Abstract

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA), an important multidrug-resistant organism of public health concern, has been infrequently identified in the United States since 2002. All previous VRSA isolates belonged to clonal complex 5, a lineage associated primarily with health care. This report describes the most recent (13th) U.S. VRSA isolate, the first to be community associated.

CASE REPORT

In March 2012, a 70-year-old man with hypertension and diabetes was admitted to a Delaware hospital for treatment of a chronic foot wound and suspected osteomyelitis. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was isolated from bacterial cultures (not available for further study), for which he was prescribed a 6-week course of vancomycin. After a 9-day hospital stay, he was transferred to a long-term-care facility (LTCF) to complete the intravenous antibiotic regimen. Five weeks later, he was discharged on oral doxycycline to home, where he lived alone and performed his own dressing changes and wound care. The wound continued to drain, and additional wound cultures collected during a follow-up at a podiatry clinic in June, 2 months postdischarge, grew MRSA resistant to vancomycin (MIC of 256 μg/ml).

The vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) isolate was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where it was confirmed by broth microdilution (1) as S. aureus resistant to cefoxitin, vancomycin, clindamycin, erythromycin, levofloxacin, and tetracycline; intermediately resistant to doxycycline and minocycline; and susceptible to chloramphenicol, daptomycin, gentamicin, linezolid, rifampin, tigecycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Table 1 and data not shown). PCR confirmed the presence of vanA, which has been identified in all previous U.S. VRSA isolates (2–5). This isolate was confirmed as the 13th VRSA identified to date in the United States, and the 3rd VRSA isolate from Delaware (U.S. VRSA isolates 11, 12, and 13 are from Delaware).

TABLE 1.

MICs (interpretations) for bacterial isolates associated with U.S. VRSA isolate 13

| Isolate | Source | MIC inμg/ml (interpretation)a |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | Cefoxitin | Clindamycin | Doxycycline | Erythromycin | Levofloxacin | Minocycline | Tetracycline | SXT | ||

| VRSA | Foot wound | 256 (R) | 16 (R) | >16 (R) | 8 (I) | >8 (R) | 8 (R) | 8 (I) | >16 (R) | ≤0.5/9.5 (S) |

| MRSA | Rectum | 1 (S) | 8 (R) | >16 (R) | 8 (I) | >8 (R) | >16 (R) | 8 (I) | >16 (R) | >8/152 (R) |

| MRSA | Nares | 1 (S) | 8 (R) | ≤0.25 (S) | ≤1 (S) | 0.5 (S) | >16 (R) | 0.12 (S) | ≤1 (S) | >8/152 (R) |

| E. faecalis | Rectum | 512 (R) | NA | NA | 8 (I) | NA | 0.5 (S) | NA | NA | NA |

SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; R, resistant; I, intermediate; S, susceptible; NA, not applicable.

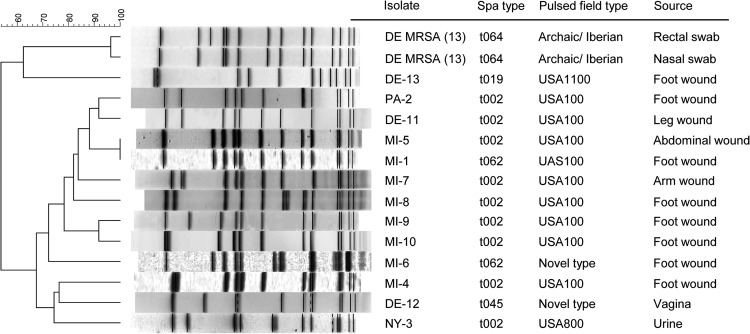

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (6, 7) and spa typing (8; http://spaserver.ridom.de/) demonstrated that VRSA isolate 13 belongs to types USA1100 and t019, respectively (Fig. 1). It contains a type IV SCCmec element and is Panton-Valentine leukocidin negative (6). These data place VRSA isolate 13 in staphylococcal clonal complex 30 (CC30), a lineage associated with MRSA from community settings (9), and differentiate it from the health care-associated strain background of VRSA isolates 1 to 12, all of which belong to staphylococcal CC5 (Fig. 1) (10).

FIG 1.

PFGE of VRSA isolates 1 to 13 and two MRSA isolates associated with VRSA isolate 13.

Upon confirmation of the VRSA phenotype, additional patient cultures for VRSA, MRSA, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) were performed. The foot wound had healed, but nasal and perirectal swabs were collected and cultured at CDC. Each swab was enriched overnight in salt broth, subcultured on mannitol salt agar (11) and CHROMagar VRE (DRG, Moutainside, NJ), and examined for S. aureus or VRE. S. aureus was confirmed by positive StaphAurex (Remel, Lenexa, KS), tube coagulase, Vogues-Proskauer, mannitol, and trehalose reactions; Enterococcus isolates were identified with the Vitek2 system (bioMérieux, St. Louis, MO). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by broth microdilution with panels prepared in house (12).

MRSA was isolated from nasal and rectal swabs, and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis was isolated from the rectal swab; no VRSA bacteria were detected at either site. The MRSA isolates from both sites were characterized as PFGE type Archaic/Iberian and spa type t064 (CC8) and thus could not be implicated as direct progenitors of VRSA isolate 13. Although the rectal and nasal MRSA isolates were closely related, they displayed different antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, and only one (rectal) isolate carried PCR markers indicative of a pSK41-like plasmid (Tables 1 and 2). The vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis isolate was found to contain vanA, as well as repR, a marker of Inc18-type plasmids (13) (Table 2). The VRSA isolate was not PCR positive for pSK41 markers but, like the putative VRE donor, was positive for the Inc18-like plasmid marker repR.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of U.S. VRSA cases and associated isolates

| Case no., state, yr, and isolate | Site of isolation | Presence of marker for plasmid: |

PFGE type | spa type | Clonal complex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inc18 |

pSK41 |

||||||||

| traA | repR | traE | repA | traK | |||||

| 1, MI, 2002 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Foot wound | −b | − | +c | + | + | USA100 | t062 | CC5 |

| VRa E. faecalis | Foot wound | + | + | NAd | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| MRSA | Nares | NA | NA | + | + | + | USA100 | t062 | CC5 |

| 2, PA, 2002, VRSA | Foot | − | − | − | − | + | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| 3, NY, 2004 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Urine | − | − | − | − | − | USA800 | t002 | CC5 |

| VR E. faecium | Rectum | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| MRSA | Rectum | NA | NA | + | + | + | USA800 | t002 | CC5 |

| 4, MI, 2005 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Toe wound | + | + | − | − | − | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| VR E. faecalis | Rectal swab | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 5, MI, 2005 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Abdominal wound | + | + | − | − | − | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| VR E. faecalis | Abdominal wound | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| MRSA | Abdominal wound | NA | NA | − | − | − | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| 6, MI, 2006 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Wound | − | − | − | − | − | Unnamed | t062 | CC5 |

| VR E. faecalis | Rectum | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| VR E. avium | Rectum | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7, MI, 2006 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Left elbow wound | + | − | − | − | − | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| MRSA | Left elbow wound | NA | NA | − | − | − | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| 8, MI, 2007 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Foot wound | − | − | + | + | + | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| MRSA | Foot wound | NA | NA | + | + | + | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| 9, MI, 2007 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Foot wound | − | − | + | + | + | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| VR E. faecalis | Foot wound | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 10, MI, 2010 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Foot wound | + | − | − | − | − | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| E. faecalis | Foot wound | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| VR E. faecalis | Perirectal area | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| VR E. gallinarum | Groin | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| VR E. raffinosus | Rectum | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| VR E. faecium | Groin | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| MRSA | Rectum | NA | NA | − | − | − | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| 11, DE, 2010 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Wound | + | + | + | + | + | USA100 | t002 | CC5 |

| VR E. faecalis | Wound | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 12, DE, 2010 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Vagina | − | − | − | − | − | Unnamed | t045 | CC5 |

| VR E. gallinarum | Rectum | − | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 13, DE, 2012 | |||||||||

| VRSA | Foot wound | − | + | − | − | − | USA1100 | t019 | CC30 |

| VR E. faecalis | Rectum | − | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| MRSA | Rectum | NA | NA | + | + | − | Archaic/Iberian | t064 | CC8 |

| MRSA | Nares | NA | NA | − | − | − | Archaic/Iberian | t064 | CC8 |

VR, vancomycin resistant.

−, negative.

+, positive.

NA, not applicable.

Persons deemed to be at increased risk for VRSA acquisition included the patient's LTCF roommate and infectious disease physician, the patient's primary care provider, and the podiatrist who cultured and treated the patient's VRSA-positive wound. Because of the 2-month interval between LTCF discharge and VRSA culture, the patient's roommate was no longer a resident of the LTCF and could not be located, but review of the roommate's medical record during the 2 weeks following the discharge of the case patient revealed that urine, respiratory, and blood cultures during this time were negative. Cultures were not collected from the primary care provider or infectious disease physician, since neither had any contact with the patient between April and June 2012. The podiatrist stated that he was the only person in his office to perform wound care, and he refused to be cultured for surveillance.

The first U.S. case of vanA-mediated vancomycin resistance in S. aureus was recognized in 2002 in an isolate from a foot wound of a diabetic patient who had received long-term vancomycin therapy. Since that time, VRSA has been viewed as a potential clinical and public health threat, although the widespread emergence of these organisms has not been realized (Fig. 1). None of the U.S. VRSA isolates has been transmitted beyond the patient from whom it was cultured, and none has definitively contributed to patient morbidity or mortality, despite the fact that most VRSA strains have arisen from successful MRSA parent lineages that are both widespread and pathogenic.

Each of the 13 U.S. VRSA isolates has arisen from independent transfer of the vanA gene cluster on a conjugative element from a VRE donor to a MRSA recipient (4, 8, 14). Despite the fact that VRSA isolate 13 represents the third VRSA isolate recovered from Delaware during a 3-year period, both microbiologic and epidemiologic data (Fig. 1 and Table 2; CDC unpublished data) point to independent genetic events rather than transfer of VRSA between patients. VRSA appears to arise in vivo in settings of polymicrobial infections where VRE and MRSA are both present. For several VRSA cases, presumed donor VRE and/or recipient MRSA strains were recovered and characterized. Eight of 10 VRE strains associated with VRSA cases carried the vanA operon on an Inc18-like plasmid (Table 2) (4) and could transfer vanA to a naive MRSA donor in vitro (15). Although Enterococcus faecium is the most common species of VRE in the United States, most VRSA isolates have been associated with species other than E. faecium. Among the 10 VRSA cases in which an associated VRE strain was recovered, only two E. faecium strains were identified, and neither contained an Inc18-like plasmid (Table 2) (4). Inc18-like plasmids are uncommon among VRE strains in the United States, but they appear over five times more commonly in Michigan than in other states (13). This may, in part, explain why eight (62%) U.S. VRSA cases have occurred in Michigan.

The recipient strain also plays a significant role in the generation of VRSA. In VRSA isolate 1, a Tn1546 transposon carrying the vanA operon was found inserted into a pSK41-like S. aureus conjugative plasmid (14). In addition to being important vectors for antibiotic resistance genes (16, 17), pSK41-like plasmids also appear to be important as facilitators of DNA transfer between Enterococcus donors and S. aureus recipients (15). PCR markers of pSK41-like plasmids were associated with seven VRSA cases; four of seven MRSA isolates from VRSA case patients carried pSK41 markers, as did three of six VRSA isolates that lacked an associated MRSA strain (Table 2). Thus, the prevalence of pSK41-like plasmids among different MRSA strains may impact the lineages in which VRSA arises. A recent study of outpatients with lower-extremity wounds found that although pSK41-like plasmids had a low prevalence (5.4%), they were present among methicillin-susceptible S. aureus and MRSA strains from health care and community-associated lineages (18). That recovery of MRSA bacteria in association with VRSA isolate 13 that were not immediate progenitors to the VRSA is unusual. The presence of a pSK41-like plasmid in the rectal Archaic/Iberian isolate suggests that it may have been a cocolonizer that facilitated conjugation between VRE and the VRSA progenitor, USA1100 MRSA.

Prior to this case, all U.S. VRSA isolates had been in the S. aureus CC5 lineage. This may reflect the fact that MRSA and VRE coinfection (or cocolonization) is more likely in patients with health care exposures, among whom health care-associated MRSA strains are common. CC5 is the dominant S. aureus lineage among health care-associated MRSA strains, encompassing both the USA100 and USA800 PFGE types, as well as related unnamed strains. The case patient described here had significant health care exposure, and this infection is clearly health care associated, but the USA1100/t019/CC30 lineage to which VRSA isolate 13 belongs is usually associated with community-acquired infections (9, 19). Both of the MRSA strains recovered here belong to the Archaic-Iberian/t064/CC8 lineage, a strain most common in Europe and recently linked to nosocomial infections in horses (20) but relatively uncommon in the United States (6). Neither USA1100 nor the Archaic-Iberian lineage has previously been associated with VRSA. Although the VRSA isolate 13 case patient had been an outpatient for approximately 2 months prior to the culture of VRSA, vancomycin exposure occurred primarily during his residence in an LTCF. However, the finding of MRSA containing pSK41-like plasmids among community-associated lineages (USA 300) in outpatients with chronic wounds (18) supports the possibility that vanA could transfer to community-associated MRSA strains in outpatient settings.

VRSA isolates have been infrequently reported from other countries, including India, Iran, Pakistan (21), and most recently Portugal (22), and the possibility of significant dissemination of VRSA is an important concern for health care providers and for public health. The potential emergence of vanA-mediated vancomycin resistance among MRSA strains that are well adapted to transmission in community settings (e.g., USA300) could potentially increase the health risks associated with VRSA. Although it is not completely clear where the progenitor USA1100 MRSA was acquired, given the patient's multiple health care exposures, it is entirely possible that this strain was acquired in a health care setting. Our understanding of VRSA development suggests that polymicrobial infections with appropriate progenitor strains such as VRE and MRSA, which are typically health care associated, is an important prerequisite for the creation of VRSA, although additional biological barriers to VRSA formation likely exist. The many health care exposures of the patient described here clearly classify this as a health care-associated community onset case, but the most recent emergence of vancomycin resistance in a USA1100 strain suggests that strains typically thought of as health care associated are not the only ones that can acquire vanA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The findings and conclusions in this article are ours and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The use of trade names is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the Department of Health and Human Services or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.CLSI 2012. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-second informational supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002. Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomycin—United States, 2002. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:565–567 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5126a1.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—Pennsylvania, 2002. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:902 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5140a3.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kos VN, Desjardins CA, Griggs A, Cerqueira G, Van Tonder A, Holden MT, Godfrey P, Palmer KL, Bodi K, Mongodin EF, Wortman J, Feldgarden M, Lawley T, Gill SR, Haas BJ, Birren B, Gilmore MS. 2012. Comparative genomics of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains and their positions within the clade most commonly associated with methicillin-resistant S. aureus hospital-acquired infection in the United States. mBio 3(3)e00112-1. 10.1128/mBio.00112-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sievert DM, Rudrik JT, Patel JB, McDonald LC, Wilkins MJ, Hageman JC. 2008. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States, 2002-2006. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:668–674. 10.1086/527392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limbago B, Fosheim GE, Schoonover V, Crane CE, Nadle J, Petit S, Heltzel D, Ray SM, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Schaffner W, Mu Y, Fridkin SK. 2009. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected in 2005 and 2006 from patients with invasive disease: a population-based analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1344–1351. 10.1128/JCM.02264-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDougal LK, Steward CD, Killgore GE, Chaitram JM, McAllister SK, Tenover FC. 2003. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: establishing a national database. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5113–5120. 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5113-5120.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, Rothganger J, Claus H, Turnwald D, Vogel U. 2003. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5442–5448. 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5442-5448.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson DA, Kearns AM, Holmes A, Morrison D, Grundmann H, Edwards G, O'Brien FG, Tenover FC, McDougal LK, Monk AB, Enright MC. 2005. Re-emergence of early pandemic Staphylococcus aureus as a community-acquired meticillin-resistant clone. Lancet 365:1256–1258. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74814-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enright MC, Robinson DA, Randle G, Feil EJ, Grundmann H, Spratt BG. 2002. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7687–7692. 10.1073/pnas.122108599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAllister SK, Albrecht VS, Fosheim GE, Lowery HK, Peters PJ, Gorwitz R, Guest JL, Hageman J, Mindley R, McDougal LK, Rimland D, Limbago B. 2011. Evaluation of the impact of direct plating, broth enrichment, and specimen source on recovery and diversity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates among HIV-infected outpatients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:4126–4130. 10.1128/JCM.05323-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CLSI 2012. M07-A9—methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard—ninth edition. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu W, Murray PR, Huskins WC, Jernigan JA, McDonald LC, Clark NC, Anderson KF, McDougal LK, Hageman JC, Olsen-Rasmussen M, Frace M, Alangaden GJ, Chenoweth C, Zervos MJ, Robinson-Dunn B, Schreckenberger PC, Reller LB, Rudrik JT, Patel JB. 2010. Dissemination of an Enterococcus Inc18-like vanA plasmid associated with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4314–4320. 10.1128/AAC.00185-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weigel LM, Clewell DB, Gill SR, Clark NC, McDougal LK, Flannagan SE, Kolonay JF, Shetty J, Killgore GE, Tenover FC. 2003. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 302:1569–1571. 10.1126/science.1090956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu W, Clark N, Patel JB. 2013. pSK41-like plasmid is necessary for Inc18-like vanA plasmid transfer from Enterococcus faecalis to Staphylococcus aureus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:212–219. 10.1128/AAC.01587-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDougal LK, Fosheim GE, Nicholson A, Bulens SN, Limbago BM, Shearer JE, Summers AO, Patel JB. 2010. Emergence of resistance among USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing invasive disease in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3804–3811. 10.1128/AAC.00351-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berg T, Firth N, Apisiridej S, Hettiaratchi A, Leelaporn A, Skurray RA. 1998. Complete nucleotide sequence of pSK41: evolution of staphylococcal conjugative multiresistance plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 180:4350–4359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tosh P, Agolory S, Strong BL, VerLee K, Finks J, Hayakawa K, Chopra T, Kaye KS, Gilpin N, Carpenter CF, Haque NZ, Lamarato LE, Zervos MJ, Albrecht VS, McAllister SK, Limbago B, MacCannell DR, McDougal LK, Kallen AJ, Guh AY. 2013. Prevalence and risk factors of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) precursor organism colonization among patients with chronic lower extremity wounds in southeastern Michigan. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 34:954–960. 10.1086/671735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diep BA, Carleton HA, Chang RF, Sensabaugh GF, Perdreau-Remington F. 2006. Roles of 34 virulence genes in the evolution of hospital- and community-associated strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 193:1495–1503. 10.1086/503777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Duijkeren E, Moleman M, Sloet van Oldruitenborgh-Oosterbaan MM, Multem J, Troelstra A, Fluit AC, van Wamel WJ, Houwers DJ, de Neeling AJ, Wagenaar JA. 2010. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in horses and horse personnel: an investigation of several outbreaks. Vet. Microbiol. 141:96–102. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moravvej Z, Estaji F, Askari E, Solhjou K, Naderi Nasab M, Saadat S. 2013. Update on the global number of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) strains. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 42:370–371. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melo-Cristino J, Resina C, Manuel V, Lito L, Ramirez M. 2013. First case of infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Lancet 382:205. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61219-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]