Abstract

The production of cellulose fibrils is involved in the attachment of Agrobacterium tumefaciens to its plant host. Consistent with previous studies, we reported recently that a putative diguanylate cyclase, celR, is required for synthesis of this polymer in A. tumefaciens. In this study, the effects of celR and other components of the regulatory pathway of cellulose production were explored. Mutational analysis of celR demonstrated that the cyclase requires the catalytic GGEEF motif, as well as the conserved aspartate residue of a CheY-like receiver domain, for stimulating cellulose production. Moreover, a site-directed mutation within the PilZ domain of CelA, the catalytic subunit of the cellulose synthase complex, greatly reduced cellulose production. In addition, deletion of divK, the first gene of the divK-celR operon, also reduced cellulose production. This requirement for divK was alleviated by expression of a constitutively active form of CelR, suggesting that DivK acts upstream of CelR activation. Based on bacterial two-hybrid assays, CelR homodimerizes but does not interact with DivK. The mutation in divK additionally affected cell morphology, and this effect was complementable by a wild-type copy of the gene, but not by the constitutively active allele of celR. These results support the hypothesis that CelR is a bona fide c-di-GMP synthase and that the nucleotide signal produced by this enzyme activates CelA via the PilZ domain. Our studies also suggest that the DivK/CelR signaling pathway in Agrobacterium regulates cellulose production independent of cell cycle checkpoint systems that are controlled by divK.

INTRODUCTION

The interaction of the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens with its host is dependent on attachment (1, 2), which requires the production of anchoring factors. One component of the attachment matrix produced by the bacterium is cellulose, a β1,4-linked glucose polymer. The cellulose fibrils serve to anchor the bacteria to each other and to stabilize the interaction of the bacteria to the plant cells (3). Mutants deficient in the production of cellulose bind less tightly to plant cell surfaces (4, 5), and in addition, they do not efficiently establish biofilms (6).

The production of cellulose by A. tumefaciens strain C58 is encoded by two closely linked operons, celABC and celDE, located on the linear chromosome (7–9). Two of the genes, celA and celB, encode the heterodimeric cellulose synthase complex (10). The CelD and CelE proteins likely are responsible for the synthesis of UDP-glucose, a process that involves a lipid-glucose intermediate (10). The CelA-CelB complex then catalyzes the addition of the activated glucose to the extending cellulose fiber (11, 12). Based on evidence in other bacteria, the cellulose fibrils are extruded into the extracellular milieu from the synthase complex, perhaps by an exporter encoded by CelC, imbedded within the membrane of the cells (13, 14).

Cellulose synthesis in A. tumefaciens resembles production of this polymer in the model bacterium Gluconoacetobacter xylinum (15). In this system, the synthase complex, encoded by bcsA and bcsB, responds to the secondary signal molecule cyclic diguanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) (16, 17), with the BcsA subunit recognizing the nucleotide via a PilZ domain, one of several known c-di-GMP-binding domains (18–20). The sequences of CelA and BcsA are strongly conserved, including the C-terminal PilZ domain. Consistent with this conserved signal-binding domain, Amikam and Benziman (21) reported that in cell extracts of A. tumefaciens, addition of c-di-GMP substantially increased the rate of cellulose synthesis. These observations strongly suggest that cellulose synthesis in A. tumefaciens is regulated in part by c-di-GMP.

In previous studies, we reported that production of cellulose in A. tumefaciens is stimulated by a putative diguanylate cyclase (DGC) we named CelR (22). Overexpression of celR resulted in increased production of the polymer, while deleting the gene greatly reduced the amount of cellulose extractable from the cells (22). These results suggest that celR is involved in activating synthesis of cellulose. The celR gene is part of the divK-celR operon, which is strongly conserved in many alphaproteobacteria (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (22). Interestingly, in Caulobacter crescentus, this operon, annotated as divK and pleD, controls events at the poles of the cell. PleD, the ortholog of CelR, is involved in regulating the formation of the holdfast stalk, while DivK localizes cell cycle regulators, including factors for activating PleD, to specific poles of the cell during division (23–27). The divK gene also controls polar localization during the cell cycle of Brucella abortus (28), and in Agrobacterium, divK functions in a phosphorelay cascade that regulates cell division (29). These observations suggest that the divK-celR (pleD) operon and its component genes may play different roles among the diverse species of the alphaproteobacteria.

While we have demonstrated that celR influences cellulose production in A. tumefaciens, the mechanism by which it does so is still unknown. Based on biochemical and mutational analyses, PleD of C. crescentus has diguanylate cyclase activity (25, 30, 31). However, there is limited evidence that CelR, while containing the conserved c-di-GMP synthesis motif, is a functional DGC (22, 29). There are several examples of proteins with GGDEF domains that do not exhibit c-di-GMP synthesis activity (reviewed in references 32 and 33). It is conceivable, then, that celR stimulates cellulose synthesis by some alternate mechanism.

In this study, we examined the effects of targeted mutations in both divK and celR on cellulose synthesis in A. tumefaciens. Our results indicate that CelR activity requires an intact GGEEF motif, as well as a conserved aspartate residue in the first of two CheY domains of the protein. In turn, a substitution mutation in a residue associated with c-di-GMP binding in the PilZ domain of CelA greatly reduces the amount of cellulose synthesized by the mutant. We also show that stimulation of cellulose biosynthesis by CelR is dependent on DivK. However, divK also influences cell division in A. tumefaciens, and this influence is independent of celR. Our results are consistent with the notion that divK continues to regulate cell division in A. tumefaciens, as in other alphaproteobacteria, while the divK-celR operon has diverged to also regulate cellulose production among members of the family Rhizobiaceae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains of Escherichia coli were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) (Invitrogen) agar plates with appropriate antibiotics at 37°C. Strains of Agrobacterium tumefaciens were grown on nutrient agar (NA) (Fisher) or on plates of AB minimal medium (34) supplemented with 0.2% mannitol (ABM) with appropriate antibiotics at 28°C. Cultures of E. coli were grown in LB broth with the required antibiotics at 37°C with shaking. Cultures of A. tumefaciens were grown in MG/L medium (35) with appropriate antibiotics at 28°C with shaking. Antibiotics used include ampicillin (100 μg/ml for E. coli), carbenicillin (50 μg/ml for A. tumefaciens), kanamycin (50 μg/ml for both E. coli and A. tumefaciens), gentamicin (50 μg/ml for E. coli and 25 μg/ml for A. tumefaciens), and tetracycline (10 μg/ml for both E. coli and A. tumefaciens). When necessary, Congo red (50 μg/ml), isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (400 mM) or 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (80 μg/ml) was added to plates for phenotype assessment.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this studya

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169(ϕ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 65 |

| S17-1/λpir | Pro− Res− Mod+ recA; integrated RP4-Tcr::Mu-Kan::Tn7 Mob+ Smr λ::pir | 66 |

| SU101 | lexA71::Tn5(Def) sulA211 Δ(lacIPOZYA)169/F′ lacIq lacZΔM15::Tn9; Cmr Kmr | 40 |

| SU202 | lexA71::Tn5(Def) sulA211 Δ(lacIPOZYA)169/F′ lacIq lacZΔM15::Tn9; Cmr Kmr | 40 |

| A. tumefaciens strains | ||

| NTL7 | A derivative of NTL4, ΔtetRS, with pTiC58 reintroduced | 67 |

| NTL7/Tn7-Km | NTL7 with Tn7-Km inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7/Tn7-prcelR | NTL7 with Tn7-Km-prcelR inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7Δcel | NTL7 with celC and celDE deleted; Tcr | 22 |

| NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ | NTL7 celA::lacZ; Kmr | This study |

| NTL7ΔcelR::Gm | NTL7 celR::Gmr | 22 |

| NTL7ΔcelA::lacZΔcelR::Gm | NTL7 celA::lacZ celR::Gm; Kmr Gmr | This study |

| NTL7ΔcelR::Gm/Tn7-Km | NTL7ΔcelR::Gm with Tn7-Km inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔcelR::Gm/Tn7-prcelR | NTL7ΔcelR::Gm with Tn7-Km-prcelR inserted at the glmS site | 22 |

| NTL7ΔcelR::Gm/Tn7-prcelRD53A | NTL7ΔcelR::Gm with Tn7-Km-prcelRD53A inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔcelR::Gm/Tn7-prcelRD53E | NTL7ΔcelR::Gm with Tn7-Km-prcelRD53E inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivK::Km | NTL7 divK::Kmr | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivK::Km/Tn7-prcelR | NTL7ΔdivK::Km with Tn7-Gm-prcelR inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivK::Km/Tn7-prdivK | NTL7ΔdivK::Km with Tn7-Gm-prdivK inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivK::Km/Tn7-prdivKcelR | NTL7ΔdivK::Km with Tn7-Gm-prdivKcelR inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR | NTL7 with divK and celR deleted | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prcelR | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm-prcelR inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivK | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm-prdivK inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKcelR | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm-prdivKcelR inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prcelRD53A | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm-prcelRD53A inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prcelRD53E | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm-prcelRD53E inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKD53AcelR | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm-prdivKD53AcelR inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKD53EcelR | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm-prdivKD53EcelR inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKcelRD53A | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm-prdivKcelRD53A inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKcelRD53E | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm-prdivKcelRD53E inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKD53AcelRD53A | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm- prdivKD53AcelRD53A inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKD53EcelRD53A | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm- prdivKD53EcelRD53A inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKD53AcelRD53E | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm- prdivKD53AcelRD53E inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKD53EcelRD53E | NTL7ΔdivKcelR with Tn7-Gm- prdivKD53EcelRD53E inserted at the glmS site | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | Cloning vector; Apr | Invitrogen |

| pUCcelR | celR gene cloned into pUC18 | 22 |

| pUCcelRE373A | pUCcelR with E373 altered to an alanine | This study |

| pUCcelRD53A | pUCcelR with D53 altered to an alanine | This study |

| pUCcelRD53E | pUCcelR with D53 altered to a glutamate | This study |

| pUCcelA | celA gene cloned into pUC18 | This study |

| pUCcelAS594A | pUCcelA with S594 altered to an alanine | This study |

| pUCprdivKcelR | pUC18 containing the divK-celR operon and 400 bp of the promoter region | This study |

| pUCprcelR | pUC18 containing celR and 400 bp of the promoter region | 22 |

| pUCprcelRE373A | pUCprcelR with E373 altered to an alanine | This study |

| pUCprcelRD53A | pUCprcelR with D53 altered to an alanine | This study |

| pUCprcelRD53E | pUCprcelR with D53 altered to a glutamate | This study |

| pUCprdivK | pUC18 containing divK and 400 bp of the promoter region | This study |

| pZLQ | pBBR1MCS-2 based expression vector; Kmr | 68 |

| pZLQcelR | celR gene from pUCcelR cloned into the NdeI/BamHI sites of pZLQ | 22 |

| pZLQcelRE373A | celR gene from pUCcelRE373A cloned into the NdeI/BamHI sites of pZLQ | This study |

| pZLQcelRD53A | celR gene from pUCcelRD53A cloned into the NdeI/BamHI sites of pZLQ | This study |

| pZLQcelRD53E | celR gene from pUCcelRD53E cloned into the NdeI/BamHI sites of pZLQ | This study |

| pUC18mini-Tn7t-Km | Tn7 carrier vector containing Km cassette; Apr Kmr | 69 |

| pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm | Tn7 carrier vector containing Gm cassette; Apr Gmr | 69 |

| pTNS2 | Tn7 helper plasmid encoding the TnsABC+D- specific transposition pathway; Apr | 69 |

| pUCTn7-Km-prcelR | prcelR fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18mini-Tn7t-Km | 22 |

| pUCTn7-Km-prcelRD53A | prcelRD53A fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18mini-Tn7t-Km | This study |

| pUCTn7-Km-prcelRD53E | prcelRD53E fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18mini-Tn7t-Km | This study |

| pUCTn7-Km-prcelRE373A | prcelRE373A fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18mini-Tn7t-Km | This study |

| pUCTn7-Gm-prcelR | prcelR fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm | This study |

| pUCTn7-Gm-prcelRD53A | prcelRD53A fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm | This study |

| pUCTn7-Gm-prcelRD53E | prcelRD53E fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm | This study |

| pUCTn7-prdivKcelR | prdivKcelR fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm | This study |

| pUCTn7-prdivKD53AcelR | prdivKcelR fragment in pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm with D53 of divK altered to an alanine | This study |

| pUCTn7-prdivKD53EcelR | prdivKcelR fragment in pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm with D53 of divK altered to a glutamate | This study |

| pUCTn7-prdivKcelRD53A | prdivKcelR fragment in pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm with D53 of celR altered to an alanine | This study |

| pUCTn7-prdivKcelRD53E | prdivKcelR fragment in pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm with D53 of celR altered to a glutamate | This study |

| pUCTn7-prdivKD53AcelRD53A | prdivKcelR fragment in pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm with D53 of divK and celR altered to an alanine | This study |

| pUCTn7-prdivKD53AcelRD53E | prdivKcelR fragment in pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm with D53 of divK altered to an alanine and with D53 of celR altered to a glutamate | This study |

| pUCTn7-prdivKD53EcelRD53A | prdivKcelR fragment in pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm with D53 of divK altered to a glutamate and with D53 of celR altered to an alanine | This study |

| pUCTn7-prdivKD53EcelRD53E | prdivKcelR fragment in pUC18mini-Tn7t-Gm with D53 of divK and celR altered to a glutamate | This study |

| pKK38ASH | Broad-host-range IncP cloning vector; tac promoter; Tcr | 70 |

| pKK38celR | celR gene cloned into pKK38ASH at the BamHI site | This study |

| pKK38celRD53E | celRD53E allele cloned into pKK38ASH at the BamHI site | This study |

| pRK415 | InP1α broad-host-range cloning vector; Tcr | 71 |

| pRKdivKregion | The divK gene and flanking DNA inserted into pRK415 | This study |

| pRKdivKcelRregion | The divK-celR operon and flanking DNA inserted into pRK415 | This study |

| pRKdivKkan | Allellic replacement of divK with a kanamycin cassette on pRKdivKregion | This study |

| pRKdivKcelRkan | Allellic replacement of the divK-celR operon with a kanamycin cassette on pRKdivKcelRregion | This study |

| pRKdivKcelRdel | pRKdivKcelRkan with kanamycin cassette removed by flp recombinase | This study |

| pWM91 | λpir-dependent cloning vector; Apr Sucs | 72 |

| pWMdivKkan | divKkan fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pWM91 | This study |

| pWMdivKcelRdel | divKcelRdel fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pWM91 | This study |

| pWMcelRdel | celRdel fragment cloned into theBamHI site of pWM91 | 22 |

| pSRK-Gm | Broad-host-range expression vector; ara promoter; Gmr | 73 |

| pSRKcelA | celA inserted at the NdeI/BamHI sites of pSRK-Gm | This study |

| pSRKcelAS594A | S594A allele of celA cloned into pSRK-Gm at the NdeI/BamHI sites | This study |

| pKD46 | Lambda Red recombinase helper plasmid; Apr | 38 |

| pKD4 | Template plasmid of kanamycin cassette for chromosomal exchange; Apr Kmr | 38 |

| pCP20 | Temperature-sensitive replicon containing the FLP recombinase; Apr Cmr | 74 |

| pSR658 | Expression plasmid for LexA dimerization system; Tcr | 39 |

| pSR659 | Expression plasmid for LexA dimerization system; Apr | 39 |

| pMS604 | Expression plasmid carrying a LexA-WT-Fos fusion positive control for dimerization; Tcr | 40 |

| pDP804 | Expression plasmid carrying a LexA-Jun fusion positive control for dimerization; Apr | 40 |

| pSR659celR | pSR659 with celR cloned at the BamHI and KpnI sites | This study |

| pSR659celRD53A | pSR659 with celRD53A cloned at the BamHI and KpnI sites | This study |

| pSR659celRD53E | pSR659 with celRD53E cloned at the BamHI and KpnI sites | This study |

| pSR658divK | pSR658 with divK cloned at the XhoI and KpnI sites | This study |

| pSR658divKD53A | pSR658 with divKD53A cloned at the XhoI and KpnI sites | This study |

| pSR658divKD53E | pSR658 with divKD53E cloned at the XhoI and KpnI sites | This study |

Abbreviations: Apr, resistance to ampicillin and carbenicillin; Cmr, resistance to chloramphicol; Gmr, resistance to gentamicin; Kmr, resistance to kanamycin; Smr, resistance to streptomycin; Sucs, sensitivity to sucrose; Tcr, resistance to tetracycline.

Strain construction.

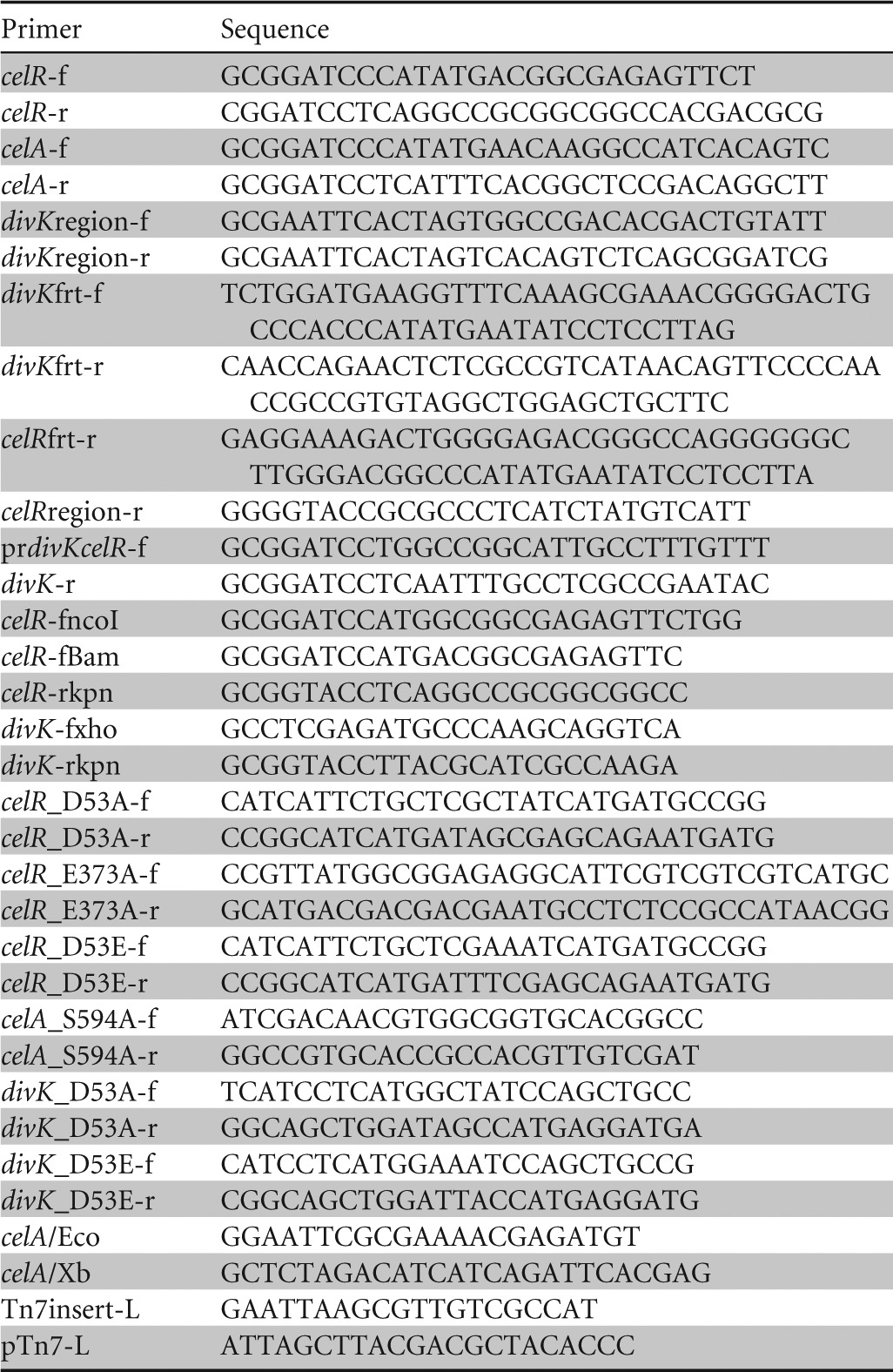

Primers used for PCR amplification are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used

(i) Construction of overexpression strains.

Genomic DNA was prepared from an overnight culture of A. tumefaciens NTL7 as described previously (36). To create the overexpression plasmid pKK38celR, the celR gene was amplified by PCR using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) and the primers celR-fnco and celR-r. The amplicon was digested with BamHI and ligated into BamHI-digested pUC18. The resulting ligation products were introduced into E. coli DH5α by CaCl2 transformation with selection on LB plates containing ampicillin. The plasmids were purified, and the resulting fragment was ligated into NcoI- and BamHI-digested pKK38ASH (Table 1) and transformed into strain DH5α. After selecting for tetracycline resistance, the plasmid was isolated and analyzed, and the correct construct was electroporated into the appropriate strains of A. tumefaciens. To express celA from a controlled promoter, the gene was amplified by PCR using Pfu polymerase and the primers celA-f and celA-r. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and ligated into BamHI-digested pUC18, and the resulting ligation products were transformed into strain DH5α. Colonies resistant to ampicillin were selected, and the plasmids were purified and digested with NdeI and BamHI. The resulting fragment of celA was ligated into the expression vector pSRK-Gm (Table 1) and transformed into DH5α. After selection for gentamicin resistance, the plasmid was isolated and analyzed, and the correct construct was electroporated into the appropriate strains of A. tumefaciens.

(ii) Production of Tn7 insertion vectors.

A 400-bp segment containing the promoter region of the divK-celR operon along with additional DNA encoding either divK or divK-celR was amplified using Pfu polymerase and the primers prdivKcelR-f and divK-r or primers prdivKcelR-f and celR-r. The amplicons were digested and cloned into BamHI-digested pUC18. The resulting ligation products were transformed into E. coli DH5α, transformants were isolated on LB plates containing ampicillin, and the recombinant plasmids were purified and confirmed by sequence analysis. The correct clones were digested with BamHI, and the fragments were ligated into pUC18-miniTn7t-Gm to form pUCTn7-prdivK and pUCTn7-prdivKcelR. The resulting plasmids were transformed into strain DH5α, selected for resistance to ampicillin and gentamicin, purified, and tested for the appropriate insertion by restriction digest analysis.

(iii) Site-directed mutagenesis.

The target fragments cloned into either pUC18, pUC-miniTn7t-Gm/Km or pSRK-Gm were amplified by PCR using Pfu polymerase with primers containing point mutations at the target residue (Table 2). The resulting amplified plasmids were digested with DpnI to remove the original template DNA, and the remaining plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α. After selection for resistance to the appropriate antibiotic, the plasmids were isolated, and the mutations were confirmed by sequence analysis. The altered plasmids were introduced into the appropriate strains by electroporation or by Tn7 insertion as described below. Fragments containing the correct mutation on pUC18 were recovered by digestion with the appropriate restriction enzymes and then ligation into either pZLQ (Table 1) or pKK38ASH.

(iv) Disruption of the chromosomal celA gene.

A nonpolar deletion of celA (atu3309) was constructed as follows. A 500-bp internal fragment of celA was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of A. tumefaciens NTL7 using Pfu DNA polymerase and primers celA/Eco and celA/Xb. The resulting amplicon was digested with EcoRI and XbaI and cloned between the corresponding sites on pVIK112 (37). The resulting ligation products were transformed into E. coli S17-1/λpir with selection for resistance to kanamycin. The resulting plasmid, pVIKcelA, was identified and transformed into strain NTL7 by electroporation. NTL7 carrying the disruption of celA resulting from a single-crossover event was selected by plating on media containing the appropriate antibiotics. Insertional disruption of celA was verified by PCR using additional primers located further upstream and downstream from the original fragments. The resulting mutant creates a celA::lacZ transcriptional fusion.

(v) Deleting celR by allelic exchange in the celA mutant.

The celR gene was deleted from A. tumefaciens NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ as previously described by Barnhart et al. (22).

(vi) Indel mutation of divK.

The divK gene was replaced with a kanamycin resistance cassette using a protocol modified from that of Datsenko and Wanner (38). Briefly, a set of primers, divKfrt-f (frt stands for FLP recombination target) and divKfrt-r was used to amplify the kanamycin cassette from pKD4 (Table 1) by PCR, and the product was treated with DpnI to blunt the ends. Additionally, a 3.9-kb fragment containing divK was amplified from A. tumefaciens NTL7 genomic DNA using the primers divKregion-f and divKregion-r. The fragment was digested with KpnI and cloned into pRK415 (Table 1), creating the construct pRKdivKregion. The construct was introduced into E. coli DH5α by CaCl2 transformation, and the plasmid was purified and confirmed by restriction analysis and sequencing. The PCR-generated kanamycin fragment was electroporated into an E. coli strain harboring both the red recombinase plasmid pKD46 (Table 1) and the pRKdivKregion plasmid, transformants were selected for resistance to kanamycin, and plasmids were purified and examined for replacement of divK on pRK415 by restriction analysis and PCR. The correct plasmids containing the replaced gene were digested with KpnI, the modified divK gene was cloned into the pir-dependent vector pWM91 (Table 1), producing the construct pWMdivKkan, and this plasmid was transformed into E. coli S17-1/λpir. Successful constructs were selected for resistance to ampicillin and kanamycin, and a verified plasmid was electroporated into A. tumefaciens. Initial transformants were selected for resistance to kanamycin and sucrose, followed by screening for sensitivity to carbenicillin. Potential mutants were confirmed using PCR and Southern analysis.

(vii) Allelic exchange of divK-celR.

The divK-celR operon was deleted using a different modification to the protocol from Datsenko and Wanner (38). A set of primers, divKfrt-f and celRfrt-r, were used to amplify the kanamycin cassette from pKD4 by PCR, and the product was treated with DpnI to blunt the ends. Additionally, a 4.2-kb fragment containing divK and celR was amplified from A. tumefaciens NTL7 genomic DNA using the primers divKregion-f and celRregion-r. The fragment was digested with KpnI and cloned into pRK415, creating the construct pRKdivKcelRregion. The construct was introduced into E. coli DH5α by CaCl2 transformation, and the plasmid was purified and verified by restriction digestion and sequencing. The fragment containing the kanamycin cassette was electroporated into an E. coli strain harboring both the red recombinase plasmid pKD46 and pRKdivKcelRregion, transformants were selected for resistance to kanamycin, and plasmids were purified and examined for replacement of the operon with the kanamycin cassette by restriction digestion and PCR. The correct plasmid containing the replaced operon, renamed pRKdivKcelRkan, was electroporated into an E. coli strain containing the plasmid pCP20, which expresses the flp recombinase gene. A construct in which the kanamycin cassette was deleted was identified by screening for resistance to tetracycline but sensitivity to kanamycin, and the plasmids were purified and examined for loss of the kanamycin cassette by restriction digestion. The correct plasmids were digested with KpnI, the modified region was cloned into pWM91, producing the construct pWMdivKcelRdel, and this plasmid was transformed into E. coli S17-1/λpir. Successful constructs were selected for resistance to ampicillin, and a verified plasmid was electroporated into A. tumefaciens. Initial transformants were selected for resistance to ampicillin for single recombination events, followed by growth in MG/L medium and screening for resistance to sucrose and sensitivity to carbenicillin. Potential marker exchange mutants were confirmed using PCR and Southern analysis.

(viii) Complementation of strains NTL7ΔcelR::Gm, NTL7ΔdivK::Km, and NTL7ΔdivKcelR.

To complement disruptions of divK and celR, appropriate Tn7 constructs, as well as the transposase plasmid pTNS2 (Table 1), were electroporated into the target mutant at a 1:2 ratio of Tn7 vector to pTNS2. The transformed cells were selected for resistance to gentamicin, and mini-Tn7 integrants were confirmed by PCR analysis using the primers Tn7insert-L and either pTn7-L, divK-r, or celR-r.

(ix) Two-hybrid constructs.

Both divK and celR genes were amplified from genomic DNA of A. tumefaciens strain NTL7 using Pfu polymerase and primers specific for insertion into two-hybrid expression vectors. The appropriate alleles of divK and celR were amplified from their recombinant plasmids using Pfu polymerase and the above primers. Fragments of divK were digested with XhoI and KpnI, while fragments of celR were digested with BamHI and KpnI. The fragment encoding divK was ligated into pSR658, transformed into E. coli DH5α, and selected for on medium containing tetracycline. The fragment encoding celR was ligated into pSR659, transformed into strain DH5α, and selected for on medium containing ampicillin. The plasmids were recovered, purified, and examined for the correct insertion by restriction digestion and sequencing. Plasmids containing the correct insert were transformed into either E. coli strain SU101 or SU202 and were selected for resistance to kanamycin and either tetracycline or ampicillin.

E. coli two-hybrid assays.

Bacterial two-hybrid assays were performed as described previously (39). E. coli strain SU101 containing plasmids with alleles of celR-lexA or strain SU202 containing plasmids with alleles of divK and celR fused to the DNA-binding fragment of lexA were plated on LB medium containing the appropriate antibiotics, IPTG, and X-Gal. The plates were incubated at 28°C for 3 days to determine whether the lacZ gene of the test strain was repressed. Interactions between fusion proteins yield light blue colonies due to repression of lacZ driven by a LexA-regulated promoter (39). All experiments were repeated at least three times, with negative controls of the parent strains harboring the empty vector pSR658 or pSR659 and the parent strains harboring the positive-control plasmid pMS604 or pDP804 (40), each containing full-length lexA.

Cellulose assays.

Cellulose was quantified after extraction using the protocol of Updegraff (41) as modified by Barnhart et al. (22). The amount of anthrone-reactive material extractable from a sample was standardized to the number of cells as determined by measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD600). cel mutants of A. tumefaciens strain NTL7 still produce anthrone-positive material, probably curdlan (22). Because of this, the average amount of cellulose extractable per 109 cells was then normalized by subtracting the amount of anthrone-positive material extracted from either A. tumefaciens NTL7Δcel or NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ, depending on the experiment, all as we described previously (22). Statistical analysis was performed using the Student t test using a one-sided distribution model.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase activity was quantified using a microtiter assay as described by Slauch and Silhavy (42). Cells grown overnight at 28°C in MG/L medium with appropriate antibiotics were subcultured into 2 ml of ABM medium, grown for 24 h to mid-exponential phase, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in 1.5 ml of Z-buffer, pH 7.1 (42). Volumes of 250 μl of each suspension were removed for turbidity measurements at 600 nm. Fifteen microliters of 1% SDS and 30 μl of chloroform was added to the remaining volumes, the samples were vortexed for 10 s and incubated for 15 min at room temperature, and 60-μl volumes of the lysates were distributed into polystyrene microtiter wells (Corning). The final volume in each well was adjusted to 200 μl with Z-buffer. The reaction was initiated by adding 50 μl of o-nitrophenyl-3-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) (10 mg/ml) in Z-buffer without added 3-mercaptoethanol, and the absorbance at 420 nm was monitored in a Cambridge Biotechnology model 700 microplate reader. Readings were taken at 3-min intervals for 24 min. β-Galactosidase activity was calculated as described previously (42). Each strain was assayed nine times, and the reaction rates were averaged and statistically analyzed using the Student t test with a one-sided distribution model.

Microscopy.

Cells were grown in MG/L medium with appropriate antibiotics overnight at 28°C with shaking. Cells from each culture grown to the same OD600 were examined by phase-contrast microscopy using an Olympus BH-2 research microscope (Olympus) with an Olympus Camedia digital camera (Olympus). Two image fields were recorded for each sample, and the total number of cells and the number of malformed cells were counted in each field. The percentage of malformed cells was calculated from two repetitions (four fields total), with statistical analysis performed using the Student t test with a one-sided distribution model.

RESULTS

Alteration of key residues affects the influence of CelR on cellulose production.

Previously, we showed that celR is required to stimulate cellulose biosynthesis (22). Bioinformatic analysis of this protein identified two N-terminal CheY-like receiver domains, the first containing a conserved aspartate residue, as well as a C-terminal catalytic GGEEF motif associated with synthesis of c-di-GMP (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Proteins with CheY domains often transition between activated and inactive forms based on the phosphorylation state of a conserved aspartate residue (25, 43, 44). Given its domain structure, these observations suggest that CelR is a c-di-GMP synthase and that its activity is modulated by modification of the Asp residue in the CheY domain.

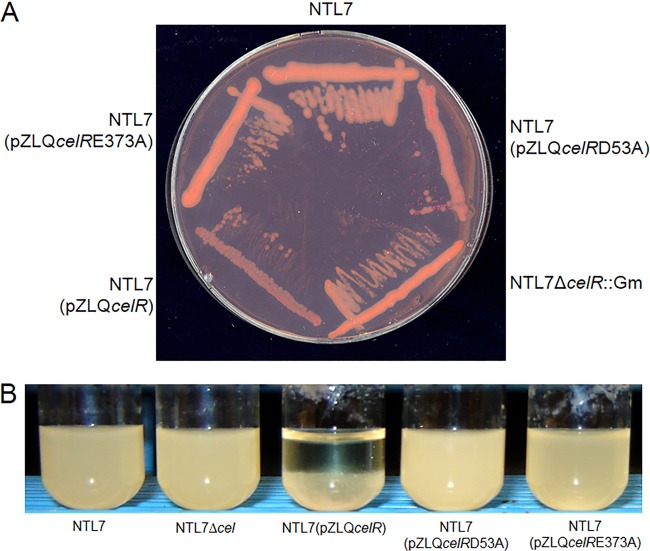

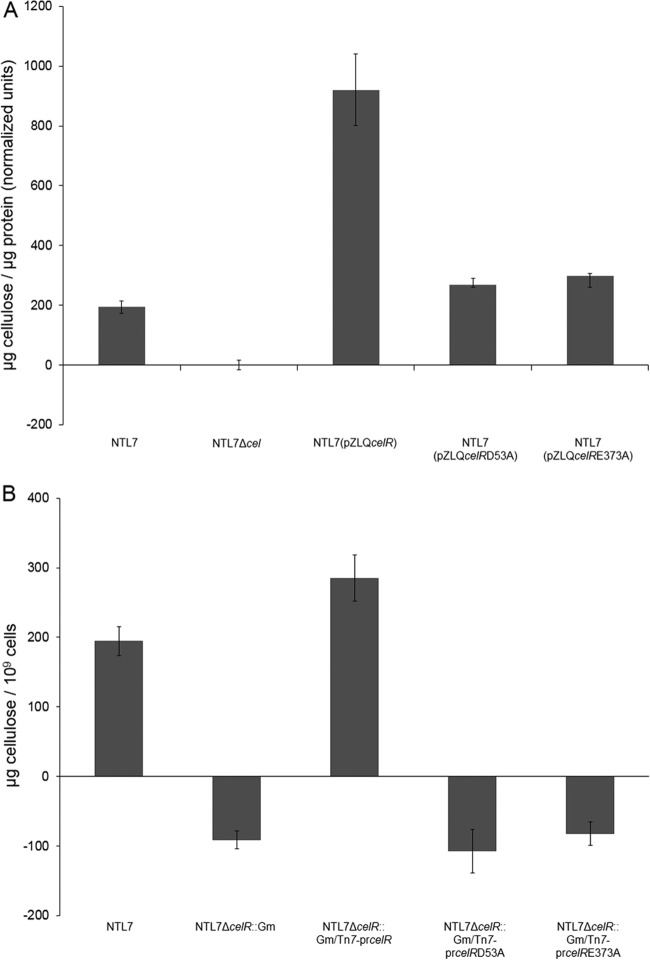

In a set of preliminary experiments, we overexpressed celR mutated at Asp53 in the CheY domain (celRD53A) or at a key residue of the enzymatic GGEEF motif (celRE373A) in wild-type strain NTL7. We assessed the effects of these mutations on cellulose production by colony color on Congo red plates (45) and by growth properties in liquid media. As we described previously (22), compared to the parent, overexpressing wild-type celR resulted in increased Congo red binding (Fig. 1A) and also pronounced aggregation in liquid media (Fig. 1B). A. tumefaciens NTL7 overexpressing either celRD53A or celRE373A exhibited little change in Congo red binding (Fig. 1A) and showed virtually no observable aggregation during growth in liquid media (Fig. 1B). In quantitative assays, strain NTL7 overexpressing celR produced a significantly higher level of extractable cellulose than that produced by the parent strain (Fig. 2A). In contrast, overexpressing either celRD53A or celRE373A had no significant effect on the amount of the polymer produced (Fig. 2A). These results suggest that to stimulate cellulose synthesis, CelR requires an intact GGEEF motif and the conserved aspartate residue in the CheY domain.

FIG 1.

Overexpressing mutant alleles of celR does not induce Congo red binding and aggregation on solid and liquid media. (A and B) Strain NTL7 and strains constructed from NTL7 expressing genes coding for altered alleles of celR were grown for 2 days at 28°C on ABM plates containing Congo red (A) and in MG/L medium (B), with shaking. Both media contained the appropriate antibiotics.

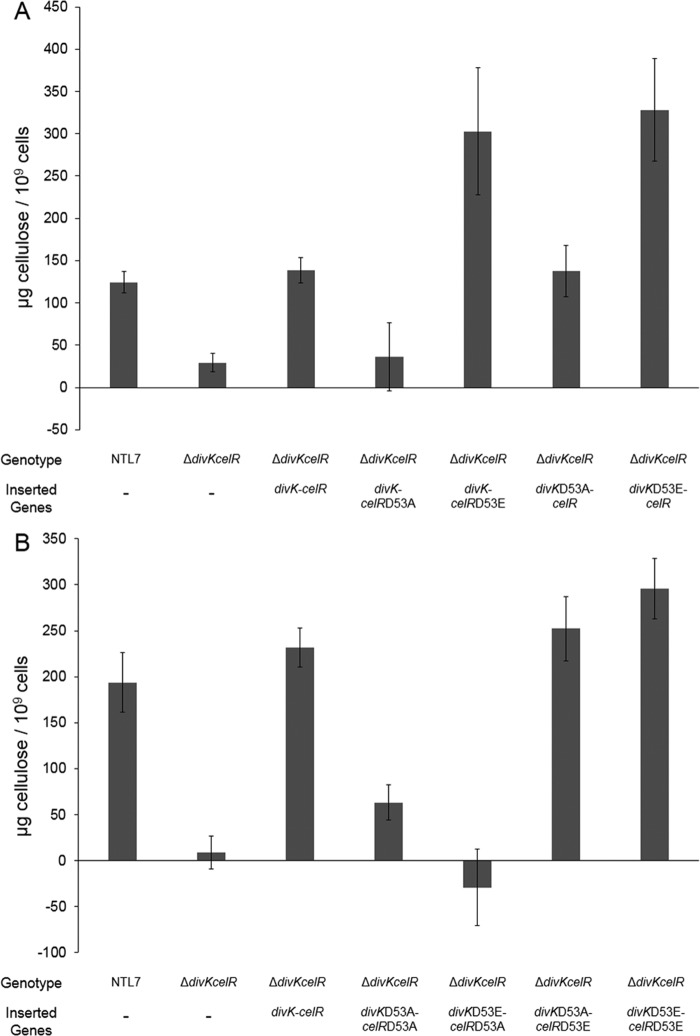

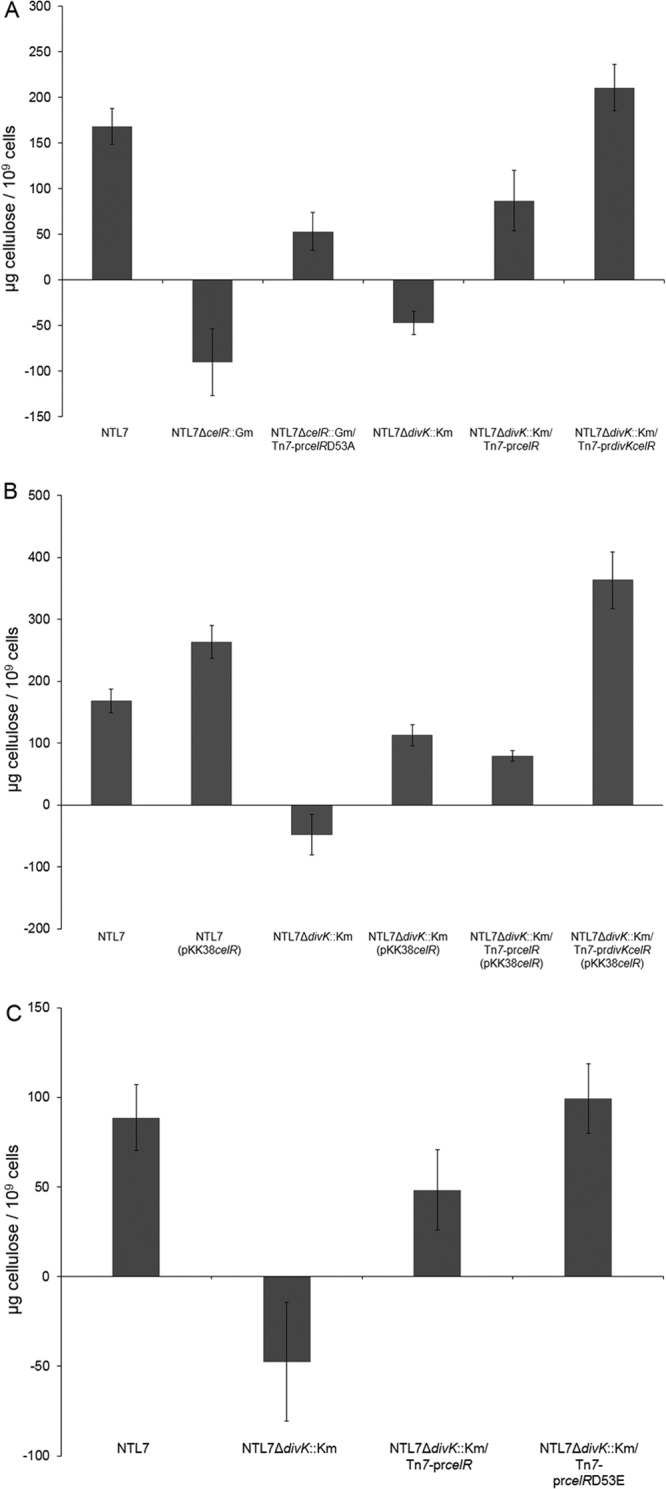

FIG 2.

Mutant alleles of celR do not stimulate production of cellulose. (A and B) Strains NTL7, NTL7Δcel, NTL7ΔcelR:Gm, and constructed strains overexpressing alleles of celR (A) or expressing alleles introduced by Tn7 insertion (B) were grown in MG/L medium with the appropriate antibiotics for 2 days at 28°C with shaking. The cells were harvested and assessed for production of anthrone-reacting material as described in Materials and Methods. The values are averages of four samples for each strain, and the error bars depict standard errors of the experiments.

CelR regulates cellulose biosynthesis through its activation and synthesis of c-di-GMP.

While overexpressing the D53A and E373A mutants of CelR has no effect on phenotypes associated with cellulose synthesis, these results do not establish the roles of these residues in stimulating production of the polymer. We therefore tested celRD53A and celRE373A for their ability to complement the indel mutant of celR, strain NTL7ΔcelR::Gm. As previously described (22), the ΔcelR mutant does not produce cellulose compared to wild-type NTL7 (Fig. 2B). Expressing wild-type celR from its native promoter in the mutant restored cellulose production to wild-type levels (Fig. 2B). Complementing the indel mutant with either celRD53A or celRE373A failed to restore cellulose synthesis compared to the uncomplemented mutant (Fig. 2B). Taken together, the data indicate that CelR requires both the conserved aspartate in the CheY domain and the conserved glutamate in the GGEEF motif for stimulating cellulose production.

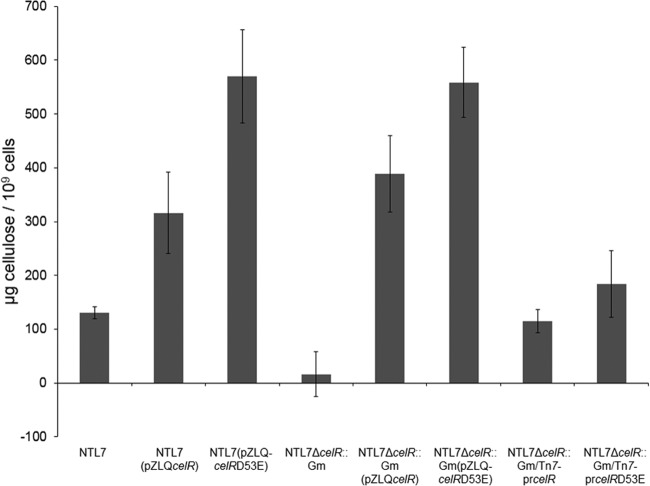

An Asp53 → Glu mutation in the first CheY domain of CelR results in increased cellulose production.

Analysis of the D53A mutant of CelR indicates that this amino acid is critical for the proper function of the protein. In proteins containing similar CheY-like receiver domains, the aspartate residue can be phosphorylated (46), and converting this residue to a glutamate often results in a constitutively active form of the protein (30). We examined the role of Asp53 in CelR by mutating this residue to glutamate and assessing the effect on cellulose synthesis. Overexpressing celRD53E in A. tumefaciens NTL7 resulted in increased cellulose production, even compared to a strain overexpressing wild-type celR (Fig. 3). Complementing the ΔcelR mutant with celRD53E inserted at unit copy number and expressed from its native promoter also resulted in increased levels of cellulose synthesis compared to the mutant complemented with wild-type celR (Fig. 3). These observations suggest that substituting glutamate for aspartate at position 53 results in a more active form of CelR. Taken together, our results are consistent with the notion that CelR is a bona fide c-di-GMP synthase and that it is part of a signaling pathway that involves phosphorylation at Asp53 in the CheY domain.

FIG 3.

Mutating Asp53 of celR to glutamate increases production of cellulose. (A and B) Strains NTL7, NTL7Δcel, and NTL7ΔcelR:Gm either overexpressing celRD53E (A) or expressing celRD53E from Tn7 insertions (B) were grown in MG/L medium with the appropriate antibiotics for 2 days at 28°C with shaking. The cells were harvested and assessed for production of cellulose as described in Materials and Methods. The values are averages of four samples for each strain, and the error bars depict standard errors of the experiments.

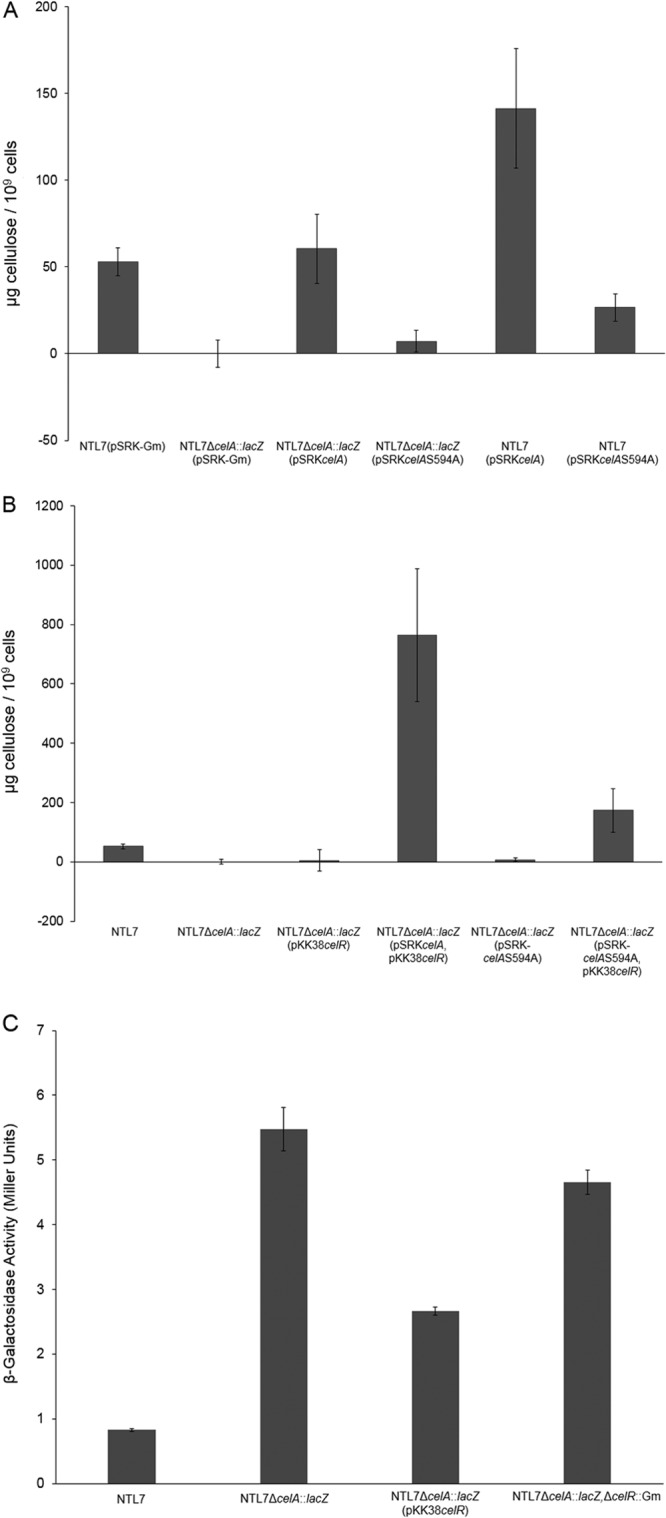

An intact PilZ domain of CelA is required for cellulose biosynthesis.

The presence of a PilZ domain on CelA suggests that full activity of the cellulose synthase depends upon binding c-di-GMP. Altering a conserved serine in the PilZ domains of other proteins can result in a significant decrease in the binding affinity of the nucleotide signal (47, 48). On the basis of these observations, we tested whether an intact PilZ domain of CelA is necessary by comparing levels of cellulose produced by a celA mutant complemented with either the wild-type gene or celAS594A, an allele with a mutation in the conserved serine (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (7). As expected, the celA::lacZ mutant did not produce detectable levels of cellulose (Fig. 4A). Complementing the indel mutant with wild-type celA expressed from pSRK-Gm restored cellulose production to wild-type levels (Fig. 4A), confirming that the celA mutation is not deleteriously polar on celB and celC. However, expressing the celAS594A allele failed to restore cellulose production to levels observed in strain NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ complemented with the wild-type gene (Fig. 4A). Further, while overexpressing wild-type celA in strain NTL7 led to high levels of cellulose production, overexpressing celAS594A in this strain led to considerably lower levels of the polymer (Fig. 4A). This result suggests that celAS594A exerts a modest dominant-negative effect on the wild-type gene. Moreover, these results support a requirement for the PilZ domain of CelA.

FIG 4.

The cellulose subunit CelA requires an intact PilZ domain to fully promote cellulose production. (A) Alleles of celA expressed on pSRK-Gm were introduced into strains NTL7 and NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ and constructed strains were examined for cellulose production as described in Materials and Methods. The values are averages of four samples for each strain, and the error bars depict standard errors of the experiments. (B) The wild-type celR gene was overexpressed in either strain NTL7 or NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ containing alleles of celA and assessed for production of cellulose as described in Materials and Methods. The values are averages of four experiments with the error bars depicting the standard errors of the experiments. (C) Strains of NTL7 and NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ were grown in MG/L medium containing the appropriate antibiotics overnight. The cells were harvested and examined for β-galactosidase activity all as described in Materials and Methods. Each experiment was repeated nine times, and error bars depict standard errors of the experiments.

In carefully studied systems, the mutation of the serine residue in the PilZ domain lowers, but does not eliminate, the binding affinity of c-di-GMP (47). It is conceivable, then, that the effect of the mutant PilZ domain on cellulose synthesis can be compensated for by overexpressing celR. We tested this possibility by overexpressing celR in strain NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ complemented with either wild-type celA or the celAS594A allele. Overexpressing celR in the celA mutant complemented with wild-type celA resulted in increased levels of cellulose compared to the parent strain (Fig. 4B). Further, overexpressing celR increased cellulose production in the celA mutant complemented with celAS594A, although not to the levels of the mutant complemented with wild-type celA (Fig. 4B). The results suggest that increasing the concentration of c-di-GMP can partially compensate for the mutation in the PilZ domain of CelA.

Altering celR expression does not affect transcription of celA.

While our results suggest that the c-di-GMP signal produced by CelR stimulates cellulose synthesis via the PilZ domain of CelA, it is conceivable that CelR or its nucleotide signal product induces transcription of the celA gene. To determine whether expression of celA is affected by CelR, we utilized the lacZ transcriptional fusion in strain NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ. As shown in Fig. 4C, the reporter mutant expresses celA at a modest level. Overexpressing celR in the celA mutant resulted in a 2-fold decrease in β-galactosidase activity from that of the parent strain (Fig. 4C), while deleting celR in the reporter mutant resulted in slightly lower levels of β-galactosidase activity compared to that of the parent strain (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that celR, expressed at its normal levels, has little or no direct effect on the transcription of celA.

The response regulator DivK affects production of cellulose through CelR.

In A. tumefaciens, celR is the distal gene in a two-gene operon that begins with atu1296, a gene generally annotated as divK (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The product of the well-studied founder ortholog, divK in Caulobacter crescentus, is required for localizing factors involved in cell division as well as activation of PleD, the ortholog of CelR (27, 49, 50). Given the operonic structure of divK-celR and the function of divK in other alphaproteobacteria, these observations suggest the possibility that divK plays a role in stimulating cellulose synthesis.

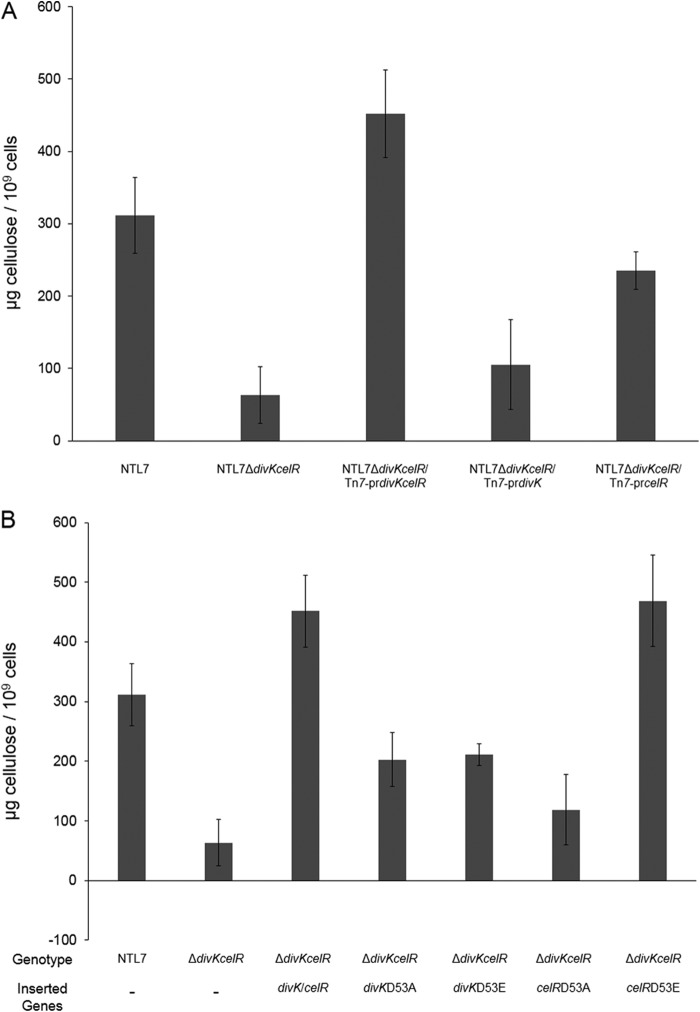

We first assessed the role of divK in regulating cellulose production by deleting the divK gene, creating strain NTL7ΔdivK::Km. The mutant produced significantly smaller amounts of the polymer compared to the wild type and matched the amount of cellulose produced by the ΔcelR mutant (Fig. 5A). This effect on cellulose production most likely is due to the polar nature of the ΔdivK indel mutation on celR. When introduced into this mutant in a single copy, celR under the control of its native promoter increased cellulose synthesis appreciably, although not to wild-type levels (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, this strain produced levels of cellulose equivalent to the those produced by strain NTL7ΔcelR::Gm complemented with the D53A allele of celR (Fig. 5A), suggesting that DivK plays a role in the pathway for activation of CelR. Complementing NTL7ΔdivK::Km with a chromosomally inserted construct containing both divK and celR (Tn7-prdivKcelR) restored cellulose production to wild-type levels (Fig. 5A). This result suggests that it is the absence of celR in the divK-celR deletion mutant that is responsible for most, but not all, of this decrease in levels of cellulose observed in NTL7ΔdivK::Km.

FIG 5.

DivK is required for full stimulation of cellulose production by CelR. (A) Strains with mutations in divK and celR were examined for cellulose production as described in Materials and Methods. Each experiment was repeated four times. The values are averages of the four samples of each strain, and the error bars depict standard errors of the experiments. (B) The celR gene was overexpressed in strains NTL7, NTL7ΔcelA::lacZ, and NTL7ΔdivK::Km, and constructed strains were assessed for production of cellulose as described in Materials and Methods. Each experiment was repeated four times. The values are averages of the four samples for each strain, and the error bars depict standard errors of the experiments. (C) Either celR or celRD53E was introduced into strains NTL7 and NTL7ΔdivK::Km by Tn7 insertion, and the constructed strains were examined for cellulose production as described in Materials and Methods. Each experiment was repeated four times. The values are averages of four samples for each strain, and the error bars depict standard errors of the experiments.

The influence of DivK suggests that this CheY-like protein, a putative response regulator (8, 9), is required for CelR-mediated stimulation of cellulose synthesis. If this is correct, the full effect of celR overexpression should require an expressed copy of divK. To test this hypothesis, pKK38celR was introduced into strain NTL7ΔdivK::Km complemented with either Tn7-prcelR or Tn7-prdivKcelR. Overexpressing celR did lead to a modest increase in cellulose production in strain NTL7ΔdivK::Km or NTL7ΔdivK::Km/Tn7-prcelR (Fig. 5B). That increased celR expression failed to fully compensate for the loss of divK further demonstrates the importance of the CheY homolog in the signaling pathway. When celR was overexpressed in the divK deletion mutant complemented with Tn7-prdivKcelR, levels of cellulose accumulation were significantly higher, exceeding even the levels observed in wild-type NTL7 overexpressing celR (Fig. 5B).

These results support the involvement of DivK in the signaling pathway that activates CelR. To test this requirement for DivK, we determined whether the constitutively active form of celR stimulates cellulose production in the divK mutant. As described earlier, compared to wild-type celR, overexpression of celRD53E in strain NTL7 resulted in a significant increase in cellulose production (Fig. 3A). While introducing wild-type celR into strain NTL7ΔdivK::Km did not restore cellulose production to wild-type levels (Fig. 5C), introducing the constitutively active form of the diguanylate cyclase yielded significantly higher levels of cellulose in the divK mutant (Fig. 5C). We conclude from these results that the constitutively active form of CelR can compensate for the loss of divK, and from this, that DivK is involved in the pathway for activation of CelR.

The aspartate residues in the CheY domains of both DivK and CelR are important for cellulose production.

The effects of altering the conserved aspartate residues of divK and celR suggest that the two residues are critical for stimulating cellulose synthesis. To examine the roles of these two residues, the divK-celR operon was deleted, and the resulting strain, NTL7ΔdivKcelR, was complemented with wild-type and mutant alleles of divK and celR using the mini-Tn7 chromosomal insertion system. Deleting divK and celR resulted in a 5-fold decrease in cellulose production compared to the wild-type parent (Fig. 6A). Complementing the mutant with Tn7-prdivKcelR, in which both genes are wild-type genes, restored cellulose production to wild-type levels, while complementation with either divK or celR alone did not fully restore synthesis of the polymer (Fig. 6A). These results are consistent with the results of our complementation analysis of the divK mutant with either gene (Fig. 5). Complementing the Δ(divK-celR) mutation with divKD53A or divKD53E resulted in modest increases in levels of cellulose production (Fig. 6B), suggesting that the presence of divK has a minor effect on polymer production. Introducing celRD53A into the Δ(divK-celR) mutant also failed to fully restore cellulose synthesis (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, complementing the mutation with celRD53E restored cellulose production to greater than wild-type levels (Fig. 6B). That constitutively active CelR can compensate for the loss of the putative response regulator, while wild-type CelR does not suggests that DivK is necessary for CelR to fully stimulate cellulose production.

FIG 6.

Stimulation of cellulose synthesis requires both celR and divK. (A and B) Strain NTL7ΔdivKcelR was complemented by Tn7 insertion with wild-type divK, celR, or the divK-celR operon (A) and alleles of divK or celR altered at Asp53 (B). Strains were assessed for production of cellulose as described in Materials and Methods. The values are averages of four samples for each strain, and the error bars depict standard errors of the experiments.

To more fully evaluate the role of the aspartate residues of both celR and divK, the divK-celR operon, with either divK or celR mutated at D53, was reintroduced into the divK-celR double mutant at unit copy number using the Tn7 system. A. tumefaciens NTL7ΔdivKcelR complemented with wild-type divK and celRD53A failed to increase cellulose production compared to the parent mutant (Fig. 7A). However, complementation with wild-type divK and celRD53E resulted in a 2-fold increase in cellulose synthesis compared to levels of the polymer produced by wild-type NTL7 (Fig. 7A). Complementing the double mutant with wild-type celR and divKD53A restored cellulose production to wild-type levels (Fig. 7A), while complementation with wild-type celR and divKD53E resulted in cellulose levels 2-fold greater than those observed in strain NTL7 (Fig. 7A). These data indicate that the D53E alleles of both celR and divK stimulate cellulose production.

FIG 7.

An aspartate at position 53 in both DivK and CelR is necessary for stimulating cellulose production. (A and B) Strain NTL7ΔdivKcelR was complemented by Tn7 insertion with prdivKcelR containing an altered form of either divK or celR at Asp53 (A) or with both divK and celR mutated at Asp53 (B). The cells were grown, harvested, and assessed for production of cellulose as described in Materials and Methods. The values are averages of four samples for each strain, and the error bars depict standard errors of the experiments.

The effect of mutating the key aspartate residue to glutamate in both DivK and CelR suggests that altering the residue in both proteins would also increase cellulose production. To test this hypothesis, the divK-celR deletion mutant was complemented with a mini-Tn7 insertion carrying both genes mutated at Asp53. Insertion of either divKD53A-celRD53A or divKD53E-celRD53A did not result in significantly higher levels of cellulose compared to the parent mutant (Fig. 7B), suggesting that divK alone does not stimulate cellulose synthesis. When divKD53A-celRD53E or divKD53E-celRD53E were inserted into the double mutant, the complemented strains produced amounts of cellulose comparable to or somewhat greater than amounts produced by wild-type NTL7 (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that constitutively active CelR stimulates cellulose production, regardless of the allelic nature of Asp53 in divK.

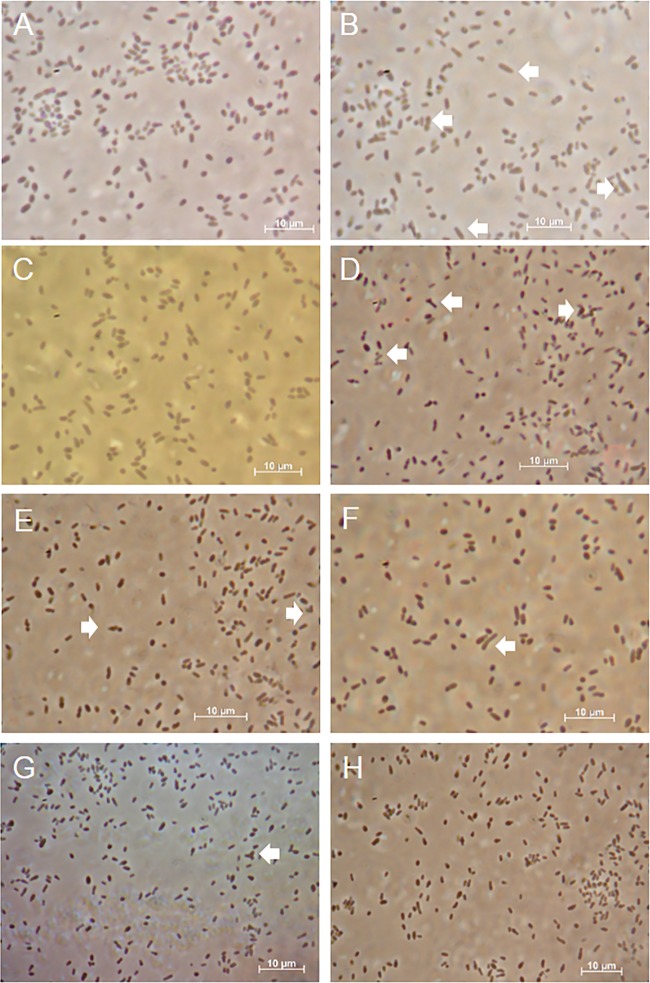

Deleting divK affects cell morphology.

In C. crescentus, DivK acts as a critical checkpoint regulator for cell cycle progression (50, 51). DivK also is involved in regulating cell division in A. tumefaciens; deleting the divK gene results in morphologically abnormal cells (29). We assessed the effect of deleting both divK and celR on cell morphology by phase-contrast microscopy. Compared to the parent, the Δ(divK-celR) mutant displayed a greater number of cells with morphological defects, including branched and elongated forms (compare Fig. 8A and B; Table 3). Complementing the mutation with Tn7-prdivKcelR restored the frequency of abnormal cell morphologies to that of the wild-type (compare Fig. 8A and C; Table 3). As expected from the report by Kim et al. (29), complementing the double mutant with divK alone lowered the frequency of the cell morphology defects to wild-type levels (Fig. 8F and Table 3). Moreover, the constitutively active form of divK complemented the defects in strain NTL7ΔdivKcelR in the presence or absence of celR (Fig. 8G and H and Table 3). However, complementing the Δ(divK-celR) mutant with only prcelR or prcelRD53E did not reduce the number of cells exhibiting morphological defects (Fig. 8D and E and Table 3), suggesting that celR has no effect on processes that control morphology. These results support the involvement of divK in cell division of A. tumefaciens but suggest that celR does not play a role in cell cycle regulation.

FIG 8.

Deleting divK affects cell morphology. Cultures of strain NTL7 and its derivatives were grown in MG/L medium, and samples were viewed by phase-contrast microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. (A) NTL7; (B) NTL7ΔdivKcelR; (C) NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKcelR; (D) NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prcelR; (E) NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prcelRD53E; (F) NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivK; (G) NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKD53E; (H) NTL7ΔdivKcelR/Tn7-prdivKD53EcelR. The white arrows indicate branched or elongated cells. Bars, 10 μm.

TABLE 3.

The loss of divK results in increased frequency of branched and misshapen cells

| Strain | Complementing Tn7 insertion | Total no. of cells | Total no. of misshapen cells | % Misshapen cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTL7 | None | 962 | 5 | 0.52 |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR | None | 736 | 29 | 3.91a |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR | prdivKcelR | 1,057 | 9 | 0.87 |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR | prcelR | 631 | 17 | 2.63a |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR | prcelRD53E | 799 | 21 | 2.62a |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR | prdivK | 938 | 7 | 0.74 |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR | prdivKD53E | 789 | 6 | 0.78 |

| NTL7ΔdivKcelR | prdivKD53EcelR | 764 | 5 | 0.69 |

This value was significantly different (P < 0.05) from the value for strain NTL7.

CelR forms homodimers but does not interact with DivK.

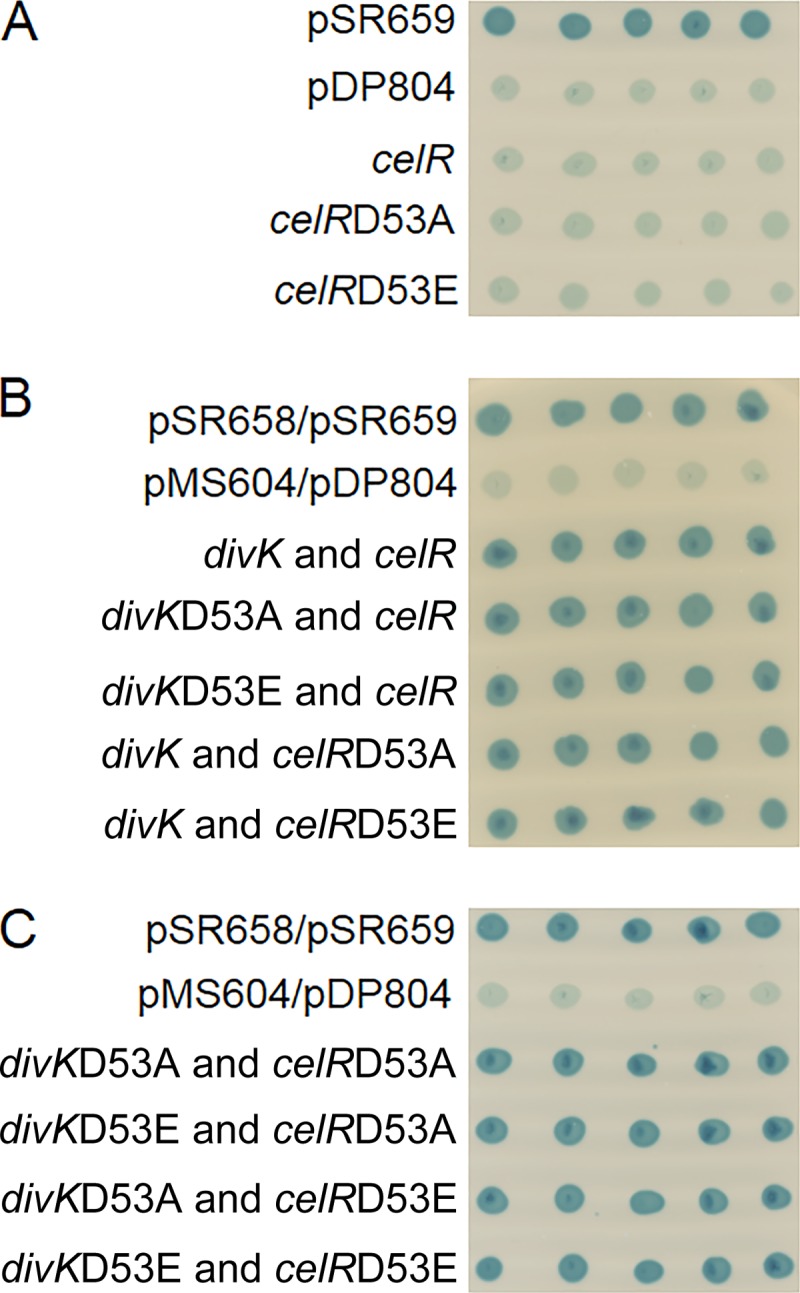

That DivK contributes to the regulation of cellulose production through CelR suggests that the CheY-like protein is a component of the pathway for activation of the DGC. Since DivK functions by binding with its targets in other species of alphaproteobacteria (50), it is possible that the protein interacts directly with CelR. We tested this hypothesis using a bacterial two-hybrid assay as described in Materials and Methods. In this assay, interaction between two proteins leads to repression of lacZ, resulting in light blue colonies when the cells are grown on medium containing X-Gal. The two-hybrid strain expressing celR from pSR659 formed light blue colonies in the presence of X-Gal, suggesting that the DGC interacts with itself to generate an active hybrid LexA repressor (Fig. 9A). Mutating Asp53 to Ala or Glu had no effect on this reaction (Fig. 9A), suggesting that although CelR homodimerizes, this interaction is not dependent on signal-induced modifications at Asp53. Strains expressing wild-type CelR and DivK on separate plasmids hydrolyzed X-Gal (Fig. 9B), indicative of a failure of the two proteins to interact. Mutating Asp53 to alanine or glutamate on both DivK and CelR did not result in a positive reaction for protein interaction (Fig. 9B and C).

FIG 9.

CelR forms homodimers, but it does not interact with DivK. (A) Reporter strain SU101 with positive (pDP804) and negative controls (pSR659) and with two-hybrid expression vectors containing alleles of celR. (B) Reporter strain SU202 containing positive (pDP804/pMS604) and negative controls (pSR658/pSR659) and two-hybrid expression vectors with wild-type divK and altered alleles of celR or with celR and altered alleles of divK. (C) Reporter strain SU202 containing positive (pDP804/pMS604) and negative controls (pSR658/pSR659) and two-hybrid expression vectors with altered alleles of divK and celR. All strains were grown on LB agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotics, IPTG, and X-Gal overnight at 28°C.

DISCUSSION

CelR regulates cellulose synthesis through production of c-di-GMP.

Previously, we reported that the putative diguanylate cyclase CelR is required for stimulating cellulose production in A. tumefaciens (22). Given that CelR contains both a CheY-like response receiver domain and a catalytic GGEEF domain (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), we hypothesized that CelR is part of a signaling system that controls cellulose synthesis. Recent biochemical studies showed that CelR likely produces c-di-GMP (52) but did not link this signal to the regulation of cellulose synthesis. Our results reported here demonstrate that CelR requires the catalytic GGEEF motif to stimulate production of the polymer; a mutant modified in this motif failed to complement strains in which celR had been deleted (Fig. 3). This observation, coupled with results from Xu et al. (52), supports our hypothesis that CelR is a bona fide cyclase and that the cyclic dinucleotide signal produced by this enzyme influences cellulose synthesis.

CelR requires the conserved aspartate residue in the CheY domain to stimulate cellulose production.

Conservation of an aspartate in the CheY domain of CelR and its orthologs in other species (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) suggests that the residue is important for activation of the protein, likely as a target for phosphorylation (46). Our current results support this hypothesis; mutating aspartate 53 to an alanine abolished CelR-dependent stimulation of cellulose production either when overexpressed or when the mutant allele was used to complement a celR deletion mutant (Fig. 3). A similar mutation in the conserved aspartate in the CheY domain of PleD of C. crescentus prevented cells from building the polarly located holdfast stalk (23, 25, 31).

In the case of PleD of C. crescentus, mutating the conserved aspartate in the CheY domain to glutamate creates a constitutively active form of the protein; expressing the mutant allele results in increased formation of holdfast structures and deformed cells (25). In other proteins with CheY-related receiver domains, the conversion of the aspartate residue to glutamate often but not always mimics the activated state (53, 54). These observations suggest that a similar mutation in celR will result in a constitutively active form of the protein. Indeed, either overexpressing celRD53E or complementing the ΔcelR mutant with the mutant allele resulted in increased amounts of cellulose synthesis compared to the deletion mutant expressing wild-type celR (Fig. 3). Taken together, our analysis of the two Asp53 mutants of CelR suggests that for its activity, the protein requires activation, likely by phosphorylation of the conserved aspartate residue.

That CelR requires activation, likely by a kinase, suggests that cellulose synthesis is controlled by some as yet unidentified environmental cue that results in delivery of c-di-GMP from the DGC to a target further along the pathway. To date, our attempts to identify the environmental signal that stimulates cellulose production have not been successful (data not shown). Further work will be needed to identify both the upstream signal and the kinase that activates CelR.

The PilZ domain of CelA is necessary for cellulose synthesis.

Given that CelR is a bona fide c-di-GMP synthase, there must be a downstream signal receptor that is involved in cellulose synthesis. In many organisms, the catalytic subunit of the cellulose synthase, including CelA of A. tumefaciens, contains a c-di-GMP-binding PilZ domain (19). Certain residues in PilZ-containing proteins, including a serine within a DXSXXG motif, are required for binding c-di-GMP (55, 56). CelA in A. tumefaciens contains this motif, and mutating Ser594 to alanine prevented full complementation of a celA deletion mutant (Fig. 4), suggesting that the serine residue within this motif is required for cellulose synthesis. In in vitro studies of both PlzD of Vibrio cholerae and Alg44 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (47, 55), mutating this serine lowers the binding affinity for c-di-GMP. One might expect that increasing the levels of the signal could compensate for the lower affinity of the altered PilZ domain in CelA. Indeed, overexpressing celR somewhat stimulated cellulose synthesis in the celA deletion mutant complemented with celAS594A (Fig. 4), further supporting the role of c-di-GMP in regulating production of the polymer.

We considered the possibility that CelR, in some manner, regulates transcription of the cel regulon. Based on our assays of a celA::lacZ fusion, expression of the synthase from its native promoter is relatively low (Fig. 4A). Mutating or overexpressing celR did not significantly affect the level of celA expression, suggesting that the cyclase does not affect transcription of the celABC operon. This result further supports our hypothesis that CelR stimulates cellulose production through activation of CelA via c-di-GMP.

Taken together, our observations are consistent with a pathway in which CelR produces c-di-GMP and with this signal stimulating cellulose synthesis by activating CelA. Biochemical analysis of BcsA in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium, a homolog to CelA, demonstrated that c-di-GMP binding activates cellulose synthesis and that mutating critical binding residues in the PilZ domain abolished signal binding and enzymatic activity (57, 58). According to the current model, signal binding at the PilZ domain of BcsA allosterically controls cellulose production by triggering conformational changes in the complex that result in increased enzymatic activity (57, 58). Moreover, because CelR requires activation to synthesize c-di-GMP, the combined results suggest that any stimulation of polymer production by CelA requires an upstream signaling cascade.

DivK participates in regulating cellulose synthesis through CelR.

The operonal organization of celR with divK suggests that both genes are involved in regulating cellulose synthesis. Previous studies demonstrated that DivK of C. crescentus is a CheY-type response regulator and is phosphorylated by the hybrid kinase DivJ (26, 50). Our studies of DivK in A. tumefaciens support a role for this putative response regulator in stimulating production of the polymer through CelR. In a divK deletion mutant, wild-type CelR failed to fully stimulate cellulose production (Fig. 5). However, a constitutively active form of the c-di-GMP synthase compensated for the loss of the response regulator; expressing celRD53E restored polymer synthesis to the divK mutant. These results suggest that DivK is important for the Asp53-dependent activation of CelR and subsequent stimulation of cellulose synthesis.

That DivK is composed of a single CheY-like domain (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) with its conserved aspartate residue suggests that the protein is activated in a manner similar to CelR. Indeed, conversion of Asp53 in DivK to alanine prevented full stimulation of cellulose synthesis (Fig. 6). On the other hand, complementing the ΔdivK mutant with the divKD53E allele resulted in higher levels of cellulose compared to the deletion mutant complemented with wild-type divK (Fig. 5 and 7). Consistent with this interpretation, the levels of cellulose produced by the divKD53E mutant were comparable to the levels observed from strains expressing celRD53E (Fig. 7B). These results support the hypothesis that DivK, like many other members of the CheY family, can be activated, probably by phosphorylation at Asp53, and that this activation is part of a signaling pathway that results in activating CelR.

In C. crescentus, phosphorylated DivK interacts with its target, the master response regulator CtrA, resulting in localization of the CtrA-DivK complex to the target pole of the cell (50, 59, 60). Based on our two-hybrid analyses, DivK does not directly interact with CelR (Fig. 8), although our two-hybrid analysis indicates that CelR likely homodimerizes. The latter result is consistent with our observation that the celRD53A mutation exerts dominant negativity (Fig. 2), as well as with crystallographic and biochemical studies of PleD, the CelR ortholog in C. crescentus (31, 43). Interestingly, the DGC activity of PleD requires dimerization (31). Clearly, DivK must interact with some upstream kinase, and in its phosphorylated form, it must interact with some downstream target that affects the phosphorylation state of CelR. While we have no evidence that DivK directly interacts with CelR, the response regulator may localize other components of the signal pathway. Further studies of these interactions will be necessary to determine the mechanism by which DivK participates in the regulation of cellulose synthesis.

DivK, but not CelR, functions in pathways for both cellulose synthesis and cell division.

In addition to regulating cellulose synthesis, a recent study by Kim et al. (29) clearly showed that DivK functions in regulating processes important for cell division in A. tumefaciens. Our results support this hypothesis; deleting divK resulted in cell division defects, illustrated by elongated and branched cells (Fig. 8). In several alphaproteobacteria, including A. tumefaciens and the related Sinorhizobium meliloti, divK and its orthologs are linked to both polar localization of cell division proteins (25, 28, 29, 61, 62) and initiation of S phase through localization and degradation of CtrA (51). Coupled with our observations that DivK is required for activating CelR, it is clear that the CheY homolog of A. tumefaciens retains its role in regulating cell division while also modulating cellulose synthesis.

Such a role for DivK in other alphaproteobacteria is not without precedent. In C. crescentus, activated DivK stimulates construction of the stalk and holdfast assembly, as well as initiating cell cycle progression. The response regulator apparently participates in these two pathways by stimulating the PleC and DivJ hybrid kinases associated with the two systems (27, 50, 51). The activated forms of PleC and DivJ either phosphorylate or dephosphorylate cell division proteins and PleD, which signals the construction of the stalk (27). Given the relatedness of DivK in A. tumefaciens to its orthologs (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), the effects of mutating divK on cell division in a number of bacteria (25, 28, 29, 61, 62), and the presence of homologs of divK in a large number of the alphaproteobacteria (63), it is likely that the protein plays a critical role in regulating cell division in all of the alphaproteobacteria that carry the gene. Further, in C. crescentus, DivK interfaces stalk production to cell division by activating PleD through stimulation of the activating kinase, DivJ (27, 50). In this manner, activated DivK not only drives the cell cycle through S phase but also initiates stalk construction concurrently with cell cycle progression through a separate signal transduction pathway.

Our results demonstrate that DivK maintains a dual function in A. tumefaciens, but unlike C. crescentus, it regulates these pathways independently. CelR mutants show no morphological or developmental defects (22) (Fig. 8), suggesting that the DGC, although requiring DivK for activity, does not influence cell division. Furthermore, expressing divKD53E stimulated cellulose synthesis but did not affect cell morphology. That the regulatory effects of DivK on production of the polymer are independent from the controls on cell division suggest that DivK regulates both processes but that it does not necessarily link the two pathways.

While the role of DivK in cell cycle regulation is conserved in many alphaproteobacteria, its adaption to a secondary regulatory function seems dependent upon the corresponding DGC in the operon. The observation that CelR has adapted to stimulate cellulose synthesis in A. tumefaciens and Rhizobium leguminosarum (64), rather than regulating polar adhesion (22, 64), suggests that the role of the DGC is based on the biological system needed by the bacteria. In this manner, the divK-celR (pleD) operon functions as a system to regulate species-specific processes through established signal transduction pathways. The dual roles of DivK likely allow some species of alphaproteobacteria to connect cell division to specific needs, such as attachment or biofilm formation. DivK may also respond to different signal inputs, resulting in activation of each pathway based on these cues.

Given the number of processes regulated by c-di-GMP in A. tumefaciens (22, 52), production and distribution of the signal must be tightly controlled to prevent cross talk with other systems. The requirement for c-di-GMP binding by CelA resulted in adapting the transduction pathway containing CelR for regulating production of cellulose. However, some, but not all, DGCs can influence cellulose synthesis when overexpressed (22). Therefore, the interaction of c-di-GMP and CelA must be spatially and temporally controlled, either through direct interaction of the DGC with the synthase or by localization of CelR near the cellulose synthase complex. Further analysis of CelR localization will help determine how the c-di-GMP signal is targeted to CelA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Peter Orlean for helpful discussions concerning cellulose assays and H. P. Schweizer for the mini-Tn7 transposon system.

This research was supported in part by grant R01 GM52465 from the NIH to S.K.F., Sponsored Research Agreement 2010-06329 from Syngenta to S.K.F., and grant SC0006642 from the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research to J. Sweedler, P. Bohn, and S.K.F.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 January 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01446-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lippincott BB, Lippincott JA. 1969. Bacterial attachment to a specific wound site as an essential stage in tumor initiation by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 97:620–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lippincott BB, Whatley MH, Lippincott JA. 1977. Tumor induction by Agrobacterium involves attachment of the bacterium to a site on the host plant cell wall. Plant Physiol. 59:388–390. 10.1104/pp.59.3.388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthysse AG, Holmes KV, Gurlitz RH. 1981. Elaboration of cellulose fibrils by Agrobacterium tumefaciens during attachment to carrot cells. J. Bacteriol. 145:583–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthysse AG. 1983. Role of bacterial cellulose fibrils in Agrobacterium tumefaciens infection. J. Bacteriol. 154:906–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthysse AG, McMahan S. 1998. Root colonization by Agrobacterium tumefaciens is reduced in cel, attB, attD, and attR mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2341–2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthysse AG, Marry M, Krall L, Kaye M, Ramey BE, Fuqua C, White AR. 2005. The effect of cellulose overproduction on binding and biofilm formation on roots by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18:1002–1010. 10.1094/MPMI-18-1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matthysse AG, White S, Lightfoot R. 1995. Genes required for cellulose synthesis in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 177:1069–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodner B, Hinkle G, Gattung S, Miller N, Blanchard M, Qurollo B, Goldman BS, Cao Y, Askenazi M, Halling C, Mullin L, Houmiel K, Gordon J, Vaudin M, Iartchouk O, Epp A, Liu F, Wollam C, Allinger M, Doughty D, Scott C, Lappas C, Markelz B, Flanagan C, Crowell C, Gurson J, Lomo C, Sear C, Strub G, Cielo C, Slater S. 2001. Genome sequence of the plant pathogen and biotechnology agent Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2323–2328. 10.1126/science.1066803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood DW, Setubal JC, Kaul R, Monks DE, Kitajima JP, Okura VK, Zhou Y, Chen L, Wood GE, Almeida NF, Jr, Woo L, Chen Y, Paulsen IT, Eisen JA, Karp PD, Bovee D, Chapman P, Sr, Clendenning J, Deatherage G, Gillet W, Grant C, Kutyavin T, Levy R, Li MJ, McClelland E, Palmieri A, Raymond C, Rouse G, Saenphimmachak C, Wu Z, Romero P, Gordon D, Zhang S, Yoo H, Tao Y, Biddle P, Jung M, Krespan W, Perry M, Gordon-Kamm B, Liao L, Kim S, Hendrick C, Zhao ZY, Dolan M, Chumley F, Tingey SV, Tomb JF, Gordon MP, Olson MV, Nester EW. 2001. The genome of the natural genetic engineer Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2317–2323. 10.1126/science.1066804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthysse AG, Thomas DL, White AR. 1995. Mechanism of cellulose synthesis in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 177:1076–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saxena IM, Kudlicka K, Okuda K, Brown RM., Jr 1994. Characterization of genes in the cellulose-synthesizing operon (acs operon) of Acetobacter xylinum: implications for cellulose crystallization. J. Bacteriol. 176:5735–5752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zogaj X, Nimtz M, Rohde M, Bokranz W, Romling U. 2001. The multicellular morphotypes of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli produce cellulose as the second component of the extracellular matrix. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1452–1463. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitney JC, Colvin KM, Marmont LS, Robinson H, Parsek MR, Howell PL. 2012. Structure of the cytoplasmic region of PelD, a degenerate diguanylate cyclase receptor that regulates exopolysaccharide production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 287:23582–23593. 10.1074/jbc.M112.375378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan JL, Strumillo J, Zimmer J. 2013. Crystallographic snapshot of cellulose synthesis and membrane translocation. Nature 493:181–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong HC, Fear AL, Calhoon RD, Eichinger GH, Mayer R, Amikam D, Benziman M, Gelfand DH, Meade JH, Emerick AW, Bruner R, Ben-Bassat A, Tal R. 1990. Genetic organization of the cellulose synthase operon in Acetobacter xylinum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:8130–8134. 10.1073/pnas.87.20.8130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross P, Aloni Y, Weinhouse C, Michaeli D, Weinberger-Ohana P, Meyer R, Benziman M. 1985. An unusual guanyl oligonucleotide regulates cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum. FEBS Lett. 186:191–196. 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80706-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross P, Weinhouse H, Aloni Y, Michaeli D, Weinberger-Ohana P, Mayer R, Braun S, de Vroom E, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH, Benziman M. 1987. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 325:279–281. 10.1038/325279a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinhouse H, Sapir S, Amikam D, Shilo Y, Volman G, Ohana P, Benziman M. 1997. c-di-GMP-binding protein, a new factor regulating cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum. FEBS Lett. 416:207–211. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01202-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amikam D, Galperin MY. 2006. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics 22:3–6. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryjenkov DA, Simm R, Romling U, Gomelsky M. 2006. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP: the PilZ domain protein YcgR controls motility in enterobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 281:30310–30314. 10.1074/jbc.C600179200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amikam D, Benziman M. 1989. Cyclic diguanylic acid and cellulose synthesis in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 171:6649–6655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnhart DM, Su S, Baccaro BE, Banta LM, Farrand SK. 2013. CelR, an ortholog of the diguanylate cyclase PleD of Caulobacter, regulates cellulose synthesis in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:7188–7202. 10.1128/AEM.02148-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hecht GB, Newton A. 1995. Identification of a novel response regulator required for the swarmer-to-stalked-cell transition in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 177:6223–6229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hecht GB, Lane T, Ohta N, Sommer JM, Newton A. 1995. An essential single domain response regulator required for normal cell division and differentiation in Caulobacter crescentus. EMBO J. 14:3915–3924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aldridge P, Paul R, Goymer P, Rainey P, Jenal U. 2003. Role of the GGDEF regulator PleD in polar development of Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1695–1708. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam H, Matroule JY, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2003. The asymmetric spatial distribution of bacterial signal transduction proteins coordinates cell cycle events. Dev. Cell 5:149–159. 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00191-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsokos CG, Perchuk BS, Laub MT. 2011. A dynamic complex of signaling proteins uses polar localization to regulate cell-fate asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Dev. Cell 20:329–341. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallez R, Mignolet J, Van Mullem V, Wery M, Vandenhaute J, Letesson JJ, Jacobs-Wagner C, De Bolle X. 2007. The asymmetric distribution of the essential histidine kinase PdhS indicates a differentiation event in Brucella abortus. EMBO J. 26:1444–1455. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J, Heindl JE, Fuqua C. 2013. Coordination of division and development influences complex multicellular behavior in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. PLoS One 8:e56682. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul R, Weiser S, Amiot NC, Chan C, Schirmer T, Giese B, Jenal U. 2004. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev. 18:715–727. 10.1101/gad.289504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul R, Abel S, Wassmann P, Beck A, Heerklotz H, Jenal U. 2007. Activation of the diguanylate cyclase PleD by phosphorylation-mediated dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 282:29170–29177. 10.1074/jbc.M704702200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sondermann H, Shikuma NJ, Yildiz FH. 2012. You've come a long way: c-di-GMP signaling. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15:140–146. 10.1016/j.mib.2011.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. 2013. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77:1–52. 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chilton M-D, Currier TC, Farrand SK, Bendich AJ, Gordon MP, Nester EW. 1974. Agrobacterium tumefaciens DNA and PS8 bacteriophage DNA not detected in crown gall tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 71:3672–3676. 10.1073/pnas.71.9.3672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cangelosi GA, Ankenbauer RG, Nester EW. 1990. Sugars induce the Agrobacterium virulence genes through a periplasmic binding protein and a transmembrane signal protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:6708–6712. 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]