Abstract

Background

Use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to prevent HIV transmission has received substantial attention following a recent trial demonstrating efficacy of ART to reduce HIV transmission in HIV-discordant couples.

Objective

To assess practices and attitudes of HIV clinicians regarding early initiation of ART for treatment and prevention of HIV at sites participating in the HPTN 065 study.

Design

Cross-sectional internet-based survey.

Methods

ART-prescribing clinicians (n=165 physicians, nurse-practitioners, physician assistants) at 38 HIV care sites in Bronx, NY and Washington, DC completed a brief anonymous internet survey, prior to any participation in the HPTN 065 study. Analyses included associations between clinician characteristics and willingness to prescribe ART for prevention.

Results

Almost all respondents (95%), of whom 59% were female, 66% white and 77% HIV specialists, “strongly agreed/agreed” that early ART can decrease HIV transmission. Fifty-six percent currently recommend ART initiation for HIV-infected patients with CD4+ count ≤500 cells/mm3, and 14 percent indicated that they initiate ART irrespective of CD4+ count. Most (75%) indicated that they would consider initiating ART earlier than otherwise indicated for patients in HIV-discordant sexual partnerships, and 40% would do so if a patient was having unprotected sex with a partner of unknown HIV status. There were no significant differences by age, gender, or clinician type in likelihood of initiating ART for reasons including HIV transmission prevention to sexual partners.

Conclusions

This sample of US clinicians indicated support for early ART initiation to prevent HIV transmission, especially for situations where such transmission would be more likely to occur.

Keywords: HIV prevention, early antiretroviral therapy, test and treat, clinician survey

Introduction

Recently the HIV Prevention Trials Network [HPTN] 052 Study found that earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) among HIV-infected adults (at CD4+ cell count 350-550 cells/mm3 versus 200-250 cells/mm3) was associated with a 96 percent decrease in HIV-1 transmission to sex partners [1]. This finding, supported by ecological and observational studies [2-5] and a meta-analysis [6] confirming association of ART with decreased HIV transmission within serodiscordant couples [7], has further stimulated interest in use of ART as a population-level prevention strategy [8]. We conducted a survey for ART-prescribing clinicians prior to any participation in the HPTN 065 (‘Test and Linkage to Care Plus Treat’, or TLC-Plus) study in the Bronx, NY and Washington, DC to assess current practices for recommending ART to patients and attitudes concerning early ART initiation to prevent HIV transmission. The survey was conducted before release of HPTN 052 results and 2012 DHHS treatment guidelines recommending ART for those at risk of transmitting HIV to sexual partners.1

Methods

Study participants

The clinician survey was conducted as part of but prior to initiation of the HPTN 065 study,2 the main purpose of which is to evaluate the feasibility of community-level expanded testing, linkage to care and adherence to ART as a strategy for HIV prevention in the Bronx, NY and Washington, DC [9]. HPTN 065 does not include early initiation of ART as an intervention.

ART-prescribing clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) at participating HIV care sites completed a secure internet-based survey (Illume software, DatStat, Inc., Seattle Washington) assessing attitudes and practices regarding ART. The survey was conducted prior to any of these clinicians participating in any of the testing, link to care or adherence HPTN 065 study activities.

Between September 28, 2010 and May 2, 2011, an introductory email and up to four automated email reminders were sent over a three-week period.[10] Before beginning the survey, clinicians electronically agreed to participate; no personally identifying information was requested. Clinicians who completed the 29-item survey received a $35 electronic gift certificate.

Data analysis

Antiretroviral prescribing practices, prevention practices for HIV-infected patients, and willingness to prescribe ART for prevention were analyzed using chi-square tests for associations with clinician gender, age group (<35 or ≥ 35 years old), type (attending or resident physician, infectious disease or other physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant), and characteristics of the patient population (<50% vs. ≥50% men who have sex with men [MSM], or injecting drug users [IDU]). We defined clinicians as ‘willing to prescribe ART for prevention’ if they agreed or strongly agreed with statements about initiating ART earlier (i.e., irrespective of CD4+ count) for HIV-infected persons with discordant partners, for those having unprotected sex with someone of unknown HIV status, or for those engaging in high-risk behaviors (see Results). Items collected on 4-point Likert scales were dichotomized as: agree/strongly agree versus disagree/strongly disagree.

Results

A total of 174/288 (60.4%) clinicians took the survey, 94/177 (53%) from the Bronx and 80/111 (72%) from Washington, DC. Nine/288 clinicians clicked on the email link but did not respond to any questions.

Responding clinicians (n=165) had a mean age of 46.1 years (SD± 10.2), 59.4% were female and two-thirds were white. Clinicians practiced in public (44.8%) and private clinics (22.4%) serving patients whose care was funded largely by Medicaid (mean of 58% Medicaid coverage). Of responding clinicians, 32.1% indicated their role as primary care physicians, and 29.5% as specialists, with 10.9% nurse practitioners and 13.3% physician assistants. Clinicians provided care for HIV-infected patients for a median of 13 years (interquartile range 14) and for a median of 95 HIV-infected patients (interquartile range 145), Table 1. Two-thirds of patients were male (68.6%), 25 percent were IDU and 33 percent were MSM. More than half of the patients were African American (mean 57.8%) and 35 percent were Latino. For 85 percent of clinicians, at least three-quarters of their patients were already receiving ART; six percent reported all of their patients were on ART.

Table 1. Characteristics, practices and attitudes about antiretroviral therapy and HIV transmission risk among HIV clinicians in 2 US cities*, HPTN 065 TLC-Plus Study, 2011.

| Question | Number (%), N=165 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of HIV patients under direct care | ||

| Mean number (SD) | 128.2 (135.8) | |

| Minimum, Maximum | 0, 800 | |

| Percentage of HIV patients currently on ART | ||

| Mean percentage (SD) | 83.0 (11.1) | |

| Minimum, Maximum | 30, 100 | |

| Never | 0/165 (0.0) | |

| How often ask about sexual partners' HIV status | ||

| Always | 61/165 (37.0) | |

| Often | 67/165 (40.6) | |

| Occasionally | 25/165 (15.2) | |

| Rarely | 8/165 (4.8) | |

| Never | 0/165 (0.0) | |

| How often ask about use of condoms | ||

| Always | 95 (57.6) | |

| Often | 48 (29.1) | |

| Occasionally | 16 (9.7) | |

| Rarely | 2 (1.2) | |

| Never | 0 (0.0) | |

| Factors to initiate ART earlier than would otherwise | ||

| High viral load (>100,000 copies/mm3) | 129 (78.2) | |

| Rapidly declining CD4+ (>100 cells/mm3/year) | 155 (93.9) | |

| Patient in HIV discordant sexual partnership | 124 (75.2) | |

| Patient has unprotected sex with partner(s) of unknown HIV status | 66 (40.0) | |

| Other | 105 (63.6) | |

| ‘Early initiation of ART can slow spread of HIV in a community by making patients less infectious to others’ | ||

| Strongly agree | 107 (64.8) | |

| Agree | 49 (29.7) | |

| Disagree | 4 (2.4) | |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0.0) | |

| ‘I am concerned that a patient will develop a resistant virus if ART is initiated too early’ | ||

| Strongly agree | 7 (4.2) | |

| Agree | 65 (39.4) | |

| Disagree | 67 (40.6) | |

| Strongly disagree | 21 (12.7) | |

| ‘If I start ART early in a patient with high risk sexual or other behaviors he or she may transmit resistant virus to his or her partners’ | ||

| Strongly agree | 2 (1.2) | |

| Agree | 47 (28.5) | |

| Disagree | 90 (54.5) | |

| Strongly disagree | 21 (12.7) | |

| ‘ I am concerned that a patient will develop side effects, toxicity or long term complications if ART is initiated too early’ | ||

| Strongly agree | 7 (4.2) | |

| Agree | 73 (44.2) | |

| Disagree | 71 (43.0) | |

| Strongly disagree | 9 (5.5) | |

| ‘ I take into account my patient's sexual and other HIV transmission behavior when I recommend ART’ | ||

| Strongly agree | 38 (23.0) | |

| Agree | 95 (57.6) | |

| Disagree | 25 (15.2) | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 (1.2) | |

| ‘If a patient tells me that he or she is engaging in high risk behaviors, I am more likely to recommend initiating ART, irrespective of their CD4+ count’ | ||

| Strongly agree | 38 (23.0) | |

| Agree | 79 (47.9) | |

| Disagree | 41 (24.8) | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 (1.2) | |

| “I tend to defer ART if a patient is not sure whether he or she is ready to initiate it” | % strongly agree or agree | 151 (91.5) |

| Before I recommend initiating ART, patients need to: | % strongly agree or agree | |

| Have their depression treated | 60 (36.4) | |

| Be in recovery from alcohol/illicit drugs | 45 (27.0) | |

| Tend to defer ART until CD4+ count < 350: | % strongly agree or agree | |

| If patient unable to pay for ART | 13 (7.9) | |

| Because ART monitoring requires more staff | 5 (3.0) | |

| Because limited pay for ART/HIV care in setting | 9 (5.4) | |

Responses to anonymous internet survey

Three-quarters of clinicians indicated they always (37.0%) or often (40.6%) asked their patients about the HIV status of sexual partners; 87 percent indicated they always (57.6%) or often (29.1%) asked about condom use; and two-thirds always (35.8%) or often (29.7%) asked patients about injection drug use (Table 1).

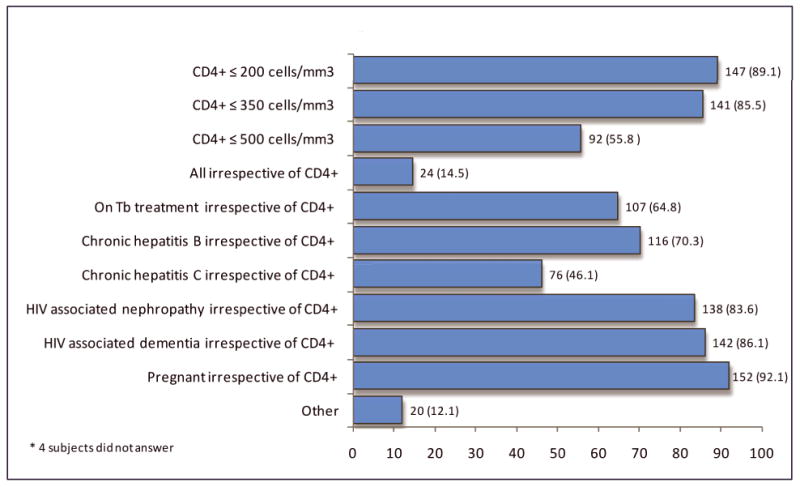

Most (94.5%) respondents indicated they strongly agreed or agreed “early initiation of ART can slow the spread of HIV in a community by making patients less infectious to others.” A small proportion (14.5%) indicated a current clinical practice of prescribing ART at any CD4+ cell count (Figure 1). Around half (55.8%) indicated they currently recommend “ART be initiated in any circumstance for HIV-infected patients with CD4+ cell counts of ≤500 cells/mm3”. The majority of respondents initiated ART for the patient's own health and based on the individual's readiness to take ART (92%). A minority of clinicians viewed untreated depression (36.4%), active substance use (27%), or lack of ability to pay for ART (7.9%) as impediments to ART initiation. While 53.3 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed they would have concern about patients developing HIV resistance or toxicity (48.5%) as a consequence of early ART initiation, 29.7 percent expressed concern about risk of transmission of resistant HIV with early initiation of ART in patients with high-risk behaviors.

Figure 1. Scenarios in which HIV clinicians would recommend ART initiation, N=165*.

HIV clinician responses to internet survey assessing “Scenarios in which you would recommend initiating antiretroviral therapy in any circumstance”, the HPTN 065 (TLC-Plus) Study, 2011.

Respondents initiated ART in a mean of 26 patients in the previous year (SD 50.3, range 0 to 500). Among 66 clinicians who initiated ART for patients in the prior year “with the main goal of making it less likely that they would pass on HIV to their partners,” this was done in a mean of 11.4 patients (SD 26.2, range 1 to 200). Seventy-nine percent strongly agreed or agreed they are more likely to recommend initiating ART, irrespective of patient CD4+ cell count, if a patient discloses high-risk behaviors, and 75 percent indicated they would do so if a patient is in a discordant sexual relationship.

Willingness to prescribe ART for preventing HIV transmission did not significantly differ by clinician characteristics including age, clinician type, gender, or patient population (data not shown).

Discussion

This survey of HIV clinicians in two US cities found most clinicians believed that ART can reduce HIV transmission, even before the results of HPTN 052 demonstrated ART to be effective for this purpose, and before 2012 treatment guideline changes recommending ART for patients at risk for HIV transmission. Thus, these experienced clinicians' willingness to initiate ART earlier appear congruent with public health guidance that more liberal ART use is appropriate. However, only one in seven currently prescribe ART for all their patients. These findings are germane because, despite substantial efforts to stop the US HIV epidemic [11], an estimated 50,000 new infections occur annually [12]. To have a significant impact on the HIV epidemic, ART will need to be prescribed appropriately by clinicians and taken consistently by HIV-infected individuals [13] in order to maximize individual health benefits and to reduce infectivity below detectable viral load levels [14]. It is therefore essential to understand clinician and patient practices and attitudes regarding ART.

Receipt of ART necessitates engagement in ongoing care, yet a recent meta-analysis found that only 59 percent of newly-diagnosed patients in the US remained in care for multiple visits [15]. The challenge of retaining patients in care and ensuring lifelong pill-taking adherence may create ambivalence in clinicians about initiating ART early for reducing HIV transmission to others. This ambivalence may be compounded by concerns about side effects, development of resistance, and other complications [16]. Our study corroborates this concern among approximately half of clinicians surveyed. Uncertainties regarding benefit/risk of early ART [1, 17-19] also may be reflected in the ambivalence among clinicians we surveyed. There remains an inherent tension in prescribing ART to individuals for a population-benefit, when the risk-benefit profiles of multidecades-long treatment are not yet available. Nonetheless there is emerging evidence that ART initiation at higher CD4+ counts may have individual benefit [20].

Although the study sample was from only two US cities, clinicians surveyed had extensive, long term experience caring for HIV-infected patients. Hence their attitudes and practices, before the release of the HPTN 052 results, might be similar to those of other experienced urban clinicians in the US. Though our study sample did include ART-prescribing clinicians who identified themselves as primary care providers, we cannot speculate as to whether the treatment decisions and attitudes we found apply to primary care providers more broadly.

Many clinicians surveyed (71%) were more likely to recommend ART irrespective of CD4+ count for patients engaging in high risk behaviors, and for patients in discordant sexual partnerships (75%), and are thus in alignment with current 2012 treatment guidelines. However, there was much less support for prescribing ART for all HIV-infected patients irrespective of CD4+ cell count, such as patients with CD4+ cell count >500 cells/mm3, a population for which there is less evidence of clinical benefit (16). Fifty-six percent of clinicians recommended initiating ART at CD4+ count <500 cells/mm3. similar to the percentage of 2010 DHHS guideline panel members (55%) favoring a strong recommendation for starting ART at CD4+ cell count between 350 and 500 cells/mm3 [21].

Several knowledge gaps remain. The impediments to, and facilitators of, a prevention strategy based on early use of ART in patients with HIV need to be better understood [22, 23]. Mathematical modeling suggests that, without high levels of coverage, a ‘test and treat’ strategy could increase long-term costs due to entry and treatment of newly-infected patients without a proportional reduction in incidence [23]. Concern about behavioral disinhibition effects of ART as prevention remain if patients engage in less condom use leading to the possibility of increases risk for acquisition of sexually transmitted infections. There are alarming data to indicate that even with broad access to ART, an increase in STIs has been noted in some populations particularly MSM [24, 25]. While the March 2012 DHHS treatment guidelines recommend ART for patients with CD4+ >500, there is a paucity of definitive data on the benefits versus risks of earlier treatment for HIV-infected patients themselves. Despite these concerns, it is noteworthy that many of the clinicians surveyed already initiate ART for subset of patients at higher risk of transmitting HIV to sex partners.

There is enthusiasm, as well as some caveats, for the potential of a seek, test, treat and retain strategy to help stem the HIV epidemic in the US [26]. Our findings suggest that clinicians will need to continue to balance emerging information regarding efficacy of ART for prevention, with their duty to provide patients with interventions that have a favorable long term benefit to their own health. As more unidentified-HIV-infected individuals are identified and initiate ART (sooner or later), there will need to be clinician orientation and training. Our study findings provide some guidance as to some of the parameters that will be important to include in such efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank participating clinicians and site lead investigators as well as the study protocol team members.

Sponsorship: HPTN 065 is sponsored by:

NIAID and NIMH (Cooperative Agreements #UM1 AI068619; #UM1 AI068617)

National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID, NIH, or CDC.

Footnotes

See http://www.hptn.org/research_studies/hptn065.asp for full study description

References

- 1.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group The New England journal of medicine. 2000;342:921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das M, Chu PL, Santos GM, Scheer S, Vittinghoff E, McFarland W, et al. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R, Yip B, Wood E, Kerr T, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376:532–539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60936-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rieder P, Joos B, von Wyl V, Kuster H, Grube C, Leemann C, et al. HIV-1 transmission after cessation of early antiretroviral therapy among men having sex with men. AIDS. 2010;24:1177–1183. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328338e4de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attia S, Egger M, Muller M, Zwahlen M, Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:1397–1404. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b7dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granich R, Crowley S, Vitoria M, Smyth C, Kahn JG, Bennett R, et al. Highly active antiretroviral treatment as prevention of HIV transmission: review of scientific evidence and update. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:298–304. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a6c32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall GKWE-SBBDDH. TLC-Plus: Design and Implementation of a Community-focused HIV Prevention Study in the U.S.. National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, GA. 2011. p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. 3rd. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Thirty Years of HIV and AIDS: Future Challenges and Opportunities. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;154:766–771. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-11-201106070-00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006-2009. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Sadr WM, Affrunti M, Gamble T, Zerbe A. Antiretroviral therapy: a promising HIV prevention strategy? Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S116–121. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbca6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Cahn P, Montaner JS, Rizzardini G, Telenti A, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2010;304:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, Crepaz N. Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2010;24:2665–2678. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f4b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer KH, Venkatesh KK. Antiretroviral therapy as HIV prevention: status and prospects. American journal of public health. 2010;100:1867–1876. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, Merriman B, Saag MS, Justice AC, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360:1815–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray M, Logan R, Sterne JA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM, Sabin C, et al. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24:123–137. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283324283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne JA, May M, Costagliola D, de Wolf F, Phillips AN, Harris R, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60612-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Sadr WM, Coburn BJ, Blower S. Modeling the impact on the HIV epidemic of treating discordant couples with antiretrovirals to prevent transmission. AIDS. 2011;25:2295–2299. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834c4c22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Services DoHaH. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2011 Jan 10;:1–166. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cambiano V, Rodger AJ, Phillips AN. ‘Test-and-treat’: the end of the HIV epidemic? Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2011;24:19–26. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283422c8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodd PJ, Garnett GP, Hallett TB. Examining the promise of HIV elimination by ‘test and treat’ in hyperendemic settings. AIDS. 2010;24:729–735. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833433fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wandeler G, Gsponer T, Witteck A, Clerc O, Calmy A, Gunthard H, et al. HCV Incidence in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS): A Changing Epidemic. CROI 2012: 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Abstract #743. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, Battegay M, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1130–1139. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNairy ML, El-Sadr WM. The HIV Care Continuum: No Partial Credit Given. AIDS. 2012 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328355d67b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]