Abstract

Trypanosoma brucei has a complex life cycle during which its single mitochondrion is subjected to major metabolic and morphological changes. While the procyclic stage (PS) of the insect vector contains a large and reticulated mitochondrion, its counterpart in the bloodstream stage (BS) parasitizing mammals is highly reduced and seems to be devoid of most functions. We show here that key Fe-S cluster assembly proteins are still present and active in this organelle and that produced clusters are incorporated into overexpressed enzymes. Importantly, the cysteine desulfurase Nfs, equipped with the nuclear localization signal, was detected in the nucleolus of both T. brucei life stages. The scaffold protein Isu, an interacting partner of Nfs, was also found to have a dual localization in the mitochondrion and the nucleolus, while frataxin and both ferredoxins are confined to the mitochondrion. Moreover, upon depletion of Isu, cytosolic tRNA thiolation dropped in the PS but not BS parasites.

INTRODUCTION

Trypanosoma brucei is a protozoan parasite causing human African trypanosomiasis and related diseases in cattle, camels, water buffalos, and horses. The bloodstream stage (BS) infects mammalian blood and subcutaneous tissues and is transmitted to another host via a tsetse fly vector, where it prospers as the so-called procyclic stage (PS) (1). As an adaptation to the distinct host environments, these two major life stages differ significantly in their morphology and metabolism. One of the most striking differences between them rests in the single mitochondrion, which is large and reticulated in the PS, maintaining all canonical functions, whereas the same organelle in the BS is significantly reduced, with only a few pathways having been detected so far. In order to recapitulate the situation, we present here a short summary of known and verified mitochondrial pathways in the BS.

Out of all 14 mitochondrial gene products, only subunit A6 of ATPase is translated and utilized in the BS as an indispensable part of respiratory complex V, which is present and active, even though it does not fulfill its standard function (2, 3). Hence, translation is indispensable (4, 5). Since the A6 transcript undergoes extensive RNA editing, the entire RNA processing machinery is active and essential in the BS as well (6, 7). In addition, since no tRNAs are encoded in the mitochondrial DNA (kinetoplast DNA [kDNA]), their import from the cytosol and modifications are mandatory for mitochondrial translation (4, 8). Ultimately, the import of hundreds of nucleus-encoded mitochondrial proteins involved in protein import and processing, kDNA replication and maintenance, kRNA transcription and processing, and translation are indispensable in the BS (3, 4, 9, 10). In contrast to a typical mitochondrion, the BS organelle does not serve as the main energy source. Instead of the canonical respiratory chain, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase supplies electrons to trypanosome alternative oxidase as a terminal electron acceptor (11). While cytochrome c-dependent respiratory complexes III and IV are altogether missing from the BS, complex II probably remains active. Moreover, complex I is expressed, yet its enzymatic activity is not significant, and its real function remains elusive (12–15). Complex V (ATP synthase) is present, but its F1 part rotates in the reverse direction compared to the PS, cleaving ATP and pumping H+ out of the mitochondrion in order to create the membrane potential required for protein import (2).

The efficiency of fatty acids synthesis in the BS organelle via type II pathway is unclear, since its main product, lipoic acid, is present only in a very small amount and there is no apparent use for it (16), although disruption of the biosynthesis caused defects in kDNA segregation (17). Furthermore, the degradation of fatty acids was transferred from the mitochondrion into the glycosomes in all trypanosomatid flagellates (15).

In most eukaryotic cells, mitochondria have a central role in Ca2+ homeostasis, yet in trypanosomes, this key role is questionable due to the presence of acidocalcisomes (15, 18). Although the mitochondrial calcium uniporter is present in both stages (19), its role in the BS mitochondrion, devoid of citric acid cycle and respiratory chain, remains elusive (15, 19, 20). On the other hand, K+ ion homeostasis is essential for the mitochondrion and subsequently for the whole cell (20). Other typical mitochondrial functions, such as citric acid cycle, urea cycle, role in apoptosis, and biosynthesis of ubiquinol and heme, are likely absent from the reduced BS mitochondrion (3, 15, 21–23).

Finally, all mitochondria studied so far exhibit biosynthesis of Fe-S clusters, ubiquitous and very ancient enzymatic cofactors (24). Their capacity to transfer electrons is used in complexes I to III of the respiratory chain or metabolic enzymes such as aconitase, fumarase, and lipoate synthase (25, 26). In addition, Fe-S clusters are utilized in iron metabolism, serve in DNA replication, and have structural or other functions (25). These cofactors are synthesized via a complex pathway composed of more than 20 enzymes, and as detailed below, most of them are present in T. brucei (27–31).

Cysteine desulfurase (Nfs) abstracts sulfur from cysteine, producing alanine, while ferredoxin provides electrons obtained from NADH by ferredoxin reductase (24). Frataxin is supposed to supply an iron atom; however, this role has still not been convincingly confirmed (26, 32, 33). The assembly of a new Fe-S cluster occurs on a large protein complex composed of Nfs, its indispensable interacting partner Isd11, and the scaffold protein Isu (24). In mammals, frataxin is also present in this complex (34), yet this was not confirmed for trypanosomes (27). The newly formed cofactors are transferred by numerous chaperons and scaffold proteins, which either transfer them to the mitochondrial apoproteins or export a so-far-unknown intermediate from the organelle that is further processed and exploited for the cytosolic and nuclear Fe-S-dependent proteins (24–26).

Most key components of the mitochondrial Fe-S biosynthetic pathway are essential for the PS of T. brucei. RNA interference (RNAi) depletion of Nfs, Isd11, Isu, Isa1, Isa2, and frataxin resulted in drastic changes in growth phenotypes, decreases in the activity of several Fe-S enzymes, and other downstream effects (27–29, 31, 35). In addition, Nfs and Isd11 are also indispensable for tRNA thiolation (27). Two homologues of the electron donor protein ferredoxin were identified in the genomes of trypanosomatid flagellates, but only ferredoxin A is essential for the Fe-S cluster assembly (31).

However, no functional data are available on this pathway in the BS other than that the level of its components is much lower than that in the PS, as has been shown for frataxin (35), Isd11 (27), ferredoxin (31), and Isa1 and Isa2 (29). In general, the (in)dispensability of Fe-S machinery in the BS mitochondrion is questionable, since the bulk of Fe-S clusters produced in the organelle of a typical eukaryotic cell are utilized for its respiratory chain complexes, which are either repressed or absent in this life stage of T. brucei. To the best of our knowledge, the only Fe-S-dependent proteins still expressed are ferredoxin A and glutaredoxin 1, both involved in the Fe-S pathway itself (31, 36), which implies that they are present only in a very small amount and pose a “chicken-or-the-egg”-type problem. Moreover, there is Fe-S-dependent lipoic acid synthetase, but, as mentioned above, the relevance of lipoic acid synthesis for the BS remains to be established (16, 17).

We scrutinized the localization of three core Fe-S assembly components, Nfs, Isu, and frataxin, using cell lines with tagged proteins and examined them by immunofluorescence microscopy and digitonin fractionation followed by Western blotting and electron microscopy. We were able to show that these proteins are located in the mitochondrion, yet in the case of Nfs and Isu, a substantial amount was detected in the nucleolus, suggesting that cysteine desulfurase with its scaffold protein must have a so-far-unknown function in this cell compartment. Since there is no detectable activity of the Fe-S-dependent enzymes aconitase and fumarase in the BS, we created cell lines overexpressing these marker Fe-S enzymes, which enabled us to verify that Fe-S proteins are produced in this unusual organelle and are capable of fulfilling their standard functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of pT7-v5 constructs.

Gene constructs with Nfs (TriTrypDB no. Tb927.11.1670), Isu (Tb927.9.11720), and frataxin (Tb927.3.1000) open reading frames (ORFs) lacking stop codons, followed by v5 or three-hemagglutinin (HA3) tags, were prepared using the following primer pairs: Nfs-v5-FP (5′ GGAAGCTTATGTTTAGTGGTGTTCGCGTAC) and Nfs-v5-RP (5′ TTAGATCTCCGCCACTCCACGTCTTTAAGG); Isu-v5-FP (5′AGGAAGCTTATGCGGCGACTGATATCATC) and Isu-v5-RP (5′AGGGATCCGCTTGACACCTCACC); and Frat-HA-FP (5′ ATAAAGCTTATGCGGCGCACATGTTGCGC) and Frat-HA-RP (5′ AGACTCGAGTTCGGTTTCTCCAGCCCCTG) (added BamHI and HindIII restriction sites are underlined).

PCR products amplified from the total genomic DNA of T. brucei PS 29-13 strain were cloned into pT7-v5 or pT7-HA3 vectors and verified by sequencing. The obtained constructs were linearized by NotI and electroporated into the parental PS 29-13 cells and the single-marker BS cells, the transfected cell lines were selected using puromycin (1 μg/ml), and expression of the tagged protein was induced by the addition of tetracycline (1 μg/ml). The cell line expressing v5-tagged ferredoxin A was described elsewhere (31).

Immunofluorescence assay.

Approximately 1 × 107 PS or BS cells were collected, centrifuged, resuspended in fresh medium, and stained with a 200 nM or 20 nM concentration, respectively, of the mitochondrion-selective dye Mitotracker red (Invitrogen). After 30 min incubation at 27°C or 37°C, the cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,300 × g at room temperature, and the pellet was washed and resuspended in 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 4% formaldehyde and 1.25 mM NaOH. The suspension (250 μl) was applied to a microscopic slide and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The slides were washed with PBS, incubated in ice-cold methanol for an additional 20 min, and briefly washed with PBS. Next, primary anti-v5 or anti-HA3 antibodies (Invitrogen) were added at a 1:100 dilution in PBS-Tween (0.05%) with 5% milk (Laktino, low fat; PML, Czech Republic) and incubated at 4°C overnight. Slides were washed with PBS prior to the application of Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes) at a 1:1,000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the samples were mounted with Antifade reagent with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen) and after incubation in the dark for 30 min were visualized using an Axioplan2 imaging fluorescence microscope (Zeiss).

Digitonin fractionation and Western blot analysis.

In order to compare protein expression in the PS versus BS, cell lysates corresponding to 5 × 106 cells per lane were separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane and probed with the polyclonal antibodies chicken anti-Nfs and rat anti-Isu at a 1:1,000 dilution and anti-enolase at a 1:50,000 dilution, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Sigma), and then visualized using the Pierce enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Thermo Scientific).

For the digitonin fractionation, 107 cells per sample were collected, incubated in STE-NaCl buffer (250 mM sucrose, 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl) with 0.04, 0.16, 0.32, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.2 mM digitonin for 4 min at 27°C. Subsequently, samples were centrifuged (16,000 × g for 2 min), and the supernatants obtained were used for Western blot analysis. For decorating of tagged proteins, monoclonal anti-mouse antibody (Sigma) was used at a 1:2,000 dilution. As controls, antibodies against the following proteins were used: the outer mitochondrial membrane protein VDAC (37), mitochondrial intermembrane sulfhydryl oxidase (38), the mitochondrial matrix protein MRP2 (39), the nuclear protein La (40), the glycosomal triosephosphate isomerase TIM424, and cytosolic enolase (both provided by Paul A. M. Michels).

Electron microscopy.

Cells were fixed either with 4% formaldehyde or 4% formaldehyde with 0.1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 1 h at room temperature. After centrifugation at 1,300 × g for 10 min, cells were washed three times in 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 0.01 M glycine. The pellet was resuspended in 10% gelatin dissolved in water at 37°C, centrifuged, and solidified on ice. Slices of gelatin-embedded pellet were immersed in 2.3 M sucrose and left for 6 days on a rotating wheel at 4°C. Infiltrated samples were immersed in liquid nitrogen and cryosectioned using a Leica EM FCS ultramicrotome (Leica) equipped with a cryochamber (Ultracut; Leica) at −100°C. Cryosections were picked up using a drop of solution containing 1% methyl cellulose and 1.15 M sucrose and thawed in PBS. Grids were placed on drops of blocking solution containing 5% low-fat milk and 0.02 M glycine in PBS for 2 h. Grids were transferred onto drops of mouse monoclonal antibody against the v5 tag (50 μg/ml; Invitrogen) diluted in blocking solution and left overnight at 4°C. Grids were washed in PBS containing 0.5% low-fat milk and incubated for 1 h in goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to 10-nm gold particles (Aurion) diluted 1:40 in blocking solution. Grids were then washed in PBS and distilled water, contrasted, and dried using 2% methyl cellulose with 3% aqueous uranyl acetate solution diluted at 9:1. Sections were examined in 80-kV JEOL 1010 and 200-kV 2100F transmission electron microscopes.

Controls were performed using anti-v5 tag labeling of both wild-type BS and PS cryosections under the same conditions as described above.

Quantification of gold labeling.

Electron micrographs of randomly selected areas were taken at the same magnification. A lattice of test points at constant distance of 100 nm was superimposed randomly on the micrographs using ImageJ software. Points and gold particles were counted separately within compartments: nucleus, nucleolus, mitochondrion, kDNA, and background (areas outside the above-mentioned compartments). Observed densities of labeling (LDobs) were expressed for each compartment as the sum of gold particles per sum of points. In order to statistically evaluate labeling of individual compartments, total expected numbers of gold particles for each compartment were calculated as total expected density (all gold particles divided by total points [total LDexp]) multiplied by total counts of points of each cell line. The chi-squared test was calculated as (LDobs − LDexp)2/LDexp. The relative labeling index (RLI) was calculated for each compartment as the ratio of observed labeling density value to expected labeling density (41).

RNAi construct, transfection, cloning, RNAi induction, and cultivation.

To prepare the Isu (Tb927.9.11720) RNAi construct, a fragment of the Isu ORF was amplified using the primer pair IscU-F1 (5′-CACCTCGAGCAGCCTCACTTCGGTCACT) and IscU-R1 (5′-TGCACGGATCCCCAACAGCCTCGGACTTAG) from total genomic DNA of T. brucei PS 29-13. The amplicon was cloned into the p2T7-177 vector, which was, upon NotI-mediated linearization, introduced into BS T. brucei single-marker cells using a BTX electroporator and selected as described elsewhere (42). The BS trypanosomes were cultivated in HMI-9 medium at 37°C in the presence of G418 (2.5 μg/ml) and phleomycin (2.5 μg/ml). RNAi was initiated by the addition of 1 μg/ml tetracycline to the medium, and growth measurements were made using the Beckman Z2 Coulter counter.

tRNA thiolation assay.

Total and mitochondrial RNA was electrophoretically separated on 8 M urea–8% acrylamide gels cast with 50 μM (N-acryloylamino)-phenyl mercuric chloride (APM). The samples were denatured by heating at 72°C for 2 min, and equal amounts (10 μg) of RNA were loaded per lane. After electrophoresis, the gels were stained with ethidium bromide for visualization under UV light, soaked in Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer containing 200 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and blotted onto a Zetaprobe membrane (Bio-Rad) for Northern blot analysis. Hydrogen peroxide treatment was carried out as a nonthiolated control as described elsewhere (27).

Expression and measurement of aconitase and fumarase in BS.

The ORFs of fumarase (Tb927.3.4500) and aconitase (Tb927.10.14000) were PCR amplified from the total genomic DNA of T. brucei PS 29-13 strain using the primer pairs TbAco-FW (5′-GGGTCTAGAATGCTCAGCACGATGAAGTT) and TbAco-RV (5′-GCGCTCGAGCTACTACAAATTACCCTTGAT) (added XbaI and XhoI restriction sites are underlined) and Tbcy-Fum-FW (5′-AGGAAGCTTATGAGTCTCTGCGAAAACTG) and Tbcy-Fum-RV (5′-ATATCTAGAGACGAGTTTAGCATAGAA) (added BamHI and HindIII restriction sites are underlined), and the PCR products were cloned into the pT7-v5 vector. The obtained vectors were linearized by NotI and electroporated into BS T. brucei single-marker cells using an Amaxa Nucleofector II electroporator, with puromycin (1 μg/ml) used as a selection marker. Expression of the ectopic proteins was induced by the addition of 1 μg/ml tetracycline.

Cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were obtained by digitonin fractionation following the protocol described elsewhere (28). The aconitase and fumarase activities were measured spectrophotometrically at 240 nm as the production rate of cis-aconitase and fumarate, respectively. l-Malic acid (Serva) and dl-isocitric acid trisodium salt hydrate (Sigma) were used as substrates in the aconitase and fumarase activity assays, respectively, as described previously (35).

RESULTS

Nfs contains a nuclear localization signal.

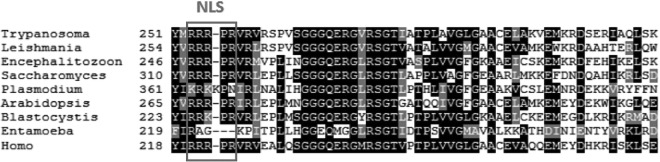

The cysteine desulfurase Nfs is a common mitochondrial protein found in almost all eukaryotes. An alignment of protein sequences of nine species from different eukaryotic supergroups revealed high conservation of key domains (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). A nuclear localization signal, RRRPR, was identified in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Nfs protein sequence (43) which is also present in the T. brucei sequence (Fig. 1). Even though a nuclear targeting sequence in trypanosomes was described only in a few cases (44–48), and no consensus sequence has been defined so far, the general rules postulating a high content of positively charged amino acids such as arginine seem to be universal. Thus, we hypothesize that the sequence RRRPR may function as a nuclear targeting signal in T. brucei as well. Moreover, the alignment showed absolute conservation of this motif in six of nine compared eukaryotes, including humans, with positively charged residues predominating in all aligned putative nuclear targeting signals (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Nuclear localization signal is present in Nfs from T. brucei and other eukaryotes. Multiple sequence alignment of the Nfs proteins from distantly related eukaryotes. The alignment was generated using ClustalW (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/ClustalW.html) and Boxshade (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html). Identical residues have a black background, and conserved residues have a gray background. The nuclear localization signal (NLS) identified in yeast is boxed (38). The following sequences were used: Trypanosoma brucei Tb927.11.1670, Homo sapiens NP_001185918.1, Saccharomyces cerevisiae NP_009912.2, Arabidopsis thaliana NP_201373.1, Leishmania mexicana XP_003876680.1, Plasmodium falciparum XP_001349169.1, Blastocystis hominis CBK24185.2, Encephalitozoon cuniculi NP_586483.1, and Entamoeba histolytica XP_655257.1.

Fe-S assembly proteins are present in the BS mitochondrion.

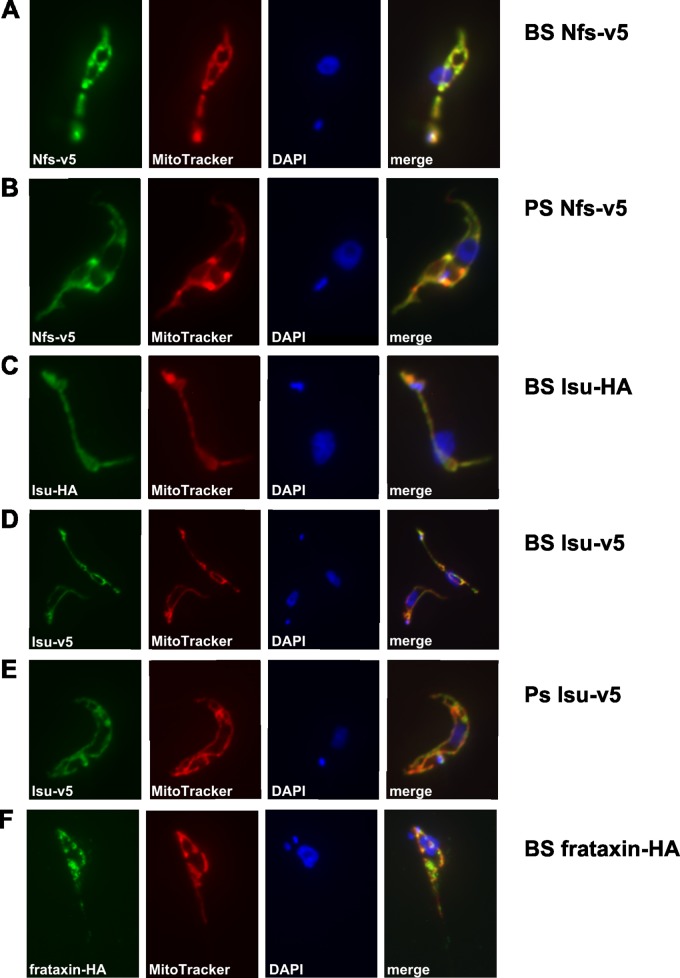

In order to establish localization of the Fe-S assembly machinery in the BS, we created cell lines overexpressing tagged versions of Nfs, Isu, and frataxin. Each of these genes was cloned into the pT7-v5 vector, and the obtained constructs were separately electroporated into the BS T. brucei. Since such an approach may cause nonphysiologically high expression of the tagged proteins, resulting in possible mislocalization within the cell, we also transfected the same constructs into the PS cells, where these proteins are known to localize to the mitochondrion (27, 28, 30). Upon decoration with monoclonal anti-v5 antibody and examination by immunofluorescence microscopy, in both the PS and BS trypanosomes expressing the v5-tagged Nfs, the signal was confined exclusively to the mitochondrion (Fig. 2A and B).

FIG 2.

Immunofluorescence analysis of tagged proteins in T. brucei BS and PS. The cells were stained with monoclonal anti-v5 and anti-HA antibodies (green), MitoTracker (red), and DAPI (blue). All target proteins were detected in mitochondria, as confirmed by colocalization with the MitoTracker signal. Identical results were obtained for the BS and PS cells and for the v5 and HA tags.

The same approach was used to detect the Isu protein in both life stages. Indeed, the fluorescent signal corresponded to the large reticulated and the dwindled sausage-shaped mitochondrion of the PS and BS cells, respectively (Fig. 2D and E). In order to eliminate potential artifacts caused by the v5-tagging strategy, an additional cell line was produced containing a HA3-tagged Isu. As with the other tag, the monoclonal anti-HA antibody decorated only the mitochondrion (Fig. 2C). Frataxin, the presumed iron donor for Fe-S clusters, has been functionally analyzed in PS (35) but not BS T. brucei so far. Therefore, we created a BS cell line expressing frataxin with added HA3 tag and showed by immunofluorescence microscopy its localization in the reduced mitochondrion of this life stage (Fig. 2F).

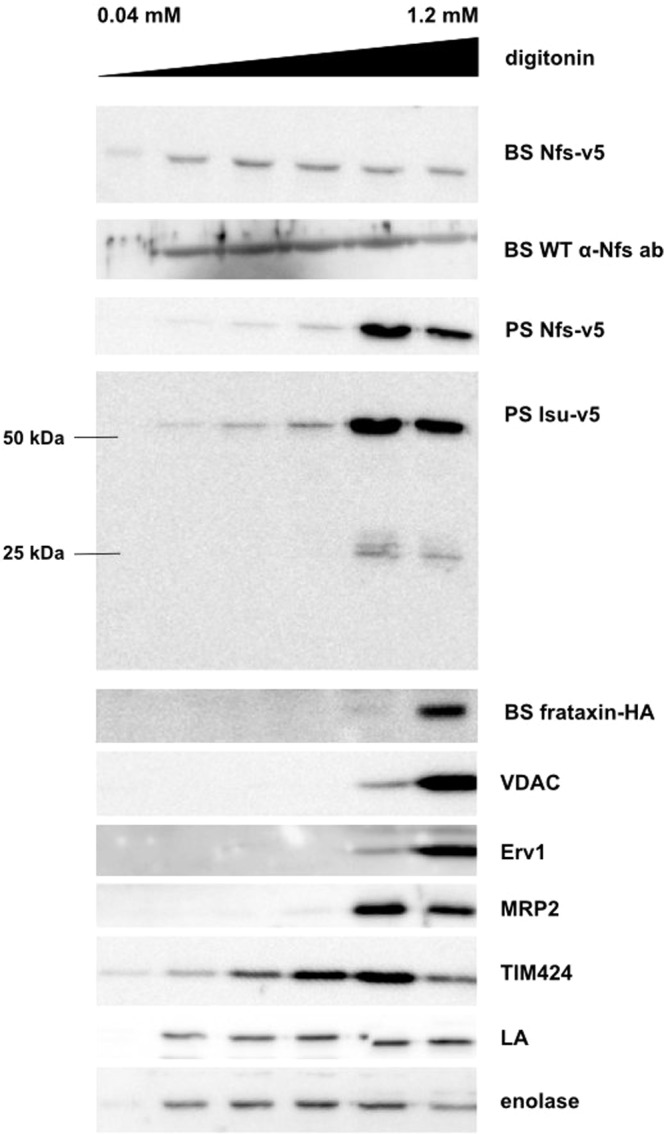

Digitonin fractionation reveals dual localization of Nfs.

An alternative approach to interrogate intracellular localization of a target protein is treatment of cells with the detergent digitonin, which disrupts phospholipid membranes and allows us to distinguish between subcellular compartments. For each cell line, subcellular fractions were obtained by using increasing concentrations of digitonin (0.04 to 1.2 mM) (Fig. 3). As shown by Western blotting analyses, the mitochondrial proteins were released only when a 0.8 mM or higher concentration of digitonin was used. All fractions were also treated with antibodies against the following control proteins: voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) of the outer mitochondrial membrane (37), sulfhydryl oxidase Erv1 of the intermembrane space (38), mitochondrial RNA-binding protein MRP2 in the mitochondrial matrix (39), glycosomal triose-phosphate isomerase (TIM424), nuclear protein La (40), and cytosolic enolase.

FIG 3.

Nfs and Isu proteins are present in the mitochondrion and in another subcellular compartment. Six samples were prepared from each cell line, incubated with increasing amount of digitonin, and centrifuged, and the supernatants obtained were used for Western blot analyses. Monoclonal anti-v5 and anti-HA antibodies were used for detection of the tagged proteins, and polyclonal anti-Nfs antibody was used to detect the endosomal protein. The mitochondrial membrane channel VDAC, the intermembrane protein Erv1, and the mitochondrial matrix protein MRP2 were used as mitochondrial controls; TIM424, the La protein, and enolase were used as glycosomal, nuclear, and cytosolic controls, respectively. These controls determined that mitochondrial proteins are present only in the last two fractions, but Nfs was released by lower concentrations of digitonin in both the BS and PS samples. Isu-v5 was detected in both the monomeric (25 kDa) and dimeric (50 kDa) forms. Again, the fraction of the signal was extramitochondrial. In the PS, the bulk of both proteins is present in the mitochondrion. The HA-tagged frataxin was detected solely in the mitochondrion-containing fractions.

When the Nfs-v5-expressing cells were used, the signal acquired with anti-v5 antibody differed from the pattern obtained with antibodies against the available mitochondrial markers (Fig. 3). Substantial fraction of the v5 signal was consistent with much earlier release of the tagged Nfs protein, suggesting localization also outside the double membrane-bound mitochondrion. Identical result was obtained when the specific anti-T. brucei Nfs antibody was used against BS WT cells (Fig. 3). Although in both PS and BS cells the target protein was detected in overlapping fractions, a much stronger signal was present in the last two PS fractions, strongly suggesting that in this life cycle stage, the majority of the Nfs protein is located in the mitochondrion. However, in the BS, the extramitochondrial signal was as strong as the organellar one (Fig. 3).

Western blot analysis of the PS lysates expressing the v5-tagged Isu revealed two separate bands, even though a monoclonal anti-v5 antibody was used (Fig. 3). Since the upper band corresponds to the double size of the lower band, we interpret these bands as the Isu dimer and monomer, respectively. Dimerization of components of the Fe-S assembly machinery was described for the mammalian cells (49), and apparently the complex was not effectively separated under the SDS-polyacrylamide gel conditions used. A strong signal of the 50-kDa band is present in the mitochondrial fractions, while a much weaker yet distinct signal in other fractions suggests the presence of Isu in additional subcellular compartments. The weak 25-kDa band is confined to the mitochondrial fractions (Fig. 3).

Finally, the BS cells containing HA3-tagged frataxin were analyzed by digitonin fractionation. The results were fully consistent with localization solely in the mitochondrial matrix (Fig. 3), which is in agreement with the data from the PS flagellates (30). Taken together, these results strongly indicate that Nfs and Isu are localized predominantly in the mitochondrion, but also in an additional subcellular compartment, possibly the nucleus.

Nfs and Isu are also present in the nucleolus.

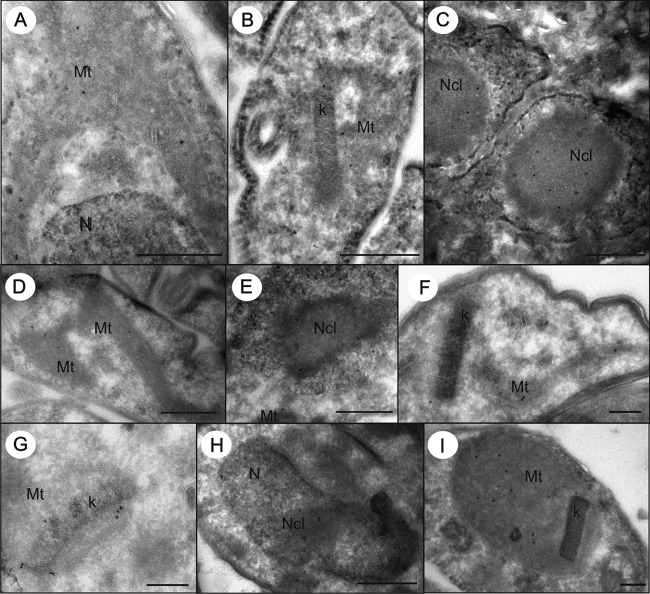

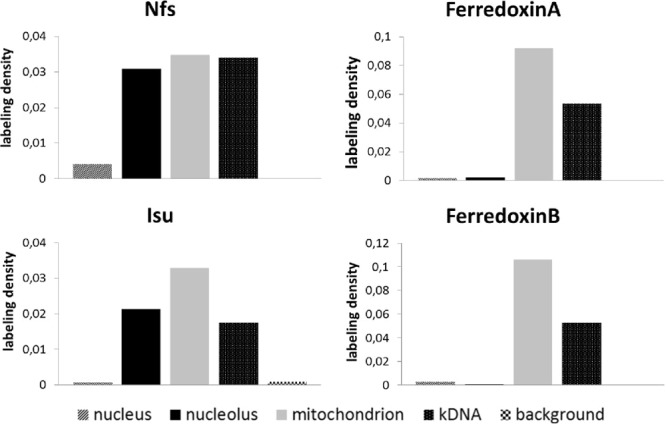

Next, we subjected the tagged cell lines to immunostaining with colloidal gold-labeled antibodies followed by transmission electron microscopy. This sensitive approach confirmed the presence of Nfs in the mitochondrion and the nucleolus of both PS (Fig. 4A to C) and BS (Fig. 4G and H) T. brucei. Nfs was detected in the mitochondrial lumen, with most signal being present in the vicinity of the kDNA disk, and in the nucleolus (Fig. 5). The same approach was applied to the PS cells expressing v5-tagged Isu, ferredoxin A, and ferredoxin B. Similarly, Isu was detected in the mitochondrial lumen and in the nucleolus (Fig. 4D to F and 5; also, see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast, ferredoxin A and ferredoxin B were present solely in the mitochondrion, with only a slight enrichment in the region around the kDNA (Fig. 4I and 5; also, see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 4.

T. brucei cells overexpressing v5-tagged Nfs or Isu were labeled with anti-v5 antibody. Immunolocalization of Nfs (A to C, G, and H) and Isu (D to F) in ultrathin cryosections of PS (A to F and I) and BS (G and H). The gold particles were detected in the mitochondrion (A and D), often associated with kDNA (B, F, and G), and in the nucleolus (C, E, and H). Ferredoxin B (I) was localized only in the mitochondrion of PS. Mt, mitochondrion; Nc, nucleolus; N, nucleus; k, kDNA. Bar, 500 nm (A to E and H) and 200 nm (F, G, and I).

FIG 5.

Statistical analysis of immunogold labeling on cryosections of PS. Nfs is present in the nucleolus and the mitochondrion, where half of the protein is associated with the kDNA. Similarly, Isu is present in the nucleolus and the mitochondrion, but with somewhat lower affinity for the kDNA. Ferredoxins A and B are present solely in the mitochondrion.

Specificity of the labeling protocol was proven by negative reactions of the anti-v5 tag antibody on cryosections of the BS and PS WT cells (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Moreover, the different distribution of the anti-v5 tag immunogold labeling in cells expressing either v5-tagged ferredoxin, Nfs, or Isu further supports the specificity of labeling and excludes a possible unspecific reaction of the anti-v5 tag antibody or the secondary gold conjugate. Since flagellates fixed with glutaraldehyde showed only a low efficiency of labeling with the v5-tag antibody, only results obtained with the formaldehyde-fixed cells are presented.

Observed and expected counts of gold particles were compared in order to distinguish preferential labeling (RLI > 1) from the random one (RLI = 1), and the data were examined using chi-squared (χ2) analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). We calculated partial (for each compartment and cell line) and total (sum of partials) χ2 values to test the null hypothesis (no difference between distributions). Values of partial χ2 indicate the responsibility of these compartments for the difference (preferential versus random distribution). Proportions of observed labeling densities over the mitochondria, nuclei, and nucleoli are summarized in Fig. 5. Thorough analysis of formaldehyde-fixed cryosections confirmed that Nfs and Isu are localized in the nucleolus, while only the former protein is significantly enriched in the vicinity of the kDNA disk in the mitochondrion. In contrast, both ferredoxins are confined solely to the mitochondrion (Fig. 5; also, see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Fe-S cluster assembly is an essential function of the BS mitochondrion.

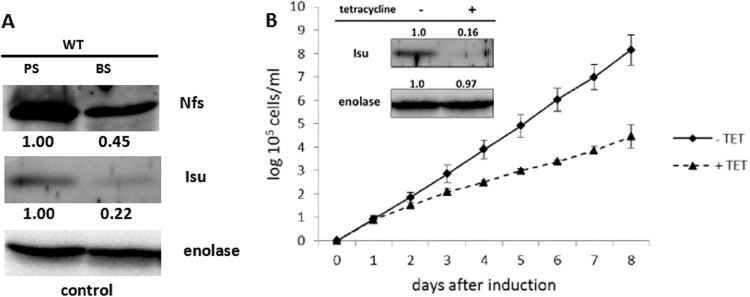

With regard to the differences between the large reticulated versus the reduced sausage-shaped mitochondria of the two life stages, it is not surprising that in the BS T. brucei, frataxin (35), ferredoxin A (31), and Isa1 and Isa2 proteins (29) are significantly less abundant than in the PS trypanosomes. The situation is very similar in the cases of Nfs and Isu, which are decreased two and five times, respectively, in the mammalian BS compared to the insect-dwelling PS (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Fe-S cluster assembly is diminished but essential in BS. (A) Samples containing the same numbers of cells were prepared from the PS and BS cells and analyzed by Western blotting. Nfs and Isu are expressed at 45% and 22%, respectively, in the BS compared to the PS. Enolase was used as a loading control. (B) Growth of the BS Isu RNAi cells in the absence (solid line) or presence (dashed line) of tetracycline was examined. After the induction, a significant growth defect was observed. The efficiency of RNAi was verified by Western blotting using anti-Isu antibody and enolase as a loading control (inset).

Importantly, the significance of the Fe-S cluster assembly in the disease-causing BS has not been established so far. In order to address this issue, a BS Isu RNAi cell line was constructed, where the depletion of Isu resulted in a severe growth phenotype (Fig. 6B). The efficiency of RNAi-mediated ablation of the target protein was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 6B, inset). Since except for its scaffold role in the Fe-S cluster synthesis, no other function is known for the Isu protein, we resorted to testing its possible function in tRNA thiolation (see below).

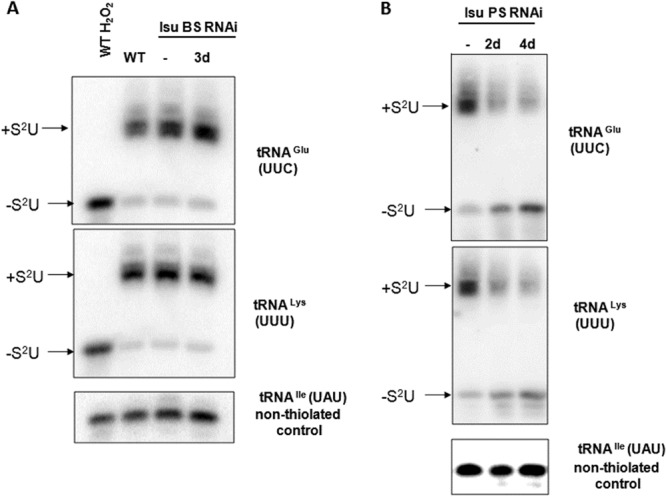

Cytosolic thiolation is downregulated in the PS but not in the BS Isu RNAi cells.

Since Isu is a binding partner of Nfs, which in T. brucei is also known as a source of sulfur for tRNA thiolation (27), we decided to study its potential role in this process as well. To our surprise, the thiolation of several cytosolic tRNAs remained unaltered upon the ablation of Isu in the BS (Fig. 7A). Therefore, we decided to also study the modification in PS Isu RNAi knockdowns, which were previously generated in our lab (28). Contrary to the BS data, thiolation is very sensitive to the loss of Isu, with an apparent phenotype being observed 2 days after RNAi induction (Fig. 7B). It is known that this tRNA modification and tRNA import are used equally in both life cycle stages (4), meaning that the resulting growth inhibition in the BS depleted of Isu is most likely a consequence of a perturbation of the Fe-S synthesis pathway rather than tRNA thiolation.

FIG 7.

Cytosolic thiolation in the BS (A) or PS (B) depleted for Isu. RNA isolated from different cell lines was separated on an APM gel followed by Northern blotting. Bands corresponding to thiolated (+S2U) and nonthiolated (−S2U) tRNAs are indicated. H2O2 was used in s as a control of complete oxidation of thiolation, eliminating the mobility shift. The number of days after induction of RNAi by tetracycline is indicated above the lanes. −, noninduced RNAi.

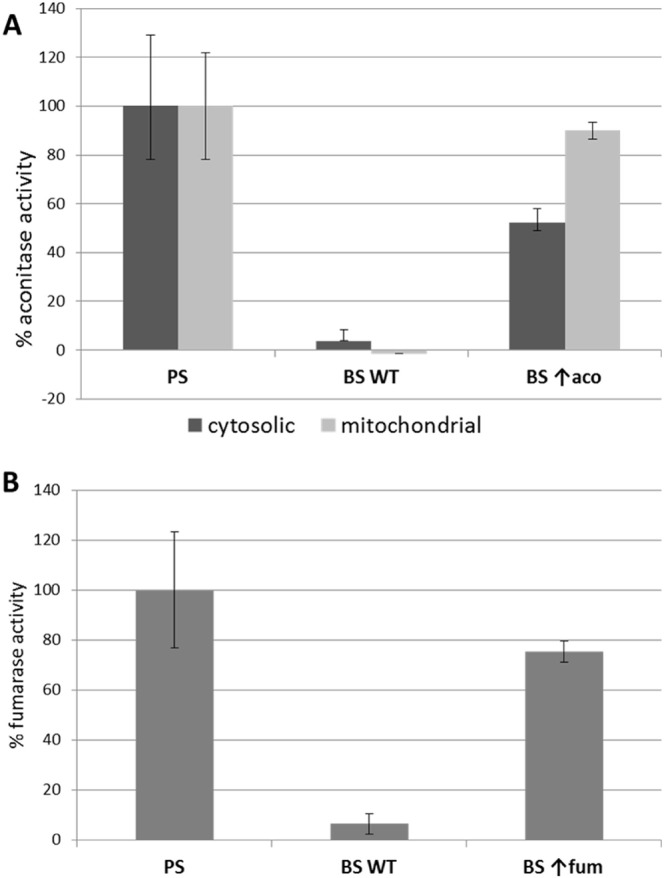

Fe-S cluster assembly is active in the BS.

Finally, we addressed the question of whether the Fe-S assembly pathway is complete and active in the highly reduced BS mitochondrion. A standard approach to scrutinize the availability of the Fe-S clusters is the activity assay for the Fe-S-containing metabolic enzymes aconitase and fumarase. As in other eukaryotes, this method is suitable for the PS (27, 29, 31), but activities of both enzymes are undetectable in the wild-type BS (Fig. 8). To overcome this lack of measurable Fe-S-dependent activities in BS, we created BS cell lines overexpressing either fumarase or aconitase from the pT7-v5 vector. Upon induction with tetracycline, aconitase or the cytosolic form of fumarase were strongly expressed, and the relevant activity was measured in a given cell compartment. In all cases, a strong activity of the overexpressed enzyme, almost reaching the PS level, was obtained (Fig. 8). Separate measurement of the aconitase activity in the cytosol and in the mitochondrion confirmed that the Fe-S clusters are available in both compartments (Fig. 8A). These results confirm that the whole Fe-S synthetic pathway is not only present but indeed active in the BS and that the functional cofactors are available in both the organelle and the cytosol.

FIG 8.

Enzymatic activities of fumarase (A) and aconitase (B) in the PS and BS. Aconitase was measured in cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions; fumarase was measured only in the cytosol. Activities of both Fe-S-dependent enzymes were measured in the wild-type PS and BS flagellates and in the BS with inducible overexpression (↑) of the target proteins. The activity obtained in the PS was set as 100%. Whereas in the wild-type BS, the activities are almost undetectable, levels comparable to those in the PS were reached after overexpression of each enzyme. These results confirm that functional Fe-S clusters are produced even in the BS in both cytosolic and mitochondrial compartments. Values are means and standard deviations from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Combined, the data provide a comprehensive overview of the Fe-S assembly machinery in the BS T. brucei. We focused on the key components, namely, the cysteine desulfurase Nfs, the scaffold protein Isu, and frataxin. Several lines of evidence are consistent with the conclusion that even in the highly suppressed BS mitochondrion, the Fe-S clusters are efficiently built, regardless of the low abundance of their target proteins. Importantly, Nfs and Isu are also present in the nucleolus, while frataxin and both ferredoxins were detected solely in the mitochondrion.

It was of interest to thoroughly examine the subcellular localization of Nfs, Isu, and frataxin proteins in the BS T. brucei. Indeed, Nfs has a dual localization in the mitochondrion and the nucleolus, which is in line with the results obtained with yeast (50, 51). The same dual localization was demonstrated for Isu, but unlike in Nfs, no nuclear localization signal can be detected in the Isu sequence. However, noncanonical and bipartite nuclear localization signals were reported from trypanosomes, which are notoriously difficult to determine (45). Furthermore, in yeast, Nfs is first imported into the mitochondrion and only afterwards transferred to the nucleus (43). The possibility that the whole protein complex is formed in the mitochondrion and only a portion of it is subsequently imported into the nucleolus has to be tested.

As we showed previously, similar to other eukaryotes, in T. brucei, Isd11 is a partner of Nfs, which participates in both Fe-S biosynthesis and tRNA thiolation (27). Mimicking the situation in the mitochondrion, a functional complex of Nfs, Isd11, and Isu may also be formed in the nucleolus in order to effectively abstract sulfur from cysteine and exploit it for a different use than incorporation into the Fe-S clusters. In contrast to mammals (34), trypanosomes do not appear to have frataxin as part of this complex (27), and the protein is strictly detected in the mitochondrion (30; also this work).

To the best of our knowledge, our results provide the first direct evidence of localization of Nfs and Isu in the nucleolus. Both Western blot analysis and transmission electron microscopy showed that the bulk of these proteins are present in the mitochondrion compared to the nucleolus, due to which similar dual localization may have been overlooked in other organisms. In yeast, it was detected by means of an α-complementation assay (43), which is highly sensitive but is hardly applicable in other eukaryotes. In fact, a signal in the nucleolus of T. brucei was undetectable by immunofluorescence, although this may be due to technical reasons, such as the nucleolar localization being masked in the PS by the extensively reticulated mitochondrion. Another reason may be a limited penetration of the specific antibody into the nucleus during the applied staining protocol.

While the function of the mitochondrial Nfs is well known, we know close to nothing about its nucleolar version. It is apparently essential, since mutation of its nuclear localization signal caused a severe change in the growth phenotype in yeast, yet depletion of the nuclear Nfs did not affect maturation of the Fe-S-containing proteins in either the mitochondrion or the nucleus (50, 51). The authors consequently predicted that the nuclear Nfs must be involved in tRNA thiolation. However, this possibility was excluded by showing that Nfs lacking the mitochondrial targeting sequence cannot complement thiolation of either cytosolic or mitochondrial tRNAs (52). In mammalian cells, Nfs was also detected in the cytosol (49) and was shown to be involved in the biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactor (53). We can speculate that such a role may be also attributed to the mitochondrial Nfs in the protist studied, since the molybdenum cofactor synthetase of T. brucei (Tb927.11.11920) has a 0.99 probability of mitochondrial localization, according to Mitoprot (54).

Interestingly, a role in phosphorothioation was recently proposed for bacterial Nfs (55). This DNA modification is unique in directly altering the DNA backbone by exchanging oxygen of phosphate for sulfur (56–58). Phosphorothioation seems to be widespread among diverse bacteria, but data about its presence in eukaryotes are lacking (56). While the DNA of Escherichia coli depleted of IscS (bacterial homolog of Nfs) is broken into a characteristic smear (55), exactly the same experiment performed in wild-type and Nfs-depleted T. brucei did not result in a DNA degradation phenotype (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

It is of interest that almost half of the mitochondrial Nfs is situated in or around the kDNA disk, which is located next to the basal body of the single flagellum. The remaining signal was more or less evenly distributed throughout the lumen of the reticulated organelle, while Isu and both ferredoxins did not show a similarly skewed distribution. This indicates a possible association of a fraction of Nfs with the mitochondrial DNA. The nuclear localization signal is carried by the family of Nfs-related cysteine desulfurases throughout the eukaryotic domain and most likely was present even in their last common ancestor; thus, it must be evolutionarily ancient. Furthermore, we speculate that the function of the nuclear cysteine desulfurase was at least originally the same for all of them.

Although the current paradigm postulates that the Fe-S clusters are in some form essential for every extant eukaryotic cell (24, 25), we wondered whether the mitochondrial branch of the Fe-S assembly pathway produces clusters in the BS organelle, which uniquely lacks respiratory complexes. The only components of the Fe-S biosynthetic pathway studied so far in the BS are the scaffold proteins Isa1 and Isa2, which are dispensable in this stage, unlike in the PS (29). Nevertheless, they were shown to function as scaffolds only for the synthesis of 4Fe-4S clusters (59); thus, their dispensability in the reduced organelle is not surprising.

Since the Fe-S cluster assembly was detected in the mitochondrion-derived mitosomes and hydrogenosomes of Giardia and Trichomonas, respectively (60, 61), it was anticipated that it is also active in the highly functionally downregulated mitochondrion of African trypanosomes. Retention of the Fe-S cluster assembly in the hydrogenosomes is meaningful, since they possess an alternative pathway producing acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) and hydrogen (61), and three enzymes involved in this pathway contain Fe-S clusters. The essentiality of Isu and the measured activities of overexpressed aconitase and fumarase provide evidence that these ancient clusters are made in the repressed organelle of the BS T. brucei as well. Genes encoding components of this ancestral alphaproteobacterial pathway were, in the course of evolution, transferred to the nucleus and retargeted to the organelle via acquired mitochondrial localization signals (62).

In the BS mitochondrion, these cofactors may be incorporated into the nonessential respiratory complexes I and II (12), as well as ferredoxin, glutaredoxin, and lipoate synthase, all of which are expressed at a very low level, however (31, 63). Therefore, we propose that in this life cycle stage, the bulk of cofactors is exported outside the mitochondrion, as in these fast-dividing parasites a high demand for them exists in the catalytic subunits of DNA polymerases (25) and other cytosolic and nuclear proteins.

In conclusion, all the results presented here indicate that the key components of the Fe-S biosynthetic pathway are present in the minimalistic mitochondrion of the BS T. brucei, where they are essential and produce functional cofactors, even though the demand for Fe-S clusters within this organelle is significantly lower than in the PS mitochondrion. In addition we have shown that a significant fraction of Nfs and Isu is present in the nucleolus. Nonetheless, their role in this compartment remains elusive, since all putative functions tested so far, such as Fe-S cluster synthesis (50), tRNA thiolation (52), and phosphorothioation of DNA (this work), provided negative results.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shaojun Long (Washington University, St. Louis) and De-Hua Lai (Sun Yat-Sen University, Guanqzhou, China) for their contribution in the early stages of this project and Hassan Hashimi for helpful discussions. We also thank Paul A. M. Michels (Universidad de los Andes, Mérida/University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom) and André Schneider (University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland) for sharing antibodies.

This work was supported by Czech Grant Agency grant P305/11/2179, Bioglobe grant CZ.1.07/2.3.00/30.0032, AMVIS grant LH12104, EU grant FP7/2007-2013(no. 316304), and the Praemium Academiae award to J.L., who is also a Fellow of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 November 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.00235-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fenn K, Matthews KR. 2007. The cell biology of Trypanosoma brucei differentiation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:539–546. 10.1016/j.mib.2007.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnaufer A, Clark-Walker GD, Steinberg AG, Stuart K. 2005. The F1-ATP synthase complex in bloodstream stage trypanosomes has an unusual and essential function. EMBO J. 24:4029–4040. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnaufer A, Domingo GJ, Stuart K. 2002. Natural and induced dyskinetoplastic trypanosomatids: how to live without mitochondrial DNA. Int. J. Parasitol. 32:1071–1084. 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00020-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cristodero M, Seebeck T, Schneider A. 2010. Mitochondrial translation is essential in bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Microbiol. 78:757–769. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfonzo JD, Lukeš J. 2011. Assembling Fe/S-clusters and modifying tRNAs: ancient co-factors meet ancient adaptors. Trends Parasitol. 27:235–238. 10.1016/j.pt.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halbig K, Nova-Ocampo MDE, Cruz-Reyes J. 2004. Complete cycles of bloodstream trypanosome RNA editing in vitro. RNA 10:914–920. 10.1261/rna.5157704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kafková L, Ammerman ML, Faktorová D, Fisk JC, Zimmer SL, Sobotka R, Read LK, Lukeš J, Hashimi H. 2012. Functional characterization of two paralogs that are novel RNA binding proteins influencing mitochondrial transcripts of Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 18:1846–1861. 10.1261/rna.033852.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider A, Martin JAY, Agabian N. 1994. A nuclear encoded tRNA of Trypanosoma brucei is imported into mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:2317–2322. 10.1128/MCB.14.4.2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider A. 2001. Unique aspects of mitochondrial biogenesis in trypanosomatids. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:1403–1415. 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00296-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lukeš J, Archibald JM, Keeling PJ, Doolittle WF, Gray MW. 2011. How a neutral evolutionary ratchet can build cellular complexity. IUBMB Life 63:528–537. 10.1002/iub.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhuri M, Ott RD, Hill GC. 2006. Trypanosome alternative oxidase: from molecule to function. Trends Parasitol. 22:484–491. 10.1016/j.pt.2006.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surve S, Heestand M, Panicucci B, Schnaufer A, Parsons M. 2012. Enigmatic presence of mitochondrial complex I in Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream forms. Eukaryot. Cell 11:183–193. 10.1128/EC.05282-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timms MW, Deursen Van FJ, Hendriks EF, Matthews KR. 2002. Mitochondrial development during life cycle differentiation of African trypanosomes: evidence for a kinetoplast-dependent differentiation control point. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3747–3759. 10.1091/mbc.E02-05-0266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tasker M, Timms M, Hendriks E, Matthews K. 2001. Cytochrome oxidase subunit VI of Trypanosoma brucei is imported without a cleaved presequence and is developmentally regulated at both RNA and protein levels. Mol. Microbiol. 39:272–285. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02252.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannaert V, Bringaud F, Opperdoes FR, Michels PAM. 2003. Evolution of energy metabolism and its compartmentation in Kinetoplastida. Kinetoplastid Biol. Dis. 30:1–30. 10.1186/1475-9292-2-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephens JL, Lee SH, Paul KS, Englund PT. 2007. Mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 282:4427–4436. 10.1074/jbc.M609037200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clayton AM, Guler JL, Povelones ML, Gluenz E, Gull K, Smith TK, Jensen RE, Englund PT. 2011. Depletion of mitochondrial acyl carrier protein in bloodstream-form Trypanosoma brucei causes a kinetoplast segregation defect. Eukaryot. Cell 10:286–292. 10.1128/EC.00290-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong Z, Ridgley EL, Enis D, Olness F, Ruben L. 1997. Selective transfer of calcium from an acidic compartment to the mitochondrion of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 272:31022–31028. 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vercesi AE, Docampo R, Moreno SN. 1992. Energization-dependent Ca2+ accumulation in Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream and procyclic trypomastigotes mitochondria. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 56:251–257. 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90174-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimi H, McDonald L, Stříbrná E, Lukeš J. 2013. Trypanosome Letm1 protein is essential for mitochondrial potassium homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 288:26914–26925. 10.1074/jbc.M113.495119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hellemond Van JJ, Bakker BM, Tielens AGM. 2005. Energy metabolism and its compartmentation in Trypanosoma brucei. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 50:199–226. 10.1016/S0065-2911(05)50005-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Docampo R, Lukeš J. 2012. Trypanosomes and the solution to a 50-year mitochondrial calcium mystery. Trends Parasitol. 28:31–37. 10.1016/j.pt.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnaufer A, Panigrahi AK, Panicucci B, Igo RP, Salavati R, Stuart K. 2001. An RNA ligase essential for RNA editing and survival of the bloodstream form of Trypanosoma brucei. Science 291:2159–2162. 10.1126/science.1058655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lill R. 2009. Function and biogenesis of iron-sulphur proteins. Nature 460:831–838. 10.1038/nature08301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierik AJ, Netz DJA, Lill R. 2009. Analysis of iron-sulfur protein maturation in eukaryotes. Nat. Protoc. 4:753–766. 10.1038/nprot.2009.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouault TA. 2012. Biogenesis of iron-sulfur clusters in mammalian cells: new insights and relevance to human disease. Dis. Model Mech. 5:155–164. 10.1242/dmm.009019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paris Z, Changmai P, Rubio MAT, Zíková A, Stuart KD, Alfonzo JD, Lukeš J. 2010. The Fe/S cluster assembly protein Isd11 is essential for tRNA thiolation in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 285:22394–22402. 10.1074/jbc.M109.083774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smíd O, Horáková E, Vilímová V, Hrdý I, Cammack R, Horváth A, Lukeš J, Tachezy J. 2006. Knock-downs of iron-sulfur cluster assembly proteins IscS and IscU down-regulate the active mitochondrion of procyclic Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 281:28679–28686. 10.1074/jbc.M513781200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long S, Changmai P, Tsaousis AD, Skalický T, Verner Z, Wen Y-Z, Roger AJ, Lukeš J. 2011. Stage-specific requirement for Isa1 and Isa2 proteins in the mitochondrion of Trypanosoma brucei and heterologous rescue by human and Blastocystis orthologues. Mol. Microbiol. 81:1403–1418. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Long S, Jirků M, Ayala FJ, Lukeš J. 2008. Mitochondrial localization of human frataxin is necessary but processing is not for rescuing frataxin deficiency in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:13468–13473. 10.1073/pnas.0806762105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Changmai P, Horáková E, Long S, Cernotíková-Stříbrná E, McDonald LM, Bontempi EJ, Lukeš J. 2013. Both human ferredoxins equally efficiently rescue ferredoxin deficiency in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Microbiol. 89:135–151. 10.1111/mmi.12264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon T, Cowan JA. 2003. Iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis. Characterization of frataxin as an iron donor for assembly of [2Fe-2S] clusters in ISU-type proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:6078–6084. 10.1021/ja027967i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gentry LE, Thacker MA, Doughty R, Timkovich R, Busenlehner LS. 2013. His86 from the N-terminus of frataxin coordinates iron and is required for Fe-S cluster synthesis. Biochemistry 52:6085–6096. 10.1021/bi400443n [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmucker S, Martelli A, Colin F, Page A, Wattenhofer-Donzé M, Reutenauer L, Puccio H. 2011. Mammalian frataxin: an essential function for cellular viability through an interaction with a preformed ISCU/NFS1/ISD11 iron-sulfur assembly complex. PLoS One 6:e16199. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long S, Jirků M, Mach J, Ginger ML, Sutak R, Richardson D, Tachezy J, Lukeš J. 2008. Ancestral roles of eukaryotic frataxin: mitochondrial frataxin function and heterologous expression of hydrogenosomal Trichomonas homologues in trypanosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 69:94–109. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Comini MA, Rettig J, Dirdjaja N, Hanschmann E-M, Berndt C, Krauth-Siegel RL. 2008. Monothiol glutaredoxin-1 is an essential iron-sulfur protein in the mitochondrion of African trypanosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 283:27785–27798. 10.1074/jbc.M802010200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pusnik M, Charrière F, Mäser P, Waller RF, Dagley MJ, Lithgow T, Schneider A. 2009. The single mitochondrial porin of Trypanosoma brucei is the main metabolite transporter in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26:671–680. 10.1093/molbev/msn288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basu S, Leonard JC, Desai N, Mavridou DA, Tang KH, Goddard AD, Ginger ML, Lukeš J, Allen JW. 2013. Divergence of Erv1-associated mitochondrial import and export pathways in trypanosomes and anaerobic protists. Eukaryot. Cell 12:343–355. 10.1128/EC.00304-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zíková A, Panigrahi AK, Uboldi AD, Dalley R, Handman E, Stuart K. 2008. Structural and functional association of Trypanosoma brucei MIX protein with cytochrome c oxidase complex. Eukaryot. Cell 7:1994–2003. 10.1128/EC.00204-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foldynová-Trantírková S, Paris Z, Sturm NR, Campbell DA, Lukeš J. 2005. The Trypanosoma brucei La protein is a candidate poly(U) shield that impacts spliced leader RNA maturation and tRNA intron removal. Int. J. Parasitol. 35:359–366. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayhew TM, Lucocq JM, Griffiths G. 2002. Relative labelling index: a novel stereological approach to test for non-random immunogold labelling of organelles and membranes on transmission electron microscopy thin sections. J. Microsc. 205:153–164. 10.1046/j.0022-2720.2001.00977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vondrušková E, van den Burg J, Zíková A, Ernst NL, Stuart K, Benne R, Lukeš J. 2005. RNA interference analyses suggest a transcript-specific regulatory role for mitochondrial RNA-binding proteins MRP1 and MRP2 in RNA editing and other RNA processing in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 280:2429–2438. 10.1074/jbc.M405933200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naamati A, Regev-Rudzki N, Galperin S, Lill R, Pines O. 2009. Dual targeting of Nfs1 and discovery of its novel processing enzyme, Icp55. J. Biol. Chem. 284:30200–30208. 10.1074/jbc.M109.034694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westergaard GG, Bercovich N, Reinert MD, Vazquez MP. 2010. Analysis of a nuclear localization signal in the p14 splicing factor in Trypanosoma cruzi. Int. J. Parasitol. 40:1029–1035. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marchetti MA, Tschudi C, Kwon H, Wolin SL, Ullu E. 2000. Import of proteins into the trypanosome nucleus and their distribution at karyokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 113:899–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boucher N, Dacheux D, Giroud C, Baltz T. 2007. An essential cell cycle-regulated nucleolar protein relocates to the mitotic spindle where it is involved in mitotic progression in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 282:13780–13790. 10.1074/jbc.M700780200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hellman K, Prohaska K, Williams N. 2007. Trypanosoma brucei RNA binding proteins p34 and p37 mediate NOPP44/46 cellular localization via the exportin 1 nuclear export pathway. Eukaryot. Cell 6:2206–2213. 10.1128/EC.00176-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cámara MDLM, Bouvier LA, Canepa GE, Miranda MR, Pereira CA. 2013. Molecular and functional characterization of a Trypanosoma cruzi nuclear adenylate kinase isoform. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7:e2044. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li K, Tong W-H, Hughes RM, Rouault TA. 2006. Roles of the mammalian cytosolic cysteine desulfurase, ISCS, and scaffold protein, ISCU, in iron-sulfur cluster assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 281:12344–12351. 10.1074/jbc.M600582200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakai Y, Nakai M, Hayashi H, Kagamiyama H. 2001. Nuclear localization of yeast Nfs1p is required for cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8314–8320. 10.1074/jbc.M007878200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mühlenhoff U, Balk J, Richhardt N, Kaiser JT, Sipos K, Kispal G, Lill R. 2004. Functional characterization of the eukaryotic cysteine desulfurase Nfs1p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279:36906–36915. 10.1074/jbc.M406516200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakai Y, Nakai M, Lill R, Suzuki T, Hayashi H. 2007. Thio modification of yeast cytosolic tRNA is an iron-sulfur protein-dependent pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:2841–2847. 10.1128/MCB.01321-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marelja Z, Stöcklein W, Nimtz M, Leimkühler S. 2008. A novel role for human Nfs1 in the cytoplasm: Nfs1 acts as a sulfur donor for MOCS3, a protein involved in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 283:25178–25185. 10.1074/jbc.M804064200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Claros MG, Vincens P. 1996. Computational method to predict mitochondrially imported proteins and their targeting sequences. Eur. J. Biochem. 241:779–786. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00779.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.An X, Xiong W, Yang Y, Li F, Zhou X, Wang Z, Deng Z, Liang J. 2012. A novel target of IscS in Escherichia coli: participating in DNA phosphorothioation. PLoS One 7:e51265. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang L, Chen S, Vergin KL, Giovannoni SJ, Chan SW, DeMott MS, Taghizadeh K, Cordero OX, Cutler M, Timberlake S, Alm EJ, Polz MF, Pinhassi J, Deng Z, Dedon PC. 2011. DNA phosphorothioation is widespread and quantized in bacterial genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2963–2968. 10.1073/pnas.1017261108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eckstein F. 2007. Phosphorothioation of DNA in bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3:689–690. 10.1038/nchembio1107-689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L, Chen S, Xu T, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok JS, Zhou X, You D, Deng Z, Dedon PC. 2007. Phosphorothioation of DNA in bacteria by dnd genes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3:709–710. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mühlenhoff U, Richter N, Pines O, Pierik AJ, Lill R. 2011. Specialized function of yeast Isa1 and Isa2 proteins in the maturation of mitochondrial [4Fe-4S] proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286:41205–41216. 10.1074/jbc.M111.296152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tovar J, León-Avila G, Sánchez LB, Sutak R, Tachezy J, van der Giezen M, Hernández M, Müller M, Lucocq JM. 2003. Mitochondrial remnant organelles of Giardia function in iron-sulphur protein maturation. Nature 426:172–176. 10.1038/nature01945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sutak R, Doležal P, Fiumera HL, Hrdý I, Dancis A, Delgadillo-Correa M, Johnson PJ, Müller M, Tachezy J. 2004. Mitochondrial-type assembly of FeS centers in the hydrogenosomes of the amitochondriate eukaryote Trichomonas vaginalis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:10368–10373. 10.1073/pnas.0401319101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tachezy J, Sánchez LB, Müller M. 2001. Mitochondrial type iron-sulfur cluster assembly in the amitochondriate eukaryotes Trichomonas vaginalis and Giardia intestinalis, as indicated by the phylogeny of IscS. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18:1919–1928. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nilsson D, Gunasekera K, Mani J, Osteras M, Farinelli L, Baerlocher L, Roditi I, Ochsenreiter T. 2010. Spliced leader trapping reveals widespread alternative splicing patterns in the highly dynamic transcriptome of Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001037. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.