Abstract

Despite the high rate of co-occurring medical conditions experienced by individuals receiving assertive community treatment (ACT), this comprehensive service model continues to be considered primarily a mental health intervention. Without compromising fidelity to the model, ACT can serve as an ideal platform from which to provide both primary and behavioral health care to those with complex service needs. Using a case example, this article considers the transformation of the ACT mental health care model into an integrated health care delivery system through establishing nursing and primary care partnerships. Specifically, by expanding and explicitly redefining the role of the ACT nurse, well-developed care models, such as Guided Care, can provide additional guidelines and training to ACT nurses who are uniquely trained and oriented to serve as the leader and coordinator of health integration efforts.

Keywords: ACT/PACT, primary health care, chronic mental illness, community mental health services, service delivery systems

Assertive community treatment (ACT) is considered the gold standard of community-based approaches to treating individuals with serious mental illnesses (Dixon, 2000). Yet despite the high rate of co-occurring medical conditions experienced by members of this vulnerable population, which contributes to their poor health outcomes and significantly shorter life spans (Colton & Manderscheid, 2006), this comprehensive service model continues to be considered primarily a mental health intervention. However, without compromising fidelity to the model, ACT can serve as an ideal platform from which to provide both primary and behavioral health care to those with complex service needs. This article considers the transformation of the ACT mental health care model into an integrated health care delivery system by expanding and explicitly redefining the role of the ACT nurse to include establishing partnerships with primary care providers.

Background

In the United States, people with serious mental illness experience poor health outcomes and die approximately 25 years earlier than members of the general population (Colton & Manderscheid, 2006). Despite this recognition, differential morbidity and mortality rates have accelerated in recent years (Morden, Mistler, Weeks, & Bartels, 2009; Saha, Chant, & McGrath, 2007), indicating that those with serious mental illness have not benefited from advances in the overall health care system. Although those with low-complexity behavioral health care needs may be able to access traditional mental health and primary care services, persons with high-complexity behavioral health needs, including those with severe mental illness, have not been well served by traditional service systems within either mental health or primary care, as evidenced by continued health disparities among this population (Piatt, Munetz, & Ritter, 2010).

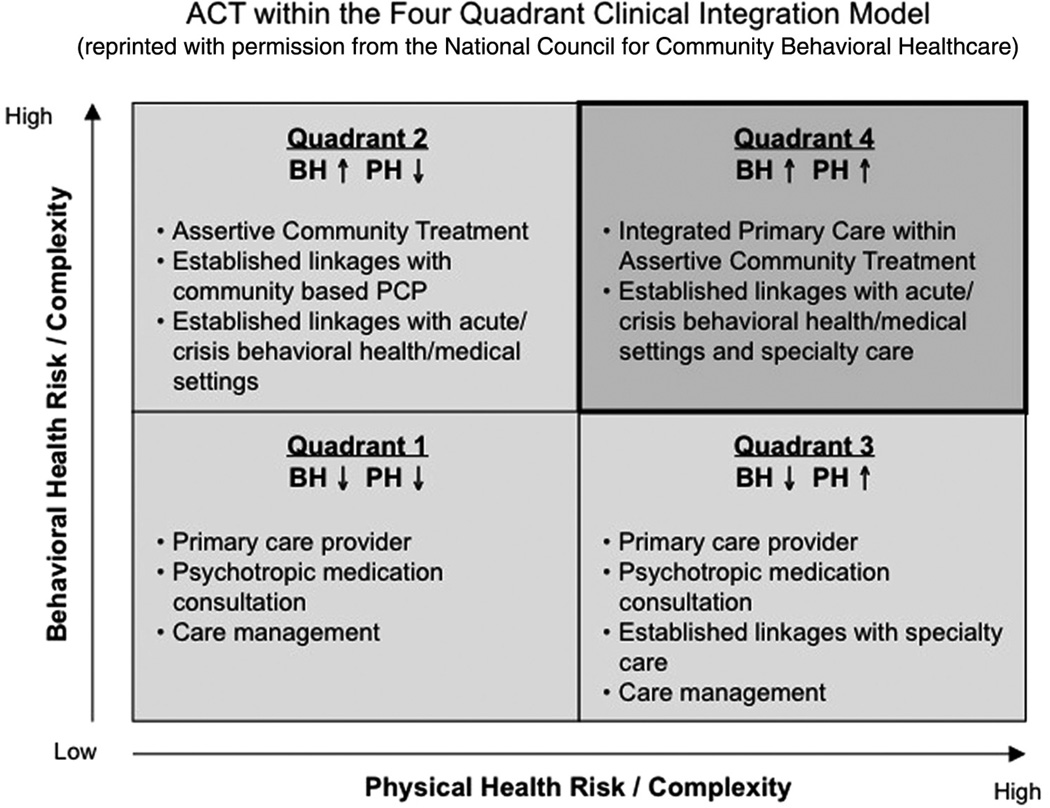

The imperative to integrate the delivery of primary and behavioral health care services, which has been recognized as a clear priority given existing health disparities (Collins, Hewson, Munger, & Wade, 2010), can be viewed as a spectrum based on individual clinical need (Mauer & Druss, 2009). The four-quadrant clinical integration model is a useful framework for identifying varying levels of primary and behavioral health needs (Collins, Hewson, Munger, & Wade, 2010; Mauer & Druss, 2009). It distinguishes between low-level and high-level needs, and recognizes the interplay of these needs within each of the four quadrants.

ACT, with its intensive service delivery design, is directed to individuals with high-level behavioral health needs; quite often, these clients also have high-level physical health risks and complexities. For example, in a cross-sectional study, Ceilley, Cruz, and Denko (2006) found that psychiatric patients receiving ACT had significant, and often multiple, chronic illnesses that required ongoing management for optimal outcomes, with their most common active medical conditions being osteoarthritis, hypertension, hepatitis C, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and reactive airway disease. Such individuals who are clustered in Quadrant 4 of the model and present unique challenges to current treatment approaches would be well served by a model of care in which primary care is integrated within ACT, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Assertive community treatment within the four-quadrant clinical integration model

Note. BH = behavioral health; PH = physical health; PCP = primary care physician.

Current Practice

ACT is an evidence-based practice that provides community-based, comprehensive mental health services (Dixon, 2000) that are well suited for individuals with high-level behavioral health needs. Its ascendancy commenced 35 years ago in the wake of deinstitutionalization (Stein & Test, 1980); its importance was established during the rise of the evidence-based practice movement (Drake et al., 2001; Phillips et al., 2001). It is, perhaps, the most studied and well-articulated service model for individuals with severe mental illness. Its success rests primarily on yielding lower rates of psychiatric hospitalization and better residential stability (Marshall & Lockwood, 2003), two significant outcomes for an intervention designed to support deinstitutionalization.

At the core of the ACT model itself is a multidisciplinary team composed of social workers, nurses, psychiatric rehabilitation counselors, substance abuse counselors, psychiatrists, and peer support representatives. Ideally, the team adheres to a consumer-to-staff ratio of 10:1. ACT fidelity standards specify a number of service parameters, including the availability of round-the-clock coverage, direct team involvement in hospital admissions and discharges, and the stipulation that the majority (80%) of client contacts be conducted within the community rather than in an office-based setting. Nationally recognized guidelines also outline suggested staffing patterns and structural components, such as the occurrence of daily team meetings to review the status of all clients and coordinate their care. Better client outcomes (or more specifically, reductions in number of emergent hospital-based interventions) have been associated with greater fidelity to the ACT model (Burns et al., 2007).

ACT has also proven to be a stable platform from which to deliver other evidence-based mental health interventions, including integrated dual-diagnosis treatment, supported employment, and family psychoeducation endeavors (Drake & Deegan, 2008; Salyers & Tsemberis, 2007). Yet despite recent efforts to expand the idea of a “patient centered medical home” for hard-to-reach populations, evidence-based physical health interventions within ACT have largely gone unaddressed within the research literature. What has been recognized, however, is that integrating primary care services into existing community mental health programs could reduce the costs associated with the use of acute medical care (DeCoux, 2005) in the same way that ACT lessens the use of acute in-patient psychiatric care. In addition, integrating medical, psychiatric, and substance abuse treatment within a single program can improve clinical outcomes (Ceilley et al., 2006; Mauer & Druss, 2009).

Given that ACT is already a proven, resource-intensive model that serves those with high-level behavioral health care needs, and that it has become more widely instituted as evidence-based practices have become more prevalent (Carpinello, Rosenberg, Stone, Schwager, & Felton, 2002; Gold et al., 2003), ACT is ideally suited to function as an efficient vehicle for the delivery of integrated behavioral and primary health care within a community-based setting specifically through redefining the role of the ACT nurse.

ACT Nursing

It is clear that nursing is a vital component of ACT’s multidisciplinary team approach. McGrew, Pescosolido, and Wright (2003) studied ACT case managers’ perspectives on critical elements of ACT and found that having full-time nursing support was viewed as one of the most important ingredients of ACT, whereas Ryan, Garlick, and Happell (2006) reported that community mental health team members felt nurses provide an aspect of care that cannot be met by other health care professionals on the team. The specific interventions performed by ACT nurses vary, however, with Wallace, O’Connell, and Frisch (2005) identifying complex relationship building, medication management, surveillance, and case management as several examples.

The most commonly identified role of the ACT team nurse is working closely with the team psychiatrist to address consumers’ mental health needs related to medication management. In fact, Wallace et al. (2005) report that nearly two thirds of all encounters of mental health nurses with clients in the community involve medication management. From a practical standpoint, a primary responsibility of the ACT nurse then becomes the coordination and administration of psychotropic medications and the provision of consumer education about them. There is, however, little detailed information about other responsibilities and functions of an ACT nurse.

Ryan et al. (2006) report focus group findings from community health nurses working on “mental health teams” who describe how they assist allied health staff with coordination of medical aspects of care, but do not specify beyond “secondary consultation” (p. 101). Ceilley et al. (2006) suggest that there is a need for ACT team nurses to actively counsel and screen for client medical conditions, but they do not report that this is being done. White and Kudless (2008), in a qualitative study of community mental health nurses, including those working on ACT teams, report on the frustration that nurses feel when their “expertise in caring for consumers with complex co-morbid medical conditions” goes unrecognized and underutilized (p. 1079). This expertise was reported as including “the ability to do in-depth physical as well as psychological assessments, to triage, and to provide crisis care” (p. 1079). However, the emphasis was more on concerns with the current system and action steps to improve it.

In current practice, it is likely that ACT nurses regularly provide elements of primary and preventive care in addition to mental health services, although this aspect has not been explicitly defined and is likely inconsistent across teams. Community mental health nursing in other settings has been described as including engagement in a therapeutic relationship, triage and assessment, managing episodes of acute mental illness, managing medical aspects of care, medication profiling, education, and health promotion (Ryan et al., 2006). The relationship-building role, however, is perhaps the most important of these interventions, and one that is a prerequisite for other interventions. In fact, Wallace et al. (2005) suggest that creating relationships “is a primary goal of the nurses and is a basis for all other interactions” (p. 488). This is true regardless of whether nurses are working with clients to address physical or mental health needs, or both. What is also true is that it is becoming increasingly evident that clients are better served when their physical and mental health needs are addressed concurrently, because of the “inextricable nature” of mental and physical health and the consequences for clients when this inherent connectedness is not acknowledged (Weiss, Haber, Horowitz, Stuart, & Wolfe, 2009).

Integrated Care: Nursing/Primary Care Partnerships

ACT nurses are well positioned to facilitate the integration of primary care services within the ACT team by explicitly defining and expanding the range of physical health monitoring services they can provide. Given their current key role on the team; their training in physical and psychosocial assessment, pharmacology, and disease management; and the nature of the traditional nursing model of wellness and wholeness, they are the ideal point person to assume this responsibility. Furthermore, and just as important, they may also be viewed by clients as such; clients, therefore, may be more willing to engage. As Kane and Blank (2004) suggest, “Seeing one’s self as receiving care from a nurse who is addressing holistic health needs, not just mental health needs, may be more palatable” and less stigmatizing to clients than receiving services provided with a purely psychiatric intention (p. 557).

Although some ACT teams have used advanced practice nurses to provide physical health monitoring to clients (Kane & Blank, 2004), as noted above, the practice is not widely described in the literature. Most ACT teams currently attempt to address clients’ primary care needs by establishing linkages with outside primary care providers on a case-by-case basis. An alternative solution would be to embed primary care services within the ACT team, although such an approach has not been cited within the research literature. In either case, the use of an evidence-based model that supports a nursing/primary care partnership would provide a clear advantage in future efforts to integrate primary care into ACT.

Guided Care is the nurse/primary care physician partnership that was developed by Dr. Chad Boult and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University to improve outcomes for adults with complex health needs. Guided Care, which is based on the Chronic Care model, incorporates evidence-based processes with patient preferences (Boyd et al., 2007). Specifically, this unique partnership calls for a specially trained and certified Guided Care nurse to work closely with a small group of primary care physicians and their staff to provide comprehensive and coordinated chronic illness care to an identified panel of 50 to 60 high-risk older patients (Boyd et al., 2010). The processes of Guided Care (Boult, Giddens, Frey, Reider, & Novak, 2009) map closely with the current ACT nursing practices and are further described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Potential Incorporation of Guided Care Into Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) Nursing

| Guided Care Processes | ACT Nursing Correlate |

|---|---|

| Assessing the patient at home6 | ACT standards dictate that 80% of services are delivered in the field |

| Creating an evidence-based Care Guide and patient-friendly Action Plan | Client goal planning is integral to ACT services and strives to adapt evidence-based practice to consumer preference |

| Promoting patient self-management | Incorporation of mental health “Illness Recovery Management” programs |

| Monitoring the patient’s conditions monthly | ACT standards stipulate a minimum of two times per month consumer monitoring |

| Coordinating efforts of all health care providers | ACT nurses are the key link in behavioral and physical health coordination |

| Smoothing transitions between sites of care | ACT services in the field include visits to hospitals and other care facilities |

| Assessing, educating, and supporting the caregiver | ACT nurses are the main health education resource for the ACT team |

| Facilitating access to community resources | Community integration is a core value of ACT services |

Though some ACT nurses currently are assuming responsibilities similar to those of a Guided Care nurse, they generally do so unofficially and without recognition, and on a needs-based, reactive basis. Guided Care, in contrast, specifically outlines the responsibilities of the nurse’s role in this model and underscores the supervisory nature of her position in it.

It is important to note, however, that Guided Care lends itself to much more than a guideline for the nursing role. Its primary advantage is that it provides a clear blueprint for defining and structuring a collaborative partnership between ACT nurses and primary care providers, the establishment of which will be a key determinant in the success of an integrated program. There is no clear guidance for this partnership in the current ACT team structure, within which all members support the client in education and “activation” around health issues. However, in the Guided Care model, it is the nurse who is recognized—and serves—as the key coordinator of these group efforts.

Guided Care also outlines protocols and standards necessary for the development and implementation of needs-driven client care plans.

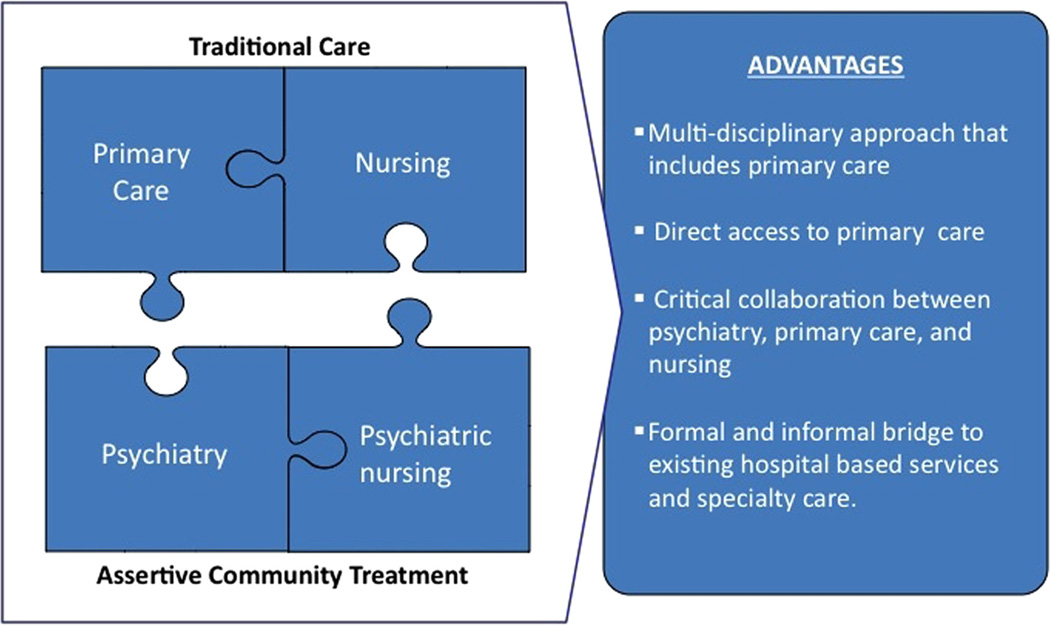

One way for ACT teams to implement the Guided Care model is to have the Guided Care–trained ACT nurse develop a partnership with an existing primary care practice, linking services with the practice’s primary care physician(s) and serving as key liaison for complex clients; in essence, functioning as a team member on both the ACT team and the primary care practice. Alternatively, primary care services could be embedded within an ACT team, which would ensure full on-site integration and further facilitate the partnership between nursing and primary care (Figure 2). Electronic health records are a key component of this partnership and will need to be in place in order to ensure seamless integration of services and effective collaboration between providers, either through the ACT team in the case of on-site integration, or through the primary care practice linkage. Either way, it is important to consider that perhaps the most critical aspect of the Chronic Care model is the interaction between the “prepared proactive practice team” and the “informed activated patient” (Wagner, 1998).

Figure 2.

Integrated Care Through Behavioral and Primary Care Partnerships

Case Example

We present the following case as an example of “real-life” implementation of care integration efforts. In the fall of 2008, a novel collaboration between a community mental health agency in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and a local academic medical center allowed for the transformation of what had been the agency’s traditional ACT mental health interventions into an integrated, interdisciplinary system for the delivery of comprehensive health care services to individuals with serious mental illness whose histories of homelessness increased their need for flexible, community-based primary care. In particular, ACT services were provided as part of a “housing first” initiative that effectively ends chronic homelessness for individuals with serious mental illness by providing immediate access to permanent, independent housing (Tsemberis, Gulcur, & Nakae, 2004). Through collaboration with the Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM) at Thomas Jefferson University, a primary care physician was embedded within the community mental health agency’s two “housing first” ACT teams. The role of the primary care physician included being present at each team’s morning meeting once a week and providing on-site and in-home integrated care in collaboration with the team nurses and psychiatrists one day a week. Follow-up primary care was provided both on-site and at the physician’s hospital-based practice, which is an NCQA (National Committee for Quality Assurance) recognized medical home. The academic practice also facilitates specialty care referrals in coordination with the ACT team. This integration of primary care was made possible through an individual research fellowship that allowed for flexibility in the physician’s schedule combined with institutional support as part of the DFCM’s commitment to piloting innovative approaches to care for individuals with complex conditions. The sustainability of integrated primary care is currently based on soliciting ongoing grant funding. However, this program may find support in current system redesign as new models of reimbursement for complex integrated care are being considered.

Although the integrated care team currently is collecting long-term health outcome data as part of its chronic disease registry, health surveillance at intake revealed that more than 90% of its clients have at least one chronic medical condition requiring ongoing interaction with the health system (The Chronic Care Model, 2006–2010); over half of them have two or more chronic conditions (Weinstein, Henwood, Matejkowski, & Santana, 2011). These include conditions such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and arthritis. The daily management of these chronic physical diseases imposes a considerable burden for which team nurses have assumed a significant role in ongoing collaborative chronic illness care and self-management support. For example, the nurses have been very active in interfacing with both inpatient and outpatient medical teams to facilitate complex, ongoing care issues, such as surgical and radiation treatment for locally advanced cancer and renal transplant evaluation for chronic renal failure. In situations such as these, advanced care could not have been accessed without team supports because of the complexities of the health care system.

In an effort to enhance the ability of the teams to respond to the complex physical health needs of our clients, the team nurses were trained in Guided Care nursing through the distance-learning curriculum at the Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing in the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. The team nurses found the interactive, web-based training to be valuable in extending the range of services they can provide to clients. In addition to the core content on the Guided Care model, the supplemental review of specific medical conditions, including diabetes and COPD, was helpful to the nurse whose expertise was predominately in psychiatric nursing. Now, in addition to their more traditional responsibilities, team nurses regularly and confidently assist clients with interventions more medical in nature than what they had previously provided, such as insulin adjustments and instruction in the use of respiratory inhalers.

Although the training was given specifically to the nurses, other key team members, including the psychiatrists and the clinical director, were receptive to learning about the Guided Care model, and actively embraced the information shared with them by the nurses. These exchanges enhanced the integration of care provided by the team to their clients.

Additionally, the management team has initiated the implementation of an enhanced electronic documentation system that has the flexibility to accommodate housing, case management, and clinical (psychiatric and physical health) tracking and monitoring. As it is just now being implemented, reports regarding integration facilitation outcomes would be premature.

An ongoing challenge for the care team remains communication and collaboration between it and outside providers, especially when it comes to transitioning clients between care providers and sites. However, the team expects to realize improvements in this area with further implementation of Guided Care and the specific recommendations the model provides for coordinating care transitions. With both nurses now trained, pilot implementation of Guided Care with a selected group of clients is planned for this year. During this pilot period, the team anticipates that it will better understand what modifications and additions may be necessary to adapt Guided Care to a population with high-level medical and behavioral health needs as well as histories of chronic homelessness, such as the inclusion of a module on issues specific to the metabolic effects of psychiatric medications, or one regarding adaptations to apartment living for newly housed individuals.

Future Directions

This case example illustrates a “real-world” implementation of primary care and ACT as an integrated health care delivery system with nursing as the keystone for coordination. Several unique strengths of the ACT model are essential to achieving person-centered care in “hard-to-reach” populations such as the one described here. These include team-based care, an emphasis on consumer choice, and incorporation of harm reduction principles.

Clearly, a multidisciplinary team is necessary to address the complex and multifaceted needs inherent in this population. The team must also strive to be recovery oriented by emphasizing consumer choice and a shared decision-making process as part of health promotion (Deegan & Drake, 2006; Drake & Deegan, 2008; Salyers & Tsemberis, 2007), and the ACT nurse can serve a key coordination role. Finally, given the high rate of co-occurring substance use inherent in this population, harm reduction principles are a necessary orientation toward service delivery. These principles can also be used to support and adapt medical evidence-based care recommendations to consumer preferences in areas of chronic disease management (Hayhow & Lowe, 2006).

All successful integrated care programs include a strong element of self-management support. And just as the Guided Care model can be adapted to meet the needs of those with high-level behavioral and medical health care challenges, so, too, can evidence-based programs for chronic disease self-management be adapted to meet the needs of the Quadrant 4 population (Druss et al., 2010). Guided Care specifically recommends linking patients with local chronic disease self-management programs, such as the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP; Boult et al., 2009). Beneficial, holistic, and self-care directed health and wellness programs can and should be incorporated into the integration of mental health and primary health care services (Druss et al., 2010; Van Citters et al., 2009), supported either directly within the ACT structure and managed by nursing or through ancillary community linkages.

In summary, we believe that the ACT model is well suited both theoretically and practically to serve as the foundation from which to address and resolve the significant physical and medical health disparities that exist in populations with serious mental illness. The ACT team nurse is uniquely trained and oriented to serve as the leader and coordinator of these efforts. In real-life practice, ACT nurses may already be addressing physical health needs of consumers on a daily basis, albeit unofficially and without recognition. However, well-developed care models, such as Guided Care, can provide additional guidelines and training to these nurses and a supporting infrastructure to the integrated primary care/behavioral health ACT model. Further integrated care development and service delivery can occur through direct community-based partnerships with primary care providers or by embedding a primary care provider within the ACT team itself. Additional research needs to be conducted in order to explore the feasibility and sustainability of such integrated models. However, this innovative work should be undertaken with urgency, given the great need that exists and the considerable potential benefits that may be realized.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the service teams and staff at Pathways to Housing–Philadelphia, Christine Simiriglia, Chief Operating Officer of Pathways to Housing–Philadelphia, and Sam Tsemberis, founder and Chief Executive Officer of Pathways to Housing for their dedication and innovation. We appreciate the input and guidance of Dr. Chad Boult at the Johns Hopkins Bloomerberg School of Public Health and the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing for providing training for our staff in Guided Care. We appreciate the support of the fellowship faculty at the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University, Drs. Howard Rabinowitz, James Diamond, and Christine Arenson, and the Departmental Chairman, Dr. Richard Wender.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article:

Dr. Weinstein’s research at Pathways to Housing is partially supported by a Heath Resources and Service Administration Faculty Development in Primary Care Award (No.: 5 D55HP10334-02-00 PI Howard Rabinowitz). Mr. Henwood’s research was supported by grant 5F31MH083372 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Author Roles

L. C. Weinstein and B. F. Henwood collaborated to develop and write the initial draft of the article. J. W. Cody contributed to the ACT Nursing and Integrated Care sections and overall editing. M. Jordan and R. Lelar contributed to the Integrated Care and Case Example sections.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Boult C, Giddens J, Frey K, Reider L, Novak T. Guided care: A new nurse–physician partnership in chronic care. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Boult C, Shadmi E, Leff B, Brager R, Dunbar L, Wegener S. Guided care for multi-morbid older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47:697–704. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.5.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Reider L, Frey K, Scharfstein D, Leff B, Wolff J, Boult C. The effects of guided care on the perceived quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: 18-month outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:235–242. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1192-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Catty J, Dash M, Roberts C, Lockwood A, Marshall M. Use of intensive case management to reduce time in hospital in people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-regression. British Medical Journal. 2007;335:336–340. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39251.599259.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpinello SE, Rosenberg L, Stone J, Schwager M, Felton CJ. Best practices: New York State’s campaign to implement evidence-based practices for people with serious mental disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:153–155. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceilley JW, Cruz M, Denko T. Active medical conditions among patients on an assertive community treatment team. Community Mental Health Journal. 2006;42:205–211. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-9019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Chronic Care Model. Improving chronic illness care. 2006–2010 Retrieved from http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=The_Chronic_Care_Model&s=2. [Google Scholar]

- Collins C, Hewson DL, Munger R, Wade T. Evolving models of behavioral health integration in primary care. New York, NY: Milbank Memorial Fund; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.milbank.org/reports/10430EvolvingCare/10430EvolvingCare.html. [Google Scholar]

- Colton C, Manderscheid R. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3(2):1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoux M. Acute versus primary care: The health care decision making process for individuals with severe mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2005;26:935–951. doi: 10.1080/01612840500248221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deegan PE, Drake RE. Shared decision making and medication management in the recovery process. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:1636–1639. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.11.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Assertive community treatment: Twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:759–765. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Deegan P. Are assertive community treatment and recovery compatible? Commentary on “ACT and recovery: Integrating evidence-based practice and recovery orientation on assertive community treatment teams”. Community Mental Health Journal. 2008;44:75–77. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, Lehman AF, Dixon L, Mueser KT, Torrey WC. Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:179–182. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein SA, Bona JR, Fricks L, Jenkins-Tucker S, Lorig K. The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: A peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;118:264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold P, Meisler N, Santos A, Keleher J, Becker D, Knoedler W. The program of assertive community treatment: Implementation and dissemination of an evidence-based model of community-based care for persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2003;10:290–303. [Google Scholar]

- Hayhow BD, Lowe MP. Addicted to the good life: Harm reduction in chronic disease management. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;184:235–237. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane CF, Blank MB. NPACT: Enhancing programs of assertive community treatment for the seriously mental ill. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40:549–559. doi: 10.1007/s10597-004-6128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M, Lockwood A. Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental disorders. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2003;(2):CD001089. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauer BJ, Druss BG. Mind and body reunited: Improving care at the behavioral and primary healthcare interface. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research. 2009;37:529–542. doi: 10.1007/s11414-009-9176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew JH, Pescosolido B, Wright E. Case managers’ perspectives on critical ingredients of assertive community treatment and on its implementation. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:370–376. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morden NE, Mistler LA, Weeks WB, Bartels SJ. Health care for patients with serious mental illness: Family medicine’s role. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2009;22:187–195. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.02.080059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SD, Burns BJ, Edgar ER, Mueser KT, Linkins KW, Rosenheck RA, McDonel Herr EC. Moving assertive community treatment into standard practice. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:771–779. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatt EE, Munetz MR, Ritter C. An examination of premature mortality among decedents with serious mental illness and those in the general population. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:663–668. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R, Garlick R, Happell B. Exploring the role of the mental health nurse in community mental health care for the aged. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2006;27:91–105. doi: 10.1080/01612840500312902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: Is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyers MP, Tsemberis S. ACT and recovery: Integrating evidence-based practice and recovery orientation on assertive community treatment teams. Community Mental Health Journal. 2007;43:619–641. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LI, Test MA. Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1980;37:392–397. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(4):651–656. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Citters AD, Pratt SI, Jue K, Williams G, Miller PT, Xie H, Bartels SJ. A pilot evaluation of the In SHAPE individualized health promotion intervention for adults with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal. 2009;46:540–552. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9272-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace T, O’Connell S, Frisch SR. What do nurses do when they take to the streets? An analysis of psychiatric and mental health nursing interventions in the community. Community Mental Health Journal. 2005;41:481–496. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-5086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein LC, Henwood BF, Matejkowski J, Santana A. Moving from street to home: Health status of entrants to a Housing First Program. Journal of Primary Care and Community Health. 2011;2(1):11–15. doi: 10.1177/2150131910383580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SJ, Haber J, Horowitz JA, Stuart GW, Wolfe B. The inextricable nature of mental and physical health: Implications for integrative care. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2009;15:371–382. doi: 10.1177/1078390309352513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JH, Kudless M. Valuing autonomy, struggling for an identity and a collective voice, and seeking role recognition: Community mental health nurses’ perception of their roles. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2008;29:1066–1087. doi: 10.1080/01612840802319779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]