Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Autoimmune pancreatitis and autoimmune cholangitis are new clinical entities that are now recognized as the pancreaticobiliary manifestations of immunoglobulin (Ig) G4-related disease.

OBJECTIVE:

To summarize important clinical aspects of IgG4-related pancreatic and biliary diseases, and to review the role of IgG4 in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) and autoimmune cholangitis (AIC).

METHODS:

A narrative review was performed using the PubMed database and the following keywords: “IgG4”, “IgG4 related disease”, “autoimmune pancreatitis”, “sclerosing cholangitis” and “autoimmune cholangitis”. A total of 955 articles were retrieved; of these, 381 contained relevant data regarding the IgG4 molecule, pathogenesis of IgG-related diseases, and diagnosis, management and long-term follow-up for patients with AIP and AIC. Of these 381 articles, 66 of the most pertinent were selected.

RESULTS:

The selected studies demonstrated the increasing clinical importance of both AIP and AIC, which can mimic pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma, respectively. IgG4 titration in tissue or blood cannot be used alone to diagnose all IgG4-related diseases; however, it is often a useful adjunct to clinical, radiological and histological features. AIP and AIC respond to steroids; however, relapse is common and long-term maintenance treatment often required.

CONCLUSIONS:

A review of the diagnosis and management of both AIC and AIP is timely and pertinent to clinical practice because the amount of information regarding these conditions has increased substantially in the past few years, resulting in significant impact on the clinical management of affected patients.

Keywords: Autoimmune cholangiopathy, Autoimmune pancreatitis, Cholangiocarcinoma, IgG4, IgG4-related disease, Pancreatic cancer

Abstract

HISTORIQUE:

La pancréatite auto-immune et la cholangite auto-immune sont de nouvelles entités cliniques qu’on reconnaît désormais comme les manifestations pancréatobiliaires des maladies liées à l’immunoglobuline (Ig) G4.

OBJECTIF :

Résumer les aspects cliniques importants des maladies pancréatiques et biliaires liées à l’IgG4 et évaluer le rôle de l’IgG4 dans le diagnostic de la pancréatite auto-immune (PAI) et de la cholangiteautoimmune (CAI).

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont effectué une analyse narrative au moyen de la base de données PubMed et des mots-clés suivants : IgG4, IgG4-related disease, autoimmune pancreatitis, sclerosing cholangitis et autoimmune cholangitis. Au total, ils ont extrait 955 articles, dont 381 contenaient des données pertinentes au sujet de la molécule d’IgG4, la pathogenèse des maladies liées à l’IgG, ainsi que le diagnostic, la prise en charge et le suivi à long terme des patients ayant une PAI et une CAI. Parmi ces 381 articles, ils ont sélectionné 66 des plus pertinents.

RÉSULTATS:

Les études sélectionnées ont démontré l’importance clinique croissante de la PAI tout autant que de la CAI, qui peuvent imiter le cancer pancréatique et le cholangiocarcinome, respectivement. On ne peut pas utiliser le simple titrage de l’IgG4 dans les tissus ou dans le sang pour diagnostiquer toutes les maladies liées à l’IgG4. Cependant, c’est souvent un ajout utile aux caractéristiques cliniques, radiologiques et histologiques. La PAI et la CAI répondent aux stéroïdes, mais les récidives sont courantes, et souvent, un traitement d’entretien à long terme s’impose.

CONCLUSIONS:

Il est opportun et pertinent d’analyser le diagnostic et la prise en charge de la CAI tout autant que de la PAI en pratique clinique, parce que la quantité d’information au sujet de ces maladies a considérablement augmenté depuis quelques années, ce qui a eu des conséquences importantes sur la prise en charge clinique des patients touchés.

Immunoglobulin (Ig) G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a new clinical entity that has unique clinical, serological, radiological and pathological features with multiorgan involvement. A variety of names have been suggested to describe IgG4-RD and many different nomenclatures have been used in the medical literature including IgG4-RD, IgG4-related systemic disease, IgG4-related sclerosing disease, IgG-related systemic sclerosing disease, IgG4 syndrome and IgG4-related autoimmune disease – they all describe the same condition.

Elevated serum or tissue concentrations of IgG4 are helpful in diagnosing IgG4-RD; however, neither is a specific diagnostic marker. It is important to correlate serological and/or tissue elevations of IgG4 with pathological findings. Misdiagnoses of IgG4-RD are increasingly common because of over-reliance on only moderate elevations of serum IgG4 concentrations and the finding of IgG4-positive plasma cells in tissue (1).

The hallmark pathological features of IgG4-RD are dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, the presence of abundant IgG4-positive plasma cells, extensive fibrosis and obliterative fibrosis. Tumorous swelling and eosinophilia are other frequently observed features (2). The term ‘lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis’ includes the first four above-mentioned features (3).

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) and autoimmune cholangitis (AIC) are the pancreaticobiliary manifestations of IgG4-RD; however, multiple organs can be involved (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related diseases

| Organ/system | Disease |

|---|---|

| Lacrimal and salivary glands | Mikulicz’s disease |

| Kuttner’s tumour | |

| Dacroadenitis | |

| Lungs | IgG4 pulmonary diseases |

| Pancreatic/biliary | Autoimmune pancreatitis and autoimmune cholangiopathy |

| Endocrine | Autoimmune hypophysitis |

| Reidel’s fibrosis | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Nervous | Cranial pachymeningitis |

| Kidneys | IgG4-related nephropathy |

| Tubulointerstitial nephropathy | |

| Retroperitoneal fibrosis | |

| Prostatitis | |

| Lymphatic/vascular | IgG4-related lymphadenopathy |

| Castleman’s disease | |

| Aortitis |

IgG4-RD can mimic various diseases (eg, AIP can often be be mistaken for pancreatic cancer) and, thus, it is crucial to establish the correct diagnosis because treatment differs, and because IgG4-RD often responds to steroids. The increased recognition of IgG4-RD is, therefore, leading to a change in practices involving biliopancreatic illnesses, justifying the present timely review. We will summarize important clinical aspects of IgG4-related pancreatic and biliary diseases, including clinical presentation, diagnosis and overall management, and specify the role of IgG4 in the diagnosis of AIP and AIC.

METHODS

A narrative review was performed using PubMed and the following keywords: “IgG4”, “IgG4 related disease”, “autoimmune pancreatitis”, “sclerosing cholangitis” and “autoimmune cholangitis”. A total of 955 articles were retrieved; of these, 381 contained relevant data regarding the IgG4 molecule, pathogenesis of IgG4-RD, diagnosis, management and long-term follow-up for patients with AIP and AIC. The 66 articles most pertinent to the clinical practice of physicians managing patients with digestive diseases were selected and the relevant information organized and abstracted by two of the co-authors (HA and JM).

THE IgG4 MOLECULE

IgG4 is the smallest fraction of the four subclasses of IgG. It constitutes only 3% to 6% of the entire IgG fraction. It is present at mean concentrations of 0.35 mg/mL to 0.51 mg/mL. Unlike other IgG subclasses, the concentration of IgG4 varies greatly among healthy individuals. IgG4 levels generally range from <10 μg/mL to 1.4 mg/mL, with levels >2 mg/mL noted in a few healthy individuals, and levels generally higher in men and older subjects (4).

IgG4 appears to play a significant role in atopic reactions such as eczema, bronchial asthma and bullous skin lesions. IgG4 is also a protective blocking antibody in allergen-induced IgE-mediated reactions apparent in parasitic infections (5).

In contrast to the other IgG subclasses, IgG4 does not activate complement and exhibits a low affinity for target antigens. IgG4 activation is driven by T-helper cell 2 cytokines.

The pathophysiology noted in IgG4-RD is not typical of auto-immune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis; rather, IgG4 antibodies undergo ‘half-antibody exchange’, also referred to as fragment antigen-binding (Fab)-arm exchange. Because the disulfide bonds between the heavy chains of the IgG4 molecule are unstable, dissociations of the noncovalent bonds permit the chains to separate and recombine randomly, such that asymmetric antibodies with two different antigen-combining sites are formed. The resulting bispecific (functionally monovalent) IgG4 molecules are unable to cross-link antigens, thereby losing the ability to form immune complexes apparent in classical autoimmune diseases (1).

The driving force behind IgG4 production is not fully understood, especially because most cytokines found to be involved in promoting or enhancing IgG4 production have similar effects on IgE production. It is unclear whether IgG4 directly mediates the disease process in IgG4-RD or reflects a protective response induced by anti-inflammatory cytokines (3). There is limited evidence that Helicobacter pylori may be an inciting antigen behind IgG mediation (6,7).

These mechanisms may underly many of the clinical presentations of IgG4-RD; in turn, we will discuss AIP and AIC.

AIP

Although a rare disease, AIP has recently gained much notoriety due to its distinctive clinical and pathological features, which may mimic pancreatic cancer. To date, two types of AIP have been indentified: type 1 AIP, which is more common and associated with multisystem organ IgG4 diseases; and type 2 AIP, which tends to be pancreas specific (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of type 1 and type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP)

| Feature | Type 1 AIP | Type 2 AIP |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Elderly | Young |

| Clinical presentation | Painless jaundice | Obstructive jaundice ± acute pancreatitis |

| Histology |

|

Granulocytic epithelial lesion |

| Serum IgG | Elevated in 80% of cases | Normal |

| IgG4-related diseases | Yes | No |

| Association with IBD | Rare | Yes, found in 16% of cases |

| Response to steroids | Yes | Yes |

| Relapse | Common | Rare |

Adapted from reference 8. IBD Inflammatory bowel disease; IgG Immunoglobulin G

Classifications of AIP

Type 1 AIP:

Type 1 AIP is the most common subtype, especially in Japan and Korea. It affects elderly patients, usually in the seventh decade of life, and is also known as lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis due to its rich IgG4 plasma cell and lymphocytic infiltrations noted in the pancreas and other organs. This is the only form of AIP that is associated with extrapancreatic involvement, which can be found in 60% of patients. In fact, type 1 AIP is the pancreatic manifestation of a more generalized IgG4-RD. Serum IgG4 elevations are apparent in 80% of patients with type 1 AIP. This subtype responds to steroids; however, clinical recurrence is common (8,9).

Type 2 AIP:

Type 2 AIP is more common in younger patients, with 16% exhibiting underlying inflammatory bowel disease (10). In contrast to type 1 AIP, type 2 AIP requires histological diagnosis because clinical, serological and imaging findings alone are not sufficient for diagnosis. Associated serum IgG4 elevations are uncommon and there are no extrapancreatic manifestations. This subtype is also steroid responsive and clinical recurrence is very rare. Type 2 AIP remains underdiagnosed because of the diagnostic need for histological confirmation.

Clinical presentation of AIP

The actual incidence of AIP is unknown. The best estimates to date originate from cohort studies involving patients with presumed pancreatic cancer treated with pancreatic resection, and in whom pathological analysis yielded a diagnosis of AIP (11). AIP most often presents with painless obstructive jaundice (75% in type 1 AIP and 50% in type 2 AIP), which is frequently associated with anorexia and weight loss. This presentation is similar to that of adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head, which is one of the main reasons why AIP is mistaken for pancreatic cancer (12,13). Acute attacks of pancreatitis are rare presentations in AIP, as is chronic abdominal pain with narcotic dependency. However, a proportion of patients with AIP can progress to develop chronic pancreatitis, accounting for approximately 4% to 6% of all cases (14). Furthermore, diabetes mellitus and exocrine insufficiency can precede a diagnosis of AIP and may herald its onset; diabetes may develop as a consequence of steroid therapy during the maintenance phase of AIP treatment. Interestingly, it may also resolve after steroid treatment (15). Patients with type 1 AIP may present with signs and symptoms reflecting other organ involvement or other autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and primary biliary cirrhosis (16).

Diagnosis

A syndrome encompassing serological, radiological and pathological evidence, with possible evidence for other organ involvement in the case of type 1 AIP, is required for diagnosis. In fact, various clinical parameters have been incorporated into sets of diagnostic criteria.

Serology:

A positive serology with elevated IgG4 levels has been observed in atopic disorders, parasitic infections, bullous skin disorders and, rarely, autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, primary biliary cirrhosis and Sjögren’s syndrome. Approximately 5% of the normal population and 10% of pancreatic cancer patients have serum IgG4 elevations to >1.4 g/L (17). Therefore, serum IgG4 levels cannot be used as a sole marker to differentiate between AIP and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Because AIP is a rare disease compared with other diseases, it may mimic, in part, an elevated serum IgG4 level in a patient with a low pretest probability of having AIP and is more likely to, in fact, be a false-positive result (18). Compared with IgG4 alone, the combined measurements of serum IgG4 and total IgG may increase the sensitivity for diagnosing AIP. A prospective study involving 82 patients (19) reported the sensitivity of combined measurements of total IgG and IgG4 for AIP to be 68.3%, significantly greater than the 52.5% of IgG4 alone; the respective specificities of 95.5% and 99.1%, however, did not differ. Hamano et al (20) found serum IgG4 levels were elevated significantly in AIP but not in ordinary chronic pancreatitis or other autoimmune disorders. The investigators used a cut-off value for serum IgG4 concentrations of 1.35 g/L that resulted in high rates of diagnostic accuracy (97%), sensitivity (95%) and specificity (97%) in differentiating AIP from pancreatic cancer; total serum IgG was also slightly elevated in AIP. Serum IgG, serum IgG4 and the IgG4/IgG ratio decreased significantly in the 12 of 20 patients with AIP following a four-week course of steroids, in addition to improvements in symptomatology and imaging findings. These findings suggest IgG is produced as a direct response to the presence of an antigen, implicating AIP is an autoimmune disorder. However, given the small statistical power in this study, insufficient conclusions can be drawn as to whether IgG can be used to monitor the response to steroid therapy. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Morsolli et al (21) showed serum IgG4 to be a good marker to distinguish AIP from pancreatic cancer and other autoimmune diseases. However, pooled results showed heterogeneous specificities, sensitivities and ORs, probably due to differing AIP diagnostic criteria. IgG4 was also found to be promising in monitoring response to treatment after four weeks of steroid therapy among patients with high pretreatment levels of IgG4 (21).

Twenty per cent of patients with AIP exhibit low levels of serum IgG4, an entity known as serum-negative IgG4 AIP, probably representing type 2 AIP. This group was also responsive to treatment and less likely to relapse. This was more common in women, patients presenting with acute pancreatitis, segmental pancreatic body and/or tail swelling, and displaying a lack of extra pancreatic organ involvement (22).

Other autoantibodies have been examined in patients with AIP, but none have been found to be specific. Antibodies to carbonic anhydrase and lactoferrin are found most frequently (54% and 73%, respectively) (23). Serum antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor add no additional discriminatory value (19).

Imaging:

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with pancreatic protocol is rapidly becoming the imaging modality of choice to diagnose AIP. Imaging findings diagnostic or highly suggestive of AIP include a diffusely enlarged pancreas with featureless borders and delayed enhancement, with or without a capsule-like rim (24). In contrast, findings highly suggestive of or diagnostic for pancreatic cancer include a low-density mass, dilation and/or cutoff of the pancreatic duct, and distal pancreatic atrophy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveals focal or diffuse pancreatic enlargement that is hypointense in T1-weighted images and slightly hyperintense in T2-weighted images. As with CT, a capsule-like hypointense rim can be observed in T2-weighted magnetic resonance images. MRI cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can show multiple intrahepatic and common bile duct (CBD) strictures (25).

Endoscopy:

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is generally recommended when CT scan/MRI pancreas findings are atypical for AIP. An international multicentre study (26) identified four specific ERCP features of AIP useful in distinguishing between AIP and pancreatic cancer: a long stricture (>1/3 the length of the pancreatic duct); lack of upstream dilation from the stricture (<5 mm); multiple strictures; and side branches arising from the stricture site. In addition to biliary stenting to relieve biliary obstruction and cytology brushings from biliary strictures, obtaining ampullary biopsies can be useful in diagnosing AIP. Kamisawa et al (27) first reported that ampullary biopsies can exhibit IgG4-positive infiltration, defined as >10 cells with positive IgG4 staining per high-power field. This finding is sensitive and specific for AIP compared with pancreatic cancer and patients with papillitis (52% to 80% and 89% to 100%, respectively) (27).

There are no pathognomonic endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) findings in AIP because the findings are apparent in a variety of pancreatic disorders; hence, EUS cannot be used as the sole diagnostic modality. EUS examination and EUS-fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) nonetheless have excellent negative predictive value and can detect a small pancreatic mass not visible on CT scan. It is also the most reliable tool for excluding pancreatic cancer short of a pancreatic resection. The EUS features of AIP include diffuse hypoechoic pancreatic swelling and/or a focal hypoechoic swelling in the head of the pancreas with associated pancreatic duct narrowing (28). Another finding suggestive of AIP is the presence of CBD dilation with a thickened wall. The bile duct wall thickening in AIP displays unique features: it is homogeneous, with an echopoor intermediate layer and hyperechoic outer and inner layers known as a ‘sandwich-pattern’ wall. The wall may reach 5 mm in thickness (29). AIP differs from other forms of pancreatitis, such as alcoholic and hereditary, in the lack of pseudocyst formation. Intraductal calcifications are absent and, if they occur, they tend to develop later in the advanced stages (30). Other EUS parenchymal and ductal changes described in AIP include the presence of hyperechoic foci, hyperechoic strands, lobularity, cysts and shadowing calcifications. In contrast, ductal features of dilation, irregularity or hyperechoic duct margins, and visible side branches are usually EUS features of chronic pancreatitis. Portal vein or superior mesenteric involvement should not preclude a diagnosis of AIP. Although EUS-FNA is sufficient for diagnosing pancreatic cancer, EUS-guided Tru-cut biopsy is essential for diagnosing type 2 AIP because histology is needed.

Histopathological features:

Although histopathological features are considered the gold standard for diagnosing AIP, there is a lack of consensus regarding the histopathological diagnostic criteria of this disease. The inflammatory response is usually limited to the head of the pancreas, with diffuse, but rare, involvement described. Reasons behind this focal distribution remain unclear. The pathological features of both AIP types include periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and inflammatory cellular stroma. It is the intense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration around the ducts that lead to narrowing of the pancreatic and bile ducts. In advanced stages, extensive lobular fibrosis and vein occlusion from the lymphocytic infiltration leads to storiform fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis, which are the distinguishing features of type 1 AIP. Granulocytic epithelial lesions are pathognomonic for type 2 AIP. An acinar neutrophilic infiltrate is an additional unique histological finding in type 2 AIP (30). These features were diagnosed and validated in a study conducted by pathologists on 40 pancreatic resections from AIP patients (31). The significance of IgG4-positive plasma cells as possible pathognomonic and/or diagnostic markers remains to be proven because IgG4-abundant plasma cells have been noted in non-AIP cases. In fact, the sensitivity may be lowered by the patchy distribution of IgG4-positive cells (31). Although a recent retrospective study assessing EUS-FNA, using a 22-gauge needle, provided adequate samples for histopathological diagnosis (32), pathologists usually recommended a Tru-cut biopsy because EUS-FNA samples are usually scanty (ST Chari, personal communication).

Diagnostic classifications:

Various criteria classifications exist to diagnose AIP. The most commonly used is the Mayo Clinic HISORt revised set of criteria (Table 3). The diagnosis of AIP is made using the criteria of histological appearance, typical imaging, positive serology, other organ involvement and response to steroids (33). The Asian diagnostic criteria developed by Japanese and Korean experts for AIP rely on imaging (ERCP ± MRCP) as an essential part of the diagnosis of AIP (34). The diagnosis is established when imaging showing diffuse or focal pancreatic enlargement, in addition to diffuse or focal pancreatic duct narrowing with or without CBD strictures (criterion 1) and one of the other two criteria are met. The latter are serology IgG4 elevation or the presence of autoantibodies (criterion 2) and specific histological findings (criterion 3), or when histology shows the presence of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis in the resected pancreas. Response to steroid therapy is optional for diagnosis (34).

TABLE 3.

The Mayo Clinic HISORt criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis

| Diagnostic criteria | Findings |

|---|---|

| Histology (at least one should be met) |

|

| Imaging (parenchymal and ductal) |

|

| Serology | Elevated IgG4 levels |

| Other organ involvement | Extrapancreatic manifestations |

| Response to steroids | Resolution of pancreatic and extrapancreatic manifestations with steroid therapy |

Adapted from reference 33. hpf High-power field; Ig Immunoglobulin

The International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria were recently developed in an attempt to unify both diagnostic criteria sets. A diagnosis of AIP type 1 can be made using a combination of noninvasive and invasive criteria, and in selected cases after a trial of steroid therapy (Table 4) (35).

TABLE 4.

The International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis

| Feature | Typical | Indeterminate/suggestive |

|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic imaging | Diffuse enlargement with delayed enhancement without low-density mass, ductal dilation or duct cut-off ERCP: Long (>1/3 length of the main pancreatic duct) or multiple strictures without marked upstream dilation |

Segmental/focal enlargement with delayed enhancement ERCP: Segmental/focal narrowing without marked upstream dilation (duct size <5 mm) |

| IgG4 | IgG4 >2 × upper limit of normal value | IgG4 1–2 × upper limit of normal value |

| Histology | (Core biopsy/resection): at least 3 features

|

(Core biopsy): any 2 features

|

| Response to steroids | Rapid (<2 weeks) radiological resolution or marked improvement in pancreatic or extrapancreatic manifestations | Rapid (<2 weeks) radiological resolution or marked improvement in pancreatic or extrapancreatic manifestations |

Adapted from reference 35. ERCP Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancre-atography; hpf High-power field; Ig Immunoglobulin

How to differentiate AIP from pancreatic cancer

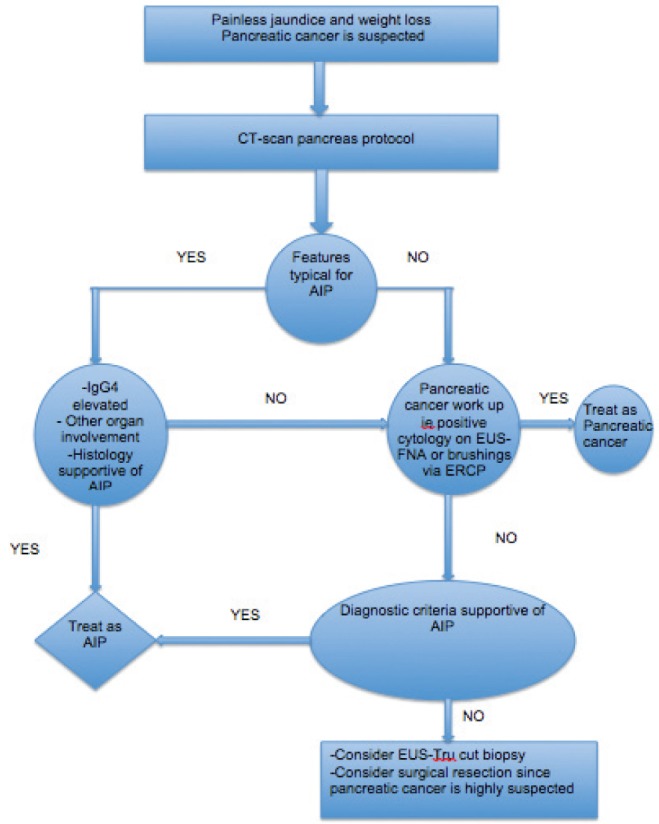

A retrospective study was conducted to compare mass-associated AIP from pancreatic cancer using various clinical, serological, radiological and histological features (36). A capsule-like rim on CT, a skipped lesion of the main pancreatic duct on ERCP or MRCP, a gammaglobulin level >20 g/L, other organ involvement (extrapancreatic biliary stricture, salivary gland swelling and retroperitoneal fibrosis), and the absence of malignant cells on EUS-FNA showed 100% specificity for diagnosing mass-forming AIP. Other individual findings displaying >90% specificity for diagnosing mass-forming AIP include IgG4 >2.80 g/L (98%), IgG4 >1.35 g/L (94%), IgG >1.80 g/L (97%) and a maximal upstream main pancreatic duct diameter <5 mm on MRCP (95%) (36). To help distinguish AIP from pancreatic cancer, a number of differentiating features have been suggested (Figure 1, Table 5) (33).

Figure 1).

Algorithm to differentiate inflammatory mass forming from pancreatic cancer. AIP Autoimmune pancreatitis; CT Computed tomography; ERCP Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS Endoscopic ultrasound; FNA Fine-needle aspiration; Ig Immunoglobulin

TABLE 5.

Features to consider when attempting to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) from pancreatic cancer

| Feature | Clue |

|---|---|

| Epidemiology | AIP is rare, less common than pancreatic cancer |

| Diagnostic criteria | Use the Mayo and other diagnostic criteria mentioned earlier to help diagnose AIP and differentiate it from malignant disease |

| Serology | Serum IgG4 levels are elevated in 5% of healthy individuals, 10% of those with pancreatic cancer, and 6% of those with chronic pancreatitis; an increased IgG4 level is therefore not specific for AIP. Conversely, elevated serum IgG4 levels can decrease in patients with pancreatic cancer inappropriately treated with corticosteroids |

| Trial of steroid therapy | All focal pancreatic masses should be sampled before initiation of corticosteroids. Before initiating corticosteroids, a clinical parameter (ie, symptomatology, serology, radiology) must be identified to monitor an objective response during treatment. Corticosteroids often cause subjective improvement in symptoms even in patients without AIP. Corticosteroid response in AIP is generally seen within 2–4 weeks. If no objective response is documented within 4 weeks, the diagnosis is unlikely to be AIP |

Adapted from reference 33. Ig Immunoglobulin

Management of AIP

Both types of AIP respond to steroids (37). Symptomatic remission refers to the resolution of symptoms of obstructive jaundice and/or pain, usually within two to three weeks of initiating steroids. Serological remission is defined as the normalization of serum IgG or IgG4 levels with steroid therapy. Serum IgG4 concentration does not always return to normal levels, even though radiological remission may be achieved (38). Radiological remission refers to the resolution of the typical enlargement of the pancreas and irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct. Both serological and radiological remission take several weeks to months to achieve, suggesting the need for maintenance therapy. Histological remission has been shown to accompany clinical remission in several reports, but is not usually assessed. Functional remission is defined as restoration of exocrine and/or endocrine function of the pancreas.

All AIP patients should be treated (39,40). In fact, in a multi-centre survey of steroid therapy for AIP (41,42), the remission rate of AIP patients was significantly higher in patients who received steroid therapy than in those not given steroid therapy (94% versus 74% [P<0.01]). The relapse rate of patients with AIP was significantly lower in those who received steroid therapy compared with those not given steroid therapy (24% versus 42% [P<0.01]). The most common induction treatment protocol used is oral prednisone 40 mg/day for four weeks (43), although a lower dose can be used. There was no difference in complete remission between patients treated with 40 mg/day and those treated with 30 mg/day in two Japanese studies (37). The relapse rate with maintenance therapy was significantly lower than patients who stopped maintenance therapy (23% versus 34%) (42,44). In the United States and United Kingdom, where no maintenance therapy was given, relapse rates of patients initially treated with steroids varied between 38% and 60% (42,44). The optimal duration of maintenance remission therapy needs further study; the recommended maintenance dose is 5 mg/day of prednisone for a total of six months, after discussing the benefit/risk ratio of prolonged steroid treatment, including the risks of osteoporosis and avascular necrosis of the hip (45).

The exact role of immunomodulator drugs such as azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil has not been fully established; however, it should be reserved for patients who experience several relapses or for those who are intolerant or resistant to steroid therapy (37,44). Recently, in a small cohort of 10 patients, rituximab was found to be effective in the treatment of steroid-intolerant or immunomodulator-resistant AIP. During a median follow-up of 47 months, 44% of patients with type 1 AIP experienced relapses. These had been treated with steroids or steroid plus an immunomodulator agent, with similar relapse rates in both groups. Forty-five per cent were refractory or intolerant to immunomodulator therapy and were treated with rituximab with an induction dose of 375 mg/m2 every week for four weeks followed by repeat infusion every two to three months for 24 months. Of these, 84% of patients achieved remission with no relapses on maintenance therapy (46).

The role of endoscopy in the management of AIP focuses on relieving biliary obstruction from biliary strictures using metal or plastic stents in patients with associated autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis who present with obstructive jaundice, and also in cases in which pancreatic adenocarcinoma remains a possibility (47,48).

For many years, because of its resemblance to pancreatic adenocarcinoma and lack of knowledge of AIP and IgG4, surgery had been the only treatment for AIP. Abraham et al (50) reported that of 442 Whipple resections, 11 (2.5%) cases turned out to be chronic AIP. In the presence of a pancreatic head mass, a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple resection) was the surgery of choice. Distal and total pancreatectomies were also performed for distal lesions (43,49). No subsequent pharmacotherapy was performed once the diagnosis had been made, with recurrences reported after surgical resection (51).

Long-term outcomes/complications of AIP

Relapse:

Disease relapse is more common in type 1 AIP. The majority of relapses occur within the first three years of initiating medical treatment. Proximal bile duct strictures, diffuse pancreatic swelling and incomplete remission during maintenance therapy are the major predictors of disease relapse in AIP (37).

Pancreatic insufficiency:

Endocrine insufficiency manifested as diabetes mellitus is reported in 26% to 78% of patients with AIP. Several studies have shown improvement of diabetes post-treatment of AIP, whereas one study showed worsening glucose control thereafter (10). Pancreatic stone formation occurs in 19% of AIP patients. The repeated attacks of acute relapsing pancreatitis may lead to pancreatic duct obstruction resulting in stasis of pancreatic secretions and subsequent stone formation (52).

Risk of developing a malignancy:

Because both AIP and pancreatic cancer are rare and may present similarly, it is difficult to estimate the exact prevalence of pancreatic cancer in AIP. However, Kamisawa and Okamoto (52) observed a high frequency of KRAS mutations in pancreatic tissue samples of patients with AIP. The authors hypothesized that long-term inflammmation induces fibrotic changes, leading to KRAS mutation. In a cohort study, the prevalence of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia was examined in resected pancreatic specimens of AIP patients. This finding was similar if not higher than in those with chronic pancreatitis patients, suggesting that AIP may be a risk factor for the subsequent development of pancreatic cancer (53). There are a few reports of solid malignancies and lymphoproliferative disorders in AIP; however, the exact relationship is not known (54). A recent retrospective cohort study was conducted to examine the relationship between AIP and various cancer risks. The study showed that patients with AIP have a higher risk for cancers, which are greatest during the first three years of diagnosis. The RR of cancer among AIP patients was 4.9. The lack of relapse of AIP following treatment of coexisting cancers suggests that AIP also develops as a paraneoplastic phenomenon (55).

Additional data are required to better characterize the long-term prognosis of AIP. The associated development or presence of AIC in a patient with AIP deserves special consideration and is described below.

IgG4 CHOLANGIOPATHY

IgG4 cholangiopathy, IgG4-sclerosing cholangitis or AIC can involve any part of the biliary system ranging from intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, mimicking sclerosing cholangitis to pseudotumourous hilar lesions and even cholangiocarcinoma. Most cases of AIC are associated with AIP. The diagnosis can be challenging in those without evidence of AIP, and relies on a combination of serological, histological and radiological features. It is important to distinguish AIP from primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and hilar cholangiocarcinoma because treatment is different in each case.

AIC predominantly affects large intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, resembling classical PSC; this is the form of AIC noted in 95% of cases and is further discussed below. Small-duct IgG4 cholangiopathy, similar to small-duct PSC, has also been described in the literature. A prospective study showed that small-duct IgG4 cholangiopathy, defined as evidence of bile duct damage with >10 IgG4+ plasma cells per high-power field was present in 26% of patients with AIC. These patients also exhibited a higher incidence of intrahepatic strictures on cholangiographic images (56).

IgG4 autoimmune hepatitis, which is found in 3% of patients with type 1 AIP, has recently been described and may represent part of the spectrum of IgG4 cholangiopathies.

Pathogenesis

AIC is part of the spectrum of IgG4-RD and, as a result, there is considerable overlap between AIP and AIC because both conditions tend to occur concurrently. Intense lymphoplasmocystic infiltrations and high levels of IgG4 are observed in the bile ducts of patients with AIC (57). There is upregulation of T-helper 2 cells, which is surprisingly uncommon in autoimmune disorders (58). Interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor, a powerful inducer of fibrogenesis, are the main cytokines overexpressed in AIC. The exact autoantigen behind IgG4 production remains to be identified.

Clinical features

AIC may be asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally during the work up of other IgG4-RD (eg, retroperitoneal fibrosis) or because of abnormal routine liver enzyme tests. AIC usually presents with obstructive jaundice secondary to a pancreatic head mass, as an inflammatory pseudotumour secondary to associated AIP or as biliary strictures. New-onset diabetes mellitus and weight loss are other reported presentations.

Elevated serum IgG4 levels are the most specific indicator of disease. Other sensitive, but not specific, markers include hypergamma-globulinemia (observed in 50% of patients), high IgG (60% to 70%), antinuclear antibody (40% to 50%) and rheumatoid factor (20%) levels, and eosinophilia (15% to 25%) (59).

Diagnosis

More than 90% of patients with AIC also have AIP. The diagnosis of AIC can be made when biliary strictures are associated with a confirmed diagnosis of AIP using the aformentioned diagnostic criteria. The diagnosis of AIC without associated AIP can be challenging. AIC can resemble PSC (Table 6), and should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of hilar strictures (60). Elevated IgG4 levels alone are not sufficient to diagnose AIC. In fact, patients with AIC can initially present with normal IgG4 levels, but will subsequently exhibit elevated levels during follow-up; therefore, repeated IgG4 testing may be required to confidently exclude a diagnosis of AIC in a patient presenting with a PSC-like picture (61). IgG4 levels were measured in 116 patients with different pancreatic and biliary diseases (62). Thirty-six per cent of patients with PSC had elevated levels of IgG4. However, IgG4 levels were significantly higher among AIC patients. These patients also expressed higher IgG4-positive plasma cell staining in various tissues (63). IgG4 plasma cell infiltration was also more severe in the liver biopsies of patients with AIC (64). Table 6 summarizes the predominant clinical differences between AIC and PSC.

TABLE 6.

Differences between primary sclerosing cholangitis and immunoglobulin (Ig)G4 cholangiopathy

| Feature | Primary sclerosing cholangitis | IgG4 cholangiopathy or autoimmune cholangiopathy |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Young to middle age | Older |

| Obstructive jaundice | Marked | Less severe |

| Biliary strictures | Band-like strictures with beaded and pruned tree appearance | Segmental strictures (distal CBD) |

| Associated autoimmune pancreatitis | No | Yes |

| IgG4-related diseases | No | Yes |

| IBD association | Yes | Rarely associated with type 2 AIP |

| Risk of cholangiocarcinoma | Yes | Rare (with limited data), can mimic |

Management

As with AIP, the mainstay of therapy is steroids (64), with an initial dose of prednisolone 40 mg orally daily for at least four weeks, followed by a slow tapering of 5 mg per week over six months. Relapses are treated with immune modulators such as azathioprine 2 mg/kg to 2.5 mg/kg or mycophenolate mofetil 750 mg orally twice per day, after initiating steroids for the first relapse. In addition, biliary stenting with brushings should be considered in cases for which suboptimal clinical response is achieved (57). Because most patients with AIC have associated AIP, other management issues are as described previously.

CONCLUSION

After initial recognition, AIP and AIC are increasingly diagnosed. Serum or tissue concentrations of IgG4 alone cannot be used to confidently diagnose or exclude these clinical entities. Several various and evolving diagnostic criteria have been developed to aid in diagnosis. The mainstay of treatment is steroids and/or immune modulators in cases of relapse or in patients who are refractory or resistant to steroids. Both clinical conditions should be included in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1104650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khosroshahi A, Stone JH. A clinical overview of IgG4-related systemic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:57–66. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283418057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L, Chari S, Smyrk TC, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) type 1 and type 2: An international consensus study on histopathologic diagnostic criteria. Pancreas. 2011;40:1172–9. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318233bec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nirula A, Glaser SM, Kalled SL, Taylor FR. What is IgG4? A review of the biology of a unique immunoglobulin subtype. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:119–24. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283412fd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen G, Cheuk W, Chan JK. [IgG4-related sclerosing disease: A critical appraisal of an evolving clinicopathologic entity] Zhonghua bing li xue za zhi Chin J Pathol. 2010;39:851–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kountouras J, Zavos C, Chatzopoulos D. A concept on the role of Helicobacter pylori infection in autoimmune pancreatitis. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:196–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kountouras J, Zavos C, Gavalas E, Tzilves D. Challenge in the pathogenesis of autoimmune pancreatitis: Potential role of Helicobacter pylori infection via molecular mimicry. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:368–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugumar A. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2012;41:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balasubramanian G, Sugumar A, Smyrk TC, et al. Demystifying seronegative autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2012;12:289–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sah RP, Chari ST. Autoimmune pancreatitis: An update on classification, diagnosis, natural history and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naitoh I, Nakazawa T, Hayashi K, et al. Clinical differences between mass-forming autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:607–13. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.667147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamisawa T, Chari ST, Giday SA, et al. Clinical profile of autoimmune pancreatitis and its histological subtypes: An international multicenter survey. Pancreas. 2011;40:809–14. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182258a15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sah RP, Chari ST, Pannala R, et al. Differences in clinical profile and relapse rate of type 1 versus type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:140–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: Guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas. 2011;40:352–8. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182142fd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimori I, Tamakoshi A, Kawa S, et al. Influence of steroid therapy on the course of diabetes mellitus in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: Findings from a nationwide survey in Japan. Pancreas. 2006;32:244–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000202950.02988.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de las Heras-Castano G, Castro-Senosiain B, Garcia-Suarez C, et al. [Autoimmune pancreatitis. An infrequent or underdiagnosed entity? Pathological, clinical and immunological characteristics] Gastroenterologia y hepatologia. 2006;29:299–305. doi: 10.1157/13087471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frulloni L, Lunardi C, Simone R, et al. Identification of a novel antibody associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2135–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghazale A, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, et al. Value of serum IgG4 in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis and in distinguishing it from pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1646–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xin L, Liao Z, Hu LH, Li ZS. The sensitivity of combined IgG4 and IgG in autoimmune pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1902. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamano H, Kawa S, Horiuchi A, et al. High serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:732–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morselli-Labate AM, Pezzilli R. Usefulness of serum IgG4 in the diagnosis and follow up of autoimmune pancreatitis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:15–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamisawa T, Takuma K, Tabata T, et al. Serum IgG4-negative autoimmune pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:108–16. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smyk DS, Rigopoulou EI, Koutsoumpas AL, Kriese S, Burroughs AK, Bogdanos DP. Autoantibodies in autoimmune pancreatitis. Int J Rheumatol. 2012;2012:940831. doi: 10.1155/2012/940831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Procacci C, Carbognin G, Biasiutti C, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: Possibilities of CT characterization. Pancreatology. 2001;1:246–53. doi: 10.1159/000055819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamisawa T, Chen PY, Tu Y, et al. MRCP and MRI findings in 9 patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2919–22. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i18.2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalaitzakis E, Webster GJ. Endoscopic diagnosis of biliary tract disease. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2012;28:273–9. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328351436e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A. A new diagnostic endoscopic tool for autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:358–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buscarini E, Lisi SD, Arcidiacono PG, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography findings in autoimmune pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2080–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i16.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buscarini E, Frulloni L, De Lisi S, Falconi M, Testoni PA, Zambelli A. Autoimmune pancreatitis: A challenging diagnostic puzzle for clinicians. Dig Liv Dis. 2010;42:92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chari ST, Kloeppel G, Zhang L, Notohara K, Lerch MM, Shimosegawa T. Histopathologic and clinical subtypes of autoimmune pancreatitis: The Honolulu consensus document. Pancreatology. 2010;10:664–72. doi: 10.1159/000318809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kloppel G, Sipos B, Zamboni G, Kojima M, Morohoshi T. Autoimmune pancreatitis: Histo- and immunopathological features. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(Suppl 18):28–31. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanno A, Ishida K, Hamada S, et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis by EUS-FNA by using a 22-gauge needle based on the International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria. Gastroint Endosc. 2012;76:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gardner TB, Levy MJ, Takahashi N, Smyrk TC, Chari ST. Misdiagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: A caution to clinicians. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1620–3. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otsuki M, Chung JB, Okazaki K, et al. Asian diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: Consensus of the Japan-Korea Symposium on Autoimmune Pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:403–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takuma K, Kamisawa T, Gopalakrishna R, et al. Strategy to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreas cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1015–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i10.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naitoh I, Nakazawa T, Hayashi K, et al. Clinical differences between mass-forming autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:607–13. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.667147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HM, Chung MJ, Chung JB. Remission and relapse of autoimmune pancreatitis: Focusing on corticosteroid treatment. Pancreas. 2010;39:555–60. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181c8b4a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishino T, Toki F, Oyama H, et al. Biliary tract involvement in autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30:76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozden I, Dizdaroglu F, Poyanli A, Emre A. Spontaneous regression of a pancreatic head mass and biliary obstruction due to autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2005;5:300–3. doi: 10.1159/000085287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Araki J, Tsujimoto F, Ohta T, Nakajima Y. Natural course of autoimmune pancreatitis without steroid therapy showing hypoechoic masses in the uncinate process and tail of the pancreas on ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:1063–7. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.8.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamisawa T, Okazaki K, Kawa S, Shimosegawa T, Tanaka M. Japanese consensus guidelines for management of autoimmune pancreatitis: III. Treatment and prognosis of AIP. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:471–7. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamisawa T, Satake K. Clinical management of autoimmune pancreatitis. Advances in medical sciences. 2007;52:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pezzilli R, Cariani G, Santini D, et al. Therapeutic management and clinical outcome of autoimmune pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1029–38. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.584896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raina A, Yadav D, Krasinskas AM, et al. Evaluation and management of autoimmune pancreatitis: Experience at a large US center. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2295–306. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamisawa T, Shimosegawa T, Okazaki K, et al. Standard steroid treatment for autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut. 2009;58:1504–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.172908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hart PA, Topazian MD, Witzig TE, et al. Treatment of relapsing autoimmune pancreatitis with immunomodulators and rituximab: The Mayo Clinic experience. Gut. 2012. Sep 16, (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Kahaleh M, Behm B, Clarke BW, et al. Temporary placement of covered self-expandable metal stents in benign biliary strictures: A new paradigm? (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:446–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahajan A, Ho H, Sauer B, et al. Temporary placement of fully covered self-expandable metal stents in benign biliary strictures: Midterm evaluation (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zamboni G, Luttges J, Capelli P, et al. Histopathological features of diagnostic and clinical relevance in autoimmune pancreatitis: A study on 53 resection specimens and 9 biopsy specimens. Virchows Archiv. 2004;445:552–63. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1140-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abraham SC, Wilentz RE, Yeo CJ, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple resections) in patients without malignancy: Are they all ‘chronic pancreatitis’? Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:110–20. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber SM, Cubukcu-Dimopulo O, Palesty JA, et al. Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis: Inflammatory mimic of pancreatic carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:129–37. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kamisawa T, Okamoto A. Prognosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(Suppl 18):59–62. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta R, Khosroshahi A, Shinagare S, et al. Does autoimmune pancreatitis increase the risk of pancreatic carcinoma?: A retrospective analysis of pancreatic resections. Pancreas. 2013;42:506–10. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31826bef91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishino T, Toki F, Oyama H, Shimizu K, Shiratori K. Long-term outcome of autoimmune pancreatitis after oral prednisolone therapy. Intern Med. 2006;45:497–501. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shiokawa M, Kodama Y, Yoshimura K, et al. Risk of cancer in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:610–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naitoh I, Zen Y, Nakazawa T, et al. Small bile duct involvement in IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis: Liver biopsy and cholangiography correlation. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:269–76. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bjornsson E. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:389–94. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f6a7c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zen Y, Fujii T, Harada K, et al. Th2 and regulatory immune reactions are increased in immunoglobin G4-related sclerosing pancreatitis and cholangitis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1538–46. doi: 10.1002/hep.21697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zen Y, Nakanuma Y. IgG4 cholangiopathy. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:472376. doi: 10.1155/2012/472376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oh HC, Kim MH, Lee KT, et al. Clinical clues to suspicion of IgG4-associated sclerosing cholangitis disguised as primary sclerosing cholangitis or hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1831–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hirano K, Shiratori Y, Komatsu Y, et al. Involvement of the biliary system in autoimmune pancreatitis: A follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:453–64. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(03)00221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hirano K, Kawabe T, Yamamoto N, et al. Serum IgG4 concentrations in pancreatic and biliary diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;367:181–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deheragoda MG, Church NI, Rodriguez-Justo M, et al. The use of immunoglobulin G4 immunostaining in diagnosing pancreatic and extrapancreatic involvement in autoimmune pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nishino T, Oyama H, Hashimoto E, et al. Clinicopathological differentiation between sclerosing cholangitis with autoimmune pancreatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:550–9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Erkelens GW, Vleggaar FP, Lesterhuis W, van Buuren HR, van der Werf SD. Sclerosing pancreato-cholangitis responsive to steroid therapy. Lancet. 1999;354:43–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)00603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takahashi H, Yamamoto M, Suzuki C, Naishiro Y, Shinomura Y, Imai K. The birthday of a new syndrome: IgG4-related diseases constitute a clinical entity. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:591–4. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ghazale A, Chari ST, Zhang L, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis: Clinical profile and response to therapy. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:706–15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]