Abstract

Background/Aims

The purpose of this study was to investigate the expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), uPA receptor (uPAR), and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 on podocytes in immunoglobulin A (IgA) glomerulonephritis (GN).

Methods

Renal biopsy specimens from 52 IgA GN patients were deparaffinized and subjected to immunohistochemical staining for uPA, PAI-1, and uPAR. The biopsies were classified into three groups according to the expression of uPA and uPAR on podocytes: uPA, uPAR, and a negative group. The prevalences of the variables of the Oxford classification for IgA GN were compared among the groups.

Results

On podocytes, uPA was positive in 11 cases and uPAR was positive in 38 cases; by contrast, PAI-1 was negative in all cases. Expression of both uPA and uPAR on podocytes was less frequently accompanied by tubulointerstitial fibrosis.

Conclusions

Our results suggest a possible protective effect of podocyte uPA/uPAR expression against interstitial fibrosis.

Keywords: Glomerulonephritis, IGA; Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; Urokinase-type plasminogen activator; Receptors, urokinase plasminogen activator

INTRODUCTION

The conversion of plasminogen to plasmin is known to be a key event in many physiological and pathological processes requiring regulated extracellular proteolysis [1,2]. Evidence that urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)-mediated plasminogen activation plays a significant role in cell surface proteolysis has emerged as a strong foundation for the demonstration of a specific cellular receptor for uPA on monocytes [3], many types of cultured cells [4], and various cancer cells [5].

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) is a serine protease whose primary physiological role is regulation of uPA and tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA). However, PAI-1 possesses various other functions in addition to its role in thrombosis and/or fibrinolysis [2].

The kidney is a unique organ, producing a large amount of uPA. However, the physiological role of uPA in the kidney has not been defined. During the last several years, the possible roles of uPA in the development of glomerulopathy have emerged, specifically in the development of albuminuria [6] and mesangial cell survival/apoptosis [7] and the inflammation-fibrosis process in glomeruli [8]. Lorenzen et al. [9] reported that the treatment of podocytes with osteopontin increases uPA and matrix metalloproteinase expression, increasing podocyte motility, and causing albuminuria. In addition, many investigators have proposed that renal uPA receptor (uPAR) attenuates the fibrogenic response to renal injury [10-12], suggesting that uPA/uPAR is an essential element with a decisive effect on the pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis (GN). However, most of these previous reports are based on in vitro or animal experiments. Therefore, the role of uPA in the progression of chronic glomerulonephritis is unclear in humans because of a lack of clinical evidence.

This study was designed to evaluate the association of uPA/uPAR/PAI-1 expression with glomerular pathology in immunoglobulin A (IgA) GN.

METHODS

Fifty-two renal biopsy specimens of IgA GN were obtained from a study population comprising 22 females and 30 males with an age distribution of 14 to 78 years (mean age, 35.3 years). All of the renal biopsies were performed in the Department of Pathology at Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital between May 2010 and October 2011. Pathology slides were prepared from the stored paraffin-embedded specimens and reviewed in each case to confirm the original diagnosis of IgA GN. Clinical information such as age, sex, antihypertensive medication, and laboratory data was obtained from the medical records.

Immunohistochemical staining for uPA, PAI-1, and uPAR was performed. Tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and heated in 0.1 M citrate buffer in a microwave for 20 minutes. After washing with distilled water, sections were treated with proteinase K (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) at room temperature for 10 minutes. Immunochemistry was performed in an autoimmunostainer (Bond Polymer Refine Kit, Leica, Bannockburn, IL, USA) by using a rabbit polyclonal uPA antibody (NBP1-19735) and a PAI-1 antibody (NBP1-19773) (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA). Peroxidase activity was imaged using a Chromogen DAB Kit (Leica) for 10 minutes. For uPAR, deparaffinized sections were incubated with a primary mouse monoclonal uPAR antibody diluted 1:500 in antibody diluent (DAKO). Peroxidase activity was imaged using the liquid DAB Substrate-Chromogen kit (K1497) for 10 minutes.

Immunostained slides were evaluated by two independent pathologists. Expression levels in the immunostained specimens were evaluated based on histological subgroups, including podocytes, mesangium, proximal tubules, distal tubules, collecting ducts, damaged tubules, interstitium, and inflammatory cells. A semiquantitative assessment of uPA, uPAR, and PAI-1 expression was carried out according to the following criteria: 0 (no positive staining in cells), 1 (up to 25%), 2 (26% to 50%), and 3 (> 50%).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

uPA and PAI-1 concentrations in stored serum samples were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with the Human Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Activity ELISA Kit (Cell Sciences Inc., Canton, MA, USA) and a Human PAI-1 Activity ELISA Kit (Cell Sciences Inc.), respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis

The biopsies were classified into three groups according to the expression of uPA and uPAR on podocytes: uPA, uPAR, and a negative group. When uPA expression was positive, uPAR was also positive in all cases without exception (uPA group). Biopsies that were positive for uPAR but not uPA were classified as the uPAR group. In the negative group, neither uPA nor uPAR was positive.

Proteinuria and serum creatinine levels were compared among the groups. In addition, the prevalences of the variables of the Oxford classification for IgA GN were compared among the groups [13].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS software package version 14 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are presented as means ± SD, and categorical variables are presented as frequencies (in percent). Differences between the groups were compared using Student t test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Results were considered statistically significant when the p value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

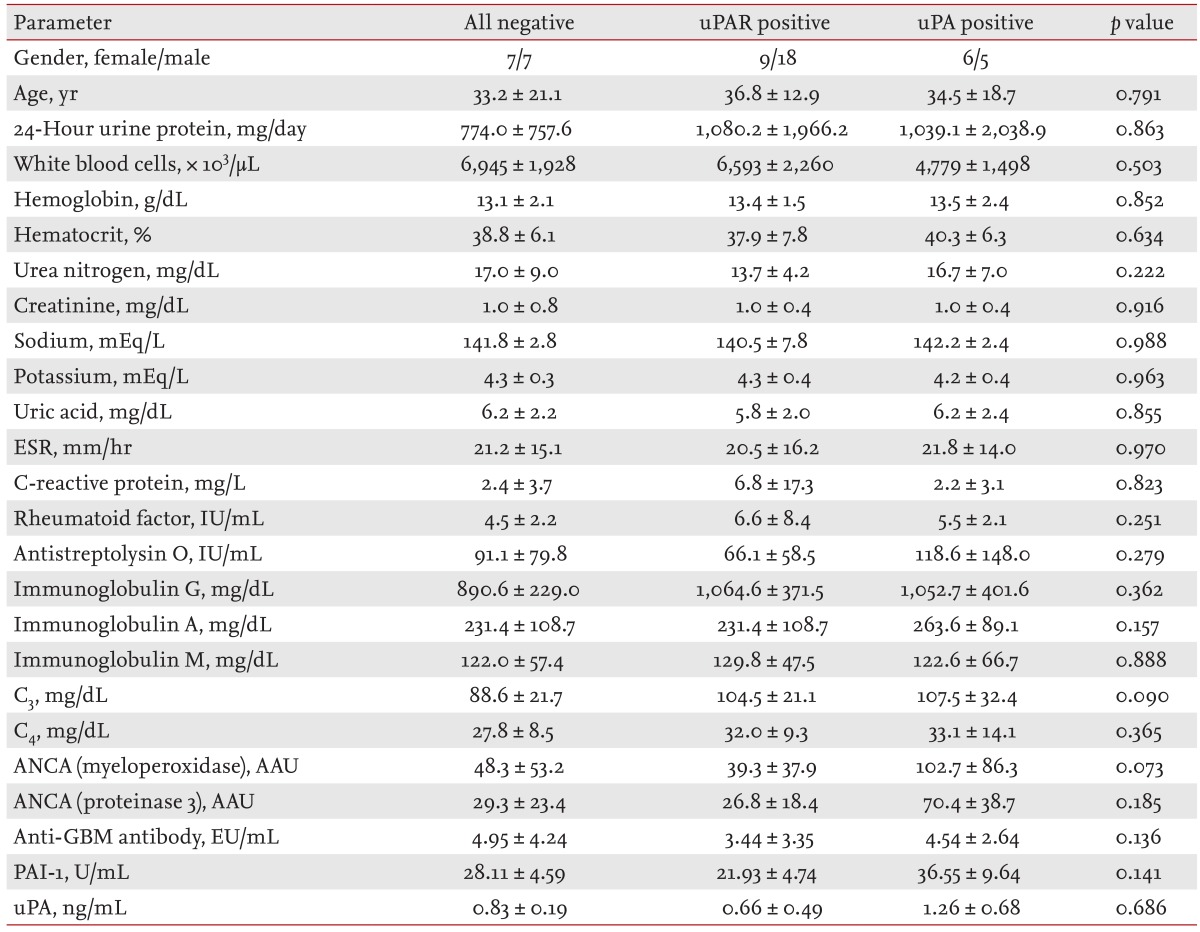

Of the 52 patients, seven had a drug history of angiotensin II-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker prescription for more than 1 month before biopsy (perindopril, one patient; losartan, two patients; valsartan, three patients; and telmisartan, one patient). Table 1 shows the baseline laboratory results for all patients.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and baseline laboratory results in immunoglobulin A glomerulonephritis patients according to the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)-uPA receptor expression pattern on podocytes

Values are presented as mean ± SD.

uPAR, urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; AAU, auto-antibody unit; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.

The uPA was positive in the podocytes of 11 patients and uPAR was positive in 38 patients. The intensity of uPA and/or uPAR on the podocytes was 1+ in all cases. Therefore, the results for uPA and uPAR staining were reported as positive or negative. All the uPA-positive specimens were also positive for uPAR (uPA group, 11 cases). In some cases, podocytes were positive for uPAR but not uPA (uPAR group, 27 cases). PAI-1 was not expressed on podocytes in all cases. The mesangium and the capillary wall of the glomeruli were negative for uPA, uPAR, and PAI-1.

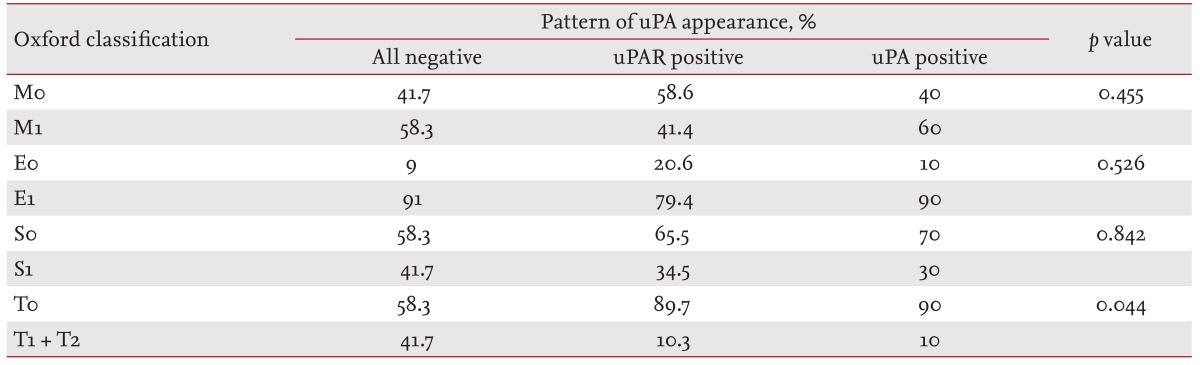

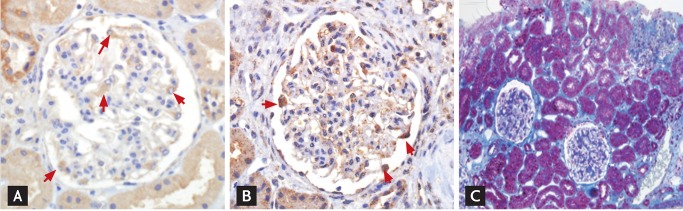

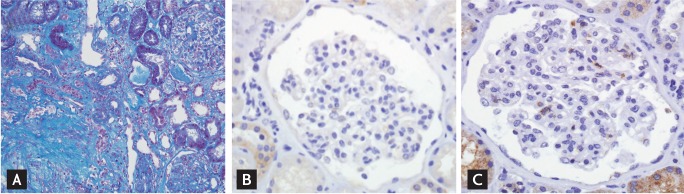

The prevalence of tubulointerstitial fibrosis was significantly higher when uPAR, with or without uPA, was negative in the podocytes (p = 0.044) (Table 2, Figs. 1 and 2). However, this association was not observed in the prevalence of the mesangial hypercellularity (p = 0.455), segmental glomerulosclerosis (p = 0.526), or endocapillary hypercellularity (p = 0.842).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Oxford classification variables according to the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)-uPA receptor expression pattern on podocytes in immunoglobulin A glomerulonephritis patients

uPAR, urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor.

Figure 1.

Expression of both urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and uPA receptor (uPAR) on podocytes in the absence of interstitial fibrosis. Note that both uPA (A, ×400) and uPAR (B, ×400) are positive in the podocyte (red arrows), while (C, Masson's trichrome stain, ×200) fibrosis in the interstitium is negligible.

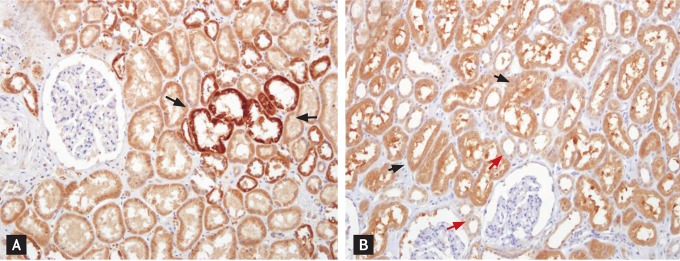

Figure 2.

Prominent interstitial fibrosis without expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and uPA receptor (uPAR) on podocytes. Note that the fibrosis in the interstitium is prominent (A, Masson's trichrome stain, ×200), while neither uPA (B, ×400) nor uPAR (C, ×400) is positive in the podocyte.

In the tubules, uPA, uPAR, and PAI-1 were positive in all cases, albeit the intensity of the reactivity was variable. The distal tubules and collecting duct were more strong reactive for uPA than the proximal tubules (Fig. 3A), while the proximal tubules were more strongly positive for PAI-1 in all subjects (Fig. 3B). The intensity of uPAR expression was neither distinguishable between the proximal and distal tubules nor had any correlation with the pathologic findings. Therefore, we did not attempt any statistical analysis of uPA, uPAR, and PAI-1 expression in the tubules and collecting ducts. The interstitium was negative for uPA, uPAR, and PAI-1. Serum uPA and PAI-1 levels showed no relationships with the pathologic findings, clinical parameters, or uPA and PAI-1 staining intensities.

Figure 3.

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and uPA receptor (uPAR) in renal tubules. (A) The distal nephrotic ducts (black arrows) tended to be more strongly reactive for uPA than the proximal tubules (×200). (B) The proximal tubules (black arrows) tended to be more strongly positive for PAI-1 than the distal nephron (red arrows) (×200).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate that the prevalence of tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis is significantly lower when uPA and uPAR are expressed on podocytes. There are two possible explanations for this association. One is that the uPA or uPAR on the podocytes inhibits interstitial fibrosis. The other possibility is that the expression of uPA and/or uPAR on the podocytes is not the cause but rather a consequence of interstitial fibrosis. However, in the last decade, several studies have reported evidence that renal uPA and uPAR attenuate the interstitial fibrosis caused by renal injury [10-12].

It is well known that uPA and uPAR form a multifunctional system capable of concurrently regulating pericellular proteolysis, cell-surface adhesion, and mitogenesis [14]. In the present study, uPA presentation on podocytes was always accompanied by uPAR. However, uPAR presented with or without uPA. There was no difference in pathology or clinical parameters between the uPA (uPA+, uPAR+) and uPAR (uPA-, uPAR+) groups. Extracellular pro-uPA is known to interact with its plasma membrane receptor, and after activation it triggers localized proteolysis [15,16]. Binding to its receptor may either render the proenzyme more susceptible to activation by other factors (plasmin, u-PA itself, or other still unidentified components of the system) or may directly induce activity in the single chain of uPA.

PAI-1 is thought to be the primary inhibitor of uPA. PAI-1 inhibits uPA by forming a stable complex with a 1:1 stoichiometry [17]. In addition to binding to uPA, PAI-1 can also attach to the ECM protein vitronectin [18]. Binding to vitronectin allows PAI-1 to modulate cellular adhesion and migration [19]. Receptor-bound two-chain uPA is protected from certain inhibitors, in contrast to free two-chain uPA, which is rapidly inactivated by PA inhibitors [20]. Contrary to our expectation, PAI-1 was not expressed on podocytes.

During the last several years, the possible roles of uPA in the development of glomerulopathy have emerged, specifically in the development of albuminuria [6] and mesangial cell survival/apoptosis [7] and the inflammation-fibrosis process in glomeruli [8]. Sappino et al. [21] suggest that uPA may contribute to the maintenance of tubular potency by catalyzing extracellular proteolysis to prevent or circumvent protein precipitation. Wei et al. [22] identified serum soluble uPAR as a circulating factor that may cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. However, the source of the circulating uPAR and the factors regulating its production have not been identified. Three models of production, namely autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine, can be distinguished according to the source of the ligand and the location of its receptors. In the past, we measured t-PA, uPA, and total fibrinolytic activity in blood samples from the renal artery and veins of kidney donors [23]. The uPA level is significantly higher in the renal vein than in the renal artery, suggesting that the kidney may be an essential source of uPA in the systemic circulation. In the current study, there was no relationship between plasma levels of uPA and PAI-1 and their staining intensity or pattern of expression on podocytes and tubules. Further studies are required to investigate the pathophysiological roles of uPA and/or uPAR entering the systemic circulation via the renal vein.

In conclusion, uPA and/or uPAR expression on podocytes accompanies a decreased prevalence of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. This finding suggests a possible protective effect of podocyte uPA/uPAR expression against interstitial fibrosis in IgA GN.

KEY MESSAGE

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and/or uPA receptor (uPAR) expression on podocytes accompanies a decreased prevalence of tubulointerstitial fibrosis.

In immunoglobulin A glomerulonephritis, it suggests a possible protective effect of podocyte uPA/uPAR expression against interstitial fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Binder BR, Mihaly J, Prager GW. uPAR-uPA-PAI-1 interactions and signaling: a vascular biologist's view. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwaki T, Urano T, Umemura K. PAI-1, progress in understanding the clinical problem and its aetiology. Br J Haematol. 2012;157:291–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen W, Jin WQ, Chen LF, Williams T, Zhu WL, Fang Q. Urokinase receptor surface expression regulates monocyte migration and is associated with accelerated atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol. 2012;161:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colman RW, Wu Y, Liu Y. Mechanisms by which cleaved kininogen inhibits endothelial cell differentiation and signalling. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:875–885. doi: 10.1160/TH10-01-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laufs S, Schumacher J, Allgayer H. Urokinase-receptor (u-PAR): an essential player in multiple games of cancer: a review on its role in tumor progression, invasion, metastasis, proliferation/dormancy, clinical outcome and minimal residual disease. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1760–1771. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.16.2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patrakka J, Tryggvason K. New insights into the role of podocytes in proteinuria. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:463–468. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tkachuk N, Kiyan J, Tkachuk S, et al. Urokinase induces survival or pro-apoptotic signals in human mesangial cells depending on the apoptotic stimulus. Biochem J. 2008;415:265–273. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eddy AA, Giachelli CM. Renal expression of genes that promote interstitial inflammation and fibrosis in rats with protein-overload proteinuria. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1546–1557. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorenzen J, Shah R, Biser A, et al. The role of osteopontin in the development of albuminuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:884–890. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang G, Kim H, Cai X, et al. Urokinase receptor deficiency accelerates renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1254–1271. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000064292.37793.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaguchi I, Lopez-Guisa JM, Cai X, Collins SJ, Okamura DM, Eddy AA. Endogenous urokinase lacks antifibrotic activity during progressive renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F12–F19. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00380.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Noble N. An unexpected role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 (PAI-1) in renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2502–2503. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society. Roberts IS, Cook HT, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int. 2009;76:546–556. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madsen CD, Sidenius N. The interaction between urokinase receptor and vitronectin in cell adhesion and signalling. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfano D, Franco P, Vocca I, et al. The urokinase plasminogen activator and its receptor: role in cell growth and apoptosis. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:205–211. doi: 10.1160/TH04-09-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis V, Pyke C, Eriksen J, Solberg H, Dano K. The urokinase receptor: involvement in cell surface proteolysis and cancer invasion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;667:13–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb51591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gils A, Declerck PJ. The structural basis for the pathophysiological relevance of PAI-I in cardiovascular diseases and the development of potential PAI-I inhibitors. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:425–437. doi: 10.1160/TH03-12-0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy MJ. The urokinase plasminogen activator system: role in malignancy. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:39–49. doi: 10.2174/1381612043453559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy MJ. Urokinase plasminogen activator and its inhibitor, PAI-1, as prognostic markers in breast cancer: from pilot to level 1 evidence studies. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1194–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behrendt N, List K, Andreasen PA, Dano K. The pro-urokinase plasminogen-activation system in the presence of serpin-type inhibitors and the urokinase receptor: rescue of activity through reciprocal pro-enzyme activation. Biochem J. 2003;371(Pt 2):277–287. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sappino AP, Huarte J, Vassalli JD, Belin D. Sites of synthesis of urokinase and tissue-type plasminogen activators in the murine kidney. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:962–970. doi: 10.1172/JCI115104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei C, El Hindi S, Li J, et al. Circulating urokinase receptor as a cause of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:952–960. doi: 10.1038/nm.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong SY, Yang DH, Kim PN. Urokinase concentration in the renal artery and vein. Nephron. 1992;61:176–180. doi: 10.1159/000186867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]