Abstract

Objectives

Although women of Mexican decent have high rates of breastfeeding, these rates may vary considerably by acculturation level. This study investigated whether increased years of residence in the U.S. is associated with poorer breastfeeding practices, including shorter duration of any and exclusive breastfeeding, in a population of low-income mothers of Mexican descent.

Methods

Pregnant women (n=490) were recruited from prenatal clinics serving a predominantly Mexican-origin population in an agricultural region of California. Women were interviewed during pregnancy, shortly postpartum, and when their child was 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 3.5 years of age.

Results

Increased years of residence in the U.S. was associated with decreased likelihood of initiating breastfeeding and shorter duration of exclusive and any breastfeeding. Median duration of exclusive breastfeeding was 2 months for women living in the U.S. for 5 years or less, 1 month for women living in the U.S. for 6 to 10 years, and less than one week for women living in the U.S. for 11 years or more, or for their entire lives (lifetime residents). After controlling for maternal age, education, marital status and work status, lifetime residents of the U.S. were 2.4 times more likely to stop breastfeeding, and 1.5 times more likely to stop exclusive breastfeeding, than immigrants who had lived in the U.S. for 5 years or less.

Conclusions

Efforts are needed to encourage and support Mexican-origin women to maintain their cultural tradition of breastfeeding as they become more acculturated in the U.S.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, acculturation, Mexican Americans, Mexican immigrants, immigration

INTRODUCTION

The benefits of breastfeeding for both mother and infant are well established and human breastmilk is considered the best food for infants (1). The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life and continued breastfeeding with the addition of complementary foods for at least the first 12 months (1). Despite these recommendations, only 13% of infants in the U.S. are exclusively breastfed at 6 months of age and only 16% are still receiving any breastmilk at 1 year (2).

Breastfeeding rates differ markedly by race and ethnicity, with Whites and Hispanics being more likely to breastfeed than African-Americans (3). Breastfeeding rates among Hispanic women are close to the national average, with 73% of Hispanic mothers initiating breastfeeding compared to 69% of women of all races (4). However, these rates are significantly lower than rates of breastfeeding in Mexico, where the majority of the U.S. Hispanic population originated (5), and where 92% of mothers initiate breastfeeding and 31% are still breastfeeding their child at one year (6).

Acculturation in the U.S. may be associated with poorer breastfeeding practices. Studies have found that immigrant women who were born in Mexico are more likely to initiate breastfeeding in the hospital than their Mexican-American counterparts born in the U.S. (7-13). However, few studies have examined the effect of acculturation on duration of breastfeeding beyond the postpartum period. One study (14), found that Mexican immigrant mothers who had lived in the U.S. for 5 years or less were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding their child at age 16 weeks than immigrant women who had lived in the U.S. for more than 6 years. Another study using data from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HHANES) (15) found longer duration of any breastfeeding in children whose head of household self-identified as Mexican/Hispanic rather than Mexican-American/Chicano. However, this study was limited by scant information on maternal acculturation and poor recall of breastfeeding practices, since the children ranged up to 11 years of age at the time of the questionnaire.

The present study analyzes a prospective birth cohort of low-income mothers of Mexican descent in California to determine whether increased years of residence in the U.S. is associated with poorer breastfeeding practices, including shorter duration of exclusive breastfeeding and any breastfeeding.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study subjects were participants of the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS), a longitudinal birth cohort study of the effects of pesticides and other environmental exposures on the health of pregnant women and their children living in the Salinas Valley, an agricultural community in California. Pregnant women were recruited between October 1999 and October 2000 through a county hospital and five regional clinics that serve a predominantly Mexican immigrant population. Women were eligible to participate if they were less than 20 weeks gestation, 18 years or older, spoke English or Spanish, qualified for perinatal services through Medicaid, and planned to deliver at the county hospital. Women received $20 coupons for local stores upon completion of each interview and an infant car seat or stroller upon delivery. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the University of California, Berkeley.

Of 1130 eligible women, 601 agreed to participate in this multi-year study and 526 were followed through the birth of a liveborn, singleton infant. We restricted the present analysis to women of Mexican descent (n=499). An additional 9 women who were missing data on breastfeeding initiation were also excluded, leaving a final sample of 490 mothers.

Interviews were conducted with the participants twice during pregnancy (at the end of the first and second trimesters), immediately postpartum, and when the children were approximately 6, 12, 24, and 42 months old. Interviews were conducted in person, either at the study office or in a modified recreational vehicle (RV) that was used as a mobile office and parked at the participant’s home. All questionnaires were administered in English or Spanish by trained, bilingual, bicultural interviewers, with the majority of interviews (94%) conducted in Spanish. Study instruments were developed in English, translated by a professional translator, and validated by Mexican-American and Mexican immigrant staff members familiar with the language of the community and of southern Mexico from where many participants migrated.

Definition of Variables

The primary outcomes of interest were intention to breastfeed, initiation of breastfeeding, duration of exclusive breastfeeding, and duration of any breastfeeding. At the second pregnancy interview (mean = 27 weeks gestation), the participant was asked if she intended to breastfeed her child. At each of the postpartum, 6-, 12-, 24- and 42-month interviews, she was asked if she was currently breastfeeding. At the interview when the mother first answered that she was no longer breastfeeding, she was then asked the child’s age when she had completely stopped breastfeeding and the reasons for stopping. Additionally, at the 6-month interview, the mother was asked if her child was receiving formula, and if so, at what age formula had been introduced. At the 12-month interview, she was asked at what age formula, solid foods and cow’s milk were each introduced. Duration of exclusive breastfeeding was defined as the age when food or liquid other than breastmilk or water was first given. If a woman dropped from the study before she stopped breastfeeding, breastfeeding duration was censored at the child’s age at last interview (n=60).

Acculturation-related data was gathered at the first pregnancy interview. Women were asked their ethnic identification, their country of birth, and their parents’ countries of birth. They were also asked their first language spoken, the language spoken in their home, their age when they came to the U.S., and the total number of years residing in the U.S. The main independent variable in this analysis was the total number of years the mother had lived in the U.S. Most women in the study were born in Mexico (89%) and spoke Spanish at home (91%). Because there was little variability in these variables, years in the U.S. was used as a proxy measure for acculturation (16). Years residing in the U.S. was categorized as “5 years or less”, “6 to 10 years”, “11 years or more” and “entire life”. Entire life was defined as living at least 90% of one’s life in the U.S. and comprised 46 U.S.-born women, plus 2 women who were born in Mexico but had immigrated to the U.S. by one year of age. These categories were chosen based on previous literature (17, 18).

Information was also collected on other factors that might be associated with breastfeeding practices. Demographic information, gathered at the first pregnancy visit, included maternal age, parity, marital status, maternal education level and household income. Poverty-to-income ratio was calculated by dividing household income by the federal poverty threshold for a household of that size (19), with ratios less than 100% indicating that the family lived below the federal definition of poverty. Pregnancy-related variables, gathered from hospital delivery records, included infant sex and type of delivery (vaginal or cesarean). At each interview the mother was asked about all the jobs she had held since the previous interview, and mother’s work status variables (e.g. child’s age when she returned to work; whether she was working in agriculture) were also included in the analysis.

Data Analysis

Initial analyses used chi-square tests to compare breastfeeding practices by time in the U.S. Among women who initiated breastfeeding, multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were then used to determine the association between years in the U.S. and duration of exclusive breastfeeding and any breastfeeding, controlling for potential confounders. Most covariates were stable across time, however child’s age when mother started work was included in the Cox models as a dichotomous, time-varying covariate. All mothers were coded as “not working” at the beginning of the follow-up time, but this variable was changed to “working” at the child’s age when the mother returned to work. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to visually illustrate differences in breastfeeding duration by years in the U.S. These methods were chosen to account for the right-censored nature of some of the data and the positively skewed distribution of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding duration. All analyses were conducted in Stata 8.0 (20).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the study population. The median age of women in this study was 25 years old (range: 18-43). Two-thirds of participants were multiparous and 80% were living as married. More than half the participants had been living in the U.S. for 5 years or less. Almost 45% of participants had a sixth grade education or less and 63% had household incomes below the federal poverty threshold. Almost all participants earned below 200% of the federal poverty threshold. Forty-four percent of women resumed working when their child was 6 months old or younger and more than half of working mothers held jobs in agriculture. Twenty-three percent of births were by Cesarean delivery.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study population of women of Mexican descent living in the US. CHAMACOS Study, Salinas Valley, California, 2000-2001. (N = 490)

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age (years): | ||

| 18-24 | 234 (47.8) | |

| 25-29 | 147 (30.0) | |

| 30-34 | 75 (15.3) | |

| 35+ | 34 (6.9) | |

| Parity: | ||

| 0 | 167 (34.1) | |

| 1 | 149 (30.4) | |

| 2+ | 174 (35.5) | |

| Marital status: | ||

| Married/Living as married | 401 (81.8) | |

| Single | 89 (18.2) | |

| Maternal Education: | ||

| 6th grade or less | 219 (44.7) | |

| 7th through 12th grade | 184 (37.6) | |

| High school graduate | 87 (17.8) | |

| Family income: | ||

| At or below poverty level | 290 (62.8) | |

| Poverty level - 200% poverty level | 160 (34.6) | |

| Above 200% poverty level | 12 (2.6) | |

| Years residing in US: | ||

| ≤ 5 | 266 (54.3) | |

| 6-10 | 112 (22.9) | |

| ≥ 11 | 64 (13.1) | |

| Entire life | 48 (9.8) | |

| Child’s age when mother resumed working: | ||

| ≤ 6 months | 190 (43.7) | |

| 7-12 months | 87 (20.0) | |

| > 12 months | 158 (36.3) | |

| Mother’s type of work: | ||

| Agricultural work | 186 (40.9) | |

| Other work | 154 (33.8) | |

| No work | 115 (25.3) | |

| Cesarean Delivery: | ||

| No | 376 (76.7) | |

| Yes | 114 (23.3) |

Breastfeeding characteristics for this population are shown in Table 2. Overall, 96% of women initiated breastfeeding, with 23.7% exclusively breastfeeding at 4 months of age and 28.2% continuing to breastfeed at 1 year of age. Median duration of exclusive breastfeeding in this population was 1 month (range: 0-10 months) and median duration of any breastfeeding was 5 months (range: 0-44 months). Breastfeeding was initiated by 98% of women who said they intended to breastfeed and 59% of women who said they did not intend to breastfeed.

Table 2.

Breastfeeding characteristics by time in the United States among women of Mexican descent. CHAMACOS Study, Salinas Valley, California, 2000-2001

| Overall | ≤ 5 years | 6-10 years | 11+ years | Entire Life | χ2 p-value | χ2 trend p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intended to Breastfeeding (N(%)) | |||||||

| Yes | 441 (93.4) | 244 (94.6) | 103 (95.4) | 59 (92.2) | 35 (83.3) | ||

| No | 17 (3.6) | 7 (2.7) | 3 (2.8) | 3 (4.7) | 4 (9.5) | ||

| Don’t Know | 14 (3.0) | 7 (2.7) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (3.1) | 3 (7.1) | 0.20 | 0.38 |

| Initiated Breastfeeding (N(%)) | |||||||

| Yes | 471 (96.1) | 263 (98.9) | 108 (96.4) | 61 (95.3) | 39 (81.3) | ||

| No | 19 (3.9) | 3 (1.1) | 4 (3.6) | 3 (4.7) | 9 (18.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Exclusive Breastfeeding at 4 months (N(%)) | |||||||

| Yes | 104 (23.7) | 61 (26.9) | 24 (22.4) | 15 (25.0) | 4 (9.1) | ||

| No | 334 (76.3) | 166 (73.1) | 83 (77.6) | 45 (75.0) | 40 (90.9) | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| Any Breastfeeding at 6 months (N(%)) | |||||||

| Yes | 219 (49.4) | 129 (55.4) | 54 (50.9) | 26 (43.3) | 10 (22.7) | ||

| No | 224 (50.6) | 104 (44.6) | 52 (49.1) | 34 (56.7) | 34 (77.3) | <0.01 | <0.001 |

| Any Breastfeeding at 1 year (N(%)) | |||||||

| Yes | 123 (28.2) | 70 (31.1) | 34 (31.8) | 16 (26.7) | 3 (6.8) | ||

| No | 313 (71.8) | 155 (68.9) | 73 (68.2) | 44 (73.3) | 41 (93.2) | <0.01 | <0.001 |

Breastfeeding practices varied by time residing in the U.S. Table 2 shows that women who had lived their entire lives in the U.S. had the lowest rates of breastfeeding initiation while women who had lived in the U.S. for 5 years or less had the highest rates. The trend of decreasing initiation rates with each increasing category of time in the U.S. was statistically significant. Rates of breastfeeding at 6 or 12 months also decreased with time in the U.S., and again the trend was statistically significant. For all breastfeeding outcomes, lifetime residents of the U.S. had noticeably lower rates than immigrant women from Mexico.

Table 3 shows the hazard ratios for cessation of exclusive breastfeeding and any breastfeeding according to time residing in the U.S., controlling for other covariates. Among women who initiated breastfeeding, lifetime residents of the U.S. were 1.7 times as likely to stop exclusive breastfeeding and 2.6 times as likely to stop all breastfeeding at any given time than women who had lived in the U.S. for 5 years or less. Other factors associated with shorter duration of any breastfeeding were the mother returning to work and nulliparity. Mothers aged 35 years or older were likely to breastfeed for longer. Returning to work was associated with shorter duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Income-to-poverty ratio, cesarean delivery, and type of work were not associated with duration of exclusive or any breastfeeding and were not included in the final models.

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for cessation of exclusive breastfeeding and any breastfeeding among women of Mexican descent according to time in the United States and other predictors. CHAMACOS Study, Salinas Valley, California, 2000-2001

| Exclusive breastfeeding

|

Any breastfeeding

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Time residing in the U.S. | |||||

| 5 years or less | referent | referent | |||

| 6 - 10 years | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 0.99 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 0.73 | |

| 11 years or more | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 0.59 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 0.10 | |

| Entire life* | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | 0.01 | 2.6 (1.6, 4.0) | <0.001 | |

| Maternal age (years) | |||||

| 18-24 | referent | referent | |||

| 25-29 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 0.32 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.1) | 0.79 | |

| 30-34 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 0.07 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.3) | 0.62 | |

| 35+ | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | 0.66 | 0.6 (0.4, 1.0) | 0.03 | |

| Maternal education level | |||||

| Less than high school | referent | referent | |||

| High school | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.16 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.07 | |

| Parity | |||||

| 0 | referent | referent | |||

| 1 or more | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.42 | 0.7 (0.6, 0.9) | <0.01 | |

| Married/Living as Married | |||||

| No | referent | referent | |||

| Yes | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.16 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) | 0.58 | |

| Currently working | |||||

| No | referent | referent | |||

| Yes | 2.0 (1.4, 3.0) | <0.01 | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) | <0.01 | |

Lived in the U.S. for 90% of life or more

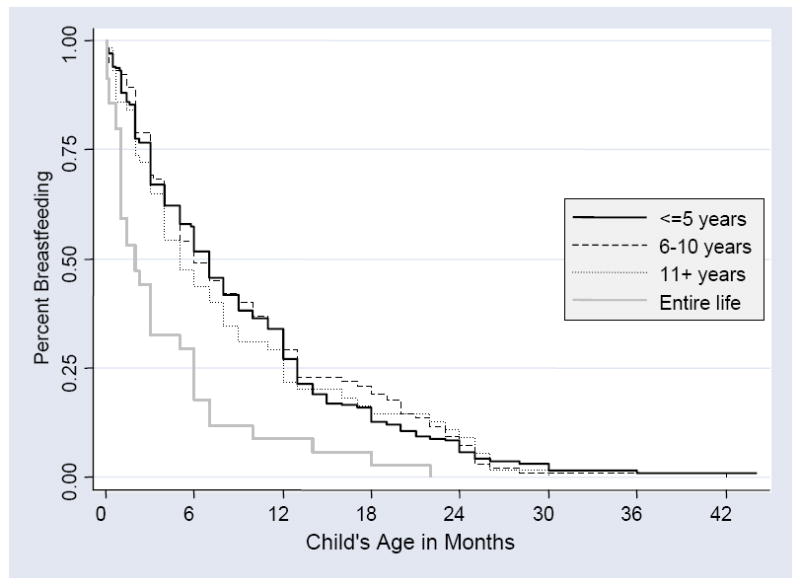

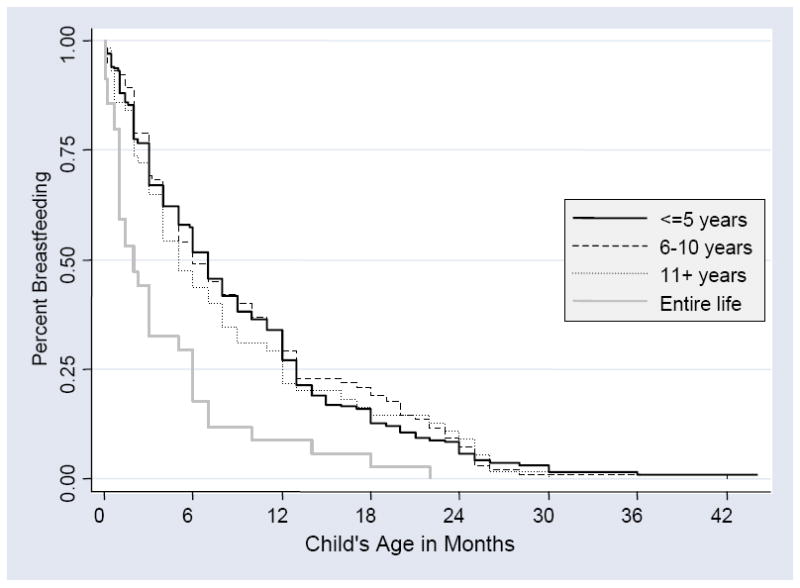

The findings in Table 3 are shown graphically in Figures 1 and 2. Figures 1 and 2 show a trend of decreasing duration of exclusive and any breastfeeding with increased time in the U.S. Figure 2, in particular, shows that women spending their entire lives in the U.S. had dramatically shorter duration of any breastfeeding than the other three groups. Additional Cox analyses using “entire life” as the referent, found that lifetime residents of the U.S. were significantly different than each of the other three groups with regard to duration of any breastfeeding (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Duration of exclusive breastfeeding among women of Mexican descent according to years of residence in the United States.

Figure 2.

Duration of breastfeeding among women of Mexican descent according to years of residence in the United States.

Figures 1 and 2 also show the median duration of breastfeeding, among women who initiated breastfeeding, in each group. Median duration of exclusive breastfeeding was 2 months for women living in the U.S. for 5 years or less, 1 month for women living in the U.S. for 6 to 10 years, and less than one week for women living in the U.S. for 11 years or more or for their entire lives. Median duration of any breastfeeding was 7 months for women living in the U.S. for 5 years or less, 6 months for women living in the U.S. for 6 to 10 years, 5 months for women living in the U.S. for 11 years or more, and 2 months for women living in the U.S. for their entire lives. The four main reasons given for stopping breastfeeding were: not enough breastmilk (37% of women), work reasons (28%), mother didn’t want to anymore (27%), and child didn’t want to anymore (15%). Other less common reasons included mother’s or doctor’s concern for the baby’s health (14%), illness of the mother (2%), separation of mother and child (2%), sore nipples (2%), the baby was biting (2%), and the baby was old enough to stop (2%). (Because women were allowed to give up to three reasons for stopping, the total was greater than 100%.) The reasons for stopping breastfeeding did not differ according to time in the U.S. or early versus late stopping.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of low-income women of Mexican descent living in a California agricultural community, increased years of residence in the U.S. was associated with decreased likelihood of initiating breastfeeding and shorter duration of exclusive and any breastfeeding. Although there was a trend toward shorter duration of breastfeeding across all four categories of time in the U.S., lifetime residents of the U.S. had appreciably poorer breastfeeding practices than the other three groups.

These results are consistent with other studies that show lower initiation of breastfeeding among U.S.-born Mexican-Americans compared to Mexico-born immigrants (7-11). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine duration of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding among Mexican-origin women by time in the U.S.

A number of differences exist between lifetime residents and more recent immigrants in this population. Lifetime residents were younger, more likely to be unmarried, and more likely to return to work before their child reached 4 months of age. However, differences in breastfeeding duration persisted even after controlling for these factors. A limitation of this study is that it did not gather information on spouse, family and friends’ attitudes and support of breastfeeding, as these social factors may also influence breastfeeding duration.

This study was conducted among low-income women in an agricultural community and the findings may not be generalizable to all women of Mexican origin in the U.S. The Salinas Valley has a very large Mexican immigrant community, based largely on agricultural work, and many of the towns in the region are more than 80% Hispanic (21). In general, levels of acculturation were low in our study population: even among women who had spent their entire lives in the U.S., 41% of women continued to speak mostly Spanish at home. Thus, additional studies are needed to confirm our findings in more acculturated populations. However, we expect the differences in breastfeeding practices that we observed with time in the U.S. would be even more pronounced among immigrants with higher levels of acculturation.

Overall, this population had healthy breastfeeding practices. The Healthy People 2010 goal is for 50% of infants to be breastfed at 6 months of age and 25% to be breastfed at 1 year of age (22) – a goal that was met in this population. National estimates put the rates of initiation of breastfeeding among Hispanics between 54% and 80% (3); in this study, 96% of women initiated breastfeeding. This high rate of breastfeeding initiation may be due, in part, to a strong effort on the part of the county hospital to encourage and support breastfeeding.

However, one group of women consistently failed to meet breastfeeding recommendations: Mexican-origin women who had lived their entire lives in the U.S. Despite very high rates of breastfeeding initiation in the hospital (83%), only 23% of women in this group were still breastfeeding at 6 months and only 7% were still breastfeeding at one year. Exclusive breastfeeding rates were similarly low, with only 9% of lifetime residents of the U.S. breastfeeding exclusively at 4 months, a level that was closer to the national rate for African-Americans (8.5%), the group with the lowest breastfeeding rates, than the national rate for Hispanics (20%)(3). Thus, although national data shows that Hispanic women as a group have good breastfeeding practices, our study suggests that these rates are likely to decline with increased years in the U.S. and that low-income women of Mexican descent who have lived in the U.S. for their entire lives are particularly at risk of poor breastfeeding practices. This negative trend is of clinical importance. The difference between exclusively breastfeeding an infant for 2 months (the median for women living in the U.S. for 5 years or less) versus for <1 week (the median for lifetime residents) is considerable. Likewise, the difference between continued breastfeeding for 7 months (5 years of less) versus 2 months (lifetime residents) is also large. Given the health benefits of breastfeeding to both mother and child, even a modest increase in overall duration has the potential to have significant public health impact.

The present study points to the need for culturally-appropriate interventions that promote breastfeeding among Mexican-American women who have lived in the U.S. for their entire life. In addition, it would be prudent to also direct efforts toward immigrant women from Mexico to encourage and support them to maintain their cultural tradition of breastfeeding as they become more acculturated in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant Numbers RD 83171001 from EPA and PO1 ES009605 from NIEHS.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li R, Darling N, Maurice E, Barker L, Grummer-Strawn LM. Breastfeeding rates in the United States by characteristics of the child, mother, or family: the 2002 National Immunization Survey. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e31–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newton ER. The epidemiology of breastfeeding. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;47:613–23. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000137068.00855.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan AS, Wenjun Z, Acosta A. Breastfeeding continues to increase into the new millennium. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1103–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzman B. The Hispanic Population: Census 2000 Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez-Cossio T, Moreno-Macias H, Rivera JA, et al. Breast-feeding practices in Mexico: results from the Second National Nutrition Survey 1999. Salud Publica Mex. 2003;45(Suppl 4):S477–89. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342003001000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd TL, Balcazar H, Hummer RA. Acculturation and breast-feeding intention and practice in Hispanic women on the US-Mexico border. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:72–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiemann CM, DuBois JC, Berenson AB. Racial/ethnic differences in the decision to breastfeed among adolescent mothers. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E11. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rassin DK, Markides KS, Baranowski T, Richardson CJ, Mikrut WD, Bee DE. Acculturation and the initiation of breastfeeding. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:739–46. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero-Gwynn E, Carias L. Breast-feeding intentions and practice among Hispanic mothers in southern California. Pediatrics. 1989;84:626–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scrimshaw SC, Engle PL, Arnold L, Haynes K. Factors affecting breastfeeding among women of Mexican origin or descent in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:467–70. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.4.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celi AC, Rich-Edwards JW, Richardson MK, Kleinman KP, Gillman MW. Immigration, race/ethnicity, and social and economic factors as predictors of breastfeeding initiation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:255–60. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heck KE, Braveman P, Cubbin C, Chavez GF, Kiely JL. Socioeconomic status and breastfeeding initiation among California mothers. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:51–9. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guendelman S, Siega-Riz A. Infant feeding practices and maternal dietary intake among Latino immigrants in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2002;4:137–146. doi: 10.1023/A:1015698817387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John AM, Martorell R. Incidence and duration of breast-feeding in Mexican-American infants, 1970-1982. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:868–74. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.4.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arcia E, Skinner M, Bailey D, Correa V. Models of acculturation and health behaviors among Latino immigrants to the US. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:41–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guendelman S, English PB. Effect of United States residence on birth outcomes among Mexican immigrants: an exploratory study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;142:S30–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/142.supplement_9.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harley K, Eskenazi B, Block G. The association of time in the US and diet during pregnancy in low-income women of Mexican descent. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:125–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Bureau of the Census. Poverty Thresholds 2000, Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 8.0. 8.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Census Bureau. State and County QuickFacts [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010, Objectives for Improving Health. 2. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; [Google Scholar]