Abstract

Evolving brain damage following traumatic brain injury (TBI) is strongly influenced by complex pathophysiologic cascades including local as well as systemic influences. To successfully prevent secondary progression of the primary damage we must actively search and identify secondary insults e.g. hypoxia, hypotension, uncontrolled hyperventilation, anemia, and hypoglycemia, which are known to aggravate existing brain damage. For this, we must rely on specific cerebral monitoring. Only then can we unmask changes which otherwise would remain hidden, and prevent adequate intensive care treatment. Apart from intracranial pressure (ICP) and calculated cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), extended neuromonitoring (SjvO2, ptiO2, microdialysis, transcranial Doppler sonography, electrocorticography) also allows us to define individual pathologic ICP and CPP levels. This, in turn, will support our therapeutic decision-making and also allow a more individualized and flexible treatment concept for each patient. For this, however, we need to learn to integrate several dimensions with their own possible treatment options into a complete picture. The present review summarizes the current understanding of extended neuromonitoring to guide therapeutic interventions with the aim of improving intensive care treatment following severe TBI, which is the basis for ameliorated outcome.

Keywords: Microdialysis, Monitoring, Pathophysiology, Pharmacology, Traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

Severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) is associated with a high risk of mortality and persistent deficits, which may preclude successful reintegration, thereby having dramatic consequences not only for the individual patient but also for society due to the tremendous socio-economic burden involved.

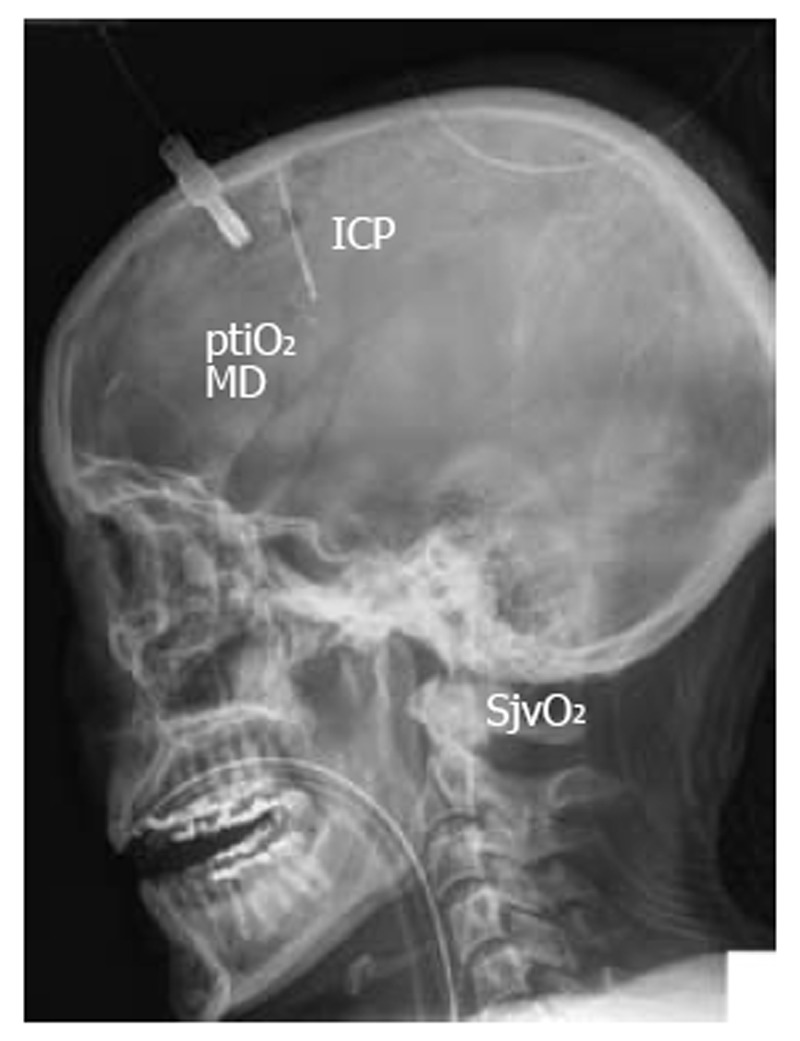

To prevent additional damage to the already injured and highly vulnerable brain, especially during the early posttraumatic phase, specific knowledge is essential. An in-depth understanding of interwoven pathophysiologic cascades must be complemented by specific neuromonitoring. Only then can we unmask the presence and extent of typical secondary insults caused by e.g. hypoxia, hypotension, uncontrolled hyperventilation, hypoglycemia as well as hypoventilation, hypertension, and hyperglycemia. Since secondary insults strongly determine quality of survival, it is of utmost importance to prevent these secondary insults. There is increasing evidence which clearly shows that we cannot rely on intracranial pressure (ICP) and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) alone to assess additional tissue damage. Therefore, extended neuromonitoring has become indispensable in modern intensive care to unmask otherwise occult signs of cerebral impairment, and during phases of normal ICP. Apart from diagnosing signs of secondary deterioration, extended neuromonitoring may be helpful in adapting the quality and extent of our therapeutic interventions. In addition to basic neuromonitoring consisting of ICP and CPP, extended bedside neuromonitoring refers to transcranial Doppler/Duplex sonography (TCD), jugular venous oxygen saturation (SjvO2), partial tissue oxygen pressure (ptiO2), and cerebral microdialysis to unmask changes in brain metabolism (glucose, lactate, pyruvate, glutamate, glycerol), and electrocorticography to determine cortical spreading depression (CSD) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Illustrative lateral X-ray view showing positioning of invasive neuromonitoring to assess intracranial pressure, brain tissue oxygen pressure, brain metabolism using microdialysis, and jugular venous oxygen saturation. ICP: Intracranial pressure; ptiO2: Tissue oxygen pressure; SjvO2: Jugular venous oxygen saturation.

Overall, it is important to refrain from only interpreting one parameter as the different parameters are interwoven and functionally interdependent. Thus, it is important to consider several dimensions simultaneously, integrating e.g. ptiO2, cerebral glucose, CPP, paCO2, and hematocrit. Correct interpretation of these results within the context of the individual situation requires lots of experience in overall clinical management and neuromonitoring. Progressive insight into previously hidden changes which can only be unmasked with extended neuromonitoring is the basis for improved treatment, hopefully resulting in improved outcome following severe TBI.

BASIC NEUROMONITORING

ICP and CPP

Increased intracranial volume reflected by elevated ICP is the primary parameter used to judge cerebral deterioration during pharmacologic coma. A persistent increase in ICP can induce and maintain a vicious circle[1]. It is important to acknowledge that a normal ICP does not guarantee absence of pathologic processes, especially in conditions in which the ICP cannot be assessed adequately e.g. following craniectomy, CSF leakage, subdural air entrapment, or even sensor malfunctioning. New data clearly show that metabolic and functional alterations unmasked by extended neuromonitoring precede increases in ICP[2].

A very simple measure to indirectly estimate global cerebral perfusion is to calculate CPP = mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) - ICP. A “normal” CPP, however, does not guarantee sufficient cerebral perfusion and oxygenation. To define an optimal CPP leading to optimal cerebral perfusion, other parameters e.g. ptiO2, SjvO2, brain metabolism (e.g. glucose, lactate, lactate to pyruvate ratio) and flow velocity must be integrated. Using extraventricular drainage combined with pressure recording allows us to combine diagnostic and therapeutic options by measuring ICP and draining cerebrospinal fluid to reduce elevated ICP, respectively. Extraventricular drainage, however, is associated with an albeit small risk of additional injury to periventricular structures, hemorrhages, and local infections[3].

Jugular venous oxygen saturation and arterio-jugular venous differences

To assess global cerebral perfusion, oxygen consumption, and metabolic state analysis of SjvO2, various metabolic indices (e.g. oxygen-glucose index, lactate-oxygen index, lactate-glucose index), oxygen extraction ratio, and arterio-jugular venous lactate difference have proven helpful at the bedside[4,5]. SjvO2 correlates directly with perfusion and correlates inversely with cerebral oxygen consumption. Thus, SjvO2 can be used to guide therapeutic interventions, including modulation of MABP and CPP, controlling hyperventilation, guiding oxygen administration, and influencing the extent of pharmacologic coma and hypothermia.

Tissue oxygenation- ptiO2

Measuring ptiO2 not only reflects local changes, but also unmasks cerebral consequences of systemic influences e.g. blood pressure, oxygenation, and anemia. This, in turn, allows us to guide the type and extent of therapeutic interventions[6,7]. Similar to changes in SjvO2, ptiO2 values indirectly reflect cerebral perfusion and oxygenation[8], while low SjvO2 and ptiO2 values unmask reduced cerebral perfusion with cerebral ischemia at SjvO2 < 50% and ptiO2 < 10 mmHg. High SjvO2 (> 80%) and ptiO2 values (> 30 mmHg) unmask impaired oxygen consumption encountered under conditions of hyperemia/ luxury perfusion.

It is important to correct ptiO2 values < 10 mmHg (Licox®) within 30 min to prevent hypoxia-induced increase in glutamate[9,10], neuropsychologic deficits[11], and poorer outcome with increased mortality[12].

Cerebral microdialysis

Changes in cerebral metabolism assessed by measuring glucose, lactate, pyruvate, glycerol, glutamate, and by calculating the lactate to pyruvate ratio, a marker of hypoxic/ischemic metabolic impairment[13,14], both follow as well as precede increases in ICP[2,10]. Pathologic alterations reflected by low glucose and elevated lactate to pyruvate ratio were recently identified to significantly predict mortality following severe TBI[15]. In addition, increased lactate to pyruvate ratio was associated with subsequent chronic frontal lobe atrophy[16], possibly giving rise to subsequent dementia. Overall, metabolic monitoring can also be used to guide therapeutic interventions to correct e.g. hypotension, hyperemia, vasospasm, hyperventilation, fever, epileptic discharges, hypoglycemia, and anemia. The integration of cerebral microdialysis was an integral part of the “Lund concept” allowing a reduction in CPP levels as low as 50 mmHg[17], thereby substantially influencing treatment options. For best results in potentially optimizing our current therapy, metabolic monitoring using cerebral microdialysis must be combined with other parameters e.g. ptiO2, SjvO2, and CPP.

TCD

TCD can unmask conditions of low flow[18], vasospasm, and hyperemia. Each of these conditions, in turn, will require differential therapeutic interventions: vasospasm requires controlled hypertension and normo- to hypoventilation; hyperemia requires controlled hypotension and hyperventilation; low flow requires increased cardiac output especially in conjunction with bradycardia. The cerebral blood flow velocity determined within the large basal cerebral arteries can be used to reflect regional cerebral perfusion, cerebral autoregulation, and CO2-reactivity[19]. In addition, calculating e.g. the pulsatility index and resistance index allow the non-invasive estimation of ICP and CPP[20,21]. This proves helpful when an ICP probe cannot be inserted due to coagulation disorder or if an ICP probe is damaged. This allows us to bridge the time until a new ICP probe can be inserted. However, an ICP probe needs to be replaced as soon as possible since only continuous ICP readings can be used to reliably adapt therapeutic interventions.

CSD

CSD involving neuronal and glial energy-consuming depolarizations[22] as well as a spreading wave of ischemia and vasoconstriction with subsequent vasodilation[23], contributes to the secondary growth of a pre-existing lesion[24,25] and is associated with decreased cerebral glucose, increased lactate to pyruvate ratio, and elevated lactate[26,27]. CSD can be induced by elevated extracellular potassium, decreased cerebral NO levels and reduced blood and brain glucose concentrations[28,29]. CSD requires the introduction of a special sensor which is positioned under the dura directly on the cortical surface. At present, it is unclear which patients with which lesions will profit from the application of these sensors.

LIMITATIONS

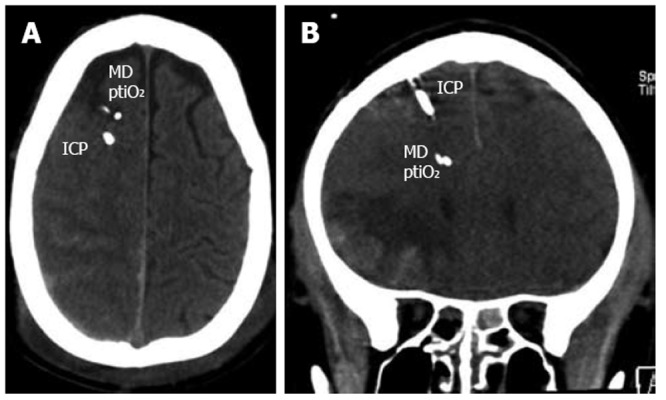

Any neuromonitoring technique is limited by certain restraints making compromises indispensable. Similar to ICP, regional metabolic heterogeneity exists even within the same hemisphere depending on the extension of the lesion and the positioning of the probes relative to the lesion[30,31]. Despite the introduction of multiple probes within the supratentorial compartment the infratentorial areas are not assessed. To prevent additional damage, deep structures such as the basal ganglia are not penetrated under clinical conditions. Furthermore, we must also face local changes at different depths along the probes. To avoid inadequate decision-making the catheters and probes should not be positioned within the core of a contusion as this necrotic tissue will always reveal pathologic values. The consensus recommendation is to place the catheters and probes within the pericontusional tissue to successfully unmask progressive lesion growth, metabolic worsening, and impaired perfusion which may be reversible and amenable to treatment options (Figure 2). In the case of diffuse brain injury, the probes should be positioned within the more severely injured hemisphere. Nonetheless, signs of impaired cerebral metabolism are found even in regions without obvious signs of structural damage. This functional impairment can result from increased ICP due to local changes and can be induced by systemic influences due to e.g. hypotension, hyperemia, vasospasm, hyperventilation, fever, epileptic discharges, hypoglycemia, and anemia.

Figure 2.

Illustrative examples showing positioning of intracranial pressure, microdialysis catheter, and brain tissue oxygen pressure sensor in the more severely injured hemisphere (A) and within close proximity of a contusion (B). ICP: Intracranial pressure; ptiO2: Tissue oxygen pressure.

It is important to acknowledge that local and global monitoring does not exclude each other but successfully extends our insight into otherwise occult changes. In this context, ptiO2 and SjvO2 closely reflect each other[6] and arterio-jugular venous glucose differences have been shown to correspond to local changes in cerebral glucose determined by cerebral microdialysis[32]. Despite these limitations, local as well as global parameters should be monitored in patients with severe TBI who are subjected to pharmacologic coma. Categorically omitting neuromonitoring is a mistake as we deprive ourselves of important information, which is decisive in adapting and modulating our therapeutic interventions. At present, it is difficult to define to what extent basic or extended neuromonitoring significantly determines quality of outcome. In theory, we may expect that the substantial increase in our knowledge using neuromonitoring will translate to improved treatment. By strictly integrating SjvO2, ptiO2, microdialysis, and TCD we are able to individualize the extent, aggressiveness, and duration of therapeutic interventions, thereby reducing the frequency of barbiturate coma, secondary craniectomies, pulmonary dysfunction, and significantly reducing the rate of red blood cell transfusions and associated costs in patients subjected to prolonged pharmacologic coma.

WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF EXTENDED NEUROMONITORING IN ROUTINE INTENSIVE CARE?

While basic neuromonitoring includes neurologic examination, computerized tomography, and ICP, extended neuromonitoring comprises SjvO2, ptiO2, microdialysis, TCD, and electrophysiologic recordings including CSD.

Extended neuromonitoring in daily clinical practice helps to improve our treatment options by characterizing functional influences, defining threshold values, and adapting therapeutic interventions in type, extent and duration. In addition, extended neuromonitoring helps us to prevent induction of additional brain damage due to excessive therapeutic corrections. In this context, aggressive volume administration aimed at improving cerebral perfusion was associated with a sustained risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome[33] and abdominal compartment syndrome[34]. Furthermore, excessive ventilatory support to increase paO2 can induce additional pulmonary damage[35], aggressive lowering of arterial blood glucose to prevent hyperglycemia-induced cell damage increases the frequency and extent of hypoglycemic episodes[36], and a categorical transfusion regimen to improve cerebral oxygenation may be associated with transfusion-related complications[37].

When only relying on changes in ICP and CPP, we may not only miss important signs of deterioration, but also fail to adequately reduce therapeutic interventions. Based on current evidence, extended neuromonitoring is important to determine optimal CPP, guide oxygenation and ventilation, influence transfusion practice, define optimal blood and brain glucose, and even guide decompressive craniectomy.

GUIDANCE FOR CPP

Calculating CPP does not guarantee adequate cerebral perfusion. Assessing ptiO2 is indispensable in determining optimal cerebral perfusion as CPP significantly influences ptiO2[38]. ptiO2 can be used to determine the lower still acceptable CPP value[39]. Several studies have convincingly shown that the generally recommended CPP threshold of 60 mmHg is insufficient and that even “normal” CPP values cannot protect from cerebral hypoxia and impaired metabolism[14]. Furthermore, regional heterogeneity is characterized by different requirements reflected by different levels of CPP-dependent ptiO2 values. In this context, normal CPP of approximately 70 mmHg is insufficient for the perifocal tissue compared to normal appearing tissue in which ptiO2 was significantly higher[40]. Advancing from observational to interventional studies, integrating ptiO2 in clinical routine by using a ptiO2-supplemented ICP- and CPP-based treatment protocol significantly kept ICP < 20 mmHg, improved outcome judged by the Glasgow Outcome Scale, and reduced mortality rate compared to the standard ICP/CPP-directed therapy[41,42].

With the help of monitoring brain metabolism using cerebral microdialysis, CPP can be reduced to low values e.g. 50 mmHg without causing additional brain damage[17]. In this context, lactate and the calculated lactate to pyruvate ratio unmask insufficient cerebral perfusion and oxygen delivery leading to energetic and metabolic impairment[17,43]. As shown using the “Lund concept” to treat patients with severe TBI, microdialysis must be included to allow a reduction in CPP providing the therapeutic concept is practiced as published[17]. Improving cerebral perfusion and correcting anemia has been shown to successfully normalize brain lactate to pyruvate ratio, glycerol, and glutamate levels[43]. Whether this is valid for all lesion types is unclear.

GUIDANCE FOR VENTILATORY SUPPORT: OXYGENATION AND VENTILATION

Integrating ptiO2 and SjvO2 in clinical routine can be used to individually define paO2 and paCO2 targets. These individual targets, in turn, can be used to adjust ventilatory settings, thereby preventing ventilation-induced lung injury and hemodynamic instability.

Oxygenation

Elevating the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) significantly increased ptiO2[38,44] and reduced cerebral lactate[38]. However, increasing ptiO2 too aggressively by normobaric hyperoxia (FiO2 1.0) was associated with decreased cerebral blood flow despite improved brain metabolism. This impaired perfusion coincided with poorer outcome 3 mo after TBI. As shown under experimental conditions, increasing oxygen supply alone is insufficient to improve cerebral oxygenation if impaired cerebral perfusion is not corrected adequately[45].

Hyperventilation

Although hyperventilation is an easy and helpful therapeutic intervention to decrease elevated ICP[46], hyperventilation can induce additional secondary ischemic brain damage[47] due to hypocapnia-induced vasoconstriction. This impaired perfusion, in turn, results in metabolic and neurochemical alterations reflected by reduced ptiO2 and SjvO2, and elevated extracellular glutamate and lactate[48]. Interestingly, even small changes in paCO2 within normal limits are detrimental[49]. Consequently, extended neuromonitoring should also be performed in patients during anticipated normoventilation. It is essential to control hyperventilation by using appropriate neuromonitoring techniques to unmask signs of cerebral ischemia due to hyperventilation-induced vasoconstriction, because normal ICP levels achieved by hyperventilation will cause us to miss relevant pathologic processes within the brain. Reduced SjvO2, decreased ptiO2, and signs of metabolic impairment (lactate, glutamate, lactate to pyruvate ratio)[50,51] aid in assessing the lowest possible individual paCO2 level[52-56]. This helps us to avoid active induction of secondary brain damage.

GUIDANCE FOR RED BLOOD CELL TRANSFUSIONS

Cerebral oxygenation is influenced by the number of circulating oxygen carriers, i.e. red blood cells (hematocrit). At present, the optimal hematocrit following severe TBI is controversial. A fast reduction in hematocrit known to significantly reduce cerebral oxygen supply[57] must be avoided. Under controlled critical care conditions with stable CPP and stable oxygenation and ventilation, ptiO2 can be used to define the transfusion threshold[58,59]. Patients with a ptiO2 > 15 mmHg do not profit from red blood cell transfusion[59]. A transfusion of red blood cells in patients with a hematocrit < 30% and a concomitant ptiO2 value below 15 mmHg was able to persistently increase ptiO2 > 15 mmHg[59]. At the same time, CPP must be maintained above 60 mmHg to prevent cerebral hypoxia determined by ptiO2[59]. These data show that ptiO2 can be used to reliably assess the individual transfusion threshold.

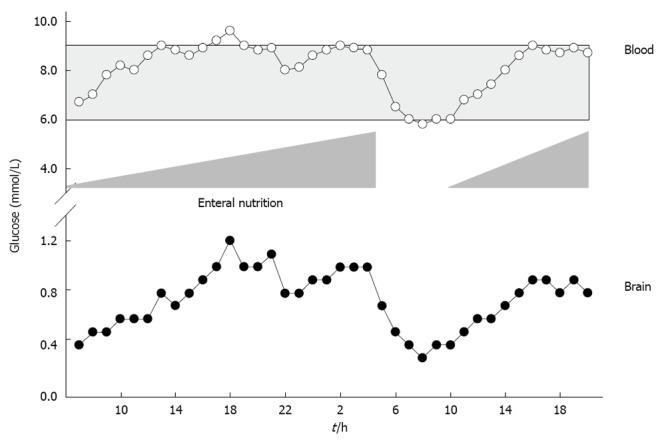

GUIDANCE FOR OPTIMAL BLOOD AND BRAIN GLUCOSE

Mitochondrial damage, aggravated oxidative stress, impaired neutrophil function, reduced phagocytosis, and diminished intracellular destruction of ingested bacteria are deleterious consequences of hyperglycemia. Elevated blood glucose > 9.4 mmol/L (> 169 mg/dL) is associated with sustained mortality and morbidity[60,61]. These deleterious consequences can be prevented by normalizing elevated blood glucose levels. Maintaining blood glucose levels within tight limits between 4.4 mmol/L and 6.1 mmol/L (80 to 110 mg/dL)[62], however, is hampered by the risk of hypoglycemia and a strong variation in blood glucose levels[63], which was associated with sustained mortality[62,64,65]. Reducing blood glucose to 4.4-6.1 mmol/L significantly increased extracellular glutamate levels and elevated lactate to pyruvate ratio, reflecting excessive neuronal excitation and metabolic perturbation[66]. Decreased blood glucose and low cerebral extracellular glucose levels were even associated with sustained mortality[67] and induction of CSD at low blood glucose levels < 5 mmol/L[28,68,69]. To define individual blood and brain glucose, void of any deleterious metabolic consequences, extended neuromonitoring is indispensable. In this context, reduced cerebral oxygen consumption, reduced lactate and CO2 production, increased glucose uptake, elevated cerebral glucose and decreased lactate to pyruvate ratio were observed at arterial blood glucose levels between 6 mmol/L and 9 mmol/L[32]. Based on cerebral microdialysis, insulin should not be given at arterial blood glucose levels < 5 mmol/L as this significantly increased extracellular glutamate and lactate to pyruvate ratio. At arterial blood glucose levels > 9 mmol/L, insulin administration is encouraged to significantly increase cerebral glucose levels and reduce lactate to pyruvate ratio[32,70]. Based on data obtained by microdialysis, brain glucose should remain above 1 mmol/L since cerebral glucose < 1 mmol/L was associated with increased lactate to pyruvate ratio[32,66,71]. Persistently low brain glucose levels were also associated with electrographic seizures, nonischemic reductions in CPP, decreased SjvO2, increased glutamate levels, and poor outcome[71]. Expanding the assessment of brain glucose from mere monitoring to integration into clinical decision-making allows us to guide adaptation of nutritional support, which is a simple measure to increase both blood as well as brain glucose concentrations (Figure 3). Overall, nutritional support has been shown to improve hormonal status and clinical outcome in patients with TBI[72,73].

Figure 3.

Illustrative case showing the influence of enteral nutrition on arterial blood and brain glucose levels. Based on low brain glucose, enteral nutrition was gradually increased resulting in elevated blood and brain glucose. Due to surgery, enteral nutrition was stopped. This resulted in a decrease in blood and brain glucose. Restarting of enteral nutrition increased blood and brain glucose again.

GUIDANCE FOR DECOMPRESSIVE CRANIECTOMY

For patients with uncontrollable intracranial hypertension, decompressive craniectomy with dura enlargement has been shown to improve cerebral perfusion, oxygenation, and metabolism[74-78], reflected by increased ptiO2, decreased lactate to pyruvate ratio, reduced glycerol and glutamate levels[79].

Several reports have shown that pathologic neuromonitoring precedes clinical deterioration[75,78,79]. This, in turn, underscores the importance of integrating extended neuromonitoring in clinical routine to support decision-making on when to perform a decompressive craniectomy[78,79].

CONCLUSION

In the contemporary intensive care of patients with severe TBI subject to pharmacologic coma, basic monitoring using only ICP and CPP should be expanded by extended neuromonitoring including e.g. SjvO2, ptiO2, microdialysis, TCD, and electrocorticography. Growing evidence clearly supports the integration of extended neuromonitoring to unmask otherwise occult alterations and to differentially adapt the type, extent, and duration of our therapeutic interventions. By expanding our knowledge and experience, the integration of extended neuromonitoring in daily clinical routine will provide us with the means to improve outcome, which has not been possible by relying on ICP and CPP values alone as practiced in the past.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Dieter Cadosch, MD, Oberarzt Klinik für Unfallchirurgie, Universitätsspital Zürich, Rämistrasse 100, CH-8091 Zürich, Switzerland

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Smith M. Monitoring intracranial pressure in traumatic brain injury. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:240–248. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000297296.52006.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belli A, Sen J, Petzold A, Russo S, Kitchen N, Smith M. Metabolic failure precedes intracranial pressure rises in traumatic brain injury: a microdialysis study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2008;150:461–49; discussion 470. doi: 10.1007/s00701-008-1580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saladino A, White JB, Wijdicks EF, Lanzino G. Malplacement of ventricular catheters by neurosurgeons: a single institution experience. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10:248–252. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9154-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Møller K, Paulson OB, Hornbein TF, Colier WN, Paulson AS, Roach RC, Holm S, Knudsen GM. Unchanged cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism after acclimatization to high altitude. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:118–126. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holbein M, Béchir M, Ludwig S, Sommerfeld J, Cottini SR, Keel M, Stocker R, Stover JF. Differential influence of arterial blood glucose on cerebral metabolism following severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2009;13:R13. doi: 10.1186/cc7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiening KL, Unterberg AW, Bardt TF, Schneider GH, Lanksch WR. Monitoring of cerebral oxygenation in patients with severe head injuries: brain tissue PO2 versus jugular vein oxygen saturation. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:751–757. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.5.0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenthal G, Hemphill JC, Sorani M, Martin C, Morabito D, Obrist WD, Manley GT. Brain tissue oxygen tension is more indicative of oxygen diffusion than oxygen delivery and metabolism in patients with traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1917–1924. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181743d77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaeger M, Soehle M, Schuhmann MU, Winkler D, Meixensberger J. Correlation of continuously monitored regional cerebral blood flow and brain tissue oxygen. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:51–6; discussion 56. doi: 10.1007/s00701-004-0408-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarrafzadeh AS, Sakowitz OW, Callsen TA, Lanksch WR, Unterberg AW. Bedside microdialysis for early detection of cerebral hypoxia in traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:e2. doi: 10.3171/foc.2000.9.5.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meixensberger J, Kunze E, Barcsay E, Vaeth A, Roosen K. Clinical cerebral microdialysis: brain metabolism and brain tissue oxygenation after acute brain injury. Neurol Res. 2001;23:801–806. doi: 10.1179/016164101101199379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meixensberger J, Renner C, Simanowski R, Schmidtke A, Dings J, Roosen K. Influence of cerebral oxygenation following severe head injury on neuropsychological testing. Neurol Res. 2004;26:414–417. doi: 10.1179/016164104225014094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maloney-Wilensky E, Gracias V, Itkin A, Hoffman K, Bloom S, Yang W, Christian S, LeRoux PD. Brain tissue oxygen and outcome after severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2057–2063. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a009f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tisdall MM, Smith M. Cerebral microdialysis: research technique or clinical tool. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:18–25. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vespa P, Bergsneider M, Hattori N, Wu HM, Huang SC, Martin NA, Glenn TC, McArthur DL, Hovda DA. Metabolic crisis without brain ischemia is common after traumatic brain injury: a combined microdialysis and positron emission tomography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:763–774. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timofeev I, Carpenter KL, Nortje J, Al-Rawi PG, O'Connell MT, Czosnyka M, Smielewski P, Pickard JD, Menon DK, Kirkpatrick PJ, et al. Cerebral extracellular chemistry and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a microdialysis study of 223 patients. Brain. 2011;134:484–494. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcoux J, McArthur DA, Miller C, Glenn TC, Villablanca P, Martin NA, Hovda DA, Alger JR, Vespa PM. Persistent metabolic crisis as measured by elevated cerebral microdialysis lactate-pyruvate ratio predicts chronic frontal lobe brain atrophy after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2871–2877. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186a4a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordström CH, Reinstrup P, Xu W, Gärdenfors A, Ungerstedt U. Assessment of the lower limit for cerebral perfusion pressure in severe head injuries by bedside monitoring of regional energy metabolism. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:809–814. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Santbrink H, Schouten JW, Steyerberg EW, Avezaat CJ, Maas AI. Serial transcranial Doppler measurements in traumatic brain injury with special focus on the early posttraumatic period. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:1141–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00701-002-1012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasulo FA, De Peri E, Lavinio A. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography in intensive care. Eur J Anaesthesiol Suppl. 2008;42:167–173. doi: 10.1017/S0265021507003341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moppett IK, Mahajan RP. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography in anaesthesia and intensive care. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:710–724. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandi G, Béchir M, Sailer S, Haberthür C, Stocker R, Stover JF. Transcranial color-coded duplex sonography allows to assess cerebral perfusion pressure noninvasively following severe traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010;152:965–972. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LEAO AA. Further observations on the spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1947;10:409–414. doi: 10.1152/jn.1947.10.6.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brennan KC, Beltrán-Parrazal L, López-Valdés HE, Theriot J, Toga AW, Charles AC. Distinct vascular conduction with cortical spreading depression. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:4143–4151. doi: 10.1152/jn.00028.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dreier JP, Woitzik J, Fabricius M, Bhatia R, Major S, Drenckhahn C, Lehmann TN, Sarrafzadeh A, Willumsen L, Hartings JA, et al. Delayed ischaemic neurological deficits after subarachnoid haemorrhage are associated with clusters of spreading depolarizations. Brain. 2006;129:3224–3237. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabricius M, Fuhr S, Bhatia R, Boutelle M, Hashemi P, Strong AJ, Lauritzen M. Cortical spreading depression and peri-infarct depolarization in acutely injured human cerebral cortex. Brain. 2006;129:778–790. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krajewski KL, Orakcioglu B, Haux D, Hertle DN, Santos E, Kiening KL, Unterberg AW, Sakowitz OW. Cerebral microdialysis in acutely brain-injured patients with spreading depolarizations. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;110:125–130. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0353-1_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feuerstein D, Manning A, Hashemi P, Bhatia R, Fabricius M, Tolias C, Pahl C, Ervine M, Strong AJ, Boutelle MG. Dynamic metabolic response to multiple spreading depolarizations in patients with acute brain injury: an online microdialysis study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1343–1355. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strong AJ, Hartings JA, Dreier JP. Cortical spreading depression: an adverse but treatable factor in intensive care? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:126–133. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32807faffb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parkin M, Hopwood S, Jones DA, Hashemi P, Landolt H, Fabricius M, Lauritzen M, Boutelle MG, Strong AJ. Dynamic changes in brain glucose and lactate in pericontusional areas of the human cerebral cortex, monitored with rapid sampling on-line microdialysis: relationship with depolarisation-like events. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:402–413. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahuquillo J, Poca MA, Arribas M, Garnacho A, Rubio E. Interhemispheric supratentorial intracranial pressure gradients in head-injured patients: are they clinically important? J Neurosurg. 1999;90:16–26. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.1.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engström M, Polito A, Reinstrup P, Romner B, Ryding E, Ungerstedt U, Nordström CH. Intracerebral microdialysis in severe brain trauma: the importance of catheter location. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:460–469. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.3.0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meierhans R, Béchir M, Ludwig S, Sommerfeld J, Brandi G, Haberthür C, Stocker R, Stover JF. Brain metabolism is significantly impaired at blood glucose below 6 mM and brain glucose below 1 mM in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2010;14:R13. doi: 10.1186/cc8869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robertson CS, Valadka AB, Hannay HJ, Contant CF, Gopinath SP, Cormio M, Uzura M, Grossman RG. Prevention of secondary ischemic insults after severe head injury. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2086–2095. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199910000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.An G, West MA. Abdominal compartment syndrome: a concise clinical review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1304–1310. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31816929f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinheiro de Oliveira R, Hetzel MP, dos Anjos Silva M, Dallegrave D, Friedman G. Mechanical ventilation with high tidal volume induces inflammation in patients without lung disease. Crit Care. 2010;14:R39. doi: 10.1186/cc8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meier R, Béchir M, Ludwig S, Sommerfeld J, Keel M, Steiger P, Stocker R, Stover JF. Differential temporal profile of lowered blood glucose levels (3.5 to 6.5 mmol/l versus 5 to 8 mmol/l) in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:R98. doi: 10.1186/cc6974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cannon-Diehl MR. Transfusion in the critically ill: does it affect outcome? Crit Care Nurs Q. 2010;33:324–338. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e3181f649d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinert M, Barth A, Rothen HU, Schaller B, Takala J, Seiler RW. Effects of cerebral perfusion pressure and increased fraction of inspired oxygen on brain tissue oxygen, lactate and glucose in patients with severe head injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2003;145:341–39; discussion 341-39;. doi: 10.1007/s00701-003-0027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marín-Caballos AJ, Murillo-Cabezas F, Cayuela-Domínguez A, Domínguez-Roldán JM, Rincón-Ferrari MD, Valencia-Anguita J, Flores-Cordero JM, Muñoz-Sánchez MA. Cerebral perfusion pressure and risk of brain hypoxia in severe head injury: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2005;9:R670–R676. doi: 10.1186/cc3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Longhi L, Pagan F, Valeriani V, Magnoni S, Zanier ER, Conte V, Branca V, Stocchetti N. Monitoring brain tissue oxygen tension in brain-injured patients reveals hypoxic episodes in normal-appearing and in peri-focal tissue. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:2136–2142. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0845-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narotam PK, Morrison JF, Nathoo N. Brain tissue oxygen monitoring in traumatic brain injury and major trauma: outcome analysis of a brain tissue oxygen-directed therapy. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:672–682. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.JNS081150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spiotta AM, Stiefel MF, Gracias VH, Garuffe AM, Kofke WA, Maloney-Wilensky E, Troxel AB, Levine JM, Le Roux PD. Brain tissue oxygen-directed management and outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2010;113:571–580. doi: 10.3171/2010.1.JNS09506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ståhl N, Schalén W, Ungerstedt U, Nordström CH. Bedside biochemical monitoring of the penumbra zone surrounding an evacuated acute subdural haematoma. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;108:211–215. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menzel M, Doppenberg EM, Zauner A, Soukup J, Reinert MM, Clausen T, Brockenbrough PB, Bullock R. Cerebral oxygenation in patients after severe head injury: monitoring and effects of arterial hyperoxia on cerebral blood flow, metabolism and intracranial pressure. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1999;11:240–251. doi: 10.1097/00008506-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossi S, Stocchetti N, Longhi L, Balestreri M, Spagnoli D, Zanier ER, Bellinzona G. Brain oxygen tension, oxygen supply, and oxygen consumption during arterial hyperoxia in a model of progressive cerebral ischemia. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18:163–174. doi: 10.1089/08977150150502596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stocchetti N, Maas AI, Chieregato A, van der Plas AA. Hyperventilation in head injury: a review. Chest. 2005;127:1812–1827. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muizelaar JP, Marmarou A, Ward JD, Kontos HA, Choi SC, Becker DP, Gruemer H, Young HF. Adverse effects of prolonged hyperventilation in patients with severe head injury: a randomized clinical trial. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:731–739. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.5.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis DP. Early ventilation in traumatic brain injury. Resuscitation. 2008;76:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hutchinson PJ, Gupta AK, Fryer TF, Al-Rawi PG, Chatfield DA, Coles JP, O'Connell MT, Kett-White R, Minhas PS, Aigbirhio FI, et al. Correlation between cerebral blood flow, substrate delivery, and metabolism in head injury: a combined microdialysis and triple oxygen positron emission tomography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:735–745. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200206000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarrafzadeh AS, Kiening KL, Callsen TA, Unterberg AW. Metabolic changes during impending and manifest cerebral hypoxia in traumatic brain injury. Br J Neurosurg. 2003;17:340–346. doi: 10.1080/02688690310001601234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marion DW, Puccio A, Wisniewski SR, Kochanek P, Dixon CE, Bullian L, Carlier P. Effect of hyperventilation on extracellular concentrations of glutamate, lactate, pyruvate, and local cerebral blood flow in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2619–2625. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unterberg AW, Kiening KL, Härtl R, Bardt T, Sarrafzadeh AS, Lanksch WR. Multimodal monitoring in patients with head injury: evaluation of the effects of treatment on cerebral oxygenation. J Trauma. 1997;42:S32–S37. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199705001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soukup J, Bramsiepe I, Brucke M, Sanchin L, Menzel M. Evaluation of a bedside monitor of regional CBF as a measure of CO2 reactivity in neurosurgical intensive care patients. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2008;20:249–255. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31817ef487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soustiel JF, Mahamid E, Chistyakov A, Shik V, Benenson R, Zaaroor M. Comparison of moderate hyperventilation and mannitol for control of intracranial pressure control in patients with severe traumatic brain injury--a study of cerebral blood flow and metabolism. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:845–51; discussion 851. doi: 10.1007/s00701-006-0792-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carmona Suazo JA, Maas AI, van den Brink WA, van Santbrink H, Steyerberg EW, Avezaat CJ. CO2 reactivity and brain oxygen pressure monitoring in severe head injury. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3268–3274. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200009000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ekelund A, Reinstrup P, Ryding E, Andersson AM, Molund T, Kristiansson KA, Romner B, Brandt L, Säveland H. Effects of iso- and hypervolemic hemodilution on regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen delivery for patients with vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:703–12; discussion 712-3. doi: 10.1007/s00701-002-0959-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith MJ, Stiefel MF, Magge S, Frangos S, Bloom S, Gracias V, Le Roux PD. Packed red blood cell transfusion increases local cerebral oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1104–1108. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000162685.60609.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leal-Noval SR, Rincón-Ferrari MD, Marin-Niebla A, Cayuela A, Arellano-Orden V, Marín-Caballos A, Amaya-Villar R, Ferrándiz-Millón C, Murillo-Cabeza F. Transfusion of erythrocyte concentrates produces a variable increment on cerebral oxygenation in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a preliminary study. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1733–1740. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang JJ, Youn TS, Benson D, Mattick H, Andrade N, Harper CR, Moore CB, Madden CJ, Diaz-Arrastia RR. Physiologic and functional outcome correlates of brain tissue hypoxia in traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:283–290. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318192fbd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Beek JG, Mushkudiani NA, Steyerberg EW, Butcher I, McHugh GS, Lu J, Marmarou A, Murray GD, Maas AI. Prognostic value of admission laboratory parameters in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:315–328. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeremitsky E, Omert LA, Dunham CM, Wilberger J, Rodriguez A. The impact of hyperglycemia on patients with severe brain injury. J Trauma. 2005;58:47–50. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000135158.42242.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P, Bouillon R. Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1359–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bilotta F, Caramia R, Cernak I, Paoloni FP, Doronzio A, Cuzzone V, Santoro A, Rosa G. Intensive insulin therapy after severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized clinical trial. Neurocrit Care. 2008;9:159–166. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Meersseman W, Wouters PJ, Milants I, Van Wijngaerden E, Bobbaers H, Bouillon R. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:449–461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van den Berghe G, Schoonheydt K, Becx P, Bruyninckx F, Wouters PJ. Insulin therapy protects the central and peripheral nervous system of intensive care patients. Neurology. 2005;64:1348–1353. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158442.08857.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vespa P, Boonyaputthikul R, McArthur DL, Miller C, Etchepare M, Bergsneider M, Glenn T, Martin N, Hovda D. Intensive insulin therapy reduces microdialysis glucose values without altering glucose utilization or improving the lactate/pyruvate ratio after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:850–856. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201875.12245.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oddo M, Schmidt JM, Carrera E, Badjatia N, Connolly ES, Presciutti M, Ostapkovich ND, Levine JM, Le Roux P, Mayer SA. Impact of tight glycemic control on cerebral glucose metabolism after severe brain injury: a microdialysis study. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3233–3238. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strong AJ, Smith SE, Whittington DJ, Meldrum BS, Parsons AA, Krupinski J, Hunter AJ, Patel S, Robertson C. Factors influencing the frequency of fluorescence transients as markers of peri-infarct depolarizations in focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2000;31:214–222. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hopwood SE, Parkin MC, Bezzina EL, Boutelle MG, Strong AJ. Transient changes in cortical glucose and lactate levels associated with peri-infarct depolarisations, studied with rapid-sampling microdialysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:391–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Béchir M, Meierhans R, Brandi G, Sommerfeld J, Fasshauer M, Cottini SR, Stocker R, Stover JF. Insulin differentially influences brain glucose and lactate in traumatic brain injured patients. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:896–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vespa PM, McArthur D, O'Phelan K, Glenn T, Etchepare M, Kelly D, Bergsneider M, Martin NA, Hovda DA. Persistently low extracellular glucose correlates with poor outcome 6 months after human traumatic brain injury despite a lack of increased lactate: a microdialysis study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:865–877. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000076701.45782.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chiang YH, Chao DP, Chu SF, Lin HW, Huang SY, Yeh YS, Lui TN, Binns CW, Chiu WT. Early Enteral Nutrition and Clinical Outcomes of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Patients in Acute Stage: A Multi-Center Cohort Study. J Neurotrauma. 2011:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chourdakis M, Kraus MM, Tzellos T, Sardeli C, Peftoulidou M, Vassilakos D, Kouvelas D. Effect of Early Compared With Delayed Enteral Nutrition on Endocrine Function in Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: An Open-Labeled Randomized Trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1177/0148607110397878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jaeger M, Soehle M, Meixensberger J. Effects of decompressive craniectomy on brain tissue oxygen in patients with intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:513–515. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Strege RJ, Lang EW, Stark AM, Scheffner H, Fritsch MJ, Barth H, Mehdorn HM. Cerebral edema leading to decompressive craniectomy: an assessment of the preceding clinical and neuromonitoring trends. Neurol Res. 2003;25:510–515. doi: 10.1179/016164103101201742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jaeger M, Soehle M, Meixensberger J. Improvement of brain tissue oxygen and intracranial pressure during and after surgical decompression for diffuse brain oedema and space occupying infarction. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;95:117–118. doi: 10.1007/3-211-32318-x_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reithmeier T, Löhr M, Pakos P, Ketter G, Ernestus RI. Relevance of ICP and ptiO2 for indication and timing of decompressive craniectomy in patients with malignant brain edema. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:947–51; discussion 952. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0543-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boret H, Fesselet J, Meaudre E, Gaillard PE, Cantais E. Cerebral microdialysis and P(ti)O2 for neuro-monitoring before decompressive craniectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:252–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ho CL, Wang CM, Lee KK, Ng I, Ang BT. Cerebral oxygenation, vascular reactivity, and neurochemistry following decompressive craniectomy for severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:943–949. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/5/0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]