Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) is a variant of chronic cholecystitis. XGC remains difficult to distinguish from gallbladder cancer radiologically and macroscopically.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 63-year-old female was referred to our hospital because of a gallbladder tumor. Abdominal CT and MRI revealed a thickened gallbladder that had an obscure border with the transverse colon. FDG-PET showed a high uptake of FDG in the gallbladder. Therefore, under the preoperative diagnosis of an advanced gallbladder cancer with invasion to the transverse colon, a laparotomy was performed. Because adenocarcinoma was suspected based on the intraoperative peritoneal washing cytology (IPWC), cholecystectomy and partial transverse colectomy were performed instead of radial surgery. However, the case was proven to be XGC with no malignant cells after the operation.

DISCUSSION

In patients with gallbladder cancer who underwent surgery in our institute from 2000 to 2009, the prognosis after the operation of patients with only positive IPWC tended to be better than that of patients with definitive peritoneal disseminated nodules. It is true that in some cases, it is difficult to differentiate XGC from gallbladder carcinoma pre- and intra-operatively.

CONCLUSION

Surgical procedures should be selected based on the facts that there are long-term survivors with gallbladder cancer diagnosed with positive IPWC, and that some patients with XGC are initially diagnosed to have carcinoma by IPWC, as was seen in our case.

Keywords: Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis, Gallbladder cancer, Peritoneal lavage cytology

1. Introduction

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) is a variant of chronic cholecystitis characterized macroscopically by yellowish tumor-like masses in the wall of gallbladder, and microscopically by histiocytes engulfing lipids.1,2 Although XGC is well defined pathologically, it remains difficult to distinguish from gallbladder cancer radiologically and macroscopically.3 We herein report a case of XGC that was diagnosed as malignant by intraoperative peritoneal washing cytology (IPWC), which was difficult to definitively diagnose during the operation and was proven to be XGC without malignant cells after the operation. Additionally, we examined cases with gallbladder cancer in which malignant cells were detected by IPWC during a 10-year period at our institute.

2. Presentation of case

A 63-year-old female consulted a local hospital due to right upper abdominal pain. She underwent US and CT examinations, and received a diagnosis of gallbladder cancer invading into the transverse colon. She was referred to our hospital for a radical operation. She had received treatment for breast cancer at 60 years of age, and for ischemic heart disease at 62 years of age.

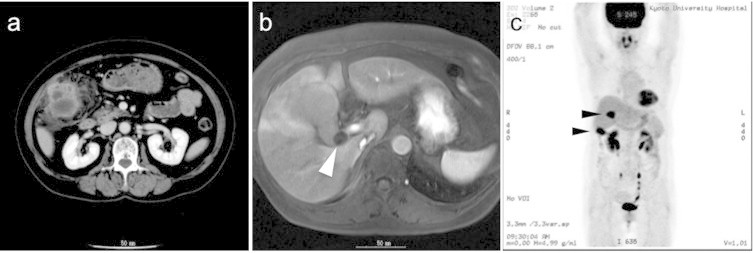

At our hospital, the patient's abdomen was soft and flat. She no longer showed abdominal pain and tenderness. The results of laboratory evaluations were as follows: white blood cell count, 4800/mm3; CRP, 0.3 mg/dl; CA19-9, 42 IU/l and CEA, 1.3 ng/ml. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT revealed a tumor-like formation at the fundus of the gallbladder, characterized by irregular thickening of the gallbladder wall (Fig. 1a). The borders between the tumor and the liver, the transverse colon and the abdominal wall were obscure. Furthermore, the fatty tissue around the tumor was dirty. Apparent lymphadenopathy and ascites were not detected. Abdominal MRI showed multiple gallbladder stones, one of which seemed to be incarcerated in the neck of the gallbladder (Fig. 1b). FDG-PET revealed the strong uptake of FDG at both the body of the gallbladder and in the liver bed (Fig. 1c). Although there remained the possibility of acute cholecystitis or XGC, these evaluations were consistent with gallbladder cancer that invaded directly into the abdominal wall, the transverse colon and the liver bed.

Fig. 1.

(a) Abdominal CT revealed an enhanced gallbladder with a thickened wall. (b) MRI detected a gallstone in the neck of the gallbladder (arrowhead). (c) FDG-PET revealed increased uptake of FDG at both the fundus of the gallbladder and the hepatic medial segment adjacent to the gallbladder body (arrowheads).

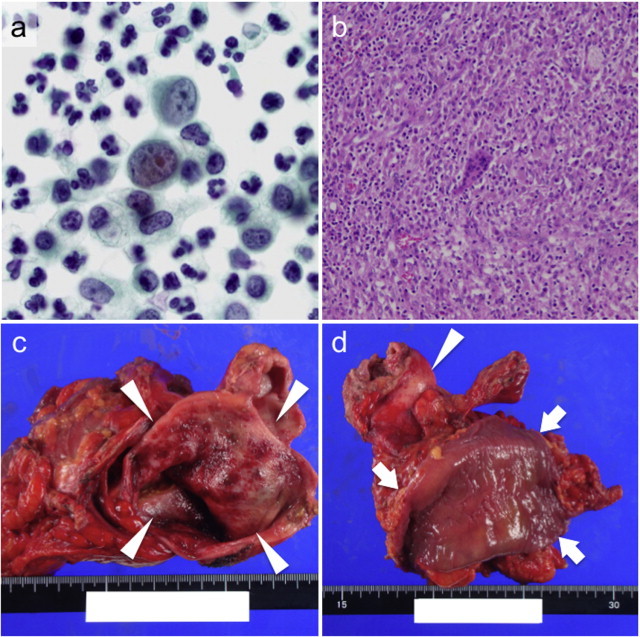

Under a diagnosis of advanced gallbladder cancer, surgery was performed. The surgical findings showed a small amount of ascites, and the hardened gallbladder adhered to the transverse colon. The IPWC samples obtained from both the right subhepatic cavity and Douglas’ pouch revealed the existence of severe dysplastic cells among a large number of neutrophils. These dysplastic cells had a high nucleocytoplasmic ratio, with distinct nucleoli and chromatin-rich nuclei that were unevenly localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2a). The findings suggested poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (class V). Despite a lack of definitive nodules of peritoneal dissemination, we diagnosed highly advanced gallbladder cancer and decided that there was no indication for extended radical surgery. However, to control the inflammation, we performed a cholecystectomy and partial transverse colectomy.

Fig. 2.

(a) Papanicolaou staining of the peritoneal washing cytology demonstrated the existence of severe dysplastic cells among a large number of neutrophils, suggesting poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. (b) HE staining showed a granuloma with massive neutrophil infiltration, giant cells and necrosis in the resected gallbladder wall, along with the accumulation of foamy histiocytes, indicating xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. No malignant cells were detected in the whole gallbladder. (c) The mucosa of the resected gallbladder had evidence of hemorrhage, and several small yellow polypoid lesions. The arrowheads indicate the lumen of the gallbladder. (d) Although the gallbladder (indicated by the arrowhead) adhered firmly to the transverse colon (arrows), the colon mucosal lumen was intact. The arrowhead indicates the gallbladder.

The macroscopic findings of the resected samples showed the extremely hardened wall of the gallbladder with multiple cholesterol stones. One of them was incarcerated in the neck of the gallbladder. The mucosa of the gallbladder had evidence of hemorrhage and several small yellow polypoid lesions (Fig. 2c). Although the gallbladder adhered firmly to the transverse colon, the colon mucosal lumen was intact (Fig. 2d). All of the resected gallbladder was examined microscopically. The hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining showed a granuloma with massive neutrophil infiltration, giant cells and necrosis in the resected gallbladder wall, and accumulation of foamy histiocytes, indicating XGC (Fig. 2b). No malignant cells were detected in the whole gallbladder. Reactive fibroblasts with atypia were found in edematous fibrous tissue around the gallbladder. The XGC lesions had extended into not only the gallbladder wall, but also the liver and the muscularis propia of the transverse colon. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient discharged on the 21st postoperative day.

3. Discussion

XGC is one subtype of cholecystitis, originally reported by Weismann and McDonald in 1948.1 XGC is thought to be caused by an inflammatory response against bile juice leaked from the Rokitansky–Asshof sinus.2 As previously reported by numerous articles, it remains often difficult to differentiate XGC from gallbladder carcinoma by preoperative imaging, even using new modalities, or by the intraoperative findings.3,4 In our case, because of (1) the slightly elevated CA19-9 value, (2) the enhanced thickened gallbladder wall and the obscure border between the gallbladder and the transverse colon and the abdominal wall5 and (3) the extremely strong uptake of FGD in the gallbladder,6–8 we made a diagnosis of advanced gallbladder carcinoma rather than XGC. Furthermore, we confirmed the diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma because of the result of the IPWC, in spite of the difficulty in making a definitive diagnosis. To the best of our knowledge, there have been limited reports on XGC assessed as positive by IPWC. We speculated that the suspected malignant cells detected by the IPWC in this case were reactive mesothelium, because the IPWC sample contained a large number of neutrophils, with a severe inflammatory background.

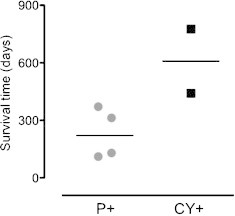

In order to examine the relationship between gallbladder carcinoma and IPWC, 67 surgical cases of gallbladder carcinoma treated at our institute from 2000 to 2009 were analyzed. Eleven cases (16.4%) were non-curative surgeries because of the intraoperative findings. Among these eleven cases, four cases had peritoneal dissemination forming definitive nodules (P+ group), and two cases had positive IPWC findings without definitive disseminative nodules (CY+ group). The median survival time of the P+ group was 221.5 days, while that of the CY+ group was 608.5 days (Fig. 3), suggesting the possibility of relatively longer survivors in cases with only positive peritoneal cytology without definitive disseminative nodules. Some articles have reported that the prognostic value of IPWC was limited in biliary tract cancer, or that the results of IPWC did not predict peritoneal dissemination.9–11 Although our examination analyzed extremely limited cases and did not include cases that underwent radical surgery with positive IPWC, our results suggested that positive IPWC alone was not a factor indicating the incurable nature of gallbladder cancer.

Fig. 3.

A scatter plot of the survival time after surgery in the patients with peritoneal disseminated nodules (P+; n = 4) and with positive peritoneal washing cytology without disseminated nodules (CY+; n = 2).

It can be difficult to select the surgical procedures in cases with positive IPWC findings. Therefore, IPWC might be better regarded as just a supportive examination. Considering the plausible finding of positive IPWC even in benign diseases, like in this case, and that possibility of long-term survivors of gallbladder carcinoma with positive IPWC without nodules, it might be desirable to perform cholecystectomy and resection of the directly invaded (or adhered) organs. In addition, XGC was reported to coexist with gallbladder carcinoma at a relatively high frequency of 7.5%.12 Therefore, a rapid and detailed pathological examination is needed after surgery.13,14

4. Conclusion

We herein reported a case of XGC that was difficult to differentiate from gallbladder carcinoma both pre- and intra-operatively. Surgical procedures should be selected based on the facts that there are long-term survivors with gallbladder cancer diagnosed with positive IPWC, and that some patients with XGC are initially diagnosed to have carcinoma by IPWC, as was seen in our case.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

T.I. is a primary author. All the authors of this article contributed to the study design, data collection, and data analysis.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Weismann R.E., McDonald J.R. Cholecystitis. A study of intramural deposits of lipids in twenty three cases. Arch Pathol. 1948;45:639–657. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert K.M., Parsons M.A. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:412–417. doi: 10.1136/jcp.40.4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spinelli A., Schumacher G., Pascher A., Lopez-Hanninen E., Al-Abadi H., Benckert C. Extended surgical resection for xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking advanced gallbladder carcinoma: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2293–2296. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i14.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casas D., Pérez-Andrés R., Jiménez J.A., Mariscal A., Cuadras P., Salas M. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: a radiological study of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21:456–460. doi: 10.1007/s002619900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martins P.N., Sheiner P., Facciuto M. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking gallbladder cancer and causing obstructive cholestasis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012;11:549–552. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(12)60223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makino I., Yamaguchi T., Sato N., Yasui T., Kita I. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking gallbladder carcinoma with a false-positive result on fluorodeoxyglucose PET. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3691–3693. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh T., Taniguchi H., Yamaguchi A., Kunishima S., Yamagishi H. Differential diagnosis of gallbladder cancer using positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-labeled fluoro-deoxyglucose (FDG-PET) J Surg Oncol. 2003;84:74–81. doi: 10.1002/jso.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mori A., Doi R., Yonenaga Y., Nakabo S., Yazumi S., Nakaya J. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis complicated with primary sclerosing cholangitis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:777–782. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4138-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajki T., Fujita T., Matsumoto I., Yasuda T., Fujino Y., Ueda T. Diagnostic and prognostic value of peritoneal cytology in biliary tract cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:842–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin R.C., Fong Y., DeMatteo R.P., Brown K., Blumgart L.H., Jarnagin W.R. Peritoneal washings are not predictive of occult peritoneal disease in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:620–625. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada S., Takeda S., Fujii T., Nomoto S., Kanazumi N., Sugimoto H. Clinical implications of peritoneal cytology in potentially resectable pancreatic cancer: positive peritoneal cytology may not confer an adverse prognosis. Ann Surg. 2007;246:254–258. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000261596.43439.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman Z.D., Ishak K.G. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981;5:653–659. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon A.H., Sakaida N. Simultaneous presence of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis and gallbladder cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:703–704. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh M., Sakhuja P., Agarwal A.K. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: a premalignant condition. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]