Abstract

Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354 is a surrogate microorganism used in place of pathogens for validation of thermal processing technologies and systems. We evaluated the safety of strain NRRL B-2354 based on its genomic and functional characteristics. The genome of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 was sequenced and found to comprise a 2,635,572-bp chromosome and a 214,319-bp megaplasmid. A total of 2,639 coding sequences were identified, including 45 genes unique to this strain. Hierarchical clustering of the NRRL B-2354 genome with 126 other E. faecium genomes as well as pbp5 locus comparisons and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) showed that the genotype of this strain is most similar to commensal, or community-associated, strains of this species. E. faecium NRRL B-2354 lacks antibiotic resistance genes, and both NRRL B-2354 and its clonal relative ATCC 8459 are sensitive to clinically relevant antibiotics. This organism also lacks, or contains nonfunctional copies of, enterococcal virulence genes including acm, cyl, the ebp operon, esp, gelE, hyl, IS16, and associated phenotypes. It does contain scm, sagA, efaA, and pilA, although either these genes were not expressed or their roles in enterococcal virulence are not well understood. Compared with the clinical strains TX0082 and 1,231,502, E. faecium NRRL B-2354 was more resistant to acidic conditions (pH 2.4) and high temperatures (60°C) and was able to grow in 8% ethanol. These findings support the continued use of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 in thermal process validation of food products.

INTRODUCTION

Enterococcus faecium is a commensal organism of mammalian digestive tracts and is important for the production of fermented food products, including cheese and sausage (1). Certain strains of E. faecium were shown to have beneficial, or probiotic, effects on animal (2–4) and human (5–7) health. However, strains of E. faecium have also been associated with nosocomial infections (8). Over the past 30 years, the number of enterococcal infections has increased, with a growing number of illnesses specifically attributed to E. faecium (9). E. faecium infections are of particular concern because of the high incidence of antibiotic resistance among many hospital-associated strains. For this reason, E. faecium was identified as an important problem organism requiring new treatment methods (10).

Recent studies have shown that there is a significant evolutionary distance between hospital- and community-associated strains of E. faecium. Differences between these strains include phenotypic (11), gene-specific (12, 13), and whole-genome and proteome level (14–19) distinctions. There are currently over 200 publicly available E. faecium draft genomes. The best-characterized genomes are for strain TX16 (also referred to as DO), isolated from an individual with endocarditis (20), and strain Aus0004, isolated from the bloodstream of a hospitalized patient (21). Several draft genomes of community-associated strains are also currently available in public databases, but none have been characterized in depth.

The taxonomic classification of E. faecium strain NRRL B-2354 has gone through numerous revisions. It was originally isolated from dairy utensils in 1927 by G. J. Hucker (22) and in 1960 was deposited in the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Research Service NRRL culture collection as NRRL B-2354. In 1979, the strain was placed within the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) as Micrococcus freudenreichii ATCC 8459. However, it was later found to lack many of the characteristics typical of M. freudenreichii (23) and was reclassified to an undetermined species of Pediococcus. Recently, 16S rRNA gene sequencing and biochemical assays led to the conclusion that strain NRRL B-2354 is most similar to members of the E. faecium species (24), a finding that led to reclassification of the strain assignment at NRRL and ATCC.

The thermal tolerance of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 on almonds is similar to that of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis phage type 30. This strain is recommended and widely used as a surrogate for Salmonella in the validation of commercial thermal processes that are used for almonds (25–28). E. faecium NRRL B-2354 is also considered to be a suitable surrogate for food-borne pathogens in thermal processes used for dairy products (29), juice (30), and meat (24). Surrogate organisms are inoculated into or onto food products that are subsequently sent through food processing equipment located in commercial food processing facilities. Because of the risks associated with introducing a pathogen into a food processing facility, it is preferred to use a nonpathogenic surrogate organism that has been adequately characterized. Despite the long history of use of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 as a surrogate, concern over E. faecium in clinical settings supports the need to further evaluate the characteristics of this particular strain. Therefore, we examined the genome of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 for the presence of virulence factors, evaluated the expression of those genes and environmentally relevant phenotypes, and quantified resistance to several clinically important antibiotics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

E. faecium NRRL B-2354 was obtained from the USDA Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection (Peoria, IL; receiving date, 22 July 2011; http://nrrl.ncaur.usda.gov). E. faecium ATCC 8459 (receiving date, 26 July 2011), Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 (receiving date, 26 July 2011), and Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). E. faecium TX0082 was provided by Barbara Murray (University of Texas Medical School, Houston). E. faecium 1,231,502 was provided Michael Gilmore (Harvard University, Boston, MA). Enterococcus strains were routinely cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) agar or broth (dehydrated medium; Difco, Becton, Dickinson [BD], Franklin Lakes, NJ), incubated overnight at 37°C.

DNA sequencing, assembly, and annotation.

One colony of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 strain was inoculated into 15 ml of BHI broth and incubated at 37°C under static conditions for 8 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 80 g NaCl, 2 g KCl, 26.8 g Na2HPO4 · 7H2O, and 2.4 g KH2PO4 in 800 ml H2O, pH 7.3). Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

A 500-bp insert library was prepared for 100-bp, paired-end sequencing in the Illumina HiSeq 2000 as previously reported (31). A total of 4,044 Mbp of 100-bp paired-end reads were obtained and were quality filtered at a quality score of ≥20 at each nucleotide position. After quality filtering, 656 Mbp of 80-bp or longer Illumina reads was obtained. The filtered reads (≥80 bp) were assembled into contigs by using the Ray 1.7 sequence assembler (32) with a 31-bp k-mer. The filtered Illumina reads were assembled into 49 contigs (>100 bp; total length, 2,841,503 bp; average length, 57,989 bp; maximum length, 198,831 bp; N50 length, 138,902 bp; GC content, 37.84%). The genomic DNA was also sequenced using the PacBio RS sequencer with C2 chemistry (1 × 90 min and 2 × 45 min) (21). PacBio RS sequencing produced a total of 292 Mbp with an average length of 2,328 bp (maximum length, 14,914 bp; N50 length, 3,385 bp) after removing adaptor sequences. PacBio reads 6 kbp or longer were used to close gaps between the contigs. Errors found in PacBio reads were corrected by using the Illumina reads (33). All DNA sequencing was performed at the UC Davis Genome Center (http://www.genomecenter.ucdavis.edu).

The gap-closed and error-corrected genome sequences were annotated for protein coding sequences (CDS), rRNA genes, and tRNA genes by manual annotation and by Rapid Annotation Using Subsystem Technology (RAST) (34), RNAmmer 1.2 Server (35), and tRNAscan-SE 1.21 (36) with default options for bacteria. The genome was also screened for the presence of antibiotic resistance (AR) genes found in the Antibiotic Resistance Database (ARDB) (37).

Hierarchical clustering and phylogenetic analysis.

A total of 126 genome sequences and annotations for 125 E. faecium strains, including two versions of the E. faecium DO (TX16) genome were obtained from public databases in April 2013 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The genomes were screened for 7,017 orthologs of protein coding sequences identified in a previous report (19). For hierarchical clustering of E. faecium strains, gene ortholog distances between two strains were calculated according to the Euclidean distance method. Bootstrapping was performed using Pvclust with a 10,000 resampling option (38).

Phylogenetic comparisons of PBP5 protein sequences (39) and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for seven housekeeping genes (adk, atpA, ddl, gdh, gyd, pstS, and purK) (40) were performed for all E. faecium genomes using MEGA 5 (41).

Circular genome alignment.

E. faecium genome sequences were fragmented into 500-bp sequences and then aligned to the E. faecium NRRL B-2354 genome as a reference using GASSST (42). The alignment was visualized in concentric circles using perl scripts. Protein coding sequences, tRNA, rRNA, AR genes (37), virulence factor (VF) genes (8), and mobile elements (ME) were designated as previously described (19). ME elements included phage genes or transposon, transposase, integrase, and insertion sequences (IS) based on the genome annotations. Genes with GC contents that were high (GC% ≥ mean + 1.5 × standard deviation [SD]) or low (GC% ≤ mean − 1.5 × SD) were also identified.

Detection of virulence-associated genes.

Certain Enterococcus VF genes were examined for their presence in the NRRL B-2354 genome by using NCBI BLAST+ (43). The presence of esp, gelE, and hyl was also examined by PCR according to previously described protocols (44, 45) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Positive controls used for PCR were E. faecalis ATCC 29212 (gelE) and E. faecium 1,231,502 (esp and hyl).

Electron microscopy.

Negative staining was accomplished with standard techniques utilizing 1% ammonium molybdate (46). Transmission electron microscopy was performed with a Philips CM120 Biotwin lens (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR), and the camera used was a Gatan MegaScan model 794/20 digital camera (2K × 2K; Pleasanton, CA). Microscopy and staining were performed at The University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Electron Microscopy Lab.

Production of gelatinase and hemolysin.

The ability to hydrolyze gelatin was determined by examining for zones of turbidity around colonies after growth overnight at 37°C on Todd-Hewitt agar supplemented with 3% (wt/vol) gelatin (47). Hemolysin was measured by examining for zones of clearing around colonies after growth overnight at 37°C on tryptic soy agar (TSA) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) defibrinated horse blood (47).

Adherence to collagen type I.

Adhesion to collagen was evaluated using a previously described method (48), with several modifications. Rat tail collagen (type I) in 0.02 M acetic acid (BD) at a concentration of 15 μg per well was used. E. faecium cells from overnight cultures grown in BHI broth were collected by centrifugation at 805 × g, suspended in PBS to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0, and added to the wells. Adhesion was calculated according to relative absorbance in a microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek, Winooski, VT) as follows: OD595(collagen+BSA+bacteria) − OD595(BSA+bacteria).

Adherence to fibrinogen and fibronectin.

The ability to adhere to fibrinogen and fibronectin was examined using previously described methods (49), except that 200 μl human fibrinogen (Calbiochem, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), 15 μg per well, or 200 μl fibronectin (Calbiochem) in 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), 15 μg per well, was used.

Biofilm formation on polystyrene.

The ability of cells to adhere to polystyrene plates was evaluated using a previously described method (50) with several modifications. Cells were grown overnight in BHI broth at 37°C, and 200 μl of a 1:20 dilution of the cultures in BHI broth was added to a sterile 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate (BD). After incubating for 24 h at 37°C, wells were washed three times with PBS, dried in an inverted position for 15 min, and stained with 1% (wt/vol) crystal violet for 15 min. The wells were rinsed again with PBS, and the crystal violet was solubilized in 200 μl of an ethanol and acetone solution (80:20, vol/vol). The OD595 was determined using a microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Antibiotic resistance was determined at the University of California, Davis Medical Center Clinical Laboratory, Sacramento, CA (http://www.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/pathology/services/), using the BD Phoenix 100 Automated Microbiology system (BD).

Survival at low pH, at high temperature, or in the presence of ethanol.

For acid and thermal stress tolerance tests, E. faecium strains were first grown in BHI overnight at 37°C and washed twice in physiological saline (0.85% [wt/vol] NaCl, pH 7). To measure survival at low pH, washed cells were suspended in physiological saline with an adjusted pH of 2.4 (acidified with 5 M HCl). Suspensions were sampled at 10-min intervals for 60 min, and serial dilutions were prepared in physiological saline for plating onto BHI agar. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight for CFU enumeration. Thermal tolerance was determined by dispensing 50 μl of the E. faecium cells in physiological saline (pH 7) into 200 μl microcentrifuge tubes and incubating in a C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Foster City, CA) at either 50°C or 60°C. Cell survival was determined every 10 min for 60 min by CFU enumeration using serial dilutions of separate 50-μl aliquots cooled to 21 to 23°C. Ethanol tolerance was determined by incubation of approximately 107 E. faecium cells at 37°C in BHI broth adjusted to contain either 12% (vol/vol) additional water or 8% or 12% (vol/vol) ethanol. Growth was measured at an OD600 every 15 min over 24 h in a microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The genome sequence and gene annotation information have been deposited at GenBank under the accession numbers CP004063 (chromosome) and CP004064 (plasmid pNB2354_1).

RESULTS

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation of E. faecium NRRL B-2354.

The genome of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 was sequenced, assembled, and annotated to yield one chromosome (2,635,572 bp) and one plasmid (214,319 bp, designated pNB2354_1) (see Fig. S1 and Table S3 in the supplemental material). The GC content of the NRRL B-2354 chromosome (38.03%) is similar to that of other E. faecium strains, including TX16 (also known as DO) (38.15%) (20) and Aus0004 (38.36%) (21). The GC content of the plasmid is lower (35.98%) than that of the chromosome but similar to that of the megaplasmids of other E. faecium strains (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). A total of 2,639 CDS, 18 rRNA (5S, 16S, and 23S), and 49 tRNA genes were predicted in the assembled annotated genome (see Table S3). The genome of the clonal deposit of this strain at the ATCC, strain ATCC 8459, was also sequenced and found to share over 99% sequence identity with the strain NRRL B-2354 (data not shown).

Hierarchical clustering and phylogenetic analysis.

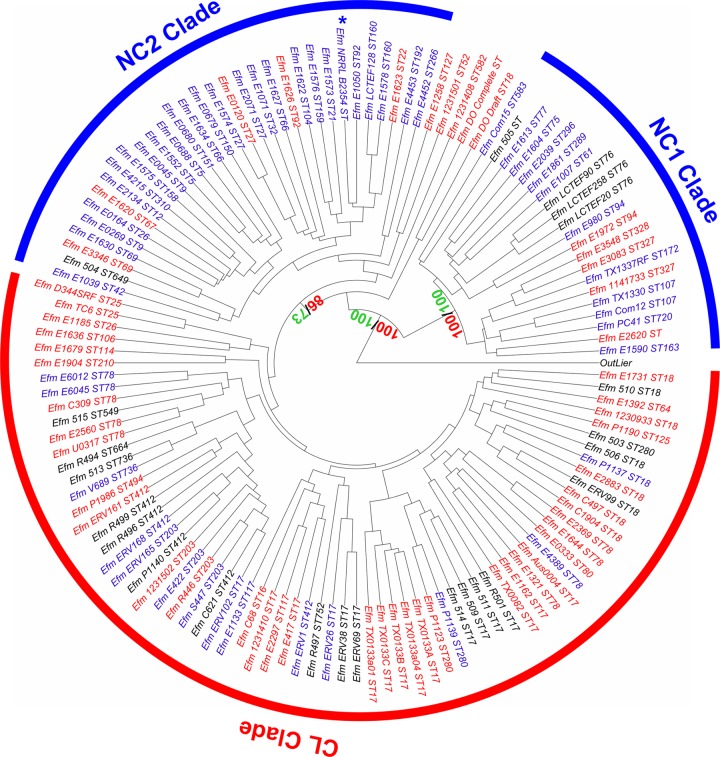

Hierarchical clustering was performed using strain NRRL B-2354 and 126 other E. faecium genome sequences according to the presence/absence of orthologous genes as previously described (19). The genome of strain NRRL B-2354 clustered with other nonclinical (NC), or community, E. faecium isolates in a clade containing few clinical (CL) strains (Fig. 1). Specifically, the NRRL B-2354 genome clustered with other community E. faecium strains in the NC2 clade. This newly described clade is significantly enriched in nonclinical strains (P = 0.036, Fisher's exact test) among which 26 of the 32 strains available for comparison had nonclinical, or community, origins. The genome of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 was most similar to that of strain E1050, a fecal isolate from a healthy volunteer.

FIG 1.

Hierarchical clustering of 127 E. faecium genomes. Genome comparisons were based on the presence/absence of 7,017 orthologs found in the E. faecium pangenome. Nonclinical strains are labeled in blue, clinical strains in red, and strains with unidentified origins in black. An artificial outlier was included. Strain NRRL B-2354 is indicated by an asterisk. Red and green values in certain nodes indicate approximately unbiased and biased probabilities for the bootstrapping, respectively.

Gene-targeted comparisons using the pbp5 gene and MLST were also performed to further evaluate the relationships between E. faecium NRRL B-2354 and other E. faecium strains. The pbp5-R genotype is associated with ampicillin resistance, and PBP5 amino acid sequences separated E. faecium strains into two different clades (39, 51). A phylogenetic tree of PBP5 protein sequences from E. faecium strains showed that the PBP5 amino acid sequence of strain NRRL B-2354 clustered together with many community-associated (nonclinical) strains of strains belonging to the NC2 clade (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Notably, these strains along with NRRL B-2354 exhibit a pbp5-R genotype (51).

In contrast, MLST analysis did not show clear NC and CL strain separation (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Examination of the E. faecium NRRL B-2354 genome revealed that this strain belongs in sequence type ST32 according to six of the seven housekeeping genes used for sequence typing (atpA, ddl, gdh, gyd, pstS, and purK). This MLST pattern is highly associated with NC E. faecium strains, unlike other sequence types (ST) (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Sequence comparisons of adk, the remaining gene commonly used for enterococcal MLST, identified a single-nucleotide change in this gene in NRRL B-2354 compared to the other members of ST32. Because this difference might represent a novel MLST group, strain NRRL B-2354 was assigned a novel sequence type (ST860) in the E. faecium MLST database (http://efaecium.mlst.net/) (40) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Unique genes in the NRRL B-2354 genome.

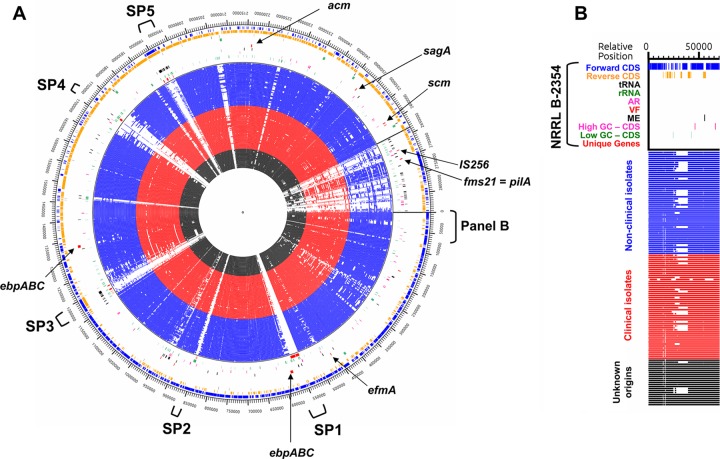

Genome comparisons identified 45 unique genes in NRRL B-2354 not present in the other 125 E. faecium strains examined. These genes are colocalized in the genome in five locations (designated SP1 to SP5) (Fig. 2). Many of the genes specific to strain NRRL B-2354 are ME or colocalized to ME genes (Fig. 2; see Table S5 in the supplemental material). A total of 25 of the 45 genes have functional assignments and include a putative glycosyltransferase, an amidohydrolase domain protein, a transcriptional antiterminator, a DEAD/DEAH box helicase-like protein, and DNA repair protein RadC (Fig. 2; see Table S5 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

Alignment of 127 E. faecium genomes. (A) Circular alignment of E. faecium genomes. The outside of the circle is the NRRL B-2354 reference genome to which the other genomes are aligned. Genes identified as potential VF in NRRL B-2354 are indicated. Loci unique to NRRL B-2354 are also indicated (SP1 to SP5). (B) Key to circular alignment map. Gene types and strain origins are depicted in the same order (outwards to inwards) in the circular map. AR, antibiotic resistance genes; VF, virulence factors; ME, mobile genetic elements.

Antibiotic resistance and related genes in NRRL B-2354.

Antibiotic resistance genes were not found in the NRRL B-2354 genome (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Based on MICs, E. faecium NRRL B-2354 is sensitive to vancomycin, streptomycin, gentamicin, and ampicillin (Table 1), antibiotics commonly used separately or in tandem to treat enterococcal infections (52). The strain exhibited intermediate sensitivity to erythromycin and was sensitive to the cephalosporins cefoxitin and cefazolin, despite cephalosporin resistance being intrinsic to most enterococci (53) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Antibiotic resistance of E. faecium NRRL B-2354a

| Class and antibiotic | MIC (mg/liter) | Sensitivity | No. of screened AR gene types from ARDBc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | |||

| Gentamicin | Sensitiveb | Sensitive | 737 |

| Streptomycin | Sensitiveb | Sensitive | 869 |

| Cephalosporins | |||

| Cefazolin | <2 | Sensitive | 1,393 |

| Cefoxitin | 8 | Sensitive | 844 |

| Glycopeptides | |||

| Vancomycin | <0.5 | Sensitive | 300 |

| Macrolides | |||

| Erythromycin | 2 | Intermediate | 1,092 |

| Penicillins | |||

| Ampicillind | <0.125 | Sensitive | 1,896 |

| Penicillin | <1 | Sensitive | 1,896 |

| Quinolones | |||

| Levofloxacin | 2 | Sensitive | 273 |

| Tetracyclines | |||

| Minocycline | <1 | Sensitive | 597 |

| Tetracycline | <0.5 | Sensitive | 597 |

The same results were found for E. faecium ATCC 8459.

Numerical MICs were not determined.

No AR genes were detected in our study; ARDB data are from reference 37.

Certain pbp5 genotypes are associated with ampicillin resistance in E. faecium, but they were not considered here because of the variation in ampicillin resistance and sensitivity phenotypes among strains containing this gene.

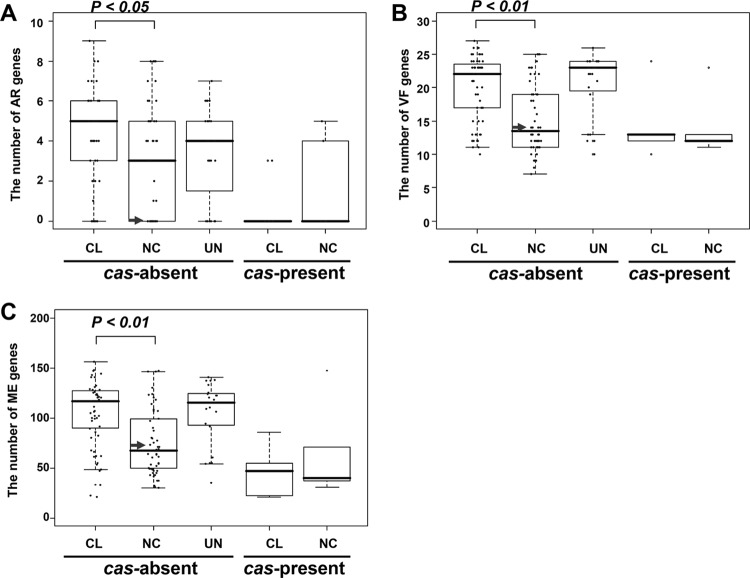

Presence of cas and the number of AR, VF, and ME genes.

The genome of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 lacks cas genes encoding clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-associated proteins involved in bacterial immunity against foreign DNA (54). For at least certain E. faecium strains, the number of cas genes is negatively correlated with the number of AR genes (55). To examine whether this trait was common to E. faecium from both NC and CL origins, the numbers of AR genes were compared among strains lacking CRISPR-cas systems. Notably, cas-negative NC strains contained significantly lower numbers of AR genes than did strains with a CL background (Fig. 3). The numbers of VF and ME genes are also significantly lower in NC than in CL isolates (Fig. 3). Such observations were not statistically examined for cas-positive E. faecium strains due to the low number of those strains for which genome sequences were available.

FIG 3.

Numbers of AR, VF, and ME genes in strains with or without cas genes. Three types of genes, AR (A), VF (B), and ME (C), that have important roles in virulence of E. faecium were counted and compared statistically between CL and NC E. faecium strains (Student's t test). Strains with unidentified origins (UN) were also shown for reference. The arrow indicates the value of NRRL B-2354 in each panel.

Virulence factors.

The E. faecium NRRL B-2354 genome lacks several genes encoding VF that are associated with this species (Table 2). Specifically, IS16, a common marker of hospital-associated strains (56), is absent from strain NRRL B-2354, as are genes coding for gelatinase (gelE) (57), hyaluronidase (hyl) (58), cytolysin (cyl) (59), and a virulence and biofilm formation protein (esp) (60). These VF are commonly found in hospital-associated strains of E. faecium (47). The in silico findings for several of these genes were confirmed by PCR (data not shown). The absence of gelE was also confirmed by the inability of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 to hydrolyze gelatin during growth on laboratory culture medium (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Although another putative hemolysin (AGE29035) was annotated in the genome of E. faecium NRRL B-2354, hemolytic activity was not detected for E. faecium NRRL B-2354 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 2.

Presence of virulence factors in E. faecium NRRL B-2354

| Genea | Function | Length of reference gene (bp) | % Coverage | Nucleotide identity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acm | Adhesion to collagen and other extracellular proteins | 2,166 | 100 | 99 | 64 |

| cyl | Cytolysin, hemolysis | 7,500 | NDb | ND | 60 |

| ebpR | Regulatory gene for enterococcus biofilm and pilus (ebp) operon | 1,392 | ND | ND | 65 |

| ebpA | Pilin subunit | 3,390 | 80 | 99 | 65 |

| ebpB | Pilin subunit | 1,422 | 100 | 99 | 65 |

| ebpC | Pilin subunit | 1,878 | 100 | 99 | 65 |

| efaAfm | Adhesion protein, plays role in endocarditis | 951 | 100 | 100 | 68 |

| esp | Enterococcal surface protein | 2,315 | ND | ND | 61 |

| gelE | Gelatinase | 6,088 | ND | ND | 58 |

| hyl | Hyaluronidase | 1,662 | ND | ND | 59 |

| IS16 | Mobile insertion sequence | 1,188 | ND | ND | 57 |

| pilA | Major pilin subunit | 1,977 | 100 | 99 | 67 |

| pilE | Secreted surface protein | 756 | 100 | 100 | 67 |

| pilF | Minor pilin subunit | 2,091 | 100 | 99 | 67 |

| sagA | Adhesion protein | 1,575 | 100 | 100 | 70 |

| scm | Surface protein, adhesion to extracellular proteins | 1,983 | 100 | 100 | 62 |

The E. faecium NRRL B-2354 genome was compared to the E. faecium TX16 (DO) genome, except for the following: E. faecium Aus0004 (esp), E. faecalis V583 (cyl, gelE), E. faecium U37 (IS16), and E. faecium E1165 (pilA, pilE, pilF).

ND, not detected.

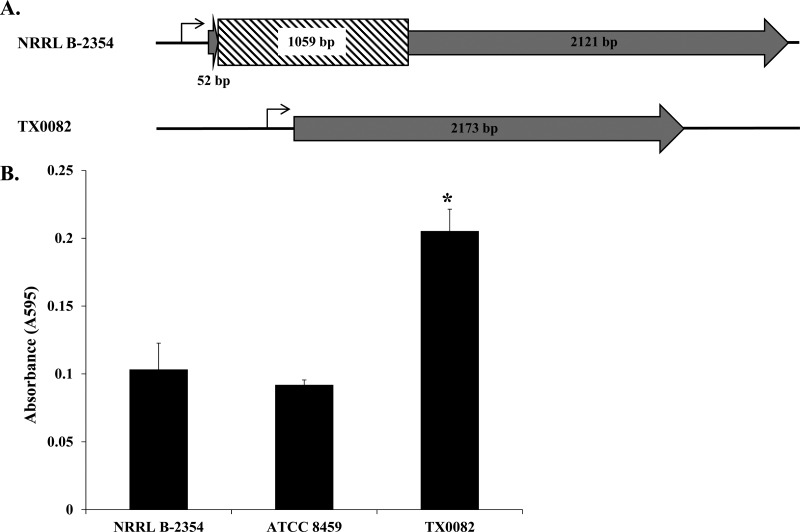

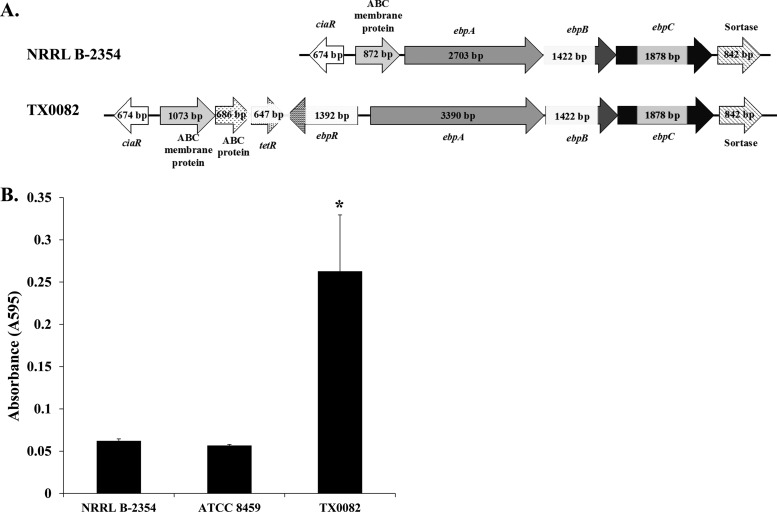

The scm gene encoding a collagen I and IV adhesion (61) and the acm gene encoding a collagen I adhesion associated with endocarditis (62) were found in strain NRRL B-2354 (Table 2). Although scm appeared to be intact, acm contained a 1,059-bp insertion 52 bp into the coding region of the gene (Fig. 4A; see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). This insertion is an integrase that shares 100% nucleotide identity with an integrase from E. faecium Aus0004 (21). The integrase contains many stop codons in the reading frame of acm (Fig. 4A), indicating that acm is not expressed. Strain NRRL B-2354 and its clonal relative ATCC 8459 also adhered to collagen in significantly smaller amounts than E. faecium TX0082 (ST17) (Fig. 4B). E. faecium TX0082 (ST17) contains an intact acm gene and was previously shown to bind collagen (63).

FIG 4.

NRRL B-2354 acm gene insertion and impaired collagen adherence. (A) Schematic diagram of the acm gene in E. faecium NRRL B-2354 and clinical strain E. faecium TX0082. The genes are 99% identical in the coding regions (gray); however, a 1,059-bp insertion sequence (hatched lines) is located 52 bp from the start codon in NRRL B-2354. (B) E. faecium binding to type I collagen. Absorbance was significantly higher for TX0082 than for the other two strains (Tukey's honestly significant difference [HSD], P < 0.05). The averages ± SD of three replicates per strain are shown.

Pili are associated with enterococcal virulence and biofilm formation (64, 65). Strain NRRL B-2354 contains genes in the ebp and pil operons coding for pilus production (65, 66) (Table 2). However, the transcriptional regulator ebpR, the promoter for the cotranscribed ebpA, ebpB, and ebpC genes, and the first 688 bp of ebpA are absent from strain NRRL B-2354 (Fig. 5A). In total, the deletion encompasses approximately 2 kb in comparison to strain TX0082, a strain confirmed to produce pili encoded by the ebp operon (65). Similarly, pili were detected on the surface of TX0082 but not E. faecium NRRL B-2354 (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material).

FIG 5.

Ebp locus and biofilm formation in E. faecium NRRL B-2354. (A) Schematic diagram of the ebp operon in E. faecium NRRL B-2354 and TX0082. (B) E. faecium biofilm formation on polystyrene. Absorbance was significantly higher for TX0082 than for the other two strains (Tukey's HSD, P < 0.05). The averages ± SD of three replicates per strain are shown.

Because ebp-encoding pili are associated with biofilm formation (65), the capacity of the strains to form biofilms on polystyrene was also measured. Biofilm formation according to cell staining intensities was 5-fold lower for strains NRRL B-2354 and ATCC 8459 than for TX0082 (Fig. 4B). Notably, E. faecium B-2354 has a reduced capacity to form biofilms even though it contains efaA, a manganese-dependent gene encoding an endocarditis-specific antigen involved in biofilm formation (67, 68) (Table 2).

E. faecium NRRL B-2354 contains sagA, a virulence gene associated with endocarditis (Table 2) (69). SagA contributes to binding to fibrinogen, fibronectin, and collagen type I and IV laminin (70) and is also present in TX0082 (67). Accordingly, both E. faecium strains as well as ATCC 8459 bound to fibrinogen and fibronectin at similar levels (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material).

Tolerance to low pH, heat, and ethanol.

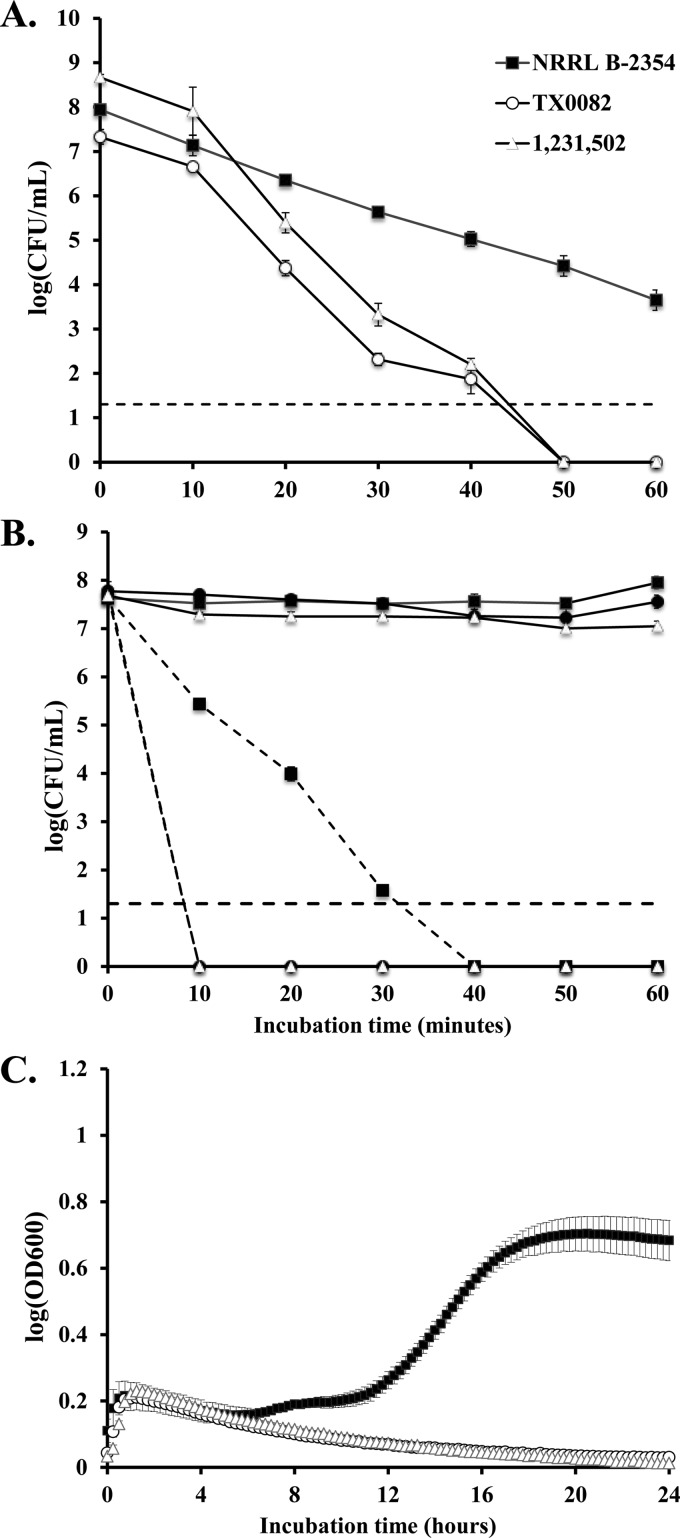

After 20 min of incubation at pH 2.4, E. faecium NRRL B-2354 survived in 10- and 100-fold-larger amounts than the clinical strains TX0082 and 1,231,502 (ST203) (Fig. 6A). Within 50 min of incubation at the acidic pH, NRRL B-2354 exhibited only a 3-log decline, whereas viable cell numbers of the two clinical isolates were reduced by 7 log (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Stress responses to low pH, heat, and ethanol. (A) Survival at pH 2.4. Numbers of viable cells of E. faecium NRRL B-2354, TX 0082, and 1,231,502 were determined at intervals of 10 min during incubation in physiological saline adjusted to pH 2.4. Detection limit was 20 CFU/ml. The averages ± SD of three replicates per strain are shown. (B) Thermal survival of E. faecium in physiological saline. Numbers of viable cells of E. faecium NRRL B-2354, TX 0082, and 1,231,502 were determined at 10-min intervals during incubation at 50°C (solid lines) and 60°C (dashed lines). Detection limit (black dashed line) was 20 CFU/ml. The averages ± SD of three replicates per strain are shown. (C) Ethanol tolerance of E. faecium. Growth of E. faecium strains NRRL B-2354, TX 0082, and 1,231,502 was monitored during incubation in 8% ethanol for 24 h with absorbance at OD600 measured every 15 min. The averages ± SD of three replicates per strain are shown.

Incubation at 50°C for 60 min was not detrimental to the viability of E. faecium NRRL B-2354, TX0082, and 1,231,502 (Fig. 6B). At an incubation temperature of 60°C for 10 min, there was a decline of over 7 log in viability of strains TX0082 and 1,231,502 (Fig. 6B). In contrast, a 2-log decline was observed for NRRL B-2354 after 60 min at 60°C (Fig. 6B).

E. faecium NRRL B-2354, TX0082, and 1,231,502 were unable to grow in BHI in the presence of 12% ethanol (data not shown). When the culture medium contained 8% ethanol, only NRRL B-2354 was able to grow (Fig. 6C). E. faecium NRRL B-2354 exhibited a longer lag phase in this medium, and the cells reached a 1.3-fold-lower final optical density than did cells grown in BHI lacking ethanol (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

E. faecium NRRL B-2354, a commonly used strain with a long history in food products and thermal process validation, lacks the majority of virulence factors known for this species and is sensitive to medically relevant antibiotics. These features are consistent with its genomic relationship to nonclinical (NC), or community, strains of E. faecium. Overall, the findings of this study support the continued use of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 and its clonal relative ATCC 8459 in the validation of processing equipment used for thermal treatment of food products.

Comparative genomics approaches have previously concluded that there is a significant evolutionary distance between clinical and community isolates of E. faecium (11–19). In the present study, whole-genome, PBP5, and MLST comparisons revealed that E. faecium NRRL B-2354 is most similar to nonclinical strains. This result is in agreement with the original isolation of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 from dairy utensils. Among nonclinical strains, NRRL B-2354 belongs to the newly identified NC2 clade (34). Although the origins of NC2 are currently unclear (16, 17, 19), it is notable that NC2 strains share similar PBP5 amino acid sequences associated with ampicillin resistance. Divergence of NC2 clade strains, including NRRL B-2354, might therefore be in accordance with pbp5 evolution.

E. faecium NRRL B-2354 contains 45 unique genes not present in the 125 other E. faecium genomes examined here. The majority of these genes encode phage-associated proteins or have unknown function. These genes were distributed among five loci (SP1 to SP5) throughout the genome, suggestive of separate gene integration events. Further investigation is needed to elucidate whether these genes confer unique functionality to NRRL B-2354, particularly with regard to its association with dairy products and high levels of environmental stress tolerance.

Like other NC strains, E. faecium NRRL B-2354 has fewer ME, AR, and VF genes than strains isolated from clinical settings. A lower abundance of those genes is also related to the smaller genome sizes of NC strains (16, 19). In contrast to the low number of ME, NRRL B-2354 lacks CRISPR-cas systems associated with protection against ME-associated foreign DNA, including AR and VF genes (55). The significantly lower number of ME in cas-negative NC strains supports the possibility that other factors are also important to ME susceptibility in E. faecium.

The lack of AR genes in E. faecium NRRL B-2354 is in agreement with the sensitivity of this strain to medically relevant antibiotics, including but not limited to vancomycin. Although this strain contains a pbp5-R allele, it is also sensitive to ampicillin. Resistance of E. faecium to either vancomycin or ampicillin severely limits treatment options for enterococcal infections. While strain NRRL B-2354 exhibited an intermediate level of resistance to erythromycin, this trait is common among other food-associated E. faecium (71).

E. faecium NRRL B-2354 also lacks or contains nonfunctional copies of the majority of known and established enterococcal virulence factors. This includes esp, hyl, and IS16 commonly found in clinical isolates (56, 72). Those loci were specified by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) as targets for the safety evaluation of E. faecium strains intended as additives for animal feed (73). EFSA recommends examining for the presence of esp, hyl, and IS16 as well as sensitivity to ampicillin as exclusion criteria (73). E. faecium NRRL B-2354 lacks these genes and, as discussed above, is sensitive to ampicillin. Therefore, this strain meets the requirements for safety by the EFSA guidelines. These results were shared with American Type Culture Collection and were deemed sufficient for ATCC to classify the clonal strain in the biosafety level 1 (BSL-1) category (Brian Beck, ATCC, personal communication). Furthermore, based on this information, USDA agreed to remove reference to BSL-2 for NRRL B-2354 (Todd Ward, personal communication).

Additionally, we examined the NRRL B-2354 genome for other E. faecium VF, including secreted enzymes and cell surface proteins. Genotype and phenotype assessments confirmed that E. faecium NRRL B-2354 lacks the capacity to produce gelatinase and cytolysin. These enzymes are most often found in CL-associated strains of E. faecium and have been directly linked to enterococcal virulence in animal models of infection (74, 75). Cell surface proteins associated with enterococcal virulence include functions in biofilm formation and adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen, fibrinogen, and fibronectin (65, 76). E. faecium NRRL B-2354 contains partial or nonfunctional copies of acm encoding a collagen I adhesin and the ebp operon for pilus production.

E. faecium NRRL B-2354 does contain complete and hence likely functional copies of sagA, scm, efaA, and the pilA operon. The majority of these genes apparently did not contribute to the phenotypes tested here (i.e., collagen adherence, pilus production, and biofilm formation). Overall, these genes are not as well characterized as other known E. faecium virulence determinants (8). Although NRRL B-2354 adhered to fibrinogen and fibronectin, possibly through SagA, this phenotype has also been described for probiotic Lactobacillus strains (77, 78) and has been detected for dairy-associated strains of E. faecium (79). Such functions might be important for intestinal colonization and regarded as “niche factors,” as has been suggested for probiotic lactobacilli (80).

Unlike the clinical strains TX0082 and 1,231,502, E. faecium NRRL B-2354 exhibited a heightened capacity to survive environmental stresses. These are useful characteristics for a surrogate microorganism which should exhibit levels of stress tolerance similar to those of the human pathogens that they are intended to mimic, such as strains of Salmonella. Stress tolerance in lactic acid bacterium relatives of E. faecium is due to a variety of metabolic and stress response pathways (81, 82). It is notable that E. faecium NRRL B-2354 exhibited superior acid, heat, and ethanol stress tolerance levels, possibly indicating that similar mechanisms are involved in conferring to this strain the capacity to survive/grow under those conditions. E. faecium NRRL B-2354 contains numerous genes coding for stress-responsive proteins, including an FoF1 ATPase, certain transcriptional regulators (ctsR), and chaperones and proteases (dnaK, groEL, grpE, ftsH, htrA, clpB, clpC, clpE, clpP, and clpX) (data not shown). However, the genomes of the hospital-associated strains TX0082 and 1,231,502 also contain the majority of these genes. Hence, future studies should investigate the specific mechanisms by which E. faecium NRRL B-2354 and not TX0082 and 1,231,502 can survive environmental stresses. This information would also be useful for predicting which organisms would be suitable surrogates.

Despite its common occurrence in foods, E. faecium has not been causally linked to food-borne infection (1). Instead, experimental and clinical infections caused by this species appear to be the result of contact by certain strains of this species to extraintestinal sites on the body through catheters, surgeries, or poor sanitation (8). Hence, E. faecium NRRL B-2354 presents a clear example of the need for strain- and application-specific evaluations rather than species level designations on safety. Future studies should further clarify the exact mechanisms of E. faecium pathogenesis and distinguish between strains that have acquired distinct traits for colonization of extraintestinal sites on the human body and those that benefit food safety and human health.

Presently, there are few bacterial surrogate strains available to validate processes used to control food-borne pathogens in food processing (83, 84). As for any bacterial strain, E. faecium NRRL B-2354 should be handled with appropriate care; however, it lacks the genomic and phenotypic characteristics that define strains of this species responsible for nosocomial infections. The data presented here along with the long history of safe use of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 and its clonal representative ATCC 8459 support its continued role in the safe production of foods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Grete Adamson and Patricia Kysar from the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Electron Microscopy Lab, Davis, CA, for their assistance with the electron microscopy. We thank Lex Overmars for assistance with genome assembly. We also thank the UC Davis Medical Center for their assistance with the antibiotic resistance testing. We also kindly thank Barbara Murray for providing strain E. faecium TX0082, Michael Gilmore for providing strain 1,231,502, and Catherine Strong for Bacillus cereus strain ATCC 14579.

This project was supported by the Almond Board of California.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 10 January 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03859-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Franz CM, Huch M, Abriouel H, Holzapfel W, Galvez A. 2011. Enterococci as probiotics and their implications in food safety. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 151:125–140. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benyacoub J, Czarnecki-Maulden GL, Cavadini C, Sauthier T, Anderson RE, Schiffrin EJ, von der Weid T. 2003. Supplementation of food with Enterococcus faecium (SF68) stimulates immune functions in young dogs. J. Nutr. 133:1158–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nocek JE, Kautz WP. 2006. Direct-fed microbial supplementation on ruminal digestion, health, and performance of pre- and postpartum dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 89:260–266. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeyner A, Boldt E. 2006. Effects of a probiotic Enterococcus faecium strain supplemented from birth to weaning on diarrhoea patterns and performance of piglets. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 90:25–31. 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2005.00615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agerholm-Larsen L, Bell ML, Grunwald GK, Astrup A. 2000. The effect of a probiotic milk product on plasma cholesterol: a meta-analysis of short-term intervention studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 54:856–860. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hlivak P, Odraska J, Ferencik M, Ebringer L, Jahnova E, Mikes Z. 2005. One-year application of probiotic strain Enterococcus faecium M-74 decreases serum cholesterol levels. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 106:67–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surono IS, Koestomo FP, Novitasari N, Zakaria FR, Yulianasari Koesnandar. 2011. Novel probiotic Enterococcus faecium IS-27526 supplementation increased total salivary sIgA level and bodyweight of pre-school children: a pilot study. Anaerobe 17:496–500. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arias CA, Murray BE. 2012. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:266–278. 10.1038/nrmicro2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sava IG, Heikens E, Huebner J. 2010. Pathogenesis and immunity in enterococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:533–540. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J. 2009. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1–12. 10.1086/595011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christoffersen TE, Jensen H, Kleiveland CR, Dorum G, Jacobsen M, Lea T. 2012. In vitro comparison of commensal, probiotic and pathogenic strains of Enterococcus faecalis. Br. J. Nutr. 108:2043–2053. 10.1017/S0007114512000220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Regt MJ, van Schaik W, van Luit-Asbroek M, Dekker HA, van Duijkeren E, Koning CJ, Bonten MJ, Willems RJ. 2012. Hospital and community ampicillin-resistant Enterococcus faecium are evolutionarily closely linked but have diversified through niche adaptation. PLoS One 7:e30319. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mannu L, Paba A, Daga E, Comunian R, Zanetti S, Duprè I, Sechi LA. 2003. Comparison of the incidence of virulence determinants and antibiotic resistance between Enterococcus faecium strains of dairy, animal and clinical origin. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 88:291–304. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00191-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vancanneyt M, Lombardi A, Andrighetto C, Knijff E, Torriani S, Bjorkroth KJ, Franz C, Moreno MRF, Revets H, De Vuyst L, Swings J, Kersters K, Dellaglio F, Holzapfel WH. 2002. Intraspecies genomic groups in Enterococcus faecium and their correlation with origin and pathogenicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1381–1391. 10.1128/AEM.68.3.1381-1391.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galloway-Pena J, Roh JH, Latorre M, Qin X, Murray BE. 2012. Genomic and SNP analyses demonstrate a distant separation of the hospital and community-associated clades of Enterococcus faecium. PLoS One 7:e30187. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lebreton F, van Schaik W, Manson McGuire A, Godfrey P, Griggs A, Mazumdar V, Corander J, Cheng L, Saif S, Young S, Zeng Q, Wortman J, Birren B, Willems RJL, Earl AM, Gilmore MS. 2013. Emergence of epidemic multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium from animal and commensal strains. mBio 4:e00534–13. 10.1128/mBio.00534-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer KL, Godfrey P, Griggs A, Kos VN, Zucker J, Desjardins C, Cerqueira G, Gevers D, Walker S, Wortman J, Feldgarden M, Haas B, Birren B, Gilmore MS. 2012. Comparative genomics of enterococci: variation in Enterococcus faecalis, clade structure in E. faecium, and defining characteristics of E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus. mBio 3:e00318–11. 10.1128/mBio.00318-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pessione A, Lamberti C, Cocolin L, Campolongo S, Grunau A, Giubergia S, Eberl L, Riedel K, Pessione E. 2012. Different protein expression profiles in cheese and clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecalis revealed by proteomic analysis. Proteomics 12:431–447. 10.1002/pmic.201100468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim EB, Marco ML. 2014. Nonclinical and clinical strains of Enterococcus faecium but not Enterococcus faecalis strains have distinct structural and functional genomic features. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80:154–165. 10.1128/AEM.03108-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin X, Galloway-Pena JR, Sillanpaa J, Hyeob Roh J, Nallapareddy SR, Chowdhury S, Bourgogne A, Choudhury T, Munzy DM, Buhay CJ, Ding Y, Dugan-Rocha S, Liu W, Kovar C, Sodergren E, Highlander S, Petrosino JF, Worley KC, Gibbs RA, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. 2012. Complete genome sequence of Enterococcus faecium strain TX16 and comparative genomic analysis of Enterococcus faecium genomes. BMC Microbiol. 12:135. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam MM, Seemann T, Bulach DM, Gladman SL, Chen H, Haring V, Moore RJ, Ballard S, Grayson ML, Johnson PD, Howden BP, Stinear TP. 2012. Comparative analysis of the first complete Enterococcus faecium genome. J. Bacteriol. 194:2334–2341. 10.1128/JB.00259-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornacki JL. 2012. Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354: tempest in a teapot or serious foodborne pathogen? Food Safety Magazine Apr-May:38–45 http://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/magazine-archive1/april-may-2012/enterococcus-faecium-nrrl-b-2354-tempest-in-a-teapot-or-serious-foodborne-pathogen/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergan T, Bovre K, Hovig B. 1970. Present status of the species Micrococcus freudenreichii. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 20:249–254. 10.1099/00207713-20-3-249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma L, Kornacki JL, Zhang GD, Lin CM, Doyle MP. 2007. Development of thermal surrogate microorganisms in ground beef for in-plant critical control point validation studies. J. Food Prot. 70:952–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almond Board of California 24 October 2007. Guidelines for process validation using Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354. http://www.almondboard.com/Handlers/Documents/Enterococcus-Validation-Guidelines.pdf

- 26.Yang JH, Bingol G, Pan ZL, Brandl MT, McHugh TH, Wang H. 2010. Infrared heating for dry-roasting and pasteurization of almonds. J. Food Eng. 101:273–280. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2010.07.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bingol G, Yang JH, Brandl MT, Pan ZL, Wang H, McHugh TH. 2011. Infrared pasteurization of raw almonds. J. Food Eng. 104:387–393. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2010.12.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeong S, Marks BP, Ryser ET. 2011. Quantifying the performance of Pediococcus sp. (NRRL B-2354: Enterococcus faecium) as a nonpathogenic surrogate for Salmonella Enteritidis PT30 during moist-air convection heating of almonds. J. Food Prot. 74:603–609. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Annous BA, Kozempel MF. 1998. Influence of growth medium on thermal resistance of Pediococcus sp NRRL B-2354 (formerly Micrococcus freudenreichii) in liquid foods. J. Food Prot. 61:578–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piyasena P, McKellar RC, Bartlett FM. 2003. Thermal inactivation of Pediococcus sp in simulated apple cider during high-temperature short-time pasteurization. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 82:25–31. 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00264-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim EB, Tyler CA, Kopit LM, Marco ML. 2013. Draft genome sequence of fructophilic Lactobacillus florum. Genome Announc. 1:e00025. 10.1128/genomeA.00025-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boisvert S, Laviolette F, Corbeil J. 2010. Ray: simultaneous assembly of reads from a mix of high-throughput sequencing technologies. J. Comput. Biol. 17:1519–1533. 10.1089/cmb.2009.0238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Au KF, Underwood JG, Lee L, Wong WH. 2012. Improving PacBio long read accuracy by short read alignment. PLoS One 7:e46679. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. 2008. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. 2007. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:3100–3108. 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schattner P, Brooks AN, Lowe TM. 2005. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W686–W689. 10.1093/nar/gki366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu B, Pop M. 2009. ARDB—antibiotic resistance genes database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D443–D447. 10.1093/nar/gkn656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki R, Shimodaira H. 2006. Pvclust: an R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 22:1540–1542. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rice LB, Bellais S, Carias LL, Hutton-Thomas R, Bonomo RA, Caspers P, Page MGP, Gutmann L. 2004. Impact of specific pbp5 mutations on expression of β-lactam resistance in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3028–3032. 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3028-3032.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Homan WL, Tribe D, Poznanski S, Li M, Hogg G, Spalburg E, van Embden JDA, Willems RJL. 2002. Multilocus sequence typing scheme for Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1963–1971. 10.1128/JCM.40.6.1963-1971.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rizk G, Lavenier D. 2010. GASSST: global alignment short sequence search tool. Bioinformatics 26:2534–2540. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vankerckhoven V, Van Autgaerden T, Vael C, Lammens C, Chapelle S, Rossi R, Jabes D, Goossens H. 2004. Development of a multiplex PCR for the detection of asa1, gelE, cylA, esp, and hyl genes in enterococci and survey for virulence determinants among European hospital isolates of Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4473–4479. 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4473-4479.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willems RJ, Homan W, Top J, van Santen-Verheuvel M, Tribe D, Manzioros X, Gaillard C, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Mascini EM, van Kregten E, van Embden JD, Bonten MJ. 2001. Variant esp gene as a marker of a distinct genetic lineage of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium spreading in hospitals. Lancet 357:853–855. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04205-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayat MA. 1989. Principles and techniques of electron microscopy biological applications, 3rd ed. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eaton TJ, Gasson MJ. 2001. Molecular screening of Enterococcus virulence determinants and potential for genetic exchange between food and medical isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1628–1635. 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1628-1635.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nomura R, Nakano K, Taniguchi N, Lapirattanakul J, Nemoto H, Gronroos L, Alaluusua S, Ooshima T. 2009. Molecular and clinical analyses of the gene encoding the collagen-binding adhesin of Streptococcus mutans. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:469–475. 10.1099/jmm.0.007559-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins J, van Pijkeren J-P, Svensson L, Claesson MJ, Sturme M, Li Y, Cooney JC, van Sinderen D, Walker AW, Parkhill J, Shannon O, O'Toole PW. 2012. Fibrinogen-binding and platelet-aggregation activities of a Lactobacillus salivarius septicaemia isolate are mediated by a novel fibrinogen-binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 85:862–877. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08148.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toledo-Arana A, Valle J, Solano C, Arrizubieta MJ, Cucarella C, Lamata M, Amorena B, Leiva J, Penades JR, Lasa I. 2001. The enterococcal surface protein, Esp, is involved in Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4538–4545. 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4538-4545.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galloway-Peña JR, Rice LB, Murray BE. 2011. Analysis of PBP5 of early U.S. isolates of Enterococcus faecium: sequence variation alone does not explain increasing ampicillin resistance over time. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3272–3277. 10.1128/AAC.00099-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arias CA, Contreras GA, Murray BE. 2010. Management of multidrug-resistant enterococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:555–562. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03214.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murray BE. 1990. The life and times of the Enterococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 3:46–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deveau H, Garneau JE, Moineau S. 2010. CRISPR/Cas system and its role in phage-bacteria interactions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:475–493. 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palmer KL, Gilmore MS. 2010. Multidrug-resistant enterococci lack CRISPR-cas. mBio 1:e0027–10. 10.1128/mBio.00227-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Werner G, Fleige C, Geringer U, van Schaik W, Klare I, Witte W. 2011. IS element IS16 as a molecular screening tool to identify hospital-associated strains of Enterococcus faecium. BMC Infect. Dis. 11:80. 10.1186/1471-2334-11-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Su YA, Sulavik MC, He P, Makinen KK, Makinen PL, Fiedler S, Wirth R, Clewell DB. 1991. Nucleotide sequence of the gelatinase gene (gelE) from Enterococcus faecalis subsp. liquefaciens. Infect. Immun. 59:415–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rice LB, Carias L, Rudin S, Vael C, Goossens H, Konstabel C, Klare I, Nallapareddy SR, Huang WX, Murray BE. 2003. A potential virulence gene, hyl(Efm), predominates in Enterococcus faecium of clinical origin. J. Infect. Dis. 187:508–512. 10.1086/367711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coburn PS, Gilmore MS. 2003. The Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin: a novel toxin active against eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. Cell. Microbiol. 5:661–669. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eaton TJ, Gasson MJ. 2002. A variant enterococcal surface protein Esp(fm) in Enterococcus faecium; distribution among food, commensal, medical, and environmental isolates. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 216:269–275. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11446.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sillanpaa J, Nallapareddy SR, Prakash VP, Qin X, Hook M, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. 2008. Identification and phenotypic characterization of a second collagen adhesin, Scm, and genome-based identification and analysis of 13 other predicted MSCRAMMs, including four distinct pilus loci, in Enterococcus faecium. Microbiology 154:3199–3211. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/017319-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Murray BE. 2008. Contribution of the collagen adhesin Acm to pathogenesis of Enterococcus faecium in experimental endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 76:4120–4128. 10.1128/IAI.00376-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Okhuysen PC, Murray BE. 2008. A functional collagen adhesin gene, acm, in clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecium correlates with the recent success of this emerging nosocomial pathogen. Infect. Immun. 76:4110–4119. 10.1128/IAI.00375-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim DS, Singh KV, Nallapareddy SR, Qin X, Panesso D, Arias CA, Murray BE. 2010. The fms21 (pilA)-fms20 locus encoding one of four distinct pili of Enterococcus faecium is harboured on a large transferable plasmid associated with gut colonization and virulence. J. Med. Microbiol. 59:505–507. 10.1099/jmm.0.016238-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sillanpaa J, Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Prakash VP, Fothergill T, Hung TT, Murray BE. 2010. Characterization of the ebp(fm) pilus-encoding operon of Enterococcus faecium and its role in biofilm formation and virulence in a murine model of urinary tract infection. Virulence 1:236–246. 10.4161/viru.1.4.11966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hendrickx AP, Bonten MJ, van Luit-Asbroek M, Schapendonk CM, Kragten AH, Willems RJ. 2008. Expression of two distinct types of pili by a hospital-acquired Enterococcus faecium isolate. Microbiology 154:3212–3223. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020891-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Low YL, Jakubovics NS, Flatman JC, Jenkinson HF, Smith AW. 2003. Manganese-dependent regulation of the endocarditis-associated virulence factor EfaA of Enterococcus faecalis. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:113–119. 10.1099/jmm.0.05039-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh KV, Coque TM, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. 1998. In vivo testing of an Enterococcus faecalis efaA mutant and use of efaA homologs for species identification. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 21:323–331. 10.1016/S0928-8244(98)00087-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kropec A, Sava IG, Vonend C, Sakinc T, Grohmann E, Huebner J. 2011. Identification of SagA as a novel vaccine target for the prevention of Enterococcus faecium infections. Microbiology 157:3429–3434. 10.1099/mic.0.053207-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Teng F, Kawalec M, Weinstock GM, Hryniewicz W, Murray BE. 2003. An Enterococcus faecium secreted antigen, SagA, exhibits broad-spectrum binding to extracellular matrix proteins and appears essential for E. faecium growth. Infect. Immun. 71:5033–5041. 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5033-5041.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sanchez Valenzuela A, Lavilla Lerma L, Benomar N, Galvez A, Perez Pulido R, Abriouel H. 2013. Phenotypic and molecular antibiotic resistance profile of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolated from different traditional fermented foods. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10:143–149. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Billstrom H, Lund B, Sullivan A, Nord CE. 2008. Virulence and antimicrobial resistance in clinical Enterococcus faecium. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 32:374–377. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.European Food Safety Authority 2012. Guidance on the safety assessment of Enterococcus faecium in animal nutrition. EFSA J. 10:2682–2692. 10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2682 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thurlow LR, Thomas VC, Narayanan S, Olson S, Fleming SD, Hancock LE. 2010. Gelatinase contributes to the pathogenesis of endocarditis caused by Enterococcus faecalis. Infect. Immun. 78:4936–4943. 10.1128/IAI.01118-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kayaoglu G, Orstavik D. 2004. Virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis: relationship to endodontic disease. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 15:308–320. 10.1177/154411130401500506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao M, Sillanpaa J, Nallapareddy SR, Murray BE. 2009. Adherence to host extracellular matrix and serum components by Enterococcus faecium isolates of diverse origin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 301:77–83. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01806.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Munoz-Provencio D, Perez-Martinez G, Monedero V. 2010. Characterization of a fibronectin-binding protein from Lactobacillus casei BL23. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108:1050–1059. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04508.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goh YJ, Klaenhammer TR. 2010. Functional roles of aggregation-promoting-like factor in stress tolerance and adherence of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:5005–5012. 10.1128/AEM.00030-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Banwo K, Sanni A, Tan H. 2013. Technological properties and probiotic potential of Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from cow milk. J. Appl. Microbiol. 114:229–241. 10.1111/jam.12031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hill C. 2012. Virulence or niche factors: what's in a name? J. Bacteriol. 194:5725–5727. 10.1128/JB.00980-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mills S, Stanton C, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP. 2011. Enhancing the stress responses of probiotics for a lifestyle from gut to product and back again. Microb. Cell Fact. 10(Suppl 1):S19. 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Bokhorst-van de Veen H, Abee T, Tempelaars M, Bron PA, Kleerebezem M, Marco ML. 2011. Short- and long-term adaptation to ethanol stress and its cross-protective consequences in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:5247–5256. 10.1128/AEM.00515-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sinclair RG, Rose JB, Hashsham SA, Gerba CP, Haas CN. 2012. Criteria for selection of surrogates used to study the fate and control of pathogens in the environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:1969–1977. 10.1128/AEM.06582-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Busta FF, Suslow TV, Parish ME, Beuchat LR, Farber JN, Garrett EH, Harris LJ. 2003. The use of indicators and surrogate microorganisms for the evaluation of pathogens in fresh and fresh-cut produce. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety 2:179–185. 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00035.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.