Abstract

Pathways’ Housing First represents a radical departure from traditional programs that serve individuals experiencing homelessness and co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. This paper considered two federally funded comparison studies of Pathways’ Housing First and traditional programs to examine whether differences were reflected in the perspectives of frontline providers. Both quantitative analysis of responses to structured questions with close-ended responses and qualitative analysis of open-ended responses to semistructured questions showed that Pathways providers had greater endorsement of consumer values, lesser endorsement of systems values, and greater tolerance for abnormal behavior that did not result in harm to others than their counterparts in traditional programs. Comparing provider perspectives also revealed an “implementation paradox”; traditional providers were inhibited from engaging consumers in treatment and services without housing, whereas HF providers could focus on issues other than securing housing. As programs increasingly adopt a Housing First approach, implementation challenges remain due to an existing workforce habituated to traditional services.

Keywords: Housing First, frontline providers, serious mental illness, homelessness, supportive housing

Examining Provider Perspectives within Housing First and Traditional Programs Pathways’ Housing First (PHF) represents a radical departure from traditional programs that serve individuals experiencing homelessness and co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders (Tsemberis, 2010). Rather than viewing permanent housing as a goal to be obtained via treatment compliance and abstinence, i.e., a “treatment first” (TF) approach, PHF consumers are placed in permanent, independent apartments and providers work with consumers regardless of their symptoms, substance abuse, or whether they participate in formal treatment (Padgett, Gulcur, & Tsemberis, 2006; Tsemberis, Gulcur, & Nakae, 2004). This fundamental difference between PHF and TF programs—that is, considering housing as an input or intervention rather than an output or outcome (Newman, 2001)—is not only structural but also philosophical. PHF is said to be predicated on principles of consumer choice and recovery rather than an assumption of provider expertise (Tsemberis, 2010). Instead of custodial care, consumers are encouraged to live in normative, community settings and take risks that foster a sense of autonomy (Blanch, Carling, & Ridgway, 1988; Rog, 2004). This includes not only choosing type of living situation but also deciding whether to take psychiatric medications or abstain from drugs and alcohol (Salyers & Tsemberis, 2007). This approach, which openly embraces harm reduction, has been met with past skepticism (Felton, 2003), yet research has overwhelmingly demonstrated that PHF consumers are able to maintain independent apartment living and manage multiple health conditions when provided with flexible supports (Pearson et al., 2009; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration [SAMHSA], 2007; Tsemberis et al., 2004). Despite working with the same target population, PHF providers work in organizational settings that reflect these structural and philosophical differences from TF program models. Initial research suggested that PHF providers approach service delivery differently than TF providers (Henwood, Stanhope, & Padgett, 2011), yet more research is needed as PHF programs spread and the need for staff training increases. This paper presents data collected in two federally funded studies that compared PHF and TF programs, and uses a mixed-method approach to investigate whether and how differences in approaches are reflected in the views of frontline providers. Theresearch questions addressed by this paper include: (1) Do providers working in PHF versus TF programs endorse different views, values, and perspectives in the context of their service delivery? (2) What is the nature of these differences, if any? and (3) Does program structure and context affect provider views?

Methods

Study 1

The first study, known as the New York Housing Study (NYHS), was a 4-year randomized controlled trial (1997–2002) funded by SAMHSA in which 99 individuals were assigned to the experimental PHF group (served by one agency) and 126 individuals were assigned to the control group (served by multiple agencies providing traditional services; for more information, see Tsemberis et al., 2004). Staff members at the PHF provider (n =37) and three control programs (n = 31) completed an anonymous questionnaire with three measures that compared overall values and approaches to service delivery. The first item, a values measure developed for this study, asked for responses to 22 statements about treatment of homeless individuals with psychiatric disorders or dual diagnoses, which were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). All questions not explicitly referring to sobriety featured two stems: “Homeless people with psychiatric disabilities...” and “Homeless people who are dually diagnosed with psychiatric disabilities and alcohol or drug use problems....” The measure included two subscales. The system values index (α = .88) featured 12 items such as “...require structure and supervision to put their lives in order” and “...need to be clean and sober for a period of time before they can live independently.” The consumer values index (α = .84) included 10 items such as “...who are living on the streets are able to move into apartments of their own” and “...have a right to refuse treatment.” This measure was also administered to 61 staff from additional programs who attended a meeting about city requirements at the Department of Homeless Services in New York and who were believed to reflect TF program philosophy because only one PHF program existed in New York City. This brought the total comparison sample for the values measures to 89.

The second measure, adapted from the Tolerance for Deviance items in the Multiphasic Environmental Assessment Procedure (MEAPS; α = .93; Moos & Lemke, 1983), asked staff to report on provider expectations for program participants. Staff rated 16 uncooperative or disruptive behaviors, such as refusing to take prescribed medicine, being drunk, stealing others’ belongings, and physically attacking another resident, on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = allowed (i.e., expected behavior, with no attempt made to change it) to 4 = intolerable (i.e., repeated offenses will probably result in removal from program).

Finally, staff responded to four vignettes describing consumers who had difficulties with mental health or substances. For example:

Ed, who is dually diagnosed, becomes very angry and threatening when he smokes crack. Staff and tenants have recently begun to complain that Ed is generally disrespectful and often verbally abusive to other tenants and staff members. He denies using or having any problems, but complaints about him have increased. There is some evidence he may be dealing to support his habit.

Staff members were asked how they would help the consumer in each vignette and whether the consumer could remain in housing (0 = yes, 1 = no). With only four dichotomous items, the index of four vignettes had an internal consistency of α = .40. With the exception of the consumer values scale, higher scores on staff measures indicated greater staff control and less tolerance for disruptive behaviors. Correlations among the four measures ranged in absolute value from .32 (MEAPS and vignettes) to .68 (consumer values and vignettes).

Study 2

The second study, known as the New York Services Study (NYSS), was a qualitative study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health from 2004 to 2008 that drew upon NYHS findings to formulate its questions and methods. This prospective study featured in-depth interviews with new PHF (n = 27) and TF (n = 56) enrollees at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months, as well as in-depth provider interviews (n = 21) (for more information, see Padgett, Stanhope, Henwood, & Stefancic, 2011). Despite the small provider sample, analyses found PHF providers to be predominantly White compared to higher percentages of African American and Latino providers in TF programs (p = .018). Although not statistically significant, there were higher percentages of graduate-level providers in the PHF program.

Semistructured interviews were conducted usually in a private office at the provider's agency. Interviews lasted approximately 30–45 minutes and included both general questions about work experience and client-specific questions, including a detailed description of recent client interactions. Questions included: What is working here like for you? What's your approach to working with clients who have serious mental illness along with substance use disorders? What are your expectations for [client] and do you think he/she will meet them? All interviews were transcribed verbatim and entered into ATLAS.ti software.

Analysis of Data

The NYHS values measure was factor analyzed and staff scores from all measures were compared using t-tests and χ2 analyses. It was expected that PHF providers would score higher on consumer values but lower on all other measures. Differences between PHF and TF providers on MEAPS items were examined post hoc.

To further test and contextualize these comparative findings, qualitative data from the NYSS were analyzed using thematic analysis (Boyatzis, 1998). This process included (1) generating codes for similar topics across transcripts; (2) revising codes into themes that fit data by identifying and comparing similar ideas across transcripts; and (3) determining the reliability of codes and themes by identifying positive and negative examples or qualifications. Codes related to NYHS findings were reviewed and analyzed to find both elucidating examples of PHF and TF program differences. Several strategies to maintain rigor were employed, including the use of independent and co-coded transcripts, refinement of themes using negative case examples, and memo-writing to help develop ideas and create a decisional audit trail (Padgett, 2008).

Results

Table 1 shows mean differences between staff of PHF and TF programs, as well as staff of comparable programs in New York City for the values measures, on measures of attitudes and values. PHF providers were far more likely to endorse consumer values (M = 4.3, nearly 2 standard deviations higher than TF staff and 1 standard deviation higher than staff from citywide programs). PHF staff overwhelmingly agreed that individuals with psychiatric disabilities or dual diagnoses have rights to independent housing and to refuse treatment, and that they would be better able to address other problems after attaining stable housing, whereas staff in TF programs, on average, neither agreed nor disagreed with these statements. Staff in TF and citywide programs were more likely to endorse systems values, such as the need for individuals with psychiatric disabilities or dual diagnoses to be stabilized in treatment, to develop independent living skills, and to be clean and sober before living independently in the community. PHF staff tended to disagree with these items, although not strongly. Post hoc tests showed significant differences between groups on all but two items. All providers agreed that individuals with dual diagnoses need clinical support to make wise life choices. Further, although PHF staff tended to disagree that individuals with dual diagnoses were unable to maintain independent housing without close supervision, whereas staff from other programs tended to agree, the difference was not significant at p < .05.

Table 1.

Staff Values and Approaches

| Measure | PHF (n = 37) M (SD) | TF (n = 31) M (SD) | Citywide (n = 61) M (SD) | Test F or t | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer values | 4.3 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.7) | 24.49** | 1–5 |

| System values | 2.8 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.7) | 3.7 (0.6) | 24.92** | 1–5 |

| MEAPS | 2.8 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.5) | NA | 3.91** | 1–4 |

| Vignettes | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.3) | NA | 3.26* | 0–1 |

Note. Higher scores indicate higher presence of given construct; for MEAPS, higher scores indicate policies that exclude deviant clients; for vignettes, higher scores indicate the client would have to leave housing. PHF staff differed from TF and citywide staff separately at p < .001 for both values measures with Bonferroni correction. MEAPS = Multiphasic Environmental Assessment Procedure; NA = not available; PHF = Pathways’ Housing First, TF = treatment first.

p < .01

p < .001

PHF providers also differed significantly from TF staff in terms of reluctance to exclude consumers who engaged in deviant behavior. PHF staff averaged a standard deviation lower in MEAPS ratings regarding intolerance for disruptive behaviors. Post hoc examination led to creation of two subscales: nine items ranging from minor (refusing to participate in programmed activities) to serious (attempting suicide) behaviors that largely affected the individual, and seven items (from creating a disturbance to physically attacking another resident) that affected others. PHF staff members were far more likely to allow or tolerate the first set of behaviors than TF staff, but the groups did not differ significantly regarding behaviors that affected other people. In response to the vignettes, TF providers were about three times more likely than PHF staff to say the consumer would have to leave housing. Post hoc analysis showed differences were more significant for scenarios that involved substance use than psychiatric problems.

Using these findings to narrow the scope of inquiry in the qualitative data set, thematic differences emerged between PHF and TF providers that confirmed and further elucidated differing perspectives (i.e., person-centered vs. system-centered and acceptance vs. conformity) that were influenced by program structure (see Table 2 for additional illustrative quotes).

Table 2.

Emergent themes and illustrative quotes

| Theme 1. Person-Centered versus System-Centered |

| 1a. HF provider: “I don't really have a set approach. It's sort of working within the relationship, first establishing the relationship, and that could take a while, trust-wise. And then being able to sort of use that relationship and approach somebody around whatever it is they want.” |

| 1b. HF provider: “The reason why I'm here [at the agency] is because we have a very strong Housing First mission where we believe that everyone has the right to have their own apartment and live independently whether or not they're taking meds or sober or what have you.” |

| 1c. HF provider: “Coming [here] changed my perspective on everything because I worked at a drug TC [therapeutic community] program before, where abstinence is definitely a must before they even try to get you housing.” |

| 1d. TF provider: “If you really look at this whole thing, the client is a commodity. And you are here to sell that client. That's the big picture. ... So, I'm a salesman, and that's the product, and that's the way I see it. I have to do whatever I can to sell the product [to potential housing providers].” |

| 1e. TF provider: “I take a very tough approach, tough approach in a loving way. I have my own set of rules. You know, the rules here are they're not allowed a cell phone, it's fine but they're not allowed to use it in the building. My thing is if I catch them in the building using it, I'll take your phone away for a day or two.” |

| Theme 2. Acceptance versus Conformity |

| 2a. HF provider: “Most programs are like that. ... If you were tested positive for drugs, you were kicked out, maybe given a second chance or if you didn't take your meds. I mean [our program] is very different that way. Most places are like that because they don't want to deal, they want people to just be medicated and off drugs. They don't want to deal with them on drugs, you know all paranoid. We're saying we'll take you as you are.” |

| 2b. HF provider: “We don't require medications, and it is very client-driven. ... I think some of the clients who are very psychotic and paranoid, we can't ... I think it's just hard sometimes to work with them. I struggle with that sometimes because I question what we are doing.” |

| 2c. TF provider: “I would basically tell them something like, if that's the case [consumer is using drugs], you need to decide where you're gonna live. Because I'm not gonna be able to get you housed unless you're psychiatrically stable. And if I'm not gonna be able to get you housed, you're not gonna stay here very long because I only have [a certain amount of] beds. ... And I tell all the clients if they're not serious, don't waste my time.” |

| 2d. TF provider: “We're not taking bets, but sometimes me and the case managers, we'll get together and the clients will come in, and we can look and say, you know what, the client ain't going to make it. You could just tell sometimes by the way they come in, their behavior.” |

Person-Centered versus System-Centered

Endorsing consumer values, more prevalent among PHF providers, was expressed in terms of providing individualized care: “Every situation, every individual is different.” PHF described the “Housing First mission” as honoring consumer preference, which served as a guiding framework. Although some providers clearly self-selected to work in a PHF environment, others adopted this consumer-driven approach after exposure to the model explaining that the work “changed my perspective on everything.”

This orientation was noticeably missing among providers in traditional programs, who seemed more focused on system-centered demands that was made clear by a provider who explained, “If you really look at this whole thing, the client is a commodity.” This was viewed as an inevitable result of program structure: “I see, on a daily basis, things being prioritized in a certain way because it comes down to numbers.” Nevertheless, providers often improvised with one person stating, “I have my own set of rules.” In TF programs, provider improvisation was performed to “make their numbers” and place people in housing.

Acceptance versus Conformity

The value-driven approach identified by PHF providers also resulted in increased acceptance of “deviant” behavior. One provider said acceptance stemmed from the program model stating “We're saying we'll take you as you are.” Accepting consumers was seen by PHF providers as necessary to working effectively and maintaining relationships with consumers, made possible by explicitly adopting a harm reduction model. In PHF, harm reduction “extends not just with drug use. It expands with working and a whole slew of things, relationships, and you can apply it to almost every service you provide.” Because harm reduction is adopted as a general framework, “If there are people who work here who don't necessarily buy into a harm reduction philosophy, which to me, you're swimming against the stream.” Nevertheless, some providers acknowledged an inner tension despite an overall context of accepting consumer choice particularly when consumers were not doing well.

Rather than acceptance, TF providers regarded deviant behavior as problematic. Conforming to a housing system that required abstinence made honoring consumer choice untenable for providers. “It's a sober facility, so we definitely establish those ground rules to begin with.” Working in TF programs also resulted in an inevitable (and accurate) sense that many consumers won't succeed. Although not universal, providers would usually attribute failure to engagement to substance use: “He wants to use ... and until he is committed to living his life sober, we can't help.” TF providers often framed their ability to help consumers as an all-or-nothing proposition based on a consumer's ability to conform to program expectations.

Discussion

These two studies revealed fundamental differences between providers in PHF and TF programs. PHF providers reported greater endorsement of consumer values, less endorsement of systems values, and greater tolerance for deviant behavior than TF providers. Greater tolerance for deviance among PHF staff was confined to behaviors that affected only the consumer; PHF staff were as likely as TF staff to intervene in behaviors that harmed others, and they expected consumers to adhere to the normal responsibilities of tenants and citizens. The qualitative findings confirmed and elucidated the nature of these differences that represent two distinct perspectives on working with consumers. In the PHF model, the notion of consumer-driven services was not simply jargon but accurately depicted the values, philosophy, and mission of staff to accept consumers’ ability to be self-directed, even when difficult. Conversely, providers in TF programs attempted to have consumers conform to system-centered goals, which at times appeared to overlook the individuals that the system was intended to serve (Allen, 2003), resulting in higher rates of disengagement from services (Stanhope, Henwood, & Padgett, 2009). Differences in how these two models structured services along with their underlying service philosophies directly influenced individual providers. The ability to house consumers while using harm reduction allowed PHF providers to deliver consumer-driven services. The TF model required providers to work towards conformity to system-defined criteria for housing that may be inconsistent with consumer goals. In both cases, frontline providers can and did improvise, yet TF providers were more limited in their ability to engage consumers who actively used drugs or attempted to manage symptoms without taking psychiatric medication. In many cases, this may have caused providers to chose to work in a PHF agency, yet the data suggested that exposure to the PHF model influenced provider perspectives. It should be noted that how variations in provider or client characteristics affected provider perspectives was not addressed and would have been limited by the small provider samples.

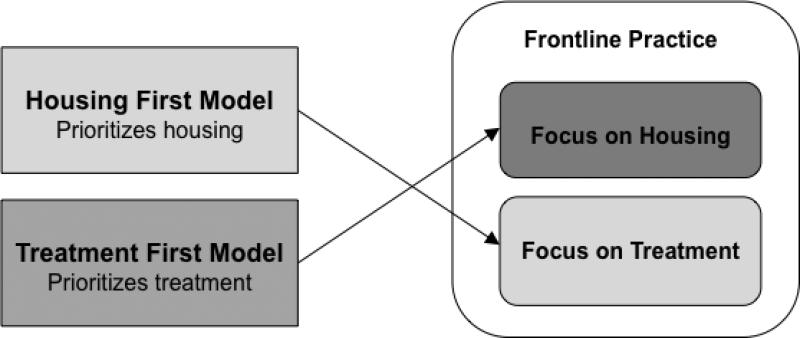

Comparing the views of frontline providers with their program's underlying service model revealed an ironic finding regarding program implementation (Henwood et al., 2011). Despite being recognized for prioritizing housing, PHF providers focused on consumer needs and made ongoing efforts to engage them in treatment and services. TF providers focused on gaining access to housing and were confined by the lack of fit between system expectations and consumer behavior. An “implementation paradox” occurred in the sense that TF providers were inhibited from engaging consumers in treatment and services due to a lack of housing, whereas PHF providers could focus on issues other than securing housing (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Implementation Paradox.

Much of the difference between programs and implementation was rooted in the PHF model's commitment to consumer choice. This commitment, transmitted in staff selection, socialization, and ongoing training, informed staff values and how staff responded to potentially disruptive behavior and consumer crises. PHF is not simply about getting homeless people with psychiatric disabilities off the streets quickly, but also about supporting their choices in housing, participation in treatment, and lifestyle.

Similarities among programs were also noteworthy. PHF staff was as likely as TF staff to say that individuals with dual diagnoses require clinical support to make wise choices. PHF does not feature housing only—it features delivery of comprehensive supportive services chosen by a consumer residing in independent housing. Further, PHF staff did not differ from control staff in discouraging or not tolerating disruptive behaviors such as assault that impinged on others. PHF tenants were held accountable for the same behaviors as other citizens.

Implications

PHF is a progressive program model whose philosophic premises, service structure, and empirical support have led to its increasingly widespread dissemination (Stanhope & Dunn, 2011). PHF program currently operate internationally, in several major U.S. cities, and in rural areas. Ongoing dissemination and implementation efforts are being aided by a published manual and fidelity scale (Tsemberis, 2010). Training a new providers to use this model raises several important questions, including how best to maintain a Housing First philosophy if the program exists within a more traditional agency, how providers habituated to TF services can be reoriented, and if increasing emphasis on recovery in mental health will diminish differing perspectives between PHF and other providers. This study also reinforces the need to understand and monitor how program models are implemented and their effects on front-line providers.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant 1UD9SM51970 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and grant R0169865 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

References

- Allen M. Waking Rip van Winkle: Why developments in the last 20 years should teach the mental health system not to use housing as a tool of coercion. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2003;21:503–521. doi: 10.1002/bsl.541. doi:10.1002/bsl.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanch AK, Carling PJ, Ridgway P. Normal housing with specialized supports: A psychiatric rehabilitation approach to living in the community. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1988;33:47–55. doi:10.1037/h0091686. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Felton BJ. Innovation and implementation in mental health services for homeless adults: A case study. Community Mental Health Journal. 2003;39:309–322. doi: 10.1023/a:1024020124397. doi:10.1023/A:1024020124397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood BF, Stanhope V, Padgett DK. The role of housing: A comparison of front-line provider views in Housing First and traditional programs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0303-2. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0303-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Lemke S. Assessing and improving social-ecological settings. In: Seidman E, editor. Handbook of social intervention. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1983. pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Newman SJ. Housing attributes and serious mental illness: Implications for research and practice. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1309–1317. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.10.1309. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.10.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK. Qualitative methods in social work research. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Gulcur L, Tsemberis S. Housing First services for people who are homeless with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance abuse. Research on Social Work Practice. 2006;16:74–83. doi:10.1177/1049731505282593. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Stanhope V, Henwood BF, Stefancic A. Substance use outcomes among homeless clients with serious mental illness: Comparing Housing First with treatment first programs. Community Mental Health Journal. 2011;47:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9283-7. doi:10.1007/s10597-009-9283-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C, Montgomery AE, Locke G. Housing stability among homeless individuals with serious mental illness participating in Housing First programs. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37:404–417. doi:10.1002/jcop.20303. [Google Scholar]

- Rog DJ. The evidence on supported housing. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2004;27:334–344. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.334.344. doi:10.2975/27.2004.334.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyers MP, Tsemberis S. ACT and recovery: Integrating evidence-based practice and recovery orientation on Assertive Community Treatment teams. Community Mental Health Journal. 2007;43:619–641. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9088-5. doi:10.1007/s10597-007-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope V, Dunn K. The curious case of Housing First: The limits of evidence based policy. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2011;34:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.07.006. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope V, Henwood BF, Padgett DK. Understanding service disengagement from the perspective of case managers. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:459–464. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.459. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Pathways’ Housing First program. 2007 Retrieved from National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices website: http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/ViewIntervention.aspx?id=155.

- Tsemberis S. Housing First: The Pathways model to end homelessness for people with mental illness and addiction manual. Hazelden; Center City, PA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing First, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:651–656. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.651. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]