Abstract

Background

Although the transpulmonary gradient (TPG) and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) are commonly used to differentiate heart failure patients with pulmonary vascular disease from those with passive pulmonary hypertension (PH), elevations in TPG and PVR may not always reflect pre-capillary PH. Recently, it has been suggested an elevated diastolic pulmonary artery pressure to pulmonary capillary wedge pressure gradient (DPG) may be better indicator of pulmonary vascular remodeling, and therefore, may be of added prognostic value in patients with PH being considered for cardiac transplantation.

Methods

Utilizing the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database, we retrospectively reviewed all primary adult (age >17 years) orthotropic heart transplant recipients between 1998–2011. All patients with available pre-transplant hemodynamic data and PH (mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 25mmHg were included (n=16,811). We assessed the prognostic value of DPG on post-transplant survival in patients with PH and an elevated TPG and PVR.

Results

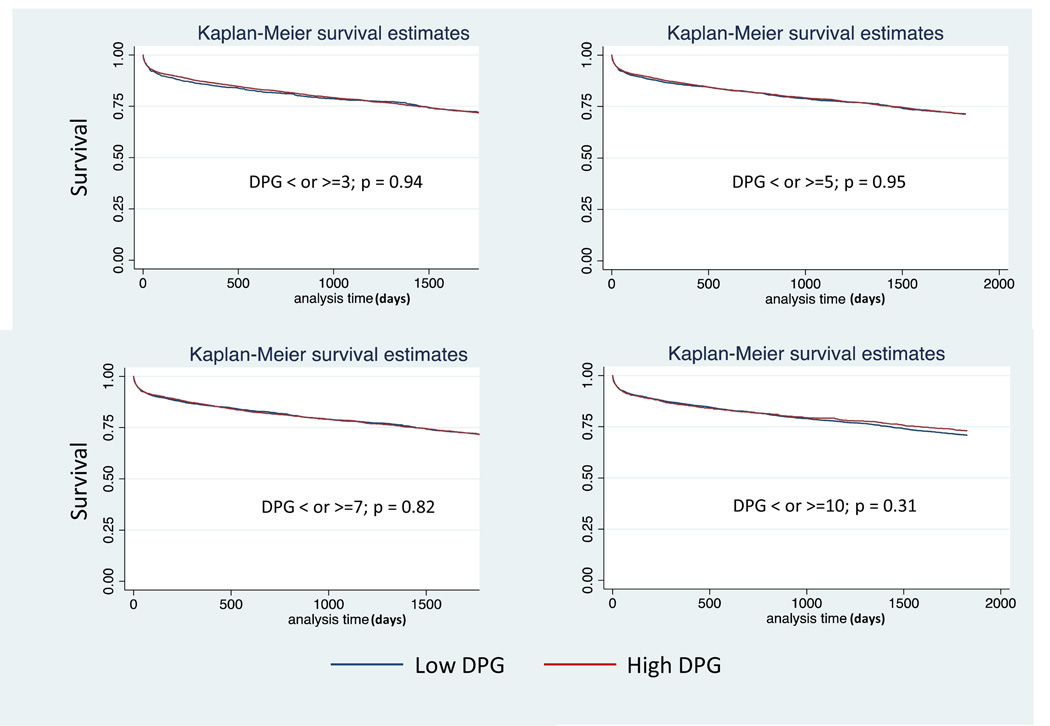

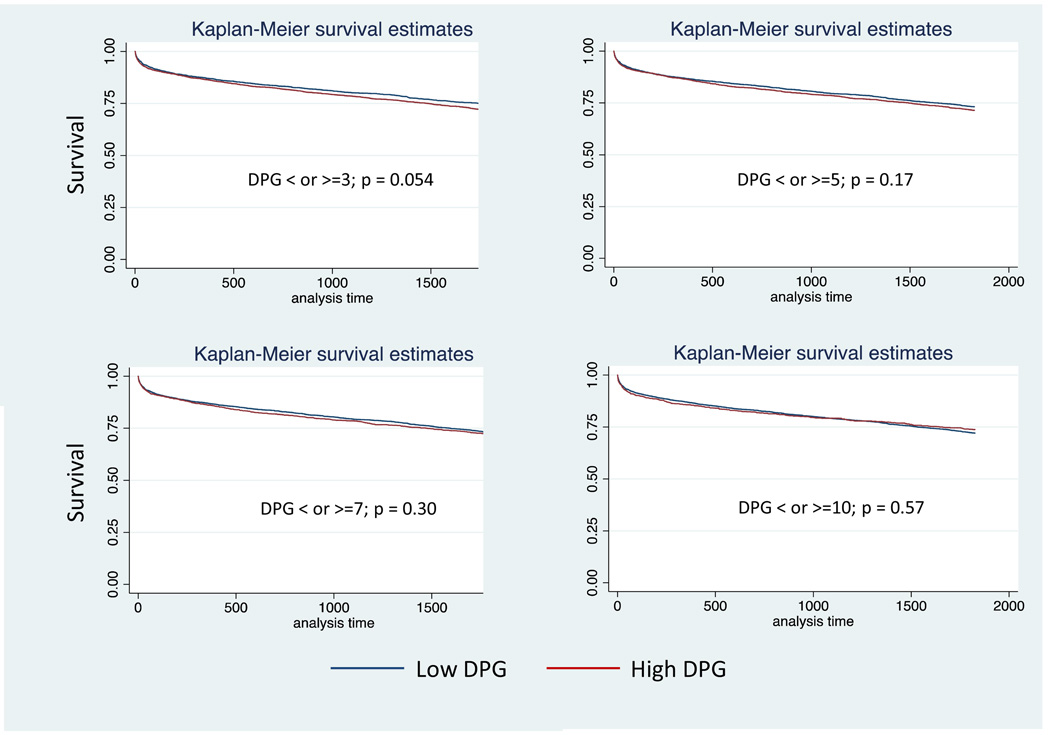

In patients with PH and a TPG > 12mmHg (n=5,827), there was no difference in survival at up to 5 years post-transplant between high (defined as ≥3, ≥5, ≥7, or ≥10mmHg) and low DPG groups (<3, <5, <7, or <10mmHg). Similarly, there was no difference in survival between high and low DPG groups in those with a PVR > 3 wood units (n=6,270). Defining an elevated TPG as > 15mmHg (n=3,065) or an elevated PVR > 5 (n=1783) yielded similar results.

Conclusions

In the largest analysis to date investigating the prognostic value of DPG, an elevated DPG had no impact on post-transplant survival in patients with PH and an elevated TPG and PVR.

Keywords: Pulmonary Hypertension, Orthotopic Heart Transplantation, Diastolic Pulmonary Vascular Pressure Gradient, UNOS, Outcomes

Introduction

Significant pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a relative contraindication to cardiac transplantation due to the risk of post-operative right heart failure.1 The transpulmonary gradient (TPG) and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) are commonly utilized by clinicians to determine the degree of pre-capillary PH and suitability of potential heart recipients.1 However, these metrics are not perfect surrogates for pulmonary vascular remodeling. In particular, the TPG varies with differences in cardiac output and left atrial pressure and neither measure clearly differentiates fixed pulmonary vascular remodeling from reversible changes in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle tone. 2–4 For this reason, acute and chronic vasodilator response is often tested to determine the reversibility of the pre-capillary PH; yet, even when reversibility is demonstrated, post-transplant mortality remains higher than that seen in patients without PH.5 Because of these limitations, a metric to better differentiate high and low risk among patients with PH is needed. There has been growing interest in using the diastolic pulmonary gradient (DPG, diastolic pulmonary artery pressure minus pulmonary capillary wedge pressure) as a means to identify those left heart failure patients with clinically significant pre-capillary PH.4,6 A recent analysis of patients with left heart disease and PH suggested that a TPG > 12mmHg and DPG ≥ 7mmHg was associated with worse survival compared to a TPG > 12 mmHg and DPG < 7.6 Our purpose was to use the United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) database to explore whether differences in DPG define high and low risk subpopulations among patients with PH being considered for orthotopic heart transplant (OHT).

Methods

Data Source

UNOS provided Standard Transplant Analysis and Research (STAR) files with donor-specific data from December 1988 to June 2011. The data set included prospectively collected metrics from all patients who received thoracic transplantation in the United States. The current study was granted an exemption by the institutional review board at the Johns Hopkins because none of the investigators had access to datasets containing protected health information.

Study Design

We retrospectively examined all primary, adult (>17 years) OHT patients (1988 to 2011) with a complete set of pre-transplant hemodynamic data, which at minimum included systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP), diastolic pulmonary artery pressure (dPAP), mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), and cardiac output (CO). Only patients with PH (defined as mPAP ≥ 25mmHg) were included in the analysis. Patients with multi-organ transplants and re-do transplants were excluded. Outcomes of interest included survival at 30 days, one and five years.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared via Student’s t-test (parametric) or Wilcoxon rank-sum test (non-parametric) as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared with chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed for DPG, TPG, and PVR to assess their utility in discriminating survivors from non-survivors post-transplant. Total area under the curve (AUC) was considered to assess the value of these measures. ROC cutpoints were defined using the Youden’s index. Survival was estimated by the Kaplan Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. A P-value (two-tailed) of < 0.05 was considered significant. Means are presented with standard deviations. Because the cause of death was not available, a sensitivity analysis was performed to ascertain the impact of cause of death on our findings. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12.1 software (StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Cohort Statistics

From December 1988 to June 2011, 43,494 patients > 17 years old underwent primary OHT. After excluding 18,041 patients without complete hemodynamic data and 8,642 patients without PH (mPAP <25mmHg), the final study cohort consisted of 16,811 patients.

ROC Curve analyses

When considering all patients with PH (mPAP ≥ 25mmHg), DPG, TPG, and PVR all had poor ability to discriminate survivors from non-survivors as evidenced by the AUC values near 0.5(Table 1). The optimal cut points for DPG in those patients with PH and an elevated TPG, PVR, or both were determined (Table 2). DPG did not discriminate survivors from non-survivors significantly better than chance in any of these groups at any of the three time points (p>0.05 for all).

Table 1.

All patients with mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 25mmHg

| Area Under Curve (AUC) |

|

|---|---|

| DPG | |

| 30 day survival | 0.52 |

| 1 year survival | 0.51 |

| 5 year survival | 0.52 |

| TPG | |

| 30 day survival | 0.54 |

| 1 year survival | 0.52 |

| 5 year survival | 0.52 |

| PVR | |

| 30 day survival | 0.53 |

| 1 year survival | 0.52 |

| 5 year | 0.51 |

Table 2.

All patients with mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 25mmHg

| Pre-Capillary Pulmonary Hypertension Parameter |

DPG Cut Point |

Area Under Curve AUC) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPG > 12 mmHg | |||

| 30 day survival | 11.5 | 0.50 | 0.89 |

| 1 year survival | 1.2 | 0.51 | 0.77 |

| 5 year survival | 8.5 | 0.50 | 0.90 |

| TPG > 15 mmHg | |||

| 30 day survival | 5.9 | 0.50 | 0.98 |

| 1 year survival | 10.1 | 0.50 | 0.91 |

| 5 year survival | 8.5 | 0.51 | 0.70 |

| PVR > 3 Wood units | |||

| 30 day survival | 2.9 | 0.52 | 0.25 |

| 1 year survival | 6 | 0.51 | 0.54 |

| 5 year survival | 2.9 | 0.51 | 0.64 |

| PVR > 5 Wood units | |||

| 30 day survival | 8.5 | 0.52 | 0.69 |

| 1 year survival | 4 | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| 5 year survival | 8.5 | 0.52 | 0.57 |

| TPG > 12 mmHg And PVR > 3 Wood units | |||

| 30 day survival | 11.5 | 0.50 | 0.94 |

| 1 year survival | 1.70 | 0.50 | 0.97 |

| 5 year survival | 8.5 | 0.50 | 0.73 |

| TPG > 15 mmHg And PVR > 5 Wood units | |||

| 30 day survival | 8.5 | 0.51 | 0.77 |

| 1 year survival | 14 | 0.50 | 0.94 |

| 5 year survival | 8.5 | 0.51 | 0.67 |

Pulmonary Hypertension with an Elevated TPG

Demographic, acuity, and hemodynamic data for patients with PH and a TPG > 12mmHg in strata of DPG (n=5,827) are presented in Table 3. Given the variable ROC cut points for DPG in our analyses as well as various cut points proposed in the literature, we explored four cut points for DPG chosen a priori: 3 mmHg, 5mmHg, 7 mmHg, and 10mmHg. Compared with the lower DPG groups (defined as < 3, <5, <7, or <10mmHg), higher DPG groups (as ≥3, ≥5, ≥7, or ≥10mmHg) were younger and were more likely to be of black race, have a diagnosis of idiopathic cardiomyopathy, and have a ventricular assist device. The lower DPG groups were more likely to have an ischemic cardiomyopathy and carry a diagnosis of diabetes. There were no differences in terms of gender, creatinine, bilirubin, ventilator support, or cardiac output. PCWP and pulmonary pulse pressure were higher in the lower DPG groups than the higher DPG groups. TPG and PVR were higher in the high DPG groups. Thirty-day, 1 year, and 5 year post-transplant survival was similar between low DPG and high DPG groups, p>0.05 for all (Table 4, Figure 1). Defining an elevated TPG as > 15 mmHg (n=3,065) had no affect on the ability of the DPG cutoffs to predict survival at any time point (Table 4).

Table 3.

Transpulmonary Gradient > 12 mmHg

| DPG < 3 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 3 mmHg |

P value |

DPG < 5 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 5 mmHg |

P value |

DPG < 7 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 7 mmHg |

P value |

DPG < 10 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 10 mmHg |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (N) | 1605 | 4222 | 2506 | 3321 | 3542 | 2285 | 4679 | 1148 | ||||

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age (years) | 53.9±10.7 | 52.6±11.0 | <0.001 | 53.8±10.7 | 52.3±11.0 | <0.001 | 53.6±10.7 | 52.0±11.2 | <0.001 | 53.3±10.8 | 51.7±11.2 | <0.001 |

| Female | 23.2% | 22.7% | 0.68 | 23.4% | 22.5% | 0.39 | 23.6% | 21.8% | 0.11 | 23.0% | 22.3% | 0.60 |

| White | 73.6% | 69.9% | 0.006 | 72.0% | 70.1% | 0.10 | 72.6% | 68.2% | <0.001 | 71.7% | 67.8% | 0.009 |

| Black | 16.1% | 20.9% | <0.001 | 17.7% | 21.0% | 0.001 | 17.7% | 22.5% | <0.001 | 18.9% | 22.3% | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7±5.0 | 26.5±5.5 | 0.33 | 26.5±5.9 | 26.5±5.0 | 0.88 | 26.6±5.6 | 26.5±5.0 | 0.50 | 26.6±5.5 | 26.2±5.2 | 0.022 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Idiopathic | 35.1% | 44.4% | 38.0% | 44.8% | 39.7% | 45.2% | 41.1% | 45.2% | ||||

| Ischemic | 54.1% | 46.3% | 52.0% | 45.8% | 50.4% | 45.5% | 49.4% | 45.0% | ||||

| Congenital | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.5% | ||||

| Other | 9.1% | 8.0% | <0.001 | 8.6% | 8.0% | <0.001 | 8.5% | 7.9% | 0.001 | 8.3% | 8.4% | 0.06 |

| Acuity | ||||||||||||

| Diabetes | 426/1502 | 991/3954 | 0.01 | 650/2342 | 767/3114 | 0.009 | 903/3318 | 514/2138 | 0.009 | 1169/4382 | 248/1074 | 0.02 |

| Isch. Time (hrs) | 3.1±1.0 | 3.0±1.0 | 0.03 | 3.1±1.0 | 3.0±1.1 | 0.047 | 3.1±1.0 | 3.0±1.0 | 0.02 | 3.1±1.0 | 3.0±1.0 | 0.12 |

| Creat. (mg/dL) | 1.5±1.7 | 1.4±1.5 | 0.55 | 1.5±1.6 | 1.5±1.5 | 0.94 | 1.5±1.5 | 1.5±1.6 | 0.94 | 1.5±1.6 | 1.5±1.2 | 0.98 |

| Bili. (mg/dL) | 1.5±3.8 | 1.3±2.7 | 0.06 | 1.5±3.8 | 1.3±2.3 | 0.06 | 1.4±3.5 | 1.3±2.2 | 0.25 | 1.4±3.2 | 1.3±2.7 | 0.71 |

| IABP | 5.7% | 6.1% | 0.55 | 5.4% | 6.4% | 0.08 | 5.4% | 6.9% | 0.20 | 5.6% | 7.6% | 0.01 |

| Assist Device | 11.7% | 14.0% | 0.02 | 11.7% | 14.5% | 0.002 | 12.3% | 14.8% | 0.006 | 13.1% | 14.2% | 0.33 |

| Ventilation | 2.5% | 2.3% | 0.74 | 2.6% | 2.3% | 0.46 | 2.4% | 2.4% | 0.93 | 2.4% | 2.3% | 0.77 |

| Hemodynamics | ||||||||||||

| SPAP (mmHg) | 60.9±12.6 | 55.4±12.8 | <0.001 | 59.1±12.2 | 55.2±13.3 | <0.001 | 57.8±12.2 | 55.4±14.0 | <0.001 | 56.9±12.4 | 56.9±15.2 | 0.85 |

| DPAP (mmHg) | 25.1±7.5 | 28.7±8.1 | <0.001 | 25.4±7.3 | 29.4±8.3 | <0.001 | 26.0±7.3 | 30.3±8.6 | <0.001 | 26.5±7.4 | 32.5±9.3 | <0.001 |

| mPAP (mmHg | 40.9±8.1 | 38.6±9.0 | <0.001 | 39.8±8.1 | 38.8±9.2 | <0.001 | 39.3±8.1 | 39.2±9.7 | 0.64 | 38.9±8.3 | 40.8±10.4 | <0.001 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 25.7±7.4 | 20.7±7.7 | <0.001 | 24.6±7.4 | 20.1±7.8 | <0.001 | 23.8±7.4 | 19.3±7.9 | <0.001 | 22.9±7.5 | 18.4±8.4 | <0.001 |

| C. O. (L/min) | 4.38±1.5 | 4.35±1.5 | 0.54 | 4.3±1.6 | 4.4±1.5 | 0.47 | 4.4±1.5 | 4.4±1.5 | 0.94 | 4.4±1.5 | 4.3±1.5 | 0.11 |

| PVR (Woods) | 3.91±1.9 | 4.73±2.9 | <0.001 | 4.0±2.2 | 4.9±2.9 | <0.001 | 4.0±2.1 | 5.2±3.2 | <0.001 | 4.1±2.2 | 6.0±3.6 | <0.001 |

| TPG (mmHg) | 15.2±3.0 | 17.9±5.5 | <0.001 | 15.3±2.9 | 18.6±5.9 | <0.001 | 15.5±2.9 | 19.8±6.5 | <0.001 | 15.9±3.3 | 22.3±7.4 | <0.001 |

Mean ± Standard Deviation; BMI = Body Mass Index, Isch = Ischemic, Creat = Creatinine, Bili = Bilirubin, IABP = Intra-aortic Balloon Pump, SPAP = Systolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure, DPAP = Diastolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure, mPAP = Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure, PCWP = Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure, C.O. = Cardiac Output, PVR = Pulmonary Vascular Resistance, TPG = Transpulmonary Gradient

Table 4.

Survival (Kaplan Meier Analysis) in all patients with mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 25mmHg

| Survival | Survival | Survival | Survival | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPG < 3 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 3 mmHg |

P value |

DPG < 5 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 5 mmHg |

P value |

DPG < 7 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 7 mmHg |

P value |

DPG < 10 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 10 mmHg |

P value |

|

| TPG > 12 mmHg | ||||||||||||

| 30 day | 93.4% | 93.2% | 0.89 | 93.4% | 93.2% | 0.95 | 93.3% | 93.1% | 0.89 | 93.3% | 93.0% | 0.70 |

| 1 year | 84.3% | 85.7% | 0.21 | 84.9% | 85.6% | 0.41 | 85.2% | 85.4% | 0.76 | 85.4% | 85.0% | 0.65 |

| 5 year | 71.2% | 70.8% | 0.94 | 71.2% | 70.8% | 0.95 | 71.2% | 70.5% | 0.82 | 70.5% | 72.5% | 0.31 |

| TPG > 15 mmHg | ||||||||||||

| 30 day | 93.1% | 93.0% | 0.66 | 93.7% | 92.8% | 0.29 | 93.1% | 93.0% | 0.64 | 93.0% | 93.0% | 0.84 |

| 1 year | 85.3% | 85.4% | 0.90 | 85.2% | 85.5% | 0.87 | 85.5% | 85.4% | 0.81 | 85.4% | 85.4% | 0.83 |

| 5 year | 72.3% | 71.4% | 0.66 | 71.4% | 71.6% | 0.83 | 71.8% | 71.4% | 0.82 | 70.7% | 73.3% | 0.27 |

| PVR > 3 WU | ||||||||||||

| 30 day | 94.5% | 93.1% | 0.09 | 94.1% | 93.1% | 0.20 | 93.9% | 93.1% | 0.39 | 93.8% | 92.7% | 0.22 |

| 1 year | 86.4% | 85.6% | 0.44 | 86.1% | 85.6% | 0.66 | 86.2% | 85.2% | 0.44 | 86.1% | 84.9% | 0.31 |

| 5 year | 73.6% | 70.9% | 0.054 | 72.9% | 70.9% | 0.17 | 72.4% | 70.9% | 0.30 | 71.7% | 73.2% | 0.57 |

| PVR > 5 WU | ||||||||||||

| 30 day a | 93.1% | 93.0% | 0.58 | 92.7% | 93.2% | 0.50 | 92.6% | 93.4% | 0.31 | 92.9% | 93.2% | 0.65 |

| 1 year | 82.7% | 85.6% | 0.15 | 83.3% | 85.9% | 0.15 | 83.6% | 86.3% | 0.10 | 84.4% | 86.1% | 0.34 |

| 5 year | 71.0% | 72.9% | 0.36 | 71.9% | 72.7% | 0.56 | 71.0% | 73.8% | 0.15 | 70.7% | 75.9% | 0.04 |

| TPG > 12 mmHg & PVR > 3 WU | ||||||||||||

| 30 day | 93.4% | 92.9% | 0.97 | 93.2% | 92.9% | 0.97 | 93.1% | 93.0% | 0.88 | 93.1% | 92.7% | 0.73 |

| 1 year | 84.9% | 85.4% | 0.63 | 85.0% | 85.4% | 0.59 | 85.3% | 85.2% | 0.92 | 85.3% | 85.1% | 0.81 |

| 5 year | 72.0% | 71.2% | 0.80 | 71.6% | 71.3% | 0.95 | 71.6% | 71.1% | 0.90 | 70.8% | 73.2% | 0.24 |

| TPG > 15 mmHg & PVR > 5 WU | ||||||||||||

| 30 day | 91.3% | 93.1% | 0.49 | 92.7% | 92.9% | 0.93 | 92.7% | 92.9% | 0.94 | 92.6% | 93.1% | 0.81 |

| 1 year | 82.9% | 85.9% | 0.34 | 84.1% | 85.9% | 0.54 | 85.1% | 85.7% | 0.84 | 85.1% | 85.9% | 0.75 |

| 5 year | 69.3% | 74.0% | 0.25 | 70.7% | 74.1% | 0.30 | 71.9% | 74.1% | 0.47 | 71.4% | 75.7% | 0.15 |

DPG = Diastolic pulmonary artery pressure to pulmonary capillary wedge pressure gradient; TPG = Transpulmonary gradient; PVR = Pulmonary vascular resistance; WU = Wood units

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier Plots for Diastolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure to Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure Gradient (DPG) in patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) and an elevated transpulmonary gradient > 12mmHg: a) 3mmHg, b) 5 mmHg, c) 7 mmHg, d) 10 mmHg.

Pulmonary Hypertension with an Elevated PVR

Demographic, acuity, and hemodynamic data for patients with a PVR > 3 wood units and PH (n=6,270) are presented in (Table 5). Compared with the lower DPG groups, higher DPG groups were on average younger, male predominant, and were more likely to be of black race. PCWP, pulmonary pulse pressure, TPG, PVR, and cardiac output were lower in the low DPG groups than the high DPG groups. Similar to the TPG analysis, there was no difference in survival at up to 5 years post transplant in the low vs. high DPG groups, p >0.05 for all (Table 4, Figure 2). Defining an elevated PVR as > 5 wood units (n=1783) had no affect on the ability of DPG to predict post-transplant survival (Table 4).

Table 5.

Pulmonary Vascular Resistance > 3 Wood units

| DPG < 3 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 3 mmHg |

P value |

DPG < 5 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 5 mmHg |

P value |

DPG < 7 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 7 mmHg |

P value |

DPG < 10 mmHg |

DPG ≥ 10 mmHg |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (N) | 2439 | 3831 | 3391 | 2879 | 4287 | 1983 | 5227 | 1043 | ||||

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age (years) | 52.9±11.5 | 52.2±11.4 | 0.02 | 52.8±11.5 | 52.1±11.3 | 0.01 | 52.8±11.5 | 51.9±11.3 | 0.01 | 52.6±11.5 | 51.9±11.2 | 0.05 |

| Female | 29.2% | 26.5% | 0.02 | 29.3% | 25.4% | 0.001 | 29.0% | 24.4% | <0.001 | 28.2% | 24.2% | 0.008 |

| White | 70.6% | 68.1% | 0.03 | 69.5% | 68.7% | 0.51 | 70.0% | 67.2% | 0.03 | 69.5% | 66.9% | 0.10 |

| Black | 18.6% | 21.5% | 0.005 | 19.2% | 21.7% | 0.015 | 19.2% | 22.8% | 0.001 | 19.9% | 22.5% | 0.06 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4±5.6 | 25.8±5.5 | 0.001 | 25.4±6.1 | 25.9±4.8 | <0.001 | 25.5±5.8 | 26.0±4.9 | <0.001 | 25.6±5.7 | 25.8±4.9 | 0.26 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Idiopathic | 42.4% | 46.3% | 43.7% | 46.1% | 44.3% | 45.8% | 44.8% | 44.9% | ||||

| Ischemic | 45.4% | 43.7% | 44.8% | 43.9% | 44.4% | 44.4% | 44.4% | 44.6% | ||||

| Congenital | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.2% | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.7% | ||||

| Other | 11.0% | 8.6% | 0.001 | 10.3% | 8.5% | 0.03 | 10.1% | 8.1% | 0.048 | 9.6% | 8.8% | 0.60 |

| Acuity | ||||||||||||

| Diabetes | 495/2287 | 810/3588 | 0.40 | 683/3179 | 622/2696 | 0.15 | 881/4022 | 424/1853 | 0.40 | 1082/4899 | 223/976 | 0.60 |

| Isch. Time (hrs) | 3.1±1.0 | 3.0±1.0 | 0.36 | 3.1±1.0 | 3.0±1.0 | 0.08 | 3.1±1.0 | 3.0±1.0 | 0.03 | 3.1±1.0 | 3.0±1.0 | 0.19 |

| Creat. (mg/dL) | 1.4±1.0 | 1.4±1.5 | 0.09 | 1.36±1.2 | 1.44±1.5 | 0.04 | 1.4±1.2 | 1.4±1.6 | 0.08 | 1.4±1.4 | 1.5±1.2 | 0.15 |

| Bili. (mg/dL) | 1.5±3.6 | 1.4±2.5 | 0.02 | 1.5±3.3 | 1.4±2.5 | 0.06 | 1.5±3.2 | 1.3±2.4 | 0.11 | 1.4±3.0 | 1.3±2.8 | 0.30 |

| I ABP | 5.0% | 6.5% | 0.02 | 5.1% | 6.8% | 0.004 | 5.3% | 7.2% | 0.004 | 5.5% | 7.9% | 0.003 |

| Assist Device | 10.9% | 12.5% | 0.06 | 10.9% | 13.0% | 0.009 | 11.3% | 13.0% | 0.06 | 11.7% | 12.9% | 0.28 |

| Ventilation | 1.9% | 2.7% | 0.06 | 2.2% | 2.5% | 0.45 | 2.3% | 2.6% | 0.39 | 2.4% | 2.4% | 0.96 |

| Hemodynamics | ||||||||||||

| SPAP (mmHg) | 58.0±12.2 | 56.0±12.9 | <0.001 | 57.1±12.0 | 56.4±13.4 | 0.03 | 56.7±12.0 | 56.9±14.1 | 0.59 | 56.5±12.1 | 58.2±15.2 | <0.001 |

| DPAP (mmHg) | 26.3±7.0 | 29.7±8.0 | <0.001 | 26.6±6.9 | 30.5±8.3 | <0.001 | 27.0±6.9 | 31.3±8.7 | <0.001 | 27.4±7.1 | 33.1±9.5 | <0.001 |

| mPAP (mmHg) | 39.8±7.8 | 39.4±8.8 | 0.05 | 39.3±7.8 | 39.8±9.2 | 0.01 | 39.2±7.8 | 40.3±9.7 | <0.001 | 39.1±8.0 | 41.6±10.3 | <0.001 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 27.2±7.1 | 21.7±7.7 | <0.001 | 26.3±7.1 | 21.0±7.9 | <0.001 | 25.6±7.2 | 20.1±8.1 | <0.001 | 24.9±7.4 | 18.8±8.6 | <0.001 |

| C. O. (L/min) | 3.1±0.9 | 3.7±1.1 | <0.001 | 3.2±0.9 | 3.8±1.1 | <0.001 | 3.3±0.9 | 3.9±1.1 | <0.001 | 3.4±1.0 | 4.0±1.2 | <0.001 |

| PVR (Woods) | 4.2±1.5 | 5.2±2.9 | <0.001 | 4.3±1.9 | 5.4±3.0 | <0.001 | 4.3±1.8 | 5.7±3.3 | <0.001 | 4.5±2.0 | 6.4±3.8 | <0.001 |

| TPG (mmHg) | 12.6±3.8 | 17.7±6.1 | <0.001 | 13.0±3.8 | 18.8±6.4 | <0.001 | 13.6±3.9 | 20.3±6.8 | <0.001 | 14.3±4.3 | 22.8±7.6 | <0.001 |

Mean ± Standard Deviation; BMI = Body Mass Index, Isch = Ischemic, Creat = Creatinine, Bili = Bilirubin, IABP = Intra-aortic Balloon Pump, SPAP = Systolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure, DPAP = Diastolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure, mPAP = Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure, PCWP = Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure, C.O. = Cardiac Output, PVR = Pulmonary Vascular Resistance, TPG = Transpulmonary Gradient

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier Plots for Diastolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure to Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure Gradient (DPG) in patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) and an elevated pulmonary vascular resistance > 3 Wood units: a) 3mmHg, b) 5 mmHg, c) 7 mmHg, d) 10 mmHg.

Pulmonary Hypertension with an Elevated TPG and Elevated PVR

In patients with a TPG > 12mmHg and PVR > 3 wood units (n=4419) as well as those with a TPG > 15mmHg and PVR > 5 wood units (n=1290), there was no difference in survival between low and high DPG groups at up to 5 years post transplant (Table 4).

Discussion

In cardiac transplant candidates with pulmonary hypertension, determining the non-reversible component is vital for proper patient selection and good outcomes. Recent studies have suggested the diastolic pulmonary artery pressure to pulmonary capillary wedge pressure gradient may be useful in this regard4,6, but this has not been confirmed by large, multicenter studies. Using the UNOS database, we show that the DPG does not meaningfully delineate risk among patients with elevated TPG and PVR undergoing orthotopic heart transplant.

An elevated TPG or PVR does not always reflect irreversible pulmonary vascular disease. In left heart failure, the TPG can be elevated as a result of pulmonary vascular remodeling but also due to the effects of elevated left sided filling pressures. As pressures in the left atrium increase, this pressure is passively transmitted back to the pulmonary vasculature resulting in elevation of the diastolic pulmonary artery pressure. This increased venous pressure also leads to more vascular stiffness (or lower vascular compliance) than one would predict based on the pulmonary vascular resistance alone.3 The lower compliance leads to enhanced pulmonary arterial wave reflections which result in an increased systolic pulmonary artery pressure, and therefore mean pulmonary artery pressure. This occurs without an increase in diastolic pulmonary pressure, thereby raising the TPG. PVR is subject to the same effects because TPG is in the numerator of its calculation. Both parameters may also be affected by cardiac output as elegantly described by Naeije and colleagues.4

Given known limitations of TPG and PVR measurements, the DPG would appear an attractive alternative since dPAP is presumably not affected by the above mechanisms. However, other factors must be considered. First, from a technical measurement standpoint, the dPAP is particularly prone to the effects of both catheter whip and catheter ‘ringing’ when using fluid-filled catheters.7 Even a small error in the measured dPAP may lead to a significant change in the DPG. The use of high fidelity catheters could eliminate or reduce this error, yet these are not commonly used in clinical practice. Using computer generated mean values for hemodynamic measurements (averaged over the entire respiratory cycle) rather than manually determined end-expiration values may lead to inaccuracies, especially in situations of marked respiratory excursion.8 Incomplete catheter wedging may lead to an overestimation of PCWP and therefore a falsely low DPG. While these types of error may also affect the TPG and PVR, the relative effects on DPG may be more profound. Additionally, and most importantly, it is known that the DPG can change acutely in situations such as sepsis9,10, after bypass surgery11, acute respiratory distress syndrome12,13, acidosis2, and hypoxia2,14. The mechanism behind an elevated DPG in sepsis remains uncertain, but theories include microthrombi15, effects of endogenous prostaglandins16, acidosis2, and/or serotonin release.12 Utilizing intracardiac pacing, Enson et al. demonstrated that increases in heart rate alone lead to an increase in DPG.17 This later phenomenon may be particularly relevant to the heart failure population where tachycardia is common, compensating for a low cardiac output or as a result of inotropic medications.

Gerges and colleagues recently reported that a DPG ≥ 7 mmHg in heart failure patients with an elevated TPG was associated with worse long term prognosis compared to those with a DPG <7 mmHg.6 These findings may simply suggest that elevated DPG identifies a sicker patient population as evidenced by their faster heart rates, higher pulmonary pressures, and overall worse hemodynamic profiles compared to the lower DPG group. Once patients have resolution of their left heart failure (i.e. through cardiac transplantation), many of these ‘reversible’ factors that may elevate the DPG are no longer present.

There are several limitations of this retrospective study that merit discussion. First, data on vasodilator testing prior to transplant was not available in the UNOS database, and thus, the reversibility of PH in patients with significant PH is not known. It is likely that some patients who did not demonstrate reversibility were excluded as transplant candidates and are therefore not included in this database. These excluded patients may have had an elevated DPG. However, the large numbers of patients with an elevated DPG in this database help to lessen this potential impact. Similarly, post-transplant hemodynamic data was not available, preventing us from determining if the DPG normalized after transplantation or if those with persistently elevated DPG had worse outcomes. Goland et al. have shown that failure to normalize PVR to < 3 wood units after transplantation (i.e, those with truly fixed pulmonary hypertension) is a risk factor for long term survival.18 In our analysis, pre-transplant DPG did not discriminate long term (5 year) survival. The cause of death was not available in post-transplant patients and not all patients died as a consequence of PH and right heart failure. Therefore, it remains possible that the low DPG groups died of different causes (i.e. rejection or infection) than the high DPG group (i.e. right heart failure), diluting the true ability of DPG to discriminate right heart failure death in our mixed population. However, by selectively analyzing groups of patients at highest risk of right heart failure (i.e. PVR>3, PVR >5, TPG>12, TPG >15) we should have enriched the proportion of deaths from right heart failure. Furthermore, given the large number of patients within each group, we should have had ample power to detect even small differences introduced through dilution of a hypothesized narrow relationship between right heart failure and DPG (illustrated in sensitivity analysis in the online supplement). The fact that we still did not detect any such significant difference in mortality along a gradient of DPG minimizes the impact of this limitation on our results.

It is also possible that factors that affect the DPG (i.e. heart rate, sepsis, hypoxia, etc) could have a confounding influence on the DPG to discriminate survivors from non-survivors. Importantly, these factors that may alter DPG are not routinely considered (in part because their relative impact on DPG is not known) by clinicians when reporting pre-transplant hemodynamics. Therefore, the analysis is similar to the real world practice in which the measured DPG is taken as “true DPG”. Additionally, acuity data was relatively similar in low and high DPG groups. Finally, in order to address the many cut-points already described in the literature, we performed many analyses. The multiple significance tests performed in our work increased the chance that we would see a “significant” association by chance alone. The fact that we saw no such association despite this propensity may further support the poor ability of DPG to discriminate survivors from non-survivors when applied broadly to a pre-transplant population.

In conclusion, in this large population of heart failure patients with evidence of pre-capillary PH (elevated TPG and PVR) undergoing cardiac transplantation, the diastolic pulmonary gradient did not predict post-transplant survival. Coupled with our previous knowledge that factors other than pulmonary vascular remodeling may contribute to an elevated DPG, the findings of this study urge caution before DPG is routinely incorporated into pre-transplant or PH-related clinical decision making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Funding Sources

The authors wish to acknowledge funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grants: 1R01HL114910-01 and L30 HL110304].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report related to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Mehra MR, Kobashigawa J, Starling R, et al. Listing criteria for heart transplantation: International society for heart and lung transplantation guidelines for the care of cardiac transplant Candidates—2006. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2006;25(9):1024–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey RM, Enson Y, Ferrer MI. A reconsideration of the origins of pulmonary hypertension. CHEST Journal. 1971;59(1):82–94. doi: 10.1378/chest.59.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tedford RJ, Hassoun PM, Mathai SC, et al. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure augments right ventricular pulsatile loading / clinical perspective. Circulation. 2012;125(2):289–297. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.051540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naeije R, Vachiery J, Yerly P, Vanderpool R. The transpulmonary pressure gradient for the diagnosis of pulmonary vascular disease. European Respiratory Journal. 2013;41(1):217–223. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00074312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler J, Stankewicz MA, Wu J, et al. Pre-transplant reversible pulmonary hypertension predicts higher risk for mortality after cardiac transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2005;24(2):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerges C, Gerges M, Lang MB, et al. Diastolic pulmonary vascular pressure gradient: A predictor of prognosis in “out-of-proportion” pulmonary hypertension. CHEST Journal. 2013;143(3):758–766. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemmings HC, Hopkins PM, editors. Foundations of anaesthesia: Basic sciences for clinical practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan JJ, Rich JD, Thiruvoipati T, Swamy R, Kim GH, Rich S. Current practice for determining pulmonary capillary wedge pressure predisposes to serious errors in the classification of patients with pulmonary hypertension. Am Heart J. 2012;163(4):589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sibbald WJ, Paterson NA, Holliday RL, Anderson RA, Lobb TR, Duff JH. Pulmonary hypertension in sepsis: Measurement by the pulmonary arterial diastolic-pulmonary wedge pressure gradient and the influence of passive and active factors. CHEST Journal. 1978;73(5):583–591. doi: 10.1378/chest.73.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marland AM, Glauser FL. Significance of the pulmonary artery diastolic-pulmonary wedge pressure gradient in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1982;10:658–661. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinonen J, Salmenpera M, Takkunen O. Increased pulmonary artery diastolic-pulmonary wedge pressure gradient after cardiopulmonary bypass. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1985;32:165–170. doi: 10.1007/BF03010044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sibbald W, Peters S, Lindsay R. Serotonin and pulmonary hypertension in human septic ARDS. Crit Care Med. 1980;8:490. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198009000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Her C, Mandy S, Bairamian M. Increased pulmonary venous resistance contributes to increased pulmonary artery diastolic-pulmonary wedge pressure gradient in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2005;102(3):574–580. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200503000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Her C, Cerabona T, Baek S, Shin S. Increased pulmonary venous resistance in morbidly obese patients without daytime hypoxia: Clinical utility of the pulmonary artery catheter. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(3) doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e4f706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein M, Thomas DP. Role of platelets in the acute pulmonary responses to endotoxin. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1967;23(1):47–52. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.23.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeves JT, Daoud FS, Estridge M. Pulmonary hypertension caused by minute amounts of endotoxin in calves. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1972;33(6):739–743. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.33.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enson Y, Wood JA, Mantaras NB, Harvey RM. The influence of heart rate on pulmonary arterial-left ventricular pressure relationships at end-diastole. Circulation. 1977;56(4):533–539. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goland S, Czer LSC, Kass RM, et al. Pre-existing pulmonary hypertension in patients with end-stage heart failure: Impact on clinical outcome and hemodynamic follow-up after orthotopic heart transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2007;26(4):312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.