Abstract

Background

Obesity and HIV disproportionately affect minorities and have significant health risks, but few studies have examined disparities in weight change in HIV-seropositive (HIV+) cohorts.

Objective

To determine racial and health insurance disparities in significant weight gain in a predominately Hispanic HIV+ cohort.

Methods

Our observational cohort study of 1,214 non-underweight HIV+ adults from 2007-2010 had significant weight gain (≥3% annual BMI increase) as primary outcome. The secondary outcome was continuous BMI over time. A four-level race-ethnicity/insurance predictor reflected the interaction between race-ethnicity and insurance: insured white (non-Hispanic), uninsured white, insured minority (Hispanic or black), or uninsured minority. Logistic and mixed effects models adjusted for: baseline BMI; age; gender; household income; HIV transmission category; antiretroviral therapy type; CD4+ count; plasma HIV-1 RNA; observation months; and visit frequency.

Results

The cohort was 63% Hispanic and 14% black; 13.3% were insured white, 10.0% uninsured white, 40.9% insured minority, and 35.7% uninsured minority. At baseline, 37.5% were overweight, 22.1% obese. Median observation was 3.25 years. 24.0% had significant weight gain, which was more likely for uninsured minority patients than insured whites (adjusted odds ratio=2.85 , 95%CI: 1.66, 4.90). The rate of BMI increase in mixed effects models was greatest for uninsured minorities. Of 455 overweight at baseline, 29% were projected to become obese in 4 years.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this majority Hispanic HIV+ cohort, 60% were overweight or obese at baseline, and uninsured minority patients gained weight more rapidly. These data should prompt greater attention by HIV providers to prevention of obesity.

Introduction

Obesity has become a leading health threat in the United States (U.S.). In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2009 to 2010, 35.7% of U.S. adults were obese.1 Obesity is more prevalent in Hispanic and non-Hispanic black populations and in persons of lower socioeconomic status (SES).2-6 Minority race and low SES also increase the risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.7, 8 Thus, communities most severely affected by the HIV epidemic are also more likely to have a high prevalence of obesity.7, 9 However, few studies have examined the disparities in the prevalence of obesity and weight gain in HIV-infected (HIV+) populations.

Traditionally, the focus of HIV providers has been on preventing HIV-related wasting, weight loss, and lipodystrophy.10-12 With the advent of highly-active antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV-specific morbidity and mortality have diminished while non-HIV specific conditions, such as cardiovascular disease have grown as health threats for HIV+ persons.13-17 In this environment, providers may need to pay greater attention to preventing obesity and related conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.18-24

The prevalence of obesity in HIV+ cohorts ranges from 17 to 32% in cross-sectional studies.24-31 However, point prevalence studies do not elucidate weight change patterns that are indicative of the future severity of this problem. Previous studies of weight change in HIV+ cohorts have focused on the first 12 to 24 months on ART, when weight gain may be considered beneficial,12, 29, 32, 33 or on military cohorts with low baseline rates of obesity.34, 35 To our knowledge, longitudinal analyses of weight changes have not been conducted in HIV+ cohorts on long-term ART.

We examined change in body mass index (BMI) over a 4-year timeframe in a Hispanic-majority HIV+ cohort receiving care from the largest HIV clinic in South-Central Texas. This region is greatly affected by obesity. In 2010, 32.4% of adult residents in South-Central Texas were obese, and 66.3% were either overweight or obese.36 Because the vast majority of the cohort is receiving chronic ART, we hypothesized that the prevalence of obesity would approximate that observed in the local population. We hypothesized that there would be significant disparities in weight gain such that minorities and persons with lower socio-economic status would be more affected as is observed in the general population.2, 4, 6, 37 Further, we hypothesized that health insurance status, as a correlate of SES,38, 39 would modify the association of race-ethnicity with weight gain, such that uninsured minorities would be the most severely affected by significant weight gain, as in general populations.2, 4-6, 40-42

Methods

Description of the South Texas HIV Cohort

The South Texas HIV Cohort includes patients receiving care from 1/1/07 through 12/31/10 in the Family Focused AIDS Clinical Treatment & Services clinic. This clinic is the largest HIV treatment center in South-Central Texas and located in a publicly-funded county hospital affiliated with an academic medical center in San Antonio, Texas. Study data were obtained from an electronic medical record (EMR) system and included: demographics, health insurance information, physiologic measures, clinical diagnoses, laboratory data, visit data, and prescribed medications. Cohort patients were ≥18 years old at their first clinic encounter and not known to be incarcerated per Institutional Review Board specifications. If patients under 18 years of age were seen in the clinic, EMR data was censored prior to their 18th birthday. HIV diagnosis was validated by an ICD-9-CM code for HIV infection (v08 or 042.xx) in the EMR or a visit to the HIV clinic and confirmatory laboratory results (positive HIV ELISA and Western Blot, or plasma HIV-1 RNA level >1000 copies/mL). The 19 questionable cases were resolved by chart review. The resultant cohort totaled 1,890 individuals who received longitudinal care in the HIV clinic.

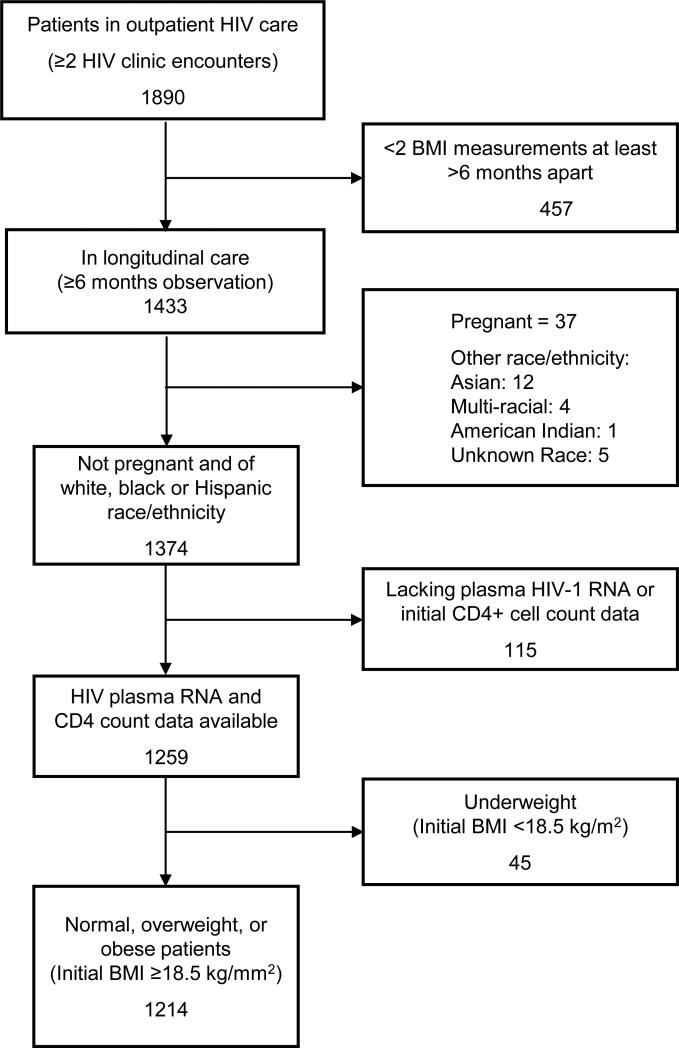

For our analysis of weight change, we selected patients with: 1) at least two HIV clinic visits during the observation period from 1/1/2007 to 12/31/2010; 2) at least six months between consecutive BMIs; 3) no pregnancy in this timeframe; and 4) white, black, or Hispanic race-ethnicity because other racial-ethnic groups comprised only 1.5% of the cohort. We excluded patients with missing plasma HIV-1 RNA or initial CD4+ count data. We also excluded patients who were underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2 at baseline measurement) because weight gain for underweight individuals is often a treatment goal. Our final cohort totaled 1,214 individuals (Figure 1). Of the 959 excluded patients, 20% were women; median age was 39 years (IQR: 30, 47); and race-ethnicity was 34% white, 42% Hispanic, 17% black, and 7% other.

Figure 1.

Cohort Sample Selection Flow Diagram

Outcome Variables

The primary study outcome was significant weight gain specified dichotomously as ≥3% annual increase in BMI, calculated as the difference between the first (baseline) and last BMI in the observation period divided by the observation time in years. We selected this outcome because a 3% annual weight gain leads to obesity in only three years among persons at the midpoint of the overweight range (e.g., 27.5 kg/m2) and it is five to 10 times greater than the average increase in BMI for the general U.S. population which is 3.4% in men and 5.2% in women over a 10 year period.43, 44 To calculate change in BMI, we excluded heights that differed by >10cm for an individual (5.4% of all measurements) and used each patient's average height to calculate BMI using the formula: weight/(average height during observation period).2 All BMIs <15 kg/m2 or >50 kg/m2 and any BMI that changed more than ±5% from the prior recorded BMI were manually checked, and apparent data entry errors were excluded (406 of 16,451 or 2.5%).

Independent Variables

Primary independent variables

Race-ethnicity/Insurance status

Self-reported race-ethnicity was categorized as: Hispanic, non-Hispanic black (black), or non-Hispanic white (white). Health insurance status, based on the most common type for all visits, was classified as: 1) insured (i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, and all private insurance programs); or 2) uninsured (i.e., medical care provided through a county or federal financial assistance plan, available on a sliding scale for those with incomes <300% of the Federal Poverty Level). Insurance status serves as an indicator of SES as in other studies.38, 39 We specified the hypothesized interaction between insurance and race/ethnicity in a four category variable: a) insured white, b) uninsured white, c) insured Hispanic or black (minority), or d) uninsured minority.

Demographic variables

These characteristics included: age at first clinic visit in the observation period, gender, and mean household income per year for the patient's residential zip code as an alternative measure of SES.45 Self-reported HIV transmission categories were: heterosexual sex, men who have sex with men (MSM), injection drug use (IDU), and other, including unknown or missing. The IDU category includes those MSM reporting IDU due to small sample size of that dual risk category (n=13).

Clinical variables

BMI is measured in the clinic prior to each provider visit using one of two regularly calibrated standing scales to calculate weight, and height is calculated using a stadiometer, and calculated as weight in kg/ (height in meters)2. The first or baseline BMI in the observation period was categorized as: normal (18.5 to <25 kg/m2); overweight (25 to <30 kg/m2), or obese (≥30 kg/m2).46 Immunologic status, based on the first CD4+ cell count in the observation period (hereafter initial CD4+ cell count), was categorized as: <200, 200-349, or ≥350 cells/μL. Because of changes in plasma HIV-1 RNA assay threshold during the observation period, virologic failure was defined as any two plasma HIV-1 RNA levels >1000 copies/ml at least 24 weeks after starting ART. Diabetes mellitus diagnosis was based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 250.XX at ≥2 visits or hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%; and hypertension from ICD-9-CM codes (401.xx at ≥2 visits) or two blood pressure measurements >140 mmHg systolic or >90 mmHg diastolic. Hepatitis C (HCV) infection was determined by positive HCV antibody test or HCV RNA PCR. ART type was based on EMR prescription records during the observation period: 1) receipt of ART without a protease inhibitor (PI) prescription, 2) receipt of ART with a PI prescription, and 3) no prescriptions for ART, due to the known association of PIs with metabolic syndrome, obesity, and weight change in prior studies.29, 32, 47

Health care utilization variables

The per-patient observation period was the time between first and last available BMI measurement within the 2007 to 2010 observation period. The number of HIV clinic visits with documented weights during the observation period was used as a metric of care intensity, with those patients in the lowest quartile (<7 visits) characterized as receiving infrequent HIV clinic follow-up.

Statistical Analyses

We first examined the interaction between race-ethnicity and health insurance status with the primary outcome, significant annual weight gain. We then estimated multivariate logistic regression models to examine the association of race-ethnicity/insurance status with significant weight gain after adjustment for demographic, clinical, and health care utilization variables. We excluded HIV transmission risk from the final model because it was not significant in ours or other studies.29 Because of collinearity with insurance type, we also excluded mean household income in residential zip code from the final model. We excluded indicators for diabetes or hypertension because these conditions may result from weight gain instead of being in the causal pathway. HCV status was excluded because it did not contribute specificity to any of the models. Interactions between individual predictors were examined using second order interaction terms in the logistic regression model.

In sensitivity analyses, we excluded the few patients who were not treated with ART (4%) and conducted a comparison between only Hispanic and non-Hispanic white patients. We also examined an alternative specification of the outcome as absolute change in BMI per year over the observation period. These additional analyses did not change our conclusions so they not reported.

We examined the longitudinal trajectory of BMI change including all BMI measurements for each patient over the observation period in a mixed effects model including both a random intercept and a random slope and using continuous BMI values as the response variable. The fully adjusted model included: the four-level race/ethnicity-insurance variable, years since baseline BMI, age at first visit, length of observation, gender, virologic failure, initial CD4+ cell count, initial BMI, ART type, and infrequent HIV clinic follow-up. Second order interactions between explanatory variables were also examined.

For all analyses, predictor variables were considered statistically significant if associated with a P value <0.05 and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are used. Pearson X2, Kruskal-Wallis H test, and logistic regression analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics (Version 17.0) and mixed effects models were generated using SAS GLIMMIX procedure (Version 9.2).

Results

Of 1,890 HIV+ patients receiving care the HIV clinic from 2007 to 2010, 1,214 met study inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The study cohort was 62.8% Hispanic, 23.4% white, and 13.8% black. Only 7% had private insurance, 33% had Medicare, 14% had Medicaid, and 46% were uninsured. At the start of the observation period (hereafter referred to as baseline), 37.5% of the cohort was overweight and 22.1% obese (Table 1). Of 946 patients who were not obese at baseline, 112 (11.8%) became obese during follow-up. Median observation period was 3.25 years; 45 patients (3.7%) in the cohort had an observation period of 6 months to 1 year, the remainder had ≥ 1 year. Significant weight gain, defined as a ≥3% annual increase in BMI,43 was observed for 24.0% (n=291) of the cohort. Baseline BMI categories for those patients who experienced significant weight gain were: 148 (50.9%) normal weight; 95 (32.6%) overweight; and 48 (16.5%) obese.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics Overall and by Race/ethnicity – Health Insurance Status.

| Characteristic n (% of column) or median (IQR) | Total population | White (Non-Hispanic) | Minority (Hispanic or Black) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance | Uninsured | Insurance | Uninsured | p valuea | ||

| n | 1214 | 162 (13.3%) | 122 (10.0%) | 496 (40.9%) | 434 (35.7%) | |

| Weight parameters | ||||||

| Significant weight gain (≥3%BMI/year) | 291 (24.0%) | 22 (13.6%) | 31 (25.4%) | 89 (17.9%) | 149 (34.3%) | <0.001c |

| Baseline BMI in observation period | ||||||

| 18.5 - <25 kg/m2 | 491 (40.4%) | 77 (47.5%) | 64 (52.5%) | 170 (34.3%) | 180 (41.5%) | <0.001c |

| 25 - <30 kg/m2 | 455 (37.5%) | 48 (39.6%) | 44 (36.1%) | 199 (40.1%) | 164 (37.8%) | |

| >=30 kg/m2 | 268 (22.1%) | 37 (22.8%) | 14 (11.5%) | 127 (25.6%) | 90 (20.7%) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age at first visit | 42 (36, 48) | 45 (40, 51) | 41 (34, 46) | 44 (39, 50) | 38.5 (31, 45) | <0.001b |

| Female gender | 247 (20.3%) | 29 (17.9%) | 15 (12.3%) | 99 (20.0%) | 104 (24.0%) | 0.029c |

| Mean household income/year for zipcode | 39,564 (33,869, 49,405) | 47,130 (39,311, 49, 639) | 47,130 (39,311, 51,861) | 37,197 (33,320, 47,130) | 39,311 (33,869, 48,045) | <0.001b |

| HIV Transmission Category | ||||||

| MSM | 548 (45.1%) | 73 (45.1%) | 69 (56.6%) | 196 (39.5%) | 210 (48.4%) | <0.001c |

| IDU or IDU+MSM | 79 (6.5%) | 13 (8.0%) | 6 (4.9%) | 45 (9.1%) | 15 (3.5%) | |

| Heterosexual sex | 254 (20.9%) | 24 (14.8%) | 21 (17.2%) | 106 (21.4%) | 103 (23.7%) | |

| Other (includes unknown) | 333 (27.4%) | 52 (32.1%) | 26 (21.3%) | 149 (30.0%) | 106 (24.4%) | |

| Clinical Variables | ||||||

| Years living with HIV | 6.1 (1.7, 12.0) | 11.1 (4.3, 16.6) | 3.1 (0.99, 9.2) | 8.5 (3.1, 13.1) | 3.1 (1.0, 8.2) | <0.001b |

| On antiretroviral therapy (ART) | 1170 (96.4%) | 160 (98.8%) | 112 (91.8%) | 487 (98.2%) | 411 (94.7%) | <0.001c |

| On protease inhibitor-based ART (n=1170 on ART) | 657 (56.2%) | 106 (66.3%) | 63 (56.3%) | 285 (58.5%) | 203 (49.4%) | 0.002c |

| Initial CD4+ category in observation period | ||||||

| <200 cells/μL | 374 (30.8%) | 41 (25.3%) | 36 (29.5%) | 148 (29.8%) | 149 (34.3%) | 0.06c |

| 200-349 cells/μL | 285 (23.5%) | 39 (24.1%) | 37 (30.3%) | 126 (25.4%) | 83 (19.1%) | |

| ≥350 cells/μL | 555 (45.7%) | 82 (50.6%) | 49 (40.2%) | 222 (44.8%) | 202 (46.5%) | |

| Virologic failure | 638 (52.6%) | 88 (54.3%) | 62 (50.8%) | 277 (55.8%) | 211 (48.6%) | 0.16c |

| Diabetes | 185 (15.2%) | 19 (11.7%) | 10 (8.2%) | 108 (21.8%) | 48 (11.1%) | <0.001c |

| Hypertension | 732 (60.3%) | 102 (63.0%) | 65 (53.3%) | 337 (67.9%) | 228 (52.5%) | <0.001c |

| HCV infection | 178 (14.7%) | 32 (19.8%) | 17 (13.9%) | 97 (19.6%) | 32 (7.4%) | <0.001c |

| Health Care Utilization | ||||||

| Months of observation | 39.0 (25, 44) | 41.5 (25, 45) | 31.3 (21, 41) | 41.7 (30, 45) | 35.3 (23, 43) | <0.001b |

| Infrequent HIV clinic follow up | 261 (21.5%) | 26 (16.0%) | 36 (39.5%) | 90 (18.1%) | 109 (25.1%) | 0.003c |

Abbreviations: IQR = Intraquartile range; BMI = Body Mass Index (kg/m2); MSM = Men who have sex with men; IDU = Injection drug use; ART = antiretroviral therapy; Virologic failure: 2 HIV-1 plasma RNA levels >1000 copies/ml ≥24 weeks after starting ART; hypertension = two blood pressure readings >140 mmHg systolic or >90 mmHg diastolic or ICD-9-CM codes (401.xx at ≥2 visits); diabetes = hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5% or CD-9-CM diagnosis codes 250.XX at ≥2 visits; HCV infection: HCV Antibody or HCV RNA PCR positive; Infrequent HIV clinic follow up = <7 HIV provider visits during observation period (lowest quartile).

The statistic tests for a difference across all four categories.

Kruskal-Wallis H test

Pearson X2

All patient characteristics differed significantly by the four-level race-ethnicity/insurance status variable except for CD4+ category and virologic failure (Table 1). Uninsured minorities were younger, more likely to be women, and less likely to receive PI-based ART. Regardless of insurance type, minority patients were more likely to be overweight or obese (minority 62.4% vs. whites 50.4%; odds ratio (OR) 1.63 [95%CI 1.25 to 2.13]; P <0.001), and more likely to have diabetes (minority 16.8% vs. white 10.2%; OR 1.77 [CI 1.16 to 2.70]; P = 0.007). Insured patients were more likely to be overweight or obese at baseline (insured 57% vs. uninsured 43%; OR 1.30 [95%CI 1.03, 1.64]; P =0.025).

In the unadjusted analysis, significant weight gain was more likely for uninsured whites (OR 2.17 [95% CI 1.18-3.98]) and uninsured minorities (OR 3.33 [CI 2.04-5.44]) but insured minorities did not differ when compared to insured whites (Table 2). Patients with a normal baseline BMI had increased odds of significant weight gain compared with those who were obese at baseline, but overweight and obese patients did not differ significantly. Patients with severe immunosuppression (initial CD4+ cell count <200 cells/μL) had greater odds of significant weight gain than patients with initial CD4+ cell count ≥350 cells/μL. Patients with virologic failure were less likely to have significant weight gain.

Table 2.

Bivariate and Multivariate Models to Predict Significant Weight Gain (≥3% increase in BMI/year).

| Variable | Bivariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariatea aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Race-Ethnicity/Insurance Category | ||

| Insured White | reference | reference |

| Uninsured White | 2.17 (1.18-3.98) | 1.60 (0.83, 3.08) |

| Insured Minority | 1.39 (0.84-2.31) | 1.51 (0.89, 2.58) |

| Uninsured Minority | 3.33 (2.04-5.44) | 2.85 (1.66, 4.90) |

| Baseline BMI in observation period | ||

| ≥30 kg/m2 (obese) | reference | reference |

| 25 - <30 kg/m2 (overweight) | 1.21 (0.82-1.78) | 1.06 (0.70, 1.61) |

| 18.5 - <25 kg/m2 (normal) | 1.98 (1.37-2.85) | 1.61 (1.08, 2.42) |

| Age at first visit (years) | 0.97 (0.96-0.99) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) |

| Female gender | 0.79 (0.56-1.11) | 0.87 (0.59, 1.26) |

| Mean annual household income for zip code <$39,564 (median for sample) | 0.90 (0.70-1.18) | - |

| HIV Transmission Category | - | |

| Heterosexual Sex | reference | |

| MSM | 1.25 (0.88-1.77) | |

| IVDU or IVDU+MSM | 1.02 (0.56-1.86) | |

| Other | 0.94 (0.63-1.39) | |

| Years living with HIV | 0.95 (0.93, 0.97) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) |

| ART Type | ||

| ART without PIs | reference | reference |

| ART with PIs | 0.87 (0.67-1.14) | 1.13 (0.83, 1.53) |

| no ART | 0.75 (0.35-1.60) | 0.82 (0.35, 1.92) |

| Initial CD4+ count in observation period | ||

| ≥350 cells/μL | reference | reference |

| 200-349 cells/μL | 1.44 (1.00-2.06) | 1.37 (0.94, 2.00) |

| <200 cells/μL | 3.06 (2.25-4.16) | 2.40 (1.71, 3.35) |

| Virologic failure | 0.72 (0.56-0.94) | 0.82 (0.60, 1.12) |

| Months of Observation | 0.96 (0.95-0.97) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) |

| Infrequent HIV clinic follow up | 1.38 (1.01-1.87) | 0.69 (0.46, 1.02) |

Abbreviations: OR = odds ratio; aOR = adjusted OR based on a final multiple logistic regression model with the following covariates: race/insurance, baseline BMI, gender, initial CD4+ category, virologic failure, months of observation, and HIV provider visit intensity; Virologic failure = 2 HIV-1 plasma RNA levels >1000 copies/ml ≥24 weeks after starting antiretroviral therapy; ART = Antiretroviral therapy; PI=protease inhibitor; Infrequent HIV clinic follow up = <7 HIV provider visits during observation period (lowest quartile).

Exclusions from the multivariate model: Annual income removed due to colinearity with insurance; HIV transmission category removed due to lack of association in prior studies.

After adjustment for demographic and clinical variables, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of significant weight gain was 2.85 [CI 1.66 – 4.90] for uninsured minorities compared with whites with insurance but race-ethnicity/insurance groups did not differ significantly (Table 2). Persons with a normal baseline BMI had nearly 60% higher adjusted odds of significant weight gain compared with those who were obese at baseline. Severe immunosuppression was also associated with increased adjusted odds of significant weight gain than those with initial CD4 ≥350 cells/μL.

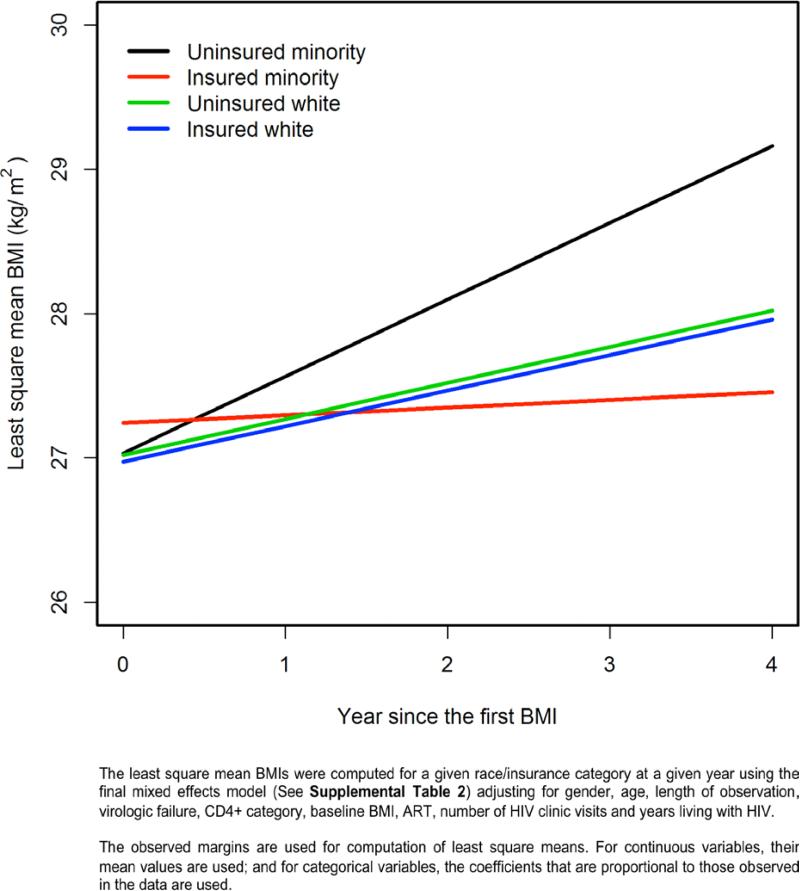

A fully adjusted mixed effects model including all BMI measurements revealed that uninsured minorities had a significantly more rapid increase in BMI over the observation time than other race-ethnicity/insurance categories (Figure 2 and Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content). For all 1214 patients in the cohort, the proportion of obese patients was projected to rise from 22.1% at baseline to 31.3% after 4 years. Of the 455 patients who were overweight at baseline, 131 (28.8%) were projected to become obese after 4 years (Table 3). The number of patients projected to be obese also varied by race-ethnicity/insurance category; the adjusted mixed effects model revealed that 26% of insured whites, 22% of uninsured whites, 30% of insured minorities and 38% of uninsured minorities were predicted to be obese at four years from baseline. Patients with severe immunosuppression and those without virologic failure had a significantly greater annual increases in BMI than those with less severe immunosuppression or with virologic failure (P < 0.001 and P = 0.04, respectively, Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content). Compared with obese patients, patients in other BMI categories had significantly greater annual increases in BMI.

Figure 2.

Model-based Least Square Mean BMI Over Time by Race/ethnicity - Insurance Statusa

Table 3.

Mixed Effects Model-Based BMI Category Prediction from One to Four Years After Baseline BMI

| Baseline BMI (actual)a | Year 1b | Year 2b | Year 3b | Year 4b | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Over-weight | Obese | Normal | Over-weight | Obese | Normal | Over-weight | Obese | Normal | Over-weight | Obese | ||

| Normal | 491 | 420 | 71 | 0 | 375 | 106 | 10 | 340 | 126 | 25 | 310 | 137 | 44 |

| 40.4% | 85.5% | 14.5% | 0.0% | 76.4% | 21.6% | 2.0% | 69.2% | 25.7% | 5.1% | 63.1% | 27.9% | 9.0% | |

| Over-weight | 455 | 39 | 361 | 55 | 54 | 310 | 91 | 67 | 274 | 114 | 83 | 241 | 131 |

| 37.5% | 8.6% | 79.3% | 12.1% | 11.9% | 68.1% | 20.0% | 14.7% | 60.2% | 25.1% | 18.2% | 53.0% | 28.8% | |

| Obese | 268 | 0 | 22 | 246 | 2 | 34 | 232 | 11 | 41 | 216 | 16 | 46 | 206 |

| 22.1% | 0.0% | 8.2% | 91.8% | 0.7% | 12.7% | 86.6% | 4.1% | 15.3% | 80.6% | 6.0% | 17.2% | 76.9% | |

| Totalb | 1214 | 459 | 454 | 301 | 431 | 450 | 333 | 418 | 441 | 355 | 409 | 424 | 381 |

| 100% | 37.8% | 37.4% | 24.8% | 35.5% | 37.1% | 27.4% | 34.4% | 36.3% | 29.2% | 33.7% | 34.9% | 31.4% | |

Percents based on column totals.

Percents based on row totals.

Discussion

In a predominately Hispanic HIV+ cohort, 60% were overweight or obese at baseline, higher than most cross-sectional studies of weight in HIV+ patients,25-28 and our prediction model estimates that overweight/obesity will increase to 66% over 4 years. Over the same observation period, 2007-2010, data from the San Antonio Metropolitan Statistical Area show that overweight/obesity in the surrounding population dropped from 69% to 63%,36 indicating that our cohort may be at more risk than the general population. A significant interaction between race-ethnicity and health insurance status, used as a proxy for SES, demonstrated that uninsured minorities had over three times greater odds of significant weight gain than white persons with insurance. Interestingly, insured minorities and uninsured whites did not differ significantly from insured whites after adjustment. The increased risk of weight gain for uninsured minorities was observed for both a dichotomous outcome measure (≥3% BMI increase/year) and a mixed effects model examining longitudinal change in BMI as a continuous outcome over a median 3.25 years of follow-up.

Cardiovascular disease has become a major cause of morbidity and mortality in persons with HIV infection.13-17, 48-51 Because overweight- and obesity-related complications, such as diabetes mellitus, are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, prevention of excessive weight gain in HIV-infected persons may represent a currently overlooked opportunity for primary prevention. While recent research suggests that being overweight may reduce the risk of death in general populations, obesity still carries major health risks.52, 53 Nationally, the prevalence of overweight and obesity increased rapidly from the 1960s through 2004, but remained relatively stable over the past decade.54 This is not the case for our HIV-infected cohort, in whom one quarter were gaining weight at a rate over 5 times faster than the general population.43, 44 Our analysis of longitudinal changes in BMI predicts that nearly 30% of HIV+ patients who are overweight at baseline will become obese within 4 years.

The association between race-ethnicity and weight gain has not been observed by other investigators, but their minority populations have been dominantly African American.29, 32, 34 The increased representation of Hispanics in this cohort may be the reason for this discrepancy, as Hispanic men, who comprise the majority of this cohort, have the highest prevalence of overweight/obesity in the general population, compared with non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black men.2, 31 In the general U.S. population, racial-ethnic minorities and those with lower childhood and adult SES have greater lifetime weight gain, and these trends appear to be consistent with the patterns observed in this study.55 We did not observe significant differences by gender, HIV transmission category, or mean household income in the residential zip code, an alternative measure of SES. Since women comprised only 20% of our cohort, we were likely underpowered to find gender differences. We did not observe the association between ART that includes PIs and significant weight gain that was reported in two studies with a primarily black minority population,29, 32 but the U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study also did not find this association.34

There are several limitations to this analysis. Our study population received care from only one HIV clinic, albeit the largest such clinic in South-Central Texas, and although most patients receive care within our county healthcare system, any outside clinical encounters would not be documented. We did not have a direct measure of SES or time on ART, and some patients only had two BMI measurements, though only 3.7% of cohort had <12 months observation time. We also lacked information about the reasons for weight gain, which for some patients and their providers may be a goal of treatment. Prior to the advent of potent ART, obesity was found to be protective against both mortality and disease progression.28, 56-60 Recent studies suggest that overweight may be associated with improved immune response to ART; however, obesity was associated with a less robust immune response.33, 35, 61 To address this limitation, we excluded underweight patients at baseline and adjusted for the level of immunodeficiency. We also conservatively examined a threshold for significant weight gain that is at least five times higher than that observed in the general population.43, 44

In this primarily Hispanic cohort in longitudinal HIV care, we observed a high prevalence of overweight and obesity at baseline accompanied by significant weight gain, especially for uninsured minority patients, over more than three years of follow-up. If confirmed in other cohorts, these data suggest that HIV providers may need to be as attentive to addressing excessive weight gain as they are at managing weight loss in their patients. To avert severe obesity-related complications for patients with HIV infection, it may be necessary to integrate clinic-based interventions for weight control.62-66 Our data suggest that uninsured minority patients should be a primary focus for such interventions, though the overall prevalence of obesity in the cohort and the high baseline prevalence of obesity in insured patients suggest that a clinic-wide intervention may be necessary. It is also important to explore patients’ perceptions about weight, particularly among minority groups who may consider overweight and obesity to be an indication of health.67, 68 This study is unique in examining longitudinal changes in weight in a primarily Hispanic HIV+ cohort, but similar analyses need to be conducted in other HIV cohorts to determine whether the alarming trends in weight gain that we observed are a health concern for HIV+ patients nationally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Turner receives salary support from University Health System as Director of Health Outcomes Improvement. The development of the South Texas HIV Cohort data repository was funded by a pilot grant to Dr. Taylor from the UTHSCSA Institute for Integration of Medicine and Science's Clinical and Translational Science Award [8UL1TR000149]. Dr. Taylor receives support from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases [K23AI081538].

Footnotes

Prior presentations at meetings: Two prior analyses of this cohort have been presented at conferences: Taylor BS, Garduño LS, Gerardi M, Walter E, Bullock D, Turner BJ. “Evaluating Failures in Weight and Diabetes Management in an HIV Cohort.” Society for General Internal Medicine 35th Annual Meeting. Orlando, FL. May, 2012 and “Overlapping Epidemics: HIV, Diabetes, and Obesity in the San Antonio HIV Cohort,” Texas Infectious Diseases Society Annual Meeting. San Antonio, TX, June 10, 2012.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: None of the authors report significant conflicts of interest with regards to this publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 82, edJanuary. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Prevalence of Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: state-specific obesity prevalence among adults --- United States, 2009. MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(30):951–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert SA, Reither EN. A multilevel analysis of race, community disadvantage, and body mass index among adults in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(12):2421–34. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Q, Wang Y. Trends in the association between obesity and socioeconomic status in U.S. adults: 1971 to 2000. Obes Res. 2004;12(10):1622–32. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Q, Wang Y. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the United States: do gender, age, and ethnicity matter? Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1171–80. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Characteristics associated with HIV infection among heterosexuals in urban areas with high AIDS prevalence --- 24 cities, United States, 2006-2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60(31):1045–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006-2009. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grinspoon S, Mulligan K. Weight loss and wasting in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(Suppl 2):S69–78. doi: 10.1086/367561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallant JE, Staszewski S, Pozniak AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir DF vs stavudine in combination therapy in antiretroviral-naive patients: a 3-year randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(2):191–201. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shikuma CM, Zackin R, Sattler F, et al. Changes in weight and lean body mass during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(8):1223–30. doi: 10.1086/424665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Achhra AC, Amin J, Law MG, et al. Immunodeficiency and the risk of serious clinical endpoints in a well studied cohort of treated HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2010;24(12):1877–86. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833b1b26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triant VA. HIV infection and coronary heart disease: an intersection of epidemics. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(Suppl 3):S355–61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2506–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York City. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(6):397–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Islam FM, Wu J, Jansson J, Wilson DP. Relative risk of cardiovascular disease among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HIV Med. 2012;13(8):453–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smit E, Skolasky RL, Dobs AS, et al. Changes in the incidence and predictors of wasting syndrome related to human immunodeficiency virus infection, 1987-1999. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(3):211–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mocroft A, Sabin CA, Youle M, et al. Changes in AIDS-defining illnesses in a London Clinic, 1987-1998. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21(5):401–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogg R, Samji H, Cescon A, et al. Temporal Changes in Life Expectancy of HIV+ Individuals: North America.. Paper presented at: 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, WA. March 5-8, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodger A, Lodwick R, Schechter M, et al. Mortality in Patients with Well-controlled HIV and High CD4 Counts in the cART Arms of the SMART and ESPRIT Randomized Clinical Trials Compared to the General Population.. Paper presented at: 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, WA. March 5-8, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogers RP, Bemelmans WJ, Hoogenveen RT, et al. Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels: a meta- analysis of 21 cohort studies including more than 300 000 persons. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(16):1720–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schafer I, von Leitner EC, Schon G, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in the elderly: a new approach of disease clustering identifies complex interrelations between chronic conditions. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim DJ, Westfall AO, Chamot E, et al. Multimorbidity Patterns in HIV-Infected Patients: The Role of Obesity in Chronic Disease Clustering. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827303d5. Epub ahead of print 27 sept. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amorosa V, Synnestvedt M, Gross R, et al. A tale of 2 epidemics: the intersection between obesity and HIV infection in Philadelphia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(5):557–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crum-Cianflone N, Tejidor R, Medina S, et al. Obesity among patients with HIV: the latest epidemic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(12):925–30. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariz CA, Albuquerque Mde F, Ximenes RA, et al. Body mass index in individuals with HIV infection and factors associated with thinness and overweight/obesity. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27(10):1997–2008. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2011001000013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones CY, Hogan JW, Snyder B, et al. Overweight and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) progression in women: associations HIV disease progression and changes in body mass index in women in the HIV epidemiology research study cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(Suppl 2):S69–80. doi: 10.1086/375889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tate T, Willig AL, Willig JH, et al. HIV infection and obesity: where did all the wasting go? Antiviral Therapy. 2012;17(7) doi: 10.3851/IMP2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodgson LM, Ghattas H, Pritchitt H, et al. Wasting and obesity in HIV outpatients. AIDS. 2001;15(17):2341–2. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200111230-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella F, et al. Disparities in prevalence of key chronic diseases by gender and race/ethnicity among antiretroviral-treated HIV-infected adults in the US. Antiviral Therapy. 2013 doi: 10.3851/IMP2450. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakey W, Yang LY, Yancy W, et al. From Wasting to Obesity: Initial Antiretroviral Therapy and Weight Gain in HIV-Infected Persons. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012 doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0234. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koethe JR, Jenkins CA, Shepherd BE, et al. An optimal body mass index range associated with improved immune reconstitution among HIV-infected adults initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(9):952–60. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crum-Cianflone N, Roediger MP, Eberly L, et al. Increasing rates of obesity among HIV-infected persons during the HIV epidemic. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4):e10106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crum-Cianflone NF, Roediger M, Eberly LE, et al. Impact of weight on immune cell counts among HIV-infected persons. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18(6):940–6. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00020-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 2007-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Differences in Prevalence of Obesity Among Black, White, and Hispanic Adults --- United States, 2006--2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58(27):740–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. U.S. Census Bureau, edCurrent Population Reports. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C.: 2011. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2010. pp. P60–239. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monheit AC, Vistnes JP. Race/ethnicity and health insurance status: 1987 and 1996. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):11–35. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas JS, Adler NE. The Causes of Vulnerability: Disentangling the Effects of Race, Socioeconomic Status and Insurance Coverage on Health. The Institute of Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. U.S. disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:235–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haas JS, Lee LB, Kaplan CP, et al. The association of race, socioeconomic status, and health insurance status with the prevalence of overweight among children and adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(12):2105–10. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yanovski JA, Yanovski SZ, Sovik KN, et al. A prospective study of holiday weight gain. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(12):861–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williamson DF, Kahn HS, Remington PL, Anda RF. The 10-year incidence of overweight and major weight gain in US adults. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(3):665–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.U.S. Census Bureau American FactFinder. 2000 Accessed 4/2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organization . Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. Geneva: p. 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silva M, Skolnik PR, Gorbach SL, et al. The effect of protease inhibitors on weight and body composition in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1998;12(13):1645–51. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stein JH, Hsue PY. Inflammation, immune activation, and CVD risk in individuals with HIV infection. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308(4):405–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.8488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Obel N, Thomsen HF, Kronborg G, et al. Ischemic heart disease in HIV-infected and HIV- uninfected individuals: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(12):1625–31. doi: 10.1086/518285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, et al. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1120–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Currier JS, Taylor A, Boyd F, et al. Coronary heart disease in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(4):506–12. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;309(1):71–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.113905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Golubic R, Ekelund U, Wijndaele K, et al. Rate of weight gain predicts change in physical activity levels: a longitudinal analysis of the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.58. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarke P, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Social disparities in BMI trajectories across adulthood by gender, race/ethnicity and lifetime socio-economic position: 1986-2004. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(2):499–509. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shor-Posner G, Campa A, Zhang G, et al. When obesity is desirable: a longitudinal study of the Miami HIV-1-infected drug abusers (MIDAS) cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23(1):81–8. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200001010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guenter P, Muurahainen N, Simons G, et al. Relationships among nutritional status, disease progression, and survival in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6(10):1130–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palenicek JP, Graham NM, He YD, et al. Weight loss prior to clinical AIDS as a predictor of survival. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study Investigators. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10(3):366–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wheeler DA, Gibert CL, Launer CA, et al. Weight loss as a predictor of survival and disease progression in HIV infection. Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18(1):80–5. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199805010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Womack J, Tien PC, Feldman J, et al. Obesity and immune cell counts in women. Metabolism. 2007;56(7):998–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crum-Cianflone NF, Roediger M, Eberly LE, et al. Obesity among HIV-infected persons: impact of weight on CD4 cell count. AIDS. 2010;24(7):1069–72. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337fe01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.ter Bogt NC, Bemelmans WJ, Beltman FW, et al. Preventing weight gain by lifestyle intervention in a general practice setting: three-year results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):306–13. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.ter Bogt NC, Bemelmans WJ, Beltman FW, et al. Preventing weight gain: one-year results of a randomized lifestyle intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(4):270–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsai AG, Wadden TA, Rogers MA, et al. A primary care intervention for weight loss: results of a randomized controlled pilot study. Obesity. 2010;18(8):1614–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jay M, Gillespie C, Schlair S, et al. The impact of primary care resident physician training on patient weight loss at 12 months. Obesity. 2012 doi: 10.1002/oby.20237. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Engelson ES, Agin D, Kenya S, et al. Body composition and metabolic effects of a diet and exercise weight loss regimen on obese, HIV-infected women. Metabolism. 2006;55(10):1327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barroso CS, Peters RJ, Johnson RJ, et al. Beliefs and perceived norms concerning body image among African-American and Latino teenagers. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(6):858–70. doi: 10.1177/1359105309358197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paeratakul S, White MA, Williamson DA, et al. Sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and BMI in relation to self-perception of overweight. Obes Res. 2002;10(5):345–50. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.