Abstract

Dopamine and serotonin are produced by distinct groups of neurons in the brain, and gene therapies other than direct injection have not been attempted to correct congenital deficiencies in such neurotransmitters. In this study, we performed gene therapy to treat knock-in mice with dopamine and serotonin deficiencies caused by a mutation in the aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) gene (DdcKI mice). Intracerebral ventricular injection of neonatal mice with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 9 (AAV9) vector expressing the human AADC gene (AAV9-hAADC) resulted in widespread AADC expression in the brain. Without treatment, 4-week-old DdcKI mice exhibited whole-brain homogenate dopamine and serotonin levels of 25% and 15% of normal, respectively. After gene therapy, the levels rose to 100% and 40% of normal, respectively. The gene therapy improved the growth rate and survival of DdcKI mice and normalized their hindlimb clasping and cardiovascular dysfunctions. The behavioral abnormalities of the DdcKI mice were partially corrected, and the treated DdcKI mice were slightly more active than normal mice. No immune reactions resulted from the treatment. Therefore, a congenital neurotransmitter deficiency can be treated safely through inducing widespread expression of the deficient gene in neonatal mice.

Introduction

Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC; EC 4.1.1.28) is a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzyme responsible for the synthesis of two monoamine neurotransmitters (dopamine and serotonin) and trace amines (tyramines) (Wassenberg et al., 2010; Hamosh and McKusick, 2011). Mutations in the AADC gene (DDC in humans and Ddc in mice) result in deficiencies of dopamine and serotonin and their downstream metabolites. AADC deficiency (MIM #608643) is a rare, autosomal recessive congenital metabolism error that was first reported in 1990 by Drs. Hyland and Clayton (Hyland and Clayton, 1990; Hyland et al., 1992). To date, more than 80 cases have been reported worldwide (Korenke et al., 1997; Maller et al., 1997; Abeling et al., 1998; Swoboda et al., 1999, 2003; Brautigam et al., 2000; Fiumara et al., 2002; Pons et al., 2004; Tay et al., 2007; Brun et al., 2010; Montioli et al., 2013). Patients with AADC deficiency present with hypotonia, oculogyric crises, hypokinesia, and developmental delay, and 96% of these deficiencies become clinically evident during infancy or childhood (Manegold et al., 2009; Brun et al., 2010; Hwu et al., 2012). A cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) profile of high l-DOPA and 3-O-methyldopa (3-OMD) levels and low 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and homovanillic acid levels is often diagnostic (Brun et al., 2010).

A human gene therapy approach using adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector serotype 2 (AAV2) has been tested on patients with AADC deficiency through bilateral putamen injection (Hwu et al., 2012). Compared with pharmacological treatments (vitamin B6, dopamine agonists, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, anticholinergics, l-DOPA, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors), gene therapy improves patient motor function and decreases the severity of oculogyric crises (Hwu et al., 2012). Because AAV2 vector dispersion is limited (Cressant et al., 2004), the treatment effect is confined to the putamen. However, in the brain, dopaminergic and serotoninergic neurons also reside in the ventral tegmental area, the dorsal raphe nuclei, and other areas (Zeiss, 2005). To improve gene therapy for AADC deficiency, we have created a mouse model of AADC deficiency by knocking in the splice site mutation (IVS6+4A>T) commonly found in Taiwanese patients with AADC deficiency (Brun et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2013). Mice with AADC deficiency exhibit severe dyskinesias and hindlimb clasping after birth, growth retardation, and cardiovascular dysfunction (Lee et al., 2013). In the current study, we performed gene therapy for these AADC-deficient mice. We employed an AAV serotype 9 (AAV9) vector to achieve widespread expression of the transgene in the mouse brain (Cearley et al., 2008). We demonstrated that the intracerebral ventricular (ICV) injection of the viral vector could improve growth and normalize the motor dysfunction of these mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All of the experimental procedures were approved and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the National Taiwan University College of Medicine and College of Public Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC No. 20110134). The mouse model of AADC deficiency was generated by knocking in an IVS6+4A>T splicing mutation in the Ddc gene (DdcKI), resulting in exon 6 skipping (Lee et al., 2013). Neonatal mice born to heterozygous breeding parents were treated with vector, mock-treated with phosphate-buffered saline, or untreated. Genotyping was performed when the mice reached 2 weeks of age. Data from the homozygous mice (DdcKI) were analyzed.

AAV vectors

The expression cassette consisted of a cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter followed by the first intron of the human growth hormone, the human AADC cDNA (NM_000790), and the simian virus 40 polyadenylation signal sequence, as previously reported (Hwu et al., 2012). The expression cassette was cloned into a plasmid with AAV type 2 inverted terminal repeats and then packaged into the AAV type 9 capsid (AAV9-hAADC). The AAV9-hAADC vector was generated and titered at the University of Florida Powell Gene Therapy Center Vector Core Laboratory (Gainesville, FL) using previously published methods (Zolotukhin et al., 2002). The titer of the viral preparations used in this study was 1.19×1014 viral genomes (vg) per ml.

ICV injection

Neonatal DdcKI mice (P0) were injected with the AAV9-CMV-hAADC vector bilaterally into the lateral ventricles (2×1010 vg in 2 μl each side) within 24 hr of birth using a 10 μl Hamilton syringe (84853, 801RN26S/2”2; Hamilton, Reno, NV) with a 31-gauge needle (31GA 0.5” PT2 RN; Hamilton) as previously described (Kim et al., 2013). In brief, neonatal mice were subjected to cryoanesthesia until their activity slowed. The needle was inserted perpendicularly to the skull surface at two-fifths of the distance along the line between the eye and lambda with a depth of 2 mm. After bilateral injection of the ventricles, the pups were rewarmed slowly by placing them on a warming pad until they were warm and active. The injected pups were then returned to their mothers.

AADC activity and neurotransmitter levels

Whole mouse brains were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for AADC activity and neurotransmitter analyses. To measure the neurotransmitter levels, the tissues were deproteinized using 0.2 M perchloric acid and centrifuged at 14,000×g for 5 min three times. Dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) levels were analyzed with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a previously reported protocol consisting of electrochemical detection after separation on a Thermo Scientific Hypersil™ GOLD HPLC column (part number: 25005-154630; 5 μm particle size) (Patel et al., 2005). The AADC activity in the brain homogenates was assayed based on measurements of enzymatically formed dopamine from an l-DOPA substrate using HPLC as previously described (Verbeek et al., 2007). Levels of 3-O-methyldopa (3-OMD) were measured using dried blood spots (DBS). One 1/8-inch punch from each DBS was eluted with methanol, and the 3-OMD levels were analyzed using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on an API 4000 mass spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer–Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Motor and behavioral tests

Hindlimb clasping was measured by hanging mice by their tails as previously reported (Lee et al., 2013). The mice were assigned a clasping score of 1 for any dystonic movement and 0 for no abnormal movement. The total clasping score was calculated by adding up the scores in 2 sec segments for 24 sec. Rotarod tests were performed using machines with 3-cm-diameter spindles (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy) (Rozas et al., 1997). Adult mice were trained at 0 rpm for 60 sec (repeated three times) and 4 rpm for 60 sec (repeated three times). The mice were subsequently tested at accelerating speeds from 4 to 40 rpm over 300 sec. The latency and the speed of the rod at the time of falling were recorded.

Home-cage activities such as travel distance, awakening, drinking, feeding, grooming, hanging, rearing, resting, twitching, and walking were recorded over a 24 hr period with a 12 hr dark/light cycle and analyzed using Clever Sys HomeCageScan TM3.0 (Clever Sys., Inc., Reston, VA) as previously reported (Lee et al., 2013). An elevated plus maze was arranged to evaluate anxiety-related behavior according to previous reports (Wu et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2013). The test was performed in a Plexiglas plus maze (size: 65 cm×65 cm) equipped with the video-based EthoVision Color-Pro system (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands). The mice were also injected with apomorphine (1.0 mg/kg, i.p.), and their total activity and number of rears were recorded for 10 min using an automated locomotor activity analysis system (PAS-Open Field; San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA).

Blood pressure and electrocardiography

Blood pressure and heart rate were measured by the BP-2000 Series II Blood Pressure Analysis System (Visitech Systems, Inc., Apex, NC) as previously reported (Lee et al., 2013); measurements were repeated 10 times/afternoon on three consecutive afternoons. Electrocardiography (EKG) was recorded under general anesthesia using PowerLab 8/30 to measure the RR interval, PR interval, P duration, QRS duration, QT interval, and QTc interval.

Immunohistochemistry and histopathological analyses

For immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies, the mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were removed, postfixed overnight at 4°C, cryoprotected with 30% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline for 48 hr, mounted in OCT embedding compound, and frozen. Coronal sections (10 or 30 μm in thickness) were cut using a cryostat. IHC was performed by incubation with an AADC antibody (1:800; a gift from Dr. Ichinose), GFAP (1:500; Millipore, MAB3402), Iba1 (1:500; Abcam ab108539), and MHCII (1:100; eBioscience; 14-5321). The sections were washed, incubated for 2 h with a biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and visualized using the Vectastain Elite ABC Kit and Peroxidase Substrate DAB Kit (both from Vector Laboratories). Histopathological evaluations were analyzed by regular hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the coronal sections.

Positron emission tomography

Positron emission tomography (PET) using 6-[18F]fluoro-l-DOPA (FDOPA) was performed as previously reported (Lin et al., 2010; Vuckovic et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2013). The mice were treated with carbidopa (25 mg/kg, i.p.) and entacapone (25 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 min before injection with FDOPA (500 μCi i.p.). Thirty minutes after the FDOPA injections, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and images were obtained using a small-animal PET/CT scanner (eXplore Vista DR; GE Healthcare, Fairfield, CT).

Statistics

The data are presented as the mean±SEM in each figure. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package, version 11.5. The Mann–Whitney rank test was applied for statistical analyses between groups. The log-rank test was used to analyze the survival rate. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Neonatal ICV AAV9-hAADC injections normalized weight gain and survival in DdcKI mice

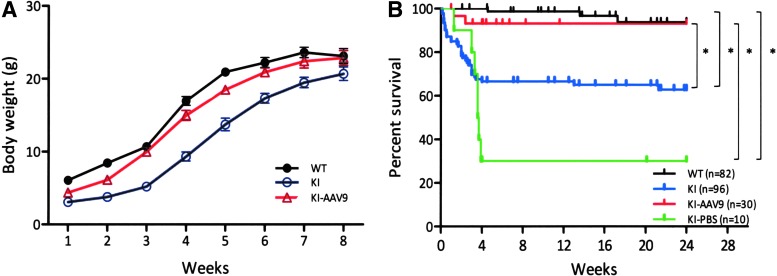

DdcKI mice have been shown to exhibit poor body weight gain and decreased survival before 8 weeks of age (Lee et al., 2013). To test whether the introduction of a vector with a widespread expression pattern could be used as a treatment for AADC deficiency, we packaged the CMV promoter-driven human AADC cDNA into the AAV9 capsid (AAV2/9). We then administered this vector (AAV9- hAADC) via bilateral ICV injections into neonatal mice (P0) and observed these mice up to 24 weeks of age. The results revealed that the treated and untreated DdcKI mice weighed half as much as the wild-type mice at 1 week after birth (Fig. 1A). However, over the next 2 weeks, the AAV9-hAADC-treated mice gained weight faster than the untreated mice (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Video S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum); at 3 weeks of age, the treated mice were significantly larger than the untreated mice (p<0.001). Approximately 10% of the treated DdcKI mice died during this period, whereas 35% of the untreated mice died (Fig. 1B). The untreated mice, if they survived, began to gain weight after 3–4 weeks of age as a result of the spontaneous recovery of brain dopamine levels (Lee et al., 2013). Overall, the ICV injection of AAV9-hAADC significantly increased the survival of DdcKI mice (Fig. 1B; p<0.05). The mock-treated DdcKI mice had a very high mortality rate; therefore, they were not included in the analysis. The vector-injected heterozygous and wild-type mice showed no abnormalities up to 4 weeks of age, when they were euthanized.

FIG. 1.

Improvements in DdcKI mice weight gain and survival after ICV injection of AAV9-hAADC. (A) Growth curves for the wild-type (WT), untreated (KI), and treated (KI-AAV9) DdcKI mice (p<0.001 between KI and KI-AAV9 groups at 3 weeks of age). (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curve for WT, KI, KI-AAV9, and mock-treated (KI-PBS) DdcKI mice (p=0.0051 between KI and KI-AAV9 groups; p<0.0001 between WT and KI-PBS groups; p<0.0001 between KI-AAV9 and KI-PBS groups; p=0.1082 between KI and KI-PBS groups). *p<0.05. AADC, aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase; AAV, adeno-associated virus; ICV, intracerebral ventricular.

Elevated AADC activity and increased neurotransmitter levels

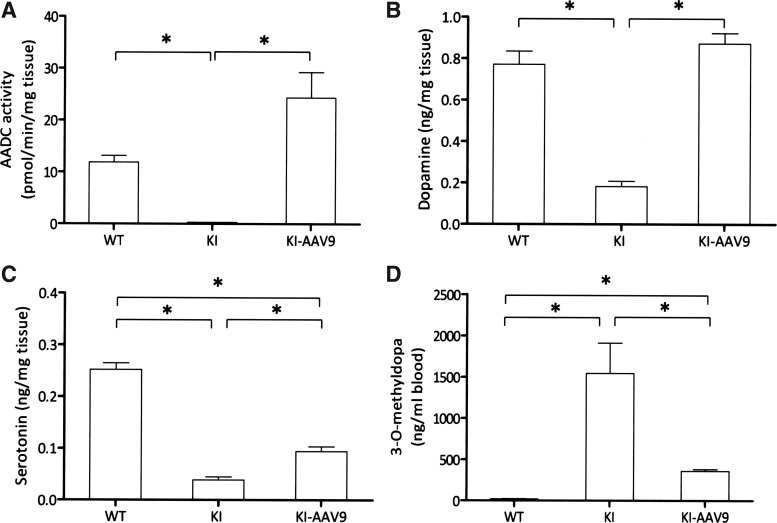

Four weeks after the ICV injection of AAV9-hAADC, the mice were euthanized, and the AADC enzyme activity and neurotransmitter levels were measured in mouse whole-brain homogenates. The whole-brain homogenate AADC activity levels in the treated DdcKI mice were approximately twice as high as in the wild-type mice; however, the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 2A). The dopamine levels in the treated mice were similar to the levels in the wild-type mice and were significantly higher than in the untreated mice (Fig. 2B). The serotonin levels also increased in the treated mice compared with the untreated mice; however, the levels were still lower than those in the wild-type mice (Fig. 2C). The levels of 3-O-methyldopa, the l-DOPA metabolite, were reduced in the DdcKI mice but were still elevated after treatment (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Elevated AADC activity and increased neurotransmitter levels in AAV9-hAADC-injected DdcKI mice whole-brain homogenates. (A) Four-week-old treated (KI-AAV9) DdcKI mice exhibited higher levels of AADC activity than wild-type (WT) mice, although the difference was not significant. By contrast, the AADC activity was undetectable in the untreated (KI) DdcKI mice (p=0.014 between KI and KI-AAV9 groups; p=0.57 between WT and KI-AAV9 groups; n=4). (B) The dopamine levels were low in the KI mice but comparable in the WT and KI-AAV9 mice (p=0.009 between KI and KI-AAV9 groups; p=0.251 between WT and KI-AAV9 groups; n=5). (C) The serotonin levels in the KI-AAV9 mice were higher than those in the KI mice but lower than those in the WT mice (p=0.009 between KI and KI-AAV9 groups; p=0.009 between WT and KI-AAV9 groups; n=5). (D) The dried blood spot 3-O-methyldopa (3-OMD) levels were very high in the KI mice, mildly elevated in the KI-AAV9 mice but undetectable in the WT mice (p=0.009 between WT and KI groups, WT and KI-AAV9 groups, and KI and KI-AAV9 groups). *p<0.05.

AAV9-hAADC ICV injection improved motor function in DdcKI mice

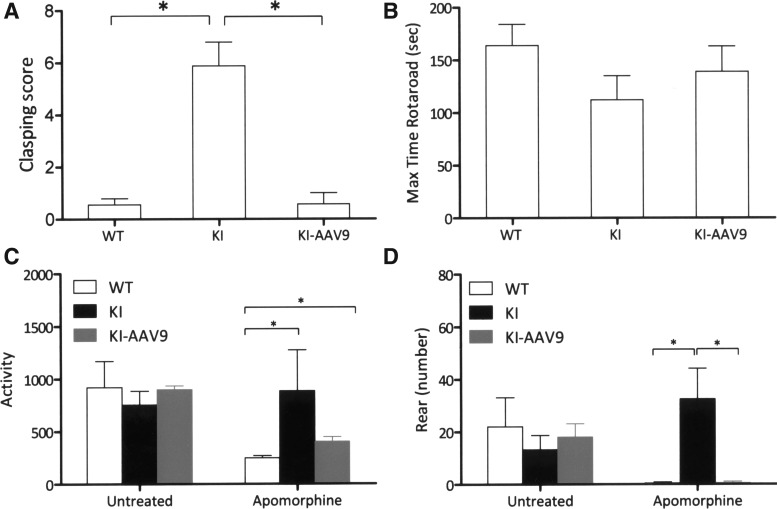

Young DdcKI mice exhibit motor dysfunction because of dopamine deficiencies. We tested the effect of AAV9-hAADC ICV injection using the hindlimb clasping test and rotarod test. The hindlimb clasping test was performed on the mice at 2 weeks of age. The results showed that clasping rarely appeared in the wild-type mice, whereas the DdcKI mice had severe hindlimb clasping. However, ICV injection effectively prevented the occurrence of hindlimb clasping (Fig. 3A). The rotarod test was performed on 8-week-old mice; the difference between the wild-type mice and the DdcKI mice did not reach significance (Fig. 3B). This finding may be because of the spontaneous recovery of brain dopamine levels in the DdcKI mice.

FIG. 3.

AAV9-hAADC ICV injection improved motor function in the DdcKI mice. (A) Hindlimb clasping score in 2-week-old wild-type (WT), untreated (KI), and treated (KI-AAV9) DdcKI mice. The KI mice showed high clasping scores, whereas the WT and KI-AAV9 mice rarely exhibited clasping (p<0.0001 between WT and KI; p=0.758 between WT and KI-AAV9 groups; p<0.0001 between KI and KI-AAV9 groups; WT n=9, KI n=8, KI-AAV9 n=7). (B) Latency to falling off the rod in the rotarod test for 8-week-old WT, KI, and KI-AAV9 mice. No significant differences among the groups were observed in this test. (C) Apomorphine stimulation test. The KI mice had a higher level of activity after apomorphine injection than the wild-type mice (p=0.027). The activity level of the KI-AAV9 mice was slightly lower than that of the KI mice (p=0.368) but was still higher than that of the wild-type mice (p=0.014). (D) The KI mice exhibited more rearing after apomorphine injection than the WT and KI-AAV9 mice (p=0.011 and 0.018, respectively). *p<0.05.

We also tested the sensitivity of cerebral dopamine receptors by stimulating the mice with apomorphine. The DdcKI mice showed increased activity (Fig. 3C) and rearing (Fig. 3D) after apomorphine injection (1 mg/kg), whereas the treated mice showed significant decreases in rearing. However, the activity of the treated mice after apomorphine injection remained higher than the activity of the wild-type mice (p=0.014; Fig. 3C).

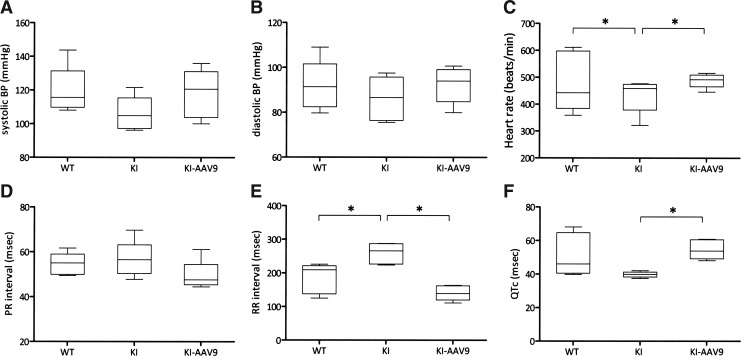

AAV9-hAADC ICV injection corrected cardiovascular dysfunction in DdcKI mice

AADC deficiency also causes autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Therefore, we investigated whether the treatment could correct abnormalities in the blood pressure and EKG readings in the DdcKI mice. The results revealed that the difference in blood pressures between the wild-type and the DdcKI mice was not significant (Fig. 4A and B). The DdcKI mice had slower heart rates than the wild-type mice (Fig. 4C; p=0.016), and AAV9-hAADC ICV injection corrected this defect (p=0.009). Similarly, the DdcKI mice had a longer RR interval on EKG, and the treatment corrected this defect (Fig. 4E; p=0.009). The DdcKI mice had a shorter QTc duration, which was also corrected in the treated mice (Fig. 4F; p=0.009).

FIG. 4.

AAV9-hAADC ICV injection corrected cardiovascular dysfunction in the DdcKI mice. Wild-type (WT), untreated (KI), and treated (KI-AAV9) DdcKI mice at 8–12 weeks of age underwent blood pressure and electrocardiography (EKG) readings. (A) The KI mice had slightly lower systolic blood pressures than the WT and KI-AAV9 mice (p=0.117 and 0.175, respectively, n=5). (B) There were no significant differences in diastolic blood pressure among the three groups. (C) The KI mice had lower heart rates than the WT mice (p=0.016) and the treated mice (p=0.009). The heart rates did not differ between the WT and KI-AAV9 mice (p=0.175). (D) There were no differences in the EKG PR intervals among the three groups. (E) The KI mice had a longer EKG RR interval than WT and KI-AAV9 mice (p=0.016 between WT and KI; p=0.009 between KI and KI-AAV9; p=0.175 between WT and KI-AAV9). (F) The KI-AAV9 mice had a shorter QTc interval than the KI mice (p=0.009). Box-and-whisker plots for the mean values are shown. The error bars are at the 10th and 90th percentiles. *p<0.05.

AAV9-hAADC ICV injection attenuated behavior abnormalities in DdcKI mice

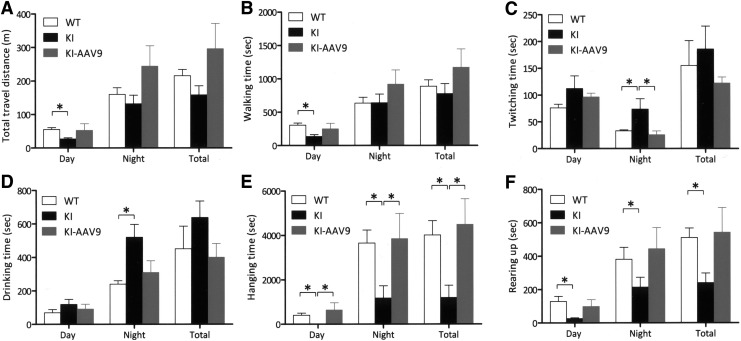

Adult DdcKI mice are known to exhibit behavioral abnormalities, likely because of serotonin deficiency. Therefore, we investigated whether AAV9-hAADV ICV injection would correct these abnormalities. In the home-cage behavior analysis, the DdcKI mice traveled shorter distances and walked for less time than the wild-type mice during the day; however, the treated mice did not demonstrate this abnormality (Fig. 5A and B). At night, the treated mice appeared to be more active than the wild-type mice; however, the differences did not reach statistical significance (p=0.391 for travel distance). The frequency of twitching, defined as movement during rest, was significantly higher in the DdcKI mice than in the wild-type mice at night (p<0.001), and this abnormality was corrected by the treatment (p=0.003; Fig. 5C). The DdcKI mice, but not the treated mice, spent more time drinking at night than the wild-type mice (p=0.013; Fig. 5D). Hanging behavior is a movement that requires motor coordination. The DdcKI mice exhibited less hanging than the wild-type mice, and the treated mice exhibited more hanging than the DdcKI mice (p<0.05 between each pair of groups; Fig. 5E). Rearing is an exploratory behavior, and low levels of rearing have been interpreted as an indicator of anxiety (Crawley et al., 1997; Homanics et al., 1999). The DdcKI mice demonstrated reduced rearing behavior compared with the wild-type mice (p<0.01, 0.034, and 0.002 during the day, at night, and in total, respectively); however, the treated mice did not exhibit this problem (p=0.142, 0.178, and 0.066 between treated and untreated DdcKI mice during the day, at night, and in total, respectively; p=0.540, 0.903, and 0.806 between wild-type and treated DdcKI mice during the day, at night, and in total, respectively; Fig. 5F). Thus, there were no significant differences between the wild-type mice and the treated mice in any of the home-cage analyses.

FIG. 5.

AAV9-hAADC ICV injection corrected the behavioral abnormalities of the DdcKI mice in the home-cage test. Wild-type (WT), untreated (KI), and treated (KI-AAV9) DdcKI mice at 8–9 weeks of age were subjected to home-cage behavior analysis (n=10 for WT and KI; n=5 for KI-AAV9). (A) The KI mice, but not the KI-AAV9 mice, traveled less distance during the day than the WT mice (p=0.001). The KI-AAV9 mice traveled a slightly longer distance at night than the WT and KI mice (p=0.391 and 0.086, respectively). (B) The KI mice, but not the KI-AAV9 mice, walked for a shorter duration during the day than the WT mice (p=0.001). The KI-AAV9 mice walked for slightly longer at night than the WT and KI mice (p=0.270 and 0.142, respectively). (C) The KI mice twitched more at night than the WT (p<0.001) and KI-AAV9 (p=0.003) mice. (D) The KI mice spent more time drinking at night than the WT mice (p=0.013) at night. The KI-AAV9 mice spent a similar amount of time drinking to the WT mice. (E) The KI mice exhibited less hanging behavior than the WT mice (p<0.05) and KI-AAV9 mice (p<0.05); there was no difference in hanging time between the WT and KI-AAV9 mice. (F) The KI mice exhibited less rearing during the day and the night than the WT mice (p<0.05). The KI-AAV9 exhibited a similar amount of rearing to the WT mice.

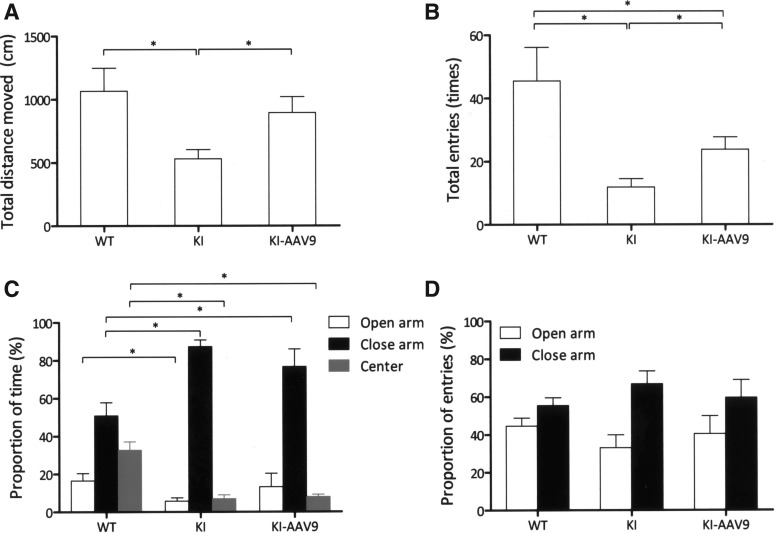

The mice were further subjected to an elevated plus maze test to measure their levels of anxiety. The results revealed that the treated mice exhibited higher levels of activity than the DdcKI mice (p=0.034) and similar activity levels to those of the wild-type mice (p=0.888; Fig. 6A). The total number of entries by the treated mice was higher than the DdcKI mice (p=0.023) but was still lower than the wild-type mice (p=0.034; Fig. 6B). In the proportion of time analysis, the DdcKI mice spent more time in the closed arm but less time in the open arm and center than the wild-type mice (p<0.05; Fig. 6C). The treated mice and the wild-type mice spent a similar amount of time in the open arm (p=0.322), but the former spent more time in the closed arm (p=0.048; Fig. 6C). Therefore, AAV9-hAADC ICV injection partially corrected these behavioral abnormalities in DdcKI mice.

FIG. 6.

AAV9-hAADC ICV injection decreased behavioral abnormalities in the elevated plus maze test. Wild-type (WT), untreated (KI), and treated (KI-AAV9) DdcKI mice at 7–9 weeks of age were subjected to elevated plus maze analysis (n=10 for WT and KI; n=4 for KI-AAV9). (A) The travel distance was similar for the WT and KI-AAV9 mice (p=0.888), but the KI mice traveled less (p=0.002 compared with WT; p=0.034 compared with KI-AAV9). (B) The KI-AAV9 mice showed a higher total number of entries compared with the KI mice (p=0.023) but a lower number of entries compared with the WT mice (p=0.034). (C) In the proportion of time analyses, the KI mice spent less time in the open arms, less time in the center, and more time in the closed arms than WT mice (p=0.049, 0.001, and 0.001, respectively). The treated mice spent a similar amount of time in the open arms to the wild-type mice (p=0.322) but more time in the closed arms (p=0.048). (D) Analyses of the proportion of entries showed no significant differences among the three groups of mice. *p<0.05.

AAV9-hAADC distribution after ICV injection

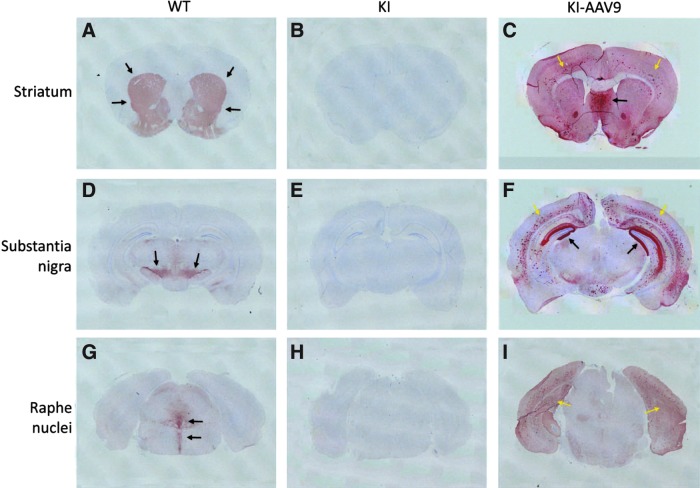

AADC protein expression in the brain after ICV injection was assessed by IHC. In the DdcKI mice, AADC staining was negative, whereas tyrosine hydroxylase staining was positive. However, in the DdcKI mice at 24 weeks after ICV injection, IHC studies revealed widespread AADC expression (Fig. 7C, F, and I). The brain areas with the strongest AADC expression were the septal nuclei, the hippocampus, and the cortex. The distribution of AADC expression was asymmetric and varied among the treated mice. In higher-magnification views of the staining, we observed that few cells in the striatum expressed AADC, but neuronal processes positive for AADC were clearly observed (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Some of the neurons in the substantia nigra (Supplementary Fig. S1F), where the dopaminergic neurons reside, were transduced. In the serotoninergic dorsal raphe nuclei, the ventral part (black arrows) but not the dorsal part (white arrows) was transduced (Supplementary Fig. S1I). Most of the cells expressing AADC in the cortex were glial cells (Supplementary Fig. S1L); however, neurons in the septal nuclei were intensely transduced (Supplementary Fig. S1O). In the extra-nervous system, we found scattered AADC-positive cells in the liver but not in the adrenal medulla (Supplementary Fig. S2).

FIG. 7.

AAV9-hAADC distribution after ICV injection and immunohistochemistry for AADC on mouse brain coronal sections. (A–C) Sections through the striatum. (D–F) Sections through the substantia nigra. (G–I) Sections through the dorsal raphe nucleus. (A) The wild-type (WT) mice showed strong staining throughout the striatum (arrows). (B) The untreated (KI) DdcKI mice showed no staining in the striatum. (C) The treated (KI-AAV9) DdcKI mice showed widespread but asymmetric staining, especially throughout the septal nuclei (black arrow) and cortex (yellow arrows). The striatum was lightly stained. (D) The WT mice showed strong staining throughout the substantia nigra (arrows). (E) The KI mice showed no staining in the substantia nigra. (F) The KI-AAV9 mice showed widespread but asymmetric staining, especially in the hippocampus (black arrow) and cortex (yellow arrows). Staining in the substantia nigra was not observed at this magnification. (G) The WT mice showed positive staining throughout the dorsal raphe nuclei (arrows). (H) The KI mice showed no staining in the dorsal raphe nuclei. (I) The KI-AAV9 mice showed widespread staining in the bilateral cortex (yellow arrows). Staining in the dorsal raphe nuclei was not observed at this magnification.

PET with FDOPA was used to visualize the distribution of AADC activity in the mouse brain. In normal mice, the putamen is the main location of FDOPA uptake (Supplementary Fig. S3A and B, arrows), and no uptake was observed in DdcKI mice. In 5-month-old AAV9-hAADC ICV-injected mice, however, strong but irregular uptake was observed in the brain (Supplementary Fig. S3E–J). Variations in uptake between the treated mice were also prominent. These data were compatible with the results from the IHC analyses.

Immune reaction in neonatal injected mice

Cerebral infusion of AAV9-hAADC into the adult rat brain has been reported to induce cell-mediated immune responses (Ciesielska et al., 2013). We therefore checked for histopathological changes and the proliferation of astrocytes, microglia, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-positive cells in the brains of injected mice at 24 weeks of age. H&E staining revealed no structural changes or abnormal cell infiltration in either treated or untreated DdcKI mice (Supplementary Fig. S4A–C). IHC was then performed using anti-GFAP (to detect astrocytes), anti-Iba1 (to detect microglia), anti-MHC class II, and anti-AADC. The results revealed an aberrant expression of AADC in the brains of DdcKI mice (Supplementary Fig. S4F), but there was no increase in the number of either astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. S4I) or microglia (Supplementary Fig. S4L). MHC class II-positive cells were rarely found in any mice (Supplementary Fig. S4M–O). A possible explanation for the absence of an immune response is immune tolerance in the neonatal injected mice.

Discussion

Correcting dopamine but not serotonin deficiency by ICV injection of AAV9 vector in neonatal mice

Most of the current studies of gene therapy for neurological diseases involve either Parkinson's disease or lysosomal storage diseases (Chtarto et al., 2013). Lysosomal enzymes can be secreted and taken up by other cells, and the overexpression of lysosomal enzymes is usually not harmful. Therefore, precise cell targeting can be unnecessary in gene therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. However, targeting is critical in gene therapy for neurotransmitter deficiencies. In the current study, the distribution of AAV9-hAADC throughout the cerebrum after the ICV injection of neonatal mice was similar to that found in previous studies (Gadalla et al., 2013), but the transduction efficiency in the brain stem has not previously been described in detail. In our study, the efficiency of transduction in the substantia nigra neurons in DdcKI mice was sufficient to replenish brain dopamine levels, but the transduction of the dorsal raphe nuclei neurons was not sufficient to correct the serotonin deficiency. We observed that the dorsal part of the dorsal raphe nuclei was not transduced. Consequently, some of the behavioral abnormalities of the treated DdcKI mice were not completely corrected.

The reason for the low transduction efficiency of the dorsal raphe nuclei is not clear. In the current study, the injection virus dose was 4×1010 vg per mouse, similar to others studies (Gadalla et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013), and CMV promoter is also the most commonly used ubiquitous promoter. However, the virus injected through CSF spaces might have difficulties to reach the raphe nucleus, which is located deeply in the brain stem. AAV9 tropism or CMV promoter expressivity can also be the reasons to explain the low transduction efficiency of the dorsal raphe nuclei.

Risk of widespread brain transduction of genes responsible for neurotransmitter synthesis

Dopamine and serotonin are produced by specific groups of neurons in the brain, and in mice with AADC deficiency, these neurotransmitters cannot be produced. In the current study, however, viral transduction also occurred in cells that normally do not make dopamine or serotonin, such as astrocytes in the cortex and neurons in the septal nuclei. The ectopically expressed AADC was capable of converting l-DOPA to dopamine, as demonstrated by the extensive signal on the PET scan. Certainly, these cells do not synthesize l-DOPA, the substrate to synthesize dopamine, but the large amount of l-DOPA produced by the dopaminergic cells in the treated mice might have made ectopic dopamine synthesis possible. The slight hyperactivity in the treated DdcKI mice may have been related to this mechanism. Although the complications caused by ectopic AADC expression in the treated mice appeared to be subtle, the effects in larger animals or in humans cannot be predicted.

Future challenges

Efforts to increase the transduction efficiency of the raphe nuclei may include a change of viral serotype to improve the tropism, and the employment of a more specific promoter or codon optimization to increase the expression of the transgene. A systemic gene therapy, or more effectively by using in utero gene transfer, appears to be the most desirable treatment for neurotransmitter deficiencies in the future, but correct targeting will be a challenge. Although direct AAV2 injection in the brain has significant limitations, it offers both region- and neuron-specific gene transduction. By contrast, the intravascular injection of AAV9 vectors into adult animals results predominantly in astrocyte transduction in the brain (Foust et al., 2009; Miyake et al., 2011; Rahim et al., 2011). When antigen-presenting cells are transduced, immune reaction is another challenge in systemic gene therapy. Therefore, a vector targeting the neurons in the central nervous system, or perhaps in the peripheral nervous system as well, would be necessary for systemic gene therapy for a neurotransmitter deficiency.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated the efficacy and safety of ICV injection of AAV9-hAADC in neonatal mice with a congenital neurotransmitter deficiency. Widespread AADC expression in the brain was achieved, and the dopamine levels were normalized in the treated mice, resulting in the resolution of motor symptoms. However, ectopic dopamine expression may be a concern, and the transduction of the serotoninergic neurons was not efficient. Therefore, additional effort will be required to further improve gene therapy approaches for neurotransmitter deficiencies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Science Council (NSC 100-2321-B-002-021) of Taiwan. The authors would like to thank the scientists from the Taiwan Mouse Clinic and the National Taiwan University Disease Animal Research Center, both of which are funded by the National Research Program for Biopharmaceuticals.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Abeling N.G., Van Gennip A.H., Barth P.G., et al. (1998). Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: a new case with a mild clinical presentation and unexpected laboratory findings. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 21, 240–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigam C., Wevers R.A., Hyland K., et al. (2000). The influence of L-dopa on methylation capacity in aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: biochemical findings in two patients. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 23, 321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun L., Ngu L.H., Keng W.T., et al. (2010). Clinical and biochemical features of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Neurology 75, 64–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cearley C.N., Vandenberghe L.H., Parente M.K., et al. (2008). Expanded repertoire of AAV vector serotypes mediate unique patterns of transduction in mouse brain. Mol. Ther. 16, 1710–1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chtarto A., Bockstael O., Tshibangu T., et al. (2013). A next step in adeno-associated virus-mediated gene therapy for neurological diseases: regulation and targeting. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 76, 217–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielska A., Hadaczek P., Mittermeyer G., et al. (2013). Cerebral infusion of AAV9 vector-encoding non-self proteins can elicit cell-mediated immune responses. Mol. Ther. 21, 158–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley J.N., Belknap J.K., Collins A., et al. (1997). Behavioral phenotypes of inbred mouse strains: implications and recommendations for molecular studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 132, 107–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cressant A., Desmaris N., Verot L., et al. (2004). Improved behavior and neuropathology in the mouse model of Sanfilippo type IIIB disease after adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer in the striatum. J. Neurosci. 24, 10229–10239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiumara A., Brautigam C., Hyland K., et al. (2002). Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency with hyperdopaminuria. Clinical and laboratory findings in response to different therapies. Neuropediatrics 33, 203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust K.D., Nurre E., Montgomery C.L., et al. (2009). Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 59–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla K.K., Bailey M.E., Spike R.C., et al. (2013). Improved survival and reduced phenotypic severity following AAV9/MECP2 gene transfer to neonatal and juvenile male Mecp2 knockout mice. Mol. Ther. 21, 18–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamosh A., and Mckusick V.A. (2011). DOPA DECARBOXYLASE; DDC. OMIM Database, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD [Google Scholar]

- Homanics G.E., Quinlan J.J., and Firestone L.L. (1999). Pharmacologic and behavioral responses of inbred C57BL/6J and strain 129/SvJ mouse lines. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 63, 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwu W.L., Muramatsu S., Tseng S.H., et al. (2012). Gene therapy for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 134ra61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland K., and Clayton P.T. (1990). Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in twins. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 13, 301–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland K., Surtees R.A., Rodeck C., and Clayton P.T. (1992). Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of a new inborn error of neurotransmitter amine synthesis. Neurology 42, 1980–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.Y., Ash R.T., Ceballos-Diaz C., et al. (2013). Viral transduction of the neonatal brain delivers controllable genetic mosaicism for visualising and manipulating neuronal circuits in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 37, 1203–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenke G.C., Christen H.J., Hyland K., et al. (1997). Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: an extrapyramidal movement disorder with oculogyric crises. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 1, 67–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N.C., Shieh Y.D., Chien Y.H., et al. (2013). Regulation of the dopaminergic system in a murine model of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Neurobiol. Dis. 52C, 177–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.J., Tai Y., Huang M.T., et al. (2010). Cellular localization of the organic cation transporters, OCT1 and OCT2, in brain microvessel endothelial cells and its implication for MPTP transport across the blood-brain barrier and MPTP-induced dopaminergic toxicity in rodents. J. Neurochem. 114, 717–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller A., Hyland K., Milstien S., et al. (1997). Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of a second family. J. Child Neurol. 12, 349–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manegold C., Hoffmann G.F., Degen I., et al. (2009). Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: clinical features, drug therapy and follow-up. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 32, 371–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake N., Miyake K., Yamamoto M., et al. (2011). Global gene transfer into the CNS across the BBB after neonatal systemic delivery of single-stranded AAV vectors. Brain Res. 1389, 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montioli R., Oppici E., Cellini B., et al. (2013). S250F variant associated with aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: molecular defects and intracellular rescue by pyridoxine. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 1615–1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel B.A., Arundell M., Parker K.H., et al. (2005). Simple and rapid determination of serotonin and catecholamines in biological tissue using high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J. Chromatogr. B. Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 818, 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons R., Ford B., Chiriboga C.A., et al. (2004). Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: clinical features, treatment, and prognosis. Neurology 62, 1058–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim A.A., Wong A.M., Hoefer K., et al. (2011). Intravenous administration of AAV2/9 to the fetal and neonatal mouse leads to differential targeting of CNS cell types and extensive transduction of the nervous system. FASEB J. 25, 3505–3518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas G., Guerra M.J., and Labandeira-Garcia J.L. (1997). An automated rotarod method for quantitative drug-free evaluation of overall motor deficits in rat models of parkinsonism. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 2, 75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swoboda K.J., Hyland K., Goldstein D.S., et al. (1999). Clinical and therapeutic observations in aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Neurology 53, 1205–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swoboda K.J., Saul J.P., Mckenna C.E., et al. (2003). Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: overview of clinical features and outcomes. Ann. Neurol. 54Suppl. 6, S49–S55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay S.K., Poh K.S., Hyland K., et al. (2007). Unusually mild phenotype of AADC deficiency in 2 siblings. Mol. Genet. Metab. 91, 374–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek M.M., Geurtz P.B., Willemsen M.A., and Wevers R.A. (2007). Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase enzyme activity in deficient patients and heterozygotes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 90, 363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuckovic M.G., Li Q., Fisher B., et al. (2010). Exercise elevates dopamine D2 receptor in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease: in vivo imaging with [(1)F]fallypride. Mov. Disord. 25, 2777–2784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenberg T., Willemsen M.A., Geurtz P.B., et al. (2010). Urinary dopamine in aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: the unsolved paradox. Mol. Genet. Metab. 101, 349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W.L., Lin Y.W., Min M.Y., and Chen C.C. (2010). Mice lacking Asic3 show reduced anxiety-like behavior on the elevated plus maze and reduced aggression. Genes Brain Behav. 9, 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiss C.J. (2005). Neuroanatomical phenotyping in the mouse: the dopaminergic system. Vet. Pathol. 42, 753–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin S., Potter M., Zolotukhin I., et al. (2002). Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods 28, 158–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.