Abstract

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is a histological subtype of breast cancer that is frequently associated with favorable outcomes, as ~90% of ILC express the estrogen receptor (ER). However, recent retrospective analyses suggest that ILC patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy may not benefit as much as patients with invasive ductal carcinoma. Based on these observations, we characterized ER function and endocrine response in ILC models. The ER-positive ILC cell lines MDA MB 134VI (MM134) and SUM44PE were used to examine the ER-regulated transcriptome via gene expression microarray analyses and ER ChIP-Seq, and to examine response to endocrine therapy. In parallel, estrogen response was assessed in vivo in the patient-derived ILC xenograft HCI-013. We identified 915 genes that were uniquely E2-regulated in ILC cell lines versus other breast cancer cell lines, and a subset of these genes were also E2-regulated in vivo in HCI-013. MM134 cells were de novo tamoxifen resistant, and were induced to grow by 4-hydroxytamoxifen, as well as other anti-estrogens, as partial agonists. Growth was accompanied by agonist activity of tamoxifen on ER-mediated gene expression. Though tamoxifen induced cell growth, MM134 cells required FGFR1 signaling to maintain viability and were sensitive to combined endocrine therapy and FGFR1 inhibition. Our observation that ER drives a unique program of gene expression in ILC cells correlates with the ability of tamoxifen to induce growth in these cells. Targeting growth factors using FGFR1 inhibitors may block survival pathways required by ILC and reverse tamoxifen resistance.

Keywords: Breast cancer, lobular carcinoma, estrogen receptor, endocrine therapy, tamoxifen resistance

Introduction

Though ~80% of newly diagnosed breast cancers are considered invasive ductal carcinomas (IDC), less common subtypes are routinely identified. Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is the second most common histological subtype, accounting for 10–15% of breast cancer (1–4). ILC presents with unique clinicopathological features, including distinct issues with surgery and chemotherapy (reviewed by us (5)). ILC are frequently ER- and PR-positive; ~90% of ILC express ER, versus 60–70% of IDC (4,6,7). ILC are rarely HER2-positive and are less proliferative than IDC. Based on these biomarkers, ILC patients are excellent candidates for endocrine therapy, and should benefit from improved outcomes versus IDC patients. However, recent retrospective analyses suggest that ILC patients may have equivalent or worse outcomes than IDC patients, despite higher proportions of ER-positive patients that receive endocrine therapy (3,8–11).

Outcomes for ILC patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy are poorly understood, as data currently available are limited to retrospective analyses. Low numbers hinder analyses due to the lack of prospective inclusion of ILC patients. However, in a recent retrospective analysis of the adjuvant BIG 1-98 trial, Metzger-Filho and colleagues compared outcomes in IDC versus ILC patients (12). Among IDC patients (n=2599), the 8-year DFS confirmed the increased benefit for letrozole versus tamoxifen (HR 0.8) as previously reported. However, ILC patients (n=324) that received tamoxifen were much more likely to experience recurrence (HR 0.48). These data strongly suggest that ILC patients receive less benefit from adjuvant tamoxifen than IDC patients, and highlight the need for investigation in endocrine response and resistance specifically in ILC.

Studies of endocrine response in IDC benefit from the availability of extensively studied cell lines (e.g. MCF-7, T47D). However, only two ER-positive ILC cell lines have been reported in the literature: MDA MB 134VI (MM134) and SUM44PE (SUM44) (5). Minimal data exist regarding endocrine response in these models (13–15). Thus, we characterized ER function and endocrine response in both ILC cell lines and a unique in vivo model of ILC. We observed that ER regulates a unique gene set in ILC cells. Further, MM134 present with de novo tamoxifen resistance via recognition of tamoxifen as an agonist. However, FGFR1 may be necessary to maintain cell viability in the presence of tamoxifen. Based on recent clinical observations, improved understanding of endocrine response in ILC models is necessary to improve patient outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

MCF-7 and T47D (ATCC) were maintained as described (16). MM134 (ATCC) were maintained in 1:1 DMEM:L-15 (Life Technologies) +10% FBS. SUM44PE (Asterand) were maintained as described (17) +2% charcoal stripped serum (CSS). Cell lines are authenticated annually by PCR RFLP analyses at the University of Pittsburgh Cell Culture and Cytogenetics Facility, and confirmed to be mycoplasma-negative. Authenticated cells are in continuous culture for <6mo. Cells were hormone-deprived as described (16) in phenol red-free IMEM with 5%, 10%, or 2% CSS for MCF-7, MM134, and SUM44, respectively.

17β-estradiol (E2), tamoxifen free-base, 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT), and endoxifen (Bx) were obtained from Sigma. Lapatinib and lasofoxifene were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. All other compounds were obtained from Tocris Biosciences. E2, tamoxifen, 4OHT, Bx, and ICI were dissolved in ethanol; all other compounds were dissolved in DMSO.

Proliferation and viability assays

Cellular proliferation assays used the FluoReporter dsDNA quantitation kit (F2692, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cellular viability assays used CellTox Green (Promega) according to instructions. Fluorescence was assessed on a VictorX4 plate reader (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). For proliferation/viability assays, points/bars represent the mean of 6 biological replicates ± SEM.

RNA extraction and quantitative-PCR

RNA extractions used the Illustra RNAspin Mini kit (GE Health); cDNA conversion used iScript master mix (Bio-Rad), and qPCR reactions used Ssoadvanced SYBR green (Bio-Rad) on a CFX384 thermocycler (Bio-Rad), according to manufacturer's instructions. Primer sequences are available in Supplemental Document 1.

Gene expression microarrays

Hormone-deprived cells were treated for 3–24 hours with 1nM E2 or 0.01% EtOH in biological quadruplicate. RNA was harvested as above. cRNA synthesis/labeling was performed using the MessageAmp Premier Kit (Life Technologies), and cRNA was hybridized to U133A 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix) by the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Biomarkers Facility. Data processing is described in Supplemental Document 1; data is available in GEO as GSE50695.

MCF-7 data were obtained from the GEMS E2-regulation meta-signature (18). Probe level expression values were condensed as above. Median expression values across datasets were used for individual genes. T47D and BT474 data were from GSE3834 (19) and processed as above. Venn analyses were performed using gene symbols.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-Seq)

ChIP experiments were performed as described (20) with minor modifications. Hormone-deprived MM134 cells were treated with 1nM E2 or 0.01% EtOH for 45 minutes. Immunoprecipitation used ERα (HC-20) and rabbit IgG (sc2027) antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). DNA from six independent ChIPs was pooled for sequencing at Genome Quebec Innovation Center (McGill University). 50bp DNA sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform allocated >6×107 single-end reads per sample.

Output was mapped to the Human Reference Genome (hg18) by BWA (21). Peaks were called using MACS v1.4.2 (22), with a P-value cutoff of 10−5. Features of ER binding sites were mapped by CEAS (23) and BedTools (24). MCF-7 consensus ER binding sites represented the overlap of nine published data sets (25–29). Data is available in GEO as GSE51022.

Primary tumor xenograft HCI-013

Generation and maintenance of primary tumor xenografts (PDXs) was previously described (30). HCI-013 was established from a pleural effusion from a 53 year-old woman with metastatic ER+/PR+/HER2- ILC (also see Supplemental Document 1).

To evaluate growth, NOD-SCID mice were ovariectomized and/or supplemented with estradiol (1mg/pellet (31)) prior to tumor implantation; growth was assessed by caliper weekly. For estrogen deprivation studies, tumors were implanted in ovariectomized mice with estradiol supplementation. Upon tumors reaching 600–800mm3, mice received sham or pellet removal surgery; tumors were harvested after 2 or 5 days. Mice from the growth experiment above were crossed-over for pellet removal surgery; tumors were harvested after 10 days for this group. Upon tumor harvest, necrotic regions were excised and portions were formalin-fixed/paraffin-embedded or flash-frozen. IHC and Ki67 analyses are described in Supplemental Document 1. For gene expression studies, RNA was extracted from 20–30mg of pulverized frozen tissue using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen).

Nanostring gene expression analyses

Cells in culture were lysed using Buffer RLT + β-mercaptoethanol (Qiagen), with buffer volume normalized to total RNA. Xenograft tissue experiments used 100ng of purified RNA per sample. Lysates/RNA were assessed using the mRNA expression protocol on the nCounter platform (Nanostring) according to the manufacturer's instructions, using a custom codeset (see text). Cluster analyses utilized Multi Experiment Viewer v4.8.1 (32).

Supplemental methods

Additional methods and statistical considerations are described in Supplementary Document 1.

Results

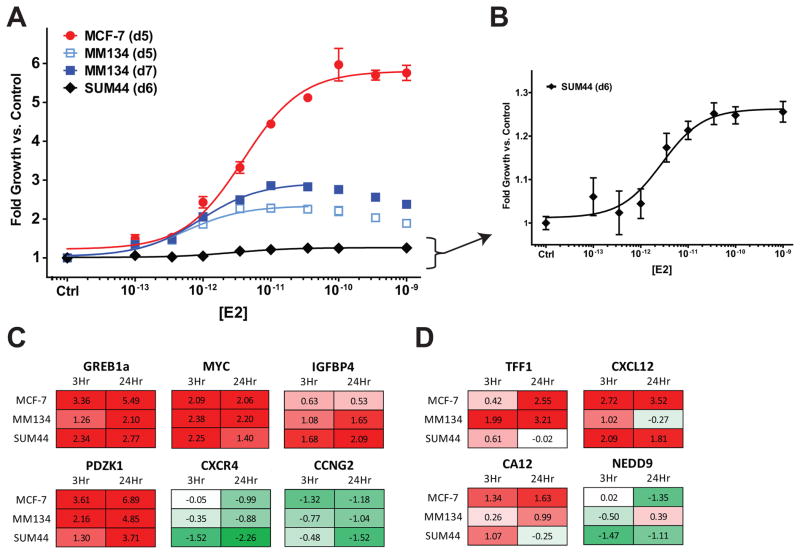

Estrogen induces growth and gene expression in ILC cells

To assess endocrine-responsiveness, MM134 and SUM44 cells were treated with E2 following hormone deprivation. E2 induces growth in both cell lines with similar potencies versus MCF-7 (EC50, 1–3pM) (Figure 1A, re-scaled for SUM44 in 1B). Though growth appeared to be induced less in MM134 (~2.5-fold) versus MCF-7(~6-fold), these data are consistent with slower basal growth for MM134 (data not shown).

Figure 1. E2 induces growth and gene expression in ILC cells.

(A), Proliferation at indicated time post-treatment. (B), Zoomed scale for SUM44. (C), (D), qPCR-based gene expression; mean log2 fold-vs-vehicle of 3 biological replicates. Red, increased expression; Green, decreased expression. (C), Genes similarly regulated, (D), genes differentially regulated in ILC cells versus MCF-7.

We measured the expression of ten well-established E2-responsive genes following 1nM E2 treatment for 3hr or 24hr. Six of ten genes were similarly regulated across cell lines (Figure 1C); for four genes, one ILC cell line showed differential regulation (Figure 1D). All expression changes were reversed by ICI (Supplemental Figure 1A), and were dose-responsive (Supplemental Figure 1B), suggesting that these effects are mediated by ER. Progesterone receptor (PR) mRNA was E2-induced in both ILC cell lines but was at detection limits (data not shown), consistent with their PR statuses (5). Taken together, the ER-positive ILC cell lines MM134 and SUM44 are endocrine-responsive at both the growth and transcriptional levels. Differential regulation of some target genes (e.g. TFF1/pS2) suggests that ER-regulated gene expression may be unique in ILC cells.

ER regulates unique genes in ILC cells

We performed microarray analyses with MM134 and SUM44 cells following treatment with 1nM E2 for 3 or 24 hours to assess global E2-mediated gene expression. A total of 6241 and 5364 genes were differentially expressed versus vehicle (fdr <0.05) at either timepoint in SUM44 or MM134, respectively (Supplemental Table 1); the majority were regulated in both cell lines (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. E2 regulates unique genes in ILC cells.

(A–D), Venn analysis of indicated gene sets; genes regulated at 3 and/or 24 hours included. (A), Experimental data for ILC cell lines. (B), Public data for IDC cell lines. (C), Union of IDC versus ILC. (D), Intersect of IDC versus ILC. (E), Validating ILC-E2 geneset in MM134 cells (Nanostring). Cells were hormone deprived and treated (0.1% EtOH or 1nM E2 ± 1μM ICI) for 3, 24, or 72 hours. Expression shown as log2 fold versus time-matched vehicle. ‘+’, common E2-regulated genes.

These data were compared to public data for three ER-positive IDC cell lines, MCF-7, T47D, and BT474. 7369 genes were E2-regulated in any IDC cell line (i.e., the union of differentially expressed genes), whereas only 383 genes were commonly regulated across all IDC cell lines (i.e., intersect) (Figure 2B). E2-regulated genes in ILC cells were compared to this union or intersect; a total of 915 genes were regulated by E2 specifically in the ILC cells (versus union, Figure 2C), including WNT4, SNAI1, and FOXO1. Of note, ~44% of ILC-specific genes were repressed vs <25% among other pair-wise comparisons (Supplemental Table 1). 254 genes were E2-regulated in all 5 cell lines (versus intersect, Figure 2D), including GREB1, IGFBP4, and CCNG2, and only 31 genes were IDC-specific, including PLK1 (Figure 2D) (Supplemental Table 1).

To evaluate ILC-specific E2-regulated genes, we selected the most induced and repressed ILC-specific genes, in addition to 8 commonly regulated genes, to yield 107 target genes (“ILC-E2 geneset”, Supplemental Table 2). E2-regulation and ER-dependency of these target genes was validated in MM134 (Figure 2E). E2-regulation was confirmed for 88/107 genes (82%), and subsequently reversed by ICI for 85/88 confirmed genes (97%), demonstrating ER-dependent regulation.

ILC-specific ER binding is primarily in distal intergenic regions

Genome-wide ER binding in MM134 was assessed by ChIP-seq. A total of 2556 E2-induced ER binding sites were observed. Overall, sites were enriched within 10kb of gene bodies (Figure 3A), consistent with IDC cell lines e.g. MCF-7 (33). We confirmed ER binding in MM134 cells at sites associated with E2-regulated genes (Supplemental Document 1). E2 induced binding at commonly regulated genes and ILC-specific genes including WNT4 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. E2 induces unique distal ER binding in MM134 cells.

(A), Localization of ER binding sites in MM134. Bolded/asterisk indicate q-value versus genome < 0.05. (B), ChIP-qPCR of ER binding sites in independent samples. NFERE, non-functional estrogen-response element. P-value for vehicle vs. E2 <0.05 for all sites except NFERE. Represents repeat experiments, ± SD of technical replicates. (C), MM134 binding sites versus consensus MCF-7 sites. (D), Localization of ER binding sites for specific/shared sites between MCF-7/MM134. Bolded/asterisk indicate q-value versus genome < 0.05.

MM134 ER binding sites were compared to a consensus of MCF-7 ER binding sites. Roughly half of MM134 binding sites were shared with MCF-7 (1384/2556, 54%, Figure 3C). MCF-7-specific sites (n=3855) and those common to both (n=1384) were similarly enriched in promoters within 10kb (13.0% and 11.1%, respectively, versus 6.0% expected; Figure 3D, top left). However, MM134-specific ER binding sites (n=1172) were not enriched in these regions, trending toward depletion (5.3%; Figure 3D, top left). A similar pattern emerged in downstream regions (Figure 3D, top right); MM134-specific sites were not enriched within 10kb downstream, while both common and MCF-7-specific sites were enriched. Further, whereas common and MCF-7-specific sites were enriched in intragenic regions (Figure 3D, bottom; 48.5% and 48.1% observed, respectively, versus 46.3% expected), MM134-specific sites were significantly depleted (43.1%).

Motif analysis showed that MM134-specific, MCF-7-specific, and common binding sites were enriched for estrogen response elements (EREs) and forkhead (FOXA1) sites (Supplemental Figure 2A). Co-factor motifs, including GATA1 and AP-2, were only enriched in common and MCF-7-specific sites and limited to ERE and forkhead sites in MM134-specific sites. Motif analyses were repeated using only distal ER binding sites, i.e. >20kb from genes (Supplemental Figure 2B). Co-factor sites were largely lost, and identifiable motifs were limited to ERE/forkhead; only EREs were enriched in distal MM134-specific sites. These observations suggest that ILC-specific E2-regulated gene expression may be modulated by distal sites regulated by unique co-factors in MM134 cells.

A unique in vivo model of ILC is E2-responsive

We evaluated two ER-positive PDXs: HCI-005, derived from a mixed ILC/IDC (30), and HCI-013, derived from an ILC. HCI-005 was found to be purely IDC, whereas HCI-013 was found to mimic clinical ILC (Figure 4A). We assessed HCI-013 growth in mice ±ovariectomy and ±E2-supplementation. E2-supplementation significantly decreased time to tumor detection and increased growth rate (Figure 4B); ovariectomy had no effect against E2-supplementation. Without E2-supplementation, ovarian estrogens promoted faster tumor formation, but resulting tumors grew slower than those in the absence of estrogens. These data demonstrate that HCI-013 tumors are an ER-positive, E2-responsive, in vivo ILC model.

Figure 4. Novel PDX HCI-013 is estrogen-responsive.

(A), 5μM sections of FFPE blocks from HCI-013 and HCI-005 stained as indicated. E-cadherin/p120 staining was previously described (40). (B), PDX growth in defined estrogen conditions. Lines represent individual tumors. Growth rates ±SD shown. (C), Ki67 under indicated estrogen conditions. (D), Differential gene expression; d5 sham surgery (+E2) vs d10 pellet removal (−E2) (q < 0.05) shown as log2 fold change (−E2 vs +E2). (E), Example genes identified in (D). Points represent mean ± SD.

HCI-013 proliferation (Ki67 IHC) and gene expression (ILC E2 geneset) were measured following estrogen-deprivation. Following initial establishment +E2, tumors were harvested following E2 pellet removal or sham surgery. No significant proliferation changes were observed following 2 or 5 days of estrogen deprivation; however, following 10 days of estrogen-deprivation, few cells are Ki67 positive (8%±4%; versus d5 +E2, p=0.0016). Representative images of Ki67 staining are included (Figure 4C). Expression of 32/107 genes (30%) (Figure 4D and Supplemental Table 3) was significantly different in tumors ±E2, including 27/99 ILC-specific genes and 5/8 common genes (examples shown in Figure 4E). These results demonstrate that HCI-013 proliferation is E2-regulated, and that ILC-specific genes identified in vitro are also regulated in vivo in an independent ILC model.

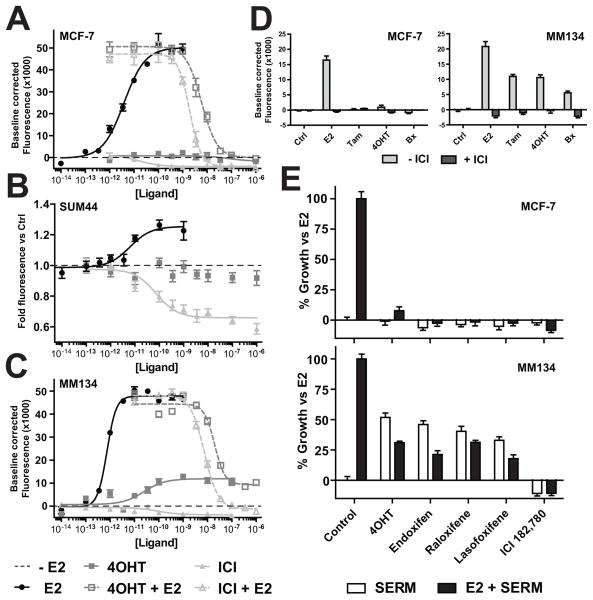

ILC cells are de novo tamoxifen resistant

We then assessed the efficacy of tamoxifen in MM134 and SUM44. E2-induced growth is completely blocked by both 4OHT and ICI in MCF-7 (Figure 5A). In SUM44 cells, 4OHT blocks E2-induced growth as previously described (13)(data not shown); 4OHT alone does not induce growth . However, ICI alone strongly suppressed growth (Figure 5B), suggesting that ligand-independent, ER-dependent pathways may regulate growth. In MM134 cells, ICI suppresses E2-induced growth. However, 4OHT only partially reverses E2-induced growth, and induces ~30% growth itself as a partial agonist (Figure 5C). This de novo tamoxifen resistance in MM134 cells may mirror clinical resistance to tamoxifen in some ILC tumors.

Figure 5. MM134 cells are de novo tamoxifen resistant.

(A–C), Hormone-deprived cells were treated as indicated. Proliferation was assessed 5 (MCF-7) or 6 days (MM134, SUM44) post-treatment. Dashed line indicates growth -E2. Anti-estrogen treatment was +100pM E2 where indicated. (D–E), Hormone-deprived cells were treated with 100pM E2 or 1μM anti-estrogen ± 1μM ICI (D), or 100pM E2 ± 1μM anti-estrogen (E). Proliferation assessed 6 days post-treatment.

We further investigated the partial agonist activity of 4OHT in MM134 cells. MCF-7 and MM134 cells were treated with ER ligands ± ICI. ICI blocked E2-induced growth in MCF-7, and no tamoxifen compound induced growth (Figure 5D, left). However, in MM134, E2, tamoxifen, 4OHT, and endoxifen all induced growth that was reversed by ICI (Figure 5D, right), demonstrating that tamoxifen-induced growth is via activation of ER.

Additional SERMs raloxifene and lasofoxifene, which belong to unique chemical classes versus tamoxifen (34), were also tested. Both SERMs blocked E2-induced growth in MCF-7; neither alone induced growth (Figure 5E, top). MM134 cells were growth-induced by both raloxifene and lasofoxifene, neither of which completely suppressed E2-induced growth, consistent with partial agonist activity (Figure 5E, bottom). Toremifene, a tamoxifen analog, induced growth only in MM134 (data not shown). Conversely, the ICI analog RU 58668 completely reversed E2-induced growth and had no agonist activity (data not shown). Thus agonist activity may be a class effect of SERMs, but does not extend to SERDs.

Tamoxifen induces gene expression as an agonist in ILC cells

We hypothesized that tamoxifen would also regulate gene expression as an agonist in MM134 cells, and assessed the ILC-E2 geneset following treatment with E2, 4OHT, or ICI. Gene clustering revealed two dominant groups, strongly E2-induced genes (Figure 6A, red bar, n=22) and E2-repressed genes (light green bar, n=42). E2-induced genes could be divided in to two sub-clusters. In the larger sub-cluster (orange bar, n=17) 4OHT acted as an antagonist, similar to ICI, and this included classical ER targets (e.g. GREB1). However, for the smaller sub-cluster 4OHT acted as an agonist and induced gene expression (blue bar, n=5; e.g. SNAI1); ICI reversed induction by both ligands (Figure 6B). E2-repressed genes were also sub-divided; for both sub-clusters 4OHT acted as an agonist and repressed gene expression. Among weakly E2-repressed genes (yellow bar, n=11) and strongly E2-repressed genes (dark green bar, n=31), 4OHT displayed greater agonist activity (stronger repression) among the latter (e.g. FOXO1). ICI reversed 4OHT-induced repression (Figure 6B). Upon sample clustering, all 24 and 72hr ICI-treated samples clustered independently from E2 and 4OHT-treated samples (data not shown). 4OHT-regulated expression more closely mirrors the agonist E2 versus the antagonist ICI, consistent with the ability of 4OHT to induce growth in MM134 cells.

Figure 6. Tamoxifen induces gene expression as an ER agonist.

(A), MM134 cells were hormone-deprived and treated with 100pM E2, 1μM 4OHT, or 1μM ICI for 3, 24, or 72hr. Heatmap represents log2 fold versus time-matched vehicle control. Genes clustered by Pearson complete correlation. ‘+’, commonly E2-regulated genes. Dashed white boxes highlight genes regulated by 4OHT as an agonist. (B), Gene expression (log2 fold versus control) per treatment and time point for all genes in indicated clusters. Points represent mean of n genes ± SD. P-values represent treatment effect by two-way ANOVA.

Tamoxifen-induced gene expression was also assessed in full serum in MCF-7 and MM134. In MCF-7, expression changes for all tamoxifen compounds paralleled those with ICI (Supplemental Figure 3A). However, in MM134, tamoxifen-induced changes were opposite to those with ICI for 34/107 genes (Supplemental Figure 3B). These genes all were ICI-induced, but tamoxifen-repressed (Supplemental Figure 3C), including cell cycle regulators (CDKN1C, MAP3K8) and growth factor receptors (ACVR1B, ACVR2A). These data are consistent with the agonist activity of 4OHT being specific to MM134 versus MCF-7.

FGFR1 is necessary for survival in the presence of tamoxifen in ILC cells

Over-expression of FGFR1 has been implicated in endocrine-resistance and sensitivity to FGFR inhibitors (5,14,35). Both MM134 and SUM44 carry high-level amplification of this locus at 8p12, and over-express FGFR1 (Supplemental Figure 4A). MM134 cell growth was assessed following treatment with the FGFR1 inhibitor PD173074 in the absence of E2 (−E2), or presence of 4OHT (+4OHT) or E2 (+E2). PD173074 reduced cell growth +E2, however, growth was reduced below control −E2 or +4OHT (Figure 7A). Similar results were observed using LY294002, which inhibits PI3K, a downstream FGFR1 effector (Figure 7B), as well as FGFR1 inhibitor SU5402 (Supplemental Figure 4B). Lapatinib, an EGFR/HER2 inhibitor, caused no changes in cell growth (Supplemental Figure 4C). Reduction of growth below controls suggests that FGFR1 inhibition induces cell death specifically −E2 or +4OHT, but not +E2.

Figure 7. FGFR1 inhibitor-induced death in MM134 is dependent on estrogen signaling.

(A–B), MM134 cells were hormone-deprived and treated with 0.1% EtOH vehicle, 1μM 4OHT, or 100pM E2 ± kinase inhibitor. Proliferation assessed 6 days post-treatment. Dashed line represents growth -E2. (C–D), MM134 treated as above ± 10μM kinase inhibitor, or 1μM STS. Timecourse represents repeated measures.

Parallel experiments assessed cell death compared to a positive control, staurosporine (STS), which induces extensive cell death. Modest cell death was accumulated −E2 or +4OHT versus +E2; STS induced extensive cell death (Figure 7C). In +E2, PD173074 induced a moderate amount of cell death, however, in −E2 or +4OHT cell death was comparable to STS-induced death. Though LY294002 was less effective than PD173074, +E2 cells were similarly resistant to LY294002, but were sensitive −E2 or +4OHT (Figure 7D). Lapatinib treatment did not change total cell death in any condition (Supplemental Figure 4D). FGFR1 signaling may be required for cell growth and survival −E2, as tamoxifen alone cannot maintain viability when FGFR1 signaling is inhibited.

Discussion

ILC patients generally present with tumor biomarkers associated with benefit from adjuvant endocrine therapy (reviewed in (5)). However, recent observations suggest that ILC patients may have equivalent or worse outcomes than IDC patients. Retrospective analysis of the BIG 1-98 trial suggests that a subset of ILC patients may not benefit from adjuvant tamoxifen (12). Understanding endocrine response and resistance in ILC is necessary to identify and treat endocrine resistance in ILC.

Despite extensive study in IDC, minimal data exist regarding the endocrine responsiveness of ILC. This report represents the largest study on ER function and endocrine response specifically in ILC cells. While >90% of ILC are ER-positive, most model systems for ILC, including a mouse model (36) and three cell lines (5), are ER-negative. These models may recapitulate other aspects of ILC biology, but studies in endocrine response and resistance are critical. Our studies are limited to the only ER-positive ILC models available, MM134, SUM44, and PDX HCI-013. Our observations demonstrate the need for new models to further investigation and facilitate clinical translation.

Among several genomic studies of ILC tumors (5,37–39), the only consistent finding is the loss of E-cadherin (CDH1), a hallmark of ILC (40). We previously observed that ER can regulate CDH1 expression (41), and hypothesized that E-cadherin loss may mediate tamoxifen-resistance. We abrogated E-cadherin in MCF-7 using antibodies or siRNA-mediated knockdown, but these preliminary experiments did not induce endocrine resistance (data not shown). Thus, we further characterized ER function in ILC cell lines.

The partial agonist effect of tamoxifen in MM134 cells may have important implications for the treatment of ILC patients. As a partial agonist, tumor growth may initially decrease versus pre-treatment. Tamoxifen alone induces cell death versus estrogen, and coupled with decreased growth may initially produce a favorable response. However, the overall growth observed suggests that ILC tumors similar to MM134 will outgrow with tamoxifen. Modeling this in vivo will require a xenograft model, however, neither MM134 nor SUM44 have been used in vivo in the literature. PDX HCI-013 represents a potential model, in particular given the E2-regulation of ILC-specific genes. Though the de novo agonist activity of tamoxifen was specifically observed in MM134, one other study has characterized tamoxifen resistance in ILC cells, and observed tamoxifen-induced growth in resistant SUM44 clones (13). Thus, this may be a common mechanism of endocrine resistance among a subset of ILC tumors. While the expression of tamoxifen-regulated genes may help identify these tumors, FGFR1 amplification or over-expression may also identify these tumors.

Previous reports identified FGFR1 as a novel target for ILC and a driver of endocrine resistance (14,35). Our observations suggest that either tamoxifen or FGFR1 inhibitor monotherapy may be sub-optimal against tamoxifen-resistant ILC. Combination therapy produced maximum cell death in vitro and may be most effective by blocking both pathways required for growth and survival. FGFR1 amplification may be a common event in primary ILC (14); however, public data from the Cancer Genome Atlas suggests that FGFR family amplification occurs in ~10% of both ILC and IDC (data not shown). Recurrent or metastatic ILC may be unique versus primary tumors. A recent analysis of recurrent ILC did not observe FGFR1 amplification in primary tumors, but 3/11 recurrent tumors harbored amplification (42). Another report also observed that several metastatic ILC gained FGFR1 amplifications versus matched primaries (43). Thus, FGFR1 amplification may be may be enriched in recurrent or metastatic ILC. Both MM134 and SUM44 have FGFR1 amplification and were derived from metastatic pleural effusions (5). Further, this putative role in endocrine resistance may be FGFR1-specific. MM134 cells also have CCND1 amplification (14); however, inhibition downstream of CCND1 using the CDK4/6 inhibitor PD0332991 is extremely toxic +E2 or +4OHT (Supplemental Figure 4E). This suggests that while MM134 may be CCND1-dependent, FGFR1 is specifically permissive for tamoxifen resistance. Tamoxifen-resistant recurrent ILCs that have gained FGFR1 amplification may benefit from an FGFR1 inhibitor with endocrine therapy.

One of the most strongly induced ILC-specific genes is WNT4. The mouse homolog Wnt4 is a critical mediator of ductal elongation and side-branching during mammary gland development (44). Though Brisken et al. demonstrated that Wnt4 expression is PR-driven, ILC cells may hijack this pathway by placing it under the control of ER. Consistent with this, an ER binding site near the WNT4 promoter is MM134-specific, and is not observed in IDC cells (33). Taken together, ILC cells may utilize a WNT4-driven developmental pathway to drive E2-induced growth.

Conversely, gene repression was enriched among ILC-specific genes, and the agonist effect of tamoxifen in the ILC-E2 geneset was observed primarily for repressed genes. This preferential repression may be sufficient to partially drive growth, but may explain why tamoxifen cannot fully induce growth or maintain viability versus E2. This suggests that in ILC cells, both estrogen and tamoxifen may recruit unique co-repressor complexes. Though the role of ER cofactors in tamoxifen resistance is actively studied (45–47), no unique co-factors have been reported in ILC, making this an important future direction. Interestingly, forkhead motifs were not enriched in MM134-specific distal ER binding sites, suggesting that alternative factors may be required for ER binding. Though not representative of distal sites, MM134 ER-binding sites within 20kb of an ILC-specific gene were weakly enriched for PAX4 motifs (Supplemental Figure 2C), consistent with the hypothesis that novel co-factors regulate ER binding in ILC. However, these represent subset analyses, and should be interpreted with caution. Of note, Hsu et al characterized distal EREs in MCF-7; amplification of distal EREs was associated with clinical tamoxifen resistance (48). Further understanding of the regulatory function of distal EREs in ILC cells is an important future direction.

Our characterization of ER function in ILC represents an important basis for future studies in endocrine response and resistance, as this has previously only been studied in IDC models. Further investigation in to ER-mediated gene expression in ILC, utilizing in vitro models and in vivo PDX models, may identify additional genes that can be targeted in conjunction with endocrine therapy to modulate ER activity in ILC tumors. Our observations that ER drives a unique program of gene expression in ILC cells correlates with the ability of tamoxifen to act as an agonist to induce growth in these cells. This phenotype mimics recent clinical observations that a subset of ILC tumors may be tamoxifen resistant. Genes regulated by tamoxifen as an agonist may serve as powerful biomarkers to identify de novo tamoxifen resistance, thus we envision that a neoadjuvant window trial may be an ideal setting to further examine tamoxifen resistance in ILC patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Breast Cancer Research Foundation (SO), Noreen Fraser Foundation (ALW), DoD BCRP (Postdoctoral Fellowship BC110619 (MJS), DoD Era of Hope Scholar Award (ALW)), Pennsylvania Department of Health (SO) (The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for analyses, interpretation, or conclusions). This project used UPCI Cancer Biomarkers, Biostatistics, and Cell Culture and Cytogenetics Facilities, supported by award P30CA047904 from NIH.

We thank Jian Chen for technical assistance and Dr. Adrian Lee for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None to disclose.

References

- 1.Fisher ER, Gregorio RM, Fisher B, Redmond C, Vellios F, Sommers SC. The pathology of invasive breast cancer. A syllabus derived from findings of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (protocol no. 4) Cancer. 1975;36:1–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197507)36:1<1::aid-cncr2820360102>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cristofanilli M, Gonzalez-Angulo A, Sneige N, Kau S-W, Broglio K, Theriault RL, et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma classic type: response to primary chemotherapy and survival outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:41–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pestalozzi BC, Zahrieh D, Mallon E, Gusterson BA, Price KN, Gelber RD, et al. Distinct clinical and prognostic features of infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast: combined results of 15 International Breast Cancer Study Group clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3006–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arpino G, Bardou VJ, Clark GM, Elledge RM. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast: tumor characteristics and clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R149–56. doi: 10.1186/bcr767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sikora MJ, Jankowitz RC, Dabbs DJ, Oesterreich S. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: patient response to systemic endocrine therapy and hormone response in model systems. Steroids. 2013;78:568–75. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biglia N, Mariani L, Sgro L, Mininanni P, Moggio G, Sismondi P. Increased incidence of lobular breast cancer in women treated with hormone replacement therapy: implications for diagnosis, surgical and medical treatment. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14:549–67. doi: 10.1677/ERC-06-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasif N, Maggard MA, Ko CY, Giuliano AE. Invasive lobular vs. ductal breast cancer: a stage-matched comparison of outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1862–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0953-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colleoni M, Rotmensz N, Maisonneuve P, Mastropasqua MG, Luini A, Veronesi P, et al. Outcome of special types of luminal breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1428–36. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Powe DG, Green AR, Habashy H, Grainge MJ, et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: response to hormonal therapy and outcomes. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mhuircheartaigh JN, Curran C, Hennessy E, Kerin MJ. Prospective matched-pair comparison of outcome after treatment for lobular and ductal breast carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2008;95:827–33. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korhonen T, Kuukasjärvi T, Huhtala H, Alarmo E-L, Holli K, Kallioniemi A, et al. The impact of lobular and ductal breast cancer histology on the metastatic behavior and long term survival of breast cancer patients. Breast. 2013;22:1119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metzger-Filho O, Giobbie-Hurder A, Mallon E, Viale G, Winer E, Thurlimann B, et al. Relative effectiveness of letrozole compared with tamoxifen for patients with lobular carcinoma in the BIG 1–98 trial. Cancer Res. 2012;72(24 Supplement):S1–1. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riggins RB, Lan JP-J, Zhu Y, Klimach U, Zwart A, Cavalli LR, et al. ERRgamma mediates tamoxifen resistance in novel models of invasive lobular breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8908–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reis-Filho JS, Simpson PT, Turner NC, Lambros MB, Jones C, Mackay A, et al. FGFR1 emerges as a potential therapeutic target for lobular breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6652–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiner GC, Katzenellenbogen BS. Characterization of estrogen and progesterone receptors and the dissociated regulation of growth and progesterone receptor stimulation by estrogen in MDA-MB-134 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1986;46:1124–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sikora MJ, Strumba V, Lippman ME, Johnson MD, Rae JM. Mechanisms of estrogen-independent breast cancer growth driven by low estrogen concentrations are unique versus complete estrogen deprivation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:1027–39. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2032-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ethier SP, Mahacek ML, Gullick WJ, Frank TS, Weber BL. Differential isolation of normal luminal mammary epithelial cells and breast cancer cells from primary and metastatic sites using selective media. Cancer Res. 1993;53:627–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochsner S, Steffen DL, Hilsenbeck SG, Chen ES, Watkins C, McKenna NJ. GEMS (Gene Expression MetaSignatures), a Web resource for querying meta-analysis of expression microarray datasets: 17beta-estradiol in MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:23–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creighton CJ, Cordero KE, Larios JM, Miller RS, Johnson MD, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Genes regulated by estrogen in breast tumor cells in vitro are similarly regulated in vivo in tumor xenografts and human breast tumors. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R28. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-r28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt D, Wilson MD, Spyrou C, Brown GD, Hadfield J, Odom DT. ChIP-seq: using high-throughput sequencing to discover protein-DNA interactions. Methods. 2009;48:240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin H, Liu T, Manrai AK, Liu XS. CEAS: cis-regulatory element annotation system. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2605–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph R, Orlov YL, Huss M, Sun W, Kong SL, Ukil L, et al. Integrative model of genomic factors for determining binding site selection by estrogen receptor-α. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:456. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross-Innes CS, Stark R, Holmes KA, Schmidt D, Spyrou C, Russell R, et al. Cooperative interaction between retinoic acid receptor-alpha and estrogen receptor in breast cancer. Genes Dev. 2010;24:171–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.552910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross-Innes CS, Stark R, Teschendorff AE, Holmes Ka, Ali HR, Dunning MJ, et al. Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature. 2012;481:389–93. doi: 10.1038/nature10730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt D, Schwalie PC, Ross-Innes CS, Hurtado A, Brown GD, Carroll JS, et al. A CTCF-independent role for cohesin in tissue-specific transcription. Genome Res. 2010;20:578–88. doi: 10.1101/gr.100479.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai W-W, Wang Z, Yiu TT, Akdemir KC, Xia W, Winter S, et al. TRIM24 links a non-canonical histone signature to breast cancer. Nature. 2010;468:927–32. doi: 10.1038/nature09542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeRose YS, Wang G, Lin Y-C, Bernard PS, Buys SS, Ebbert MTW, et al. Tumor grafts derived from women with breast cancer authentically reflect tumor pathology, growth, metastasis and disease outcomes. Nat Med. 2011;17:1514–20. doi: 10.1038/nm.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeRose YS, Gligorich KM, Wang G, Georgelas A, Bowman P, Courdy SJ, et al. Patient-derived models of human breast cancer: protocols for in vitro and in vivo applications in tumor biology and translational medicine. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2013;60:14.23.1–14.23.43. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph1423s60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–8. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurtado A, Holmes KA, Ross-Innes CS, Schmidt D, Carroll JS. FOXA1 is a key determinant of estrogen receptor function and endocrine response. Nat Genet. 2011;43:27–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bryant HU. Selective estrogen receptor modulators. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2002;3:231–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1020076426727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner N, Pearson A, Sharpe R, Lambros M, Geyer F, Lopez-Garcia Ma, et al. FGFR1 amplification drives endocrine therapy resistance and is a therapeutic target in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2085–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derksen PWB, Liu X, Saridin F, van der Gulden H, Zevenhoven J, Evers B, et al. Somatic inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 in mice leads to metastatic lobular mammary carcinoma through induction of anoikis resistance and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:437–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertucci F, Orsetti B, Nègre V, Finetti P, Rougé C, Ahomadegbe J-CC, et al. Lobular and ductal carcinomas of the breast have distinct genomic and expression profiles. Oncogene. 2008;27:5359–72. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weigelt B, Horlings HM, Kreike B, Hayes MM, Hauptmann M, Wessels LFA, et al. Refinement of breast cancer classification by molecular characterization of histological special types. J Pathol. 2008;216:141–50. doi: 10.1002/path.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weigelt B, Geyer FC, Natrajan R, Lopez-Garcia MA, Ahmad AS, Savage K, et al. The molecular underpinning of lobular histological growth pattern: a genome-wide transcriptomic analysis of invasive lobular carcinomas and grade- and molecular subtype-matched invasive ductal carcinomas of no special type. J Pathol. 2010;220:45–57. doi: 10.1002/path.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dabbs DJ, Bhargava R, Chivukula M. Lobular versus ductal breast neoplasms: the diagnostic utility of p120 catenin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:427–37. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213386.63160.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oesterreich S, Deng W, Jiang S, Cui X, Ivanova M, Schiff R, et al. Estrogen-mediated down-regulation of E-cadherin in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross JS, Wang K, Sheehan CE, Boguniewicz AB, Otto G, Downing SR, et al. Relapsed classic E-cadherin (CDH1)-mutated invasive lobular breast cancer shows a high frequency of HER2 (ERBB2) gene mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2668–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brunello E, Brunelli M, Bogina G, Caliò A, Manfrin E, Nottegar A, et al. FGFR-1 amplification in metastatic lymph-nodal and haematogenous lobular breast carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31:103. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brisken C, Heineman A, Chavarria T, Elenbaas B, Tan J, Dey SK, et al. Essential function of Wnt-4 in mammary gland development downstream of progesterone signaling. Genes Dev. 2000;14:650–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Droog M, Beelen K, Linn S, Zwart W. Tamoxifen resistance: From bench to bedside. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;717:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McBryan J, Theissen SM, Byrne C, Hughes E, Cocchiglia S, Sande S, et al. Metastatic progression with resistance to aromatase inhibitors is driven by the steroid receptor coactivator SRC-1. Cancer Res. 2012;72:548–59. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graham JD, Bain DL, Richer JK, Jackson TA, Tung L, Horwitz KB. Thoughts on tamoxifen resistant breast cancer. Are coregulators the answer or just a red herring? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;74:255–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsu P-Y, Hsu H-K, Lan X, Juan L, Yan PS, Labanowska J, et al. Amplification of distant estrogen response elements deregulates target genes associated with tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:197–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.