Abstract

Background

The Yes-associated-protein-1 (YAP1) is a novel, direct regulator of stem cell genes both in development and cancer. FAT4 is an upstream regulator that induces YAP1 cytosolic sequestering by phosphorylation (p-Ser 127) and therefore inhibits YAP1-dependent cellular proliferation. We hypothesized that loss of FAT4 signaling would result in expansion of the nephron progenitor population in kidney development and that YAP1 subcellular localization would be dysregulated in Wilms tumor (WT), an embryonal malignancy that retains gene expression profiles and histologic features reminiscent of the embryonic kidney.

Methods

Fetal kidneys from Fat4−/− mice were harvested at e18.5 and markers of nephron progenitors were investigated using immunohistochemical analysis. To examine YAP1 subcellular localization in WT, a primary WT cell line (VUWT30) was analyzed by immunofluorescence. Forty WT specimens evenly distributed between favorable and unfavorable histology (n = 20 each), and treatment failure or success (n = 20 each) was analyzed for total and phosphorylated YAP1 using immunohistochemistry and Western blot.

Results

Fat4−/− mouse fetal kidneys exhibit nuclear YAP1 with increased proliferation and expansion of nephron progenitor cells. In contrast to kidney development, subcellular localization of YAP1 is dysregulated in WT, with a preponderance of nuclear p-YAP1. By Western blot, median p-YAP1 quantity was 5.2-fold greater in unfavorable histology WT (P = 0.05).

Conclusions

Fetal kidneys in Fat4−/− mice exhibit a phenotype reminiscent of nephrogenic rests, a WT precursor lesion. In WT, YAP1 subcellular localization is dysregulated and p-YAP1 accumulation is a novel biomarker of unfavorable histology.

Keywords: anaplasia, biomarker, nephrogenic rests, Wilms tumor, YAP1

INTRODUCTION

Wilms tumor (WT) is the most common childhood kidney cancer worldwide, and in developed countries, overall survival at 5 years now exceeds 90% [1–3]. Because remarkable progress in overall survival has been achieved through standardized multimodal therapies introduced approximately 40 years ago, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) of North America currently emphasizes and supports research interests that seek to identify features of WT treatment resistance, having the continual goals both to close the remaining survival gap and to reduce treatment toxicities for survivors [4]. A variety of molecular (disease) and epidemiologic (patient) characteristics have been associated with adverse outcomes from WT [5,6]. The most ominous WT-specific feature of treatment resistance is anaplasia, or unfavorable histology, which is characterized by nuclear gigantism, hyperchromasia, and bizarre multipolar mitoses [7–9]. Although anaplasia is observed in only 6% of WT cases, its diffuse presence is associated with almost half of WT-related cancer deaths [1]. An emerging concept in cancer biology more broadly is that treatment resistance is conferred by the cancer stem cell [10,11]. Embryonal tumors, such as WT, and for that matter many adult carcinomas, often hijack embryonic transcriptional programs and signaling pathways that bestow stemness and proliferative capacity, which together fuel indefinite self-perpetuation.

The Yes-associated protein-1 (YAP1) is a key transcriptional activator of the Hippo pathway, which through G-coupled-protein receptor signaling regulates tissue growth and organ size in development and regeneration [12–14]. Activating mutations in participants of the Hippo pathway have been associated with tissue overgrowth. During development, YAP1 has been shown specifically to promote maintenance of certain progenitor populations by enhancing proliferation and simultaneously inhibiting epithelial differentiation [12,15]. Supporting this function in development, YAP1 has been shown to interact with specific transcriptional programs and signaling pathways that are central to regulating stem cell maintenance and epithelial commitment, including the Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and TGF-β pathways [16–19]. Subsequent analyses, extended naturally to malignancies, have shown that YAP1-dependent proliferative properties are enhanced in various adult carcinomas [18,20–23]. In this malignant context, YAP1 overexpression in epithelial cell lines has been shown to induce proliferative responses, anchorage-independent growth, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.

YAP1 displays unique functional properties dependent on its subcellular localization, which is largely determined through phosphorylation of serine 127. When modified, it binds to 14-3-3 proteins and is sequestered in the cytoplasm. Once sequestered in the cytosol, YAP1 may regulate cell–cell contact and embryonic patterning by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β signaling. FAT4 is an upstream regulator of YAP1 that induces its phosphorylation and cytosolic sequestering and thereby inhibits YAP1-dependent cellular proliferation [24]. Although phosphorylation of YAP1 at Ser127 is thought to initiate a phosphodegron complex, the functional significance of this phosphoprotein to accumulate in the malignant context is unknown [25]. In kidney development, YAP1 is essential for induction and progression of murine nephrogenesis and loss of YAP1 causes downregulation of genes associated with nephron progenitor stem cell function [26]. Although YAP1 functions are context-dependent and protean in different malignancies, its deregulated activation is common to numerous adult-type cancers and portends adverse outcomes.

We hypothesized that increased YAP1 nuclear translocation would result in expansion of nephron progenitor cells and that subcellular localization and expression of YAP1 would be dysregulated in the embryonal kidney malignancy WT.

METHODS

Mouse Fetal Kidney Preparation

Fat4−/− mice were obtained from Helen McNeill (Mt. Sinai Hospital, Toronto, CA) [27]. All animals were housed, maintained, bred, and used according to protocols approved by the Institutional for Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center. Kidneys were dissected from wild type and Fat4-mutant embryos at e18.5 and were fixed in 4% PFA for 1 hour at room temperature. Kidney samples were washed in PBS thrice (5 minutes each) and stored in a 30% sucrose solution overnight at 4°F. The following day, kidneys were cryopreserved and embedded. Slides containing 10µm cryosections were washed thrice in PBS-TritonX100 (5 minutes each), and antigens were retrieved using citrate buffer (pH 6.0). After cooling, slides were washed in TBST thrice (5 minutes each) and blocked for an hour at room temperature. To multi-label embryonic kidneys, antibodies for YAP and pYAP (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), SIX2 (Proteintech, Chicago, IL), and cytokeratin (CK) (Sigma– Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were each added to sections at a dilution of 1:500. The signal was developed with tyramide amplification. Images were captured using the Zeiss-510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Cell Lines

HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were propagated according to manufacturer’s protocol and were used as a positive control for YAP1 detection. The human WT cell line, WiT49, was kindly provided by Dr. Herman Yeger (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, CA) and cultured as previously described [28]. Fresh samples of the human WT VUWT30, collected immediately after surgical resection, were mechanically minced in culture medium and then enzymatically dispersed using dispase (StemCell Technology, Vancouver, BC, CA) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Contents of these culture plates were then strained over sterile cheese cloth to filter any remaining clumps of WT tissue. Dispersed cells were centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes, washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), centrifuged again, and suspended in 1 × PBS containing 0.2% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were then cultured in DMEM/F-12 medium containing 2% FBS, transferrin, hydrocortisone, selenium, insulin, triidothyronine, TGF-α, FGF2, LIF, Y27632, and IGF2.

Clinical Wilms Tumor Specimens

To evaluate YAP1 and its Ser127 phopshoprotein (p-YAP1) across WT patient and disease characteristics, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) provided 40 corresponding formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) and snap frozen samples of human WT specimens. The COG selected equal numbers of favorable (FH, n = 20) and unfavorable (UH, n = 20) histology WT specimens, which were selected further to include patients who experienced treatment success (n = 20) or failure (n = 20). As a result, 10 patients having either FH or UH experienced either treatment success or failure, respectively. These four specimen groups of 10 patients were matched according to age at diagnosis, gender, and stage of disease. Importantly, all tissue samples had been deidentified before shipping, and the investigative team was blinded to all disease and patient characteristics until experimental data were completely analyzed by the COG statistician (JRA). Only histology was released to the investigative team to ensure accurate generation of immunohistochemistry figures. These 40 COG specimens were used to evaluate YAP1 expression patterns across the following seven WT characteristics: age, gender, histology (FH and UH), race, stage, treatment failure and success, and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of 1p and 16q mutations. Additionally, our laboratory maintains a WT tissue repository, which is approved through the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board (#100734 and 020888) and contains 65 clinical WT specimens (both corresponding FFPE and snap frozen samples) and numerous murine fetal kidney (MFK) specimens. These latter WT (de-identified as VUWT) and MFK specimens comprise the source of control specimens in which all conditions for total YAP1 and p-YAP1 detection were optimized.

Immunohistochemistry

Cellular distribution of total YAP1 across the 40 WT specimens was evaluated using peroxidase-DAB immunohistochemistry. YAP antibody (#4912, Cell Signaling Technology) was applied at a dilution of 1:100, using our previously published protocols [29,30]. Because of limited COG FFPE tissues, p-YAP (#4911, Ser127, Cell Signaling Technology) was evaluated in VUWT35, which shows intense nuclear and cytosolic expression of YAP1, to test whether the cellular distribution differed between these two proteins in WT.

Immunoblots

Cultured cell lines and whole snap frozen tissues were lysed and homogenized for protein extraction, as previously described [29,30]. Protein concentrations for each specimen were measured according to the standard Bio-Rad protocol (Hercules, CA). Briefly, protein extracts were loaded in 50µg aliquots and separated on 12% gels. After transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, blots were incubated separately with anti-YAP1 (1:1,000) and antip-YAP1 (1:5,000) antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, as above) overnight at 4°C. Blots were secondarily incubated with anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) and were visualized using ECL reagents and detection system (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Additionally, anti-β-catenin antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology) was used to probe gel-separated WT samples, as above. To control for any variability in protein loading between samples, blots were stripped, as previously described, and then probed for β-actin. Densitometry for allYAP1, p-YAP1, and β-catenin bands was determined using Adobe Photoshop software (San Jose, CA) and then normalized to the corresponding β-actin bands per specimen.

Statistical Analysis

The principal aim of this study was to evaluate YAP1 and p-YAP1 expression across disease and patient characteristics commonly associated with disparate WT outcomes. Results from the above analysis were compared among subsets of patients using the two-sample Wilcoxon test (or the Kruskal–Wallis test for more than two groups). Nonparametric comparisons were performed because the distribution of study variables appeared to be long-tailed. To determine associations between YAP1 and p-YAP1 a nonparametric measure of correlation was utilized (Spearman’s correlation coefficient). Calculations were performed using the SAS statistical software package (SAS, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

YAP1 Expression Domain in Mouse Kidney Development

To gain insight into the molecular control of differential YAP1 subcellular localization in kidney development, we characterized the expression domain and nucleo-cytosolic trafficking of YAP proteins during nephron development in kidneys isolated from wild type and Fat4−/− mice at e18.5. By immunohistochemistry, total YAP expression in wild type kidneys was detected throughout the cell cytoplasm and nucleus of the nephron progenitor cells, ureteric bud, and stroma (Fig. 1A and B). However, in the progenitor cells of the Fat4−/− mutants, YAP was localized primarily to the nucleus (Fig. 1C). The YAP phosphoprotein was expressed almost exclusively in the nephrogenic zone of wild type murine kidneys throughout the SIX2-positive progenitor cells, ureteric bud epithelia (demarcated by cytokeratin, CK) and surrounding stroma (Fig. 1D and E). In the nephrogenic zone of Fat4-null kidneys, pYAP expression was significantly reduced to almost lost from the expanded progenitor domain while those in the ureteric bud and the stroma remained unaltered (Fig. 1F). Interestingly, the nephron progenitor population of this mutant appeared to aggregate and expand, resembling nephrogenic rests, which are considered the precursor lesion of WT (Fig. 1H). This analysis suggests that Fat4 from the stromal fibroblast may drive phosphorylation of YAP in the progenitor cells. In the absence of this Fat4 signal, dephosphorylated YAP resides in the nucleus, which causes increased proliferation and expansion of the progenitor cells.

Fig. 1.

Localization of YAP1 and pYAP1 proteins in wild type and Fat4-null kidneys. Expression of YAP1 in e18.5 wild type kidneys (A and B) is detected in the nucleus and cytosol of SIX2+ nephron progenitors, ureteric bud epithelia, stroma, and medullary epithelia. In Fat4-null kidneys (C), YAP1 appears enriched in the nucleus of an expanded SIX2+ progenitor population (white arrow). The expression domain of pYAP1 in wild type murine kidneys differed, showing cytosolic detection restricted to the nephrogenic zone (D and E) progenitors and stroma. In the Fat4-null kidney, pYAP1 appeared lost in the expanded SIX2+ nephron progenitor population but remained active in the surrounding stroma. All sections have been co-stained with the bonafide progenitor marker SIX2 (in red) and collecting duct epithelium marker cytokeratin, CK (in blue). * Indicates the loss of pYAP1 expression (F) and the white arrow indicates increased nuclear YAP1 expression (C) in the expanded progenitor population of Fat4-null kidneys. Images (A) and (D) are captured at 10× and all other images are captured at 63× magnification. Representative wild type (G) and Fat4 mutant kidney (H) at e18.5 shows, after hematoxylin and eosin staining, aggregated and expanded nephron progenitor population (small round blue cells, white arrows) in the latter. In the Fat4 mutants, the undifferentiated progenitor cells appear to pile up, forming nephrogenic-rest like structures, which are present either adjacent to the ureteric bud or independent of it.

YAP1 Expression in Primary WT Culture

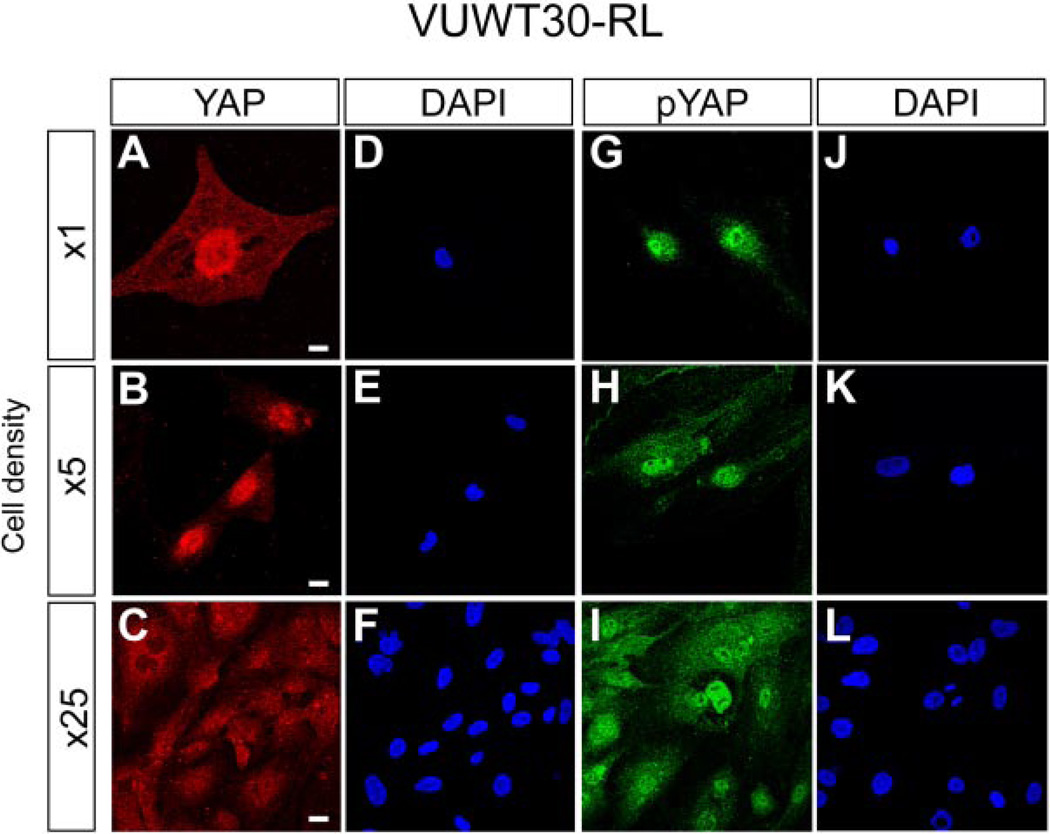

Primary cultures of WT that retain markers and features of blastema are challenging to establish, as within a few passages blastema rapidly differentiate in vitro, quiesce, and lose stem characteristics, or the cultures become overrun with heartier stromal elements. To evaluate YAP1 expression in a primary human WT culture line that has maintained microscopic features and gene expression profiles of primitive blastema, in vitro immunofluorescence was performed. Notably, this primary WT cell line was established from an older child having a blastemal-predominant FH tumor and bulky lymph node metastases who subsequently relapsed.

At low cellular densities, YAP1 expression appeared to be predominantly nuclear (Fig. 2A and B). However, in areas of more cellular density and in confluent cell culture, YAP1 expression was both nuclear and cytosolic (Fig. 2C). In contrast, p-YAP1 was found to be nuclear and cytosolic at both high and low cellular densities (Fig. 2G, H, and I). The nuclear localization of p-YAP1 at all cellular densities in this WT cell line differed from the cytosolic expression pattern in the embryonic kidney (Fig. 1D and E), suggesting loss of YAP1 nuclear/cytosolic trafficking control in the malignant context of WT.

Fig. 2.

YAP1 (red) and p-YAP1 (green) are expressed in a primary culture of human WT (VUTW30). YAP1 (red) is enriched in the nucleus at low cellular density (A and B), but becomes both cytosolic and nuclear at higher cellular density (C). DAPI (blue) nuclear stain illustrates position of nuclei (D, E, and F). p-YAP1 (green) is enriched in the nucleus both at low (G and H) and high (I) cellular density. DAPI (blue) nuclear stain illustrates position of nuclei (J, K, and L).

In this WT cell culture, YAP1 was found to co-localize with CITED1, a previously established WT biomarker, and marker of the self-renewing nephron progenitor population in kidney development (Fig. 3J and K). YAP1 was also found to co-localize with NCAM, a putative WT cancer stem cell marker in some cells (Fig. 3L).

Fig. 3.

Co-localization of YAP1 with renal stem cell markers in a primary culture of human WT (VUWT30). CITED1 (green) (A) and YAP1 (red) (D) appear more nuclear enriched at low cellular density when compared to high density culture (B and E). DAPI (blue) nuclear stain illustrates position of nuclei (G and H). (I) DAPI (blue) stain illustrates position of nuclei. Merged images (J and K) demonstrate co-localization of YAP1 and CITED1, a marker of the self-renewing nephron progenitor population. The bottom row illustrates co-localization of NCAM, a putative WT cancer stem cell marker (red, C), and YAP1 (green, F). Merged images (L) show co-localization in some cells.

Total YAP1 Protein Content in Clinical WT Specimens

The 40 COG WT specimens showed on immunoblot varying quantities of total YAP1 protein across all seven diseases and patient characteristics tested (Fig. 4B). Although YAP1 protein was readily detected in each of these groups, no statistical association was found between total YAP1 content and any molecular or epidemiologic feature evaluated.

Fig. 4.

A: Western blot for total (t) and Serine127 phosphorylated (p) YAP1 in mouse fetal kidney (MFK), HeLa cells (positive control), four primary treatment-naïve WTs (VUWT), and the human WT cell line, WiT49. The ratio of p-YAP1:t-YAP1 in MFK was 4.7. B: Western blot for t-YAP1, p-YAP1, β-catenin, and β-actin in COG WT specimens having unfavorable (UH) or favorable (FH) histology. C: Spearman correlation of t-YAP1 and p-YAP1 in COG WT specimens (0.587, P < 0.001). D: Median p-YAP1 levels normalized to β-actin levels in the 40 COG specimens separated according to histology (UH 5.2-fold > FH, n = 20 specimens per histologic group; P = 0.05). E: Median p-YAP1 levels normalized to β-actin levels in the 40 COG specimens separated according to age; 24 months and older (n = 28) 3.8-fold > 23 months and younger (n = 12; P = 0.07). F: p-YAP1:t-YAP1 ratios according to race group in this COG WT cohort. Although only two Asian patients were included in this analysis, this ratio was 14.7-fold greater than white patients (P = 0.07) and may be of interest for future study given the small number of Asian patients in this cohort.

p-YAP1 (Ser127) Protein Content in Clinical WT Specimens

On immunoblot, p-YAP1 content also varied across these same 40 COG WT specimens (Fig. 4B). A strong positive correlation was observed for p-YAP1 and YAP1 quantities across the 40 COG WT specimens (Spearman correlation 0.587, P < 0.001; Fig. 4C). When comparing the median content of p-YAP1 across the seven WT characteristics tested, unfavorable histology (i.e., anaplastic) specimens showed 5.2-fold greater p-YAP1 content than favorable histology (26 v. 5; P = 0.05; Fig. 4D). Of additional interest, but not statistically significant, specimens of WT patients older than age 24 months (n = 28) showed 3.8-fold greater median p-YAP1 content than WTs from patients <24 months of age (n = 12; 23 v. 6; P = 0.07; Fig. 4E).

For the control analysis of YAP1 and p-YAP1 content in murine fetal kidney (MFK), VUWT specimens, and the HeLa and WiT49 cell lines, we noted that the ratios of p-YAP1 to YAP1 often varied according to context. Specifically, the ratio of p-YAP1:YAP1 content in MFK was 4.7, which potentially might suggest a more embryonic phenotype when observed in the malignant context. When comparing the ratio of p-YAP1 to YAP1 content in the same WT across all 40 COG specimens, it was observed that 15 of the WTs showed a ratio of p-YAP1:YAP1 >1, whereas 25 WT specimens showed a ratio <1.

For the seven disease and patient characteristics tested, statistically insignificant variation in p-YAP1:YAP1 ratios was observed among the four race groups included in this analysis, which may be of future interest given the small sample size in this study. Median p-YAP1:YAP1 content ratios were 6.5 for Asian (n = 2), 0.79 for Hispanic (n = 6), White 0.44 (n = 25), and 0.14 for Black (n = 7; P = 0.07; Fig. 4F).

YAP1 Expression Domain in Clinical WT Specimens

All three cellular elements of the classic triphasic WT (i.e., blastema, epithelia, and stroma) expressed specific yet variable intensities of YAP1 (Fig. 5). Both favorable and unfavorable histology specimens expressed YAP1 in all three cellular elements. For WT specimens in this cohort having blastema (n = 37), 31 (83.4%) expressed simultaneous nuclear and cytosolic YAP1 in this cell type, 6 expressed nuclear-only YAP1 (16.6%) in blastema, and no WT blastema showed cytosolic-only detection of YAP1 (Table I; the remaining three WT specimens had no blastema to evaluate). For the seven disease and patient characteristics evaluated, age >24 months associated with more frequent nuclear and cytosolic YAP1 expression (n = 24, 77%) in blastema than nuclear-only detection (n = 2, 33%; P = 0.05). Therefore, only WT patient age appears related to differential YAP1 staining patterns in the blastemal compartment.

Fig. 5.

A and B: t-YAP1 immunostaining in a favorable histology WT. A: low power (100×) and (B) high power (400×) photomicrographs of the same COG WT specimen. t-YAP1 is almost exclusively detected in nuclei and appears particularly robust in epithelial elements (primitive tubules). C–E: High power (400×) photomicrographs of t-YAP1 in three separate COG unfavorable histology WT specimens. t-YAP1 appears robust in the nuclei but also shows more cytosolic detection, particularly in (E), suggestive of a phosphorylated form. F: Immunostaining for p-YAP1 (Ser127) in same specimen as (E) showing rich cytosolic detection and nuclear expression.

TABLE I.

YAP1 Subcellular Localization by Immunostaining in Wilms Tumor Blastema

| Characteristic | Nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (N = 31) |

Nuclear-only staining (N = 6) |

P-value for comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <24 months | 7 (23%) | 4 (67%) | |

| ≥24 months | 24 | 2 | 0.05 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 13 (42%) | 3 (50%) | |

| Female | 18 | 3 | 1.00 |

| Histology | |||

| Favorable | 15 (48%) | 4 (67%) | |

| Anaplasia | 16 | 2 | 0.66 |

| LOH | |||

| 1p−/16q− | 20 (67%) | 4 (67%) | |

| 1p+/16q− | 5 (17%) | 2(33%) | |

| 1p−/16q+ | 2 (7%) | 0 | |

| 1p+/16q+ | 3 (10%) | 0 | 0.85 |

| (1 missing) | |||

| Institutional stage (FINSTGE) | |||

| I/II | 15 (48%) | 3 (50%) | |

| III | 7 (23%) | 2 (33%) | |

| IV | 9 (29%) | 1 (17%) | 0.86 |

| Treatment outcome | |||

| Failure | 10 (32%) | 4 (67%) | |

| No failure | 21 | 2 | 0.17 |

| Race | |||

| White | 21 (68%) | 2 (33%) | |

| Black | 5 (16%) | 1 (17%) | |

| Asian | 1 (3%) | 1 (17%) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (13%) | 2 (33%) | 0.15 |

Epithelial elements were present in 31 of these COG WT specimens and showed simultaneous nuclear and cytosolic YAP1 detection in 73.3% (n = 22) of specimens, nuclear-only detection in 26.7% (n = 8), and cytosolic-only in one specimen; the remaining nine specimens had no epithelia to evaluate. Although YAP1 was visualized commonly, specifically, and often intensely in epithelial compartments of both favorable and unfavorable histology specimens (Fig. 5), no definitive association was observed between it and the seven WT characteristics tested.

WT stroma was present in all 40 specimens, and YAP1 was detected in stromal nuclei of 24 specimens (60%). When comparing stroma-positive and stroma-negative WT specimens, no significant association was found with any of the seven characteristics tested.

DISCUSSION

These studies show that Fat4−/− fetal mice kidneys, which exhibit resultant overexpression and increased nuclear translocation of YAP1, show a phenotype of persistent and expanded nephron progenitor cells that is reminiscent of nephrogenic rests, the well-known Wilms tumor precursor lesion. Because of this nephrogenic rest phenotype, we aimed to determine whether YAP1 expression was a biomarker of Wilms tumor and whether its expression was dysregulated in the malignant context. Using primary cultures of human WT, we confirmed expression of YAP-1 and its phosphoprotein p-YAP1. Furthermore, we determined that, unlike the highly regulated cytosolic location of phosphorylated YAP-1 in development, p-YAP1 nuclear–cytosolic trafficking appears dysregulated in the malignant context, resulting in persistent nuclear localization despite phosphorylation. We determined that YAP1 is expressed consistently and robustly across seven molecular and epidemiologic characteristics commonly associated with WT behavior and outcome. Furthermore, an accumulation of p-YAP1 associates with anaplastic WT, an ominous clinical feature of treatment resistance that is responsible for 50% of WT deaths currently.

A standardized, multimodal approach to WT therapy, evaluated through numerous clinical trials over the last four decades, has achieved remarkable cure rates with overall survival at 5 years now exceeding 90% [1,2]. Nevertheless, many children still continue to die from WT, and survivors are often left to live life with debilitating sequelae of treatment toxicity. Although therapy for low- and standard-risk WT is now reasonably well tolerated, patients who present with high-risk disease (defined by diffuse anaplasia) or who experience relapse require highly toxic therapies that can result in significant secondary health consequences. The COG therefore has emphasized research efforts to identify markers that associate with or predict adverse events to guide treatment algorithms of WT [4]. Such a strategy will allow pediatric oncology care teams to tailor and individualize the intensity of WT therapy according to cell-specific features. Importantly, identifying markers of adverse WT biology, such as p-YAP1, will lead to future studies to evaluate novel therapies that target these specific molecular pathways.

Deregulated YAP1 activity in WT, particularly the accumulation of its Ser127 phosphoprotein, indeed may signal the characteristic that most threatens a child’s survival from WT, the anaplastic phenotype, although these current studies were not designed to tease apart the specific mechanism. Because anaplasia tends to arise in older patients and in association with deregulated p53 buildup, some investigators have proposed that WT may indeed follow a disease progression sequence or continuum [6]. Aberrant accumulation of p-YAP1 in WT therefore may too herald disease progression towards diffuse anaplasia. Furthermore, older WT patients more commonly have blastemal-predominant histopathology, which in our current studies associated with increased frequency of cytosolic detection, likely representing p-YAP1, although it was not possible to verify this assumption due to insufficient numbers of tissue sections.

Deregulated expression and accumulation of YAP1 are features of numerous adult cancers and have been closely linked to poor prognosis. The oncogenic mechanism of YAP1 in these carcinomas however remains context-dependent and has yet to be clarified in embryonal tumors, such as WT. Our speculation in the embryonal and WT context is that YAP1, as a non-DNA binding transcriptional co-activator, facilitates stem cell gene expression, which includes proliferation and self-renewal targets, as is analogous to its functional purpose in development. From our modeling of YAP1 subcellular localization in the embryonic kidneys of wild type and Fat4-null mice, we suspect that loss of YAP1 phosphorylation, as in the context of Fat4 inactivation, may facilitate its nuclear localization and pro-proliferative effects to expand a stem cell population, whether embryonic or malignant. Pertinently, inactivating mutations in the tumor suppressor, FAT4, have been identified in melanoma, gastric, and pancreatic cancers [24,31,32]. Future studies are planned to evaluate the functional significance and mechanism of YAP1 activation, such as upstream FAT4 mutation, and pYAP1 accumulation in the WT context.

The question arises why p-YAP1, which has been previously associated with cytosolic localization and inactivation of YAP1, would associate with the aggressive clinical feature of anaplasia and therefore treatment resistance in WT. The current study shows that YAP1 nuclear trafficking is dysregulated in WT and that p-YAP1 may still be nuclear and active in this context. WhetherYAP1 in WT model systems continues to facilitate transcription of stem cell genes or genes that promote cancer cell growth despite phosphorylation at Ser 127 will be the subject of future investigation.

In summary, this study evaluated YAP1 and its Ser127 phosphoprotein in WT. Most notably, total YAP1 is robustly expressed across seven commonly studied disease and patient characteristics associated with WT behavior and remained abundantly detectable and showed dysregulated subcellular localization in a primary culture of WT. YAP1 represents a novel biomarker that applies broadly to this potentially lethal childhood cancer, its subcellular localization is dysregulated, and its phosphorylation at Ser127 associates with anaplasia, an observation, which warrants more detailed functional and mechanistic study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NCI grants 4R00CA135695-03 (H.N.L.) and 5T32CA106183-06A1 (A.J.M.) and by the Section of Surgical Sciences and the Ingram Cancer Center of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center. The authors recognize the invaluable resources, both personnel and tissues, of the Children’s Oncology Group, which together facilitate the translational research of pediatric cancers.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Nothing to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kalapurakal JA, Dome JS, Perlman EJ, et al. Management of Wilms’ tumour: Current practice and future goals. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidoff AM. Wilms’ tumor. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:357–364. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832b323a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al. Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: Challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2625–2634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dome JS, Fernandez CV, Mullen EA, et al. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: Renal tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:994–1000. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang CC, Gadd S, Breslow N, et al. Predicting relapse in favorable histology Wilms tumor using gene expression analysis: A report from the Renal Tumor Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1770–1778. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadd S, Huff V, Huang CC, et al. Clinically relevant subsets identified by gene expression patterns support a revised ontogenic model of Wilms tumor: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Neoplasia. 2012;14:742–756. doi: 10.1593/neo.12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardeesy N, Falkoff D, Petruzzi MJ, et al. Anaplastic Wilms’ tumour, a subtype displaying poor prognosis, harbours p53 gene mutations. Nat Genet. 1994;7:91–97. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faria P, Beckwith JB, Mishra K, et al. Focal versus diffuse anaplasia in Wilms tumor—New definitions with prognostic significance: A report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:909–920. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199608000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dome JS, Cotton CA, Perlman EJ, et al. Treatment of anaplastic histology Wilms’ tumor: Results from the fifth National Wilms’ Tumor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2352–2358. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, et al. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borovski T, De Sousa EMF, Vermeulen L, et al. Cancer stem cell niche: The place to be. Cancer Res. 2011;71:634–639. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu FX, Zhao B, Panupinthu N, et al. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. 2012;150:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao B, Tumaneng K, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:877–883. doi: 10.1038/ncb2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong W, Guan KL. The YAP and TAZ transcription co-activators: Key downstream effectors of the mammalian Hippo pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:785–793. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiemer SE, Varelas X. Stem cell regulation by the Hippo pathway. Biochim Biophys acta. 2013;1830:2323–2334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenbluh J, Nijhawan D, Cox AG, et al. beta-Catenin-driven cancers require a YAP1 transcriptional complex for survival and tumorigenesis. Cell. 2012;151:1457–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Hibbs MA, Gard AL, et al. Genome-wide analysis of N1ICD/RBPJ targets in vivo reveals direct transcriptional regulation of Wnt, SHH, and hippo pathway effectors by Notch1. Stem cells. 2012;30:741–752. doi: 10.1002/stem.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konsavage WM, Jr, Kyler SL, Rennoll SA, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates Yes-associated protein (YAP) gene expression in colorectal carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11730–11739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aragon E, Goerner N, Zaromytidou AI, et al. A Smad action turnover switch operated by WW domain readers of a phosphoserine code. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1275–1288. doi: 10.1101/gad.2060811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barry ER, Morikawa T, Butler BL, et al. Restriction of intestinal stem cell expansion and the regenerative response by YAP. Nature. 2013;493:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang W, Tong JH, Chan AW, et al. Yes-associated protein 1 exhibits oncogenic property in gastric cancer and its nuclear accumulation associates with poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2130–2139. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muramatsu T, Imoto I, Matsui T, et al. YAP is a candidate oncogene for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:389–398. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu MZ, Yao TJ, Lee NP, et al. Yes-associated protein is an independent prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115:4576–4585. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katoh M. Function and cancer genomics of FAT family genes (review) Int J Oncol. 2012;41:1913–1918. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao B, Li L, Tumaneng K, et al. A coordinated phosphorylation by Lats and CK1 regulates YAP stability through SCF(beta-TRCP) Genes Dev. 2010;24:72–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1843810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reginensi A, Scott RP, Gregorieff A, et al. Yap- and Cdc42-dependent nephrogenesis and morphogenesis during mouse kidney development. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saburi S, Hester I, Fischer E, et al. Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1010–1015. doi: 10.1038/ng.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alami J, Williams BR, Yeger H. erivation and characterization of a Wilms’ tumour cell line, WiT 49. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:365–374. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovvorn HN, Westrup J, Opperman S, et al. CITED1 expression in Wilms’ tumor and embryonic kidney. Neoplasia. 2007;9:589–600. doi: 10.1593/neo.07358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy AJ, Pierce J, de Caestecker C, et al. SIX2 and CITED1, markers of nephronic progenitor self-renewal, remain active in primitive elements of Wilms’ tumor. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:1239–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikolaev SI, Rimoldi D, Iseli C, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic MAP2K1 and MAP2K2 mutations in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:133–139. doi: 10.1038/ng.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zang ZJ, Cutcutache I, Poon SL, et al. Exome sequencing of gastric adenocarcinoma identifies recurrent somatic mutations in cell adhesion and chromatin remodeling genes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:570–574. doi: 10.1038/ng.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]