INTRODUCTION

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has proposed “Increasing the proportion of children with mental health problems who receive treatment” as one of its Healthy People 2020 Objectives.(1) With high rates (2) and increasing prevalence of childhood behavioral and developmental (DB) conditions,(3–6) promptly identifying and treating these disorders is important so that children’s functional outcomes can be maximized. In addition, since long-term treatment of childhood DB conditions is expensive,(7–9) intervention in early childhood has the potential to produce large cost savings.(10)

However, as with other areas of child health,(11, 12) racial/ethnic and language disparities exist in the diagnosis and treatment of early childhood DB conditions. For instance, compared to other children, African-American and Latino children are less likely to be diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and are more likely to be diagnosed at older ages and with more severe symptoms.(13–18) Likewise, African-American and Latino children are less likely to be diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and are less likely to be treated with a stimulant medication once diagnosed.(19–22) Table 1 summarizes recent peer-reviewed studies of diagnostic disparities in ASD and ADHD, two common early childhood developmental conditions. Similar disparities exist in the areas of overall developmental risk,(23) depression and mental health disorders,(24–26) use of psychotropic medications,(27) and use of mental health services.(28) These racial and ethnic disparities deserve increased attention given recent demographic trends: Census estimates suggest that the U.S. population younger than age 5 is nearly 50% racial/ethnic minority,(29) and some states are now “majority minority” for young children (30)

Table 1.

Racial and Ethnic Differences in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Diagnosis Rates

| Author | Data source | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|

| ADHD | ||

| Rolwand, 2002(107) | School-based sample of 7333 children | African-American children were less likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than white children, and were less likely to be currently taking medication to treat ADHD. |

| Stevens, 2005(20) | 18,708 children in 1997–2000 Medical Expenditures Survey Panel | Latino and African-American children were less likely to be diagnosed with ADHD by parent report than were white American children. African-American youths with ADHD were less likely to initiate stimulant medication relative to white children. |

| Pastor, 2005(19) | 21,294 children in the 1997–2001 National Health Interview Survey | Latino and African American children, compared to white children, had less frequent parental reports of ADHD. |

| Miller, 2009(108) | Systematic Review/Meta-analysis | African Americans were less likely to have an ADHD diagnosis. African-Americans, when diagnosed, had greater severity scores. |

| ASD | ||

| Mandell, 2002(14) | Medicaid claims for 406 children diagnosed with autism | African-American children were diagnosed with autism at older ages than white children, and required more time in treatment before receiving an autism diagnosis. |

| Croen, 2002(16) | Birth certificate and health service agency records for >3 million children in California | Children of African-American mothers were more likely to have ASD compared to children of white mothers. Children of Latino mothers and of Mexican immigrants were less likely to have ASD than white children. |

| Liptak, 2008(56) | 102,353 in the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health | Parent-reported prevalence of ASD was lower for Latino than white children; rates were similar for African-American and white children. |

| Kogan et al, 2009(5) | 78,037 children included in the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health | African-American children were less likely than white children to have ever had, or currently have, an ASD. |

| Mandell et al, 2009(13) | Review of medical and educational records for 2168 children in a multi-site network | African-American, Latino, and other race children were less likely to have a documented ASD. |

| Palmer et al, 2010(15) | Data from Texas Educational Agency and Health Resources and Services Administration | School districts with more Latino children had lower rates of ASD. |

| Fountain et al, 2011(17) | Linked birth and administrative records on 17,185 children with diagnoses of autistic disorder born in California between 1992 and 2001 | African-American, Latino, Asian, and other race children were diagnosed with ASDs at older ages than white children. |

| Jarquin et al, 2011(109) | Data from the Metropolitan Atlanta | Prevalence of ASDs was higher for Non-Hispanic Whites than for Non-Hispanic Black children |

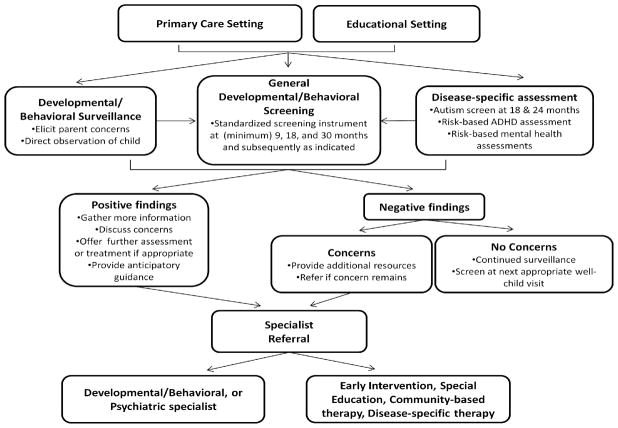

The medical evaluation and treatment of young children at risk for DB disorders is a complex process involving many steps. The process begins when families identify developmental concerns about their children and raise these concerns with health care providers (Figure 1). Alternatively, a medical or other community or educational professional may recognize a concern via direct observation, developmental/behavioral surveillance, or standardized developmental/behavioral or disease-specific screening. Once a concern is identified, the next step is diagnosis and treatment. Whereas some disorders (such as ADHD) can be diagnosed and treated in the primary care setting, in many cases, a child must be referred to a developmental or mental health specialist for diagnosis through further testing and clinical evaluation. In addition, the child may require additional therapeutic services (such as Early Intervention or disorder-specific therapy).(31, 32)

Figure 1.

Developmental evaluation and referral process

Adapted from AAP developmental surveillance and screening algorithm and autism screening algorithm (31, 32)

In this review article, we examine the screening, referral, and evaluation process for early childhood DB conditions, assessing points in the process where which racial/ethnic and language disparities are known or likely to occur. In addition, this review article contributes to the current base of knowledge by exploring possible reasons for these disparities. First, we examine different parent beliefs about DB problems among minority children. We also address how minority children are cared for in primary and specialty care settings, looking at missed opportunities for identification of concerns and follow-up of abnormal findings. We investigate the performance of developmental and behavioral screening and diagnostic tests among minority children. Finally, we highlight areas for additional research and suggest possible improvements to reduce racial/ethnic and language disparities in DB care.

METHODS

We used searched the Medline and PSYCinfo databases using title words and MeSH keywords, with a focus on original, peer-reviewed studies written in English. Our search terms included African American, Asian American, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Child, Child Development, Child Development Disorders, Developmental Delay, Developmental Disabilities, Ethnic Groups, Health care disparities, Health services accessibility, Health status disparities, Hispanic Americans, Indians (North American), Intellectual Disability, Latinos, Medically Underserved, Mental Health, Mental Retardation, Minority Groups, Minority Health, Pediatric, Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Population Group, Race, Socioeconomic factors, and Underserved. Publications were individually reviewed for suitability of inclusion per the review article’s goals as stated above. In addition, we reviewed the references of selected publications for other studies that would meet the review’s goals. Finally, we held conversations with experts in child developmental disabilities and health care disparities to see if they could recommend additional studies that had been missed by our review.

PARENT BELIEFS ABOUT CHILD DEVELOPMENT, BEHAVIOR, AND MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES USE

Parent Understanding of Normal Child Development and Behavior

As many evaluations of a child’s mental or developmental status begin with a parental concern, racial/ethnic and cultural variation in parent concerns may affect whether, and for what reason a child receives a DB evaluation. For instance, evidence suggests that perceptions of normal child development relate to family cultural background: compared to white parents, African-American and Latino parents differ in views of when children reach basic developmental milestones, and additionally have different views about parenting behaviors such as how important it is to talk or read to young children.(33–36) Table 2 shows several studies that demonstrate such points. For instance, in a survey of parents of different race/ethnicity, Pachter et al showed that Puerto Rican, African American, and European American mothers differ in their beliefs about age of attainment of developmental milestones such as smiling, knowing their own name, and toilet training—expecting some milestones earlier and others later.(34) These differences persisted even after controlling for maternal age, education, and socioeconomic status. Similarly, in the “Zero to Three” survey, which assessed a population-based sample of parents of different race/ethnicity, white parents were more likely than Latino or African American parents to identify setting and enforcing rules, comforting a child when he/she is distressed, and encouraging a children to continue working on a difficult task, as important influences on a child’s socio-emotional development.(33) Little current research disentangles whether such differences arise from inherent cultural beliefs versus differential treatment or education of minority parents by health care and educational professionals.

Table 2.

Parent Perceptions about Child Development and Behavior

| Author | Data source | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Beliefs about normative development and parenting | ||

| Pachter, 1997(34) | Survey of 255 mothers seeking healthcare for their children at clinics in Hartford, CT. | Parents of Puerto Rican, African American, and European American children differed in views about age of attainment of 9/25 developmental milestones. |

| Bornstein, 2004(35) | Survey of 114 mothers of 20-month-old infants in Washington, DC. | Japanese and South American immigrant mothers scored significantly lower on an evaluation of parenting knowledge compared to multigenerational US mothers. |

| Keels, 2008(36) | Analysis of Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Study data on 1198 families. | Hispanic-, European-, and African-American parents differ significantly in parent beliefs and behaviors as assessed on a standardized measure. |

| Hart Research Associates, 2009(33) | Consumer-based survey of 1,615 parents of infants and toddlers | African-American and Hispanic parents differ from white parents in beliefs about important influences on socio-emotional development of children (e.g. talking about feelings, establishing routines, enforcing rules). |

| Beliefs about mental health and developmental disorders | ||

| Yeh, 2004(37) | Survey of 1,338 parents of youths age 6–17 with identified mental health problems. | Parents of African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander American, and Latino youths were less likely than parents of white children to endorse etiologies consistent with biopsychosocial beliefs about mental illness. |

| Bussing, 2003(40) | Interviews with 182 parents of school-age children with ADHD | More African-American than white parents were unsure about potential causes and treatments for ADHD. |

| Bussing, 1998(110) | Interviews with 486 parents of school-age children qualified for special educational services | Fewer African-American parents had heard of ADHD, knew about it, or had received ADHD information from a physician. |

| Garcia, 2000(111) | Ethnographic interviews with 7 Mexican-American parents of children with communication problems | Mexican-American parents perceived their child’s language delay as within normal range. Parents did not perceive early interventionists’ interactions with children as modeling communication strategies but rather as “playing” with their children. |

| Kummerer, 2007(112) | Qualitative interviews with 14 Mexican immigrant parents of children with expressive language delays | Mexican parents perceive expressive language delays but not receptive language delays; causal attributions were medical or familial in nature. |

Several studies show that differing parental understandings of the limits of typical child behavior may impact specific DB problems and result in different rates of mental health care utilization (Table 2). For instance, in a large survey of parents of youths with identified mental health problems, Yeh et al showed that African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Latino parents were less likely to view emotional/behavioral problems as having a mental health basis.(37) Other studies have shown that some minority families are more likely to attribute mental health symptoms to “emotional” or “personality” conditions, and are less likely to agree with mental health professionals’ labels of the condition.(38) These different beliefs are associated with lower rates of use of mental health services.(38, 39) Minority parents may also have lower awareness of the symptoms of common mental health disorders: in both ethnographic interviews and surveys, Bussing et al found that African American parents were found to be less likely to have heard of ADHD, less likely to have had recent exposure to ADHD information, know less about the causes and treatment of ADHD, and are less likely to report knowing someone who has ADHD.(21, 40)

Parent Beliefs about Mental Health Care

Because of cultural beliefs, historical factors, and long-standing mistreatment of minorities by health care and educational systems, minority parents may additionally feel there is less value in interacting with the healthcare and educational systems to obtain DB treatment for their child. Minority parents may be more likely to distrustful of medicine in general,(41) and mental health treatment in particular. For example, a survey of 501 caregivers of children found that African American parents viewed use of antidepressants in children as more risky and less beneficial than other parents.(42) Additionally, minority parents may also have greater concerns about the stigma attached to seeking mental health services. This stigma may be compounded by the fact that many parents believe that mental health treatment is ineffective or unhelpful. In a survey of 235 low-income families of school-age children, Richardson et al found that African-American parents are twice as likely as white parents to expect disapproval from family members and to be embarrassed about seeking mental health care for their child, are twice as likely to perceive mental health professionals as untrustworthy and disrespectful, and are three times more likely to expect poor care.(43) Likewise, in a mental health clinic setting serving a predominately African-American and Latino population, McKay et al showed that many parents expressed skepticism regarding the potential helpfulness of mental health care. This skepticism about the benefits of mental health care was associated with about half the odds of attending mental health appointments.(44) Other studies have shown that Latino and other minority parents do not bring their children into care because providers don’t understand cultural differences,(45) do not put forth effort to getting their child services, have negative attitudes toward minorities, or treat minority families poorly.(46) In many cases, these beliefs may be justified because the mental health system does not perform as well for minority and other under-served families.(26,47)

ACCESS TO DB SERVICES IN THE PRIMARY AND SPECIALTY CARE SETTINGS

Access to Primary Care and Primary Care Quality

Identification of DB disorders in minority children in the medical setting may be problematic for a variety of reasons. First, and perhaps most importantly, minority children are less likely to have access to primary care,(48, 49) and are more likely to face barriers to needed care compared to other families,(45) leaving less opportunity for parents to present their concerns to providers or have concerning findings further evaluated. Poorer access to basic services may relate to poorer access to health insurance among minority children;(12, 45) however, minorities still have poorer access to care even after insurance status is taken into account.(47, 50) Additionally, the primary care that minority children and children from limited English proficient (LEP) families receive is generally of lower quality than that of white children,(11) so minority families may not receive all recommended services even when care is accessed. For instance, minority and LEP families are less likely to receive desired anticipatory guidance or family-centered care,(51–53) which are associated with improved identification of developmental issues.(54) This may be particularly the case for children with developmental disorders: in a study using the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, Montes and colleagues showed that family-centered care is lower among African-American children with ASDs than among white children with ASDs.(55) Liptak and colleagues used a similar national dataset to show that African-American and Latino children with ASDs are less likely to have access to care than white children, even after adjusting for socio-demographic differences.(56)

As many DB disorders are identified through primary care-based developmental surveillance or standardized developmental screening (Figure 1), access to these services is critical. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends standardized developmental and behavioral screening at minimum of at the 9-, 18-, and 24–30 month well-child visits and subsequently when indicated,(32) and additionally recommends specific screening for autism spectrum disorders at the 18- and 24- month visits.(31) Once a concern has been identified, a healthcare provider must evaluate the concern, and (if necessary) refer a child to diagnostic and/or therapeutic resources (Figure 1).

Despite these recommendations, recent studies have shown that Spanish-speaking Latino parents and African-American parents are less likely to be asked by a provider about their developmental concerns, a difference that persists even when their child is at high risk of a developmental disorder.(54, 57) In contrast, other studies have suggested that when they do access care, minority children are more likely to receive standardized developmental and behavioral screening.(58, 59) It is possible that providers are depending on standardized screening of minority children because they feel they are less able to identify developmental or behavioral problems in minority children through surveillance or discussion alone.(60) This may particularly be a problem when the patient and the provider are from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds.(61) Though low numbers for surveillance are concerning, high rates of screening may be a positive development, as screening is more effective than surveillance in detecting developmental and behavioral disorders.(32)

Access to Specialty Services, Specialty Referral Process, and Quality of Specialty Care

When indicated, early referral to DB services is important because early access to therapy services is associated with improved cognitive, behavioral, and social outcomes.(10, 31) Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Educational Act (IDEA) entitles children to have access to appropriate therapy services (such as Early Intervention or Special Education) even prior to diagnosis (Figure 1).(32) However, when a child is referred from primary care to a specialist such as a developmental-behavioral pediatrician, child psychiatrist, or child psychologist, additional disparities occur. Multiple studies document racial, ethnic, and language disparities in access to specialist care in general, (62, 63) and disparities particular to DB specialty services may also exist.(50) For instance, several studies show racial/ethnic differences in Early Intervention participation: African-American children are less likely to participate in Early Intervention services,(64, 65) and one study suggests that part of this difference may be related to race differences in provider referral patterns.(66) Clements et al recently showed that African-American infants were less likely to receive a developmental evaluation from Early Intervention once referred, and that having a foreign-born, non-English speaking, or Asian parent was also associated with decreased likelihood of enrollment in Early Intervention therapy services.(67) Paradoxically, though fewer minority children access Early Intervention, multiple studies show that once they reach school age, Latino children, Native American children, and children in LEP households are over-represented in Special Education settings, especially those with qualifying diagnoses of intellectual disability or emotional disturbance.(68, 69) Though reasons for this disproportionate representation are complex,(70) these findings suggest that increasing minority participation in early intervention programs may be one way to prevent more serious DB diagnoses later in childhood.

Provider bias may also be contributing to different rates of referral and diagnosis. Providers may find it more difficult to disentangle underlying medical disorders from a child’s cultural and socioeconomic context, and thus may be less likely to refer a child whose social or cultural context is unfamiliar. For instance, in a study by Cuccaro et al, pediatric speech-language pathologists, psychologists, and psychiatrists were provided vignettes describing children at risk for developmental difficulties. In these vignettes, higher socioeconomic status correlated with an increased assignment of autism diagnoses.(71) Likewise, in a study where white psychotherapists studied case vignettes of African-American and white adolescents, therapists gave less severe ratings for 8 of 21 pathological behaviors when they occurred in African Americans.(72)

Minority families may also have less information about how to access and effectively use developmental services(73, 74) and fewer support services that connect them to specialty care, such as a case manager or care coordinator.(74, 75) Poor quality of services, or lack of cultural competence among service providers, may lead to visit non-attendance or early disenrollment. For instance, studies show that African-American and Latino families are more likely than white families to be unsatisfied with Early Intervention services,(73) and Latino parents are more likely to state that they did not have adequate involvement in decision-making about their child’s care in Early Intervention.(74, 76)

Another important factor may be service availability: overall, unmet needs for mental health care are high, and may be particularly unavailable to minority children, who often face barriers related both to access and insurance coverage.(50) In particular, developmental assessment and therapy may be poorly covered by insurance, making care unaffordable to many minority families.(77) Even if services are available, specialty mental health services often are not located where minority children live. Sturm et al found that geographic disparities in mental health care account for many apparent differences in mental health utilization according to race/ethnicity.(78) Minority families may also have difficulty accessing services due to financial, transportation, or child care issues.(79)

SCREENING AND ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Given that developmental and behavioral screening is now recommended for all children, parents, health care providers, and community professionals need to rely on screening tools’ ability to assess risk for developmental or behavioral disorders among all children, including racial/ethnic minorities, and children from LEP households. Likewise, reliability of standardized diagnostic tools in the specialty care setting is important to making definitive diagnoses of DB disorders.

Although improvements have been made to several tools, many screening and diagnostic tools were developed using relatively small numbers of children,(80) and in many cases, racial/ethnic, and language minority children were under-represented on the test’s norming sample (the sample population on which the test parameters were developed). For example, some minorities were under-represented in the norming populations of the Denver Developmental Screening – II, (81) one of the most commonly used developmental screening instruments. Other tests, such as the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS) or the Ages & Stages Questionnaires, Third Edition (ASQ-3) were initially normed on less-diverse populations, although both tests have been subsequently re-validated on larger, more diverse samples.(82, 83)

Even when minority children were included as part of the reference population, it is often unclear whether this population included enough poorly-performing children to be sure that the test meets sensitivity and specificity parameters in this population.(80) Conversely, if too many included minority children perform poorly, the inclusion of these children may decrease the mean performance on the test, so that minority children who are at risk for disorders still score in the normal range.(84) For example, the initial norming group for the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (MCHAT) included only eight Spanish speakers, none of whom were deemed “high-risk.”(85) The Spanish MCHAT instrument was recently modified and validated for a larger population of children in Spain; (86) however, the Spanish – Western Hemisphere version of the M-CHAT has not been validated(87) and testing of a Mexican Spanish M-CHAT version reveals evidence for cultural differences in item responses.(88)

When developing an instrument, individual items should also undergo validity testing in different racial/ethnic and language groups. Content bias can occur because individual items may perform differently across racial/ethnic and cultural groups due to different parent beliefs, child-rearing practices, or customs.(84, 89) For instance, in the Spanish validation of the MCHAT, several of the items had to be changed because of the use of different toys in Spain and Spanish colloquialisms.(86) Racial/ethnic differences have also been found in diagnostic scales such as the Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised (ADI-R),(90) and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (ADHD measurement scale).(91) Even if minority parents understand the content of the individual items, they may respond differently because they interpret the intent of the test as a whole in a different way.(89)

Observational and interview-based scales, such as the Denver-II, may be subject to additional biases related to the race/ethnicity or language of the interviewer, rater, or coder. For instance, if the observer/coder is of a different language or dialectical background than the subject, language delays may be either over identified or under identified because the interviewer does not understand what the subject is saying.(84) It is also possible that raters interpret the behavior of children of different race/ethnicity or cultural groups differently. For example, in a study using videotaped vignettes of child behavior, Chinese and Indonesian clinicians gave the same children significantly higher scores for hyperactivity than did Japanese and American clinicians.(92) Similar clinician/child ethnicity interactions have been found with the Conners ADHD Rating Scale.(93) For diagnostic scales that require the child to interact with the rater or scorer, such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development – II or the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, accurate scoring may not be possible if a same-language, culturally-congruent examiner is not available.(94) Scoring errors could also occur due to racial bias or prejudice of the scorers.(95)

PROGRAM AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Improving Access and Quality of Care

At the most basic level, improving access to DB care necessitates improvements in access to primary and specialty care services. Although most U.S. children successfully access primary care, rates are lower in minority children,(11) and specialist access is particularly challenging for underserved children.(63) However, given the preponderance of minority children do access basic care, improving the quality of services is perhaps as important as improving access. Increased availability of culturally-congruent patient materials, interpreters, and case managers may help minority families access the services they need. Coordination of DB services may particularly help minority families, as they are more likely to lack information, feel dissatisfied about developmental services, and experience barriers to care. Several recent efforts show potential to reduce mental health disparities in the primary care setting. For instance, the Healthy Steps program uses co-located developmental specialists to identify and follow-up on developmental problems, provide developmental screening, follow-up parental concerns, and make home visits.(96) This program might particularly benefit minority families as it allows more of the developmental screening and referral process to take place in the medical home. Providers should also take advantage of the opportunity to collaborate with community home visitors such as the Healthy Families and Nurse-Family Partnership programs.(97, 98)

Increasing Surveillance and Screening

Because minority parents are less likely to be asked about their concerns in the primary care setting,(54, 57) providers should be actively encouraged to inquire about minority parents’ concerns and provide continuous surveillance in addition to conducting standardized screening. Parental concerns or abnormal screening results should not be easily dismissed on the basis of bilingualism, “cultural differences,” or “social risk factors.” Additionally, since developmental surveillance may under-reach minorities, standardized developmental screening in the primary care setting holds particular promise for improving identification of disorders among minority children.

With recent policy recommendations from the AAP and the American Academy of Family Practice Physicians,(32) developmental screening has become more widespread. Nonetheless, less than one third of pediatric primary care providers use a formal screening instrument to assess developmental risk(99) and a survey found that only 10% of primary care providers in California offered both general developmental and ASD screenings in Spanish.(60) Encouraging providers to use formal screening in addition to clinical judgment may help minority children connect to developmental services. Several recent projects have demonstrated the feasibility of increasing developmental surveillance and screening in the primary care setting. In the Assuring Better Child Health and Development (ABCD) project, North Carolina undertook a county-based program to encourage developmental screening, successfully raising rates of screening to >70% of well child visits.(100) Providing specific, culturally-tailored information to parents about the importance of developmental surveillance and screening may help providers more accurately identify minority parents’ concerns. In addition, providers need a better system to follow-up referrals that are placed as a result of abnormal developmental screens, since minority families may be less likely to complete specialty evaluations. Consideration of simultaneous referral to diagnostic and therapeutic (intervention) services may be particularly important for minority and LEP families.

Improving Quality of Screening and Diagnostic Instruments

Any recommendation to increase surveillance or screening must be balanced by increasing calls to improve the quality and performance of screening and diagnostic instruments for minority children and children in LEP households. This includes sampling adequate numbers of minority children of all developmental levels in instruments’ norming populations, as well as performing construct and content validity testing among minority children. Screening instruments must not only be made available in more languages, but translations should also be validated in these languages so that they function similarly to the English versions. The publishers of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires have recently published guidelines for cultural and linguistic adaptation of their instruments(101) which is an encouraging example of how to improve the quality and performance of screening tools for diverse populations. Improved education of providers regarding cultural variations in child behavior and cultural expectations of developmental milestones may also help providers appropriately score instruments and interpret their results.

Collaborating with Community Providers

The health care environment is not the only setting in which children’s development can be assessed. Many early childhood education programs (such as Early Head Start) provide developmental screening and surveillance, and screening can also occur in community programs such as Women, Infant, and Children supplemental nutrition programs(102) and state child welfare programs.(103) Although research is lacking in this area, informal networks and other groups such as faith-based groups, parenting classes, and health fairs may also be important information sources about early childhood development. Health care partnerships with community providers and organizations may allow healthcare professionals more opportunities to identify at-risk children. One promising model is Connecticut’s Help Me Grow program, which offers a centralized hotline that providers or parents with concerns about a child’s behavior can use to assess a child’s developmental risk and connect the child with appropriate resources. The program also provides additional training to providers in developmental surveillance and screening.(104)

Increasing Provider Education and Diversity

Improving the cultural competency of providers at all points in the system is essential in improving access to care for vulnerable minority children. This includes education in cultural variability in developmental and behavioral expectations for children, cultural variation in views of mental health treatment, typical language development in bilingual children, and education on the stigma and bias that many minority families face when attempting to interface with the mental health system. Education should start early in health care providers’ careers, preferably during medical/nursing school or residency, exposing medical students and residents to the problems minority children face in accessing DB services. Programs that allow trainees to participate in Early Intervention evaluations, or spend additional time in minority communities may allow for increased competence in advocating for at risk children.(105) In addition, ongoing efforts should be made to increase the number of minority providers at all levels of care. Having a race-concordant provider has been shown to improve patient comfort and satisfaction with care, which is particularly important when discussing sensitive issues such as child mental health.(106) Minority providers are also more likely to serve in minority communities, which could improve access to DB care.(95, 106) Grant and scholarship programs targeted at increasing minorities in health professions should be encouraged and sustainably funded. In addition, mentorship programs for minority students and others interested in minority health can provide important early career experience and information about career opportunities. Such programs should be supported and expanded.

CONCLUSION

Early evaluation and treatment of all children with developmental, behavioral, and mental health concerns is in the best interest not only of children, families, and healthcare providers, but also of institutions and policymakers. Though disparities exist in many parts of the evaluation and referral process, reducing disparities is possible through coordinated efforts. Ensuring equitable access to early childhood developmental, behavioral, and mental health services is an important long-term investment in the health of minority children.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Glenn Flores and Dr. Frances Glascoe for their helpful review of drafts of this article.

Dr. Zuckerman’s effort was partially supported by grant #1K23MH095828 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Healthy people 2020: Mental health and mental disorders. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=28.

- 2.Halfon N, Newacheck PW. Prevalence and impact of parent-reported disabling mental health conditions among U.S. children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999 May;38(5):600, 9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199905000-00023. discussion 610–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning disability: United states, 2004–2006. National Center for Health Statistics Vital Health Stat. 2008;10(237) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumberg SJ, Bramlett MD, Kogan M, Schieve LA, Jones JR, Lu MC. Changes in parent-reported prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in school-aged US children: 2007 to 2011–12. Hyattsville, MD: National Health Statistics Reports; 2013. Report No.: 65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kogan MD, Blumberg SJ, Schieve LA, Boyle CA, Perrin JM, Ghandour RM, et al. Prevalence of parent-reported diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among children in the US, 2007. Pediatrics. 2009 Nov;124(5):1395–403. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012 Mar 30;61(3):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson JW, Mulick JA. System and cost research issues in treatments for people with autistic disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000 Dec;30(6):585–93. doi: 10.1023/a:1005691411255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swensen AR, Birnbaum HG, Secnik K, Marynchenko M, Greenberg P, Claxton A. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Increased costs for patients and their families. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003 Dec;42(12):1415–23. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelham WE, Foster EM, Robb JA. The economic impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007 Jul;32(6):711–27. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA. From neurons to neighborhoods. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flores G Committee On Pediatric Research. Technical report--racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125(4):e979–e1020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in medical and dental health, access to care, and use of services in US children. Pediatrics. 2008 Feb;121(2):e286–98. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandell DS, Wiggins LD, Carpenter LA, Daniels J, DiGuiseppi C, Durkin MS, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the identification of children with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Public Health. 2009 Mar;99(3):493–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandell DS, Listerud J, Levy SE, Pinto-Martin JA. Race differences in the age at diagnosis among Medicaid-eligible children with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002 Dec;41(12):1447–53. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200212000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer RF, Walker T, Mandell D, Bayles B, Miller CS. Explaining low rates of autism among Hispanic schoolchildren in Texas. Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100(2):270–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croen LA, Grether JK, Selvin S. Descriptive epidemiology of autism in a California population: Who is at risk? J Autism Dev Disord. 2002 Jun;32(3):217–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1015405914950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fountain C, King MD, Bearman PS. Age of diagnosis for autism: Individual and community factors across 10 birth cohorts. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011 Jun;65(6):503–10. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.104588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen A, Pettygrove S, Meaney FJ, Mancilla K, Gotschall K, Kessler DB, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white children. Pediatrics. 2012 Mar 01;129(3):e629–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Racial and ethnic differences in ADHD and LD in young school-age children: Parental reports in the national health interview survey. Public Health Rep. 2005 Jul-Aug;120(4):383–92. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Race/ethnicity and insurance status as factors associated with ADHD treatment patterns. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005 Feb;15(1):88–96. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bussing R, Schoenberg NE, Perwien AR. Knowledge and information about ADHD: Evidence of cultural differences among African-American and white parents. Soc Sci Med. 1998 Apr;46(7):919–28. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, Garvan CW. Barriers to detection, help-seeking, and service use for children with ADHD symptoms. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2003 Apr-Jun;30(2):176–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02289806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens GD. Gradients in the health status and developmental risks of young children: The combined influences of multiple social risk factors. Matern Child Health J. 2006 Mar;10(2):187–99. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0062-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chabra A, Chavez GF, Harris ES. Mental illness in elementary-school-aged children. West J Med. 1999 Jan;170(1):28–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chabra A, Chavez GF, Harris ES, Shah R. Hospitalization for mental illness in adolescents: Risk groups and impact on the health care system. J Adolesc Health. 1999 May;24(5):349–56. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmerman FJ. Social and economic determinants of disparities in professional help-seeking for child mental health problems: Evidence from a national sample. Health Serv Res. 2005 Oct;40(5 Pt 1):1514–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leslie LK, Weckerly J, Landsverk J, Hough RL, Hurlburt MS, Wood PA. Racial/ethnic differences in the use of psychotropic medication in high-risk children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003 Dec;42(12):1433–42. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000091506.46853.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Hough RL, Landsverk JA. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 Jul;162(7):1336–43. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Most children younger than age 1 are minorities, census bureau reports. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-90.html.

- 30.Toward a more vibrant and youthful nation: Latino children in the 2010 census. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.nclr.org/index.php/publications/toward_a_more_vibrant_and_youthful_nation_latino_children_in_the_2010_census/

- 31.Johnson CP, Myers SM American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):1183–215. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Council on Children With Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: An algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006 Jul 1;118(1):405–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parenting infants and toddlers today: Research findings. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.zerotothree.org/parentsurvey.

- 34.Pachter LM, Dworkin PH. Maternal expectations about normal child development in 4 cultural groups. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997 Nov;151(11):1144–50. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170480074011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bornstein MH, Cote LR. “Who is sitting across from me?” immigrant mothers’ knowledge of parenting and children’s development. Pediatrics. 2004 Nov;114(5):e557–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keels M. Ethnic group differences in early head start parents’ parenting beliefs and practices and links to children’s early cognitive development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2009;24(4):381–97. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeh M, Hough RL, McCabe K, Lau A, Garland A. Parental beliefs about the causes of child problems: Exploring racial/ethnic patterns. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004 May;43(5):605–12. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200405000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guarnaccia PJ, Parra P. Ethnicity, social status, and families’ experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Ment Health J. 1996 Jun;32(3):243–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02249426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough RL, Lau A, Fakhry F, Garland A. Why bother with beliefs? examining relationships between race/ethnicity, parental beliefs about causes of child problems, and mental health service use. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005 Oct;73(5):800–7. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bussing R, Gary FA, Mills TL, Garvan CW. Parental explanatory models of ADHD: Gender and cultural variations. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003 Oct;38(10):563–75. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0674-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajakumar K, Thomas SB, Musa D, Almario D, Garza MA. Racial differences in parents’ distrust of medicine and research. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009 Feb;163(2):108–14. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevens J, Wang W, Fan L, Edwards MC, Campo JV, Gardner W. Parental attitudes toward children’s use of antidepressants and psychotherapy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009 Jun;19(3):289–96. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richardson LA. Seeking and obtaining mental health services: What do parents expect? Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2001;10;15(5):223–31. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2001.27019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKay MM, Pennington J, Lynn CJ, McCadam K. Understanding urban child mental health l service use: Two studies of child, family, and environmental correlates. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2001 Nov;28(4):475–83. doi: 10.1007/BF02287777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flores G, Abreu M, Tomany-Korman SC. Why are Latinos the most uninsured racial/ethnic group of US children? A community-based study of risk factors for and consequences of being an uninsured Latino child. Pediatrics. 2006 Sep;118(3):e730–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shapiro J, Monzo LD, Rueda R, Gomez JA, Blacher J. Alienated advocacy: Perspectives of Latina mothers of young adults with developmental disabilities on service systems. Ment Retard. 2004 Feb;42(1):37–54. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2004)42<37:AAPOLM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 Sep;159(9):1548–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi L, Stevens GD. Disparities in access to care and satisfaction among U.S. children: The roles of race/ethnicity and poverty status. Public Health Rep. 2005 Jul-Aug;120(4):431–41. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevens GD, Seid M, Mistry R, Halfon N. Disparities in primary care for vulnerable children: The influence of multiple risk factors. Health Serv Res. 2006 Apr;41(2):507–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ngui EM, Flores G. Unmet needs for specialty, dental, mental, and allied health care among children with special health care needs: Are there racial/ethnic disparities? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007 Nov;18(4):931–49. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bethell C, Reuland CH, Halfon N, Schor EL. Measuring the quality of preventive and developmental services for young children: National estimates and patterns of clinicians’ performance. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6 Suppl):1973–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guerrero AD, Chen J, Inkelas M, Rodriguez HP, Ortega AN. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric experiences of family-centered care. Med Care. 2010 Apr;48(4):388–93. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ca3ef7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schuster MA, Duan N, Regalado M, Klein DJ. Anticipatory guidance: What information do parents receive? What information do they want? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000 Dec;154(12):1191–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.12.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guerrero AD, Rodriguez MA, Flores G. Disparities in provider elicitation of parents’ developmental concerns for US children. Pediatrics. 2011 Nov;128(5):901–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Montes G, Halterman JS. White-Black disparities in family-centered care among children with autism in the United States: Evidence from the NS-CSHCN 2005–2006. Acad Pediatr. 2011 Jul-Aug;11(4):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liptak GS, Benzoni LB, Mruzek DW, Nolan KW, Thingvoll MA, Wade CM, et al. Disparities in diagnosis and access to health services for children with autism: Data from the National Survey of Children’s Health. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008 Jun;29(3):152–60. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318165c7a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zuckerman KE, Boudreau AA, Lipstein EA, Kuhlthau KA, Perrin JM. Household language, parent developmental concerns, and child risk for developmental disorder. Acad Pediatr. 2009 Mar-Apr;9(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sices L, Feudtner C, McLaughlin J, Drotar D, Williams M. How do primary care physicians identify young children with developmental delays? A national survey. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003 Dec;24(6):409–17. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halfon N, Regalado M, Sareen H, Inkelas M, Reuland CH, Glascoe FP, et al. Assessing development in the pediatric office. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6 Suppl):1926–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuckerman KE, Mattox K, Baghaee A, Batbayar O, Donelan K, Bethell C. Pediatrician identification of Latino children at risk for autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2013 Sep; doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0383. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stein MT, Flores G, Graham EA, Magana L, Willies-Jacobo L. Cultural and linguistic determinants in the diagnosis and management of development delay in a four year old. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004 Oct;25(5 Suppl):S43–8. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200410001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuhlthau K, Nyman RM, Ferris TG, Beal AC, Perrin JM. Correlates of use of specialty care. Pediatrics. 2004 Mar;113(3 Pt 1):e249–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuhlthau K, Ferris TG, Beal AC, Gortmaker SL, Perrin JM. Who cares for Medicaid-enrolled children with chronic conditions? Pediatrics. 2001 Oct;108(4):906–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feinberg E, Silverstein M, Donahue S, Bliss R. The impact of race on participation in part C Early Intervention services. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011 Mar 8; doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182142fbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosenberg SA, Zhang D, Robinson CC. Prevalence of developmental delays and participation in Early Intervention services for young children. Pediatrics. 2008 Jun;121(6):e1503–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barfield WD, Clements KM, Lee KG, Kotelchuck M, Wilber N, Wise PH. Using linked data to assess patterns of Early Intervention (EI) referral among very low birth weight infants. Matern Child Health J. 2008 Jan;12(1):24–33. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clements KM, Barfield WD, Kotelchuck M, Wilber N. Maternal socio-economic and race/ethnic characteristics associated with early intervention participation. Matern Child Health J. 2008 Nov;12(6):708–17. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hosp JL, Reschly DJ. Disproportionate representation of minority students in special education: Academic, demographic, and economic predictors. Except Child 2004. 2004 Winter;70(2):185–99. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Minorities in special education briefing report. 2009 Apr; [Internet]. Available from: http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/MinoritiesinSpecialEducation.pdf.

- 70.Over-identification of students of color in special education: A critical overview. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.monarchcenter.org/pdfs/overidentification.pdf.

- 71.Cuccaro ML, Wright HH, Rownd CV, Abramson RK, Waller J, Fender D. Professional perceptions of children with developmental difficulties: The influence of race and socioeconomic status. J Autism Dev Disord. 1996 Aug;26(4):461–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02172830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin TW. White therapists’ differing perceptions of Black and White adolescents. Adolescence. 1993 Summer;28(110):281–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bailey DB, Jr, Hebbeler K, Spiker D, Scarborough A, Mallik S, Nelson L. Thirty-six-month outcomes for families of children who have disabilities and participated in Early Intervention. Pediatrics. 2005 Dec;116(6):1346–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sontag JC, Schacht R. An ethnic comparison of parent participation and information needs in Early Intervention. Exceptional Children. 1994 Mar-Apr;60(5):422. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, Morrissey JP. Access to care for autism-related services. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007 Nov;37(10):1902–12. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bailey DB, Jr, Skinner D, Correa V, Arcia E, Reyes-Blanes ME, Rodriguez P, et al. Needs and supports reported by Latino families of young children with developmental disabilities. Am J Ment Retard. 1999 Sep;104(5):437–51. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1999)104<0437:NASRBL>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Markus A, Rosenbaum S, Stewart A, Cox M. How medical claims simplification can impede delivery of child developmental services. The Commonwealth Fund; 2005. Report No.: 851. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sturm R, Ringel JS, Andreyeva T. Geographic disparities in children’s mental health care. Pediatrics. 2003 Oct;112(4):e308. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.e308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zuckerman KE, Perrin JM, Hobrecker K, Donelan K. Barriers to specialty care and specialty referral completion in the community health center setting. J Pediatr. 2013 Feb;162(2):409, 14.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Camp BW. Evaluating bias in validity studies of developmental/behavioral screening tests. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007 Jun;28(3):234–40. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318065b825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rydz D, Shevell MI, Majnemer A, Oskoui M. Developmental screening. J Child Neurol. 2005 Jan;20(1):4–21. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Squires J, Twombly E, Bricker D, Potter L. ASQ-3 user’s guide. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Glascoe FP. Collaborating with parents: Using Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS) to detect and address developmental and behavioral problems. Nashville, Tenn: Ellsworth & Vandermeer Press LLC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Laing SP, Hamhi A. Alternative assessment of language and literacy in culturally and linguistically diverse populations. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2003 Jan;34:44. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2003/005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Robins DL, Fein D, Barton ML, Green JA. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers: An initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001 Apr;31(2):131–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1010738829569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Canal-Bedia R, Garcia-Primo P, Martin-Cilleros MV, Santos-Borbujo J, Guisuraga-Fernandez Z, Herraez-Garcia L, et al. Modified Checklist for Autism in Roddlers: Cross-cultural adaptation and validation in Spain. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011 Dec;16(1342–1351):41. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1163-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Scarpa A, Reyes NM, Patriquin MA, Lorenzi J, Hassenfeldt TA, Desai VJ, et al. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers: Reliability in a diverse rural American sample. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013 Feb 6; doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1779-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Albores-Gallo L, Roldan-Ceballos O, Villarreal-Valdes G, Betanzos-Cruz BX, Santos-Sanchez C, Martinez-Jaime MM, et al. M-CHAT Mexican version validity and reliability and some cultural considerations. ISRN Neurol. 2012;2012:408694. doi: 10.5402/2012/408694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oesterheld JR, Haber J. Acceptability of the Conners Parent Rating Scale and Child Behavior Checklist to Dakotan/Lakotan parents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997 Jan;36(1):55, 63. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00018. discussion 63–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Magana S, Parish SL, Rose RA, Timberlake M, Swaine JG. Racial and ethnic disparities in quality of health care among children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012 Aug;50(4):287–99. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hillemeier MM, Foster EM, Heinrichs B, Heier B Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Racial differences in parental reports of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder behaviors. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007 Oct;28(5):353–61. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31811ff8b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mann EM, Ikeda Y, Mueller CW, Takahashi A, Tao KT, Humris E, et al. Cross-cultural differences in rating hyperactive-disruptive behaviors in children. Am J Psychiatry. 1992 Nov;149(11):1539–42. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.11.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Locke LM, Prinz RJ. Measurement of parental discipline and nurturance. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002 Jul;22(6):895–929. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.ADOS frequently asked questions. [Internet]. Available from: http://portal.wpspublish.com/portal/page?_pageid=53,84992&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL.

- 95.Unequal Treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Guyer B, Hughart N, Strobino D, Jones A, Scharfstein D. Assessing the impact of pediatric-based development services on infants, families, and clinicians: Challenges to evaluating the Healthy Steps program. Pediatrics. 2000 Mar;105(3):E33. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Healthy Families America. About us. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.healthyfamiliesamerica.org/about_us/index.shtml.

- 98.Nurse-Family Partnership: Proven results. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.nursefamilypartnership.org/proven-results.

- 99.Guerrero AD, Garro N, Chang JT, Kuo AA. An update on assessing development in the pediatric office: Has anything changed after two policy statements? Acad Pediatr. 2010 Nov-Dec;10(6):400–4. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Earls MF, Hay SS. Setting the stage for success: Implementation of developmental and behavioral screening and surveillance in primary care practice--the North Carolina Assuring Better Child Health and Development (ABCD) project. Pediatrics. 2006 Jul;118(1):e183–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Guidelines for cultural and linguistic adaptation of ASQ-3 and ASQ:SE. Paul Brookes Publishing Company; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pinto-Martin JA, Dunkle M, Earls M, Fliedner D, Landes C. Developmental stages of developmental screening: Steps to implementation of a successful program. Am J Public Health. 2005 Nov;95(11):1928–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.052167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pennsylvania child welfare training program developmental screening research project. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.pacwcbt.pitt.edu/ASQ.htm.

- 104.Bogin J. Enhancing developmental services in primary care: The Help Me Grow experience. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2006 Feb;27(Suppl1):S8–S12. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200602001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kaczorowski J, Andrew Aligne C, Halterman JS, Allan MJ, Aten MJ, Shipley LJ. A block rotation in community health and child advocacy: Improved competency of pediatric residency graduates. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2004;0;4(4):283–8. doi: 10.1367/A03-140R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Disparities in patient experiences, health care processes, and outcomes: The role of patient-provider racial, ethnic, and language concordance. 2004 Internet. Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2004/Jul/Disparities-in-Patient-Experiences--Health-Care-Processes--and-Outcomes--The-Role-of-Patient-Provide.aspx.

- 107.Rowland AS, Umbach DM, Stallone L, Naftel AJ, Bohlig EM, Sandler DP. Prevalence of medication treatment for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder among elementary school children in Johnston County, North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2002 Feb;92(2):231–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Miller TW, Nigg JT, Miller RL. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in African American children: What can be concluded from the past ten years? Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;2;29(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jarquin VG, Wiggins LD, Schieve LA, Van Naarden-Braun K. Racial disparities in community identification of autism spectrum disorders over time; metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, 2000–2006. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011 Apr;32(3):179–87. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31820b4260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bussing R, Schoenberg NE, Rogers KM, Zima BT, Angus S. Explanatory models of ADHD: Do they differ by ethnicity, child gender, or treatment status? J Emot and Behav Disord. 1998 Win;6(4):233–42. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Garcia S, Mendez-Perez A, Ortiz AA. Mexican American mothers’ beliefs about disabilities: Implications for early childhood intervention. Remedial Spec Ed. 2000;21:90. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kummerer SE, Lopez-Reyna NA, Hughes MT. Mexican immigrant mothers’ perceptions of their children’s communication disabilities, emergent literacy development, and speech-language therapy program. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2007 Aug;16(3):271–82. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2007/031). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]