Abstract

Whole-body cryotherapy (WBC) involves short exposures to air temperatures below −100°C. WBC is increasingly accessible to athletes, and is purported to enhance recovery after exercise and facilitate rehabilitation postinjury. Our objective was to review the efficacy and effectiveness of WBC using empirical evidence from controlled trials. We found ten relevant reports; the majority were based on small numbers of active athletes aged less than 35 years. Although WBC produces a large temperature gradient for tissue cooling, the relatively poor thermal conductivity of air prevents significant subcutaneous and core body cooling. There is weak evidence from controlled studies that WBC enhances antioxidant capacity and parasympathetic reactivation, and alters inflammatory pathways relevant to sports recovery. A series of small randomized studies found WBC offers improvements in subjective recovery and muscle soreness following metabolic or mechanical overload, but little benefit towards functional recovery. There is evidence from one study only that WBC may assist rehabilitation for adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. There were no adverse events associated with WBC; however, studies did not seem to undertake active surveillance of predefined adverse events. Until further research is available, athletes should remain cognizant that less expensive modes of cryotherapy, such as local ice-pack application or cold-water immersion, offer comparable physiological and clinical effects to WBC.

Keywords: whole-body cryotherapy, cooling, recovery, muscle damage, sport

Introduction

Cryotherapy is defined as body cooling for therapeutic purposes. In sports and exercise medicine, cryotherapy has traditionally been applied using ice packs or cold-water immersion (CWI) baths. Recently, whole-body cryotherapy (WBC) has become a popular mode of cryotherapy. This involves exposure to extremely cold dry air (usually between −100°C and −140°C) in an environmentally controlled room for short periods of time (typically between 2 and 5 minutes). During these exposures, individuals wear minimal clothing, gloves, a woolen headband covering the ears, a nose and mouth mask, and dry shoes and socks to reduce the risk of cold-related injury. Although it was originally developed to treat chronic medical conditions, such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis,1 WBC is being increasingly employed by athletes. Its purported effects include decreased tissue temperature, reduction in inflammation, analgesia, and enhanced recovery following exercise. WBC is typically initiated within the early stages (within 0–24 hours) after exercise and may be repeated several times in the same day or multiple times over a number of weeks.

WBC is becoming increasingly accessible for athletes. It is considerably more expensive than traditional forms of cryotherapy, but it is not clear whether it offers any additional clinical effect. A recent review by Banfi et al2 found observational evidence that WBC modifies many important biochemical and physiological parameters in human athletes. These include a decrease in proinflammatory cytokines, adaptive changes in antioxidant status, and positive effects on muscular enzymes associated with muscle damage (creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase). They also concluded that exposure to WBC is safe and does not deleteriously effect cardiac or immunological function. However, when this review2 was published, few randomized trials examining the efficacy of the treatment had been completed. Further, the conclusions were predominantly based on lower-quality observational studies, which did not include a control group and therefore should be treated with caution.

A common supposition is that the extreme nature of WBC offers significant advantages over traditional methods of cooling, such as CWI or ice-pack application. Recently, there has been a large increase in the volume of research investigating the effects of WBC. Our aim is to update the evidence base, with a particular focus on reviewing empirical evidence derived from controlled studies. The objectives were: 1) to quantify the tissue-temperature reductions associated with WBC and compare these with traditional forms of cryotherapy; 2) to examine the biochemical and physiological effects of WBC exposure compared to a control, and to determine any associated adverse effects; and 3) to consider the strength of the clinical evidence base supporting its use in sports recovery and soft-tissue injury management.

Materials and methods

A literature search was undertaken using Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register up to October 2013. For our first objective, we sourced any studies quantifying temperature reductions associated with WBC. We extracted data (mean ± standard deviation) on skin, intramuscular, and core-temperature reductions induced by WBC. No restrictions were made on the temperature-measurement device. For comparison, we used a convenience sample of studies reporting tissue-temperature reductions induced by ice-pack application (crushed ice) and CWI based on durations of 10 minutes and 5 minutes, respectively. These durations were selected as they align well with current clinical practice.3,4

For our second objective, we focused on studies fulfilling the following inclusion criteria: controlled studies comparing WBC intervention to a control group (observational studies and studies using within-subject designs were excluded); the temperature of exposure had to have been at least −100°C, though there were no restrictions placed on the number of exposures; participants could be healthy, or recovering from exercise or soft-tissue injury at the time of the intervention; no restrictions were made on participants’ age, sex, or training status. We extracted all data relating to biochemical, physiological, or performance/clinical outcomes.

Key study characteristics were extracted by the primary researcher and tabulated. Outcomes were subgrouped into biochemical, perceived sensation, and performance-based measures. We were particularly interested in between-group differences based on follow-up scores. Where possible, effect sizes (standardized mean differences [MDs] and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) were calculated from group means and standard deviations, using RevMan software (version 5.2; Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Characteristics of controlled studies

Key study characteristics5–14 are summarized in Table 1. Three studies8,10,13 used randomized controlled designs, with all incorporating high-quality methods based on computer-generated randomization, allocation concealment, and blinded outcome assessment. The remainder of the studies5–7,9,11,12,14 used controlled or crossover designs, with washout periods varying between 37 and 16 weeks.5

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study design | Participants | WBC (control) | Outcomes

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher values in WBC (vs control) | Lower values in WBC (vs control) | No between-group differences | |||

| Mila-Kierzenkowska et al5 Crossover study (4-month washout) |

n=9 Olympic-level kayakers undertaking a 10-day training cycle (all female, mean age 23.9±3.2 years) Cointerventions Antioxidant supplementation |

n=9 exposed to −120°C to −140°C for 3 minutes; 20 sessions in total: twice per day over a 10-day period (n=9 no WBC) | Catalase TBARS | Superoxide dismutase Glutathione peroxidase | |

| Hausswirth et al6 Randomized crossover study (3-week washout) |

n=9 well-trained runners undertaking a simulated 48-minute trail run (all male, mean age 31.8±6.5 years) | n=9 exposed to −110°C for 3 minutes; 3 sessions in total: immediately, 24, and 48 hours postexercise (n=9 seated rest) | Strength | Pain Tiredness | Creatine kinase |

| Pournot et al7 Randomized crossover study (3-week washout) |

n=11 trained runners undertaking a simulated 48-minute trail run (all male, mean age 31.8±6.5 years) | n=11 exposed to −110°C for 3 minutes; 4 sessions in total: immediately, 24, 48, and 72 hours postexercise (n=11 seated rest) |

IL-1ra | CRP | IL-1β IL-6 IL-10 TNFα Leukocyte count |

| Ziemann et al8 Randomized controlled trial |

n=12 professional male tennis players undertaking moderate-intensity training for 5 days (all male, mean age 20±2 years control, 23±3 years WBC) | n=6 exposed to −120°C for 3 minutes; 10 sessions in total: twice per day over 5 days (n=6 no WBC) | IL-6 Tennis-stroke effectiveness |

TNFα | Creatine kinase Leukocyte count Cortisol Testosterone |

| Miller et al9 Controlled trial |

n=94 healthy participants (46 male, 48 female, mean age 37.5±3.1 years WBC, 37.9±2.1 years control) | n=46 exposed to −130°C for 3 minutes; 10 sessions in total: 1 session per day over 10 days (n=48 no WBC) | Total antioxidant status Superoxide dismutase Uric acid TBARS |

||

| Costello et al10 Randomized controlled trial |

n=36 healthy participants (24 male, 12 female, mean age 20.8±1.2 years) | n=16 exposed to −110°C for 3 minutes; 2 sessions in a single day, 2 hours apart (n=16 exposed to 15°C) | Joint positional sensea MVIC | ||

| Costello et al10 Randomized controlled trial |

n=18 participants (4 female, 14 male, mean age 21.2±2.1 years) undertaking 100 high-force maximal eccentric contractions of the left knee extensors | n=9 exposed to −110°C for 3 minutes; 2 sessions in a single day, 2 hours apart (n=9 exposed to 15°C) | MVIC Pain Peak power output |

||

| Fonda and Sarabon11 Randomized crossover (10-week washout) |

n=11 participants (all male, mean age 26.9±3.8 years) undertaking high-load and eccentric lower-limb exercises | n=11 exposed to −140°C to −195°C for 3 minutes; 6 sessions in total: 1 per day over 6 days (n=11 no WBC) | Pain at rest Pain on squat |

Creatine kinase Lactate dehydrogenase Aspartate aminotransferase Performanceb |

|

| Hausswirth et al12 Controlled trial |

n=40 healthy participants (all male; mean age 33.9±12.3 years control, 34.6±11.5 years WBC, 33.3±13.8 years PBC) | n=15 exposed to −110°C WBC for 3 minutes; n=15 exposed to −160°C PBC for 3 minutes; (n=10 seated rest) | Norepinephrine Dopamine (WBC) Heart-rate variability | Epinephrine Dopamine (PBC) |

|

| Ma et al13 Randomized controlled trial |

n=30 participants with adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder joint (24 female, 6 male, mean age 57.2±6.6 years) | n=15 exposed to −110°C for 4 minutes; 24 sessions in total: 2 sessions per day, 3 times per week over 4 weeks plus standard physiotherapy treatment (n=15 standard physiotherapy treatment only) | ROM Function | Pain | |

| Schall et al14 Randomized crossover (1-week washout) |

n=11 participants (all female, mean age 20.3±1.8 years) undertaking a 3-minute-maximum swimming exercise bout | n=9 exposed to −110°C for 3 minutes; 1 session immediately after exercise (n=9 30 minutes of passive recovery) | Indices of heart-rate variability Metabolic recovery (lactate VO2 peak) Subjective recovery | Performance (subjective judging in synchronized swimming) | |

Notes:

Absolute, relative, and variable error

countermovement jump, power, strength.

Abbreviations: WBC, whole-body cryotherapy; vs, versus; TBARS, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; IL, interleukin; ra, receptor antagonist; CRP, C-reactive protein; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; MVIC, maximum voluntary isometric contraction; PBC, partial body cryotherapy; ROM, range of movement.

The majority of studies were undertaken using young, active participants with mean ages under 35 years. Just under 40% of participants were females. Four studies recruited high-performance athletes.5–8 In three studies,9,10,12 the objective was simply to examine the effect of WBC compared to an untreated control intervention using a sample of healthy participants. Six studies5–8,10,11 used WBC either in the early stages after exercise or intermittently throughout a particular training block. One study13 investigated the clinical effectiveness of WBC using a sample of participants with adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder joint.

In all studies, the WBC intervention involved a brief exposure to an acclimatization chamber or prechamber before entering a therapy chamber at −110°C to −195°C for 2.5–3 minutes. The total number of treatment sessions varied between one session on a single day12 up to 20–24 sessions over a period of weeks.5,13

Results

Tissue-temperature reductions

Table 2 shows the relative temperature reductions associated with typical applications of ice packs, CWI, and WBC.12,15–29 The largest skin-temperature reductions seemed to be associated with ice-pack application. The skin-temperature reductions associated with CWI and WBC seemed to vary slightly across studies. Two studies25,26 reported similar skin temperatures associated with a 4-minute WBC exposure at −110°C (thigh, 17.9°C±1.4°C; knee, 19.0°C±0.9°C) and a 4-minute CWI at 8°C (thigh, 21.3°C±1.2°C; knee, 20.5°C±0.6°C). Table 2 clearly highlights that subcutaneous tissue temperature reductions were consistently small regardless of the cooling medium. Intramuscular temperatures at 2 cm depth were rarely cooled below 2°C. Again, there were trends that ice packs induced slightly larger intramuscular temperature reductions in comparison to CWI and WBC. Core-temperature reductions were consistently small across all cooling modes.

Table 2.

Tissue-temperature reductions by cooling modalities

| Ice pack (10 minutes) | CWI (4–5 minutes, 8°C–10°C) | WBC (3 minutes) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin temperature | 18b,15 | 6.2 (0.5)24 | 3.5–8.727 |

| 20a,16 | 8.4 (0.7)25 | 6.7b,28 | |

| 20b,17 | 9.0 (0.8)26 | 8.1 (0.4)c,12 | |

| 2018 | 12.1 (1.0)25 | ||

| 22a,b,19 | 10.3 (0.6)26 | ||

| 25.7–26.420 | 13.7 (0.7)12 | ||

| 19.4b,29 | |||

| Intramuscular temperature (2 cm depth) | 1.76 (1.37)21 | 1.7 (0.9)25 | 1.2 (0.7)25 |

| 2.0a,16 | |||

| 2.0a,b,19 | |||

| 2.7b,15 | |||

| −3.88 (1.83)22 | |||

| Core temperature | 0a,16 | 0.2 (0.1)24 | 029 |

| 023 | 0.4 (0.2)25 | 0.3 (0.2)25 | |

Notes:

Data extracted from graphs with permission: Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2001;82, Jutte LS, Merrick MA, Ingersoll CD, Edwards JE. The relationship between intramuscular temperature, skin temperature, and adipose thickness during cryotherapy and rewarming. 845–850.16 © 2001 with permission from Elsevier; and Merrick MA, Jutte LS, Smith ME. Cold modalities with different thermodynamic properties produce different surface and intramuscular temperatures. J Athl Train. 2003;38:28–33.19

standard deviation not available.

PBC. All values are degrees celsius (means ± standard deviation).

Abbreviations: CWI, cold-water immersion; WBC, whole-body cryotherapy; PBC, partial body cryotherapy (head out).

Inflammatory biomarkers

Pournot et al7 compared a WBC intervention to a passive control after an intense simulated trail run using high-level athletes. Levels of inflammatory biomarkers (interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-1 receptor antagonist [ra], IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, and leukocytes) during the 4-day recovery period were generally similar in each group. The largest between-group differences were higher IL-1ra immediately after the first exposure, and lower concentration of C-reactive protein at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours postexercise within the WBC condition. In a small study, Ziemann et al8 randomized professional tennis players to undertake twice-daily WBC or no intervention during a 5-day training camp. Two of the participants in this study could not be randomized due to contraindications to WBC and were therefore preselected for the control intervention. Their results showed an enhanced cytokine profile within the WBC group, with lower levels of TNFα and a higher concentration of IL-6.

Muscle damage

There was evidence from three studies6,8,11 that WBC does not affect markers of muscle damage after exercise. These studies found few differences between WBC and control groups in creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, and aspartate aminotransferase during recovery from exercise-induced muscle damage (EIMD),11 intense running,6 or 5 days of moderate-intensity tennis training.8

Oxidative stress

Miller et al9 examined oxidative stress and antioxidant function using a group of nonexercising participants. The results showed an increase in antioxidant status associated with WBC in comparison to the untreated control group; however, there were only small between-group differences in relation to lipid peroxidation. As oxidative stress and antioxidant function were quantified at two different sites (ie, vascular and intracellular), it is difficult to conclude a strong relationship between WBC and free radical production. In a crossover study, Mila-Kierzenkowska et al5 examined antioxidant status in Olympic kayakers undertaking training cycles both with and without WBC stimulation (twice per day). Results showed an attenuation of oxidative stress as measured by lipid peroxidation in the WBC group over the course of a 10-day training bout. This finding did not align with the majority of the athletes’ enzymatic profiles (super-oxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase), which were also surprisingly lower in the WBC condition in comparison to the exercise-only condition.

Autonomic nervous system

Hausswirth et al12 reported significant increases in nor-epinephrine concentrations in the immediate stages after cryostimulation compared to resting controls. They found similar between-group differences in resting vagal-related heart-rate variability indices (the root-mean-square difference of successive normal R–R intervals, and high-frequency band). An interesting caveat was that the magnitude of these effects was reduced when participants substituted WBC for a partial body cryostimulation that did not involve head cooling. Another randomized study12 examined the effects that WBC has on autonomic function, with a primary focus on parasympathetic reactivation after two maximal synchronized swimming bouts. Comparisons were made against active, passive, and contrast water-therapy conditions. The WBC condition (3 minutes at −110°C) had the largest influence on parasympathetic reactivation, with large increases across a range of similar heart-rate variability indices.

Perceived and functional recovery

Using a randomized controlled design, Costello et al10 found that 3-minute exposures at −110°C had little effect on joint positional sense and muscle function compared to control exposures at 15°C. A follow-up study within the same report10 examined the effectiveness of WBC compared to resting control using a subgroup of participants exposed to EIMD: results showed few differences between groups in terms of participants’ strength, power, and muscle soreness. Fonda and Sarabon11 also investigated the effects of WBC on functional recovery after EIMD, but incorporated a more intense cooling dose based on temperatures of −195°C, using a liquid nitrogen system, and treatment up to 6 days postexercise. These investigators also found few significant differences between groups in relation to strength and power output; however, they reported significantly lower muscle soreness in favor of WBC. It is important to consider that Costello et al10 incorporated a randomized controlled design, allocation concealment, and blinded outcome assessor, and was less open to selection and reporting bias.

Two studies investigated the effects of WBC on functional recovery after running- or sporting-based activities. Hausswirth et al6 found that undertaking WBC immediately and at 24 and 48 hours after intense trail running resulted in significant improvements in strength, pain, and subjective fatigue compared to untreated controls. Ziemann et al8 also recorded improved functional recovery associated with WBC within a group of elite tennis players. They found that athletes incorporating twice-daily exposure to −120°C during a 5-day training camp had greater shot accuracy during two testing sessions, compared to an untreated control. These findings may be subject to detection bias, as blinded outcome assessors were not employed.

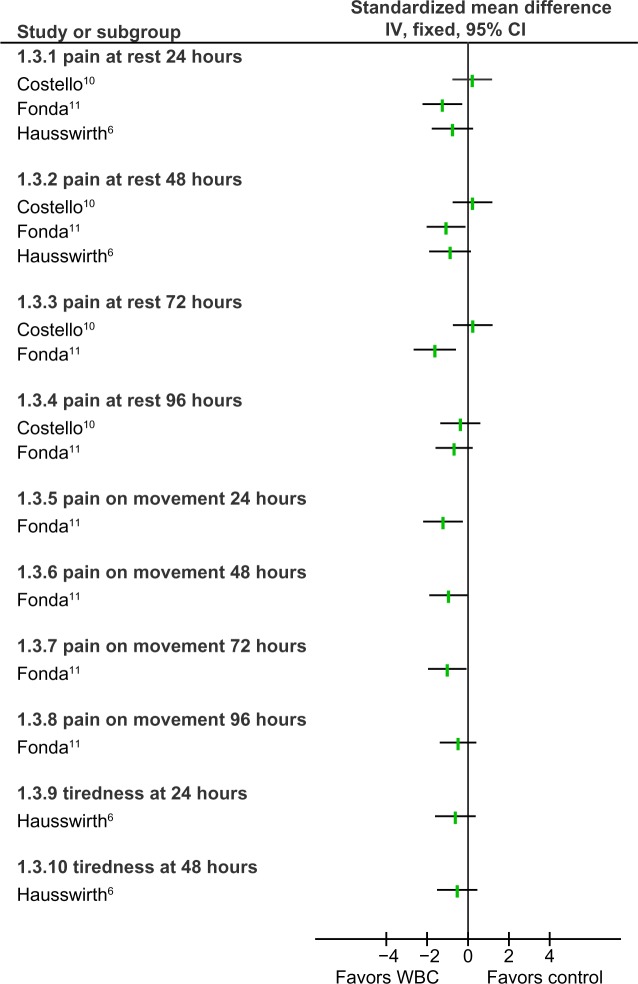

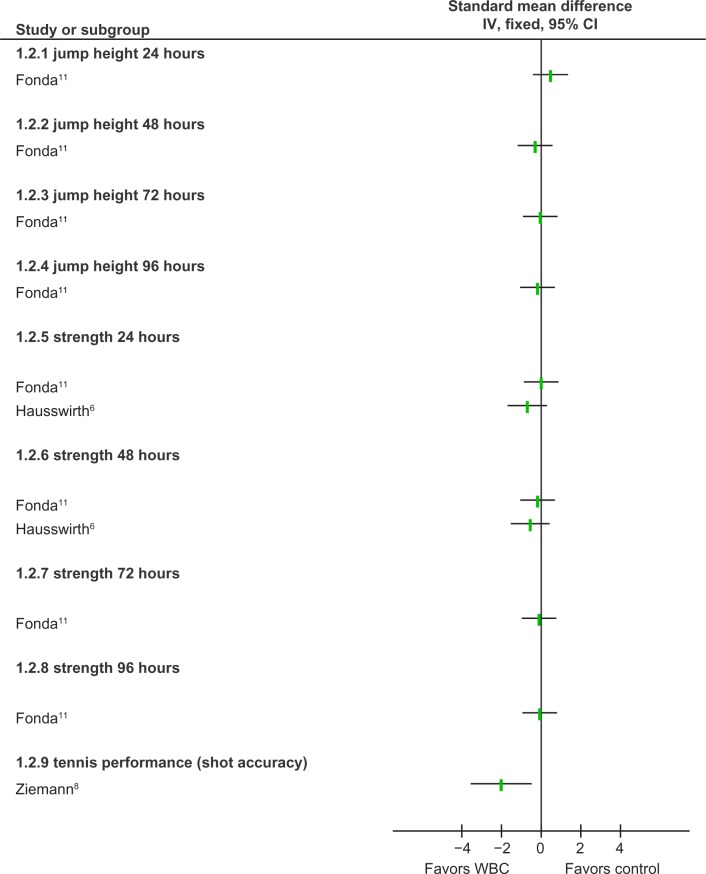

Schaal et al14 found that compared to a passive control, a single WBC exposure (3 minutes at −110°C) enhanced subjective and metabolic recovery (based on blood lactate and VO2max) after intense bouts of swimming. This study found few differences when comparisons were made to an active recovery condition. Figures 1 and 2 provide a summary of the effects of WBC on perceived and functional recovery after exercise when compared to control intervention.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of perceived sensation.

Abbreviations: IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval; WBC, whole-body cryotherapy.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of performance outcomes.

Abbreviations: IV, inverse variance CI, confidence interval; WBC, whole-body cryotherapy.

Clinical outcomes

One study13 examined the effectiveness of WBC on recovery from a musculoskeletal injury. Participants with adhesive capsulitis were randomized to receive either physiotherapy alone or physiotherapy in addition to WBC. After 4 weeks of treatment, both groups improved in terms of pain, shoulder function, and range of movement (ROM). Between-group comparisons were significantly in favor of WBC for all outcomes; in most cases, these were clinically meaningful with large mean differences in ROM (MD 13° abduction, 95% CI 9.2°–16.8°; MD 5° external rotation, 95% CI 3.2°–6.7°), pain (MD, 1.2 cm, 95% CI 0.8–1.6, based on a 10 cm visual analog scale), and shoulder function (MD 4 points, 95% CI 3.1–4.9, based on a 30-point scale). Of note, this study13 did not continue outcome assessment beyond the 4 weeks of treatment; therefore, any long-term effectiveness is unclear.

Discussion

This review examined the biochemical, physiological, and clinical effects of WBC. We found that most of the research in this area has been undertaken using small groups of younger (predominantly male) participants. In over half of the studies, the primary objective was to determine mechanisms of effect associated with WBC based on biochemical markers. A small number of studies focused on perceived recovery and performance-based measurement after various sport and exercise exposures. Only one study investigated the clinical effectiveness of WBC based on participants with significant musculoskeletal injury.

Tissue-temperature reduction

The premise of cryotherapy is to extract heat from the body tissue to attain various clinical effects. To optimize these effects, the best evidence suggests that a critical level of tissue cooling must be achieved.30,31 As such, a key objective of this review was to determine the magnitude of tissue-temperature reductions associated with WBC and to compare with traditional forms of cooling (ice pack, CWI) used in sport and exercise medicine.

There is a supposition that because of its extreme temperatures (–110°C), WBC offers an enhanced cooling effect over traditional forms of cryotherapy. It is clear that exposure to −110°C creates a large thermal gradient between the skin and the environment (~140°C). However, heat transfer depends on a number of additional factors. For example, thermal conductivity or heat-transfer coefficient (k = W/m2 − K) is the ability of a material to transfer heat. Ice has a much higher heat-transfer coefficient (2.18 k) compared to both water (0.58 k) and air (0.024 k), meaning that it is a more efficient material for extracting heat energy from the body. Ice application also exploits phase change (change from solid into liquid), further enhancing its cooling potential. Although water and air are not the best media to transfer heat, a potential advantage is that they facilitate large surface areas of the body to be cooled simultaneously.

Comparisons across empirical studies suggest that the largest skin-temperature reductions are usually associated with crushed-ice application. Temperature reductions associated with CWI and WBC seem less intense, and in some reports these did not reach the critical temperatures necessary to optimize analgesia.30 Of note, intramuscular temperature reductions seem to be negligible, regardless of the mode of cooling. To date, only one study25 has examined the effect of WBC on intramuscular temperature, and future research addressing this gap in the literature is warranted.

The thermal properties of biological tissue mean that it is fundamentally difficult to cool below the skin surface. Subcutaneous adipose tissue has a very low thermal conductivity (0.23 k; by comparison, muscle has a value of 0.46 k),32 causing it to have an insulating effect on the body. To our knowledge, the largest intramuscular temperature reduction (1 cm depth) reported in the clinical literature is 7°C33; interestingly, this was observed with an 8-minute ice-pack application in a sample of healthy participants with very low levels of adipose tissue (0–10 mm skin folds at the site of application). We have also recently demonstrated34 that the magnitude of temperature reduction also varies by body part, with bony regions such as the patella generally experiencing the largest reductions in tissue temperature.

Adverse events

We found no evidence of adverse effects within the current review. However, in accordance with previous reviews in this area,4,35 the majority of included studies did not seem to undertake active surveillance of predefined adverse events. Westerlund36 noted that no adverse effects had occurred during 8 years of WBC use within a specialist hospital in Finland. In recent years, a small number of isolated problems associated with WBC (eg, skin burns on the foot) have been publicized within the media; these events have been attributed to oversights during preparation, such as entering the chamber with wet skin or clothing. The skin surface has been reported to freeze from −3.7°C to −4.8°C,37 with serious cellular damage and cryotherapy skin burns occurring at a threshold of around −10°C.38 As few studies have reported skin-temperature reductions beyond 15°C with WBC, excessive tissue-temperature reductions seem unlikely, provided adequate procedures for patient preparation are followed, and relevant contraindications are adhered to: uncontrolled hypertension, serious coronary disease, arrhythmia, circulatory disorders, Raynaud’s phenomenon (white fingers), cold allergies, serious pulmonary disease, or the obstruction of the bronchus caused by the cold.36

Biomarkers

There is evidence from animal models to suggest that cryotherapy can have a consistent effect on some important cellular and physiological events associated with inflammation after injury. These include cell metabolism, white blood cell activity within the vasculature, and potentially apoptosis.39–44 Few studies have replicated these effects within human models. We highlighted two studies reporting an enhanced cytokine profile in athletes who used WBC after single7 or multiple training exposures.8 This should be regarded as preliminary evidence based on methodological limitations, including pseudorandomization and a risk of multiplicity. Others6,8,11 found little effect of WBC on various markers of muscle damage after various forms of exercise training. Evidence from recent reviews suggests that CWI3 and contrast water immersion35 have little to no effect on markers of inflammation or muscle damage after exercise. To our knowledge, only one study has quantified the biochemical effects of local ice-pack application within human subjects with significant injury. Using the microdialysis technique, Stålman et al45 reported that local icing and compression post-knee surgery resulted in a significantly lower production of prostaglandin E2 and synovial lactate compared to an untreated control group.

Oxidative stress

There is evidence that CWI can induce oxidative stress and a possible increase in free radical species formation.46 Free radicals are produced both as a by-product of cellular metabolism in aerobic systems and from various environmental sources. When free radical production exceeds antioxidant protection capacity and repair mechanisms, oxidative stress occurs, resulting in damage to such macromolecules as proteins, lipids, and deoxyribonucleic acid. The relative risk of oxidative stress appears to increase during periods of metabolic stress, where there is a disruption to the prooxidant/antioxidant equilibrium. A related concept is that brief repeated exposure to cold temperatures can benefit athletes by activating adaptive homeostatic mechanisms in accordance with the hormetic dose–response model.5 Indeed, others have reported improvements in antioxidant capacity associated with regular exposure to cold-water swimming.46

Evidence from controlled studies on the effect of WBC on antioxidant capacity is equivocal. One study5 reported a lower production of oxidative stress when intense exercise was undertaken in conjunction with WBC, compared to exercise alone. Surprisingly, these findings did not fully align with the athlete’s antioxidant profiles, as the WBC group had a lower concentration of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase over the 10-day training period. Although Miller et al9 found clearer evidence that WBC increases antioxidant activity in the absence of exercise, a limitation was that oxidative stress and antioxidant function were not quantified at the same site, and as such this makes it difficult to determine the mechanisms associated with oxidative stress. Furthermore, both these studies5,9 quantified oxidative stress using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay, which has a number of limitations.47 For example, the TBARS assay claims to quantify the amount of malondialdehyde formed during the lipid-peroxidation process; a primary problem is that other substances such as biliverdin, glucose ribose, and 2-amino-pyrimidines all have the ability to be absorbed at or close to the same spectroscopic wavelength as TBARS (532 nm), and as such the assay generally reports inaccurate malondialdehyde concentrations when compared with more sophisticated techniques. Future studies should focus on the specific cell-signaling events leading to the increase in antioxidant protein expression and incorporate at least two or more indices of oxidative stress to confirm cell damage. In addition, direct measures of free radical production, such as electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, would allow for a more accurate quantification of free radical generation and oxidative damage.

Autonomic nervous system

Finding efficient ways to influence the autonomic nervous system is a growing field in sports recovery. Intense exercise typically results in an increase in sympathetic activity, resulting in increased heart rate and decreased heart-rate variability. However, prolonged sympathetic activity is thought to be detrimental for postexercise recovery. As such, parasympathetic reactivation is currently considered to be an important indicator of systemic recovery, and often quantified using various indices of heart-rate variability.48

A small number of controlled studies have investigated the potential for using WBC to facilitate parasympathetic reactivation after exercise. Although there is evidence that WBC has an initial sympathetic effect,12 its summative effect seems to be parasympathetic. Indeed, Schaal et al14 reported that WBC enhances short-term autonomic recovery after intense exercise based on a two- to threefold increase in heart-rate variability. This response is thought to be mediated by the baroreflex, which is triggered by cold-induced vasoconstriction and an increase in central blood volume.49 As such, parasympathetic reactivation is not exclusive to WBC, and others50–52 have replicated these autonomic effects through CWI.

Clinical outcomes

We found conflicting evidence for the effect of WBC on correlates of functional recovery following sport. There was however clearer evidence that WBC could improve subjective outcomes, such as perceived recovery and muscle soreness. This aligns with findings from a recent Cochrane review4 concluding that CWI has little effect on recovery postinjury beyond reductions in muscle soreness. Similarly, although there is consistent evidence to show that cold packs and/or crushed ice provides effective short-term analgesia after acute soft-tissue injury and postsurgery,53–55 there is little evidence to show any effect on functional restoration or swelling.

For the current review, we found one study13 concluding that WBC has a clinically important effect on recovery from musculoskeletal injury (adhesive capsulitis). The underpinning mechanisms for these effects are difficult to determine. Perhaps an important consideration is that this study13 used WBC in conjunction with standardized physiotherapy intervention involving manual therapy and joint mobilization. It is possible that WBC produced a local analgesia, or acted as a counterirritant to pain, which facilitated mobilization. Optimal analgesia is associated with skin temperatures of less than 13°C,30 a threshold that has been attained using standard WBC exposures in some reports.12,36 We also know that WBC increases norepinephrine,2 which could have an additional analgesic effect.56 Local cooling can have an additional excitatory effect on muscle activation; this has been observed in both healthy and injured adults,57–60 providing further evidence that cooling can be an important adjunct to therapeutic exercise.

Benefits, harms, and recommendations for future research

When assessing therapeutic interventions, it is important to compare any benefits with possible risks and harms. In accordance with previous reviews,2 we found that WBC can modify many important biochemical and physiological parameters in human athletes. We also found trends that WBC can improve subjective recovery and muscle soreness following metabolic or mechanical overload. This evidence should still be regarded as preliminary, and further high-quality randomized studies are recommended.

It is difficult to reach a definitive conclusion on possible risks associated with WBC, as studies have not undertaken active surveillance of predefined adverse events. This should be addressed within future studies; the constant pressure to maximize sporting performance means that athletes often experiment with extreme exposures and interventions. Current recommendations for WBC parameters, including optimal air temperatures and the duration and frequency of exposure, are largely based on anecdote. It is imperative that safe guidelines are developed using evidence-based information. Future studies should also determine whether it is necessary to alter the dose of therapy based on the nature of the injury, the severity, or the level of chronicity.

WBC is often regarded as a superior mode of cooling, due to its extreme temperatures. However, there is no strong evidence that it offers any distinct advantages over traditional methods of cryotherapy. There is much evidence to show that CWI and ice-pack application are both capable of inducing clinically relevant reductions in tissue temperature, and that they also provide important physiological and clinical effects.3,4,30,46,50,55 Future research should directly compare the relative effectiveness of WBC, CWI, and ice-pack application. An important limitation is that WBC is currently significantly more expensive and much less accessible than either CWI or ice packs.

Conclusion

WBC induces tissue-temperature reductions that are comparable to or less significant than traditional forms of cryotherapy. Controlled studies suggest that WBC could have a positive influence on inflammatory mediators, antioxidant capacity, and autonomic function during sporting recovery; however, these findings are preliminary. Although there is some evidence that WBC improves the perception of recovery and soreness after various sports and exercise, this does not seem to translate into enhanced functional recovery. Only one study has focused on recovery after significant musculoskeletal injury, and long-term implications are unclear. Until further research is available, athletes should remain cognizant that less expensive modes of cryotherapy, such as local ice-pack application or CWI, offer comparable physiological and clinical effects to WBC.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work

References

- 1.Hirvonen HE, Mikkelsson MK, Kautiainen H, Pohjolainen TH, Leirisalo-Repo M. Effectiveness of different cryotherapies on pain and disease activity in active rheumatoid arthritis. A randomised single blinded controlled trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24:295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banfi G, Lombardi G, Colombini A, Melegati G. Whole-body cryotherapy in athletes. Sports Med. 2010;40:509–517. doi: 10.2165/11531940-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleakley CM, Glasgow PD, Philips P, et al. Guidelines on the Management of Acute Soft Tissue Injury Using Protection Rest Ice Compression and Elevation. London: ACPSM; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleakley C, McDonough S, Gardner E, Baxter GD, Hopkins JT, Davison GW. Cold-water immersion (cryotherapy) for preventing and treating muscle soreness after exercise. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD008262. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008262.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mila-Kierzenkowska C, WoŸniak A, WoŸniak B, et al. Whole body cryostimulation in kayaker women: a study of the effect of cryogenic temperatures on oxidative stress after the exercise. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2009;49:201–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hausswirth C, Louis J, Bieuzen F, et al. Effects of whole-body cryotherapy vs far-infrared vs passive modalities on recovery from exercise-induced muscle damage in highly-trained runners. PloS One. 2011;6:e27749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pournot H, Bieuzen F, Louis J, Fillard JR, Barbiche E, Hausswirth C. Time course of changes in inflammatory response after whole-body cryotherapy multi exposures following severe exercise. PloS One. 2011;6:e22748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziemann E, Olek RA, Kujach S, et al. Five-day whole-body cryostimulation, blood inflammatory markers, and performance in high-ranking professional tennis players. J Athl Train. 2012;47:664–672. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.6.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller E, Markiewicz L, Saluk J, Majsterek I. Effect of short-term cryostimulation on antioxidative status and its clinical applications in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:1645–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2122-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costello JT, Algar LA, Donnelly AE. Effects of whole body cryotherapy (−110°C) on proprioception and indices of muscle damage. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22:190–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fonda B, Sarabon N. Effects of whole-body cryotherapy on recovery after hamstring damaging exercise: a crossover study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23:e270–e278. doi: 10.1111/sms.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hausswirth C, Schaal K, Le Meur Y, et al. Parasympathetic activity and blood catecholamine responses following a single partial-body cryostimulation and a whole-body cryostimulation. PLoS One. 2013;22:e72658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma SY, Je HD, Jeong JH, Kim HY, Kim HD. Effects of whole-body cryotherapy in the management of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaal K, Le Meur Y, Bieuzen F, et al. Effect of recovery mode on postexercise vagal reactivation in elite synchronized swimmers. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38:126–133. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomchuk D, Rubley MD, Holcomb WR, Guadagnoli M, Tarno JM. The magnitude of tissue cooling during cryotherapy with varied types of compression. J Athl Train. 2010;45:230–237. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jutte LS, Merrick MA, Ingersoll CD, Edwards JE. The relationship between intramuscular temperature, skin temperature, and adipose thickness during cryotherapy and rewarming. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:845–850. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.23195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chesterton LS, Foster NE, Ross L. Skin temperature response to cryotherapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:543–549. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.30926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanlayanaphotporn R, Janwantanakul P. Comparison of skin surface temperature during the application of various cryotherapy modalities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1411–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merrick MA, Jutte LS, Smith ME. Cold modalities with different thermodynamic properties produce different surface and intramuscular temperatures. J Athl Train. 2003;38:28–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer JE, Knight KL. Ankle and thigh skin surface temperature changes with repeated ice pack application. J Athl Train. 1996;31:319–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zemke JE, Andersen JC, Guion WK, McMillan J, Joyner AB. Intramuscular temperature responses in the human leg to two forms of cryotherapy: ice massage and ice bag. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27:301–307. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.27.4.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myrer JW, Measom G, Durrant E, Fellingham GW. Cold and hot pack contrast therapy: subcutaneous and intramuscular temperature change. J Athl Train. 1997;32:238–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmieri RM, Garrison JC, Leonard JL, Edwards JE, Weltman A, Ingersoll CD. Peripheral ankle cooling and core body temperature. J Athl Train. 2006;41:185–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregson W, Black MA, Jones H, et al. Influence of cold water immersion on limb and cutaneous blood flow at rest. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1316–1323. doi: 10.1177/0363546510395497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costello JT, Culligan K, Selfe J, Donnelly AE. Muscle, skin and core temperature after −110°C cold air and 8°C water treatment. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costello JT, Donnelly AE, Karki A, Selfe J. Effects of whole body cryotherapy and cold water immersion on knee skin temperature. Int J Sports Med. 2013 Jun 18; doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1343410. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cholewka A, Stanek A, Sieroń A, Drzazga Z. Thermography study of skin response due to whole-body cryotherapy. Skin Res Technol. 2012;18:180–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2011.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cholewka A, Drzazga Z, Sieroń A, Stanek A. Thermovision diagnostics in chosen spine diseases treated by whole body cryotherapy. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2010;102:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westerlund T, Oksa J, Smolander J, Mikkelsson M. Thermal responses during and after whole-body cryotherapy. J Therm Biol. 2003;28:601–608. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bleakley CM, Hopkins JT. Is it possible to achieve optimal levels of tissue cooling in cryotherapy? Phys Ther Rev. 2010;15:344–350. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bleakley CM, Glasgow P, Webb MJ. Cooling an acute muscle injury: can basic scientific theory translate into the clinical setting? Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:296–298. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2011.086116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Brawany MA, Nassiri DK, Terhaar G, Shaw A, Rivens I, Lozhken K. Measurement of thermal and ultrasonic properties of some biological tissues. J Med Eng Technol. 2009;33:249–256. doi: 10.1080/03091900802451265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otte JW, Merrick MA, Ingersoll CD, Cordova ML. Subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness alters cooling time during cryotherapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1501–1505. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.34833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costello J, McInerney CD, Bleakley CM, Selfe J, Donnelly A. The use of thermal imaging in assessing skin temperature following cryotherapy: a review. J Therm Biol. 2012;37:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bieuzen F, Bleakley CM, Costello JT. Contrast water therapy and exercise induced muscle damage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westerlund T. Thermal, Circulatory, and Neuromuscular Responses to Whole-Body Cryotherapy [doctoral thesis] Oulu, Finland: University of Oulu; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danielsson U. Windchill and the risk of tissue freezing. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1996;81:2666–2673. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gage AA. What temperature is lethal for cells? J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1979;5:459–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1979.tb00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farry PJ, Prentice NG, Hunter AC, Wakelin CA. Ice treatment of injured ligaments: an experimental model. N Z Med J. 1980;91:12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurme T, Rantanen J, Kalimo H. Effects of early cryotherapy in experimental skeletal muscle injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1993;3:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Westermann S, Vollmar B, Thorlacius H, Menger MD. Surface cooling inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced microvascular perfusion failure, leukocyte adhesion, and apoptosis in the striated muscle. Surgery. 1999;126:881–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee H, Natsui H, Akimoto T, Yanagi K, Ohshima N, Kono I. Effects of cryotherapy after contusion using real-time intravital microscopy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:1093–1098. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000169611.21671.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaser KD, Stover JF, Melcher I, et al. Local cooling restores micro-circulatory hemodynamics after closed soft-tissue trauma in rats. J Trauma. 2006;61:642–649. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000174922.08781.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaser KD, Disch AC, Stover JF, Lauffer A, Bail HJ, Mittlmeier T. Prolonged superficial local cryotherapy attenuates microcirculatory impairment, regional inflammation, and muscle necrosis after closed soft tissue injury in rats. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:93–102. doi: 10.1177/0363546506294569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stålman A, Tsai JA, Wredmark T, Dungner E, Arner P, Felländer-Tsai L. Local inflammatory and metabolic response in the knee synovium after arthroscopy or arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bleakley CM, Davison GW. What is the biochemical and physiological rationale for using cold-water immersion in sports recovery? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:179–187. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.065565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powers SK, Smuder AJ, Kavazis AN, Hudson MB. Experimental guidelines for studies designed to investigate the impact of antioxidant supplementation on exercise performance. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2010;20:2–14. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.20.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seiler S, Haugen O, Kuffel E. Autonomic recovery after exercise in trained athletes: intensity and duration effects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1366–1373. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318060f17d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pump B, Shiraishi M, Gabrielsen A, Bie P, Christensen NJ, Norsk P. Cardiovascular effects of static carotid baroreceptor stimulation during water immersion in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circul Physiol. 2001;280:H2607–H2615. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buchheit M, Peiffer JJ, Abbiss CR, Laursen PB. Effect of cold water immersion on postexercise parasympathetic reactivation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H421–H427. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01017.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al Haddad H, Laursen PB, Ahmaidi S, Buchheit M. Influence of cold water face immersion on post-exercise parasympathetic reactivation. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:599–606. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stanley J, Buchheit M, Peake JM. The effect of post-exercise hydrotherapy on subsequent exercise performance and heart rate variability. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;2:951–961. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Airaksinen OV, Kyrklund N, Latvala K, Kouri JP, Grönblad M, Kolari P. Efficacy of cold gel for soft tissue injuries: a prospective randomized double-blinded trial. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:680–684. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310050801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bleakley CM, McDonough SM, MacAuley DC. Cryotherapy for acute ankle sprains: a randomised controlled study of two different icing protocols. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:700–705. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.025932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bleakley C, McDonough S, MacAuley D. The use of ice in the treatment of acute soft-tissue injury: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:251–261. doi: 10.1177/0363546503260757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pertovaara A, Kalmari J. Comparison of the visceral antinociceptive effects of spinally administered MPV-2426 (fadolmidine) and clonidine in the rat. Anesthesiology. 2003;92:189–194. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200301000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rice D, McNair PJ, Dalbeth N. Effects of cryotherapy on arthrogenic muscle inhibition using an experimental model of knee swelling. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:78–83. doi: 10.1002/art.24168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hopkins JT, Hunter I, McLoda T. Effects of ankle joint cooling peroneal short latency response. J Sports Sci Med. 2006;5:333–339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hopkins J, Ingersoll CD, Edwards J, Klootwyk TE. Cryotherapy transcutaneous electric neuromuscular stimulation decrease arthrogenic muscle inhibition of the vastus medialis after knee joint effusion. Train. 2002;37:25–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hopkins JT. Knee joint effusion and cryotherapy alter lower chain kinetics and muscle activity. J Athl Train. 2006;41:177–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]