Abstract

Enterococcal implant-associated infections are difficult to treat because antibiotics generally lack activity against enterococcal biofilms. We investigated fosfomycin, rifampin, and their combinations against planktonic and adherent Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 19433) in vitro and in a foreign-body infection model. The MIC/MBClog values were 32/>512 μg/ml for fosfomycin, 4/>64 μg/ml for rifampin, 1/2 μg/ml for ampicillin, 2/>256 μg/ml for linezolid, 16/32 μg/ml for gentamicin, 1/>64 μg/ml for vancomycin, and 1/5 μg/ml for daptomycin. In time-kill studies, fosfomycin was bactericidal at 8× and 16× MIC, but regrowth of resistant strains occurred after 24 h. With the exception of gentamicin, no complete inhibition of growth-related heat production was observed with other antimicrobials on early (3 h) or mature (24 h) biofilms. In the animal model, fosfomycin alone or in combination with daptomycin reduced planktonic counts by ≈4 log10 CFU/ml below the levels before treatment. Fosfomycin cleared planktonic bacteria from 74% of cage fluids (i.e., no growth in aspirated fluid) and eradicated biofilm bacteria from 43% of cages (i.e., no growth from removed cages). In combination with gentamicin, fosfomycin cleared 77% and cured 58% of cages; in combination with vancomycin, fosfomycin cleared 33% and cured 18% of cages; in combination with daptomycin, fosfomycin cleared 75% and cured 17% of cages. Rifampin showed no activity on planktonic or adherent E. faecalis, whereas in combination with daptomycin it cured 17% and with fosfomycin it cured 25% of cages. Emergence of fosfomycin resistance was not observed in vivo. In conclusion, fosfomycin showed activity against planktonic and adherent E. faecalis. Its role against enterococcal biofilms should be further investigated, especially in combination with rifampin and/or daptomycin treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of implant-associated infections is challenging because bacteria form biofilms on implant surfaces (1). Microorganisms in a biofilm are up to 1,000-fold more resistant to antibiotics than their planktonic counterparts (2). Thus, successful treatment requires antimicrobials that retain activity against adherent and metabolically less active bacteria and thus persist during the stationary growth phase (3).

Enterococci are an important global cause of health care-associated infections, as they are increasingly associated with endocarditis, urinary tract, intra-abdominal, catheter-related, surgical site, and central nervous system infections (4). In addition, enterococci have emerged as multidrug-resistant pathogens, causing infections in patients with intravascular or extravascular implants (5, 6). Several virulence and genetic factors involved in the immunity and pathogenesis of enterococcal infections have been identified (7).

Enterococci cause 3 to 10% of prosthetic joint infections, and the treatment of these infections is associated with high failure rates, mainly due to antimicrobial tolerance and the slow bactericidal activities of β-lactam antibiotics and glycopeptides (8). While rifampin combination treatment has been established for staphylococcal implant-associated infections (9), an optimal treatment for enterococcal infections has not been determined. Despite gentamicin-containing regimens showing activity against Enterococcus faecalis biofilms in an experimental foreign-body infection model, the failure rates remain high (10).

Fosfomycin is a bactericidal agent with a broad spectrum of activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative microorganisms, including E. faecalis (11). Although for fosfomycin the main drawback is the high rate of in vitro emergence of resistance, which limits its use in the clinic, the rate of in vivo resistance remains low (12, 13). Despite fosfomycin's main use for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections, activities against biofilms and bone infections have also been demonstrated, as fosfomycin penetrates well into soft tissue and bone tissue (14, 15).

In this study, we investigated the activities of fosfomycin, rifampin, gentamicin, ampicillin, vancomycin, daptomycin, linezolid, and their combinations against planktonic and adherent E. faecalis in vitro and in a guinea pig foreign-body infection model. This animal model has been previously used for the evaluation of antimicrobial agents against biofilms and has been predictive for clinical outcomes in implant-associated infections (10, 16–20).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study organism.

The biofilm-forming E. faecalis ATCC 19433 strain was used for all in vitro and in vivo experiments (21). Bacteria were stored in a cryovial bead preservation system (Microbank; Pro-Lab Diagnostics, Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada) at −80°C. An inoculum was prepared by spreading one cryovial bead on a blood agar plate and incubating the plate overnight at 37°C. One colony was resuspended in 5 ml tryptic soy broth (TSB) and incubated at 37°C without shaking. Overnight cultures were then adjusted to a turbidity of 0.5 McFarland, which corresponded to ≈5 × 107 CFU/ml.

Antimicrobial agents.

Fosfomycin was provided as purified powder by the manufacturer (InfectoPharm, Heppenheim, Germany). A 50-mg/ml stock solution was prepared in sterile and pyrogen-free 0.9% saline. Daptomycin for injection was supplied by the manufacturer (Novartis Pharma Schweiz, Bern, Switzerland). A stock solution of 50 mg/ml was prepared in sterile and pyrogen-free 0.9% saline. Vancomycin was supplied as 10-mg powder ampoules (Teva Pharma, Aesch, Switzerland). A stock solution of 50 mg/ml was prepared in sterile and pyrogen-free 0.9% saline. Rifampin (Sandoz, Steinhausen, Switzerland) was prepared as a 60-mg/ml stock solution in sterile water. Ampicillin was provided as a purified powder by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and a 5-mg/ml stock solution was prepared in sterile water.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The MICs and the logarithmic MBC (MBClog) values for fosfomycin, ampicillin, rifampin, gentamicin, linezolid, daptomycin, and vancomycin were determined by the broth macrodilution method in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB), according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (22). An inoculum of ∼3 × 105 CFU/ml was used. Two-fold serial dilutions of each antimicrobial agent were prepared in 2 ml Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) in plastic tubes and incubated for 18 h at 37°C. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that completely inhibited visible growth. After the incubation, all tubes without visible growth were vigorously vortexed and incubated for an additional 4 h at 37°C without shaking. Aliquots of 100 μl were plated on blood agar plates, and the numbers of bacteria were determined. The MBClog was defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration that killed ≥99.9% of the initial bacterial count (i.e., ≥3 log10 CFU/ml) in 24 h. For bacteria in the stationary phase, MBCstat was determined in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with the addition of 0.1% TSB. Media were supplemented with 25 mg/liter glucose-6-phosphate for testing of fosfomycin and with 50 mg/liter Ca2+ for testing of daptomycin. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Time-kill studies.

The activities of fosfomycin, rifampin, ampicillin, and linezolid were investigated in time-kill studies performed with cells in the logarithmic growth phase. The tests were performed in plastic tubes in a final volume of 10 ml CAMHB and were further incubated at 37°C. At time points of 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h, 1-ml aliquots were sampled and washed with 0.9% saline solution in order to prevent the antibiotic carryover effect. Ten-fold dilutions were then plated on Muller-Hinton agar, and the numbers of CFU were determined. Medium without antibiotics was used as the growth control. Bactericidal activity was defined as a ≥99.9% (i.e., ≥3-log10 CFU/ml) reduction of the initial bacterial count after 24 h. The initial inoculum was ∼5 × 105 CFU/ml, and the medium used was CAMHB supplemented with glucose-6-phosphate at 25 mg/liter for the fosfomycin studies.

Microcalorimetry testing of antimicrobial activity against planktonic and adherent E. faecalis.

A 48-channel isothermal microcalorimeter (thermal activity monitor, model 3102 TAM III; TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) was used as described for previous studies (23–26). Microcalorimetry is a highly sensitive method for assessment of bacterial growth throughout the measurements of bacterial heat production over time (the lower limit of heat flow detection is 0.25 μW). The antimicrobial activity against planktonic and adherent E. faecalis can be quantitatively assessed in real time by the impact on the heat flow curve, i.e., the delay of heat production, reduction of peak heat flow, and total heat. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

For planktonic E. faecalis, microcalorimetry ampoules containing CAMHB with different concentrations of each tested antibiotic were inoculated with a standard inoculum size (6.7 × 105 CFU/ml). Media were supplemented with 25 mg/liter glucose-6-phosphate for fosfomycin and 50 mg/liter Ca2+ for daptomycin testing. The heat flow was recorded during 24 h, and the results were plotted as the heat flow (in microwatts) versus time. The minimal heat inhibition concentration (MHIC) was defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration that inhibited heat production during 24 h.

For E. faecalis biofilms, porous sintered glass beads (diameter, 4 mm; pore size, 60 μm; surface area, approximately 60 cm2) were incubated in CAMHB, which was inoculated with 2 to 3 colonies of E. faecalis and incubated at 37°C for 3 h (early biofilm) and 24 h (mature biofilm). Then, beads were washed three times with sterile 0.9% saline to remove planktonic bacteria and exposed to serial dilutions of fosfomycin, rifampin, ampicillin, gentamicin, linezolid, daptomycin, or vancomycin in 1 ml of CAMHB and incubated for a further 24 h at 37°C. CAMHB was supplemented with 25 mg/liter glucose-6-phosphate for fosfomycin testing and with 50 mg/liter Ca2+ for daptomycin testing. After antimicrobial exposure, beads were rinsed three times with 0.9% saline and placed in microcalorimetry ampoules containing 3 ml of CAMHB. Sterile beads served as a negative control. Heat production was recorded for 24 h to detect recovering bacteria. The minimal biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC) was defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration that killed biofilm bacteria on beads and led to an absence of regrowth after 24 h of incubation in the microcalorimeter.

Animal model.

A previously described foreign-body infection model in guinea pigs was used (27). Experiments were performed according to the Swiss veterinary law regulations. Male albino guinea pigs (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) were used and their well-being was checked daily, and the experiments were started when the animals weighed at least 450 g. Briefly, four sterile polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) cages (32 mm by 10 mm) with 130 regularly spaced perforations 1 mm in diameter (Angst-Pfister, Zurich, Switzerland) were subcutaneously implanted under aseptic conditions in the flanks of the guinea pigs. After the complete healing of the surgical wounds, which took approximately 2 weeks, the sterility of the cages was verified by culturing aspirated cage fluid on blood agar plates. Contaminated cages were excluded from the experiments.

Antimicrobial treatment regimens.

Cages were infected by percutaneous injection of 200 μl containing 5.9 × 104 CFU of E. faecalis. Before the start of treatment, the infection was determined by quantitative culture of aspirated cage fluid. Three hours after infection, antimicrobial treatment was initiated (day 1). Three animals were randomized into each of the following treatment groups (with 4 cages per animal): untreated (control) group, fosfomycin (250 mg/kg), rifampin (12.5 mg/kg), gentamicin (10 mg/kg) plus fosfomycin (250 mg/kg), daptomycin (40 mg/kg) plus fosfomycin (250 mg/kg), daptomycin (40 mg/kg) plus rifampin (12.5 mg/kg), vancomycin (15 mg/kg) plus fosfomycin (250 mg/kg), and vancomycin (15 mg/kg) plus rifampin (12.5 mg/kg). All antimicrobials were administered intraperitoneally every 12 h, with the exception of daptomycin, which was given once daily. The treatment was administered for 4 days. The dosing regimens for all tested antimicrobials were chosen according to results of pharmacokinetic experimental studies that mimicked drug concentrations in humans (14, 28–30).

Antimicrobial activities on planktonic E. faecalis in the animal model.

To determine the activities of antimicrobials on planktonic E. faecalis, each cage fluid was aspirated during treatment (preceding the last dose, i.e., day 4) and 5 days after completion of treatment (i.e., day 9). The treatment efficacy against planktonic bacteria was assessed based on the reduction of bacterial counts in the cage fluid (expressed as the log10 CFU/ml) and the clearance rate (expressed as a percentage), which was defined as the number of cage fluid cultures without growth of E. faecalis divided by the total number of cages in the individual treatment group.

Antimicrobial activities on adherent E. faecalis in the animal model.

Five days after completion of treatment, animals were sacrificed and cages were removed under aseptic conditions. Each cage was then incubated in 5 ml TSB at 37°C for 48 h. Aliquots of 100 μl of these mixtures were spread on blood agar plates and incubated for an additional 48 h. The treatment efficacies against biofilm bacteria were assessed through the “cure” rate, defined as the number of cage cultures without E. faecalis growth divided by the total number of cages in the treatment group (expressed as a percentage).

Emergence of antimicrobial resistance in vivo.

Susceptibilities against fosfomycin, rifampin, and daptomycin were determined in E. faecalis cells growing in TSB from explanted cages (i.e., in treatment failures) to screen for emergence of antimicrobial resistance. A gradient strip diffusion test (Etest) was used, following the manufacturer's instructions (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden).

Statistical analyses.

Comparisons for continuous variables were performed by using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and by using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. For all tests, differences were considered significant when P values were <0.05. The graphs in the figures were plotted using Prism software (version 6.01; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

Table 1 summarizes the in vitro susceptibilities of planktonic and adherent E. faecalis cells. Fosfomycin, rifampin, and linezolid exhibited bacteriostatic activities in the logarithmic and stationary growth phases, even at the highest tested concentrations (64 to 512 μg/ml). The MIC, MBClog, and MBCstat for ampicillin were 1, 2, and 2 μg/ml, respectively; however, at ampicillin concentrations above 2 μg/ml, the number of bacteria recovered after 24 h of incubation increased with higher ampicillin concentrations (paradoxical effect).

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of planktonic and adherent E. faecalis (ATCC 19433) determined by conventional broth macrodilution and microcalorimetry

| Antimicrobial agent | Susceptibilitya (μg/ml) based on: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broth macrodilution |

Microcalorimetry |

|||||

| MIC | MBClog | MBCstat | MHIC | MBEC3 h | MBEC24 h | |

| Fosfomycin | 32 | >512 | >512 | 64 | >512 | >512 |

| Rifampin | 4 | >64 | >64 | 4 | >512 | >512 |

| Ampicillin | 1 | 2b | 2b | 2 | >512 | >512 |

| Linezolid | 2 | >256 | >256 | 4 | >512 | >512 |

| Gentamicinc | 16 | 32 | 4 | 16 | 128 | 512 |

| Vancomycinc | 1 | >64 | >64 | 1 | >512 | >512 |

| Daptomycinc | 1 | 5 | >20 | 1 | >512 | >512 |

MBClog, the MBC during the logarithmic growth phase; MBCstat, the MBC during the stationary growth phase; MHIC, minimal heat inhibition concentration; MBEC3 h, the minimal biofilm eradication concentration in a 3-h biofilm; MBEC24 h, the minimal biofilm eradication concentration in a 24-h biofilm. Values represent medians of triplicate measurements.

At ampicillin concentrations above 2 μg/ml, the number of E. faecalis organisms recovered after 24 h of incubation increased with higher ampicillin concentrations (a paradoxical effect).

Broth macrodilution data for this agent were extracted from reference 10.

Time-kill studies.

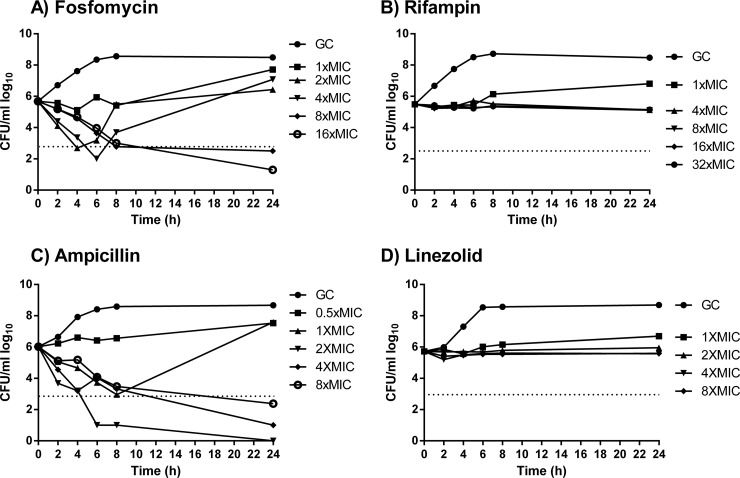

Fosfomycin inhibited bacterial growth at 1× MIC and was bactericidal at ≥2× MIC (Fig. 1). However, at 2× and 4× MIC, regrowth occurred after 24 h, and in these strains fosfomycin resistance emerged (MIC, >1,024 μg/ml). Rifampin and linezolid inhibited growth at any concentration above 1× MIC. Ampicillin was bactericidal at 2×, 4×, and 8× MIC but showed better killing activity at 2× MIC than at 4× and 8× MIC (paradoxical antimicrobial effect).

FIG 1.

Time-kill studies for fosfomycin (A), rifampin (B), ampicillin (C), and linezolid (D) during logarithmic growth. The horizontal dashed line represents the reduction of 3 log10 CFU/ml compared to the initial bacterial count. GC, growth control.

Antimicrobial activities on planktonic E. faecalis cells based on microcalorimetry.

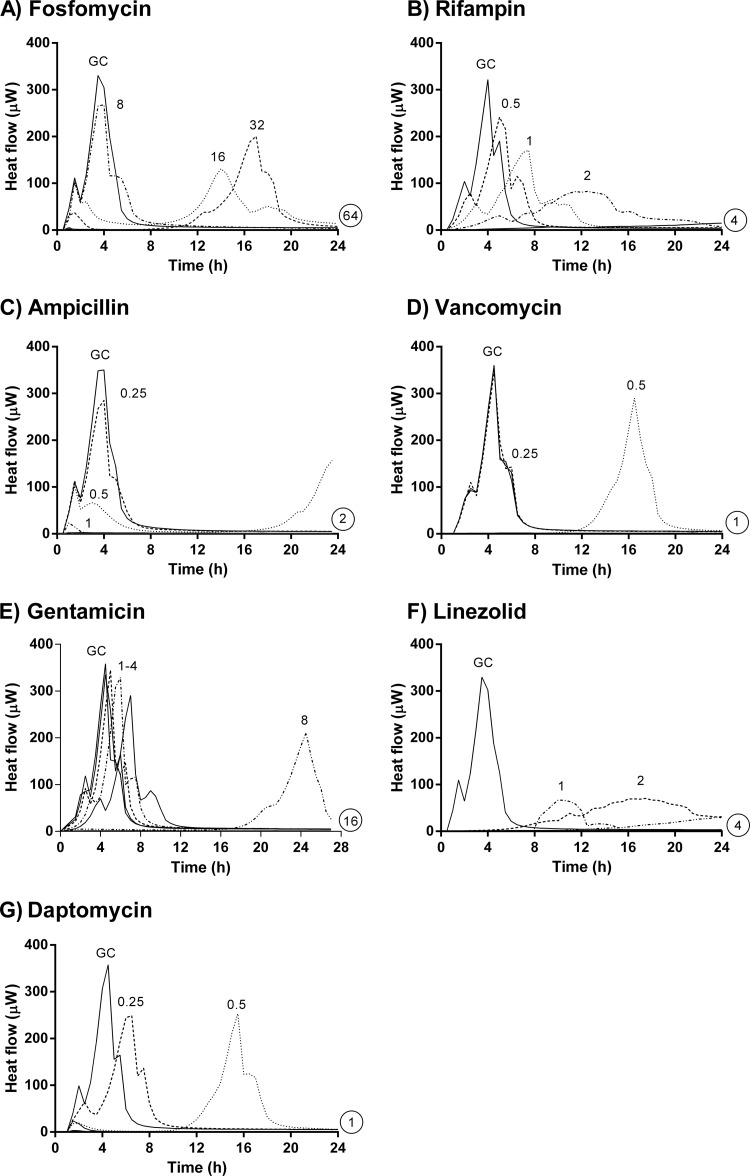

The MHICs correlated well with MICs obtained with the standard broth macrodilution method (Table 1). The antimicrobial activities were evaluated by the delay and reduction of the heat flow peak compared to the growth control in the absence of antibiotic (Fig. 2). Fosfomycin showed a reduction of the heat flow peak at 0.5× MIC. However, after 12 h, regrowth was observed at 0.5× and 1× MIC, corresponding to the findings in time-kill studies. Rifampin and linezolid caused delays in growth-related heat production and a reduction of the heat flow peak at 0.125×, 0.25×, and 0.5× MIC. Ampicillin showed activity at 0.125× MIC, mainly in the reduction of the heat flow peak.

FIG 2.

Microcalorimetry of planktonic E. faecalis. Numbers represent concentrations (in μg/ml) of fosfomycin (A), rifampin (B), ampicillin (C), vancomycin (D), gentamicin (E), linezolid (F), and daptomycin (G). Circled values represent the MHIC, defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration that inhibited heat production during 24 h. GC, growth control.

Antimicrobial activity on adherent E. faecalis based on microcalorimetry evaluation.

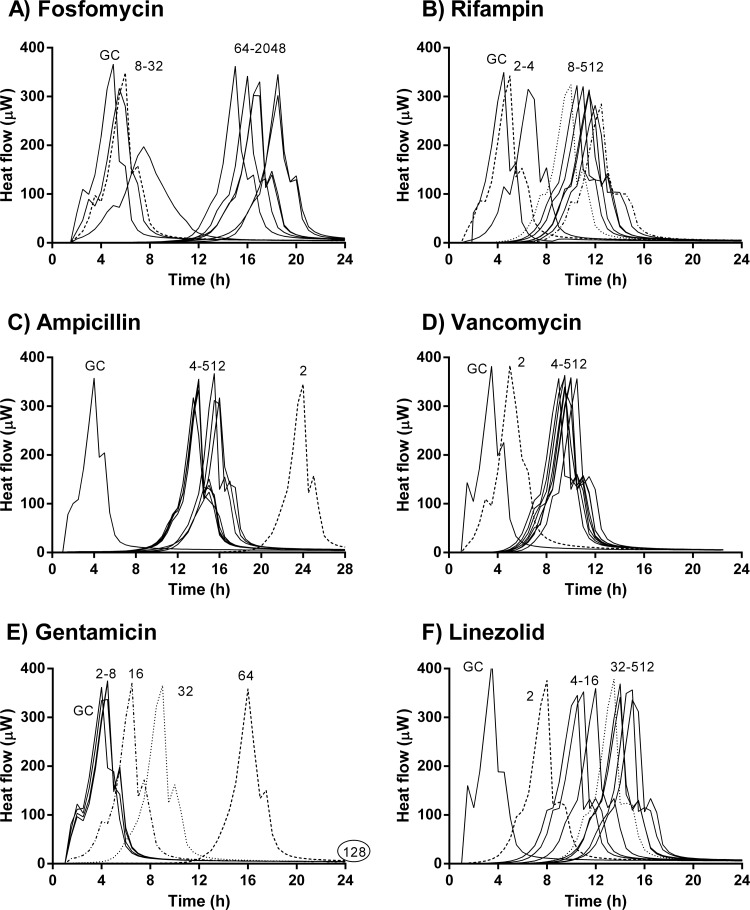

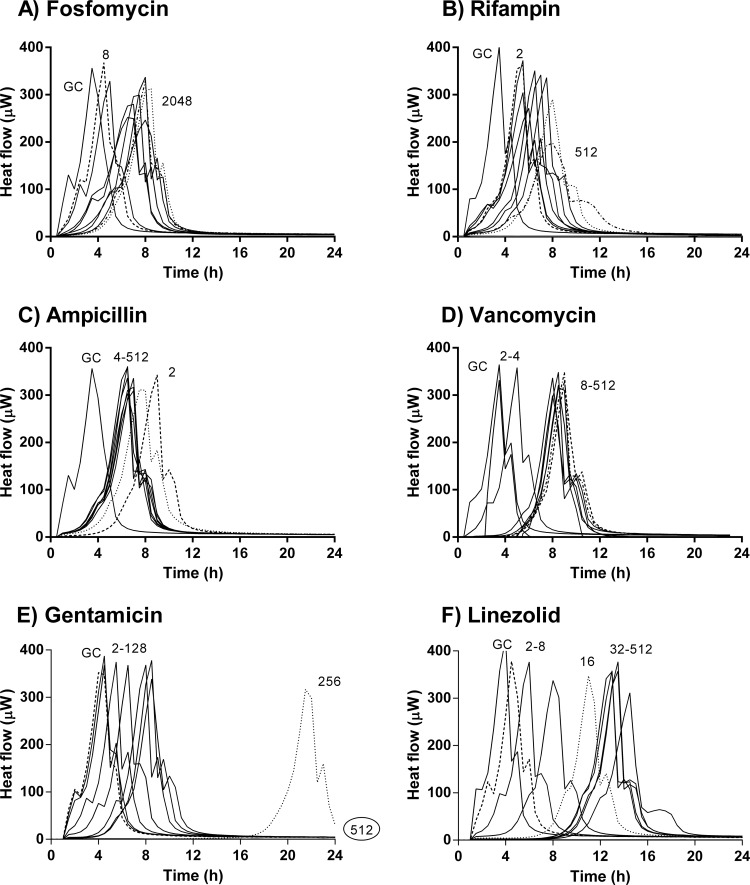

The antimicrobial activities on early (3 h) and mature (24 h) biofilms are shown in Fig. 3 and 4, respectively. With the exception of gentamicin, which suppressed heat production at 128 μg/ml at 3 h (Fig. 3E) and at 512 μg/ml at 24 h (Fig. 4E), no complete inhibition of heat production was observed with other antibiotics, even at concentrations up to 512 μg/ml. However, the activity of each antibiotic against early biofilm was stronger than against a mature biofilm. At concentrations below the MIC, fosfomycin had no effect on E. faecalis biofilm, whereas at higher concentrations (64 to 2,048 μg/ml), the heat production was delayed. This effect was more evident in early than in mature biofilm (Fig. 3A and 4A, respectively). With fosfomycin, no concentration-dependent activity was observed. In contrast, rifampin showed concentration-dependent activity (Fig. 3B and 4B). In the early biofilms, there was a difference in the drug activity between low (2 to 4 μg/ml) and high (8 to 512 μg/ml) concentrations. With ampicillin, the longest delay in heat production was found at 2 μg/ml, especially in early biofilms. No concentration-dependent differences in the antibiofilm activity were observed between 4 μg/ml and 512 μg/ml, in either early or mature biofilms (Fig. 3C and 4C). For vancomycin, no differences were found between early and mature biofilms, and its activity did not improve at higher concentrations (Fig. 3D and 4D). Linezolid showed a concentration-dependent activity from 2 μg/ml to 32 μg/ml on early biofilms (Fig. 3F) and from 2 μg/ml to 64 μg/ml on mature biofilms (Fig. 4F); at higher concentrations, no improved activity of linezolid was observed.

FIG 3.

Microcalorimetry results for adherent E. faecalis (3-h biofilm). Numbers represent concentrations (in μg/ml) of fosfomycin (A), rifampin (B), ampicillin (C), vancomycin (D), gentamicin (E), and linezolid (F). Circled values represent the MBEC. GC, growth control.

FIG 4.

Microcalorimetry results for adherent E. faecalis (24-h biofilm). Numbers represent concentrations (in μg/ml) of fosfomycin (A), rifampin (B), ampicillin (C), vancomycin (D), gentamicin (E), and linezolid (F). Circled values represent the MBEC. GC, growth control.

The combination of fosfomycin and gentamicin showed a complete inhibition of heat production, in both early and mature biofilms at concentrations of fosfomycin of 1,024 μg/ml plus gentamicin at 16 to 32 μg/ml and fosfomycin at 1,024 μg/ml plus gentamicin at 64 μg/ml, respectively.

Antimicrobial activities on planktonic E. faecalis in the animal model.

Before start of treatment (i.e., day 1), cage fluid contained 1.6 × 105 CFU/ml (i.e., 5.20 log10 CFU/ml). Figure 5A shows the counts of planktonic bacteria in cage fluid during treatment (i.e., day 4) and 5 days after the end of treatment (i.e., day 9). In the untreated (control) animals, the bacterial load was 4.08 and 4.16 log10 CFU/ml on day 4 and day 9, respectively. During treatment, the bacterial count decreased to 1.29 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin alone (P < 0.001), 0.75 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin plus gentamicin (P < 0.001), 1.32 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin plus rifampin (P < 0.001), 0.78 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin plus daptomycin (P < 0.001), 1.86 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin plus vancomycin, 2.01 log10 CFU/ml with rifampin plus daptomycin, and 2.4 log10 CFU/ml with rifampin plus vancomycin. With rifampin alone, the bacterial count was 4.65 log10 CFU/ml (during treatment) and 4.75 log10 CFU/ml (after treatment). Compared to the bacterial count during treatment, the count increased after treatment to 0.97 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin plus gentamicin, to 2.17 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin plus rifampin, to 2.91 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin plus vancomycin, and to 3.72 log10 CFU/ml with rifampin plus vancomycin, whereas the count remained stable and low at 0.73 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin plus daptomycin (P < 0.001) and decreased to 0.92 log10 CFU/ml with fosfomycin alone (P < 0.001) and to 1.12 log10 CFU/ml with rifampin plus daptomycin.

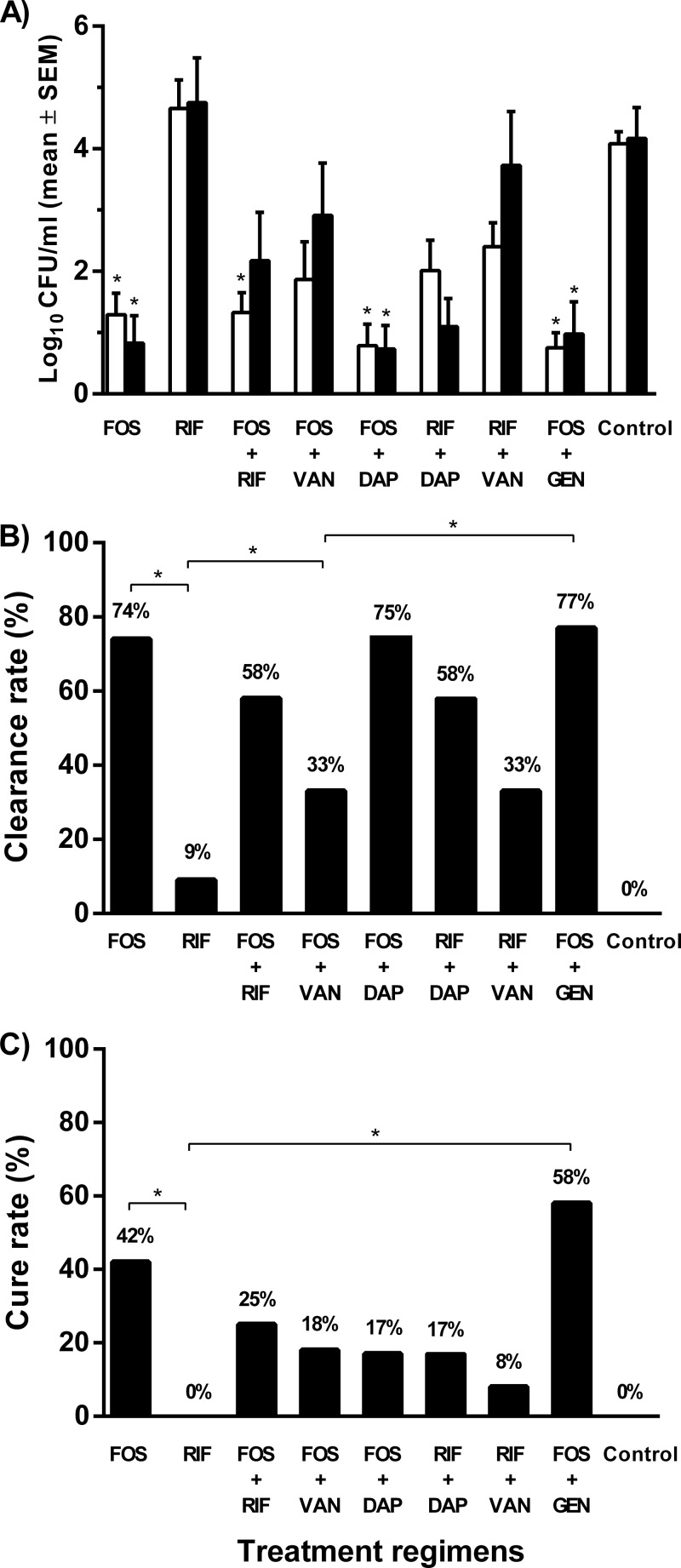

FIG 5.

Antimicrobial activity on planktonic and adherent E. faecalis cells in the animal model. (A) Planktonic bacterial counts in cage fluid during treatment (white bars) and 5 days after treatment (black bars). *, P < 0.001 (compared to control animals). SEM, standard error of the mean. (B) Clearance of planktonic bacteria in cage fluid. *, P < 0.05. (C) Cure rate of adherent E. faecalis from explanted cages. *, P < 0.05. FOS, fosfomycin; RIF, rifampin; DAP, daptomycin; VAN, vancomycin; GEN, gentamicin; control, untreated animals.

Figure 5B shows the clearance rate of planktonic bacteria from the cage fluid. No spontaneous clearance was observed in the untreated (control) animals. Fosfomycin alone showed a clearance rate of 74%, in combination with gentamicin the rate was 77%, with daptomycin it was 75%, with vancomycin it was 33%, and with rifampin the rate was 58%. Rifampin alone showed a clearance rate of 9%, which increased to 33% in combination with vancomycin and to 58% with daptomycin.

Antimicrobial activity on adherent E. faecalis in the animal model.

In the control (untreated) animals, no spontaneous cure occurred. Fosfomycin alone eradicated adherent E. faecalis in 43% of cages. Fosfomycin in combination with gentamicin increased the cure rate to 58%. Despite the high activities of fosfomycin and daptomycin against planktonic bacteria, this combination eradicated adherent bacteria in only 17% of cages. Rifampin alone had no effect on adherent E. faecalis, whereas the addition of fosfomycin and daptomycin enhanced the cure rate to 25% and 17%, respectively.

Emergence of antimicrobial resistance in vivo.

Among the explanted cages that showed bacterial growth (treatment failures), no resistant strains to fosfomycin, rifampin, or daptomycin were detected.

DISCUSSION

Spread of resistance to penicillin derivatives, glycopeptides, and aminoglycosides has reduced the available treatment options for enterococcal infections (31, 32). In the presence of a foreign body, enterococcal infections present an additional challenge, since most antibiotics lack antibiofilm activity against enterococci (3, 8). In this study, the activities of fosfomycin and rifampin, alone and in combination with antibiotics active against enterococci, such as vancomycin, daptomycin, ampicillin, and linezolid, were tested against E. faecalis biofilms in vitro and in an established animal model.

In vitro, the macrodilution method and a microcalorimetry assay showed comparable results, with the advantage of microcalorimetry providing real-time data on bacterial growth (or inhibition thereof in the presence of antibiotic combinations) by continuous recording of bacterial heat production. Importantly, microcalorimetry showed that regrowth of E. faecalis occurred in the presence of fosfomycin at 16 and 32 μg/ml already after 12 h of antimicrobial exposure, which was also observed in the time-kill studies. The rapid emergence of fosfomycin resistance during treatment is the main limiting factor for the use of fosfomycin in clinical practice (33). The development of chromosomal resistance to fosfomycin implies a biological cost in virulence and fitness of Gram-negative pathogens (12, 34–36). Whether this applies also to enterococci is possible, but has not yet been demonstrated.

Both microcalorimetry and time-kill studies showed the presence of a paradoxical effect for E. faecalis and ampicillin. The paradoxical effect (Eagle phenomenon), which was first described by Eagle in 1948, is defined as a bactericidal activity that decreases when the concentration of the antibiotic increases. The mechanism of this phenomenon has not been clearly established; defective autolytic activity when exposed to high concentrations of antibiotics has been implicated for E. faecalis (37). However, the clinical relevance of this phenomenon is still unclear and needs further investigation.

The activity against E. faecalis in biofilms was evaluated in vitro by microcalorimetry using glass beads, which simulated the Calgary biofilm device method (38) and determined the biofilm recovery after 24 h of antibiotic challenge. With the exception of gentamicin, no other antibiotic inhibited bacterial heat production in early or mature E. faecalis biofilms, even at concentrations exceeding the achievable values in clinical practice. Antibiotics were more active against the early (3 h) rather than mature (24 h) biofilm, highlighting the importance of a rapid start of treatment for implant-associated infections caused by enterococci.

In the present study, the experimental conditions were modified from those used previously in the animal model (16–19). First, the infection inoculum was reduced from 105 to 104 CFU/cage, and second, the duration of infection was shortened to 3 h, based on a previous study involving E. faecalis (10). If treatment was started after an infection duration of 24 h, no cure of cage infections was achieved with any antibiotic or combination regimen (data not shown). However, even with the short, 3-h duration of infection, the highest cure rate did not exceed 42%, highlighting that E. faecalis is a difficult-to-treat microorganism that tends to adhere and persist on foreign bodies, explaining the high rate of treatment failure.

Fosfomycin showed activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative biofilms, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing E. coli, and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (13, 39–42; R. Mihailescu, U. Furustrand Tafin, S. Corvec, A. Oliva, B. Betrisey, O. Borens, A. Trampuz, submitted for publication). However, the role of fosfomycin in enterococcal biofilm infections has not been widely investigated. In the present study, fosfomycin alone eradicated adherent E. faecalis from 42% of infected cages, which could be explained by the immunomodulatory effect of fosfomycin (34, 43). However, due to the risk of emergence of fosfomycin resistance, fosfomycin is not recommended for monotherapy in clinical practice (13).

In contrast to staphylococci, for which the combination of an antistaphylococcal agent with rifampin has been shown to improve the cure rate in implant-associated infections (9, 16, 17, 44, 45), the role of rifampin in enterococcal infection remains controversial. Rifampin was investigated against enterococcal biofilms in combination with ciprofloxacin and linezolid in vitro (46) and in combination with tigecycline in vivo (47). In our study, rifampin showed no activity against enterococcal biofilms, either in vitro or in vivo. While alone a cure rate of 0% was observed, rifampin activity against biofilms was improved to 8% in combination with vancomycin, to 17% with daptomycin, and to 25% with fosfomycin.

Despite the combination of fosfomycin and daptomycin showing the highest clearance rate of planktonic bacteria (75%), the cure rate (eradication of adherent bacteria from cages) was only 17%. Similar results were found in a recent study using the same guinea pig model (Trampuz et al., submitted), where the combination fosfomycin plus daptomycin was active only on planktonic and not biofilm MRSA, despite use of a higher daptomycin dose (50 mg/kg), which was equivalent to ≈10 mg/kg in humans. The daptomycin dose used in our animal experiments (40 mg/kg) corresponds to ≈8 mg/kg in humans (17, 48–50). This dose is higher than the currently recommended dose for staphylococcal infections (4 to 6 mg/kg) (51). However, daptomycin MICs for enterococci are in general 1- to 2-fold higher than those for S. aureus, and higher daptomycin doses are probably needed for treatment of enterococcal infections, especially in immunocompromised patients, device-related infections, and infective endocarditis (52–56). Thus, higher daptomycin doses (equivalent to 10 to 12 mg/kg in humans) may be needed in order to penetrate into biofilms and kill adherent enterococci.

In the present study, the most efficient regimen for killing planktonic and adherent E. faecalis was the combination of fosfomycin and gentamicin. Previous studies had demonstrated that gentamicin improves the activities of daptomycin and vancomycin against E. faecalis (10), and the combination of fosfomycin and gentamicin has been studied for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (57). However, with regard to enterococcal infections, clinical data are lacking.

In conclusion, fosfomycin showed activity against planktonic and adherent E. faecalis. Its role in the treatment of enterococcal biofilms should be further investigated, especially in combination with gentamicin, rifampin, and/or daptomycin.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 October 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart PS, Costerton JW. 2001. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Lancet 358:135–138. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05321-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trampuz A, Widmer AF. 2006. Infections associated with orthopedic implants. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 19:349–356. 10.1097/01.qco.0000235161.85925.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calfee DP. 2012. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and other Gram-positives in healthcare. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 25:385–394. 10.1097/QCO.0b0133283553441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias CA, Murray BE. 2012. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:266–278. 10.1038/nrmicro2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohamed JA, Huang DB. 2007. Biofilm formation by enterococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:1581–1588. 10.1099/jmm.0.47331-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sava IG, Heikens E, Huebner J. 2010. Pathogenesis and immunity in enterococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:533–540. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. 2004. Prosthetic-joint infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:1645–1654. 10.1056/NEJMra040181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerli W, Widmer AF, Blatter M, Frei R, Ochsner PE. 1998. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. JAMA 279:1537–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furustrand Tafin U, Majic I, Zalila Belkhodja C, Betrisey B, Corvec S, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A. 2011. Gentamicin improves the activities of daptomycin and vancomycin against Enterococcus faecalis in vitro and in an experimental foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4821–4827. 10.1128/AAC.00141-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falagas ME, Roussos N, Gkegkes ID, Rafailidis PI, Karageorgopoulos DE. 2009. Fosfomycin for the treatment of infections caused by Gram-positive cocci with advanced antimicrobial drug resistance: a review of microbiological, animal and clinical studies. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 18:921–944. 10.1571/13543780902967624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michalopoulos AS, Livaditis IG, Gougoutas V. 2011. The revival of fosfomycin. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 15:e732–e739. 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raz R. 2012. Fosfomycin: an old-new antibiotic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:4–7. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poeppl W, Tobudic S, Lingscheid T, Plasenzotti R, Kozakowski N, Lagler H, Georgopoulos A, Burgmann H. 2011. Daptomycin, fosfomycin, or both for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis in an experimental rat model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4999–5003. 10.1128/AAC.00584-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchese A, Bozzolasco M, Gualco L, Debbia EA, Schito GC, Schito AM. 2003. Effect of fosfomycin alone and in combination with N-acetylcysteine on E. coli biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 22(Suppl 2):95–100. 10.1016/S0924-8579(03)00232-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldoni D, Haschke M, Rajacic Z, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A. 2009. Linezolid alone or combined with rifampin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in experimental foreign-body infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1142–1148. 10.1128/AAC.00775-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.John AK, Baldoni D, Haschke M, Rentsch K, Schaerli P, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A. 2009. Efficacy of daptomycin in implant-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: importance of combination with rifampin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2719–2724. 10.1128/AAC.00047-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trampuz A, Murphy CK, Rothstein DM, Widmer AF, Landmann R, Zimmerli W. 2007. Efficacy of a novel rifamycin derivative, ABI-0043, against Staphylococcus aureus in an experimental model of foreign-body infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2540–2545. 10.1128/AAC.00120-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerli W, Frei R, Widmer AF, Rajacic Z. 1994. Microbiological tests to predict treatment outcome in experimental device-related infections due to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33:959–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blaser J, Vergeres P, Widmer AF, Zimmerli W. 1995. In vivo verification of in vitro model of antibiotic treatment of device-related infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1134–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bridier A, Dubois-Brissonnet F, Boubetra A, Thomas V, Briandet R. 2010. The biofilm architecture of sixty opportunistic pathogens deciphered using a high throughput CLSM method. J. Microbiol. Methods 82:64–70. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CLSI 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, seventh ed. Document M7-A7 CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braissant O, Wirz D, Gopfert B, Daniels AU. 2010. Use of isothermal microcalorimetry to monitor microbial activities. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 303:1–8. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.01819.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trampuz A, Salzmann S, Antheaume J, Daniels AU. 2007. Microcalorimetry: a novel method for detection of microbial contamination in platelet products. Transfusion 47:1643–1650. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trampuz A, Steinhuber A, Wittwer M, Leib SL. 2007. Rapid diagnosis of experimental meningitis by bacterial heat production in cerebrospinal fluid. BMC Infect. Dis. 7:116. 10.1186/1471-2334-7-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Ah U, Wirz D, Daniels AU. 2009. Isothermal micro calorimetry. A new method for MIC determinations: results for 12 antibiotics and reference strains of E. coli and S. aureus. BMC Microbiol. 9:106. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmerli W, Waldvogel FA, Vaudaux P, Nydegger UE. 1982. Pathogenesis of foreign body infection: description and characteristics of an animal model. J. Infect. Dis. 146:487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poeppl W, Tobudic S, Lingscheid T, Plasenzotti R, Kozakowski N, Georgopoulos A, Burgmann H. 2011. Efficacy of fosfomycin in experimental osteomyelitis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:931–933. 10.1128/AAC.00881-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pachon-Ibanez ME, Ribes S, Dominguez MA, Fernandez R, Tubau F, Ariza J, Gudiol F, Cabellos C. 2011. Efficacy of fosfomycin and its combination with linezolid, vancomycin and imipenem in an experimental peritonitis model caused by a Staphylococcus aureus strain with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30:89–95. 10.1007/s10096-010-1058-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribes S, Taberner F, Domenech A, Cabellos C, Tubau F, Linares J, Viladrich PF, Gudiol F. 2006. Evaluation of fosfomycin alone and in combination with ceftriaxone or vancomycin in an experimental model of meningitis caused by two strains of cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:931–936. 10.1093/jac/dkl047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amyes SG. 2007. Enterococci and streptococci. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29(Suppl 3):S43–S52. 10.1016/S0924-8579(07)72177-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Courvalin P. 2006. Vancomycin resistance in gram-positive cocci. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42(Suppl 1):S25–S34. 10.1086/491711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popovic M, Steinort D, Pillai S, Joukhadar C. 2010. Fosfomycin: an old, new friend? Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:127–142. 10.1007/s10096-009-0833-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alos JI, Garcia-Pena P, Tamayo J. 2007. Biological cost associated with fosfomycin resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from urinary tract infections. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 20:211–215 (In Spanish) http://www.seq.es/seq/0214-3429/20/2/211/pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchese A, Gualco L, Debbia EA, Schito GC, Schito AM. 2003. In vitro activity of fosfomycin against gram-negative urinary pathogens and the biological cost of fosfomycin resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 22(Suppl 2):53–59. 10.1016/S0924-8579(03)00230-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsson AI, Berg OG, Aspevall O, Kahlmeter G, Andersson DI. 2003. Biological costs and mechanisms of fosfomycin resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2850–2858. 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2850-2858.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fontana R, Boaretti M, Grossato A, Tonin EA, Lleò MM, Satta G. 1990. Paradoxical response of Enterococcus faecalis to the bactericidal activity of penicillin is associated with reduced activity of one autolysin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:314–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ceri H, Olson ME, Stremick C, Read RR, Morck D, Buret A. 1999. The Calgary biofilm device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1771–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikuniya T, Kato Y, Ida T, Maebashi K, Monden K, Kariyama R, Kumon H. 2007. Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms with a combination of fluoroquinolones and fosfomycin in a rat urinary tract infection model. J. Infect. Chemother. 13:285–290. 10.1007/s10156-007-0534-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grif K, Dierich MP, Pfaller K, Miglioli PA, Allerberger F. 2001. In vitro activity of fosfomycin in combination with various antistaphylococcal substances. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:209–217. 10.1093/jac.48.2.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corvec S, Furustrand Tafin U, Betrisey B, Borens O, Trampuz A. 2013. Activities of fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin against extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in a foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:1421–1427. 10.1128/AAC.01718-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrigos C, Murillo O, Lora-Tamayo J, Verdaguer R, Tubau F, Cabellos C, Cabo J, Ariza J. 2013. Fosfomycin-daptomycin and other fosfomycin combinations as alternative therapies in experimental foreign-body infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:606–610. 10.1128/AAC.01570-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morikawa K, Nonaka M, Torii I, Morikawa S. 2003. Modulatory effect of fosfomycin on acute inflammation in the rat air pouch model. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 21:334–339. 10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00358-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vergidis P, Rouse MS, Euba G, Karau MJ, Schmidt SM, Mandrekar JN, Steckelberg JM, Patel R. 2011. Treatment with linezolid or vancomycin in combination with rifampin is effective in an animal model of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus foreign body osteomyelitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1182–1186. 10.1128/AAC.00740-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Widmer AF, Gaechter A, Ochsner PE, Zimmerli W. 1992. Antimicrobial treatment of orthopedic implant-related infections with rifampin combinations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:1251–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holmberg A, Morgelin M, Rasmussen M. 2012. Effectiveness of ciprofloxacin or linezolid in combination with rifampicin against Enterococcus faecalis in biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:433–439. 10.1093/jac/dkr477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minardi D, Cirioni O, Ghiselli R, Silvestri C, Mocchegiani F, Gabrielli E, d'Anzeo G, Conti A, Orlando F, Rimini M, Brescini L, Guerrieri M, Giacometti A, Muzzonigro G. 2012. Efficacy of tigecycline and rifampin alone and in combination against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm infection in a rat model of ureteral stent. J. Surg. Res. 176:1–6. 10.1016/j.jss.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benvenuto M, Benziger DP, Yankelev S, Vigliani G. 2006. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of daptomycin at doses up to 12 milligrams per kilogram of body weight once daily in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3245–3249. 10.1128/AAC.00247-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dvorchik BH, Brazier D, DeBruin MF, Arbeit RD. 2003. Daptomycin pharmacokinetics and safety following administration of escalating doses once daily to healthy subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1318–1323. 10.1128/AAC.47.4.1318-1323.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wise R, Gee T, Andrews JM, Dvorchik B, Marshall G. 2002. Pharmacokinetics and inflammatory fluid penetration of intravenous daptomycin in volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:31–33. 10.1128/AAC.46.1.31-33.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, Rybak M, Jr, Talan DA, Chambers HF. 2011. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:285–292. 10.1093/cid/cir034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall AD, Steed ME, Arias CA, Murray BE, Rybak MJ. 2012. Evaluation of standard- and high-dose daptomycin versus linezolid against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus isolates in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model with simulated endocardial vegetations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3174–3180. 10.1128/AAC.06439-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arias CA, Torres HA, Singh KV, Panesso D, Moore J, Wanger A, Murray BE. 2007. Failure of daptomycin monotherapy for endocarditis caused by an Enterococcus faecium strain with vancomycin-resistant and vancomycin-susceptible subpopulations and evidence of in vivo loss of the vanA gene cluster. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:1343–1346. 10.1086/522656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Long JK, Choueiri TK, Hall GS, Avery RK, Sekeres MA. 2005. Daptomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 80:1215–1216. 10.4065/80.9.1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Munoz-Price LS, Lolans K, Quinn JP. 2005. Emergence of resistance to daptomycin during treatment of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:565–566. 10.1086/432121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poutsiaka DD, Skiffington S, Miller KB, Hadley S, Snydman DR. 2007. Daptomycin in the treatment of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia in neutropenic patients. J. Infect. 54:567–571. 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Souli M, Galani I, Boukovalas S, Gourgoulis MG, Chryssouli Z, Kanellakopoulou K, Panagea T, Giamarellou H. 2011. In vitro interactions of antimicrobial combinations with fosfomycin against KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and protection of resistance development. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2395–2397. 10.1128/AAC.01086-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]