SUMMARY

Autophagy dysfunction has been implicated in misfolded protein accumulation and cellular toxicity in several diseases. Whether alterations in autophagy also contribute to the pathology of lipid storage disorders is not clear. Here we show defective autophagy in Niemann-Pick type C1 (NPC1) disease associated with cholesterol accumulation, where maturation of autophagosomes is impaired due to defective amphisome formation caused by failure in SNARE machinery, whilst the lysosomal proteolytic function remains unaffected. Expression of functional NPC1 protein rescues this defect. Inhibition of autophagy also causes cholesterol accumulation. Compromised autophagy was seen in disease-affected organs of Npc1 mutant mice. Of potential therapeutic relevance is that HP-β-cyclodextrin, which is used for cholesterol depletion treatment, impedes autophagy, whereas stimulating autophagy restores its function independent of amphisome formation. Our data suggest that a low dose of HP-β-cyclodextrin that does not perturb autophagy, coupled with an autophagy inducer, may provide a rational treatment strategy for NPC1 disease.

Keywords: Autophagy, Niemann-Pick type C1 disease, Cholesterol, Autophagy enhancer, Lipid storage disorder, Lysosomal storage disorder, Neurodegeneration

INTRODUCTION

Autophagy, an intracellular degradation pathway for aggregation–prone proteins and damaged organelles, is essential for cellular homeostasis. This dynamic process, defined as autophagic flux, encompasses the generation of autophagosomes and its fusion with late endosomes to form amphisomes, which subsequently fuse with lysosomes forming autolysosomes for degrading its cargo (Figure S1A). Starvation induces autophagy for maintaining energy homeostasis by recycling of cytosolic components (Ravikumar et al., 2010). Tissue–specific abrogation of constitutive autophagy, such as by deletion of essential autophagy genes Atg5 or Atg7, in the brain or liver of mice in the absence of any pathogenic protein results in degeneration in the affected organs, suggesting that impaired autophagy contributes to the disease related phenotypes in neurodegenerative and liver diseases (Hara et al., 2006; Komatsu et al., 2006; Komatsu et al., 2007). Thus, compromised autophagy is attributable to the etiology of several neurodegenerative disorders and certain liver diseases where upregulation of autophagy is considered beneficial (Meijer and Codogno, 2006; Mizushima et al., 2008; Rubinsztein et al., 2012; Sarkar, 2013).

Autophagy also regulates metabolism of lipids including cholesterol (Singh et al., 2009), which are essential structural components of membranes and govern intracellular trafficking (Ikonen, 2008). Niemann–Pick type C1 (NPC1) disease, associated with neurodegeneration and liver dysfunction, is characterized by cholesterol accumulation in the late endosomal/lysosomal (LE/L) compartments resulting from disease–causing mutations primarily in the NPC1 protein (Karten et al., 2009; Rosenbaum and Maxfield, 2011). The transmembrane NPC1 protein comprises of five sterol–sensing domains, possibly mediating cholesterol efflux from late endosomes (Higgins et al., 1999; Kwon et al., 2009). How alterations in cholesterol homeostasis in lipid storage disorders might perturb autophagy is not completely understood. Here we show defective autophagic flux in NPC1 disease, in which stimulation of autophagy restores the function of the pathway.

RESULTS

Accumulation of autophagosomes in NPC1 mutant cells is due to a block in autophagic flux

We initially confirmed accumulation of cholesterol and lipids by Filipin and BODIPY staining in NPC1 patient fibroblasts, in Npc1−/− MEFs from npc1nih mutant mice exhibiting NPC1 clinical abnormalities (Loftus et al., 1997), and in Chinese hamster ovary-K1 (CHO-K1) cells containing a deletion in the Npc1 locus (Npc1null) (Millard et al., 2000) (Figures 1A and S1B). In these NPC1 mutant cells, the NPC1 protein was either low or not detected (Figure S1C). Perturbation in autophagy was measured by the steady–state number of autophagosomes, which correlates with the autophagosome–associated form of microtubule–associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3-II) (Kabeya et al., 2000; Klionsky et al., 2012). We found accumulation of autophagosomes in the NPC1 mutant cells, as assessed by elevated LC3-II levels and LC3+ vesicles, including autophagic vacuoles analyzed by electron microscopy (Figures 1B, C and S1C–F). Previous studies have attributed this increase in the steady–state number of autophagosomes in NPC1 disease to activation of autophagy (Ishibashi et al., 2009; Ordonez et al., 2012; Pacheco et al., 2007). Since both synthesis and degradation affect steady–state LC3-II levels we determined autophagic flux using bafilomycin A1 (bafA1), which prevents lysosomal acidification and accumulates LC3-II by inhibiting its degradation. In bafA1–treated conditions, an autophagy inducer increases LC3-II levels whereas an autophagy blocker has no change compared to controls (Klionsky et al., 2012; Sarkar et al., 2009) (see Supplementary Information). Despite significant LC3-II accumulation in NPC1 mutant cells compared to controls, this difference was no longer detected following bafA1 treatment (Figure 1D). Thus, in contrast to previous studies (Ishibashi et al., 2009; Ordonez et al., 2012; Pacheco et al., 2007), our data suggest that LC3-II accumulation is not due to increased autophagosome synthesis but rather is caused by impaired degradation of autophagosomes.

Figure 1. Accumulation of autophagosomes in NPC1 mutant cells is due to a block in autophagic flux.

(A and B) Filipin and BODIPY fluorescence staining (A) and immunofluorescence staining with anti-LC3 antibody (B) in control and NPC1 patient fibroblasts, Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, and in Npc1wt and Npc1null CHO-K1 cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. See also Figure S1D.

(C) Electron microscopy images and quantification of autophagic vacuoles (AVs) in control and NPC1 patient fibroblasts, and in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs. Scale bar, 500 nm. See also Figures S1E,F.

(D) Immunoblot analyses with anti-LC3 and anti-actin antibodies in control and NPC1 patient fibroblasts, Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, and in Npc1wt and Npc1null CHO-K1 cells treated with or without 400 nM bafilomycin A1 (Baf) for 4 h. High (HE) and low exposures (LE) of the same immunoblot are shown.

(E) GO enrichments among differentially expressed genes with enriched abundance in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs that have GO annotations linking them to autophagy (blue), the lysosomal (green) and the endosomal system (orange).

(F) Immunoblot analyses with anti-NPC1, anti-Rab7, anti-M6PR, anti-VAMP8, anti-VAMP7, anti-VAMP3 and anti-actin antibodies in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs. See also Figure S1I.

(G) Immunofluorescence staining with anti-Rab7, anti-tubulin, anti-M6PR and anti-LBPA antibodies in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Graphical data denote mean ± SEM. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ns, non-significant.

Defective amphisome formation in NPC1 mutant cells due to impaired recruitment of components of the SNARE machinery to late endosomes

To gain mechanistic insights, we performed mass spectrometry (MS) analyses in Npc1 MEFs. Gene Ontology (GO) annotations indicated changes in intracellular transport in Npc1−/− MEFs when compared to Npc1+/+ MEFs (Figures S1G, H). We analyzed genes with a significant difference in expression levels and GO annotations linked to autophagy, endocytosis or lysosomes (Figure 1E). For example, Rab7, a late endosome–resident GTPase regulating endosomal/autophagosomal maturation (Jager et al., 2004; Stenmark, 2009), was enriched in Npc1−/− MEFs. We confirmed an elevation of Rab7, and other late endosome markers, such as cation independent mannose–6–phosphate receptor (M6PR) and lysobisphosphatidic acid (LBPA) (Kobayashi et al., 1999), suggesting accumulation of late endosomes in NPC1 mutant cells (Figures 1E–G and S1I, J).

Since loss of NPC1 protein from LE/L compartments in NPC1 mutant cells (Carstea et al., 1997; Higgins et al., 1999; Karten et al., 2009) leads to increase in autophagosomes (LC3+) and late endosomes (Rab7+), we investigated the formation of amphisomes arising due to fusion of these vesicular compartments (Berg et al., 1998). While starvation increases their number in control cells (Jager et al., 2004), EGFP-LC3+/mRFP-Rab7+ amphisomes were significantly reduced in Npc1−/− MEFs both under basal (full medium; FM) and starvation (HBSS) conditions (Figures 2A and S2A), suggesting impaired formation of amphisome in NPC1 mutant cells. Further analyzing this process with endogenous LC3+ and Rab7+ vesicles revealed a similar defect in starved Npc1−/− MEFs (Figure S2B). Additionally, using FITC–conjugated Dextran that undergoes cellular uptake through the endocytic pathway, NPC1 mutant cells exhibited significantly less amphisomes as assessed by FITC–Dextran+/mRFP-LC3+ colocalization (Figure 2B and S2C).

Figure 2. Perturbation of SNARE machinery on late endosomes impairs amphisome formation in NPC1 mutant cells.

(A) Fluorescence staining and quantification of colocalization of mRFP-Rab7+ and EGFP-LC3+ vesicles (an indication of amphisome formation) in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing mRFP-Rab7 and EGFP-LC3 for 24 h and cultured under basal (full medium, FM) and starvation (HBSS; last 1 h) conditions. Scale bar, 10 μm. See also Figure S2A.

(B) Fluorescence staining and quantification of colocalization of mRFP-LC3+ and FITC–Dextran+ structures in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing mRFP-LC3 for 24 h and then incubated in HBSS with Alexa Fluor 488 (FITC)–conjugated Dextran for 15 or 30 min. Scale bar, 10 μm. See also Figure S2C.

(C) Co-immunoprecipitation of Flag-Vamp8 and Myc-Syntaxin17 (Stx17) in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing Myc-Syntaxin17 and either empty vector or Flag-VAMP8 for 24 h, then lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag beads. Immunoblotting analysis with anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies was done on inputs (with equal loading) and immunoprecipitated fractions.

(D) Fluorescence staining and quantification of colocalization of Flag-VAMP8+ and Myc-Syntaxin17+ (Stx17) structures in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing Flag-VAMP8 and Myc-Syntaxin17 for 24 h under basal (full medium, FM) and starvation (HBSS; last 1 h) conditions. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E and F) Fluorescence staining and quantification of colocalization of Flag-VAMP8+ (E) or EGFP-VAMP3+ (F) structures with mRFP-Rab7+ vesicles in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing mRFP-Rab7 and either Flag-VAMP8 (E) or EGFP-VAMP3 (F) for 24 h. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(G) Immunofluorescence staining with anti-Rab7 antibody and quantification of colocalization of Rab7+ and Myc-Syntaxin17+ (Stx17) structures in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing Myc-Syntaxin17 for 24 h and then starved in HBSS for last 1 h. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Graphical data denote mean ± SEM. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ns, non-significant.

The defect in autophagosome–late endosome fusion could be due to perturbations in the formation of specific SNARE complexes, such as between autophagosomal syntaxin 17 (Stx17) and LE/L VAMP8 mediated by SNAP-29 (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). Despite an increase in VAMP8 levels in Npc1−/− MEFs, as revealed by MS data (Figures 1E, F and S1I), the fusion between Myc-Stx17+ autophagosomes and Flag-VAMP8+ vesicles, as well as co-immunoprecipitation between these SNARE proteins, were significantly decreased both under basal and starvation conditions as compared to Npc1+/+ MEFs (Figures 2C, D). We found impaired localization of VAMP8 to mRFP-Rab7+ late endosomes in Npc1−/− MEFs, possibly contributing to this defect in forming SNARE complex (Figures 2E and S2D). Other SNARE proteins implicated in autophagosomes maturation includes VAMP3 (regulates amphisome formation) and VAMP7 (regulates fusion with lysosomes) (Fader et al., 2009), which were elevated in Npc1−/− MEFs (Figures 1F and S1I). Similar to VAMP8, localization of EGFP-VAMP3, but not of EGFP-VAMP7, to mRFP-Rab7+ late endosomes was reduced in Npc1−/− MEFs (Figures 2F and S2E). Consistently, the localization of autophagosomal Myc-Stx17+ to late endocytic Rab7+ vesicles, which is an indication of amphisome formation during starvation as seen in Npc1+/+ MEFs, was significantly reduced in Npc1−/− MEFs (Figures 2G and S2F). Thus, inability to recruit multiple components of the SNARE machinery to late endosomes in NPC1 mutant cells impairs amphisome formation.

Impaired autophagosome maturation in NPC1 mutant cells retards autophagic cargo clearance

Defective amphisome formation will affect the maturation of autophagosomes into autolysosomes. We analyzed this process using tandem–fluorescent–tagged–mRFP-GFP-LC3 reporter where autophagosomes emit both mRFP/GFP signals but autolysosomes emit only an acid–stable mRFP signal because the pH–sensitive GFP signal is quenched in acidic lysosomes (Kimura et al., 2007). Unlike control cells displaying autolysosomes (mRFP+-GFP−-LC3), the majority of accumulated vesicles in NPC1 mutant cells were autophagosomes (mRFP+-GFP+-LC3) (Figures 3A and S3A), suggesting a defect in autophagosome maturation. Consequently, the clearance of p62, a specific autophagy substrate (Pankiv et al., 2007), was decreased in NPC1 mutant cells, leading to its accumulation and aggregation that co-stained with LC3+ vesicles (Figures 3B, C and S3B, C). Using tandem–fluorescent–tagged mCherry-GFP-p62 reporter (Pankiv et al., 2007), we found that the majority of p62 aggregates in Npc1−/− MEFs were autophagosome–associated (mCherry+-GFP+-p62), in contrast to those in controls that were mostly autolysosome associated (mCherry+-GFP−-p62 aggregates) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Impaired autophagosome maturation retards autophagic cargo clearance in NPC1 mutant cells that are associated with defective mitophagy, whereas lysosomal proteolysis is not perturbed.

(A) Fluorescence staining and quantification of autophagosomes (mRFP+-GFP+-LC3) and autolysosomes (mRFP+-GFP -LC3) in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3 reporter for 24 h. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(B) Immunofluorescence staining with anti-p62 antibody and quantification of the percentage of cells exhibiting increased p62+ aggregates in control and NPC1 patient fibroblasts, and in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs. Scale bar, 10 μm. See also Figure S3B.

(C) Immunoblot analysis with anti-p62 and anti-actin antibodies in control and NPC1 patient fibroblasts, and in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs.

(D) Fluorescence staining and quantification of autophagosome (AP)–associated (mCherry+-GFP+-p62) and autolysosome (AL)–associated (mCherry+-GFP−-p62) p62 aggregates in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing mCherry-GFP-p62 reporter for 24 h. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) Immunoblot analysis with anti-p62 and anti-actin antibodies in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, treated with or without 20 μg.mL−1 cycloheximide (CHX) for 4, 8, 12 and 24 h.

(F) Immunoblot analyses with anti-DJ-1, anti-Tom20 and anti-actin antibodies in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs.

(G) Cell viability and apoptosis analysis with FITC Annexin V and propidium iodide detection by FACS in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, treated with or without 10 μM CCCP for 18 h.

(H) Fluorescence staining and quantification of FITC–Dextran+ and LysoTracker+ structures, and their colocalization in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 (FITC)–conjugated Dextran for 3 h followed by LysoTracker staining for 1 h. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(I) Immunoblot analyses with anti-cathepsin B, anti-cathepsin D and anti-actin antibodies in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs.

(J) Immunofluorescence staining with anti-LAMP1 antibody in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(K) Cathepsin B activity in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, and in control and NPC1 patient fibroblasts. Cathepsin B activity is represented as μmole free cathepsin B substrate (AMC) per μg of total protein per 30 min.

Graphical data denote mean ± SEM. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ns, non-significant.

Although the levels of p62 in Npc1−/− MEFs were comparable to that in autophagy deficient Atg5−/− MEFs (Figure S3D) that do not have autophagosomes/LC3-II (Kuma et al., treatment further increased p62 levels in Npc1−/− MEFs (Figure S3E). Moreover, the 2004), bafA1 kinetics of endogenous p62 degradation in the presence of cycloheximide (inhibits protein translation) was substantially slower in Npc1−/− MEFs compared to Npc1+/+ MEFs, whereas no clearance of p62 occurred in Atg5−/− MEFs (Figures 3E and S3F). These data suggest that the impairment in autophagic flux in NPC1 mutant cells is not absolute.

Consistent with effects that are associated with autophagy impairment, aggregation of mutant huntingtin (EGFP-HDQ74), an autophagy substrate (Ravikumar et al., 2004), and ubiquitylated proteins (Korolchuk et al., 2009) were increased in NPC1 mutant cells (Figures S3G, H). Autophagy also removes damaged mitochondria (mitophagy) (Youle and Narendra, 2011). Defective autophagy in Npc1−/− MEFs increased mitochondrial load, as assessed by elevated levels of Tom20, a translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane (Figure 3F). Furthermore, the MS data revealing decreased DJ-1 levels were confirmed in NPC1 mutant cells (Figures 1E, 3F and S3I), an effect associated with mitochondrial fragmentation and accumulation of autophagosomes (Thomas et al., 2011). Indeed, NPC1 knockdown causes mitochondrial fragmentation (Ordonez et al., 2012), which we verified in Npc1−/− MEFs (Figure S3J). Our data link NPC1 deficiency to defective mitophagy, a phenomenon linked to increased susceptibility to pro-apoptotic insults (Ravikumar et al., 2006; Youle and Narendra, 2011). Consequently, treatment with carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), an uncoupler of mitochondrial membrane potential, substantially increased cell death in Npc1−/− MEFs compared to Npc1+/+ MEFs (Figure 3G).

Upstream events regulating autophagosome biogenesis (Ravikumar et al., 2010), such as Atg5–Atg12 conjugation and phagophore formation (Atg16+ vesicles), including beclin 1 and mTOR activity remained constant (Figures S1A and S3K–M). Thus, contrary to previous reports suggesting autophagy activation in NPC1 disease (Ishibashi et al., 2009; Ordonez et al., 2012; Pacheco et al., 2007), our data are consistent with autophagosome accumulation being due to a block in autophagic flux late in the pathway.

NPC1 mutant cells exhibit no overt defects in endocytic cargo degradation and lysosomal hydrolytic function

Since NPC1 mutant cells exhibit accumulation of late endosomes, we examined any perturbations in endocytic traffic by the uptake of FITC–Dextran and its colocalization to LysoTracker+ LE/L compartments. Although FITC–Dextran and LysoTracker+ vesicles accumulated in Npc1−/− MEFs, the fraction localizing with LysoTracker+ vesicles was comparable with the control cells (Figure 3H). We assessed clathrin mediated endocytic degradation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Despite elevated EGFR levels in NPC1 mutant cells, the rate of EGF–induced EGFR degradation was comparable to that of control cells (Figure S3N), suggesting that endocytic trafficking and lysosomal proteolysis are not compromised. Consistent with data in Npc1−/− mice brain (Sleat et al., 2012), we confirmed increased LAMP1, and mature cathepsin B and cathepsin D levels as revealed by MS data, suggesting an accumulation of lysosomes and lysosomal proteases (Figures 1E, 3I and 3J). Furthermore, cathepsin B activity was increased in Npc1−/− MEFs although no significant alterations were found in NPC1 patient fibroblasts, compared to the respective control cells (Figure 3K). In contrast to earlier report attributing impaired cathepsin activation to autophagy deregulation (Elrick et al., 2012), our data imply no obvious impairment in the lysosomal proteolytic function.

Functional NPC1 protein rescues the autophagy defects in NPC1 mutant cells whereas cholesterol depletion treatment with HP-β-cyclodextrin blocks autophagic flux

Expression of functional NPC1 protein corrected the cholesterol phenotype in NPC1 mutant cells (Carstea et al., 1997). We found that overexpression of NPC1-EGFP in Npc1−/− MEFs also rescued the autophagy defects, as assessed by a reduction in p62 and LC3-II levels, and clearance of p62+ aggregates, LC3+ and LysoTracker+ vesicles when compared to EGFP–transfected mutant cells (Figures 4A–C and S4A). Consistent with NPC1 protein mediating vesicular traffic, transient expression of NPC1-EGFP that partially colocalized with mRFP-LC3+ vesicles subtly increased autophagosome synthesis, as measured by increased LC3-II levels with or without bafA1 (Figures S4B, C). This is likely due to a compensatory signal sensing NPC1 protein mediated increased autophagic flux causing rapid clearance of autophagosomes.

Figure 4. Rescue of autophagy defects in NPC1 mutant cells by expressing functional NPC1 protein, whereas cholesterol depletion treatment blocks autophagic flux.

(A) Immunoblot analyses with anti-p62, anti-LC3, anti-NPC1, anti-EGFP and anti-actin antibodies in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing either EGFP or NPC1-EGFP for 48 h.

(B and C) Immunofluorescence staining with anti-p62 (B) and anti-LC3 (C) antibodies, and quantification of cells exhibiting accumulated p62+ aggregates (B) and LC3+ vesicles (C) in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing either EGFP or NPC1-EGFP for 48 h. Arrows (white) show transfected cells whereas arrowhead (orange) denotes a non-transfected cell. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D and E) Filipin staining (D) and quantification of Filipin intensity (E) in Npc1−/− MEFs, either left untreated or treated with 0.1–4% HP-β-cyclodextrin for 24 h. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(F) Immunoblot analysis with anti-LC3, anti-p62 and anti-actin antibodies in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, treated with or without 0.1–4% HP-β-cyclodextrin for 24 h. Low exposures of immunoblots were shown to visualize changes in LC3-II and p62 levels. See also Figure S4E.

(G) Immunoblot analysis with anti-LC3, anti-p62 and anti-actin antibodies in rat primary cortical neurons, treated with or without 1% and 4% HP-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) for 96 h. See also Figure S4H.

(H) Immunoblot analysis with anti-LC3 and anti-actin antibodies in rat primary cortical neurons, treated with or without 1% HP-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) for 96 h, in the presence or absence of 400 nM bafilomycin A1 (Baf) for the last 4 h.

(I) Fluorescence staining and quantification of autophagosomes (mRFP-LC3+/GFP-LC3+) and autolysosomes (mRFP-LC3+/GFP-LC3 ) in MEFs, expressing mRFP-EGFP-LC3 reporter for 24 h and treated with or without 1% HP-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) for 24 h.

(J) Immunoblot analysis with anti-LC3, anti-p62 and anti-actin antibodies in Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs, treated with or without 1% HP-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) for 24 h.

Graphical data denote mean ± SEM. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ns, non-significant.

Cholesterol depletion treatment with HP-β-cyclodextrin is a potential therapeutic strategy for NPC1 disease (Rosenbaum and Maxfield, 2011). We assessed whether this could also rescue the autophagy defects. Despite HP-β-cyclodextrin causing a dose–dependent reduction in cholesterol accumulation (Filipin staining) in Npc1−/− MEFs, it impaired autophagy, leading to dose– and time–dependent elevation in autophagosome/LC3-II and p62 levels (Figures 4D–F and S4D–G). Similar results were obtained with 1% and 4% HP-β-cyclodextrin in rat primary cortical neurons (Figures 4G and S4H). Impairment of autophagy by HP-β-cyclodextrin is caused by inhibition autophagosome maturation, causing a block in autophagic flux as analyzed with the mRFP-GFP-LC3 reporter and bafA1 assay (Figures 4H, I and S4I). Low doses of HP-β-cyclodextrin, sufficient to deplete cholesterol, had lesser impact on autophagy (Figures 4D–F and S4E, F, G). HP-β-cyclodextrin–mediated accumulation of p62 was autophagy–dependent since it had no effects in autophagy deficient Atg5−/− MEFs (Figure 4J). However, endocytosis–mediated EGFR degradation remained unaffected, indicating that endosomal maturation and lysosomal proteolysis are not perturbed (Figure S4J). Thus, apart from NPC1 mutations causing cholesterol accumulation, substantial depletion of cholesterol also impairs autophagy possibly due to changes in membrane lipid composition retarding the vesicle fusion events (Koga et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2009). We infer a role for NPC1 protein in mediating autophagic traffic independently of its effect on cholesterol handling.

Stimulation of autophagy in NPC1 mutant cells facilitates autophagosome maturation and autophagic cargo clearance independent of amphisome formation

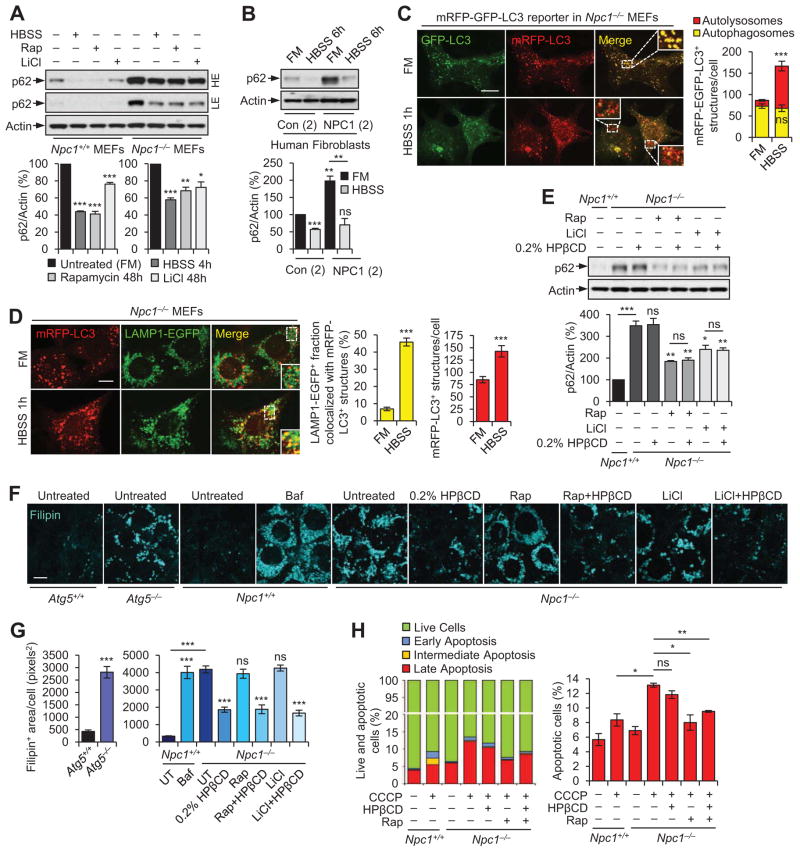

Upregulation of autophagy is beneficial in several neurodegenerative diseases (Ravikumar et al., 2004; Rubinsztein et al., 2012; Sarkar, 2013; Sarkar et al., 2007). Using mTOR–dependent (starvation, rapamycin) and mTOR–independent (lithium) autophagy enhancers (Ravikumar et al., 2004; Sarkar et al., 2005), we assessed whether this approach will be rational in NPC1 disease context, and if autophagic flux can be restored in NPC1 mutant cells by measuring p62 clearance. Stimulating autophagy significantly reduced p62 and LC3-II/autophagosome levels in NPC1 mutant cells as a result of an increased autophagic flux (Figures 5A, B and S5A–C). Restoration of functional autophagy under starvation in Npc1−/− MEFs is due to increased autophagosome maturation, as assessed with mRFP-GFP-LC3 reporter (Figure 5C). However, this process was independent of amphisome formation as indicated by reduced colocalization of LC3+ and Rab7+ vesicles, in contrast to starved Npc1+/+ MEFs (Figures 2A, S2A, B and S5D). Likewise, starvation or rapamycin reduced p62 levels in Npc1−/− MEFs with siRNA knockdown of VAMP8 (Figure S5E), which mediates amphisome formation (Itakura et al., 2012). Instead, autophagosomes possibly fused directly with the lysosomes during starvation–induced autophagy in Npc1−/− MEFs, as evident from increased colocalization between mRFP-LC3+ and LAMP1-EGFP+ vesicles (Figure 5D). Thus, stimulating autophagy could bypass the amphisome–forming vesicle fusion step to enable cargo clearance.

Figure 5. Simulating autophagy rescues autophagy defects in NPC1 mutant cells by facilitating autophagosome maturation independent of amphisome formation, whereas abrogation of autophagy leads to accumulation of intracellular cholesterol.

(A) Immunoblot analysis with anti-p62 and anti-actin antibodies in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, cultured in full medium (FM) with or without 400 nM rapamycin (Rap) or 10 mM lithium (LiCl) for 48 h, or under starvation condition (HBSS; last 4 h). High exposure (HE) and low exposure (LE) of the same immunoblot are shown.

(B) Immunoblot analysis with anti-p62 and anti-actin antibodies in control and NPC1 patient fibroblasts, cultured either in basal (full medium; FM) or starvation (HBSS; 6 h) condition.

(C) Fluorescence staining and quantification of autophagosomes (mRFP+-GFP+-LC3) and autolysosomes (mRFP+-GFP -LC3) in Npc1−/− MEFs, expressing mRFP-EGFP-LC3 reporter for 24 h and cultured under basal (full medium, FM) or starvation (HBSS; last 1 h) conditions. Cells were subjected to starvation for 1 h to visualize LC3+ vesicles, instead of 4 h where there was a substantial clearance of these vesicles (Figures S5B,C). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D) Fluorescence staining and quantification of mRFP-LC3+ vesicles and their colocalization with LAMP1-EGFP+ structures in NPC1−/− MEFs expressing mRFP-LC3 and LAMP1-EGFP for 24 h, cultured either in basal (full medium; FM) or starvation (HBSS; last 1 h) condition. Cells were subjected to starvation induced autophagy for 1 h as explained above. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) Immunoblot analysis with anti-p62 and anti-actin antibodies in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, where Npc1−/− MEFs were treated with or without 400 nM rapamycin (Rap) or 10 mM lithium (LiCl) for 48 h, in the presence or absence of 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) for last 24 h.

(F and G) Filipin staining (F) and quantification of Filipin intensity (G) in Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs, Npc1+/+ (Baf; 24 h), and in Npc1−/− MEFs treated with or without 400 nM bafilomycin A1MEFs, either left untreated (UT) or treated with 200 nM rapamycin (Rap; 48 h), 10 mM lithium (LiCl, 48 h), 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD; 24 h) or a combination of compounds as indicated. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(H) Cell viability and apoptosis analysis with FITC–Annexin V and propidium iodide detection by FACS in Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs, treated with or without 200 nM rapamycin (Rap), 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) or both for 48 h, in the presence or absence of 10 μM CCCP for last 18 h.

Graphical data denote mean ± SEM. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ns, non-significant.

Starvation–induced autophagy also lowered p62 accumulation in Npc1−/− MEFs treated with a high dose (4%) of HP-β-cyclodextrin (Figures S5F, G) (depleted cholesterol by 85–90% but further blocked autophagy; Figures 4D–G and S4D–I), suggesting that combining a lower dose with autophagy enhancers may be rational to rescue both the cholesterol and autophagy defects. Indeed, Npc1−/− MEFs treated with 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin (depleted cholesterol by 40–50% but not affecting autophagy; Figures 4D–F and S4E, F, G) and rapamycin or lithium significantly reduced p62 levels in the presence of HP-β-cyclodextrin (Figure 5E).

Inhibition of autophagy causes cholesterol accumulation whereas inducing autophagy increases cell viability in NPC1 mutant cells without affecting cholesterol levels

Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism since abrogation of autophagy increases intracellular lipids in autophagy–deficient (Atg5−/− ) cells (Singh et al., 2009). We found that accumulation of cholesterol (Filipin staining) also occurred in Atg5−/− MEFs as well as in bafA1–treated Npc1+/+ MEFs, similar to the effects arising due to loss of NPC1 protein in Npc1−/− MEFs (Figures 5F, G). Although 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin reduced cholesterol accumulation in Npc1−/− MEFs, stimulation of autophagy with rapamycin or lithium had no significant effects. Combining 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin with these autophagy inducers reduced cholesterol to what could be achieved with HP-β-cyclodextrin alone (Figures 5F, G). These data suggest that while inhibition of autophagy exhibits an NPC1–like cholesterol phenotype, activating autophagy in the context of NPC1 disease was unable to lower cholesterol levels.

We further examined the effects of HP-β-cyclodextrin and rapamycin on cellular viability in CCCP treated Npc1−/− MEFs, which were more susceptible to apoptotic insults compared to Npc1+/+ MEFs (Figures 3G and 5H). Although rapamycin, either alone or in combination with 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin significantly rescued from cell death, 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin had no significant protective effects in Npc1−/− MEFs (Figure 5H). Our data thus raise the possibility of activation of autophagy as a therapeutic strategy.

Defective autophagic flux in vivo in cerebellum and liver of Npc1−/− mice

Finally, we characterized defective autophagy in the organs primarily affected in NPC1 disease using cerebellum and liver from Npc1−/− mice (Loftus et al., 1997), where LC3-II and p62 levels were significantly elevated, thus confirming a block in autophagic flux in vivo (Figures 6A, B). Notably, similar to the clinical features of NPC1 disease, autophagy deficiency in the brain or liver of normal mice develops degeneration in Purkinje neurons or hepatocyte dysfunction, respectively (Hara et al., 2006; Komatsu et al., 2006; Komatsu et al., 2007). In addition, accumulation of p62 in autophagy–deficient mouse liver causes liver defects (Komatsu et al., 2010). Therefore, brain and liver–specific interference with autophagy in mice associated with neurodegeneration and liver injury suggest similar pathogenic consequences of impaired autophagy in NPC1 disease.

Figure 6. Impaired autophagic flux in vivo in organs from Npc1−/− mice and rescue of cell death in neurons with NPC1 knockdown.

(A and B) Immunoblot analyses with anti-NPC1, anti-p62, anti-LC3 and anti-actin antibodies in cerebellum (A) and liver (B) tissues from Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− mice.

(C) Immunoblot analyses with anti-NPC1, and anti-actin antibodies in primary mouse neural stem cells transduced with 5 different lentiviral Npc1 shRNAs or control (Con) shRNA. High (HE) and low (LE) exposures of the same immunoblot are shown. Densitometric analysis was done on low exposures of immunoblots.

(D) Immunofluorescence staining with anti-LC3 and anti-Tuj1 antibodies in neurons differentiated from mouse neural stem cells expressing control (Con) or Npc1_2 shRNA. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) Immunoblot analyses with anti-NPC1, anti-p62, anti-LC3 and anti-actin antibodies in neurons differentiated from mouse neural stem cells expressing control (Con) or Npc1_2 shRNA.

(F) Immunoblot analysis with anti-LC3 and anti-actin antibodies in neurons differentiated from mouse neural stem cells expressing control (Con) or Npc1_2 shRNA, treated with or without 400 nM bafilomycin A1 (Baf) for 4 h.

(G) Immunoblot analysis with anti-p62 and anti-actin antibodies in neurons differentiated from mouse neural stem cells expressing Npc1_2 shRNA, treated with or without 200 nM rapamycin (Rap), 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) or both for 72 h.

(H) Immunofluorescence staining with anti-Tuj1 antibody in neurons differentiated from mouse neural stem cells expressing control (Con) or Npc1_2 shRNA. Nuclei stained with DAPI and arrow shows an apoptotic nucleus. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(I) Analysis of cell death in Tuj1+ neurons differentiated from mouse neural stem cells expressing control (Con) or Npc1_2 shRNA, where neurons with NPC1 knockdown were treated with or without 200 nM rapamycin (Rap), 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) or both for 72 h.

Graphical data denote mean ± SEM. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ns, non-significant.

Induction of autophagy is protective in a neuronal model of NPC1 disease

To assess the efficacy of compounds in neurons, we used NPC1 knockdown cells to establish mouse neuronal cultures (Figure S6A). Since it is difficult to inhibit gene expression by shRNA in neurons, we initially infected mouse neural stem cells (Nestin+/Sox1+; Figure S6B) with 5 independent lentiviral Npc1 shRNAs, with Npc1_2 shRNA being the most effective construct in reducing NPC1 protein levels (Figure 6C). Neural stem cells stably expressing Npc1_2 shRNA were then differentiated with retinoic acid into neurons (Robertson et al., 2008), which express the neuronal markers, Tuj1 and MAP2 (Figures 6D and S6C). Consistent with our data, neurons expressing Npc1_2 shRNA increased LC3+ vesicles as well as LC3-II and p62 levels compared to control shRNA (Figures 6D, E); effects that were attributable to impaired autophagic flux as evident from the bafA1 assay (Figure 6F). Likewise, NPC1 knockdown in neurons derived from human embryonic stem cells expressing NPC1 shRNA also displayed an increase in LC3-II levels (Ordonez et al., 2012).

Treatment of Npc1 knockdown mouse neurons (Npc1_2 shRNA) with rapamycin, either alone or in combination with 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin, significantly reduced p62 levels (Figure 6G). However, 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin had no effects on p62 clearance (Figure 6G), suggesting that its low dose does not perturb autophagic flux in neuronal culture. We further show that Npc1 knockdown neurons (Npc1_2 shRNA) were associated with increased cell death (Figures 6H, I). Notably, this deleterious effect was significantly rescued by rapamycin or 0.2% HP-β-cyclodextrin, whereas the combination treatment, although exhibiting the greatest protection, was not significantly better than rapamycin alone (Figures 6I). Thus, our data suggest that stimulation of autophagy may be beneficial for NPC1 disease and raise the possibility for a combination treatment approach with agents inducing autophagy and depleting cholesterol.

DISCUSSION

In summary, our data imply that the NPC1 protein functions at the crossroads of autophagy and endocytosis to regulate amphisome formation, and its loss–of–function predominantly impairs autophagy–specific traffic (Figures 7 and S7). This is attributable to a defective SNARE complex machinery and it is likely that the LE/L–resident NPC1 protein plays a role in mediating membrane tethering events between autophagosomes and late endosomes. Furthermore, abrogation of autophagy also causes cholesterol accumulation that mimics the mutant NPC1–like phenotype. Therefore, the underlying defect in autophagy in NPC1 disease may be deleterious and can act as a positive mediator for accumulating cholesterol. Additionally, brain and liver–specific abrogation of basal autophagy in mice is associated with degeneration in the affected organs, which may imply similar pathogenic effects of defective autophagy in NPC1 patients.

Figure 7. Schematic representation of defective autophagy and the effects of its stimulation in NPC1 disease.

Mutations in the NPC1 protein inhibit cholesterol efflux and accumulate cholesterol in the LE/L compartments. Additionally, mutations in the NPC1 protein impair autophagosome maturation, leading to a block in autophagy associated with accumulation of autophagosomes (LC3+ vesicles) and autophagy substrates (p62 and mitochondria). This is attributed to defective amphisome formation where the autophagosomes fail to fuse with late endosomes (Rab7+ vesicles) due to the inability of NPC1–deficient late endosomes to recruit components of SNARE machinery, such as VAMP8 and VAMP3, which regulate this fusion event. NPC1 mutations also deplete DJ-1, leading to mitochondrial fragmentation and accumulation of damaged mitochondria due to impaired mitophagy. Upregulation of autophagy (such as by starvation and small molecules) bypasses the autophagy block in NPC1 mutant cells and rescues the autophagy defects by facilitating autophagosome maturation through their fusion with the lysosomes independent of amphisome formation, thereby mediating to the clearance of autophagic cargo.

Although autophagy upregulation is a potential treatment strategy for neurodegenerative disorders (Rubinsztein et al., 2012; Sarkar, 2013), the utility of such an approach for lipid/lysosomal storage diseases is not clear (Lieberman et al., 2012). Our study reveals that stimulating autophagy in the context of NPC1 disease can restore the clearance of autophagic cargo by mediating autophagosome–lysosome fusion independent of amphisome formation (Figure 7), which also suggests that the lysosomal proteolysis is functional. Our findings argue against inhibition of autophagy as a therapeutic strategy as reported recently (Ordonez et al., 2012), because such treatment may perturb its vital house–keeping functions (Hara et al., 2006; Komatsu et al., 2010; Komatsu et al., 2006; Komatsu et al., 2007; Ravikumar et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2009).

Our data suggest that stimulating autophagy does not rescue the cholesterol phenotype in NPC1 mutant cells, possibly because cholesterol is trapped in late endosomal compartments, whereas facilitating direct autophagosome–lysosome fusion restores functional autophagy, while HP-β-cyclodextrin serves as cholesterol depletion agent for NPC1 disease (Rosenbaum and Maxfield, 2011). Since HP-β-cyclodextrin also blocks autophagic flux and with high doses being neurotoxic (Peake and Vance, 2012), our data emphasize the need for careful dosing of this drug. Thus, a low dose of HP-β-cyclodextrin that partially depletes cholesterol without perturbing autophagy, coupled with an autophagy inducer that restores autophagic flux by overcoming its block, may provide a rational combination treatment strategy for NPC1 disease. We have validated some of these clinically–relevant observations in human hepatocytes derived from NPC1 patient–specific induced pluripotent stem cells, where impaired autophagy is rescued by small molecules enhancing autophagy (D. Maetzel, S. Sarkar, H. Wang and R. Jaenisch et al., unpublished data). Our study points to upregulating autophagy as a possible therapeutic strategy for the treatment of lipid/lysosomal storage disorders.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Details of experimental procedures can be found in Supplemental Information.

Culture of mammalian cells, neural stem cells and primary cortical neurons

Culture of Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs (Loftus et al., 1997) (gift from Peter Lobel), Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs (Kuma et al., 2004) (gift from Noboru Mizushima), HEK 293 cells, rat primary cortical neurons, mouse neural stem cells (mNSCs) and neuronal culture derived from mNSCs are described in Supplemental Information.

Immunoblot analysis

Cell lysates were subjected to western blot, as previously described (Sarkar et al., 2009). See Supplemental Information for details and list of primary antibodies.

Immunofluorescence and image analysis

Cell were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized and incubated with primary antibodies, as detailed in Supplemental Information. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH), as described in Supplemental Information.

Filipin and BODIPY staining for detecting cholesterol and lipid accumulation

Cholesterol accumulation in cells was visualized with Filipin staining (Filipin complex from Streptomyces filipinensis; Cat. No. F9765, Sigma Aldrich). After paraformaldehyde fixation, cells were incubated with 1.5 mg.mL−1 glycine for 10 min and incubated in 50 μg.mL−1 Filipin for 2–3 h at room temperature. Accumulation of neutral lipids in cells was visualized with BODIPY 493/503 staining (Singh et al., 2009) (4,4-Difluoro-1,3,5,7,8-Pentamethyl-4-Bora-3a,4a-Diaza-s-Indacene; Cat. No. D-3922, Life Technologies). Cells were incubated with 1 μM BODIPY 493/503 in full medium for 1 h prior to paraformaldehyde fixation.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Whole cell lysates of Npc1+/+ and Npc1−/− MEFs from triplicate experiments were subjected to mass spectrometry analysis. Sample preparation, chromatographic separations, mass spectrometry and data analysis are detailed in Supplemental Information.

Autophagy analyses

Analysis of autophagosome synthesis using bafilomycin A1

Autophagosome synthesis was analyzed by measuring LC3-II levels (immunoblotting with anti-LC3 antibody) in the presence of 400 nM bafilomycin A1, as previously described (Sarkar et al., 2009). See Supplemental Information for details.

Analysis of autophagic flux with mRFP-GFP-LC3 reporter

Autophagosomes (mRFP+-GFP+-LC3) and autolysosomes (mRFP+-GFP−-LC3) were quantified by ImageJ software using parameters as previously described (Kimura et al., 2007). See Supplemental Information for details.

Analysis of autophagic cargo flux with mCherry-GFP-p62 reporter

p62 aggregates associated with autophagosomes (mRFP+-GFP+-p62) and autolysosomes (mRFP+-GFP−-p62) were quantified by ImageJ software using parameters as previously described (Pankiv et al., 2007). See Supplemental Information for details.

Statistical analyses

Densitometry analyses on the immunoblots from multiple experiments were performed by Image J software (NIH), as previously described (Sarkar et al., 2007; Sarkar et al., 2009). The control condition was set to 100% and the data represented mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). The p values for various analyses were determined by Student’s t-test (unpaired) using Prism 6 software (GraphPad). ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ns, non-significant.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Accumulation of autophagosomes and late endosomes in NPC1 mutant cells.

Relates to Figure 1, which shows that accumulation of autophagosomes in NPC1 mutant cells is caused due to a block in autophagic flux.

Figure S2. Impaired amphisome formation in NPC1 mutant cells.

Relates to Figure 2, which shows that perturbation of SNARE machinery on late endosomes impairs amphisome formation in NPC1 mutant cells.

Figure S3. Impaired autophagosome maturation in NPC1 mutant cells, leading to accumulation of autophagic cargo whereas autophagosome biogenesis and lysosomal proteolysis are not overtly affected.

Relates to Figure 3, which shows that impaired autophagosome maturation retards autophagic cargo clearance in NPC1 mutant cells that are associated with defective mitophagy, whereas lysosomal proteolysis is not perturbed.

Figure S4. Expression of functional NPC1 protein increases autophagic flux and rescues autophagy defects in NPC1 mutant cells, whereas cholesterol depletion with HP-β-cyclodextrin blocks autophagy and impairs autophagic substrate clearance.

Relates to Figure 4, which shows rescue of autophagy defects in NPC1 mutant cells by expressing functional NPC1 protein, whereas cholesterol depletion treatment blocks autophagic flux.

Figure S5. Upregulation of autophagy facilitates its substrate clearance in NPC1 mutant cells by mediating autophagosome lysosome fusion independent of amphisome formation.

Relates to Figure 5, which shows that simulating autophagy rescues autophagy defects in NPC1 mutant cells by facilitating autophagosome maturation independent of amphisome formation, whereas abrogation of autophagy leads to accumulation of intracellular cholesterol.

Figure S6. Generation of neuronal culture with NPC1 knockdown.

Relates to Figure 6, which shows impaired autophagic flux in vivo in organs from Npc1−/− mice and rescue of cell death in neurons with NPC1 knockdown.

Figure S7. Overview of perturbations in the autophagy pathway in NPC1 disease.

Relates to Figure 7, which shows schematic representation of defective autophagy and the effects of its stimulation in NPC1 disease.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Defective autophagy in NPC1 disease is caused by failure in SNARE machinery

Loss of NPC1 protein impairs amphisome formation and autophagosome maturation

Cholesterol depletion treatment blocks autophagic flux

Induced autophagy rescues defects in basal autophagy without formation of amphisomes

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Lobel, D. Sleat, D. Ory, M. Scott, N. Mizushima, T. Yoshimori, T. Johansen, D. Rubinsztein, R. Zoncu, T. Galli, L. Traub, A. Helenius for valuable reagents; N. Watson, W. Salmon, L. Huang, L. Itskovich, G. Sahay, V. Baru for technical assistance; Keck Microscopy Facility; NNPD Foundation (D.M.), BBSRC New Investigator Award (V.I.K.). This work was supported by US NIH grants R37-CA084198 and R01-CA087869.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

R.J. is an advisor to Stemgent and Fate Therapeutics.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berg TO, Fengsrud M, Stromhaug PE, Berg T, Seglen PO. Isolation and characterization of rat liver amphisomes. Evidence for fusion of autophagosomes with both early and late endosomes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21883–21892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstea ED, Morris JA, Coleman KG, Loftus SK, Zhang D, Cummings C, Gu J, Rosenfeld MA, Pavan WJ, Krizman DB, et al. Niemann-Pick C1 disease gene: homology to mediators of cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1997;277:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrick MJ, Yu T, Chung C, Lieberman AP. Impaired proteolysis underlies autophagic dysfunction in Niemann-Pick type C disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4876–4887. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fader CM, Sanchez DG, Mestre MB, Colombo MI. TI-VAMP/VAMP7 and VAMP3/cellubrevin: two v-SNARE proteins involved in specific steps of the autophagy/multivesicular body pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:1901–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakahara Y, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Mishima K, Saito I, Okano H, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ME, Davies JP, Chen FW, Ioannou YA. Niemann-Pick C1 is a late endosome-resident protein that transiently associates with lysosomes and the trans-Golgi network. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;68:1–13. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonen E. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:125–138. doi: 10.1038/nrm2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi S, Yamazaki T, Okamoto K. Association of autophagy with cholesterol-accumulated compartments in Niemann-Pick disease type C cells. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:954–959. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Kishi-Itakura C, Mizushima N. The hairpin-type tail-anchored SNARE syntaxin 17 targets to autophagosomes for fusion with endosomes/lysosomes. Cell. 2012;151:1256–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager S, Bucci C, Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E, Saftig P, Eskelinen EL. Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4837–4848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karten B, Peake KB, Vance JE. Mechanisms and consequences of impaired lipid trafficking in Niemann-Pick type C1-deficient mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy. 2007;3:452–460. doi: 10.4161/auto.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Beuchat MH, Lindsay M, Frias S, Palmiter RD, Sakuraba H, Parton RG, Gruenberg J. Late endosomal membranes rich in lysobisphosphatidic acid regulate cholesterol transport. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:113–118. doi: 10.1038/10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga H, Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. Altered lipid content inhibits autophagic vesicular fusion. FASEB J. 2010;24:3052–3065. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Kurokawa H, Waguri S, Taguchi K, Kobayashi A, Ichimura Y, Sou YS, Ueno I, Sakamoto A, Tong KI, et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:213–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Chiba T, Murata S, Iwata JI, Tanida I, Ueno T, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Koike M, Sou YS, Ueno T, Hara T, Mizushima N, Iwata J, Ezaki J, Murata S, et al. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolchuk VI, Mansilla A, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagy inhibition compromises degradation of ubiquitin-proteasome pathway substrates. Mol Cell. 2009;33:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y, Tokuhisa T, Mizushima N. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HJ, Abi-Mosleh L, Wang ML, Deisenhofer J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Infante RE. Structure of N-terminal domain of NPC1 reveals distinct subdomains for binding and transfer of cholesterol. Cell. 2009;137:1213–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AP, Puertollano R, Raben N, Slaugenhaupt S, Walkley SU, Ballabio A. Autophagy in lysosomal storage disorders. Autophagy. 2012;8:719–730. doi: 10.4161/auto.19469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus SK, Morris JA, Carstea ED, Gu JZ, Cummings C, Brown A, Ellison J, Ohno K, Rosenfeld MA, Tagle DA, et al. Murine model of Niemann-Pick C disease: mutation in a cholesterol homeostasis gene. Science. 1997;277:232–235. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Signalling and autophagy regulation in health, aging and disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27:411–425. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard EE, Srivastava K, Traub LM, Schaffer JE, Ory DS. Niemann-pick type C1 (NPC1) overexpression alters cellular cholesterol homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38445–38451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordonez MP, Roberts EA, Kidwell CU, Yuan SH, Plaisted WC, Goldstein LS. Disruption and therapeutic rescue of autophagy in a human neuronal model of Niemann Pick type C1. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2651–2662. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco CD, Kunkel R, Lieberman AP. Autophagy in Niemann-Pick C disease is dependent upon Beclin-1 and responsive to lipid trafficking defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1495–1503. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, Overvatn A, Bjorkoy G, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peake KB, Vance JE. Normalization of cholesterol homeostasis by 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin in neurons and glia from Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:9290–9298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.326405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Berger Z, Vacher C, O’Kane CJ, Rubinsztein DC. Rapamycin pre-treatment protects against apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1209–1216. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, et al. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1383–1435. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Vacher C, Berger Z, Davies JE, Luo S, Oroz LG, Scaravilli F, Easton DF, Duden R, O’Kane CJ, et al. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36:585–595. doi: 10.1038/ng1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MJ, Gip P, Schaffer DV. Neural stem cell engineering: directed differentiation of adult and embryonic stem cells into neurons. Front Biosci. 2008;13:21–50. doi: 10.2741/2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum AI, Maxfield FR. Niemann-Pick type C disease: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic approaches. J Neurochem. 2011;116:789–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein DC, Codogno P, Levine B. Autophagy modulation as a potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:709–730. doi: 10.1038/nrd3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S. Regulation of autophagy by mTOR-dependent and mTOR-independent pathways: autophagy dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases and therapeutic application of autophagy enhancers. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:1103–1130. doi: 10.1042/BST20130134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Floto RA, Berger Z, Imarisio S, Cordenier A, Pasco M, Cook LJ, Rubinsztein DC. Lithium induces autophagy by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:1101–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Perlstein EO, Imarisio S, Pineau S, Cordenier A, Maglathlin RL, Webster JA, Lewis TA, O’Kane CJ, Schreiber SL, et al. Small molecules enhance autophagy and reduce toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nchembio883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Ravikumar B, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagic clearance of aggregate-prone proteins associated with neurodegeneration. Methods Enzymol. 2009;453:83–110. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Cuervo AM, Czaja MJ. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleat DE, Wiseman JA, Sohar I, El-Banna M, Zheng H, Moore DF, Lobel P. Proteomic analysis of mouse models of Niemann-Pick C disease reveals alterations in the steady-state levels of lysosomal proteins within the brain. Proteomics. 2012;12:3499–3509. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KJ, McCoy MK, Blackinton J, Beilina A, van der Brug M, Sandebring A, Miller D, Maric D, Cedazo-Minguez A, Cookson MR. DJ-1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/parkin pathway to control mitochondrial function and autophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:40–50. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youle RJ, Narendra DP. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Xue R, Ong WY, Chen P. Roles of cholesterol in vesicle fusion and motion. Biophys J. 2009;97:1371–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Accumulation of autophagosomes and late endosomes in NPC1 mutant cells.

Relates to Figure 1, which shows that accumulation of autophagosomes in NPC1 mutant cells is caused due to a block in autophagic flux.

Figure S2. Impaired amphisome formation in NPC1 mutant cells.

Relates to Figure 2, which shows that perturbation of SNARE machinery on late endosomes impairs amphisome formation in NPC1 mutant cells.

Figure S3. Impaired autophagosome maturation in NPC1 mutant cells, leading to accumulation of autophagic cargo whereas autophagosome biogenesis and lysosomal proteolysis are not overtly affected.

Relates to Figure 3, which shows that impaired autophagosome maturation retards autophagic cargo clearance in NPC1 mutant cells that are associated with defective mitophagy, whereas lysosomal proteolysis is not perturbed.

Figure S4. Expression of functional NPC1 protein increases autophagic flux and rescues autophagy defects in NPC1 mutant cells, whereas cholesterol depletion with HP-β-cyclodextrin blocks autophagy and impairs autophagic substrate clearance.

Relates to Figure 4, which shows rescue of autophagy defects in NPC1 mutant cells by expressing functional NPC1 protein, whereas cholesterol depletion treatment blocks autophagic flux.

Figure S5. Upregulation of autophagy facilitates its substrate clearance in NPC1 mutant cells by mediating autophagosome lysosome fusion independent of amphisome formation.

Relates to Figure 5, which shows that simulating autophagy rescues autophagy defects in NPC1 mutant cells by facilitating autophagosome maturation independent of amphisome formation, whereas abrogation of autophagy leads to accumulation of intracellular cholesterol.

Figure S6. Generation of neuronal culture with NPC1 knockdown.

Relates to Figure 6, which shows impaired autophagic flux in vivo in organs from Npc1−/− mice and rescue of cell death in neurons with NPC1 knockdown.

Figure S7. Overview of perturbations in the autophagy pathway in NPC1 disease.

Relates to Figure 7, which shows schematic representation of defective autophagy and the effects of its stimulation in NPC1 disease.