(+)-Zwittermicin A (1), [1] a water-soluble natural antibiotic reported in 1994 from the fermentation of the soil-borne bacterium Bacillus cereus, shows significant activity against phytopathogenic fungi.[2] Most importantly, 1 synergizes the bioactivity of the endotoxin produced by Bacillus thuringensis (BT), a ‘green’ insecticide used globally protection of vegetable crops and eradication of gypsy moth from forest trees.[2,3] BT toxin and related biocontrol agents are important commodities used in the fight against declining agricultural production and rising third world food shortages.[3b] The biosynthesis of the sugar-like 1 is very unusual; the molecule does not derive from carbohydrate metabolism, as the structure may suggest, but arises from a non-ribosomal peptidyl-polyketide synthase (NRPS-PKS) pathway, starting with an activated serine (Ser, C13–C15, zwittermicin A numbering). Zwittermicin A is the first described polyketide in which C2 chain extensions occur by condensations of C2 units (followed by loss of CO2) derived from hydroxymalonate (HM, C7–C8) and aminomalonate (AM, C9–C10) in addition to the more common extender, malonate. [4]

Combinatorial biosynthetic engineering of AM PKS modules has great potential for production of exotic ‘non-natural’ amino-polyketides[4c] and possible remodeling of PKS structures alkaloids by exploitation of the innate nucleophilicity of the NH2 group. Despite high interest in 1, the structure of zwittermicin A has eluded attempts to define its configuration for 14 years until now.[1c]

We report here the complete absolute stereostructure of (+)-1 by way of deductive reasoning and the first total synthesis of its enantiomer (−)-1. Our surprise finding – that C13-C15 formally derives from D-Ser, rather than L-Ser[5] – has implications for structure-function of the loading domain in the NRPS-PKS complex that initiates biosynthesis of (+)-1.

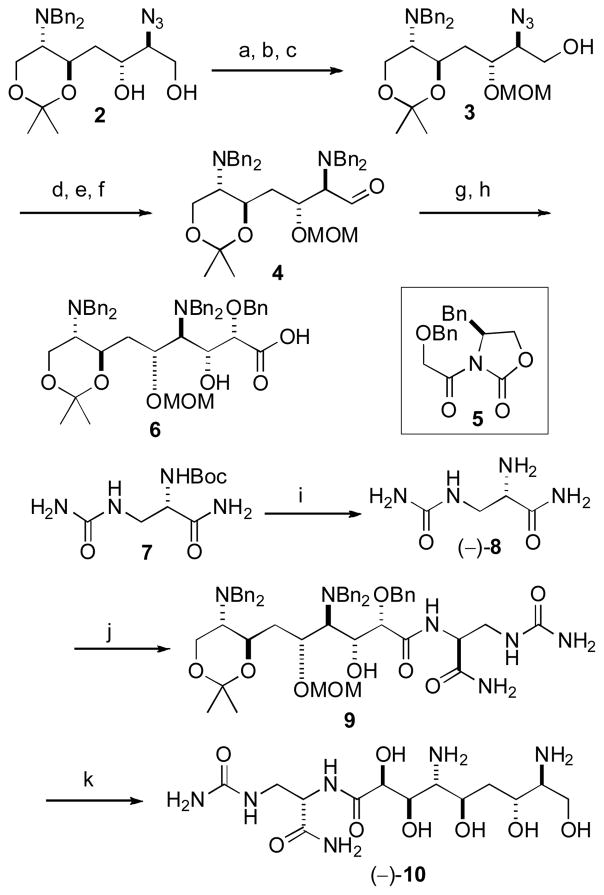

Azidodiol 2, prepared from L-serine as described earlier, [5] was refunctionalized by TBDPS protection6 of the terminal alcohol, MOM protection[7] of the secondary alcohol and removal of the TBDPS group[6] to give 3 in high yield (85% three steps, Scheme 1).[8] Transformation of the azido group in 3 to an N,N-dibenzyl group by hydrogenolysis (Lindlar’s catalyst[9]) followed by N-benzylation[6] gave a primary alcohol that was easily oxidized to the stable aldehyde 4 (84% three steps).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of (−)-10. Reagents and conditions: (a) TBDPSCl, imidazole, DMF, 0 °C-rt, 4 h, 91%; (b) MeOCH2Cl, Hünig’s base, CH2Cl2, 0 °C-rt, 56 h, 98%; (c) TBAF, THF, −10 °C, 4 h, 95%; (d) Lindlar cat., H2, (1 atm), EtOH, 14 h, 98%; (e) BnBr, K2CO3, CH3CN, 31 h, 91%; (f) (i) (COCl)2, DMSO, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, (ii) Et3N, 94%; (g) (i) 5, n-Bu2BOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, −78 to 0 °C, 3 h, (ii) 4, −78 to 0 °C, 2.5 h, 77%, dr 24:1; (h) H2O2, LiOH, 0 °C, 30 min, 96%; (i) TFA, 0 °C, 1 h, 98%; (j) (i) 6, EDCI, HOBt, DMF, 0 °C, 10 min, (ii) (−)-8, Et3N, 0 °C-rt, 1 h, 81%; (k) (i) HCl, MeOH, H2 (5 atm), Pd/C, 1 h, (ii) HCl, H2O, H2 (5 atm), Pd/C, 1 h, 76%. TBDPSCl= tert-butyldiphenylsilyl chloride, EDCI= 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloide, hOBt= 1-hydroxybenzotriazole.

Evan’s aldol addition of the chiral glycolate equivalent 5[10] to 4 followed by removal of the chiral auxiliary under standard conditions afforded carboxylic acid 6 in 74% yield and 92% de (two steps)[11] ready for coupling to the N-ureido-L-1,3-diaminopropionamide (−)-8 that was easily derived from the known amide 7.[12]

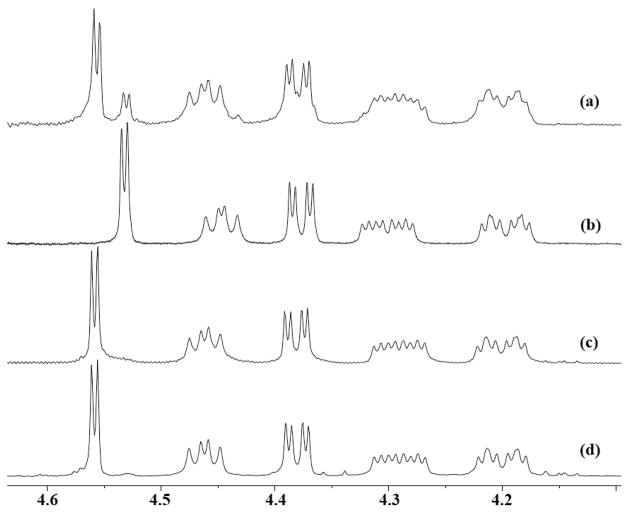

Coupling of 6 and 8[13] gave an amide 9 (81%) that was globally deprotected[14] to afford compound (−)-10 with the configuration proposed for (+)-1.[5] Although the 1H and 13C NMR spectra (400 MHz, D2O) of (+)-1[15,16] and (−)-10 were almost identical at C10–C15 (see Supporting information), chemical shift differences at H8 [(−)-10, δ 4.53, d, J = 2.0 Hz: (+)-1, δ 4.56, d, J = 2.0 Hz] were readily revealed upon measurements of a mixture of the two compounds (Figure 2). Additionally, the specific rotation of (−)-10 ([α]D −23.0°, H2O) was opposite in sign and of larger magnitude than values measured for natural (+)-1 ([α]D = +8.1°, H2O; lit.[1a] +8.9°) under the same conditions.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, D2O): (a) 1:3 mole ratio of synthetic (−)-10 and natural (+)-1. (b) (−)-10 (c) (−)-1, and (d) 1:2 ratio of (−)-1 and natural (+)-1. Concentrations ~10 mM, no solvent suppression.

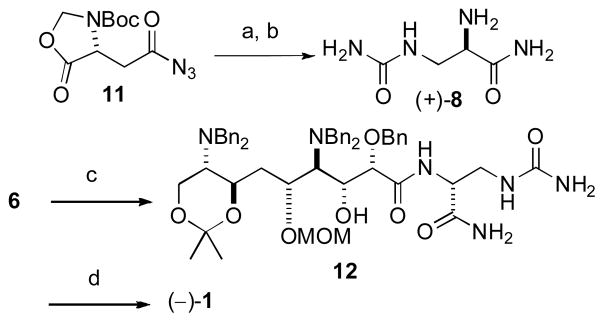

The relative configuration of the C8–C15 segment of (+)-1 was certain from analysis of 1H NMR spin system topicities and 13C NMR chemical shift differences from a C2 symmetric diamino tetraol derived from 2.[5] Considering that the amino acid configuration in (+)-1 was unequivocally L-, [5] the 1H and 13C NMR signals at C10–C15 showed negligible differences, and the largest 1H NMR difference occurred at H8, we hypothesized that the mismatch was due to inversion of all configurations in the diaminopolyol-carboxylate moiety of (−)-10: C8–C11, C13, and C14. The latter would negate the original assumption of a formal biosynthesis of 1 derived from an L-Ser starter unit[4a,5] in the NRPS loading domain and require involvement of D-Ser. In order to test this hypothesis, 12, a diastereomer of 9, was prepared (Scheme 2) by coupling carboxylic acid 6 with D-α-aminoamide (+)-8 (88%) (the latter compound was derived in two steps from the known acyl azide 11[17] by Curtius rearrangement followed by ammoniolysis). Deprotection of 12 under the conditions used previously (Scheme 1)[14] gave (−)-1 in 75% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of model (−)-1. Reagents and conditions: a) (i) μW, toluene, 110 °C, 15 min, (ii) THF, NH3, 30 min, (iii) 2M NH3, MeOH, 5 h, (iv) 1N NaOH, MeOH, 4.5 h, 62%; (b) TFA, 0 °C, 1 h, 99%; (c) (i) EDCI, HOBt, DMF, 0 °C, 10 min, (ii) (+)-8, Et3N, 0 °C-rt, 1 h, 88%; (d) (i) HCl, MeOH, H2 (5 atm), Pd/C, 1 h, (ii) HCl, H2O, H2 (5 atm), Pd/C, 1 h, 75%.

The NMR spectra of synthetic (−)-1 and natural (+)-1 were identical in all respects; co-addition of natural (+)-1 to (−)-1 and NMR measurements gave a single discrete set of 1H (Figure 1) and 13C signals corresponding to those of natural (+)-zwittermicin A.[1a]

Figure 1.

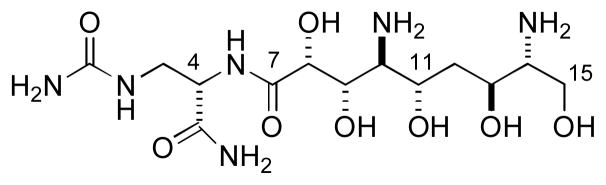

Natural (+)-zwittermicin A (1)

Finally, the specific rotation of synthetic (−)-1 ([α]D −7.9°, H2O) was opposite in sign and equal in magnitude of natural zwittermicin A. Therefore the configuration of zwittermicin A [(+)-1] is (4S,8R,9S,10S,11S,13S,14R) as depicted. The configurational assignment described here has implications for the biosynthesis of (+)-1. Three scenarios can be considered to explain the unexpected 14R configuration of zwittermicin A; direct incorporation of D-Ser at C13–C15, similar to that observed for the starter D-Ala residue of cyclosporine, [18a] α-epimerization of a carrier protein-bound L-Ser by an embedded epimerization domain, or the involvement of a dual function condensation/epimerization domain, such as those operating in the biosynthesis of arthrofactin[18b] and enduracidin.[18c] In the latter case, a single catalytic domain may be responsible for inversion of the α-configuration and coupling of the resultant thio-acyl D-Ser residue with a down-stream acceptor residue, however, this mechanism has yet to be associated with a mixed NRPS-PKS system. Although details have been reported for gene products ZmAG-ZmAI responsible for the AM extender unit, [4c] the identification of the genes and a mechanism responsible for the Ser loading domain and incorporation into C13–C15 of 1 are still unclear. Resolution of this mystery awaits more detailed annotation of the gene cluster for biosynthesis of (+)-1.

We briefly compared the biological activity of (+)-zwittermicin A with that of its synthetic enantiomer (−)-1 and by measuring the susceptibility to pathogenic fungi and Fluconazole-resistant pathogens of the genus Candida.

The minimum inhibitory activities of authentic natural (+)-1 against Candida albicans ATCC 14503 (MIC 55.7 μg/ml) and the Fluconazole-resistant strain C. albicans 96–489 (MIC 59.5 μg/ml) were found to comparable to the antifungal activities found by Handelsman et al. for (+)-1 against a range of plant pathogenic fungi of agricultural importance. ent-Zwittermicin A (−)-1, on the other hand was inactive (MIC > 128 μg/ml) under the same conditions. This interesting result implies that the activity of (+)-1 is due not to non-specific interactions with the diaminopolyol, but more closely allied to either transport across the cell wall or membrane, or a mechanism that implicates a more subtle chiral recognition motif at an as-yet unidentified intra-cellular target.

In summary, the absolute stereostructure of (+)-zwittermicin A (1) has been assigned unambiguously by total synthesis of (−)-1 in an overall yield of 1.9% (20 steps from N,N-dibenzyl-L-serine methyl ester). Interpretation of the configuration of (+)-1 implicates a ‘D-Ser’ motif in the biosynthesis of C13–C15 consistent with an antipodal configuration of the propagated Ser starter unit. Zwittermicin A and its enantiomer exhibit a differential activity against fungal pathogens that underscores the importance of chirality to the biological activity of these acyclic diaminopolyol natural products.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

In vitro minimum inhibitory activities of natural (+)-1 and (−)-1, against pathogenic Candida species.

| Fungal Strains | (+)-1 MIC (μg/ml)a | (−)-1 MIC (μg/ml)a |

|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans 96–489b | 55.7 | >128 |

| C. glabrata | 59.5 | >128 |

| C. albicans UCDFR1c | >128 | >128 |

| C. albicans ATCC 14503 | >128 | >128 |

| C. krusei | >128 | >128 |

Compounds tested as their free-bases. MIC defined as the lowest concentration eliciting 90% growth inhibition.

clinical isolate.

Fluconazole-resistant Candida strain raised from C. albicans ATCC 14503 by passage through sub-inhibitory Fluconazole. See Supporting Information for details of culture conditions.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (RO1 AI039987). We are grateful to Prof. T. M. Zabriskie (Oregon State University) and Prof. M. Burkart (UC San Diego) for helpful discussions. HRMS measurements were carried out by R. New (UC Riverside) and Y. X. Su (UCSD).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.He H, Silo-Suh LA, Handelsman J, Clardy J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:2499–2502.Silo-Suh LA, Lethbridge BJ, Raffel SJ, He H, Clardy J, Handelsman J. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2023–2030. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.2023-2030.1994.c) A partial relative configuration of (+)-1 was assigned based on alkali degradation, ref. 1b.

- 2.a) Silo-Suh LA, Stabb EV, Raffel SJ, Handelsman J. Curr Microbiol. 1998;37:6–11. doi: 10.1007/s002849900328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Broderick NA, Goodman RM, Raffa KF, Handelsman J. Environ Entomol. 2000;29:101–107. [Google Scholar]; c) Stohl EA, Brady SF, Clardy J, Handelsman J. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5455–5460. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5455-5460.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Liu C-L, MacMullan AM, Lufburrow PA, Starnes RL, Manker DC. US Patent 5,976,563. 1999 Nov 2;; b) Thomson JA. J Nut. 2008;132:3441S–3442S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3441S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Emmert EA, Kilmowicz AK, Thomas MG, Handelsman J. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:104–113. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.104-113.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stohl EA, Milner JL, Handelsman J. Gene. 1999;237:403–411. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chan YA, Boyne MT, Podevels AM, Klimowicz AK, Handelsman J, Kelleher NL, Thomas MG. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14349–14354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603748103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers EW, Molinski TF. Org Lett. 2007;9:437–440. doi: 10.1021/ol062804a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Hulme AN, Montgomery CH, Henderson DK. Chem Soc,Perkin Trans 1. 2000:1837–1841. [Google Scholar]; b) Laïb T, Chastanet J, Zhu J. J Org Chem. 1998;63:1709–1713. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stork G, Takahashi GT. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:1275–1276. doi: 10.1021/ja00446a055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The aldehyde obtained from 3 by direct oxidation proved to be highly prone to decomposition and unsuitable to carry forward.

- 9.Corey EJ, Nicolaou KC, Balanson RD, Machida Y. Synthesis. 1975:590–591. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Evans DA, Gage JR. Org Synth. 1990;68:83–87. [Google Scholar]; b) Hulme AN, Montgomery CH. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:7649–7653. [Google Scholar]

- 11.This ‘matched-case’ addition of a chiral glycolate equivalent 5 to 4 proved to be more efficient than the alternate substrate-controlled aldol addition of methyl benzyloxyacetate (44%, 37% de) (Evans DA, Britton TC, Ellman JA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:6141–6144.and subsequent saponification to give 6 (see Supporting Information).

- 12.Obtained in 2 steps from (−)-albizziin Denis J-N, Tchertchian S, Vallée Y. Synth Commun. 1997;27:2345–2350.

- 13.Boger DL, Yohannes D, Zhou J, Patane MA. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:3420–3430. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Short exposure time to HCl was critical to prevent hydrolysis of the internal amide bond.

- 15.We thank D. Manker (Novo Nordisk, Entotech, Inc, Davis, CA) for a gift of authentic (+)-1.

- 16.All NMR and optical rotations of 1 and 10 were recorded on the corresponding purified (HPLC) dihydrochloride salts (See Supporting Information). NMR spectra (D2O) were referenced to internal CH3CN set to δ2.06 and δ1.47 ppm for 1H and 13C, respectively ( Gottlieb HE, Kotlyar V, Nudelman A. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7512–7515. doi: 10.1021/jo971176v.

- 17.Teng H, He Y, Wu L, Su J, Feng X, Qiu G, Liang S, Hu X. SynLett. 2006:877–880. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Hoffmann K, Schneider-Scherzer E, Kleinkauf H, Zocher R. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12710–12714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Balibar CJ, Vaillancourt FH, Walsh CT. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1189–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yin X, Zabriskie TM. Microbiology. 2006;152:2969–2983. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.