Abstract

Carbon monoxide dehydrogenases (CODH) catalyze the reversible conversion between CO and CO2. Several small molecules or ions are inhibitors and probes for different oxidation states of the unusual [Ni-4Fe-4S] cluster that forms the active site. The actions of these small probes on two enzymes, CODH ICh and CODH IICh, produced by Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans have been studied by protein film voltammetry to compare their behavior and establish general characteristics. Whereas CODH ICh is, so far, the best studied of the two isozymes in terms of its electrocatalytic properties, it is CODH IICh which has been characterized by x-ray crystallography. The two isozymes, which share 58.3% sequence identity and 73.9% sequence similarity, show similar patterns of behavior with regard to selective inhibition of CO2 reduction by CO (product) and cyanate, potent and selective inhibition of CO oxidation by cyanide, and with regard to the action of sulfide, which promotes oxidative inactivation of the enzyme. For both isozymes, rates of binding of substrate analogues CN− (for CO) and NCO− (for CO2) are orders of magnitude lower than turnover, a feature that is clearly revealed through hysteresis of cyclic voltammetry. Inhibition by CN− and CO is much stronger for CODH IICh compared to CODH ICh, a property that has relevance for applying these enzymes as model catalysts in solar-driven CO2 reduction.

Keywords: Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, CO2 reduction, protein film electrochemistry

Introduction

Microbial carbon monoxide dehydrogenases (CODH) catalyze Reaction (1), the reversible interconversion between CO and CO2 and reactions that can be coupled to this process. Two types of CODH are found depending on whether the organism is an aerobe or anaerobe. Some aerobic and chemolithoautotrophic organisms, such as Oligotropha carboxidovorans,[1] use an enzyme with an active site containing Mo cytosine dinucleotide and Cu.[2] In contrast, anaerobic microorganisms such as Moorella thermoacetica (Mt),[3] Methanosarcina barkeri (Mb)[4] and Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans (Ch)[5] use an enzyme in which the CO2-activating site is a [Ni4Fe-4S] cluster.[6] Some anaerobic prokaryotes use CODH for use of CO as a sole source of carbon and electrons while others, such as methanogens and homoacetogens, couple the reduction of CO2 by CODH with acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS) via the Ljungdahl-Wood pathway to synthesize acetyl-CoA, which is then used for cell carbon synthesis.[7]

| (1) |

Genomic sequencing of Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans (Z-2901),[8] suggests that this organism, a thermophile, expresses at least five different CODHs. CODH ICh is thought to be involved in energy conversion in which CODH ICh extracts electrons by oxidation of CO and delivers these electrons to a hydrogenase, evolving H2. This proposal is based on the similarity of its genomic clusters with the well-studied CODH-hydrogenase complex from Rhodospirillum rubrum[9] and biochemical studies.[10] The role of CODH IICh remains unclear, although it has been the subject of several crystal structure determinations.[6, 11] CODH IIICh combines with ACS to perform acetyl-CoA synthesis[12] and CODH IVCh is suggested to be associated with oxidative stress.[8] The biological role of CODH VCh remains unclear.

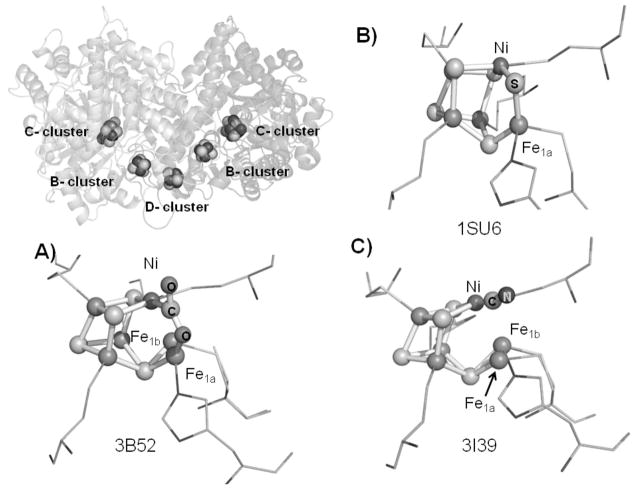

Both CODH ICh (125kDa) and CODH IICh (129kDa) are dimers sharing sequence identity and similarity of 58.3% and 73.9% respectively. Crystal structures of CODH IICh show that the active site (called the C-cluster) is a [Ni-4Fe-4S] cubane-like cluster that contains a ‘dangling’ Fe atom as shown in Figure 1.[6, 11] Additional [4Fe-4S] clusters, specifically two ‘B-clusters’ (one in each subunit) and a ‘D-cluster’ (which is at the subunit interface, coordinated by two cysteines from each subunit), relay electrons between the C-cluster and electron acceptors/donors, e.g., ferredoxin, outside the enzyme (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The overall structure of CODH IICh and different structures of the active sites (C-cluster): (a) −600 mV with CO2, (b) CO-reduced CODH IICh, (c) −320 mV with cyanide. The dangling Fe-atom in the active site is found in two positions, labeled Fe1a and Fe1b, respectively. The PDB codes are shown in each case.

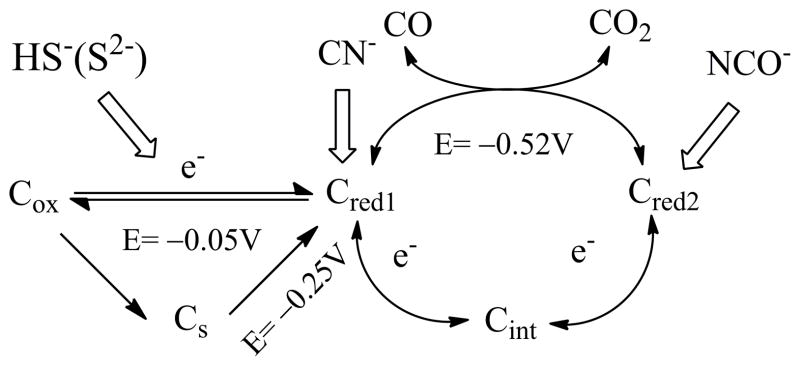

Based on previous studies of CODH mechanisms from different microorganisms,[13] the catalytic cycle is shown in Scheme 1. The Cox state is catalytically inactive and EPR-silent. One-electron reduction of Cox yields Cred1 which is active and displays a characteristic EPR signal with gav~ 1.8 in different species of CODH.[14] Reaction with CO converts Cred1 to Cred2 which shows an EPR spectrum with gav~1.86 (CODH ICh) and gav~1.84 for CODH IICh.[5] An EPR-silent intermediate Cint must be formed transiently as the active site is cycled back by one-electron transfers.

Scheme 1.

The catalytic cycle of CODH ICh and different catalytic states inhibited by small molecules. Cs is the sulfide-inhibited state.

Previous studies by protein film electrochemistry (PFE) have demonstrated the superb efficiency with which CODH ICh catalyzes reaction (1).[15] Voltammograms obtained in the presence of both CO2 and CO cut across the zero-current axis at values expected for the thermodynamic value for the particular CO2/CO mixture based upon a standard potential of approximately −520 mV at pH 7.0. The voltammetry has provided a particularly illuminating picture of the way in which different small molecules, carbon monoxide, cyanide (CN−), cyanate (NCO−), and hydrogen sulfide (HS−/H2S) act as inhibitors for different states of the active site engaged in the catalytic cycle, and a summary of those results is included in Scheme 1. Cyanide (isoelectronic with CO) mainly targets the Cred1 state whereas cyanate (isoelectronic with CO2) targets Cred2. Sulfide behaves differently and appears to react with CODH to form an oxidized inactive state that is similar to Cox but has greater redox stability (it is reactivated at a more negative potential). The results of sulfide inhibition studies may account for the discrepancies involved in early crystal structures and spectroscopic evidence.[6, 11b, 16]

Those PFE studies were carried out on CODH ICh.[15b] Given the greater structural information on CODH IICh, the greater uncertainty regarding its physiological role, and the fact that CODH IICh is also being used as a model system for semi-conductor-based photosynthetic CO2 reduction, it is now timely to compare and contrast the behavior of CODH ICh and CODH IICh. As described in this paper, we are able to identify key similarities between the two enzymes, helping us to consolidate our understanding of this important class of enzyme.

Results

Cyclic voltammetry of CODH ICh and CODH IICh and product inhibition by CO

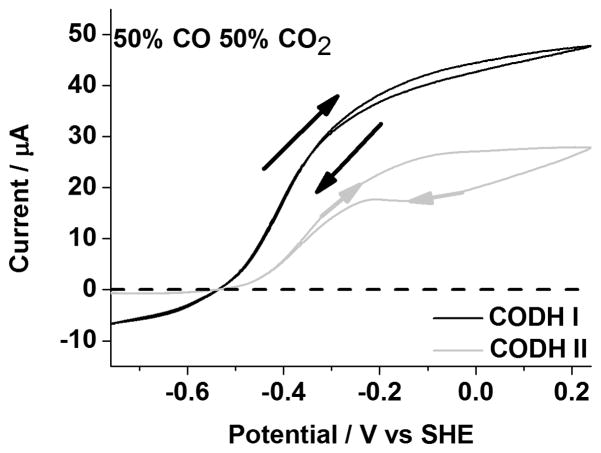

Figure 2 compares cyclic voltammograms of CODH ICh and CODH IICh measured over the potential range −0.76 V to 0.24 V under a mixture of 50% CO and 50% CO2. The positive electrocatalytic current corresponds to CO oxidation and the negative electrocatalytic current corresponds to CO2 reduction. The absolute values of the currents cannot be converted to true rates without knowing the accurate electroactive coverage of each enzyme; instead, the voltammograms provide, uniquely, the relative rates of catalysis when driven in either direction. Overlay of currents in each scan direction shows that the electrocatalysis is at steady state on the timescale of the scan, and the turnover rate is simply adjusting to the changing driving force; on the other hand, any observation of hysteresis indicates that other reactions, slow compared to catalysis but fast compared to the potential scan rate, are changing the rate of catalysis. In both cases, CODH ICh and CODH IICh give rise to reversible electrocatalysis: the voltammograms intersect the zero-current line at approximately −0.52 V (pH=7), close to the thermodynamic value expected for a 50/50 gas mixture. This result confirms the efficiency of electrocatalysis for both isoenzymes, in stark contrast to chemically synthesized CO2 reduction catalysts that require a large overpotential.[17] At high potentials the enzymes convert slowly to the inactive state Cox, and, judging from the size of the re-activation peak appearing around −200 mV, more inactivation has occurred for CODH IICh compared to CODH ICh during the cycle at 2 mVs−1. However, whereas CODH ICh shows high activity for CO2 reduction, the reduction current for CODH IICh is barely observable and much smaller than observed in the absence of CO (Figure 4, vide infra), suggesting that (CO) inhibition is much stronger for CODH IICh. Accordingly, the KM values for CO2 reduction and KI values for CO product inhibition were measured by chronoamperometry at two potentials, −560 mV and −760 mV, as described recently for CODH ICh.[15b] The results, analyzed by Lineweaver-Burk plots are shown in Table 1. In terms of the KM value for CO2 reduction, there are no significant differences between CODH ICh and CODH IICh and little dependence on potential (both potential values lie in the range driving CO2 reduction). The high KM values in each case (6–8 mM) indicate weak binding of CO2 to the active site. In contrast, the KI values for CO product inhibition vary considerably between the two potentials and are far higher (8-fold) for CODH ICh. The potential dependence of CO inhibition was previously interpreted in terms of CO binding much more tightly to Cred1 compared to Cred2.[15b] We now see that the same trend is observed for CODH IICh, but inhibition is very much stronger for this isozyme.

Figure 2.

Voltammograms of CODH ICh and CODH IICh under 50% CO and 50% CO2. Conditions: 25 °C, 0.2 M MES buffer (pH=7.0), rotation rate, 3500 rpm and scan rate, 2 mV sec−1

Figure 4.

Inhibition of CODH ICh and CODH IICh by cyanide under 100% CO2. An aliquot of KCN stock solution (giving a final concentration of 1mM in the electrochemical cell) was injected during Scan 2. Note that a more negative potential (by approximately 70 mV) is required to reactivate CODH IICh. Conditions: 25 °C, 0.2 M MES buffer (pH=7.0), rotation rate, 3500 rpm and scan rate, 1mV sec−1.

Table 1.

Summary of Km and KI values at two different potentials used to drive CO2 reduction by CODH ICh and CODH IICh

| Potential | −560mV | −760mV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KM (CO2) (mM) | KI (CO) (μM) | KM (CO2) (mM) | KI (CO) (μM) | |

| CODH ICha | 8.1±2.1 | 46 | 7.1±0.7 | 337 |

| CODH IICh | 8.0±1.6 | 5.4 | 6.0±1.0 | 84.5 |

data cited from ref [15b]

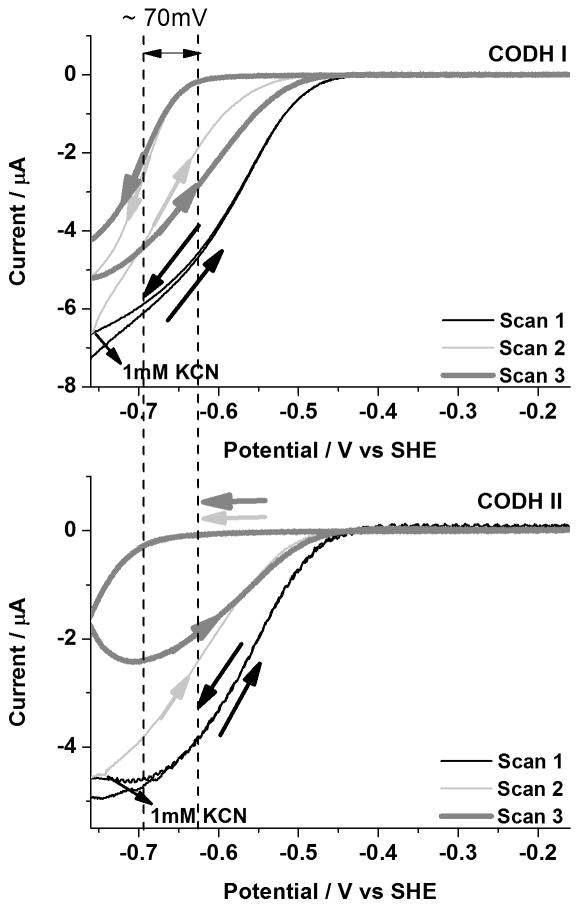

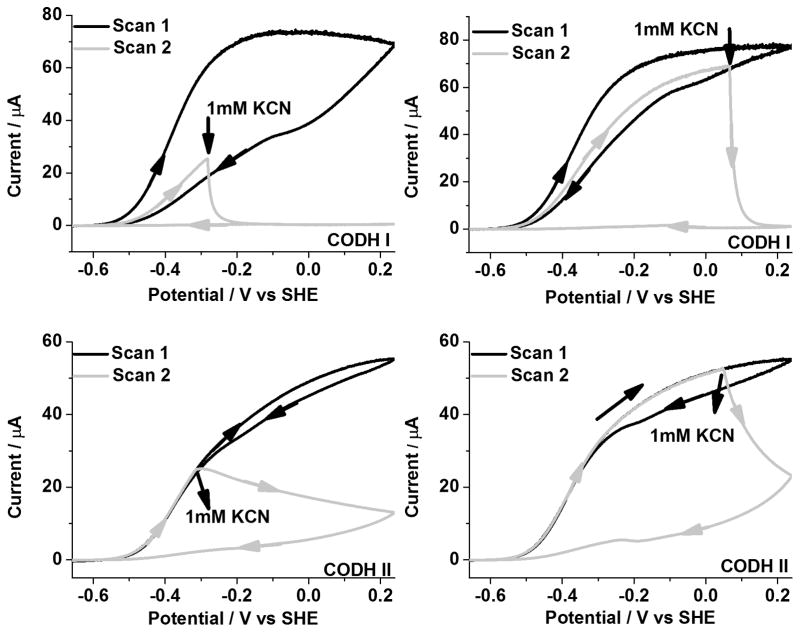

Inhibition by cyanide

Slow cyclic voltammograms (1 mVs−1) of CODH ICh and CODH IICh to determine how CN− affects CO oxidation under 100% CO are shown in Figure 3. In each case, an aliquot of CN− solution was injected (to give a final concentration of 1 mM in the cell) at two different oxidizing potentials. Injection at −280 mV corresponds to the region in which the Cred1 state normally dominates whereas injection at +80 mV corresponds to the potential region where the Cox state is formed very slowly. Clearly, inhibition of CODH IICh by CN− is much slower than for CODH ICh although both isozymes become fully inhibited. The enzyme remains inactive during the subsequent scan to potentials < −500 mV. The small oxidation feature observed after addition of CN− to CODH IICh at high potential probably corresponds to activation of the very small amount of Cox that was formed before CN− addition.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of CODH ICh and CODH IICh by cyanide under 100 % CO. An aliquot of KCN stock solution (giving a final concentration of 1mM in the electrochemical cell) was injected during Scan 2. Conditions: 25°C, 0.2 M MES buffer (pH=7.0), rotation rate, 3500 rpm and scan rate, 1mV sec−1.

Figure 4 shows cyclic voltammograms in which cyanide is injected instead during CO2 reduction under 100% CO2. Like CODH ICh, CODH IICh is also inhibited by cyanide in the potential region where the Cred1 state dominates. However, a more negative potential (by approximately 70 mV) is required to reductively reactivate CODH IICh (CN− is released by Cred2) implying that the Cred1/Cred2 binding differential is about an order of magnitude higher (tighter binding) for CODH IICh. As discussed later, this observation correlates with the stronger CO product inhibition displayed by CODH IICh.

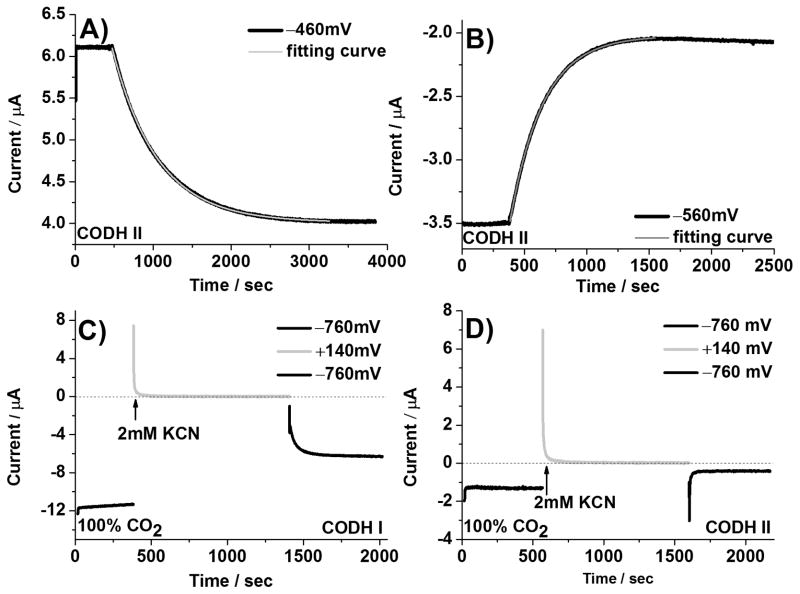

Cyclic voltammetry provides excellent qualitative insight into inhibitor binding and release, but the time and potential regimes are convoluted. Controlled potential chronoamperometry was therefore used to compare the rates of inactivation by CN− (association, primarily targeting the Cred1 state) and reductive re-activation (release of CN− as Cred1 converts to Cred2) at fixed potential values. The final concentration of CN− in each case was 0.5 mM, although some evaporation occurred during the longer-time experiments. Half-lives for CODH ICh and CODH IICh at different potentials are summarized in Table 2 and representative chronoamperometric results for CODH IICh under conditions in which the current is due to either CO oxidation or CO2 reduction are shown in Figure 5 (A, B). Similar results were obtained for CODH ICh. In both cases, the half-time for inhibition by cyanide does not depend greatly on potential until a very reducing potential is applied (the half-times are all around 1–5 minutes) although there is a greater variation for CODH IICh.

Table 2.

Comparison of half-times for inactivation by CN− (0.5 mM) and re-activation for CODH ICh and CODH ICh

| CODH ICh | CODH IICh | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential/mV vs SHE | tinact(1/2)/sec | tre-act(1/2)/sec | tinact(1/2)/sec | tre-act(1/2)/sec |

| +140 | 83±15 | 130±25 | ||

| −460 | 95±15 | 307±75 | ||

| −560 | 95±15 | still inhibited | 161±16 | still inhibited |

| −660 | 73±15 | 143±10 | ||

| −760 | 64±10 | 19±7 | 54±3 | ≪ limit of detection |

Figure 5.

Chronoamperometric measurements of the inactivation (Figure 5A and B) and re-activation (Figure 5C and D) rate of cyanide-inhibited CODH ICh and CODH IICh. The inactivation rate of CODH IICh by cyanide was measured at −460mV (CO oxidation, Figure 5A) and −560mV (CO2 reduction, Figure 5B). A final concentration of 0.5 mM cyanide in the electrochemical cell was used to measure the half-life time for inactivation. Cyanide release from CODH IICh (Figure 5D) at −760mV is much faster than the instrumental response. Conditions: 25 °C, 0.2 M MES buffer (pH=7.0), and rotation rate, 3500 rpm.

To measure reductive re-activation, the potential was first poised at −260 mV (in the CO oxidation potential window) in the presence of 0.5 mM KCN for 10 minutes in order to fully inactivate (inhibit) the enzyme and then stepped to three different potentials in the potential window of CO2 reduction. It was difficult to observe any re-activation current upon switching to −560 mV but fast recoveries were observed at more negative potentials. Typical experiments for CODH ICh and CODH IICh are shown in Figure 5 (C, D). For CODH ICh the re-activation at −760 mV occurs with a half-time of approximately 19 seconds, whereas for CODH IICh re-activation is immediate (i.e. within the detection time of the instrument and obscured by the current spike).

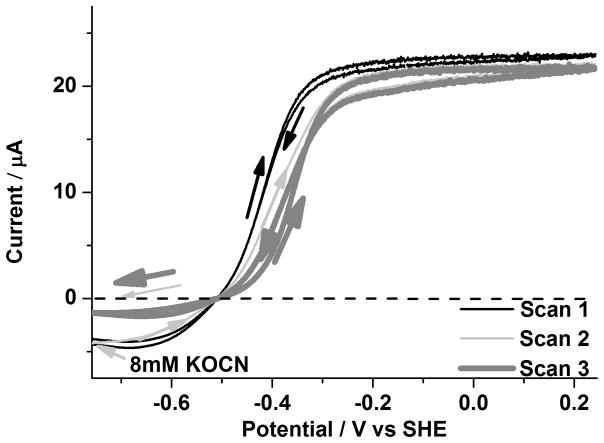

Inhibition by cyanate

We recently reported the inhibition of CODH ICh by cyanate, which is isoelectronic with CO2.[15b] The observations of full inhibition of CO2 reduction activity, slight inhibition of CO oxidation activity (a positive shift in the oxidation wave potential) and intensification of the magnitude of the Cred2 EPR signal relative to that of Cred1 at a constant potential led to the proposal that NCO− targets the Cred2 state. We therefore carried out experiments to measure cyanate binding at CODH IICh. An aliquot of cyanate solution (giving a final concentration of 8mM) was injected at −760mV under 20% CO and 80% CO2. The results, shown in Figure 6, were very similar to that observed for CODH ICh.[15b] A further experiment to determine the dissociation constant for NCO− inhibition at −760 mV gave a value of 3.3 mM for CODH IICh compared with 1.90 mM for CODH ICh.[15b]

Figure 6.

Inhibition of CODH IICh by cyanate (8 mM final concentration). An aliquot of KOCN stock solution was injected into the cell at −760 mV at the beginning of Scan 2 under 20% CO and 80% CO2. Conditions: 25 °C, 0.2 M MES buffer (pH=7.0), rotation rate, 3500 rpm and scan rate, 2mV sec−1.

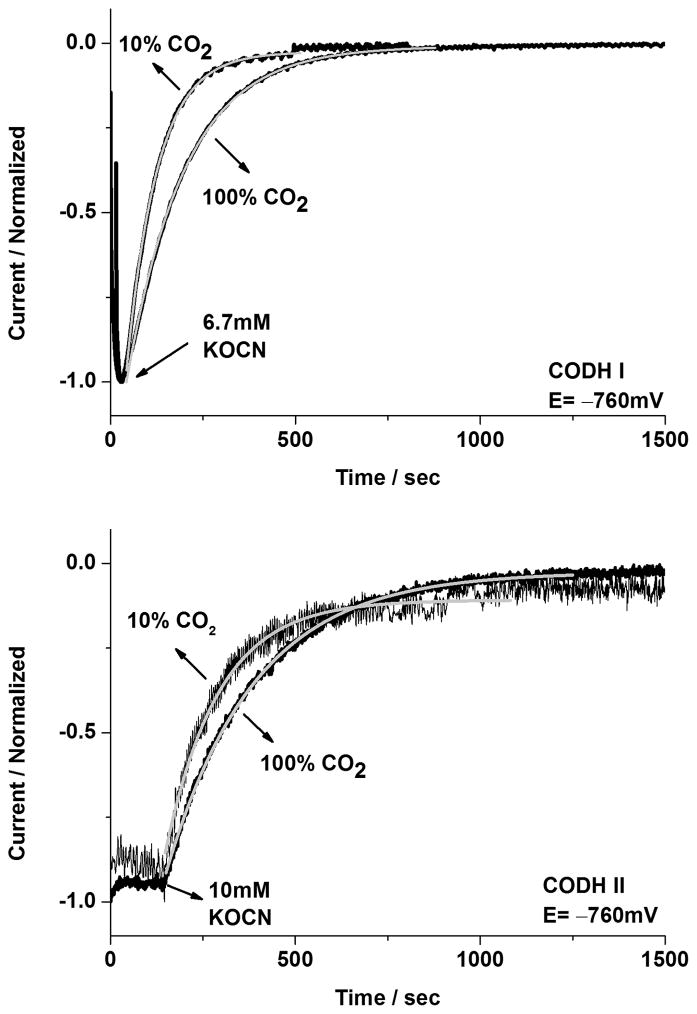

In order to elucidate how cyanate reacts with CODH ICh and CODH IICh, chronoamperometry was undertaken to measure the half-times for inactivation and reactivation in CODH ICh and CODH IICh respectively. Two methods were used: first, the potential was poised at −160mV in the presence of 6.7 mM cyanate for 10 min. (no inhibition is observed at this potential) before stepping the potential to two different values, −560mV or −760mV respectively, where inhibition occurs. The second method was to inject cyanate directly at these potentials and measure the half-time of the subsequent reaction. The current dropped to almost zero in either case. Some results for the injection experiments are shown in Figure 7. The half-time for inactivation was approximately 90 seconds for CODH ICh and 270 seconds for CODH IICh when the cyanate was injected in both cases to a final concentration of 6.7 mM. The same experiment was then performed on each enzyme using a mixture of 10% CO2/90% Ar. (Figure 7) Longer half-times were observed at the higher concentration of CO2, for both CODH ICh and CODH IICh, consistent with NCO− being a competitive inhibitor.

Figure 7.

Investigations of the rate of inactivation of CODH ICh and CODH IICh by cyanate at −760 mV under different CO2 concentrations (10% CO2 or 100% CO2). The normalized current is shown in figures and the fit to a single exponential decay curve is represented in the light grey line. Injections of KOCN were made into the electrochemical cell to give final concentrations of 6.7 mM for CODH ICh (upper figure) and 10mM for CODH IICh (lower figure). Conditions: 25°C, 0.2 M MES buffer (pH=7.0), and rotation rate, 3500 rpm.

In contrast, it proved impractical to measure the half-time for re-activation that occurs when the potential is stepped from a negative value at which NCO− is bound, to a more positive potential that causes it to be released. For CODH IICh, like CODH ICh, after holding the potential at −760 mV for 10 min. in the presence of 6.7 mM cyanate, a potential step to −160 mV resulted in immediate re-activation (i.e. within 2 sec, a realistic deadtime for the experiment, which produces a current spike due to charging).

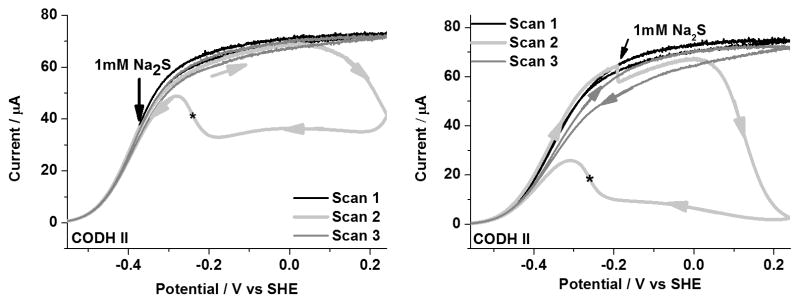

Inhibition by sulfide

The potential dependence of the inhibition of CODH ICh by sulfide, as described recently[15b] showed that sulfide (entering as H2S or HS−) does not inhibit the enzyme directly, but binds when the potential is increased, prompting the proposal that it forms an oxidized inactive state (we refer to this as Cs) analogous to Cox. Analogous behavior is observed for CODH IICh: as shown in Figure 8, inactivation commences at approximately 0 V and the re-activation potential of CODH IICh, −260 mV, is similar to the value obtained for CODH ICh.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of CODH IICh by sulfide. An aliquot of sodium sulfide stock solution (giving 1mM final concentration) was injected into the electrochemical cell during Scan 2. The asterisk indicates that the re-activation potential occurs at −260 mV, which is more negative that observed for Cox formed in the absence of sulfide. Conditions: 25°C, 0.2 M MES buffer (pH 7.0), rotation rate, 3500 rpm and scan rate, 1mV sec−1.

Discussion

The ease with which the kinetics of inhibitor binding and release are visualized by cyclic voltammetry is an important asset of the PFE approach. In contrast to the natural substrates, which must bind and be transformed at very high rates, the slow kinetics observed with the substrate analogues CN− and NCO− as well as sulfide, give rise to marked hysteresis.

The essential features of inhibition of CODH IICh by small molecule inhibitors, CO (product), CN−, NCO− and sulfide (HS− being the predominant species in solution) are now established to be analogous to the behavior observed with CODH ICh. This fact is important as it consolidates the emerging model for potential-dependent inhibition as laid out by PFE experiments. The potential dependences of CODH reaction with each inhibitor are similar for each isozyme and rates of binding or release are easily visualised. The reaction of CODH IICh with sulfide shows also that both isozymes form an oxidized, inactive sulfido species. The similar potential dependences for CO and CN− inhibition are fully consistent with the isoelectronic relationship between these two species and their selective binding to Cred1. Likewise, NCO− targets Cred2, fully in accordance with its isoelectronic/structural analogy with CO2.

The main differences between CODH ICh and CODH IICh relate to the inhibition by CO and CN− which is much more marked for CODH IICh. The strong CO inhibition of CO2 reduction may impact upon physiological function, since CODH IICh should be more suited to CO oxidation than CODH ICh.[5] Conversely, use of CODH IICh instead of CODH ICh as the catalyst in demonstrations of CO2 reduction by solar fuel (artificial photosynthesis) models requires that the CO product is efficiently removed as it is formed.[18]

The much slower rates of binding and dissociation of CN− (vs CO) and NCO− (vs CO2) are now established to be a general property of both isozymes, and must reflect important differences in how enzyme and active site interact with the true substrates, compared to their isoelectronic/isostructural counterparts. Distinctions can be made in terms of inhibitor binding involving two stages, transport in and out of the active site region and final tight binding to the active site: dissociation is the reverse of these processes.

For the first stage, an obvious issue concerns the acid-base properties of the inhibitors and the likely requirements for proton transfer steps during transport in and out of the enzyme (the natural substrates are neutral molecules) and to allow tight binding to occur. Under our experimental conditions, NCO−(pK 3.7) is present entirely as the conjugate anion and might require to be protonated to reach the active site, whereas CN−(pK 9.2) is present entirely as neutral HCN and would certainly require deprotonation in order to become a viable ligand for binding to a metal. The differences may also reflect polarity (CN has a higher dipole moment than CO; NCO− is dipolar but CO2 is quadrupolar).

For the second stage, the differences between inhibitors and substrates could reflect the difficulty or ease of forming the active site metal complexes, which involves steric constraints and geometry changes - processes that are crucial in catalysis and probably optimized for the true substrates. Several CODH crystal structures have recently been obtained that reveal how cyanide or a carbonyl group is bound to the Ni atom. The derivatives CN–CS/CODHMt[19] and CO(formyl)–ACDS/CODHMb[4] show a bent N–C–Ni structure with bond angle, ~114° and a bent O–C–Ni structure with bond angle, ~107°. In each of these structures the hydroxide ligand (water) is still bound to the dangling Fe atom. A comparison with the crystal structure of CO2–CODH IICh[6] shows that the N-atom in bent CN–CS/CODHMt and the O-atom in bent CO–ACDS/CODHMb overlay closely with one O-atom of the CO2 in CO2–CODH IICh. However, the C-atom in both CN–CS/CODHMt and CO–ACDS/CODHMb is displaced from that in CO2–CODH IICh. Amara and co-workers have recently re-evaluated the CN-bound structures,[20] suggesting reasons for the differences in structures and proposing, interestingly, that Cred2 may in fact contain a hydrido ligand attached to the Ni which would (like Cred1) be formally in the Ni(II) state: such a hydrido ligand would serve as electron reservoir (avoiding Ni(0)) and although not directly detectable by X-rays it could have a significant steric influence in Cred2. As such, in order to be effective as inhibitors, CN− or NCO− must not only form a bond to the Ni but also engage in a secondary interaction with either the OH− that is bound to the dangling Fe in Cred1 (and possibly displaced in Cred2) or the putative hydrido ligand proposed for Cred2. While these proposals remain speculative, secondary interactions of this type, while necessarily being very fast for the natural substrates, could greatly retarded for inhibitors due to steric restraints, accounting for the (at least) two-stage processes.[21]

In summary, our observations, now established as being applicable to both CODH ICh. and CODH IICh., establish that binding of inhibitors is specific to particular redox states, exactly in accordance with ground state isoelectronic and isostructural relationships, yet in each case orders of magnitude slower than catalytic turnover. The results offer valuable quantitative insight that is directly relevant to the catalytic mechanism of CO2 activation.

Experimental Section

Isolation, purification and specific activity measurement of CODH ICh and CODH IICh from Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans were carried out according to described procedures. [5], [21] The activity of CO oxidation was determined to be ~1300 μmole min−1 mg−1 for CODH ICh and ~1000 μmole min−1 mg−1 for CODH IICh respectively at 20°C using methyl viologen as an electron acceptor from CODH. All chemicals were of analytical or equivalent grade. The gases, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and argon were purchased from BOC. Potassium cyanide was obtained from Fisher chemicals, while sodium sulfide and potassium cyanate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Protein film electrochemical experiments were carried out as described recently in detail for CODH ICh.[15b] To form films of enzyme on the electrode, the quantities (2 μL) of a 1:3 mixture of CODH and polymyxin (Duchefa Biochemie or Sigma-Aldrich) by concentration were spotted onto the PGE electrode. The high concentration of buffer (0.2 M MES) is used to maintain the pH value due to the reaction with CO2. All potentials were adjusted to correspond with the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) using the scaling correction ESHE = ESCE + 241 mV at 25 °C. Cyclic voltammetry or chronoamperometry were performed with an Autolab PGSTAT20 electrochemical analyzer. All electrochemical experiments were performed in an anaerobic glove box (Vacuum atmospheres, O2 < 5ppm).

Acknowledgments

VW is grateful for financial support from Ministry of Education, Taiwan (R.O.C) through studying abroad scholarship. The authors thank BBSRC (Grants H003878-1 and BB/I022309), EPSRC (Supergen 5) and NIH (GM39451) for supporting research on enzymes in energy technologies. We also thank Dr. Elizabeth Pierce for enzyme preparation.

Footnotes

This article is dedicated to the late Ivano Bertini who passed away in July 2012. Professor Bertini was a pioneer of the use of NMR to study metal centres in proteins, a strong international voice for biological inorganic chemistry, and inspirational founder of the Society for Biological Inorganic Chemistry. A scientist with inimitable character and personality, he is sadly missed.

References

- 1.Meyer O, Schlegel HG. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1983;37:277–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobbek H, Gremer L, Kiefersauer R, Huber R, Meyer O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15971–15976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212640899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniel SL, Hsu T, Dean SI, Drake HL. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4464–4471. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4464-4471.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong W, Hao B, Wei Z, Ferguson DJ, Tallant T, Krzycki JA, Chan MK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9558–9563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800415105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svetlitchnyi V, Peschel C, Acker G, Meyer O. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5134–5144. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.17.5134-5144.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeoung JH, Dobbek H. Science. 2007;318:1461–1464. doi: 10.1126/science.1148481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragsdale SW, Pierce E. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteomics. 2008;1784:1873–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu M, Ren QH, Durkin AS, Daugherty SC, Brinkac LM, Dodson RJ, Madupu R, Sullivan SA, Kolonay JF, Nelson WC, Tallon LJ, Jones KM, Ulrich LE, Gonzalez JM, Zhulin IB, Robb FT, Eisen JA. Plos Genet. 2005;1:563–574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox JD, He YP, Shelver D, Roberts GP, Ludden PW. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6200–6208. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6200-6208.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soboh B, Linder D, Hedderich R. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:5712–5721. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Jeoung JH, Dobbek H. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9922–9923. doi: 10.1021/ja9046476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dobbek H, Svetlitchnyi V, Liss J, Meyer O. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5382–5387. doi: 10.1021/ja037776v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svetlitchnyi V, Dobbek H, Meyer-Klaucke W, Meins T, Thiele B, Romer P, Huber R, Meyer O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:446–451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304262101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bender G, Pierce E, Hill JA, Darty JE, Ragsdale SW. Metallomics. 2011;3:797–815. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00042j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindahl PA. Angew Chem. 2008;120:4118–4121. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:4054–4056. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Parkin A, Seravalli J, Vincent KA, Ragsdale SW, Armstrong FA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10328–10329. doi: 10.1021/ja073643o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang VCC, Can M, Pierce E, Ragsdae SW, Armstrong FA. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2198–2206. doi: 10.1021/ja308493k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Armstrong FA, Hirst J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14049–14054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103697108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Feng J, Lindahl PA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9094–9100. doi: 10.1021/ja048811g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ha SW, Korbas M, Klepsch M, Meyer-Klaucke W, Meyer O, Svetlitchnyi V. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10639–10646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar B, Llorente M, Froehlich J, Dang T, Sathrum A, Kubiak CP. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2012;63:541–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Woolerton TW, Sheard S, Reisner E, Pierce E, Ragsdale SW, Armstrong FA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2132–2133. doi: 10.1021/ja910091z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Woolerton TW, Sheard S, Pierce E, Ragsdale SW, Armstrong FA. Energy & Environ Sci. 2011;4:2393–2399. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kung Y, Doukov TI, Seravalli J, Ragsdale SW, Drennan CL. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7432–7440. doi: 10.1021/bi900574h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amara P, Mouesca JM, Volbeda A, Fontecilla-Camps JC. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:1868–1878. doi: 10.1021/ic102304m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seravalli J, Ragsdale SW. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6770–6781. doi: 10.1021/bi8004522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]