Abstract

A spectrum of radiation-induced non-targeted effects has been reported during the last two decades since Nagasawa and Little first described a phenomenon in cultured cells that was later called the “bystander effect”. These non-targeted effects include radiotherapy-related abscopal effects, where changes in organs or tissues occur distant from the irradiated region. The spectrum of non-targeted effects continue to broaden over time and now embrace many types of exogenous and endogenous stressors that induce a systemic genotoxic response including a widely studied tumor microenvironment. Here we discuss processes and factors leading to DNA damage induction in non-targeted cells and tissues and highlight similarities in the regulation of systemic effects caused by different stressors.

1. Introduction

According to classical radiobiology dogma, the majority of cytotoxic and genotoxic cellular effects of ionizing radiation (IR) is attributed to radiation-induced DNA damage. Investigation of stress responses caused by IR has led to discoveries of important cellular mechanisms operating to process the inflicted damage, such as repair of DNA damage, cell cycle arrest and cell death. However, relatively recently it has been realized that IR also produces effects in non-targeted cells which include DNA damage, such as isolated and complex oxidative DNA lesions, including double-strand breaks (DSBs), that eventually result in gene and protein expression changes, sister chromatid exchanges, mutations, increased micronuclei, genomic instability, tumorigenesis, cell survival and cell death [1]. These non-targeted effects have been investigated under a variety of conditions and has been the subject of a number of reviews [2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10; 11]. Under specific contexts these non-targeted effects have been designated as bystander effects, abscopal effects, cohort effects and adaptive effects [2]. Although the mechanisms behind this phenomenon are still the subject of debate and investigation, the involvement of oxidative and inflammatory response is considered pivotal. In addition, recent evidence indicates that tumors growing in vivo elicit a similar stress response, with induction of DNA damage in distant tissues, through similar mechanisms [12], therefore, supporting an idea for a ‘unifying model’ between the different types of stress; in this case, IR and tumor growth [12]. This review will focus on non-targeted cells/tissue responses caused by different types of stress agents with emphasis on similarities of the effects and mechanisms between IR and the presence of a tumor growing in an organism.

2. Radiation-induced non-targeted effects

In the last two decades, an increasing amount of research has used IR as a tool to investigate non-targeted effects, because damage can be localised in space and time, however, when interpreting non-targeted effects, scattered radiation, albeit at low doses, needs to be considered. Cell culture-based in vitro systems initially were utilized that provided some intriguing results that have increased our understanding about the effects of radiation. Now, we can start to apply this knowledge towards the in vivo situation, with the additional complexities such as microenvironment, immune responses and other systemic signalling.

2.1. Radiation-induced bystander effect (RIBE)

The term bystander effect has been used in different contexts and a detailed discussion of this can be found in Blyth et al. [2]. Essentially, these are non-targeted effects in a region usually proximal but outside the directly targeted region. The classic paper of Nagasawa and Little was first to provide formal evidence for the in vitro RIBE where upon irradiation of 1% of cells in a culture with α-particles, an astounding 30% of the cells showed an increase in sister chromatid exchanges [13]. Several years later, Mothersill and Seymour applied conditioned medium transfer methods providing evidence that a soluble factor secreted into the medium was responsible for the RIBE [14; 15]. Soon after, it was identified that gap junctions could mediate intercellular communication to convey a bystander signal between an irradiated cell and a non-targeted adjacent cell [16; 17]. Since then, a variety of cell culture experiments have been conducted exploring many aspects of the non-targeted effects in a variety of cellular contexts to further the knowledge in this area of research. Some of the conditions investigated include different energies, radiation quality, linear energy transfer (LET), cell type, species, dose, fields, times of procedure (including time after radiation and medium exposure times), single cell, multicellular and in vivo models, targeted regions, medium transfers, single cell and subcellular targeting (for reviews see [2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10]). An interesting aspect of the RIBE is that it has been reported to have a low threshold dose (<1 Gy) and then is largely dose-independent, and therefore does not follow the linear no-threshold model [18; 19; 20; 21].

Experiments using microbeams that can target single cells contributed significantly to understanding the RIBE (reviewed in [8; 22]). Zhou et al. investigated mutation frequency in cells irradiated with a lethal dose of -particles, concluding that since all targeted cells would die, an increase in mutation level compared to unirradiated controls would indicate a bystander effect. They found more than a 3-fold increase in mutation frequency [23]. A few years later, Ponnaiya et al. were able to directly visualize the bystander effect using a two color cell system and an endpoint of micronuclei [24]. Sokolov et al. employed a similar system and reported that H2AX foci induction is delayed in bystander cells compared to irradiated cells [25]. Taking cell culture experiments one step further, several groups have utilized a 3D reconstructed human skin culture sytem for which microbeam irradiation of a single vertical plane induced bystander effect evident at a distance of 1 mm away from targeted cells [26] and found induction of DNA damage, apoptosis, micronucleus formation, DNA hypomethylation, and senescence arrest in bystander cells [27]. An overview of microbeam experiments in tissue models of bystander effects can be found in [28].

2.2. Adaptive response

The term adaptive response refers to the general situation where a priming exposure to an agent protects from a future exposure that would otherwise be more detrimental. Early examples of radioadaptive response described cells exposed to low levels of radiation, and subsequently became less susceptible to chromosomal aberrations, micronucleus formation and malignant transformation, when later exposed to higher dose [29; 30]. The radioadaptive response has only been observed with low doses of radiation (<0.5Gy) and affected mutation rate and survival [29; 31] (and references therein), as well as the kinetics and numbers of -H2AX foci formation in cell cultures [1]. Protective and beneficial effects of conditioning low dose irradiation have been reported in animal studies [32; 33]. Matsumoto et al. have proposed a model for the radioadaptive response where nitric oxide (NO) appears to be a key molecule linking bystander and adaptive responses which may involve a NO induced specific p53-phosphorylation signature pattern for activation [31; 34]. It has also been suggested that low dose-induced DNA damage sensitizes cells to enhance repair of subsequent DNA lesions [35; 36; 37].

Interestingly, radiation-induced adaptive responses can be achieved by exposure of unirradiated cells to factors derived from other cell cultures treated with low radiation doses [38], akin to the RIBE.

2.3. Abscopal effect

It has been known for decades that local radiation can trigger complex systemic tissue responses outside the irradiated field, and that radiation dose and tissue type influence such responses [39; 40]. The irradiation of the primary tumor was reported in several instances to enhance or suppress the growth of primary and secondary tumors [41; 42]. These non-targeted long range effects, or abscopal effects, occur at a distance from the site of irradiation or other localized stress in an organism, in unirradiated tissue or organs [43]. Abscopal effects are particularly important for human health and are proposed to be mediated by immune system activation and cytokines [39; 44; 45]. There are documented examples where radiotherapy has led to regression of a tumor outside the zone of irradiation [3; 44; 46] such as in the case when palliative radiotherapy of bone metastases resulted in regression of a hepatocarcinoma [47] (See detailed case review by Siva et al. submitted to this issue of Cancer Letters).

On the other hand, increased rates of secondary malignancies have been associated with radiation induced abscopal effects. An epidemiological study investigated association of secondary malignancies in prostate cancer patients during the ten years after radiotherapy and found that these patients have a detectable increase in secondary malignancies in regions distant from the site of irradiation [48]. In some cases, these secondary malignancies could be attributed to other factors, such as pre-existence of micrometastasis, intrinsic radiosensitivity [49], or shedding of viable tumor cells from irradiated tumors [50; 51]. However, tumor- and/or treatment-induced oxidative stress and consequent genomic instability and secondary carcinogenesis could also contribute to second cancers.

Early animal studies showed that plasma from irradiated animals contained clastogenic factors since exposure of unirradiated cells to such plasma led to an increase in chromosomal aberrations [52; 53; 54; 55]. Numerous animal studies describing abscopal effects after localized radiation have followed. Camphausen et al. controlled growth of primary tumor and lung metastases by irradiating mice bearing a Lewis lung carcinoma [56; 57]. Partial lung irradiation in mice led to abscopal DNA damage in regions of the lung that were not irradiated, and this effect was inhibited by antioxidants indicating that reactive oxygen species (ROS) and NO were causative [58; 59; 60]. Another study utilizing a rat model has demonstrated that the levels of cytokines and macrophages were elevated in the non-targeted regions of the lung, and were similar to those of the in-field tissue [61]. More recently, Mancuso et al. have utilized a radiosensitive tumor-susceptible Patched-1 mouse model to study the abscopal effect in vivo [62; 63]. An increase in double strand breaks and apoptosis in bystander cerebellum of the neonatal mice, and an increase in cerebellar medulablastoma formation outside the field of irradiation were identified [63]. Using a specific gap junction inhibitor, they also determined that gap junctions played a role in this model of distant non-targeted effects [62; 63]. Koturbash et al. found increased DNA damage, altered cellular proliferation and apoptosis, and increased p53 in spleens in mice when only the head was irradiated [64]. A recent study has investigated the abscopal effect utilizing a clonogenic reporter cells after explant conditioned medium exposure as an endpoint for conventional broad beam as well as spatially fractionated radiation in the form of microbeam radiotherapy, and found that both these radiation modalities convey an abscopal effect [65].

3. Potential mechanisms in the mediation of non-targeted effects: In vitro to in vivo

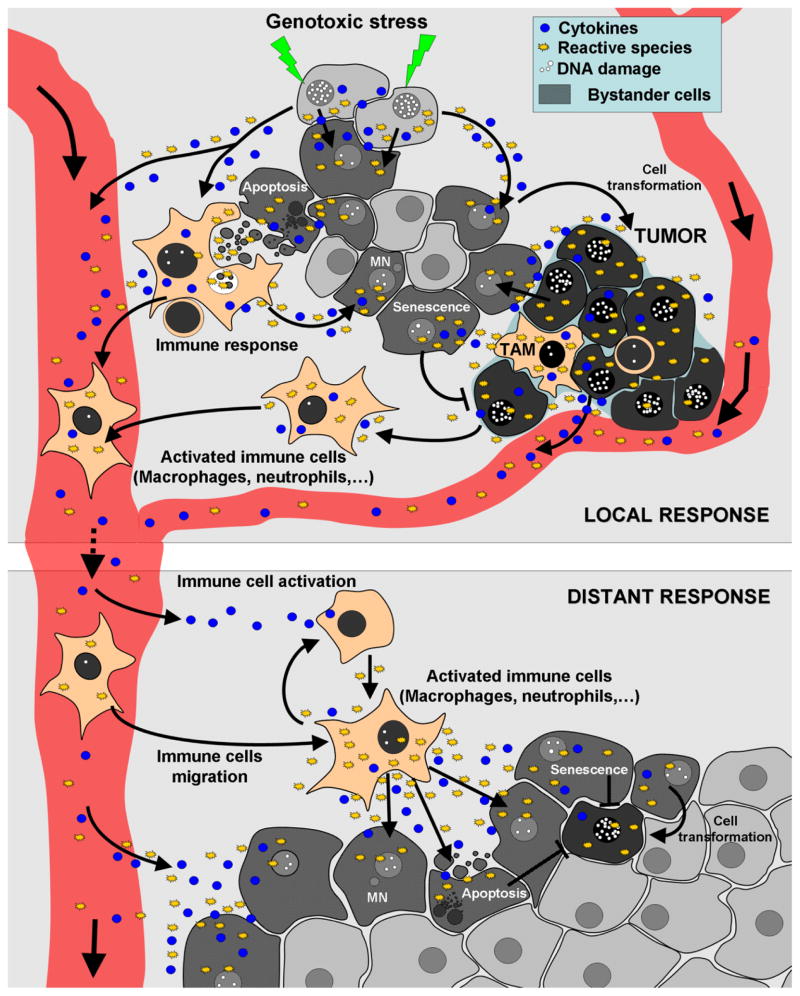

There appear to be several main independent mechanisms involved in radiation induced non-targeted effects: 1) Direct cell to cell communication between irradiated and unirradiated cells, through gap junctions, 2) Factors secreted by the irradiated cells into the surroundings which could directly affect more distant cells, and 3) Immune responses, including factors secreted by activated macrophages (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Exposure to genotoxic stress and the presence of a tumor lead to similar responses that affect both adjacent and distant tissues.

Both genotoxic stress such as ionizing radiation, ultraviolet radiation, cancer drugs or the presence of a tumor can lead to the production of cytokines and reactive species such as ROS, RNS and NO, which can disseminate into surrounding cells via diffusion or gap junctions, leading to alterations in cell metabolism (changes in protein and miRNA expression) and DNA damage. In turn, persistent DNA damage can lead to genomic instability (mutations, chromosome aberrations, micronuclei), senescence, or ultimately to cell transformation. These types of local responses can persistently produce an inflammatory response. Both activated immune cells (such as macrophages and neutrophils) and long-lived reactive species can circulate to distant tissues and produce additional cytokines and reactive species to further activate macrophages and/or other immune cells to produce DNA damage, apoptosis, micronuclei, senescence, cell transformation, etc. in distant tissues. TAM: Tumor-associated macrophage, MN: Micronucleus.

A comprehensive identification of the factors involved in the non-targeted mechanism is an intensive ongoing area of research spurred on by recent advances in the identification of some molecular players that clearly have key roles in non-targeted responses.

In this section we will discuss major mediators involved in transmission of the non-targeted effects, including reactive radical species, cytokines, and macrophages.

3.1. Reactive radical species

Radiation can directly produce ROS, mostly in the form of short-lived hydroxyl radicals, that can cause DNA damage if generated within a couple of nanometers from the DNA strand. The question is how DNA damage is conferred to non-targeted ‘distant’ sites? Early biochemical evidence for radiation-induced non-targeted effects in vitro was the contribution of persistent oxidative stress to genomic instability (Clutten et al. 1996). Other investigators found ROS in non-targeted cells where it was reported that plasma membrane-bound NADPH-oxidase was primarily responsible for the non-targeted intracellular ROS [66]. Mitochondria, the location of the COX2 gene (MT-COX2), are potent generators of free radicals such as NO, and have been shown to be important in non-targeted effects. This was shown when reduced bystander effect was observed in cells deficient in mitochondria [67], or in cells having critical mutations in mitochondrial DNA [68].

It has been demonstrated that the addition of antioxidants leads to less DNA damage in non-targeted cells [69; 70; 71]. Shao et al. showed that the levels of NO increased in 40% of cells when only 1% of cells were directly targeted with helium ions [72]. They further went on to show that this bystander response was inhibited when a NO specific scavenger was added to the culture medium. The same group found that non-targeted effects were eliminated by treating with a calcium channel blocker, indicating that calcium fluxes modulated NO bystander effects [73]. They went on to show that inhibition of NO synthase led to the inhibition of calcium fluxes, suggesting that NO and ROS were involved in the non-targeted response. Sokolov et al. and Dickey et al. demonstrated that treatment of cell cultures with an NO scavenger and an NO synthase inhibitor reduces the level of DNA double-strand breaks in bystander cells [25; 71]. NO causes DNA damage such as base damage which can lead to mutations or single strand breaks as a result of endonuclease activities during processing of the damaged bases [74]. If left unrepaired until DNA replication, these single strand breaks can form DNA double-strand breaks [75].

3.2. Cytokines and activation of proinflammatory pathways

Cytokines are soluble polypeptides which play a crucial role in cell signalling during inflammation, creating a link between non-targeted responses and inflammatory pathways. Their production can be constitutively activated or induced. They can either act in a paracrine manner through cell-cell communication effecting nearby cells or in autocrine manner effecting distant cells. The cytokines match specific cell surface receptor activated pathways which, in turn, induce intracellular signalling cascades affecting targeted cellular functions.

In vitro studies revealed that a number of cytokines and growth factors such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF ), IL-1, PDGF, FGF are released by different cell types in response to IR [76; 77; 78; 79]. NF-κB mediates an increase in levels of multifunctional cytokine IL-6 secreted by fibroblasts after IR treatment [80]. In the context of in vivo radiobiological studies, the cytokines in tissue and serum potentially mediate radiation-induced acute and late adverse responses [81; 82; 83; 84]. Studies by Lorimore et al. provided evidence that inflammatory tissue processes that are initially induced by IR require a functional p53 activity to produce cytokines that can induce apoptosis in a p53-independent manner [85].

Furthermore, extracellular signalling by cytokines and growth factors (microenvironment) such as TGFβ1 triggers a multicellular damage response aimed at the prevention of cancer by eliminating abnormal cells and inhibiting neoplastic behaviour [86; 87]. TGFβ1 plays a key role in fibrosis development, via stimulation of fibroblast proliferation and differentiation, synthesis and secretion of extracellular matrix (ECM). This follows the inflammatory stage where the TNF is produced by activated macrophages.

TGFβ1 has also been implicated as a mediator of non-targeted effects. It is known to be induced by IR [88] and by NO [89]. TGFβ has been shown to increase the amount of ROS and micronuclei, and inhibitors of TGFβ can reduce non-targeted effects [71]. In vitro assays have shown that TGFβ1 induces DNA damage to levels similar to those induced by medium conditioned on irradiated cells [71]. Also, TGF-β1 was found to mimic bystander effects by induction of DNA damage in cell populations lacking DNA synthesis [90]. In addition, a recent report has shown that TGFβ1 and TGFβ receptors expression levels are elevated in non-targeted tissues after irradiation [91].

Other cytokines shown to have potential influence on non-targeted effects include IL-6, Il-8, CCL2, CCL4, CCL7, CXCL7 and TNFα [12; 71; 92; 93]. Hei et al. have proposed a mechanism that brings together many of the molecules that are thought to be involved in the signalling of non-target effects [4]. This model provides that various cytokines such as TGFβ, IL-8, IL-1, and TNFα induce NFκB, JNK, ERK or p38 signalling pathways to induce cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX2), which ultimately stimulates NO production [4].

Along the same lines, Zhou et al. have identified that COX2 signalling, which includes downstream MAPK signalling pathway is important in non-targeted effects [94]. COX2 has a critical role in inflammatory response, i.e. production of cytokines and free radicals which can potentially occur in surrounding cells through gap junctions or by diffusion into the medium.

3.3. Macrophages

One aspect of inflammation, including inflammatory responses that occur after IR, is that macrophages are activated and secrete cytokines that cause non-targeted effects [95; 96; 97] (Figure 1). These effects are proposed to not be a response to direct irradiation of the macrophages, but rather as a result of the macrophage phagocytosis of radiation-induced apoptotic cells [97; 98]. Macrophages that consume dead tumor cells may behave in a similar way [99]. TNFα is secreted from macrophages and can produce non-targeted effects such as DNA damage [100; 101]. Lorimore et al. found that NO and ROS are important since inhibitors of these free radicals led to fewer nonclonally derived aberrations [96]. Later the same group identified that COX2 was involved [95; 97; 102]. This fits in well with the in vitro data that the Hei group have proposed with COX2 having a central role in the non-targeted effects [4].

Investigations conducted in the Wright laboratory have identified chromosomal instability in non-targeted hematopoietic cells when exposed to medium from irradiated macrophages [96]. Further, they also demonstrated that after in vivo irradiation, apoptotic clearance produced macrophage activation and inflammatory responses [103], and that irradiated bone marrow can produce an ongoing apoptotic response [95]. This provides an explanation for the persistent inflammation and subsequent DNA damage in non-targeted tissues distant from the irradiated site.

Rastogi et al. have shown that in vivo non-targeted effects are mediated by long-lived inflammatory signalling [102] that involve a complex cross-talk between macrophages [104]. It is possible for released cytokines to travel from irradiated regions or regions containing tumors to distant regions of the body. However, it is also possible for cytokine-expressing cells, such as macrophages that have engulfed apoptotic cells (either as a result of irradiation or tumor) [105], to move from that region to a distant region of the body and then release factors that can induce DNA damage (Figure 1). The movement of DNA damaging factors via macrophages would deliver a significantly increased concentration of signal compared to circulating cytokines from distant sites but would also be specific to regions where the macrophages are likely to travel (e.g., gut, spleen, skin, lymph nodes, sites of other infections). Another way to induce oxidative damage in non-targeted tissues is that cytokines produced by immune cells at the irradiated site would travel and activate resident macrophages present in the distant tissues (Figure 1). Induced macrophages (M1) produce pro-inflammatory molecules such as COX2, NOS, IL6, TNF alpha, superoxide, ROS and NO [104; 106]. Release of these molecules at distant sites could lead to oxidative DNA damage in the cells to produce the observed abscopal effect seen after irradiation or due to the presence of a distant tumor.

Also, it was found that ROS are critical for differentiation of macrophages into the alternative M2 activated macrophages, which the phenotype is similar to tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which promote tumorigenesis resulting from their proangiogenic and immune-suppressive functions [107].

3.4. Other mechanisms proposed to be involved in the non-targeted effects

Oxidized extracellular DNA including that DNA released from apoptotic cells has also been suggested to be a non-targeted signal [108]. Also, epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and miRNA expression have been shown to be significantly regulated by both direct and indirect radiation in rodent models and humans [109; 110; 111; 112]. miRNA signalling did not appear to propagate stress communication to neighbouring cells and tissues directly, but was found to play important roles in the later cellular response to radiation-induced damage [109; 113; 114]. Recently, there have even been suggestions that weak acoustic or electromagnetic signals may be involved to explain inter-individual non-targeted effects in fish models [115].

3. 5. Genomic evidence of IR-induced bystander signalling

Genomics studies have also been used to identify transcription dynamics in cells both directly exposed to IR and in non-targeted cells [116; 117; 118; 119; 120; 121]. Ghandi et al. completed whole genome analysis on human lung fibroblasts that were irradiated or subjected to irradiated conditioned medium [118] with micronuclei assessment in bystander cells as an endpoint. They found that p53-regulated genes were mainly induced in cultures that were directly irradiated, while genes regulated by NFκB, such as COX2 (PTGS2) and IL-8 responded similarly between the two treated groups. Rzeszowska-Wolny et al. and Herok et al. irradiated erythroleukemia or melanoma cells and exposed unirradiated cells to conditioned medium derived from irradiated cultures, and confirmed a non-targeted effect with apoptosis and micronuclei as endpoints. They reported that majority of the gene expression change between direct and indirect exposure was similar, however, the expression kinetics for some genes were different, and may provide clues to different responses between these treatments in tumor cells [119; 122]. Also, microarray analysis has identified the up-regulation of gene transcription in bystander cells receiving medium from irradiated cells belonging to the functional classifications of extracellular signalling, cell communication, and growth factors and receptors [121].

4. Non-targeted effects caused by other stress sources

IR clearly induces a variety of effects on non-targeted cells, but there are other examples where other stress sources also cause these types of effects [86]. Dickey et al. addressed this question by testing stressors including UV-A in BrdU sensitized cells, UV-C, and presence in culture of tumor cells and senescent cells [71]. From medium transfer experiments, they found that all these conditions resulted in DNA damage in naive cells. Also various chemical reagents have induced non-targeted effects including mitomycin C [123; 124], phleomycin [124], chloroethylnitrosurea [125], and actinomycin D [126].

The persistence of DNA damage in senescent cells was shown to initiate the increased secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 [71; 127]. This cytokine response required DDR proteins ATM, NBS1 and CHK2 rather than cell-cycle arrest enforcers, p53 and pRb. ATM was shown to be essential for IL-6 secretion resulting from oncogene-induced senescence and by damaged cells that bypass senescence [127]. Therefore, senescent cells are also able to induce genomic instability in their neighbours by establishing a chronic inflammatory environment by secreting a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [128; 129]. Medium conditioned on senescent cells contains high levels of IL1, IL6 and TGFβ1, capable of inducing ROS mediated DNA damage response, which in turn cause senescence in normal bystander cells via activation of multiple signalling pathways such as JAK/STAT, TGFβ/SMAD and IL1/NFκB, causing expression of NAPDH oxidase [130].

Tumors are well known to interact with the microenvironment. Tumors send signals to the local tissue and also receive signals in a process necessary for tumor survival. The chronic inflammation might play a role in determining metastases spread by creating a more susceptible environment. This is achieved by stimulating normal fibroblasts in potential metastatic sites to produce proteins that bind cells to the ECM followed by subsequent activation of resident fibroblasts and macrophages [131; 132; 133]. Tumors secrete ROS, including long-lived hydrogen peroxide [134], various growth factors and cytokines [135], which in turn promote mesenchymal cell activation leading to inflammation and potential DNA damage through reactive radicals [136]. DNA and protein damage has been shown to increase in normal tissues and cells bordering tumors [137; 138], such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [139; 140]. Production of ROS in CAFs induces a feedback bystander effect on adjacent cancer cells, leading to increased DNA damage, genomic instability and aneuploidy, suggesting that tumors and stroma are metabolically coupled and that oxidative stress may be “contagious” [139; 141].

4.1. Tumor-induced distant non-targeted effects

Tumor presence affects surrounding tissues [135], but also influence tissues distant from a tumor (Figure 1). Gerashchenko et al. found that there was a tumour growth dependent erythropoetic cytotoxicity [142].

In an alternative and phenomenologically independent experimental setup compared to all previous setups used for the study of radiation-induced non-targeted effects, Redon et al. investigated if the presence of a non-metastatic tumor growing in vivo in mice could induce DNA damage at distant sites [12]. Specifically, they implanted three types of syngeneic tumors in two strains of mice and assessed DNA damage, a known end-point in non-targeted cells, in a variety of tissues, both adjacent to and distant to the tumor. They found that DNA damage, as assessed by γH2AX and non-DSB clustered DNA lesions, was elevated in normal tissues in a tissue-specific manner. Highly proliferative tissue distant from the tumor site, which included skin and the gastrointestinal tract, were the most affected. Interestingly, liver was not affected, which was attributed to the presence of high antioxidant levels present in this organ. Also, DNA damage was not found in the kidney, a site where few mature macrophages are present. Elevated levels of macrophages were identified in affected tissues along with elevated levels of some cytokines [143; 144]. As previously mentioned, macrophages are a major source of COX2 and produce reactive radical species. Therefore, these results show an analogous mechanism to that found for in vivo abscopal effects from IR. Both tumor-induced and radiation-induced abscopal effects involve the activation of macrophages and the induction of DNA damage likely mediated through cytokines involved in signalling pathways such as NFκB. NFκB regulates the expression of COX2 which can induce prostaglandins and NO, both associated with inflammation and the chronic production of DNA damaging radicals perpetuating this process.

Sixty-four proteins were examined in blood serum of control and tumor-bearing mice; the levels of four were substantially elevated, CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL4 (MIP-1), CCL7 (MCP-3), and CXCL10 (IP-10). These factors are involved in activating and attracting monocytes to sites of tissue damage or activating tissue-resident macrophages [145]. Furthermore, CCL2 knock-out mice resulted in no DNA damage above basal levels highlighting the importance of CCL2 in this abscopal effect [12; 143; 144].

4.2. CCL2/MCP1

Because of the results described above, our group has a particular interest in the monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), or chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2). It is a member of the C-C chemokine cytokine family. It plays a crucial role in activation and migration of leukocytes by binding the CCR2 and CCR4 receptors (members of the G protein-coupled receptor family). It recruits monocytes, memory T-cells and dendritic cells to the inflammation sites [146; 147]. CCL2 inflammatory chemokine signalling pathway has been shown to be important in regulating macrophage recruitment during inflammation and wound healing processes [148; 149]. It also attracts monocytes, lymphocytes, NK cells, and immature dendritic cells to sites of injury [150]. CCL2 and IL-8 mediate the accumulation of neutrophil granulocytes and mononuclear cells in the irradiated lung tissues, as well as in the course of other inflammatory reactions [151]. It is involved in pathogenesis of immunological diseases accompanied by monocytic infiltrates, such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis [152].

Treatment of basophils and mast cells with CCL2 causes them to release the content of their granules into the intercellular space. This effect is enhanced by a pre-treatment with IL-3 among other cytokines [153; 154]. CCL2 is expressed by different cell types, including osteoclasts, neurons, astrocytes, microglia, muscle cells, and tumor cells [155; 156]. Among others, it targets cellular pathways dependent on phophoinositide 3-kinase and protein kinase C. CCL2-mediated receptor activation leads to elevated levels of major players in bystander signalling and carcinogenesis including COX2 and TGFβ1 [157; 158]. Thus, CCL2 is essential in the tumour-induced genotoxic response in vivo, and it has been reported that it also plays an important role in mediating IR response. The levels of CCL2 increase in irradiated tissues and cells after 2–9 Gy irradiation or in serum after fractionated low-dose radiation exposure in a dose-dependent manner [159; 160]. CCL2 increase in serum after low-dose radiation has been associated with excess risk of cardiovascular disease [161]. CCL2 may be an equally important mediating factor in both tumor-induced and radiation-induced non-targeted effects. Animal studies of non-targeted normal tissue response after localized irradiation will answer the question if CCL2 would represent a potential “risk marker” for radiotherapy planning.

5. Stress-induced inflammation leads to DNA damage formation in non-targeted cells

Inflammatory cytokine and free radical release as a consequence of IR is well-documented and discussed above. COX2, one of the main targets in bystander signalling has been shown to induce DNA damage [162; 163]. CCL2 has been shown to act synergistically with CD40L on COX2 expression [164], and high levels of CCL2 have been shown to stimulate COX2 expression in macrophages [165]. Therefore, the upregulation of COX2 as part of bystander signalling [43; 94], and in tumours [166], directly links the proinflammatory responses acting in bystander and tumorigenesis to DNA damage induction in distant tissues.

Oncogenic changes in the organism also induce a variety of stresses including replication, oxidative, and inflammation stress [167]. In many instances, deregulation of cell cycle control and over-expression of replication factors like Cdc6 has been shown to induce replication stress and an associated oxidatively induced DNA damage in affected cells [168]. In addition, clinical data suggests that chronic inflammation promotes carcinogenesis (reviewed in [169; 170; 171]). For example, patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) have a 5–7-fold increased risk of developing colorectal cancer with approximately 43% of patients with ulcerative colitis expected to develop colorectal cancer after 25 to 35 years [172]. Similarly, the lung disease mesothelioma, which is caused by exposure to asbestos, has been directly linked to asbestos-induced chronic inflammation, and subsequent production of ROS and DNA damage [173].

High levels of oxidative DNA damage and inflammation have been detected in a variety of cancers like breast lung, liver [138], and in also in viral-induced carcinogenesis like in the case of hepatitis B- and C-associated hepatocellular carcinoma cancer [174]. Chronic infection with hepatitis B or C viruses or ingestion of aflatoxin that causes ROS and subsequent DNA damage production leads to hepatocellular carcinoma and is considered as a significant cause of cancer-associated mortality [174]. Oxidative DNA damage may be involved in the development of breast cancer as well. Increased steady-state levels of DNA damage and ROS have been reported in invasive ductal carcinoma as well as in several other cases of malignancies [175]. In most cases, the role of inflammatory response in the induction of oxidative stress, ROS/RNS generations and DNA damage is considered a major contributing factor. As also discussed above, a variety of inflammatory signalling molecules carry pre-oxidative or oxidative potential and have the ability to generate a local or dispersed form of redox imbalance in tissues or organs. Although this potentially catastrophic stress is being used by the organism as an inherent response to homeostasis loss due to, for example, uncontrolled cell proliferation, it carries many side effects such as the induction of oxidatively-induced DNA lesions like a variety of oxidized bases, abasic sites and/or single strand breaks. All these ‘harmless’ DNA lesions can be converted to a DSB with the well known deleterious effects.

Lately, the role of the tumour microenvironment (stroma) is being increasingly appreciated as being a critical part of the pathway to transformation and malignancy. Inflammatory cells are an important component of the stroma and this milieu fosters proliferation, survival, and migration signalling [167]. It is suggested that chronic inflammation promotes the development of blood vessels and the remodelling of the ECM creating the ‘perfect’ environment in which a mutation-bearing normal cell can become malignant. In addition, immune cells like macrophages, as discussed above, or neutrophils, produce ROS via a plasma membrane bound nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) [138]. The oxygen radicals are generated for cell killing and bactericidal activities as part of the normal immune response and surveillance but persistent inflammation or injury can lead to carcinogenesis [167]. Therefore, inflammation can indirectly result in a variety of non-targeted effects. These suggested ‘centers of high inflammatory response’ (CHIR) can, in turn, play the role of signalling propagation to other irrelevant and distant regions in the body, therefore, creating a cascade of uncontrolled CHIR and non-targeted effects. This unifying model for the induction of non-targeted effects can be applied to radiation and tumor growth of other agents inducing a high level of homeostasis loss (Figure 1).

Conclusions

Both irradiation and tumor microenvironment affect “naïve” cells and tissues via a locally-induced inflammatory response, i.e., secretion of a variety of cytokines and free radicals. These inflammatory factors, either directly or indirectly, via immune cells, induce oxidative DNA damage into the environment. Therefore, monitoring DNA damage as an early end-point, enables the understanding of the underlying mechanisms of non-targeted effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pavel Lobachevsky and Roger Martin for critical reading of the manuscript. This project was supported through the National Institute of Health (grant 5U19AI067773-07) and the 2010 round of the priority-driven Collaborative Cancer Research Scheme (grant 1002743) and funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing with the assistance of Cancer Australia. Also, this work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (grant 10275598) and the Australian National Breast Cancer Foundation (grant PG-08-06; http://www.nbcf.org.au/). Support was also provided by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program and A. Georgakilas’s funding is from EU grant MC-CIG-303514 and COST ACTION CM1202 ‘Biomimetic Radical Chemistry’. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dieriks B, De Vos W, Baatout S, Van Oostveldt P. Repeated exposure of human fibroblasts to ionizing radiation reveals an adaptive response that is not mediated by interleukin-6 or TGF-beta. Mutat Res. 2011;715:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blyth BJ, Sykes PJ. Radiation-induced bystander effects: what are they, and how relevant are they to human radiation exposures? Radiat Res. 2011;176:139–157. doi: 10.1667/rr2548.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancuso M, Pasquali E, Giardullo P, Leonardi S, Tanori M, Di Majo V, Pazzaglia S, Saran A. The radiation bystander effect and its potential implications for human health. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:613–624. doi: 10.2174/156652412800620011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hei TK, Zhou H, Ivanov VN, Hong M, Lieberman HB, Brenner DJ, Amundson SA, Geard CR. Mechanism of radiation-induced bystander effects: a unifying model. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:943–950. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.8.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadhim M, Salomaa S, Wright E, Hildebrandt G, Belyakov OV, Prise KM, Little MP. Non-targeted effects of ionising radiation-Implications for low dose risk. Mutat Res. 2013;752:84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjostedt S, Bezak E. Non-targeted effects of ionising radiation and radiotherapy. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 2010;33:219–231. doi: 10.1007/s13246-010-0030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyer R, Lehnert BE. Effects of ionizing radiation in targeted and non-targeted cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;376:14–25. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prise KM, Schettino G. Microbeams in radiation biology: review and critical comparison. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2011;143:335–339. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncq388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan WF. Is there a common mechanism underlying genomic instability, bystander effects and other non-targeted effects of exposure to ionizing radiation? Oncogene. 2003;22:7094–7099. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMahon SJ, Butterworth KT, Trainor C, McGarry CK, O’Sullivan JM, Schettino G, Hounsell AR, Prise KM. A kinetic-based model of radiation-induced intercellular signalling. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prise KM, Folkard M, Kuosaite V, Tartier L, Zyuzikov N, Shao C. What role for DNA damage and repair in the bystander response? Mutat Res. 2006;597:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura AJ, Kareva IG, Naf D, Nowsheen S, Kryston TB, Bonner WM, Georgakilas AG, Sedelnikova OA. Tumors induce complex DNA damage in distant proliferative tissues in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17992–17997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008260107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagasawa H, Little JB. Induction of sister chromatid exchanges by extremely low doses of alpha-particles. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6394–6396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mothersill C, Seymour C. Medium from irradiated human epithelial cells but not human fibroblasts reduces the clonogenic survival of unirradiated cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 1997;71:421–427. doi: 10.1080/095530097144030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mothersill C, Seymour CB. Cell-cell contact during gamma irradiation is not required to induce a bystander effect in normal human keratinocytes: evidence for release during irradiation of a signal controlling survival into the medium. Radiat Res. 1998;149:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Gooding T, Little JB. Intercellular communication is involved in the bystander regulation of gene expression in human cells exposed to very low fluences of alpha particles. Radiat Res. 1998;150:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Little JB. Direct evidence for the participation of gap junction-mediated intercellular communication in the transmission of damage signals from alpha - particle irradiated to nonirradiated cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:473–478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011417098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shao C, Furusawa Y, Kobayashi Y, Funayama T, Wada S. Bystander effect induced by counted high-LET particles in confluent human fibroblasts: a mechanistic study. FASEB J. 2003;17:1422–1427. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1115com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belyakov OV, Malcolmson AM, Folkard M, Prise KM, Michael BD. Direct evidence for a bystander effect of ionizing radiation in primary human fibroblasts. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:674–679. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu B, Wu L, Han W, Zhang L, Chen S, Xu A, Hei TK, Yu Z. The time and spatial effects of bystander response in mammalian cells induced by low dose radiation. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:245–251. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smilenov LB, Hall EJ, Bonner WM, Sedelnikova OA. A microbeam study of DNA double-strand breaks in bystander primary human fibroblasts. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2006;122:256–259. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncl461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prise KM, Schettino G, Vojnovic B, Belyakov O, Shao C. Microbeam studies of the bystander response. J Radiat Res. 2009;50(Suppl A):A1–6. doi: 10.1269/jrr.09012s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou H, Randers-Pehrson G, Waldren CA, Vannais D, Hall EJ, Hei TK. Induction of a bystander mutagenic effect of alpha particles in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2099–2104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030420797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponnaiya B, Jenkins-Baker G, Brenner DJ, Hall EJ, Randers-Pehrson G, Geard CR. Biological responses in known bystander cells relative to known microbeam-irradiated cells. Radiat Res. 2004;162:426–432. doi: 10.1667/rr3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sokolov MV, Smilenov LB, Hall EJ, Panyutin IG, Bonner WM, Sedelnikova OA. Ionizing radiation induces DNA double-strand breaks in bystander primary human fibroblasts. Oncogene. 2005;24:7257–7265. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belyakov OV, Mitchell SA, Parikh D, Randers-Pehrson G, Marino SA, Amundson SA, Geard CR, Brenner DJ. Biological effects in unirradiated human tissue induced by radiation damage up to 1 mm away. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14203–14208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sedelnikova OA, Nakamura A, Kovalchuk O, Koturbash I, Mitchell SA, Marino SA, Brenner DJ, Bonner WM. DNA double-strand breaks form in bystander cells after microbeam irradiation of three-dimensional human tissue models. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4295–4302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schettino G, Al Rashid ST, Prise KM. Radiation microbeams as spatial and temporal probes of subcellular and tissue response. Mutat Res. 2010;704:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olivieri G, Bodycote J, Wolff S. Adaptive response of human lymphocytes to low concentrations of radioactive thymidine. Science. 1984;223:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.6695170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azzam EI, Raaphorst GP, Mitchel RE. Radiation-induced adaptive response for protection against micronucleus formation and neoplastic transformation in C3H 10T1/2 mouse embryo cells. Radiat Res. 1994;138:S28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto H, Tomita M, Otsuka K, Hatashita M, Hamada N. Nitric oxide is a key molecule serving as a bridge between radiation-induced bystander and adaptive responses. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2011;4:126–134. doi: 10.2174/1874467211104020126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farooqi Z, Kesavan PC. Low-dose radiation-induced adaptive response in bone marrow cells of mice. Mutat Res. 1993;302:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(93)90008-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Day TK, Zeng G, Hooker AM, Bhat M, Scott BR, Turner DR, Sykes PJ. Extremely low priming doses of X radiation induce an adaptive response for chromosomal inversions in pKZ1 mouse prostate. Radiat Res. 2006;166:757–766. doi: 10.1667/RR0689.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakaya N, Lowe SW, Taya Y, Chenchik A, Enikolopov G. Specific pattern of p53 phosphorylation during nitric oxide-induced cell cycle arrest. Oncogene. 2000;19:6369–6375. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiencke JK, Afzal V, Olivieri G, Wolff S. Evidence that the [3H]thymidine-induced adaptive response of human lymphocytes to subsequent doses of X-rays involves the induction of a chromosomal repair mechanism. Mutagenesis. 1986;1:375–380. doi: 10.1093/mutage/1.5.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikushima T, Aritomi H, Morisita J. Radioadaptive response: efficient repair of radiation-induced DNA damage in adapted cells. Mutat Res. 1996;358:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(96)00120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hafer K, Iwamoto KS, Scuric Z, Schiestl RH. Adaptive response to gamma radiation in mammalian cells proficient and deficient in components of nucleotide excision repair. Radiat Res. 2007;168:168–174. doi: 10.1667/RR0717.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iyer R, Lehnert BE. Low dose, low-LET ionizing radiation-induced radioadaptation and associated early responses in unirradiated cells. Mutat Res. 2002;503:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Formenti SC, Demaria S. Systemic effects of local radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:718–726. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiraishi K, Nakagawa K, Niibe Y, Ishiwata Y, Yokochi S, Ohtomo K, Matsushima K. Abscopal Effect of Radiation Therapy and Signal Transduction. Current Signal Transduction Therapy. 2010;5:212–222. [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Essen CF. Radiation enhancement of metastasis: a review. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1991;9:77–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01756381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishiyama H, Teh BS, Ren H, Chiang S, Tann A, Blanco AI, Paulino AC, Amato R. Spontaneous regression of thoracic metastases while progression of brain metastases after stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotactic body radiotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: abscopal effect prevented by the blood-brain barrier? Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10:196–198. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prise KM, O’Sullivan JM. Radiation-induced bystander signalling in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:351–360. doi: 10.1038/nrc2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaminski JM, Shinohara E, Summers JB, Niermann KJ, Morimoto A, Brousal J. The controversial abscopal effect. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiraishi K. Abscopal Effect of Radiation Therapy: Current Concepts and Future Applications. In: Natanasabapathi Gopishankar., editor. Modern Practices in Radiation Therapy. InTech; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shiraishi K, Ishiwata Y, Nakagawa K, Yokochi S, Taruki C, Akuta T, Ohtomo K, Matsushima K, Tamatani T, Kanegasaki S. Enhancement of antitumor radiation efficacy and consistent induction of the abscopal effect in mice by ECI301, an active variant of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1159–1166. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohba K, Omagari K, Nakamura T, Ikuno N, Saeki S, Matsuo I, Kinoshita H, Masuda J, Hazama H, Sakamoto I, Kohno S. Abscopal regression of hepatocellular carcinoma after radiotherapy for bone metastasis. Gut. 1998;43:575–577. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.4.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bostrom PJ, Soloway MS. Secondary cancer after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: should we be more aware of the risk? Eur Urol. 2007;52:973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flint-Richter P, Sadetzki S. Genetic predisposition for the development of radiation-associated meningioma: an epidemiological study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park JK, Jang SJ, Kang SW, Park S, Hwang SG, Kim WJ, Kang JH, Um HD. Establishment of animal model for the analysis of cancer cell metastasis during radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:153. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheldon PW, Fowler JF. The effect of low-dose pre-operative X-irradiation of implanted mouse mammary carcinomas on local recurrence and metastasis. Br J Cancer. 1976;34:401–407. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goh K, Sumner H. Breaks in normal human chromosomes: are they induced by a transferable substance in the plasma of persons exposed to total-body irradiation? Radiat Res. 1968;35:171–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hollowell JG, Jr, Littlefield LG. Chromosome damage induced by plasma of x-rayed patients: an indirect effect of x-ray. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1968;129:240–244. doi: 10.3181/00379727-129-33295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pant GS, Kamada N. Chromosome aberrations in normal leukocytes induced by the plasma of exposed individuals. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 1977;26:149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Littlefield LG, Hollowell JG, Jr, Pool WH., Jr Chromosomal aberrations induced by plasma from irradiated patients: an indirect effect of X radiation. Further observations and studies of a control population. Radiology. 1969;93:879–886. doi: 10.1148/93.4.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camphausen K, Menard C. Angiogenesis inhibitors and radiotherapy of primary tumours. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2002;2:477–481. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Camphausen K, Moses MA, Menard C, Sproull M, Beecken WD, Folkman J, O’Reilly MS. Radiation abscopal antitumor effect is mediated through p53. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1990–1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan MA, Hill RP, Van Dyk J. Partial volume rat lung irradiation: an evaluation of early DNA damage. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00736-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khan MA, Van Dyk J, Yeung IW, Hill RP. Partial volume rat lung irradiation; assessment of early DNA damage in different lung regions and effect of radical scavengers. Radiother Oncol. 2003;66:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Langan AR, Khan MA, Yeung IW, Van Dyk J, Hill RP. Partial volume rat lung irradiation: the protective/mitigating effects of Eukarion-189, a superoxide dismutase-catalase mimetic. Radiother Oncol. 2006;79:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calveley VL, Khan MA, Yeung IW, Vandyk J, Hill RP. Partial volume rat lung irradiation: temporal fluctuations of in-field and out-of-field DNA damage and inflammatory cytokines following irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2005;81:887–899. doi: 10.1080/09553000600568002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mancuso M, Pasquali E, Leonardi S, Rebessi S, Tanori M, Giardullo P, Borra F, Pazzaglia S, Naus CC, Di Majo V, Saran A. Role of connexin43 and ATP in long-range bystander radiation damage and oncogenesis in vivo. Oncogene. 2011;30:4601–4608. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mancuso M, Pasquali E, Leonardi S, Tanori M, Rebessi S, Di Majo V, Pazzaglia S, Toni MP, Pimpinella M, Covelli V, Saran A. Oncogenic bystander radiation effects in Patched heterozygous mouse cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12445–12450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804186105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koturbash I, Kutanzi K, Hendrickson K, Rodriguez-Juarez R, Kogosov D, Kovalchuk O. Radiation-induced bystander effects in vivo are sex specific. Mutat Res. 2008;642:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fernandez-Palomo C, Schultke E, Smith R, Brauer-Krisch E, Laissue J, Schroll C, Fazzari J, Seymour C, Mothersill C. Bystander effects in tumor-free and tumor-bearing rat brains following irradiation by synchrotron X-rays. Int J Radiat Biol. 2013 doi: 10.3109/09553002.2013.766770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Narayanan PK, Goodwin EH, Lehnert BE. Alpha particles initiate biological production of superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide in human cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3963–3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou H, Ivanov VN, Lien YC, Davidson M, Hei TK. Mitochondrial function and nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated signaling in radiation-induced bystander effects. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2233–2240. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rajendran S, Harrison SH, Thomas RA, Tucker JD. The role of mitochondria in the radiation-induced bystander effect in human lymphoblastoid cells. Radiat Res. 2011;175:159–171. doi: 10.1667/rr2296.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lyng FM, Maguire P, McClean B, Seymour C, Mothersill C. The involvement of calcium and MAP kinase signaling pathways in the production of radiation-induced bystander effects. Radiat Res. 2006;165:400–409. doi: 10.1667/rr3527.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang H, Asaad N, Held KD. Medium-mediated intercellular communication is involved in bystander responses of X-ray-irradiated normal human fibroblasts. Oncogene. 2005;24:2096–2103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dickey JS, Baird BJ, Redon CE, Sokolov MV, Sedelnikova OA, Bonner WM. Intercellular communication of cellular stress monitored by gamma-H2AX induction. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1686–1695. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shao C, Stewart V, Folkard M, Michael BD, Prise KM. Nitric oxide-mediated signaling in the bystander response of individually targeted glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8437–8442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shao C, Lyng FM, Folkard M, Prise KM. Calcium fluxes modulate the radiation-induced bystander responses in targeted glioma and fibroblast cells. Radiat Res. 2006;166:479–487. doi: 10.1667/RR3600.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burney S, Caulfield JL, Niles JC, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. The chemistry of DNA damage from nitric oxide and peroxynitrite. Mutat Res. 1999;424:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McGlynn P, Lloyd RG. Recombinational repair and restart of damaged replication forks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:859–870. doi: 10.1038/nrm951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hallahan DE, Spriggs DR, Beckett MA, Kufe DW, Weichselbaum RR. Increased tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA after cellular exposure to ionizing radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:10104–10107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sherman ML, Datta R, Hallahan DE, Weichselbaum RR, Kufe DW. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor gene expression by ionizing radiation in human myeloid leukemia cells and peripheral blood monocytes. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1794–1797. doi: 10.1172/JCI115199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Woloschak GE, Chang-Liu CM, Shearin-Jones P. Regulation of protein kinase C by ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3963–3967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Witte L, Fuks Z, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Vlodavsky I, Goodman DS, Eldor A. Effects of irradiation on the release of growth factors from cultured bovine, porcine, and human endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 1989;49:5066–5072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brach MA, Gruss HJ, Kaisho T, Asano Y, Hirano T, Herrmann F. Ionizing radiation induces expression of interleukin 6 by human fibroblasts involving activation of nuclear factor-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8466–8472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okunieff P, Cornelison T, Mester M, Liu W, Ding I, Chen Y, Zhang H, Williams JP, Finkelstein J. Mechanism and modification of gastrointestinal soft tissue response to radiation: role of growth factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Polistena A, Johnson LB, Ohiami-Masseron S, Wittgren L, Back S, Thornberg C, Gadaleanu V, Adawi D, Jeppsson B. Local radiotherapy of exposed murine small bowel: apoptosis and inflammation. BMC Surg. 2008;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xanthinaki A, Nicolatou-Galitis O, Athanassiadou P, Gonidi M, Kouloulias V, Sotiropoulou-Lontou A, Pissakas G, Kyprianou K, Kouvaris J, Patsouris E. Apoptotic and inflammation markers in oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients receiving radiotherapy: preliminary report. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1025–1033. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Dundas GS, Mohiuddin M, Meredith RF, Rubin P, Weigensberg IJ. Can serum markers be used to predict acute and late toxicity in patients with lung cancer? Analysis of RTOG 91-03. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:368–376. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000260950.44761.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lorimore SA, Rastogi S, Mukherjee D, Coates PJ, Wright EG. The influence of p53 functions on radiation-induced inflammatory bystander-type signaling in murine bone marrow. Radiat Res. 2013;179:406–415. doi: 10.1667/RR3158.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sokolov MV, Dickey JS, Bonner WM, Sedelnikova OA. gamma-H2AX in bystander cells: not just a radiation-triggered event, a cellular response to stress mediated by intercellular communication. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2210–2212. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.18.4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Brooks AL. Extracellular signaling through the microenvironment: a hypothesis relating carcinogenesis, bystander effects, and genomic instability. Radiat Res. 2001;156:618–627. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0618:esttma]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barcellos-Hoff MH. Radiation-induced transforming growth factor beta and subsequent extracellular matrix reorganization in murine mammary gland. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3880–3886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vodovotz Y, Chesler L, Chong H, Kim SJ, Simpson JT, DeGraff W, Cox GW, Roberts AB, Wink DA, Barcellos-Hoff MH. Regulation of transforming growth factor beta1 by nitric oxide. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2142–2149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dickey JS, Baird BJ, Redon CE, Avdoshina V, Palchik G, Wu J, Kondratyev A, Bonner WM, Martin OA. Susceptibility to bystander DNA damage is influenced by replication and transcriptional activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10274–10286. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chai Y, Calaf GM, Zhou H, Ghandhi SA, Elliston CD, Wen G, Nohmi T, Amundson SA, Hei TK. Radiation induced COX-2 expression and mutagenesis at non-targeted lung tissues of gpt delta transgenic mice. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:91–98. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Partridge MA, Chai Y, Zhou H, Hei TK. High-throughput antibody-based assays to identify and quantify radiation-responsive protein biomarkers. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010;86:321–328. doi: 10.3109/09553000903564034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Narayanan PK, LaRue KE, Goodwin EH, Lehnert BE. Alpha particles induce the production of interleukin-8 by human cells. Radiat Res. 1999;152:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhou H, Ivanov VN, Gillespie J, Geard CR, Amundson SA, Brenner DJ, Yu Z, Lieberman HB, Hei TK. Mechanism of radiation-induced bystander effect: role of the cyclooxygenase-2 signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14641–14646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505473102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mukherjee D, Coates PJ, Rastogi S, Lorimore SA, Wright EG. Radiation-induced bone marrow apoptosis, inflammatory bystander-type signaling and tissue cytotoxicity. Int J Radiat Biol. 2013;89:139–146. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2013.741280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lorimore SA, Chrystal JA, Robinson JI, Coates PJ, Wright EG. Chromosomal instability in unirradiated hemaopoietic cells induced by macrophages exposed in vivo to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8122–8126. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lorimore SA, Mukherjee D, Robinson JI, Chrystal JA, Wright EG. Long-lived inflammatory signaling in irradiated bone marrow is genome dependent. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6485–6491. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lorimore SA, Coates PJ, Scobie GE, Milne G, Wright EG. Inflammatory-type responses after exposure to ionizing radiation in vivo: a mechanism for radiation-induced bystander effects? Oncogene. 2001;20:7085–7095. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fehsel K, Kolb-Bachofen V, Kolb H. Analysis of TNF alpha-induced DNA strand breaks at the single cell level. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:251–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vassalli P. The pathophysiology of tumor necrosis factors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:411–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rastogi S, Coates PJ, Lorimore SA, Wright EG. Bystander-type effects mediated by long-lived inflammatory signaling in irradiated bone marrow. Radiat Res. 2012;177:244–250. doi: 10.1667/rr2805.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Coates PJ, Rundle JK, Lorimore SA, Wright EG. Indirect macrophage responses to ionizing radiation: implications for genotype-dependent bystander signaling. Cancer Res. 2008;68:450–456. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rastogi S, Boylan M, Wright EG, Coates PJ. Interactions of apoptotic cells with macrophages in radiation-induced bystander signaling. Radiat Res. 2013;179:135–145. doi: 10.1667/RR2969.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Faber TJ, Japink D, Leers MP, Sosef MN, von Meyenfeldt MF, Nap M. Activated macrophages containing tumor marker in colon carcinoma: immunohistochemical proof of a concept. Tumour Biol. 2012;33:435–441. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0269-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.O’Neill LA. A critical role for citrate metabolism in LPS signalling. Biochem J. 2011;438:e5–6. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang Y, Choksi S, Chen K, Pobezinskaya Y, Linnoila I, Liu ZG. ROS play a critical role in the differentiation of alternatively activated macrophages and the occurrence of tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Res. 2013 doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ermakov AV, Konkova MS, Kostyuk SV, Izevskaya VL, Baranova A, Veiko NN. Oxidized extracellular DNA as a stress signal in human cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:649747. doi: 10.1155/2013/649747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dickey JS, Zemp FJ, Martin OA, Kovalchuk O. The role of miRNA in the direct and indirect effects of ionizing radiation. Radiation and environmental biophysics. 2011;50:491–499. doi: 10.1007/s00411-011-0386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Merrifield M, Kovalchuk O. Epigenetics in radiation biology: a new research frontier. Frontiers in genetics. 2013;4:40. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ilnytskyy Y, Kovalchuk O. Non-targeted radiation effects-an epigenetic connection. Mutat Res. 2011;714:113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ilnytskyy Y, Koturbash I, Kovalchuk O. Radiation-induced bystander effects in vivo are epigenetically regulated in a tissue-specific manner. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2009;50:105–113. doi: 10.1002/em.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kovalchuk O, Zemp FJ, Filkowski JN, Altamirano AM, Dickey JS, Jenkins-Baker G, Marino SA, Brenner DJ, Bonner WM, Sedelnikova OA. microRNAome changes in bystander three-dimensional human tissue models suggest priming of apoptotic pathways. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1882–1888. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dickey JS, Zemp FJ, Altamirano A, Sedelnikova OA, Bonner WM, Kovalchuk O. H2AX phosphorylation in response to DNA double-strand break formation during bystander signalling: effect of microRNA knockdown. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2011;143:264–269. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncq470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mothersill C, Smith RW, Fazzari J, McNeill F, Prestwich W, Seymour CB. Evidence for a physical component to the radiation-induced bystander effect? Int J Radiat Biol. 2012;88:583–591. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2012.698366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kalanxhi E, Dahle J. Genome-wide microarray analysis of human fibroblasts in response to gamma radiation and the radiation-induced bystander effect. Radiat Res. 2012;177:35–43. doi: 10.1667/rr2694.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kalanxhi E, Dahle J. Transcriptional responses in irradiated and bystander fibroblasts after low dose alpha-particle radiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2012;88:713–719. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2012.704657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ghandhi SA, Yaghoubian B, Amundson SA. Global gene expression analyses of bystander and alpha particle irradiated normal human lung fibroblasts: Synchronous and differential responses. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:63. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-1-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rzeszowska-Wolny J, Herok R, Widel M, Hancock R. X-irradiation and bystander effects induce similar changes of transcript profiles in most functional pathways in human melanoma cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Iwakawa M, Hamada N, Imadome K, Funayama T, Sakashita T, Kobayashi Y, Imai T. Expression profiles are different in carbon ion-irradiated normal human fibroblasts and their bystander cells. Mutat Res. 2008;642:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chaudhry MA. Radiation-induced gene expression profile of human cells deficient in 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanine glycosylase. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:633–642. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Herok R, Konopacka M, Polanska J, Swierniak A, Rogolinski J, Jaksik R, Hancock R, Rzeszowska-Wolny J. Bystander effects induced by medium from irradiated cells: similar transcriptome responses in irradiated and bystander K562 cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rugo RE, Almeida KH, Hendricks CA, Jonnalagadda VS, Engelward BP. A single acute exposure to a chemotherapeutic agent induces hyper-recombination in distantly descendant cells and in their neighbors. Oncogene. 2005;24:5016–5025. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Asur RS, Thomas RA, Tucker JD. Chemical induction of the bystander effect in normal human lymphoblastoid cells. Mutat Res. 2009;676:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Demidem A, Morvan D, Madelmont JC. Bystander effects are induced by CENU treatment and associated with altered protein secretory activity of treated tumor cells: a relay for chemotherapy? Int J Cancer. 2006;119:992–1004. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jin C, Wu S, Lu X, Liu Q, Qi M, Lu S, Xi Q, Cai Y. Induction of the bystander effect in Chinese hamster V79 cells by actinomycin D. Toxicol Lett. 2011;202:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rodier F, Coppe JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Munoz DP, Raza SR, Freund A, Campeau E, Davalos AR, Campisi J. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:973–979. doi: 10.1038/ncb1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, van Deursen J, Campisi J, Kirkland JL. Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype: therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:966–972. doi: 10.1172/JCI64098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Coppe JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Munoz DP, Goldstein J, Nelson PS, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2853–2868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hubackova S, Krejcikova K, Bartek J, Hodny Z. IL1- and TGFbeta-Nox4 signaling, oxidative stress and DNA damage response are shared features of replicative, oncogene-induced, and drug-induced paracrine ‘Bystander senescence’. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:932–951. doi: 10.18632/aging.100520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Coghlin C, Murray GI. Current and emerging concepts in tumour metastasis. J Pathol. 2010;222:1–15. doi: 10.1002/path.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. 1889. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1989;8:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Solinas G, Marchesi F, Garlanda C, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Inflammation-mediated promotion of invasion and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:243–248. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Szatrowski TP, Nathan CF. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51:794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hiscox S, Barrett-Lee P, Nicholson RI. Therapeutic targeting of tumor-stroma interactions. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15:609–621. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.561201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lisanti MP, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Pestell RG, Howell A, Sotgia F. Hydrogen peroxide fuels aging, inflammation, cancer metabolism and metastasis: the seed and soil also needs “fertilizer”. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2440–2449. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.15.16870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Jungst C, Cheng B, Gehrke R, Schmitz V, Nischalke HD, Ramakers J, Schramel P, Schirmacher P, Sauerbruch T, Caselmann WH. Oxidative damage is increased in human liver tissue adjacent to hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2004;39:1663–1672. doi: 10.1002/hep.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kryston TB, Georgiev AB, Pissis P, Georgakilas AG. Role of oxidative stress and DNA damage in human carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2011;711:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Balliet RM, Rivadeneira DB, Chiavarina B, Pavlides S, Wang C, Whitaker-Menezes D, Daumer KM, Lin Z, Witkiewicz AK, Flomenberg N, Howell A, Pestell RG, Knudsen ES, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Oxidative stress in cancer associated fibroblasts drives tumor-stroma co-evolution: A new paradigm for understanding tumor metabolism, the field effect and genomic instability in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 9:3256–3276. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Tsuyada A, Chow A, Wu J, Somlo G, Chu P, Loera S, Luu T, Li AX, Wu X, Ye W, Chen S, Zhou W, Yu Y, Wang YZ, Ren X, Li H, Scherle P, Kuroki Y, Wang SE. CCL2 mediates cross-talk between cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts that regulates breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2768–2779. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Trimmer C, Flomenberg N, Wang C, Pavlides S, Pestell RG, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Cancer cells metabolically “fertilize” the tumor microenvironment with hydrogen peroxide, driving the Warburg effect: implications for PET imaging of human tumors. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2504–2520. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.15.16585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gerashchenko BI, Ryabchenko NM, Glavin OA, Mikhailenko VM. The long-range cytotoxic effect in tumor-bearing animals. Exp Oncol. 2012;34:34–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Martin OA, Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura AJ, Bonner WM. Para-inflammation mediates systemic DNA damage in response to tumor growth. Communicative & integrative biology. 2011;4:78–81. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.1.13942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Martin OA, Redon CE, Nakamura AJ, Dickey JS, Georgakilas AG, Bonner WM. Systemic DNA damage related to cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3437–3441. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Carr MW, Roth SJ, Luther E, Rose SS, Springer TA. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 acts as a T-lymphocyte chemoattractant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3652–3656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Xu LL, Warren MK, Rose WL, Gong W, Wang JM. Human recombinant monocyte chemotactic protein and other C-C chemokines bind and induce directional migration of dendritic cells in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:365–371. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Boring L, Gosling J, Chensue SW, Kunkel SL, Farese RV, Jr, Broxmeyer HE, Charo IF. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2552–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kurihara T, Warr G, Loy J, Bravo R. Defects in macrophage recruitment and host defense in mice lacking the CCR2 chemokine receptor. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1757–1762. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Dewald O, Zymek P, Winkelmann K, Koerting A, Ren G, Abou-Khamis T, Michael LH, Rollins BJ, Entman ML, Frangogiannis NG. CCL2/Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 regulates inflammatory responses critical to healing myocardial infarcts. Circ Res. 2005;96:881–889. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163017.13772.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Rodemann HP, Bamberg M. Cellular basis of radiation-induced fibrosis. Radiother Oncol. 1995;35:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(95)01540-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Xia M, Sui Z. Recent developments in CCR2 antagonists. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2009;19:295–303. doi: 10.1517/13543770902755129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Bischoff SC, Krieger M, Brunner T, Dahinden CA. Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 is a potent activator of human basophils. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1271–1275. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]