Abstract

Our previous study showed that bacterial genomes can be identified using 16S rRNA sequencing in urine specimens of both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients who are culture negative according to standard urine culture protocols. In the present study, we used a modified culture protocol that included plating larger volumes of urine, incubation under varied atmospheric conditions, and prolonged incubation times to demonstrate that many of the organisms identified in urine by 16S rRNA gene sequencing are, in fact, cultivable using an expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC) protocol. Sixty-five urine specimens (from 41 patients with overactive bladder and 24 controls) were examined using both the standard and EQUC culture techniques. Fifty-two of the 65 urine samples (80%) grew bacterial species using EQUC, while the majority of these (48/52 [92%]) were reported as no growth at 103 CFU/ml by the clinical microbiology laboratory using the standard urine culture protocol. Thirty-five different genera and 85 different species were identified by EQUC. The most prevalent genera isolated were Lactobacillus (15%), followed by Corynebacterium (14.2%), Streptococcus (11.9%), Actinomyces (6.9%), and Staphylococcus (6.9%). Other genera commonly isolated include Aerococcus, Gardnerella, Bifidobacterium, and Actinobaculum. Our current study demonstrates that urine contains communities of living bacteria that comprise a resident female urine microbiota.

INTRODUCTION

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a highly prevalent syndrome characterized by urinary urgency with or without urge urinary incontinence and is often associated with frequency and nocturia (1). The etiology of OAB is often unclear and antimuscarinic treatments aimed at relaxing the bladder are ineffective in a large percentage of OAB sufferers, thereby suggesting etiologies outside neuromuscular dysfunction (2). One possibility is that OAB symptoms are influenced by microbes that inhabit the lower urinary tract (urinary microbiota).

The microbiota of the female urinary tract has been poorly described; primarily, because a “culture-negative” status has been equated with the dogma that normal urine is sterile. Yet, emerging evidence indicates that the lower urinary tract can have a urinary microbiota (3–8). For example, our group previously reported the use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing to identify bacterial DNA (urinary microbiome) in culture-negative urine specimens collected from women diagnosed with pelvic prolapse and/or urinary incontinence, as well as from urine of women without urinary symptoms (4). Other investigators also have used culture-independent 16S rRNA gene sequencing to obtain evidence of diverse bacteria that are not routinely cultivated by clinical microbiology laboratories in the urine of both women and men (3, 6, 9, 10).

Most of our previously sequenced urine specimens underwent standard clinical urine cultures that were reported as “no growth” at a 1:1000 dilution by our diagnostic microbiology laboratory (4). On the basis of this sequence-based evidence, which supports the presence of a urinary microbiome, we hypothesized that bacterial members of the urinary microbiota are not reported in routine urine cultures either because the number of organisms present is below the culture threshold of 103 CFU/ml or because growth of these bacteria required special culture conditions, such as anaerobic atmosphere, incubation in an increased CO2 environment, or prolonged incubation time.

Furthermore, sequencing cannot determine whether the bacterial sequences observed in these culture-negative patients represent live bacterial species. Therefore, we conducted this study to determine whether the urinary microbiome was the product of living microbiota that consisted largely of organisms that would be missed by routine clinical microbiology culture practices. To address this question, we altered the routine urine culture conditions to include the plating of a greater volume of urine, incubation in varied atmospheric conditions, and the use of extended incubation times. Using these modified culture and incubation tactics (expanded quantitative urine culture [EQUC]), we demonstrated that many of the organisms identified in urine by 16S rRNA gene sequencing are in fact cultivable.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and sample collection.

Following Loyola institutional review board (IRB) approval for all phases of this project, participants gave verbal and written consent for the collection and analysis of their urine for research purposes. Participants were women undergoing OAB treatment and a comparison group of women undergoing benign gynecologic surgery (controls). Participants' symptoms were characterized with the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI), a self-completed, validated symptom questionnaire. All participants were without clinical evidence of urinary tract infection (i.e., urine culture negative and absence of clinical urinary tract infection [UTI] diagnosis). Urine was collected via transurethral catheter from participants for the period March 2013 to July 2013 at the Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery center of Loyola University Medical Center. A portion of each urine sample was placed in a BD Vacutainer Plus C&S preservative tube (Becton, Dickinson and Co, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and sent to the clinical microbiology lab for quantitative culture. A separate portion of the urine sample, to be used for sequencing, was placed at 4°C for no more than 4 h following collection. To this portion, 10% AssayAssure (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added before freezing at −80°C.

Standard urine culture.

Standard urine culture was performed by inoculating 0.001 ml of urine onto a 5% sheep blood agar plate (BAP) and MacConkey agars (BD BBL prepared plated media; Becton, Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD) and streaking the entire plate surface to obtain quantitative colony counts. The plates were incubated aerobically at 35°C for 24 h. Each separate morphological colony type was counted and identified in any amount. The detection level was 103 CFU/ml, represented by 1 colony of growth on either plate. If no growth was observed, the culture was reported as “no growth” (of bacteria at lowest dilution, i.e., 1:1000).

Expanded quantitative urine culture.

Each catheterized urine sample was processed following the standard urine culture procedure by the clinical microbiology lab and was also processed using the EQUC procedure. For EQUC, 0.1 ml of urine was inoculated onto BAP, chocolate and colistin, and nalidixic acid (CNA) agars (BD BBL prepared plated media), streaked for quantitation, and incubated in 5% CO2 at 35°C for 48 h. For a second set of BAPs, each was inoculated with 0.1 ml of urine and incubated in room atmosphere at 35°C and 30°C for 48 h. Next, 0.1 ml of urine was inoculated onto each of two CDC anaerobe 5% sheep blood agar plates (BD BBL prepared plated media) and incubated in either a Campy gas mixture (5% O2, 10% CO2, 85% N) or under anaerobic conditions at 35°C for 48 h. The detection level was 10 CFU/ml, represented by 1 colony of growth on any of the plates. Finally, to detect any bacterial species that may be present at quantities lower than 10 CFU/ml, 1.0 ml of urine was placed in thioglycolate medium (BD BBL prepared tubed media) and incubated aerobically at 35°C for 5 days. If growth was visually detected in the thioglycolate medium, the medium was mixed and a few drops were plated on BAP and CDC anaerobe 5% sheep blood agars for isolation and incubated aerobically and anaerobically at 35°C for 48 h. Each morphologically distinct colony type was isolated on a different plate of the same media to prepare a pure culture that was used for identification.

Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry.

Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) was performed using the direct colony method. Using toothpicks, we applied a small portion of a single isolated colony to the surface of a 96-spot, polished, stainless steel target plate (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Leipzig, Germany) in a manner that created a thin bacterial film. The spot was left to dry at room temperature for 1 min., whereupon 1.0 μl of 70% formic acid was applied to each sample and allowed to dry at room temperature for 10 min. Then, 1.0 μl of the matrix solution, comprised of saturated α-cyano-4-hydrocinnamic acid (Bruker Daltonik) in an organic solvent (high-pressure liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [HPLC-MS]-grade water, 100% trifluoroacetic acid, and acetonitrile; Fluka) was then applied to each sample and allowed to cocrystallize at room temperature for 10 min. The prepared sample target was placed in the MicroFlex LT mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik), and the results were analyzed by MALDI Biotyper 3.0 software (Bruker Daltonik). A bacterial quality control strain (Escherichia coli DH5α) was included in each analysis. A single measurement was performed once for each culture isolate.

Data analyses.

MALDI Biotyper 3.0 software Realtime Classification was used to analyze the samples. In the Realtime Classification program, log score identification criteria are used as follows. A score between 2.000 and 3.000 is species-level identification, a score between 1.700 and 1.999 is genus-level identification, and a score that is below 1.700 is an unreliable identification. A Realtime Classification log score was given for each bacterial isolate sample for every condition from which it was isolated.

DNA isolation, PCR amplification and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing.

Genomic DNA was extracted from urine using previously validated protocols (4, 11). Briefly, 1 ml of urine was centrifuged at 13,500 rpm for 10 min and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of filter-sterilized buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8), 2 mM EDTA, 1.2% Triton X-100, and 20 μg/ml lysozyme and supplemented with 30 μl of filter-sterilized mutanolysin (5,000 U/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C and the lysates were processed through the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The DNA was eluted into 50 μl of AE buffer (pH 8.0) and stored at −20°C.

The variable region 4 (V4) of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene in each DNA sample was amplified and sequenced using a custom protocol developed for the Illumina MiSeq. Briefly, the 16S rRNA V4 region was amplified in a two-step nested PCR protocol using the universal 515F and 806R primers, which were modified to contain the Illumina adapter sequences. Amplicons were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Extraction- and PCR-negative controls were included in all steps to assess potential DNA contamination. DNA samples were diluted to 10 nM, pooled, and sequenced using the MiSeq personal sequencer platform using a paired-end 2× 251-bp reagent cartridge. Raw sequences were processed using the open-source program mothur, v1.31.2 (12). Paired ends were joined and contigs of incorrect length (<285 bp or >300 bp) and/or contigs that contained ambiguous bases were removed. Sequences were aligned using the SILVA database, and chimeric sequences were removed with UCHIME (13). Sequences were classified using a naive Bayesian classifier and the RDP 16S rRNA gene training set (v9). Sequences that could not be classified to the bacterial genus level were removed from analysis.

RESULTS

Culture results.

Sixty-five urine specimens (from 41 OAB patients and 24 controls) were examined using both the standard and EQUC techniques. Most (52/65 [80%]) grew bacterial species, with the majority of these (48/52 [92%]) reported as no growth at 103 by the clinical microbiology laboratory using the standard urine culture protocol.

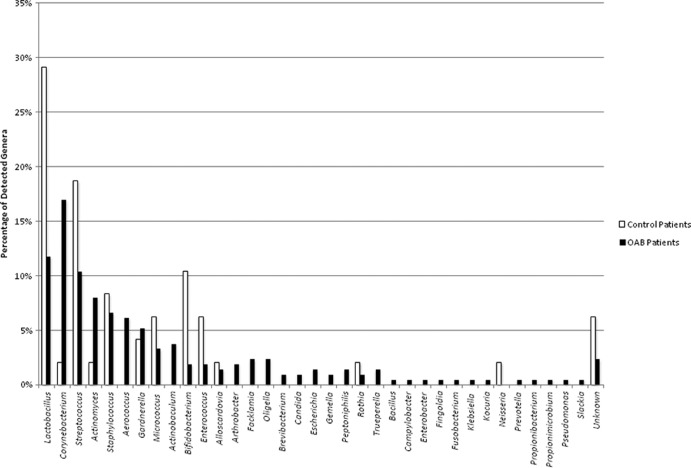

Using the EQUC technique, we isolated 35 different genera (Fig. 1) and 85 different species (Table 1), as identified by MALDI-TOF. To isolate these species, a combination of different culture and incubation conditions were required. Most of the bacteria isolated required either increased CO2 or anaerobic conditions for growth, along with prolonged incubation, and they often were present in numbers below the threshold of detection used in routine diagnostic urine culture protocols. With few exceptions, most bacteria were recovered on at least one of the primary plating media (data not shown). One case each of Enterococcus faecalis, Rothia dentocariosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis were recovered from thioglycolate broth only. A breakdown of the culture media and conditions for isolation of the 85 species is given in Table 1.

FIG 1.

Percentages of detection of each genus normalized to the total organism isolated from the OAB patients (black bars, n = 212 isolates from 34 of 41 participants) or the controls (white bars, n = 48 isolates from 18 of 24 participants).

TABLE 1.

List of bacterial species cultured in different conditionsa

| Organism (no. isolated) (n = 260) | Culture conditions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic, 35°C | Aerobic, 30°C | CO2, 35°C | Anaerobic, 35°C | Campy (6% O2, 10% CO2) 35°C | |

| Actinobaculum schaalii (7) | + | + | + | + | |

| Actinobaculum urinae (1) | + | ||||

| Actinomyces europaeus (2) | + | ||||

| Actinomyces graevenitzii (1) | + | ||||

| Actinomyces naeslundii (1) | + | ||||

| Actinomyces neuii (5) | + | + | + | ||

| Actinomyces odontolyticus (2) | + | + | + | ||

| Actinomyces oris (1) | + | ||||

| Actinomyces turicensis (3) | + | + | + | + | |

| Actinomyces urogenitalis (3) | + | + | |||

| Aerococcus sanguinicola (3) | HD | HD | + | ||

| Aerococcus urinae (9) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Aerococcus viridans (1) | + | ||||

| Alloscardovia omnicolens (4) | + | + | + | ||

| Arthrobacter cumminsii (4) | + | + | + | + | |

| Bacillus subtilis (1) | HD | + | |||

| Bifidobacterium bifidum (1) | + | + | |||

| Bifidobacterium breve (6) | + | + | + | ||

| Bifidobacterium dentium (1) | + | + | |||

| Bifidobacterium longum (1) | + | ||||

| Brevibacterium ravenspurgense (2) | + | + | |||

| Campylobacter ureolyticus (1) | HD | + | |||

| Candida glabrata (2) | + | + | + | ||

| Corynebacterium afermentans (2) | + | + | |||

| Corynebacterium amycolatum (3) | + | + | + | + | |

| Corynebacterium aurimucosum (3) | + | + | + | + | |

| Corynebacterium coyleae (7) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Corynebacterium freneyi (2) | + | + | + | ||

| Corynebacterium imitans (2) | + | + | + | ||

| Corynebacterium lipophile group F1 (4) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Corynebacterium matruchotii (1) | + | ||||

| Corynebacterium minutissimum (1) | + | + | |||

| Corynebacterium riegelii (4) | + | + | + | + | |

| Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum (2) | + | ||||

| Corynebacterium tuscaniense (3) | + | + | |||

| Corynebacterium urealyticum (3) | + | + | |||

| Enterobacter aerogenes (1) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Enterococcus faecalis (7) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Escherichia coli (3) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Facklamia hominis (5) | + | + | + | ||

| Finegoldia magna (1) | HD | + | |||

| Fusobacterium nucleatum (1) | HD | + | |||

| Gardnerella vaginalis (10) | + | + | + | + | |

| Gardnerella spp. (3) | + | + | + | + | |

| Gemella haemolysans (1) | + | ||||

| Gemella sanguinis (1) | + | ||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (1) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Kocuria rhizophila (1) | + | ||||

| Lactobacillus crispatus (6) | + | + | |||

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii (1) | + | + | |||

| Lactobacillus fermentum (1) | + | ||||

| Lactobacillus gasseri (12) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lactobacillus iners (6) | + | + | + | + | |

| Lactobacillus jensenii (10) | + | + | + | + | |

| Lactobacillus johnsonii (1) | + | ||||

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus (2) | + | + | |||

| Micrococcus luteus (9) | + | + | + | + | |

| Micrococcus lylae (1) | + | + | |||

| Neisseria perflava (1) | + | ||||

| Oligella urethralis (5) | + | ||||

| Peptoniphilus harei (3) | + | ||||

| Prevotella bivia (1) | + | + | |||

| Propionibacterium avidum (1) | + | ||||

| Propionimicrobium lymphophilum (1) | + | ||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1) | + | ||||

| Rothia dentocariosa (1) | + | + | |||

| Rothia mucilaginosa (2) | + | + | + | ||

| Slackia exigua (1) | + | ||||

| Staphylococcus capitis (1) | + | + | + | ||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (7) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus (2) | + | + | |||

| Staphylococcus hominis (2) | + | + | |||

| Staphylococcus lugdunensis (2) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Staphylococcus simulans (2) | + | + | + | ||

| Staphylococcus warneri (2) | + | + | |||

| Streptococcus agalactiae (1) | + | + | + | + | |

| Streptococcus anginosus (15) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus gallolyticus (1) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus gordonii (1) | + | + | + | ||

| Streptococcus parasanguinis (1) | + | ||||

| Streptococcus pneumonia/mitis/oralis (6) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus salivarius (3) | + | ||||

| Streptococcus sanguinis (2) | + | ||||

| Streptococcus vestibularis (1) | HD | + | + | ||

| Trueperella bernardiae (3) | + | + | |||

| Unclassified #1 (1) | + | + | |||

| Unclassified #2 (1) | + | + | + | ||

| Unclassified #3 (1) | + | ||||

| Unclassified #4 (1) | + | + | |||

| Unclassified #5 (1) | + | ||||

| Unclassified #6 (1) | + | + | |||

| Unclassified #7 (1) | + | ||||

| Unclassified #8 (1) | + | + | + | ||

The + symbol designates the environmental conditions from which the organism was isolated and identified; HD indicates that only high-dilution (1 μl) urine was plated for that condition and that no growth was observed. A blank space designates no growth in that condition for that particular organism using a low-dilution (100-μl) inoculum.

The most prevalent genera isolated were Lactobacillus (15%), followed by Corynebacterium (14%), Streptococcus (11.9%), Actinomyces (6.9%), and Staphylococcus (6.9%) (Fig. 1). Within each genus, the most frequently isolated species were Lactobacillus gasseri, Corynebacterium coyleae, Streptococcus anginosus, Actinomyces neuii, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Other genera commonly isolated include Aerococcus, Gardnerella, Bifidobacterium, and Actinobaculum. The numbers of isolated species within each genus are listed in Table 1.

Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, Actinomyces, and Bifidobacterium spp. were isolated from both OAB and control cohorts. In contrast, Aerococcus and Actinobaculum were isolated only from OAB patients (Fig. 1).

16S rRNA amplicon sequencing results.

To determine if the bacteria grown in culture (the microbiota) matched the bacterial DNA sequences (the microbiome) obtained from analysis of the same urine specimens, four OAB urine samples underwent 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. The majority of the bacterial species that were detected by the EQUC procedure also were detected by 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the same urine from the same patient (Table 2). For example, in the urine sample of patient OAB18, the EQUC detected Lactobacillus jensenii and Gardnerella vaginalis at >103 CFU/ml. The 16S rRNA sequencing of that same urine sample found that 86.6% of the sequences were classified as Lactobacillus and 13.0% of the sequences were classified as Gardnerella. In each urine sample, the cultured genera represent >80% of the sequences obtained. Sequencing detected additional genera that were not detected by culture (data not shown), suggesting that those organisms were not viable and/or were not cultivable under the conditions tested.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of cultured isolates to genera detected by 16S rRNA sequence in urine samples

| Urine | Isolate cultured | CFU/ml | % of sequences per sample (genus level classification) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OAB18 | Lactobacillus jensenii | >1,000 | 86.6 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | >1,000 | 13.0 | |

| OAB21 | Lactobacillus jensenii | 140 | 92.4a |

| Lactobacillus iners | 120 | ||

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 40 | 4.9 | |

| OAB23 | Gardnerella vaginalis | >1,000 | 80.0 |

| Rothia dentocariosa | Brothb | Not detected | |

| Streptococcus anginosus | 60 | 0.07 | |

| Aerococcus urinae | 50, 60 | 0.13 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Brothb | 0.001 | |

| OAB26 | Gardnerella vaginalis | 300 | 97.2 |

Sequence data cannot distinguish between species.

Cultured in thioglycolate broth; therefore, unable to determine starting CFU/ml.

DISCUSSION

In our previous report (4), we presented evidence of bacterial DNA (microbiome) in the bladders of adult women with and without lower urinary tract symptoms. In the present study, we have provided evidence of live bacteria in the adult female bladder and, importantly, demonstrated a correlation in matched urine samples between the bacteria isolated using our EQUC protocol and the bacterial sequences identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. These findings support our contentions that the urinary microbiome exists and that it is a reflection of living bacterial species that make up the resident flora (microbiota) in the adult female bladder.

These data support those of Khasriya and colleagues, who also found that expanded culture conditions detect diverse urinary bacteria missed by routine diagnostic laboratory testing methods (7). Furthermore, our results often parallel those of their previous study, which found Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Lactobacillus to be commonly isolated genera, results that closely match our findings. However, our results were not identical. For example, they isolated Actinomyces, Aerococcus, Bifidobacterium, and Gardnerella less frequently than we did. These differences might result from the relatively small sample sizes of both studies or from procedural differences. For example, we plated urine directly without centrifugation, while Khasriya and coauthors isolated bacteria from centrifuged urine sediments, which had been prepared from catheterized and voided urine specimens collected from patients with chronic lower urinary tract symptoms and healthy controls. Since the sedimentation procedure was enriched for bacteria associated with urothelial cells, the differences in results could reflect differences in the ability of certain bacteria to associate tightly with urothelial cells. Further studies are required to determine if this is true. Finally, Khasriya and coworkers did not report the recovery of Actinobaculum, an emerging uropathogen (14). Since these authors did not perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing of their sedimented urine samples, they could not know if Actinobaculum might have been present in their samples but could not grow in culture using their protocol.

Similar results might be found in men. Using 16S rRNA gene sequencing to identify bacteria in first-catch urine specimens collected from asymptomatic men, Nelson and colleagues showed that the overwhelming majority of the urine sequences corresponded to a few abundant genera. In their analyses, 72 genera were detected in total, with four genera (namely, Lactobacillus, Corynebacterium, Streptococcus, and Sneathia) accounting for approximately 50% of the total urine sequences. They concluded that these organisms represented the urinary microbiome of men (9). However, culture-based studies of the urine samples were not included in their analyses. EQUC procedures could be used to determine if the sequences identified in the urine samples represent living bacteria.

In our previously reported study (4), we used 16S rRNA gene sequencing to demonstrate evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder and we questioned the “sterile urine” dogma. Our current study demonstrates that urine contains communities of living bacteria that comprise a resident female urine microbiota. More specifically, we have shown that the bacterial sequences detected in the adult female bladder by 16S rRNA sequencing represent living organisms that can be grown when culture conditions are modified to include plating of larger quantities of urine, incubating in an atmosphere of increased CO2, and extending incubation to 48 h.

Further studies are needed to elucidate the role of the urinary microbiota in health and disease, and the complementary features of EQUC and 16S rRNA sequencing will facilitate those efforts. Each technique possesses distinct advantages and disadvantages. Deep 16S rRNA sequencing is a high-throughput technology that facilitates rapid screening at great depth, permitting researchers to obtain a broad and deep overview of the microbiota without the need to cultivate. However, the advantage provided by the speed and depth of the high-throughput technology is balanced by the inability to reliably identify bacteria below the genus level. In contrast, EQUC can capture the bacterium, but only if it can be cultivated. However, any isolated bacterium can be identified to the species level by MALDI-TOF. With the bacterium in hand, full-scale characterization is now possible, including the ability to sequence its genome, which could identify the organism to the strain level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Bozena Zemaitaitis for her help in processing the urine samples.

We acknowledge the following unrestricted research funding sources: Falk Foundation Research Award, Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine Research Funding Committee, and Doyle Family Philanthropic Support (to L. Brubaker and A. J. Wolfe). This study was supported in part by Astellas Medical and Scientific Affairs and is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01642277. The MicroFlex LT mass spectrometer used in this study was furnished by Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Leipzig, Germany.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Stewart W, Van Rooyen J, Cundiff G, Abrams P, Herzog A, Corey R, Hunt T, Wein A. 2003. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J. Urol. 20:327–336. 10.1007/s00345-002-0301-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nitti VW, Kopp Z, Lin AT, Moore KH, Oefelein M, Mills IW. 2010. Can. we predict which patient will fail drug treatment for overactive bladder? A think tank discussion. Neurourol. Urodyn. 29:652–657. 10.1002/nau.20910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson DE, Dong Q, Van der Pol B, Toh E, Fan B, Katz BP, Mi D, Rong R, Weinstock GM, Sodergren E, Fortenberry JD. 2012. Bacterial communities of the coronal sulcus and distal urethra of adolescent males. PLoS One 7:e36298. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe AJ, Toh E, Shibata N, Rong R, Kenton K, Fitzgerald M, Mueller ER, Schreckenberger P, Dong Q, Nelson DE, Brubaker L. 2012. Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:1376–1383. 10.1128/JCM.05852-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouts DE, Pieper R, Szpakowski S, Pohl H, Knoblach S, Suh MJ, Huang ST, Ljungberg I, Sprague BM, Lucas SK, Torralba M, Nelson KE, Groah SL. 2012. Integrated next-generation sequencing of 16S rDNA and metaproteomics differentiate the healthy urine microbiome from asymptomatic bacteriuria in neuropathic bladder associated with spinal cord injury. J. Transl. Med. 10:174. 10.1186/1479-5876-10-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddiqui H, Nederbragt AJ, Lagesen K, Jeansson SL, Jakobsen KS. 2011. Assessing diversity of the female urine microbiota by high throughput sequencing of 16S rDNA amplicons. BMC Microbiol. 11:244. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khasriya R, Sathiananthamoorthy S, Ismail S, Kelsey M, Wilson M, Rohn JL, Malone-Lee J. 2013. Spectrum of bacterial colonization associated with urothelial cells from patients with chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:2054–2062. 10.1128/JCM.03314-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis DA, Brown R, Williams J, White P, Jacobson SK, Marchesi JR, Drake MJ. 2013. The human urinary microbiome; bacterial DNA in voided urine of asymptomatic adults. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 3:41. 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson DE, Van Der Pol B, Dong Q, Revanna KV, Fan B, Easwaran S, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Diao L, Fortenberry JD. 2010. Characteristic male urine microbiomes associate with asymptomatic sexually transmitted infection. PLoS One 5:e14116. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong Q, Nelson DE, Toh E, Diao L, Gao X, Fortenberry JD, Van der Pol B. 2011. The microbial communities in male first catch urine are highly similar to those in paired urethral swab specimens. PLoS One 6:e19709. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan S, Cohen DB, Ravel J, Abdo Z, Forney LJ. 2012. Evaluation of methods for the extraction and purification of DNA from the human microbiome. PLoS One 7:e33865. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. 2013. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:5112–5120. 10.1128/AEM.01043-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. 2011. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27:2194–2200. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cattoir V. 2012. Actinobaculum schaalii: review of an emerging uropathogen. J. Infect. 64:260–267. 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]