Abstract

Background

Lung transplantation is the final treatment option in the end stage of certain lung diseases, once all possible conservative treatments have been exhausted. Depending on the indication for which lung transplantation is performed, it can improve the patient’s quality of life (e.g., in emphysema) and/or prolong life expectancy (e.g., in cystic fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension). The main selection criteria for transplant candidates, aside from the underlying pulmonary or cardiopulmonary disease, are age, degree of mobility, nutritional and muscular condition, and concurrent extrapulmonary disease. The pool of willing organ donors is shrinking, and every sixth candidate for lung transplantation now dies while on the waiting list.

Methods

We reviewed pertinent articles (up to October 2013) retrieved by a selective search in Medline and other German and international databases, including those of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT), Eurotransplant, the German Institute for Applied Quality Promotion and Research in Health-Care (Institut für angewandte Qualitätsförderung und Forschung im Gesundheitswesen, AQUA-Institut), and the German Foundation for Organ Transplantation (Deutsche Stiftung Organtransplantation, DSO).

Results

The short- and long-term results have markedly improved in recent years: the 1-year survival rate has risen from 70.9% to 82.9%, and the 5-year survival rate from 46.9% to 59.6%. The 90-day mortality is 10.0%. The postoperative complications include acute (3.4%) and chronic (29.0%) transplant rejection, infections (38.0%), transplant failure (24.7%), airway complications (15.0%), malignant tumors (15.0%), cardiovascular events (10.9%), and other secondary extrapulmonary diseases (29.8%). Bilateral lung transplantation is superior to unilateral transplantation (5-year survival rate 57.3% versus 47.4%).

Conclusion

Seamless integration of the various components of treatment will be essential for further improvements in outcome. In particular, the follow-up care of transplant recipients should always be provided in close cooperation with the transplant center.

For patients with terminal lung conditions such chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), lung transplantation (LuTx) offers treatment to improve quality of life and additionally, in those with certain other diseases—e.g., cystic fibrosis (CF), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)—to prolong life (1, 2, e1). It is used at the point when, despite treatment by all available conservative methods, the patient’s quality of life will be clearly impaired or life shortened if transplantation does not take place (3, 4, e2).

At present, there are four main surgical options when performing a lung transplantation (5, e3, e4). These are:

Unilateral (single lung) transplantation (SLuTx)

Bilateral (double lung) transplantation (DLuTx)

Combined heart–lung transplantation (HLuTx)

Transplantation of individual pulmonary lobes from living donors.

The last of these options is practiced in only a few centers in the world, and at present is burdened with the weight, not only of non-negligible risks for two healthy living donors, but also of an agglomeration of associated ethical difficulties, and for this reason it will not be discussed further in this article (e5).

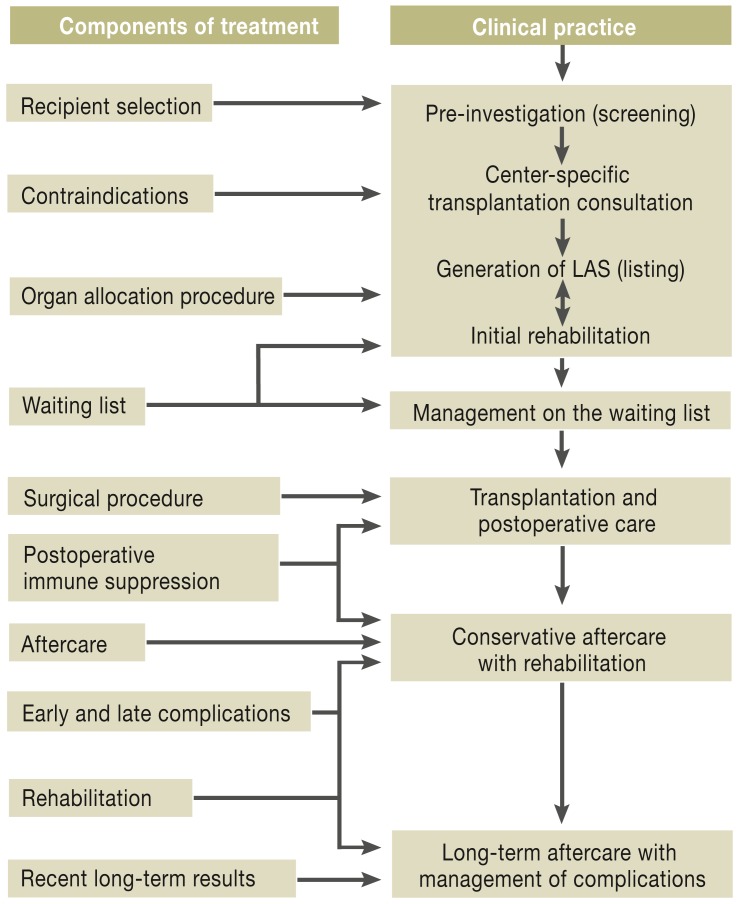

Analysis of data from the relevant registries show that lung transplantations have been continually on the rise over the past 5 years, despite a reduction in numbers of willing donors. Worldwide, the increase is estimated at 30% (International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, ISHLT), while in Germany the figure is 19% (German Foundation for Organ Transplantation, DSO [Deutsche Stiftung Organtransplantation]). According to data from the ISHLT, 3519 lung transplantations were carried out worldwide in 2010, 298 of them in Germany (6, 7, e6). For 2012, the DSO recorded 357 organ transplantations (7). It is against the background of this positive development that the present article has been written to give an up-to-date overview of the topic of lung transplantation, and to answer questions on the key components of the therapy: recipient selection, contraindications, waiting lists, organ allocation procedures, surgical procedure, postoperative immune suppression, aftercare, early and late complications, rehabilitation, and recent long-term results (eFigure).

eFigure.

Interaction between components of treatment and current clinical practice in lung transplantation.

Once the candidate for lung transplantation has attended a qualified transplantation center, the decision about whether to place the patient on the waiting list is made taking account of the patient’s individual disease-specific factors and any contraindications. To optimize long-term results, intensive pneumological support and aftercare in the transplantation centers and obligatory close collaboration with patients’ doctors and local hospitals are essential. If the various elements of therapy interact successfully together, a new lung can mean a new quality of life.

(LAS, lung allocation score)

Recipient selection

Lung transplantation is a highly complex treatment that carries considerable peri- and postoperative risks. It is a treatment option for patients whose pulmonary function, exercise capacity, and quality of life are drastically restricted and whose predicted 5-year survival is less than 50% (for indications and indication criteria, see Table 1 and Box 1) (8, 9, e7– e14). Which form of lung transplantation is carried out depends on the underlying disease. In terms of 5-year survival, DLuTx is superior to SLuTx (57.3% versus 47.4%), so the number of DLuTx procedures has been continually rising since the mid-1990s while the number of SLuTx has remained relatively constant (6). The number of HLuTx procedures carried out worldwide has remained relatively constant at a mean of 70 to 90 procedures per year (6).

Table 1. Indications for lung transplantation in adults (international: ISHLT Registry 1995–2012 [6]; national (German): AQUA Institute 2008–2012).

| ISHLT Registry | |||

|

SLuTx N = 14 197 n (%) |

DLuTx N = 23 384 n (%) |

Total N = 37 581 n (%) |

|

| COPD | 6312 (44.5%) | 6290 (26.9%) | 12 602 (33.5%) |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 4872 (34.3%) | 4032 (17.2%) | 8904 (23.7%) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 229 (1.6%) | 6002 (25.7%) | 6231 (16.6%) |

| α 1-Antitrypsin deficiency | 753 (5.3%) | 1429 (6.1%) | 2182 (5.8%) |

| Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension | 87 (0.6%) | 1073 (4.6%) | 1164 (3.1%) |

| Sarcoidosis | 265 (1.9%) | 689 (2.9%) | 954 (2.5%) |

| Bronchiectasis | 59 (0.4%) | 956 (4.1%) | 1015 (2.7%) |

| Lymphangioleiomyomatosis | 136 (1.0%) | 255 (1.1%) | 391 (1.0%) |

| Congenital heart defect (Eisenmenger syndrome) | 56 (0.4%) | 269 (1.2%) | 325 (0.9%) |

| Re-transplantation (BOS) | 276 (1.9%) | 292 (1.2%) | 568 (1.5%) |

| Re-transplantation (non-BOS) | 182 (1.3%) | 220 (0.9%) | 402 (1.1%) |

| Other | 970 (6.8%) | 1877 (8.0%) | 2843 (7.6%) |

| AQUA Institute* | |||

|

SLuTx N = 218 n (%) |

DLuTx N = 1173 n (%) |

Total N = 1391 n (%) |

|

| Obstructive lung disease (COPD, α 1-antitrypsin deficiency, bronchiectasis) | 88 (40.4%) | 412 (35.1%) | 500 (35.9%) |

| Restrictive lung disease (IPF) | 96 (44.0%) | 329 (28.0%) | 425 (30.6%) |

| Pulmonary hypertension (PAH and Eisenmenger syndrome) | 6 (2.8%) | 53 (4.5%) | 59 (4.2%) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 7 (3.2%) | 240 (20.5%) | 247 (17.8%) |

| Other (incl. lymphangioleiomyomatosis, sarcoidosis and re-transplantations) | 21 (9.6%) | 139 (11.9%) | 160 (11.5%) |

ISHLT, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; AQUA, Institute for Applied Quality Improvement and Research in Health Care (Institut für angewandte Qualitätsförderung und Forschung im Gesundheitswesen);

SLuTx, single lung transplantation; DLuTx, double lung transplantation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension;

BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; N, total number of patients, n = subgroup.

*The data of the AQUA Institute relate to the disease groups lists; they are not coded into the individual disease entities (analogous to ISHLT)

Box 1. Indication criteria for isolated lung transplantation according to underlying disease.

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)*

Documented abstinence from smoking for >6 months

BODE index >5

FEV1 <20% of normal

Dlco 20% of normal

Long-term oxygen therapy with noninvasive ventilation

Pulmonary hypertension or cor pulmonale

-

Manifest ventilatory failure (hypercapnia,

CO2 partial pressure >50 mm Hg)

Progressive reduction of physical capacity

-

Fibrotic lung disease

Respiratory failure at rest (initiation of oxygen therapy)

Pulmonary hypertension

(Dis)continuous deterioration of pulmonary function under standard medical treatment

FVC <60% of normal

Drop in FVC by ≥10% within 6 months

Dlco <39%

Drop in pulse oximetry by <88% (in 6MWT)

Honeycomb structure on high-resolution CT (fibrosis score >2)

-

Cystic fibrosis

FEV1 <30% of normal

Oxygen partial pressure <55 mm Hg

CO2 partial pressure >50 mm Hg

Exacerbations requiring intensive care

Increasingly frequent infections requiring inpatient antibiotic therapy

Recurrent or refractory pneumothorax

Recurrent hemoptysis despite attempted embolization

Pulmonary hypertension

Progressive weight loss (“wasting”) with BMI <18 kg/m2

-

Pulmonary hypertension

Ability to walk limited to <380 m (in 6MWT)

Maximum oxygen intake <10.4 mL/min/kg

NYHA functional stage IV

Signs of manifest right heart failure despite optimized medical treatment

Cardiac index <2 L/min/m2

Right atrial pressure >15 mm Hg

Failure of intravenous epoprostenol therapy

*In COPD, to objectivize the decision criteria for LuTx, the BODE index is used, which is comprised of the following parameters: BMI = body mass index, FEV1 = functional 1-second capacity, dyspnea severity on the MMRC (modified Medical Research Council) scale, and 6MWT = 6-minute walk test. Dlco = diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, FVC = forced vital capacity, NYHA = New York Heart Association

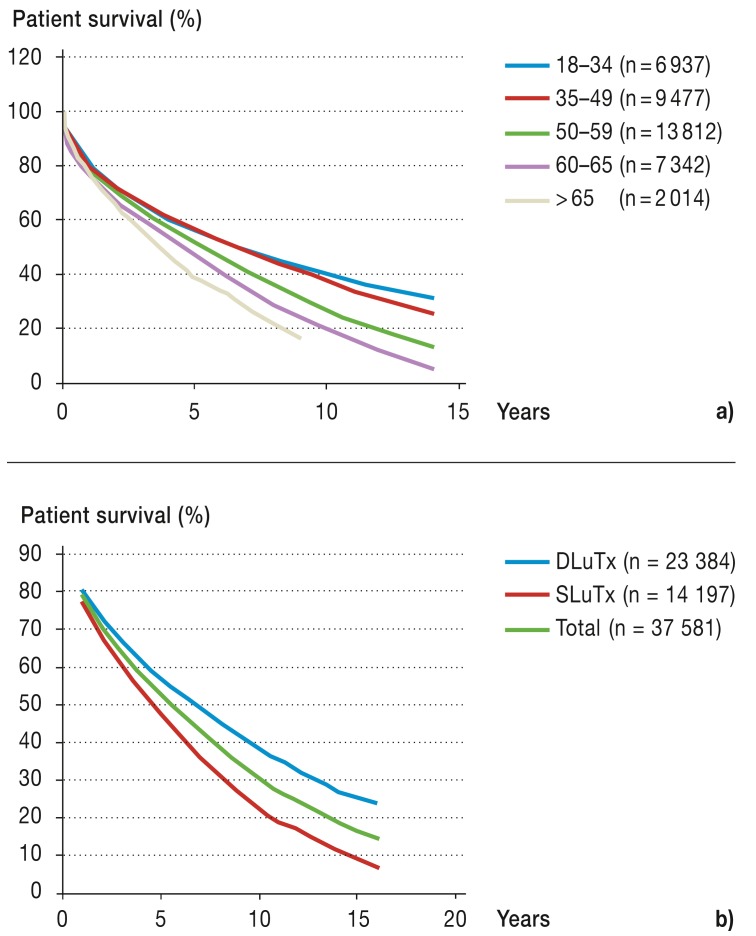

Older patients have a poorer survival rate after lung transplantation than do younger ones (Figure 1a) (6, e6, e15, e16). For this reason, the surgical indications for SLuTx in patients over the age of 60, DLuTx in patients over the age of 55, and HLuTx in patients over the age of 50 should be tested with a critical eye (Figure 1b) (8). However, a patient’s actual age is not per se an exclusion criterion for transplantation (10, e17).

Figure 1.

Patient survival

a) According to age group (transplantation period January 1990 to June 2011 [6])

b) According to surgical procedure (transplantation period January 1994 to June 2011 [6])

DLuTx, double lung transplantation; SLuTx, single lung transplantation

Evaluation of the patient’s biological age has proved useful for guidance (among other things for determining risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic disease, and evaluation of data on lifestyle and psychosocial environment) (e18, e19).

Contraindications

The selection of suitable candidates to receive a transplant is done at the transplantation center, taking account of disease-specific factors, analysis of risk factors, and any contraindications present (Box 2) (11– 14, e7, e16, e20, e21). Poor physical status and severe organ dysfunction can be contraindications for transplantation in any age group. On the other hand, with intensive physiotherapeutic exercise and targeted rehabilitation, the condition even of patients with severe, advanced-stage chronic lung disease can be improved to the point at which they are ready to undergo transplantation (e22– e25).

Box 2. Absolute and relative contraindications for isolated lung transplantation*.

-

Absolute contraindications

Florid infection

-

Malignant tumor

(Not an absolute contraindication if:

Disease-free for at least 2 years

-

Disease-free for at least 5 years for

Renal cell carcinoma stage II

Breast cancer stage II

Colorectal cancer above Duke stage A

Melanoma Clark level II)

Addictive behavior (including tobacco consumption) during the past 6 months

-

Relative contraindications

-

General physical status

Cachexia (approx. <70% of ideal weight), massively reduced muscle mass

Obesity (approx. >130% of ideal weight)

-

Mechanical ventilation

(exception: non-invasive, intermittent self-ventilation)

-

Concomitant disease

HIV infection or infection by panresistant pathogens, pulmonary fungal infection

Renal failure (creatinine clearance <50% of normal)

Liver disease (chronic aggressive hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or liver cirrhosis with significantly impaired function)

Refractory coronary heart disease or significantly impaired left ventricular function

(Pronounced) diverticulosis

Burkholderia cepacia (type III)

Symptomatic osteoporosis with fractures

Neurological, neuromuscular, and psychiatric diseases (myopathy, seizure disorders, multiple sclerosis, cerebrovascular diseases, psychiatric illness, etc.)

Systemic disease with significant extrapulmonary manifestation (vasculitis, collagenosis)

-

Psychosocial problems, poor compliance with treatment so far

*Adapted from (e21)

Waiting list and organ allocation procedure

Early attendance at a transplantation center (there are 14 at present in Germany) is obligatory (Case illustration). The time at which a patient is placed on the waiting list is determined by the disease course and the expected waiting time until transplantation (Eurotransplant: <12 months for 74% of patients in 2012) (7, 15, e26– e29). A basic diagnostic program is followed by consultations between the patient and the transplantation team (Table 2a): based on symptoms, clinical findings, patient motivation, and the expected risk–benefit ratio between transplantation and the natural course of the disease, decisions are made about whether to carry out further investigations (“screening,” Table 2b) (16, e7, e18). Direct statistical comparison between predicted survival in the natural course of the underlying disease and actual survival after lung transplantation is not possible, however (9). Once the patient has been placed on the waiting list, the waiting time until transplantation takes place should be used to correct over- or underweight, update the patient’s immunization status, and carry out muscle strengthening exercise (17, 18, e25, e30, e31).

CASE ILLUSTRATION.

A 58-year-old patient without significant concomitant disease had for years been under the care of a consultant pulmonologist for severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Despite maximum medical therapy, he suffered progressive impairment of physical capacity (BODE index >5; spirometry: FEV1 < 25% of normal; Dlco <20% of normal; global respiratory failure with long-term oxygen therapy: hypercapnia paCO2 >50 mm Hg). No further therapeutic approaches were considered. By coincidence, the patient happened in his private life to meet a chest surgeon, who recommended an immediate appointment at a transplantation center. After appropriate assessment and once contraindications had been excluded, the patient was taken on to the Eurotransplant waiting list in Autumn 2005. About 7 months later, a double lung transplantation was carried out without complications. After an uncomplicated stay in hospital with optimization of the immune suppression, the patient was transferred barely 4 weeks after surgery to a specialized rehabilitation center. After completing inpatient rehabilitation at a specialized clinic, he returned to normal working and social life. To this day, he attends regularly at the outpatients department at the transplantation center; recently spirometry showed an FEV1 of >70%. The consultant pulmonologist changed his views and now refers patients who might be candidates for lung transplantation for early evaluation at a transplantation center.

BODE index, body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;

DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, functional 1-second capacity; paCO2, arterial partial CO2 pressure

Table 2. Prerequisites for organ recipients and donors.

| a) Basic diagnostic criteria for attendance at transplantation center | ||

| History | Diagnosis, disease course, any concomitant disease(s) | |

| Current status | Height, weight, exercise capacity (6MWT), requirement for oxygen therapy, noninvasive ventilation, edema | |

| Recent pulmonary function | Body plethysmography | |

| Arterial blood gas analysis | Resting and – if possible – during exercise (alternatively, oxygen saturation after 6MWT) | |

| Basic laboratory values | Complete blood count, differential blood count, coagulation, renal function (cystatin C, creatinine clearance), liver function, Quick test value, determination of blood group and HLA, cytotoxic antibodies (for recipients with autoimmunization), electrophoresis, immunglobulins | |

| Recent echocardiography | To assess right ventricle (systolic right ventricular pressure) | |

| Abdominal ultrasound | To assess abdominal organs | |

| Recent chest CT (≤ 6 months) | High-resolution in patients with interstitial lung disease | |

| Dental examination | To exclude focus of infection | |

| ENT examination | To exclude focus of infection (especially in patients with bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis) | |

| Psychosocial status | Social environment, adherence with therapy so far | |

| b) Further investigations as required by the transplantation center before acceptance onto waiting list | ||

| Special laboratory tests | Immunglobulins, IgG subclasses, lymphocyte populations, viral serology (HIV, HBV, HCV) | |

| Recent sputum culture | Bronchiectasis, necrotizing lung disease | |

| Duplex sonography of extracranial arteries | >45 years (smokers: >40 years) | |

| Gynecological and urological check-up | Irrespective of age | |

| Peripheral capillary wedge pressure; duplex sonography of pelvic and leg arteries if required | >45 years (smokers: >40 years) | |

| Ventilation–perfusion scintigraphy | Quantitative, separately for each side (only when SLuTx is planned) | |

| Recent right heart catheter | RA, PAP, PCWP, PVR,CO (thermodilution) | |

| Left heart catheter or coronary angiography | >45 years (smokers: >40 years) or risk factors for coronary heart disease, in patients in whom the presence of an unrecognized defect is suspected | |

| Colonoscopy | In patients >50 years and those with diverticulosis | |

| c) Basic prerequisites for organ donors | ||

| Minimum criteria (selection) | Age <55 years; blood group compatibility; pao2 >300 mmHg with FiO2 1.0 and PEEP 5 mmHg; normal chest X-ray and bronchoscopy; exclusion criteria: malignant tumor, chest trauma, sepsis | |

| Extended criteria (selection) | Age >55 years; radiological suspicion of infiltrates; suspected aspiration; abnormal bronchial secretion; chest trauma | |

Brain death leads to a series of hemodynamic and inflammatory changes (including a rise in interleukin-8 and increased neutrophil infiltration) that result in tissue damage and abnormal fluid balance. For this reason, organ donor management in the intensive care unit is extremely important. Because the donor criteria have been expanded, according to Eurotransplant data the percentage of lungs harvested has gone up from 16.7% in 2003 to 27.1% in 2012. Nonetheless, the majority of multiorgan donors do not meet the criteria and lung donation fails. 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; IgG, immunoglobulin G; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; SLuTx, single lung transplantation; RA, right atrium; PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; CO, cardiac output; paO2, arterial partial oxygen pressure; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure

Table adapted from [e18]

In December 2011, listing according to HU/U status (“highly urgent/urgent”) was replaced by a “lung allocation score” (LAS). Like listing by HU/U status, listing by LAS reflects the urgency of the transplantation, but is more transparent, because the LAS is calculated by an internet program (optn.transplant. hrsa.gov; www.eurotransplant.org/cms/index.php?page=las_calculator) that is accessible to both the doctor and the patient. This program sets the mortality rate of patients on the waiting list and the risk associated with lung transplantation against the benefit the patient would receive from transplantation (19, e32). The values calculated in this way are standardized on a scale of 0 to 100 and this gives the individual LAS. The value of the LAS correlates with the urgency of transplantation (e33, e34). All patients on the waiting list undergo outpatient check-ups at frequent intervals to test and document the indications for surgery in order to update and, if appropriate, increase the LAS.

In Germany, there are many more potential lung recipients than donated organs: lungs are harvested from only about one in five multiorgan donors, because the donors do not fulfill the minimum criteria for lung donation (Table 2c). Because of this relative lack of organs, about one in six German patients waiting for a lung transplant dies before receiving it (Eurotransplant 2012: 70 out of 459 patients, i.e., 15.3%). For this reason, at present a move is under way to extend the criteria for organ donation (e35– e38).

The conflicts over the practice of allocating abdominal organs, currently much discussed, raise the question of the status quo of organ allocation. Especially in regard to lung transplantation, it may be noted that, with the “multiple eye principle,” together with the complex data collection included in LAS generation and the obligatory transplantation conferences held at the large centers, the required transparency has already been in place for a long time.

Surgical procedure

Operative time for a SLuTx is 2 to 3 hours; for a DLuTx it is about 4 to 6 hours. A cardiopulmonary bypass is used in about 20% of LuTx, if right heart failure and an excessive rise in pulmonary blood pressure occur during tentative clamping of the pulmonary artery, or if limited gas exchange occurs during one-lung ventilation (20, 21, e39). In addition to being technically simpler, not employing extracorporeal circulation has the advantage of resulting in less reperfusion injury to the allograft in the postoperative period (21). In isolated LuTx, the airway anastomosis on the main bronchi is carried out either end-to-end or using the so-called telescope technique; in HLuTx it is performed en bloc in the region of the distal trachea (e40, e41). The bronchial arterial supply is transected proximally and nonselectively anastomosed in LuTx, with the result that bronchial mucosal ischemia often occurs in the anastomotic region (e42– e45). Retrograde revascularization occurs over the course of several weeks (e46, e47). Minimally invasive procedures (anterolateral thoracotomy without sternotomy) have cosmetic advantages compared to classical thoracosternotomy, and reduce postoperative pain and wound healing disorders. They also leave important structural elements of the thorax intact (e17). Once transferred to the intensive care unit, many patients can be extubated after as little as 24 hours.

Postoperative immune suppression and aftercare

Since the lung has its own immunological competence, transports the entire cardiac output, and thus possesses a large immune-active interaction area, particularly intensive immune suppression is needed after lung transplantation (e48). Normally, immune suppression is achieved with the triple combination of a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) (ciclosporin A, tacrolimus), a cell cycle inhibitor (azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil), and prednisolone (22, 23, e49– e51). In recent years, the introduction of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (sirolimus and everolimus) and of the anti-CD25 antibody (daclizumab, basiliximab—induction therapy only) has widened the range of combinations (24, 25, e52– e54). As to the incidence of chronic transplant rejection, randomized controlled studies have failed to indicate clear superiority of any of the above-named drug groups (26). Triple immune suppression is continued for the rest of life, unless severe adverse effects occur (23).

Infection prophylaxis is with valganciclovir in the case of cytomegalovirus (CMV) (or, where donor and recipient are CMV-negative, with aciclovir) (27, e55– e60), and with lifelong administration of cotrimoxazole in the case of Pneumocystis jrovecii pneumonia (28).

Follow-up care after lung transplantation includes monitoring of transplant function, assessment for known complications of transplantation by lung function tests, as well as clinical, radiological, chemical, and microbiological investigations (18, 29, e61– e65). For early identification of problems on the tightrope walk between chronic organ rejection (bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome [BOS], incidence 38.9% within 5 years) and infection, organ recipients carry out an outpatient lung function measurement at home every day of their lives (30, e66). Usually, lung function increases at first and reaches a relatively stable plateau after 3 to 6 months. If function deteriorates (drop in functional 1-second capacity, [FEV1] by ≥10% of the baseline value), or newly developed cough, mucus, fever, or breathlessness occur, the transplantation center should be contacted immediately for further diagnostic investigation, which may be invasive (e8, e67). In addition to infection and rejection, recurrences of the underlying disease (e.g., sarcoidosis, pulmonary histiocytosis X, or lymphangioleiomyomatosis) may occur in the allograft after LuTx (30, e61, e68, e69), and these must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Early and late complications

The most serious complications during the first month after LuTx are primary graft dysfunction (PGD), donor-mediated pneumonia or pneumonia of other primary infectious origin, antibody-mediated hyperacute rejection (fairly rare), problems with the vascular and bronchial anastomoses, and periods of acute cellular rejection (31, e18, e70– e74) (Table 3a). Average 90-day mortality is 10% (6).

Tabelle 3. Complications after lung transplantation (LuTx).

| a) Main complications after LuTx*1 | ||||||||

| Allograft | Primary transplant dysfunction, necrosis and obstruction of anastomotic region, acute rejection, BOS, drug-induced pneumonitis (sirolimus, everolimus) | |||||||

| Thoracic | Lesions of the phrenic nerve (diaphragm paralysis), recurrent nerve (vocal cord paralysis), vagus nerve (gastroparesis or delayed gastric emptying), and thoracic duct (chylothorax), pneumothorax, pleural effusion | |||||||

| Infections | Bacteria, fungi (esp. Aspergillus spp.), viruses (esp. CMV, HSV, RSV) | |||||||

| Cardiovascular | Air embolism, postoperative pericarditis, thromboembolism, supraventricular tachycardia, arterial hypertension | |||||||

| Gastrointestinal | Esophagitis (Candida or CMV), gastroparesis, gastroesophageal reflux with aspiration, diarrhea or pseudomembranous colitis due to C. difficile, diverticulitis, colon perforation, distal intestinal obstruction syndrome | |||||||

| Hepatobiliary | Hepatitis (CMV, EBV, HEV, HBV, HCV, drug-induced toxicity) | |||||||

| Renal | Acute renal failure, chronic renal failure (esp. calcineurin inhibitor–induced nephropathy) | |||||||

| Neurological | Tremor, seizures, posterior leukoncephalopathy, headache, paresthesias, peripheral neuropathy | |||||||

| Musculoskeletal | Steroid myopathy, rhabdomyolysis (combination of ciclosporin + HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor), osteoporosis, aseptic bone necrosis | |||||||

| Metabolic | Obesity, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipoproteinemia, hyperammonemia | |||||||

| Hematological | Anemia, leukopenia, thrombopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia, thrombotic microangiopathy | |||||||

| Oncological | Post-transplantation lymphoma, skin tumors, other malignant tumors | |||||||

|

*1Adapted from [e18] BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HEV, hepatitis E virus; HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A; HSV, herpes simplex virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus | ||||||||

| b) Incidence rates of important complications after LuTx*2 | ||||||||

| 1 Year | 5 Years | 10 Years | ||||||

| Arterial hypertension | 51.7% | 82.4% | – | |||||

| Renal failure | 23.3% | 55.4% | 74.1% | |||||

| Creatinine ≤ 2.5 mg/dL | 16.2% | 36.5% | 40.3% | |||||

| Creatinine >2.5 mg/dL | 5.2% | 15.0% | 19.8% | |||||

| Dialysis | 1.7% | 3.2% | 8.7% | |||||

| Kidney transplantation | 0.1% | 0.7% | 5.3% | |||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 25.5% | 58.4% | – | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 24.6% | 40.5% | – | |||||

| BOS | 9.5% | 39.7% | 61.6% | |||||

|

*2Follow-up period April 1994 to June 2012 [6]. Because complications are not uniformly reported to the ISHLT Registry, the percentages cited are based on different numbers of patients, and therefore no absolute figures are given here. BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; ISHLT, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation | ||||||||

| c) Incidence of cancer after LuTx*3 | ||||||||

| 1 Year | 5 Years | 10 Years | ||||||

| No cancer | 17 068 (96.4%) | 5040 (84.6%) | 883 (71.2%) | |||||

| Cancer (all) | 630 (3.6%) | 920 (15.4%) | 357 (28.8%) | |||||

| Skin | 199 (31.6%) | 590 (64.1%) | 226 (63.3%) | |||||

| Lymphoma | 243 (38.6%) | 94 (10.2%) | 38 (10.6%) | |||||

| Other | 164 (26.0%) | 227 (24.7%) | 93 (26.1%) | |||||

| Not specified | 24 (3.8%) | 9 (1.0%) | – | |||||

| *3Follow-up period April 1994 to June 2012 [6]. For skin tumors, exposure to sun plays an important role (occurrence varies regionally; registers contain no relevant data). Occurrence of lymphoma is related to Epstein–Barr virus infection and amount of lymph tissue transferred. “Other” cancers include cancer of the bladder, lung, breast, prostate, uterus, liver, and bowel | ||||||||

PGD is the most frequent cause of death in the first 30 days after LuTx (10% to 25%) (6, 31). The clinical features are similar to those of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and mortality is between 50% and 73% (6, 31). Most cases of PGD are caused by ischemia–reperfusion injury. More rarely, infections and rejection reactions may act as triggers (31).

Rejection: clinical features and diagnosis

One-off or recurrent periods of rejection increase the probability of BOS, reduce graft function permanently, and hence endanger the patient’s long-term survival (26, e75, e76). Since most acute rejections of lung allografts occur within the first 2 years after transplantation (33.9%), accurate diagnosis and staging of rejection are essential during this period in particular (e77– e81). Clinical signs of acute cellular rejection are nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, raised body temperature, dyspnea, cough, increased mucus, hypoxemia, drop in FEV1, interstitial infiltrates, and pleural effusions (32). Higher-grade rejection can be accompanied by acute breathlessness with dramatic symptoms (e82). Spirometry can indicate infections and rejection reactions (drop in FEV1), but cannot distinguish between them (e83). Similarly, thoracic imaging can indicate nonspecific changes and hence the possibility of a rejection reaction, but only indirectly (e.g., by showing septal thickening, infiltrates, pleural effusions) (e61). For clinical follow-up after LuTx, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (eosinophilia, lymphocyte proliferation) and transbronchial biopsy (lymphocytic infiltration) have become established as standard techniques for rejection diagnosis, due to their high sensitivity and specificity (33, e84– e87).

Treatment of acute rejection is in accordance with the following parameters. The standard therapy is intravenous administration of 500 to 1000 mg methylprednisolone (15 mg/kg body weight per day) on each of 3 successive days (e88). In the case of steroid-refractory or early recurrent rejection, the immunosuppressive treatment is altered (e.g., change of CNI or exchange of CNI for mTOR inhibitors) (e89). Alternatively—although they are associated with considerable early and late toxicity—monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies may be given.

Infections

Infections are the main cause of death in the first year after transplantation (ISHLT Registry: 38.0%; AQUA Institute: 35%) (e6). In addition to the medical immune suppression, the fact that the lung, unlike other transplantable solid organs, is permanently directly exposed to the environment means that there is an increased risk of infection (34, e90– e92). Furthermore, the lack of cough reflex in the transplant, together with simultaneous reduction of mucociliary clearance due to denervation and interruption of the lymphatics, also play a role (34, e93). Three out of four graft infections occur in the airways, either due to pathogen transfer from the donor or to pathogens descending from the upper airways in recipients who already have chronic bacterial colonization (e.g., those with bronchiectasia or cystic fibrosis) (34, e94– e96). Other predisposing factors are airway stenosis and postoperative ischemia, especially in the area of the anastomosis due to epithelial damage (e41– e43, e47, e97). The incidence of postoperative pneumonia is markedly higher after LuTx than, for example, after heart transplantation (6, e98). During hospitalization, gram-negative pathogens predominate, whereas during the outpatient phase, infections by pneumococci, Hemophilus species, and atypical pathogens prevail (34).

Airway complications

The prevalence of clinically significant airway complications is 10% to 15% (35, e99). Within the first 6 postoperative months, the interruption of the bronchial arterial supply to the donor lung can lead to ischemic necrosis at the bronchial anastomoses (e97). This may be expressed by obstructive granulation tissue (stricture, atelectasis), dehiscence, infections, or bronchomalacia (e100, e101). In addition to the extent of the ischemia in the area of the anastomosis, other risk factors are size disproportion between donor and recipient, and Aspergillus spp. colonization (e102– e104). Treatment options include bronchial stent implantation, bronchoscopic balloon dilation, intrabronchial disobliteration techniques (argon plasma coagulation, laser and cryotherapy) and surgical revision, among others (e104, e105).

Renal complications

Five years after LuTx, 37% of patients show chronic renal failure (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] <50% of the norm) (e106) (Table 3b). Five percent of transplanted patients require dialysis because of preexisting concomitant disease or CNI therapy.

Cardiovascular complications

Five years after transplantation, 82% of patients are suffering from arterial hypertension, 58% from hyperlipoproteinemia, and 41% from diabetes mellitus (6). However, cardiovascular diseases are the cause in only 5% of deaths (32). The reason for this is the younger average age of transplanted patients and their lower life expectancy compared to the normal population. For antihypertensive therapy, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and calcium antagonists are preferred; verapamil and diltiazem raise the concentration of immune suppressants. In the early postoperative period, atrial tachycardia often occurs, caused by electrolyte disturbances, hypoxemia, ischemia, or atrial reentry mechanisms. Pharmacologically, particular attention must be paid to drugs that prolong the Q–T interval (e107).

Malignant tumors

Within the first 5 years after transplantation, 15% of patients with lung transplants develop malignant tumors (Table 3c) (6, 36– 38, e108, e109). For skin tumors, exposure to the sun plays an important role, so these tumors are variably distributed in different regions of the world. The incidence of lymphoma is related both to Epstein–Barr virus infection and to the amount of lymph tissue transferred (e110).

Rehabilitation

The patient’s preoperative physical constitution, together with muscle status, transplant function, complications, immune suppression, and potential risks over the long term, necessitate a structured rehabilitation program (39). In addition to stamina, interval, and strength training, respiratory therapy and physiotherapy, psychological counseling, and nutritional advice are given, to educate the patient about the effects of immune suppression and possible concomitant diseases (diabetes mellitus, renal failure, over- or underweight), and to treat them (e111, e112).

After about 6 to 12 months, patients can gradually start to go back to work or retrain for an occupation involving light physical work, provided anti-infection measures are taken (e113).

Recent long-term results

Compared to the natural course (40, e114), increased survival rates among transplanted patients are reported particularly for the first postinterventional year. In the long term, mainly organ-specific problems occur (eTable a and b) (e6). Irrespective of survival time, what is most important to patients is the marked improvement in quality of life (2, e1, e115, e116). To further optimize long-term results, intensive pulmonological support and follow-up care in the transplantation centers and obligatory close collaboration with patients’ resident practitioner and local hospitals are essential.

eTable. Long-term results (international data: ISHLT Registry 1995–2012 [6]; national data [Germany]: AQUA Institute 2008–2012).

| a) Recipient survival according to underlying disease | ||||||||||

| ISHLT Registry | ||||||||||

| Survival rate (%) | ||||||||||

| Diagnosis | n | 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | 10 Years | |||||

| COPD | 12 914 | 82.1% | 65.7% | 52.4% | 25.8% | |||||

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 8528 | 74.7% | 59.2% | 46.9% | 24.4% | |||||

| Cystic fibrosis | 6164 | 82.9% | 69.3% | 59.6% | 43.5% | |||||

| α 1-Antitrypsin deficiency | 2624 | 79.1% | 65.4% | 56.4% | 34.5% | |||||

| Idiopathic PAH | 1400 | 70.9% | 59.4% | 50.9% | 35.6% | |||||

| Sarcoidosis | 934 | 74.2% | 60.0% | 52.9% | 31.2% | |||||

| AQUA Institute | ||||||||||

| Survival rate (%) | ||||||||||

| Diagnosis | n | 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | 10 Years | |||||

| Obstructive lung disease (COPD, α 1-antitrypsin deficiency, bronchiectasis) | 400 | 79.8% | 59.1% | – | – | |||||

| Restrictive lung disease (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis) | 296 | 70.9% | 60.3% | – | – | |||||

| Pulmonary hypertension (PAH and Eisenmenger syndrome) | 58 | 77.6% | 57.9% | – | – | |||||

| Cystic fibrosis | 190 | 78.9% | 57.6% | – | – | |||||

| Other (incl. lymphangioleiomyomatosis, sarcoidosis and re-transplantations) | 167 | 70.7% | 56.6% | – | – | |||||

| AQUA, Institute for Applied Quality Improvement and Research in Health Care (Institut für angewandte Qualitätsförderung und Forschung im Gesundheitswesen); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ISHLT, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; n, number of patients | ||||||||||

| b) Causes of death after lung transplantation in adults | ||||||||||

| 0–30 Days | 31 Days–1 Year | 1–3 Years | 3–5 Years | 5–10 Years | ||||||

| ISHLT Registry | n = 2725 | n = 4737 | n = 4315 | n = 2449 | n = 2892 | |||||

| AQUA Institute | n = 125 | n = 108 | – | – | – | |||||

| BOS | 0.3% | 4.6% | 25.9% | >29.0% | 25.4% | |||||

| – | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Acute rejection | 3.4% | 1.8% | 1.5% | 0.7% | 0.6% | |||||

| 1% | 4% | – | – | – | ||||||

| Malignant tumors | 0.2% | 5.1% | 9.4% | 12.4% | 15.0% | |||||

| – | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Infection | 19.6% | 38.0% | 23.5% | 19.5% | 18.2% | |||||

| 14% | 35% | – | – | – | ||||||

| Transplant failure | 24.7% | 16.7% | 18.7% | 18.0% | 17.8% | |||||

| 13% | 4% | – | – | – | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 10.9% | 4.8% | 4.1% | 4.9% | 5.1% | |||||

| 8% | 1% | – | – | – | ||||||

| Technical | 11.0% | 3.4% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.8% | |||||

| 2% | 6% | – | – | – | ||||||

| Other | 29.8% | 25.6% | 16.0% | 15.1% | 17.0% | |||||

| 36% | 48% | – | – | – | ||||||

| Multiorgan failure | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| 26% | 2% | – | – | – | ||||||

| ISHLT, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; AQUA, Institute for Applied Quality Improvement and Research in Health Care (Institut für angewandte Qualitätsförderung und Forschung im Gesundheitswesen); BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; n, number of patients | ||||||||||

At present, 45 centers report their data directly by entering data manually on the ISHLT’s web-based data input system. In addition, the following organizations input information from 345 participating institutes into the ISHLT data system

- United Network for Organ Sharing (United States of America)

- Eurotransplant (Germany, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Slovenia)

- Organizacion Nacional de Trasplantes (Spain)

- Registro Español de Trasplante Cardíaco (Spain)

- UK Transplant (United Kingdom, Ireland)

- Scandia Transplant (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland)

- Australia and New Zealand Cardiothoracic Organ Transplant Registry (Australia, New Zealand)

- Agence de la biomédecine (France)

Key Messages.

Lung transplantation is a well-established treatment option for patients with end-stage congenital or acquired lung disease when all conservative treatment options have been exhausted. Depending on the underlying disease, it can improve both life expectancy and quality of life.

Criteria for the selection of candidates, in addition to the causative lung disease, are: patient age, existing mobility, nutritional and muscle status, and concomitant extrapulmonary diseases.

Once the indication for lung transplantation has been established, it is important to be in contact with a transplantation center as early as possible in order to minimize mortality during the wait for a transplant.

The continuing development of surgical techniques has markedly reduced early mortality: within the past 25 years, 90-day mortality has reduced from 19.4% to 10.0%. In the postoperative period, acute (3.4%) or chronic transplant rejections (29.0%), infections (38.0%), graft failure (24.7%), airway complications (15%), malignant tumors (15.0%), and other extrapulmonary sequelae (29.8%) are to be expected. At the end of 5 years, survival rates of almost 60% are achieved.

Ongoing collaboration between the transplantation center on the one hand and the patient’s resident practioner and the hospital responsible for the patient’s aftercare on the other will contribute to improving the long-term results.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA.

The authors thank Katrin Pitzer-Hartert, MA, for editorial input in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Senbaklavaci has received a research grant (third-party funding) in chest surgery from the German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (DGTHG, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Thorax-, Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie)

The other authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Kugler C, Gottlieb J, Warnecke G, et al. Health-related quality of life after solid organ transplantation: A prospective, multiorgan cohort study. Transplantation. 2013;96:316–323. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31829853eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer JP, Singer LG. Quality of life in lung transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:421–430. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper JD, Pearson FG, Patterson GA, et al. Technique of successful lung transplantation in humans. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;93:173–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson GA, Cooper JD, Goldman B, et al. Technique of successful clinical double-lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45:626–633. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)64763-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puri V, Patterson GA. Adult lung transplantation: technical considerations. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;20:152–164. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusen RD, Christie JD, Edwards LB, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: thirtieth adult lung and heart-lung transplant report-2013 focus theme: age. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:965–978. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deutsche Stiftung Organtransplantation (DSO). Organspende und Transplantation in Deutschland. Jahresbericht. 2012. www.dso.de/uploads/tx_dsodl/DSO_JB12_d_Web.pdf (last accessed on 13 January 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah PD, Orens JB. Guidelines for the selection of lung-transplant candidates. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2012;17:467–473. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328357d898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thabut G, Fournier M. Assessing survival benefits from lung transplantation. Rev Mal Respir. 2011;28:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machuca TN, Camargo SM, Schio SM, et al. Lung transplantation for patients older than 65 years: is it a feasible option? Transplant Proc. 2011;43:233–235. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hook JL, Lederer DJ. Selecting lung transplant candidates: where do current guidelines fall short? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6:51–61. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreider M, Hadjiliadis D, Kotloff RM. Candidate selection, timing of listing, and choice of procedure for lung transplantation. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaty CA, George TJ, Kilic A, Conte JV, Shah AS. Pre-transplant malignancy: an analysis of outcomes after thoracic organ transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanaan R. Indications and contraindications to lung transplant: patient selection. Rev Pneumol Clin. 2010;67:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pneumo.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smits JM, Vanhaecke J, Haverich A, et al. Waiting for a thoracic transplant in Eurotransplant. Transpl Int. 2006;19:54–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orens JB, Estenne M, Arcasoy S, et al. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2006 update - a consensus report from the Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M, Mathur S, Chowdhury NA, Helm D, Singer LG. Pulmonary rehabilitation in lung transplant candidates. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartels MN, Armstrong HF, Gerardo RE, et al. Evaluation of pulmonary function and exercise performance by cardiopulmonary exercise testing before and after lung transplantation. Chest. 2011;140:1604–1611. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strueber M, Reichenspurner H. Die Einführung des Lungenallokations-Scores für die Lungentransplantation in Deutschland. Dtsch Arztebl. 2011;108 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yusen RD. Technology and outcomes assessment in lung transplantation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:128–136. doi: 10.1513/pats.200809-102GO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottlieb J. Update on lung transplantation. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2008;2:237–247. doi: 10.1177/1753465808093514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penninga L, Penninga EI, Møller CH, Iversen M, Steinbrüchel DA, Gluud C. Tacrolimus versus cyclosporin as primary immunosuppression for lung transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;31 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008817.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Floreth T, Bhorade SM. Current trends in immunosuppression for lung transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:172–178. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Pablo A, Santos F, Solé A, et al. Recommendations on the use of everolimus in lung transplantation. Transplant Rev. 2013;27:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swarup R, Allenspach LL, Nemeh HW, Stagner LD, Betensley AD. Timing of basiliximab induction and development of acute rejection in lung transplant patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1228–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Todd JL, Palmer SM. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: the final frontier for lung transplantation. Chest. 2011;140:502–508. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uhlin M, Mattsson J, Maeurer M. Update on viral infections in lung transplantation. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2012;18:264–270. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283521066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmona EM, Limper AH. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of pneumocystis pneumonia. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2011;5:41–59. doi: 10.1177/1753465810380102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuurmans MM, Benden C, Inci I. Practical approach to early postoperative management of lung transplant recipients. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143 doi: 10.4414/smw.2013.13773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vivodtzev I, Pison C, Guerrero K, et al. Benefits of home-based endurance training in lung transplant recipients. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;177:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki Y, Cantu E, Christie JD. Primary graft dysfunction. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:305–319. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dilling DF, Glanville AR. Advances in lung transplantation: the year in review. Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glanville AR. The role of surveillance bronchoscopy post-lung transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:414–420. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sims KD, Blumberg EA. Common infections in the lung transplant recipient. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porhownik NR. Airway complications post lung transplantation. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:174–180. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835d2ef9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belli EV, Landolfo K, Keller C, Thomas M, Odell J. Lung cancer following lung transplant: Single institution 10 year experience. Lung Cancer. 2013;81:451–454. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muchtar E, Kramer MR, Vidal L, et al. Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder in lung transplant recipients: A 15-year single institution experience. Transplantation. 2013;96:657–663. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31829b0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robbins HY, Arcasoy SM. Malignancies following lung transplantation. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li M, Mathur S, Chowdhury NA, Helm D, Singer LG. Pulmonary rehabilitation in lung transplant candidates. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah RJ, Kotloff RM. Lung transplantation for obstructive lung diseases. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:288–296. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Singer JP, Chen J, Blanc PD, Leard LE, Kukreja J, Chen H. A thematic analysis of quality of life in lung transplant: the existing evidence and implications for future directions. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:839–850. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Boffini M, Ranieri VM, Rinaldi M. Lung transplantation: is it still an experimental procedure? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:53–61. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32833500a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Knoop C, Estenne M. Disease-specific approach to lung transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:466–470. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283303607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Date H. Update on living-donor lobar lung transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2011;16:453–457. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32834a9997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Panocchia N, Bossola M, Silvestri P, et al. Ethical evaluation of risks related to living donor transplantation programs. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2601–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Christie JD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: 29th adult lung and heart-lung transplant report-2012. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Kreider M, Kotloff RM. Selection of candidates for lung transplantation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:20–27. doi: 10.1513/pats.200808-097GO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Todd JL, Palmer SM. Lung transplantation in advanced COPD: is it worth it? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:365–372. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Shah RJ, Kotloff RM. Lung transplantation for obstructive lung diseases. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:288–296. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Eskander A, Waddell TK, Faughnan ME, Chowdhury N, Singer LG. BODE index and quality of life in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease before and after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1334–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Gottlieb J. Lung transplantation for interstitial lung diseases and pulmonary hypertension. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:281–287. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Corris PA. Lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:297–304. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Rosenblatt RL. Lung transplantation in cystic fibrosis. Respir Care. 2009;54:777–787. doi: 10.4187/002013209790983197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Lordan JL, Corris PA. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and lung transplantation. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5:441–454. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Tomaszek SC, Fibla JJ, Dierkhising RA, et al. Outcome of lung transplantation in elderly recipients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Thabut G, Ravaud P, Christie JD. Determinants of the survival benefit of lung transplantation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1156–1163. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1283OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Fischer S, Meyer K, Tessmann R, et al. Outcome following single vs bilateral lung transplantation in recipients 60 years of age and older. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1369–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Dierich M, Fuehner T, Welte T, Simon A, Gottlieb J. Lung transplantation. Indications, long-term results and special impact of follow-up care. Internist. 2009;50:561–571. doi: 10.1007/s00108-008-2271-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Jackson SH, Weale MR, Weale RA. Biological age - what is it and can it be measured? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;36:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Reynaud-Gaubert M, Boniface S, Métivier AC, Kessler R. When should patients be referred by the physician to the lung transplant team? Patient selection, indications, timing of referral and preparation for lung transplantation. Rev Mal Respir. 2008;25:1251–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0761-8425(08)75090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Gottlieb J, Welte T, Höper MM, Strüber M, Niedermeyer J. Lung transplantation. Possibilities and limitations. Internist. 2004;45:1246–1259. doi: 10.1007/s00108-004-1292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Florian J, Rubin A, Mattiello R, da Fontoura FF, Camargo de J, Teixeira PJ. Impact of pulmonary rehabilitation on quality of life and functional capacity in patients on waiting lists for lung transplantation. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39:349–356. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132013000300012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Wickerson L, Mathur S, Helm D, Singer L, Brooks D. Physical activity profile of lung transplant candidates with interstitial lung disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2013;33:106–112. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3182839293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Langer D, Cebrià i Iranzo MA, Burtin C, et al. Determinants of physical activity in daily life in candidates for lung transplantation. Respir Med. 2012;106:747–754. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Mathur S, Hornblower E, Levy RD. Exercise training before and after lung transplantation. Phys Sportsmed. 2009;37:78–87. doi: 10.3810/psm.2009.10.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.de Pablo A, Juarros L, Jodra S, et al. Lung Transplantation Unit. Analysis of patients referred to a lung transplantation unit. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2351–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Toyoda Y, Bhama JK, Shigemura N, et al. Efficacy of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:1065–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Hoopes CW, Kukreja J, Golden J, Davenport DL, Diaz-Guzman E, Zwischenberger JB. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to pulmonary transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:862–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e29.Orens JB, Garrity ER., Jr General overview of lung transplantation and review of organ allocation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:13–19. doi: 10.1513/pats.200807-072GO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e30.Nakamura Y, Tanaka K, Shigematsu R, Nakagaichi M, Inoue M, Homma T. Effects of aerobic training and recreational activities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Rehabil Res. 2008;31:275–283. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e3282fc0f81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.Keating D, Levvey B, Kotsimbos T, et al. Lung transplantation in pulmonary fibrosis: challenging early outcomes counterbalanced by surprisingly good outcomes beyond 15 years. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:289–291. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e32.Wille KM, Harrington KF, deAndrade JA, Vishin S, Oster RA, Kaslow RA. Disparities in lung transplantation before and after introduction of the lung allocation score. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:684–692. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e33.McShane PJ, Garrity ER., Jr Impact of the lung allocation score. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:275–280. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e34.Smits JM, Nossent GD, de Vries E, et al. Evaluation of the lung allocation score in highly urgent and urgent lung transplant candidates in Eurotransplant. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e35.Sommer W, Kühn C, Tudorache I, et al. Extended criteria donor lungs and clinical outcome: Results of an alternative allocation algorithm. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e36.Pêgo-Fernandes PM, Samano MN, Fiorelli AI, et al. Recommendations for the use of extended criteria donors in lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:216–219. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Smits JM, van der Bij W, Van Raemdonck D, et al. Defining an extended criteria donor lung: an empirical approach based on the Eurotransplant experience. Transpl Int. 2011;24:393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2010.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e38.Meers C, van Raemdonck D, Verleden GM, et al. The number of lung transplants can be safely doubled using extended criteria donors; a single-center review. Transpl Int. 2010;23:628–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.Machuca TN, Schio SM, Camargo SM, et al. Prognostic factors in lung transplantation: the Santa Casa de Porto Alegre experience. Transplantation. 2011;91:1297–1303. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821ab8e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e40.Fitzsullivan E, Gries CJ, Phelan P, et al. Reduction in airway complications after lung transplantation with novel anastomotic technique. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e41.Murthy SC, Gildea TR, Machuzak MS. Anastomotic airway complications after lung transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15:582–587. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32833e3e6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e42.Iga N, Oto T, Okada M, et al. Detection of airway ischaemic damage after lung transplantation by using autofluorescence imaging bronchoscopy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt437. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e43.Samano MN, Minamoto H, Junqueira JJ, et al. Bronchial complications following lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:921–926. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e44.Weder W, Inci I, Korom S, et al. Airway complications after lung transplantation: risk factors, prevention and outcome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e45.Moreno P, Alvarez A, Algar FJ, et al. Incidence, management and clinical outcomes of patients with airway complications following lung transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e46.Pettersson GB, Karam K, Thuita L, et al. Comparative study of bronchial artery revascularization in lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:894–900. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e47.Pettersson GB, Yun JJ, Nørgaard MA. Bronchial artery revascularization in lung transplantation: techniques, experience, and outcomes. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15:572–577. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32833e16fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e48.Witt CA, Hachem RR. Immunosuppression: what’s standard and what’s new? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:405–413. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e49.Treede H, Glanville AR, Klepetko W, et al. European and Australian investigators in lung transplantation. Tacrolimus and cyclosporine have differential effects on the risk of development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: results of a prospective, randomized international trial in lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e50.Benden C, Danziger-Isakov L, Faro A. New developments in treatment after lung transplantation. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:737–746. doi: 10.2174/138161212799315902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e51.Bosma OH, Vermeulen KM, Verschuuren EA, Erasmus ME, van der Bij W. Adherence to immunosuppression in adult lung transplant recipients: prevalence and risk factors. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1275–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e52.Peddi VR, Wiseman A, Chavin K, Slakey D. Review of combination therapy with mTOR inhibitors and tacrolimus minimization after transplantation. Transplant Rev. 2013;27:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e53.von Suesskind-Schwendi M, Brunner E, Hirt SW, et al. Suppression of bronchiolitis obliterans in allogeneic rat lung transplantation-effectiveness of everolimus. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2013;65:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e54.Säemann MD, Haidinger M, Hecking M, Hörl WH, Weichhart T. The multifunctional role of mTOR in innate immunity: implications for transplant immunity. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2655–2661. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e55.Verleden SE, Vandermeulen E, Ruttens D, et al. Neutrophilic reversible allograft dysfunction (NRAD) and restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS) Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:352–360. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e56.Wiita AP, Roubinian N, Khan Y, et al. Cytomegalovirus disease and infection in lung transplant recipients in the setting of planned indefinite valganciclovir prophylaxis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14:248–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2012.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e57.Patel N, Snyder LD, Finlen-Copeland A, Palmer SM. Is prevention the best treatment? CMV after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:539–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e58.Zamora MR, Budev M, Rolfe M, et al. RNA interference therapy in lung transplant patients infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:531–538. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0422OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e59.Lease ED, Zaas DW. Update on infectious complications following lung transplantation. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:206–209. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328344dba5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e60.Bridevaux PO, Aubert JD, Soccal PM, et al. Incidence and outcomes of respiratory viral infections in lung transplant recipients: a prospective study. Thorax. 2014;69:32–38. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e61.Diez Martinez 6 P, Pakkal M, Prenovault J, et al. Postoperative imaging after lung transplantation. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e62.Patel JK, Kobashigawa JA. Thoracic organ transplantation: laboratory methods. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1034:127–143. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-493-7_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e63.Nakajima T, Palchevsky V, Perkins DL, Belperio JA, Finn PW. Lung transplantation: infection, inflammation, and the microbiome. Semin Immunopathol. 2011;33:135–156. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e64.Verleden GM, Vos R, Verleden SE, et al. Survival determinants in lung transplant patients with chronic allograft dysfunction. Transplantation. 2011;92:703–708. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31822bf790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e65.Lease ED, Zaas DW. Complex bacterial infections pre- and posttransplant. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:234–242. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e66.Sengpiel J, Fuehner T, Kugler C, et al. Use of telehealth technology for home spirometry after lung transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. Prog Transplant. 2010;20:310–317. doi: 10.1177/152692481002000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e67.Verleden GM, Vos R, De Vleeschauwer SI, et al. Obliterative bronchiolitis following lung transplantation: from old to new concepts? Transpl Int. 2009;22:771–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e68.Dauriat G, Mal H, Thabut G, et al. Lung transplantation for pulmonary langerhans’ cell histiocytosis: a multicenter analysis. Transplantation. 2006;81:746–750. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000200304.64613.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e69.Benden C, Rea F, Behr J, et al. Lung transplantation for lymphangioleiomyomatosis: the European experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e70.Hayes D, Jr, Galantowicz M, Yates AR, Preston TJ, Mansour HM. McConnell PI: Venovenous ECMO as a bridge to lung transplant and a protective strategy for subsequent primary graft dysfunction. J Artif Organs. 2013;16:382–385. doi: 10.1007/s10047-013-0699-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e71.Shah RJ, Diamond JM, Cantu E, et al. Latent class analysis identifies distinct phenotypes of primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. Chest. 2013;144:616–622. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e72.Diamond JM, Lee JC, Kawut SM, et al. Lung Transplant Outcomes Group. Clinical risk factors for primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:527–534. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1865OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e73.Dawson KL, Parulekar A, Seethamraju H. Treatment of hyperacute antibody-mediated lung allograft rejection with eculizumab. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:1325–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e74.Martinu T, Howell DN, Palmer SM. Acute cellular rejection and humoral sensitization in lung transplant recipients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:179–188. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e75.Weigt SS, DerHovanessian A, Wallace WD, Lynch JP, 3rd, Belperio JA. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: the Achilles’ heel of lung transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:336–351. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e76.Atanasova S, Hirschburger M, Jonigk D, et al. A relevant experimental model for human bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:1131–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e77.Suzuki H, Lasbury ME, Fan L, et al. Role of complement activation in obliterative bronchiolitis post-lung transplantation. J Immunol. 2013;191:4431–4439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e78.Sato M, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Saito T, et al. Time-dependent changes in the risk of death in pure bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.01.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e79.McManigle W, Pavlisko EN, Martinu T. Acute cellular and antibody-mediated allograft rejection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:320–335. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e80.Mihalek AD, Rosas IO, Padera RF, Jr, et al. Interstitial pneumonitis and the risk of chronic allograft rejection in lung transplant recipients. Chest. 2013;143:1430–1435. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e81.Verleden SE, Ruttens D, Vandermeulen E, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and restrictive allograft syndrome: do risk factors differ? Transplantation. 2013;95:1167–1172. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318286e076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e82.Martinu T, Chen DF, Palmer SM. Acute rejection and humoral sensitization in lung transplant recipients. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:54–65. doi: 10.1513/pats.200808-080GO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e83.Mason DP, Rajeswaran J, Li L, et al. Effect of changes in postoperative spirometry on survival after lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e84.Husain S, Resende MR, Rajwans N, et al. Elevated CXCL10 (IP-10) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid is associated with acute cellular rejection after human lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2013;97:90–97. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182a6ee0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e85.Krustrup D, Madsen CB, Iversen M, Engelholm L, Ryder LP, Andersen CB. The number of regulatory T cells in transbronchial lung allograft biopsies is related to FoxP3 mRNA levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and to the degree of acute cellular rejection. Transpl Immunol. 2013;29:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e86.Schlischewsky E, Fuehner T, Warnecke G, et al. Clinical significance of quantitative cytomegalovirus detection in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in lung transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2013;15:60–69. doi: 10.1111/tid.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e87.Sandrini A, Glanville AR. The controversial role of surveillance bronchoscopy after lung transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:494–498. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283300a3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e88.Thompson ML, Flynn JD, Clifford TM. Pharmacotherapy of lung transplantation: an overview. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26:5–13. doi: 10.1177/0897190012466048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e89.Sweet SC. Induction therapy in lung transplantation. Transpl Int. 2013;26:696–703. doi: 10.1111/tri.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e90.Paraskeva M, McLean C, Ellis S, et al. Acute fibrinoid organizing pneumonia after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:1360–1368. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1831OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e91.Shields RK, Clancy CJ, Minces LR, et al. Staphylococcus aureus infections in the early period after lung transplantation: epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e92.Verleden GM, Vos R, van Raemdonck D, Vanaudenaerde B. Pulmonary infection defense after lung transplantation: does airway ischemia play a role? Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15:568–571. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32833debd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e93.Prado e Silva M, Soto SF, Almeida FM, et al. Immunosuppression effects on airway mucociliary clearance: comparison between two triple therapies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e94.Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Ramotar K, et al. Infection with transmissible strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and clinical outcomes in adults with cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 2010;304:2145–2153. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e95.De Soyza A, Meachery G, Hester KL, et al. Lung transplantation for patients with cystic fibrosis and Burkholderia cepacia complex infection: a single-center experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1395–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e96.Hafkin J, Blumberg E. Infections in lung transplantation: new insights. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:483–487. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32833062f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e97.Nicolls MR, Zamora MR. Bronchial blood supply after lung transplantation without bronchial artery revascularization. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15:563–567. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32833deca9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e98.Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: thirtieth official adult heart transplant report-2013 focus theme: age. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:951–964. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e99.Ahmad S, Shlobin OA, Nathan SD. Pulmonary complications of lung transplantation. Chest. 2011;139:402–411. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e100.Shofer SL, Wahidi MM, Davis WA, et al. Significance of and risk factors for the development of central airway stenosis after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:383–389. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e101.Castleberry AW, Worni M, Kuchibhatla M, et al. A comparative analysis of bronchial stricture after lung transplantation in recipients with and without early acute rejection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1008–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.01.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e102.Barnard JB, Davies O, Curry P, et al. Size matching in lung transplantation: An evidence-based review. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:849–860. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e103.Eberlein M, Reed RM, Bolukbas S, et al. Lung size mismatch and survival after single and bilateral lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e104.Santacruz JF, Mehta AC. Airway complications and management after lung transplantation: ischemia, dehiscence, and stenosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:79–93. doi: 10.1513/pats.200808-094GO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]