Abstract

Background

Investigators have proposed the diagnostic value of a generalized subtype of specific phobia, with classification based upon the number of phobic fears. However, current and future typologies of specific phobia classify the condition by the nature of phobic fears. This study investigated the clinical relevance of these alternative typologies by: (1) presenting the prevalence and correlates of specific phobia separately by the number and nature of phobia types; and (2) examining the clinical and psychiatric correlates of specific phobia according to these alternative typologies.

Methods

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) is a nationally representative face-to-face survey of 10,123 adolescents aged 13–18 years in the continental United States.

Results

Most adolescents with specific phobia met criteria for more than one type of phobia in their lifetime, however rates were fairly similar across DSM-IV/5 subtypes. Sex differences were consistent across DSM-IV/5 subtypes, but varied by the number of phobic types, with a female predominance observed among those with multiple types of phobias. Adolescents with multiple types of phobias exhibited an early age of onset, elevated severity and impairment, and among the highest rates of other psychiatric disorders. However, certain DSM-IV/5 subtypes (i.e. blood-injection-injury and situational) were also uniquely associated with severity and psychiatric comorbidity.

Conclusions

Results indicate that both quantitative and DSM-IV/5 typologies of specific phobia demonstrate diagnostic value. Moreover, in addition to certain DSM-IV/5 subtypes, a generalized subtype based on the number of phobias may also characterize youth who are at greatest risk for future difficulties.

Keywords: epidemiology, child/adolescent, phobia/phobic disorders, anxiety/anxiety disorders, assessment/diagnosis

Introduction

Among the most prevalent of the anxiety disorders,[1–3] specific phobia is also often the first of these disorders to present over the course of development.[3–5] Moreover, prospective community studies have demonstrated that this condition is comorbid with other disorders of anxiety[6–8] and precedes several additional psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and substance use disorders.[6, 9, 10] Given its early onset and association with later psychopathology, investigators have suggested that the presence of specific phobia in youth may be an initial indication of vulnerability to subsequent pathology and impairment.[8,11] Indeed, a recent general population study of anxiety disorders in adolescents found that specific phobia was the first disorder to present among youth who displayed a complex and severe diagnostic profile. Nevertheless, results of this study also revealed a large subgroup of youth who were affected with specific phobia in isolation, and for whom rates of clinical severity and impairment were lower than all other subgroups.[12] In consideration of such data, specific phobia appears to be a highly heterogeneous condition.

Formal attempts to capture heterogeneity in specific phobia have relied upon classification by the nature of phobic fears. Accordingly, current and future taxonomies of specific phobia in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-IV/5;13, 14] include four major subtypes that reflect fear content: animal, natural environment, blood-injection-injury, and situational. Although a large number of clinical[15, 16] and general population studies of adults[17–21] have demonstrated that the phenomenology of specific phobia may vary substantially by subtype, other work indicates that its severity and clinical characteristics are more strongly predicted by the number of specific fears, irrespective of DSM-IV/5 subtype.[8, 22, 23] Toward this end, some authors have proposed the clinical value of a generalized subtype of specific phobia derived from the number of phobic fears.[23, 24]

However, studies that have investigated the number of specific phobias in young people are rare.[8,25] Likewise, few studies of youth have examined the prevalence and clinical characteristics of specific phobia by the DSM-IV/5 content-focused subtypes.[4, 25–27] Todate, only one community study of Mexican youth has examined specific phobia according to both the number and the nature of phobic fears.[25] Similar to adult work,[8, 22, 23] this investigation found strong associations between the number of fear types and levels of impairment, such that the risk for serious impairment increased systematically with the number of phobia types. However, because very few clinical correlates were evaluated in this study, additional work is needed to examine these alternative approaches to characterizing the heterogeneity of specific phobia in youth. Thus far, no general population studies of youth have examined the clinical value of both of these typologies with regard to a wide range of clinical characteristics as well as patterns of psychiatric comorbidity. The principal objective of this investigation was to evaluate the clinical relevance of both quantitative as well as DSM-IV/5 typologies of specific phobia by: (1) presenting the prevalence and correlates of specific phobia separately by the number as well as the nature of phobia types; and (2) examining the clinical and psychiatric correlates of specific phobia according to each of these typologies.

Materials and Methods

Sample and Procedure

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) is a nationally representative face-to-face survey of 10,123 adolescents aged 13–18 years in the continental United States.[28] Information concerning the NCS-A sampling strategy, participation rates, and instruments is reported in greater detail elsewhere.[2, 28] The survey was carried out in a dual-frame sample that consisted of a household subsample (n = 879) and a school subsample (n = 9,244). The adolescent response rate of the combined subsamples was 82.9%. Poststratification weighting corrected for minor differences in sample and population distributions of census sociodemographic and school characteristics.[28]

One parent/caregiver of each adolescent was mailed a self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) to collect information on adolescent mental and physical health, and other family- and community-level characteristics. The full SAQ was completed by 6,491 parents and an abbreviated SAQ was completed by 1,994 parents, yielding an overall conditional response rate of 83.3%. All recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

Measures

Diagnostic Assessment

A modified version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI), a fully structured interview of DSM-IV diagnoses, was administered to adolescents by trained lay interviewers.[29] The CIDI assessed lifetime disorders including specific phobia as well as other anxiety disorders (agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder [GAD], panic disorder [PD], separation anxiety disorder [SAD], social phobia [SoPh], posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]), mood disorders (bipolar disorder I and II [BPI/II], dysthymic disorder, major depressive disorder [MDD]), behavior disorders (oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], conduct disorder [CD]), attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]), and substance abuse/dependence disorders (alcohol or illicit drug). Parents/caregivers provided diagnostic information about MDD and dysthymic disorder, SAD, ADHD, ODD, and CD. Only adolescent reports were used to assess diagnostic criteria for mood and anxiety disorders based on prior work indicating that adolescents may be the most accurate informants concerning their emotional symptoms.[30] For behavior disorders, diagnostic data from both the parent and adolescent were combined and classified as positive if either informant endorsed the symptom/criteria for ODD and CD, and only parent reports were used for diagnoses of ADHD.[30, 31] Definitions of all psychiatric disorders adhered to DSM-IV criteria, and all diagnostic hierarchy rules were applied.

Lifetime Specific Phobia

In the CIDI screening module, six different types of fears were assessed among adolescents. Interviewers emphasized the principal fear defining each type by using a key phrase and provided examples of stimuli or situations representing each type. The six principal fear types assessed included animals (i.e. bugs, snakes, dogs, or other animals), still water/weather (i.e. a swimming pool, lake, or weather events, storms, thunder, or lightning), blood/injuries/medical experiences (i.e. going to the dentist or doctor, getting a shot or injection, seeing blood or injury, or being in a hospital or doctor's office), closed spaces (i.e. caves, tunnels, closets, or elevators), high places (i.e. roofs, balconies, bridges, or staircases), and flying (i.e. flying or airplanes). Adolescents who reported an immediate anxiety response or avoidance in the context of any of the six fear types were asked additional questions in the CIDI specific phobia module. Within the module, complete diagnostic information was obtained for each type of fear that was endorsed by adolescents. Diagnostic ratings for the six fear types were summed to derive a score reflecting the number of phobia types present among each adolescent (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 or more).1 Consistent with the DSM-IV/5, the natural environment subtype was derived from fears of either still water/weather or high places, and the situational subtype was derived from fears of either closed spaces or flying. The animal and blood-injection-injury subtypes were derived from their respective fear categories in the CIDI.[13, 14]

Age-of-onset (AOO) information for each fear type was obtained from adolescents using stepwise probing to enhance retrospective recall.[32] When multiple fears were endorsed, the minimum AOO value was used.

Global Clinical Features

Current Impairment, Days Out of Role, and Mental Health Quality

Adolescents who endorsed any specific fear in the past year were asked to rate the degree of impairment and disability they experienced during the worst month in the areas of household chores, school/work, family relations, and social life (Sheehan Disability Scale)[33]. The response scale ranged from 0 to 10 and included verbal anchors of none (0), mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), severe (7–9), and very severe (10). Consistent with previous investigations of anxiety disorders in the NCS-A,[12, 34] the maximum value endorsed by respondents across the four areas was used as an indication of past year impairment.2 An additional item assessed the total number of days in the past year that adolescents were unable to carry out their normal activities because of their fear(s). In a separate section of the CIDI, adolescents were asked to rate their overall mental health using a response scale that ranged from 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor).

Anxiety-Specific Clinical Features

Current Level of Fear

Adolescents who endorsed any specific fear in their lifetime were also asked to rate their current level of fear. When multiple fears were endorsed, youth rated the worst of these fears. The 5-point response scale included verbal descriptions depicting the current level of fear, 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Lifetime Treatment Contact for Specific Phobia or Other Anxiety Disorders

Adolescents were asked whether they had ever discussed their specific fear(s) with a professional (e.g. psychologists, general practitioners, counselors, school nurses, social workers, and other healing professionals). A dichotomous index of lifetime specific phobia treatment contact was generated by positively scoring cases who endorsed seeking treatment for specific phobia in their lifetime. Information from all other anxiety disorder sections was aggregated to create a parallel variable of lifetime treatment contact for other anxiety disorders.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were completed in the SAS software package using the Taylor series linearization method to account for the complex survey design.[2, 9, 35] Cross-tabulations were used to calculate estimates of prevalence, clinical features, and psychiatric comorbidity. The age-specific incidence curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to examine sex and age correlates of specific phobia by both the number of types and the nature of phobias; all presentations of specific phobia were examined in separate models.

To evaluate the clinical value of quantitative typologies of specific phobia, a series of separate multivariate regression analyses were conducted in which four dummy variables representing the number of phobia types (i.e. one, two, three, four or more) were entered simultaneously as predictors of clinical features and forms of psychiatric comorbidity. Parallel multivariate regressions also examined the linear effects of quantitative typologies by entering a single variable defined by the number of phobia types (i.e. 0–4). To evaluate the clinical value of the DSM-IV/5 subtypes of specific phobia, separate multivariate regression analyses were conducted in which variables representing each subtype of specific phobia (i.e. animal, natural environment, blood-injection-injury, and situational) were entered simultaneously as predictors of clinical features and psychiatric comorbidity. In each model, youth who did not meet criteria for specific phobia served as the reference group. For ordinal outcomes (Sheehan Disability Scale, Days Out of Role, Mental Health Quality, Level of Fear), multivariate ordinal logistic regression employing a logit function was used; for dichotomous outcomes (Treatment Contact for Specific Phobia, Treatment Contact for Other Anxiety Disorders), multivariate logistic regression was employed.

All multivariate models adjusted for significant sociodemographic variables (i.e. sex and/or age) and other anxiety disorders simultaneously. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) were the exponentiated values of multivariate logistic regression coefficients. Confidence intervals (95% CI) of aORs were calculated based on design-adjusted variances. The design-adjusted Wald χ2-test was used to examine the statistical significance of predictors based on two-sided tests evaluated at the 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Prevalence and Correlates

The lifetime prevalence, and sex and age correlates of specific phobia are presented by both number of phobia types and DSM-IV/5 subtype in Table 1. Approximately 15.1% (SE = 0.6%; N = 1,538) of adolescents met criteria for any specific phobia within their lifetime (results not shown). As is displayed, prevalence rates by the number of types of phobias were lowest for adolescents with only one type (2.6%) and highest for those with four or more types (4.5%). In particular, among those with any specific phobia, only a minority experienced a single specific phobia type (17. 2%), whereas most youth experienced multiple types of specific phobias in their lifetime (27.0% met criteria for two, 26.1% met criteria for three, and 29.5% met criteria for four or more; not displayed). By contrast, lifetime prevalence rates were fairly similar across subtypes, ranging from 11.0% for the natural environment subtype to 8.1% for the situational subtype.

Table 1. Prevalence estimates of lifetime specific phobia in the NCS-A by number and nature of phobia types (n = 10,123).

| Number of phobia types | DSM-IV/5 subtype | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| One | Two | Three | Four or more | Animal | Natural environment | Blood-injection-injury | Situational | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| % N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

|

| Total | 2.64 249 |

– | 4.08 401 |

– | 3.94 374 |

– | 4.45 514 |

– | 9.19 1,538 |

– | 10.98 1,129 |

– | 9.07 959 |

– | 8.06 840 |

– |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Female | 2.30 121 |

0.78 (0.51–1.21) |

4.20 222 |

1.07 (0.81–1.42) |

4.67 217 |

1.47 (1.13–1.90) |

5.63 329 |

1.75 (1.36–2.27) |

10.66 584 |

1.43 (1.18–1.75) |

12.29 664 |

1.34 (1.15–1.57) |

10.38 571 |

1.41 (1.16–1.72) |

9.82 515 |

1.63 (1.35–1.96) |

| Male | 2.96 128 |

1.00 | 3.96 179 |

1.00 | 3.24 157 |

1.00 | 3.32 185 |

1.00 | 7.69 392 |

1.00 | 9.59 465 |

1.00 | 7.68 388 |

1.00 | 6.27 325 |

1.00 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| 13–14 | 3.04 96 |

1.08 (0.68–1.74) |

4.40 169 |

1.21 (0.87–1.68) |

4.08 141 |

1.11 (0.69–1.80) |

5.19 226 |

1.41 (0.91–2.19) |

10.41 408 |

1.30 (0.91–1.85) |

11.81 472 |

1.18 (0.85–1.64) |

10.14 407 |

1.35 (0.98–1.88) |

9.08 351 |

1.28 (0.88–1.88) |

| 15–16 | 2.20 88 |

0.79 (0.44–1.42) |

4.01 140 |

1.09 (0.76–1.57) |

3.94 139 |

1.05 (0.76–1.45) |

4.16 185 |

1.08 (0.75–1.56) |

8.53 345 |

1.03 (0.82–1.28) |

10.41 408 |

1.00 (0.80–1.26) |

8.67 340 |

1.12 (0.84–1.50) |

7.43 305 |

1.02 (0.77–1.35) |

| 17–18 | 2.80 65 |

1.00 | 3.68 92 |

1.00 | 3.70 94 |

1.00 | 3.78 103 |

1.00 | 8.21 223 |

1.00 | 10.35 249 |

1.00 | 7.72 212 |

1.00 | 7.30 184 |

1.00 |

Note: Multivariate models adjusted for sex and age simultaneously; N, unweighted number of respondents; %, weighted percentage; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval of adjusted odds ratio.

Examination of sex and age correlates indicated that sex was significantly associated with specific phobia, such that females exhibited somewhat higher rates than did males. However, associations between sex and specific phobia were observed only among adolescents who experienced three or more types of phobias (three: aOR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.13–1.90; four or more: aOR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.36–2.27). Examination of this association by DSM-IV/5 subtypes indicated that females were consistently more likely than were males to experience all subtypes of specific phobia, ranging from 1.3 (95% CI = 1.15–1.57) to 1.6 (95% CI = 1.35–1.96) times as likely to meet criteria for the natural environment and situational subtype, respectively.

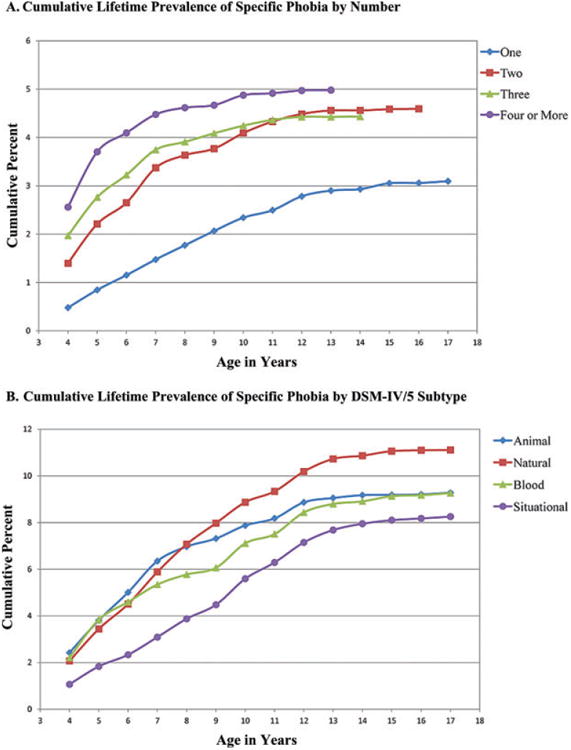

The age-specific cumulative prevalence curves for lifetime specific phobia are displayed by both the number of phobia types and DSM-IV/5 subtype in Fig. 1a and 1b. Analysis of differences in survival functions by number of phobia types indicated that all comparisons between single and multiple types of phobias were significantly different (all Ps < .0001). Median AOO values demonstrated a monotonic decreasing trend, with the lowest median age observed among those with the greatest number of phobia types (four or more: 4.0 years; three: 5.0 years, two: 6.0 years, one: 8.0 years). Because DSM-IV/5 subtypes were not mutually exclusive, it was not possible to test differences in these survival functions. However, inspection of the median AOO values suggested that both the animal (Md = 6.0) and blood-injection-injury subtypes (Md = 6.0) displayed the earliest AOO, followed by the natural environment (Md = 7.0) and situational subtypes (Md = 9.0).

Figure 1. Groups by (A) number of phobia types are mutually exclusive and (B) DSM-IV/5 subtypes are not mutually exclusive.

Clinical Features

Table 2 presents the unstandardized regression coefficients of multivariate models considering lifetime specific phobia by number of phobia types and DSM-IV/5 subtype. Multivariate models considering the number of phobia types, with one exception, showed that multiple phobias were significantly associated with several global and anxiety-specific clinical features, whereas single phobias often failed to predict these clinical indices. In most cases, the strongest associations with global clinical features were observed for youth affected with the highest number of phobia types (i.e. three or four or more). Although this pattern of association was not visible for all clinical features, examination of mean and proportion values indicated that clinical severity was often highest among those with the greatest number of phobia types. Adolescents with four or more phobia types reported disability in the moderate range (M = 4.0), the poorest mental health quality (M = 2.50), and reported being somewhat to very fearful (M = 3.37). In addition, although rates of treatment contact for specific phobia were universally low, they were most elevated among those with four or more types of phobias (10.6%) (descriptive statistics not shown, but available upon request). Further, the number of phobia types demonstrated significant linear effects in relation to all global and anxiety-specific clinical features (Ps < .05 to Ps < .001).

Table 2. Clinical features associated with lifetime specific phobia (n = 10,123).

| Global features | Anxiety-specific features | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Disabilitya

b (95% CI) |

Days out of role b (95% CI) |

Mental health quality b (95% CI) |

Level of fear b (95% CI) |

Specific phobia treatment contact b (95% CI) |

Any anxiety treatment contact b (95% CI) |

|

| Number of types | ||||||

| One | 0.25 (−0.02 to 0.52) |

0.37 (−0.06 to 0.79) |

0.05 (−0.07 to 0.17) |

0.35*** (0.18–0.53) |

0.22 (−0.14 to -0.58) |

0.24 (−0.06 to 0.54) |

| Two | 0.33** (0.11–0.54) |

0.29 (−0.02 to 0.59) |

0.17 (−0.00 to 0.34) |

0.17* (0.02–0.31) |

0.82*** (0.46–1.17) |

0.29* (0.00–0.58) |

| Three | 0.60*** (0.49–0.72) |

0.19 (−0.06 to 0.44) |

0.10 (−0.04 to 0.24) |

0.15** (0.05–0.26) |

0.68*** (0.34–1.02) |

0.24 * (0.01–0.48) |

| Four or more | 0.61*** (0.49–0.74) |

0.36*** (0.15–0.57) |

0.25** (0.07–0.42) |

0.44*** (0.26–0.62) |

0.76*** (0.53–0.98) |

0.26** (0.10–0.41) |

| Linear effect, | 171.90*** | 13.22* | 16.03** | 48.97*** | 55.58*** | 12.95* |

| Subtype | ||||||

| Animal | 0.01 (−0.12 to 0.15) |

0.07 (−0.18 to 0.33) |

0.02 (−0.13 to 0.16) |

0.18 (−0.05 to 0.41) |

−0.31 (−0.83 to 0.20) |

−0.37 (−0.78 to 0.03) |

| Natural environment | 0.12 (−0.03 to 0.28) |

0.04 (−0.27 to 0.35) |

0.08 (−0.05 to 0.21) |

−0.01 (−0.15 to 0.13) |

0.08 (−0.38 to 0.54) |

0.17 (−0.24 to 0.58) |

| Blood-injection-injury | 0.45*** (0.31–0.59) |

0.26 (−0.00 to 0.52) |

−0.00 (−0.12 to 0.10) |

0.07 (−0.14 to 0.28) |

1.39*** (0.59–2.19) |

0.42 (−0.08 to 0.92) |

| Situational | 0.16* (0.02–0.30) |

−0.02 (−0.29 to 0.26) |

0.15* (0.01–0.29) |

0.18** (0.06–0.30) |

0.59 (−0.06 to 1.24) |

0.40 (−0.10 to 0.91) |

Note: All models adjusted for adolescent sex and other anxiety disorders; Disability and days out of role ratings were limited to those adolescents who endorsed any specific fear in the past year (n = 3,671).

Sheehan Disability Scale;

, unstandardized regression coefficient; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval of regression coefficient.

P < .05;

P < .01;

P < .001.

Multivariate models of clinical features by DSM-IV/5 subtype revealed that severity and impairment were most often predicted by both the situational and blood-injection injury subtype. Adolescents with the situational subtype reported the poorest mental health quality (M = 2.47) and the highest fear level (M = 3.24), and adolescents with the blood-injection-injury subtype endorsed the greatest disability (M = 4.03) and the highest rates of treatment contact for specific phobia (11.4%) (descriptive statistics not shown, but available upon request).

Psychiatric Comorbidity

The lifetime comorbidity of specific phobia with other anxiety disorders is presented by number of phobia types and by DSM-IV/5 subtype in Table 3. After adjusting for sex and other anxiety disorders, multivariate models by the number of phobia types tended to demonstrate a pattern whereby associations with other anxiety disorders increased as the number of phobia types increased. This pattern was most visible for social phobia and agoraphobia, such that the rate of these conditions among adolescents with four or more phobia types was nearly fivefold the rate among those who did not meet criteria for specific phobia, and three- to fourfold the rate among those with only one type of phobia. In addition, the number of types of phobias consistently demonstrated significant linear effects in relation to all other forms of anxiety disorders (Ps < .05 to Ps < .001). Multivariate models of anxiety disorders by DSM-IV/5 subtype indicated that the situational and natural environment subtypes were most strongly associated with other anxiety disorders. In particular, the situational subtype was significantly associated with SAD (aOR = 2.48, 95% CI = 1.56–3.94) and SoPh (aOR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.26–3.47), whereas the natural environment subtype was significantly associated with agoraphobia (aOR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.01–2.04) and PTSD (aOR = 3.10, 95% CI = 1.89–5.06).

Table 3. Comorbidity of lifetime specific phobia with other anxiety disorders (n = 10,123).

| Separation anxiety disorder | Social phobia | Panic disorder | Agoraphobia | Posttraumatic stress disorder | Generalized anxiety disorder | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| % N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

% N |

aOR (95% CI) |

|

| Number of types | ||||||||||||

| One | 13.6 31 |

2.69** (1.37–5.28) |

6.9 26 |

1.43 (0.78–2.65) |

4.2 8 |

1.89 (0.86–4.13) |

3.6 12 |

1.50 (0.78–2.88) |

5.3 14 |

1.35 (0.51–3.56) |

1.4 6 |

1.36 (0.50–3.70) |

| Two | 14.0 54 |

2.28** (1.37–3.78) |

13.5 64 |

2.82*** (1.91–4.16) |

5.7 28 |

2.45** (1.38–4.37) |

3.1 18 |

1.12 (0.51–2.46) |

8.2 37 |

1.96** (1.23–3.14) |

2.7 10 |

2.40* (1.18–4.85) |

| Three | 22.2 63 |

4.20*** (2.81–6.29) |

13.3 52 |

2.45** (1.42–4.25) |

3.1 21 |

1.16 (0.66–2.03) |

5.9 27 |

1.89 (0.85–4.21) |

9.1 36 |

1.83* (1.11–3.00) |

2.1 9 |

1.52 (0.56–4.10) |

| Four or more | 16.1 101 |

2.20*** (1.52–3.19) |

23.0 111 |

4.69*** (3.10–7.08) |

7.1 38 |

2.54*** (1.46–4.42) |

14.8 93 |

5.15*** (3.50–7.60) |

11.0 51 |

1.88 (0.95–3.73) |

2.9 14 |

1.79 (0.98–3.25) |

| Linear effect, χ24 | 60.68*** | 87.97*** | 19.61*** | 79.34*** | 15.87** | 10.59* | ||||||

| Subtype | ||||||||||||

| Animal | 16.3 166 |

1.17 (0.77–1.79) |

16.3 174 |

1.32 (0.99–1.76) |

5.6 57 |

1.35 (0.60–3.05) |

8.9 110 |

1.36 (0.84–2.20) |

7.5 84 |

0.53* (0.31–0.93) |

2.2 22 |

1.01 (0.44–2.32) |

| Natural | 16.3 185 |

1.10 (0.65–1.89) |

16.6 198 |

1.52 (0.97–2.38) |

5.3 75 |

1.26 (0.65–2.39) |

8.7 131 |

1.44* (1.01–2.04) |

10.7 113 |

3.10*** (1.89–5.06) |

2.2 26 |

0.93 (0.42–2.02) |

| Blood | 16.3 95 |

1.12 (0.63–2.00) |

16.1 169 |

1.17 (0.73–1.91) |

5.9 65 |

1.53 (0.85–2.77) |

9.3 116 |

1.57 (0.89–2.78) |

9.1 94 |

1.17 (0.77–1.77) |

2.6 26 |

1.79 (0.86–3.72) |

| Situational | 20.6 165 |

2.48*** (1.56–3.94) |

19.7 158 |

2.09** (1.26–3.47) |

5.3 60 |

0.96 (0.55–1.69) |

10.2 113 |

1.61 (0.99–2.63) |

9.7 77 |

0.92 (0.50–1.69) |

2.6 25 |

1.13 (0.55–2.32) |

Note: All models adjusted for adolescent sex and other anxiety disorders (but the disorder of interest); youth who did not meet criteria for specific phobia served as the reference group. Reports based on adolescent CIDI interview (n = 10,123); N, unweighted number of respondents; %, weighted percentage; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval of odds ratio; χ2, Wald χ2 statistic.

P < .05;

P < .01;

P < .001.

With regard to other psychiatric disorders (results not shown but available upon request), after adjusting for sex and other anxiety disorders, examination of multivariate models by the number of phobia types indicated that rates of comorbidity were highest among those with the greatest number of phobia types. However, significant associations were only observed for mood disorders and ADHD. Similarly, the number of types of phobias displayed significant linear effects for mood disorders and ADHD (Ps < .05 to Ps < .001). Multivariate models by DSM-IV/5 subtypes revealed that particular subtypes were significantly associated only with behavior disorders, but not mood or substance use disorders. Most notably, the situational phobia subtype was significantly associated with CD(aOR=1.92, 95% CI =1.16– 3.18) and the blood-injection-injury phobia subtype was significantly associated with ADHD (aOR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.51–3.88).

Discussion

Summary of Findings

Our results provide novel evidence for quantitative typologies of specific phobia among adolescents, and further challenge the notion of circumscribed fear that has historically defined the disorder. In addition to affecting a large proportion of youth, adolescents with multiple types of phobias exhibited an early AOO, displayed elevated severity and impairment, and showed among the highest rates of other psychiatric disorders. Nevertheless, our data also offer some support for the content-focused DSM-IV/5 subtypes, suggesting that the clinical relevance of specific phobia varies as a function of both the number and the nature of fears.

Prevalence and Sociodemographic Characteristics

Converging with earlier work among adults[16, 22–24] and prior community samples of youth,[8, 25] investigation of prevalence rates by the number of phobia types revealed a non-normal distribution whereby a greater proportion of youth experienced multiple phobias relative to those who experienced only one type of phobia. Among those with any specific phobia, nearly 83% of adolescents met criteria for multiple phobia types in their lifetime. Such results suggest that specific phobia tends to generalize across a variety of content areas rather than remaining restricted to a specific fear domain. Consequently, the existence of multiple phobias may accurately describe a substantial segment of adolescents with this condition.

Examination of prevalence rates by DSM-IV/5 subtypes revealed relatively similar estimates across fear categories, affecting approximately 8–11% of all adolescents. Such results are in agreement with prior general population studies of adults[18, 22, 23] and youth[8,26, 27] that have evidenced only minor differences in prevalence rates across DSM-IV subtypes. Although rates of specific phobia were uniformly greater among females for all subtypes, it is notable that this sex discrepancy was unique to those who were affected with a greater number of phobia types, consistent with one previous community study of Mexican youth.[25] Similar variations in sociodemographic effects have been observed in prior studies of social phobia,[34, 36] with an overrepresentation of females evident only for generalized forms of the disorder. Such findings lend additional credence to the number of phobia types as an informative diagnostic feature. Conversely, the narrow range of prevalence estimates and similar sex ratio observed across DSM-IV/5 subtypes challenges whether this typology adequately reflects variability in the distribution and sociodemographic characteristics of the disorder.

Clinical Features and Psychiatric Comorbidity

Results also indicate that classification by number of phobia types provides clinically useful information concerning the phenomenology, degree of impairment, and psychiatric comorbidity associated with the disorder. Overall, the greatest distinction in clinical features and psychiatric comorbidity was evident for those with multiple types of phobias relative to those with only one type of phobia. Multiple phobias were associated with a variety of measures of severity, impairment, and psychiatric comorbidity, whereas single phobias showed less robust associations across these clinical indices. Although there were some variations, clinical difficulties were frequently most pronounced among those with the greatest number of phobias. Such results are comparable to previous general population studies that have found fear number to be a strong predictor of clinical severity, impairment, and/or psychiatric comorbidity.[8, 20, 22, 23, 25]

Also striking was the observation of differences in the timing of disorder onset by number of phobia types, with earlier ages of onset observed among adolescents who experienced a greater number of phobias. Though our results differ from one previous nationally representative study of adults that failed to find differences in the timing of disorder onset by fear number,[22] such discrepant findings may be due to the higher likelihood of retrospective reporting errors with longer time intervals since illness development.[37] Further, our data closely coincide with investigations that have demonstrated early disorder onset to be a marker for increased clinical severity[38] and psychiatric comorbidity.[39] Therefore, precocious and excessive fear may be one of the first indications of a more pervasive and disabling clinical course. Although such data are compelling, future prospective work is needed to better understand the degree to which early disorder onset may indeed predict a more serious prognosis for youth with specific phobia.

Although classification by number of phobia types demonstrated clinical value, analysis of clinical correlates by DSM-IV/5 subtypes also yielded evidence for variations by fear content. Although statistical tests of difference across subtypes were not possible due to their high degree of overlap, patterns of clinical characteristics are largely similar to previous work that has found distinctions between these parameters by subtype. For instance, the temporal sequence of onset observed in these data is consistent with a number of studies that have found onset of the situational phobias to follow onset of all other phobias.[15,16, 18,22, 24,40] Further, resembling earlier community studies,[21, 26] we found that the situational and blood-injection-injury subtypes were most strongly associated (and the animal subtype least strongly associated) with indices of severity and impairment. Examination of psychiatric correlates by DSM-IV/5 subtypes also provided some support for classification by the nature of fear, similar to prior work in youth.[27]

Clinical Implications and Limitations

The shortcomings of content-focused typologies of specific phobia were recognized and highlighted nearly four decades ago,[41] yet because these subtyping schemes do evidence some diagnostic value,[17] they have persisted in current and future taxonomies of mental illness. In view of the present study findings, however, classification of specific phobia based upon fear number is also clinically meaningful and warrants further consideration in diagnostic nomenclature. Moreover, in addition to the prognostic merit of current subtyping schemes, results of the current study also provide considerable evidence for quantitative typologies of the disorder. Therefore, rather than selecting one approach in place of another, these findings suggest that both characterizations may offer distinct and complementary information concerning diagnostic severity, impairment, and psychiatric comorbidity.

Likewise, although specific phobia is often excluded from clinical investigation,[42, 43] this study indicates that adolescents with certain DSM-IV/5 subtypes or multiple phobias may represent subgroups who are at risk for adverse functioning. Therefore, in addition to content-focused typologies, the application of a generalized specific phobia subtype may characterize a considerable proportion of youth who may benefit from additional clinical and empirical attention. As such, future research that examines youth with more disabling and pervasive forms of specific phobia will likely be worthwhile.

A number of study limitations are notable. First, though the current study provides preliminary evidence for the potential utility of a generalized subtype of specific phobia, no strict operational definition of this subtype was employed, nor did analyses examine the diagnostic accuracy or performance of a generalized subtype. Therefore, it will be important for future work to systematically examine the value of various clinical thresholds using statistics of agreement and/or efficiency to identify the most optimal definition of a generalized subtype. Second, although youth with the greatest number of phobia types often displayed the highest levels of clinical impairment and psychiatric disorder, it is important to note that there were several exceptions to this overall pattern. The observation of these data suggests that other biological and contextual factors (i.e. resistance to extinction, ability to avoid stimuli, frequency of exposure to stimuli) may also contribute to levels of disability, impairment, and psychiatric comorbidity. It will be important for future work to examine how such factors operate independently or in tandem to generate more complicated presentations among youth with specific phobia. Third, the cross-sectional design of the present study prohibits conclusive determinations concerning the temporal sequence of disorder onset. Additional prospective research is needed to replicate the current findings and provide longitudinal estimations of disorder onset across time. Fourth, although the CIDI provided diagnostic information on all DSM-IV/5 specific phobia subtypes, individual phobic fears of related content were aggregated into categories at the level of assessment in order to enhance study feasibility and reduce participant burden (e.g. bugs and snakes were assessed collectively as animal fears). Therefore, it was not possible to examine differences among phobic fears that were functionally similar in nature. Related, because individual fears of a similar type were assessed collectively, the quantitative index of specific phobia used in the current study provides only an approximation rather than a precise estimation of the total number of phobic fears. Nevertheless, the results observed in the current study are very similar to other work that has employed more nuanced assessments of specific phobia, suggesting that this index demonstrates strong nomological validity.[23] Finally, certain physiological responses, such as the vasovagal fainting response, have shown strong subtype specificity,[19] however this information was not universally acquired in the clinical interview.

Conclusion

These limitations aside, the present study is the first to examine the clinical relevance of a quantitative typology of specific phobia in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents. As well, it provides unique information on the diagnostic utility of DSM-IV/5 subtypes of specific phobia in these youth. Despite an accumulating amount of data and previous appeals in support of quantitative definitions of specific phobia,[8, 22–24] such proposals are currently absent from DSM-5 plans.[13] The present study suggests that multiple phobias may develop remarkably early and herald substantial psychopathology and impairment. Therefore coupled with content-focused assessment, quantitative approaches to the assessment and diagnosis of this condition may help identify those at greatest risk for future difficulties.

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (U01-MH60220) and the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01DA016558) with supplemental support from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; 044708), and the John W.Alden Trust. The NCS-A was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Examination of specific phobia prevalence rates by the number of phobia types indicated that a relatively small number of youth met criteria for five or six types of phobias (1.3%; SE = 0.14 and 0.55%; SE = 0.10, respectively). In order to reduce the likelihood of small cell sizes and imprecise estimates, youth who met criteria for four, five, or six types of phobias were considered together.

We also analyzed data with respect to the four individual areas of functional disability assessed by the Sheehan Disability Scale (i.e. household chores, school or work, family relations, and social life). Examination of these four separate domains yielded results that were largely similar to those using the single index of past year impairment (results available upon request).

References

- 1.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F. Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe—a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(4):357–376. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCSA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(7):768–768. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32(3):483–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Last CG, Perrin S, Hersen M, Kazdin AE. A prospective study of childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(11):1502–1510. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewinsohn PM, Zinbarg R, Seeley JR, et al. Lifetime comorbidity among anxiety disorders and between anxiety disorders and other mental disorders in adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 1997;11(4):377–394. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, et al. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(1):56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wittchen HU, Lecrubier Y, Beesdo K, Nocon A. Relationships among anxiety disorders: patterns and implications. In: Nutt DJ, Ballenger JC, editors. Anxiety Disorders. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 2003. pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bittner A, Goodwin RD, Wittchen HU, et al. What characteristics of primary anxiety disorders predict subsequent major depressive disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(5):618–626. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wittchen HU, Kessler RC, Pfister H, Lieb M. Why do people with anxiety disorders become depressed? A prospective-longitudinal community study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmelkamp PM, Wittchen HU. Specific phobias. In: Andrews G, Charney PJ, Sirovatka DA, Regier DA, editors. Stress-Induced and Fear Circuitry Disorders: Advancing the Research Agenda for DSM-V. 1st. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2009. pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burstein M, Georgiades K, Lamers F, et al. Empirically derived subtypes of lifetime anxiety disorders: developmental and clinical correlates in U.S. adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;80(1):102–115. doi: 10.1037/a0026069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association. [Accessed April 1, 2012];DSM-5 Development. 2010 http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=163.

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antony MM, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Heterogeneity among specific phobia types in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(12):1089–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipsitz JD, Barlow DH, Mannuzza S, et al. Clinical features of four DSM-IV-specific phobia subtypes. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(7):471–478. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeBeau RT, Glenn D, Liao B, et al. Specific phobia: a review of DSM-IV specific phobia and preliminary recommendations for DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(2):148–167. doi: 10.1002/da.20655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker ES, Rinck M, Turke V, et al. Epidemiology of specific phobia subtypes: findings from the Dresden Mental Health Study. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(2):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fyer AJ. Current approaches to etiology and pathophysiology of specific phobia. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(12):1295–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choy Y, Fyer AJ, Goodwin RD. Specific phobia and comorbid depression: a closer look at the National Comorbidity Survey data. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Depla MFIA, ten Have ML, van Balkom AJLM, de Graaf R. Specific fears and phobias in the general population: results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(3):200–208. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0291-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis GC, Magee WJ, Eaton WW, et al. Specific fears and phobias—epidemiology and classification. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:212–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, et al. The epidemiology of DSM-IV specific phobia in the USA: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2007;37(7):1047–1059. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofmann SG, Lehman CL, Barlow DH. How specific are specific phobias? J Behav Ther Exp Psy. 1997;28(3):233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(97)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjet C, Borges G, Stein DJ, et al. Epidemiology of fears and specific phobia in adolescence: results from the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):152–158. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency, comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment of specific phobia in adolescents. J Clin Child Psychol. 2000;29(2):221–231. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SJ, Kim BN, Cho SC, et al. The prevalence of specific phobia and associated co-morbid features in children and adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(6):629–634. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, et al. Design and field procedures in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18(2):69–83. doi: 10.1002/mpr.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grills AE, Ollendick TH. Issues in parent-child agreement: the case of structured diagnostic interviews. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2002;5(1):57–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1014573708569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green JG, Avenevoli S, Finkelman M, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: concordance of the adolescent version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0(CIDI) with the K-SADS in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent (NCS-A) supplement. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(1):34–49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knauper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, et al. Improving the accuracy of major depression age of onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1999;8:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, et al. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan disability scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27(2):93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burstein M, He JP, Kattan G, et al. Social phobia and subtypes in the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement: prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(9):870–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.SAS Institute. SAS/GIS 9.2: Spatial Data and Procedure Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruscio AM, Brown TA, Chiu WT, et al. Social fears and social phobia in the USA: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2008;38(1):15–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson EO, Schultz L. Forward telescoping bias in reported age of onset: an example from cigarette smoking. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14(3):119–129. doi: 10.1002/mpr.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carlson GA, Bromet EJ, Driessens C, et al. Age at onset, childhood psychopathology, and 2-year outcome in psychotic bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):307–309. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Comorbid mental disorders: implications for treatment and sample selection. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(2):305–311. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ost LG. Age of onset in different phobias. J Abnorm Psychol. 1987;96(3):223–229. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marks IM. The classification of phobic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1970;116(533):377–386. doi: 10.1192/bjp.116.533.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cartwright-Hatton S, Roberts C, Chitsabesan P, et al. Systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapies for childhood and adolescent anxiety disorders. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43(Pt 4):421–436. doi: 10.1348/0144665042388928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norton PJ, Price EC. A meta-analytic review of adult cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome across the anxiety disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(6):521–531. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253843.70149.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]