Abstract

The effectiveness of infant-directed speech (IDS) produced by non-depressed mothers for promoting the acquisition of voice-face associations was investigated in 1-year-old children of depressed mothers in a conditioned-attention paradigm. Prior research suggested that infants of mothers with comparatively longer-duration depressive episodes exhibit poorer learning in response to non-depressed mothers’ IDS, but duration of depression was confounded with infant age. In the current study, 1-year-old infants of currently depressed mothers with relatively longer-duration depressive episodes (i.e., perinatal onset) showed significantly poorer learning than 1-year-olds of currently depressed mothers with relatively shorter duration depressive episodes (non-perinatal onset). This was true despite the fact that there were no measurable differences in the severity of depression, level of social functioning, or antidepressant medication use between the two groups. These findings add support to the hypothesis that there is an experience-based change in responsiveness to female IDS in infants of depressed mothers during the first year of life.

Keywords: Chronic depression, Infant-directed speech, Infant associative learning

Clinical depression occurs in about 10–15% of all new mothers (O’Hara, Neunaber, & Zekoski, 1984), and lasts on average about 6–7 months (Cooper & Murray, 1995; O’Hara, Stuart, Gorman, & Wenzel, 2000). Maternal depression has not only been linked to non-optimal mother–infant interactions (Field, 1994), but also to later elevated risk for insecure attachment (Teti, Gelfand, Messinger, & Isabella, 1995), socio-emotional dysregulation (Radke-Yarrow, 1998), delays in cognitive development (Cicchetti, Toth, & Rogosch, 2000; Murray, 1992), and later psychopathology (Hammen & Brennan, 2003). However, many of these effects are more pronounced, or are observed only when mothers suffer from relatively more chronic depression (Campbell & Cohn, 1997; Campbell, Cohn, & Meyers, 1995; Diego, Field, & Hernandez-Reif, 2005; Frankel & Harmon, 1996; Murray, 1992; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1999). The purpose of the current experiment was to study the effects of variations in the duration of maternal depression, without the confounding effects of variations in depression severity or infant age, on a basic form of learning in 1-year-old infants of currently depressed mothers.

An important source of caregiver stimulation is infant-directed speech (IDS), a distinctive speech register characterized primarily by exaggeration in prosodic cues and simplification of speech (Jacobsen, Boersma, Fields, & Olson, 1983; Snow, 1972). Normally, IDS is particularly effective at attracting and maintaining infant attention, modulating infant affect and arousal, and facilitating infant learning (Fernald, 1984). However, IDS produced by depressed mothers is lacking in extent of pitch modulation (Bettes, 1988; Kaplan, Bachorowski, Smoski, & Zinser, 2001; Zlochower & Cohn, 1996), and is less effective than IDS produced by non-depressed mothers at promoting basic learning in 4-month-old infants (Kaplan, Bachorowski, & Zarlengo-Strouse, 1999). Moreover, with longer exposure to a clinically depressed mother, an infant learning deficit that initially appears to be tied to the low perceptual and affective salience of IDS eventually extends even to IDS produced by a non-depressed mother, and infants whose mothers have longer postpartum durations of depression show poorer learning (Kaplan, Bachorowski, Smoski, & Hudenko, 2002; Kaplan, Dungan, & Zinser, 2004). But interpretation of these data is complicated by the fact that the duration of the mothers’ depression was confounded with infant age in those studies, and infant age itself correlated with infant learning. The current study addressed this confound by investigating the effects on 1-year-old infants’ learning of variations in the postpartum duration of maternal depression.

The experiments reported here employed a conditioned-attention paradigm as a model system with which to study infant associative learning. According to conditioned-attention theory, similarly to overt responses, attentional responses are maintained or increase when one stimulus, S1, reliably predicts another, S2 (Lubow, 1989; Lubow & Josman, 2006). As applied to 4-month-old human infants, when a 10-s tone reliably precedes and predicts the presentation of a socially relevant stimulus such as a picture of a smiling female face, the tone acquires the ability to increase looking at a subsequently presented novel checkerboard pattern (Kaplan, Fox, & Huckeby, 1992). However, following backward pairings or random presentations of tone and face, the tone has no effect on looking at the checkerboard. Furthermore, qualities of the signaling stimulus affect how well the sound-face association is learned. Four-month-old infants exhibit significant learning following forward (but not backward) pairings of an IDS segment and a face, but not following forward or backward pairings of an adult-directed speech (ADS) segment and a face (Kaplan, Jung, Ryther, & Zarlengo-Strouse, 1996), an effect that has been attributed to a relatively greater increase in infant state of arousal elicited by IDS (Kaplan, Zarlengo-Strouse, Kirk, & Angel, 1997).

It follows that IDS lacking in salience will be ineffective at increasing arousal and hence promoting learning. In support of this prediction Kaplan et al. (1999) found that IDS recorded from unfamiliar depressed mothers was less effective at promoting voice-face associative learning in 4-month-old infants of non-depressed mothers than was IDS recorded from unfamiliar non-depressed mothers. The extent to which infants learned associations between the voice and face was negatively correlated with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score of the mother who produced the speech sample, and also negatively correlated with the extent of F0 modulation (ΔF0) in the speech sample. In a follow-up study, 4-month-old infants of clinically depressed mothers similarly did not acquire associations when their own or an unfamiliar depressed mother’s IDS signaled a face, but showed significant learning when an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s IDS served as signal (Kaplan et al., 2002). This pattern of results suggested that learning failures were due to the low quality of ID stimulation, rather to an inability to learn.

However, Kaplan et al. (2004) found that 5- to 13-month-olds infants of more chronically depressed mothers not only failed to acquire associations in response to their own mothers’ IDS but, in contrast to 4-month-olds in prior experiments, on average also failed to acquire associations in response to IDS produced by unfamiliar non-depressed mothers. Moreover, the longer the infant’s own mother had been depressed in the postpartum period, the weaker the infant learning in response to the non-depressed mother’s IDS. This result was replicated in a second experiment in which 6- to 13-month-old infants of depressed mothers again did not learn in response to IDS produced by an unfamiliar non-depressed mother, but showed significant learning in response to IDS produced by an unfamiliar non-depressed father (Kaplan et al., 2004, Exp. 2). These findings suggested an acquired decrement in responding to a non-depressed mother’s IDS as a consequence of prolonged exposure to a depressed primary caregiver, a result that could not be attributed to low perceptual salience of the IDS or an infant’s prior learning that affectively flat IDS does not “go with” a smiling face. Instead, it suggested an experience-based change in infant responding to IDS. Importantly, the fact that older infants learned in response to male IDS indicated that they did not lack the capacity to acquire associations.

Unfortunately, the interpretation of the link between duration of maternal depression and infant learning in response to non-depressed mothers’ IDS was complicated by the fact that depression duration was confounded with infant age (Kaplan et al., 2004). It is possible that mothers who waited to participate in the study until their infants were older than 4 months of age may have been experiencing greater difficulty with depression or the transition to parenthood than mothers who volunteered to participate by 4 months postpartum. Under this view, poorer infant learning in more chronically depressed mothers might actually be attributable to greater severity of depression. Based on the hypothesis that depression chronicity was more important than depression diagnosis per se or severity of depression, Kaplan et al. (2004) predicted that 12-month-old infants of depressed mothers with comparatively later onset of depression would exhibit significant learning in response to an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s IDS, whereas 12-month-old infants of depressed mothers with depression onset in the perinatal period would not. This hypothesis was put to the test here.

1. Method

1.1. Participants

One hundred and fifty-four 1-year-old infants (74 girls and 80 boys, M = 365.1 days, SD = 31.2) and their mothers were recruited through a monthly advertisement in Colorado Parent, a local parenting magazine available for free at area markets and infant-oriented retail stores. The mean age of the mothers was 30.6 years (SD = 5.4), with a mean education level of 5.6 (SD = 1.4; where 5.0 = graduated college with a 2 year degree and 6.0 = graduated with a 4-year degree), a mean family income of 6.1 (SD = 2.5; where 6.0 = $31,000–$40,000 and 7.0 = $41,000–$50,000), and a mean of 1.9 children (SD = 1.0). Ninety-five of the mothers (61.7%) were White, 33 were Latina (21.4%), 15 were African-American (9.7%), 8 were Asian (5.2%), and 3 were Native American (1.9%).

1.2. Apparatus

Mothers sat in a barber’s chair and held infants on their laps during testing. Mothers wore headphones with masking music, and a visor that blocked their view of the projection screen but permitted them to view their infants. The height or the chair was adjusted such that the infant’s eyes were level with a 4-in square translucent Plexiglas projection screen that was embedded in a board. Located 1.9 cm to the infant’s left of the projection screen was an aperture through which a low-light video camera recorded the infant’s face. Two full-face views of the infant were available to independent observers in separate rooms on 48.3-cm video monitors. Auditory stimuli were presented to infants using a SONY TCM 5000EV tape player. To insure that looking at the projection screen was not an artifact of infants’ visual orienting toward the sound source, the loudspeaker was situated 10 cm below and 33.5 cm behind the infant’s head. The average distance from the infant’s head to the projection screen was approximately 42 cm. Two visual stimuli, a black-and-white slide of a smiling adult female face and a black-and-white 4 × 4 checkerboard pattern (checks subtended 3° of visual angle), were presented using two computer-controlled slide projectors outfitted with shutters.

1.3. Speech stimuli

Each infant was tested with one IDS exemplar randomly selected (without replacement) from a large pool of samples previously recorded from non-depressed mothers (each of these mothers had a BDI-II score <14 and was classified as non-depressed after a structured clinical interview). None of the infants in the current study was tested with her or his own mother’s IDS. These IDS segments had been recorded in the following manner: mothers were asked to talk to their infants as they would at home. Following 2 min, mothers were handed a stuffed toy gorilla and asked to interest their infant in it using the phrase “pet the gorilla.” Mothers were instructed to both “ask” and “tell” their infants to “pet the gorilla” to make sure that both declarative and interrogative utterances would be made. This phase of the recording lasted approximately 1 min. To construct a 10-s IDS segment with roughly the same linguistic content across mothers, the first two interrogative and the first declarative “pet the gorilla” utterances were edited out of the speech stream and repeated once (e.g., Will you pet the gorilla? Can you pet the gorilla? Pet the gorilla. Will you pet the gorilla? Can you pet the gorilla? Pet the gorilla.”). Averaged across IDS samples, each produced by a different non-depressed mother, the mean fundamental frequency range (ΔF0) was 137 Hz (SD = 55.6, range: 43–369 Hz).

1.4. Assessment of depressive symptoms

All mothers filled out the BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), a 21-item self-report instrument that is widely used for assessing the affective, cognitive, motivational, and physiological symptoms associated with depression. The BDI-II has significant correlations with psychiatric ratings in clinical samples (Steer, Ball, Ranieri, & Beck, 1997). In addition, mothers completed the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (Beck & Gable, 2002), a 35-item self-report questionnaire that solicits information on symptoms associated with postpartum depression including sleep disturbance, anxiety, emotional lability, mental confusion, loss of self, guilt/shame, and suicidal thoughts. It too has significant correlations with psychiatric ratings.

In addition, all mothers were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Diagnosis (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997). Clinical diagnoses were made by M.A.-level clinical psychologists or clinical psychology graduate students who had received extensive training on the SCID and DSM-IV diagnosis. They were supervised by a Ph.D.-level psychologist. Training involved coursework, video demonstrations, observation of the trainer by the student, and practice interviews. Interviews lasted about 1 h. Inter-rater reliability for diagnoses of Major Depression, calculated between the primary rater and a Ph.D.-level second rater yielded a kappa value of .84. Final diagnoses were based on the primary rater. Each mother received a DSM-IV Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score, a numerical estimate of the mother’s overall level of functioning in psychological, social, and occupational realms on a scale of 1–100. Lower score indicate greater impairment. In this paper the term “depressed” is used only to describe individuals diagnosed with a DSM-IV Axis-I depression-spectrum disorder.

Information concerning the severity and duration (estimated to the nearest half month) of the current depressive episode, and diagnosis descriptors “single episode” or “recurrent” were also obtained during these interviews. Although “chronic” depression can refer either to a relatively long duration of one continuous depressive episode or to several distinct recurrent episodes, we use the term here in the former sense. Most of the mothers in this study were diagnosed with “recurrent” depression, but the duration (and timing of onset) of the current depressive episode varied. None of these mothers had more than one distinct depressive episode in the 12 months since their infant was born. There is no agreement in the literature on the absolute duration of a depressive episode that makes it “chronic.” Some investigators use the term to refer to episodes longer than 6 months (Campbell & Cohn, 1997; Field, 1992; Kurstjens & Wolke, 2001), whereas others reserve the term for depression lasting 24 months or more (NICHD ECCRN, 1999).

For the purposes of data analysis, we categorized each depressed mother based on the timing/duration of her current depressive episode. Due to depression onset shortly before or after their child’s birth (“perinatal onset”), half of the depressed mothers were depressed in the immediate postpartum period – defined by the DSM-IV-TR as the first 4 weeks postpartum (APA, 2000). The mean postpartum duration of depression for these mothers at the time of infant testing was 11.5 months. The other half of the depressed mothers had depression onset beyond the first 4 weeks postpartum window (“non-perinatal” or “later” onset). In fact, no mother in this condition had her depression start before 4 months postpartum (mean postpartum duration of depression at the time of infant testing was 3.7 months). There is considerable controversy about whether there are qualitative differences between clinical depression in mothers with vs. without the DSM-IV “postpartum onset specifier” (Campbell & Cohn, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009; Whiffen, 1992). We take no position on this point. Rather, our specific hypothesis concerns a quantitative effect of depression duration on infant learning.

1.5. Procedure

Immediately after completion of informed consent forms and questionnaires, the infant conditioned-attention test was given. On conditioning trials, each infant first heard a 10-s “pet the gorilla” speech segment when the projection screen was uniformly illuminated. At the offset of the segment, the infant received a 10-s presentation of a black-and-white photographic slide of a smiling adult female face. A 10-s inter-stimulus interval (ISI) during which the projection screen was uniformly illuminated and only background noise was heard immediately followed the offset of the face. Infants received six speech segment-face pairings. Ten seconds after the offset of the sixth face, the post-conditioning test phase began. Infants received 4 10-s presentations of a 4 × 4 black-and-white checkerboard pattern (10-s ISIs). The speech segment from the pairing phase was presented simultaneously with the first and fourth checkerboards (Trials 7 & 10), whereas the second and third checkerboards (Trials 8 & 9) were presented without sound. Durations of infant looking at the projection screen during the 10-s speech segment, face, and checkerboard trials were recorded. Looking was signaled by 2 independent observers when the reflection of the visual stimulus was centered on the infant’s pupils. A second observer was present for all tests (mean inter-observer r = .92, SD = .06).

2. Results

2.1. Demographic and diagnostic information

A total of 153 mother–infant dyads were recruited to the study, but 18 infants of currently non-depressed mothers and 1 infant of a currently depressed mother failed to complete the infant learning test due to excessive fussiness. Table 1 shows demographic and diagnostic information for the remaining mothers (n = 134; 87.0% of the original sample). Eighteen mothers were diagnosed with a DSM-IV Axis-I depression-spectrum diagnosis (DEP); 14 were diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD; 12 recurrent and 2 single episode), and 4 were diagnosed with depressive disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS). As was discussed above, 9 of the 18 depressed mothers were categorized as having perinatal depression onset (6 MDD – all but one with recurrent depression – and 3 DDNOS) and 9 were categorized as having later-onset depression (i.e., onset after the 4 weeks postpartum; 8 MDD – all but one with recurrent depression – and 1 DDNOS). The onset of depression for two of the mothers in the perinatal-onset condition was shortly before birth, but all mothers in the perinatal-onset group were depressed for at least part of the infant’s first month and most of the infant’s first year of life.

Table 1.

Maternal demographic and diagnostic data.

| Variable | NDEP | FR | PR | DEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 79 | 19 | 18 | 18 |

| Age of mother (years) | 31.3 (5.0) | 29.7 (5.6) | 29.4 (6.6) | 30.2 (5.2) |

| Age of infant (days) | 365 (30.0) | 362 (39.1) | 358 (35.5) | 362 (30.6) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 51 (64.6%) | 13 (68.4%) | 7 (38.9%) | 8 (44.4%) |

| Latina | 16 (20.3%) | 3 (15.7%) | 5 (27.7%) | 6 (33.3%) |

| African-American | 7 (8.9%) | 2 (10.5%) | 3 (16.7%) | 4 (22.2%) |

| Asian | 4 (5.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Native-American | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Marital status | ||||

| married | 64 (81.0%) | 16 (84.2%) | 11 (61.1%) | 10 (55.6%) |

| unmarried | 15 (19.0%) | 3 (15.8%) | 7 (38.9%) | 8 (44.4%) |

| Mother’s education | 5.8 (1.5) | 5.9 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.3) | 5.0 (1.2) |

| Family income | 6.4 (2.3)a | 6.7 (1.6)a | 5.2 (2.9)b | 5.1 (2.7)b |

| Number of children | 1.9 (1.0)a | 1.5 (1.0)a | 1.8 (1.0)a | 2.4 (1.2)b |

| BDI score | 8.6 (7.2)a | 9.5 (7.5)a | 14.6 (6.6)b | 26.4 (9.2)c |

| PDSS score | 61.2 (20.0)a | 70.1 (25.5)a | 84.0 (18.0)b | 118.7 (22.9)c |

| GAF | 79.2 (6.8)a | 78.2 (4.5)a | 67.0 (6.8)b | 59.6 (7.6)c |

Based on infants who completed the infant learning test. Values with different subscripts differ significantly from one another, p = .05. For education: 4.0 = graduated high school; 5.0 = graduated from 2-year college, 6.0 = graduated from 4-year college. For income: 6.0 = $31,000–$40,000, 7.0 = $41,000–$50,000.

Seventy-nine mothers were diagnosed as non-depressed (NDEP). Nineteen mothers were diagnosed with an episode of depression starting at some point since the conception of the child that was now in full remission (FR), defined as the absence of significant symptoms or signs for at least the past 2 months. Eighteen mothers were diagnosed with an episode of depression starting at some point since the conception of the child that was now in partial remission (PR), defined as the presence of some significant symptoms, but not enough to reach the full DSM-IV criteria, or the absence of significant symptoms but for less than 2 months.

Table 1 shows that there were significant differences as a function of these 4 diagnostic categories in family income and number of children. Family income did not differ between NDEP and FR families, but was significantly lower in PR and DEP families (Newman–Keuls test, p = .05). DEP families also had significantly more children than those in the other 3 diagnostic groups.

Table 2 shows that there were no significant differences in demographic variables between depressed mothers diagnosed with perinatal vs. later onset. Importantly, there was no evidence of differences in the severity of depression (interviewer-based DSM-IV ratings; 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe), number of self-reported symptoms (BDI-II scores, PDSS scores) or degree of impairment in social and occupational functions (interviewer-based GAF ratings) between early and later onset depressed mothers. The mean duration of depression in mothers in the perinatal-onset condition was 11.5 months (SD = 1.1), whereas that in the later-onset condition was 3.7 months (SD = 2.4), F(1, 17) = 87.54, p = .0001.

Table 2.

Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of depressed mothers as a function of timing of depression onset.

| Variable | Perinatal onset | Later onset |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 30.7 (5.3) | 30.3 (5.4) |

| Infant age (days) | 355.8 (23.5) | 370.0 (35.4) |

| Maternal education | 5.7 (1.3) | 4.6 (1.2) |

| Infant gender (girls/boys) | 5/4 | 6/3 |

| Family income | 5.4 (2.2) | 4.4 (3.2) |

| % Married | 44 | 44 |

| % Ethnic minority | 44 | 67 |

| Number of children | 2.2 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.1) |

| Depression diagnosis | ||

| MDD | 6 | 7 |

| DDNOS | 3 | 2 |

| Depression severity | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.7) |

| Mean BDI-II score | 24.9 (8.0) | 27.6 (10.5) |

| Mean PDSS score | 114.1 (25.0) | 120.9 (21.5) |

| Duration of depression (mos) | 11.5 (1.1)a | 3.7 (2.4)b |

| Global assessment of functioning | 61.1 (5.2) | 57.1 (8.7) |

| Antidepressant medication | 5/9 | 4/9 |

Based on infants who completed the infant learning test. Values with different subscripts differ significantly from each other, p = .05.

2.2. Infant learning

Infant testers were not aware of any information related to maternal diagnosis at the time of testing. There were no significant demographic differences between the infants who did vs. did not complete the learning test.

2.3. Pairing phase

Prior studies using this paradigm have shown no differences in looking as a function of maternal depression diagnosis and no changes in looking during IDS segments or face presentations across the 6 pairing trials, most likely due to the fact that each type of stimulus elicited at least moderately high levels of looking from the first trial (Kaplan et al., 1999, 2002, 2004; Kaplan, Burgess, Sliter, & Moreno, 2009). In the current study, looking times in response to IDS and face stimuli were comparable between groups, and did not change differentially across pairing trials. For example, a repeated-measures ANOVA comparing responding by infants of currently depressed (DEP) and not currently depressed mothers (NDEP + FR + PR) across the six IDS signal presentations (projection screen uniformly illuminated) with Greenhouse-Geisser corrected degrees of freedom showed no effect of maternal diagnosis F(1, 127) = 1.99, p = .16, a marginally significant effect of trials, F(5, 601) = 2.21, p = .06, but a non-significant maternal diagnosis × trials interaction, F(5, 601) = 0.67, p = .64. The effect of trials was attributable to a quadratic trend in which looking in both groups increased from Trial 1 to Trial 3, and decreased thereafter, F(1, 127) = 6.56, p = .02. Similarly, there were no differences in looking during the 6 face presentations as a function of maternal diagnosis, with Greenhouse-Geisser corrected df, F(1, 127) = 1.14, p = .29, trials, F(5, 615) = 1.69, p = .14, or their interaction, F(5, 615) = 0.48.

Focusing on infants of depressed mothers, there were no pairing phase differences in looking during IDS segments as a function of perinatal vs. later onset, F(1, 14) = 0.61, trials, F(3, 38) = 0.97, or their interaction, F(3, 38) = 1.43, p = .26. Similarly, there were no differences in looking times during face presentations as a function of onset group, F(1, 14) = 0.04, trials, F(4, 56) = 1.36, p = .26, or their interaction, F(4, 56) = 2.01, p = .11.

2.4. Summation test phase

To further assess whether base rate responding was comparable for infants of depressed and non-depressed mothers, we compared mean looking at the checkerboard patterns on Trials 8 and 9, the two checkerboard presentations in the test phase during which no IDS stimulus was presented. Mean looking times during these trials did not differ as a function of current maternal diagnosis (not currently depressed: M = 5.2 s, SD = 2.98; currently depressed: M = 4.9 s, SD = 3.19, F(1, 126) = 0.60). Furthermore, among infants of currently depressed mothers, there were no differences in responding to the checkerboard alone based on whether the mother had an episode with perinatal or later onset, F(1, 15) = 1.28, p = .28.

For each infant a difference score, a summary measure of learning, was calculated by subtracting the looking on checkerboard alone test trials from that on checkerboard-plus-speech segment test trials. Values above zero indicate that the speech segment increased looking above baseline levels (“positive summation”). Prior research has shown that in standard control conditions (backward pairings, random presentations, and no signal in the pairing phase) there is no significant positive summation (Kaplan et al., 1992, 1996, 1997). This includes studies with infants of depressed mothers (Kaplan et al., 2004). Difference scores above zero are therefore consistent with the occurrence of associative learning.

Mean difference scores in response to an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s IDS for infants of NDEP, FR, PR, and DEP mothers were 1.17 s (SD = 2.2, n = 79), 0.26 s (SD = 2.90, n = 19), 0.90 s (SD = 2.34, n = 18), and 1.15 s (SD = 1.93, n = 18), respectively, a non-significant effect, F(3, 129) = 0.86. Mean difference scores were significantly above zero for infants in the NDEP group, t(78) = 4.68, p = .01, and the DEP group (perinatal and later-onset combined), t(17) = 2.55, p = .03, but not for infants in the FR, t(18) = 0.39, or PR, t(17) = 1.65, p >.05, conditions. Maternal education did not correlate with infant difference scores, r = −.08, p = .37.

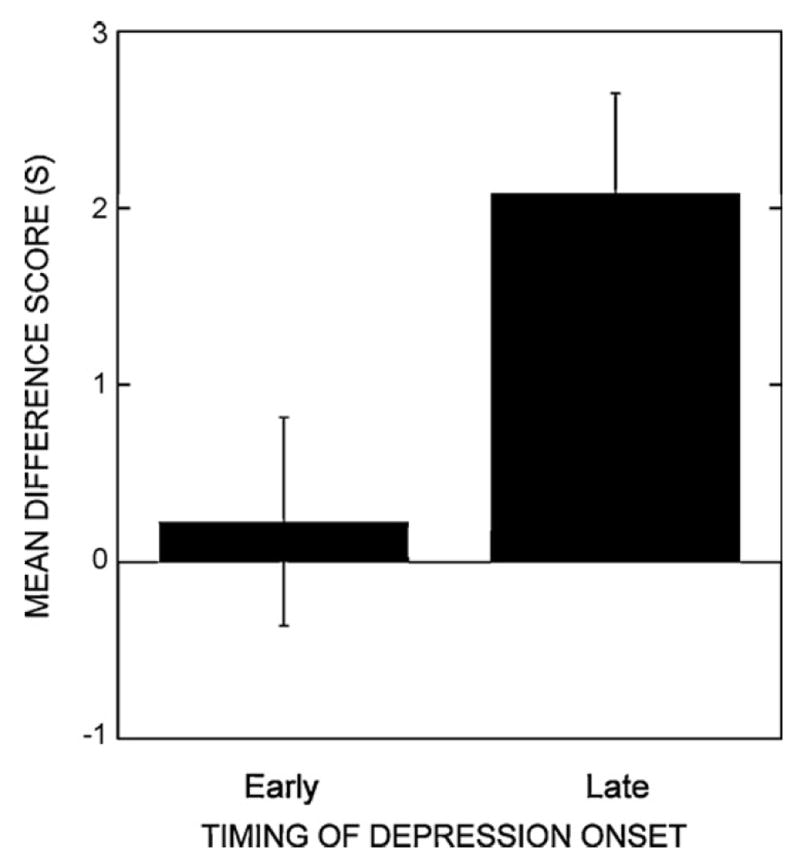

Despite the absence of an overall diagnostic group effect on infant difference scores, because of our a priori hypothesis that infant learning would differ in infants of currently depressed mothers as a function of the duration of maternal depression, we contrasted difference scores for infants of currently depressed mothers with perinatal onset (n = 9) and those of mothers with later onset (n = 9). Fig. 1 shows that there were significant differences, F(1, 16) = 5.17, p = .05, η2 = .244; a non-parametric test pointed to the same conclusion; Mann-Whitney U = 17, z = 2.08, p = .04). Mean difference scores were significantly above zero for infants of mothers with later-onset depression, t(9) = 3.69, p = .01, but not for infants of mothers with perinatal-onset depression, t(8) = 0.39. Difference scores for infants of depressed mothers with later onset were actually higher than those for infants of non-depressed mothers, but not significantly so, F(1, 86) = 1.20, p >.20.1

Fig. 1.

Mean difference scores in the post-conditioning test phase for groups of infants of depressed mothers with early depression onset vs. late depression onset (i.e., onset >4 months postpartum).

There was a marginally significant positive correlation between ΔF0 in the IDS speech samples and infant learning scores, r = .16, p = .07. However, an ANCOVA showed a significant effect of maternal depression duration category on infant learning even after ΔF0 had been taken into account, F(1, 15) = 8.85, p = .01, η2 = .371.

3. Discussion

Previous research using a conditioned-attention paradigm demonstrated that 4-month-old infants of depressed mothers exhibited significant voice-face associative learning in response to an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s IDS (Kaplan et al., 2002), but on average 5- to 13-month-old infants of more chronically depressed mothers did not, with poorer learning in infants of mothers with longer depressive episodes (Kaplan et al., 2004). Although these findings suggested a decreased responsiveness on the part of infants to IDS produced by an unfamiliar non-depressed mother as a function of the duration of their own mothers’ depressive episode, duration of depression and infant age were confounded. Here, with infant age held constant at approximately 1 year, infants of clinically depressed mothers with relatively short duration episodes (i.e., depression onset at least 4 weeks after birth, but in practice on average more than 8 months after birth) showed significantly better learning than infants of clinically depressed mothers with relatively long duration episodes (i.e., onset within 1 month before or after birth). This was true even after the extent of F0 modulation in the signaling IDS speech samples had been taken into account, and was not attributable to differences between mothers with shorter- vs. longer-duration depressive episodes in interviewer ratings of depression severity and global assessment of functioning, the number of self-reported symptoms of depression, or key demographic variables. Although these findings were obtained using small samples of mothers with perinatal- vs. later-onset depression, they are in agreement with re-analyzed data from 5- to 13-month-old infants of mothers with perinatal- vs. later-onset depression in the Kaplan et al. (2004) study, and bolster the conclusion from that study that infants of mothers with postpartum depression durations of greater than approximately 8 months do not learn well in response to unfamiliar non-depressed mothers’ IDS. Taken together with previous work, these results suggest that prolonged exposure to a depressed primary caregiver is responsible for a diminution in infant responding to this important type of stimulation.

These findings are consistent with other research in infant cognitive development indicating that maternal depression per se is often not associated with current or later problems in child development. Rather, the chronicity of depression appears to be more important in a number of developmental domains (Grace, Evidnar, & Stewart, 2003). For example, 15-month-old infants of mothers who were depressed throughout the first year of life showed lower cognitive development scores on the Bayley scales than infants of mothers with relatively brief depressive episodes during the first year (Cornish et al., 2005). Similarly, greater deficits in expressive language in 3-years olds were found in children of chronically depressed mothers (defined as 24-month duration of maternal depression) relative to children of mothers who had had a briefer duration of depression (NICHD ECCRN, 1999). Thus, comparatively longer-duration maternal depressive episodes are linked not only to deficits in one specific associative learning task, but also in more general cognitive and language development.

However, an alternative explanation of the current findings is that the timing of maternal depression mattered more than duration per se. Infants in the perinatal-onset condition may have exhibited poor learning not because of a quantitative difference attributable to greater duration or a relatively larger “dosage” of maternal depression, but rather because of qualitative differences between perinatal- and non-perinatal-onset depression, or depression in the immediate postpartum period vs. depression that started sometime later. In other words, maternal depression in the immediate postpartum period may have more pervasive or more severe effects than maternal depression that starts a month or more after birth. Along the lines of a sensitive period account, infants may be more vulnerable to maternal depression earlier than later in the first year of their lives, possibly because patterns of mother–infant interaction are being established then, and the infant’s ability to cope with the disruptions in maternal behavior that accompany a depressive episode may be greater after a foundation of adequate dyadic interactions has already been laid. As was mentioned above, although the distinction is controversial (Whiffen, 1992), the DSM-IV-TR differentiates between maternal depression with a “postpartum onset specifier” (i.e., onset within 4 weeks of birth) and that without the specifier.

Although the hypothesis that effects of longer-duration depressive episodes can be accounted for by the timing of depression onset was not supported by previous work in this paradigm showing that 4-month-old infants of depressed mothers exhibit significant learning in response to IDS produced by unfamiliar non-depressed mothers, it remains possible that maternal depression in, for example, the first 8 months of the infant’s life followed by remission from depression, would produce similar results to maternal depression for the entire first year. It is also possible that although infants of depressed mothers respond to non-depressed mothers’ IDS at 4 months, events have been set in motion for them that will eventually lead to poor responding at 12 months. Relevant to this discussion is our finding that, although infants of mothers in the FR and PR groups did not differ significantly from those in the NDEP and DEP groups in learning scores, in neither the FR nor PR groups did learning scores differ significantly from zero. Unfortunately, the durations of depression and remission-from-depression were highly variable in the FR and PR conditions.

The issue of maternal depression timing has also been raised by research showing that maternal depression in the prenatal period has been linked to lower Brazelton NBAS scores on subscales for alertness and orientation to a face/voice stimulus (Hernandez-Reif, Field, Diego, & Ruddock, 2006), and later child emotional problems (O’Connor, Heron, Golding, & Glover, 2003). However, only 2 depressed mothers in our early-onset condition had prenatal depression onset (both shortly before birth), suggesting that the main findings of our study are not attributable to prenatal factors. Mothers’ use of antidepressant medication during pregnancy and nursing may also have adverse effects on infants, although the data on this question are limited (Gitlin, 2009; Goodman & Brand, 2009). In the current study, roughly equal proportions of mothers in the two duration groups were taking antidepressant medication.

The current findings add to other lines of evidence in support of an experience-based learning deficit in response to maternal IDS in infants of depressed mothers. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that blind ratings of a mother’s sensitivity using the Emotional Availability Scales (Biringen et al., 2000), coded from a separate mother–infant play interaction, significantly predicted learning in 5- to 13-month-old infants in response to their own mothers’ IDS, even after demographic risk factors, extent of F0 modulation, antidepressant medication use, and maternal depression had been taken into account (Kaplan et al., 2009). In addition, 6- to 13-month-old infants of depressed mothers showed better learning in response to male IDS than did age-matched infants of non-depressed mothers (Kaplan et al., 2004), and 1-year-olds’ learning in response to an unfamiliar father’s IDS was significantly stronger in infants of married than unmarried parents, and stronger in infants of depressed married mothers than non-depressed married mothers (Kaplan, Danko, & Diaz, 2010). It appears that the social significance of the speaker conditions how effectively IDS promotes infant learning in this paradigm.

What is it about experience with a depressed primary caregiver that might explain these effects? The most influential models of effects of postpartum depression on child development posit that experience with a withdrawn, inattentive, emotionally unavailable primary caregiver leads initially to infant agitation and later to infant withdrawal (Field, 1994; Tarabulsky, Tessier, & Kappas, 1996; Tronick & Gianino, 1986). It is likely that as a consequence of this process, infants of mothers who are low in sensitivity and contingent responding learn that their mothers’ behavior and stimulation, including IDS, do not predict reinforcing events or satisfying interactions. If so, then contemporary models of basic learning processes predict that infants of chronically depressed mothers should eventually “tune-out” maternal stimulation (“learned irrelevance,” Linden, Savage, & Overmeier, 1997; Lubow, 1989; Lubow & Josman, 2006). If this learning is eventually generalized to similar stimuli such as other female voices, but not to dissimilar stimuli such as male voices, then infants of chronically depressed mothers would be expected to respond to non-depressed mothers’ IDS early in the first year of life, but to respond less as the mother’s depression wears on. Such turning away from a depressed mother may happen in tandem with turning toward a non-depressed father or other caregiver.

There were some limitations to the current study. First, the number of depressed mothers in the perinatal- and later-onset groups was small. This raises the question of whether these findings would replicate with larger samples. However, the reanalyzed data from the Kaplan et al. (2004) study showed a similar effect of depression duration in samples matched for age (see footnote 1). Furthermore, the current findings on effects of duration of depression holding infant age constant nicely compliment those on effects of duration when age (but not timing of onset) varied concurrently (Kaplan et al., 2004). Second, SCID-based estimates of the durations of maternal depressive episodes obtained at 12 months were retrospective rather than being based on assessments throughout the first year of life. On the other hand, SCID interviewers were highly trained and had the advantage over self-reports that they could ask follow-up questions about past symptoms and functioning, and pinpoint the timing of events by calibrating them to salient dates or milestones in the year (“timeline follow-back” method). Third, there were few mothers who were depressed at any point during pregnancy, and none who were depressed throughout pregnancy. Given the profound effects that prenatal depression can have on infant physiology, behavior, and health (Goodman & Brand, 2009), the lack of prenatally depressed mothers in this study may limit the generality of its conclusions. Fourth, there were no follow-ups to determine if depression chronicity influenced other aspects of cognitive functioning beyond voice-face associative learning.

Another potential area for concern is whether the conditioned-attention paradigm employed here is as age-appropriate for 12-month-olds as it was for younger infants in prior studies. As others have noted (Fernald, 1984), the functions for infants of the prosodic and intonational cues in IDS change throughout the first year of life, from initially serving as unconditioned stimuli to bring about changes in infant state and attention, to eventually aiding infants in linguistic processing (Jusczyk, 2000). Furthermore, the sequential presentation of IDS and static, achromatic faces, all independent of the infant’s behavior, is quite different from the synchronized voices and faces and socially contingent manner in which infants experience IDS during the course of normal parent-infant interactions. Indeed, our own research suggests that IDS produced by a sensitive, contingent interaction partner is more effective in this paradigm, and others have shown that rudimentary speech perception, learning, and production are aided by live adult interaction partners and contingent delivery of feedback (Goldstein & Schwade, 2008; Kuhl, Tsao, & Liu, 2003; Roseberry, Hirsh-Pasek, Parish-Moris, & Golinkoff, 2009).

Age-appropriateness is a legitimate concern, but it cannot explain the pattern of findings we obtained. The reasoning behind selecting a conditioned-attention paradigm for study was that previous work suggested a linear decline over the first year of life in the learning-promoting properties of non-depressed mothers’ IDS for 5- to 13-month-old infants of depressed mothers, but not for age-matched controls. We focused on 1-year-olds to maximize this apparent effect of exposure duration, holding all other aspects of the paradigm constant (except for having infants seated on the mother’s lap, rather than in a car seat as had been done in studies with younger infants). An unintended consequence of our effort to rigorously titrate effects of infant age and duration of depression may have been a reduction in the ecological validity of this paradigm for 1-year-olds. However, we note that (a) learning outcomes and attrition rates for groups of 1-year-old infants of non-depressed mothers have been essentially the same as we have found for 4-month-olds (Kaplan et al., 1999, 2002) and 5- to 13-month-olds of non-depressed mothers (Kaplan et al., 2004), (b) there were no differences in the degree of ecological validity experienced by the perinatal- and later-onset depression groups, and (c) while it is obviously true that older infants have greater capabilities than younger infants, there is no reason to think that they have lost the ability to detect stimulus–stimulus regularities when they are made particularly salient by the experimenter.

Despite these limitations, the current study provided evidence that relatively more prolonged exposure to a depressed primary caregiver affects responding to a kind of stimulation that normally is particularly effective at modulating infant state and promoting learning (see also Field et al., 1988), including, in the latter half of the first year, learning about speech stimuli (Thiessen, Hill, & Saffran, 2005). Although no explicit links can yet be shown between the kinds of learning failures we have reported and later cognitive or language development, others have found that children of mothers with chronic depression exhibit lags in cognitive development (Cornish et al., 2005) and vocabulary acquisition (NICHD ECCRN, 1999).

One possible implication of our findings is that the effectiveness of stimulation produced by non-depressed female interaction partners, childcare providers, and therapists may be reduced for infants of chronically depressed mothers, thereby potentially hindering efforts to improve infant functioning through enrichment programs or therapeutic interventions. It will be of interest to determine whether and how quickly infants of chronically depressed mothers exhibit recovery of responding to non-depressed female IDS as a consequence of sensitive and contingent interactions with a non-depressed female interaction partner or therapist.

Footnotes

This finding prompted a re-analysis of the data from Kaplan et al. (2004). In two experiments, there were 23 infants of currently depressed mothers, with a mean age of 242 days (range 175–400 days). Of these 23 infants, 5 had mothers with depression onset after the first 4 weeks postpartum (mean time of onset = 3.0 months postpartum, SD = 0.7; mean infant age = 242.2 days, SD = 42.1). These 5 were matched to 5 infants of depressed mothers with perinatal onset (mean time of onset 0.2 months, SD = 0.4; mean infant age = 244.2 days, SD = 42.6), and mean difference scores were compared. The ages and mean difference scores for the 5 infants of depressed mothers with perinatal onset were: 175 days, 1.80 s; 232 days, 0.85 s; 244 days, −1.70 s; 265 days, −0.30 s; 305 days, −3.40 s. The ages and mean difference scores for the matched infants of mothers with later onset were: 176 days, 2.80 s; 232 days, 4.10 s; 236 days, 4.20 s; 262 days, 1.05 s; 305 days, 1.70 s. For each matched pair, the mean difference score for the infant of the mother with perinatal onset was lower than that for the infant of the mother with later onset, sign test, z = 1.79, p = .05. These findings, not previously reported, bolster the current limited data.

References

- American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT, Gable RK. Postpartum depression screening scale. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II: 2nd edition manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bettes B. Maternal depression and motherese: Temporal and intonational features. Child Development. 1988;59:1089–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biringen Z, Robinson J, Emde R. Appendix B: The emotional availability scales. Attachment & Human Development. (3) 2000;2:256–270. doi: 10.1080/14616730050085617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Cohn JF. Prevalence and correlates of postpartum depression in first-time mothers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:594–599. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Cohn JF. The timing and chronicity of postpartum depression: Implications for infant development. In: Murray L, Cooper P, editors. Postpartum depression and child development. New York: Guilford; 1997. pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Cohn JF, Meyers TA. Depression in first-time mothers: Mother–infant interactions and depression chronicity. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL. The efficacy of toddler-parent psychotherapy for fostering cognitive development in offspring of depressed mothers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:135–148. doi: 10.1023/a:1005118713814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P, Murray L. Course and recurrence of postnatal depression: Evidence for the specificity of the diagnostic concept. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;166:191–195. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish AM, McMahon CA, Ungerer JA, Barnett B, Kowalenko N, Tennant C. Postnatal depression and infant cognitive and motor development in the second postnatal year: The impact of depression chronicity and infant gender. Infant Behavior & Development. 2005;28:407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M. Prepartum, postpartum, and chronic effects on neonatal behavior. Infant Behavior & Development. 2005;28:155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A. The perceptual and affective salience of mothers’ speech to infants. In: Feagans L, Garvey C, Golinkoff R, editors. The origins and growth of communication. NJ: Ablex; 1984. pp. 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Field T. Infants of depressed mothers. Development & Psychopathology. 1992;4:49–66. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T. The effects of mother’s physical and emotional unavailability on emotion regulation. In: Fox N, editor. Monographs of the society for research in child development. 1994. pp. 209–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Healy B, Goldstein S, Perry S, Bendell D, Schanberg S, Zimmerman EA, Kuhn C. Infants of depressed mothers show “depressed” behavior even with nondepressed adults. Child Development. 1988;59:1569–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders Clinician version (SCID–CV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel KA, Harmon RJ. Depressed mothers: They don’t always look as bad as they feel. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:289–298. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ. Pharmacotherapy and other somatic treatments for depression. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CH, editors. Handbook of depression. 2. Vol. 59. New York: The Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 554–585. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein MH, Schwade JA. Social feedback to infants’ babbling facilitates rapid phonological learning. Psychological Science. 2008;19:515–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Brand SR. Depression and early adverse experience. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CH, editors. Handbook of depression. 2. New York: The Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 249–274. [Google Scholar]

- Grace SL, Evidnar A, Stewart DE. The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: A review and critical analysis of the literature. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2003;6:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA. Severity, chronicity, and timing of maternal depression and risk for adolescent offspring diagnoses in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:253–258. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Reif M, Field TF, Diego MA, Ruddock M. Greater arousal and less attentiveness to face/voice stimuli by neonates of depressed mothers on the brazelton neonatal behavioral assessment scale. Infant Behavior & Development. 2006;29:594–598. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen J, Boersma D, Fields R, Olson K. Paralinguistic features of adult speech to infants and small children. Child Development. 1983;54:436–442. [Google Scholar]

- Jusczyk PW. The discovery of spoken language. MIT Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Fox KB, Huckeby ER. Faces as reinforcers: Effects of pairing condition and facial expression. Developmental Psychobiology. 1992;25:299–312. doi: 10.1002/dev.420250407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan P, Jung PC, Ryther JS, Zarlengo-Strouse P. Infant-directed versus adult-directed speech as signals for faces. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:880–891. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Zarlengo-Strouse P, Kirk LS, Angel CL. Selective and nonselective associations between speech segments and faces in human infants. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:990–999. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Bachorowski JA, Zarlengo-Strouse P. Child-directed speech produced by mothers with symptoms of depression fails to promote associative learning in four-month old infants. Child Development. 1999;70:560–570. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Bachorowski J-A, Smoski MJ, Zinser MC. Role of clinical diagnosis and medication use in effects of maternal depression on infant-directed speech. Infancy. 2001;2:537–548. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0204_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Bachorowski J-A, Smoski MJ, Hudenko WJ. Infants of depressed mothers, although competent learners, fail to acquire associations in response to their own mothers’ infant-directed speech. Psychological Science. 2002;13:268–271. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Dungan JK, Zinser MC. Infants of chronically depressed mothers learn in response to male, but not female, infant-directed speech. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:140–148. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Burgess AP, Sliter JK, Moreno AJ. Maternal sensitivity and the learning-promoting effects of depressed and non-depressed mothers’ infant-directed speech. Infancy. 2009;14:143–161. doi: 10.1080/15250000802706924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Danko CM, Diaz A. A privileged status for male infant-directed speech in infants of depressed mothers? Role of father involvement? Infancy. 2010;15:151–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2009.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK, Tsao H-M, Liu F-M. Foreign-language experience in infancy: Effects of short-term exposure and social interaction on phonetic learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003:9096–9101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1532872100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurstjens S, Wolke D. Effects of maternal depression on cognitive development of children over the first 7 years of life. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2001;42:623–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden DR, Savage LM, Overmeier JB. General learned irrelevance: A Pavlovian analog to learned helplessness. Learning & Motivation. 1997;28:230–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lubow R. Latent inhibition and conditioned attention theory. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lubow RE, Josman ZE. Latent inhibition deficits in hyperactive children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;34:959–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. The impact of postnatal depression on infant development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:543–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child functioning at 36 months. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1297–1310. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM. Gender differences in depression. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. 2. Vol. 100. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 386–404. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, Glover V. Maternal antenatal anxiety and behavioural/emotional problems in children: A test of a programming hypothesis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1025–1036. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Neunaber DJ, Zekoski EM. Prospective study of postpartum depression: Prevalence, course, and predictive factors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1984;93:158–171. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Wenzel A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:1039–1045. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke-Yarrow M. Children of depressed mothers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Roseberry S, Hirsh-Pasek K, Parish-Moris J, Golinkoff RM. Live action: Can young children learn verbs from video? Child Development. 2009;80:1360–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow CE. Mothers’ speech to children learning language. Child Development. 1972;43:549–565. [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF, Beck AT. Further evidence for the construct validity of the beck depression inventory-II with psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatric Reports. 1997;80:443–446. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarabulsky GM, Tessier R, Kappas A. Contingency detection and the contingent organization of behavior in interactions: Implications for socioemotional development in infancy. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:25–41. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Gelfand D, Messinger D, Isabella R. Maternal depression and the quality of early attachment: An examination of infants, preschoolers, and their mothers. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:364–376. [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen ED, Hill EA, Saffran JR. Infant-directed speech facilitates word segmentation. Infancy. 2005;1:53–71. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0701_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronick EZ, Gianino AF. The transmission of maternal disturbance to the infant. In: Tronick EZ, Fields T, editors. Maternal depression and infant disturbance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1986. pp. 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen V. Is postpartum depression a distinct diagnosis? Clinical Psychology Review. 1992;12:485–508. [Google Scholar]

- Zlochower AJ, Cohn JF. Vocal timing in face-to-face interaction in clinically depressed and non-depressed mothers. Infant Behavior & Development. 1996;19:371–374. [Google Scholar]