Abstract

Importance of the field

The eukaryotic cell division cycle is a tightly regulated series of events coordinated by the periodic activation of multiple cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks). Small-molecule cdk-inhibitory compounds have demonstrated preclinical synergism with DNA-damaging agents in solid tumor models. An improved understanding of how cdks regulate the DNA damage response now provides an opportunity for optimization of combinations of cdk inhibitors and DNA damaging chemotherapy agents that can be translated to clinical settings.

Areas covered in this review

Here, we discuss novel work uncovering multiple roles for cdks in the DNA-damage-response network. First, they activate DNA damage checkpoint and repair pathways. Later their activity is turned off, resulting in cell cycle arrest, allowing time for DNA repair to occur. Recent clinical data on cdk inhibitor–DNA-damaging agent combinations are also discussed.

What the reader will gain

Readers will learn about novel areas of cdk biology, the complexity of DNA damage signaling networks and clinical implications.

Take home message

New data demonstrate that cdks are ‘master’ regulators of DNA damage checkpoint and repair pathways. Cdk inhibition may therefore provide a means of potentiating the clinical activity of DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of cancer.

Keywords: chemotherapy, cyclin-dependent kinase, DNA damage

1. Introduction

Cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) are a family of Ser/Thr (S/T) kinases that play a central role in the eukaryotic cell division cycle [1]. Genomic integrity is maintained through the precise activation of cdks and the correctly timed coordination of DNA synthesis. Cdk2 and cdk1, together, direct S and G2 phase transit, while cdk1 governs the G2/M transition and mitotic progression [2-4]. A promising new area of study has recently emerged in the field of cyclin-dependent kinase research. First in yeast, and now in mammalian cells, multiple lines of evidence suggest a highly diverse and complex role for cdks in the cellular response to DNA damage. Traditionally, cdks are placed at the end of the DNA damage checkpoint, where their activity is inhibited, resulting in cell cycle arrest and allowing time for DNA repair [5,6]. Now, cdks have been shown to be required upstream in DNA damage response pathways, and are potentially among the first kinases to respond to aberrant DNA structures. Cdks play crucial roles in both the activation of DNA damage checkpoint signaling and the initiation of DNA repair. Consequently, targeting cdks for inhibition by pharmalogical intervention may abrogate DNA-damage-induced checkpoint and repair pathways and provide a means of potentiating responses to DNA-damaging chemotherapy. The recent biological data provide a plausible rationale for cdk-inhibitor–DNA-damaging agent combinations for the treatment of cancer.

1.1 Cdks, the cell cycle and cancer

Cdks can be divided into two groups, including ‘cell cycle’ cdks, which orchestrate cell cycle progression, and ‘transcriptional’ cdks, which contribute to mRNA synthesis and processing [2,3,7]. The first group encompasses core components of the cell cycle machinery, including cyclin D-dependent kinases 4 and 6, as well as cyclin E–cdk2 complexes, which sequentially phosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein (Rb), to facilitate the G1/S transition [8-10]. Cyclin A-dependent kinases 2 and 1 are required for orderly S phase progression, whereas cyclin B–cdk1 complexes control the G2/M transition and participate in mitotic progression [4]. The functional activation of cdks depends in part on the formation of heterodimeric cyclin–cdk complexes that may be modulated by association with endogenous Cip/Kip or INK4 inhibitors [11,12]. Cdks are also regulated by phosphorylation, including positive events directed by cdk-activating kinase (CAK, cyclin H-cdk7/MAT1), as well as negative phosphorylation events [13]. The transcriptional cdks, including cyclin H–cdk7 and cyclin T–cdk9 (pTEFb) phosphorylate the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II to promote elongation of mRNA transcription [14-18]. Cyclin T–cdk9 also regulates mRNA processing [19].

Cancer is characterized by uncontrolled cellular proliferation. Amplification or mutation of genes encoding cyclins or cdks, or deletion, mutation or hypermethylation of genes encoding endogenous inhibitors of cdks, ultimately results in deregulated cdk activity and loss of cell cycle control, a universal feature of malignant cells [20,21]. In attempts to re-establish cell cycle control and block cancer cell proliferation, small-molecule ATP-competitive inhibitors remain under active study. Nonetheless, clinical activity has been modest, especially in solid tumors [2].

Recently, however, there has been recognition that cdk activity contributes to multiple aspects of the DNA damage response, including checkpoint control and repair. These insights have generated enthusiasm for combinations of cdk inhibitors with DNA-damaging agents and may help define a place for cdk inhibition in the anti-cancer armamentarium.

1.2 DNA damage checkpoint signaling

Exposure to genotoxic insults results in the activation of checkpoint cascades that ultimately downregulate cdk activities and impose cell cycle arrest that prevents the propagation of damaged DNA. Delay of cell cycle progression is initiated by DNA damage-induced activation of the PI3K-like protein kinases (PI3KKs) ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated) and ATR (ATM and Rad3-related) [22]. ATR is the primary sensor of events that cause replication stress, such as stalling of replication forks or formation of single-strand DNA breaks (SSBs). ATR is recruited to sites of single-stranded DNA coated with replication protein A (RPA) via ATR-interacting protein (ATRIP) [23] and phosphorylates substrates that mediate checkpoint control and DNA repair, including the checkpoint kinase Chk1. ATM is recruited to ionizing radiation (IR)-induced double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) by the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex and upon activation also phosphorylates multiple substrates, including Chk2 [24]. MRN, together with the endonuclease C-terminal binding protein-interacting protein (CtIP) [25], carries out the process of end resection in order to produce regions of single-strand DNA which are coated with RPA. End resection occurs predominantly during the S and G2 phases and results in ATM-dependent ATR activation. [26]. Activated Chk1 and Chk2 antagonize the function of Cdc25 phosphatases, allowing accumulation of inhibitory phosphates on Thr14 and Tyr15 of cdks, resulting in inhibition of cdk activity and delayed cell-cycle progression, providing time for DNA repair [27]. Notably, breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein (BRCA1) is a critical component of ATM- and ATR-mediated checkpoint signaling and is hyperphosphorylated by ATM and ATR in response to DNA damage. BRCA1 serves as a scaffold that facilitates the ability of ATM/ATR to phosphorylate a subset of substrates including Chk1 and Chk2 [28,29].

1.3 DNA damage repair

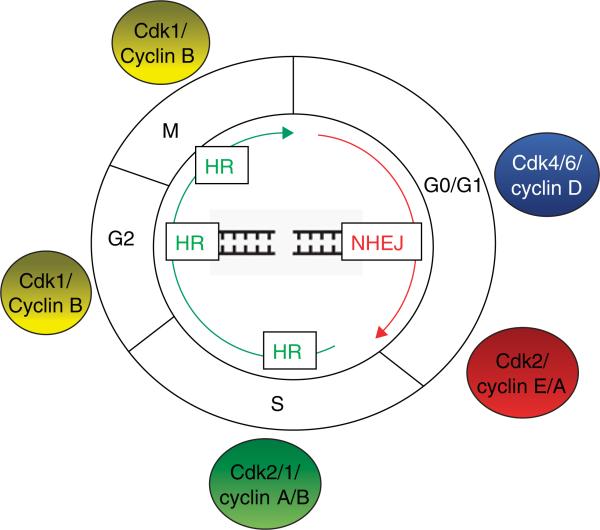

DNA damage in mammalian cells can be repaired by one of two processes, either by homologous recombination (HR) or by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). HR is initiated by 5′-to-3′ resection of DNA from the DSB to yield ssDNA, which becomes coated by RPA subunits. In addition to facilitating ATR recruitment for checkpoint control, RPA is required for recruitment of Rad52 and BRCA2, which eventually displace RPA and load the Rad51 recombinase to form a nucleoprotein filament capable of strand invasion at a homologous sequence, leading to repair by gene conversion. HR is generally error-free [30]. In contrast, NHEJ fuses the two broken ends, with little regard for homology, leading to deletions and other rearrangements. Growing evidence suggests that there are multiple pathways for NHEJ. The best understood pathway involves the heterodimeric Ku protein, DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs), and the DNA ligase IV-XRCC4 complex. Initial steps in NHEJ are DSB detection by the Ku70/80 heterodimer, followed by recruitment of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-PKcs to form the active DNA-dependent protein kinase holoenzyme (DNAPK) [31]. In both yeast and vertebrates, the two modes of DSB repair are regulated reciprocally, with NHEJ predominating in the G0/G1, and HR in the S/G2 cell cycle phases (Figure 1) [32].

Figure 1. DNA repair is cell cycle regulated.

In both yeast and vertebrates, there are two modes of double-stranded break (DSB) repair – non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). These mechanisms of repair are reciprocally regulated in the cell cycle. NHEJ predominates in G0/G1, when cdk1 and cdk2 activity are low, and HR in S/G2/M cell cycle phases, where cdk1/2 activity is high.

2. Cdks and the DNA damage response

Cdk1 and cdk2 activities are downregulated at the end of the DNA-damage checkpoint signaling pathway, affording cell cycle arrest and time for DNA repair processes to occur. However, emerging evidence indicates that cdks play critical roles upstream in the initiation of checkpoint control and DNA repair, prior to the terminal events in the checkpoint cascade when their activities are inhibited.

2.1 Cdks and DNA damage checkpoint control

In budding yeast, cdk1 (cdc28) activity is required for activation of DNA end resection and ultimately the Mec1 (ATR homolog)-dependent DNA damage checkpoint following a DSB [33,34]. In human cancer cell lines, brief exposure to small-molecule-mediated combined inhibition of cdk2 and cdk1, but not cdk1 alone, in concert with DNA damage, also compromises DNA end resection [26,35], indicating that in mammalian cancer cells both cdk2 and cdk1 activity can activate end resection. Activation of endonuclease activity requires cdk-mediated phosphorylation of CtIP at T847, analogous to events that occur in yeast [36]. Combined inhibition of cdk2 and cdk1 therefore compromises ATR recruitment, through abrogation of CtIP-mediated resection of double stranded DNA breaks to single-stranded regions, where ATR would normally be recruited and subsequently mediate direct phosphorylation of Chk1.

DNA end resection is one level at which cdk activity regulates the DNA damage response. However, when cells are treated with hydroxyurea (HU), which results in DNA end resection-independent ssDNA break formation and direct ATR activation, Chk1 phosphorylation is also abrogated when cdk activity is inhibited [35]. Cdks may therefore regulate ATR function at additional levels. Recently, it has been reported that ATRIP contains a consensus site for cdk-mediated phosphorylation at S224, which is phosphorylated by cyclin A-cdk2 in vitro. This event is required to maintain G2 arrest after DNA damage; U2OS osteosarcoma cells reconstituted with mutated ATRIP at S224 were not as tightly arrested at G2 after ionizing radiation as cells containing wild-type ATRIP [37].

In both yeast and mammalian cells, cdks have been shown to phosphorylate RPA proteins. The RPA complex consists of three subunits of 70, 32 and 14 kDa (RPA70, RPA32 and RPA14, respectively). When cells encounter DNA damage, the N-terminal region of RPA32 undergoes phosphorylation by multiple kinases, including ATR at S33, cdk1 and cdk2 at S23 and S29 and other PI3KKs at T21 and S4/8. Critically, cdks can phosphorylate the N-terminal region of RPA32 only in the presence of ATR-dependent phosphorylation at the S33 site, while stimulating sequential and synergistic phosphorylation events at additional sites by PI3KKs [38]. The N-terminal region of RPA32 does not directly bind to ssDNA or to other RPA subunits. At present, the physiological significance of these phosphorylation events is yet to be elucidated. However, RPA32 hyperphosphorylation may induce allosteric structural changes and/or increased hydrophilicity, and hence promote the recruitment of DNA recombination factors such as Rad51, Rad52 and BRCA2 that interact with the RPA complex [39].

Recent studies have also elucidated roles for cdk proteins in processes following end resection and ATR and RPA32 recruitment. Notably, Chk1 and other ATR and ATM targets are not efficiently phosphorylated when cdk1 is selectively depleted or inhibited in NSCLC cell lines [35], resulting in loss of DNA-damage-induced S phase checkpoint control. This outcome was caused by a reduction in formation of BRCA1-containing foci. Furthermore, re-expression in BRCA1-deficient cells of a mutant form of BRCA1 at cdk phosphorylation sites S1497 and S1189/S1191 resulted in compromised formation of BRCA1-containing foci compared with those engineered to express wild type BRCA1. ATR and ATM-mediated phosphor-ylation of non-chromatin-bound proteins is dependent on BRCA1 focus formation [28,29]; therefore when cdk1 is inhibited and BRCA1 foci formation is reduced, Chk1 and other BRCA1-dependent ATM/ATR substrates are not phosphorylated.

It is of interest that while cdk2 can compensate for reduced cdk1 activity during DNA end resection and recruitment of ATR and RPA32 in NSCLC cells, the same was not true for BRCA1 phosphorylation. With individual cdk depletion, only cdk1 depletion, but not depletion of cdk2, reduced BRCA1 phosphorylation and focus formation and sensitized to DNA damaging treatments in the NSCLC cells examined. In these cells, selective cdk2 depletion had no effects on the DNA damage response, so that its roles in these processes were probably performed by cdk1. However, cell-type-specific differences may exist. For example, in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, selective cdk2 depletion does result in significant abrogation of Chk1 and p53 phosphorylation after treatment with ionizing radiation [40]. Therefore, the elucidation of individual roles of cdk1 and cdk2 in upstream processes in the DNA damage response will require further study in multiple cell types.

Importantly, a therapeutic window for targeting tumor cells but protecting non-transformed cells may be achievable with selective cdk1 inhibition. The sensitization by cdk1 depletion to DNA damage was only seen in transformed NSCLC cells, and not in non-transformed cells. In contrast to transformed cells, which continued to proliferate in the absence of cdk1 because of compensation by cdk2, non-transformed cells underwent potent G2 arrest in response to cdk1 depletion, which antagonized the response to subsequent DNA damage [35].

Alternatively, it is possible that the role of cdk1 in the DNA damage response in non-transformed cells is compensated by other family members. Studies in murine cells have suggested that DSB end resection and activation of the DNA damage response is controlled by total cdk activity, rather than by individual cdks [41]. For example, RPA focus formation and Chk1 phosphorylation were not compromised in cdk2−/− cdk4−/− cdk6−/− cells or in cdk2−/− cells in which cdk1 was concomitantly depleted. However, pan-cdk inhibition with the small-molecule inhibitor purvalanol did disrupt these processes. The results in cells lacking both cdk2 and cdk1 activities suggests that cdk4/6 activity can compensate and participate in DNA damage responses when necessary, at least in these non-transformed cells. It is possible that during the evolution to malignancy, the compensatory ability of cdks in these processes is diminished, such that selective depletion of cdk 1 and/or cdk2 does sensitize to DNA damaging treatments in tumor cells lines, as in the examples of individual cdk1 and cdk2 depletion in NSCLC and breast carcinoma cells, respectively.

Cdk5 has recently been shown to directly phosphorylate ATM at S794, an essential event for the activation of ATM kinase activity in response to DNA damage in post-mitotic neurons [42]. Whether cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of ATM occurs in other cell types in response to DNA damage has not been clarified; however, these results raise the possibility of essential cdk activity at one of the earliest steps in the DNA damage response. Additionally, cdk5 depletion sensitized non-neuronal cells to Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition, although the precise mechanism has not yet been defined [43].

2.2 Cell cycle cdks, BRCA protein phosphorylation and DNA repair

The role of cdks in end resection and BRCA1 recruitment following a DSB are critical not only for checkpoint activation but also for HR repair. In budding yeast, HR is inhibited by an analogue-sensitive cdk1 (cdc28) protein, resulting in a compensatory increase in NHEJ. Cdk1 is required not only for efficient 5′ to 3′ resection of DSB ends and the recruitment of both the single-stranded DNA-binding complex, RPA and the Rad51 recombination protein, but for a later additional step in HR, after strand invasion and before the initiation of new DNA synthesis [33].

In mammalian cells, cdk-mediated phosphorylation of the CtIP endonuclease is required to activate DNA end resection. Phosphorylation of CtIP at T847 stimulates its endonuclease activity, while cdk-mediated phosphorylation at S327 is critical for the interaction of CtIP with BRCA1 and recruitment of CtIP to sites of DNA damage [44]. Following DNA damage, during S and G2, the cdk-dependent CtIP–BRCA1 interaction directs the cell toward HR repair, as opposed to NHEJ that occurs during G1, when cdk2 and cdk1 activities are low (Figure 1) [45].

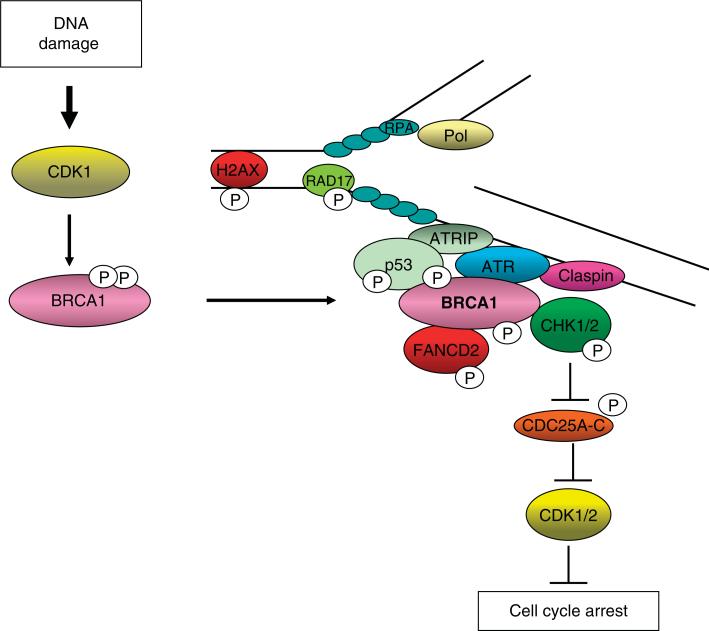

Additionally, in mammalian cells, the role of cdk1 in BRCA1 phosphorylation at S1497 and S1189/S1191 (Figure 2), and subsequent recruitment to sites of DNA damage, is likely to also be important for Rad51 recruitment and HR repair. Cdk inhibition may therefore sensitize cells to DNA-damaging treatments not only by compromising checkpoint signaling, but also by preventing HR repair. By extension, cdk1 inhibition has been shown to sensitize cancer cells to PARP inhibition [46].

Figure 2. Cdk activity is required at the beginning and end of checkpoint signaling.

Although cdks have traditionally been considered to be the downstream targets of DNA-damage-induced checkpoint cascades, cdk activity remains elevated initially after exposure to DNA damage. Specifically, cdk1 phosphorylates breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein (BRCA1) at S1497 and S1189/S1191, events required for efficient BRCA1 focus formation. Therefore, cdk activity facilitates the ataxiatelangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM and Rad3-related (ATR)-dependent phosphorylation of non-chromatin bound substrates, including checkpoint kinase (Chk)1/2, Fanconi's anemia, complementation group D2 (FANCD2) and p53. Eventually, activation of checkpoint kinases leads to inhibition of cdk1 and cdk2 activities, permitting cell cycle arrest.

ATRIP: ATR-interacting protein; H2AX: Histone 2 AX; pol: Polymerase; RPA: Replication protein A.

Cyclin D1–cdk4 can also phosphorylate BRCA1 at S632 in vitro and this phosphorylation event has been proposed to affect the transcriptional function of BRCA1. Cyclin D1–cdk4 phosphorylation at S632 decreased the association of BRCA1 with particular gene promoters and conversely inhibition of cyclin D1–cdk4 activity resulted in increased BRCA1 DNA binding to promoters [47]. Cyclin D1 was also shown to strongly interact with BRCA1 only in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. However, the effect of cyclin D1–cdk4-mediated BRCA1 phosphorylation on BRCA1-dependent DNA damage responses have not been investigated.

Cdk2 has also been shown to phosphorylate BRCA2 at S3291 in a cell-cycle-dependent manner, which impairs its interaction with Rad51, thereby inhibiting homologous recombination [48]. The phosphorylation site lies within a region that confers interaction with Rad51. Although this activity of cdk2 appears paradoxical, it is representative of the interaction of cdks with BRCA proteins designed to insure that checkpoint control and DNA repair are properly coordinated. Immediately after DNA damage, cdk activity remains high. Cdk1 and cdk2 activities regulate DNA end resection and BRCA1 function and ultimately ATR–Chk1 signaling (Figure 2), while cdk2 phosphorylates BRCA2 and prevents homologous recombination. Later, only after cdk activity is reduced downstream in the checkpoint cascade to promote cell cycle arrest, is the interaction of BRCA2 and Rad51 facilitated, permitting homologous recombination repair [26].

Although it is generally considered that cdks direct HR events during S and G2/M, where cdk activity is high, there is evidence for cdks playing a role in other repair processes. Notably, in NSCLC cell lines, combined depletion of cdk1 and BRCA1 was no more efficient at sensitizing cells to DNA-damaging agents than knockdown of either alone [35]. In contrast, in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, combined cdk2 and BRCA1 depletion resulted in a substantially greater reduction in colony formation compared with individual knockdowns [40]. These results suggest that in MCF-7 cells, cdk2 may affect DNA repair pathways other than HR, and that the targeting of several repair pathways may be synthetically lethal, as is the case with PARP inhibition in a background of BRCA deficiency [49]. Coupled with high cyclin E and low p27Kip1 expression found in BRCA-deficient cells [40,50,51], it is possible that these cells are particularly cdk2-dependent. Whether cdk2 inhibition has therapeutic value in BRCA1-deficient cancers is yet to be clinically tested.

Nonetheless, there is evidence for the participation of cdks in the regulation of NHEJ [40,52]. Ku70 was reported to be a substrate of cyclin A1–cdk2 [53]. Another putative cdk substrate, implicated in NHEJ as well as base excision repair (BER), is DNA polymerase λ, which belongs to the X family of polymerases. Pol λ could be co-immunoprecipitated with cdk2 from HeLa cell extracts and was phosphorylated by cdk2 and cdk1 in in vitro kinase assays [54]. In vivo, phosphorylation of pol λ is cell-cycle-regulated and stabilizes the protein, possibly to promote its specific functions in DNA damage repair in late S and G2 phases [55].

3. Cdk inhibition as a direct cause of the DNA damage response

In addition to affecting checkpoint control and repair in response to DNA damage, cdk inhibition may itself elicit a DNA damage response via a variety of mechanisms.

3.1 Cdk2 inhibition and modulation of the minichromosome maintenance (MCM) complex during DNA replication

During S phase, cdk inhibition mediated by pharmacological inhibitors, dn-cdk2 and siRNA targeting cdk2, elicits an intra-S phase checkpoint that shares components of the pathway activated by DSBs [56]. In A2780 ovarian cancer cells, cdk inhibition has been shown to induce the accumulation of activated forms of ATM as well as nuclear foci containing phosphorylated substrates of ATM, including p53 and γ-H2AX, suggesting that cdk inhibition can induce or predispose to DNA damage. Cdk2 phosphorylates a number of proteins during S phase, including minichromosome maintanence proteins (MCM), which are required for origin replication firing. Cdk2 mediated phosphorylation of MCM proteins is required to block continued reformation of the prereplication complex; cdk2 inhibition during DNA replication therefore leads to increased MCM complex association with DNA and triggers rereplication. Over-replication probably results in the formation of DSBs and ssDNA intermediates, which activate ATM and ATR, and subsequently p53 [56,57].

3.2 Cdk inhibition during S phase compromises Chk1 activity and destabilizes replication forks

An alternative mechanism by which cdk inhibition could mediate DNA damage appears to be related to the reduced expression of Chk1 [58,59]. Chk1, along with Chk2, is typically activated by DNA damage in order to constrain cdk activity. However, following prolonged (i.e., 24 h) cdk inhibition during S phase, the response to cell cycle slowing involves downregulation of Chk1, perhaps part of a negative feedback loop promoting cell cycle recovery. Reduced cdk activity may slow or stall DNA replication forks. This block in replication is detected by ATR, which primarily activates Chk1. Stalled replication forks are dependent on the ATR–Chk1 pathway for stabilization; when Chk1 activity is compromised DSBs may occur. This mechanism may in part explain the increased frequency of DSBs and cytotoxicity observed when cdk inhibitors are combined with DNA-damaging treatments such as topoisomerase inhibitors [52,58].

4. Combinations of pharmacologic cdk inhibitors and DNA damaging agents

Multiple preclinical experiments and clinical trials have evaluated small-molecule cdk inhibitors in combination with DNA damaging agents [2]. Several of these trials have employed flavopiridol, the first cdk inhibitor compound to enter clinical use, with provocative results [60-62].

4.1 Cdk inhibitor compounds

Cdk inhibitors are best characterized based on their effects on cell cycle cdks. Selective agents include PD0332991 [63,64], a potent inhibitor only of cyclin D-cdk4/6 complexes, and RO-3306, which has ten-fold selectivity for cyclin B-cdk1 relative to cyclin E-cdk2 and 50-fold relative to cyclin D-cdk4 [65].

Other agents are more promiscuous and inhibit multiple cell cycle cdks. Such compounds inhibit both cdk2 and cdk1, either with some selectivity for cdk2, such as Seliciclib [66,67] or SNS-032 [68], or with equipotency, including Dinaciclib (SCH727965) [69,70]. Cdk2/1 inhibitors also frequently inhibit transcriptional cdks, including cyclin H–cdk7 and cyclin T–cdk9, to varying degrees. Cdk9 inhibition affects mRNA elongation and processing and can deplete cancer cells of a variety of short-lived mRNAs and the proteins they encode, including anti-apoptotic proteins, such as myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 (Mcl-1) and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) [2,71]. Flavopiridol, considered a pan-cdk inhibitor, is the most potent known inhibitor of cdk9, with an inhibition constant (Ki) of approximately 3 nM, such that it is difficult to detect competition with ATP [72-74].

Several of the cdk9 inhibitors have demonstrated promise as monotherapies against hematological malignancies, in particular chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), in pharmacokinetically-derived schedules [75-77], which may in part be related to their ability to deplete cells of Mcl-1 [78]. In fact, in CLL, tumor lysis syndrome has been the dose-limiting toxicity, supporting the efficacy of these agents in this disease. Seliciclib has recently demonstrated activity against nasopharyngeal cancers, with 7 out of 15 tumors demonstrating regression in a pilot study [79]. There was pharmacodynamic evidence of cdk2 inhibition, as well as cdk7 and 9 inhibition, evidenced by modulation of T821 Rb phosphorylation, levels of Mcl-1 and cyclin D1 in tumor biopsies. Cdk9 inhibition may have also affected EBV-mediated gene expression, on which these tumors may depend. Against other solid tumors, however, cdk inhibitor monotherapy has produced stable disease, consistent with drug-induced cell cycle arrest [2]. However, lack of documented partial or complete responses has reduced enthusiasm for the development of these agents in solid tumors. Additionally, agents that inhibit cdk9 and can reduce Mcl-1 expression in hematopoietic cells can induce acute neutropenia, since neutrophils depend on Mcl-1 for survival [80]. Recent insights, including the dependence of subsets of melanomas and neuroblastomas on cdk2 [81,82], or importance of cdk4 in Kras mutant NSCLC [83] have not been clinically explored. Despite the absence of robust single-agent activity to date, combination of cdk inhibitors and DNA-damaging agents have been pursued.

4.2 Cell cycle cdk inhibition and DNA-damaging chemotherapy

Primary resistance to chemotherapeutic agents may be in part due to activation of checkpoints that interrupt cell cycle progression and allow time for DNA repair [84]. The role of cdks in DNA-damage-induced checkpoint control and repair suggest that cdk inhibitors augment the DNA damage response. This mechanism probably contributes to synergistic effects recently reported between RO-3306-mediated cdk1 inhibition and cisplatin [35]. In this particular case, selective cdk1 inhibition disrupts BRCA1 function without fully arresting the cancer cell cycle, blocking activation of the S phase checkpoint, as well as DNA repair. The cell cycle is not potently arrested because of the ability of cdk2 to compensate for cdk1 in cell cycle progression. Additionally, since such compensation does not appear to occur in non-transformed cells, which are potently arrested at the G2 boundary after selective cdk1 inhibition, sensitization to cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity was selective for transformed cell types.

However, because many cdk inhibitors inhibit multiple cdk family members, their use in concert with DNA-damaging agents is indeed complicated by direct cell cycle arrest that may be superimposed on the modulation of upstream components of checkpoint and repair pathways. For example, flavopiridol itself induces G1 and G2 cell cycle arrest [85,86]. Therefore, if flavopiridol precedes, or is used concomitantly with an S phase DNA-damaging agent, cell cycle arrest may inhibit a cytotoxic response [87]. However, appropriate drug sequencing, where first an S phase DNA-damaging agent is administered, followed by flavopiridol treatment, overcomes this problem and significantly increases cell killing.

Flavopiridol was found to potentiate both hydroxyurea- and gemcitabine-induced apoptosis in a sequence-dependent manner in several NSCLCcell lines [88]. Here, the S-phase delay induced by gemcitabine is likely to play an important role in the ability of flavopiridol to potentiate DNA-damage-induced cell death, and may be related to modulation of the activity of E2F-1, a critical cdk target during S phase [89,90]. During the G1–S transition, as the retinoblastoma protein is phosphorylated, E2F-1 is de-repressed and ultimately released in order to direct transcription of genes required for S phase traversal. However, E2F-1 is transcriptionally active for only a limited period of time in early S phase, after which its activity must be extinguished in order to facilitate proper cell cycle progression to G2. The downregulation of E2F-1 activity is mediated by several cdk holoenzymes, most notably cyclin A–cdk2 [91-93]. Inhibition of cyclin A–cdk2 activity during S phase results in inappropriate and persistent E2F-1 activity, activating an apoptotic trigger, potentially via a p73-dependent mechanism [94]. Therefore, treatment of cells with flavopiridol during S phase traversal (i.e., gemcitabine-mediated S phase delay) reduces cdk2-mediated phosphorylation of E2F-1, an event critical for an enhanced apoptotic response [88,89]. Importantly, deregulated and persistent E2F transcriptional activity during S phase selectively sensitizes transformed cells to apoptosis [95]. Although, persistence of E2F-1 activity is expected in non-transformed cells following cdk inhibition during S phase, the overall lower levels of this activity (related to fully intact retinoblastoma protein function) makes this tolerable, so that the threshold for triggering apoptosis is not reached.

Of note, there is not full agreement in the literature on the role of elevated E2F-1 activity in the cytotoxic response to combinations of S phase DNA-damaging agents and cdk inhibition. Others have proposed that that during sequential or concomitant combinations, E2F-1 activity may actually be reduced, based on effects on retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Reduced E2F-1 activity is expected to compromise the transcription of genes encoding the M2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase or thymidylate synthetase [96]. In these instances, resistance to agents such as gemcitabine or fluorouracil may be compromised, augmenting the effects of the primary chemotherapy.

It is possible that variables in experimental conditions, including differences in cell lines, cdk inhibitor concentrations and intervals between agents may account for differences in the modulation of E2F-1 activity observed in these experiments. Similar variability has been observed in the response of different cell lines exposed concomitantly to roscovitine and doxorubicin [52]. In some cell lines, roscovitine increases G2 in cells, inhibits end resection and HR and NHEJ and sensitizes cells to doxorubicin, with increased frequency of DSBs and cell death. The net effect of roscovitine impairs HR, despite the possible adverse effects of affecting the BRCA2–Rad51 interaction. In other cell lines, the G1 cell cycle inhibitory capacity of roscovitine prevails, such that cells are prone to senescence and ultimate protection from DNA damage. Therefore, among Rb-positive cell lines, the degree of retinoblastoma dephosphorylation and presumed reduction in E2F-1 activity varies in response to a cdk-inhibitor–DNA-damaging-agent combination. G1 arrest and reduced E2F-1 activity may lead to increased survival in response to DNA damage, or may favorably affect cytotoxicity if the transcription of relevant genes encoding proteins that confer chemotherapy resistance is decreased. In summary, the modulation of E2F-1 activity in cells exposed to combinations of cdk inhibitors and DNA-damaging agents is complex, and multiple mechanisms may contribute to any potential therapeutic benefit afforded by the addition of cdk inhibition.

Interestingly, small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) cells, or other cells that lack functional Rb protein, may be particularly prone to cdk-inhibitor–DNA-damaging-agent combinations, since G1 arrest is not an outcome in these cells [97,98]. Here, cdk-inhibitor-mediated-S phase accumulation and modulation of E2F-1 activity during S phase, coupled with impaired DNA repair processes in response to DSBs, may together produce substantial antitumor effects. In flavopiridol–doxorubicin combinations, sequence-specificity was not critical for in vitro synergism; in fact, flavopiridol followed by doxorubicin resulted in greater apoptosis, and greater efficacy in xenograft models with better tolerability than the opposite sequence [97]. Both gemcitabine and adriamycin-based combinations with flavopir-idol remain under investigation, but have not been specifically evaluated in Rb-negative tumors [99].

4.3 Transcriptional cdk inhibition in combination with DNA damaging agents

Although homologous recombination is considered an error-free repair mechanism, its upregulation can lead to genomic instability, such that p53 plays a role in its suppression, in an activity separable from its classic tumor suppressor functions [100,101]. In p53 wild type colon cancer cells, flavopiridol enhances the degree of p53 accumulation following exposure to camptothecin-mediated DNA damage. This is probably due to flavopiridol-mediated depletion of Mdm2 mRNA and protein, facilitating p53 accumulation [102,103]. Initially, phosphorylated p53 binds and inhibits Rad51, and then ultimately mediates transcriptional repression of Rad51. This inhibition of DNA repair caused by flavopiridol therefore augments camptothecin-induced apoptosis in p53 wild type cells [104].

In addition, while promoting the accumulation of wild-type p53, flavopiridol-mediated cdk9 inhibition may deplete cells of p21Waf1/Cip1 mRNA and protein in response to DNA damage. This may change the balance between p53-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, and further promote an apoptotic response. Therefore, p53 wild-type HCT116 colon cancer cells exposed to irinotecan followed by flavopiridol demonstrated markedly increased cell death compared with those treated with either drug used alone [105]. Furthermore, preclinical modeling in xenograft models defined a 7-h interval between irinotecan and flavopiridol as optimal.

These mechanisms may contribute to the efficacy afforded by the irinotecan/flavopiridol sequential combination in gastrointestinal malignancies [106]. Here, partial responses were noted in patients with gastric and colorectal cancer and prolonged stable disease in 36% of all patients and 52% of patients with colorectal cancer, irrespective of prior irinotecan exposure. Notably, clinical benefit appeared to be most pronounced in patients who had wild-type p53 tumors, or tumors in which there was no change or low p21Waf1/Cip1 in post-treatment compared with pre-treatment tumor biopsies.

Cells particularly prone to p53-mediated apoptosis, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells or malignant germ cells, may be particularly sensitive [107,108]. Recently, a Phase I study combining oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil with flavopiridol produced promising results in platinum-refractory germ cell tumors [109]. By immunohistochemical analysis, however, responses were seen in p53 mutant tumors, suggesting response in this case was governed by p53-independent mechanisms. Flavopiridol has also been successfully combined with cisplatin [110]. Analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in this study demonstrated modulation of p53 and STAT3 by flavopiridol, but not canonical cdk9 targets such as phospho-RNA polymerase II or Mcl-1, indicating that not all in vitro molecular targets are routinely affected in vivo. At this time, oxaliplatin and cisplatin flavopiridol combinations are undergoing continued evaluation in germ cell tumors and ovarian cancer, respectively.

4.4 Cdk-mediated cellular protection

Cell cycle arrest afforded by cdk inhibitors has recently been exploited to protect normal cells from radiation-induced hematologic toxicity [111,112]. PD0332991-mediated cdk4/6 inhibition induced pharmacological quiescence in proliferating hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, but not most other cycling cells in the bone marrow or other tissues. Selective pharmacological quiescence decreased the hematopoietic toxicity from total body irradiation, even when the cdk4/6 inhibitor was administered several hours later. Additionally, administration of PD0332991 at the time of therapeutic irradiation to TyrRasInk4a/Ar–/− mice, which harbor autochthonous melanomas, reduced treatment toxicity without compromising tumor therapeutic response. However, this result was achieved because the tumor model examined proliferated independently of cdk4/6 activity. Presumably, a tumor that could be arrested by cdk4/6 inhibition would also be rendered radioresistant. Nonetheless, this strategy may be useful in retinblastoma-negative tumors or Myc-overexpressing tumors that would be expected to proliferate despite cdk4/6 inhibition and hence retain radiosensitivity [112].

5. Conclusions

In both yeast and mammalian cells, cdks have recently been shown to have multiple roles in the activation of DNA damage checkpoint and repair pathways [33]. In mammalian cells, cdk2 and cdk1 are necessary for the activation of DNA end-resection at sites of DSBs through phosphorylation of CtIP [36]. They also regulate DNA damage checkpoint and repair pathways through phosphorylation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 [35,48]. Roles for additional cdk family members in the DNA-damage-response pathway are also emerging. Cdk5 phosphorylates and activates ATM in post-mitotic neurons [42], and siRNA knockdown of cdk5 sensitizes to PARP inhibition in non-neuronal cells [43]. p53-mediated suppression of HR, a component of its tumor suppressive function [100,101], may be exploited by cdk9 inhibitors that stabilize p53 via depletion of Mdm2 mRNA and protein [103]. Therefore, inhibition of other cdk family members may also sensitize cancer cells to DNA-damaging therapy. Clinical trials combining cdk inhibitors and DNA damaging chemotherapy have produced antitumor responses in solid tumors. However, the contribution of cdk inhibition to the antitumor activity in these combinations has not yet been assessed in randomized clinical trials.

6. Expert opinion

To date, the clinical employment of cdk-inhibitor–DNA-damaging-chemotherapy combinations, have in the majority of cases, used flavopiridol to inhibit cdk activity, which is a pan cdk inhibitor that most potently inhibits cdk9. Efforts are currently ongoing to develop more potent and selective cdk9 or cdk7 inhibitors, either for single agent use or combination therapy [113]. However, emerging data suggests that cdk1 or cdk2 may be the most appropriate family members to target in combination with DNA-damaging agents [33,35,40,58]. In addition, difficulties overcoming the cell-cycle-mediated chemotherapy resistance in patients, in contrast to cell lines, may limit the efficacy of flavopiridol–chemotherapy combinations in the treatment of solid tumors. It is possible that alterations in dosing schedules may provide maximal activity of combination therapy. Newer, more potent generation cdk inhibitors with similar mechanisms of action to flavopiridol may also enhance therapeutic regimens.

For the treatment of solid tumors, randomized trials will be required to determine whether flavopiridol-mediated cdk inhibition contributes to any observed anti-tumor activity. However, a new approach to combination therapy may be necessary, with recent data from yeast and mammalian cancer cell lines highlighting cdk1 and cdk2 as the most likely targets to augment the therapeutic benefit of DNA-damaging agents. In a variety of human cell types, abrogation of individual cdk 1 or 2 activity results in defective DNA-damage-response pathways. Therefore, specific inhibitors of either cdk1 or cdk2 could optimize cdk-inhibitor–DNA-damage-chemotherapeutic regimens for treatment of cancer.

Previously, the development of specific inhibitors of cdk2 and cdk1 was hampered by data suggesting that these cdks may not be appropriate targets for the treatment of cancer. Studies demonstrating siRNA-mediated cdk2 depletion has little effect on colon and osteosarcoma cancer cell line proliferation [114], and that cdk2 knockout mice are viable [115,116], reduced enthusiasm for cdk2-specific inhibitors in pharmaceutical pipelines. In addition, cdk1-knockout mice are not viable and die in early stages of embryogenesis [117], suggesting that cdk1 inhibitors could be toxic to normal cells. However, recently it has been demonstrated that the differences between normal and cancer cells can be exploited by specific inhibitors of either cdk1 or 2, to sensitize cancer cells but protect normal cells from DNA damaging chemotherapy. For cell cycle progression, cdk1 and cdk2 can compensate for the loss of one another in cancer cells, facilitating proliferation and exposure to S-phase-acting DNA-damaging agents [118,119]. However, in non-transformed cells, cdk2 and cdk1 cannot compensate for one another as readily, so that in non-transformed cells, cdk1 depletion or inhibition results in G2 cell cycle arrest, providing a means of cell-cycle-mediated resistance to S phase DNA damaging agents [35]. Furthermore, the observation that not all functions are compensated for by either cdk2 or cdk1 in cancer cells, such as BRCA1 phosphorylation in the absence of cdk1, demonstrates that cdk inhibition can also sensitize cancer cells to DNA damage by preventing checkpoint activation and DNA repair (Figure 2) [35].

The majority of cdk inhibitors available target both cdk2 and cdk1. Whether combined inhibition of cdk2 and cdk1 will successfully synergize with DNA-damaging agents remains to be fully explored. Combined cdk2/cdk1 inhibition can arrest cancer cells at the G2 boundary, potentially removing the advantage of selective cdk1 or cdk2 inhibition. However, combined cdk2/cdk1 inhibition can induce apoptosis in many cancer cell types as well, such that it is reasonable to pursue these combinations. Several inhibitors with activity against cdk2 and cdk1 other than flavopiridol have entered clinical trials. Development of AZD5438 was discontinued due to poor tolerability and exposure data [120]. However, AG024322 [121], seliciclib [67,122] and dinaciclib (SCH727965) [123,124] have been found to be tolerable in Phase I studies, the latter two compounds inhibiting cdk9 as well. Seliciclib is currently undergoing evaluation in combination with nucleoside analogs, including gemcitabine and sapacitabine [125], and dinaciclib-chemotherapy combinations are planned.

The development of small molecules that can selectively inhibit either cdk1 or cdk2 is likely to be challenging. Difficulties developing specific inhibitors of either cdk2 or cdk1 arise from the similarities between the ATP-catalytic sites of these enzymes. However, RO3306 is a small molecule that has been demonstrated to have 10-fold selectivity for cdk1 over cdk2 in in vitro kinase assays [65]. Problems with the clinical development of this compound have arisen from poor pharmacokinetic and solubility properties of this molecule; nonetheless, the inhibitory properties of this compound raise the possibility that highly selective cdk inhibitor agents can be identified.

Finally, evidence that inhibition of cdks interferes with BRCA1 and BRCA2 function suggests cdk inhibition and PARP inhibition may be synthetically lethal [46]. The disruption of BRCA function by cdk inhibition suggests that this strategy may provide a means for expanding the therapeutic utility of PARP-inhibitor monotherapy to the BRCA-wild-type cancer population. Therefore, cdk-inhibitor/PARP-inhibitor combinations should be evaluated preclinically to justify clinical trials.

In summary, the recent and continuing discovery of complex roles for cdk1 and cdk2 in augmentation and initiation of DNA damage checkpoint and repair pathways suggests that further work should proceed combining cdk inhibitors and DNA-damaging agents. Proof-of-mechanism trials will require the development of pharmacodynamic biomarkers, which could include assessment of BRCA1, ATRIP and Chk1 phosphorylation in tumor samples pre- and post-treatment. Development plans will also require long-term commitment, with Phase I trials to confirm safety, followed by randomized Phase II and III trials to fully determine the contribution of cdk inhibition to anti-tumor activity.

Article highlights.

Cdk activity has recently been demonstrated to contribute to multiple aspects of DNA damage checkpoint signaling and repair.

Processing of double stranded DNA breaks by the endonuclease – C-terminal binding protein-interacting protein (CtIP) is dependent on cdk activity.

Cdk activity is required for efficient BRCA1- and BRCA2-mediated DNA damage checkpoint signaling and repair.

Combing small-molecule cdk inhibitors with DNA-damaging chemotherapeutics can selectively kill cancer cells.

Clinical trials combining cdk inhibitors and DNA damaging agents have produced antitumor responses in solid tumors.

Selectively targeting either cdk1 or cdk2 may provide an optimal approach for cdk-inhibitor–DNA-damaging-agent combination therapy.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interest

The authors are supported by NIH grants R01 CA090687, P50 CA089393 [Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (DF/HCC) Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer], P50 CA090578 (DF/HCC SPORE in Lung Cancer) and Susan G Komen Post-Doctoral Fellowship Award KG080773. GI Shapiro receives funding for the conduct of clinical trials with cdk inhibitors, including trials sponsored by Schering-Plough (Merck) and Cyclacel, Ltd.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Meyerson M, Enders GH, Wu CL, et al. A family of human cdc2-related protein kinases. EMBO J. 1992;11:2909–17. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro GI. Cyclin-dependent kinase pathways as targets for cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1770–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:153–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pines J. The cell cycle kinases. Semin Cancer Biol. 1994;5:305–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinert T. A DNA damage checkpoint meets the cell cycle engine. Science. 1997;277:1450–1. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez Y, Wong C, Thoma S, et al. Conservation of the chk1 checkpoint pathway in mammals: linkage of DNA damage to cdk regulation through cdc25. Science. 1997;277:1497–501. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sausville EA. Complexities in the development of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor drugs. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:S32–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ewen ME. The cell cycle and the retinoblastoma protein family. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1994;13:45–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00690418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundberg AS, Weinberg RA. Functional inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein requires sequential modification by at least two distinct cyclin-cdk complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:753–61. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harbour JW, Luo RX, Dei Santi A, et al. Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell. 1999;98:859–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1149–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan DO. Principles of CDK regulation. Nature. 1995;374:131–4. doi: 10.1038/374131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akoulitchev S, Makela TP, Weinberg RA, Reinberg D. Requirement for TFIIH kinase activity in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nature. 1995;377:557–60. doi: 10.1038/377557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall NF, Peng J, Xie Z, Price DH. Control of RNA polymerase II elongation potential by a novel carboxyl-terminal domain kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27176–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterlin BM, Price DH. Controlling the elongation phase of transcription with P-TEFb. Mol Cell. 2006;23:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sims RJ III, Belotserkovskaya R, Reinberg D. Elongation by RNA polymerase II: the short and long of it. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2437–68. doi: 10.1101/gad.1235904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garriga J, Grana X. Cellular control of gene expression by T-type cyclin/ CDK9 complexes. Gene. 2004;337:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ni Z, Schwartz BE, Werner J, et al. Coordination of transcription, RNA processing, and surveillance by P-TEFb kinase on heat shock genes. Mol Cell. 2004;13:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–7. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall M, Peters G. Genetic alterations of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases, and cdk inhibitors in human cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1996;68:67–108. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abraham RT. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2177–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou L, Elledge SJ. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300:1542–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuoka S, Rotman G, Ogawa A, et al. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated phosphorylates Chk2 in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10389–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190030497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sartori AA, Lukas C, Coates J, et al. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 2007;450:509–14. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, et al. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [This research demonstrates that DNA end-resection is regulated by cdk activity and is required for ATR activation at a DSB.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartek J, Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:421–9. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foray N, Marot D, Gabriel A, et al. A subset of ATM- and ATR-dependent phosphorylation events requires the BRCA1 protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:2860–71. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yarden RI, Papa MZ. BRCA1 at the crossroad of multiple cellular pathways: approaches for therapeutic interventions. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1396–404. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valerie K, Povirk LF. Regulation and mechanisms of mammalian double-strand break repair. Oncogene. 2003;22:5792–812. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson SP. Sensing and repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:687–96. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonda E, Hochegger H, Saberi A, et al. Differential usage of non-homologus end-joining and homologus recombination in double strand break repair. DNA Repair. 2006;5:1021–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33•.Ira G, Pellicioli A, Balijja A, et al. DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature. 2004;431:1011–17. doi: 10.1038/nature02964. [The first paper, to our knowledge, to describe a crucial role for cdk1 in HR and checkpoint control in yeast.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scully R, Xie A. In my end is my beginning: control of end resection and DSBR pathway ‘choice’ by cyclin-dependent kinases. Oncogene. 2005;24:2871–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35•.Johnson N, Cai D, Kennedy RD, et al. Cdk1 participates in BRCA1-dependent S phase checkpoint control in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2009;35:327–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.036. [This research demonstrates that cdk1 phosphorylates BRCA1 at S1189/ S1191 and S1497, events necessary for BRCA1-mediated S phase checkpoint control.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huertas P, Jackson SP. Human CtIP mediates cell cycle control of DNA end resection and double strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9558–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808906200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myers JS, Zhao R, Xu X, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 dependent phosphorylation of ATRIP regulates the G2-M checkpoint response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6685–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anantha RW, Vassin VM, Borowiec JA. Sequential and synergistic modification of human RPA stimulates chromosomal DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35910–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.West SC. Molecular views of recombination proteins and their control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:435–45. doi: 10.1038/nrm1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Deans AJ, Khanna KK, McNees CJ, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 functions in normal DNA repair and is a therapeutic target in BRCA1-deficient cancers. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8219–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3945. [This research demonstrates that cdk2 activity is required for checkpoint activation and DNA repair in MCF7 breast cancer cells.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cerqueira A, Santamaria D, Martinez-Pastor B, et al. Overall Cdk activity modulates the DNA damage response in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:773–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian B, Yang Q, Mao Z. Phosphorylation of ATM by Cdk5 mediates DNA damage signalling and regulates neuronal death. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:211–18. doi: 10.1038/ncb1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner NC, Lord CJ, Iorns E, et al. A synthetic lethal siRNA screen identifying genes mediating sensitivity to a PARP inhibitor. EMBO J. 2008;27:1368–77. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yun MH, Hiom K. CtIP-BRCA1 modulates the choice of DNA double-strand-break repair pathway throughout the cell cycle. Nature. 2009;459:460–3. doi: 10.1038/nature07955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen L, Nievera CJ, Lee AY, Wu X. Cell cycle-dependent complex formation of BRCA1.CtIP.MRN is important for DNA double-strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7713–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson N, Li Y-C, Moreau LA, et al. Compromised cdk1 activity sensitizes BRCA-proficient cancer cells to inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase [abstract]. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2010;51:A3882. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kehn K, Berro R, Alhaj A, et al. Functional consequences of cyclin D1/ BRCA1 interaction in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:5060–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Esashi F, Christ N, Gannon J, et al. CDK-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA2 as a regulatory mechanism for recombinational repair. Nature. 2005;434:598–604. doi: 10.1038/nature03404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashworth A. A synthetic lethal therapeutic approach: poly(ADP) ribose polymerase inhibitors for the treatment of cancers deficient in DNA double-strand break repair. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3785–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aaltonen K, Blomqvist C, Amini RM, et al. Familial breast cancers without mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 have low cyclin E and high cyclin D1 in contrast to cancers in BRCA mutation carriers. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1976–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chappuis PO, Donato E, Goffin JR, et al. Cyclin E expression in breast cancer: predicting germline BRCA1 mutations, prognosis and response to treatment. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:735–42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crescenzi E, Palumbo G, Brady HJM. Roscovitine modulates DNA repair and senescence: implications for combination chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8158–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muller-Tidow C, Ji P, Diederichs S, et al. The cyclin A1-CDK2 complex regulates DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8917–28. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8917-8928.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frouin I, Toueille M, Ferrari E, et al. Phosphorylation of human DNA polymerase lambda by the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk2/cyclin A complex is modulated by its association with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5354–61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wimmer U, Ferrari E, Hunziker P, Hubscher U. Control of DNA polymerase lambda stability by phosphorylation and ubiquitination during the cell cycle. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1027–33. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu Y, Alvarez C, Doll R, et al. Intra-S-phase checkpoint activation by direct CDK2 inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6268–77. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6268-6277.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu Y, Ishimi Y, Tanudji M, Lees E. Human CDK2 inhibition modifies the dynamics of chromatin-bound minichromosome maintenance complex and replication protein A. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1254–63. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58•.Maude SL, Enders GH. Cdk inhibition in human cells compromises chk1 function and activates a DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2005;65:780–6. [This research demonstrates that cdk2 activity is required to maintain Chk1 protein levels and cdk2 inhibition activates a DNA damage response.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Enders GH. Expanded roles for Chk1 in genome maintenance. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17749–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800021200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sedlacek HH, Czech J, Naik R, et al. Flavopiridol (L86 8275; NSC 649890), a new kinase inhibitor for tumor therapy. Int J Oncol. 1996;9:1143–68. doi: 10.3892/ijo.9.6.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sedlacek HH. Mechanisms of action of flavopiridol. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;38:139–70. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shapiro GI. Preclinical and clinical development of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4270s–4275s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-040020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Toogood PL, Harvey PJ, Repine JT, et al. Discovery of a potent and selective inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2388–406. doi: 10.1021/jm049354h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fry DW, Harvey PJ, Keller PR, et al. Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 by PD 0332991 and associated antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1427–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vassilev LT, Tovar C, Chen S, et al. Selective small-molecule inhibitor reveals critical mitotic functions of human CDK1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10660–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600447103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McClue SJ, Blake D, Clarke R, et al. In vitro and in vivo antitumor properties of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor CYC202 (R-roscovitine). Int J Cancer. 2002;102:463–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aldoss IT, Tashi T, Ganti AK. Seliciclib in malignancies. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:1957–65. doi: 10.1517/13543780903418445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Misra RN, Xiao HY, Kim KS, et al. N-(cycloalkylamino)acyl-2-aminothiazole inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 2. N-[5-[[[5-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-2-oxazolyl] methyl]thio]-2-thiazolyl]-4-piperidinecarboxamide (BMS-387032), a highly efficacious and selective antitumor agent. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1719–28. doi: 10.1021/jm0305568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paruch K, Dwyer MP, Alvarez C, et al. Discory of dinaciclib (SCH 727965): a potent and selective inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kianses. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2010;1:204–8. doi: 10.1021/ml100051d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parry D, Guzi T, Shanahan F, et al. Dinaciclib (SCH 727965), a novel and potent cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2344–53. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lam LT, Pickeral OK, Peng AC, et al. Genomic-scale measurement of mRNA turnover and the mechanisms of action of the anti-cancer drug flavopiridol. Genome Biol. 2001:2. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-10-research0041. research 0041.1-41.11: published online 13 September 2001, doi:10.1186/gb-2001-2-10-research0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chao SH, Fujinaga K, Marion JE, et al. Flavopiridol inhibits P-TEFb and blocks HIV-1 replication. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28345–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chao SH, Price DH. Flavopiridol inactivates p-TEFb and blocks most RNA polymerase II transcription in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31793–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Azevedo WF, Canduri F, da Silveira NJ. Structural basis for inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 9 by flavopiridol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:566–71. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Byrd JC, Lin TS, Dalton JT, et al. Flavopiridol administered as a pharmacologically-derived schedule demonstrates marked clinical activity in refractory, genetically high risk, chronic lymphocytic leukemia [abstract 341]. Blood. 2004;104:101a. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christian BA, Grever MR, Byrd JC, Lin TS. Flavopiridol in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a concise review. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9(Suppl 3):S179–85. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2009.s.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tong WG, Chen R, Plunkett W, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of SNS-032, a potent and selective Cdk2, 7, and 9 inhibitor, in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia and multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3015–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen R, Keating MJ, Gandhi V, Plunkett W. Transcription inhibition by flavopiridol: mechanism of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell death. Blood. 2005;106:2513–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hsieh WS, Soo R, Peh BK, et al. Pharmacodynamic effects of seliciclib, an orally administered cell cycle modulator, in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1435–42. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dzhagalov I, St John A, He YW. The antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 is essential for the survival of neutrophils but not macrophages. Blood. 2007;109:1620–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Du J, Widlund HR, Horstmann MA, et al. Critical role of CDK2 for melanoma growth linked to its melanocyte-specific transcriptional regulation by MITF. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:565–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Molenaar JJ, Ebus ME, Geerts D, et al. Inactivation of CDK2 is synthetically lethal to MYCN over-expressing cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12968–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901418106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Puyol M, Martin A, Dubus P, et al. A synthetic lethal interaction between K-Ras oncogenes and Cdk4 unveils a therapeutic strategy for non-small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shah MA, Schwartz GK. Cell cycle-mediated drug resistance: an emerging concept in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2168–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaur G, Stetler-Stevenson M, Sebers S, et al. Growth inhibition with reversible cell cycle arrest of carcinoma cells by Flavone L86-8275. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:1736–40. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.22.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carlson BA, Dubay MM, Sausville EA, et al. Flavopiridol induces G1 arrest with inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)2 and CDK4 in human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2973–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bible KC, Kaufmann SH. Cytotoxic synergy between Flavopiridol and various antineoplastic agents: the importance of sequence of administration. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3375–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Matranga CB, Shapiro GI. Selective sensitization of transformed cells to flavopiridol-induced apoptosis following recruitment to S-phase. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1707–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jiang J, Matranga CB, Cai D, et al. Flavopiridol-induced apoptosis during S phase requires E2F-1 and inhibition of cyclin A-dependent kinase activity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7410–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ma Y, Cress D, Haura EB. Flavopiridol-induced apoptosis is mediated through up-regulation of E2F-1 and repression of Mcl-1. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Krek W, Ewen ME, Shirodkar S, et al. Negative regulation of the growth-promoting transcription factor E2F-1 by a stably bound cyclin A-dependent protein kinase. Cell. 1994;78:161–72. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dynlacht BD, Flores O, Lees JA, Harlow E. Differential regulation of E2F transactivation by cyclin-cdk2 complexes. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1772–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.15.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xu M, Sheppard KA, Peng CY, et al. Cyclin A/Cdk2 binds directly to E2F-1 and inhibits the DNA-binding activity of E2F-1/DP-1 by phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8420–31. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen W, Lee J, Cho SY, Fine HA. Proteasome-mediated destruction of the cyclin A/cyclin-dependent kinase 2 complex suppresses tumor cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3949–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen YN, Sharma SK, Ramsey TM, et al. Selective killing of transformed cells by cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase 2 antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4325–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jung CP, Motwani MV, Schwartz GK. Flavopiridol increases sensitization to gemcitabine in human gastrointestinal cancer cell lines and correlates with down-regulation of the ribonucleotide reductase M2 subunit. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2527–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Budak-Alpdogan T, Chen B, Warrier A, et al. Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene expression determines the response to sequential flavopiridol and doxorubicin treatment in small-cell lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1232–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li W, Fan J, Bertino JR. Selective sensitization of retinoblastoma protein-deficient sarcoma cells to doxorubicin by flavopiridol-mediated inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 kinase activity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2579–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Goffin J, Appleman L, Ryan D, et al. A Phase I trial of gemcitaibne followed by flavopiridol in patients with solid tumors [abstract]. Lung Cancer. 2003;41:S179. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bertrand P, Saintigny Y, Lopez BS. p53′s double life: transactivation-independent repression of homologous recombination. Trends Genet. 2004;20:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gatz SA, Wiesmuller L. p53 in recombination and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1003–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Alonso M, Tamasdan C, Miller DC, Newcomb EW. Flavopiridol induces apoptosis in glioma cell lines independent of retinoblastoma and p53 tumor suppressor pathway alterations by a caspase-independent pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:139–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. Flavopiridol induces p53 via initial inhibition of Mdm2 and p21 and, independently of p53, sensitizes apoptosis-reluctant cells to tumor necrosis factor. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3653–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ambrosini G, Seelman SL, Qin LX, Schwartz GK. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol potentiates the effects of topoisomerase I poisons by suppressing Rad51 expression in a p53-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2312–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Motwani M, Jung C, Sirotnak FM, et al. Augmentation of apoptosis and tumor regression by flavopiridol in the presence of CPT-11 in Hct116 colon cancer monolayers and xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:4209–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shah MA, Kortmansky J, Motwani M, et al. A Phase I clinical trial of the sequential combination of irinotecan followed by flavopiridol. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3836–45. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jackman KM, Frye CB, Hunger SP. Flavopiridol displays preclinical activity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:772–8. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mayer F, Mueller S, Malenke E, et al. Induction of apoptosis by flavopiridol unrelated to cell cycle arrest in germ cell tumour derived cell lines. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:205–11. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-6728-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rathkopf D, Dickson MA, Feldman DR, et al. Phase I study of flavopiridol with oxaliplatin and fluorouracil/leucovorin in advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7405–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bible KC, Lensing JL, Nelson SA, et al. Phase 1 trial of flavopiridol combined with cisplatin or carboplatin in patients with advanced malignancies with the assessment of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic end points. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5935–41. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stone S, Dayananth P, Kamb A. Reversible, p16-mediated cell cycle arrest as protection from chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Johnson SM, Torrice CD, Bell JF, et al. Mitigation of hematologic radiation toxicity in mice through pharmacological quiescence induced by CDK4/6 inhibition. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2528–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI41402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dickson MA, Schwartz GK. Development of cell-cycle inhibitors for cancer therapy. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:36–43. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i2.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Proliferation of cancer cells despite cdk2 inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:233–45. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ortega S, Prieto I, Odajima J, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 is essential for meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice. Nat Genet. 2003;35:25–31. doi: 10.1038/ng1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Berthet C, Aleem E, Coppola V, et al. Cdk2 knockout mice are viable. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1775–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Santamaria D, Barriere C, Cerqueira A, et al. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature. 2007;448:811–15. doi: 10.1038/nature06046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cai D, Latham VM, Jr, Zhang X, Shapiro GI. Combined depletion of cell cycle and transcriptional cyclin-dependent kinase activities induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9270–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.L'Italien L, Tanudji M, Russell L, Schebye XM. Unmasking the redundancy between Cdk1 and Cdk2 at G2 phase in human cancer cell lines. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:984–93. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.9.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Boss DS, Schwartz GK, Middleton MR, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the oral cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor AZD5438 when administered at intermittent and continuous dosing schedules in patients with advanced solid tumours. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:884–94. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Brown AP, Courtney CL, Criswell KA, et al. Toxicity and toxicokinetics of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor AG-024322 in cynomolgus monkeys following intravenous infusion. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62:1091–101. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0771-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Benson C, White J, De Bono J, et al. A Phase I trial of the selective oral cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor seliciclib (CYC202; R-Roscovitine), administered twice daily for 7 days every 21 days. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:29–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Shapiro GI, Bannerji R, Small K, et al. A Phase I dose-escalation study of the safety, pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of the novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor SCH727965 administered every 3 weeks in subjects with advanced malignancies [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2008;26:A3532. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nemunaitis J, Saltzman M, Rosenberg MA, et al. A Phase I dose-escalation study of the safety, pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of SCH727965, a novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, administered weekly in subjects with advanced malignancies [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27:A3535. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Galmarini CM. Drug evaluation: sapacitabine--an orally available antimetabolite in the treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;7:565–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]