Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy (LVMR) is an effective method of management of functional disorders of the rectum including symptomatic rectal intussusception, and obstructed defaecation. Despite the technical demands of the procedure and common use of foreign body (mesh), the incidence of mesh related severe complications of the rectum is very low.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 63 year old woman presented with recurrent pelvic sepsis following a mesh rectopexy. Investigations revealed fistulation of the mesh into the rectum. She was treated with an anterior resection.

DISCUSSION

The intraoperative findings and management of the complication are described. Risk factors for mesh attrition and fistulation are also discussed.

CONCLUSION

Chronic sepsis may lead to ‘late’ fistulation after mesh rectopexy.

Keywords: Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy, LVMR complication, Rectal fistula, Mesh complication

1. Introduction

Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy (LVMR) is an effective method of management of functional disorders of the rectum including symptomatic rectal intussusception, and obstructed defaecation.1,2 Despite the technical demands of the procedure and common use of foreign body (mesh), the incidence of mesh related severe complications of the rectum is very low.

2. Presentation of case

A 63-year old lady presented with a three month history of progressively worsening recurrent pelvic pain. There was no associated rectal bleeding or change in bowel habits, but there had been intermittent rectal discharge. Each episode resolved quickly after commencement of broad spectrum antibiotics, but the episodes were becoming more frequent. Past medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus and a laparoscopic mesh rectopexy performed 24 months earlier.

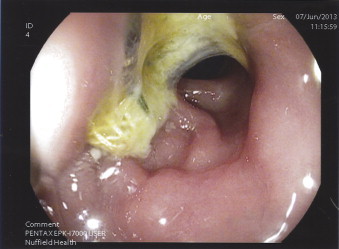

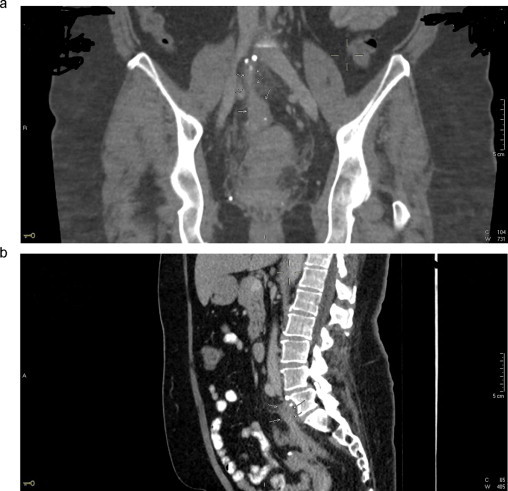

A CT scan during a previous episode showed chronic sepsis around the sacral promontory (in the area of the anchored tail of the radio-opaque mesh). General, abdominal and digital rectal examinations were unremarkable. Rigid sigmoidoscopy demonstrated normal rectal mucosa, but there was a local concentration of whitish discharge in the mid-rectum. Synthetic mesh material and a green suture were identified on flexible sigmoidoscopy (Fig. 1). 3-D reconstruction of the pelvic CT scan performed during the earlier episode of pain demonstrated a chronic pelvic inflammatory mass with radio-opaque mesh fistulation into the rectum (Fig. 2a and b).

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic picture showing the fistulated mesh and adjacent suture in the rectal lumen.

Fig. 2.

(a) and (b) Coronal & sagittal CT scans demonstrating the mesh fistula into the rectum.

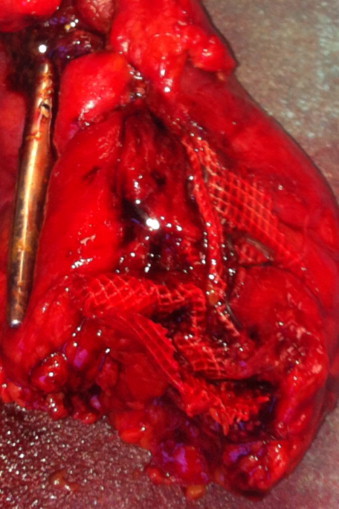

The findings were discussed with the patient, who elected to have a corrective procedure locally as soon as possible because of the persistent severe symptoms. At operation, a chronic pelvic inflammatory mass was found, involving the rectum, posterior wall of uterus and rectosigmoid colon. The tail of the mesh was anchored to the promontory, but the body of the mesh disappeared into the pelvic mass, that included a ‘bowed’ length of mobilized rectosigmoid. On complete dissection of the rectum, the other end of the mesh was found to emerge from within the rectal lumen proximal to its attachment to still sutured to the rectum. Further dissection revealed that, the mesh had fistulated into the distal sigmoid colon (Fig. 3), disappeared into the lumen of the rectum for a length before it emerged just proximal to its attachment to the rectal wall. An abscess cavity with approximately 10 ml of faeculent pus in the plane between the rectum and uterus was drained. An anterior resection was performed (excising both entry and exit fistula points), and a stapled anastomosis fashioned. A covering loop ileostomy was created. Postoperative abdominal wound infection cultured proteus sp. (similar to organisms cultured from the drained pelvic abscess).

Fig. 3.

Specimen showing the adherent mesh fistula into the rectum.

3. Discussion

While mesh rectopexy was described many years ago, it has gained popularity in the past 2 decades. This is because the successful application of minimally invasive access has made it possible to offer the procedure to the very elderly and other patient groups where the risks of a major laparotomy outweighed the benefits of the surgery.3,4 Nevertheless, the technical demands of the procedure in the confined bony pelvic cavity are recognized, and risk factors for failure (non-correction of functional symptoms) are well documented.2,5 Significant immediate, short-term and long-term rectal complications after mesh rectopexy have been reported, but on the whole are uncommon.

The most serious complications of LVMR are mesh related (infection, extrusion and erosion). While a systematic review reported similar rates of mesh complications and failure for biologic and synthetic LVMR,5 a larger systematic review of gynaecological organ prolapse mesh repair reported no mesh complications but greater failure rates for biologic mesh.6,7 Both biologic and synthetic meshes continue to be used in LVMR, and the true incidence of failure and mesh complications will surely emerge with time, from larger studies. It however seems logical to expect the tensile strength of a persistent synthetic mesh to be associated with low failure rates, though probably with more mesh related problems (than the biologic mesh).

Given that the mesh (synthetic, combined or biological) is anchored to or in close proximity to the rectum sutured during the procedure, the reported low incidence of rectal complications (strictures, erosions, etc.) ∼1% is remarkable. In this particular case, the operative and pathological findings suggest that the chronic friction caused by the persistent rubbing of the taut mesh against the adjacent bowed rectosigmoid may have been the cause.

4. Conclusion

While the choice of mesh in rectopexy is still largely surgeon dependent, the success rates associated with synthetic mesh (compared with biologic mesh) procedures must be weighed against the risk of mesh fistulation.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Funding

This is a case report. No funding was obtained.

Ethical approval

Consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Author contribution

Sole author.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.D’Hoore A., Cadoni’ R., Penninckx F. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for total rectal prolapse. Br J Surg. 2004;91(November (11)):1500–1505. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badrek-Al Amoudi A.H., Greenslade G.L., Dixon A.R. How to deal with complications after laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy: lessons learnt from a tertiary referral centre. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(June (6)):707–712. doi: 10.1111/codi.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boons P., Collinson R., Cunningham C., Lindsey I. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for external rectal prolapse improves constipation and avoids de novo constipation. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(June (6)):526–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01859.x. Epub 2009 April 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wijffels N., Cunningham C., Dixon A., Greenslade G., Lindsey I. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for external rectal prolapse is safe and effective in the elderly. Does this make perineal procedures obsolete? Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(May (5)):561–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Esschert J.W., van Geloven A.A., Vermulst N., Groenedijk A.G., de Wit L.T., Gerhards M.F. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for obstructed defecation syndrome. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(December (12)):2728–2732. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9771-9. Epub 2008 March 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smart N.J., Pathak S., Boorman P., Daniels I.R. Synthetic or biological mesh use in laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy – a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(June (6)):650–654. doi: 10.1111/codi.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jia X., Glazener C., Mowatt G., Jenkinson D., Fraser C., Bain C. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of using mesh in surgery for uterine or vaginal vault prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(November (11)):1413–1431. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]