Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To determine the proportion of untreated women who reported receiving treatment after incident fracture and to identify factors that predict treatment across an international spectrum of individuals.

DESIGN

Prospective observational study. Self-administered questionnaires were mailed at baseline and 1 year.

SETTING

Multinational cohort of noninstitutionalized women recruited from 723 primary physician practices in 10 countries.

PARTICIPANTS

Sixty thousand three hundred ninety-three postmenopausal women aged 55 and older were recruited with a 2:1 oversampling of women aged 65 and older.

MEASUREMENTS

Data collected included participant demographics, medical history, fracture occurrence, medications, and risk factors for fracture. Anti-osteoporosis medications (AOMs) included estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, and strontium.

RESULTS

After the first year of follow-up, 1,075 women reported an incident fracture. Of these, 17% had started AOM, including 15% of those with a single fracture and 35% with multiple fractures. Predictors of treatment included baseline calcium use (P = .01), baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis (P < .001), and fracture type (P < .001). In multivariable analysis, women taking calcium supplements at baseline (odds ratio (OR) = 1.67) and with a baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis (OR = 2.55) were more likely to be taking AOM. Hip fracture (OR = 2.61), spine fracture (OR = 6.61), and multiple fractures (OR = 3.79) were associated with AOM treatment. Age, global region, and use of high-risk medications were not associated with treatment.

CONCLUSION

More than 80% of older women with new fractures were not treated, despite the availability of AOM. Important factors associated with treatment in this international cohort included diagnosis of osteoporosis before the incident fracture, spine fracture, and to a lesser degree, hip fracture.

Keywords: osteoporosis, fracture, osteoporosis treatment

Osteoporosis is a common and costly problem. Approximately half of women aged 50 and older will sustain a fragility fracture, and the greatest morbidity occurs in those aged 65 and older.1 Mortality can reach 20% for a hip or vertebral fracture within the first year and continues to rise for up to 10 years.2–4 Medications are available to reduce the risk of fractures.5–8 Oral, intravenous, inhaled, and subcutaneous medications reduce the risk of vertebral fractures 50% or more,5,6 and some medications also substantially reduce the risk of nonvertebral and hip fractures.5,6

Despite the availability of a variety of medications, few recent data are available on factors that determine whether individuals with new fragility fractures are treated. Previous studies suggest that fewer than 5% of individuals admitted to hospital with hip fracture leave the hospital with a diagnosis of osteoporosis and that fewer than 1% are treated.9 Similar studies have documented poor treatment rates in individuals with vertebral fractures. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggest that fewer than 14% of women with a diagnosis of osteoporosis are treated with an antiresorptive medication and that the number of risk factors for fracture does not alter rates of medication use.10 Previous studies have focused on a single community or country, often under the umbrella of a national or insurance-based health care environment. Such local or national health environments may limit or support osteoporosis medication use. Global data are needed to better identify barriers to treatment across a range of practices, regions, and healthcare systems. Such data with differing healthcare costs, guidelines, reimbursements, and access to care may clarify obstacles to treatment after a fracture.

The Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW) is a multinational, observational, prospective study designed to provide information on patterns of management of fracture and fracture risk in women aged 55 and older, with an oversampling of elderly women over a 5-year period on an international basis. The goals of the present study were to determine the proportion of women not receiving therapy at baseline who suffered an incident fracture and were receiving treatment at 1-year follow-up and to understand the factors that predict treatment. To examine this, GLOW participants who had sustained a fragility fracture during their first year of follow-up were surveyed.

METHODS

GLOW is a prospective cohort study involving 723 physician practices at 17 sites in 10 countries. The study methods have been described previously, including a flow diagram that describes the recruitment and enrollment.11 In brief, study sites were selected on the basis of geographic distribution and the presence of lead investigators with expertise in osteoporosis and access to a clinical research team capable of managing a large cohort of subjects. These lead investigators identified primary care practices in their region that were members of local research or administrative networks and were able to supply names and addresses of their patients electronically. The composition of groups varied according to region and included health system–owned practices, managed practices, independent practice associations, and health maintenance organizations. Each site obtained local ethics committee approval to participate in the study. The practices provided the names of women aged 55 and older who had seen their physician in the past 24 months. Approximately 3,000 women were sought at each site, with a 2:1 over- sampling of women aged 65 and older. Self-administered questionnaires (baseline surveys) were mailed to 140,416 individuals between October 2006 and February 2008. Nonresponders were followed up with a series of postcard reminders, a second questionnaire, and telephone interviews. After appropriate exclusion, 60,393 women agreed to participate in the study. Follow-up questionnaires were mailed 1 year later to women who had participated in the baseline survey.

Measures Analyzed

Information was gathered during the baseline survey on prior fracture since the age of 45 and during the 1-year follow-up survey on incident fracture. Both surveys included reports of fracture location, including spine, hip, wrist, and other nonvertebral sites (clavicle, upper arm, rib, pelvis, ankle, upper leg, lower leg, foot, hand, shoulder, knee, elbow, and sternum) and occurrence of single or multiple fractures. Baseline medications consisted of any listed bone medication taken at the time of the baseline survey. Anti-osteoporosis medications (AOMs) included estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators, bisphosphonates (oral and intravenous), calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, and strontium. To qualify for analysis, women could not have been taking an AOM at baseline but could have reported AOM use before the baseline survey, which is defined as prior use of AOM. One-year bone medication is defined as current use of a bone medication at the 1-year survey date. Information on age, height, and weight was collected to allow calculation of body mass index. Questions were asked about the use of calcium or vitamin D supplements, alcohol consumption, smoking status, baseline and 1-year diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis, whether the participant had had a bone density test at baseline or at 12 months, whether they had a history of a parental fracture, and whether they were somewhat or very concerned about osteoporosis. The women were also asked about visits to their doctor in the past year and whether they had a fall during the past 12 months. The EuroQol EQ-5D instrument—a five-question, three-response, option scale12,13—was used to assess health. The Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)13–16 subscales were used to determine physical function scores and vitality scores.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are shown as unadjusted proportions; chi-square or Fisher exact tests were used to test for differences. Tests of significance for fracture location use the “no fracture” group as a reference; the AOM rate for women with a single fracture was compared with that for women with more than one type of 1-year fracture. All comparisons used the chi-square test. A multivariable logistic regression model predicting AOM use in treatment-naïve women with an incident fracture was fit using backward selection based on the variables that were significant (P < .05) in the univariate analysis. The final model retained all factors for which P < .05, as well as controlling for region as a study design factor. Reference categories in this model were as follows; current calcium use at baseline was compared with past use or never having taken calcium at baseline. Baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis and baseline diagnosis of osteopenia were compared with reporting neither diagnosis at baseline. Hip, spine, and multiple fractures were compared with a single-incident, nonhip, nonvertebral fracture. All regions were compared with the United States. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study Population

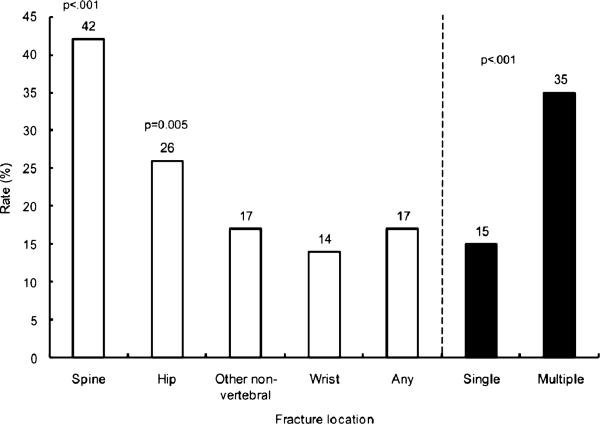

Of the 60,393 women who completed a baseline GLOW survey, 51,491 had 1-year follow-up data (85% response rate); 35,911 of these did not report use of AOM at baseline, 1,115 of those reported an incident fracture, and 40 of those did not provide current treatment data and thus were removed from the analysis, leaving 1,075 for analysis of characteristics associated with treatment. Of women with an incident fracture, 187 (17%) reported using AOM after the first year of follow-up. When AOM use was examined according to the skeletal location of the incident fracture, 14% of women with fractures at the wrist, 26% with fractures of the hip, 17% with other nonvertebral fractures, and 42% with fractures at the spine were using AOM at 1 year (Figure 1). Only 15% of participants with any single fracture and 35% of those with multiple fractures were undergoing AOM treatment at 1 year. Eighty-three percent of those with a new fracture were not taking AOM. Of these 888 women not taking AOM, 14 had stopped medication in the past year because of side effects, 12 stopped at the request of their physicians, and two stopped for both reasons, for a total of 24 (2.7%) who discontinued AOM. Of the 34,668 women not undergoing treatment at baseline, 33,593 did not have an incident fracture, 2,179 (6.5%) of whom reported current use of AOM at year 1 (P < .001, 6.5% use in women with no fracture vs 17% use in women with an incident fracture).

Figure 1.

Rate of anti-osteoporosis medication (estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, and strontium) use at 1-year follow-up in treatment-naive participants at baseline with 1-year incident fractures according to skeletal location (N = 1,075).

Variables Associated with Treatment

Baseline characteristics and current AOM status are shown in Table 1 for women who sustained a fracture during their first year of follow-up. Women who had a previous fracture since age 45 were more likely to be taking AOM (P = .003). Women taking AOM were significantly older than those not taking AOM (P < .008). A significantly higher proportion of women who reported problems with mobility and activity were taking AOM than of those who did not have such problems (P = .002 and P = .004, respectively), although there were no differences in the percentage of women reporting problems with pain and discomfort or anxiety and depression between the group reporting AOM use and the group not taking AOM. Women with physical function scores and vitality scores lower than the midpoint (50) were also more likely than those with scores greater than the midpoint to be taking AOM (P = .004 and P = .022, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Current Anti-Osteoporosis Medication (AOM)* Use in Women with Incident Fracture (N = 1,075)

| Characteristic | N | n (%) |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Current AOM (n = 888) | Current AOM (n = 187) | |||

| Prior fracture | 392 | 306 (35) | 86 (47) | .003 |

| Age | ||||

| 55–64 | 376 | 327 (37) | 49 (26) | .008 |

| 65–74 | 345 | 284 (32) | 61 (33) | |

| ≥ 75 | 354 | 277 (31) | 77 (41) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||||

| <18.5 (underweight) | 22 | 19 (2.3) | 3 (1.7) | .33 |

| 18.5–24.9 (normal) | 391 | 315 (38) | 76 (42) | |

| 25.0–29.9 (overweight) | 351 | 285 (34) | 66 (37) | |

| ≥ 30 (obese) | 247 | 212 (26) | 35 (19) | |

| EQ-5D “No problems” | ||||

| Mobility | 639 | 549 (65) | 90 (52) | .002 |

| Self-care | 967 | 807 (91) | 160 (87) | .07 |

| Activity | 695 | 592 (67) | 103 (56) | .004 |

| Pain or discomfort | 276 | 232 (27) | 44 (24) | .49 |

| Anxiety or depression | 529 | 442 (51) | 87 (47) | .38 |

| Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Survey score <50 | ||||

| Physical function | 292 | 226 (26) | 66 (36) | .004 |

| Vitality | 291 | 229 (26) | 62 (35) | .02 |

| Prior use of AOM | 502 | 403 (45) | 99 (53) | .06 |

| Calcium use | 398 | 314 (36) | 84 (46) | .01 |

| Vitamin D use | 403 | 326 (37) | 77 (42) | .24 |

| Current smoker | 97 | 82 (9.3) | 15 (8.1) | .60 |

| Alcohol (≥ 21 drinks/week) | 11 | 10 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | .70† |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Osteoporosis | 196 | 140 (17) | 56 (33) | <.001 |

| Osteopenia | 169 | 135 (16) | 34 (20) | |

| Neither | 643 | 563 (67) | 80 (47) | |

| Bone density test done | 666 | 543 (66) | 123 (72) | .11 |

| Number of falls | ||||

| 0 | 526 | 437 (50) | 89 (49) | .95 |

| 1 | 268 | 222 (25) | 46 (25) | |

| ≥2 | 270 | 222 (25) | 48 (26) | |

| Parental fracture | 186 | 150 (19) | 36 (23) | .29 |

| Somewhat or very concerned about osteoporosis | 852 | 691 (79) | 161 (88) | .004 |

| Location | ||||

| Canada or Australia | 123 | 108 (12) | 15 (8.0) | .16 |

| Europe | 454 | 378 (43) | 76 (41) | |

| United States | 498 | 402 (45) | 96 (51) | |

Estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, and strontium.

Fisher exact test used because of small cell values.

A higher percentage of women who reported taking calcium supplements at baseline were also more likely to be taking AOM (P = .010) than those not taking calcium. Women reporting a baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis were also significantly more likely to be taking AOM than those who did not report this diagnosis (P < .001), and those who were somewhat or very concerned about osteoporosis were more likely to be taking AOM (P = .004) than those who were not concerned about osteoporosis.

Having a bone mineral density test at baseline, history of parental fracture, and location of the study site were not associated with a significant difference in AOM use. There were also no differences between the treated and untreated groups in terms of body mass index.

Women who had used AOM in the past (prior use of AOM) but were not undergiong treatment at baseline had greater use of AOMs after the incident fracture. A diagnosis of osteoporosis or a bone density test in the year of follow-up was associated with AOM use (P < .001 for both). A history of falls during the follow-up year had no effect on AOM use.

At 1-year follow-up, women with a spine or hip fracture were more likely to be taking AOM than those who did not have a fracture at these sites (P < .001 and P = .005, respectively), but there was no difference in AOM use in those who had a wrist or other nonvertebral fracture (Table 2). Women who had multiple fractures were more likely to be taking AOM than those with single fractures (P < .001). Women taking calcium were more likely to be taking AOM, but use of vitamin D, smoking, and alcohol misuse had no effect on AOM.

Table 2.

Anti-Osteoporosis Medication (AOM)* Use in Women with Incident Fracture According to Fracture Location (N = 1,075)

| Fracture Location | n | n (%) |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Current AOM (n = 888) | Current AOM (n = 187) | |||

| Spine | 55 | 32 (4.0) | 23 (16) | <.001 |

| Hip | 76 | 56 (6.9) | 20 (14) | .005 |

| Wrist | 230 | 198 (24) | 32 (22) | .56 |

| Other nonvertebral† | 749 | 622 (70) | 127 (68) | .56 |

| Single | 953 | 809 (91) | 144 (77) | <.001 |

| Multiple | 122 | 79 (8.9) | 43 (23) | |

Estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, and strontium.

Clavicle, upper arm, rib, pelvis, ankle, upper leg, lower leg, foot, hand, shoulder, knee, elbow, sternum, or multiple fractures of unknown type.

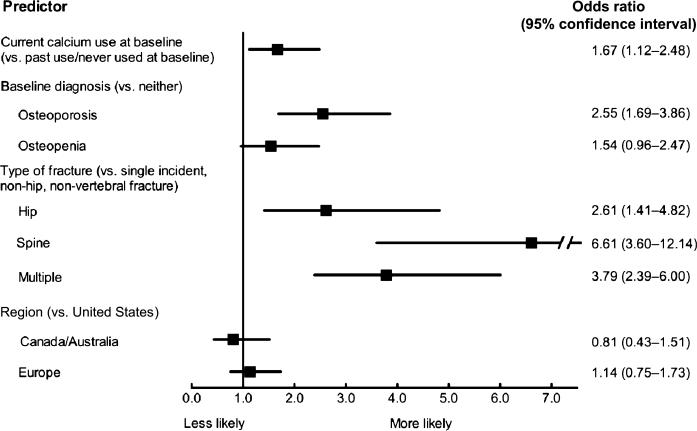

In multivariable analysis, significant predictors of current treatment included baseline calcium use, report of baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis, and fracture type (Figure 2). Older age and previous fractures were not predictors of treatment. Women taking calcium supplements at baseline were 1.67 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.12–2.48, P = .01) times as likely to be taking AOM after fracture as those who were not. Women with a baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis were 2.55 (95% CI 1.69–3.86, P < .001) times as likely to be taking AOM as those diagnosed with neither osteoporosis nor osteopenia (Figure 2). Although significant on the univariate level, age and prior fracture at baseline were not significant on the multivariable level and therefore were not included in the model results in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Predictors of current anti-osteoporosis medication (estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, and strontium) use at 1 year in treatment-naive women with incident fracture (N = 1,075; c statistic = 0.73).

Type of fracture was a significant predictor of AOM use; women with a hip fracture were 2.61 (95% CI 1.41– 4.82, P = .002) times as likely, those with a spine fracture 6.61 (95% CI 3.60–12.14, P < .001) times as likely, and those with multiple fractures 3.79 (95% CI 2.39–6.00, P < .001) times as likely to be treated with AOM as women with a single-incident, nonhip, nonvertebral fracture. Geographic region was not associated with AOM use (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

The data from this multinational study involving postmenopausal women from 10 countries demonstrated that only 17% of untreated women report using AOMs after a fracture. Of the small percentage of women with an incident fracture who were treated, women with spine fractures were far more likely to be treated than women with other types of fractures. The group that was next most likely to be treated was women with more than one incident fracture, followed by women with hip fractures. Other factors associated with the 17% of women undergoing treatment included baseline calcium use and baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis. A baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis was associated with 2.5 times the likelihood of treatment as women with incident fractures who did not report an osteoporosis diagnosis at baseline. Participant concern about osteoporosis, age, mobility, activity, and physical function was not independently associated with greater likelihood of treatment after controlling for other participant factors.

Previous studies have tried to examine why individuals newly diagnosed with a fracture are not treated.17 One study examined 170 elderly adults admitted to an orthopedic unit with a hip fracture to investigate whether they were prescribed calcium, vitamin D, or bisphosphonate therapy. Only 3% of participants were given a diagnosis of osteoporosis, 3% had a bone density assessment, 4% received calcium, 3% received vitamin D, and only 1% received a bisphosphonate.9 Furthermore, there were no significant changes if a medical consultant managed these patients in the hospital. However, this was a retrospective chart review, and it is not known whether these measures changed after discharge. A cross-sectional analysis examined NHANES data from 1999/2000 and 2001/2002 to identify risk factors for fractures and use of antiresorptive prescription medication in women aged 65 and older. It found that only 17% of older women who sustained a prior fracture and 13% of women in the highest risk group were receiving drugs to prevent bone loss.10 A longitudinal study recently showed that a diagnosis of osteoporosis was associated with treatment in high-risk women who met bone density criteria for treatment.18 A prospective cohort study of 2,075 women from Quebec contacted 6 to 8 months after their fragility fracture reported that only 15.4% had started pharmacological therapy.19 The women were more likely to start treatment if they had a bone density measurement and if the test resulted in a diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis. They also found that women aged 65 and older were more likely to start medication than a younger group. The current study concurs with the finding concerning the low incidence of treatment and confirms this in several study sites in Europe, the United States, Australia, and in one other site in Canada, although the results of the current study differ in that having a bone density text or a diagnosis of osteopenia was not associated with treatment in the incident fracture group. Only a baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis was associated with greater likelihood of treatment. Smaller studies, from a single medical center, community, practice, or database, suggest that the rate of treatment has been historically low.17 When data from the present study are compared with those in the literature, there has been little improvement in the past several years in the use of treatment after an incident fracture. Furthermore, because this study includes practices from North America, Europe, and Australia, with different healthcare systems, this provides the first prospective data that, despite global differences in health care and access to medical care and medications, treatment of fractures continues to be low on an international level.

In addition to an individual's perception of the diagnosis of osteoporosis and need for therapy, the physician's decision regarding treatment is crucial. Because this study was a self-report survey, information from physician and healthcare providers was not available regarding their decision to treat. Other studies that have focused on various groups of healthcare professionals have reported that the obstacles to treatment include the cost of therapy, cost and time of response to make a diagnosis, concerns about medication side effects, and lack of clarity about whose responsibility it is to initiate treatment (e.g., orthopedic surgeons, specialists, family physicians).17 In the current survey, few participants discontinued medication because of side effects or at the request of their physicians. Guidelines for many national groups, including the National Osteoporosis Foundation, International Osteoporosis Foundation, and Osteoporosis Canada, promote the treatment of people with fragility fractures.7,20,21 In addition, there are country-specific guidelines in Europe. Many of these guidelines describe the significant reduction in fractures with antiresorptive or anabolic therapy,7,20,21 but ultimately, it is the responsibility of the healthcare professional to concur with the findings and follow these clinical guidelines.

The findings of the current study highlight that the diagnosis of osteoporosis is important in an individual receiving pharmacological therapy after a fracture. The skeletal location of the fracture—spine or hip—is also strongly associated with initiation of treatment. This is in agreement with the finding of a previous study22 that found a higher likelihood of treatment in women with spine fractures than with hip fractures. One hypothesis for this difference is that the primary care physician may be more frequently involved in the diagnosis of a spine fracture than a hip fracture, which is more likely to be diagnosed by orthopedists, who are reluctant to treat osteoporosis medically.23 In addition, although a previous fracture was a predictor of treatment in the univariate analysis, neither age nor previous fracture–two of the strongest predictors of fracture risk–was significant in the multivariable analysis.

During data collection for this study, the risk assessment tool developed by the World Health Organization (FRAX) became available.24 This tool uses history of fracture in addition to other risk factors to predict a patient's individual 10-year risk of a major fracture or hip fracture. Recommendations for treatment based on the FRAX score have been implemented in some of the countries involved in this study. Implementation of FRAX may increase treatment in women who have experienced a fracture, depending on the timing and the treatment thresholds that health insurance companies and national health plans in each of the countries studied advocate. If practice guidance reflecting an individual's risk for fracture was being followed, it would be expected that people with major risk factors for fracture would be more likely to receive treatment to prevent fractures.

This study has several limitations. Because GLOW is based on a mail and telephone survey, it relies on self-report of data that were not confirmed using other means. Nevertheless, in practice and research studies, self-report of many factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol, medication use) cannot be verified. A diagnosis of osteoporosis (or need for treatment) may be difficult to verify because it can be established according to either a clinical fracture, a silent nonvertebral fracture, or bone mineral density, along with self reported clinical risk factor assessment. Participants’ acceptance or interpretation of their diagnosis in their self-report was ascertained because it would be relevant to acceptance of therapy. Additionally, self-report of prescription anti-osteoporosis medication compares well with pharmacy data as a method of ascertaining medication use.25 Self-report of fractures has been demonstrated to be accurate for hip, distal forearm, and humerus but may be less accurate for other types of fractures,26,27 although error in the self-report of any risk factor, diagnosis, or fracture would tend to reduce any relationship between that characteristic and likelihood of treatment observed in this study. The use of self-report also has the advantage of allowing data from multiple countries to be compared using the same method of data collection. This means that differences between countries are unlikely to be due to differences in the method of reporting AOM use. Because of sample size, there was not sufficient power to detect a clinically meaningful difference in treatment rates between all study regions, although with less than 20% of the population treated in each region, it is doubtful that any regional differences would be clinically significant. Finally, fractures were not excluded based on how the fracture occurred. Although information was collected about activity during fracture, and it is known that 20 (1.9%) fractures occurred after a motor vehicle accident, it is possible that some of the fractures may have been pathological in nature, but some clinicians may elect not to treat these fractures.

In summary, the largest cohort study of a multinational group of postmenopausal women found that more than 80% of women with new fractures were not treated, despite the availability of medications for osteoporosis. Of the small percentage of women with incident fractures who were treated, the diagnosis of osteoporosis appears to be important for initiating therapy, as well as fracture in the spine and, to a lesser degree, the hip. Medication use may depend on whether a healthcare system provides medication and services or whether access to medications is more limited. It will be important in future studies to investigate the effect of fracture risk assessment tools for physicians, such as FRAX, on the treatment of those at highest risk of future fracture. The effect of patient education and private and government health insurance policies on better targeting of treatment should also be examined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the physicians and project coordinators participating in GLOW. Sophie Rushton-Smith, PhD, provided editorial support for this article, comprising language editing, content checking, formatting, and referencing.

Susan L Greenspan: Consultant/advisory board: Amgen, Lilly, Merck. Research grants: The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Proctor & Gamble), Lilly. Silvano Adami: Speakers’ bureau: Merck Sharp and Dohme, Lilly, Roche, Procter & Gamble, Novartis. Honoraria: Merck Sharp and Dohme, Roche, Procter & Gamble. Consultant/Advisory Board: Merck Sharp and Dohme, Amgen. Stephen Gehlbach: The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcot). Frederick A Anderson: Research grant: sanofi-aventis. GRACE, GLOW, ENDORSE. The Medicines Company: STAT. Scios: Orthopedic Registry. Consultant/Advisory Board: sanofi-aventis, Scios, GlaxoSmithKline, The Medicines Company, Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Steven Boonen: Research grant: Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline. Speakers’ bureau: Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis, Servier. Honoraria: Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis, Servier. Consultant/Advisory Board: Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis, Ser-vier. Frederick H Hooven: The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcot). Andrea LaCroix: The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcot). Robert Lindsay: The Alliance for Better Bone Health (Sanofi-Aventis and Warner Chilcot). J Coen Netelenbos: Paid consultancy work: Roche Diagnostics, Daiichi-Sankyo, Proctor & Gamble, Nycomed. Paid speaking engagements, reimbursement and travel and accommodation: Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, Daiichi-Sankyo, Procter & Gamble. Research grants: Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen. Johannes Pfeilschifter: Research grant: AMGEN, Kyphon, Novartis, Roche. Other research support. Equipment: GE LUNAR. Speakers’ bureau: AMGEN, sanofi-aventis, Glaxo Smith Kline, Roche, Lilly Deutschland, Orion Pharma, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Merckle, Nycomed, Procter & Gamble. Advisory Board membership: Novartis, Roche, Procter & Gamble, TEVA. Stuart Silverman: Research grants: Wyeth, Lilly, Novartis, Alliance. Speakers’ bureau: Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble. Honoraria: Procter & Gamble. Consultant/Advisory Board: Lilly, Argen, Wyeth, Merck, Roche, Novartis. Ethel S Siris: Consultant: Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Alliance for Better Bone Health. Speakers’ Bureau: Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen, Eli Lilly. Nelson B Watts: Stock options/holdings, royalties, company owner, patent owner, official role: none. Honoraria for lectures in past year: Amgen, Novartis, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis. Consulting in past year: Amgen, Baxter, Inte Krin, Johnson & Johnson, Mann Kind, Novo Nordisk, NPS, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Warner Chilcott. Research support (through University): Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, NPS.

Sponsor's Role: The sponsors had no involvement in study design, methods, or participant recruitment; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors had access to the study data and participated in analysis or interpretation of the data (or both) and preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott) provided financial support for the GLOW study to The Center for Outcomes Research, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schneider DL. Management of osteoporosis in geriatric populations. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6:100–107. doi: 10.1007/s11914-008-0018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper C. The crippling consequences of fractures and their impact on quality of life. Am J Med. 1997;103:12S–17S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)90022-x. discussion 17S-19S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Population-based study of survival after osteoporotic fractures. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1001–1005. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, et al. Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA. 2009;301:513–521. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davison KS, Kendler DL, Ammann P, et al. Assessing fracture risk and effects of osteoporosis drugs: Bone mineral density and beyond. Am J Med. 2009;122:992–997. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilezikian JP. Efficacy of bisphosphonates in reducing fracture risk in post-menopausal osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2009;122:S14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Foundation; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenspan SL. Osteoporosis. In: Andriole TE, editor. Cecil's Essentials of Medicine. 8th Ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2010. Ch. 76. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamel HK, Hussain MS, Tariq S, et al. Failure to diagnose and treat osteoporosis in elderly patients hospitalized with hip fracture. Am J Med. 2000;109:326–328. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gehlbach SH, Avrunin JS, Puleo E, et al. Fracture risk and antiresorptive medication use in older women in the USA. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:805–810. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0310-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooven FH, Adachi JD, Adami S, et al. The Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW): Rationale and study design. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1107–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0958-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks R. EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brazier JE, Walters SJ, Nicholl JP, et al. Using the SF-36 and EuroQol on an elderly population. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:195–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00434741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picavet HS, Hoeymans N. Health related quality of life in multiple musculoskeletal diseases: SF-36 and EQ-5D in the DMC3 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:723–729. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.010769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: New outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305:160–164. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lips P, van Schoor NM. Quality of life in patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:447–455. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1762-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Jamal SA, et al. Practice patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: A systematic review. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:767–778. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1675-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryder KM, Shorr RI, Tylavsky FA, et al. Correlates of use of antifracture therapy in older women with low bone mineral density. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:636–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bessette L, Ste-Marie LG, Jean S, et al. The care gap in diagnosis and treatment of women with a fragility fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:79–86. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanis JA, Burlet N, Cooper C, et al. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:399–428. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0560-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Towards a Fracture-Free Future. Osteoporosis Canada; Ontario: 2011. Osteoporosis. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrade SE, Majumdar SR, Chan KA, et al. Low frequency of treatment of osteoporosis among postmenopausal women following a fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2052–2057. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simonelli C, Killeen K, Mehle S, et al. Barriers to osteoporosis identification and treatment among primary care physicians and orthopedic surgeons. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:334–338. doi: 10.4065/77.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, et al. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:385–397. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison J, et al. Agreement and validity of pharmacy data versus self-report for use of osteoporosis medications among chronic glucocorticoid users. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:710–718. doi: 10.1002/pds.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ismail AA, O'Neill TW, Cockerill W, et al. Validity of self-report of fractures: Results from a prospective study in men and women across Europe. EPOS Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:248–254. doi: 10.1007/s001980050288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Browner WS, et al. The accuracy of self-report of fractures in elderly women: Evidence from a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:490–499. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]