Abstract

Chicken raised under commercial conditions are vulnerable to environmental exposure to a number of pathogens. Therefore, regular vaccination of the flock is an absolute requirement to prevent the occurrence of infectious diseases. To combat infectious diseases, vaccines require inclusion of effective adjuvants that promote enhanced protection and do not cause any undesired adverse reaction when administered to birds along with the vaccine. With this perspective in mind, there is an increased need for effective better vaccine adjuvants. Efforts are being made to enhance vaccine efficacy by the use of suitable adjuvants, particularly Toll-like receptor (TLR)-based adjuvants. TLRs are among the types of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize conserved pathogen molecules. A number of studies have documented the effectiveness of flagellin as an adjuvant as well as its ability to promote cytokine production by a range of innate immune cells. This minireview summarizes our current understanding of flagellin action, its role in inducing cytokine response in chicken cells, and the potential use of flagellin as well as its combination with other TLR ligands as an adjuvant in chicken vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

A significant sector of world agriculture is formed by the poultry industry. The major problem faced by the industry is a loss of productivity due to infectious diseases. Therefore, proper monitoring and active health management of the birds are required (1–3). Currently, active immunization using live virus vaccines is a routine practice. An effective vaccine not only needs a good antigen but also requires an appropriate adjuvant to enhance the immunogenicity of the antigen. Newer-generation vaccines, including recombinant vaccines, mostly fail to produce a strong immune response (4). Such vaccines need adjuvants which can augment the antigenicity of the antigen so that an enhanced immune response can be achieved.

Traditionally used adjuvants are inorganic compounds, bacterial products, and complex mixtures of surface-active compounds, mineral oil, and synthetic polymers (5, 6). Adjuvants based on alum and mineral oil are the most commonly used adjuvants. Freund's complete adjuvant is an effective mineral oil-based adjuvant, but it shows high levels of adverse local painful reaction and tissue damage at the injection site and may cause systemic disorders in chicken (7, 8). Alum suffers from weak adjuvant activity as well as being associated with the induction of IgE antibody response and may cause allergic reactions (9). Recent developments in innate immunity mark a new era of TLR-based adjuvants which can substantially enhance the immune response to vaccines (10). The innate immune system recognizes unique conserved molecular patterns of pathogens (pathogen-associated molecular patterns [PAMPs]) through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (11). Recognition through PRRs alerts the immune system to mount a quick response to limit the spread of infection (12). TLRs are among the types of PRRs. In mammals, 13 TLRs have been reported, with each recognizing and responding to different pathogen molecules (13). Different ligands of TLRs include pathogen molecules such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (TLR4), flagellar protein and peptidoglycans (TLR1, TLR2, TLR5, and TLR6) (14, 15), viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (TLR3) (16), bacterial and viral unmethylated cytosine-guanosine-containing oligonucleotides (CpG-ODN) (TLR9), and single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) (TLR7 and TLR8) (17–19). Recently, TLR11 and TLR12 have been shown to recognize profilin in Toxoplasma gondii infection whereas TLR13 senses the rRNA sequence CGGAAAGACC (20–22).

To date, 10 TLRs have been identified in chicken and include TLR1A and TLR1B, TLR2A and TLR2B, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR7, TLR15, and TLR21 (23–25). Further, TLR21, which is a functional orthologue of mammalian TLR9, recognizes CpG-ODN whereas LPS and flagellin are recognized by TLR4 and TLR5, respectively (26–30). Mammalian counterparts of TLR8 and TLR9 seem to be defective in chicken, although chicken TLR3 appears to recognize dsRNA in a manner similar to that seen in mammals (31, 32). TLR15 has been shown to detect yeast proteases (33).

To combat infectious bacterial and viral diseases, depending upon the causative agent, humoral as well as cell-mediated immune responses may be required. Clearance of bacterial diseases may require robust humoral immunity (34, 35). Viral diseases, apart from humoral immunity, require cell-mediated immunity. For example, cellular immunity is crucial in Newcastle disease virus (NDV) infection because the viral pathogenesis includes an intracellular phase (36). This necessitates the use of an agent that can elicit both types of immune response.

CpG-ODN, a TLR21 ligand, has been reported to be an effective adjuvant, but its use has been limited due to its adsorption by nonrelevant tissues and transient biological activity due to a short half-life in vivo (6). Though modification increases its half-life, it does not render it completely resistant to nuclease activity and it still undergoes slow degradation (37). Poor cellular uptake, nonspecificity, toxicity, and severe side effects upon long-term use are some other disadvantages associated with the modification (38–41).

Another microbial component, TLR5 ligand flagellin, a major structural protein of Gram-negative flagella, is a potent inducer of cytokine and chemokine production and has shown tremendous potential as an adjuvant in various investigations (42–44).

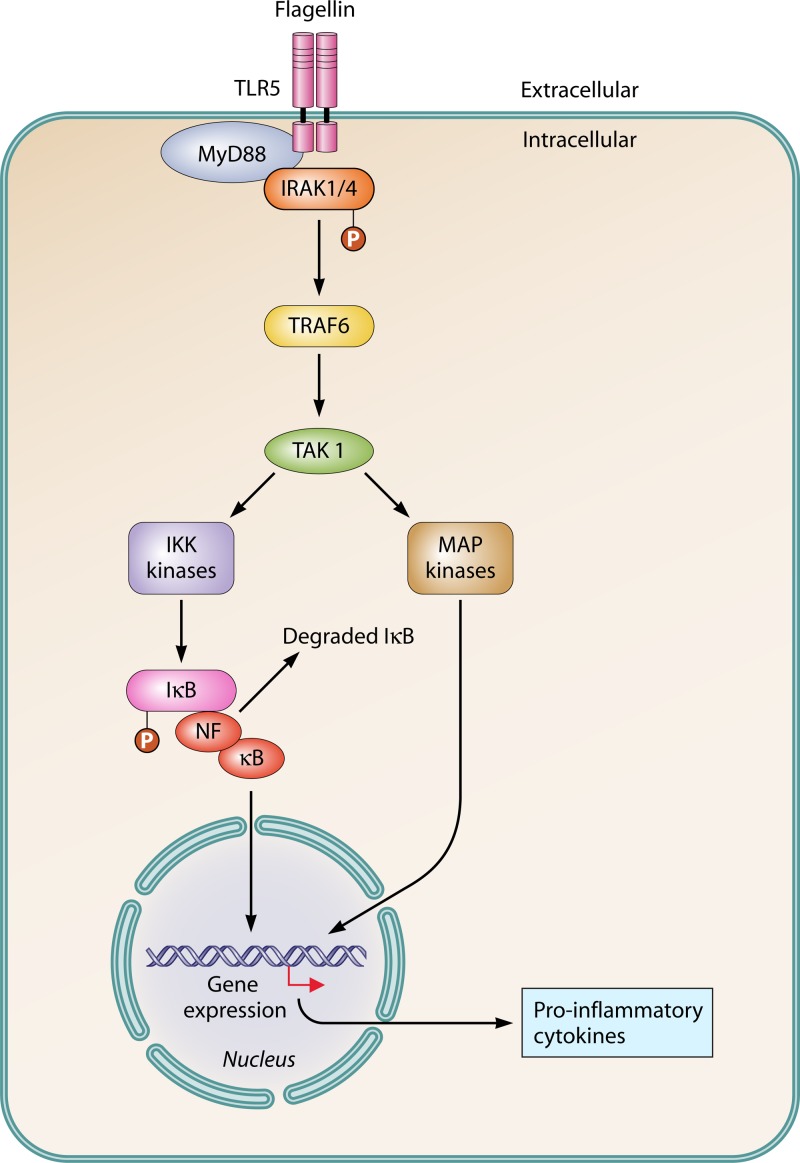

TLR5 SIGNALING

TLRs have recently emerged as key components of the innate immune system that sense microbial infections and elicit antimicrobial host defense responses. Binding of a ligand to its specific TLR initiates a cascade of reactions leading to production of various inflammatory cytokines and type 1 interferons (IFN) (45, 46). TLR signaling consists of two distinct pathways: a MyD88-dependent pathway and a MyD88-independent pathway. The MyD88-dependent pathway is used by all the TLRs except TLR3, while TLR4 uses both the pathways (16, 47). Flagellin binding to TLR5 activates the MyD88-dependent pathway (Fig. 1). Analysis of MyD88-deficient mice revealed the important role of MyD88 in TLR signaling (48). When macrophages from such MyD88-deficient mice were exposed to bacterial components, they failed to produce inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and IL-12 (49, 50). Upon stimulation, MyD88 binds to the cytoplasmic portion of a TLR and recruits IRAK-4 (interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase), IRAK-1, and TRAF6 (TNF receptor-associated factor) to the receptor. IRAK-4 then phosphorylates IRAK-1. TRAF6 with phosphorylated IRAK1 releases from the receptor and activates TAK1 (51). TAK1 (TGF-β-activated kinase 1) then phosphorylates the IκB kinase (IKK) complex and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases. Activation of the IKK complex results in degradation of IkB and activation of NF-κB. Both NF-κB and MAP kinases then cause induction of genes involved in inflammatory responses. These genes, after activation, produce different types of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines which in turn direct and shape the acquired immune response (Fig. 2) (52).

FIG 1.

TLR5 signaling. Flagellin binding to TLR recruits adaptor protein MyD88, leading to the activation of IRAK-1/4 and TRAF-6 and resulting in the activation of NF-κB, which induces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines.

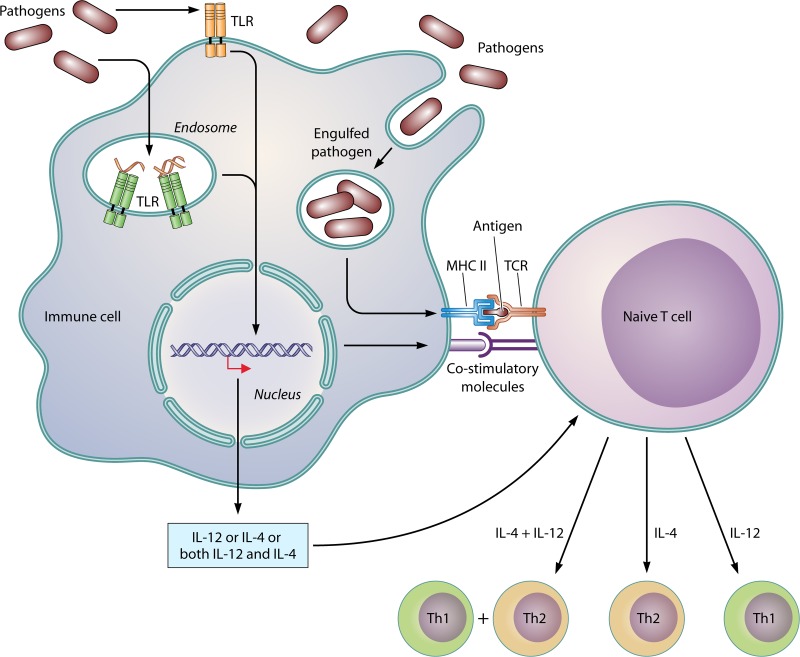

FIG 2.

Mechanism of induction of the type of immune responses following TLR activation.

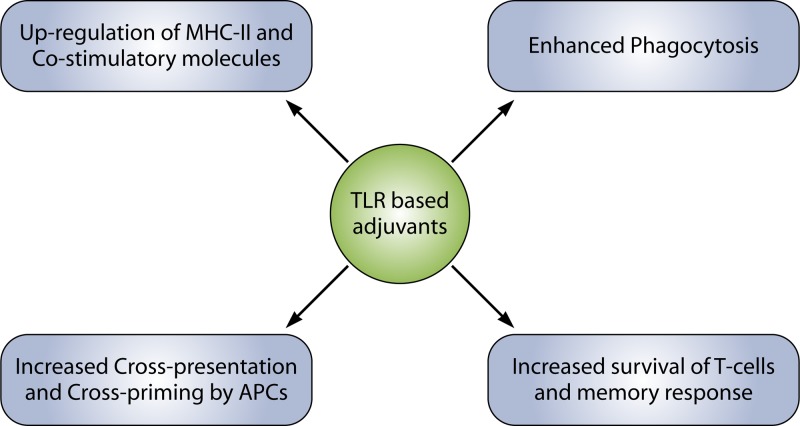

TLR SIGNALING AFFECTS MANY IMMUNOLOGICAL PROCESSES TO ENHANCE THE IMMUNE RESPONSE

TLR ligands seem to affect an array of processes to augment the immune response (Fig. 3). In this regard, production of cytokines upregulates the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) as well as various costimulatory molecules in the antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and upregulation of CD70 and CD40 molecules results in the activation of T and B cells (53, 54). TLR signaling and phagocytosis are distinctive features of macrophage-mediated innate immune responses to bacterial infection. Many studies have reported an enhanced rate of phagocytosis due to TLR signaling. Engagement of TLRs induces MyD88-dependent signaling through the activation of IRAK-4 and p38, causing upregulation of expression of a number of genes associated with phagocytosis (55–57).

FIG 3.

TLR ligands affect many immunological processes to elicit an elevated immune response.

Detection of microbial components by TLR enhances efficiency of vaccination by upregulating the cross-presentation and cross-priming ability of APCs (58). TLRs have also been reported to be present on CD4+ T cells, suggesting that microbial components may directly induce activated CD4+ T cell survival without any help from the APCs (40). This effect is mediated directly though the activation of the NF-κB pathway following TLR ligation (59, 60). These studies indicated a function of TLRs in the activation of adaptive immune cells and the involvement of effector memory T cells in innate immunity.

FLAGELLIN: A TLR5 AGONIST

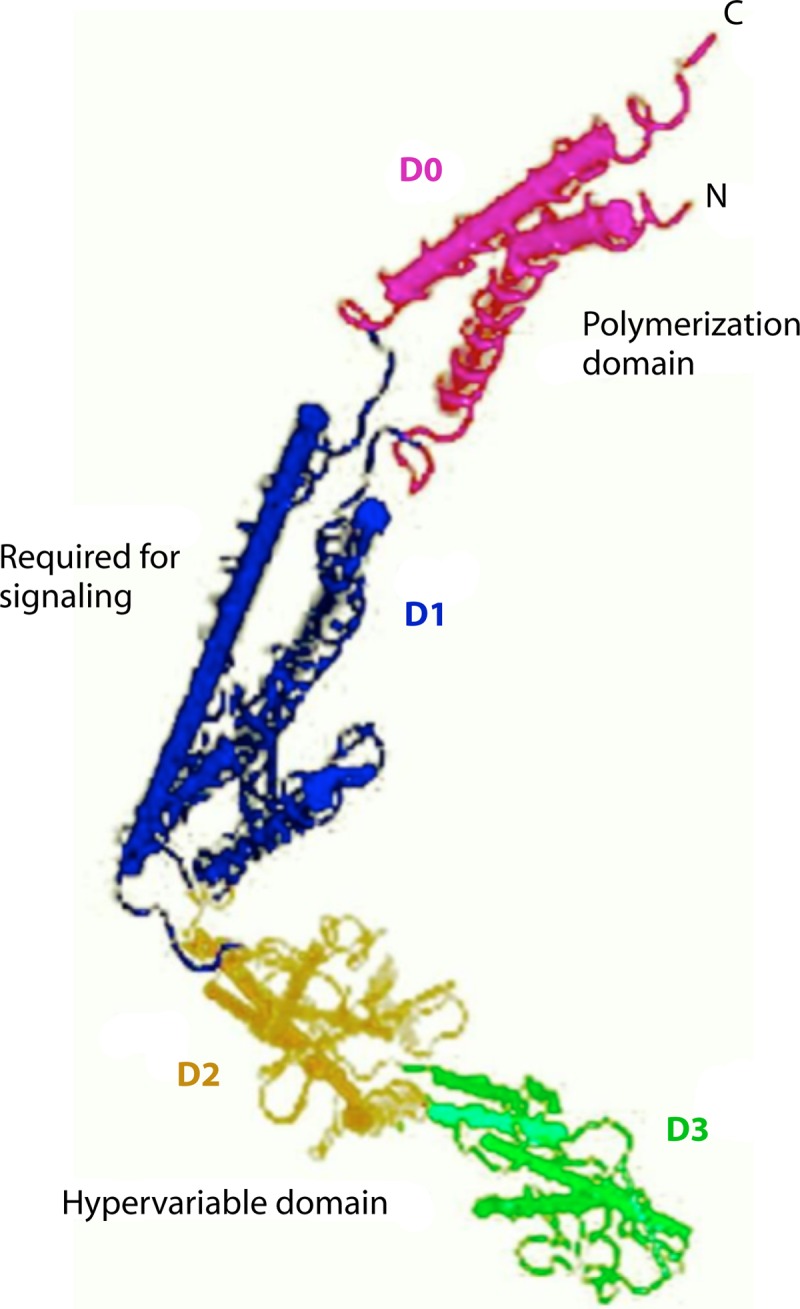

Structure.

Flagellin is a globular protein that arranges itself in a hollow cylinder to form the filament in bacterial flagellum and is present in large amounts in nearly all flagellated bacteria (61, 62). Flagellar protein consists of the four domains D0, D1, D2, and D3. The D0 and D1 domains are mostly helical in structure and have a highly conserved sequence of amino acids at the N and C termini of the primary sequence of protein across the species. The D2 and D3 domains form the hypervariable region (Fig. 4). Systemic deletion studies of flagellin protein have revealed that the TLR5-activating region of flagellin is located within the conserved domains of the protein (29). Deletion of the first 99 amino acids from the N terminus of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium flagellin monomer prevented TLR5 recognition, while deletions that removed amino acids 416 to 444 within the C terminus of flagellin were also sufficient to abolish the recognition of protein by TLR5 (29). The variable D3 domain is present at the surface of the flagellar filament, and it has been reported to have immunostimulatory activity. This makes this domain important for innate immune recognition (63, 64).

FIG 4.

Structure of flagellin with four major domains indicated (NCBI; GenBank accession no. KF589316).

Individuals become susceptible to Legionnaires' disease when a stop codon mutation occurs in TLR5 (65). Occurrence of a stop codon mutation makes such individuals unable to recognize flagellated bacteria and, hence, unable to mount a proinflammatory response mediated through TLR5-flagellin signaling. This accounts for the greater susceptibility of such individuals to Legionella infection (65). Absence of TLR5 in mice makes them more susceptible to Escherichia coli urinary tract infection, suggesting that TLR5 regulates the innate immune response in the urinary tract (66). Furthermore, TLR5-deleted mice have been reported to develop spontaneous colitis whereas another study suggested that the flagellin-induced pulmonary inflammatory response is TLR5 dependent (67, 68). Taken together, these studies strongly suggest that the functional status of the TLR5-mediated flagellin response in the host determines the host susceptibility to the infectious diseases.

In chicken, TLR5 has been reported to be expressed in lungs, kidney, colon, spleen, testes, and heart (23). TL5 expression has also been detected in the immune cells of chicken such as heterophils, monocytes, Langerhans cells, NK cells, and T and B cells of the adaptive immune system (69–71).

Flagellin as an adjuvant in chicken.

In chicken, many of the previous studies (Table 1) performed with flagellated bacteria such as S. enterica serovar Typhimurium have also revealed the potential of flagellar protein flagellin in activating the immune system of the host. In this context, infection of chicken TLR5-expressing HeLa cells with S. enterica serovar Enteritidis activated high levels of NF-κB in a dose- and flagellin-dependent manner (72). In another study, aflagellar S. enterica serovar Typhimurium fliM induced less IL-1β and IL-6 production than was seen with wild-type flagellated bacteria in chicken and the aflagellar bacteria had a greater ability for systemic infection (23). S. enterica serovar Gallinarum, a nonflagellated bacterium, shows reduced invasiveness and elicits reduced levels of cytokines and chemokines. de Freitas Neto et al. (73) produced flagellated strains of this bacterium and infected chicken kidney cells (CKC) with these strains along with the parent strain. The flagellated strain (S. enterica serovar Gallinarum Fla+) induced higher levels of CXCLi2, inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase (iNOS), and IL-6 mRNA expression in CKC than were seen in the nonflagellated parent strain. In other TLR5-flagellin interactions, chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) produced more IL-1β, IL-6, CXCLi2, and CCLi2 in response to S. enterica serovar Enteritidis infection (74). Pan et al. (75) also investigated the effect of flagellin-deficient mutant S. enterica serovar Typhimurium on the immune system of the chicken in vivo. Mutant (flagellin-deficient) strains showed a greater ability to establish systemic infection and elicited reduced levels of IL-1β and CXCLi2 compared to the wild-type bacteria. An absence of TLR5-flagellin-mediated production of various proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines may account for the enhanced ability of the flagellin-deficient mutant to cause systemic infections (23, 75). Taken together, all these studies indicated that the Salmonella flagellin protein is involved in triggering the innate immune responses.

TABLE 1.

Summary of TLR5-mediated adjuvant action of flagellated Salmonella strains

| Study model | Result(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Chicken kidney cells (CKC) | Flagellated strains S. Enteritidis and S. Gallinarum (Fla+) induced higher levels of CXCLi2, iNOS, and IL-6; less mortality with flagellated strains | 73 |

| Chicken (in vivo) | Flagellin-deficient mutants exhibited enhanced ability for systemic infections; lower levels of IL-1β and CXCLi2 than wild type | 75 |

| Chicken PBMCs | TLR5-flagellin-mediated upregulation of IL-1β, IL-6, CXCLi2, and CCLi2 expression in S. Enteritidis-infected cells | 74 |

| CKC and HD11 | Flagellated S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium induced more IL-6, CXCLi1, CXCLi2, and iNOS than nonflagellated S. Pullorum and S. Gallinarum | 105 |

| HeLa cells expressing chicken TLR5 | Induced more NF-κB in response to S. Enteritidis infection in a dose- and flagellin-dependent manner | 72 |

| Chicken (in vivo) | Reduced levels of IL-1β and IL-6 and enhanced ability to establish systemic infection after challenge with aflagellar S. Typhimurium | 23 |

| Intestinal epithelial cells | Flagellin-deficient S. Typhimurium mutant (fliC, fljB, and flhD) failed to elicit IL-8 expression | 52 |

A number of studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of flagellin as an adjuvant in chicken immune cells in vitro (Table 2). Heterophils showed an increased oxidative burst and a significant upregulation of various proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8) and chemokines (CXCLi2) in response to flagellin (76, 77). Isolated chicken monocytes stimulated with flagellin showed upregulated nitric oxide production, which indicates enhanced macrophage function (78). Furthermore, chicken macrophage-like cells (HD11), chicken kidney epithelial cells (CKC), and chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEF) have been shown to upregulate production of IL-1β when stimulated with flagellin (23). Keestra et al. (72) reported that the increased proinflammatory response was due to TLR5-flagellin-mediated enhanced production of NF-κB in HeLa cells expressing chicken TLR5.

TABLE 2.

Flagellin as an adjuvant in chicken: applications in vitro

| Cell category | Response(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Chicken PBMCs | Upregulation of both IL-12 and IL-4 as well as IL-6 | 79 |

| Chicken splenocytes | Induction of a mixed Th1- and Th2-like response | 80 |

| Chicken heterophils | Upregulation of IL-6 and CXCLi2 | 100 |

| HeLa cells with chicken TLR5 | Upregulation of TLR5-flagellin-mediated NF-κB expression | 72 |

| Chicken monocytes | Induction of nitric oxide production | 78 |

| Chicken heterophils | Increased oxidative burst; significant production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines | 77 |

| CEF, CKC HD11 cells | Significant upregulation of IL-1β | 23 |

| Chicken heterophils | Significant upregulation of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 and increased oxidative burst | 76 |

Recent studies aimed at exploring the potential of flagellin as an adjuvant have reported a mixed induction of Th1 and Th2 immune responses in chicken cells (79, 80). We have found that when chicken PBMCs were stimulated with recombinant flagellin, both Th1 and Th2 cytokines (Th1–IL-12 and Th2–IL-4) were detected along with proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 (79). The same pattern of cytokine production (Th1–IL-12, gamma interferon [IFN-γ], and Th2–IL-4 and –IL-13) was observed in chicken splenocytes (80).

Many in vivo investigations were undertaken looking at the promising results of various in vitro studies with purified or recombinant flagellin in chicken immune cells (Table 3). In this regard, flagellin administered in vivo enhanced the infiltration of heterophils into the site of injection, which suggests that flagellin is a potent stimulator of a heterophil-mediated innate immune response in vivo and can protect against Salmonella infections in chickens (81). Although the exact mechanism behind this phenomenon was not clearly documented, it was reasoned to be mediated by the TLR5-flagellin-induced production chemotactic factor IL-8 (76).

TABLE 3.

Flagellin as an adjuvant in chicken: applications in vivo

| Antigen | Result(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Immune-mapped protein-1 (IMP-1) of Eimeria tenella (EtIMP1) | Flagellin-fused EtIMP1 elicited a stronger protective immune response; reduced mortality | 83 |

| Avian influenza virus | Increased IgY and IgA | 82 |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis | Increased IgA and decreased bacterial counts | 34 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Increased Ig and decreased bacterial load | 35 |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis | Reduced mortality | 81 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Increased Ig and decreased bacterial load | 101 |

Use of flagellin in recombinant vaccine can elicit a greater immune response (82). Chaung et al. (82) investigated the adjuvant effects of the monomeric and polymeric forms of Salmonella flagellin in specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chickens immunized intramuscularly or intranasally with inactivated avian influenza virus H5N2 vaccines. Results showed that flagellin cooperating with the 64CpG adjuvant significantly induced influenza virus-specific antibody titers of plasma IgA in the vaccinated animals. The nasal IgA levels in the flagellin-coadministered avian influenza virus-vaccinated chickens were significantly elevated compared to levels observed with the H5N2 vaccine alone. Okamura et al. (34) used recombinant flagellin protein from S. enterica serovar Enteritidis and tested its potential in a vaccine candidate against homologous challenge in chickens. After immunization with recombinant flagellin or administration of phosphate-buffered saline, the chickens were challenged with S. enterica serovar Enteritidis. The vaccinated birds showed significantly decreased bacterial counts in the liver and cecal contents compared to those administered phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Recombinant vectors based on S. enterica serovar Typhimurium have also been used. Pan et al. (75) developed a recombinant S. enterica vector expressing the fusion protein (F) gene of NDV; experimental data revealed that recombinant vector induced higher levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), CXCLi2, and TLR5 mRNAs in the cecum, the spleen, and the heterophils. Huang et al. (35) used flagellin as an adjuvant against Campylobacter jejuni and reported an increased Ig and decreased bacterial load in the birds. Further, flagellin has also been used as an adjuvant against Eimeria tenella. A recent study demonstrated the potential of flagellin as an adjuvant against parasitic infections (83). A fusion protein consisting of flagellin and immune-mapped protein-1 (IMP-1), an antigenic protein of Eimeria tenella, elicited a stronger immune response than recombinant IMP-1 with Freund's complete adjuvant, showing that flagellin can also be used to enhance the immunogenicity of parasite antigens. Flagellin-antigen fusion proteins hold great potential and can be effectively used once the antigenic region of a pathogen is identified.

Flagellin as an adjuvant in combination with other TLR ligands.

Recent studies have shown that when two or more TLRs are activated simultaneously, their pathways interact with each other and this cross talk results in either synergistic or antagonistic immune response (84, 85). TLR combinations can produce a stronger and selective immune response, and a number of studies have been undertaken in mice as well as in human immune cells (86–91). In chicken, many combinations have also been tried to establish the pattern of cytokine production and induction of the type of immune response (Table 4). In this context, costimulation with TLR3 and TLR21 ligands synergistically upregulated IFN-γ and IL-10 expression in chicken monocytes (92). A combination of CpG-ODN and poly(I·C) synergistically stimulated a proinflammatory immune response in chicken monocytes that included nitric oxide (NO) production and expression of iNOS and of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (93, 94). Flagellin has also been used in combination with other agonists. In a previous study, cross talk between TLR5 and TLR9 on human PBMCs resulted in a more robust production of IL-10 and IFN-γ but antagonized IL-12 production (86). In another study, we have reported that a combination of recombinant flagellin and LPS synergistically upregulated nitric oxide production and IL-12 and IL-6 expression but antagonistically downregulated IL-4 expression in comparison to recombinant flagellin alone. The results indicate that these agonists synergistically interact and enhance macrophage function and promote Th1 immune response in chicken PBMCs (79). Our study (79) also favored the use of combinations of these (LPS and recombinant flagellin) agonists, where Th1 type immunity is required, in small doses to alleviate the toxicity-related concerns associated with these agonists. These studies indicated that a single TLR ligand may not be effective enough to combat deadly infectious diseases and that instances occur in which a well-directed immune response is required; hence, in such cases, a novel combination of TLR ligands can be tried to achieve a more effective and selective immune (Th1 or Th2) response in chickens.

TABLE 4.

Adjuvant effect of combinations of TLR agonists on chicken immune cells

| TLR combination | Cell category | Result(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR5 and TLR4 | Chicken PBMCs | Synergistic upregulation of NO, IL-6, and IL-12; antagonistic downregulation of IL-4 | 79 |

| TLR3 and TLR21 | Chicken RBCsa | Synergistic upregulation of type 1 IFNs | 102 |

| TLR3 and TLR21 | Chicken monocytes | Synergistic upregulation of IFN-γ and IL-10 | 103 |

| TLR4 and TLR21 | Chicken thrombocytes | Synergistic upregulation of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 | 104 |

| TLR3 and TLR21 | Chicken monocytes | Synergistic upregulation of NO, IL-1β, IL-6, and MIP-1β | 92 |

| TLR3 and TLR21 | Chicken monocytes | Synergistic upregulation of NO production | 94 |

RBCs, red blood cells.

Advantages of flagellin as an adjuvant in chicken vaccine.

Flagellin has emerged as a potential adjuvant candidate for vaccines due to a number of advantages associated with it. It has been shown to be effective at very low doses (81, 82), and previous immunity does not alter its adjuvant activity, as it has high affinity for TLR5 (95, 96). Being protein in nature, it can be manipulated and epitopes can be fused with its N or C terminus as well as in the hypervariable region without affecting its binding ability with TLR5 (97, 98). Further, it can easily be made in a large quantity using recombinant DNA technology. Flagellin can also be used in DNA vaccination, where the gene encoding flagellin can be placed next to an antigenic epitope. An expression vector containing the fliC gene was made and was given to mice against a lethal challenge of influenza A virus. Results of the experiment indicated that expression of DNA-encoded TLR agonists by mammalian cells greatly enhanced and broadened immune responses to influenza A virus (99). Flagellin can also be used in a recombinant viral vector carrying an antigenic gene. In this regard, flagellin has successfully been used as an adjuvant in a recombinant vector expressing a viral protein (75).

CONCLUSION

Flagellin exhibits a range of immunological effects on a number of cell types in the host. It has been seen that the TLR5 ligand flagellin induced the chicken immune system and elicited a mixed Th1 and Th2 response, though with an inclination toward a Th2 response (79, 80). However, we observed (79) that flagellin used in combination with LPS induced a Th1 response in chicken PBMCs. Also, many of the other TLR agonists induce a predominantly Th1 response, thereby making flagellin an attractive option under both sets of conditions; for example, when an elevated antibody-mediated immune response is desired, flagellin alone might be used, and in cases where cell-mediated immunity is required, combination with LPS might be tried (79). However, the particular type of response may further be influenced by several factors, including the dose of flagellin or antigen, the cell subtypes, and the route of immunization, as well as its combination with other agonists (79). Though many of the in vivo studies undertaken suggest flagellin to be a potent adjuvant in chickens (76, 77, 79), toxicity-related concerns over the use of flagellin in birds cannot be ignored. This necessitates the detailed in vivo investigation of the use of flagellin in chickens. A good option to avoid toxicity concerns might be the use of a combination of flagellin with another TLR ligand; such combinations will help in reducing the quantity of the agonists used and, hence, toxicity-related concerns in chickens. Thus, flagellin is an effective adjuvant, but detailed in vivo investigations to measure long-term safety as well as the determination of factors such as the route of administration and dose will provide a foundation for the use of flagellin and its combinations with other TLR ligands as an adjuvant in future development of vaccines against infectious diseases of chicken.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Biographies

Shishir Kumar Gupta obtained his graduate degree in Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) from Bombay Veterinary College (BVC), Mumbai, India. He joined the Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI) for his Master's degree in Animal Biotechnology and Immunology and worked on the potential use of TLR ligands and their combinations as adjuvant in new-generation recombinant chicken vaccines in the Recombinant DNA Laboratory of this institute. He received a fellowship from the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) during his thesis research work. Currently, he is pursuing his Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree from the same institute and working in the area of viral oncolysis. He is receiving a fellowship from CSIR (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research) for his Ph.D. research work.

Preety Bajwa graduated in Biotechnology from the Chaudhary Charan Singh University and obtained her M.Tech. in Biotechnology with specialization in Genetic Engineering from the School of Biotechnology, Gautam Buddha University. During her Master's studies, she enrolled in the Laboratory of Gut Inflammation and Infection Biology at the Regional Centre for Biotechnology, Gurgaon, India, for her research thesis. Her work involves understanding the mechanism of Salmonella-mediated alteration of host SUMOyation. Currently, she is working as a Senior Research fellow (SRF) in a DBT project at G.B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, India. Her project is based on creation of a double-gene mutant of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and testing of its immune potential.

Rajib Deb obtained his Master's degree in Animal Biotechnology from Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI), Uttar Pradesh, India. His postgraduate research work was on development of a bicistronic DNA vaccine against Mycobacterium paratuberculosis using gamma interferon as an adjuvant. Presently, he is pursuing his Ph.D. in Animal Biotechnology from the same institute. His Ph.D. research work involves developing a chimeric DNA vaccine against infectious bursal diseases (IBD) of poultry that incorporates the flagellin (fliC) gene of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium as an adjuvant. He is also presently employed as an Agricultural Research Scientist (ARS) under the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), government of India.

Madhan Mohan Chellappa obtained his Master of Veterinary Science in Animal Biotechnology in 1997 and Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Animal Biotechnology in 2003 from the Department of Animal Biotechnology, Madras Veterinary College, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University (TANUVAS), Chennai, India. In 2000 he was appointed Scientist in the Division of Veterinary Biotechnology, Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI), India. He was awarded with a Department of Biotechnology (DBT) overseas fellowship by the government of India in 2006 for pursuing a postdoctoral program at the University of Maryland and a Commonwealth fellowship by the Association of Commonwealth Universities, United Kingdom, in 2011 to pursue research work at the Institute of Animal Health, Pirbright, United Kingdom. Currently, he is holding the position of Senior Scientist at the Indian Veterinary Research Institute. His research interests include development of new-generation vaccines by reverse genetics and diagnostics against important poultry viral diseases with special reference to Newcastle disease virus.

Sohini Dey obtained her Master of Veterinary Science in Animal Biotechnology in 1997 and Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Animal Biotechnology in 2003 from the Department of Animal Biotechnology, Madras Veterinary College, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University (TANUVAS), Chennai, India. In 2000, she was appointed Scientist in the Division of Veterinary Biotechnology, Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI), India. She was awarded with a DBT overseas fellowship by the government of India in 2006 for pursuing a postdoctoral program at the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute and a BOYSCAST fellowship under the Department of Science and Technology in 2010 to pursue research work at the Institute of Animal Health, Pirbright, United Kingdom. Currently, she is holding the position of Senior Scientist at the Indian Veterinary Research Institute. Her research interests include development of virus-like particles and new-generation vaccines and diagnostics against important poultry viral diseases.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 January 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Bowersock TL. 2002. Evolving importance of biologics and novel delivery systems in the face of microbial resistance. AAPS PharmSci. 4:e33. 10.1208/ps040433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohan CM, Dey S, Rai A, Kataria JM. 2006. Recombinant haemagglutinin neuraminidase antigen-based single serum dilution ELISA for rapid serological profiling of Newcastle disease virus. J. Virol. Methods 138:117–122. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dey S, Upadhyay C, Mohan CM, Kataria JM, Vakharia VN. 2009. Formation of subviral particles of the capsid protein VP2 of infectious bursal disease virus and its application in serological diagnosis. J. Virol. Methods 157:84–89. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Hagan DT, MacKichan ML, Singh M. 2001. Recent developments in adjuvants for vaccines against infectious diseases. Biomol. Eng. 18:69–85. 10.1016/S1389-0344(01)00101-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser CK, Diener KR, Brown MP, Hayball JD. 2007. Improving vaccines by incorporating immunological coadjutants. Expert Rev. Vaccines 6:559–578. 10.1586/14760584.6.4.559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heegaard Peter MH, Dedieu L, Johnson N, Potier ML, Mockey M, Vahlenkamp FMT, Vascellari M, Sørensen NS. 2011. Adjuvants and delivery systems in veterinary vaccinology: current state and future developments. Arch. Virol. 156:183–202. 10.1007/s00705-010-0863-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt P, Erhard MH, Wanke R, Hofmann A, Schmahl W. 1996. Local reactions after the application of several adjuvants in the chicken. ALTEX 13:30–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wanke R, Schmidt P, Erhard MH, Messing AS, Stangassinger M, Schmahl W, Hermanns W. 1996. Freund's complete adjuvant in the chicken: efficient immunostimulation with severe local inflammatory reaction. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. A 43:243–253 (In German.) 10.1111/j.1439-0442.1996.tb00450.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta RK. 1998. Aluminum compounds as vaccine adjuvants. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 32:155–172. 10.1016/S0169-409X(98)00008-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. 2010. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity 33:492–503. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. 2002. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:197–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. 2001. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2:675–680. 10.1038/90609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Z, Cai Z, Sanchez A, Zhang T, Wen S, Wang J, Yang J, Fu S, Zhang D. 2011. A novel Toll-like receptor that recognizes vesicular stomatitis virus. J. Biol. Chem. 286:4517–4524. 10.1074/jbc.M110.159590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow JC, Young DW, Golenbock DT, Christ WJ, Gusovsuredsky F. 1999. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 274:10689–10692. 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, Kirschning CJ. 1999. Peptidoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17406–17409. 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. 2001. Recognition of double stranded RNA and activation of NF-kB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature 413:732–738. 10.1038/35099560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeshita F, Leifer CA, Gursel I, Ishii KJ, Takeshita S, Gursel M. 2001. Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 9 in CpG DNA-induced activation of human cells. J. Immunol. 167:3555–3558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heil F, Ahmad-Nejad P, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Gellert T, Dietrich H, Lipford G, Takeda K, Akira S, Wagner H, Bauer S. 2003. The Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)-specific stimulus loxoribine uncovers a strong relationship within the TLR7, 8 and 9 subfamily. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:2987–2997. 10.1002/eji.200324238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. 2004. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single stranded RNA. Science 303:1529–1531. 10.1126/science.1093616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yarovinsky F, Zhang D, Andersen JF, Bannenberg GL, Serhan CN, Hayden MS, Hieny S, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA, Ghosh S, Sher A. 2005. TLR11 activation of dendritic cells by a protozoan profilin-like protein. Science 308:1626–1629. 10.1126/science.1109893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koblansky AA, Jankovic D, Oh H, Hieny S, Sungnak W, Mathur R, Hayden MS, Akira S, Sher A, Ghosh S. 2013. Recognition of profilin by toll-like receptor 12 is critical for host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity 38:119–130. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manzoor Z, Koh YS. 2012. Bacterial 23S ribosomal RNA, a ligand for Toll-like receptor 13. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 42:357–358. 10.4167/jbv.2012.42.4.357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iqbal M, Philbin VJ, Smith AL. 2005. Expression patterns of chicken Toll like receptor mRNA in tissues, immune cell subsets, and cell lines. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 104:117–127. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgs R, Cormican P, Cahalane S, Allan B, Lloyd AT, Meade K, James T, Lynn DJ, Babiuk LA, O'Farrelly C. 2006. Induction of a novel chicken Toll-like receptor following Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect. Immun. 74:1692–1698. 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1692-1698.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruan WK, Zheng SJ. 2011. Polymorphisms of chicken toll-like receptor 1 type 1 and type 2 in different breeds. Poult. Sci. 90:1941–1947. 10.3382/ps.2011-01489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brownlie R, Zhu J, Allan B, Mutwiri GK, Babiuk LA, Potter A, Griebel P. 2009. Chicken TLR21 acts as a functional homologue to mammalian TLR9 in the recognition of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Mol. Immunol. 46:3163–3170. 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keestra AM, de Zoete MR, Bouwman LI, van Putten JP. 2010. Chicken TLR21 is an innate CpG DNA receptor distinct from mammalian TLR9. J. Immunol. 185:460–467. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, Hawn TR, Yi EC, Goodlett DR, Eng Akira JKS, Underhill DM, Aderem A. 2001. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature 410:1099–1103. 10.1038/35074106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith KD, Andersen-Nissen E, Hayashi F, Strobe K, Bergman MA, Barrett SLR, Cookson BT, Aderem A. 2003. Toll-like receptor 5 recognizes a conserved site on flagellin required for protofilament formation and bacterial motility. Nat. Immunol. 4:1247–1253. 10.1038/ni1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keestra AM, van Putten JP. 2008. Unique properties of the chicken TLR4/MD-2 complex: selective lipopolysaccharide activation of the MyD88-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 181:4354–4362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philbin VJ, Iqbal M, Boyd Y, Goodchild MJ, Beal RK, Bumstead N, Young J, Smith AL. 2005. Identification and characterization of a functional, alternatively spliced Toll like receptor 7 (TLR7) and genomic disruption of TLR8 in chickens. Immunology 114:507–521. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02125.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarz H, Schneider K, Ohnemus A, Lavric M, Kothlow S, Bauer S, Kaspers B, Staeheli P. 2007. Chicken Toll-like receptor 3 recognizes its cognate ligand when ectopically expressed in human cells. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 27:97–101. 10.1089/jir.2006.0098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyd AC, Peroval MY, Hammond JA, Prickett MD, Young JR, Smith AL. 2012. TLR15 is unique to avian and reptilian lineages and recognizes a yeast-derived agonist. J. Immunol. 189:4930–4938. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okamura M, Matsumoto W, Seike F, Tanaka Y, Teratani C, Tozuka M, Kashimoto T, Takehara K, Nakamura M, Yoshikawa Y. 2012. Efficacy of soluble recombinant FliC protein from Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis as a potential vaccine candidate against homologous challenge in chickens. Avian Dis. 56:354–358. 10.1637/9986-111011-Reg.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang J, Yin Y-X, Pan Z, Zhang G, Zhu A, Liu X, Jiao X. 2010. Intranasal immunization with chitosan/pCAGGS-flaA nanoparticles inhibits Campylobacter jejuni in a White Leghorn model. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010:589476. 10.1155/2010/589476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khalifeh MS, Amawi MM, Abu-Basha EA, Yonis IB. 2009. Assessment of humoral and cellular-mediated immune response in chickens treated with tilmicosin, florfenicol, or enrofloxacin at the time of Newcastle disease vaccination. Poult. Sci. 88:2118–2124. 10.3382/ps.2009-00215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levin AA. 1999. A review of the issues in the pharmacokinetics and toxicology of phosphorothioate antisense oligonucleotides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1489:69–84. 10.1016/S0167-4781(99)00140-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sands H, Gorey-Feret LJ, Cocuzza AJ, Hobbs FW, Chidester D, Trainor GL. 1994. Biodistribution and metabolism of internally 3H-labeled oligonucleotides. I. Comparison of a phosphodiester and a phosphorothioate. Mol. Pharmacol. 45:932–943 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Q, Matson S, Herrera CJ, Fisher E, Yu H, Krieg AM. 1993. Comparison of cellular binding and uptake of antisense phosphodiester, phosphorothioate, and mixed phosphorothioate and methylphosphonate oligonucleotides. Antisense Res. Dev. 3:53–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deng GM, Nilsson IM, Verdrengh M, Collins LV, Tarkowski A. 1999. Intra-articularly localized bacterial DNA containing CpG motifs induces arthritis. Nat. Med. 5:702–705. 10.1038/9554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golali E, Jaafari MR, Khamesipour A, Abbasi A, Saberi Z, Badiee A. 2012. Comparison of in vivo adjuvanticity of liposomal PO CpG ODN with liposomal PS CpG ODN: soluble leishmania antigens as a model. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 15:1032–1045 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McEwen J, Levi R, Horwitz RJ, Arnon R. 1992. Synthetic recombinant vaccine expressing influenza haemagglutinin epitope in Salmonella flagellin leads to partial protection in mice. Vaccine 10:405–411. 10.1016/0264-410X(92)90071-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levi R, Arnon R. 1996. Synthetic recombinant influenza vaccine induces efficient long-term immunity and cross-strain protection. Vaccine 14:85–92. 10.1016/0264-410X(95)00088-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeon SH, Ben-Yedidia T, Arnon R. 2002. Intranasal immunization with synthetic recombinant vaccine containing multiple epitopes of influenza virus. Vaccine 20:2772–2780. 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00187-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki N, Suzuki S, Yeh WC. 2002. IRAK-4 as the central TIR signaling mediator in innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 23:503–506. 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02298-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Neill LA. 2002. Signal transduction pathways activated by the IL-1 receptor/toll-like receptor superfamily. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 270:47–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doyle S, Vaidya S, O'Connell R, Dadgostar H, Dempsey P, Wu T, Rao G, Sun R, Haberland M, Modlin R, Cheng G. 2002. IRF3 mediates a TLR3/TLR4-specific antiviral gene program. Immunity 17:251–263. 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00390-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, Akira S. 2003. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science 301:640–643. 10.1126/science.1087262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. 1998. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science 282:2085–2088. 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. 1999. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J. Immunol. 162:3749–3752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. 2009. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 388:621–625. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gewirtz AT, Navas TA, Lyons S, Godowski PJ, Madara JL. 2001. Cutting edge: bacterial flagellin activates basolaterally expressed TLR5 to induce epithelial proinflammatory gene expression. J. Immunol. 167:1882–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayashi F, Means TK, Luster AD. 2003. Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood 102:2660–2669. 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diehl L, den Boer AT, Schoenberger SP, van der Voort EI, Schumacher TN, Melief CJ. 1999. CD40 activation in vivo overcomes peptide-induced peripheral cytotoxic T lymphocyte tolerance and augments anti-tumor vaccine efficacy. Nat. Med. 5:774–779. 10.1038/10495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. 2004. Regulation of phagosome maturation by signals from toll-like receptors. Science 304:1014–1018. 10.1126/science.1096158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doyle SE, O'Connell RM, Miranda GA, Vaidya SA, Chow EK, Liu PT, Suzuki S, Suzuki N, Modlin RL, Yeh W, Lane TF, Cheng G. 2004. Toll-like receptors induce a phagocytic gene program through p38. J. Exp. Med. 199:81–90. 10.1084/jem.20031237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yates RM, Russell DG. 2005. Phagosome maturation proceeds independently of stimulation of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Immunity 23:409–417. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Datta SK, Vanessa R, Kiley R, Prilliman KT, Maripat C, Thomas T, Joseph D, Roman D, Shizuo A, Stephen PS, Eyal Raz. 2003. A subset of Toll-like receptor ligands induces cross-presentation by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 170:4102–4110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gelman AE, Zhang J, Choi Y, Turka LA. 2004. Toll-like receptor ligands directly promote activated CD4+ T cell survival. J. Immunol. 17:6065–6073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caron G, Dorothée D, Isabelle F, Pascale Catherine JD, Hugues G, Yves Delneste. 2005. Direct stimulation of human T cells via TLR5 and TLR7/8: flagellin and R-848 up-regulate proliferation and IFN-γ production by memory CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 175:1551–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berg HC, Anderson RA. 1973. Bacteria swim by rotating their flagellar filaments. Nature 245:380–382. 10.1038/245380a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fedorov OV, Kostyukova AS. 1984. Domain structure of flagellin. FEBS Lett. 171:145–148. 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80476-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McDermott PF, Ciacci-Woolwine F, Snipes JA, Mizel SB. 2000. High-affinity interaction between gram-negative flagellin and a cell surface polypeptide results in human monocyte activation. Infect. Immun. 68:5525–5529. 10.1128/IAI.68.10.5525-5529.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steiner TS, Nataro JP, Poteet-Smith CE, Smith JA, Guerrant RL. 2000. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli expresses a novel flagellin that causes IL-8 release from intestinal epithelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 105:1769–1777. 10.1172/JCI8892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hawn TR, Verbon A, Lettinga KD, Zhao LP, Li SS, Laws RJ, Skerrett SJ, Beutler B, Schroeder L, Nachman A, Ozinsky A, Smith KD, Aderem A. 2003. A common dominant TLR5 stop codon polymorphism abolishes flagellin signaling and is associated with susceptibility to Legionnaires' disease. J. Exp. Med. 198:1563–1572. 10.1084/jem.20031220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andersen-Nissen TR, Hawn KD, Smith A, Nachman AE, Lampano S, Uematsu S, Akira A, Aderem A. 2007. Cutting edge: Tlr5-/- mice are more susceptible to Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. J. Immunol. 178:4717–4720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vijay-Kumar M, Sanders CJ, Taylor RT, Kumar A, Aitken JD, Sitaraman SV, Neish AS, Uematsu S, Akira S, Williams IR, Gewirtz AT. 2007. Deletion of TLR5 results in spontaneous colitis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 117:3909–3921. 10.1172/JCI33084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feuillet V, Medjane S, Mondor I, Demaria O, Pagni PP, Galán JE, Flavell RA, Alexopoulou L. 2006. Involvement of Toll-like receptor 5 in the recognition of flagellated bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12487–12492. 10.1073/pnas.0605200103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chalifour A, Jeannin P, Gauchat JF, Blaecke A, Malissard M, N′Guyen T, Thieblemont N, Delneste Y. 2004. Direct bacterial protein PAMP recognition by human NK cells involves and triggers alpha-defensin production. Blood 104:1778–1783. 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Farina C, Theil D, Semlinger B, Hohlfeld R, Meinl E. 2004. Distinct responses of monocytes to Toll-like receptor ligands and inflammatory cytokines. Int. J. Immunol. 16:799–809. 10.1093/intimm/dxh083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peiser M, Wanner R, Kolde G. 2004. Human epidermal Langerhans cells differ from monocyte-derived Langerhans cells in CD80 expression and in secretion of IL-12 after CD40 cross-linking. J. Leukoc. Biol. 76:616–622. 10.1189/jlb.0703327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keestra AM, de Zoete MR, van Aubel RA, van Putten JP. 2008. Functional characterization of chicken TLR5 reveals species-specific recognition of flagellin. Mol. Immunol. 45:1298–1307. 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de Freitas Neto OC, Setta A, Imre A, Bukovinski A, Elazomi A, Kaiser P, Berchieri A, Jr, Barrow P, Jones M. 2013. A flagellated motile Salmonella Gallinarum mutant (SG Fla+) elicits a pro-inflammatory response from avian epithelial cells and macrophages and is less virulent to chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 165:425–433. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pan Z, Fang Q, Geng S, Kang X, Cong Q, Jiao X. 2012. Analysis of immune-related gene expression in chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells following Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis infection in vitro. Res. Vet. Sci. 93:716–720. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pan Z, Cong Q, Geng S, Fang Q, Kang X, You M, Jiao X. 2012. Flagellin from recombinant attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium reveals a fundamental role in chicken innate immunity. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 19:304–312. 10.1128/CVI.05569-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kogut MH, Iqbal M, He H, Philbin V, Kaiser P, Smith A. 2005. Expression and function of Toll-like receptors in chicken heterophils. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 29:791–807. 10.1016/j.dci.2005.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kogut MH, Swaggerty C, He H, Pevzner I, Kaiser P. 2006. Toll-like receptor agonists stimulate differential functional activation and cytokine and chemokine gene expression in heterophils isolated from chickens with different innate responses. Microbiol. Infect. 8:1866–1874. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.He H, Genovese KJ, Nisbet DJ, Kogut MH. 2006. Profile of Toll-like receptor expressions and induction of nitric oxide synthesis by Toll-like receptor agonists in chicken monocytes. Mol. Immunol. 43:783–789. 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gupta SK, Deb R, Gaikwad S, Saravanan R, Mohan CM, Dey S. 2013. Recombinant flagellin and its cross-talk with lipopolysaccharide—effect on pooled chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Res. Vet. Sci. 95:930–935. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.St Paul M, Paolucci S, Sharif S. 2012. Treatment with ligands for Toll-like receptors 2 and 5 induces a mixed T-helper 1- and 2-like response in chicken splenocytes. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 32:592–598. 10.1089/jir.2012.0004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Genovese KJ, He H, Lowry VK, Nisbet DJ, Kogut MH. 2007. Dynamics of the avian inflammatory response to Salmonella following administration of the Toll-like receptor 5 agonist flagellin. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51:112–117. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chaung HC, Cheng LT, Hung LH, Tsai PC, Skountzou I, Wang B, Compans RW, Lien YY. 2012. Salmonella flagellin enhances mucosal immunity of avian influenza vaccine in chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 157:69–77. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yin G, Qin M, Liu X, Suo J, Tang X, Tao G, Han Q, Suo X, Wu W. 2013. An Eimeria vaccine candidate based on Eimeria tenella immune mapped protein 1 and the TLR-5 agonist Salmonella typhimurium FliC flagellin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 440:437–442. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Toshchakov V, Jones BW, Perera PY, Thomas K, Cody MJ. 2002. TLR4, but not TLR2, mediates IFN-c-induced STAT1-dependent gene expression in macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 3:392–398. 10.1038/ni774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lotz M, Ebert S, Esselmann H, Iliev AI, Prinz M, Wiazewicz N. 2005. Amyloid beta peptide 1-40 enhances the action of Toll-like receptor-2 and -4 agonists but antagonizes Toll-like receptor-9- induced inflammation in primary mouse microglial cell cultures. J. Neurochem. 94:289–298. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03188.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Merlo A, Calcaterra C, Mènard S, Balsari A. 2007. Cross-talk between Toll-like receptors 5 and 9 on activation of human immune responses. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82:509–518. 10.1189/jlb.0207100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marshall JD, Heeke DS, Gesner ML, Livingston B, Van Nest G. 2007. Negative regulation of TLR9-mediated IFN-α induction by a small-molecule, synthetic TLR7 ligand. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82:497–508. 10.1189/jlb.0906575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ghosh TK, Mickelson DJ, Solberg JC, Lipson KE, Inglefield JR, Alkan SS. 2007. TLR-TLR cross talk in human PBMC resulting in synergistic and antagonistic regulation of type-1 and 2 interferons, IL-12 and TNF-α. Int. Immunopharmacol. 7(8):1111–1121. 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Warger T, Osterloh P, Rechtsteiner G, Fassbender M, Heib V, Schmid B, Schmitt E, Schild H, Radsak MP. 2006. Synergistic activation of dendritic cells by combined Toll-like receptor ligation induces superior CTL responses in vivo. Blood 108:544–550. 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhu Q, Egelston C, Gagnon S, Sui Y, Belyakov IM, Klinman DM, Berzofsky JA. 2010. Using 3 TLR ligands as a combination adjuvant induces qualitative changes in T cell responses needed for antiviral protection in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120:607. 10.1172/JCI39293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vanhoutte F, Paget C, Breuilh L, Fontaine J, Vendeville C, Goriely S, Ryffele B, Faveeuw C, Trottein F. 2008. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR3 synergy and cross-inhibition in murine myeloid dendritic cells. Immunol. Lett. 116:86–94. 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.He H, Mackinnon KM, Genovese KJ, Kogut MH. 2011. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and double-stranded RNA synergize to enhance nitric oxide production and mRNA expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in chicken monocytes. Innate Immunol. 17:137–144. 10.1177/1753425909356937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.He H, Genovese KJ, Swaggerty CL, Nisbet DJ, Kogut MH. 2007. In vivo priming heterophil innate immune functions and increasing resistance to Salmonella enteritidis infection in neonatal chickens by immune stimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 117:275–283. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.He H, Genovese KJ, Nisbet DJ, Kogut MH. 2007. Synergy of CpG oligodeoxynucleotide and double-stranded RNA (poly I:C) on nitric oxide induction in chicken peripheral blood monocytes. Mol. Immunol. 44:3234–3242. 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mizel SB, Bates JT. 2010. Flagellin as an adjuvant: cellular mechanisms and potential. J. Immunol. 185:5677–5682. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Honko AN, Sriranganathan N, Lees CJ, Mizel SB. 2006. Flagellin is an effective adjuvant for immunization against lethal respiratory challenge with Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 74:1113–1120. 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1113-1120.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chauhan N, Kumar R, Badhai J, Preet A, Yadava PK. 2005. Immunogenicity of cholera toxin B epitope inserted in Salmonella flagellin expressed on bacteria and administered as DNA vaccine. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 276:1–6. 10.1007/s11010-005-2240-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mizel SB, Graff A, Sriranganathan N, Ervin S, Lees CJ, Lively MO, Hantgan RR, Thomas MJ, Wood J, Bell B. 2009. Flagellin-F1-V fusion protein is an effective plague vaccine in mice and two species of nonhuman primates. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:21–28. 10.1128/CVI.00333-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Applequist SE, Rollman E, Wareing MD, Lidén M, Rozell B, Hinkula J, Ljunggren HG. 2005. Activation of innate immunity, inflammation, and potentiation of DNA vaccination through mammalian expression of the TLR5 agonist flagellin. J. Immunol. 175:3882–3891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kogut MH, Genovese KJ, He H, Kaiser P. 2008. Flagellin and lipopolysaccharide up-regulation of IL-6 and CXCLi2 gene expression in chicken heterophils is mediated by ERK1/2-dependent activation of AP-1 and NF-κB signaling pathways. Innate Immun. 14:213–222. 10.1177/1753425908094416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Widders PR, Thomas LM, Long KA, Tokhi MA, Panaccio M, Apos E. 1998. The specificity of antibody in chickens immunised to reduce intestinal colonisation with Campylobacter jejuni. Vet. Microbiol. 64:39–50. 10.1016/S0378-1135(98)00251-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.St Paul M, Paolucci S, Barjesteh N, Wood RD, Sharif S. 2013. Chicken erythrocytes respond to Toll-like receptor ligands by up-regulating cytokine transcripts. Res. Vet. Sci. 95:87–91. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.He H, Genovese KJ, Swaggerty CL, MacKinnon KM, Kogut MH. 2012. Co-stimulation with TLR3 and TLR21 ligands synergistically up-regulates Th1-cytokine IFN-γ and regulatory cytokine IL-10 expression in chicken monocytes. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 36:756–760. 10.1016/j.dci.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.St Paul M, Paolucci S, Barjesteh N, Wood RD, Schat KA, Sharif S. 2012. Characterization of chicken thrombocyte responses to Toll-like receptor ligands. PLoS One 7:e43381. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Setta A, Barrow PA, Kaiser P, Jones MA. 2012. Immune dynamics following infection of avian macrophages and epithelial cells with typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica serovars; bacterial invasion and persistence, nitric oxide and oxygen production, differential host gene expression, NF-κB signalling and cell cytotoxicity. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 146:212–224. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]