Abstract

Biofilm formation on catheters is thought to contribute to persistence of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), which represent the most frequent nosocomial infections. Knowledge of genetic factors for catheter colonization is limited, since their role has not been assessed using physicochemical conditions prevailing in a catheterized human bladder. The current study aimed to combine data from a dynamic catheterized bladder model in vitro with in vivo expression analysis for understanding molecular factors relevant for CAUTI caused by Escherichia coli. By application of the in vitro model that mirrors the physicochemical environment during human infection, we found that an E. coli K-12 mutant defective in type 1 fimbriae, but not isogenic mutants lacking flagella or antigen 43, was outcompeted by the wild-type strain during prolonged catheter colonization. The importance of type 1 fimbriae for catheter colonization was verified using a fimA mutant of uropathogenic E. coli strain CFT073 with human and artificial urine. Orientation of the invertible element (IE) controlling type 1 fimbrial expression in bacterial populations harvested from the colonized catheterized bladder in vitro suggested that the vast majority of catheter-colonizing cells (up to 88%) express type 1 fimbriae. Analysis of IE orientation in E. coli populations harvested from patient catheters revealed that a median level of ∼73% of cells from nine samples have switched on type 1 fimbrial expression. This study supports the utility of the dynamic catheterized bladder model for analyzing catheter colonization factors and highlights a role for type 1 fimbriae during CAUTI.

INTRODUCTION

An enormous number of microbial infections in humans are linked to medical device interventions, such as urethral and intravascular catheters, prosthetic grafts, prosthetic joints, and shunts (1). The insertion of medical devices inherently facilitates access of bacterial cells into usually sterile areas of the body and provides an abiotic surface for biofilm formation. The intrinsic resistance of biofilms against host defense mechanisms and antimicrobials limits efficient treatment of biofilm-associated infections. Consequently, biofilm-associated infections are considered a leading cause of morbidity within hospital environments and nursing homes, causing additional health care costs exceeding $1 billion/year in the United States (1).

Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) are the most frequent infections in health care facilities and account for more than one million annual cases of nosocomial bacteriuria in the United States alone (2). Although most cases of CAUTIs are asymptomatic, many patients are at risk of developing severe complications, ranging from cystitis and acute pyelonephritis to bacteremia. The abiotic surface of the catheter inserted to enable urine drainage from the bladder provides an additional substratum for bacterial biofilm formation that is heavily colonized (3). Although the exact contribution of the catheter biofilm to pathogenicity is unknown, the common recurrence of CAUTI soon after the completion of a course of antibiotic treatment is thought to be caused by recolonization of the urine by organisms that have survived in the catheter biofilm. These properties of attached bacteria underlie the clinical experience that efficient antibiotic treatment of CAUTI requires the replacement of the catheter.

A large number of sophisticated in vitro model systems have been applied to understand the basic mechanisms that govern microbial biofilm formation (4–7). One of the most consistent conclusions from these extensive efforts is that biofilm formation of microbes is dependent on the experimental conditions used (8). Flow dynamics, nutrient availability and composition, and other physicochemical properties have been shown to severely affect microbial biofilm formation (see, for example, references 9–11). Thus, although a great deal of knowledge is available based on these systems, the degree to which the resulting mechanistic models of biofilm development can be extrapolated to complex environments in vivo is wholly unknown. In addition, conditions prevailing during current in vivo models for CAUTI that require surgical insertion of catheter pieces (7, 12, 13) differ from the human infection with respect to urine composition, the residual level of urine in the human bladder, and the urine flow through the catheter. This implies that conclusions obtained with CAUTI animal models alone also need to be interpreted with care. Hence, efforts directed to provide more efficient treatment alternatives or efficient prophylaxis for CAUTIs require the use of in vivo CAUTI model systems and dynamic in vitro models that are better able to reproduce the physicochemical conditions during infection in humans.

Escherichia coli is responsible for about 80% of uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTI) (14) and is isolated from the urine of about 30% of patients experiencing CAUTI (15, 16). Despite the significant molecular understanding of the pathogenesis of UTI, research directed to reveal virulence factors that are necessary or specific for the onset, persistence, and progression of CAUTI caused by E. coli is limited (17). Studies using simple in vitro biofilm models have generated an extensive list of potential factors that may assist E. coli in catheter surface colonization and include fimbrial adhesins, autotransporter proteins, capsular structures, flagella, and exopolysaccharides (18–21). However, many of these factors have not been evaluated in, e.g., a clinical strain background or in the presence of urine. Interestingly, the only study reporting gene expression by E. coli UTI isolates during biofilm growth in human urine revealed that several biofilm-related factors, including type 1 fimbriae, autotransporter protein antigen 43 (Ag43), and extracellular matrix components, were not upregulated in the urine biofilms (22). The lack of knowledge about bacterial gene expression on catheters derived from patients experiencing CAUTI makes it difficult to assess the clinical relevance of proposed E. coli biofilm factors.

The current study demonstrates the utility of combining data from a dynamic catheterized bladder model in vitro with in vivo expression analysis for understanding molecular factors relevant for CAUTI pathogenesis. The role of known E. coli virulence factors for UTI and for biofilm formation in simple in vitro biofilm models was evaluated in a dynamic catheterized bladder model. Our results support the conclusion that type 1 fimbriae are required for efficient catheter colonization of E. coli under physicochemical conditions closely mimicking the human infection. Expression analysis of bacterial cells from a clinical catheter specimen underlines the role of type 1 fimbriae for catheter colonization by E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, oligonucleotides, and media.

E. coli strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or agar containing 5 g NaCl per liter (23) at 37°C. Selective media contained antibiotics at the following concentrations: kanamycin (Km), 50 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol (Cm), 10 μg ml−1; ampicillin (Amp), 100 μg ml−1; and streptomycin (Sm), 100 μg ml−1.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Construction/characteristic(s) or sequence | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| MG1655 | ilvG, rfb-50, thi | 59 |

| MG1655Str | Smr; ilvG, rfb-50, thi | 60 |

| MG1655flhDC | MS426, flhDC deletion in MG1655 | 61 |

| MG1655flu | MS427, flu deletion in MG1655 | 61 |

| MG1655fim | MS428, fim operon deletion in MG1655 | 29 |

| CAUTI1-9 | E. coli isolates from catheterized of patients with CAUTI | This study |

| CAUTI5fim | CAUTI5 with TargeTron insertion in fimA, Kmr | This study |

| CFT073 | Uropathogenic E. coli | 62 |

| CFT073fim | CFT073 with TargeTron insertion in fimA, Kmr | This study |

| Plasmid | ||

| pACD4K-C | Cmr, TargeTron plasmid | Sigma Aldrich |

| pACD4K-Cfim | pACD4K-C with intron retargeted for insertion in fimA | This study |

| pAR1219 | Ampr, helper plasmid encoding T7 polymerase | Sigma Aldrich |

| pEpiFos5 | Cmr, fosmid cloning vector with partitioning system | Epicentre |

| pEpiFosfim | Cmr, pEpiFos5 with fim operon of E. coli MG1655 | This study |

| Oligonucleotide | ||

| fimA 10-11s EBS1d | CAGATTGTACAAATGTGGTGATAACAGATAAGTCACAGAACGTAACTTACCTTT CTTTGT | |

| fimA 10-11s EBS2 | TGAACGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTCACTTCCGATAGAGGAAAGTGTCT | |

| fimA 10-11s IBS | AAAAAAGCTTATAATTATCCTTAAAGTGCACAGAAGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTG | |

| fimIE_FW | AGTAATGCTGCTCGTTTTGC | |

| fimIE_RV | GACAGAGCCGACAGAACAAC | |

| op-K12-fim01 | TAAGCGGCCGCCATCAGGCTGAGC | |

| op-K12-fim02 | ATAGCGGCCGCCGGGATTATCAG |

Artificial urine was prepared and filter sterilized as described previously (24). Human urine was collected anonymously from 5 to 15 healthy volunteers (both men and women) who had no history of UTI prior to collection. The urine was pooled, sterilized through a filter cartridge (Sartobran P; 0.2 μm; Sartorius, United Kingdom), and kept at 4°C until use within the following 48 h. Pooled urine was routinely analyzed semiquantitatively using Combur10 Test UX (Roche) to avoid using urine with abnormal properties (pH, leukocytes, nitrite, urobilinogen, protein, hemoglobin, bilirubin, glucose, ketone, and specific gravity).

In vitro model of a catheterized bladder.

The dynamic catheterized bladder model originally developed in the David Stickler laboratory was performed as previously described (24), with minor modifications. In brief, two-compartment glass chambers were maintained at 37°C by circulation of water through the outer compartment. A size 14 sterile Foley all-silicone catheter (Bard, GA) was inserted into the inner compartment of the glass chambers, followed by inflation of the catheter retention balloon with 10 ml sterile water. In contrast to the original model used by Stickler and coworkers, the outer glass compartment was 5 cm longer than the inner compartment, ensuring temperature maintenance of the top 10 cm of the catheter. After connection of catheters to standard drainage bags, sterile urine (∼15 ml) was pumped (Watson-Marlow 205S) into the inner chambers to a level just below the eyeholes of the catheter tips.

For inoculation, 0.5 ml of bacterial overnight cultures grown in LB at 37°C and 250 rpm for 16 h was transferred to 20 ml of sterile urine (37°C) and incubated for 3 h at 37°C and 250 rpm. For inoculation of the catheterized bladder models, an appropriate aliquot of the preculture representing 5 ml of an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 (∼0.5 × 108 CFU) was added to the urine in the inner chambers. After 1 h, the urine supply was resumed for 72 h at a constant rate of 30 ml h−1.

For quantification of biofilm on catheters, the urine flow was stopped and a sample of the bladder (inner compartment) suspension was collected without mixing. The inserted catheters were carefully removed from the bladder and cut aseptically. If subject to analysis, the tip of the catheter (including the eyeholes) was transferred to 1 ml saline (0.9% NaCl solution). Following a rinse of the remaining catheter with 2 ml of saline to remove traces of bladder content, the retention balloon section was removed. The next 5-cm catheter section was transferred to 5 ml saline solution and served as the catheter sample.

Catheter samples and samples taken from the bladder and the tip of the catheter were sonicated for 5 min (Sonorex RK100H; Bandelin), vortexed for an additional 2 min, and serially diluted. Aliquots were plated on LB agar plates to determine CFU/ml bladder content and CFU/cm catheter. In cochallenge experiments, bacterial counts of E. coli MG1655Str and CFT073fim were additionally determined on appropriate selective plates and subtracted from the total CFU count to reveal relative fitness of the MG1655 mutants and CFT073, respectively.

Complementation of MG1655fim.

To confirm the effect of fim operon deletion in MG1655fim on catheter colonization in trans, the entire fim operon of MG1655, including the recombinase genes fimB and fimE (sequence positions 4538201 to 4548230; GenBank accession number U00096) was amplified with Phusion high-fidelity polymerase (Finnzymes) using primers op-K-12-fim01 and op-K-12-fim02. After digestion with the restriction enzyme NotI, the resulting fragment was inserted in the fosmid vector pEpiFos5 (Epicentre). Following introduction of the resulting plasmid pEpiFosfim into MG1655fim, mannose-sensitive agglutination of yeast cells (25) was restored to wild-type levels.

Construction and characterization of type 1 fimbrial mutations in clinical E. coli isolates.

Insertional gene disruption of fimA in CFT073 and CAUTI5 was achieved using a TargeTron gene knockout system (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, oligonucleotides for mutant design were created using the TargeTron design site (Sigma) and are listed in Table 1. PCR was used to retarget a group II intron encoded by pACD4K-C, resulting in pACD4K-Cfim. After introduction of pACD4K-Cfim into the target E. coli strain carrying helper plasmid pAR1219, induction of proteins required for intron insertion was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Insertion of the intron-containing kanamycin resistance cassette (∼1.9 kb) in sense orientation after position 10 of the fimA coding region in the resulting plasmid-free mutants was confirmed by an overlapping PCR strategy. All fimA knockout mutations abolished mannose-sensitive agglutination of yeast cells (25).

Growth rates of CFT073 and its isogenic mutant CFT073fim in artificial and pooled human urine under aerobic conditions were determined after inoculation of prewarmed urine to an initial OD600 of 0.001. The OD600 was measured over 8 h under rigorous shaking (220 rpm) at 37°C. Data points of the exponential growth phase were included for linear regression (lnOD600 versus t) if an R2 of >0.98 was achieved. To detect potential minor growth differences between CAUTI5 and CAUTI5fim in human urine, the wild-type and mutant strains were cocultivated in batch culture for 72 h under aerobic conditions (37°C, 200 rpm). For this purpose, cultures initially inoculated with an equal number of wild-type and mutant cells were diluted 1:100 in sterile human urine every 24 h. After 72 h, numbers of wild-type and mutant cells were determined by selective plating.

IE orientation assay.

Swimming and catheter-attached bacteria were collected from the in vitro model. To stabilize nucleic acids in these samples, 5 ml of bladder content was combined with 10 ml of RNAprotect bacteria reagent (Qiagen). The 5-cm Foley catheter segment underneath the retention ball was submerged in 5 ml RNAprotect bacterial reagent. Bacteria were separated from the catheter piece by sonication for 5 min (Sonorex RK100H; Bandelin) and vortexing for an additional 2 min. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 μl of deionized water. Quantification of orientation of the fim invertible element (IE) was performed as previously described (26). The same amount of the PCR products (50 to 100 ng) was subject to restriction digestion with 5 U SnaBI. Products were separated electrophoretically on 3% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. Band intensities of fragments representing ON and OFF switches, were quantified using a gel documentation and image analysis system (AlphaImager and AlphaEaseFC) after background subtraction.

Catheter samples from hospitalized patients were included if patient urine was positive for a monoculture of E. coli during routine microbiological analysis (>105 CFU/ml). After the routine catheter removal or replacement procedure, approved by the Ethical Review Board of Medical University of Graz, catheter tips were submerged in RNAprotect bacterial reagent within 5 min and frozen at −80°C. The E. coli isolates causing the positive urine culture were tested for type 1 fimbrial expression via a standard assay for mannose-sensitive agglutination of yeast cells using cells cultured on LB agar plates (25). IE orientation in the bacterial population was determined as described above. No patient identifier data were included.

Statistical analysis.

The majority of data sets generated during this study passed the test for normal distribution; thus, data are presented as mean values ± standard errors (SE) if not stated otherwise. Statistically significant differences, defined as a P value of <0.05, were determined using SIGMAPLOT software, version 12.0 (SyStat Software Inc.). Independent challenges and cochallenge experiments were routinely analyzed using paired t test. If a data set did not fulfill necessary criteria for a parametric test, the nonparametric Wilcoxon matched-pair test was applied.

RESULTS

An isogenic E. coli K-12 mutant in type 1 fimbriae but not flagella or antigen 43 is outcompeted by the wild-type strain during catheter colonization in vitro.

Various genetic studies have shown that type 1 fimbriae, flagella, and autotransporter protein Ag43 support biofilm formation of E. coli laboratory K-12 strains in static in vitro model systems using polystyrene, glass, or polyvinylchloride surfaces (27–29). To date, only the role of type 1 fimbriae was confirmed during static biofilm formation of clinical E. coli isolates (19) and during initial adhesion to silicone tubing irrigated with human urine for 24 h (30). To determine the relevance of these findings for the physicochemical conditions and time periods characteristic for CAUTI, we tested the ability of E. coli K-12 strains mutated in these potential virulence factors to colonize an in vitro catheterized bladder model in cochallenge competition assays.

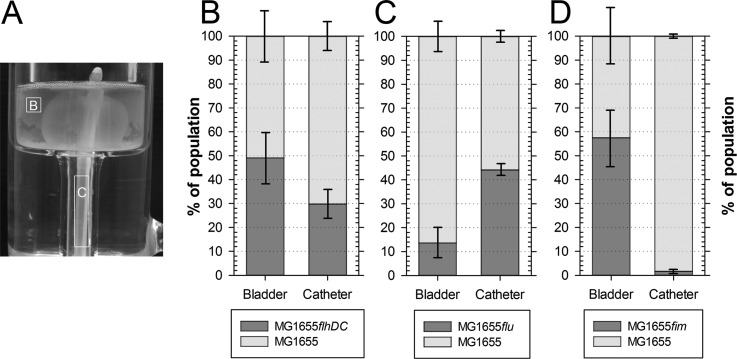

In brief, the utilized dynamic model for the catheterized bladder consists of a complete Foley catheter inserted in a temperature-controlled glass vessel representing the human bladder. Sterile urine is supplied into the bladder with a peristaltic pump throughout the experiment at a physiologically relevant rate. This system was used extensively to study catheter encrustation and blockage in vitro (31) and mirrors the physicochemical parameters of CAUTIs after bladder infection, including the flushing of urine through the catheter, albeit in the absence of a bladder mucosa. For each potential virulence factor, the catheterized bladder model was inoculated with a 1:1 ratio of wild-type to mutant cells. After 72 h of irrigation with artificial urine, the bacterial populations in the bladder suspension and on the internal all-silicone Foley catheter surface were analyzed to reveal the competitive fitness of the mutant strains (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

Absence of type 1 fimbriae but not flagella or Ag43 attenuates catheter colonization during CAUTI infection in vitro. (A) Following cochallenge of individual mutant derivatives of E. coli K-12 MG1655 and the wild-type strain MG1655Str in the dynamic catheterized bladder model for 72 h, the population distribution in the bladder suspension (compartment B) and on the biofilm formed on the internal surface of the all-silicone Foley catheter (compartment C) was quantified. (B to D) Stacked bars represent population structure in bladder and on catheter after competitive cochallenge of E. coli K-12 MG1655Str and a flagellar mutant derivative (MG1655flhDC) (B), an Ag43 mutant derivative (MG1655flu) (C), and a fim mutant derivative (MG1655fim) (D). Data are means ± SE (n = 3).

Lack of motility due to the absence of flagella did not affect survival in the bladder suspension, since equal numbers of mutant and wild-type strains were isolated (Fig. 1B). Although the nonmotile mutant tended to be less competitive during colonization or propagation on catheter surfaces (only 29.8% ± 5.9% of isolated cells were mutants), the difference from the wild-type strain population was not significant (P = 0.084). Surprisingly, the flu mutation resulted in reduced fitness in the bladder suspension (13.6% ± 5.2% mutant versus 86.4% ± 5.2% parental strain; P = 0.02), whereas catheter colonization did not lead to an altered population structure (P = 0.124). Although the mutant deficient in type 1 fimbriae was equally competitive in the urine present in the bladder, only 1.6% ± 0.7% of the cells harvested from the catheter biofilms were identified as the mutant strain (P = 0.03). These results suggested that of the three analyzed factors, type 1 fimbriae are most important for mature biofilm formation on catheters using experimental conditions mimicking the physicochemical conditions prevailing during CAUTI.

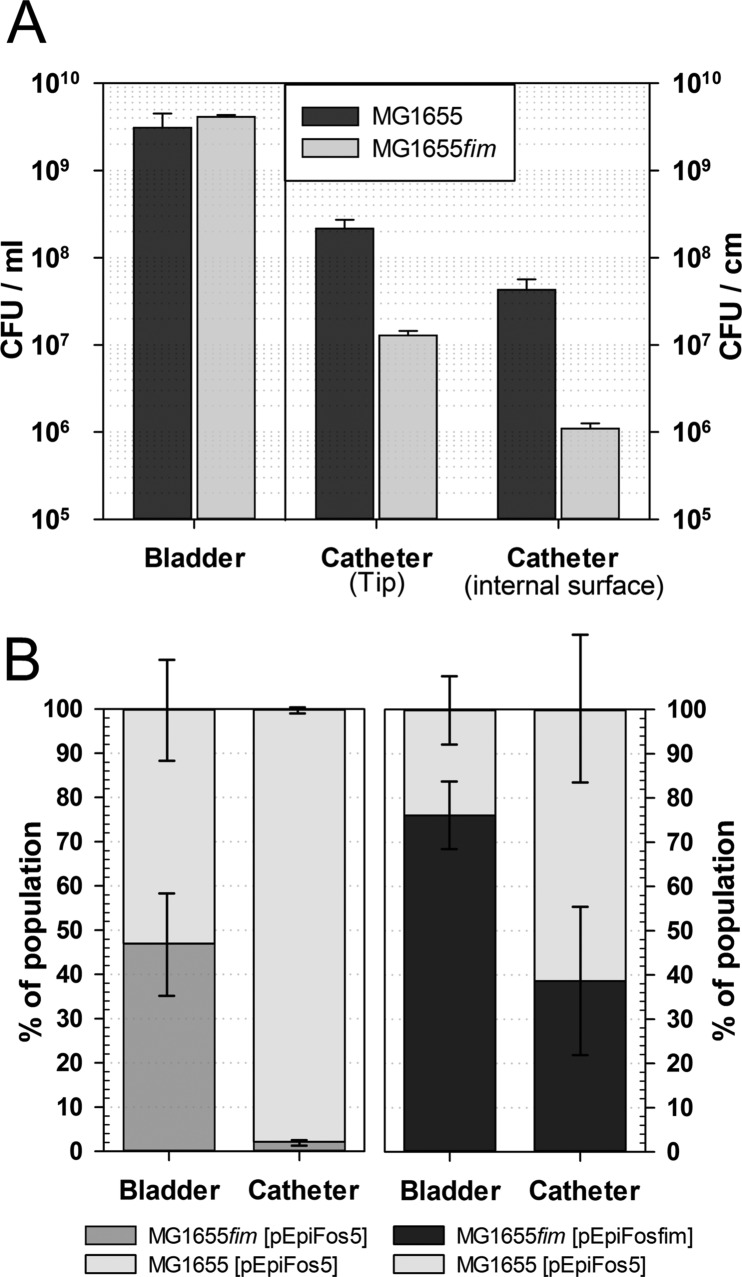

To confirm the attenuation of E. coli biofilm formation on the urethral catheter in the absence of type 1 fimbriae, wild-type MG1655 and the MG1655fim mutant carrying a deletion of the entire fim operon were inoculated in equal amounts in separate catheterized bladders in vitro. Quantification of colonization in the bladder suspension, on the catheter tip, and on the internal catheter surface was performed 96 h after inoculation (Fig. 2). In good agreement with the results of the cochallenge experiment, we found that bladder colonization was not affected by the mutation (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the numbers of mutant cells recovered from the catheter tip and the internal catheter surface were 17-fold and 39-fold reduced, respectively, compared to the model system that was inoculated with the parental strain (P < 0.01). A similar 20-fold attenuation of biofilm formation was observed for an E. coli fimH mutant after initial colonization on silicone tubing for 24 h (30).

FIG 2.

Absence of type 1 fimbriae attenuates catheter colonization and can be complemented in trans. (A) Bars represent colonization efficiencies of E. coli K-12 MG1655 and a mutant derivative, MG1655fim, harvested from different compartments of the model system 96 h after inoculation: bladder suspension (CFU/ml), catheter tip, and internal catheter surface (CFU/cm). Data are means ± SE (n = 3). The dynamic catheterized bladder model system was irrigated using artificial urine. (B) Stacked bars represent population structures in artificial bladder suspensions and on internal surfaces of Foley catheters after 72 h of competitive cochallenge of E. coli MG1655 carrying vector control pEpiFos5 and mutant derivative MG1655fim carrying vector control pEpiFos5 and type 1 fimbrial complementation vector pEpiFosfim, respectively, using pooled human urine. Data are means ± SE (n = 3).

To confirm that attenuated catheter colonization by MG1655fim can be complemented in trans and is not dependent on constituents not well represented in the artificial urine, a cochallenge experiment was also performed in pooled human urine using wild-type MG1655Str and mutant MG1655fim carrying a functional fim operon on fosmid vector pEpiFosfim (Fig. 2B). In agreement with our initial results, 72 h after coinoculation of MG1655Str and MG1655fim carrying the empty fosmid pEpiFos5, only 2.1% ± 0.8% of the cells harvested from the catheter biofilms were identified as the mutant strain (P = 0.04). In contrast, carriage of a complementing fim operon on pEpiFosfim in MG1655fim resulted in competiveness equal to that of wild-type MG1655Str[pEpiFos5] in the bladder urine (P = 0.14) and catheter surface populations (P = 0.35). We concluded that type 1 fimbriae are required for efficient colonization of a catheter by the laboratory E. coli strain under conditions prevailing in a catheterized bladder.

Type 1 fimbriae are required for efficient catheter colonization in vitro by uropathogenic E. coli.

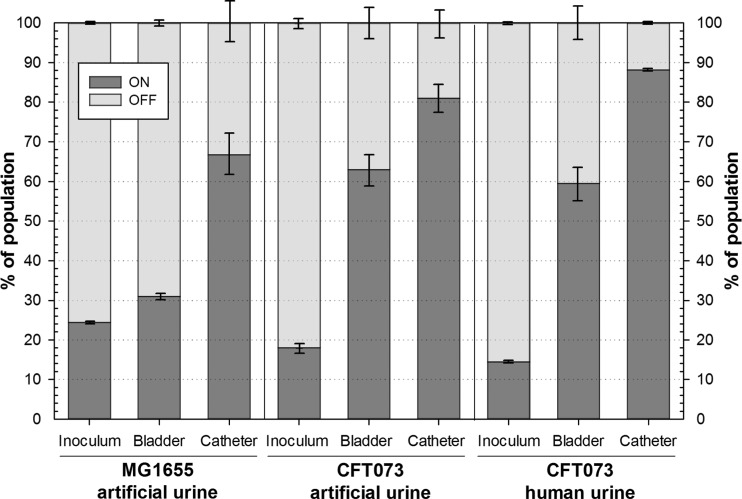

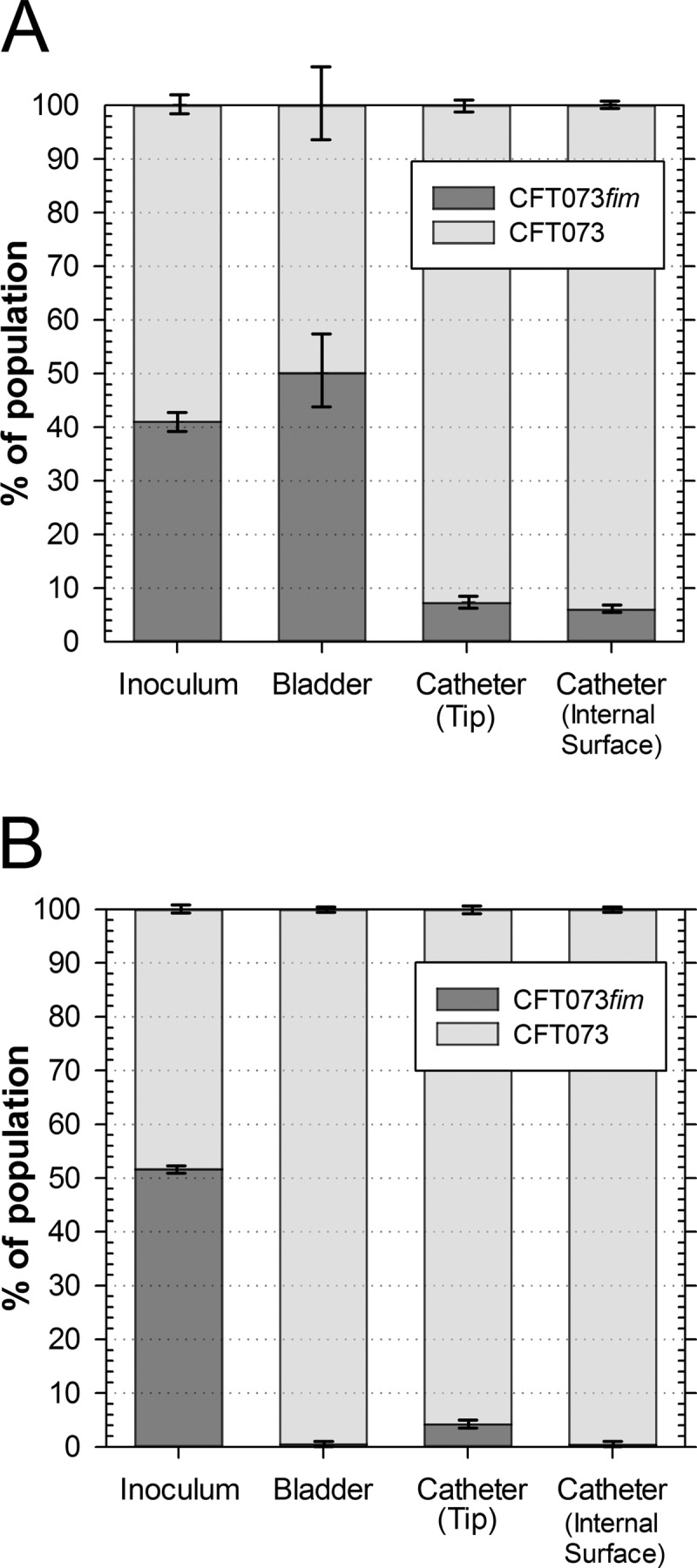

Since the laboratory E. coli strain K-12 that was used in our initial experiment may lack relevant virulence factors advantageous for efficient survival in the urinary tract, we extended our analysis with the well-characterized uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) strain CFT073. A knockout mutation in the fimA gene encoding the major fimbrial subunit was constructed. Absence of type 1 fimbria expression was confirmed in the resulting CFT073fim mutant by diminished type 1 fimbria-mediated mannose-sensitive agglutination of yeast cells (data not shown). Cochallenge competition experiments with the parental UPEC strain CFT073 using artificial urine confirmed the importance of type 1 fimbriae for catheter colonization (Fig. 3A). Whereas the initial 1:1 distribution of the mutant and wild-type strains in the bladder urine was unaffected after 72 h of competition (P > 0.05), only 7.2% ± 1.8% and 6.0% ± 1.1% of the cultivable population on the catheter tip and the internal catheter surface, respectively, were found to be mutant cells (P < 0.05).

FIG 3.

Type 1 fimbriae are important for dynamic catheterized bladder colonization in UPEC strain CFT073. Stacked bars represent population structures in inocula, in artificial bladder suspensions, and on the tip and internal surface of Foley catheters after competitive cochallenge of E. coli CFT073 and a fimA mutant derivative (CFT073fim) using artificial urine (A) and pooled human urine (B) for 72 h. Data are means ± SE (n = 3).

To confirm that this attenuation in catheter colonization by CFT073fim is not dependent on matrix proteins such as Tamm-Horsfall protein and constituents that are not well represented in the artificial urine, the cochallenge experiment was also performed in pooled human urine (Fig. 3B). Again, CFT073fim was significantly outcompeted by the parental strain in both populations on the Foley catheter, confirming our previous results; however, we also noted that only 0.5% ± 0.1% of the population in the bladder urine suspension was mutant cells (P < 0.01). Because growth rates of CFT073 in artificial urine (1.02 ± 0.04 h−1) and CFT073 and CFT073fim in human urine under aerobic conditions did not differ significantly (0.99 ± 0.02 h−1 versus 1.01 ± 0.01 h−1), we can exclude two unlikely explanations: (i) that reduced growth in human urine causes the loss of competiveness of CFT073fim, and (ii) that increased generation times in human urine create the requirement for type 1 fimbriae to avoid wash-out from the artificial bladder. Instead, we propose that the human urine constituents not present in the artificial urine create a different conditioning film on the glass surface of the bladder that leads to an increased requirement for type 1 fimbriae for bacteria to survive in the bladder urine. While the underlying mechanism remains undetermined, the results confirmed a role of type 1 fimbriae for efficient catheter colonization during CAUTI.

Expression of type 1 fimbriae is induced during catheter colonization in vitro.

The attenuated colonization of mutants deficient for type 1 fimbriae in the dynamic catheterized bladder model and on silicone tubing in vitro (30) suggested that type 1 fimbriae need to be expressed during colonization. The major regulatory mechanism allowing switching between fimbriated and nonfimbriated states is phase variation characterized by a reversible inversion of a 314-bp invertible element (IE) containing the promoter controlling transcription of the type 1 fimbria gene operon (32, 33). Accordingly, determination of the proportion of cells carrying the promoter fragment in the ON orientation is a good indication for type 1 fimbria expression in the population (26).

To determine this proportion in the populations colonizing the catheterized bladder model, samples taken from a model colonized for 72 h with E. coli MG1655 and CFT073 were conserved using a nucleic acid stabilizing reagent and then analyzed to determine IE orientation (Fig. 4). In the aerated batch culture used to inoculate the bladders, only 24% ± 1% of the MG1655 cells carried the IE in the ON orientation. This proportion was only modestly increased in the bladder population (31% ± 3%); however, 67% ± 11% of the cells in the catheter sample appeared to be in a fimbriated state. A similar distribution was observed for UPEC CFT073 in artificial urine and human urine (Fig. 4). Whereas the aerated culture revealed a modest proportion of cells in ON position ranging, from 14% to 18%, the majority of the bladder population appeared to be fimbriated (59% to 63%). In agreement with our hypothesis, cells from colonized catheters were found to have a significantly increased proportion of cells carrying the IE in the ON orientation with a maximum mean value in human urine of 88% ± 1%. We concluded that type 1 fimbriae not only are important for catheter colonization in vitro but also are expressed at high levels in catheter biofilms.

FIG 4.

Type 1 fimbrial expression is turned on upon catheterized bladder colonization. Stacked bars represent proportions of cells carrying the IE in orientations ON and OFF in populations used for inoculation and isolated from the dynamic catheterized bladder model, which was colonized in vitro with E. coli MG1655 and UPEC CFT073 using artificial and/or human urine for 72 h, as indicated. Data are means ± SE (n = 3).

E. coli strains isolated from catheterized patients predominantly exhibit type 1 fimbrial IE orientation in the ON position in vivo and require type 1 fimbriae for efficient catheter colonization in vitro.

Although the dynamic catheterized bladder model mimics physicochemical parameters prevalent during CAUTI, caution is still warranted about the relevance of these findings for the human urinary tract. Many in vitro and in vivo studies have indicated a crucial role for type 1 fimbriae during bladder colonization in the absence of a catheter; however, expression of type 1 fimbriae in bacteria isolated from the urine of women experiencing symptomatic urinary tract infection was low (26, 34).

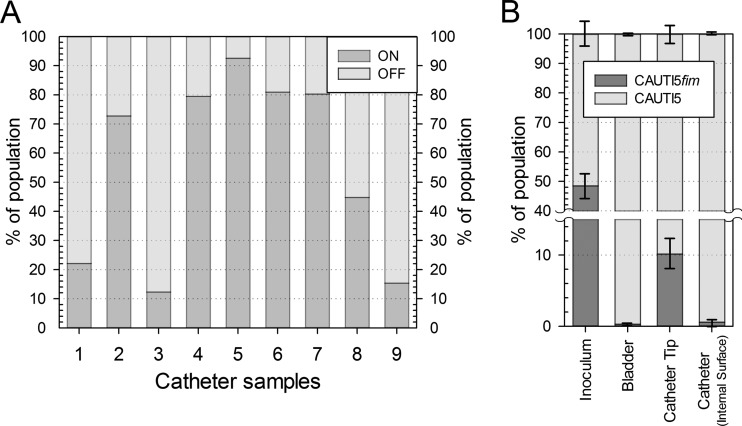

Therefore, we wanted to confirm our expression results from the in vitro model with clinical samples. Foley catheters removed from hospital patients that had given a positive urine sample for E. coli were conserved and analyzed for the IE orientation of colonizing bacteria (Fig. 5A). For nine samples analyzed, a median value of ON orientation was found to be 73% (first quartile, 20%; third quartile, 80%). For five of nine samples (56%), IE orientation indicated expression of type 1 fimbriae in more than 73% of the cells. However, the small data set suggests quite a variation in the percentage of fimbriated cells in the catheter samples obtained from different patients, possibly reflecting various catheter materials, different durations of infection at the time of catheter removal, or the presence of nonadherent cells in the catheter. Nevertheless, the clinical samples analyzed here support the conclusion that type 1 fimbriae are expressed in significant amounts during catheter colonization, possibly enabling better adherence in vivo.

FIG 5.

E. coli colonizing urethral catheters of patients experiencing CAUTI express type 1 fimbriae in vivo and require type 1 fimbriae for efficient catheter colonization in vitro. (A) Adherent bacteria from catheterized patients reveal a predominant orientation of IE in position ON. Catheter samples removed from patients experiencing CAUTI were analyzed for IE orientation. Stacked bars represent proportions of cells carrying ON and OFF orientations of IE in catheter populations isolated from clinical catheter samples 1 to 9. (B) E. coli isolate CAUTI5 requires type 1 fimbriae for efficient catheterized bladder colonization in vitro. Stacked bars represent population structures in inocula, in artificial bladder suspensions, and on the tip and internal surface of Foley catheters after competitive cochallenge of E. coli CAUTI5 and a fimA mutant derivative using pooled human urine for 72 h (B). Data are means ± SE (n = 3).

To assess the importance of type 1 fimbriae in an E. coli isolate from patients experiencing CAUTI, a fimA knockout mutation was created in a randomly chosen E. coli isolate originating from the clinical catheter samples (CAUTI5). Cochallenge experiments of mutant strains with corresponding wild-type strains were performed in pooled human urine. Again, the fim mutant strain was significantly outcompeted by the parental strain in populations in the bladder urine and on the Foley catheter, confirming our previous results (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5B). Control cochallenge experiments in aerated batch cultures performed over 72 h in human urine in parallel to the cochallenge experiments in the catheterized bladder did not result in significant outcompeting of the mutant strain (P > 0.05). Thus, fitness defects of the fim mutant in the catheterized bladder are not due to minor growth deficiencies. Together, this data set underscores the importance of type 1 fimbriae as key virulence factors in CAUTI.

DISCUSSION

In the presence of a Foley catheter in the human urinary tract, the normal defense mechanism maintained by frequent urine flushing and emptying of the bladder is undermined (35). Although the urine volume typically flowing through the bladder is high enough to wash out bacteria replicating with generation times observed in human urine in vitro, persistent bacteria may depend less on efficient attachment to the bladder. This resource, combined with the presence of an additional abiotic colonization surface that lacks the protective features of the bladder mucosa, support the proposal that development and persistence of CAUTI requires an arsenal of virulence factors distinct from those contributing to UTI (36). In this study, we applied a dynamic catheterized bladder model to investigate the contribution to catheter colonization of three factors encoded by most E. coli strains: flagella, Ag43, and type 1 fimbriae. We found that only the mutant deficient in assembly of type 1 fimbriae exhibited a competitive disadvantage against the parental strain during catheter colonization in vitro. Since catheter colonization was sampled 72 h after inoculation, when mature biofilms are already developed, we currently cannot differentiate a role of type 1 fimbriae during early attachment as previously indicated (30) or at a later stage of biofilm development. Despite reduced adherence to the catheter, all fim mutants still were able to colonize the catheters at up to 5 × 104 and 2 × 106 CFU/cm of catheter in cochallenge and separate inoculation experiments, respectively. Thus, additional factors are likely to be of importance for efficient biofilm formation on catheter surfaces irrigated with urine.

Ag43 does not appear to be important in this dynamic process, since an isogenic mutant was outcompeted in the bladder suspension but not in the population colonizing the silicone catheter. Since type 1 fimbriation is known to block Ag43-mediated aggregation (37), the strong prevalence of type 1 fimbria expression in catheter populations is likely to attenuate positive selection for Ag43-expressing cells. Thus, we cannot exclude that Ag43 or other autotransporter proteins associated with UPEC virulence (38–41) contribute to catheter colonization in strains unable to express type 1 fimbriae. In addition, our data suggest that flagellum-mediated motility or a proposed architectural function (42) is dispensable for CAUTI persistence once bacteria have colonized the bladder urine. The role of flagella during CAUTI pathogenicity is more likely to be relevant during onset of infection when bacteria ascend through the urethra to reach the bladder or up the urethers into the kidneys (43).

In support of our findings obtained using knockout mutants, type 1 fimbria expression, indicated by monitoring the orientation of the IE element, was found to be most prevalent in cell populations harvested from catheter biofilms. Two mechanisms might contribute to this observation: (i) superior catheter attachment of type 1 fimbriated cells and (ii) upregulation of type 1 fimbria expression in cells located in the catheter biofilms. The latter mechanism may reflect the requirement of type 1 fimbria expression to stick to the silicone surface and/or the surrounding cells but also may be a response to environmental changes. Indeed, oxygen depletion that is likely to occur in mature biofilms has been shown to select for increased type 1 fimbrial expression (44). Notably, our results are in contrast to a global transcriptome analysis of UPEC strains from patients experiencing asymptomatic UTI that revealed low type 1 fimbria expression in biofilms grown in the presence of human urine (22). Besides strain background, the use of a static petri dish biofilm model in the transcriptome study, in contrast to the dynamic catheterized bladder model in this study, is likely to account for these different observations.

The phase variation that occurs during bladder and kidney colonization during experimental murine UTI has been characterized extensively (26, 33, 45, 46); however, the expression level of type 1 fimbriae during human UTI and CAUTI remains equivocal. Studies based on immunostaining of E. coli in the urine of adults experiencing lower UTI suggested that a significant fraction of samples contained type 1 fimbriated cells ranging from 38% to 76% of the specimen (47–49), whereas the percentage of fimbriated cells in individual samples was not quantified. Other studies investigated fim operon transcription in urine specimens from women with cystitis. One study revealed that an average of only 4% of cells in urine specimens from 11 patients carried the type 1 fimbrial IE in the ON orientation (26). Whole-transcriptome analysis reported detectable levels of fimA and fimH transcripts in only two out of eight patients (34). In this study, we attempted to analyze IE orientation in catheter samples from human patients. A median level of ∼73% of cells over all nine samples was found to have switched on type 1 fimbrial expression based on promoter orientation. Thus, our study supports the conclusion that if E. coli strains infecting the lower urinary tract of catheterized patients are capable of expressing type 1 fimbriae, type 1 fimbriated cells are predominant in catheter biofilms. This is in accordance with an early observation suggesting that long-term catheterization selects for E. coli strains capable of type 1 fimbria-mediated mannose-sensitive hemagglutination (50). However, a more sophisticated comparative analysis of clinical samples from catheter and voided urine that takes into account duration of catheterization, catheter material, patient data, and history will be necessary to support this conclusion.

The confirmation of expression results from in vitro and in vivo samples and the generation of reproducible, normally distributed colonization data suggest that the dynamic catheterized bladder model utilized in this study proves useful for gaining a better understanding of catheter colonization during CAUTI. The different fates of type 1 fimbria mutant CFT073fim during cochallenge experiments with the parental strain in the bladder population depending on the use of artificial and pooled human urine may reflect differences in the nutrient concentration and the absence of organic matrix proteins in the chemically defined artificial urine (51). Tamm-Horsfall protein (THP), the most abundant protein in human urine, might contribute to this observation due to its well-characterized binding to type 1 fimbriated cells (52, 53) as well as adsorption to abiotic surfaces (54). Although THP concentration might be reduced in our experiments due to filter sterilization of the urine, we propose that UPEC cells expressing type 1 fimbriae are enriched in vitro in the bladder compared to fim counterparts by fimbria-mediated binding to THP present on the glass or catheter surface. Thus, for future applications using the dynamic catheterized bladder model, it appears suitable to perform initial experiments requiring large quantities of uniform urine utilizing artificial urine and to confirm important data sets using pooled human urine.

Taken together, the results of this study contribute compellingly to the growing body of evidence derived from various models that type 1 fimbriae are key virulence factors in UTI and CAUTI. This underscores the relevance of a recent study demonstrating the utility of small molecules interfering with type 1 fimbria-mediated adhesion to prevent infection in a murine model of CAUTI (30). However, UPEC strains express a diversity of fimbriae and adhesins (17, 55, 56); thus, we believe that other fimbrial types and proteins also contribute to catheter colonization by E. coli, particularly for strains unable to express type 1 fimbriae. The dynamic catheterized bladder model will prove useful for analysis of these factors in combination with experiments in in vivo CAUTI models and in parallel to analyses of clinical samples. Determining the overlap of virulence factors necessary for initiation and persistence in the noncatheterized and catheterized urinary tract will be important to ensure applicability of vaccines developed against UTI (57, 58) for CAUTI. In addition, identification of unique factors required for catheter colonization will accelerate development of efficient prevention or treatment options of CAUTI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David J. Stickler and Sheridan D. Morgan for discussions and technical support for setting up the catheterized bladder model in our laboratory and Mark A. Schembri and Carsten Struve for providing strains and plasmids. We thank anonymous volunteers (students and staff) from the Biomedical Science Institute, University of Applied Sciences, for providing human urine samples.

This work was supported by the NAWI Graz fund (to E.Z.) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under P13277-Gen (to E.Z.) and P21434-B18 (to A.R.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Shirtliff ME, Leid J. 2009. The role of biofilms in device-related infections. In Costerton JW. (ed), Springer series on biofilms, vol 3 Springer, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tambyah PA, Maki DG. 2000. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection is rarely symptomatic: a prospective study of 1,497 catheterized patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 160:678–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stickler DJ. 2008. Bacterial biofilms in patients with indwelling urinary catheters. Nat. Clin. Pract. Urol. 5:598–608. 10.1038/ncpuro1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBain AJ. 2009. In vitro biofilm models: an overview. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 69:99–132. 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)69004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tolker-Nielsen T, Sternberg C. 2005. Growing and analyzing biofilms in flow chambers. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 1:Unit 1B.2. 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b02s21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merritt JH, Kadouri DE, O'Toole GA. 2005. Growing and analyzing static biofilms. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 1:Unit 1B.1. 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b01s00 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coenye T, Nelis HJ. 2010. In vitro and in vivo model systems to study microbial biofilm formation. J. Microbiol. Methods 83:89–105. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjarnsholt T, Alhede M, Alhede M, Eickhardt-Sørensen SR, Moser C, Kühl M, Jensen PØ, Høiby N. 2013. The in vivo biofilm. Trends Microbiol. 21:466–474. 10.1016/j.tim.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart PS. 2012. Mini-review: convection around biofilms. Biofouling 28:187–198. 10.1080/08927014.2012.662641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reisner A, Krogfelt KA, Klein B, Zechner EL, Molin S. 2006. In vitro biofilm formation of commensal and pathogenic E. coli strains: impact of environmental and genetic factors. J. Bacteriol. 188:3572–3581. 10.1128/JB.188.10.3572-3581.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock V, Witsø IL, Klemm P. 2011. Biofilm formation as a function of adhesin, growth medium, substratum and strain type. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301:570–576. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guiton PS, Hung CS, Hancock LE, Caparon MG, Hultgren SJ. 2010. Enterococcal biofilm formation and virulence in an optimized murine model of foreign body-associated urinary tract infections. Infect. Immun. 78:4166–4175. 10.1128/IAI.00711-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy CN, Mortensen MS, Krogfelt KA, Clegg S. 2013. Role of Klebsiella pneumoniae type 1 and type 3 fimbriae in colonizing silicone tubes implanted into the bladder of mice as a model of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect. Immun. 81:3009–3017. 10.1128/IAI.00348-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mühldorfer I, Ziebuhr W, Hacker J. 2001. Escherichia coli in urinary tract infections, p 1515–1540 In Sussman M. (ed), Molecular medical microbiology, vol 2 Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macleod SM, Stickler DJ. 2007. Species interactions in mixed-community crystalline biofilms on urinary catheters. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:1549–1557. 10.1099/jmm.0.47395-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicolle LE. 2005. Catheter-related urinary tract infection. Drugs Aging 22:627–639. 10.2165/00002512-200522080-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobsen SM, Stickler DJ, Mobley HL, Shirtliff ME. 2008. Complicated catheter-associated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:26–59. 10.1128/CMR.00019-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beloin C, Roux A, Ghigo JM. 2008. Escherichia coli biofilms. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 322:249–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hadjifrangiskou M, Gu AP, Pinkner JS, Kostakioti M, Zhang EW, Greene SE, Hultgren SJ. 2012. Transposon mutagenesis identifies uropathogenic Escherichia coli biofilm factors. J. Bacteriol. 194:6195–6205. 10.1128/JB.01012-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood TK. 2009. Insights on Escherichia coli biofilm formation and inhibition from whole-transcriptome profiling. Environ. Microbiol. 11:1–15. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01768.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puttamreddy S, Cornick NA, Minion FC. 2010. Genome-wide transposon mutagenesis reveals a role for pO157 genes in biofilm development in Escherichia coli O157:H7 EDL933. Infect. Immun. 78:2377–2384. 10.1128/IAI.00156-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hancock V, Klemm P. 2007. Global gene expression profiling of asymptomatic bacteriuria Escherichia coli during biofilm growth in human urine. Infect. Immun. 75:966–976. 10.1128/IAI.01748-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertani G. 1951. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 62:293–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stickler DJ, Morris NS, Winters C. 1999. Simple physical model to study formation and physiology of biofilms on urethral catheters. Methods Enzymol. 310:494–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sokurenko EV, Courtney HS, Ohman DE, Klemm P, Hasty DL. 1994. FimH family of type 1 fimbrial adhesins: functional heterogeneity due to minor sequence variations among fimH genes. J. Bacteriol. 176:748–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim JK, Gunther NW, Zhao H, Johnson DE, Keay SK, Mobley HL. 1998. In vivo phase variation of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial genes in women with urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 66:3303–3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pratt LA, Kolter R. 1998. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli biofilm formation: roles of flagella, motility, chemotaxis and type I pili. Mol. Microbiol. 30:285–293. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beloin C, Michaelis K, Lindner K, Landini P, Hacker J, Ghigo JM, Dobrindt U. 2006. The transcriptional antiterminator RfaH represses biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:1316–1331. 10.1128/JB.188.4.1316-1331.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kjaergaard K, Schembri MA, Ramos C, Molin S, Klemm P. 2000. Antigen 43 facilitates formation of multispecies biofilms. Environ. Microbiol. 2:695–702. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guiton PS, Cusumano CK, Kline KA, Dodson KW, Han Z, Janetka JW, Henderson JP, Caparon MG, Hultgren SJ. 2012. Combinatorial small-molecule therapy prevents uropathogenic Escherichia coli catheter-associated urinary tract infections in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4738–4745. 10.1128/AAC.00447-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stickler DJ, Feneley RC. 2010. The encrustation and blockage of long-term indwelling bladder catheters: a way forward in prevention and control. Spinal Cord. 48:784–790. 10.1038/sc.2010.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abraham JM, Freitag CS, Clements JR, Eisenstein BI. 1985. An invertible element of DNA controls phase variation of type 1 fimbriae of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82:5724–5727. 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwan WR. 2011. Regulation of fim genes in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. World J. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1:17–25. 10.5495/wjcid.v1.i1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hagan EC, Lloyd AL, Rasko DA, Faerber GJ, Mobley HL. 2010. Escherichia coli global gene expression in urine from women with urinary tract infection. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001187. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feneley RCL, Kunin CM, Stickler DJ. 2012. An indwelling urinary catheter for the 21st century. BJU Int. 109:1746–1749. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benton J, Chawla J, Parry S, Stickler D. 1992. Virulence factors in Escherichia coli from urinary tract infections in patients with spinal injuries. J. Hosp. Infect. 22:117–127. 10.1016/0195-6701(92)90095-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasman H, Chakraborty T, Klemm P. 1999. Antigen-43-mediated autoaggregation of Escherichia coli is blocked by fimbriation. J. Bacteriol. 181:4834–4841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allsopp LP, Beloin C, Ulett GC, Valle J, Totsika M, Sherlock O, Ghigo J-M, Schembri MA. 2012. Molecular characterization of UpaB and UpaC, two new autotransporter proteins of uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073. Infect. Immun. 80:321–332. 10.1128/IAI.05322-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guyer DM, Radulovic S, Jones FE, Mobley HL. 2002. Sat, the secreted autotransporter toxin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli, is a vacuolating cytotoxin for bladder and kidney epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 70:4539–4546. 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4539-4546.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allsopp LP, Totsika M, Tree JJ, Ulett GC, Mabbett AN, Wells TJ, Kobe B, Beatson SA, Schembri MA. 2010. UpaH is a newly identified autotransporter protein that contributes to biofilm formation and bladder colonization by uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073. Infect. Immun. 78:1659–1669. 10.1128/IAI.01010-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valle J, Mabbett AN, Ulett GC, Toledo-Arana A, Wecker K, Totsika M, Schembri MA, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. 2008. UpaG, a new member of the trimeric autotransporter family of adhesins in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 190:4147–4161. 10.1128/JB.00122-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serra DO, Richter AM, Klauck G, Mika F, Hengge R. 2013. Microanatomy at cellular resolution and spatial order of physiological differentiation in a bacterial biofilm. mBio. 4:e00103–13. 10.1128/mBio.00103-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwan WR. 2008. Flagella allow uropathogenic Escherichia coli ascension into murine kidneys. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 298:441–447. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lane MC, Li X, Pearson MM, Simms AN, Mobley HL. 2009. Oxygen-limiting conditions enrich for fimbriate cells of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 191:1382–1392. 10.1128/JB.01550-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snyder JA, Haugen BJ, Buckles EL, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Donnenberg MS, Welch RA, Mobley HLT. 2004. Transcriptome of uropathogenic Escherichia coli during urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 72:6373–6381. 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6373-6381.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Struve C, Krogfelt KA. 1999. In vivo detection of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial expression and phase variation during experimental urinary tract infection. Microbiology 145:2683–2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pere A, Nowicki B, Saxen H, Siitonen A, Korbonen TK. 1987. Expression of P, type-I, and type-1C fimbriae of Escherichia coli in the urine of patients with acute urinary tract infection. J. Infect. Dis. 156:567–574. 10.1093/infdis/156.4.567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kisielius PV, Schwan WR, Amundsen SK, Duncan JL, Schaeffer AJ. 1989. In vivo expression and variation of Escherichia coli type 1 and P pili in the urine of adults with acute urinary tract infections. Infect. Immun. 57:1656–1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lichodziejewska M, Topley N, Steadman R, Mackenzie RK, Jones KV, Williams JD. 1989. Variable expression of P fimbriae in Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Lancet i:1414–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mobley HL, Chippendale GR, Tenney JH, Hull RA, Warren JW. 1987. Expression of type 1 fimbriae may be required for persistence of Escherichia coli in the catheterized urinary tract. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:2253–2257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffith DP, Musher DM, Itin C. 1976. Urease. The primary cause of infection-induced urinary stones. Investig. Urol. 13:346–350 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orskov I, Ferencz A, Orskov F. 1980. Tamm-Horsfall protein or uromucoid is the normal urinary slime that traps type 1 fimbriated Escherichia coli. Lancet i:887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pak J, Pu Y, Zhang ZT, Hasty DL, Wu XR. 2001. Tamm-Horsfall protein binds to type 1 fimbriated Escherichia coli and prevents E. coli from binding to uroplakin Ia and Ib receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9924–9930. 10.1074/jbc.M008610200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raffi HS, Bates JM, Flournoy DJ, Kumar S. 2012. Tamm-Horsfall protein facilitates catheter associated urinary tract infection. BMC Res. Notes 5:532. 10.1186/1756-0500-5-532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spurbeck RR, Stapleton AE, Johnson JR, Walk ST, Hooton TM, Mobley HLT. 2011. Fimbrial profiles predict virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains: contribution of Ygi and Yad fimbriae. Infect. Immun. 79:4753–4763. 10.1128/IAI.05621-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wurpel DJ, Beatson SA, Totsika M, Petty NK, Schembri MA. 2013. Chaperone-usher fimbriae of Escherichia coli. PLoS One 8:e52835. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sivick KE, Mobley HL. 2010. Waging war against uropathogenic Escherichia coli: winning back the urinary tract. Infect. Immun. 78:568–585. 10.1128/IAI.01000-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brumbaugh AR, Mobley HLT. 2012. Preventing urinary tract infection: progress toward an effective Escherichia coli vaccine. Expert Rev. Vaccines 11:663–676. 10.1586/erv.12.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blattner FR, Plunkett G, III, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453–1474. 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miranda RL, Conway T, Leatham MP, Chang DE, Norris WE, Allen JH, Stevenson SJ, Laux DC, Cohen PS. 2004. Glycolytic and gluconeogenic growth of Escherichia coli O157:H7 (EDL933) and E. coli K-12 (MG1655) in the mouse intestine. Infect. Immun. 72:1666–1676. 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1666-1676.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reisner A, Haagensen JA, Schembri MA, Zechner EL, Molin S. 2003. Development and maturation of Escherichia coli K-12 biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 48:933–946. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03490.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Welch RA, Burland V, Plunkett G, III, Redford P, Roesch P, Rasko D, Buckles EL, Liou SR, Boutin A, Hackett J, Stroud D, Mayhew GF, Rose DJ, Zhou S, Schwartz DC, Perna NT, Mobley HL, Donnenberg MS, Blattner FR. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:17020–17024. 10.1073/pnas.252529799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]