Significance

The heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria represent a true multicellular system found in the bacterial world that adds unique features to biodiversity. They grow as chains of cells containing two metabolically interdependent cellular types, the vegetative cells that fix carbon dioxide performing oxygenic photosynthesis and the dinitrogen-fixing heterocysts. Heterocysts accumulate a cell inclusion, cyanophycin [multi-L-arginyl-poly (L-aspartic acid)], as a nitrogen reservoir. We have found that the second enzyme of cyanophycin catabolism, isoaspartyl dipeptidase, is present at significantly higher levels in vegetative cells than in heterocysts, identifying the nitrogen-rich dipeptide β-aspartyl-arginine as a nitrogen vehicle to the vegetative cells and showing that compartmentalization of a catabolic route is used to improve the physiology of nitrogen fixation.

Keywords: intercellular communication, nitrogen fixation

Abstract

Heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria are multicellular organisms in which growth requires the activity of two metabolically interdependent cell types, the vegetative cells that perform oxygenic photosynthesis and the dinitrogen-fixing heterocysts. Vegetative cells provide the heterocysts with reduced carbon, and heterocysts provide the vegetative cells with fixed nitrogen. Heterocysts conspicuously accumulate polar granules made of cyanophycin [multi-L-arginyl-poly (L-aspartic acid)], which is synthesized by cyanophycin synthetase and degraded by the concerted action of cyanophycinase (that releases β-aspartyl-arginine) and isoaspartyl dipeptidase (that produces aspartate and arginine). Cyanophycin synthetase and cyanophycinase are present at high levels in the heterocysts. Here we created a deletion mutant of gene all3922 encoding isoaspartyl dipeptidase in the model heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. The mutant accumulated cyanophycin and β-aspartyl-arginine, and was impaired specifically in diazotrophic growth. Analysis of an Anabaena strain bearing an All3922-GFP (green fluorescent protein) fusion and determination of the enzyme activity in specific cell types showed that isoaspartyl dipeptidase is present at significantly lower levels in heterocysts than in vegetative cells. Consistently, isolated heterocysts released substantial amounts of β-aspartyl-arginine. These observations imply that β-aspartyl-arginine produced from cyanophycin in the heterocysts is transferred intercellularly to be hydrolyzed, producing aspartate and arginine in the vegetative cells. Our results showing compartmentalized metabolism of cyanophycin identify the nitrogen-rich molecule β-aspartyl-arginine as a nitrogen vehicle in the unique multicellular system represented by the heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria.

Heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria represent a unique group of multicellular bacteria in which growth requires the activity of two interdependent cell types: the vegetative cells that perform oxygenic photosynthesis and the N2-fixing heterocysts (1, 2). Vegetative cells fix CO2 photosynthetically and transfer reduced carbon to heterocysts (3), in which nitrogenase fixes N2 producing ammonia that is incorporated into amino acids via the glutamine synthetase−glutamate synthase (GS/GOGAT) pathway (4). Heterocysts transfer fixed N to the vegetative cells in the filament (5). In a cyanobacterium such as the model organism Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 (hereafter Anabaena), the filament can be hundreds of cells long. Under nitrogen fixing conditions, which are established when no combined nitrogen is available in the medium (1, 2), about one in 10–20 cells are heterocysts, which are semiregularly distributed along the filament ensuring an even exchange of nutrients between the two cell types. A full understanding of this multicellular system needs the identity of the intercellularly exchanged compounds to be known.

Because the heterocysts bear high levels of glutamine synthetase but lack glutamate synthase (6, 7), an exchange of glutamine (transferred from heterocysts to vegetative cells) for glutamate (transferred from vegetative cells to heterocysts) has been proposed for the GS/GOGAT cycle to work in the diazotrophic cyanobacterial filament (4, 6). Indeed, when incubated under proper conditions, isolated heterocysts can produce glutamine that is released to the surrounding medium (6). In addition to glutamate, two compounds that can be transferred from vegetative cells to heterocysts are alanine and sucrose (8). Alanine can be an immediate source of reducing power in the heterocyst, where it is metabolized by catabolic alanine dehydrogenase, the product of ald (9). Sucrose, a universal vehicle of reduced carbon in plants, appears to have a similar role within the diazotrophic cyanobacterial filament, because diazotrophic growth requires that sucrose is produced in vegetative cells and hydrolyzed by a specific invertase, InvB, in the heterocysts (10–13). Sucrose is a more important carbon vehicle to heterocysts than alanine, because inactivation of invB (12, 13) has a stronger negative effect on diazotrophic growth than inactivation of ald (9). In summary, there is evidence for transfer of sucrose, glutamate, and alanine from vegetative cells to heterocysts and of glutamine in the reverse direction.

Heterocysts bear inclusions in the form of refractile granules that are located at the cells poles (close to the heterocyst “necks”) and are made of cyanophycin [multi-L-arginyl-poly (L-aspartic acid)], a nitrogen-rich polymer (14, 15). Although production of cyanophycin is not required for diazotrophic growth (16, 17), its conspicuous presence in the heterocysts suggests a possible role of this cell inclusion in diazotrophy (18, 19), for instance as a nitrogen buffer to balance nitrogen accumulation and transfer (20). Cyanophycin is synthesized by cyanophycin synthetase that adds both aspartate to the aspartate backbone of the polymer and arginine to the β-carboxyl group of aspartate residues in the backbone (21, 22). Cyanophycin is degraded by cyanophycinase that releases a dipeptide, β-aspartyl-arginine (23), which is hydrolyzed to aspartate and arginine by an isoaspartyl dipeptidase homologous to plant-type asparaginases (24). Cyanophycin synthetase is the product of cphA (21) and cyanophycinase of cphB (23). Anabaena bears two gene clusters, cph1 and cph2, each containing both cphA and cphB genes, of which cph1 contributes most to cyanophycin metabolism (17). All these genes are expressed in vegetative cells and heterocysts, but differential expression leads to levels of both cyanophycin synthetase and cyanophycinase that are much higher (about 30- and 90-fold, respectively) in heterocysts than in vegetative cells (25). The fate of the β-aspartyl-arginine released in the cyanophycinase reaction has, however, not been investigated until now.

As deduced from heterologous expression in Escherichia coli, ORF all3922 of the Anabaena chromosome encodes an isoaspartyl dipeptidase (24). In this work, we have generated Anabaena mutants of all3922, including inactivation and reporter-expressing strains, and have found that all3922 is required for optimal diazotrophic growth and that isoaspartyl dipeptidase is present mainly in the vegetative cells of the diazotrophic filament. Our results imply that a substantial fraction of the β-aspartyl-arginine dipeptide produced in the heterocysts is hydrolyzed in the vegetative cells and, thus, that this peptide is an intercellularly transferred nitrogen vehicle in the diazotrophic filament.

Results

Isolation and Characterization of an all3922 Mutant.

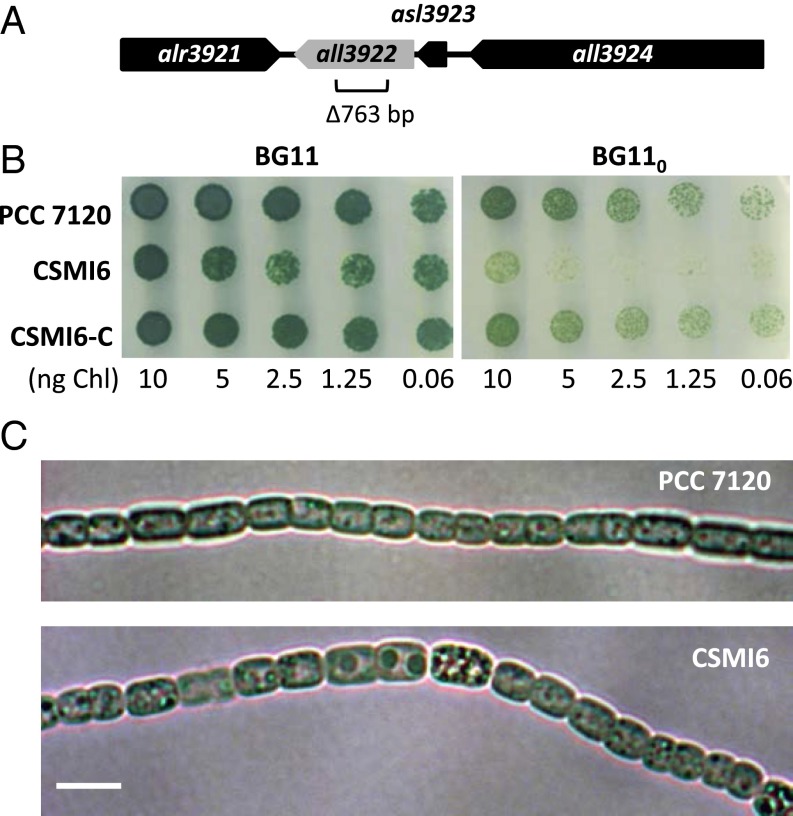

To create an Anabaena mutant of all3922, a 763-bp fragment internal to the gene was deleted (Fig. 1A) without leaving any gene marker behind to avoid polar effects on neighboring genes (Fig. S1). Several clones bearing this deletion were obtained that were homozygous for the mutant chromosomes (Fig. S1). Strain CSMI6, which was selected for further analysis, exhibited weak growth under diazotrophic conditions on solid medium, although it grew well in the presence of combined nitrogen, either nitrate or ammonium (shown in Fig. 1B for nitrate-supplemented medium). Complementation of CSMI6 with a plasmid bearing wild-type all3922 (see SI Materials and Methods) allowed diazotrophic growth corroborating that growth impairment resulted from the all3922 mutation (see strain CSMI6-C in Fig. 1B). Determination of growth rate constants in liquid culture showed that the growth rate of CSMI6 in the presence of combined nitrogen (nitrate or ammonium) was comparable to that of the wild type, but it was about 46% slower in the absence of combined nitrogen (Table 1). Nitrogenase activity, measured by the acetylene reduction assay, was only 15% lower in the mutant than in the wild type (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of an Anabaena all3922 mutant. (A) Schematic of the all3922 genomic region in Anabaena with indication of the DNA fragment removed to create strain CSMI6. (B) Growth tests in solid medium using nitrate (BG11) or N2 (BG110) as the nitrogen source. Each spot was inoculated with an amount of cells containing the indicated amount of Chl, and the plates were incubated under culture conditions for 11 d and photographed. (C) Filaments of Anabaena sp. strains PCC 7120 and CSMI6 from cultures incubated for 4 d in BG11 medium and visualized by light microscopy. (Scale bar, 5 μm.)

Table 1.

Growth rate constants, nitrogenase activity, and cyanophycin granule polypeptide (CGP) levels in Anabaena sp. strains PCC 7120 (wild type) and CSMI6 (all3922)

| Strain | Growth rate, μ, day−1 |

Nitrogenase activity, μmol (mg Chl)-1 h−1 | CGP, μg arginine (mg Chl)-1 |

||||

| NH4+ | NO3− | N2 | NH4+ | NO3− | N2 | ||

| PCC 7120 | 0.55 ± 0.08 (4) | 0.79 ± 0.12 (8) | 0.67 ± 0.22 (9) | 16.52 ± 4.27 (6) | 166.52 ± 34.64 (3) | 160.06 ± 24.02 (3) | 166.66 ± 53.88 (3) |

| CSMI6 | 0.58 ± 0.14 (3) | 0.77 ± 0.17 (4) | 0.36 ± 0.12 (3) | 13.97 ± 3.16 (5) | 465.05 ± 97.85 (3) | 366.94 ± 22.19 (3) | 248.01 ± 40.74 (3) |

| CSMI6 vs. PCC 7120 | P = 0.80 | P = 0.83 | P = 0.053* | P = 0.34 | P = 0.015* | P = 0.001* | P = 0.164 |

The growth rate constant (μ) was determined in photoautotrophic shaken cultures with the indicated nitrogen sources. To determine nitrogenase activity, filaments grown in BG110NH4+ medium and incubated in nitrogen-free BG110 medium for 48 h were used in assays of reduction of acetylene to ethylene under oxic conditions. Cyanophycin was determined by the Sakaguchi reaction for arginine on CGP granules isolated from ammonium-grown filaments incubated for 24 h in media with the indicated nitrogen sources. Figures are the mean and SD of data from the number of independent experiments indicated in parentheses. The significance of the differences between the mutant and the wild-type figures was assessed by the Student's t test (P indicated in each case); asterisks denote likely significant differences. In strain CSMI6, the amount of CGP was significantly different (P = 0.044) in the cultures incubated in the absence of combined nitrogen compared with the cultures kept in the presence of ammonium.

Microscopic observation of strain CSMI6 showed the presence of abundant granulation in the cytoplasm of the cells (Fig. 1C). To test the possibility that the granulation corresponded to cyanophycin, cyanophycin granule polypeptide (CGP) isolation was carried out and the isolated material was measured with the Sakaguchi reaction for arginine. CSMI6 cells grown for 8 d in the presence of nitrate had about ninefold the amount of CGP present in the control wild-type cells [1365.24 ± 483.91 and 147.06 ± 6.62 μg arginine (mg Chl)-1, respectively; mean and SD (n = 3)]. An experiment of accumulation and degradation of cyanophycin was then performed. Cells grown in three successive batch cultures with ammonium were incubated for 24 h in medium with ammonium, with nitrate, or lacking combined nitrogen and then used for determination of CGP. In the presence of ammonium, cells of the mutant had about 2.8 times the CGP detected in the wild-type cells (Table 1). However, whereas the wild type contained similar levels of CGP under the three conditions, CSMI6 cells contained less amounts of CGP after incubation with nitrate or, especially, in the absence of combined nitrogen than in the presence of ammonium (Table 1). These results showed that the CGP present in the ammonium-grown CSMI6 cells was degraded to some extent upon incubation for 24 h in media with nitrate or without combined nitrogen. Because strain CSMI6 was expected to be impaired in hydrolysis of the β-aspartyl-arginine produced in cyanophycin degradation, we asked whether the dipeptide could be detected in the filaments of this strain.

Detection of β-Aspartyl-arginine.

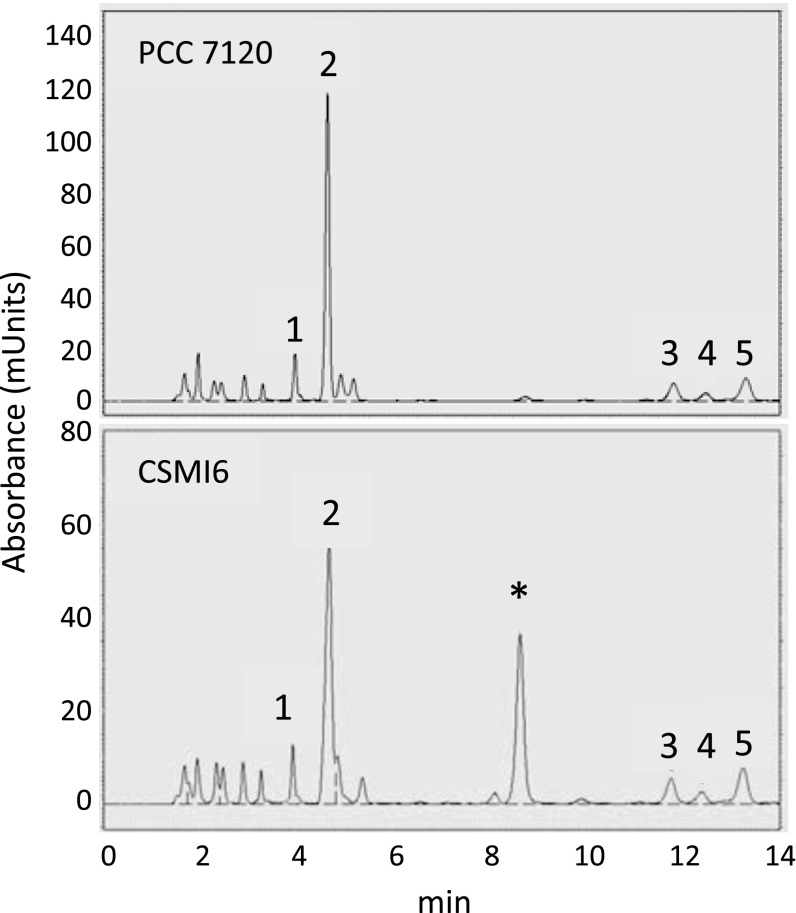

Because β-aspartyl-arginine has an amino group that can be derivatized with phenylisothiocyanate, we subjected cell-free extracts from filaments incubated under different conditions to standard HPLC analysis of amino acids. A compound not found (or observed at very low levels; see below) in wild-type extracts was observed in the region of the chromatogram between glutamate and serine in extracts from strain CSMI6 (Fig. 2). Cochromatography with authentic β-aspartyl-arginine identified that compound as the β-aspartyl-arginine dipeptide (Fig. S2). The amount of β-aspartyl-arginine detected in CSMI6 extracts ranged from 5 to 25 µmol (mg Chl)-1 under different conditions, and it was generally higher than the levels of the two most abundant amino acids detected, glutamate [2–18 µmol (mg Chl)-1] and alanine [1.25–9 µmol (mg Chl)-1].

Fig. 2.

Accumulation of β-aspartyl-arginine in Anabaena sp. strain CSMI6. Chromatographs of cell-free extracts from strains PCC 7120 (Upper) and CSMI6 (Lower) grown on ammonium and incubated for 24 h in BG110 medium (lacking combined nitrogen) are shown. Peaks corresponding to aspartate (1), glutamate (2), serine (3), asparagine (4), and glycine (5) are indicated. The peak marked with an asterisk (*) corresponds to β-aspartyl-arginine (see Fig. S2) and represents 25.38 µmol (mg Chl)-1 in the cell-free extract.

The dipeptide could also be detected after extraction of the cells with 0.1 M HCl or by boiling (Table S1). The levels of β-aspartyl-arginine found in filaments that had been incubated without combined nitrogen for 48 h were about 4.2 µmol (mg Chl)-1 in strain CSMI6 and 0.035 µmol (mg Chl)-1 in the wild-type strain. This indicates that the dipeptide is indeed produced in the wild type, but its cellular levels are kept very low by the action of the All3922 dipeptidase. To check whether some of the dipeptide accumulated in the filaments of strain CSMI6 leaked out to the extracellular medium, the supernatant from a culture incubated for 48 h in the absence of combined nitrogen was analyzed and found to contain 0.108 µmol β-aspartyl-arginine (mg Chl)-1, indicating that only a limited leakage takes place.

Cell-Specific Expression of All3922.

To investigate the expression and cell localization of All3922, an all3922-sf-gfp fusion gene [sf-gfp encodes a superfolder green fluorescent protein (26)] was constructed and transferred to Anabaena (Fig. S3). Anabaena clones bearing this construct as the only all3922 gene were readily isolated (Fig. S3). Strain CSMI27, which was selected for further analysis, exhibited growth properties similar to those of the wild type (Fig. S3), indicating that the All3922-sf-GFP fusion protein retained All3922 function. The mature isoaspartyl dipeptidase is a tetramer of two subunits (α and β) produced, both isolated from diazotrophic filaments by cleavage of the primary gene product (24). In the mature protein, the sf-GFP is bound to the β subunit, and no substantial release of the sf-GFP from the fusion polypeptide was observed (Fig. S4).

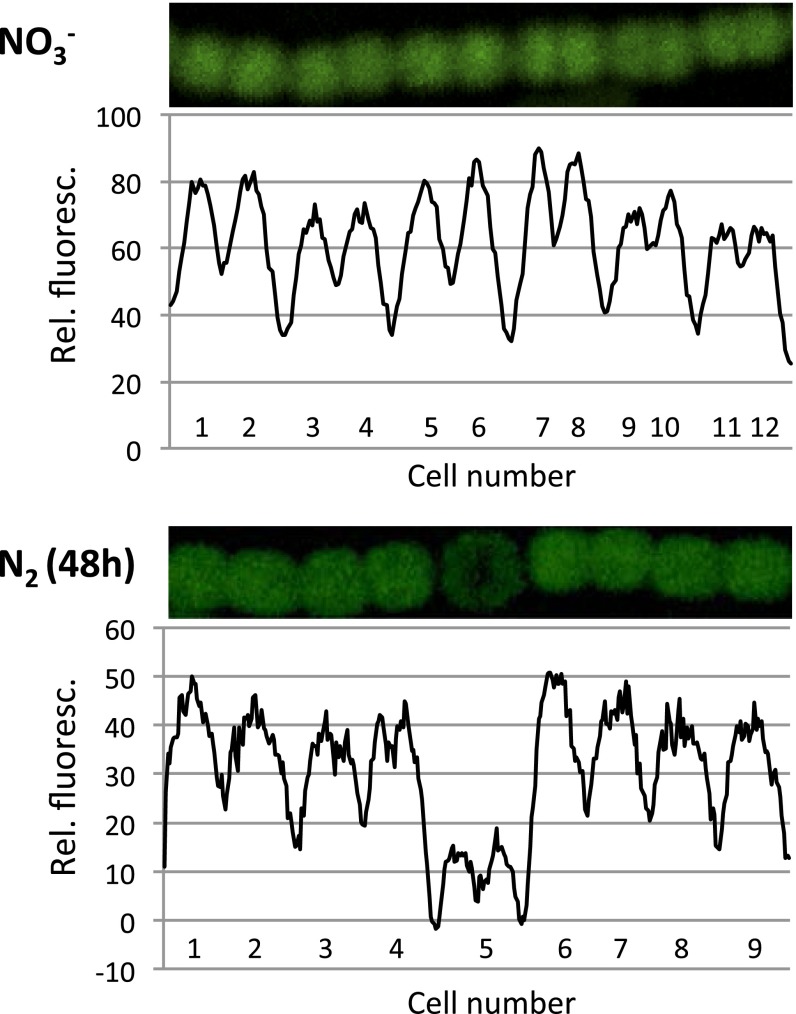

When strain CSMI27 was grown with nitrate, GFP fluorescence was observed in all of the cells of the filament, but when grown diazotrophically, GFP fluorescence was observed in vegetative cells but not (or much less) in heterocysts (Fig. 3). Quantification of GFP fluorescence along the filaments confirmed the visual impression of low sf-GFP fluorescence in the heterocysts (Fig. 3). Quantification of the GFP fluorescence in a large number of cells indicated that, in filaments incubated for 24 h without combined nitrogen, heterocysts had on average 19.7% of the fluorescence detected in vegetative cells (630 vegetative cells and 108 heterocysts counted; Student's t test P = 6 × 10−114). In filaments incubated for 48 h without combined nitrogen, heterocysts had on average 11.2% of the fluorescence detected in vegetative cells (662 vegetative cells and 65 heterocysts counted; P = 5 × 10−99). These results suggest that All3922 is lost from heterocysts as they age.

Fig. 3.

All3922 is expressed mainly in vegetative cells. Filaments of strain CSMI27 (all3922-sf-gfp) grown with nitrate (Upper) or incubated for 48 h in medium lacking combined nitrogen (Lower) visualized by confocal microscopy and quantification of sf-GFP fluorescence from each cell along the filaments. Average background fluorescence from wild-type cells (lacking the sf-GFP) was subtracted. Cell number 5 in the Lower panel is a heterocyst. Rel. fluoresc., relative fluorescence.

Isoaspartyl dipeptidase can use a number of substrates other than β-aspartyl-arginine (24). To determine its activity in cell-free extracts, we used β-aspartyl-lysine as a convenient, commercially available substrate (Fig. S5). Levels of isoaspartyl dipeptidase activity were similar in extracts of Anabaena filaments grown in the presence and absence of combined nitrogen, but the activity was undetectable in extracts from mutant CSMI6 (Table 2). Heterocysts can be isolated from diazotrophic filaments with a protocol based on treatment with lysozyme to disrupt vegetative cells by mild mechanical treatments (27, 28). We then assessed isoaspartyl dipeptidase in extracts of vegetative cells and heterocysts, both isolated from diazotrophic filaments. Isoaspartyl dipeptidase levels in extracts of vegetative cells were similar to (just somewhat higher than) those of whole filaments, but they were about fivefold lower in heterocyst extracts than in vegetative cell extracts (Table 2). To assess that heterocyst extracts had been isolated properly, we determined glutamine synthetase that is known to be present at high levels in the heterocysts (6, 29). In contrast to isoaspartyl dipeptidase, glutamine synthetase levels were threefold higher in heterocyst extracts than in vegetative cell extracts (Table 2). Our results indicate that isoaspartyl dipeptidase accumulates at appreciable levels in both nitrate-grown and diazotrophic filaments, but in the latter, it is distributed differentially between the two cell types, being preferentially accumulated in vegetative cells.

Table 2.

Isoaspartyl dipeptidase and glutamine synthetase activities in cell-free extracts of Anabaena sp. strains PCC 7120 (WT) and CSMI6

| Sample | Isoaspartyl dipeptidase, nmol (mg Chl)-1 min−1 | Glutamine synthetase, µmol (mg Chl)-1 min−1 |

| WT, Fil, BG11 | 23.94 | 18.96 |

| WT, Fil, BG110 | 22.53 | 21.54 |

| WT, Vgt | 26.81 | 22.45 |

| WT, Het (n = 3) | 4.82 ± 0.46 | 61.37 ± 2.75 |

| CSMI6, Fil, BG11 | nd | 23.18 |

| CSMI6, Fil, BG110 | nd | 22.36 |

| CSMI6, Het | nd | 61.33 |

Isoaspartyl dipeptidase was assayed using β-aspartyl-lysine as a substrate in cell-free extracts of whole filaments grown in bubbled BG11 or BG110 medium or of vegetative cells or heterocysts isolated from filaments grown in bubbled BG110 medium; figures refer to dipeptide hydrolyzed in the reaction. Glutamine synthetase was determined in the same cell-free extracts by the transferase assay; figures are γ-glutamyl-hydroxamate produced in the reaction. Data for wild-type heterocysts are the mean and SD of the values obtained with three independent heterocyst preparations. Note that the Het values for isoaspartyl dipeptidase are likely an overestimation, because the presence of some contamination of vegetative cell extracts in the heterocyst extracts is unavoidable. Fil, extracts from whole filaments; Het, extracts from heterocysts; nd, not detected; Vgt, extracts from vegetative cells.

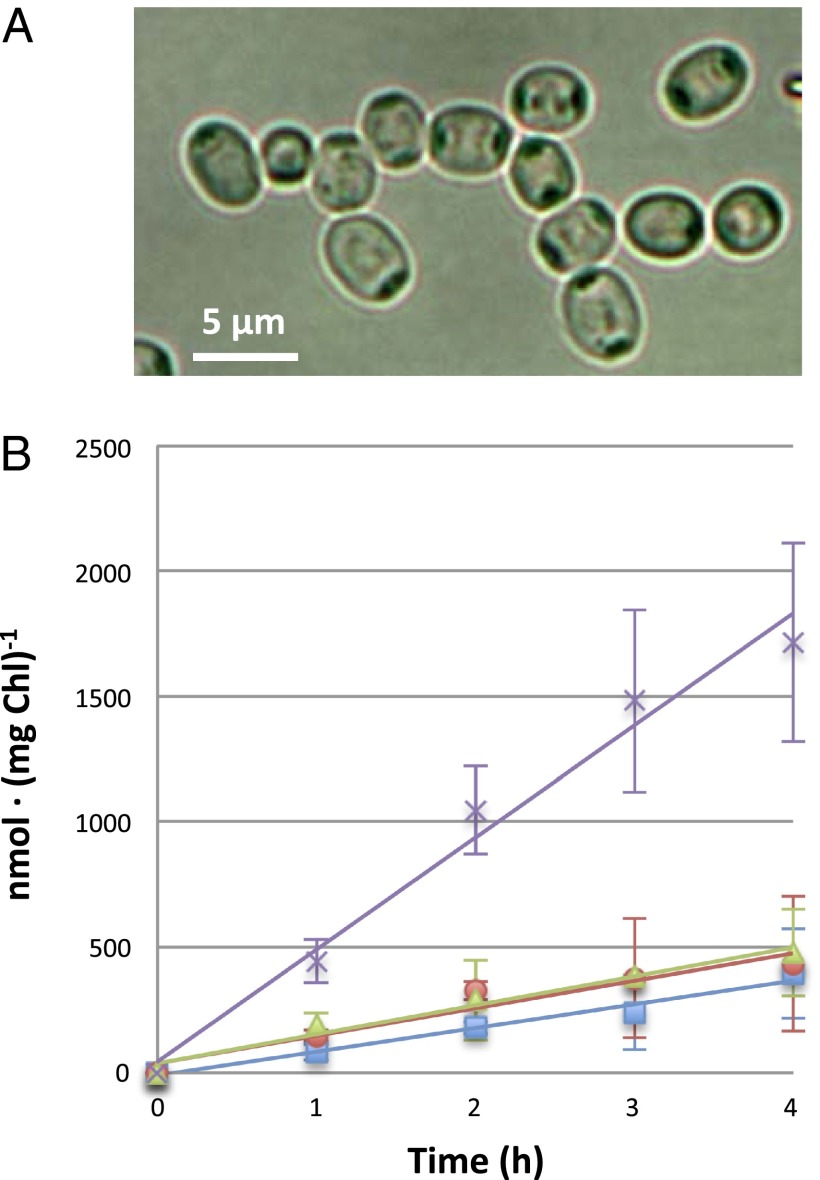

Production of β-Aspartyl-arginine by Isolated Heterocysts.

We reasoned that if the product of the cyanophycinase reaction, β-aspartyl-arginine, is metabolized to a limited extent in the heterocysts, being rather exported by them, isolated heterocysts might release the dipeptide into the incubation medium. We then studied the production of β-aspartyl-arginine in suspensions of heterocysts that were largely devoid of vegetative cells (Fig. 4A). After incubation in a buffer for different times up to 4 h, supernatants from these heterocyst suspensions were subjected to HPLC analysis. As shown in Fig. 4B, β-aspartyl-arginine was released at a rate of 447 nmol ± 107 (mg Chl)-1 h−1 (mean and SD, n = 4), whereas three other amino acids, arginine, aspartate and glutamate, were released at appreciable but lower rates [about 100 nmol (mg Chl)-1 h−1 for the three of them]. β-Aspartyl-arginine could result from cyanophycin degradation catalyzed by cyanophycinase, and arginine and aspartate could be produced, at least in part, by hydrolysis of the dipeptide catalyzed by the low level of isoaspartyl dipeptidase present in the heterocysts. On the other hand, glutamate could be released because reactants (such as ammonia) needed for biosynthesis of glutamine (6) were not provided in these experiments.

Fig. 4.

Release of β-aspartyl-arginine and amino acids by heterocysts isolated from wild-type Anabaena. (A) Light micrograph of heterocysts isolated from bubbled cultures as described in SI Materials and Methods. Preparations contained 90.5 ± 2.5% heterocysts that were undamaged as judged by visual inspection, 8.0 ± 2.5% heterocysts that might be damaged, and 1.5 ± 0.5% vegetative cells (mean and SD; n = 4). (B) Heterocyst preparations described in A were incubated in 10 mM TES-NaOH buffer (pH 7.5), and suspension supernatants from the indicated time points were analyzed by HPLC. Data, presented as nmol of amino acid (or dipeptide) released normalized by the concentration of Chl in the heterocyst suspension, are the mean and SD from four (three in the case of arginine) independent experiments. Amino acids that were consistently detected in the supernatants (glutamate, red circles; aspartate, blue squares; arginine, green triangles) and β-aspartyl-arginine (magenta crosses) are shown.

Heterocysts isolated from the dipeptidase mutant, strain CSMI6, produced β-aspartyl-arginine at rates [393 ± 55 nmol (mg Chl)-1 h−1; mean and SD, two experiments] similar to those observed with heterocysts from the wild type. Heterocysts isolated from a mutant of gene cphA1, which encodes the main cyanophycin synthetase in Anabaena (17), produced the dipeptide only at low rates [12.25 ± 2.30 nmol (mg Chl)-1 h−1; mean and SD, two experiments]. These results indicate that production of the dipeptide by isolated heterocysts is essentially dependent on cyanophycin.

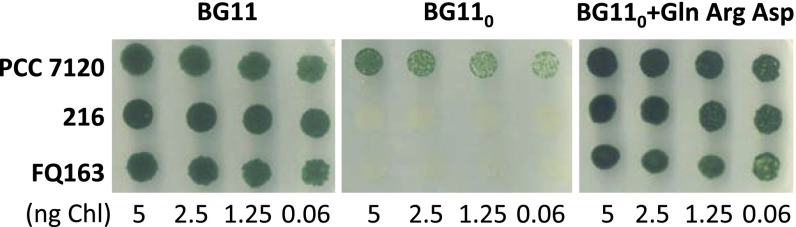

Amino Acid-Dependent Growth.

Our results imply that β-aspartyl-arginine is a nitrogen vehicle to feed the vegetative cells in the diazotrophic filament. Therefore, arginine, aspartate, and the previously known nitrogen vehicle glutamine may together provide nitrogen to sustain the growth of the vegetative cells. We then asked whether these three amino acids, for which cytoplasmic membrane transporters are present in Anabaena (28, 30), could support growth of nitrogen fixation mutants of this cyanobacterium in the absence of a readily assimilated nitrogen source such as nitrate or ammonium. The growth of Anabaena sp. strains 216, a mutant of the heterocyst differentiation transcription factor HetR (31), and FQ163, a mutant of the Major Facilitator Superfamily protein HepP needed to form the heterocyst envelope polysaccharide layer (32), was compared with that of the wild type in BG110 medium supplemented with 1 mM (Fig. 5) or 0.5 mM (Fig. S6) each of the three amino acids. Whereas no growth of the mutants was observed in the absence of combined nitrogen, as expected, robust growth, similar to that obtained with nitrate as the nitrogen source, was observed with the three amino acids together. With the single amino acids, the strongest growth was obtained with glutamine (see Fig. S6 for tests with the single amino acids or amino acid pairs). These results are consistent with the idea that arginine, aspartate, and glutamine can together represent the source of nitrogen for vegetative cells in the diazotrophic Anabaena filament.

Fig. 5.

Growth tests of Anabaena sp. strains PCC 7120, 216 (hetR) and FQ163 (hepP) in BG110 solid medium supplemented with 10 mM TES-NaOH buffer (pH 7.5) and nitrate (BG11) or 1 mM each glutamine (Gln), arginine (Arg), and aspartic acid (Asp). Spots were inoculated with an amount of cells containing the indicated amount of Chl, and the plates were incubated under culture conditions for 10 d and photographed.

Discussion

The polar accumulation of cyanophycin granules is a distinctive feature of cyanobacterial heterocysts. Consistent with a role of cyanophycin as a dynamic reservoir of nitrogen (20), activities of cyanophycin synthetase and cyanophycinase are detected at high levels in heterocysts (25). In contrast, as shown in this work with an All3922-GFP fusion and by determination of the enzyme activity, isoaspartyl dipeptidase accumulates preferentially in vegetative cells. This observation implies a compartmentalized degradation of cyanophycin, with the first step (catalyzed by cyanophycinase) taking place in the heterocysts and the second step (catalyzed by the dipeptidase) taking place mainly in the vegetative cells. Because β-aspartyl-arginine is not accumulated at high concentrations in wild-type Anabaena filaments, this compartmentalized metabolism of cyanophycin implies in turn that during diazotrophic growth, the dipeptide is transferred from heterocysts to be hydrolyzed in the vegetative cells. Consistently, isolated heterocysts release substantial amounts of β-aspartyl-arginine when incubated in a buffer, although the mechanism of release is currently unknown. In the dipeptidase mutant, strain CSMI6, a substantial accumulation of cyanophycin granules was observed in the cells of the filament. This suggests that high levels of β-aspartyl-arginine impair cyanophycin degradation, perhaps through a feedback inhibition of cyanophycinase.

As observed with cphA (cyanophycin synthetase) mutants from different species of Anabaena sp., under diazotrophic conditions, cyanophycin synthesis is required only for optimal growth (16, 17). Blocking cyanophycin degradation in Anabaena by inactivation of cphB (cyanophycinase) genes has, however, a clear impact on the rate of diazotrophic growth, which is reduced to about 62–64% of the wild-type rate (17). Inactivation of the Anabaena isoaspartyl dipeptidase (All3922) reduces the diazotrophic growth rate to about 54% of the wild-type value. Thus, blocking cyanophycin degradation by inactivation of either cyanophycinase or the dipeptidase has similar effects on diazotrophic growth. These observations imply that in Anabaena, nitrogen does not need to take the route of cyanophycin, but that once synthesized, cyanophycin has to be degraded to permit normal growth. Lack of degradation makes cyanophycin into a nitrogen sink (17). As previously discussed (18), when cyanophycin synthesis is not possible, arginine might be transferred directly from heterocysts to vegetative cells. Interestingly, we have observed that the isolated heterocysts can also release arginine and aspartate. These amino acids were found among the first products of nitrogen fixation in heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria (4).

Our results implying intercellular transfer of β-aspartyl-arginine, together with the possible transfer of arginine (alone or with aspartate), are to be considered together with previous results that identified glutamine as a nitrogen vehicle in the diazotrophic filaments of heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria (5, 6). Glutamine, arginine, and aspartate can together feed the vegetative cells for nitrogen, as evidenced by the robust growth of two heterocyst differentiation mutants of Anabaena when supplied with a mixture of the three amino acids as the sole nitrogen source (Fig. 5 and Fig. S6). Growth of different species of Anabaena sp. using glutamine or arginine as nitrogen source has also been reported previously (33–35). Although the exact equation of intercellular nutrient exchange in the diazotrophic Anabaena filament is unknown, movement of sucrose, glutamate, and alanine from vegetative cells to heterocysts and of glutamine and β-aspartyl-arginine from heterocysts to vegetative cells could result in a net transfer of reduced carbon to heterocysts and of fixed nitrogen to vegetative cells. A possible gradient of arginine or of an arginine-containing compound in the diazotrophic filament of Anabaena has been noted (19).

The compartmentalized metabolism of cyanophycin shown in this work represents an optimized way of using this nitrogen reservoir in heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. Cyanophycin synthesis after nitrogen fixation has been suggested to serve an important function by removing from solution the products of nitrogen fixation, which could have a negative feedback effect on nitrogenase (18–20). Interestingly, this strategy appears to be generally used in nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria independently of whether they are unicellular (36) or filamentous (37). However, a limited hydrolysis of β-aspartyl-arginine in the heterocysts adds the benefit of avoiding the release of the constituent amino acids back in the cytoplasm of the nitrogen-fixing cell. Thus, cyanophycin metabolism appears to have evolved to increase the efficiency of nitrogen fixation taking advantage of the multicellular nature of heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria.

Materials and Methods

Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 was grown photoautotrophically at 30 °C with the nitrogen source indicated in each experiment, in shaken cultures with air levels of CO2 or in bubbled cultures supplemented with bicarbonate/CO2. Anabaena mutants used in this work are summarized in Table S2. Strain CSMI6 bears an all3922 gene with an internal fragment deleted and was constructed in a way such that it bears no antibiotic resistance marker. Strain CSMI6-C (SpR/SmR) is mutant CSMI6 complemented with wild-type all3922 present in plasmid pCSAM200 (plasmids used in this work are summarized in Table S2), which includes the pDU1 replicon from a Nostoc sp. that can replicate in Anabaena. Strain CSMI27 (SpR/SmR) bears an all3922-sf-gfp fusion gene integrated as part of a nonreplicative plasmid in the all3922 locus. The protein encoded by the fusion gene contains the superfolder GFP fused through a four-glycine linker to the C terminus of All3922. Construction of these strains is detailed in SI Materials and Methods, and oligodeoxynucleotide primers used for strain construction and verification are listed in Table S3.

Growth tests in liquid and solid media, quantification of protein and chlorophyll a (Chl), isoaspartyl dipeptidase, glutamine synthetase and nitrogenase activity measurements, and microscopic inspection of cultures and heterocyst preparations were performed as detailed in SI Materials and Methods. In strain CSMI27, sf-GFP fluorescence was visualized by confocal microscopy (excitation at 488 nm; emission collected from 500 to 520 nm) and quantified using the wild-type strain PCC 7120 as a control.

CGP preparations were obtained by disruption of filaments in a French pressure cell at 20,000 p.s.i., collecting the granules by centrifugation and dissolving them in 0.1 N HCl as detailed in SI Materials and Methods. The amount of cyanophycin was then estimated by determining arginine by the Sakaguchi reaction. Heterocysts were isolated from filaments grown in bubbled cultures in media lacking combined nitrogen. Filaments treated with 1 mg lysozyme mL−1 were disrupted by passage two or three times through a French pressure cell at 3,000 psi, and the heterocysts were collected by low-speed centrifugation. Determination of amino acids (including β-aspartyl-arginine) in cell-free extracts, in material extracted from whole filaments with 0.1 HCl or by boiling, or in supernatants from heterocyst suspensions was performed by high-pressure liquid chromatography as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Lockau for a sample of β-aspartyl-arginine, C. P. Wolk for a critical reading of the manuscript, S. Picossi for useful discussions, F. J. Florencio’s lab for help with the glutamine synthetase assay, and A. Orea and C. Parejo for technical assistance. M.B. was the recipient of a Formación del Personal Investigador fellowship/contract from the Spanish Government. Research was supported by Grant BFU2011-22762 from Plan Nacional de Investigación, cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1318564111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Flores E, Herrero A. Compartmentalized function through cell differentiation in filamentous cyanobacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(1):39–50. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar K, Mella-Herrera RA, Golden JW. Cyanobacterial heterocysts. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(4):a000315. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolk CP. Movement of carbon from vegetative cells to heterocysts in Anabaena cylindrica. J Bacteriol. 1968;96(6):2138–2143. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.6.2138-2143.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolk CP, Thomas J, Shaffer PW, Austin SM, Galonsky A. Pathway of nitrogen metabolism after fixation of 13N-labeled nitrogen gas by the cyanobacterium, Anabaena cylindrica. J Biol Chem. 1976;251(16):5027–5034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolk CP, Austin SM, Bortins J, Galonsky A. Autoradiographic localization of 13N after fixation of 13N-labeled nitrogen gas by a heterocyst-forming blue-green alga. J Cell Biol. 1974;61(2):440–453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.61.2.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas J, Meeks JC, Wolk CP, Shaffer PW, Austin SM. Formation of glutamine from [13n]ammonia, [13n]dinitrogen, and [14C]glutamate by heterocysts isolated from Anabaena cylindrica. J Bacteriol. 1977;129(3):1545–1555. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.3.1545-1555.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martín-Figueroa E, Navarro F, Florencio FJ. The GS-GOGAT pathway is not operative in the heterocysts. Cloning and expression of glsF gene from the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. FEBS Lett. 2000;476(3):282–286. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01722-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jüttner F. 14C-labeled metabolites in heterocysts and vegetative cells of Anabaena cylindrica filaments and their presumptive function as transport vehicles of organic carbon and nitrogen. J Bacteriol. 1983;155(2):628–633. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.628-633.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pernil R, Herrero A, Flores E. Catabolic function of compartmentalized alanine dehydrogenase in the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(19):5165–5172. doi: 10.1128/JB.00603-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schilling N, Ehrnsperger K. Cellular differentiation of sucrose metabolism in Anabaena variabilis. Z Naturforsch C. 1985;40(11−12):776–779. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curatti L, Flores E, Salerno G. Sucrose is involved in the diazotrophic metabolism of the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. FEBS Lett. 2002;513(2-3):175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.López-Igual R, Flores E, Herrero A. Inactivation of a heterocyst-specific invertase indicates a principal role of sucrose catabolism in heterocysts of Anabaena sp. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(20):5526–5533. doi: 10.1128/JB.00776-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vargas WA, Nishi CN, Giarrocco LE, Salerno GL. Differential roles of alkaline/neutral invertases in Nostoc sp. PCC 7120: Inv-B isoform is essential for diazotrophic growth. Planta. 2011;233(1):153–162. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang NJ, Simon RD, Wolk CP. Correspondence of cyanophycin granules with structured granules in Anabaena cylindrica. Arch Microbiol. 1972;83(4):313–320. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman DM, Tucker D, Sherman LA. Heterocyst development and localization of cyanophycin in N2-fixing cultures of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (Cyanobacteria) J Phycol. 2000;36(5):932–941. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziegler K, Stephan DP, Pistorius EK, Ruppel HG, Lockau W. A mutant of the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 lacking cyanophycin synthetase: Growth properties and ultrastructural aspects. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;196(1):13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Picossi S, Valladares A, Flores E, Herrero A. Nitrogen-regulated genes for the metabolism of cyanophycin, a bacterial nitrogen reserve polymer: Expression and mutational analysis of two cyanophycin synthetase and cyanophycinase gene clusters in heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(12):11582–11592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haselkorn R. Heterocyst differentiation and nitrogen fixation in cyanobacteria. In: Elmerich C, Newton WE, editors. Associative and Endophytic Nitrogen-fixing Bacteria and Cyanobacterial Associations. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ke S, Haselkorn R. The Sakaguchi reaction product quenches phycobilisome fluorescence, allowing determination of the arginine concentration in cells of Anabaena strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 2013;195(1):25–28. doi: 10.1128/JB.01512-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carr NG. Biochemical aspects of heterocyst differentiation and function. In: Papageorgiou GC, Packer L, editors. Photosynthetic Prokaryotes: Cell Differentiation and Function. New York: Elsevier; 1983. pp. 265–280. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziegler K, et al. Molecular characterization of cyanophycin synthetase, the enzyme catalyzing the biosynthesis of the cyanobacterial reserve material multi-L-arginyl-poly-L-aspartate (cyanophycin) Eur J Biochem. 1998;254(1):154–159. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg H, et al. Biosynthesis of the cyanobacterial reserve polymer multi-L-arginyl-poly-L-aspartic acid (cyanophycin): Mechanism of the cyanophycin synthetase reaction studied with synthetic primers. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267(17):5561–5570. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter R, Hejazi M, Kraft R, Ziegler K, Lockau W. Cyanophycinase, a peptidase degrading the cyanobacterial reserve material multi-l-arginyl-poly-l-aspartic acid (cyanophycin): Molecular cloning of the gene of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, expression in Escherichia coli, and biochemical characterization of the purified enzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263(1):163–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hejazi M, et al. Isoaspartyl dipeptidase activity of plant-type asparaginases. Biochem J. 2002;364(Pt 1):129–136. doi: 10.1042/bj3640129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta M, Carr NG. Enzyme activities related to cyanophycin metabolism in heterocysts and vegetative cells of Anabaena spp. J Gen Microbiol. 1981;125(1):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pédelacq JD, Cabantous S, Tran T, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(1):79–88. doi: 10.1038/nbt1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson RB, Wolk CP. High recovery of nitrogenase activity and of Fe-labeled nitrogenase in heterocysts isolated from Anabaena variabilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75(12):6271–6275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.12.6271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pernil R, Picossi S, Mariscal V, Herrero A, Flores E. ABC-type amino acid uptake transporters Bgt and N-II of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 share an ATPase subunit and are expressed in vegetative cells and heterocysts. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67(5):1067–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dharmawardene MWN, Haystead A, Stewart WDP. Glutamine synthetase of the nitrogen-fixing alga Anabaena cylindrica. Arch Mikrobiol. 1973;90(4):281–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00408924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Picossi S, et al. ABC-type neutral amino acid permease N-I is required for optimal diazotrophic growth and is repressed in the heterocysts of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57(6):1582–1592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buikema WJ, Haselkorn R. Characterization of a gene controlling heterocyst differentiation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena 7120. Genes Dev. 1991;5(2):321–330. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.López-Igual R, et al. A major facilitator superfamily protein, HepP, is involved in formation of the heterocyst envelope polysaccharide in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(17):4677–4687. doi: 10.1128/JB.00489-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neilson AH, Larsson T. The utilization of organic nitrogen for growth of algae: Physiological aspects. Physiol Plant. 1980;48(4):542–553. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thiel T, Leone M. Effect of glutamine on growth and heterocyst differentiation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol. 1986;168(2):769–774. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.769-774.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrero A, Flores E. Transport of basic amino acids by the dinitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC 7120. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(7):3931–3935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Sherman DM, Bao S, Sherman LA. Pattern of cyanophycin accumulation in nitrogen-fixing and non-nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 2001;176(1-2):9–18. doi: 10.1007/s002030100281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finzi-Hart JA, et al. Fixation and fate of C and N in the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium using nanometer-scale secondary ion mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(15):6345–6350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810547106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.