Abstract

Asymmetric diadenosine 5′,5′″-P1,P4-tetraphosphate (Ap4A) hydrolases are members of the Nudix superfamily that asymmetrically cleave the metabolite Ap4A into ATP and AMP while facilitating homeostasis. The obligate intracellular mammalian pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis possesses a single Nudix family protein, CT771. As pathogens that rely on a host for replication and dissemination typically have one or zero Nudix family proteins, this suggests that CT771 could be critical for chlamydial biology and pathogenesis. We identified orthologs to CT771 within environmental Chlamydiales that share active site residues suggesting a common function. Crystal structures of both apo- and ligand-bound CT771 were determined to 2.6 Å and 1.9 Å resolution, respectively. The structure of CT771 shows a αβα-sandwich motif with many conserved elements lining the putative Nudix active site. Numerous aspects of the ligand-bound CT771 structure mirror those observed in the ligand-bound structure of the Ap4A hydrolase from Caenorhabditis elegans. These structures represent only the second Ap4A hydrolase enzyme member determined from eubacteria and suggest that mammalian and bacterial Ap4A hydrolases might be more similar than previously thought. The aforementioned structural similarities, in tandem with molecular docking, guided the enzymatic characterization of CT771. Together, these studies provide the molecular details for substrate binding and specificity, supporting the analysis that CT771 is an Ap4A hydrolase (nudH).

Found throughout all kingdoms of life, Nudix hydrolases are a superfamily of metal-dependent (typically Mg2+) enzymes that catalyze the cleavage of nucleoside diphosphates linked to any other moiety X (Nudix) 1. These proteins serve to maintain physiological homeostasis by modulating levels of signaling molecules and potentially toxic metabolic intermediates 2. Enzymes of this family are characterized by a structurally conserved metal-and-substrate binding catalytic loop-helix-loop ‘Nudix’ motif (comprising 23 amino acids, GX5EX7REUXEEXGU where U is preferably a hydrophobic residue), which forms one edge of the putative active site 1. Despite a diverse range of substrates, a conserved αβα-sandwich scaffold is present within all structurally studied Nudix hydrolases. Substrate specificity is thus determined by side chains outside the Nudix motif, which further subdivides this superfamily, and includes dinucleotide polyphosphatases (e.g. diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) hydrolases), nucleotide sugar pyrophosphatases, ribo- and deoxyribonucleotide triphosphatases, among others 2.

Ap4A hydrolase subfamily members are found throughout all kingdoms of life with previous phylogenetic analyses suggesting the subdivision of plant/bacterial and mammalian/archeal enzymes into two distinct classes 2, 3. Studies detailing structural insights of substrate binding and enzyme mechanics have been revealed within plant 4, 5, bacterial 6, 7 and mammalian 8 enzymes. Asymmetric cleavage of the substrate, Ap4A, results in the generation of ATP and AMP (EC 3.6.1.17). While the biological role of Ap4A is not completely understood, it is found at micromolar intracellular concentrations in both eukaryotes and eubacteria 9 and typically accumulates as a result of protein synthesis when aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are charged with their cognate amino acid 10. Ap4A levels have also been implicated in a variety of signaling pathways including apoptosis 11, DNA repair 12, pathogenesis 13 and as a link between transcription and protein synthesis 10, among others.

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium that replicates within a parasitophorus vacuole, termed the inclusion. A distinguishing feature of Chlamydia is its virulence-defining developmental cycle that involves an infectious, metabolically inactive form (elementary body or EB) and noninfectious, replicative form (reticulate body or RB) 14. After host cell entry and formation of the inclusion by an EB, a burst of nascent bacterial metabolism is initiated that coincides with the EB-to-RB morphological transition. As Chlamydia have coevolved with their human host, reductive evolution has resulted in the loss of numerous genes involved in substrate and oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in a limited ability to manufacture ATP and an energetically parasite-like existence 15, 16. Thus, the ability to salvage and utilize nucleotide intermediates (such as Ap4A) within the inclusion, whether chlamydial-generated or imported from the host cell, is likely crucial to basic bacterial biology as well as pathogenesis. BLAST analysis of the Chlamydia trachomatis genome reveals the presence of a single ORF containing a Nudix motif, CT771 (Chlamydia trachomatis ORF 771), which is annotated as a 17.4 kDa MutT/Nudix family protein and is conserved across all sequenced Chlamydiaceae members. Typically, pathogens that rely on a host for replication and dissemination (e.g. Rickettsia, Borrelia, mycoplasmas, etc.) lack or have a single Nudix family enzyme 1, suggesting the singular presence of a Nudix protein could be of critical importance to Chlamydia. In order to further characterize CT771 as a Nudix subfamily member, a crystal structure of CT771 was determined to 2.60 Å. Structural homology with Ap4A hydrolase members as well as examination of the putative active site through molecular docking guided the subsequent enzymatic characterization of CT771. Finally, a co-crystal structure of CT771 bound to products of Ap4A hydrolysis was determined to 1.9 Å, which ultimately provided the mechanistic details of substrate binding and specificity for CT771, as well as confirmed its functional role as an Ap4A hydrolase (nudH).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, Overexpression, and Purification of Recombinant CT771

A gene fragment encoding the entire open reading frame (residues 1–150) of CT771 was amplified from C. trachomatis (serovar 434/Bu) genomic DNA via PCR and subcloned into BamHI-digested expression plasmid pTBSG through ligation independent cloning 17. Upon DNA sequence confirmation, the vector was transformed into BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells. This strain was grown to an OD600 of 0.8 at 37°C in Terrific Broth supplemented with Ampicillin (100 μg/ml), and protein expression was induced overnight at 17 °C by the addition of isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) to a 1 mM final concentration. Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole), and then lysed by microfluidization. The soluble tagged protein was collected in the supernatant following centrifugation of the cell homogenate and purified on a Ni2+-NTA-Sepharose column according to published protocols 18. Recombinant tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease was used to digest the fusion affinity tag from the target protein. After desalting into 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), final purification was achieved by ResourceQ anion-exchange and gel filtration chromatography (GE Healthcare). The purified protein was concentrated to 10 mg/ml and buffer exchanged by ultrafiltration into 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and stored at 4 °C for further use.

Crystallization

Recombinant C. trachomatis CT771 was crystallized by vapor diffusion in Compact Jr. (Emerald Biosystems) sitting drop plates at 20 °C. Specifically, 0.5 μl of protein solution (10 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl) was mixed with 0.5 μl of reservoir solution containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) and 1.5 M ammonium sulfate, from the Salt Rx HT screen condition F3 (Hampton Research), and equilibrated against 75 μl of the reservoir solution. Single bipyramidal-shaped crystals appeared after 1 day and continued to grow for ~3 days. Crystals were flash-cooled through serial dilution in a cryoprotectant solution consisting of 2.0 M ammonium sulfate with an increasing concentration of glycerol (5%, 10%, 20% (v/v) final).

Prior to cocrystallization, CT771 (10 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl) was incubated on ice with 10 mM Ap4A (Sigma, reconstituted in 10 mM MgCl2) for 15 minutes. Upon mixing 0.5 μL of the protein/Ap4A solution with 0.5 uL reservoir solution containing 200 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) and 25% (w/v) PEG 3350, from the Index HT screen condition H1 (Hampton Research), single block shaped crystals appeared after 1 day and continued to grow in size for up to 5 days. Crystals were harvested by flash-cooling in a cryoprotectant solution consisting of 80% mother liquor and 20% (v/v) glycerol and prepared for X-ray diffraction.

Diffraction Data Collection, Structure Determination, Refinement and Analysis

Monochromatic X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100K using a Dectris Pilatus 6M pixel array detector at beamline 17ID at the APS IMCA-CAT (Table I). Individual reflections were integrated with XDS 19 and scaled with Aimless 20, which suggested the Laue class was 6/mmm with a likely space group of P6122 or P6522 for the apo-CT771 crystals and C2 for the CT771/AMP-PO4 cocrystals.

Table 1.

| CT771-apo | CT771-AMP-PO4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | |||

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a=116.4, c=84.1 |

a=182.5, c=65.4 β=94.0 |

b=102.8, |

| Space group | P6522 | C2 | |

| Resolution (Å)1 | 64.57-2.60 (2.72-2.60) | 89.53-1.90 (1.93-1.90) | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 | |

| Observed reflections | 206,611 | 317,054 | |

| Unique reflections | 10,818 | 96,781 | |

| <I/σ(I)>1 | 30.9 (2.2) | 15.7 (2.1) | |

| Completeness (%)1 | 100 (100) | 99.0 (99.6) | |

| Multiplicity1 | 19.1 (20.4) | 3.4 (3.4) | |

| Rmerge (%)1,2 | 7.4 (151.6) | 4.0 (61.7) | |

| Rmeas (%)1, 4 | 7.8 (159.0) | 4.7 (73.4) | |

| Rpim (%)1, 4 | 2.4 (47.9) | 2.5 (39.3) | |

| CC1/25 | 100.0 (76.7) | 99.9 (74.3) | |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 38.1 - 2.6 | 39.6 - 1.9 | |

| Reflections (working/test) | 10,788/520 | 93,746/4,696 | |

| Rfactor / Rfree (%)3 | 18.9/21.7 | 20.4/25.0 | |

| No. of

atoms (Protein/Ligand/Water) |

1162/11/9 | 9024/256/327 | |

| Model Quality | |||

| R.m.s deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 | 0.015 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.139 | 0.874 | |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | |||

| All Atoms | 71.7 | 56.8 | |

| Protein | 71.8 | 57.2 | |

| Ligand | n/a | 52.7 | |

| Solvent | 69.3 | 51.3 | 1 |

| Coordinate error (Å),

maximum likelihood (Å) |

0.28 | 0.27 | |

| Ramachandran Plot | |||

| Most favored (%) | 93.8 | 96.3 | |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 5.5 | 3.6 | |

| Outliers (%) | 0.7 | 0.1 | |

| PDB ID | 4ILQ | 4MPO | |

Values in parenthesis are for the highest resolution shell.

Rmerge = ∑hkl∑i ∣Ii(hkl) - <I(hkl)>∣ / ∑hkl∑i Ii(hkl), where Ii(hkl) is the intensity measured for the ith reflection and <I(hkl)> is the average intensity of all reflections with indices hkl.

Rfactor = ∑hkl ∥Fobs (hkl) ∣ - ∣Fcalc (hkl) ∥ / ∑hkl ∣Fobs (hkl)∣; Rfree is calculated in an identical manner using 5% of randomly selected reflections that were not included in the refinement.

Initial phase information was obtained for the apo-CT771 structure by maximum-likelihood molecular replacement using BALBES 21. Both of the likely space groups were analyzed, with only P6522 producing a potential solution. Specifically, 134 residues of chain B from PDB entry 3I7V (Aquifex aeolicus Ap4A hydrolase) were altered to reflect the sequence of CT771 (residues 13 – 148), and the resulting hypothetical structure was used as a search model. The top solution contained a single copy of CT771 in the asymmetric unit, which corresponded to a Matthew’s coefficient 22 of 4.66 Å3/Da and a solvent content of 73.6%. The final refined CT771 structure was used as a search model for the CT771/AMP-PO4 dataset, and the top solution contained eight copies of CT771 in the asymmetric unit with a Matthew’s coefficient of 2.35 Å3/Da and a solvent content of 47.7%.

Structure refinement for the apo-CT771 structure was carried out using Phenix 23, 24. One round of individual coordinates and isotropic atomic displacement factor refinement was conducted, and the refined model was used to calculate both 2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc difference maps. These maps were used to iteratively improve the model by manual building with Coot 25, 26 followed by subsequent refinement cycles. TLS refinement 27 was incorporated in the final stages to model anisotropic atomic displacement parameters. Hydrogen atoms were included during all rounds of refinement. Ordered solvent molecules were added according to the default criteria of Phenix and inspected manually using 2Fo-Fc weighted feature enhanced (FEM) electron density maps (contoured at 1.0 σ) within Coot prior to model completion. Residues 1-3 were not modeled as a result of poor map quality.

The CT771/AMP-PO4 cocrystal structure was refined in a similar manner as described above. Regions of poor map quality with the CT771/AMP-PO4 cocrystal structure prevented modeling of residues 1-4 and 149-150 in all chains (with the exception of chain B, where residues 1-4 were modeled and chain C, where residue 4 was modeled). The following residues were not modeled: chain F, 147-148; chain G, 18-21, 84-88. Disordered side chains were truncated to the point where electron density could be observed. Additional information and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1.

Kinetic Characterization of CT771

A luciferase-based bioluminescence assay was used to characterize the kinetic constants of wild-type CT771 enzyme via the detection of liberated ATP. Each 100 μL assay mixture was comprised of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1.5 – 5.0 mM MgCl2 or MnCl2, 10 μL of reconstituted rL/L Reagent (Promega), 10 uL of Ap4A at varying concentrations (Sigma) and 10 ng of purified CT771, and was incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes before measurements were taken. Light output was measured on a Biotek Synergy 2 luminometer and converted into units of enzyme activity (μM/min) using an ATP standard calibration curve. All reactions were measured in triplicate and data interpretation was carried out using GraphPad (GraphPad Software). Additional information is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Kinetic Constants for Ap4A Hydrolysis by CT771

| Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 mM MnCl2 | 7.28 ± 0.65 | 1.60 ± 1.75 | 2.2 × 105 |

| 3.0 mM MnCl2 | 9.35 ± 0.36 | 1.51 ± 0.85 | 1.6 × 105 |

| 5.0 mM MnCl2 | 4.98 ± 0.45 | 0.68 ± 0.90 | 1.4 × 105 |

| 1.5 mM MgCl2 | 407 ± 21 | 1.78 ± 0.04 | 4.4 × 103 |

| 3.0 mM MgCl2 | 326 ± 42 | 2.24 ± 0.11 | 6.9 × 103 |

| 5.0 mM MgCl2 | 333 ± 27 | 3.25 ± 0.10 | 9.8 × 103 |

Ligand Docking

A model for diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A), 8-deoxy-dGTP, adenosine diphosphate ribose and GDP-mannose were generated using the PRODRG server 28. Polar hydrogens were added to ligands prior to docking. Docking calculations were carried out with the refined crystal structure of CT771 using AutoDock Vina, a comprehensive program for molecular docking and virtual screening 29. As grid maps are calculated automatically in AutoDock Vina, only the size and location of search space is required. The grid box was set to 60 × 60 × 60 Å with grid points spaced every 0.375 Å and centered within the putative Nudix family active site cleft. Docking simulations were performed at physiological conditions (37° C). Theoretical dissociation constants were calculated for the lowest energy site using the following equation: ΔG = RT*ln(Kd). Only ligands docked within the putative active site cleft were analyzed. Additional information is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

AutoDock Vina Results

| Ligand | ΔG (kcal/mol) | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) | −6.3 | 36.2 |

| Adenosine diphosphate Ribose | −5.8 | 81.4 |

| GDP-Mannose | −5.6 | 113 |

| 8-deoxy-dGTP | −4.5 | 672 |

Multiple Sequence Alignments and Figure Modeling

Multiple sequence alignments were carried out using ClustalW 30 and aligned with secondary structure elements using ESPRIPT 31. The Ap4A hydrolase sequences used in alignments, along with their respective GenBank™ accession numbers, are as follows: C trachomatis serovar 434/Bu (166154113); Parachlamydia acanthamoebae (282890520); Candidatus Protochlamydia (46446871); Simkania negevensis (338733601); Waddlia chondrophila (297621593); Homo sapiens (4502125); Caenorhabditis elegans (17509897); Aquifex aeolicus (15605731). Three-dimensional structures were superimposed using the Local-Global Alignment method (LGA) 32. The Ap4A hydrolase structures obtained from the PDB 33 are as follows: Homo sapiens (3U53); Caenorhabditis elegans (1KTG); Aquifex aeolicus (3I7V). Representations of all structures were generated using PyMol 34. Calculations of electrostatic potentials at the molecular surface were carried out using DELPHI 35.

RESULTS

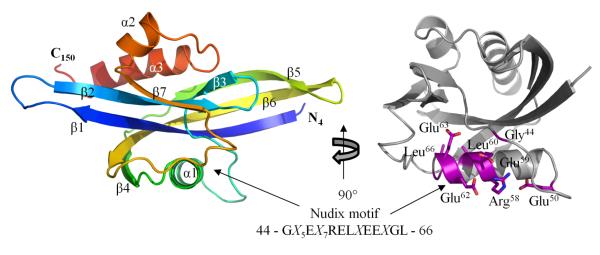

CT771 Crystal Structure

The structure of CT771 was solved by molecular replacement and refined to 2.60 Å (Table 1). CT771 is characterized by an αβα-sandwich fold (Fig. 1) with dimensions approximately 50 × 25 × 30 Å, typical of Nudix family proteins, with 3 α-helices (residues Pro52-Thr64, Phe120-Arg125 and Arg133-Tyr146, respectively) surrounding 7 β-sheets (residues Lys5-Phe18, Ser24-His33, Lys37-Gly40, Gly67-Phe71, Phe76-Asn83, Phe89-Lys102 and Cys113-Leu118, respectively)*. The overall topology of CT771 is β1-β2-β3-β4-α1-β5-β6-β7-α2-α3 (Fig. 1). The conserved Nudix motif (GX5EX7RELXEEXGL, residues 44-66) is found within α1 and the loop regions surrounding this helix (represented as ball-and-sticks and colored magenta in Fig. 1, right panel). The protein interfaces and assemblies (PISA) 35 server was used to assess potential modes of oligomerization. This analysis failed to identify any interfaces that were judged to be thermodynamically favorable, consistent with the monomeric elution profile of CT771 in analytical gel filtration experiments (data not shown).

Figure 1. 2.60 Å Crystal Structure of CT771 from Chlamydia trachomatis.

Crystal structure of CT771 shown in cartoon ribbon format using common rainbow colors (slowly changing from blue N-terminus to red C-terminus). Image is rotated 90° about the vertical axis on the right and amino acids comprising the Nudix motif are highlighted in purple (ball-and-stick), remainder of CT771 structure is colored gray.

Structural Comparison with Ap4A Hydrolases

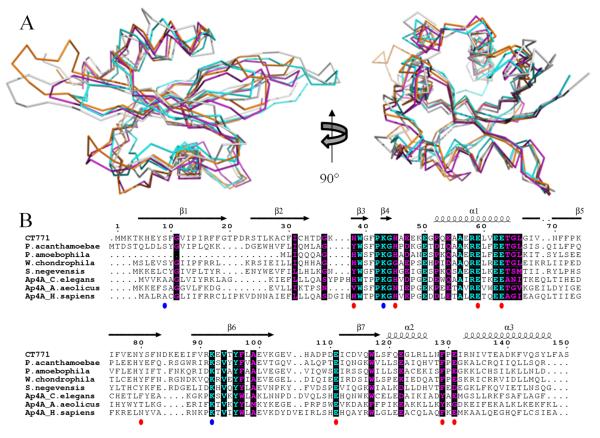

In order to better understand the function of CT771, the refined crystal structure was used to search for structurally-related enzymes within the PDB via the DALI server 36, with the top 5 hits listed in Table 2. Not surprisingly, over 100 of the highest scoring matches are enzymes from the Nudix family. Structures displaying the highest homology to CT771 are diadenosine tetraphosphate (adenosine-P1-P2-P3-P4-adenosine or Ap4A) hydrolases. Furthermore, both mammalian and eubacterial enzymes are found within the top 5 hits, suggesting that they are structurally more alike than previously thought2, 3. Indeed, structural alignment of CT771 and the top 3 DALI hits, Ap4A hydrolases from H. sapiens 8, C. elegans 37 and A. aeolicus 7, (Fig. 2A) further underscores the conserved nature of the αβα-sandwich fold found within this class of enzymes. All 4 structures align with RMSD values better than 2.2 Å, with large-scale variations limited to the loops connecting β1-β2 and β5-β6. Neither of these regions are expected to contribute to substrate binding or catalysis and likely reflect crystallographic differences stabilized by packing.

Table 2.

CT771 DALI Search Statistics

| CT771 Structural Homology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 5 (unique) DALI scores | |||||

| Protein name | PDB code | Z-scorea | RMSD | Cα rangeb | % idc |

| HsAp4A Hydrolase | 3U53 | 18.5 | 2.2 | 134/144 | 31 |

| CeAp4A Hydrolase | 1KTG | 18.4 | 1.8 | 130/137 | 20 |

| AaAp4A Hydrolase | 3I7V | 18.1 | 1.8 | 130/134 | 28 |

| TtAp6A Hydrolase | 1VC8 | 17.3 | 2.2 | 125/126 | 26 |

| B. pseudomallei MutT/Nudix family protein | 1XSB | 16.7 | 2.5 | 138/153 | 30 |

Similarity score representing a function that evaluates the overall level of similarity between two structures. Z-scores higher than 8.0 indicate that the two structures are most likely homologous36.

Denotes the number of residues from the query structure that superimpose within an explicit distance cutoff of an equivalent position in the aligned structure.

Denotes the percent sequence identity across the region of structural homology.

Figure 2. Sequence Conservation of CT771 and Ap4A Hydrolase Members.

A, structural superposition of CT771 (gray) and top 3 structural hits from DALI search (Table II) in ribbon format 36. Structures correspond to Ap4A hydrolases from the following organisms: Homo sapiens (PDB ID: 3U53, orange); Caenorhabditis elegans (PDB ID: 1KTG, purple); Aquifex aeolicus (PDB ID: 3I7V, cyan). B, limited structure-based alignment of CT771 and Ap4A Hydrolase Members was generated using ClustalW30 and rendered with ESPRIPT31. Numbers above the sequences correspond to C. trachomatis CT771. The secondary structure of CT771 is shown above the alignment. Residues are colored according to conservation (cyan = identical and purple = similar) as judged by the BLOSUM62 matrix. Red circles below the sequences correspond to ligand interacting CT771 amino acid side chains in the binary complex, while blue circles correspond to sulfate-bound side chains in the apo-CT771 structure. Sequences used within the alignment are comprised of Ap4A hydrolases with significant structural similarity to CT771 and BLAST-identified orthologs from environmental Chlamydiae. Accession numbers are detailed in Materials and Methods.

Kinetic Characterization of Ap4A Hydrolase Activity of CT771

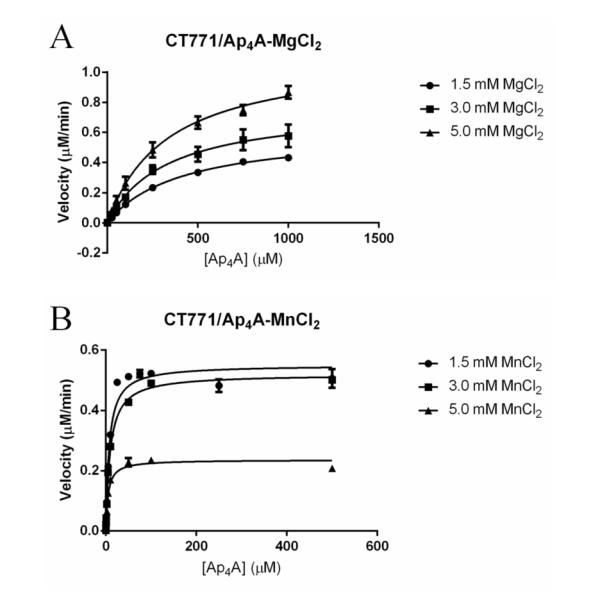

In order to better understand the function of CT771 and provide support for the structural similarities to Ap4A hydrolases revealed by both the DALI search 36 and molecular docking (described in Supporting Information) 29, purified protein was enzymatically characterized using a Luciferase assay as described in the Materials and Methods section. This assay allows the continuous monitoring of cleaved Ap4A via released ATP upon substrate hydrolysis, and has been extensively used to characterize this specific Nudix enzyme class 3, 38. The results of this analysis support the conclusion that CT771 is a bona fide Ap4A hydrolase (Table 4). Intriguingly, the largest observed kinetic activity was in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+ with kcat = 3.2 ± 0.1 (s−1), while the lowest observed binding affinity was in the presence of 5 mM Mn2+ with a Km = 5.0 ± 0.5 μM (Fig. 3). Km measurements assumed that the rate of product formation was slower than enzyme-substrate dissociation. Despite its ability to increase substrate affinity and enzyme efficiency (kcat/Km), increasing concentrations of Mn2+ had an adverse affect on the catalytic rate of CT771 in the presence of Ap4A. These values are in agreement with previously reported values, using a bioluminescent assay, for H. sapiens Ap4A, among others 38.

Figure 3. Affect of Divalent Cations on Ap4A Hydrolysis by CT771.

A, Plot of CT771 activity versus substrate (Ap4A) concentration in the presence of increasing Mg2+ concentration (●, 1.5mM; ∎, 3.0mM; and ▴, 5.0mM). B, Plot of CT771 activity versus substrate (Ap4A) concentration in the presence of increasing Mn2+ concentration (●, 1.5mM; ∎, 3.0mM; and ▴, 5.0mM). Experimental details are defined in Materials and Methods.

Structural Basis for Substrate Recognition of CT771

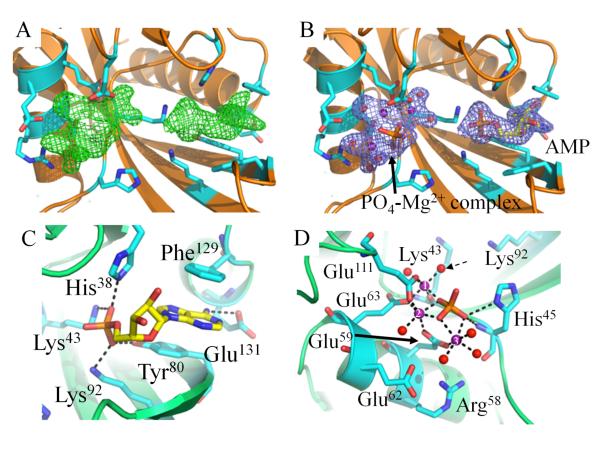

Crystals of CT771 grown in the presence of Ap4A diffracted X-rays to 1.90 Å resolution in the space group C2 (Table 1). Upon modeling and refinement of eight polypeptides in the asymmetric unit, two regions of strong contiguous electron density (visible when contoured up to 5.0 σ) were apparent within each putative active site (Fig. 4A). While the electron density was clearly not large enough to accommodate an entire Ap4A molecule (Fig. 4B), an AMP moiety was modeled near the loop region connecting α2 and α3 (Fig. 4C). This phosphate will be designated the P1-phosphate in further discussions, in accordance with Guranowski et al. 39, as it is proximal to the tighter binding adenosine group within Ap4A. Additionally, a large cluster of electron density was apparent near α1, where a single phosphate, three magnesium ions, and a network of waters were modeled (Fig. 4D). As wild-type CT771 was used in the crystallization experiments with Ap4A, it was not unexpected for the substrate to undergo hydrolysis. Likewise, previous structural studies on C. elegans Ap4A hydrolase 37 with the substrate analog AppCH2ppA yielded nearly the same interpretable regions of electron density as described here (Fig. S3B). The authors speculated that AppCH2ppA had either been catalytically processed by the hydrolase during crystallization or that flexible regions within the substrate (e.g. P2- and P3-phosphates and the second adenosine group) subsequently lacked interpretable electron density. Given the extreme similarities in bound active site ligands between those studies and ours, despite the use of different substrate molecules, we speculate that both compounds have been processed by the crystallized hydrolase in each structure, resulting in a bound AMP molecule and metal-phosphate complex.

Figure 4. Crystal Structure of CT771 Bound to Hydrolyzed Ap4A Product.

A, Fo-Fc map (green mesh at 3.0 σ contour) of the refined structure in the absence of modeled ligands. Active site side chains within hydrogen bonding distance (2.5 – 3.5 Å) of bound ligands are depicted as cylinders (cyan) in all panels. CT771 backbone is depicted in cartoon ribbon format (orange). B, 2Fo-Fc map (blue mesh at 1.0 σ contour) of the refined structure with one AMP and one PO4-Mg2+ complex modeled per subunit. Color scheme is the same as panel A. C, Active site side chains within hydrogen bonding distance (2.5 – 3.5 Å) of AMP (yellow). CT771 backbone is depicted in cartoon ribbon format (lime). D, Active site side chains within hydrogen bonding (2.5 – 3.5 Å) and metal coordination (1.7 – 2.2 Å) distances of PO4-Mg2+ complex. Magnesium ions and water molecules are represented as spheres and colored purple and red, respectively. Dashed arrow identifies proposed nucleophilic water. Magnesium ions are numbered according to Table S1. The phosphate is colored orange. Color scheme is the same as panel C. Further information on the interaction distances within panels C and D can be found in Table S1.

Analysis of the bound AMP molecule within each CT771/AMP-PO4 subunit active site revealed that it resides in a deep groove (~11 Å as measured from the Tyr96 hydroxyl to the N3 atom of the bound AMP molecule) created by the loop regions connecting β2-β3 and β5-β6, as well as the β sheets themselves (Fig. 5). The adenine ring of AMP adopts the anti conformation, where it is stabilized by a hydrogen bond interaction with the carboxylic acid moiety of Glu131 (Fig. 4C). Additional protein contacts with the adenine ring involve an extensive set of π-π stacking interactions created by the aromatic side chains Phe129 and Tyr80. All three side chains are highly conserved across examined Ap4A hydrolases (red circles, Fig. 2B), suggesting a common mechanism of substrate binding and orientation. The ribose sugar hydroxyl groups of the bound AMP molecule adopt the C2′-endo and C3′-exo conformations, and the P1-phosphate is oriented towards the catalytic α1 Nudix helix (Fig. 4C). While the ribose sugar moiety lacks any hydrogen bonding with CT771, the P1-phosphate is stabilized by an extensive network of positively charged side chains (His38, Lys43 and Lys92), along with Tyr80 (Fig. 4C, S1C). As with the adenosine moiety, all four of these residues interacting with the P1-phosphate are highly conserved, with both Lysine residues being invariant (red and blue circles, Fig. 2B). While bond catalysis occurs at the P3-P4-phosphate interface 39, 40, proper orientation of Ap4A clearly begins in this ~11 Å-deep groove.

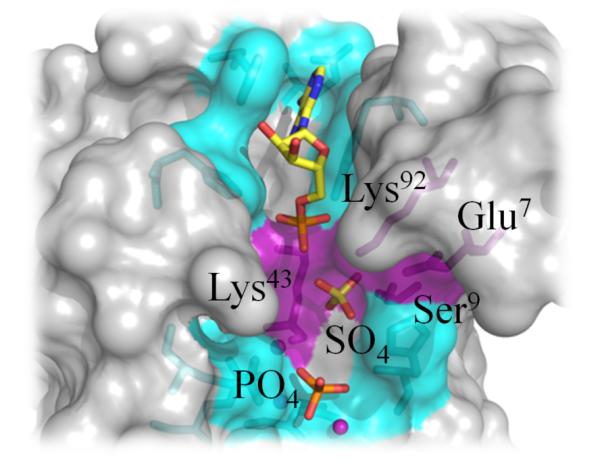

Figure 5. Bound Sulfate Anion in apo-CT771 Structure Highlights P3-Phosphate Position.

Structural superposition of apo- and ligand-bound CT771 (gray, only ligand-bound CT771 surface rendering is represented for clarity). CT771 side chains interacting with AMP (yellow) and the PO4-Mg2+ complex (cyan) or sulfate (purple) are depicted in ball-and-stick format. Residues within appropriate hydrogen bonding distance (2.5 – 3.5 Å) of the sulfate anion are labeled and colored purple.

Consistent with the previously reported Ap4A hydrolase binary complex from C. elegans 37, the region of strong electron density near the catalytic α1 Nudix helix (Fig. 4A) was modeled with a single phosphate anion bound to a network of magnesium ions and waters (Fig. 4B,D). Bailey et al. proposed that this phosphate molecule occupied the P4-phosphate position of Ap4A, primarily due to its proximity to the Nudix helix and distance from the P1-phosphate 37. Thus, all further discussions of this site will refer to it as the P4-phosphate.

Within the CT771/AMP-PO4 structure the P4-phosphate is maintained in a tightly bound position through numerous solvent-ligand contacts and a single direct protein interaction (His45). Solvent-ligand contacts are primarily mediated by three hexacoordinated Mg2+ ions, which themselves form tight metal coordination bonds (average bond length, 2.13 Å) with three Glutamate residues (Glu59, Glu63 and Glu111), 6 water molecules and the aforementioned phosphate (Fig. 4D). A fourth Glutamate residue (Glu62) forms hydrogen bonds with two of the active site waters involved in magnesium hexacoordination. Arg58 appears to stabilize the position of Glu59, which coordinates with two of the three Mg2+ ions. As these residues are found within the Nudix motif, it is unsurprising that they are all highly conserved amongst Ap4A hydrolases (red circles, Fig. 2B). Intriguingly, only three of the oxygens within the P4-phosphate participate in extensive contacts, suggesting the fourth oxygen would likely be linked to the second adenosyl moiety of Ap4A. Thus, as the CT771/AMP-PO4 structure was crystallized in the presence of a high concentration of magnesium (200 mM MgCl2), the active site metals appear to properly maintain the P4-phosphate in a highly specific orientation, priming the substrate for subsequent nucleophilic attack and resulting catalysis at the P3-P4-phosphate bond. While substrates other than Ap4A were not tested for enzymatic activity in the current study, it has previously been reported that this family of enzymes can hydrolyze adenosine polyphosphates with four, five or six phosphates, but not three 3, indicating positioning of the P4-phosphate is critical to substrate catalysis.

Despite efforts to co-crystallize Ap4A with CT771, it appears that the substrate was hydrolyzed prior to data collection, with the product AMP and a magnesium-bound phosphate complex being retained in the final structure. Despite the absence of interpretable electron density for P2- and P3-phosphates in the ligand-bound CT771 structure, comparison with the sulfate anion bound in the apo-CT771 structure (described in Supporting Information) suggests that both Lys43 and Lys92 could hydrogen bond with multiple phosphate oxygen atoms of Ap4A (Fig. 5). In agreement with the ATP-bound A. aeolicus Ap4A hydrolase structure (Fig. S3A), the P2-phosphate of Ap4A would likely not make contacts with CT771. Finally, the second adenosyl binding site, if there is one, remains unoccupied, as seen in all previously reported Ap4A hydrolase binary complexes 7, 8, 37. Analysis of both structures presented herein reveals that a minimal binding module of Np4 is required for CT771 and this family of enzymes 40.

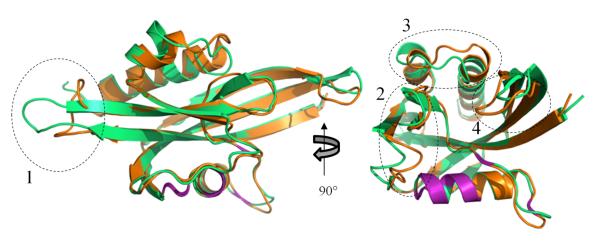

Substrate Induced Structural Changes within CT771

Structural comparison of the apo- and ligand-bound forms of CT771 presents insight into substrate binding and conformational changes required for ligand catalysis. Structural superposition of these two CT771 structures results in the alignment of 140/147 Cα atoms with an RMSD of 1.41 Å (Fig. 6). Notably, the catalytic α1 Nudix helix and surrounding loops are almost identical (highlighted purple in Fig. 6) with only the side chain of Glu63 reorienting to coordinate a magnesium ion in the ligand-bound structure (Fig. 7). While the aforementioned structures are highly similar from a secondary structure perspective, several key loop regions have constricted inward towards the active site. Glu111 directly coordinates two magnesium ions in the ligand-bound structure (shifting ~2.9 Å from its apo-position, (Fig. 7)), as the loop connecting β6 and β7 shifts ~3.0 Å in order to accommodate this interaction (region two in Fig. 6). Additionally within this region, the sidechain of His38 moves ~6.7 Å as it rotates nearly 120° (Fig. 7), where it hydrogen bonds with the P1-phosphate of the bound AMP molecule. Minor conformational changes within this region of CT771 also disrupt an intrachain disulfide bond between Cys32 and Cy113 upon ligand binding (Fig. S5). An extra turn of α3 is formed (region 3 in Fig. 6, residues Pro130 – Arg133) upon ligand binding, which places Phe129 in the appropriate position (shifting ~12.2 Å from its apo-position) to participate in π-π stacking interactions with the adenine ring of AMP (Fig. 4C). The extra turn of α3 facilitates an ~9.3 Å shift of Glu131 away from the active site cleft (Fig. 7), where it hydrogen bonds with the N6 atom of AMP. The loop connecting β5 and β6 shifts ~4.0 Å (region 4 in Fig. 6), however, it does not contact any of the bound ligands. Rather, this shift appears to facilitate bonding interactions involving Tyr80 (shifting ~4.9 Å from its apo-position) on β5 and Lys92 on β6, as these β-sheets subtly bow towards the bound AMP molecule (Fig. 7). Finally, the loop region connecting β1 and β2 has been significantly reordered in the ligand-bound structure (region 1 in Fig. 6); however, this likely arises from protein-protein contacts in crystal packing and does not appear to affect the CT771 active site.

Figure 6. Structural Comparison of CT771 in Bound and Free Forms.

Structural superposition of CT771 in free (orange) and bound (green) forms depicted in cartoon ribbon format. Catalytic Nudix motif is highlighted in purple within both structures. Several regions containing structural differences are highlighted with dashed lines, including: (1) the loop connecting β1 and β2, which likely arises from crystal packing in the bound form; (2) the loop connecting β6 and β7 constricts ~3.0 Å (as measured from the Glu111 Cα for each structure) towards the active site; (3) an extra turn of α3 is formed in the bound structure, resulting in the loop connecting α2 and α3 comprising different residues; and (4) the loop connecting β5 and β6 shifts ~4.0 Å (as measured from the Lys85 Cα for each structure) towards the active site.

Figure 7. CT771 Side Chain Conformational Changes upon Ligand Binding.

Structural superposition of CT771 in free (orange) and bound (green) forms depicted as cylinders. Active site side chains within hydrogen bonding (2.5 – 3.5 Å) and metal coordination (1.7 – 2.2 Å) distances of AMP (yellow) and PO4-Mg2+ complex (ball-and-sticks, purple spheres) are shown. The side chain of Glu111 in the free CT771 structure (orange) was truncated as described in the Materials and Methods section. Arrows indicate conformational changes greater than 2.0 Å, as described in the Results section.

Bioinformatic Analysis of CT771 and Orthologs within Chlamydia

CT771 is conserved across all sequenced members of Chlamydiaceae (sequence identities ranging from 71-99%). However, BLAST analysis of Chlamydiales, members of which include environmental Chlamydiae isolates, reveals the presence of genes orthologous to CT771 (sequence identities ranging from 35-42%) that were not previously clustered with other Chlamydiaceae members (aligned with CT771 in Fig. 2B). It thus appears that the presence of Ap4A hydrolase is required in the basic biology of Chlamydiae. As such we recommend that the annotation of CT771, along with its current orthologs and the ones identified herein, be updated to asymmetric diadenosine tetraphosphatase (nudH).

DISCUSSION

BLAST analysis with the Nudix motif identifies a single target (CT771) within the obligate intracellular human pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. This singular protein is conserved throughout both pathogenic and environmental Chlamydiales (Fig. 2B), suggesting it might play an important role in chlamydial biology. In order to better understand the function of this protein, structural studies were undertaken on CT771 from C. trachomatis, in both apo- and ligand-bound forms. Together, the structural and enzymatic characterization of CT771 suggests that this protein functions as an asymmetric diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) hydrolase, with the likely ability to cleave diadenosine polyphosphates (n≥4). Insights into substrate binding and catalysis have been obtained by efforts to co-crystallize CT771 with Ap4A, with very similar active site electron density occupancy to the previously determined C. elegans Ap4A binary complex 37. Intriguingly, the structure of CT771, only the second Ap4A hydrolase determined from eubacteria, most closely resembles both bacterial and mammalian Ap4A hydrolases, further supporting that these two classes are more closely linked than previously thought.

Both the apo- and ligand-bound CT771 crystal structures contained sulfate/phosphate anions bound near the Nudix motif within the putative active site (Fig. 4, S2). Numerous highly conserved side chains interact with these anions either directly or through coordinated metal ions. Based upon similarities to binary complexes from C. elegans 37 and A. aeolicus 7 Ap4A hydrolases, these anions have been designated P1-, P3- and P4-phosphates; to our knowledge, this is the first description of all 3 contacts within the same protein. While a bound AMP molecule, which represents the first/primary nucleotide binding pocket, was also found within the putative active site, the absence of any appreciable binding contacts for the second adenosine group is consistent with the ability of this subclass of Nudix hydrolases to cleave diadenosine polyphosphates that are linked by four to six phosphates. Given the use of different substrates (AppCH2ppA and Ap4A, respectively), the highly similar ligands bound within the active sites of the C. elegans 37 and CT771 binary complexes are surprising. Despite the fact that Bailey et al. used a theoretically non-hydrolysable Ap4A analog, it appears both compounds were cleaved by the crystallized hydrolases. Additionally, the previously discussed A. aeolicus binary complex 7 also utilized Ap4A, which was also apparently hydrolyzed. However, a bound ATP molecule was modeled by Jeyakanthan et al. in the equivalent position of the AMP molecule within both the C. elegans 37 and CT771 binary complexes. We speculate that this difference in bound ligand arises from the common use (and absence in the A. aeolicus binary complex) of high concentrations of MgCl2 in the crystallization conditions of both the CT771 and C. elegans binary structures that facilitated the presence of a tightly bound Mg2+-phosphate complex.

Comparative analyses of the three phosphate binding sites (and the absence of protein mediated contacts at the putative P2-phosphate site) from both the apo- and ligand-bound CT771 structures presented herein are in agreement with previously determined binary complexes; this supports the role of the Nudix motif in metal binding and proper substrate positioning, prior to catalysis of the P3-P4 phosphate bond. Previous studies have described the asymmetric Ap4A hydrolase reaction mechanism as an “in-line” nucleophilic attack, which is mediated by a conserved glutamate functioning as a catalytic base, coordinating a water molecule and up to 3 magnesium ions 8. Structural and mutagenic studies have suggested that Glu63 (CT771 numbering) is the most likely candidate for the catalytic base; however the absence of structural evidence with an intact substrate has precluded definitive assignment of this residue. Within the CT771/AMP-PO4 structure, three glutamate residues (59, 63 and 111) each coordinate with two of the three magnesium ions (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, Glu63, Glu111, and the Lys43 carbonyl coordinate with a common magnesium ion (identified as 1 in Fig. 4D) that is bound to a water molecule in an appropriate position to function as a nucleophile within the phosphoryl-binding groove of CT771 (denoted by a dashed arrow in Fig. 4D).

Enzymatic characterization of CT771 was facilitated by monitoring hydrolyzed Ap4A via released ATP and cognate luciferase activity. Unfortunately, this method precluded the analysis of substrates other than Ap4A due to an absence of released ATP. However, both in silico docking and crystallographic studies on CT771 support a preference for Ap4A as a true substrate. Furthermore, enzymatic analyses did confirm Ap4A hydrolase activity for CT771 and reveal an intriguing inverse relationship between concentration and the preferred divalent cation. While the majority of Ap4A hydrolases preferentially utilize Mg2+ 41, instances of maximal activity in the presence of Mn2+ have been previously documented 42. Furthermore, in the presence of Mn2+ the Km value for Ap4A was roughly two orders of magnitude tighter than in the presence of Mg2+ for CT771, yet increasing concentrations of Mn2+ resulted in a decreased catalytic rate and efficiency (Table 4). The results presented by Szurmak et al. are in agreement with those reported here, particularly with respect to increasing catalytic rate in the presence of decreasing Mn2+ and increasing Mg2+ cations. It is difficult to speculate what physiological role this difference in metal ion affinity would serve within Chlamydia, but it could be a reflection of the intracellular environment where the chlamydial developmental cycle occurs.

Chlamydia species are obligate intracellular pathogens that typically rely on the infected host cell for the majority of their energetic needs. Thus, intracellular energy storage pools must be closely monitored in order to prevent the accumulation of toxic byproducts, or alarmones, which could potentially shutdown protein synthesis 43. One such alarmone is Ap4A, which is typically generated when aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases charge their cognate tRNA molecule 10. The chlamydial inclusion is not passively permeable to small molecules ≥520 Da 44, indicating that Ap4A (~800 Da) may not be freely diffusible and would need to be processed within the inclusion, providing a clear role for CT771 throughout the developmental cycle. Substrate multispecificity has been documented within a variety of Nudix hydrolase family members 9 and of particular note with respect to CT771, bacterial Ap4A hydrolases have been demonstrated to efficiently remove the 5′ termini of mRNA, suggesting a role in translation regulation 45. Clearly, further studies exploring alternative substrate preferences and specificities are needed, but at this time it appears that CT771 functions as a housekeeping gene, preventing Ap4A levels from rising during periods of high metabolic activity. In support of this role, quantifiable levels of CT771 protein are detected in EBs 46, indicating the organism is primed to handle a rapid burst of nascent transcription (~1-2 hpi) 47 and a potential build-up of Ap4A through tRNA charging during translation, upon infecting and entering the host cell.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank John Karanicolas and Jimmy Budiardjo for technical assistance with the Luciferase assay.

FUNDING SOURCE STATEMENT Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contact No. DE-AC02-06CH11357, and use of the IMCA-CAT beamline 17-ID by the companies of the Industrial Macromolecular Crystallography Association through a contract with the Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute. Use of the KU COBRE-PSF Protein Structure Laboratory was supported by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR017708-10) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P20 GM103420-10) from the National Institutes of Health. PSH, MLB and ANH were supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant AI079083.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Ap4A

diadenosine 5′,5′″-P1,P4-tetraphosphate

- Nudix

nucleoside diphosphates linked to any other moiety X

- IPTG

isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- TEV

tobacco etch virus

- PISA

protein interfaces and assemblies server

Footnotes

Numbering of all residues in this work reflects their position in the C. trachomatis CT771 sequence.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4ILQ and 4MPO) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

SUPPORTING INFORMATION Molecular Docking of CT771 with Nudix Substrates, Bound Sulfate in Apo-CT771 Structure and Structural Superposition of Each Chain Within Ligand-Bound CT771 Results sections. Electrostatic surface potential of free and bound CT771 structures (Fig. S1). Interactions Between CT771 and a Bound Sulfate Anion (Figure S2). Structural comparison of bound CT771 and other Ap4A hydrolase complexes (Figure S3). Structural superposition of each chain within ligand-bound CT771 (Figure S4). Disruption of intrachain disulfide bond upon substrate binding (Figure S5). Bonding distances between CT771 and bound ligands (Table S1). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.McLennan AG. The Nudix hydrolase superfamily. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2006;63:123–143. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5386-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn CA, O’Handley SF, Frick DN, Bessman MJ. Studies on the ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase subfamily of the nudix hydrolases and tentative identification of trgB, a gene associated with tellurite resistance. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32318–32324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdelghany HM, Gasmi L, Cartwright JL, Bailey S, Rafferty JB, McLennan AG. Cloning, characterisation and crystallisation of a diadenosine 5′,5″′-P(1),P(4)-tetraphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase from Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1550:27–36. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swarbrick JD, Bashtannyk T, Maksel D, Zhang XR, Blackburn GM, Gayler KR, Gooley PR. The three-dimensional structure of the Nudix enzyme diadenosine tetraphosphate hydrolase from Lupinus angustifolius L. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:1165–1177. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maksel D, Gooley PR, Swarbrick JD, Guranowski A, Gange C, Blackburn GM, Gayler KR. Characterization of active-site residues in diadenosine tetraphosphate hydrolase from Lupinus angustifolius. Biochem J. 2001;357:399–405. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conyers GB, Wu G, Bessman MJ, Mildvan AS. Metal requirements of a diadenosine pyrophosphatase from Bartonella bacilliformis: magnetic resonance and kinetic studies of the role of Mn2+ Biochemistry. 2000;39:2347–2354. doi: 10.1021/bi992458n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeyakanthan J, Kanaujia SP, Nishida Y, Nakagawa N, Praveen S, Shinkai A, Kuramitsu S, Yokoyama S, Sekar K. Free and ATP-bound structures of Ap4A hydrolase from Aquifex aeolicus V5. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:116–124. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swarbrick JD, Buyya S, Gunawardana D, Gayler KR, McLennan AG, Gooley PR. Structure and substrate-binding mechanism of human Ap4A hydrolase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8471–8481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLennan AG. Substrate ambiguity among the nudix hydrolases: biologically significant, evolutionary remnant, or both? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:373–385. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goerlich O, Foeckler R, Holler E. Mechanism of synthesis of adenosine(5′)tetraphospho(5′)adenosine (AppppA) by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Eur J Biochem. 1982;126:135–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vartanian A, Prudovsky I, Suzuki H, Dal Pra I, Kisselev L. Opposite effects of cell differentiation and apoptosis on Ap3A/Ap4A ratio in human cell cultures. FEBS Lett. 1997;415:160–162. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLennan AG. Dinucleoside polyphosphates-friend or foe? Pharmacol Ther. 2000;87:73–89. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ismail TM, Hart CA, McLennan AG. Regulation of dinucleoside polyphosphate pools by the YgdP and ApaH hydrolases is essential for the ability of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium to invade cultured mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32602–32607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdelrahman YM, Belland RJ. The chlamydial developmental cycle. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov RL, Zhao Q, Koonin EV, Davis RW. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephens RS. Chlamydia: Intracellular Biology, Pathogenesis, and Immunity. American Society for Microbiology. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin H, Hu J, Hua Y, Challa SV, Cross TA, Gao FP. Construction of a series of vectors for high throughput cloning and expression screening of membrane proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Biotechnol. 2008;8:51. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geisbrecht B, Bouyain S, Pop M. An optimized system for expression and purification of secreted bacterial proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;46:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans PR. An introduction to data reduction: space-group determination, scaling and intensity statistics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:282–292. doi: 10.1107/S090744491003982X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long F, Vagin AA, Young P, Murshudov GN. BALBES: a molecular-replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2008;64:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907050172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews BW. Solvent content of protein crystals. Journal of molecular biology. 1968;33:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams P, Grosse-Kunstleve R, Hung L, Ioerger T, McCoy A, Moriarty N, Read R, Sacchettini J, Sauter N, Terwilliger T. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schüttelkopf AW, van Aalten DM. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson J, Higgins D, Gibson T. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart D, Métoz F. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zemla A. LGA: A method for finding 3D similarities in protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3370–3374. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernstein FC, Koetzle TF, Williams GJ, Meyer EF, Brice MD, Rodgers JR, Kennard O, Shimanouchi T, Tasumi M. The Protein Data Bank. A computer-based archival file for macromolecular structures. Eur J Biochem. 1977;80:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 2002 2009, http://www.pymol.org.

- 35.Rocchia W, Sridharan S, Nicholls A, Alexov E, Chiabrera A, Honig B. Rapid grid-based construction of the molecular surface and the use of induced surface charge to calculate reaction field energies: applications to the molecular systems and geometric objects. J Comput Chem. 2002;23:128–137. doi: 10.1002/jcc.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holm L, Rosenström P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey S, Sedelnikova SE, Blackburn GM, Abdelghany HM, Baker PJ, McLennan AG, Rafferty JB. The crystal structure of diadenosine tetraphosphate hydrolase from Caenorhabditis elegans in free and binary complex forms. Structure. 2002;10:589–600. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00746-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdelghany HM, Bailey S, Blackburn GM, Rafferty JB, McLennan AG. Analysis of the catalytic and binding residues of the diadenosine tetraphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase from Caenorhabditis elegans by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4435–4439. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guranowski A, Brown P, Ashton PA, Blackburn GM. Regiospecificity of the hydrolysis of diadenosine polyphosphates catalyzed by three specific pyrophosphohydrolases. Biochemistry. 1994;33:235–240. doi: 10.1021/bi00167a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLennan AG, Prescott M, Evershed RP. Identification of point of specific enzymic cleavage of P1,P4-bis(5′-adenosyl) tetraphosphate by negative ion FAB mass spectrometry. Biomedical & environmental mass spectrometry. 1989;18:450–452. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200180615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guranowski A. Specific and nonspecific enzymes involved in the catabolism of mononucleoside and dinucleoside polyphosphates. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;87:117–139. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szurmak B, Wysłouch-Cieszyńska A, Wszelaka-Rylik M, Bal W, Dobrzańska M. A diadenosine 5′,5″-P1P4 tetraphosphate (Ap4A) hydrolase from Arabidopsis thaliana that is activated preferentially by Mn2+ ions. Acta Biochim Pol. 2008;55:151–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pietrowska-Borek M, Nuc K, Zielezińska M, Guranowski A. Diadenosine polyphosphates (Ap3A and Ap4A) behave as alarmones triggering the synthesis of enzymes of the phenylpropanoid pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Open Bio. 2011;1:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinzen RA, Hackstadt T. The Chlamydia trachomatis parasitophorous vacuolar membrane is not passively permeable to low-molecular-weight compounds. Infection and immunity. 1997;65:1088–1094. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.1088-1094.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richards J, Liu Q, Pellegrini O, Celesnik H, Yao S, Bechhofer DH, Condon C, Belasco JG. An RNA pyrophosphohydrolase triggers 5′-exonucleolytic degradation of mRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Molecular cell. 2011;43:940–949. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saka HA, Thompson JW, Chen YS, Kumar Y, Dubois LG, Moseley MA, Valdivia RH. Quantitative proteomics reveals metabolic and pathogenic properties of Chlamydia trachomatis developmental forms. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82:1185–1203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wichlan DG, Hatch TP. Identification of an early-stage gene of Chlamydia psittaci 6BC. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2936–2942. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2936-2942.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diederichs K, Karplus PA. Improved R-factors for diffraction data analysis in macromolecular crystallography. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:269–275. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiss MS. Global indicators of X-ray data quality. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2001;34:130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karplus PA, Diederichs K. Linking crystallographic model and data quality. Science. 2012;336:1030–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1218231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans P. Biochemistry. Resolving some old problems in protein crystallography. Science. 2012;336:986–987. doi: 10.1126/science.1222162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.