Abstract

Background

Low rates of minority recruitment in prevention studies may reduce the generalizability of study results to minority populations, including African Americans. High African American accrual to prevention studies requires additional resources and focused efforts.

Objective

To analyze the impact of Minority Recruitment Enhancement Grants (MREGs) on African American recruitment to the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT).

Results

Fifteen of 427 SELECT sites received MREGs after they demonstrated early success in minority recruitment. After receiving the grants, the average monthly rate of African American recruitment at these sites increased from 27.2% to 31.5%, and total average monthly recruitment also increased. Sites that did not receive grants, including sites that did not apply, increased average monthly African American recruitment from 11.0% to 14.6% but declined in total average monthly recruitment.

Conclusions and Implications

Sites who received MREGs modestly increased both the proportion of African American recruits and total recruits. These results are tempered by the high cost of the intervention, the relatively low number of SELECT sites that applied for the grants and the administrative delays in implementation. Nevertheless, targeted grants may be a useful multi-site intervention to increase African American accrual for a prevention study where adequate African American recruitment is essential.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is a major health problem, second only to non-melanoma skin cancer as the most common cancer in men in the United States. Furthermore, the rate of prostate cancer is higher and the mean age-of-onset is younger in African Americans than in non-African Americans [1 – 3]. Prostate cancer prevention trials provide an important opportunity to test interventions that might reduce the burden of the disease [4]. However, the results of such trials offer unclear applications to African Americans if there is low African American participation.

This article examines accrual patterns in a post hoc analysis to determine if sites that received additional recruitment funding increased African American and total accrual in the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT), a prostate cancer prevention study. Specifically, we address whether the additional financial support resulted in increased African American accrual and increased total accrual at individual sites and within the group of funded sites. We also assess site recruitment levels based on funding by comparing accrual between sites with and without additional funding during comparable time periods.

Background

The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) was the first large, cooperative group randomized trial for the prevention of prostate cancer in healthy men. [5] The accrual goal for African American men was set at eight percent to mirror the estimate of African American men age ≥ 55 years in the US population. Minority recruitment strategies for PCPT included trainings and workshops presented to study staff during semiannual meetings; development and distribution of minority-focused recruitment materials; using consultants to conduct trainings and assist specific sites in their recruitment efforts; and piloting the use of minority outreach recruiters at five sites. In spite of these efforts, the African American accrual goal remained unmet, with only four percent African American men accrued. Efforts to enhance minority participation in PCPT were not initiated until one year after the study was activated, which left only two years to develop and implement these recruitment strategies before the study closed to accrual. In addition, about 2/3 of the accrual goal was met in the first year of recruitment, so any attempted impact on African American accrual after that time would have a minimal effect.

The PCPT minority recruitment experience suggests that successful recruitment of African American men into a prostate cancer prevention trial requires extensive planning so that recruitment efforts can be initiated at trial activation. Infrastructure to support systematic efforts to recruit minority participants and a long-term commitment from funding agencies are also needed. [6–8] Other known barriers commonly cited to impede minority recruitment must also be addressed, such as the attitudes, knowledge and beliefs of potential minority recruits and their referring physicians, as well as trial designs and economics [9–23].

Some of the minority recruitment lessons learned from PCPT were applied to SELECT, the next large cooperative group prostate cancer prevention study. SELECT is designed to evaluate the effect of selenium and vitamin E on the clinical incidence of prostate cancer. The SELECT overall accrual goal was 32,400 healthy men with a five-year uniform accrual period. The study had a pre-established goal of 24% overall minority representation: 20% African American, three percent Hispanic and one percent Asian/Pacific Islander [24].

Prior to trial activation, SELECT took several steps to meet African American and other minority accrual goals. First, the eligibility criteria were expanded by including men with co-morbid illnesses and lowering the age criterion for African American men from 55 to 50 years old. Sites that were likely to have high African American recruitment potential were sought, such as sites from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial and the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trials with proven track records in minority recruitment, as well as sites affiliated with the Department of Veteran Affairs Cooperative Studies Program (VACSP), which has a strong track record in minority recruitment. [25] SELECT also developed a national infrastructure to support minority recruitment, which included adding the Minority and Medically Underserved Subcommittee (MMUS) to the SELECT Recruitment and Adherence Committee (RAC). After trial activation, SELECT hired a full-time MMUS recruitment and adherence coordinator and provided resources to maximize free media opportunities for study promotion, such as Prostate Cancer Awareness Month, Minority Cancer Awareness Week and Father’s Day. Finally, SELECT provided additional funds in the form of Minority Recruitment Enhancement Grants (MREGs) to sites with the potential to increase minority enrollment. [26]

Five months after accrual to the study started, SELECT was accruing participants at nearly twice the planned rate. Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander accrual met or exceeded the target accrual rates, while African American accrual was only about half the targeted accrual rate. Because African American accrual was much lower than anticipated and it appeared that accrual would close in less than five years, SELECT had to respond quickly to boost African American accrual. SELECT met its overall accrual goal in less than three years and closed to accrual shortly thereafter with 35,533 participants, of whom 14.9% were African American. [26]

Due to the shortened accrual period, a targeted yet flexible intervention was needed to increase African American accrual. The primary focus was on sites that had the potential to enroll minority participants, especially African American participants. SELECT sites already enrolling high numbers of African American men often had developed relationships with their communities which allowed them to engage African Americans and their health care providers in clinical research and clinical trial participation. By providing additional financial resources to these sites, we hoped to further augment their ability to accrue minority participants to SELECT.

Six months after accrual to SELECT began, members of the SELECT RAC and the recruitment and adherence staff of the Statistical Center staff met with the National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Prevention, the SELECT funding agency, to discuss developing a set of site grants to increase African American and other minority accrual to SELECT. These site grants became the MREGs. The first request for applications (RFA) for an MREG was issued in April 2002, eight months after accrual to SELECT began, and the second RFA was issued about one year later. Sites were notified of awards within one to three months following receipt of their application. SELECT accrual ended in June 2004, nine months after the last site received notification of the final MREG award.

The MREG was a $50,000 site grant designed to increase minority accrual by enhancing recruitment strategies at sites with the potential to increase African American and/or Hispanic recruitment. An additional purpose of the MREG was to document the sequence and variety of recruitment strategies used by sites for the benefit of future studies. While all SELECT sites could apply for an MREG, applicants were required to demonstrate the ability to recruit minorities and/or provide evidence of access to a high number of potential minority participants. Awarded sites were responsible for providing the design and implementation of recruitment strategies, including staffing. Activities supported by the MREG included, but were not limited to: salary support for a minority outreach coordinator, participant gas and parking reimbursement, minority recruitment materials, recruitment advertisements in local media, food and supplies for recruitment meetings and postage for mass mailings.

Methods

To determine whether MREG funding impacted African American and overall accrual, a post hoc analysis was developed to compare accrual between sites that ever received an MREG (MREG sites) and sites that were not awarded or did not apply for an MREG (non-MREG sites), and to compare accrual rates within MREG sites before and after funding. The analysis had to take into account the varying lengths of accrual between sites and the small proportion of MREG sites to non-MREG sites. It also had to accommodate varying funding dates for MREG sites and establish a similar time frame for non-MREG sites, to enable comparison between the groups and to account for accrual trends over time. To accomplish this and make comparisons between sites more manageable, we measured accrual using a weighted monthly average and examined the average monthly accrual rates and the total average monthly accrual. To simplify the analyses, we did not consider the amount of funding each site received but only the event of having received MREG funding. We also did not attempt to compare MREG sites with groups of “similar” non-MREG sites, due to the lack of available data to define “similar” sites.

To establish a reasonable and equitable time frame for comparisons, we divided the overall accrual period into two periods: pre- and post-funding. For MREG sites, the funding date was determined by the month of first MREG funding and is unique to each site. For all non-MREG sites, November 2002 was used because all the initial MREG sites had received their grant funds by this time.

The accrual start date was specific to each site and is the month the site randomized its first participant to SELECT, between August 2001 and April 2004. All sites were assumed to continue accrual until June 2004. Seventy-two percent of sites initiated accrual in 2001 and 22% in 2002. The overall median accrual time was 33 months, with a range of 3 to 35 months.

We calculated the average monthly accrual for each group, MREG and non-MREG, African American and total, for each time period: pre-MREG, post-MREG and overall. Total average monthly accrual for a specific group is calculated as the sum of the average monthly accrual across sites for a particular period.

Results

Study Sites Funded for the First and Second MREG

Although all SELECT sites were allowed to apply for the first MREG award, only 32 SELECT sites (<10 %) responded to the first RFA; 11 grants were awarded in this round of funding in mid-2002. At the time the first RFA was announced, 367 active SELECT sites had accrued 10,671 participants, of which only 11% were African American. Other minority accrual was on track and stayed on target for the remainder of accrual. After the MREG program was implemented and when overall SELECT accrual reached 23,000, African American accrual was 14%, still below the 20% target. Therefore the NCI awarded SELECT additional funding to issue another RFA. As a result of this second round of funding, seven existing MREG sites and four new sites were awarded MREGs in mid-2003. When accrual closed in June 2004, SELECT had 35,533 participants, of which 14.9% were African American. In summary, 15 sites received a combined $1.1 million in grants over two years to increase African American and other minority accrual. The award dates, types of sites and award amounts for all MREG sites are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Minority Recruitment Enhancement Grant Awardees Summary

| Site No. | Type of Sitea | 1st MREG Funding Date |

2nd MREG Funding Date |

Total Funds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | Academic Center | July 2002 | July 2003 | $100,000 |

| 2b | Academic Center | July 2002 | July 2003 | $100,000 |

| 3 | Cancer Program | July 2002 | July 2003 | $100,000 |

| 4 | CCC | July 2002 | July 2003 | $100,000 |

| 5 | VACSP | July 2002 | July 2003 | $100,000 |

| 6 | Academic Center | July 2002 | $50,000 | |

| 7c | Academic Center | July 2002 | $50,000 | |

| 8 | Academic Center | July 2002 | $50,000 | |

| 9 | CCOP | August 2002 | August 2003 | $100,000 |

| 10 | VACSP | September 2002 | September 2003 | $100,000 |

| 11b | MBCCOP | October 2002 | $50,000 | |

| 12 | Cancer Program | April 2003 | $50,000 | |

| 13 | CCOP | April 2003 | $50,000 | |

| 14 | Academic Center | August 2003 | $50,000 | |

| 15b | Community Health Center | August 2003 | $50,000 | |

| TOTALS: | 11 MREGS | 11 MREGs | $1,100,000 |

Notes:

Academic Center: Facility is also involved in higher education and research.

Cancer Program: Facility that has a cancer program, may or may not be an academic center, not an NCI designated Cancer Center or Comprehensive Cancer Center.

CCOP: Community Clinical Oncology Program. A large network that allows community physicians to participate in NCI sponsored clinical cancer trials.

CCC: Comprehensive Cancer Center. NCI designated cancer center that has research activities in each of three major areas: laboratory, clinical, and population-based research, with substantial transdisciplinary research that bridges these scientific areas. The CCC must also demonstrate professional and public education and dissemination of clinical and public health advances into the community it serves.

Community Health Center: Facility that provides public health services.

MBCCOP: Minority - Based Community Clinical Oncology Program allows racial and ethnic minority cancer patients to have access to quality medical care in their own communities.

VACSP: Department of Veteran Affairs Cooperative Studies Program. Department of Veterans Affairs provides medical care to veterans and their family members.

Site had a large percentage of African American recruits pre-MREG. MREG was awarded to maintain already high African American recruitment.

Large site with access to large numbers of Hispanic and African American recruits. MREG was awarded to enhance both African American and Hispanic recruits.

Table 2 presents African American recruitment performance for individual MREG sites before and after receipt of MREG funding. Each MREG site is unique, in months spent accruing before and after receiving the MREG award, number of participants and the number and percent of African American recruits. Nearly all MREG sites increased both their percent of African American accrual and the average number of African American recruits per month. Sites 2, 11 and 15 already had large percentages of African American recruits prior to receiving the MREG. These sites received the MREG to maintain their overall recruitment rates while maintaining their high percentages of African American recruits; it was not expected that the percentage of African American recruits at these sites would increase. Site 7, the largest MREG site, had access to large populations of African American and Hispanic men, and it was expected to maintain its rate of recruitment but increase the percentage of both African American and Hispanic recruits. The actual outcome was that the total accrual rate increased without increasing the rate of African American accrual.

Table 2.

Individual MREG Site Performance Before and After MREG Funding

| Pre MREG Funding | Post MREG Funding | Overall | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site No. |

# Accrual months |

Total recruits |

# African American recruits (%) |

# Accrual months |

Total recruits |

# African American recruits (%) |

# Accrual months |

Total recruits |

# African American recruits (%) |

|||

| 1 | 11 | 137 | 55 | (40%) | 24 | 264 | 138 | (52%) | 35 | 401 | 193 | (48%) |

| 2 | 10 | 28 | 21 | (75%) | 24 | 177 | 162 | (92%) | 34 | 205 | 183 | (89%) |

| 3 | 11 | 85 | 16 | (19%) | 24 | 44 | 12 | (27%) | 35 | 129 | 28 | (22%) |

| 4 | 10 | 154 | 33 | (21%) | 24 | 233 | 68 | (29%) | 34 | 387 | 101 | (26%) |

| 5 | 10 | 20 | 4 | (20%) | 24 | 144 | 58 | (40%) | 34 | 164 | 62 | (38%) |

| 6 | 10 | 8 | 1 | (13%) | 24 | 52 | 15 | (29%) | 34 | 60 | 16 | (27%) |

| 7 | 11 | 319 | 15 | (5%) | 24 | 1259 | 58 | (5%) | 35 | 1578 | 73 | (5%) |

| 8 | 9 | 146 | 55 | (38%) | 24 | 99 | 65 | (66%) | 33 | 245 | 120 | (49%) |

| 9 | 11 | 118 | 18 | (15%) | 23 | 181 | 54 | (30%) | 34 | 299 | 72 | (24%) |

| 10 | 13 | 69 | 23 | (33%) | 22 | 72 | 31 | (43%) | 35 | 141 | 54 | (38%) |

| 11 | 13 | 34 | 32 | (94%) | 21 | 34 | 31 | (91%) | 34 | 68 | 63 | (93%) |

| 12 | 19 | 119 | 27 | (23%) | 15 | 43 | 5 | (12%) | 34 | 162 | 32 | (20%) |

| 13 | 17 | 40 | 3 | (8%) | 15 | 71 | 20 | (28%) | 32 | 111 | 23 | (21%) |

| 14 | 22 | 230 | 23 | (10%) | 11 | 141 | 40 | (28%) | 33 | 371 | 63 | (17%) |

| 15 | 12 | 93 | 90 | (97%) | 11 | 93 | 93 | (100%) | 23 | 186 | 183 | (98%) |

| 12.6 | 1600 | 416 | (26%) | 20.7 | 2907 | 850 | (29%) | 33.3 | 4507 | 1266 | (28%) | |

Notes for Table 2:

# Accrual months: Total months the site spent accruing to SELECT, starting from the first month of accrual within the stated period. Some sites did not begin accrual until after November 2002. Summary is average for all sites.

Total recruits: Total participants accrued over the stated period. Summary is sum of all sites.

# African American recruits (%): Total and percent of African American participants accrued over the stated period. Summary is sum of all sites and percent for all sites.

A comparison of the accrual data for MREG and non-MREG sites is presented in Table 3. Data are shown for overall accrual, as well as accrual before and after the time of initial funding. Accrual figures are presented as totals for the various accrual periods and as monthly averages.

Table 3.

SELECT Accrual Summary: Before and After MREG Funding

| Pre MREG Funding | Post MREG Funding | Overall | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # African American |

Total | Average Rate |

# African American |

Total | Average Rate |

# African American |

Total | Average Rate |

|

| MREG Study Sites (n=15) | |||||||||

| Total participants | 416 | 1,600 | 850 | 2,907 | 1,266 | 4,507 | |||

| Average monthly accruala | 35.8 | 131.9 | 27.2% | 43.0 | 136.3 | 31.5% | 39.7 | 134.0 | 29.6% |

| Non-MREG Study Sites (n=412) | |||||||||

| Total participants | 1,620 | 14,424 | 2,409 | 16,602 | 4,029 | 31,026 | |||

| Average monthly accruala | 131.1 | 1,192.1 | 11.0% | 124.3 | 849.4 | 14.6% | 131.6 | 995.9 | 13.2% |

| All Sites (n=427) | |||||||||

| Total participants | 2,036 | 16,024 | 3,259 | 19,509 | 5,295 | 35,533 | |||

| Average monthly accruala | 166.9 | 1324.0 | 12.6% | 167.3 | 985.7 | 17.0% | 171.3 | 1129.9 | 15.2% |

Notes:

A time-weighted average is used, based on when each site accrued its first participant to SELECT.

The 15 MREG sites accrued 4,507 participants with 1,266 African American participants. The average monthly African American accrual rate for these sites was 27.2% prior to funding and 31.5% after funding, an increase of 4.3%. The 412 non-MREG sites accrued 31,026 participants with 4,029 African American participants. The average monthly African American accrual rate for these sites was 11.0% prior to funding and 14.6% after funding, an increase of 3.6%. The MREG sites increased their total and African American accrual rates post-funding, and the non-MREG sites had decreased accrual rates.

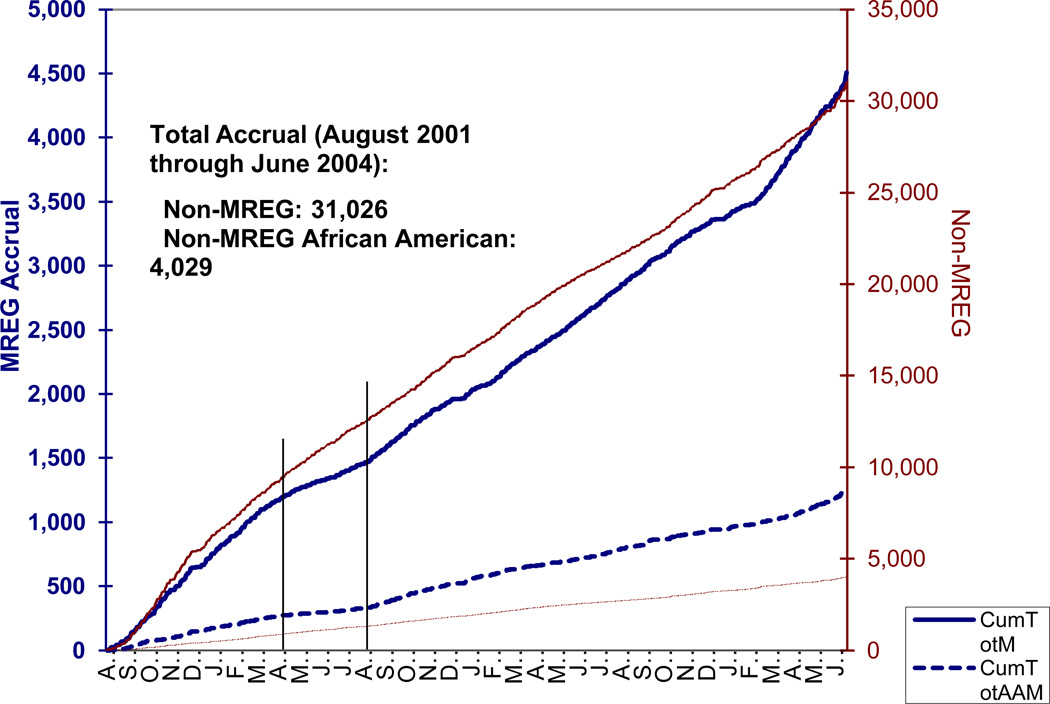

Figure 1 shows the cumulative accrual for MREG and non-MREG sites, total and for African American accrual alone. In general, overall accrual for MREG and non-MREG sites is fairly steady throughout the accrual period; however, there are some important inflection points, denoted by vertical lines on the graph. Initial accrual at MREG and non-MREG sites was very swift, from the time the study opened to around April 2002. After this time, accrual slowed down for all sites. The MREG sites show a greater decrease than non-MREG sites after April 2002, but then accrual for these sites increased again after August 2002, about the time that many of them received their first round of MREG funding. All sites show a jump in accrual shortly before the study closed to accrual, reflecting the timing of the announcement in March 2004 that the study would close to accrual in June 2004. The MREG sites showed a jump in overall accrual starting in January 2004 that persisted until June 2004, due in part to increased recruitment at Site 7.

Figure 1.

Cumulative SELECT Accrual for MREG and Non-MREG Study Sites

African American accrual was also generally steady throughout the accrual period for both MREG and non-MREG sites, with accrual patterns similar to overall accrual with one notable exception in non-MREG African American accrual. Although the proportion of African American participants at non-MREG sites increased after November 2002, it appears that the number of African American participants accrued over time remained constant. Like overall MREG accrual, MREG African American accrual slowed down after April 2002 and picked up after August 2002. The last few months of accrual shows a very high African American accrual rate for the MREG sites, while the non-MREG sites’ African American accrual is steady to the end.

We estimated the additional African American participants accrued due to MREG funding to be between 150 and 530 participants. The low estimate is derived from Table 3, using a “by the numbers” approach. Figure 1 provides additional information, showing a marked decrease in accrual for the MREG sites in the four months prior to August 2002, which is the period just before most MREG sites received their first grant. Had the sites not received grant funds, they may have continued to accrue at this lower rate. If so, the MREG resulted in up to 530 additional African American participants accrued. Similarly, we estimated the total participants accrued due to MREG funding to be between 960 and 1200.

Discussion

Assuming that accrual patterns for the MREG sites would have been similar to those for the non-MREG sites had they not received funding, the MREG sites increased African American accrual when compared to non-MREG sites. The funding allowed the MREG sites to accrue between 150 and 530 additional African American participants and 960 to 1200 additional participants overall than if they had not received funding. While MREG sites were chosen for their ability to recruit African American participants, not all of them increased African American accrual; some MREG sites used the funds to maintain accrual or even continue accruing. Although SELECT did not meet the target of 20% for African American accrual, the MREG sites did contribute to the final African American accrual rate.

When non-MREG accrual slowed down around April 2002, non-MREG African American accrual remained steady. If overall accrual had not been so rapid, SELECT may have gradually increased African American accrual, although not to the 20% level. MREG sites, however, showed a greater drop in overall accrual than the non-MREG sites and a slight decrease in African American accrual between April and August 2002. This may indicate that their existing financial resources were being depleted and they were unable to continue their recruitment efforts in the absence of assistance. Had the MREG not been available, these sites likely would have made a reduced contribution to African American accrual. Starting approximately August 2002, the MREG sites’ accrual increased, corresponding to the time that many first-round MREG funds were available.

The effectiveness of the MREG on African American and total recruitment varied among the MREG sites. Most sites increased their percents of African American recruits, but a few accrued smaller proportions of African Americans. Some sites which initially had over 90% African American recruits maintained their percentages. The wide range of strategies employed at the various MREG sites may also account for some of the variation in MREG site recruitment results. Additionally, the largest MREG site focused on Hispanic recruitment and did not significantly improve African American recruitment after receiving MREG funding, even though its stated intent was to increase both Hispanic and African American accrual.

MREG funding was implemented after the trial was open and sites were actively accruing participants, which may have contributed to fewer than expected numbers of sites applying for an MREG. Most sites would have established their staff assignments to SELECT and budgeted funds and time commitments accordingly. In addition, a number of sites experienced delays in receipt or access to funding within their own administrations, which resulted in further hiring and implementation delays. These data lend further support for initiating minority recruitment strategies before trial activation and implementing them at the onset of accrual, which would enable sites to take full advantage of the additional support.

Some of the barriers to implementing African American recruitment plans reported by MREG sites include the above-mentioned funding and staffing delays, the absence of staff during summer vacation season, staff illness, possible participant distrust of clinical trials and the additional time required to recruit African American men. Sites also reported they saw men who came to screenings but lived outside the SELECT study site area as well as large numbers of African American men who came for prostate cancer screening but were too young to be eligible for SELECT.

A portion of the increase in overall recruitment among the MREG may be due to implementing multiple African American recruitment strategies that promoted prostate screening and SELECT. These include: SELECT Sunday, a faith-based strategy that kicked off in November 2003; African American media personalities participating in limited media spots; and a barbershop initiative preceding the release of the movie, Barbershop 2 that opened February 6, 2004. Although we are unable to determine how these strategies individually contributed to the increased rate of recruitment that occurred among the MREG sites it is likely due to a combination of these new initiatives and the MREG funds.

The general strategy of providing additional funding to selected sites for the purpose of recruiting in the African American population was modestly successful for SELECT. As a group, the MREG sites demonstrated both the willingness and potential resources necessary to increase African American recruitment; most of them already had better than average African American recruitment prior to receiving MREG funds and then increased African American accrual after receiving MREG funds. The additional funds allowed these sites to maintain or increase their African American accrual. Further analysis of the specific strategies implemented at the site level to determine which strategies were successful will be in a subsequent paper.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by the following PHS Cooperative Agreement grant numbers awarded by the National Cancer Institute, DHHS:CA37429, P30-CA015704 and supported in part by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM)

References

- 1.American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2007. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007. [last accessed 12/14/2007]. http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2007PWSecured.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures for African American 2007–2008. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007. [last accessed 12/14/2007]. http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2007AAacspdf2007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; [Last accessed 12/14/2007]. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2004. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/, based on November 2006 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson IM, et al. Phase III prostate cancer prevention trials: are the costs justified? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(32):8161–8164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feigl P, et al. Design of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) Control Clin Trials. 1995;16(3):150–163. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(94)00xxx-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moinpour CM, et al. Minority recruitment in the prostate cancer prevention trial. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10(S8):S85–S91. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds T. PCPT Update: Enrollment mounts, but minority participation lags. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1500–1501. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.20.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coltman CA, Jr, Thompson IM, Jr, Feigl P. Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) update. Eur Urol. 1999;35:544–547. doi: 10.1159/000019895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovato LC, Hill K, Hertert S, Hunninghake DB, Probstfield JL. Recruitment for controlled clinical trials: literature summary and annotated bibliography. Control Clin Trials. 1997;18:328–357. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorelick PB, Harris Y, Burnett B, Bonecutter FJ. The recruitment triangle: reasons why African Americans enroll, refuse to enroll, or voluntarily withdraw from a clinical trial. An interim report from the African-American Antiplatelet Stroke Prevention Study (AAASPS) J Natl Med Assoc. 1998;90:141–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giuliano AR, Mokuau N, Hughes C, et al. Participation of minorities in cancer research: the influence of structural, cultural, and linguistic factors. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:S22–S34. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods VD, Montgomery SB, Herring RP. Recruiting black/African American men for research on prostate cancer prevention. Cancer. 2004;100:1017–1025. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell IJ, Gelfand DE, Parzuchowski J, Heilburn L, Franklin A. A successful recruitment process of African American men for early detection of prostate cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:1880. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gotay CC. Accrual to cancer clinical trials: directions from the research literature. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:569–577. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90214-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCaskill-Stevens W, Pinto H, Marcus AC, et al. Recruiting minority cancer patients into cancer clinical trials: a pilot project involving the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group and the National Medical Association. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1029–1039. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fouad MH, Partridge E, Green BL, et al. Minority recruitment in clinical trials: a conference at Tuskegee, researchers and the community. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:S35–S40. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris Y, Gorelick PB, Samuels P, Bempong I. Why African Americans may not be participating in clinical trials. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88:630–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Millon-Underwood S, Sanders E, Davis M. Determinants of participation in state-of-the-art cancer prevention, early detection screening, and treatment trials among African-Americans. Cancer Nurs. 1993;16:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green BL, Partridge EE, Fouad MN, Kohler C, Crayton EF, Alexander L. African-American attitudes regarding cancer clinical trials and research studies: results from focus group methodology. Ethn Dis. 2000 Winter;10:76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Probstfield JL, Wittes JT, Hunninghake DB. Recruitment in NHLBI population-based studies and clinical trials: data analysis and survey results. Control Clin Trials. 1987;8:141S–149S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(87)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paskett ED, DeGraffinreid CR, Tatum CM, Margitic SE. The recruitment of African-Americans to cancer prevention and control studies. Prev Med. 1996;25:547–553. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Probstfield JL. The clinical trial prerandomization compliance (adherence) screen. In: Cramer JA, Spilker Beds, editors. Patient Compliance in Medical Practice and Clinical Trials. New York: Raven Press; 1991. pp. 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lippman SM, et al. Designing the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(2):94–102. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oddone EZ, Olsen MK, Lindquist JH, et al. Enrollment in clinical trials according to patient’s race: experience from the VA Cooperative Studies Program (1975–2000) Controlled Clinical Trials. 2004;25:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook ED, et al. Minority recruitment to the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) Clin Trials. 2005;2(5):436–442. doi: 10.1191/1740774505cn111oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]