dekker J, Cornelissen M. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V3 sequences from patients with and without AIDS dementia complex. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:175–180. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-1-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Power C, McArthur JC, Johnson RT, Griffin DE, Glass JD, Dewey R, Chesebro B. Distinct HIV-1 env sequences are associated with neurotropism and neurovirulence. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;202:89–104. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79657-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Marle G, Rourke SB, Zhang K, Silva C, Ethier J, Gill MJ, Power C. HIV dementia patients exhibit reduced viral neutralization and increased envelope sequence diversity in blood and brain. AIDS. 2002;16:1905–1914. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang K, Rana F, Silva C, Ethier J, Wehrly K, Chesebro B, Power C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope-mediated neuronal death: uncoupling of viral replication and neurotoxicity. J Virol. 2003;77:6899–6912. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6899-6912.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gandhi N, Saiyed Z, Thangavel S, Rodriguez J, Rao KV, Nair MP. Differential effects of HIV type 1 clade B and clade C Tat protein on expression of proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines by primary monocytes. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:691–699. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dunfee RL, Thomas ER, Wang J, Kunstman K, Wolinsky SM, Gabuzda D. Loss of the N-linked glycosylation site at position 386 in the HIV envelope V4 region enhances macrophage tropism and is associated with dementia. Virology. 2007;367:222–234. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dunfee RL, Thomas ER, Gorry PR, Wang J, Taylor J, Kunstman K, Wolinsky SM, Gabuzda D. The HIV Env variant N283 enhances macrophage tropism and is associated with brain infection and dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15160–15165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605513103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Power C, McArthur JC, Johnson RT, Griffin DE, Glass JD, Perryman S, Chesebro B. Demented and nondemented patients with AIDS differ in brain-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope sequences. J Virol. 1994;68:4643–4649. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4643-4649.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]