Abstract

The bicomponent leukotoxins produced by Staphylococcus aureus kill host immune cells through osmotic lysis by forming β-barrel pores in the host plasma membrane. The current model for bicomponent pore formation proposes that octameric pores, comprised of two separate secreted polypeptides (S and F subunits), are assembled from water-soluble monomers in the extracellular milieu and multimerize on target cell membranes. However, it has yet to be determined if all staphylococcal bicomponent leukotoxin family members exhibit these properties. In this study, we report that leukocidin A/B (LukAB), the most divergent member of the leukotoxin family, exists as a heterodimer in solution rather than two separate monomeric subunits. Notably, this property was found to be associated with enhanced toxin activity. LukAB also differs from the other bicomponent leukotoxins in that the S subunit (LukA) contains 33- and 10-amino-acid extensions at the N and C termini, respectively. Truncation mutagenesis revealed that deletion of the N terminus resulted in a modest increase in LukAB cytotoxicity, whereas the deletion of the C terminus rendered the toxin inactive. Within the C terminus of LukA, we identified a glutamic acid at position 323 that is critical for LukAB cytotoxicity. Furthermore, we discovered that this residue is conserved and required for the interaction between LukAB and its cellular target CD11b. Altogether, these findings provide an in-depth analysis of how LukAB targets neutrophils and identify novel targets suitable for the rational design of anti-LukAB inhibitors.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus evades host immune defenses in part by targeting and killing leukocytes, such as polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs or neutrophils), that are recruited to the site of infection (1). The pathogen employs an extensive repertoire of membrane-damaging cytotoxins and cytolytic peptides in order to combat these cells (2). Among the cytotoxins, the bicomponent leukotoxins are the most complex, forming oligomeric pores from two separate polypeptides known as S and F subunits (3, 4). A single disease-causing S. aureus strain can produce up to five S subunits (LukS-PV, LukE, HlgA, HlgC, and LukA) and four respective F subunits (LukF-PV, LukD, HlgB, and LukB), resulting in five different bicomponent leukotoxins (LukSF-PV or Panton-Valentine leukocidin [PVL], LukED, HlgAB, HlgCB, and LukAB) (4).

PVL and γ-hemolysin (HlgAB and HlgCB) were the first identified staphylococcal bicomponent leukotoxins and thus have been the most extensively studied (5, 6). In addition to a number of structure-function analyses involving PVL and γ-hemolysin, the solved crystal structures of PVL (7, 8) and γ-hemolysin (9) subunit monomers as well as the solved structure of the HlgAB pore (10) have led to our current understanding of bicomponent leukotoxin pore formation. According to this model, the S and F subunits are secreted as water-soluble monomers (11) that initiate the first step in pore formation by binding to target cell membranes. The S subunit is typically the binding subunit (12–14); however, HlgAB binding to erythrocytes is mediated by the F subunit HlgB (15). It is becoming clear that toxin binding to host cells is mediated by nonredundant proteinaceous surface receptors (16). CCR5 (13) and CXCR1 and CXCR2 (14) were recently described as specific cellular receptors for LukED, while the C5a receptors (17) and CD11b (18) were identified as receptors for PVL and LukAB, respectively. In order for pore formation to progress, the binding subunit must recruit the other toxin subunit to target the plasma membrane of cells, which leads to oligomerization and formation of an octameric prepore composed of alternating S and F subunits (10, 19). The final stage in pore formation involves the insertion of the β-barrel pore into the target cell plasma membrane, ultimately resulting in cell death by osmotic lysis (10). Whether or not this model of pore formation applies to all the members of the bicomponent leukotoxin family remains to be determined, as extensive structure-function analyses have yet to be performed on other family members.

LukAB (20), also known as LukGH (21), is the most recently identified member of the bicomponent leukotoxin family and has been shown to selectively target innate leukocytes such as monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and PMNs (20). LukAB contributes to S. aureus pathogenesis in a murine renal abscess model (20), causes inflammation in a rabbit skin model (22), and promotes the escape of S. aureus from within PMNs (18, 20, 23). Recently, CD11b, the αM component of the αMβ2 integrin, also known as macrophage-1 antigen (Mac-1), was identified as a cellular receptor required for LukAB-mediated killing of human PMNs (18).

While the role of LukAB in S. aureus-PMN interactions has been well characterized, little is known about the functional domains required for LukAB activity. LukAB is the most divergent member of the bicomponent leukotoxin family (4). The amino acid sequence identity among bicomponent S or F subunits ranges from 60 to 80%, with the exception of LukA and LukB. Based on amino acid sequence alignment, LukA exhibits approximately 30% identity and LukB exhibits approximately 40% identity with the respective S and F subunits of the other S. aureus leukotoxins (4).

In light of the low sequence identity between LukAB and the other bicomponent leukotoxins and the absence of a solved crystal structure for LukA or LukB, it is difficult to design structure-function analyses of this toxin based on previous studies performed with PVL and γ-hemolysin. However, the mature form of LukA, the S subunit of LukAB, has notable extensions at both the N and C termini not found in any of the other S subunits (4), providing target regions for mutagenesis studies. Here, we set out to identify regions of LukAB required for toxin activity, specifically focusing on the unique N- and C-terminal extensions within the LukA subunit. By analyzing LukAB produced by S. aureus, we discovered that in contrast to the other staphylococcal bicomponent toxins, LukAB exists as a heterodimer in solution. This unexpected finding supports a model whereby LukAB interacts with target cells as an already partially assembled complex, which is likely to expedite multimerization and subsequent pore formation. We also identified a single amino acid, a glutamic acid at position 323 of the LukA C terminus, as a critical residue for toxin activity due to its requirement for the interaction between LukAB and its cellular target CD11b. Altogether, this study highlights unique functional attributes of LukAB and provides the first in-depth analysis of the interaction of this toxin with its proteinaceous receptor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

Blood samples were obtained from anonymous, consenting, healthy adult donors as buffy coats from the New York Blood Center. This study was reviewed and approved by the New York University Langone Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Bacterial strains and culture.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Staphylococcus aureus strains

| Strain | Background | Description | Designation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31.57 | Newman | ΔlukED::hlgACB::tet::lukAB::spec::hla::ermC | ΔΔΔΔ | 14 |

| 32.58 | USA300 LAC | (ErmS) pJC111 | WT | 23 |

| 32.59 | USA300 LAC | (ErmS) ΔlukAB pJC111 | ΔlukAB | 23 |

| 28.28 | USA300 LAC | (ErmS) ΔlukAB pJC111-PlukAB-lukAB | ΔlukAB::lukAB | This study |

| 28.29 | USA300 LAC | (ErmS) ΔlukAB pJC111-PlukAB-Δ10ClukAB | ΔlukAB::Δ10C | This study |

| 28.31 | USA300 LAC | (ErmS) ΔlukAB pJC111-PlukAB-E323AlukAB | ΔlukAB::E323A | This study |

TABLE 2.

Primers

| No. | Name | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 629 | NW.lukED.BamHI.F | 5′-CCCGGATCCAATACTAATATTGAAAATATTGGTGATG |

| 630 | NW.lukED.PstI.R | 5′-CCCCTGCAGTTATACTCCAGGATTAGTTTCTTTAG |

| 631 | NW.hlgCB.BamHI.F | 5′-CCCGGATCCGCTAACGATACTGAAGACATCG |

| 632 | NW.hlgCB.PstI.R | 5′-CCCCTGCAGCTATTTATTGTTTTCAGTTTCTTTTG |

| 633 | MW2.lukSF.BamHI.F | 5′-CCCGGATCCGAATCTAAAGCTGATAACAATATTG |

| 634 | MW2.lukSF.PstI.R | 5′-CCCCTGCAGTTAGCTCATAGGATTTTTTTCCTTAG |

| 544 | BamHI.lukA.F | 5′-CCCGGATCCCATAAAGACTCTCAAGACCAAAAT |

| 588 | Δ10ClukA.R.Xba | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTAATATTTATCAACGACTTTAACTG |

| 587 | Δ33NlukA.F.BamHI | 5′-CCCGGATCCTCAACAGCACCGGATGATATTG |

| 545 | Xba.lukA.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTTCTTTATAAGGTTTATTG |

| 638 | Xba.LukAS315A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTTCTTTATAAGGTTTATTGTCATCTGCATATTTATCAACGAC |

| 639 | Xba.LukA.D316A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTTCTTTATAAGGTTTATTGTCTGCAGAATATTTATCAAC |

| 640 | Xba.LukA.D317A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTTCTTTATAAGGTTTATTTGCATCAGAATATTTATC |

| 641 | Xba.LukA.N318A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTTCTTTATAAGGTTTTGCGTCATCAGAATATTTATC |

| 642 | Xba.LukA.K319A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTTCTTTATAAGGTGCATTGTCATCAG |

| 643 | Xba.LukA.P320A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTTCTTTATATGCTTTATTGTCATCAG |

| 644 | Xba.LukA.Y321A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTTCTTTTGCAGGTTTATTGTCATC |

| 645 | Xba.LukA.K322A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTTCTGCATAAGGTTTATTGTC |

| 646 | Xba.LukA.E323A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATCCTGCTTTATAAGGTTTATTG |

| 647 | Xba.LukA.G324A.R | 5′-CCCTCTAGATTATGCTTCTTTATAAGGTTTATTG |

TABLE 3.

Plasmids

| Name | Description | Resistance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-lukA-lukB | Expression vector with the lukAB operon, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | 18 |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-lukE-lukD | Expression vector with the lukED operon, N-terminal 6His tag on LukE | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-lukS-PV-lukF-PV | Expression vector with the lukSF-PV operon, N-terminal 6His tag on LukS-PV | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-hlgC-hlgB | Expression vector with the hlgCB operon, N-terminal 6His tag on HlgC | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-Δ10ClukA-lukB | Expression vector with the Δ10C lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-Δ33NlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the Δ33N lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-S315AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the S315A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-D316AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the D316A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-D317AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the D317A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-N318AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the N318A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-K319AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the K319A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-P320AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the P320A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-Y321AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the Y321A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-K322AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the K322A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-E323AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the E323A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pOS-1-PlukAB-sslukA-6His-G324AlukA-lukB | Expression vector with the G324A lukA and lukB loci, N-terminal 6His tag on LukA | Cm | This study |

| pJC111 | Empty vector used for integration unto the SaPI-1 site | Cad | 28 |

| pJC111-PlukAB-6His-lukAB | Integration vector with the wild-type (WT) lukA and lukB loci | Cad | This study |

| pJC111-PlukAB-6His-Δ10ClukAB | Integration vector with Δ10C lukA and lukB loci | Cad | This study |

| pJC111-PlukAB-6His-E323AlukAB | Integration vector with E323A lukA and lukB loci | Cad | This study |

S. aureus isolate Newman (24, 25) or USA300 strain LAC (26) was used in all experiments as the “wild-type” (WT) strain (unless explicitly stated). S. aureus was grown on tryptic soy broth (TSB) solidified with 1.5% agar at 37°C or in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI 1640; Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% Casamino Acids (RPMI+CAS) (20, 27), with shaking at 180 rpm, unless otherwise indicated. When appropriate, RPMI+CAS was supplemented with chloramphenicol (Cm) at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml.

Escherichia coli DH5α was used to propagate plasmids. DH5α strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or in LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin.

Mammalian cell lines.

HL60 cells (ATCC CCL-240) were maintained in RPMI medium (Cellgro) at 37°C with 5% CO2, where culture medium was supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). HL60 cells were differentiated into PMN-HL60 cells with 1.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) for 72 h at ∼2.5 × 105 cells/ml (20, 23).

Isolation of primary human PMNs.

PMNs were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by a Ficoll-Paque Plus gradient. The pellets were subsequently washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and PMNs were separated from erythrocytes with 3% dextran (Dextran 500; Pharmacosmos) in 0.9% sodium chloride (Hospira). Remaining erythrocytes were lysed with ACK lysing buffer (Gibco). PMN purity was at 90 to 95% as determined by flow cytometry.

(i) Mutant strains.

To generate an S. aureus Newman toxinless strain (Newman ΔΔΔΔ), a Newman ΔlukED parental strain previously described (28) was transduced with phage carrying hlgACB::Tet, followed by lukAB::Spec and then hla::Erm (14).

(ii) Complementation strains.

Integrated complementation strains were generated by cloning into plasmid pJC1111, which contains a cadmium (Cad) resistance cassette and the SaPI1 integration cassette and stably integrates into the SaPI-1 site of S. aureus, resulting in single-copy chromosomal complementation (28). To generate the pJC1111-PlukAB-lukAB, pJC1111-PlukAB-Δ10ClukAB, and pJC1111-PlukAB-E323AlukAB complementation vectors, a PCR amplicon containing the WT or mutated lukAB operon with the endogenous promoter was generated using primer pairs 681 and 695 as previously described (23) and the PlukAB-sslukA-6His-lukA-lukB, PlukAB-sslukA-6His-Δ10ClukA-lukB, PlukAB-sslukA-6His-Δ33NlukA-lukB, and PlukAB-sslukA-6His-E323AlukA-lukB plasmids (described below), respectively, as the templates. All amplicons were subsequently digested with PstI and KpnI and subcloned into pJC1111. The resulting plasmids were then integrated into the S. aureus SaPI-1 site (28).

His-LukAB copurification from S. aureus.

A construct to copurify recombinant LukAB from S. aureus was generated as previously described (18). This construct was also used to express and purify LukED, HlgCB, and PVL, as well as mutated versions of LukA with WT LukB. The lukED and hlgCB loci were amplified from Newman genomic DNA with primers 629 and 630, or primers 631 and 632, respectively. The lukSF-PV locus was amplified from MW2 genomic DNA with primers 633 and 634. Mature lukA with the C-terminal 10-amino-acid deletion or the N-terminal 33-amino-acid deletion was amplified from S. aureus Newman genomic DNA using primers 544 and 588, or 587 and 545, respectively. The 10 C-terminal amino acids of LukA were also mutated by alanine-scanning mutagenesis, where mature lukA was amplified from S. aureus Newman genomic DNA using primer 544 paired with primers 638 to 647. The PCR amplicons were digested with BamHI and XbaI and ligated into the pOS1 PlukAB-sslukA-6His-lukB plasmid previously digested with BamHI and XbaI. Plasmids were transformed into E. coli, propagated, and purified and then transformed into S. aureus RN4220 and subsequently into S. aureus Newman ΔlukAB (20) or Newman ΔΔΔΔ (14).

All proteins were purified from S. aureus as previously described (18). Briefly, the strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) with 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol for 5 h at 37°C, 180 rpm, to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼1.5. The bacteria were then pelleted, and the supernatant was collected and filtered. The culture supernatant was incubated with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin (Qiagen), washed, and eluted with 500 mM imidazole. The protein was dialyzed in 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS) plus 10% glycerol at 4°C overnight and then stored at −80°C.

Exoprotein production.

S. aureus strains were grown in RPMI+CAS unless otherwise indicated. Five-milliliter overnight cultures were grown in 15-ml conical tubes held at a 45° angle and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 180 rpm (20). Following overnight culture, bacteria were subcultured at a 1:100 dilution and grown as described above for 5 h. Bacteria were then pelleted by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm and 4°C for 15 min. Supernatants containing exoproteins were collected, filtered using a 0.2-μm filter, and stored at −80°C.

SDS-PAGE of secreted proteins.

Exoproteins in S. aureus culture supernatants were precipitated with 10% (vol/vol) trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The precipitated proteins were washed once with 100% ethanol, air dried, resuspended with 30 μl of SDS-Laemmli buffer, and boiled at 95°C for 10 min. Precipitated exoproteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated with combinations of polyclonal antibodies against LukA (20), LukB (20), LukS-PV (29), and/or alpha-toxin (30) which were detected with Alexa Fluor 680-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary (Invitrogen) antibody diluted 1:25,000. Membranes were scanned using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor Biosciences).

Cytotoxicity and membrane damage assays.

Viability of mammalian cells and integrity of mammalian cell membranes after intoxication with S. aureus leukocidins were evaluated as previously described (18, 20, 23). Briefly, cells were plated at 1 × 105/well and intoxicated for 1 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, with the indicated concentrations of purified recombinant toxins. Cell viability was monitored with CellTiter (Promega). The colorimetric reaction was measured at 492 nm using a PerkinElmer Envision 2103 Multilabel reader. Percent viable cells were calculated using the following equation: % viability = 100 × [(A492 sample − A492 Triton X-100)/(A492 tissue culture medium)]. Membrane damage was monitored with the fluorescent dyes SYTOX green and ethidium bromide (EtBr) used at 0.1 μM and 5 μg/ml, respectively. SYTOX green and EtBr fluorescence was measured using a PerkinElmer Envision 2103 Multilabel reader with excitation at 504 nm and emission at 523 nm for SYTOX and excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm for EtBr.

In vitro and ex vivo infections with S. aureus.

S. aureus-mediated killing of PMNs by extracellular bacteria or phagocytosed bacteria was determined as previously described (18, 23). Briefly, S. aureus strains were normalized to an OD600 of 1.0, which represents approximately 1.0 × 109 CFU/ml, using a spectrophotometer (Genesys 20; Thermo Scientific) following subculture. To monitor PMN killing by phagocytosed S. aureus, bacteria were opsonized with 20% normal human serum (NHS; SeraCare) and synchronized with PMNs to promote phagocytosis. PMNs were plated at 1 × 105 cells/well and were infected with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100, 50, 10, or 1 of the S. aureus strains for 1 h. Membrane disruption was evaluated using SYTOX green as described above. MOIs were confirmed by serially diluting the input cultures and counting CFU on tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates.

PMN-mediated killing of S. aureus and subsequent growth rebound of S. aureus were monitored as previously described (18, 23). Briefly, S. aureus strains were opsonized and 1 × 105 PMNs/well were synchronized with an MOI of 10 of the S. aureus strains. At 30, 60, 120, and 180 min postsynchronization, the PMNs were lysed with 0.1% saponin on ice for 15 min and then serially diluted in 10-fold dilutions in TSB. Input at time zero was also saponin treated in RPMI plus HEPES (equal to an MOI of 10) and serially diluted in 10-fold dilutions in TSB. Recovered bacteria were enumerated by counting CFU on TSA plates where CFU at each time point were first normalized to input CFU for each strain. Input was set at 100%, and data represent percent growth compared to input.

Detection of LukAB dimers in solution.

To detect dimers in solution, purified WT LukAB or LukAB mutants were treated with 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, or 2 mM glutaraldehyde. The samples were cross-linked in 100 μl of 20 mM HEPES at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.1 M Tris, pH 8.0. To detect dimers in S. aureus culture supernatant, culture filtrate from Newman ΔspA/Δsbi subcultured 1:100 in RPMI+CAS for 5 h at 37°C, 180 rpm, was collected as described above. Fifty microliters of supernatant was treated with glutaraldehyde at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 mM in a 100-μl final volume brought up with 20 mM HEPES and cross-linked as described above.

Purification of FLAG-tagged CD11b I domains and dot blot analysis to study LukAB–I-domain interactions.

Recombinant human I domain was generated and purified from E. coli as described previously (18). Competitive dot blot analysis was performed as described previously (18).

SPR analysis of LukAB binding to Mac-1 and the human CD11b I domain.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) was run using the Biacore T100 system (GE) with both Mac-1 (R&D) and CD11b I domain as described previously (18) with the following modifications. A solvent correction was added consisting of a dilution series of Tris-buffered saline, pH 8.0, from 10% to 0.078% across a 1:2 serial dilution.

Circular dichroism analysis of WT LukAB and the 10C and E323A mutants.

Circular dichroism data were collected using a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter and a Peltier temperature control unit. Wild-type LukAB, E323A, and Δ10C proteins were in a 10 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.5 at concentrations of 5 to 6 μM, respectively. Data were collected at 208 nm using a 1-mm cuvette at every degree from 4 to 95°C at 60°C/hour.

Statistics.

Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's multiple comparison posttest (GraphPad Prism version 5.0; GraphPad Software) unless indicated otherwise.

RESULTS

LukAB forms heterodimers in solution.

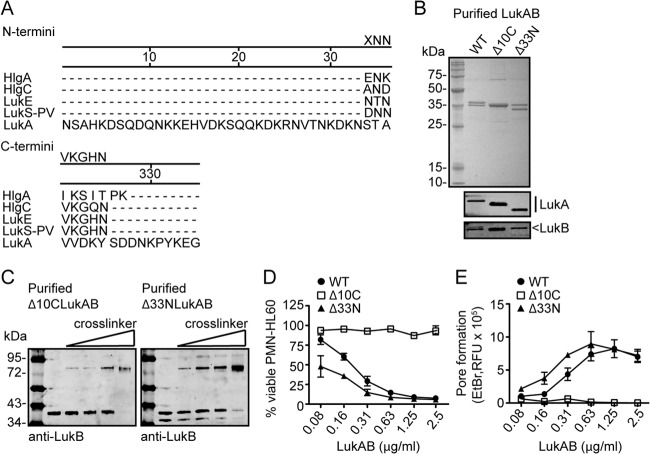

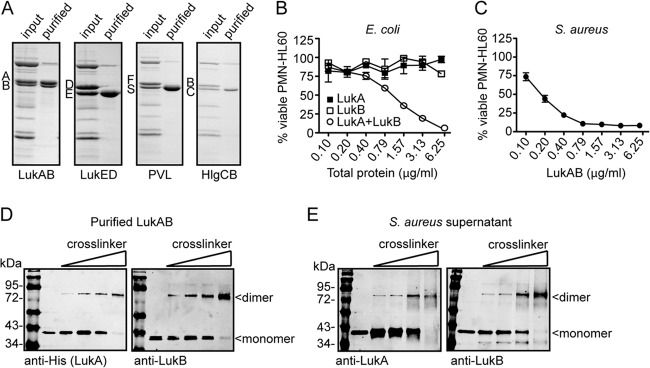

In our initial study with LukAB, we purified the toxin as separate subunits from E. coli (20). Consistent with the properties of the other bicomponent leukotoxin family members, the individual LukA and LukB purified subunits were inactive but exhibited cytotoxic activity toward target cells when combined (20). However, the cytolytic activity achieved by combining the individually purified subunits did not reflect the potency of endogenously produced LukAB from S. aureus culture filtrate. Furthermore, the individual subunits were highly unstable when purified in this manner. In order to facilitate biochemical studies with LukAB, we devised a plasmid-based approach to produce and purify His-tagged LukA from S. aureus under the supposition that the toxin would be of better quality when purified from its native organism. For these studies, we employed a “toxinless” S. aureus strain in the Newman background, which does not produce LukAB, LukED, γ-hemolysin, or α-hemolysin due to gene disruption or deletion (ΔlukED Δhla::ermC ΔhlgACB::tet ΔlukAB::spec) (14) and does not produce PVL because the strain lacks this locus (24). For simplicity, we have designated this strain Newman ΔΔΔΔ. We first attempted to purify LukA from Newman ΔΔΔΔ using a construct that coproduced His-tagged LukA and untagged LukB. Surprisingly, purification of His-tagged LukA from culture filtrate by nickel-affinity chromatography resulted in copurification of untagged LukB (Fig. 1A). To ensure that this finding was not an artifact of the construct or purification process, we also produced LukED, PVL, and HlgCB in Newman ΔΔΔΔ where only the S subunits (LukE, LukS-PV, and HlgC) were His tagged. Purification of these S subunits did not result in copurification of the F subunits (Fig. 1A), suggesting that this property is unique to LukAB. Evaluation of the activity of the LukAB purified from S. aureus revealed that this toxin was 5-fold more toxic toward cells than the combination of individually purified LukA and LukB subunits from E. coli (Fig. 1B and C).

FIG 1.

LukAB exists as a heterodimer in solution and in S. aureus culture filtrate. (A) Purification of His-tagged leukotoxin S subunits (LukA, LukE, LukS-PV, and HlgC) in the presence of F subunits (LukB, LukD, LukF-PV, and HlgB) by metal affinity chromatography. Total protein staining shows input and purified fractions. (B) Intoxication of PMN-HL60 cells with E. coli purified LukA and LukB as individual or combined subunits at the indicated concentrations for 1 h. Cell viability was determined by measuring cellular metabolism with CellTiter. (C) Intoxication of PMN-HL60 cells with LukAB as a copurified heterodimer from S. aureus at the indicated concentrations for 1 h. Cell viability was monitored with CellTiter. (D) Immunoblot of purified LukAB incubated with 0, 1, 2, or 4 mM glutaraldehyde where LukA or LukB was detected with anti-His (LukA) or anti-LukB antibodies. (E) Immunoblot of S. aureus culture filtrate incubated with 0, 1, 2, or 4 mM glutaraldehyde where LukA or LukB was detected with anti-LukA or anti-LukB antibodies. For panels B and C, data are represented as the averages of triplicate samples ± standard deviations from at least two independent experiments.

Cross-linking and immunoblotting analyses revealed that LukAB purified from S. aureus formed a complex that migrated at approximately 72 kDa, consistent with the formation of heterodimers (LukA is ∼37 kDa and LukB is ∼35 kDa) (Fig. 1D). Of note, we found that LukAB also formed similar heterodimers in S. aureus culture supernatants when produced endogenously from its native locus (Fig. 1E). Based on these findings, we concluded that the physiological state of LukAB, unlike the other bicomponent leukotoxins, is a heterodimer.

The unique N- and C-terminal extensions of LukA influence toxin activity.

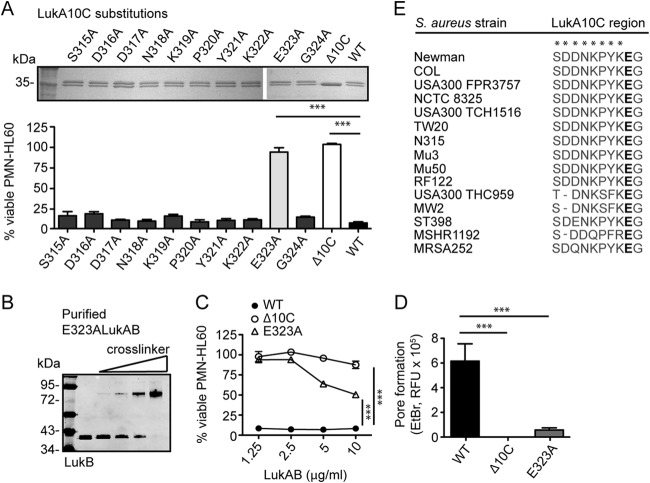

The most striking difference in the amino acid sequence between LukAB and the other leukotoxins is that secreted LukA has unique 33-amino-acid N-terminal and 10-amino-acid C-terminal extensions (Fig. 2A). To investigate the role of these extensions in LukAB biology, we engineered toxins that lack the N-terminal (Δ33N) or the C-terminal (Δ10C) extension and purified them from S. aureus culture filtrates. Deletion of these extensions did not influence copurification with LukB (Fig. 2B) or the formation of heterodimers in solution (Fig. 2C), demonstrating that these extensions are not involved in LukAB dimerization.

FIG 2.

The distinct LukA N- and C-terminal extensions affect the cytolytic activity of LukAB. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of the leukotoxin S-subunit N and C termini using DNAStar MegAlign software. (B) Purification of the His-tagged wild-type (WT) LukA, LukA C-terminal deletion mutant (Δ10C), or LukA N-terminal deletion mutant (Δ33N) and copurification of LukB by metal affinity chromatography from S. aureus. Total protein staining of 2 μg of the purified products and immunoblotting with anti-His and anti-LukB to detect the LukA and LukB subunits, respectively, are shown. (C) Immunoblot of purified Δ10C LukAB or Δ33N LukAB incubated with 0, 1, 2, or 4 mM glutaraldehyde where LukB was detected with an anti-LukB antibody. (D and E) Intoxication of PMN-HL60 cells with the indicated concentrations of the WT, Δ10C, or Δ33N LukAB proteins for 1 h. Cell viability was measured with CellTiter (D), and pore formation was evaluated with the fluorescent dye ethidium bromide (EtBr) (E). For panels D and E, data are represented as the averages of triplicate samples ± standard deviations from at least two independent experiments. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

We next tested the activity of purified Δ33N and Δ10C LukAB toxins. Incubating cells with various toxin concentrations and measuring cell viability revealed that deletion of the LukA N terminus modestly increased LukAB cytotoxicity (Fig. 2D). In contrast, deletion of the LukA C terminus rendered LukAB noncytotoxic toward cells (Fig. 2D). Consistent with these findings, evaluation of toxin pore formation on target cell membranes, via measurement of ethidium bromide incorporation, revealed that the Δ33N mutant promotes the formation of pores compared to WT LukAB. In contrast, the Δ10C mutant was unable to form measurable pores (Fig. 2E), indicating that the 10C region is essential for LukAB cytotoxicity.

A single-amino-acid substitution at the C terminus of LukA blocks LukAB cytotoxic activity.

We next performed alanine-scanning mutagenesis on the 10 amino acids comprising the mature LukA C-terminal extension to identify potential residues involved in LukAB activity. The 10 LukA mutants with alanine substitutions were purified from S. aureus as dimers with LukB (Fig. 3A) and used to intoxicate cells. This analysis revealed that a single-amino-acid substitution at glutamic acid residue 323 of the mature LukA C-terminal region, LukA E323A, rendered LukAB noncytolytic at a concentration 2.5-fold higher than the 90% lethal dose (LD90) of the WT toxin (Fig. 3A). None of the other amino acid substitutions affected LukAB cytotoxicity at this toxin concentration, indicating that the glutamic acid residue is critical for LukAB cytotoxic activity (Fig. 3A). The E323A mutant exhibited residual cytolytic activity when used at concentrations 5- to 10-fold higher than the LD90 of the WT toxin (Fig. 3B and C). The significance of E323 for LukAB activity is further emphasized by the observation that none of the LukA sequences available to date exhibit polymorphisms at this residue, despite considerable sequence diversity at nearly all other C-terminal residues (Fig. 3E).

FIG 3.

The glutamic acid residue at position 323 of the LukA C terminus is essential for LukAB activity. (A) Copurification of the His-tagged single-amino-acid LukA C-terminal mutants with LukB from S. aureus culture filtrates by metal affinity chromatography. Total protein staining of 2 μg of the purified products with purified WT and Δ10C LukAB shown for comparison (top) and corresponding cytotoxicity data after a 1-hour intoxication of PMN-HL60 cells with 2.5 μg/ml of the indicated proteins. (B) Immunoblot of purified E323A LukAB incubated with 0, 1, 2, or 4 mM glutaraldehyde where LukB was detected with an anti-LukB antibody. (C) Intoxication of PMN-HL60 cells with high concentrations of WT, Δ10C, or E323A LukAB. Cell viability was measured with CellTiter. (D) Pore formation by WT, Δ10C, or E323A LukAB on PMN-HL60 cells following a 1-hour intoxication with 10 μg/ml of toxin, as determined by EtBr incorporation. (E) Sequence alignment of the 10 amino acids composing the C-terminal region of LukA from representative S. aureus strains in the protein database (NCBI) was performed using the NCBI BLAST protein. The glutamic acid at position 323 is highlighted in bold, and residues with observed polymorphisms are marked with asterisks. Data are represented as the averages of triplicate samples ± standard deviations from at least two independent experiments. *** indicates P < 0.0001 by one-way analysis of variance.

The glutamic acid at position 323 of LukA is required for LukAB activity in ex vivo infection of human PMNs.

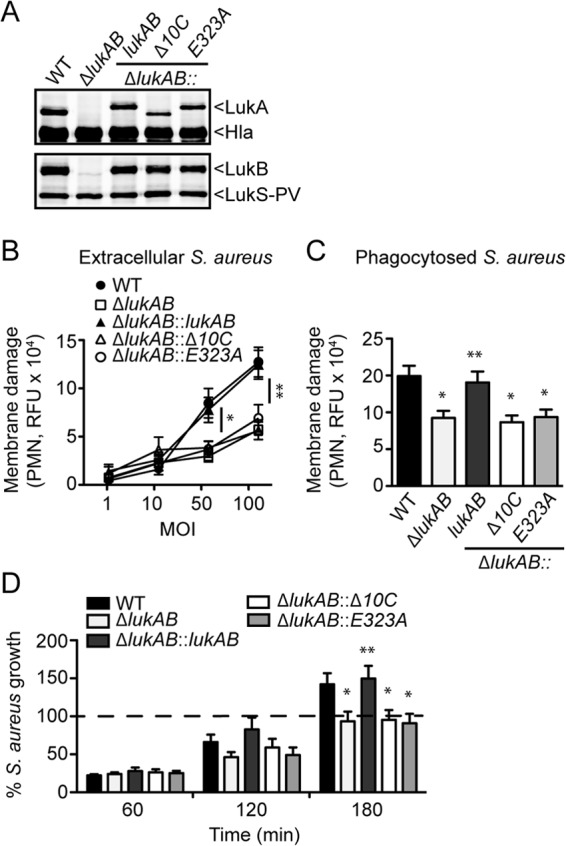

LukAB is responsible for killing human PMNs during ex vivo infections with clinically relevant S. aureus strains (20), including the epidemic methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) clone USA300 (18, 20, 21, 23). Because the E323A LukA mutant exhibited residual cytolytic activity at high concentrations, we determined whether this activity was sufficient for LukAB-mediated killing of PMNs during ex vivo infection with USA300. We employed a collection of isogenic strains where the WT lukAB, Δ10ClukAB, or E323AlukAB locus was integrated in single copy into the chromosome of a USA300 ΔlukAB strain (23). Restoration of LukAB production in these strains was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4A). In all complemented strains, LukA contains an N-terminal His tag, which explains the difference in size between endogenous LukA and the complemented LukA (Fig. 4A). LukS-PV and Hla levels were also evaluated to confirm that the complementation strategy did not affect the production of other exotoxins (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

The E323 residue in the C terminus of LukA is essential for LukAB-mediated killing of PMNs by extracellular and phagocytosed USA300. (A) Immunoblotting to detect LukA, LukB, LukS-PV, and Hla levels in WT, ΔlukAB, and ΔlukAB strains chromosomally complemented with WT lukAB or lukAB with the indicated C-terminal mutations using toxin-specific antibodies. (B) Infection of human PMNs for 1 h with various MOIs of the indicated USA300 strains under nonphagocytosing conditions. PMN membrane damage was evaluated with the fluorescent dye SYTOX green. (C) Infection of human PMNs for 1 h with an MOI of 10 of the indicated opsonized USA300 strains under phagocytosing conditions. PMN membrane damage was evaluated with the fluorescent dye SYTOX green. (D) Growth rebound of the indicated opsonized USA300 strains during infection with human PMNs at an MOI of 10 under phagocytosing conditions. Bacterial CFU were determined at 60, 120, or 180 min postsynchronization and were normalized to input at time zero, which was set at 100%. For panels B to D, results represent the means from PMNs isolated from 6 donors ± standard errors of the means from at least two independent experiments. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, and *** indicates P < 0.0001 by one-way analysis of variance.

We have shown that both extracellular and phagocytosed S. aureus strains utilize LukAB to kill primary human PMNs (18, 20, 23). To determine whether E323 is required for this dual activity, human PMNs were infected with WT and ΔlukAB USA300, as well as the complementation strains described above, under both phagocytosing and nonphagocytosing conditions. We found that in contrast to the strain complemented with WT lukAB, complementation with Δ10ClukAB or E323AlukAB did not restore the virulence of extracellular or phagocytosed USA300 ΔlukAB (Fig. 4B and C).

We have previously established that LukAB-mediated killing of PMNs by phagocytosed USA300 results in bacterial escape and subsequent outgrowth (18, 23). Compared to WT LukAB, strains producing the mutant proteins were unable to restore bacterial outgrowth to phagocytosed USA300 ΔlukAB as evidenced by enumeration of bacterial CFU (Fig. 4D). Together, these results demonstrate that a single-amino-acid substitution at E323 is sufficient to disrupt LukAB-mediated function during ex vivo infection of PMNs.

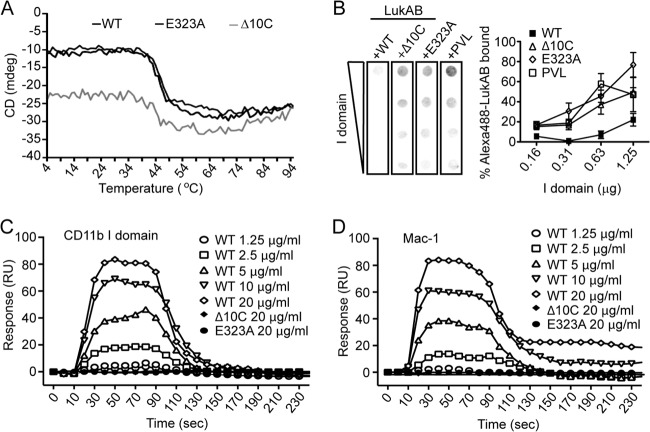

The glutamic acid at position 323 of LukA is required for binding to CD11b.

Although the Δ10C and E323A mutations did not display defects in dimerization with LukB (Fig. 2 and 3), circular dichroism analysis was performed to ensure that the structure of these proteins was not affected by the mutations. The E323A point mutation had no noticeable effect on the structure of LukAB, as there was no difference in the melting curves of WT LukAB and E323A LukAB (Fig. 5A). Deletion of the C-terminal 10 amino acids of LukA did slightly affect the shape of the melting curve, but this is more likely due to the deletion itself rather than a change in structure (Fig. 5A). The melting temperatures for LukAB, E323A LukAB, and Δ10C LukAB were 45.8°C, 47.0°C, and 43.0°C, respectively, indicating that the three proteins are similarly structured.

FIG 5.

The interaction between LukAB and its receptor CD11b requires the E323 residue in the C terminus of LukA. (A) Circular dichroism (CD) analyses indicate that the wild-type (black), E323A (dark gray), and Δ10C (gray) proteins are stable and properly folded, with similar melting temperatures, 45.8°C, 47.0°C, and 43.0°C, respectively. Temperature melts were conducted from 4 to 95°C at a wavelength of 208 nm. (B) Competition dot blot assay where purified recombinant human CD11b I domain was membrane bound and then incubated with 5 μg/ml fluorescently labeled LukAB (Alexa 488-LukAB) in the presence of a 10-fold excess (50 μg/ml) of unlabeled WT LukAB, the 10C or E323A LukAB mutant, or PVL. Alexa 488-LukAB binding was quantified by densitometry. Data represent the averages of triplicate samples ± standard errors of the means from at least two independent experiments. (C and D) Measurement of the interaction of LukAB with human CD11b I domain (C) or human Mac-1 (D) by SPR. Representative sensorgrams of two experiments performed in triplicate are shown. RU, relative units.

We recently identified CD11b, the αM component of the αMβ2 integrin, also known as Mac-1, as a cellular receptor required for LukAB-mediated killing of human PMNs (18). Thus, we examined if the lack of cytotoxic activity observed with the LukA C-terminal mutants was due to impaired binding of LukAB to CD11b. To this end, we attempted to compete the binding of fluorescently labeled WT LukAB (Alexa 488-LukAB) to the human CD11b I domain, previously shown to be required for LukAB binding (18), with excess unlabeled Δ10C and E323A LukAB using dot blot analysis (Fig. 5B) (18). The bicomponent leukotoxin PVL, which utilizes the C5a receptors for cell targeting (17) and does not interact with CD11b (18), was included as a negative control. As previously observed (18), unlabeled WT LukAB efficiently competed off the binding of Alexa 488-LukAB to the CD11b I domain (Fig. 5B). However, the Δ10C and E323A LukAB mutants, like PVL, were unable to compete off Alexa 488-LukAB (Fig. 5B). We further complemented these studies by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analyses. The dissociation constant (Kd) for the interaction between WT LukAB and recombinant CD11b I domain or purified Mac-1 was 1.9 nM or 38 nM, respectively (18). In contrast, no interaction was detected between Δ10C or E323A LukAB and the CD11b I domain or the Mac-1 integrin (Fig. 5C and D). These data provide a molecular explanation for why the Δ10C and E323A LukAB are impaired in PMN killing.

DISCUSSION

The bicomponent leukotoxins are a family of virulence factors utilized by S. aureus to target and kill immune cells (2, 3). The current model for bicomponent leukotoxin pore formation is based on studies with PVL and γ-hemolysin (10, 19, 31, 32). According to this model, the leukotoxin subunits can be found as monomers in solution (11) and form higher-order structures only when they encounter each other on the target cell plasma membrane (10). In contrast to the other leukotoxins, we found that LukAB forms a dimer in solution, suggesting that this toxin bypasses the recruitment step in pore formation and approaches the target cell membrane partially preassembled. Of note, when HlgA and HlgB were genetically fused with a serine/glycine linker, the ligated dimeric toxin was shown to be more potent than the wild-type monomeric subunits, most likely due to elimination of the recruitment step (33). Similarly, the purified LukAB heterodimer from S. aureus is more potent than the combination of separately purified LukA and LukB from E. coli. The discovery that LukAB dimerizes in solution was not an artifact of the purified toxins, as LukAB dimers were also detected in S. aureus supernatants. These results highlight unique properties of LukAB and suggest that it is more physiologically relevant to purify and study LukAB as a heterodimer. Whether or not LukAB is secreted by S. aureus as a dimer or if the subunits assemble into dimers postsecretion remains to be elucidated.

LukAB also diverges from the other bicomponent leukotoxins in that its S subunit LukA has distinctive extensions at the N and C termini of the protein. In this study, we found that these regions are important for LukAB cytolytic activity. Deletion of the LukA N terminus results in a modest increase in the potency of LukAB toward target cells. The mechanism by which this occurs has yet to be determined. In contrast to the N-terminal deletion, deletion of the LukA C terminus resulted in a noncytolytic form of LukAB, which could not kill human PMNs in various ex vivo models of infection. These results are similar to those found with γ-hemolysin subunits where truncation mutagenesis revealed that the C terminus of both HlgA and HlgB is required for toxin activity, but deletion of the N terminus did not have detrimental effects on toxin activity (34). We were able to further map LukA cytotoxic activity to a single amino acid, as replacement of the glutamic acid residue at position 323 in the LukA C terminus phenocopied the C-terminal truncation mutant for both cytotoxicity and ex vivo infection defects on human PMNs. Multiple biochemical analyses revealed that these mutations impaired binding of LukAB to CD11b, demonstrating the importance of the LukA C terminus in receptor recognition.

Mapping the region of LukA required for the interaction between LukAB and its cellular target could have implications for the development of novel therapeutics aimed at disrupting the LukAB-CD11b interaction. Moreover, the identification of inactivating mutations provides the basis for the development of LukAB toxoids that could be incorporated into new vaccines to combat S. aureus infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by funds from the American Heart Association (09SDG2060036) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIAID-NIH) under award numbers R01AI099394 and R01AI105129 to V.J.T. A.L.D. was supported by an NIAID-NIH training grant (5T32AI007180), F.A. was supported initially by an NIAID-NIH training grant (5T32AI007180) and later by an NIAID-NIH postdoctoral fellowship (F32AI098395), and X.L. was supported by the NYULMC's Summer Undergraduate Research Program. M.P.J. was supported by NHMRC program grant 565526 and a Smart Futures Fund Research Partnerships program grant.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We thank the Torres laboratory members for critical reading of the manuscript.

A.L.D., F.A., and V.J.T. are listed as inventors on patent applications filed by New York University School of Medicine, which are currently under commercial license.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Rigby KM, DeLeo FR. 2012. Neutrophils in innate host defense against Staphylococcus aureus infections. Semin. Immunopathol. 34:237–259. 10.1007/s00281-011-0295-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandenesch F, Lina G, Henry T. 2012. Staphylococcus aureus hemolysins, bi-component leukocidins, and cytolytic peptides: a redundant arsenal of membrane-damaging virulence factors? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2:12. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonzo F, III, Torres VJ. 2013. Bacterial survival amidst an immune onslaught: the contribution of the Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxins. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003143. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoong P, Torres VJ. 2013. The effects of Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxins on the host: cell lysis and beyond. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16:63–69. 10.1016/j.mib.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panton PN, Valentine FCO. 1932. Staphylococcal toxin. Lancet i:506–508 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith ML, Price SA. 1938. Staphylococcus γ haemolysin. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 47:379–393. 10.1002/path.1700470303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedelacq JD, Maveyraud L, Prevost G, Baba-Moussa L, Gonzalez A, Courcelle E, Shepard W, Monteil H, Samama JP, Mourey L. 1999. The structure of a Staphylococcus aureus leucocidin component (LukF-PV) reveals the fold of the water-soluble species of a family of transmembrane pore-forming toxins. Structure 7:277–287. 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80038-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillet V, Roblin P, Werner S, Coraiola M, Menestrina G, Monteil H, Prevost G, Mourey L. 2004. Crystal structure of leucotoxin S component: new insight into the Staphylococcal beta-barrel pore-forming toxins. J. Biol. Chem. 279:41028–41037. 10.1074/jbc.M406904200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson R, Nariya H, Yokota K, Kamio Y, Gouaux E. 1999. Crystal structure of staphylococcal LukF delineates conformational changes accompanying formation of a transmembrane channel. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:134–140. 10.1038/5821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamashita K, Kawai Y, Tanaka Y, Hirano N, Kaneko J, Tomita N, Ohta M, Kamio Y, Yao M, Tanaka I. 2011. Crystal structure of the octameric pore of staphylococcal gamma-hemolysin reveals the beta-barrel pore formation mechanism by two components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:17314–17319. 10.1073/pnas.1110402108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodin AM. 1960. Purification of the two components of leucocidin from Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem. J. 75:158–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colin DA, Mazurier I, Sire S, Finck-Barbancon V. 1994. Interaction of the two components of leukocidin from Staphylococcus aureus with human polymorphonuclear leukocyte membranes: sequential binding and subsequent activation. Infect. Immun. 62:3184–3188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonzo F, III, Kozhaya L, Rawlings SA, Reyes-Robles T, DuMont AL, Myszka DG, Landau NR, Unutmaz D, Torres VJ. 2013. CCR5 is a receptor for Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin ED. Nature 493:51–55. 10.1038/nature11724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyes-Robles T, Alonzo F, III, Kozhaya L, Lacy DB, Unutmaz D, Torres VJ. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin ED targets the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 to kill leukocytes and promote infection. Cell Host Microbe 14:453–459. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokota K, Kamio Y. 2000. Tyrosine72 residue at the bottom of rim domain in LukF crucial for the sequential binding of the staphylococcal gamma-hemolysin to human erythrocytes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:2744–2747. 10.1271/bbb.64.2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DuMont AL, Torres VJ. 2014. Cell targeting by the Staphylococcus aureus pore-forming toxins: it's not just about lipids. Trends Microbiol. 22:21–27. 10.1016/j.tim.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spaan AN, Henry T, van Rooijen WJ, Perret M, Badiou C, Aerts PC, Kemmink J, de Haas CJ, van Kessel KP, Vandenesch F, Lina G, van Strijp JA. 2013. The staphylococcal toxin Panton-Valentine leukocidin targets human c5a receptors. Cell Host Microbe 13:584–594. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DuMont AL, Yoong P, Day CJ, Alonzo F, III, McDonald WH, Jennings MP, Torres VJ. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus LukAB cytotoxin kills human neutrophils by targeting the CD11b subunit of the integrin Mac-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:10794–10799. 10.1073/pnas.1305121110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayasinghe L, Bayley H. 2005. The leukocidin pore: evidence for an octamer with four LukF subunits and four LukS subunits alternating around a central axis. Protein Sci. 14:2550–2561. 10.1110/ps.051648505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumont AL, Nygaard TK, Watkins RL, Smith A, Kozhaya L, Kreiswirth BN, Shopsin B, Unutmaz D, Voyich JM, Torres VJ. 2011. Characterization of a new cytotoxin that contributes to Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 79:814–825. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07490.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ventura CL, Malachowa N, Hammer CH, Nardone GA, Robinson MA, Kobayashi SD, DeLeo FR. 2010. Identification of a novel Staphylococcus aureus two-component leukotoxin using cell surface proteomics. PLoS One 5:e11634. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malachowa N, Kobayashi SD, Braughton KR, Whitney AR, Parnell MJ, Gardner DJ, Deleo FR. 2012. Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin GH promotes inflammation. J. Infect. Dis. 206:1185–1193. 10.1093/infdis/jis495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DuMont AL, Yoong P, Surewaard BG, Benson MA, Nijland R, van Strijp JA, Torres VJ. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus elaborates leukocidin AB to mediate escape from within human neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 81:1830–1841. 10.1128/IAI.00095-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba T, Bae T, Schneewind O, Takeuchi F, Hiramatsu K. 2008. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes: polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J. Bacteriol. 190:300–310. 10.1128/JB.01000-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duthie ES, Lorenz LL. 1952. Staphylococcal coagulase; mode of action and antigenicity. J. Gen. Microbiol. 6:95–107. 10.1099/00221287-6-1-2-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boles BR, Thoendel M, Roth AJ, Horswill AR. 2010. Identification of genes involved in polysaccharide-independent Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS One 5:e10146. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres VJ, Attia AS, Mason WJ, Hood MI, Corbin BD, Beasley FC, Anderson KL, Stauff DL, McDonald WH, Zimmerman LJ, Friedman DB, Heinrichs DE, Dunman PM, Skaar EP. 2010. Staphylococcus aureus fur regulates the expression of virulence factors that contribute to the pathogenesis of pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 78:1618–1628. 10.1128/IAI.01423-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alonzo F, III, Benson MA, Chen J, Novick RP, Shopsin B, Torres VJ. 2012. Staphylococcus aureus leucocidin ED contributes to systemic infection by targeting neutrophils and promoting bacterial growth in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 83:423–435. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07942.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoong P, Pier GB. 2010. Antibody-mediated enhancement of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:2241–2246. 10.1073/pnas.0910344107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menzies BE, Kernodle DS. 1996. Passive immunization with antiserum to a nontoxic alpha-toxin mutant from Staphylococcus aureus is protective in a murine model. Infect. Immun. 64:1839–1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aman MJ, Karauzum H, Bowden MG, Nguyen TL. 2010. Structural model of the pre-pore ring-like structure of Panton-Valentine leukocidin: providing dimensionality to biophysical and mutational data. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 28:1–12. 10.1080/073911010010524952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miles G, Movileanu L, Bayley H. 2002. Subunit composition of a bicomponent toxin: staphylococcal leukocidin forms an octameric transmembrane pore. Protein Sci. 11:894–902. 10.1110/ps.4360102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roblin P, Guillet V, Joubert O, Keller D, Erard M, Maveyraud L, Prevost G, Mourey L. 2008. A covalent S-F heterodimer of leucotoxin reveals molecular plasticity of beta-barrel pore-forming toxins. Proteins 71:485–496. 10.1002/prot.21900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miles G, Jayasinghe L, Bayley H. 2006. Assembly of the bi-component leukocidin pore examined by truncation mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 281:2205–2214. 10.1074/jbc.M510842200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]