Abstract

In the science-fiction thriller film Minority Report, a specialized police department called “PreCrime” apprehends criminals identified in advance based on foreknowledge provided by 3 genetically altered humans called “PreCogs”. We propose that Yamanaka stem cell technology can be similarly used to (epi)genetically reprogram tumor cells obtained directly from cancer patients and create self-evolving personalized translational platforms to foresee the evolutionary trajectory of individual tumors. This strategy yields a large stem cell population and captures the cancer genome of an affected individual, i.e., the PreCog-induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cancer cells, which are immediately available for experimental manipulation, including pharmacological screening for personalized “stemotoxic” cancer drugs. The PreCog-iPS cancer cells will re-differentiate upon orthotopic injection into the corresponding target tissues of immunodeficient mice (i.e., the PreCrime-iPS mouse avatars), and this in vivo model will run through specific cancer stages to directly explore their biological properties for drug screening, diagnosis, and personalized treatment in individual patients. The PreCog/PreCrime-iPS approach can perform sets of comparisons to directly observe changes in the cancer-iPS cell line vs. a normal iPS cell line derived from the same human genetic background. Genome editing of PreCog-iPS cells could create translational platforms to directly investigate the link between genomic expression changes and cellular malignization that is largely free from genetic and epigenetic noise and provide proof-of-principle evidence for cutting-edge “chromosome therapies” aimed against cancer aneuploidy. We might infer the epigenetic marks that correct the tumorigenic nature of the reprogrammed cancer cell population and normalize the malignant phenotype in vivo. Genetically engineered models of conditionally reprogrammable mice to transiently express the Yamanaka stemness factors following the activation of phenotypic copies of specific cancer diseases might crucially evaluate a “reprogramming cure” for cancer. A new era of xenopatients 2.0 generated via nuclear reprogramming of the epigenetic landscapes of patient-derived cancer genomes might revolutionize the current personalized translational platforms in cancer research.

Keywords: reprogramming, stem cells, cancer stem cells, differentiation, iPS cells, Yamanaka, mouse avatars, xenografts, epigenetic landscape

In the Steven Spielberg’s 2002 neo-noir science-fiction thriller film Minority Report, a specialized police department called PreCrime apprehends criminals based on foreknowledge provided by 3 genetically altered humans called PreCogs. The 3 PreCogs have a vision, and the names of the victim and perpetrator, video imagery of the crime, and the exact time of occurrence are provided to the elite law enforcing squad, PreCrime, who are dispatched to arrest the predicted killer and prevent the crime. The system is successful, with no murders occurring in the city after the system is inaugurated. If we could similarly engineer state-of-the-art tools to forecast the appearance of biological properties and cellular features that are not apparent in clinically detectable stages, we could use cancer samples that are isolated for the assessment of prognostic and predictive biomarkers to see into the future of individual tumors to molecularly anticipate and therapeutically prevent their undesirable killing activity. The Minority Report’s PreCog-like software to predict crimes is being tested, and the 3D screens imagined in that fictional world have become a reality. Unfortunately, our current ability to foresee the evolutionary trajectory of any individual cancer remains in its infancy.

We propose that the commonly forgotten appreciation of Bond et al.1 over a decade ago that “dedifferentiation accompanying malignant progression in cancer may play a causal rather than a passive role in the critical tumor-behavior-switch from well-differentiated to highly aggressive form” must be revisited in light of the 2012 Nobel Prize Yamanaka’s induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell technology,2,3 which provided the missing evidence that most, if not all, somatic mammalian cells possess dedifferentiation potential. Reprogramming cancer cells obtained directly from primary tumors in individual patients can create live-cell developmental windows that could operate as new, self-evolving personalized models of cancer disease. Personalized translational platforms to foresee the evolutionary trajectory of individual tumors can be generated using in vitro-generated PreCog-iPS cells directly reprogrammed from patient-derived tumor cells and their in vivo PreCrime-mouse avatar derivatives obtained in immunodeficient mice following orthotopic injection of PreCog-iPS at the same location where the primary tumor was formed.

Understanding cancer as a disease of reprogramming and differentiation

Two predominant models have emerged to explain phenotypic and functional heterogeneity in human tumors.4 The so-called “stochastic” or “clonal evolution” model is based on classic theories of the selection of mutants that are fit to survive in particular environments. Stochastic mutations in an appropriate cell type are selected if the cells possess a survival or proliferative advantage. This selected cell subsequently grows, and succeeding mutations in descendants yield a tumor with numerous mutations. However, only some of the mutations are selected for the advantages they provide (“drivers”); the other mutations are “passengers”. Tumor heterogeneity in this model depends on the constellation of mutations and the phenotypes they generate; accordingly, deep sequencing analyses have revealed that different tumor types differ significantly in terms of their mutation load and the existence of multiple clones within each tumor mass.5-7 A second model is largely based on the principles of stem cell biology.8-10 Carcinogenesis involves the accumulation of numerous mutagenic events over long time periods, but only normal stem cells with innate self-renewal capacity might remain in the tissue for a sufficiently long time to accumulate the oncogenic alterations that are necessary to support a complete transformation. Adult stem cells may represent the cells of origin in tumors that originate from tissues with high epithelial turnover, because they can be directly targeted with cancer stem cell (CSC) initiation events (i.e., CSCs directly arise from the malignant transformation of adult stem cells). More committed progenitors may acquire mutations and/or epigenetic changes that confer the ectopic capacity for perpetual self-renewal of CSCs. All cancer cells within a tumor arise from special self-renewing CSCs in this traditional view of one-way CSC hierarchy, and, consequently, cellular heterogeneity results from a CSC undergoing aberrant differentiation to form the pathologically recognized disorganized mass. Tumors are an aberration of the stem cell-driven mechanisms that govern the normal development of the corresponding tissue. Some tumors contain mixtures of very immature-appearing cells mixed with more differentiated cells with a subpopulation of cells bearing the so-called “CSC markers” that can regenerate whole tumors in xenografts (i.e., tumor-initiating cells) with the cellular heterogeneity of the original mass.8-13

CSCs obviously exhibit stem cell-like properties, but these cells do not necessarily originate from the direct transformation of normal tissue stem cells or progenitor cells. CSCs are also made and not just born; individual tumors generally harbor multiple phenotypically or genetically distinct CSCs, because differentiated normal or non-stem cell tumor cells gain CSC cellular properties via the activation of partially known paths to stemness.14-23 Critically, “stemness” is an emergent dynamicl state rather than the direct consequence of the activity of a particular stemness gene or a set of stemness genes. The CSC cellular state continuously evolves, and it can be switched on or off in response to cell-intrinsic or microenvironmental cues, including therapeutics. Moreover, a subset of CSCs may be exclusively responsible for metastatic spread, which is the final step in 90% of all fatal solid tumors. If an initial genetic defect in multi-potent stem cells is not the sole mechanism for the generation of dynamically evolving CSC reservoirs, then primary CSCs are not necessarily identical to metastatic CSCs. In this scenario, a more accurate description of the complex events that occur during tumor progression requires the incorporation of the potential for “cellular reprogramming” with the stochastic and CSC models.24-30 Cancer, cellular plasticity, and cell fate reprogramming are highly intertwined processes considering that not all cancer cells possess the necessary ability to permit their reprogramming to CSC “cellular states”, and only some cancer genes (e.g., reprogramming stemness factors) possess the required capacity to fully elicit the reprogramming process in the right spatiotemporal context. This novel composite model of stem cell state acquisition envisions cancer as a disease that primarily involves cellular differentiation, and in which the many driving forces of the tumorigenic process, including the loss of pivotal tumor suppressors, such as aberrant transcription factors, signaling cascades, or epigenetic regulators, play a permissive role in tumoral progression by alleviating the developmentally unfavorable process of gaining tumor-initiating and/or metastasis-initiating capabilities. The commonly observed p53 functional inactivation, which is particularly concentrated in tumors exhibiting plasticity and a loss of differentiation characteristics, is generally attributed to survival benefits due to reduced apoptotic cell death, cell cycle arrest, and augmented opportunities for cancer cell evolution afforded by genomic instability. However, ever-growing evidence supports the hypothesis that p53 inactivation may destabilize the differentiated state and enable reversion to a more stem-like cellular state in the presence of appropriate oncogenic lesions.20,31-34

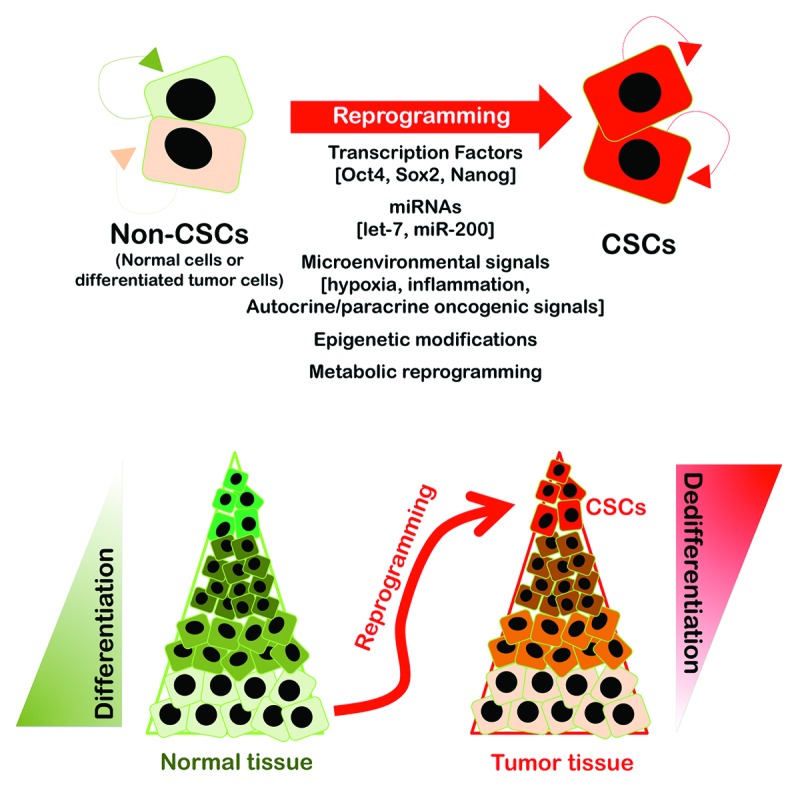

If cancer is viewed as a disease of reprogramming and differentiation, cells with stem-like properties could be generated at any time during cancer progression so long as tumor suppressors, such as p53 (or other factors with the p53 function), are hindered, and appropriate oncogenic lesions that can enable epigenetic reprogramming to a stem-like cellular state are present. The plasticity potential of non-CSCs to acquire a CSC cellular state depending on their (epi)genetic state and/or interpretation of the microenvironmental in the absence or presence of stress (e.g., hypoxia, glucose deprivation, and chemotherapy) is not contemplated in the conventional depiction of the stem/progenitor cell hierarchy within a normal tissue being transformed into a similar one-way CSC hierarchy, and this concept is changing our current perception of CSC biology (Fig. 1). Tumorigenesis can be initiated and maintained by stem cell reprogramming, which is a molecular process by which cancer genetic alterations reset the epigenetic and transcriptional status of an initially healthy cell (i.e., the cancer cell of origin) and establish a newly acquired, pathological differentiation program of aberrant stemness that ultimately leads to cancer development. In addition, differentiated cancer cells may dynamically alter their transcriptional and epigenetic circuits to rewire into stem-like cells and refuel cancer growth by activating specific transcription factor drivers and modulating some collaborating chromatin regulators. These dynamic bidirectional transitions could provide a unifying view of cellular organization within tumors, because the same network of key regulators that contribute to transformation and cell state transitions to establish an epigenetic hierarchy within rare CSC populations give rise to a more differentiated cellular progeny (i.e., oncogenic reprogramming) that may also act within the established tumor to redirect differentiated tumor cells toward a less differentiated and stem-like cellular state and establish a dynamic equilibrium between reprogramming and differentiation.30 Multiple independently derived and molecularly distinct stem-like clones could evolve depending on the likelihood of reprogramming within tumors. Some genetically and epigenetically unstable pools of CSCs might initiate or continue their clonal growth depending on the level and nature of oncogenic stimuli and in response to dissimilar local microenvironments. Other CSCs might remain dormant until appropriate signals are received, such as aberrant microenvironments created within tumors, which might influence the type of CSCs that arise from related but genetically distinct and independently propagating cancer cell clones. This complex scenario might explain the appearance of multiple clonal lineages within tumors that have been identified using single-cell sequencing.7 The resulting heterogeneity may manifest as diverse CSC states that vary in terms of their proliferative, biomarker, and chemosensitivity profiles.35

Figure 1. Cancer is a disease of reprogramming and differentiation. Recent findings from multiple laboratories haven shown that normal cells and the bulk population of tumor cells that display low self-renewal capacity and a higher probability of terminal differentiation have the capacity to dedifferentiate and acquire a cancer stem-like (self-renewing, multipotent, high tumor propagating, and chemo/radio-resistant) cellular state in response to either genetic manipulation or environmental cues. Normal cells and differentiated cancer cells can acquire stem-like cellular states by several inducers of dedifferentiation mechanisms, including transcriptional networks involving key transcription factors (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Nanog), miRNAs (e.g., let-7, miR-200 family), microenvironmental signals (e.g., hypoxia, inflammation, autocrine/paracrine oncogenic signaling pathways), epigenetic modifications (e.g., DNA demethylation, histone acetylation/methylation), and metabolic reprogramming. These findings from a diverse array of experimental models, along with correlative clinical data, strongly support that cancer stemness is an emergent dynamical state rather than the direct consequence of the activity of a particular stemness gene or a set of stemness genes in cancer tissues. The so-called CSCs should be viewed as multiple evolutionary selected cancer cells with the most competitive properties at some time (e.g., immortality, dormancy, chemo- or radio-resistance, motility, etc.) reversibly maintained by (epi)genetic mechanisms that result from a stochastic rather than a deterministic process.89-92

Remarkably, the reprogramming-differentiation model of cancer formation and evolution explains many of the apparently paradoxical aspects of tumor biology: (1) the difficulty in the reconciliation of the rarity (of CSC numbers) with robustness (of CSC properties) to some tumors; (2) the difficulty in the application of hierarchical models to some tumors, such as metastatic melanoma, which is one of the most aggressive, treatment-resistant human carcinomas that does not follow the CSC hierarchy36 and likely represents an extreme example in which certain genetic make-ups allow for easy conversion between non-CSC and CSC states to endow almost the entire tumor cell population with CSC qualities; (3) the lack of CSC markers that enable the general identification of stemness in a given tumor and the enormous plasticity of numerous putative CSCs;37-39 indeed, a common molecular genetic program for CSCs has remained largely elusive even within the same type of carcinoma, and fewer chromosomal aberrations are observed in disseminated CSCs, which occur at earlier stages of tumor development than previously thought; and (4) the occurrence of unique stem-like states due to the continuous evolution and adaptation to new constraints, such as microenvironmental stresses or therapeutics, which might explain the ability of some tumor cells to transdifferentiate into functional vascular–endothelial cells that resist antiangiogenic therapy,40 exhibit remarkable plasticity in chemoresistance (i.e., individual cells can transiently assume a reversibly drug-tolerant state to protect the population from eradication due to potentially lethal exposures),41 and migrate and metastasize in response to dynamic interactions among epithelial, self-renewal, and mesenchymal gene programs that determine the plasticity of epithelial CSCs. Molecular heterogeneity and stochasticity of gene expression may drive a continuum of cancer cell states co-expressing stem cells and lineage-specific genes to encourage a greater likelihood of entering a CSC-like state, which may counterintuitively occur in response to the equilibrium between differentiation potentials.42-44

Yamanaka stem cell technology for the recovery or foreseeing the evolutionary trajectory of individual cancers

PreCog-iPS cells and PreCrime-mouse avatars

A key corollary of the above-mentioned model of reprogramming–differentiation during cancer formation and evolution is that differentiated somatic (non-cancerous and cancerous) cells are sufficiently plastic to aberrantly reprogram and acquire CSC properties. Therefore, tumor-associated reprogramming might be sufficient to generate aberrant but robust stem-like cellular states. Bond et al. pioneeringly suggested that the apparent “dedifferentiation” accompanying malignant progression played a causal rather than passive role in tumor behavior.1 However, since then, most cancer researchers have adopted an alternative view, in which tumors adhere to essentially irreversible hierarchies of cellular differentiation in parallel to normal tissues. Moreover, there is little compelling experimental evidence to directly support the potential for cellular dedifferentiation in mammalian cells. However, Takahashi and Yamanaka demonstrated that the forced expression of 4 transcription factors, namely, Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc, induced mouse fibroblasts to adopt pluripotent cell fates that resembled stem cells.2,3 These and subsequent studies demonstrated that virtually all cell types can generate induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells when the appropriate reprogramming gene sets are used, which supports the hypothesis that most, if not all, somatic mammalian cells possess dedifferentiation potential and confirms the inherent reversibility of the steps of cellular differentiation. The fact that several reprogramming transcription factors represent bona fide oncogenes, whereas many genes that act as barriers to nuclear reprogramming correspond to known tumor suppressors (e.g., p53),45-50 strongly suggests that the necessary epigenetic rewiring for cellular reprogramming may be partially recapitulated during cellular transformation. Accordingly, the use of an iPS cell expression signature comprised of genes that are consistently upregulated in independent studies with iPS cultures has revealed significant similarities between p53-mutated cancers and cells that have undergone intentional reprogramming in vivo.51-55 The frequency of reprogramming appeared to be extremely low; the occurrence of cellular barriers against induced reprogramming supports the feasibility of resetting the epigenetic architecture of any differentiated cell to resemble a stem cell, perhaps not perfectly, because the tumor-associated reprogramming of p53-deficient, oncogene-expressing cells might generate aberrant stem-like cellular states that phenocopy fetal stem cells or iPS cells.

CSCs are unlikely to arise by the “invention” of completely novel biology in a molecular scenario in which cellular reprogramming is a natural, highly plastic phenomenon that allows stemness to emerge and diversify in the tumorigenic context. Therefore, the mechanisms of CSC generation and evolution are not fully amenable to analysis using commonly employed patient samples, because these tumors can only be studied after the transformation events have occurred. Moreover, reversible and transient modifications, rather than the accumulation of irreversible and stable modifications, primarily regulate the key events that govern the acquisition of CSC-like cellular states. The appearance of biological properties and cellular features are not apparent in clinically detectable tumors, and the cancer samples that are isolated for routine assessment of prognostic and predictive biomarkers impose significant challenges. The disaggregation of the tumor mass for analyses may obscure the initially present local heterogeneity, and the genesis of stem-like cancer cell states likely reflects the corruption of a reactivated normal stem cell repertoire. We are compelled to investigate the spectrum of both normal and neoplastic stem cell states in the development of new strategies that target plasticity and the reprogramming of cancer cells rather than selected markers in CSC-like cells. But, can we manipulate the reprogramming events within tumor tissues to create self-evolving developmental windows of cancer disease and recover past events in fast-growing types of human tumors? Can patient-derived cancer cells be genetically engineered in a manner that can inform us beforehand about the future of individual tumors to molecularly anticipate and therapeutically prevent their undesirable killing activity, as in Minority Report?

Translational research with patient-derived cells and orthotopic models is the newest approach for closer-to-bedside translational cancer research. The establishment and characterization of serially transplantable, orthotopic, subject-derived tumor grafts that retain crucial characteristics of the original primary tumor specimen and efficiently reproduce drug-resistance and/or dissemination patterns that are characteristic of specific tumors at diagnosis are useful resources for the selection of more appropriate treatment regimens and the development of new drug therapies and novel therapeutic applications for currently approved drugs.56-64 The assessment of therapy responses in patient-derived orthotopic tumor models that maintain the morphologic, histologic, and genetic characteristics of patient tumors, including the behavior of the stromal component and tissue architecture, would improve preclinical drug translation to patients. However, efficiency, speed, and cost limit the use of this type of in vivo mouse avatar-based diagnostic model. The development process requires large amounts of fresh tumor material and intensive resources to generate the tumor graft. Even in the best conditions, 25–30% of implants fail, and those that engraft require 6–8 mo of additional propagation to be useful for treatment. The limitations of this approach certainly challenge the broad clinical application of the process, but some promising response data suggest that these “mouse avatars” are an interesting research tool that may become useful when combined with the genomic revolution. However, the massive resources devoted to genome sequencing of human tumors have produced important data sets for the cancer biology community, but little new biology has been revealed.65 Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of patient tumors before and after chemotherapy coupled with the patient tumor cells growth in mice to test the NGS technique-driven predictions might further complicate any attempt to translate bulk genetic data into therapeutic treatment options in a simple, straightforward manner. Pharmacogenomic studies, such as the breast cancer genome guided therapy study (BEAUTY Project), in which researchers obtain 3 whole-genome sequences (one from the patient’s healthy cells before treatment, one tumor genome before chemotherapy, and one tumor genome after chemotherapy) and pair patients with mouse avatars to identify the best individual treatment, will clarify whether chemotherapy can be tailored to cancer patients based on their individual and tumor genomes. Therefore, this technique combination should advance our understanding of cancer biology, because the recapitulation of entire tumor heterogeneity in patient-derived cells allows for organ-specific drug sensitivity evaluation and mechanistic explanations of chemo-resistance. True proof-of-concept will come from drug candidates that are efficacious in patient-derived cell xenograft models, which are easily translated into clinical applications. The primary patient-derived tumor model is promising for genome-wide personalized drug discovery and a more rational-driven modeling of clinical trials, but time- and resource-consuming mouse avatar translational platforms will be limited to cutting-edge research laboratories. We propose that the Yamanaka stem cell technology can be used to (epi)genetically reprogram primary cancer cells obtained directly from individual patients to create self-evolving developmental windows of cancer disease.

PreCog-iPS cancer cells

Generation and utilities

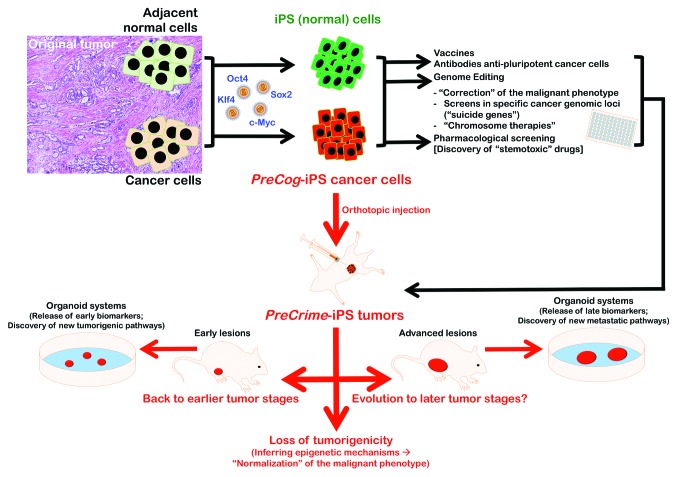

We hypothesize that the nuclear reprogramming of patient-derived tumor cells can yield a large CSC-like population, i.e., PreCog-iPS cancer cells, which could theoretically be propagated indefinitely in a pluripotent state or near-pluripotent state. In an oversimplified, hypothetical approach, cancer samples will be obtained immediately after resection, and histologically normal tissues at specimen margins will be used as controls (Fig. 2). Epithelial cells will be isolated, and cancer and normal margin cells will be infected with viruses encoding the Yamanaka stemness factors. Genomic DNA will be isolated from the specimen margin and cancer epithelial cells that were cultured separately. PreCog-iPS cancer cells that have captured the genome of an affected individual could be generated using the reprogramming of tumoral epithelial cells and the apparently normal, isogenic cells beyond the tumor margins. These cells will be immediately available for experimental manipulation, including the preparation of cancer vaccines, pharmacological screenings aimed to discover antibodies against pluripotent cancer cells, and the exploration of their developmental potential. For example, a high-throughput screen to identify cytotoxic inhibitors of PreCog-iPS cancer cells may be established. The development and optimization of a protocol that will enable the culture of undifferentiated PreCog-iPS cancer cells in a high-content, multiwell plate will allow for the automatic application of multiple (known or experimental) anti-cancer compounds and the accurate assessment of cell viability after short-term (e.g., 24 h) exposure. Pluripotent-specific inhibitors could be identified at the individual patient level. We could screen the selective cytotoxicity of identified drugs in multiple concentrations against differentiated cells that are genetically matched to the undifferentiated cells in the previous screen to obtain reliable sensitivity values. We can also screen the original patient-derived tumor cells from which the iPS cancer cell lines were derived to generate reliable sensitivity values for the PreCog-iPS and their cancer cells of origin. The setting of very stringent thresholds (e.g., >80% inhibition in PreCog-iPS cancer cells but less than 20% inhibition in other types of differentiated cancer cells at the same high concentration of a given compound) might finally identify pluripotent-specific cancer (PluriSCan) drugs, i.e., bona fide “stemotoxic” cancer drugs.66 PreCog-iPS cancer cells should lose their sensitivity to PluriSCan-stemotoxic drugs upon differentiation, and patient-derived cancer cells should acquire this sensitivity upon their reprogramming to iPS cells. The short exposure duration of the PluriSCan-stemotoxic drugs in this screen (24 h) and the stringent threshold for “hit” identification (>80% reduction in number of viable cells) will identify cytotoxic compounds that actively eliminate pluripotent cancer cells rather than proliferation inhibitors. We can verify the pluripotent-specific effect of PluriSCan-stemotoxic drugs by utilizing genetic labeling systems for the expression of pluripotent hallmark genes (e.g., red labeling) vs. early markers of differentiation (e.g., green labeling), because these agents will specifically eliminate undifferentiated (red) cells without a detectable effect on the (green) differentiated population. The application of toxicogenomic approaches to identify gene expression alterations after exposure of the PreCog-iPS cancer cells to the PluriSCan-stemotoxic drugs might provide a functional annotation of deregulated genes and identify key pathways that are causally perturbed by the cytotoxic effects of PluriSCan-stemotoxic drugs. A battery of unknown compounds with putative anti-cancer activity may be tested by applying the gene expression data to the connectivity map (cmap), which is a database of genome-wide transcriptional expression data generated from cultured human cells treated with bioactive small molecules. This process can facilitate the discovery of pathways that are perturbed by small molecules of unknown activity based on the common gene expression changes that similar small molecules confer. Importantly, the screening and discovery of “hits” might be extremely valuable in the search for personalized drug candidates with anti-CSC activity, even if patient-derived PreCog-iPS cancer cells reach a near-pluripotent state that rapidly derives in exacerbated and imbalanced early cancer cell differentiation.

Figure 2. Nuclear reprogramming of patient-derived cancer cells: Generation and utilities. Schematic drawing depicting the generation and utilities of patient-derived PreCog-iPS cancer cells and PreCrime-iPS orthotopic tumors.

The emergence of genome-editing technology over the past few years has made it feasible to generate and investigate human cellular disease models with greater speed and efficiency. The extent to which patient-derived iPS cancer cells will offer any advantage in our understanding of the disease process might appear unclear for a disease that is driven by numerous genetic and environmental factors, such as cancer. We should acknowledge that the most rigorous possible comparisons would occur between cell lines that differ only in disease mutations, i.e., otherwise isogenic cell lines. The correction of specific genetic alterations into the genomes of PreCog-iPS cancer cells would allow investigators to directly connect genotype to phenotype and establish causality (e.g., functional studies to validate new cancer gene candidates) in a pluripotent cancer background and during self-evolving differentiated states. The results can compare relevant phenotypes (e.g., sensitivity to molecularly targeted drugs) and largely minimize confounders to draw more scientifically rigorous conclusions. Any off-targets that are produced by genome-editing tools might make it unrealistic to expect 100% isogenic parental and targeted cell lines in any given experiment. However, this factor does not undermine the fact that the genomic engineering of iPS cells derived from patient-derived cancer cells and isogenic iPS cells derived from apparently normal, isogenic cells beyond the tumor margins may become a proof-of-principle strategy and provide unforeseen insight into the stemness-driven pathophysiology of cancer diseases. The most robust possible proof-of-concept study design would be the insertion of well-known mutations that are commonly overrepresented in some cancer tissues (e.g., KRAS in pancreas and colon cancer, EGFR in lung carcinoma) or new cancer gene driver candidates into an iPS cell line that is reprogrammed from either unsorted or specific subpopulations (e.g., adult stem cells) in the normal tissue adjacent to cancer tissue. This method would test the sufficiency of the mutation for disease, the necessity of the mutation for the disease behavior, and/or the response to molecularly targeted drugs, and correct key disease mutations in a cancer patient-specific iPS cell line. Currently existing genomic-editing tools in human pluripotent stem cells, e.g., zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and clustered regularly interspaced shored palindromic repeats (CRISPRs)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) systems,67-71 could perform proof-of-principle exercises to unambiguously elucidate the necessity and sufficiency of given mutations for given cancer disease phenotypes. This approach might be extremely valuable to assess the importance of genetic modifiers on cancer disease penetrance, i.e., whether a cancer mutation evokes a diseases phenotype in some cell lines but not in others. It might be particularly informative to start with a BRCA1-mutated breast cancer patient-specific iPS cell line and use genome editing to “cure” the BRCA1 disease mutation.

The “correction” of the malignant phenotype in culture using PreCog-iPS cells in the short-term might significantly accelerate the study of cell pathology and disease modeling and facilitate translational research into therapeutics. Genome-editing tools should create a straightforward approach to insert reporters into cancer genomic loci of interest to allow for RNA-interference or small-molecule screens to identify genes and probes that provide the desired functional effect. The use of genome editing in the long-term may create “chromosome therapies” that utilize epigenetic strategies to regulate chromosomes, because PreCog-iPS cancer cells will harbor the corresponding aberrant karyotype or the initial patient-derived tumor population. Tumor cells frequently display an abnormal number of chromosomes, a phenomenon known as aneuploidy, and non-cancerous aneuploidy generates abnormal phenotypes in all species tested (e.g., trisomy 21 generates Down syndrome). Cancer-specific aneuploidies generate complex, malignant phenotypes through abnormal doses of the thousands of genes. Aneuploidy may partially explain 2 CSC-related cell properties, such as immortality, because cancers survive negative mutations and cytotoxic drugs via resistant subspecies through their cellular heterogeneity, and non-selective phenotypes, such as metastasis, because of linkage with selective phenotypes on the same chromosomes.72-78 The structural chromosome rearrangements have received considerable attention, but the role of whole-chromosome aneuploidy in cancer is less understood. This discussion has overshadowed efforts to address a related but no less important question: can aneuploidy be targeted for cancer therapy? Jiang et al.79 recently reported that the insertion of a large, inducible X-inactivation (XIST) transgene into the DYRK1A locus on chromosome 21 in Down syndrome pluripotent stem cells using ZFNs de facto corrected gene imbalance across an extra chromosome. Genome-editing tools that correct the aneuploidy karyotype might become the cancer therapies, because these tools may be effective against a vast array of aneuploidy tumors without previous knowledge of the underlying mutations or the deregulated pathways.

PreCrime-iPS mouse avatars

Generation and utilities

PreCog-iPS cells might be valuable in the design of new approaches for cancer disease modeling, because the procedures leading to their generation can be repeated in a highly controlled manner to generate large numbers of cells for in vitro and in vivo studies. Moreover, the reversal of patient-derived cancer cells from a given evolutionary stage via reprogramming with Yamanaka stemness factors should allow for redifferentiation in orthotopic injection assays in the target tissues of immunodeficient mice, i.e., the PreCrime-iPS mouse avatars. A subset of these cells would undergo several developmental stages of human cancer (Fig. 2). The PreCrime-iPS avatar mice model should cycle through specific stages of human cancer diseases, as opposed to the examination of cancer progression characteristics in an animal model and the assessment of human applicability. First, the reprogramming of cancer cells from recurrent, late-stage human carcinomas to a pluripotent state should create the reappearance of cellular features and molecular markers of the early and intermediate stages of that particular cancer that are no longer evident in the terminal stages from which the PreCog/PreCrime-iPS models originated. The recapitulation of early stages of biologically aggressive types of human carcinomas (e.g., pancreatic cancer, glioblastoma, ovarian cancer, and lung cancer) creates unexplored cancer developmental windows that may allow for a direct exploration of their biological properties for drug screening, diagnosis, and personalized treatment. Comparisons with the original tumor of the individual patient to short-term histological and genomic profiles can inform us about the ability of PreCrime-iPS cells to differentiate into lesions associated with earlier stages of the advanced disease. Similarly, long-term histological and genomic profiles can inform us about the ability of early stage PreCrime-iPS cells to differentiate into lesions that succeeded as invasive stages of the disease in vivo. These profiles provide a complete recapitulation of the carcinogenesis process that is fully driven by the genome of an affected individual and captured during the process of PreCog-iPS cell generation.

It might be intriguing to investigate whether we might expect the appearance of cellular features and molecular markers in the earliest, precursor stages of that particular cancer (e.g., hyperplastic enlarged lobular units in breast cancer) upon the reprogramming of cancer cells from early or even pre-invasive cancer stages (e.g., ductal carcinoma in situ lesions in breast cancer) to a pluripotent state. Regardless of the orthotopically injected PreCog-iPS cell fate, we can generate a system in which cancer structures that occur within PreCrime-iPS tumors may be studied as live, ex vivo, or in vitro models of the precursor, early, invasive, and metastatic stages of individual tumors at the patient level. We might harvest tissues from PreCrime-iPS tumors with contralateral control tissue at different intervals after injection to establish the conditions under which the tissues will be cultured in vitro. We can use this “organoid system” to rapidly identify biomarkers and pathways that could permit early detection or facilitate disease monitoring after therapy. For example, we could examine the proteins that are specifically secreted or released from explants of PreCrime-iPS tumors by comparison with proteins that are secreted or released from explants of contralateral control tissue from the parental PreCog-iPS cell line cultured in the undifferentiated state. Bioinformatics approaches can be used to discover previously unappreciated networks and biomarkers associated with very early- (even pre-cancerous), early-to-invasive-, or metastatic-stage pathology by combining data from an iPS-driven “cancer xenopatient 2.0” mouse model of the disease and currently available databases of human clinical samples.

If the pluripotency epigenetic environment can dominate over certain oncogenic states, an accurate decodification of the molecular barriers that prevent the cancer (differentiated) phenotype from being reversed to a pluripotent/near-pluripotent (stem) status might inform us of the key mechanisms that govern how differentiated cancer cells dynamically enter into stem-like cellular states. Specifically, if reprogramming of patient-derived tumor cells leads to a loss of tumorigenicity, then it might be possible to normalize in vivo the malignant phenotype by inferring the epigenetic marks that have corrected the malignant effects of oncogene activation and oncosuppressor gene inactivation in the reprogrammed cancer cell population. Different experimental results suggest that cancer cells can be reprogrammed to a non-tumoral fate that loses their malignancy. Miyoshi et al.80 reported that defined factors induced reprogramming of gastrointestinal cancer cells to demonstrate slow proliferation, sensitization to differentiation-inducing treatment, and reduced in vivo tumorigenesis in NOD/SCID mice. However, these authors reported only xenograft formation with no histology or immunohistochemistry. Zhang et al.81 recently demonstrated that the reprogramming of sarcoma cells using the 4 canonical Yamanaka genes plus Nanog and Lin28 created cancer cells that lost their tumorigenicity, exhibited reduced drug resistance, and dedifferentiated as iPS cells into various lineages, such as fibroblasts and hematopoietic lineages. Interestingly, the expression of endogenous c-Myc appeared to be reduced in their cellular model, and it was hypermethylated during the reprogramming process. These findings support the notion that the epigenetic modification of a cancer cell via nuclear reprogramming could correct some malignant effects of oncogene activation and oncosuppressor gene inactivation, which may constitute the basis for a novel strategy to control tumor progression.81,82 Zhang et al.81 reported the terminal differentiation and loss of tumorigenicity of human sarcomas via pluripotency-based reprogramming, but these authors failed to observe benign mature tissue elements in their teratomas assays. Kim et al.,83 the only group that has reported the successful generation of a patient-derived iPS cell line from human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), only obtained one iPS-like line from a pancreatic cancer harboring a KRAS mutation, the predominant driver of PDAC, and a deletion in exon 2 of the pivotal tumor suppressor CDKN2A. Biological barriers, such as cancer-specific genetic mutations, epigenetic remodeling, accumulation of DNA damage, or reprogramming-induced cellular senescence, may influence the reprogramming of human primary cancer cells.84 Therefore, further work will determine the types of mutations that predict whether a cancer cell can be reprogrammed to pluripotency. Conversely, genetically engineered models of conditionally reprogrammable mice that transiently express the Yamanaka stemness factors85 sequentially to the activation of phenotypic copies of specific cancer diseases (e.g., in transgenic mice of BRCA1 deficiency or HER2 overexpression or in chemically induced mouse models of human carcinomas) might inform us about the feasibility of the “reprogramming cure” of cancer as an revolutionary alternative to the present therapeutic approaches.

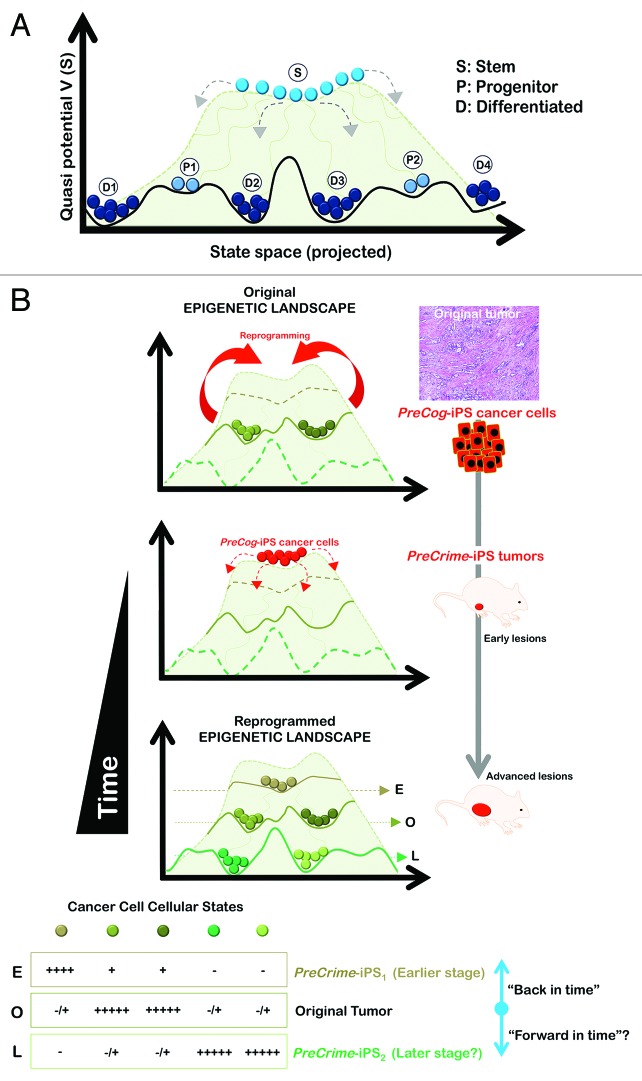

As mentioned above, PreCrime-iPS cells from individual tumors are expected to have the capacity to progress through the early or even pre-cancerous developmental stages of one individual cancer. This approach would provide a unique opportunity for the discovery of intrinsic processes and the secreted biomarkers (e.g., proteins, metabolites) of live, early-stage human cancer cells and particularly the biologically aggressive types of human carcinomas. However, CSC cellular states may already be programmed in pre-malignant cancer lesions, and these tumor-initiating cells could determine the later phenotype of the invasive lesion. Therefore, PreCrime-iPS cancer cells would develop cancer stages ahead of the original stage, from which PreCog-iPS cells were engineered, i.e., bona fide self-evolving in vivo models that can inform us beforehand about the future of individual tumors. A schematic overview integrating the key concepts underlying the relevance of the “cancer xenopatients 2.0” based on the generation and study of PreCog/PreCrime-iPS cancer cells is provided in Figure 3. The hypothetical Waddington epigenetic landscape structure displayed in Figure 3 schematically integrates the concepts behind the hierarchy of cancer cell type diversification during cancer development as a disease or reprogramming and differentiation.86-88 The horizontal axis is a schematic projected state space coordinate, and the elevation (quasi-potential) represents the relative instability of individual cancer cellular states at each space location. The balls represent each type of cancer cell, defined by a particular position in the state space. Each cancer cell type in the tumor corresponds to one of the high-dimensional attractors that a large network of hundreds to thousands of genes can produce in a cancer tissue. Attractors of regulatory networks exhibit the natural properties of distinct cancer cellular states (i.e., cancer cell types), because they are discretely distinct entities and self-stabilizing (i.e., robust to small perturbations but permissive to “all-or-nothing” transitions to other attractors given sufficiency high perturbations). The attractors behave as the lowest points in “potential wells” or valleys, which are separated by “hill tops” that correspond to unstable states and represent the bona fide epigenetic barriers in the patient-derived cancer genome landscape. However, the elevation in the quasi-potential energy landscape does not constitute a true “potential energy” in the classical sense, but rather helps conceptualize the global dynamics of non-equilibrium systems (such as gene regulatory networks) by providing information on the “relative weights” of the various valleys. Therefore, it accurately affords the intuition of a type of gravity that would drive the stability-seeking movement of a given cancer cell state “downward”.

Figure 3. Xenopatients 2.0: The key principles of reprogramming patient-derived cancer genomes as viewed within the analogy of Waddington’s landscape. The hypothetical epigenetic landscape depicted in (A) illustrates the concepts behind the hierarchy of cell type diversification during development and it can also be used to illustrate the principles of the “crater-like” attractor state of pluripotent stem cells on top of walled plateaus and what might be expected from reprogramming patient-derived cancer genomes (B). The horizontal axis is a schematic, projected state space-coordinate; the elevation (quasi-potential) represents the relative instability of individual states at each state space location. Each cell type, defined by a position in state space is represented by balls. The more “plastic” the cell, the higher up the hill it is. Hence, stem (S) pluripotent is at the top, multipotent further down, progenitor (P) below that, and differentiated (D) at the bottom. The hills and valleys represent the potential differentiative pathways available. A particular basin may be approached from more than one pathway. Taking the detour via the pluripotent PreCrime-iPS (“jumping back to the summit”), we ensure the occurrence of a robust “ground state” that is self-maintaining in culture conditions favorable to the stem cell state but nevertheless globally situated at a “high altitude”, which affords the PreCrime-iPS state a strong urge to spontaneously and stochastically differentiate away and occupy all other attractors situated at a lower “altitude” without the need of an “instructive” signal to exhibit the gene expression patterns owned by any specific type of cancer cells. In this scenario, in which the cancer genome landscape has “direction” (i.e., once the “ball” has committed to its descent, it cannot roll back up of its own accord; it is expected that there is no requirement to retrace developmental pathways intrinsically captured in the patient-derived cancer) (i.e., the fundamental positioning of the cancer cellular states relative to the terrain of differentiation would be intrinsically determined by the gene regulatory networks pre-existing in the tumor due to the self-stabilizing and memory properties of attractors) once the signals activated in the orthotopic site will flatten the “pluripotency crater” and allow cells to move down the landscape. Cancer cells will differentiate by traveling down the crevasses between the valleys, sometimes starting down different trajectories from the beginning and other times sharing ambiguous fates at the top that get defined as they move along the pathway. Therefore, the Waddingtonian representation of induced pluripotency in patient-derived cancer genomes landscapes intuitively illustrates the notion that diverse cancer states can be early (E) recapitulated (“back in time” PreCrime-iPS1) and/or late (L) forecasted (“forward in time” PreCrime-iPS2), as shown in the cuts through the levels corresponding to the lines in the lowest landscape. Cells are represented by balls, fates by colors.

The state space idea provides a conceptual framework that easily explains how cancer reprogramming should be viewed as transitions between attractors and simultaneously illuminates why the grafting of biologically aggressive cancer cells obtained from advanced cancer stages into immunodeficient mice as tumor fragments, dispersed cells, or cells sorted for CSC markers allows for an immediate regression to the late-stage phenotype and thus an undesirable spatiotemporal restriction to the rapidly growing, aggressive tumor stage from which the injected cells were derived. The inefficiency of cancer cells grafted into mice to generate a highly informative occurrence of stage-specific expression of the cancer genome can be explained in terms of the “ruggedness” of the attractor landscape. Heterogeneous cancer cell populations are expected to be dispersed and occupy multiple sub-attractors within an attractor with a “washboard” surface. In this scenario, the large number of these microstates within any cancer cell population notably disperses the response profiles in the absence of strong (re)programming perturbations. In other words, heterogeneous cancer cell populations that are largely refractory to differentiating signals (which would remove them from the attractor to occupy lower attractors of differentiated cells or destabilize the attractor to generate new patterns of differentiation) will rapidly repopulate the original epigenetic landscape of the primary tumor, because the global slope in the landscape also accounts for the time-of-development arrow. The isolation of extremely rare CSC-like populations based on the absence or presence of a few molecular markers may conversely enrich cellular states that sit on the separatrix (hilltops and crests) that separates the attractors (i.e., a delicate stationary state that is unstable and rapidly moves to either attractor in response to any slight perturbation) or near the rim of the attractor basin (i.e., a group of “outlier cells” that are primed to differentiate). This commonly used approach fails to reconcile rarity with the robustness of the CSC-like phenotype as defined by various arbitrary markers. In summary, the height of epigenetic barriers between the discrete cellular phenotypes, the state space distance between cell types, the ruggedness of landscape, and the heterogeneity of starting cancer cells notably impede the cancer genome of a particular individual to be expressed in a stage-specific fashion as opposed to undergoing an immediate regression to the late-stage phenotype from which the tumor cells are commonly derived in the classic mouse avatar approaches. A different scenario should emerge when activating a pre-existing coherent gene expression program by exogenously stimulating a transition into a “central attractor” that encodes such a program. We may be able to generate metastable attractors with a large, flat basin that is particularly wide in pluri-/multipotent cells and maintained by the gene circuit around Yamanaka stemness factors by taking the detour via the pluripotent iPS state, thus allowing for balanced but large fluctuations to “scan” the cancer state space and temporally approach the pattern of a prospective “lineage” of differentiated cancer cells. Due to its central location in the state space between the valleys that represent their prospective fates, stem cell attractors generated from individual tumors will naturally exhibit promiscuous gene expression and have access to the attractors of various cancer cell types. These stem cell-like attractors will be situated at a “high altitude” in the landscape, and these cellular states will afford a strong urge to “flow down” the valleys and “differentiate away” by populating all other cancer cell attractors situated at a lower “altitude”. The well-recognized tendency of iPS cell lines to preferentially differentiate into their lineages of origin should translate into the preference for PreCog/PreCrime-iPS cancer cells to regenerate the cancer type from which they were derived. PreCog-iPS cells may spontaneously and stochastically differentiate into all of the cell types comprised in the captured cancer genome without the need of an “instructive” signal to convey the gene expression patterns owned by particular cancer cell states, as occurs in multipotent progenitor cells or embryonic stem cells when they are placed in culture conditions unfavorable to the stem cell state. Upon re-establishing bona fide pluripotency by pushing patient-derived cancer cells toward a new fate in an “uphill battle”, iPS cells in PreCrime-mouse avatars may be able to “roll down” toward more possible outcomes than originally existed in the patient’s tumor, because the process of reprogramming implicates a restructuring of the epigenetic landscape and a stabilization of the transition states. Therefore, the successful generation of all cancer cell fate decisions in a given cancer genome landscape could not be achieved spontaneously on any reasonable time-scale using currently available mouse avatar strategies, because they should be accomplished through transitions between high-dimensional attractors. Nuclear reprogramming of patient-derived cancer cells can more rapidly identify walkable paths that connect existing or “future” attractors, because it could create all of the pre-programmed attractor states that can possibly emerge from the gene regulatory networks contained in a given patient-derived cancer gene genome.

Corollary

Our current ability to recover or foresee the evolutionary trajectory of any individual cancer remains in its infancy. We have hypothesized that pluripotent or near-pluripotent stem cell lines generated from patient-derived cancer cells should have the capacity to progress through many, if not all, of the developmental stages of the cancer based on the recently recognized ability of cultured tumor cells to be reprogrammed to pluripotency by nuclear reprogramming. We can create self-evolving developmental windows of a captured cancer genome and recover past events in fast-growing types of human carcinomas by manipulating the naturally occurring reprogramming events within tumor tissues. Consequently, this live-cell progression approach will provide us with an unforeseen experimental setting in which early molecular markers for intrinsically aggressive tumors that rapidly evolve into aggressive, treatment-refractory cancer stages may be discovered. Reprogramming the epigenetic landscapes of patient-derived cancer genomes using the Yamanaka stemness factors should generate state-of-the-art cellular tools to reveal biological properties and molecular features that will not be evident in the advanced stage at which the tumor samples are generally obtained to assess diagnostic and prognostic parameters. Moreover, nuclear reprogramming of patient-derived cancer cells can generate “forthcoming landscapes” that can inform us beforehand about the future of individual tumors and the occurrence of unorthodox inter-cell developmental paths in tumor tissues. The proposed models could test potential therapies to block specific developmental stages of the disease. Therefore, a new era of mouse avatars (xenopatients) 2.0 might revolutionarily transform the currently available personalized translational platforms and significantly improve our tools for drug screening, diagnosis, and personalized treatment.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2012-38914), Plan Nacional de I+D+I, MICINN, Spain.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/27770

References

- 1.Bond JA, Oddweig Ness G, Rowson J, Ivan M, White D, Wynford-Thomas D. Spontaneous de-differentiation correlates with extended lifespan in transformed thyroid epithelial cells: an epigenetic mechanism of tumour progression? Int J Cancer. 1996;67:563–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960807)67:4<563::AID-IJC16>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K, Okita K, Nakagawa M, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from fibroblast cultures. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:3081–9. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clevers H. The cancer stem cell: premises, promises and challenges. Nat Med. 2011;17:313–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman MA, Lawrence MS, Keats JJ, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Schinzel AC, Harview CL, Brunet JP, Ahmann GJ, Adli M, et al. Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011;471:467–72. doi: 10.1038/nature09837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger MF, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Drier Y, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko AY, Sboner A, Esgueva R, Pflueger D, Sougnez C, et al. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011;470:214–20. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navin N, Kendall J, Troge J, Andrews P, Rodgers L, McIndoo J, Cook K, Stepansky A, Levy D, Esposito D, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472:90–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–11. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce GB, Speers WC. Tumors as caricatures of the process of tissue renewal: prospects for therapy by directing differentiation. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1996–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinsmith LJ, Pierce GB., Jr. Multipotentiality of single embryonal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1964;24:1544–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passegué E, Jamieson CH, Ailles LE, Weissman IL. Normal and leukemic hematopoiesis: are leukemias a stem cell disorder or a reacquisition of stem cell characteristics? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11842–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034201100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell. 2009;139:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta PB, Fillmore CM, Jiang G, Shapira SD, Tao K, Kuperwasser C, Lander ES. Stochastic state transitions give rise to phenotypic equilibrium in populations of cancer cells. Cell. 2011;146:633–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaffer CL, Brueckmann I, Scheel C, Kaestli AJ, Wiggins PA, Rodrigues LO, Brooks M, Reinhardt F, Su Y, Polyak K, et al. Normal and neoplastic nonstem cells can spontaneously convert to a stem-like state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7950–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102454108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Wang G, Struhl K. Inducible formation of breast cancer stem cells and their dynamic equilibrium with non-stem cancer cells via IL6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1397–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018898108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polytarchou C, Iliopoulos D, Struhl K. An integrated transcriptional regulatory circuit that reinforces the breast cancer stem cell state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14470–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212811109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spike BT, Wahl GM. p53, Stem Cells, and Reprogramming: Tumor Suppression beyond Guarding the Genome. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:404–19. doi: 10.1177/1947601911410224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shackleton M, Quintana E, Fearon ER, Morrison SJ. Heterogeneity in cancer: cancer stem cells versus clonal evolution. Cell. 2009;138:822–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magee JA, Piskounova E, Morrison SJ. Cancer stem cells: impact, heterogeneity, and uncertainty. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:283–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature. 2013;501:328–37. doi: 10.1038/nature12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abollo-Jiménez F, Jiménez R, Cobaleda C. Physiological cellular reprogramming and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2010;20:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castellanos A, Vicente-Dueñas C, Campos-Sánchez E, Cruz JJ, García-Criado FJ, García-Cenador MB, Lazo PA, Pérez-Losada J, Sánchez-García I. Cancer as a reprogramming-like disease: implications in tumor development and treatment. Semin Cancer Biol. 2010;20:93–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohm JE, Mali P, Van Neste L, Berman DM, Liang L, Pandiyan K, Briggs KJ, Zhang W, Argani P, Simons B, et al. Cancer-related epigenome changes associated with reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7662–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leis O, Eguiara A, Lopez-Arribillaga E, Alberdi MJ, Hernandez-Garcia S, Elorriaga K, Pandiella A, Rezola R, Martin AG. Sox2 expression in breast tumours and activation in breast cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:1354–65. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corominas-Faja B, Cufí S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cuyàs E, López-Bonet E, Lupu R, Alarcón T, Vellon L, Iglesias JM, Leis O, et al. Nuclear reprogramming of luminal-like breast cancer cells generates Sox2-overexpressing cancer stem-like cellular states harboring transcriptional activation of the mTOR pathway. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:3109–24. doi: 10.4161/cc.26173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vazquez-Martin A, Cufí S, López-Bonet E, Corominas-Faja B, Cuyàs E, Vellon L, Iglesias JM, Leis O, Martín AG, Menendez JA. Reprogramming of non-genomic estrogen signaling by the stemness factor SOX2 enhances the tumor-initiating capacity of breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:3471–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.26692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suvà ML, Riggi N, Bernstein BE. Epigenetic reprogramming in cancer. Science. 2013;339:1567–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1230184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kemp CJ, Donehower LA, Bradley A, Balmain A. Reduction of p53 gene dosage does not increase initiation or promotion but enhances malignant progression of chemically induced skin tumors. Cell. 1993;74:813–22. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90461-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tapia N, Schöler HR. p53 connects tumorigenesis and reprogramming to pluripotency. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2045–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng H, Ying H, Yan H, Kimmelman AC, Hiller DJ, Chen AJ, Perry SR, Tonon G, Chu GC, Ding Z, et al. p53 and Pten control neural and glioma stem/progenitor cell renewal and differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1129–33. doi: 10.1038/nature07443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao T, Xu Y. p53 and stem cells: new developments and new concerns. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pece S, Tosoni D, Confalonieri S, Mazzarol G, Vecchi M, Ronzoni S, Bernard L, Viale G, Pelicci PG, Di Fiore PP. Biological and molecular heterogeneity of breast cancers correlates with their cancer stem cell content. Cell. 2010;140:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quintana E, Shackleton M, Foster HR, Fullen DR, Sabel MS, Johnson TM, Morrison SJ. Phenotypic heterogeneity among tumorigenic melanoma cells from patients that is reversible and not hierarchically organized. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:510–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer MJ, Fleming JM, Lin AF, Hussnain SA, Ginsburg E, Vonderhaar BK. CD44posCD49fhiCD133/2hi defines xenograft-initiating cells in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4624–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Godar S, Ince TA, Bell GW, Feldser D, Donaher JL, Bergh J, Liu A, Miu K, Watnick RS, Reinhardt F, et al. Growth-inhibitory and tumor- suppressive functions of p53 depend on its repression of CD44 expression. Cell. 2008;134:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu C, Kelnar K, Liu B, Chen X, Calhoun-Davis T, Li H, Patrawala L, Yan H, Jeter C, Honorio S, et al. The microRNA miR-34a inhibits prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44. Nat Med. 2011;17:211–5. doi: 10.1038/nm.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soda Y, Marumoto T, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Soda M, Liu F, Michiue H, Pastorino S, Yang M, Hoffman RM, Kesari S, et al. Transdifferentiation of glioblastoma cells into vascular endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4274–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B, Quinlan MP, Takahashi F, Maheswaran S, McDermott U, Azizian N, Zou L, Fischbach MA, et al. A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell. 2010;141:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hough SR, Laslett AL, Grimmond SB, Kolle G, Pera MF. A continuum of cell states spans pluripotency and lineage commitment in human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shu J, Wu C, Wu Y, Li Z, Shao S, Zhao W, Tang X, Yang H, Shen L, Zuo X, et al. Induction of pluripotency in mouse somatic cells with lineage specifiers. Cell. 2013;153:963–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montserrat N, Nivet E, Sancho-Martinez I, Hishida T, Kumar S, Miquel L, Cortina C, Hishida Y, Xia Y, Esteban CR, et al. Reprogramming of human fibroblasts to pluripotency with lineage specifiers. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:341–50. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawamura T, Suzuki J, Wang YV, Menendez S, Morera LB, Raya A, Wahl GM, Izpisúa Belmonte JC. Linking the p53 tumour suppressor pathway to somatic cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460:1140–4. doi: 10.1038/nature08311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hong H, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Kanagawa O, Nakagawa M, Okita K, Yamanaka S. Suppression of induced pluripotent stem cell generation by the p53-p21 pathway. Nature. 2009;460:1132–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, Collado M, Villasante A, Strati K, Ortega S, Cañamero M, Blasco MA, Serrano M. The Ink4/Arf locus is a barrier for iPS cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460:1136–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marión RM, Strati K, Li H, Murga M, Blanco R, Ortega S, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Serrano M, Blasco MA. A p53-mediated DNA damage response limits reprogramming to ensure iPS cell genomic integrity. Nature. 2009;460:1149–53. doi: 10.1038/nature08287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Utikal J, Polo JM, Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Kulalert W, Walsh RM, Khalil A, Rheinwald JG, Hochedlinger K. Immortalization eliminates a roadblock during cellular reprogramming into iPS cells. Nature. 2009;460:1145–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarig R, Rivlin N, Brosh R, Bornstein C, Kamer I, Ezra O, Molchadsky A, Goldfinger N, Brenner O, Rotter V. Mutant p53 facilitates somatic cell reprogramming and augments the malignant potential of reprogrammed cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2127–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Assou S, Le Carrour T, Tondeur S, Ström S, Gabelle A, Marty S, Nadal L, Pantesco V, Réme T, Hugnot JP, et al. A meta-analysis of human embryonic stem cells transcriptome integrated into a web-based expression atlas. Stem Cells. 2007;25:961–73. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, Weinberg RA. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim J, Woo AJ, Chu J, Snow JW, Fujiwara Y, Kim CG, Cantor AB, Orkin SH. A Myc network accounts for similarities between embryonic stem and cancer cell transcription programs. Cell. 2010;143:313–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong DJ, Liu H, Ridky TW, Cassarino D, Segal E, Chang HY. Module map of stem cell genes guides creation of epithelial cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:333–44. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mizuno H, Spike BT, Wahl GM, Levine AJ. Inactivation of p53 in breast cancers correlates with stem cell transcriptional signatures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:22745–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017001108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rubio-Viqueira B, Jimeno A, Cusatis G, Zhang X, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Karikari C, Shi C, Danenberg K, Danenberg PV, Kuramochi H, et al. An in vivo platform for translational drug development in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4652–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jimeno A, Tan AC, Coffa J, Rajeshkumar NV, Kulesza P, Rubio-Viqueira B, Wheelhouse J, Diosdado B, Messersmith WA, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, et al. Coordinated epidermal growth factor receptor pathway gene overexpression predicts epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor sensitivity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2841–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jimeno A, Feldmann G, Suárez-Gauthier A, Rasheed Z, Solomon A, Zou GM, Rubio-Viqueira B, García-García E, López-Ríos F, Matsui W, et al. A direct pancreatic cancer xenograft model as a platform for cancer stem cell therapeutic development. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:310–4. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calles A, Rubio-Viqueira B, Hidalgo M. Primary human non-small cell lung and pancreatic tumorgraft models–utility and applications in drug discovery and tumor biology. Curr Protoc Pharmacol 2013;Chapter 14:Unit 14.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bertotti A, Migliardi G, Galimi F, Sassi F, Torti D, Isella C, Corà D, Di Nicolantonio F, Buscarino M, Petti C, et al. A molecularly annotated platform of patient-derived xenografts (“xenopatients”) identifies HER2 as an effective therapeutic target in cetuximab-resistant colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:508–23. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lengyel E, Burdette JE, Kenny HA, Matei D, Pilrose J, Haluska P, Nephew KP, Hales DB, Stack MS. Epithelial ovarian cancer experimental models. Oncogene. 2013;••• doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.321. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reyes G, Villanueva A, García C, Sancho FJ, Piulats J, Lluís F, Capellá G. Orthotopic xenografts of human pancreatic carcinomas acquire genetic aberrations during dissemination in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5713–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Castillo-Avila W, Piulats JM, Garcia Del Muro X, Vidal A, Condom E, Casanovas O, Mora J, Germà JR, Capellà G, Villanueva A, et al. Sunitinib inhibits tumor growth and synergizes with cisplatin in orthotopic models of cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant human testicular germ cell tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3384–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vidal A, Muñoz C, Guillén MJ, Moretó J, Puertas S, Martínez-Iniesta M, Figueras A, Padullés L, García-Rodriguez FJ, Berdiel-Acer M, et al. Lurbinectedin (PM01183), a new DNA minor groove binder, inhibits growth of orthotopic primary graft of cisplatin-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5399–411. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yaffe MB. The scientific drunk and the lamppost: massive sequencing efforts in cancer discovery and treatment. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pe13. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knoepfler PS. Deconstructing stem cell tumorigenicity: a roadmap to safe regenerative medicine. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1050–6. doi: 10.1002/stem.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ding Q, Lee YK, Schaefer EA, Peters DT, Veres A, Kim K, Kuperwasser N, Motola DL, Meissner TB, Hendriks WT, et al. A TALEN genome-editing system for generating human stem cell-based disease models. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:238–51. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Musunuru K. Genome editing of human pluripotent stem cells to generate human cellular disease models. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:896–904. doi: 10.1242/dmm.012054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hockemeyer D, Soldner F, Beard C, Gao Q, Mitalipova M, DeKelver RC, Katibah GE, Amora R, Boydston EA, Zeitler B, et al. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:851–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bobis-Wozowicz S, Osiak A, Rahman SH, Cathomen T. Targeted genome editing in pluripotent stem cells using zinc-finger nucleases. Methods. 2011;53:339–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park KE, Telugu BP. Role of stem cells in large animal genetic engineering in the TALENs-CRISPR era. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2013;26:65–73. doi: 10.1071/RD13258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fabarius A, Li R, Yerganian G, Hehlmann R, Duesberg P. Specific clones of spontaneously evolving karyotypes generate individuality of cancers. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;180:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Duesberg P, Li R, Fabarius A, Hehlmann R. The chromosomal basis of cancer. Cell Oncol. 2005;27:293–318. doi: 10.1155/2005/951598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nicholson JM, Duesberg P. On the karyotypic origin and evolution of cancer cells. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;194:96–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tang YC, Williams BR, Siegel JJ, Amon A. Identification of aneuploidy-selective antiproliferation compounds. Cell. 2011;144:499–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manchado E, Malumbres M. Targeting aneuploidy for cancer therapy. Cell. 2011;144:465–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Holland AJ, Cleveland DW. Losing balance: the origin and impact of aneuploidy in cancer. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:501–14. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pfau SJ, Amon A. Chromosomal instability and aneuploidy in cancer: from yeast to man. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:515–27. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jiang J, Jing Y, Cost GJ, Chiang JC, Kolpa HJ, Cotton AM, Carone DM, Carone BR, Shivak DA, Guschin DY, et al. Translating dosage compensation to trisomy 21. Nature. 2013;500:296–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miyoshi N, Ishii H, Nagai K, Hoshino H, Mimori K, Tanaka F, Nagano H, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M. Defined factors induce reprogramming of gastrointestinal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:40–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912407107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang X, Cruz FD, Terry M, Remotti F, Matushansky I. Terminal differentiation and loss of tumorigenicity of human cancers via pluripotency-based reprogramming. Oncogene. 2013;32(2260.e1-21):2249–60, e1-21. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lang JY, Shi Y, Chin YE. Reprogramming cancer cells: back to the future. Oncogene. 2013;32:2247–8. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim J, Hoffman JP, Alpaugh RK, Rhim AD, Reichert M, Stanger BZ, Furth EE, Sepulveda AR, Yuan CX, Won KJ, et al. An iPSC line from human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma undergoes early to invasive stages of pancreatic cancer progression. Cell Rep. 2013;3:2088–99. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ramos-Mejia V, Fraga MF, Menendez P. iPSCs from cancer cells: challenges and opportunities. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:245–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]