Abstract

Hypoxia-ischemia (H/I) brain injury results in various degrees of damage to the body, and the immature brain is particularly fragile to oxygen deprivation. Hypothermia and erythropoietin (EPO) have long been known to be neuroprotective in ischemic brain injury. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has recently been recognized as a potent modulator capable of regulating a wide repertoire of neuronal functions. This review was based on studies concerning the involvement of BDNF in the protection of H/I brain injury following a search in PubMed between 1995 and December, 2011. We initially examined the background of BDNF, and then focused on its neuroprotective mechanisms against ischemic brain injury, including its involvement in promoting neural regeneration/cognition/memory rehabilitation, angiogenesis within ischemic penumbra and the inhibition of the inflammatory process, neurotoxicity, epilepsy and apoptosis. We also provided a literature overview of experimental studies, discussing the safety and the potential clinical application of BDNF as a neuroprotective agent in the ischemic brain injury.

Keywords: brain-derived neurotrophic factor, hypoxic, ischemia, brain injury

Contents

Introduction

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

Receptors of BDNF and signalling pathways

BDNF has neuroprotective effect in experimental stroke models

Applications and challenges

Conclusion

1. Introduction

Hypoxia-ischemia (H/I) brain injury results in various degrees of damage to the body, and the immature brain is particularly fragile to oxygen deprivation, termed hypoxia-ischemia brain damage (HIBD), which can be caused by extreme prematurity or perinatal asphyxia. For adolescents or adults, similar pathological changes are often caused by hypertension or aneurysm rupture, termed ischemic stroke. These processes resulted in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE).

Hypothermia and erythropoietin (EPO) have long been known to be neuroprotective, based on the pathologic changes in HIE. For instance, EPO may promote angiogenesis and reduce apoptosis (1). Currently, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is also considered to be a potent modulator, beneficial to neuronal functions. In this review, we first examined the background of BDNF, then focused on its neuro-protective mechanisms against ischemic stress, and discussed the potential application of BDNF in clinic

2. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

Forms

Nerve growth factor (NGF), BDNF, neurotrophins (NT) (NT-3, NT-4, NT 4/5 and NT-6) constitute the protein family of mammalian NT (2,3). BDNF was discovered in 1982, originally described as a small dimeric protein (4). There are two types of BDNF: pro- and mature BDNF, present in the human body (5). Pro-BDNF is a 32-kDa precursor, comprising 247 amino acids with N-glycosylated and glycosulphated residues within the prodomain (6). Following the initial generation, most of the pro-BDNF is then packaged into vesicles in a regulated pathway and undergoes N-terminal cleavage by extracellular proteases, such as plasmin, metalloproteinase gene matrilysin (MMP7) (7,8), tPA/plasmin cascade (8) and extracellular matrix-metalloproteinases (9). In trans-Golgi network (TGN), the ‘pro-region’ is cleaved resulting in the formation of mature BDNF (14 kDa), a biologically active form with C-terminal dimers (10). This mature BDNF is then released mainly by the neurons through constitutive secretion or in an activity-dependent manner (6). Another subtype of pro-BDNF, small amounts of a 28-kDa protein, was identified by immunoprecipitation with BDNF antibodies. However, it was not an obligatory intermediate in the formation of the mature BDNF (11).

Proproteins must undergo a variety of post-translational processes to yield biologically active peptides. The two forms of extracellular BDNF, pro- and mature BDNF, act in different ways. Mature BDNF is crucial in the protection of the neonatal or developing brain from ischemia injury (12). In cultured hippocampal neurons, low- and high-frequency neuronal activities increased pro-BDNF levels (5). However, only high-frequency activity induces tissue plasminogen activator secretion, resulting in the conversion of pro- to mature BDNF (13). Additionally, the highest levels of pro-BDNF are observed perinatally, then it declines with age, although the proform remains detectable in adulthood. These data partly provide the reason that brains of newborns and infants are more fragile to ischemia stroke due to low-frequency neuronal activities and the lack of an adequate amount of mature BDNF in the central nervous system (CNS).

BDNF Val66Met is a common single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the human BDNF gene resulting in a valine (Val) to methionine substitution in the prodomain, termed Val66Met. The BDNF Val66Met has shed light on psychiatric studies, particularly in schizophrenia, anxiety-like behavior and depressive symptoms (14), which belong to the sequelae of H/I damage.

Synthesis and location

BDNF is broadly expressed in the developing and adult mammalian brain (15), synthesized in several areas of the hypothalamus, including the paraventricular (PVN), ventromedial (VMN) and dorsomedial nuclei (DMN), as well as the lateral hypothalamic area (LH). Accordingly, BDNF mRNA and proteins are widespread in almost all the cortical areas as well as other tissues, including the neural soma, dendrites, fibres and amygdala (16).

Large amounts BDNF are believed to be stored or secreted from non-neuron cells, when attacks occur, such as human platelets (17). It was also found to be present in the ependymal, microglial and endothelial cells of cerebral arterioles and astrocytes, respectively (18). Peripherally, BDNF accumulates in the vascular endothelium, neuromuscular synapse, muscle and liver tissue (19), which is essential for neuronal repair when stroke occurs.

BDNF gene

The rodent BDNF gene was initially described by Aid et al (20) and comprises at least eight distinct promoters, initiating the transcription of multiple distinct mRNA transcripts, comprising four 5′-exons (I–IV) linked to separate promoters, and one 3′-exon (V) that contains the entire open reading frame for the BDNF protein. Pruunsild et al (21) have identified new splice variants in human and rodents, respectively, demonstrating that at least 11 different BDNF transcripts can be generated from the mammalian rodent BDNF gene by alternative splicing. The activation of various BDNF promoters is region-specific and depends on the type of stimulus (22). A single BDNF protein is produced from several splice variants with different 5′-UTRs (23,24).

3. Receptors of BDNF and signalling pathways

If left uncleaved, pro-BDNF selectively activates its high-affinity receptor, the p75 receptor, mainly inducing pro-apoptotic signalling pathways (25). Mature BDNF binds with high specificity to the tropomyosin-related kinase receptor type B (TrkB) (26) and to the low-affinity neurotrophin receptor p75, then exerts its actions via interactions between these two trans-membrane receptors, separately or in collectively, potentially leading to neuronal death or survival.

TrkB

The Trk receptor tyrosine kinase family includes TrkA and TrkC, which are receptors for NGF and NT3, respectively. The family also includes TrkB, which mediates the effects of BDNF and NT 4/5 (27).

BDNF exerts multiple biological actions through TrkB receptors (13,28). Similar to BDNF, TrkB is widely expressed in the adult brain, including the cortex, hippocampus, multiple brain stem and spinal cord nuclei (29).

Several TrkB isoforms have been observed in the mammalian CNS. The full-length TrkB isoform is a typical tyrosine kinase wherein homodimerization during ligand binding causes intracellular cross-tyrosine phosphorylations (30). In addition, truncated forms of TrkB [T1 and T2 in rat; T1 and T-Src homology and collagen protein (T-Shc) in humans] lacking the tyrosine kinase component of the receptor, are found in neurons and glia. T1 is predominantly expressed in the brain and may act as a dominant negative inhibitor of BDNF signalling by forming heterodimers with full-length TrkB (31).

BDNF binding to TrkB triggers autophosphorylation of the tyrosine residue in its intracellular domain, leading to ligand-induced dimerization in each receptor, which activates several intracellular signalling pathways with various functions (32). More specifically, when NT binds to Trk receptors, three enzymes are considered to be the main regulators: mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) (33) and phospholipase C γ (PLCγ) (34).

Trk family members recruit and increase the phosphorylation of PLCγ and the Src homology and collagen protein (Shc). Binding of the adaptor proteins Shc and the growth factor receptor substrates 2 (FRS-2) to Trk leads to the activation of the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways (35). Several small G proteins, including Rap-1 and the Cdc-42-Rac-Rho family, also participate in this process (34). The role of the ERK and PI3-kinase pathways in neonatal H/I brain injury in the presence of BDNF is gradually becoming clear (36,37). Docking of PLCγ to a separate site of TrkB leads to the production of diacylglycerol, a transient activator of protein kinase C (PKC) and inositol trisphosphate (IP3), and eventually mobilizes intracellular calcium (38).

Trk receptor activation has variable downstream specificity, and significant cross-talk is observed among the sites of action in these three pathways.

p75

p75, also known as p75NTR (p75 neurotrophin receptor), is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNF) superfamily. In adulthood its expression is restricted to basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and is present in relatively few cortical neurons (39). p75 is mainly expressed during early neuronal development, whereas in adults, p75 is re-expressed in various pathological conditions, including epilepsy, axotomy and neurodegeneration (40).

The low-affinity receptor p75 binds to pro-neurotrophin with high affinity, transmitting positive and negative intracellular signals. It is particularly significant in mediating pro-neurotrophin signalling and often induces inversed biological effects on TrkB receptors (41). When compared to mature BDNF, pro-BDNF promotes neuronal survival via TrkB, preferentially activating p75 to mediate neuronal cell death, particularly apoptosis (42). Therefore, the amount of pro-BDNF is critical in neuronal cell death.

An analysis of the spatiotemporal profile of p75 expression after an ischemic lesion induced by cortical devascularization (CD) demonstrated that p75 expression is expressed in isolated neurons within the ischemic lesion site. These p75+ neurons present morphological alterations and active caspase-3 staining. Peak p75 expression has been shown to occur 3 days post-lesion in the penumbra. Therefore, the authors conclude that p75 expression is localized in selected neurons in the ischemic lesion and that these p75+ neurons are probably condemned to apoptotic cell death (39).

Several signalling pathways have been implicated in the actions of p75 in the absence of Trk receptors, including the induction of nuclear factor-κ B (NF-κB) and c-Jun kinase activities (43).

Chaperone proteins

Chaperone proteins, carboxypeptidase E (CPE) (44) and sortilin (14), are two additional receptors of BDNF. The binding of BDNF to the lipid-raft-associated sorting receptor CPE in the TGN is necessary for sorting into secretory vesicles. CPE is subsequently internalized and transported through the endocytic recycling compartment back to the TGN (45). Most BDNF in this regulated secretory pathway is transported to post-synaptic dendrites and spines (46).

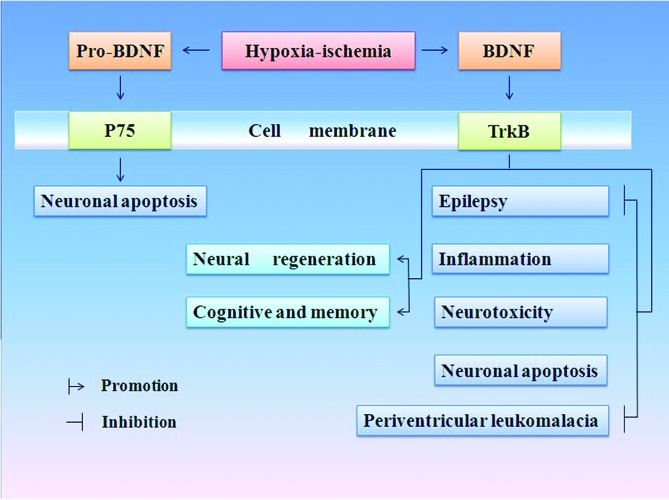

Sortilin interacts specifically with BDNF in a region encompassing methionine substitution and co-localizes with BDNF in secretory granules in neurons. Certain p75+ neurons are also positive for sortilin (47). CPE and sortilin have thus been identified as candidate proteins that potentially regulate the intracellular localization of BDNF within neurons (48). The ways BDNF exhibits positive effects is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Possible mechanisms of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in neuronal survival after hypoxia-ischemia (H/I). Pro-BDNF selectively activates p75 receptor, thereby inducing pro-apoptotic signalling pathways (25). Mature BDNF binds with kinase receptor type B (TrkB), exhibiting a positive effect in two ways, i.e., one side promotes neural regeneration and rehabilitation of cognition and memory, while the other side is against the pathological process of inflammation, neurotoxicity, periventricular leukomalacia, epilepsy and apoptosis.

4. BDNF has neuroprotective effect in experimental stroke models

The major neuropathology after H/I insult begins during the acute insult and extends into the reperfusion phase (49). The progress is short for ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. It may involve the following pathophysiologic aspects: i) apoptosis; ii) free-radical generation and activation of inflammatory mediators, e.g., acidosis (50); iii) excessive extracellular glutamate excitotoxicity and intracellular accumulation of calcium (51) and iv) depleted energy reserves and loss of high-energy phosphate compounds. Thus, energy deprivation along with increased levels of harmful factors, either intracellular or extracellular, disrupts neuronal homeostasis. Consequently, clinical manifestations, such as periventricular leukomalacia, epilepsy, cognition and memory deficiency were also present.

In the subsequent sections, the mechanism of the action of BDNF in multiple protective roles against ischemic brain injury is examined.

Anti-apoptosis

Evidence showed that BDNF was beneficial for the survival of neurons through anti-apoptotic effect. Infected with adeno-associated viral vector inserted with BDNF gene (AAV-BDNF), neurite cells may be able to produce BDNF function to promote its own outgrowth and protect neurons from serum deprivation-induced apoptosis (52). Besides, cultured rat hippocampal neurons were injured by amyloid β and then infected with AAV-BDNF to examine the neuroprotective effects of BDNF. The results showed that the Ca2+ balance was maintained in the AAV-BDNF treatment group, and that BDNF may reduce neuron apoptosis by increasing the expression of the Bcl-2 anti-apoptosis protein and inhibiting intracellular calcium overload (53).

In vitro, 2.1 μg/day BDNF were delivered continuously via intraventricular infusion pumps. The mean infarct volume after venous occlusion was significantly smaller in BDNF-treated rats at 2 days (1.49±1.44 vs. 3.66±1.51%), and fewer TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells were detected 2 days later (17.0±15.1 vs. 39.0±19.6) compared to the controls (54). Similarly, in global ischemia induced by a four-vessel occlusion in rat, 0.06 mg/h BDNF diluted in artificial cerebral spinal fluid was administered by an osmotic minipump, which was implanted after reperfusion. Data showed that the pyramidal cell count was 439.6±18.5 in the BDNF group, and 18.3±10.6 in the ischemia group at day 7 (55). When 5 mg human BDNF was injected intravitreally after H/R, the number of TUNEL- and caspase-2-positive cells in the BDNF-treated group vs. the control was 545.2±29.7 vs. 22370.3±122.5 cells/mm2 and 124.4±35.4 vs. 244.6±15.7 cells/mm2 at 6 h after reperfusion (56). Additionally, in a postnatal day 7 rat model, H/I injury to the developing brain is a strong apoptotic stimulus leading to caspase-3 activation, although BDNF can block this process in vivo (28).

Anti-inflammation

Inflammation responds to cerebral ischemia rapidly, activates the local inflammatory cells (mostly microglia), producing relevant mediators and translocation of intercellular nuclear factors.

Cytokines and chemokines that trigger leukocyte infiltration or glial activation and proliferation, are released following ischemia, and might either be beneficial or detrimental. A possible contributor to this dichotomy of responses depends on the degree to which proximal neurons are injured. Twenty four hours after hypoxia-exposure of the neuronal cultures, the classic microglial proinflammatory mediators, including inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), TNF and interleukin-1-β (IL-1β), are upregulated only in response to mild neuronal injuries, while the trophic microglial effector BDNF is upregulated in response to the degrees of neuronal ischemia injuries (57,58).

In the inflammatory process, BDNF may promote microglial proliferation and phagocytic activity in vitro (59) and increase the number of phagocytotic microglia and activated microglia that, in turn, secretes BDNF (60). When conditioned media from injured neurons [neuron-conditioned media; (NCM)] were added to microglial cultures following H/I, BDNF released from microglia was upregulated, suggesting that BDNF might contribute to the anti-inflammatory activity induced by microglia (61). TNF-α has been proven to exacerbate cerebral injury of ischemia (62), while interleukin (IL-10), an anti-inflammatory cytokine, has a neuroprotective role in ischemic stroke (63). Jiang et al (60) reconfirmed that intranasal administration of BDNF in H/I rats can suppress TNF-α and its mRNA expression, while increasing IL-10 and its mRNA expression. Peng et al (64) treated neural stem cells (NSCs) with BDNF siRNA, and found that imipramine (IM) increases the neuroprotective effects, suppresses the inflammatory process in NSCs via the modulation of the MAPK pathway and Bcl-2 cascades, indirectly evaluating the anti-inflammatory effect of BDNF.

Anti-neurotoxicity

Depletion of glucose and oxygen supply causes a primary energy failure and initiates a cascade of biochemical events leading to cell dysfunction. A consequent reperfusion injury often deteriorates the brain metabolism by increasing the oxidative stress damage.

Neurotoxicant trimethyltin (TMT) induces a significant reduction of cell survival, neuronal differentiation and concomitant earlier activation of cleaved caspase-3. However, overexpression of BDNF firmly protects differentiated NSC against TMT-induced neurotoxicity through the PI3K/Akt and MAPK-signaling pathways (65). Addition of 100 mM ethanol to a human neuronal cell model, SH-SY5Y cells, showed the secreted amount of BDNF and the cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB) activity to be significantly reduced by ethanol. Additionally, exogenous BDNF has a protective effect against ethanol-induced damage in primary culture neurons from rat hippocampi (66).

BDNF resists glutamate cytotoxicity depending on its concentration (67). Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, always binding its receptor glutamate receptors N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) under pathological circumstances, causing ascendency of cytosolic calcium (68). Following H/I, the concentrations of glutamate and ATP are increased (61), and excitatory amino acids (EAA) are secreted, allowing glutamate to accumulate to excitotoxic levels. BDNF inhibited neurotoxicity induced by glutamate and NO donors in cultured cortical neurons, especially dopamine neurons (69).

Furthermore, BDNF mRNA accumulates in distal dendrites to activate NMDAR and TrkB receptor (70), the former might have pro-apoptotic excitotoxic activity. By contrast, signalling via TrkB has been largely considered to protect neurons antagonizing the NMDAR-mediated excitotoxic cell death. The cross-talk and feedback loops between BDNF and the NMDAR signalling was reviewed by Georgiev et al (71).

Promotion of neural regeneration

Neurogenesis involves cell proliferation, migration and differentiation (46). To facilitate regeneration among central and peripheral neurons after H/I, the enrichment of BDNF around the injured region is essential. Zhu et al (72) evaluated functional recovery following the transplantation of BDNF-modified neural stem cells (NSCs) in a rat model of cerebral ischemia damage induced by temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO). Their findings showed that BDNF protein expression in rat embryonic NSCs transfected with the human BDNF gene (BDNF-NSCs) was upregulated, while neurite outgrowth in ganglion neurons were simulated, suggesting that BDNF increased neurogenesis in vitro. In vivo, BDNF promoted recovery of temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion. Zhu et al also assessed the neurological function deficiency for 12 weeks using the neurological severity score (NSS). NSS was significantly lower in the BDNF-NSC-transfected transplant group compared to the control groups for the 10-week time period (72).

BDNF may allow sustained regenerative signalling at synaptic sites (35). It induces structural instability in dendrites and spines restricted to particular portions of a dendritic arbor, and may help translate activity patterns into specific morphological changes (73). Furthermore, BDNF may increase the expression of markers for axonal sprouting and synaptogenesis, such as MAP1/2 or synaptophysin. Post-ischemic intravenous BDNF treatment improves functional motor recovery after thrombotic stroke (74).

Angiogenesis, another contribution of BDNF should be mentioned. Injection of BDNF fused with a collagen-binding domain (CBD-BDNF) into the lateral ventricle of MCAO rats, promoted neural regeneration and angiogenesis. Induction of neural differentiation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs) led to nerve repair and growth also via BDNF production. Nerve fiber length in ASCs matrigel implants was 1.3-fold greater compared to the control (75).

Protection against periventricular leukomalacia (PVL)

In premature infants, the H/I damage to the cerebral white matter usually involves PVL. Selected neuronal circuits as well as immature periventricular oligodendroglia, may die from the excitotoxicity, leading to chronic neurologic disability with cerebral palsy (76). In a previous study, Husson et al (77) injected rats with ibotenate generating white matter cysts resembling those detected in PVL. Those authors found that such white matter cysts in cortical and white matter lesions are reduced by BDNF. However, the exact effect was dependent upon the type of activated glutamate receptors, lesion localization and the developmental stage (Table I).

Table I.

Experiments on the roles of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in hypoxic-ischemic (H/I) injury.

| Experimental model | Treatment for injury | Intervention | BDNF activity for neuroprotection | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF protects the brain from hypoxic-ischemic injury | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cerebellar granule neurons culture | H/I Low K+ (5 mM) |

BDNF 100 ng/ml | BDNF has a direct effect on mature cerebellar granule neurons and can protect these neurons from apoptosis in low K+ | (84) |

| Cerebellar granule neurons culture | With K+ (5 mM) | BDNF 1–100 ng/ml | BDNF protects from K+/serum deprivation-induced apoptotic death of cerebellar granule neurons | (33) |

| Cerebellar granule neurons culture | H/I Low K+ (5 mM) |

BDNF 100 ng/ml | BDNF in the anti-apoptotic effect of NMDA in cerebellar granule neurons | (85) |

| Newborn SD rats |

Left common carotid artery was permanently ligated | BDNF ICV injection 5 μg/animal | BDNF treatment virtually eliminated the increase in caspase-3-like activity induced by HI BDNF to block H/I-induced caspase-3 activation and tissue loss | (86) |

| Newborn SD rats |

Left common carotid artery was permanently ligated, 8% oxygen flowed for 2.5 h | BDNF ICV injection 5 μg/animal | BDNF protects the neonatal brain from H/I injury in vivo via the ERK pathway, BDNF provides a promising solution to hypoxic injury due to its survival-promoting effects | (37) |

| Cultured neurons from embryonic SD rats | Hypoxia 85% N2, 5% CO2, 10% H2 | BDNF 100 ng/ml 24 h prior to hypoxia/immediately | BDNF is highly involved in preventing cortical neurons from hypoxia-induced neurotoxicity | (87) |

| Cultured neurons from embryonic SD rats | Hypoxia 85% N2, 5% CO2, 10% H2 | BDNF 50 ng/ml 30 min before hypoxia | The activation of ERK- and AKT-signalling pathway-mediated BDNF neuroprotective function against hypoxic-induced neurotoxicity | (37) |

| Cultured neurons from embryonic SD rats | Hypoxia 85% N2, 5% CO2, 10% H2 | BDNF 25, 50, 100 ng/ml 24 h before hypoxia/immediately | Extrinsic BDNF has a neuroprotective effect against hypoxic-induced neurotoxicity | (88) |

| Cultured neurons from embryonic SD rats | Hypoxia 85% N2, 5% CO2, 10% H2 | BDNF 100 ng/ml 24 h before hypoxia/immediately | The Ras-MAPK approach may be the major signal transferring way of BDNF in protecting the cortical neurons from H/I-induced neurotoxicity | (89) |

| Pregnant rats | Artery clamp | BDNF 2 μg was injected to caudal veins | BDNF demonstrates neuroprotective effects on rat embryo brain cells suffering from intrauterine H/I injury via the ERK signalling pathway | (90) |

| Adult female SD rats | MCAO 10 min of four-vessel occlusion | HBO | HBO preconditioning may be neuroprotective by reducing early apoptosis and inhibition of the conversion of early to late apoptosis, possibly through an increased brain BDNF level | (91) |

| Gerbil | Transient cerebral ischemia | Extract from TCE | Repeated supplement of TCE-protected neurons from ischemic damage induced by transient cerebral ischemia by maintaining BDNF levels | (92) |

| Cultured neurons from embryonic SD rats | Transient cerebral ischemia in the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells | Escitalopram 30 mg/kg | Pre- and post-treatments with escitalopram protects against ischemia-induced neuronal death in the CA1 induced by transient cerebral ischemic damage by the increase of BDNF | (93) |

| Cultured neurons from embryonic SD rats | Hypoxia 85% N2, 5% CO2, 10% H2 | BDNF 50 ng/ml | BDNF has neuroprotective effect on embryonic rat cortical neurons against hypoxia via CREB phosphorylation | (31) |

| Cultured neurons from embryonic SD rats | Hypoxia 85% N2,5% CO2, 10% H2 | BDNF 50 ng/ml | Hypoxia rapidly blocking ERKl/2 signalling pathway is involved in the protective effect of BDNF against hypoxic injury on in vitro-cultured neurons | (94) |

| Rat | Global ischemia | 0.06 mg/h BDNF intracerebroventricularly | BDNF inhibited the neuronal degeneration in the hippocampal regions | (55) |

| Rats | Cerebral venous ischemia | BDNF 2.1 μg/day | The mean infarct volume after venous occlusion was smaller, and fewer TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells were detected in BDNF-treated rats | (54) |

| Adult male SD rats | MCAO | LBD-BDNF 0.2 nmol injected into the right brain | LBD-BDNF-reduced infarct volume is associated with a parallel improvement in neurological functional outcome and neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampi | (86) |

| Rats | Temporary occlusion of the MCA (120 min) | Intranasal BDNF | BDNF protects brain from ischemic insult via modulating local inflammation in rats | (95) |

| Adult female SD rats | Ischemia (60 min) | Human BDNF 5 μg | The number of TUNEL- and caspase-2-positive cells was lower in the BDNF-treated group at 6 h, after reperfusion | (56) |

| Cortical neurons from rat embryos | H/I | 1, 10, 50, 100 ng/ml | BDNF demonstrated protection against apoptotic cell death | (28) |

| Rats | MCAO | CBD-BDNF 10 μl/Nat-BDNF 10 μl/lateral ventricle | CBD-BDNF promoted neural regeneration and angiogenesis, reduced cell loss, decreased apoptosis and improved functional recovery | (96) |

|

| ||||

| BDNF inhibition protects the brain from hypoxic-ischemic injury | ||||

|

| ||||

| Rat cortical cell cultures | BDNF 10, 30, 100 ng/ml | BDNF-induced neuronal necrosis was accompanied by reactive oxygen species production | (97) | |

| Mixed cortical cell cultures | Serum-free EMEM | BDNF 100 ng/ml | The role of NADPH oxidase in oxidative neuronal death induced in cortical cultures by BDNF | (98) |

H/I, hypoxia-ischemia; SD, Sprague Dawley; CBD-BDNF, collagen-binding BDNF; HBO, hyperbaric oxygen; ICV, intracerebroventricular injection; LBD-BDNF, laminin-binding domain to BDNF construct laminin-binding BDNF; MCA, middle cerebral artery; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion model; TCE, Terminalia chebula Retz seeds; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinases; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; CREB, cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein; EMEM, Eagle’s minimal essential medium; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

Anti-epilepsy

Various studies have demonstrated that BDNF contributes to epileptogenesis (78). For example, mesio-temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE) was significantly aggravated in mice with increased TrkB signals, but delayed in mutant mice with reduced TrkB signals. Paradoxically, with respect to temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), previous studies have demonstrated that BDNF-induced Trk activation may lead to neuropeptide Y (NPY) upregulation, while NPY-knockout animals are more susceptible to seizures. Therefore, intrahippocampal infusion of BDNF potentially attenuates (or retards) the development of epilepsy (79).

Contributions to cognitive functions and memory acquisition

Cerebral ischemia may lead to a progressive global cognitive deterioration. The involvement of BDNF in cognitive functions, particularly in memory acquisition and consolidation is highly attractive.

BDNF is essential for NSC-induced cognitive rescue, which has been observed in aged 3x transgenic Alzheimer’s disease (Tg-AD) mice with spatial learning and memory deficiencies. Gain-of-function studies demonstrated that recombinant BDNF mimics might have beneficial effects on NSC transplantation, while loss-of-function studies showed that mice depleted of NSC-derived BDNF failed to improve cognition or restore hippocampal synaptic density (80). To investigate the effect of BDNF on hippocampal cognitive functions after global cerebral ischemia in rats, BDNF was administered continuously over 14 days via an osmotic mini-pump, intracerebroventricularly after four-vessel occlusion. Cognitive impairment was also assessed repeatedly using a passive avoidance test. In ischemic animals treated with BDNF, the working and reference memory ratios 15 days after ischemia were lower in the ischemic rats. These data indicate a protective effect of BDNF for synaptic transmission and cognitive functions after transient forebrain ischemia (81).

Furthermore, voluntary exercise upregulates BDNF within the hippocampus, inducing improvements in cognitive performance after traumatic brain injury in rats (82).

With regard to the function of memory, BDNF has been known to induce memory persistence, and convert a non-lasting long-term memory (LTM) trace into a persistent one. When BDNF gene expression in the hippocampus was inhibited, a deficiency of memory formation was observed (83).

5. Applications and challenges

While designing treatment strategies aimed at improving stroke recovery, greater attention should be paid to non-neuronal cells which are able to produce substantial amounts of BDNF after ischemic stroke. Evidence has shown that ischemic stroke in rats results in increased BDNF staining in neurons and ependymal cells in the non-lesioned hemisphere. Similarly, in the lesioned hemisphere, microglial and endothelial cells of cerebral arterioles and astrocytes also exhibit robust BDNF staining (18).

Transposition of BDNF to the target injury regions is a challenge in clinical applications, while a short half-life and a low rate of transport through the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is hampered. Such problems may be solved in various ways.

First, by fusing a laminin-binding domain (LBD) to BDNF a laminin-binding BDNF (LBD-BDNF) form is constructed, since laminin is a rich extracellular matrix in the CNS, and is highly expressed in ischemic regions. LBD-BDNF is associated with a parallel improvement in neurological functional outcomes, and effectively attenuates neural degeneration after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats (86). Similarly, injection of CBD-BDNF in the ventricle remained stable for much longer compared to mature BDNF, while the CBD-BDNF concentrated at the infarcted hemisphere and exerted a more enduring therapeutic effect (96).

Second, the problem may also be resolved by improving BDNF delivery into the target region. Studies have suggested the intranasal access to potentially be effective when delivering BDNF to the target region. Elevated concentration of BDNF in brain tissues following intranasal delivery can reach 4 ng/g, as opposed to only 0.2 ng/g in the controls (60).

Third, BDNF mimetics may also be used to overcome the therapeutic challenges. Based on a loop domain of BDNF that binds to a key receptor of TrkB, pharmacophores were generated. Four candidate molecules designated as LM22A1-LM22A4 were selected. In mouse hippocampal neuronal cultures, these compounds promoted cell survival with an efficacy comparable to that of BDNF. Of note, unlike BDNF, LM22A4 did not bind to the receptor p75, which is considered to mediate the pain-promoting effects of BDNF. Furthermore, LM22A4 was considered suitable for intranasal administration to mice. Once-daily dosing of this compound for 7 days in in vivo experiments, not only increased the activation of TrkB in the hippocampus and striatum, but also significantly improved the impairment in motor learning, following traumatic brain injury. Such mimetics provide a promising new approach to the application of BDNF in the treatment of H/I injury (99).

6. Conclusion

During the last decade, the neuroprotective effects of BDNF, its underlying mechanisms and signal transductions have been investigated. Evidence from in vitro studies as well as animal models have demonstrated that BDNF is a potential novel candidate of defence against ischemia brain injury. However, since the signalling pathway is complicated and bidirectional, application of BDNF in neuroprotection in humans remains to be elucidated. Therefore, additional studies focusing on BDNF, its mechanisms or application, need to be conducted in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 30973215) and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (No.IRT 0935).

Abbreviations:

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor;

- HI

hypoxia-ischemia;

- HIBD

hypoxia-ischemia brain damage;

- HIE

hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy;

- EPO

erythropoietin;

- NGF

nerve growth factor;

- NT

neurotrophins;

- MMP7

metalloproteinase gene matrilysin;

- TGN

trans-Golgi network;

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus;

- VMN

ventromedial nucleus;

- DMN

dorsomedial nucleus;

- LH

lateral hypothalamic area;

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism;

- Val

valine;

- Met

methionine;

- TrkA

kinase receptor type A;

- TrkB

kinase receptor type B;

- TrkC

kinase receptor type C;

- CNS

central nerve system;

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase;

- PI-3K

phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase;

- PLCγ

phospholipase C γ;

- c-Jun

c-Jun kinase;

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells;

- PKC

protein kinase C;

- IP3

inositol trisphosphate;

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor receptor;

- CD

cortical devascularization;

- CPE

carboxypeptidase E;

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin;

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinases;

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein;

- NCM

neuron-conditioned media;

- NSCs

neural stem cells;

- IM

imipramine;

- EAA

excitatory amino acids;

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor;

- PVL

periventricular leukomalacia;

- MTLE

mesio-temporal lobe epilepsy;

- TLE

temporal lobe epilepsy;

- NPY

neuropeptide Y;

- LTM

non-lasting long-term memory;

- BBB

blood-brain barrier;

- LBD-BDNF

laminin-binding BDNF;

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate;

- EMEM

Eagle’s minimal essential medium

References

- 1.Xiong T, Qu Y, Mu D, Ferriero D. Erythropoietin for neonatal brain injury: opportunity and challenge. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levi-Montalcini R. The nerve growth factor 35 years later. Science. 1987;237:1154–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.3306916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotz R, Koster R, Winkler C, et al. Neurotrophin-6 is a new member of the nerve growth factor family. Nature. 1994;372:266–269. doi: 10.1038/372266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lessmann V, Brigadski T. Mechanisms, locations, and kinetics of synaptic BDNF secretion: an update. Neurosci Res. 2009;65:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Siao CJ, Nagappan G, et al. Neuronal release of proBDNF. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:113–115. doi: 10.1038/nn.2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mowla SJ, Farhadi HF, Pareek S, et al. Biosynthesis and post-translational processing of the precursor to brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12660–12666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu B. Pro-region of neurotrophins: role in synaptic modulation. Neuron. 2003;39:735–738. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00538-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pang PT, Teng HK, Zaitsev E, et al. Cleavage of proBDNF by tPA/plasmin is essential for long-term hippocampal plasticity. Science. 2004;306:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.1100135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee R, Kermani P, Teng KK, Hempstead BL. Regulation of cell survival by secreted proneurotrophins. Science. 2001;294:1945–1948. doi: 10.1126/science.1065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Pareek S, Chretien M, Murphy RA. Cellular processing of the neurotrophin precursors of NT3 and BDNF by the mammalian proprotein convertases. FEBS Lett. 1996;379:247–250. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman LJ, Valverde J, Lim F, et al. Regulated release and polarized localization of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in hippocampal neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;7:222–238. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas K, Davies A. Neurotrophins: a ticket to ride for BDNF. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R262–R264. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boutilier J, Ceni C, Pagdala PC, Forgie A, Neet KE, Barker PA. Proneurotrophins require endocytosis and intracellular proteolysis to induce TrkA activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12709–12716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710018200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen ZY, Bath K, McEwen B, Hempstead B, Lee F. Impact of genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) on brain structure and function. Novartis Found Symp. 2008;289:180–195. doi: 10.1002/9780470751251.ch14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu H, Chen ZY. The role of BDNF in depression on the basis of its location in the neural circuitry. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32:3–11. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tapia-Arancibia L, Rage F, Givalois L, Arancibia S. Physiology of BDNF: focus on hypothalamic function. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2004;25:77–107. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto H, Gurney ME. Human platelets contain brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3469–3478. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03469.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bejot Y, Prigent-Tessier A, Cachia C, et al. Time-dependent contribution of non neuronal cells to BDNF production after ischemic stroke in rats. Neurochem Int. 2011;58:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassiman D, Denef C, Desmet VJ, Roskams T. Human and rat hepatic stellate cells express neurotrophins and neurotrophin-receptors. Hepatology. 2001;33:148–158. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.20793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aid T, Kazantseva A, Piirsoo M, Palm K, Timmusk T. Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:525–535. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pruunsild P, Kazantseva A, Aid T, Palm K, Timmusk T. Dissecting the human BDNF locus: bidirectional transcription, complex splicing, and multiple promoters. Genomics. 2007;90:397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Givalois L, Marmigere F, Rage F, Ixart G, Arancibia S, Tapia-Arancibia L. Immobilization stress rapidly and differentially modulates BDNF and TrkB mRNA expression in the pituitary gland of adult male rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;74:148–159. doi: 10.1159/000054681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tongiorgi E, Baj G. Functions and mechanisms of BDNF mRNA trafficking. Novartis Found Symp. 2008;289:136–195. doi: 10.1002/9780470751251.ch11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenberg ME, Xu B, Lu B, Hempstead BL. New insights in the biology of BDNF synthesis and release: implications in CNS function. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12764–12767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3566-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teng HK, Teng KK, Lee R, et al. ProBDNF induces neuronal apoptosis via activation of a receptor complex of p75NTRand sortilin. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5455–5463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5123-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massa SM, Yang T, Xie Y, et al. Small molecule BDNF mimetics activate TrkB signaling and prevent neuronal degeneration in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1774–1785. doi: 10.1172/JCI41356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Numakawa T, Suzuki S, Kumamaru E, Adachi N, Richards M, Kunugi H. BDNF function and intracellular signaling in neurons. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25:237–258. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han BH, D’Costa A, Back SA, et al. BDNF blocks caspase-3 activation in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:38–53. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen AI, Nguyen CN, Copenhagen DR, et al. TrkB (tropomyosin-related kinase B) controls the assembly and maintenance of GABAergic synapses in the cerebellar cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2769–2780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4991-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong J, Woon HG, Weickert CS. Full length TrkB potentiates estrogen receptor alpha mediated transcription suggesting convergence of susceptibility pathways in schizophrenia. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luberg K, Wong J, Weickert CS, Timmusk T. Human TrkB gene: novel alternative transcripts, protein isoforms and expression pattern in the prefrontal cerebral cortex during postnatal development. J Neurochem. 2010;113:952–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zampieri N, Chao MV. Mechanisms of neurotrophin receptor signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:607–611. doi: 10.1042/BST0340607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skaper SD, Floreani M, Negro A, Facci L, Giusti P. Neurotrophins rescue cerebellar granule neurons from oxidative stress-mediated apoptotic death: selective involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and themitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1859–1868. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70051859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:609–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lessmann V, Gottmann K, Malcangio M. Neurotrophin secretion: current facts and future prospects. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69:341–374. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han BH, Holtzman DM. BDNF protects the neonatal brain from hypoxic-ischemic injury in vivo via the ERK pathway. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5775–5781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05775.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun X, Zhou H, Luo X, et al. Neuroprotection of brain-derived neurotrophic factor against hypoxic injury in vitro requires activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2008;26:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amaral MD, Pozzo-Miller L. BDNF induces calcium elevations associated with IBDNF, a nonselective cationic current mediated by TRPC channels. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:2476–2482. doi: 10.1152/jn.00797.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angelo MF, Aviles-Reyes RX, Villarreal A, Barker P, Reines AG, Ramos AJ. p75 NTR expression is induced in isolated neurons of the penumbra after ischemia by cortical devascularization. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1892–1903. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dechant G, Barde YA. The neurotrophin receptor p75(NTR): novel functions and implications for diseases of the nervous system. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1131–1136. doi: 10.1038/nn1102-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho R, Minturn JE, Simpson AM, et al. The effect of P75 on Trk receptors in neuroblastomas. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kenchappa RS, Tep C, Korade Z, et al. p75 neurotrophin receptor-mediated apoptosis in sympathetic neurons involves abiphasic activation of JNK and up-regulation of tumor necrosisfactor-alpha-converting enzyme/ADAM17. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20358–20368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.082834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schecterson LC, Bothwell M. Neurotrophin receptors: old friends with new partners. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70:332–338. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lou H, Kim SK, Zaitsev E, Snell CR, Lu B, Loh YP. Sorting and activity-dependent secretion of BDNF require interaction of aspecific motif with the sorting receptor carboxypeptidase e. Neuron. 2005;45:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lou H, Park JJ, Cawley NX, et al. Carboxypeptidase E cytoplasmic tail mediates localization of synaptic vesicles to the pre-active zone in hypothalamic pre-synaptic terminals. J Neurochem. 2010;114:886–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuczewski N, Porcher C, Lessmann V, Medina I, Gaiarsa JL. Activity-dependent dendritic release of BDNF and biological consequences. Mol Neurobiol. 2009;39:37–49. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8050-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pallesen LT, Vaegter CB. Sortilin and SorLA regulate neuronal sorting of trophic and dementia-linked proteins. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;45:379–387. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evans SF, Irmady K, Ostrow K, et al. Neuronal brain-derived neurotrophic factor is synthesized in excess, with levels regulated by sortilin-mediated trafficking and lysosomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29556–29567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shah PS, Ohlsson A, Perlman M. Hypothermia to treat neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:951–958. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.10.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chalak LF, Rollins N, Morriss MC, Brion LP, Heyne R, Sanchez PJ. Perinatal acidosis and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in preterm infants of 33 to 35 weeks’ gestation. J Pediatr. 2012;160:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szydlowska K, Tymianski M. Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Yu Z, Yu Z, et al. rAAV-mediated delivery of brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes neurite outgrowth and protects neurodegeneration in focal ischemic model. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011;4:496–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Z, Ma D, Feng G, Ma Y, Hu H. Recombinant AAV-mediated expression of human BDNF protects neurons against cell apoptosis in Abeta-induced neuronal damage model. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2007;27:233–236. doi: 10.1007/s11596-007-0304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takeshima Y, Nakamura M, Miyake H, et al. Neuroprotection with intraventricular brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rat venous occlusion model. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:1334–1341. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31820c048e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kiprianova I, Freiman TM, Desiderato S, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevents neuronal death and glial activation after global ischemia in the rat. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56:21–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990401)56:1<21::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kurokawa T, Katai N, Shibuki H, et al. BDNF diminishes caspase-2 but not c-Jun immunoreactivity of neurons in retinal-ganglion cell layer after transient ischemia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:3006–3011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neumann J, Gunzer M, Gutzeit HO, Ullrich O, Reymann KG, Dinkel K. Microglia provide neuroprotection after ischemia. FASEB J. 2006;20:714–716. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4882fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lai AY, Todd KG. Differential regulation of trophic and proinflammatory microglial effectors is dependent on severity of neuronal injury. Glia. 2008;56:259–270. doi: 10.1002/glia.20610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang J, Geula C, Lu C, Koziel H, Hatcher LM, Roisen FJ. Neurotrophins regulate proliferation and survival of two microglial cell lines in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2003;183:469–481. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang Y, Wei N, Lu T, Zhu J, Xu G, Liu X. Intranasal brain-derived neurotrophic factor protects brain from ischemic insult via modulating local inflammation in rats. Neuroscience. 2011;172:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakajima K, Kohsaka S. Microglia: neuroprotective and neurotrophic cells in the central nervous system. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2004;4:65–84. doi: 10.2174/1568006043481284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCoy MK, Tansey MG. TNF signaling inhibition in the CNS: implications for normal brain function and neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frenkel D, Pachori AS, Zhang L, et al. Nasal vaccination with troponin reduces troponin specific T-cell responses and improves heart function in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int Immunol. 2009;21:817–829. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peng CH, Chiou SH, Chen SJ, et al. Neuroprotection by Imipramine against lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis in hippocampus-derived neural stem cells mediated by activation of BDNF and the MAPK pathway. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Casalbore P, Barone I, Felsani A, et al. Neural stem cells modified to express BDNF antagonize trimethyltin-induced neurotoxicity through PI3K/Akt and MAP kinase pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224:710–721. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakai R, Ukai W, Sohma H, et al. Attenuation of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) by ethanol and cytoprotective effect of exogenous BDNF against ethanol damage in neuronal cells. J Neural Transm. 2005;112:1005–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kume T, Kouchiyama H, Kaneko S, et al. BDNF prevents NO mediated glutamate cytotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons. Brain Res. 1997;756:200–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Endres M, Dirnagl U, Moskowitz MA. The ischemic cascade and mediators of ischemic injury. Handb Clin Neurol. 2009;92:31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(08)01902-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Akaike A, Katsuki H, Kume T, Maeda T. Reactive oxygen species in NMDA receptor-mediated glutamate neurotoxicity. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 1999;5:203–207. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(99)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Crozier RA, Bi C, Han YR, Plummer MR. BDNF modulation of NMDA receptors is activity-dependent. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:3264–3274. doi: 10.1152/jn.90418.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Georgiev DD, Taniura H, Kambe Y, Yoneda Y. Crosstalk between brain-derived neurotrophic factor and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor signaling in neurons. Biomed Rev. 2008;19:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu JM, Zhao YY, Chen SD, Zhang WH, Lou L, Jin X. Functional recovery after transplantation of neural stem cells modified by brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rats with cerebral ischaemia. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:488–498. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Horch HW, Kruttgen A, Portbury SD, Katz LC. Destabilization of cortical dendrites and spines by BDNF. Neuron. 1999;23:353–364. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80785-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schabitz WR, Berger C, Kollmar R, et al. Effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor treatment and forced arm use on functional motor recovery after small cortical ischemia. Stroke. 2004;35:992–997. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000119754.85848.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lopatina T, Kalinina N, Karagyaur M, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells stimulate regeneration of peripheral nerves: BDNF secreted by these cells promotes nerve healing and axon growth de novo. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnston MV, Trescher WH, Ishida A, Nakajima W. Neurobiology of hypoxic-ischemic injury in the developing brain. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:735–741. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Husson I, Rangon CM, Lelievre V, et al. BDNF-induced white matter neuroprotection and stage-dependent neuronal survival following a neonatal excitotoxic challenge. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:250–261. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Binder DK. The role of BDNF in epilepsy and other diseases of the mature nervous system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;548:34–56. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-6376-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Binder DK, Croll SD, Gall CM, Scharfman HE. BDNF and epilepsy: too much of a good thing. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01682-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blurton-Jones M, Kitazawa M, Martinez-Coria H, et al. Neural stem cells improve cognition via BDNF in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13594–13599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901402106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kiprianova I, Sandkuhler J, Schwab S, Hoyer S, Spranger M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor improves long-term potentiation and cognitive functions after transient forebrain ischemia in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1999;159:511–519. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Griesbach GS, Hovda DA, Gomez-Pinilla F. Exercise-induced improvement in cognitive performance after traumatic brain injury in rats is dependent on BDNF activation. Brain Res. 2009;1288:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Katche C, et al. BDNF is essential to promote persistence of long-term memory storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2711–2716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711863105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kubo T, Nonomura T, Enokido Y, Hatanaka H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) can prevent apoptosis of rat cerebellar granule neurons in culture. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1995;85:249–258. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00220-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bhave SV, Ghoda L, Hoffman PL. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mediates the anti-apoptotic effect of NMDA in cerebellar granule neurons: signal transduction cascades and site of ethanol action. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3277–3286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03277.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Han Q, Li B, Feng H, et al. The promotion of cerebral ischemia recovery in rats by laminin-binding BDNF. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5077–5085. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhou H, Mao M, Liu W, Li S, Wang H. Expression of BDNF Receptor TrkBmRNA in hypoxia-induced fetal cortical neurons. J West China Univ Med Sci. 2002;33:573–576. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Luo XL, Mao M, Zhou H, Sun XM, Li SF. Neuroprotective effect of BDNF on hypoxia for embryonic rat cortical neurons in vitro. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2006;37:373–377. (In Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meng M, Zhiling W, Hui Z, Shengfu L, Dan Y, Jiping H. Cellular levels of TrkB and MAPK in the neuroprotective role of BDNF for embryonic rat cortical neurons against hypoxia in vitro. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meng M, Dan Y, Jie Z, Hui Z, Zhiling W. Effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on apoptosis of embryo brain suffered from intrauterine hypoxic-ischemic injury. J Appl Clin Pediatr. 2004;19:1062–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ostrowski RP, Graupner G, Titova E, et al. The hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning-induced brain protection is mediated by a reduction of early apoptosis after transient global cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Park JH, Joo HS, Yoo KY, et al. Extract from Terminalia chebula seeds protect against experimental ischemic neuronal damage via maintaining SODs and BDNF levels. Neurochem Res. 2011;36:2043–2050. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee CH, Park JH, Yoo KY, et al. Pre- and post-treatments with escitalopram protect against experimental ischemic neuronal damage via regulation of BDNF expression and oxidative stress. Exp Neurol. 2011;229:450–459. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu W, Sun X, Zhou H, Luo X, Mao M. Correlation of a protective effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on hypoxic neurons to extracellular signal-regulated kinase. J Clin Rehabil Tissue Eng Res. 2008;12:3884–3888. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Alcala-Barraza SR, Lee MS, Hanson LR, McDonald AA, Frey WH, II, McLoon LK. Intranasal delivery of neurotrophic factors BDNF, CNTF, EPO, and NT-4 to the CNS. J Drug Target. 2010;18:179–190. doi: 10.3109/10611860903318134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Guan J, Tong W, Ding W, et al. Neuronal regeneration and protection by collagen-binding BDNF in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1386–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim SH, Won SJ, Sohn S, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor can act as a pronecrotic factor through transcriptional and translational activation of NADPH oxidase. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:821–831. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hwang JJ, Choi SY, Koh JY. The role of NADPH oxidase, neuronal nitric oxide synthase and poly(ADP ribose) polymerase in oxidative neuronal death induced in cortical cultures by brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-4/5. J Neurochem. 2002;82:894–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kingwell K. Neurodegenerative disease: BDNF copycats. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:433. doi: 10.1038/nrd3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]