SUMMARY

Patients with systemic autoimmune diseases show increased incidence of atherosclerosis. However, the contribution of proatherogenic factors to autoimmunity remains unclear. We found that atherogenic mice (herein referred to as LDb mice) exhibited increased serum interleukin-17 (IL-17), which was associated with increased numbers of Th17 cells in secondary lymphoid organs. The environment within LDb mice was substantially favorable for Th17 cell polarization of autoreactive T cells during homeostatic proliferation, and this was substantially inhibited by antibodies directed against oxidized LDL (oxLDL). Moreover, the uptake of oxLDL induced dendritic cell-mediated Th17 polarization by triggering IL-6 production in a process dependent on TLR4, CD36, and MyD88. Furthermore, self-reactive CD4+ T cells expanded in the presence of oxLDL induced more profound experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. These findings demonstrate that proatherogenic factors promote the polarization and inflammatory function of autoimmune Th17 cells, which may be critical for the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and other related autoimmune diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease manifesting the arterial wall, and is the leading cause of mortality in the developed countries. This vascular disease is caused by imbalanced lipid metabolism and hyperlipidemia, leading to the passage of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) into the subendothelial area of the artery. Within this site, LDL is oxidized to produce oxidized LDL (oxLDL) by multiple biochemical mediators and enzymes. While LDL is captured by the LDL receptor, oxLDL is recognized by different receptors including the oxLDL receptor (LOX-1), CD36, several toll-like receptors (TLRs), scavenger receptor SR-B1, and CD205 (Goyal et al., 2012). oxLDL is a potent inducer of inflammatory mediators including MCP-1, TNFα, and IL-1β, as well as cell adhesion molecules VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, which mediate the recruitment of macrophages and other inflammatory cells into the subendothelial area (Hansson and Hermansson, 2011). In addition, oxLDL can also exert anti-inflammatory functions by activating the PPARγ pathway in macrophages (Chawla et al., 2001; Moore et al., 2001; Nagy et al., 1998). Thus, oxLDL is a pluripotent mediator that orchestrates multiple pathways.

A number of studies have demonstrated a crucial contribution of both innate and adaptive immunity to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (Libby et al., 2013). For instance, the pathogenic role of macrophages in atherosclerosis includes local activation of innate immunity and recruitment of inflammatory cells into the vascular lesions. Accordingly, blockade of monocyte and macrophage migration into the intima by targeting chemokine receptors (e.g. CCR2, CCR5) significantly ameliorates atherosclerosis in experimental animal models (Potteaux et al., 2006; Saederup et al., 2008; Tacke et al., 2007); this approach is now under clinical investigation (Koenen and Weber, 2010). In addition, accumulating evidence strongly suggests the involvement of adaptive T cell responses in atherosclerosis. For instance, the pathogenic association of Th1 cell immunity has been well documented; IFNγ-producing Th1 cells are found in vascular lesions, and mice lacking the Th1 transcription factor T-bet, IFNγ or IFNγ receptor are resistant to high fat diet-induced atherosclerosis (Gupta et al., 1997; Laurat et al., 2001; Tellides et al., 2000). In addition, recent studies reported that IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells (Th17) are found in the atherosclerotic lesions of both mice and humans; however, the importance of IL-17 and Th17 cell responses remains debatable (Danzaki et al., 2012; Eid et al., 2009; Erbel et al., 2009). Hence, aberrant activation of both innate and adaptive immune responses critically contributes to the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis.

The activation of innate immunity by proatherogenic factors including oxLDL is well characterized, however, few studies to date have addressed whether such factors play a role in shaping adaptive T cell responses. In this regard, it is noteworthy that patients with chronic autoimmune disorders including rheumatoid arthritis (Goodson et al., 2005; Stamatelopoulos et al., 2009), psoriasis (Kimball et al., 2008; Krueger and Duvic, 1994), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Manzi et al., 1997; Roman et al., 2003) have a substantially higher incidence of atherosclerosis. Despite these tight link between the T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases and atherosclerosis, little is known about the underlying mechanisms by which proatherogenic factors modulate autoimmune T cell responses, or vice versa. Among helper T cell subsets, Th17 cells appear to be the most pathogenic in experimental animal models of multiple sclerosis, lupus, arthritis, and psoriasis. Moreover, clinical trials using antibodies directed against IL-17 showed favorable clinical outcomes, indicating the importance of IL-17 and Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and arthritis in humans (Genovese et al., 2010; Hueber et al., 2010; Leonardi et al., 2012).

Mice lacking both LDL receptor and apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme Apobec1 genes (Ldlr−/−Apobec1−/−, or LDb mice) are hyperlipidemic and prone to atherosclerosis. They spontaneously develop atherosclerotic plaques by the age of 5 months when maintained on a normal chow diet (Dutta et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2004). Unexpectedly, we observed a preferential accumulation of effector-memory Th17 cells in the secondary lymphoid organs as well as increased serum amounts of IL-17 in the LDb mice. In vitro and in vivo studies revealed that oxLDL, but not native LDL, profoundly induced the polarization and expansion of Th17 cells by inducing IL-6 production from dendritic cells in a MyD88-dependent fashion. Furthermore, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-reactive T cells cultured in the presence of oxLDL exhibited enhanced Th17 cell polarization, migrated more efficiently into the central nervous system, and triggered more profound EAE. These findings identify proatherogenic factors as critical contributors to autoimmune Th17 cell responses.

RESULTS

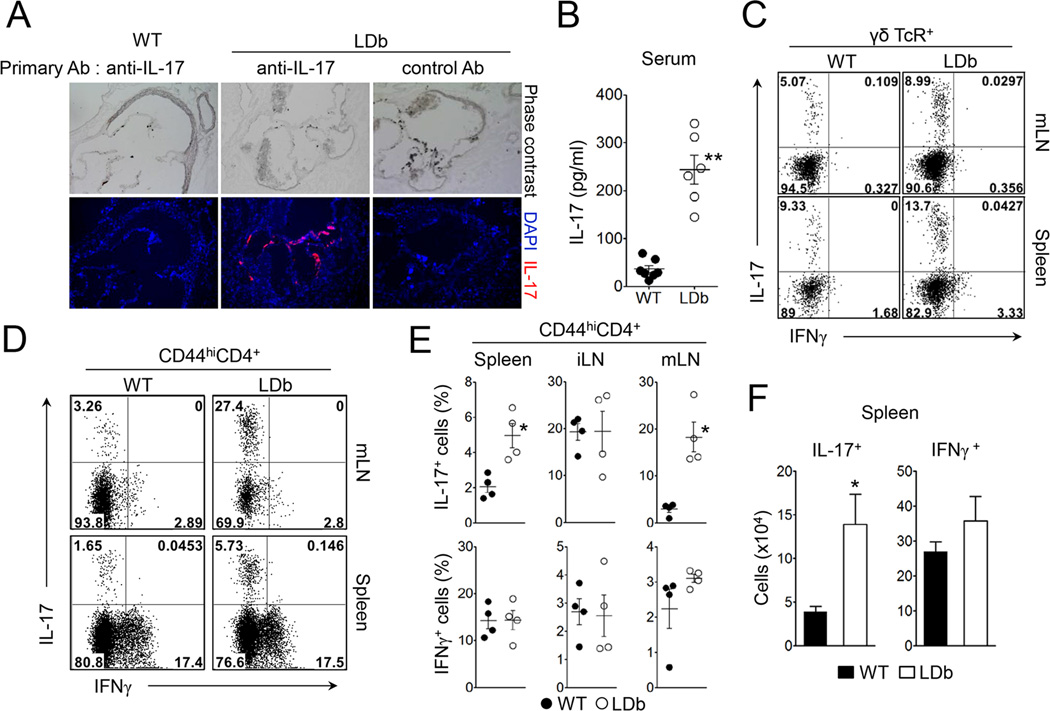

Atherogenic LDb mice have increased IL-17 in circulation and in the aortic sinus

As a first step to investigate the role of proatherogenic conditions on the regulation of adaptive immunity, we examined metabolic and atherosclerotic parameters of LDb mice maintained on regular chow diet. Consistent with previous studies (Dutta et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2004), LDb mice had significantly elevated levels of total cholesterol as well as triglyceride compared to those of wild-type mice (Figure S1A). The LDb mice developed atherosclerotic lesions in aortic sinus by 4–5 month of age (Figure 1A). The total body weight and the percentage of fat weight of the LDb mice were similar to wild-type mice (Figure S1B), indicating that the atherosclerosis in the LDb mice was independent of obesity. Because IL-17-producing cells are found in atherosclerotic lesions in mice and humans (Eid et al., 2009; Erbel et al., 2009), we stained the aortic sinus with anti-IL-17 and found that IL-17 was highly expressed in tissues derived from LDb mice (Figure 1A). Similarly, we also found that the LDb mice exhibited higher serum levels of IL-17 compared to wild-type mice (Figure 1B). These results demonstrate that LDb mice develop hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis with concomitant increases of IL-17 in circulation as well as within the aortic sinus.

Figure 1. LDb mice exhibit increased Th17 cell population.

(A) The expression of IL-17 in aortic sinus in LDb or wild-type mice. Aortic sinus sections obtained from LDb or wild-type mice (4 month-old) were stained with isotype control or anti-IL- 17 polyclonal antibody (red) and DAPI (blue). (B) IL-17 levels in serum obtained from LDb or wild-type mice were measured (n=6). (C) IL-17 and IFNγ expression on γδTcR+ cells from the spleen or mesenteric lymph nodes of LDb and wild-type mice. (D and E) IL-17 and IFNγ expression on CD44hiCD4+ T cells from the spleen, inguinal lymph nodes (iLN) or mesenteric lymph nodes (mLN) of LDb and wild-type mice. (F) Absolute numbers of IL-17- and IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells in the spleens (n=4). Data represent three independent experiments. Data shown are mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01 in comparison with wild-type mice. See also Figure S1 to S4.

To study the immune system of LDb mice, we first analyzed various lymphoid populations in the secondary lymphoid tissues and the thymus. The frequencies of CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells in the spleen of LDb mice were normal; however, the splenic cellularity of LDb mice was significantly lower than that of wild-type mice (Figure S2A & B). Similarly, the cellularity contained within the peripheral lymph nodes was also decreased in LDb mice (data not shown). Notably, LDb mice exhibited an increased frequency of the CD44hi population among the CD4+ T cells (Figure S2C). The thymus of LDb mice showed decreased frequencies of CD4 and CD8 single positive cells, accompanied with increased frequency of CD4+CD8+ cells (Figure S2D). Of interest, the frequency of Foxp3+ regulatory T cell (Treg) among the CD4+ T cell population was higher in the secondary lymphoid tissues as well as in the thymus of LDb mice compared to wild-type mice. However, the absolute number of this T cell subset was significantly lower in the LDb mice due to decreased cellularity (Figure S3A to C). Treg cells from LDb mice were equally suppressive to the proliferation of naïve CD4+ T cells in vitro when compared to wild-type Treg cells (Figure S3D). Taken together, these results indicate that proatherogenic LDb mice have decreased cellularity but increased frequencies of effector-memory CD4+ T cells and Treg cells in secondary lymphoid organs.

LDb mice have increased numbers of IL-17-producing T cells

Our observation of increased IL-17 in the LDb mice led us to examine the primary source of IL-17, which is most likely derived from γδ T cells or effector-memory CD4+ T cells. As shown in Figure 1C, we observed a moderate but significant increase in the frequencies of IL-17-producing γδ+ T cells in LDb mice compared to wild-type mice (WT vs LDb, in the mesenteric LNs (mLN): 5.05 ± 0.14 vs 9.40 ± 1.29, p=0.028; in the spleens: 8.46 ± 0.44 vs 12.13 ± 0.92, p=0.023). Likewise, there was an even more substantial increase in the percentages of IL-17-producers among CD44hiCD4+ T cells in the spleens and mLNs of the LDb mice compared to wild-type mice (Figure 1D & E). Conversely, we observed comparable percentages of IFNγ-producing cells among CD44hiCD4+ T population in the LDb and wild-type mice (Figure 1D & E). When restimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3, CD44hiCD4+ T cells from LDb mice produced higher amounts of IL-17 than those from wild-type mice (Figure S4A). Despite the low cellularity, the absolute number of IL-17-producing CD44hiCD4+ T cells in the spleen was significantly higher in the LDb mice than that in the wild-type mice, while that of IFNγ-producing CD44hiCD4+ T cells was comparable between the two groups (Figure 1F). To further characterize the effector-memory CD4+ T cells in LDb mice, we analyzed gene expression in CD44hiCD4+ T cells. We observed that CD44hiCD4+ T cells from LDb mice expressed increased mRNA for Rorc, Irf4, Il23r, Il1r1, Il21, Il22, Csf2 (encoding GM-CSF), and Hif1a while the expression of Rora, Ahr, foxp3, Tbx21, Ifng and Il10 was similar to those of wild-type mice (Figure S4B). Taken together, these results demonstrate that LDb mice have a preferential increase in Th17 cell population.

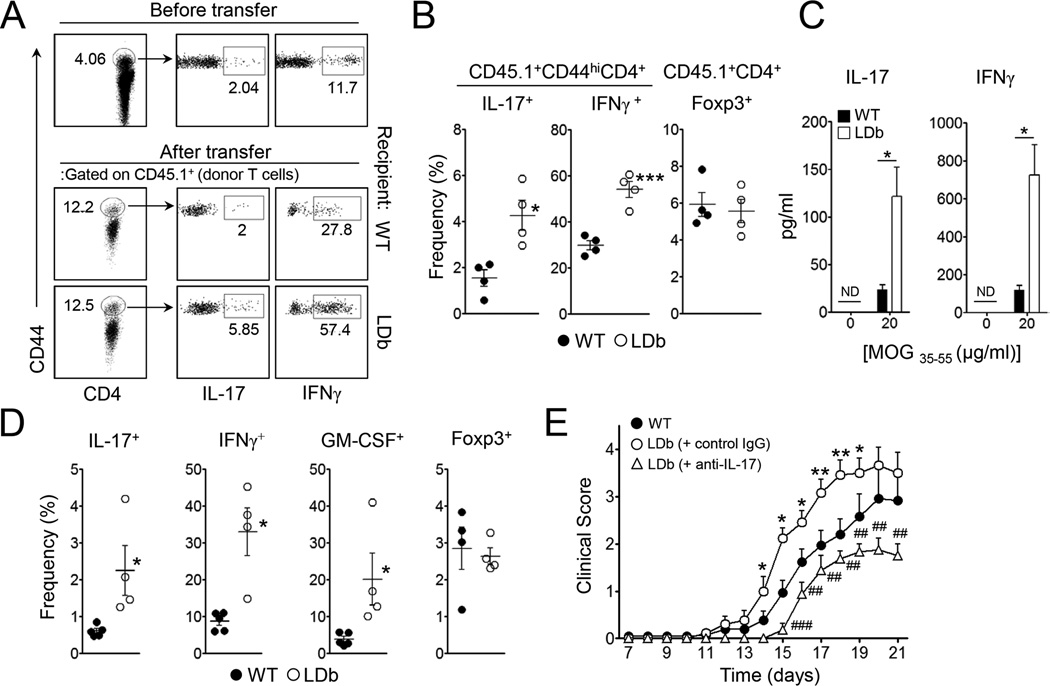

LDb mice promote autoreactive Th17- and Th1-cell responses in vivo

The preferential increase of the Th17 cell population in LDb mice prompted us to hypothesize that proatherogenic conditions in vivo promote the generation of autoreactive Th17 cell responses without exogenous inflammatory stimuli. To address this point, we employed 2D2 transgenic T cells whose T cell receptor specifically recognizes myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35–55), an MHC class II-restricted neuroantigen. To rule out any possible involvement of the dysregulated cellular populations present in the host immune system, we first sublethally irradiated wild-type and LDb mice before transferring total splenocytes derived from CD45.1+ 2D2 donor mice. Additionally, all recipient mice were injected i.p. with anti-CD25 to further deplete Treg cells since they are known to be resistant to irradiation (Komatsu and Hori, 2007). Within 7 days of reconstitution, the percentage of the CD44hi population among CD45.1+2D2 donor CD4+ T cells was increased from ~4.5% to ~12% (Figure 2A). As expected, we observed that the majority of CD44hi cells among the CD45.1+CD4+ T cell population in the recipients were IFNγ-producers as a result of homeostatic proliferation. Interestingly, the frequencies of IL-17-producing cells as well as IFNγ-producing cells among the CD45.1+CD44hiCD4+ population were significantly higher in the LDb recipient mice compared to wild-type recipients (Figure 2A & B), while the frequency of Foxp3+ Treg cells among donor T cells was comparable between the two groups (Figure 2B). Moreover, when the splenocytes of the recipients were cultured with cognate peptide, the amounts of IL-17 and IFNγ produced were far higher in the LDb recipients (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. LDb mice promote Th17 and Th1 cell responses of self-reactive CD4+ T cells in vivo.

Total splenocytes from 2D2 mice (CD45.1+) were i.v. transferred into sublethally irradiated LDb or wild-type mice (CD45.2+, n=4). The recipients remained without further treatment (A–C), or were additionally immunized with MOG35–55 in CFA (D and E). (A and B) The frequencies of IL-17- or IFNγ-producers among CD44hi donor CD4+ T cells and Foxp3+ cells among donor CD4+ T cells in the spleens. (C) The amounts of IL-17 and IFNγ in the supernatant after 3 days culture of splenocytes with cognate peptide. (D) The frequencies of IL-17+, IFNγ+, GM-CSF+ or Foxp3+ cells among donor CD4+ T cells in the spleens 2 weeks after immunization. (E) Daily clinical scores of EAE (n=10–12). Data represent two independent experiments. Data shown are mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001 in comparison with wild-type. ##, p<0.01; ###, p<0.001 in comparison with control IgG injected LDb mice.

Despite the increased production of IL-17 and IFNγ by the donor 2D2 T cells, the recipients showed no signs of CNS inflammation (data not shown). Therefore, to address the importance of the proatherogenic environment on autoimmune CNS inflammation, we immunized the recipient mice with MOG in CFA. As depicted in Figure 2D, the frequencies of donor CD4+ T cells producing IL-17, IFNγ, or GM-CSF were all higher in the spleens of the LDb recipients than those of wild-type mice. The Foxp3+ Treg population between the two groups was comparable. More importantly, clinical symptoms of EAE were more severe when LDb mice served as recipients (Figure 2E). We next sought to determine if the enhanced IL-17 observed in LDb recipients is the primary factor driving increased severity of EAE. Anti-IL-17 treatment in the same model system significantly ameliorated the clinical severity of EAE where the mean clinical scores of anti-IL-17-treated LDb mice were comparable to that of wild-type mice (Figure 2E). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the proatherogenic in vivo environment of the LDb mice triggered Th17 and Th1 cell responses in MOG-specific self-reactive CD4+ T cells and promoted more profound CNS inflammation upon autoimmune stimulation in an IL-17 dependent manner.

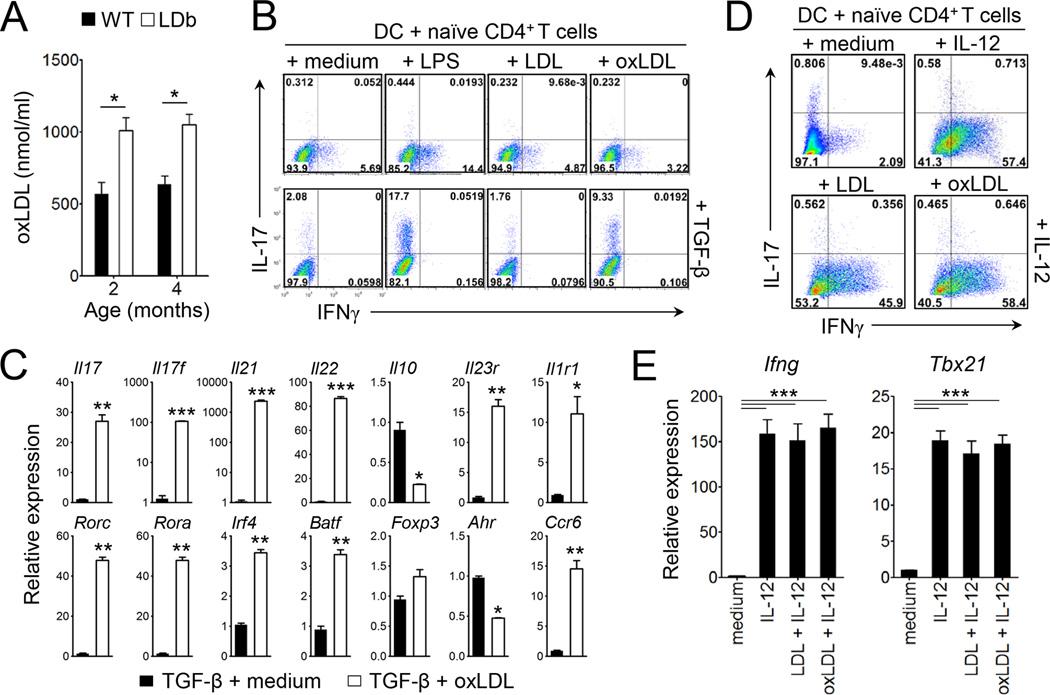

Oxidized LDL promotes dendritic cell-mediated Th17 cell polarization

The observed increase of the Th17 and Th1 cell populations in steady state as well as during homeostatic proliferation in LDb mice prompted us to hypothesize that proatherogenic factors promote Th17 and/or Th1 cell responses. LDb mice were previously shown to exhibit elevated amounts of LDL (Dutta et al., 2003). Moreover, LDb mice exhibited higher concentration of oxLDL in circulation compared to wild-type animals (Figure 3A). To address if these proatherogenic factors modulate helper T cell polarization, we employed a T cell:dendritic cell (DC) co-culture system in which stimulation with LPS plus TGF-β and soluble anti-CD3 induces the polarization of Th17 cells from naïve CD4+ T cells (Veldhoen et al., 2006). When native LDL was added instead of LPS, we observed little change in the frequency of IL-17-producing T cells (< 2 %). In contrast, the addition of oxLDL (TBars = 25–35) greatly increased the frequency of IL-17-producing T cells in the presence of TGF-β (Figure 3B). CD4+ T cells cultured under this condition expressed significantly increased amounts of Th17 cell signature genes including Il17, Il17f, Il21, Il22, Rorc, Rora, Irf4, Batf, Ccr6, Il23r, Il1r1 transcripts, whereas the transcript levels of Il10 and Ahr were lower than those of CD4+ T cells cultured without oxLDL (Figure 3C). Similarly, the addition of acetylated LDL also promoted the generation of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells (Figure S5A & B). Conversely, both LDL and oxLDL did not increase the frequency of IFNγ-producing Th1 cells (Figure 3B upper panels). Furthermore, the addition of LDL or oxLDL with IL-12 had no effect on Th1 differentiation and the expression of Ifng and Tbx21 transcripts (Figure 3D & E). In addition, oxLDL seemed to play no role for the generation of Foxp3+ Treg cells from naïve T cells in vitro (Figure S6). Thus, modified LDLs, but not native LDL, induced dendritic cell-mediated Th17 cell differentiation while minimally affected Th1 cell differentiation in vitro.

Figure 3. Oxidized LDL promotes dendritic cell-mediated Th17 cell differentiation in vitro.

(A) Concentration of oxLDL in serum at the age of 2 or 4 month of wild-type and LDb mice (n=4–5). (B–E) Purified naive CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with bone marrow-derived DC in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 under the indicated conditions for 4 days. (B and D) The frequencies of IL-17- or IFNγ-producers among CD4+ T cells. (C and E) The levels of mRNA transcripts of the indicated genes. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data shown are mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05; **,p<0.01; ***,p<0.001. See also Figure S5 and S6.

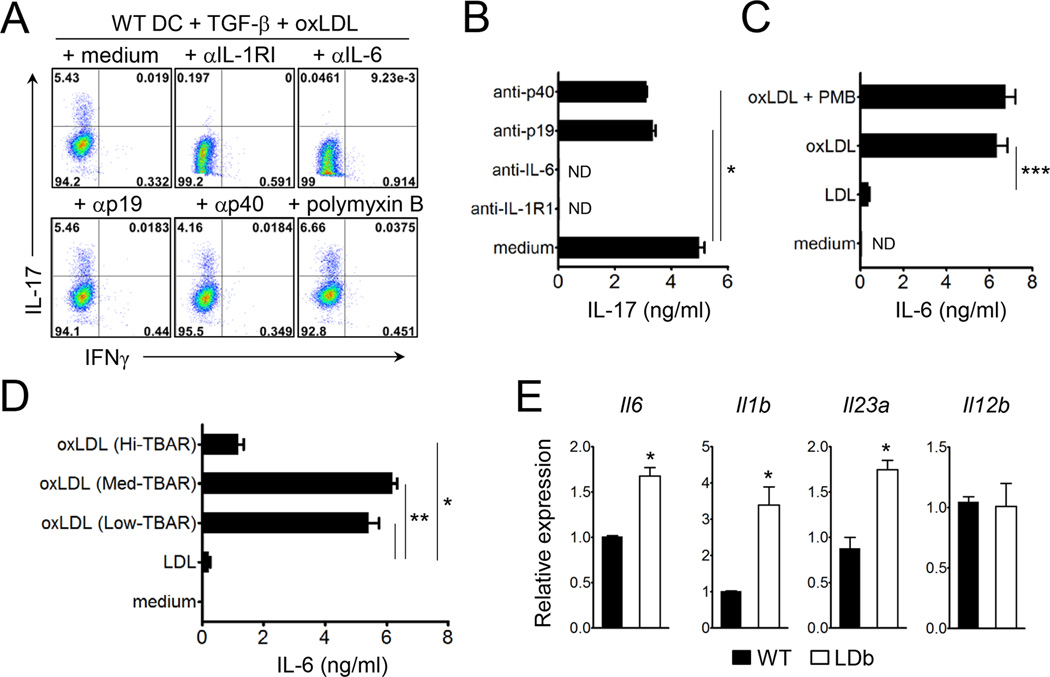

IL-6, IL-1, and IL-23 have been shown to be crucial in Th17 cell lineage commitment. To address possible mechanisms for the observed oxLDL-mediated Th17 cell differentiation, we added neutralizing antibodies to IL-6, IL-23p19, IL-12p40, or IL-1R1 during a similar set of co-culture experiments. As shown in Figure 4A & B, neutralization of IL-6 almost completely abolished the generation of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells. Addition of IL-1R1 blocking antibody also inhibited the polarization of Th17 cell, but the intensity of such inhibition varied ranging from 30% to 96%. Alternatively, antibodies against IL-23p19 or IL-12p40 only marginally affected the differentiation of Th17 cells (Figure 4A & B). To further examine the involvement of IL-6, we stimulated DC with native LDL or oxLDL, and found that oxLDL triggered the production of IL-6, whereas native LDL failed to do so (Figure 4C). Interestingly, the capacity of oxLDL to induce IL-6 was dependent on the extent of oxidation; oxLDL with low and medium TBars value (TBars = 5–15 and 25–35, respectively) induced similar degrees of IL-6 production from DCs while oxLDL with high TBars value (TBars = 50–70) failed to do so (Figure 4D). The levels of endotoxin in the LDL and oxLDLs used were below the detectable range in an LAL assay (<0.5 EU/mg). Moreover, the addition of polymyxin B did not affect the production of IL-6 (Figure 4C), ruling out any possible role of endotoxin contamination. Due to the potency of oxLDL with medium TBars in inducing IL-6 from DCs, we utilized this reagent for the rest of studies.

Figure 4. Oxidized LDL induces the production of Th17 cell promoting cytokines.

(A and B) Naive CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with bone marrow-derived DC under the indicated conditions in the presence or absence of indicated antibodies for 4 days. (A) The frequencies of IL-17- or IFNγ-producers among CD4+ T cells. (B) IL-17 production by CD4+ T cells after stimulation with plate-bound anti-CD3 (1 µg/ml). (C and D) IL-6 production by bone marrow-derived DCs after stimulation with 20 µg/ml LDL or oxLDL (Medium Tbar) (C), or with 20 µg/ml oxLDL with Hi-, Medium- or Low Tbars (D). (E) Relative mRNA expression of indicated genes in the freshly purified CD11c+ DCs from the spleens of LDb and wild-type mice. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data shown are mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. ND, not detected.

Primary DCs in LDb mice showed a similar phenotype to oxLDL-stimulated DCs in vitro. CD11c+ DCs purified from the spleen of LDb mice expressed higher amounts of Il6, Il1b, and Il23a mRNA transcripts than those from wild-type mice (Figure 4E), suggesting that the proatherogenic in vivo condition, potentially mediated through oxLDL, stimulated DCs to produce a variety of the Th17 cell-promoting cytokines.

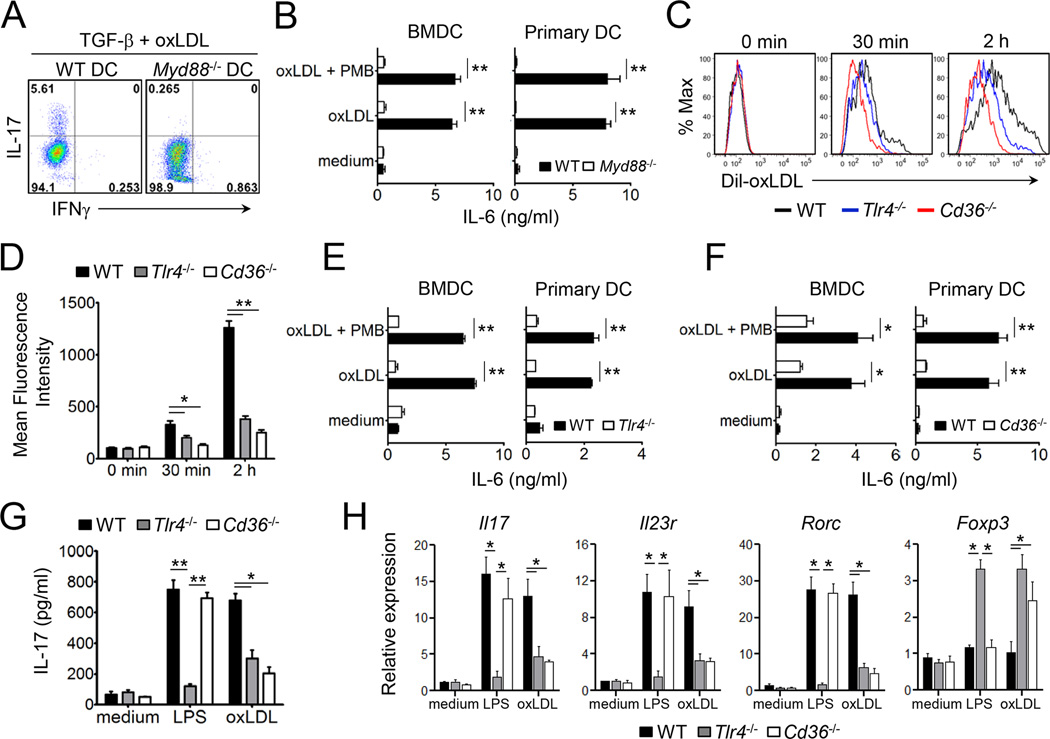

TLR4, CD36 and MyD88 are required for the Th17 cell differentiation induced by oxLDL

Cell surface molecules identified as receptors for oxLDL include LOX-1, CD36, TLR4, SR-B1, and CD205. In addition, a recent study revealed MyD88 as a downstream adaptor to promote sterile inflammation in macrophages in response to oxLDL and amyloid-β eptide (Stewart et al., 2010). Thus we asked if Th17 cell differentiation induced by oxLDL requires MyD88 expression in DC. As shown in Figure 5A, MyD88-deficient DCs failed to induce Th17 cell polarization in the presence of oxLDL and TGF-β. Similarly, the amounts of IL-6 produced by MyD88-deficient DC (both bone-marrow derived- and primary DC) were far lower than those by wild-type DC (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. TLR4, CD36, and MyD88 are essential for the oxLDL-mediated differentiation of Th17 cells.

(A) The frequencies of IL-17- or IFNγ-producers among CD4+ T cells co-cultured with wild-type or Myd88−/− DC under the indicated conditions. (B) Production of IL-6 from freshly isolated DCs or bone marrow-derived DCs after stimulation with oxLDL (20 µg/ml). (C and D) The uptake of Dil-oxLDL by DC freshly isolated from the spleens of wild-type, Tlr4−/−, or Cd36−/− mice. (E and F) Production of IL-6 by freshly isolated or bone marrow-derived DCs from wild-type, Tlr4−/− (E) or Cd36−/− (F) mice (n=3–4) after stimulation with oxLDL. (G and H) Naïve CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with bone marrow-derived DCs from wild-type, Tlr4−/− or Cd36−/− mice plus soluble anti-CD3 and TGFβ in the presence or absence of LPS or oxLDL for 4 days. The production of IL-17 by T cells (G), and the levels of mRNA transcripts of the indicated genes (H). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data shown are mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

Because MyD88 was necessary for the differentiation of Th17 cells and IL-6 production from DC induced by oxLDL, we hypothesized TLR4 acts as a receptor for oxLDL during this process. In addition, CD36 is known to be required for the production of IL-1β from macrophages in response to oxLDL (Janabi et al., 2000; Stewart et al., 2010). To test which factors are important for oxLDL-mediated Th17 cell differentiation, we examined the function of TLR4 and CD36. The uptake of a fluorescence dye-labeled oxLDL (Dil-oxLDL), measured by the mean fluorescence intensity of Dil-oxLDL present in DC, was far less efficient in both TLR4- and CD36-deficient DC compared to wild-type cells (Figure 5C & D). Moreover, oxLDL induced IL-6 production from primary and bone marrow-derived DCs, but not when TLR4 or CD36 were absent (Figure 5E & F). Consequently, CD4+ T cells cultured with TLR4- or CD36-deficient DCs in the presence of oxLDL and TGF-β induced significantly less IL-17 and Th17 cell signature genes while triggering increased expression of Foxp3 compared to those cultured with wild-type DCs (Figure 5G & H). It is noteworthy that CD36-deficient DC induced normal Th17 cell differentiation when stimulated with LPS and TGF-β, further indicating that the Th17 cell promoting capacity of oxLDL is mechanistically different from endotoxin. Taken together, these results demonstrate that oxLDL requires TLR4 and CD36 as well as the intracellular adaptor MyD88 to induce IL-6 and subsequent Th17 cell differentiation in our experimental setting.

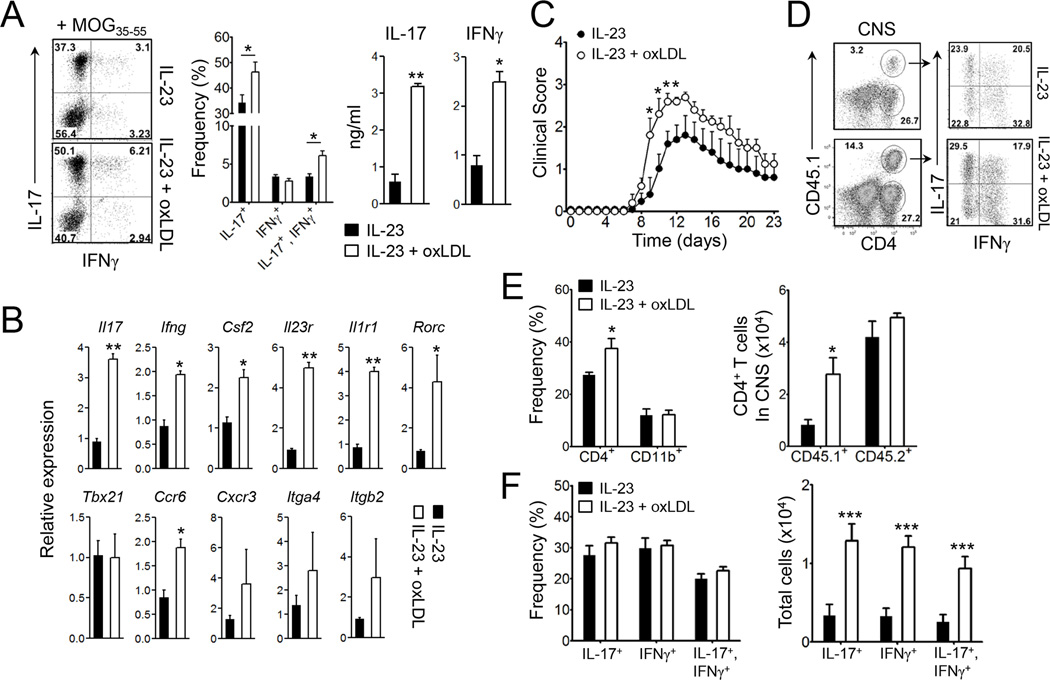

MOG-reactive T cells expanded in the presence of oxLDL induces severe EAE

We next determined if oxLDL can promote autoantigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses in vivo. To this end, we immunized B6.SJL mice with MOG35–55 emulsified in CFA. One week later, we obtained lymphoid cells from the draining LNs before restimulating them with the same peptide ex vivo. In some wells, we additionally added IL-23 and/or oxLDL. As depicted in Figure 6A, the addition of oxLDL significantly increased the frequency of IFNγ−IL-17+ cells and the production of IL-17 and IFNγ from the MOG-reactive CD4+ T cells. OxLDL also slightly increased the frequency of IFNγ+IL-17+ but not IFNγ+IL-17− T cells (Figure 6A). Thus, the enhanced production of IFNγ is likely due to an increase of Th17 cells co-expressing IFNγ rather than due to the expansion of Th1 cells. Compared with IL-23 alone, CD4+ T cells stimulated with IL-23 and oxLDL expressed significantly higher Il17, Ifng, Csf2, Ccr6, Il1r1, Il23r mRNA transcripts whereas the expression of Tbx21, Cxcr3, Itga4 (encoding α-subunit of VLA-4) and Itgb2 (encoding β-subunit of LFA-1) transcripts remained comparable (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. MOG-reactive T cells expanded in the presence of oxLDL induces enhanced EAE.

Lymphoid cells from the draining LNs of B6.SJL mice (CD45.1+) that were previously immunized with MOG35–55 in CFA were restimulated with the same peptide in the presence or absence of oxLDL and IL-23 for 5 days. (A) Production of IL-17 and IFNγ by CD4+ T cells and (B) mRNA levels of the indicated genes. (C–F) The ex vivo expanded MOG35–55-reactive CD4+ T cells (1×106 cells/transfer) were i.v. transferred into congenic recipients (CD45.2+), which were then immunized with MOG35–55 in CFA (n=9–10). (C) The clinical severity of EAE. (D and F) the frequencies and absolute numbers of IL-17- or IFNγ-producing donor CD4+ T cells in the CNS tissues. (E) The proportion and absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD11b+ cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Data shown are mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. See also Figure S7.

To further investigate if oxLDL stimulation affects the pathogenicity of MOG-reactive CD4+ T cells, we adoptively transferred the expanded MOG-reactive CD4+ T cells (CD45.1+/+) into C57BL/6 mice before the recipients were s.c. immunized with MOG35–55 in CFA. Notably, the clinical severity during the early and peak phases of EAE was significantly higher in the recipients of the IL-23 plus oxLDL-stimulated T cells than those of the IL-23-stimulated T cells (Figure 6C). In the draining LNs, donor T cells that were previously cultured with IL-23 plus oxLDL exhibited higher percentages of IL-17- and IFNγ-producing population than those in the recipients of T cells stimulated with IL-23 alone (Figure S7). Importantly, we observed higher numbers of infiltrating CD4+ T cells in the CNS in the former group, mainly due to higher numbers of CD45.1+ donor T cells, while the numbers of host CD4+ T cells were comparable (Figure 6D & E). The percentages of IL-17- and IFNγ-producers among the CD45.1+ donor T cell population in the CNS were similar between these two groups (Figure 6D & F). Nevertheless, due to the higher frequencies of donor T cells in the CNS, the absolute numbers of IL-17- and IFNγ-producers were significantly higher in the recipients of IL-23 plus oxLDL stimulated T cells (Figure 6F). Collectively, these results indicate that the addition of oxLDL during the ex vivo expansion of MOG-reactive CD4+ T cells rendered the T cells more pathogenic in inducing autoimmune CNS inflammation.

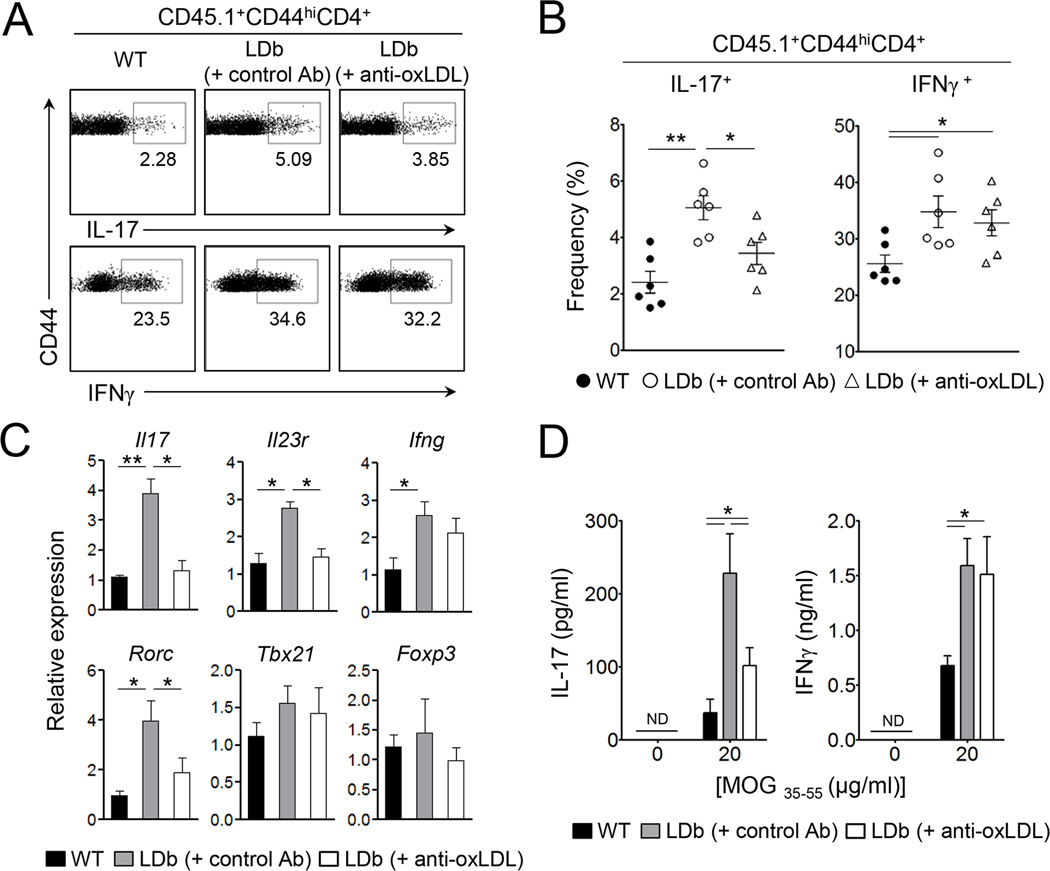

oxLDL plays a crucial role for the enhanced autoreactive Th17 cell responses in LDb mice

Our findings that LDb mice had an increased Th17 cell population and elevated amounts of oxLDL in circulation (Figure 1 & 3A), that oxLDL induced enhanced Th17 cell responses in a DC-mediated differentiation of Th17 cells in vitro (Figure 3 to 5), and that oxLDL enhanced Th17 cell responses in autoreactive T cells ex vivo (Figure 6) led us to hypothesize that oxLDL plays a crucial role in autoimmune Th17 cell differentiation in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we examined if neutralization of oxLDL suppresses the differentiation of autoreactive Th17 cells in LDb mice by employing the 2D2 splenocytes transfer model used in Figure 2. The LDb recipient mice were additionally administered neutralizing anti-oxLDL (clone E06) or isotype control Ab (mouse IgM). Clone E06 anti-oxLDL was previously shown to block the uptake of oxLDL by macrophages (Horkko et al., 1999; Palinski et al., 1996). As depicted in Figure 7A and B, the frequency of IL-17-producers among CD45.1+CD44hiCD4+ donor T cells was significantly decreased in LDb recipients treated with anti-oxLDL compared to control Ab-treated LDb recipients. Conversely, the frequency of IFNγ-producers in the LDb recipients was not remarkably affected by anti-oxLDL treatment (Figure 7A & B). The percentage of IL-17+ among CD44hiCD4+ donor T cells in the anti-oxLDL treated LDb mice was still higher than that of wildtype mice, although the difference did not reach statistical significance. Gene expression analysis showed that anti-oxLDL treatment greatly decreased the mRNA expression of Il17, Il23r, Rorc while not affecting the expression of Ifng, Tbx21 and Foxp3 (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. Anti-oxLDL diminishes autoreactive Th17 cell responses in LDb mice.

Total splenocytes from 2D2 mice (CD45.1+) were i.v. transferred into sublethally irradiated LDb or wild-type mice (CD45.2+, n=6) at day 0. LDb recipients were i.p. injected with anti-oxLDL or isotype control antibody at day -1, 1, and 3. (A and B) The frequencies of IL-17- or IFNγ-producers among CD44hi donor CD4+ T cells in the spleens. (C) Transcript levels of indicated genes. (D) The amounts of IL-17 and IFNγ in the supernatant after 3 days culture of splenocytes cells stimulated with MOG33–55 peptide. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Data shown are mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

To further examine the influence of oxLDL in antigen-specific Th1 and Th17 cell responses, we restimulated splenocytes derived from the recipients with MOG peptide. Once again, the production of IL-17 and IFNγ was enhanced in LDb recipients compared to wild-type recipients. However, the amount of IL-17 produced by T cells from LDb recipients was substantially decreased by anti-oxLDL treatment compared to control Ab-treated LDb recipients (Figure 7D). Notably, IL-17 production by T cells from anti-oxLDL-treated LDb recipient mice was still significantly higher than that of wild-type recipients, indicating that anti-oxLDL treatment did not completely abolish the enhancement of Th17 cell responses in LDb mice. However, antioxLDL could not influence IFNγ production by the donor T cells in the LDb recipients. These results together demonstrate that oxLDL plays a crucial role for the enhanced autoreactive Th17 cell responses present in proatherogenic LDb mice.

DISCUSSION

Despite a strong association between atherosclerosis and T cell-mediated systemic autoimmune diseases in humans, the role of proatherogenic factors in regulating adaptive T cell responses and autoimmunity is unclear. Our findings demonstrate that proatherogenic conditions promote autoimmune Th17 cell responses, because (i) non-obese hyperlipidemic LDb mice exhibited a preferential increase in the Th17 cell population in steady state as well as during homeostatic proliferation, (ii) LDb mice were more susceptible to CNS inflammation than wild-type mice in an adoptive transfer EAE model in an IL-17-dependent manner, (iii) oxLDL, but not native LDL, promoted dendritic cell-mediated Th17 cell polarization, (iv) MOG-reactive T cells expanded in the presence of oxLDL triggered more profound EAE, and (v) neutralizing anti-oxLDL significantly inhibited Th17 cell differentiation of auto-reactive T cells in LDb mice. Hence, the present study revealed a previously unknown modulation of adaptive T cell responses by proatherogenic factors, which might explain the association of atherosclerosis and systemic autoimmune diseases in humans.

Increased concentration of LDL is one of the major proatherogenic factors in mediating vascular inflammation. Here, we demonstrated that LDb mice exhibited a significantly higher amount of oxLDL in circulation than wild-type, which was evident as early as 2 months of age. Among several identified receptors for oxLDL, recent studies identified CD36-TLR4-TLR6-MyD88-IRAK4-NFακB axis as a signal pathway mediating the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in macrophages in response to modified LDL (Janabi et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2011; Stewart et al., 2010). By contrast, it has been also reported that CD36-mediated uptake of oxLDL inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines from macrophages through the activation of PPARγ (Chawla et al., 2001; Moore et al., 2001; Nagy et al., 1998). We found that both TLR4 and CD36 were required for the uptake of oxLDL and IL-6 production by DCs. Furthermore, anti-oxLDL significantly suppressed the differentiation of self-reactive 2D2 T cells into Th17 cells in LDb mice in vivo. Thus, we propose that oxLDL promotes DC-mediated Th17 cell polarization in a TLR4-, CD36-, and MyD88-dependent manner.

Atherosclerosis has been considered as an autoimmune disease, as CD4+ T cells reactive to selfantigens such as heat-shock protein 60 and oxLDL were found in atherosclerotic plaques in humans (Grundtman and Wick, 2011; Hansson and Hermansson, 2011). In addition, a few recent studies suggested a possible link between proatherogenic factors and inflammatory T cell responses. For instance, obese mice on high-fat diet are more susceptible to EAE (Winer et al., 2009). Moreover, when human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stimulated with oxLDL, the ratio of Th17 cell to Treg cell was increased (Li et al., 2010). In the present study, we found that proatherogenic environment within LDb mice triggered the differentiation of self-reactive 2D2 T cells into Th17 and Th1 cells more efficiently and promoted more profound CNS inflammation compared to wild-type mice in an IL-17 dependent manner. The finding that anti-oxLDL significantly inhibited the differentiation of Th17 cells in LDb mice strongly suggests a pathogenic role of oxLDL in promoting autoimmune Th17 cell responses in vivo. However, it is not clear if oxLDL is the only major proatherogenic factor responsible for driving Th17 cell responses in LDb mice, and if oxLDL is sufficient to drive autoimmune Th17 cells in vivo. We speculate that multiple proatherogenic factors provide inflammatory signals to promote autoimmune Th17 cell responses in atherosclerosis-prone mice in vivo. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that activation of NLRP3 inflammasome by cholesterol crystals is required for atherogenesis (Duewell et al., 2010). Moreover, free fatty acids that are thought to be pathogenic in diabetes and atherosclerosis are known to signal through inflammasome or TLR4 to trigger the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 β, TNFα, and IL-6 (Shi et al., 2006; Wen et al., 2011). Hence, one can surmise that these proatherogenic factors collaboratively trigger the production of IL-1 β and other pro-inflammatory cytokines, and thus promote Th17 cell responses in vivo. Further studies will be needed to determine in vivo function of oxLDL and other atherogenic factors in autoimmune T cell responses.

The increased Th1 cell population observed in irradiated LDb mice was possibly a result of lymphopenia-dependent homeostatic proliferation, which can cause the conversion of Th17 cells into Th1 cells in lymphopenic host (Martin-Orozco et al., 2009; Nurieva et al., 2009). Alternatively, it is possible that proatherogenic factors other than oxLDL were involved in the expansion of Th1 cells since anti-oxLDL did not inhibit Th1 cell differentiation. The enhanced autoreactive Th17 cell responses observed in the LDb mice is likely not due to the increased Foxp3+ Treg cells since Treg cells in the recipient mice were depleted prior to irradiation and reconstitution. Thus the role of proatherogenic conditions on Treg and Th1 cells is not clear at the moment and further studies will be needed to investigate these pathways.

Functionally, MOG-reactive CD4+ T cells expanded in the presence of oxLDL induced more profound EAE when transferred into naïve congenic mice with higher numbers of infiltrated donor CD4+ T cells in the CNS. Consistent with this notion, co-culture with oxLDL also upregulated the expression of Ccr6, Il23r and Il1r1 in T cells, all of which are known to be essential for the migration Th17 cells into the target tissue where autoimmune inflammation occurs (Chung et al., 2009; Langrish et al., 2005; McGeachy et al., 2009; Yamazaki et al., 2008). The synergistic effect of IL-23 and oxLDL in promoting the Th17 cell lineage program suggests that these two factors may exert similar, but non-redundant, functions in mediating the expansion or functional maturation of initially committed autoreactive Th17 cells.

Several recent studies also proposed the anti-inflammatory functions of cholesterols through the activation of transcription factor LXR in macrophages and in CD4+ T cells (Cui et al., 2011; Spann et al., 2012). Thus, lipid species in a hyperlipidemic individual possibly exert both proand anti-inflammatory responses in vivo depending on their metabolic-, and chemical state. Given the observation that dendritic cells from LDb mice expressed higher amounts of Il1b, Il6, and Il23a transcripts, we speculate that the overall effect of hyperlipidemia in the LDb mice was pro-inflammatory. Whether atherogenic factors directly stimulate auto-reactive T cells is not clear at this time. In the present study, addition of oxLDL during in vitro stimulation of naïve CD4+ T cells under inducible Treg condition did not affect the expression of Foxp3. Future studies will be required to dissect any T cell intrinsic effects of proatherogenic factors during the development of atherosclerosis and autoimmunity in vivo.

In summary, the present study unveils a function of proatherogenic factors in modulating autoimmune Th17 cell responses in mice. Our findings may explain why patients with atherosclerosis exhibit increased incidence of various autoimmune disorders.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

C57BL/6, B6.SJL (CD45.1+/+), Myd88−/−, Tlr4−/−, Cd36−/− and 2D2 TcR transgenic mice were purchased from Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). LDb (Ldlr−/−Apobec1−/− on a C57BL/6 genetic background) mice were generated as described (Dutta et al., 2003). CD45.1×2D2 mice were generated by interbreeding B6.SJL and 2D2 TcR-transgenic mice. All mice were bred and maintained in the specific pathogen free facility at the vivarium of the Institute of Molecular Medicine. All animal experiments were performed using protocols approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas at Houston.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Mouse aortic sinus tissue slides were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and were incubated with goat anti-IL-17 (sc-6077, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or isotype control. The slides were further incubated with Alexa594-conjugated anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen) then were mounted with mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector). The slides were examined by using a Zeiss Axio Observer.D1m fluorescence microscopy with DAPI or Texas Red filters.

Flow Cytometry

Lymphoid cells were obtained and stained with PerCp-Cy5.5 anti-CD4 (GK1.5), APC anti-CD44 (IM7), Alexa647 anti-γδTcR (UC7-13D5), Alexa488 anti-CD11b (1J70), PE anti-CD25 (PC61), Alexa488- anti-CD62L (MEL14), or PacificBlue anti-CD45.1 (A20). Intracellular cytokine staining was performed as previously described (Chung et al., 2009) by using PE anti-IL-17A (TC11-18H10.1), Alexa488 anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2), FITC anti-GM-CSF (MP1-22E9) or Alexa488 anti-Foxp3 (FJK-16s). For oxLDL uptake assay, primary DCs were isolated from the spleen of wild-type, Tlr4−/− or Cd36−/− mice by using CD11c-microbeads. The purified DCs were incubated with 15 µg/ml 1.1’-dioctadecyl-3,3,3’,3’-tetramethyl-indocarbocyanine perchlorate labeled oxLDL (Dil-oxLDL, Biomedical Technologies) for 30 min or 2 hours. After washing, the uptake of Dil-oxLDL by the DC was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cell Isolation and Differentiation

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from Myd88−/−, Tlr4−/−, Cd36−/− or wild-type mice were cultured with FACS-sorted naive CD4+ T cells in the presence of 0.3 µg/ml soluble anti- CD3, TGF-β (3 ng/ml) or IL-12 (10 ng/ml) was added to induce Th17 or Th1 cell polarization, respectively. In some wells, 20 µg/ml LDL, 20 µg/ml oxLDL (Tbars = 25~35), 100 ng/ml LPS, or 1 µg/ml Polymyxin B (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. For cytokine blockade experiments, anti- IL-1R1 (JAMA147), anti-IL-6 (MP5-20F3), anti-IL-23p19 (G23-8), or anti-IL-12p40 (C17.8) was additionally added (all 5 µg/ml). Four days after the culture, the production of cytokines and the expression of genes were analyzed by ELISA, flow cytometry, or quantitative RT-PCR by using primers described in Table S1.

ELISA

The amounts of IL-17, IFNγ, or IL-6 in cultured supernatant or serum were measured by using sandwich ELISA kit (BioLegend). In some experiments, primary DCs were freshly isolated from the spleens of C57BL/6, Myd88−/−, Tlr4−/−, Cd36−/− mice by using anti-CD11c-beads. The isolated primary DCs and BMDCs (1×106 cells/ml) were stimulated with 100 ng/ml LPS, 20 µg/ml LDL, or three types of oxLDLs with differential oxidation extent (low Tbars (5–15), medium Tbars (25–35), high Tbars (50–70); all from Biomedical Technologies). The endotoxin levels of oxLDLs and LDL were <0.5 EU/mg LDL, as measured by an LAL assay (Associates of Cape Cod). Twenty-four hours after stimulation, the levels of IL-6 in the supernatant were measured by ELISA. The oxLDL levels in mouse serum were measured by using ELISA kit (Cusabio Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Induction and Analysis of EAE

Lymphoid cells from the spleens and draining LNs were isolated from B6.SJL mice immunized subcutaneously with 300 µg MOG35–55 emulsified in 100 µl CFA containing killed M. tuberculosis (5 mg/ml) at day 7 after immunization, and then cultured in vitro (5×106 cells/ml) with 20 µg/ml MOG35–55 and 20 ng/ml IL-23 in the presence or absence of 20 µg/ml oxLDL (Tbars: 25~35) for 5 days. CD4+ T cells were purified using anti-CD4 microbeads and i.v. transferred into C57BL/6 mice at day 0 (1×106 cells/transfer). In some experiments, total splenocytes obtained from CD45.1+2D2 mice were i.v. transferred (1×107 cells/transfer) into sublethally irradiated (750 rad) and anti-CD25 antibody-treated (day -3, 300 µg/mice) LDb or wild-type mice (day 0). Some LDb recipients were additionally injected with 200 µg of anti-IL- 17 (17F3) or isotype control (i.p.) every three days starting on day -1. All recipient mice were s.c. immunized with MOG35–55 (300 µg) emulsified in 100 µl CFA containing killed M. tuberculosis (0.5 mg/ml) (day 0) and received 500 ng of pertussis toxin i.p. on day 0 and 2. EAE clinical score was assessed as previously described (Chung et al., 2009).

Homeostatic Proliferation Study

Splenocytes obtained from CD45.1×2D2 mice were transferred (1×107 cells/transfer) intravenously into sublethally irradiated (750 rad) LDb or wild-type recipient mice at day 0. In some experiment, LDb mice were injected i.p. with 250 µg of anti-oxLDL (clone: E06, Avanti Polar Lipids Inc, AL) or mouse IgM as isotype control at day -1, 1, 3. Seven days after the transfer, splenocytes were harvested from the recipient mice. The expression of IL-17 and IFNγ among CD45.1+CD44hiCD4+ T cells and Foxp3 expression among CD45.1+CD4+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Splenocytes (2.5×106 cells/ml) obtained from the recipients were stimulated with 20 µg/ml MOG35–55 for 3 days, and the amounts of IL-17 and IFNγ in the supernatant were measured by ELISA.

Statistics

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). Statistics were calculated with the two-tailed Student’s t test or a Mann-Whitney U-test. p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

IL-17 and Th17 cells are increased in non-obese atherogenic LDb mice

Proatherogenic conditions within LDb mice enhance EAE in an IL17-dependent manner

oxLDL induces DC-mediated Th17 polarization in a TLR4, CD36, and MyD88 dependent way

Anti-oxLDL diminishes Th17 cell differentiation of autoreactive T cells in LDb mice

ACKOWLEGMENTS

We thank Drs. C. Dong, R. Wetsel, G. Martinez for critical comments and suggestions on the manuscript, and Dr. A. Hazen for helping cell sorting. The work is supported by research grants from the American Heart Association 10SDG3860046 (YC), the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences funded by National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Award UL1 TR000371 (YC), and US National Health Institute HL084597 (BBT). The Flow Cytometry Core Facility is supported in part by the shared instrumentation grant (RP 110776) from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Chawla A, Barak Y, Nagy L, Liao D, Tontonoz P, Evans RM. PPAR-gamma dependent and independent effects on macrophage-gene expression in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Nat Med. 2001;7:48–52. doi: 10.1038/83336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y, Chang SH, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Nurieva R, Kang HS, Ma L, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Tian Q, Dong C. Critical regulation of early Th17 cell differentiation by interleukin-1 signaling. Immunity. 2009;30:576–587. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G, Qin X, Wu L, Zhang Y, Sheng X, Yu Q, Sheng H, Xi B, Zhang JZ, Zang YQ. Liver X receptor (LXR) mediates negative regulation of mouse and human Th17 differentiation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:658–670. doi: 10.1172/JCI42974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzaki K, Matsui Y, Ikesue M, Ohta D, Ito K, Kanayama M, Kurotaki D, Morimoto J, Iwakura Y, Yagita H, et al. Interleukin-17A deficiency accelerates unstable atherosclerotic plaque formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:273–280. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.229997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nunez G, Schnurr M, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta R, Singh U, Li TB, Fornage M, Teng BB. Hepatic gene expression profiling reveals perturbed calcium signaling in a mouse model lacking both LDL receptor and Apobec1 genes. Atherosclerosis. 2003;169:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid RE, Rao DA, Zhou J, Lo SF, Ranjbaran H, Gallo A, Sokol SI, Pfau S, Pober JS, Tellides G. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma are produced concomitantly by human coronary artery-infiltrating T cells and act synergistically on vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2009;119:1424–1432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbel C, Chen L, Bea F, Wangler S, Celik S, Lasitschka F, Wang Y, Bockler D, Katus HA, Dengler TJ. Inhibition of IL-17A attenuates atherosclerotic lesion development in apoEdeficient mice. J Immunol. 2009;183:8167–8175. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese MC, Van den Bosch F, Roberson SA, Bojin S, Biagini IM, Ryan P, Sloan-Lancaster J. LY2439821, a humanized anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A phase I randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-ofconcept study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:929–939. doi: 10.1002/art.27334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson N, Marks J, Lunt M, Symmons D. Cardiovascular admissions and mortality in an inception cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with onset in the 1980s and 1990s. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1595–1601. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.034777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal T, Mitra S, Khaidakov M, Wang X, Singla S, Ding Z, Liu S, Mehta JL. Current Concepts of the Role of Oxidized LDL Receptors in Atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11883-012-0228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundtman C, Wick G. The autoimmune concept of atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2011;22:327–334. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32834aa0c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Pablo AM, Jiang X, Wang N, Tall AR, Schindler C. IFN-gamma potentiates atherosclerosis in ApoE knock-out mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2752–2761. doi: 10.1172/JCI119465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson GK, Hermansson A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:204–212. doi: 10.1038/ni.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horkko S, Bird DA, Miller E, Itabe H, Leitinger N, Subbanagounder G, Berliner JA, Friedman P, Dennis EA, Curtiss LK, et al. Monoclonal autoantibodies specific for oxidized phospholipids or oxidized phospholipid-protein adducts inhibit macrophage uptake of oxidized lowdensity lipoproteins. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1999;103:117–128. doi: 10.1172/JCI4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueber W, Patel DD, Dryja T, Wright AM, Koroleva I, Bruin G, Antoni C, Draelos Z, Gold MH, Durez P, et al. Effects of AIN457, a fully human antibody to interleukin-17A, on psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitis. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:52ra72. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janabi M, Yamashita S, Hirano K, Sakai N, Hiraoka H, Matsumoto K, Zhang Z, Nozaki S, Matsuzawa Y. Oxidized LDL-induced NF-kappa B activation and subsequent expression of proinflammatory genes are defective in monocyte-derived macrophages from CD36-deficient patients. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2000;20:1953–1960. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.8.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Febbraio M, Robinet P, Dugar B, Greene D, Cerny A, Latz E, Gilmour R, Staschke K, Chisolm G, et al. The critical role of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4-mediated NF-kappaB activation in modified low-density lipoprotein-induced inflammatory gene expression and atherosclerosis. Journal of immunology. 2011;186:2871–2880. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball AB, Robinson D, Jr, Wu Y, Guzzo C, Yeilding N, Paramore C, Fraeman K, Bala M. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001–2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27–37. doi: 10.1159/000121333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen RR, Weber C. Therapeutic targeting of chemokine interactions in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:141–153. doi: 10.1038/nrd3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu N, Hori S. Full restoration of peripheral Foxp3+ regulatory T cell pool by radioresistant host cells in scurfy bone marrow chimeras. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:8959–8964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702004104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger GG, Duvic M. Epidemiology of psoriasis: clinical issues. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:14S–18S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12386079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurat E, Poirier B, Tupin E, Caligiuri G, Hansson GK, Bariety J, Nicoletti A. In vivo downregulation of T helper cell 1 immune responses reduces atherogenesis in apolipoprotein Eknockout mice. Circulation. 2001;104:197–202. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, Cameron G, Li L, Edson-Heredia E, Braun D, Banerjee S. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1190–1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Wang Y, Chen K, Zhou Q, Wei W. The role of oxidized low-density lipoprotein in breaking peripheral Th17/Treg balance in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2010;394:836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Lichtman AH, Hansson GK. Immune effector mechanisms implicated in atherosclerosis: from mice to humans. Immunity. 2013;38:1092–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, Conte CG, Medsger TA, Jr, Jansen-McWilliams L, D'Agostino RB, Kuller LH. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:408–415. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Orozco N, Chung Y, Chang SH, Wang YH, Dong C. Th17 cells promote pancreatic inflammation but only induce diabetes efficiently in lymphopenic hosts after conversion into Th1 cells. European journal of immunology. 2009;39:216–224. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, Laurence A, Joyce-Shaikh B, Blumenschein WM, McClanahan TK, O'Shea JJ, Cua DJ. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:314–324. doi: 10.1038/ni.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KJ, Rosen ED, Fitzgerald ML, Randow F, Andersson LP, Altshuler D, Milstone DS, Mortensen RM, Spiegelman BM, Freeman MW. The role of PPAR-gamma in macrophage differentiation and cholesterol uptake. Nat Med. 2001;7:41–47. doi: 10.1038/83328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JG, Chen H, Evans RM. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARgamma. Cell. 1998;93:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurieva R, Yang XO, Chung Y, Dong C. Cutting edge: in vitro generated Th17 cells maintain their cytokine expression program in normal but not lymphopenic hosts. Journal of immunology. 2009;182:2565–2568. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinski W, Horkko S, Miller E, Steinbrecher UP, Powell HC, Curtiss LK, Witztum JL. Cloning of monoclonal autoantibodies to epitopes of oxidized lipoproteins from apolipoprotein E deficient mice. Demonstration of epitopes of oxidized low density lipoprotein in human plasma. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1996;98:800–814. doi: 10.1172/JCI118853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potteaux S, Combadiere C, Esposito B, Lecureuil C, Ait-Oufella H, Merval R, Ardouin P, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Role of bone marrow-derived CC-chemokine receptor 5 in the development of atherosclerosis of low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1858–1863. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000231527.22762.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman MJ, Shanker BA, Davis A, Lockshin MD, Sammaritano L, Simantov R, Crow MK, Schwartz JE, Paget SA, Devereux RB, Salmon JE. Prevalence and correlates of accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2399–2406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saederup N, Chan L, Lira SA, Charo IF. Fractalkine deficiency markedly reduces macrophage accumulation and atherosclerotic lesion formation in CCR2−/− mice: evidence for independent chemokine functions in atherogenesis. Circulation. 2008;117:1642–1648. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I, Yin H, Flier JS. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:3015–3025. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh U, Zhong S, Xiong M, Li TB, Sniderman A, Teng BB. Increased plasma nonesterified fatty acids and platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase are associated with susceptibility to atherosclerosis in mice. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;106:421–432. doi: 10.1042/CS20030375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spann NJ, Garmire LX, McDonald JG, Myers DS, Milne SB, Shibata N, Reichart D, Fox JN, Shaked I, Heudobler D, et al. Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell. 2012;151:138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatelopoulos KS, Kitas GD, Papamichael CM, Chryssohoou E, Kyrkou K, Georgiopoulos G, Protogerou A, Panoulas VF, Sandoo A, Tentolouris N, et al. Atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis versus diabetes: a comparative study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1702–1708. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.190108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CR, Stuart LM, Wilkinson K, van Gils JM, Deng J, Halle A, Rayner KJ, Boyer L, Zhong R, Frazier WA, et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:155–161. doi: 10.1038/ni.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacke F, Alvarez D, Kaplan TJ, Jakubzick C, Spanbroek R, Llodra J, Garin A, Liu J, Mack M, van Rooijen N, et al. Monocyte subsets differentially employ CCR2, CCR5, and CX3CR1 to accumulate within atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:185–194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellides G, Tereb DA, Kirkiles-Smith NC, Kim RW, Wilson JH, Schechner JS, Lorber MI, Pober JS. Interferon-gamma elicits arteriosclerosis in the absence of leukocytes. Nature. 2000;403:207–211. doi: 10.1038/35003221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, Jha S, Zhang L, Huang MT, Brickey WJ, Ting JP. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nature immunology. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer S, Paltser G, Chan Y, Tsui H, Engleman E, Winer D, Dosch HM. Obesity predisposes to Th17 bias. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2629–2635. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T, Yang XO, Chung Y, Fukunaga A, Nurieva R, Pappu B, Martin-Orozco N, Kang HS, Ma L, Panopoulos AD, et al. CCR6 regulates the migration of inflammatory and regulatory T cells. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:8391–8401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.