Abstract

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC; thrush) is an opportunistic fungal infection caused by the commensal microbe Candida albicans. Immunity to OPC is strongly dependent on CD4+ T cells, particularly those of the Th17 subset. Interleukin-17 (IL-17) deficiency in mice or humans leads to chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, but the specific downstream mechanisms of IL-17-mediated host defense remain unclear. Lipocalin 2 (Lcn2; 24p3; neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin [NGAL]) is an antimicrobial host defense factor produced in response to inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-17. Lcn2 plays a key role in preventing iron acquisition by bacteria that use catecholate-type siderophores, and lipocalin 2−/− mice are highly susceptible to infection by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. The role of Lcn2 in mediating immunity to fungi is poorly defined. Accordingly, in this study, we evaluated the role of Lcn2 in immunity to oral infection with C. albicans. Lcn2 is strongly upregulated following oral infection with C. albicans, and its expression is almost entirely abrogated in mice with defective IL-17 signaling (IL-17RA−/− or Act1−/− mice). However, Lcn2−/− mice were completely resistant to OPC, comparably to wild-type (WT) mice. Moreover, Lcn2 deficiency mediated protection from OPC induced by steroid immunosuppression. Therefore, despite its potent regulation during C. albicans infection, Lcn2 is not required for immunity to mucosal candidiasis.

INTRODUCTION

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC; thrush) is an opportunistic infection associated with CD4+ T cell loss and is caused by the commensal fungus Candida albicans. Individuals with HIV/AIDS are particularly prone to this disease, and OPC is considered an AIDS-defining illness (1, 2). In addition, OPC is common in patients taking immunodepleting chemotherapy, infants and the elderly, and patients with congenital immunodeficiencies, such as hyper-IgE syndrome (HIES) (3). OPC exhibits considerable morbidity and can cause impaired nutrition due to odynophagia (pain with swallowing) and failure to thrive in infants. To date, there are no clinically available vaccines for C. albicans, or indeed for any fungal pathogens (4, 5).

The cytokine interleukin 17 (IL-17; also known as IL-17A) is tightly associated with immunity to OPC (6). Mice lacking either IL-17 receptor subunit (IL-17RA and IL-17RC) are highly susceptible to OPC. Similarly, mice lacking IL-23 (either the IL-12p40 or the IL-23p19 subunit), a cytokine that induces IL-17-producing cells, are also susceptible (7–9). In agreement with the findings for mice, humans with mutations in IL-17RA or its ligand IL-17F suffer from chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), characterized by both OPC and dermal candidiasis (10). In addition, neutralizing anti-IL-17 antibodies in autoimmune regulator (AIRE) deficiency or in some thymomas are linked to susceptibility to OPC (11, 12). IL-17 signals through an adaptor protein, Act1 (also known as CIKS) (13), and Act1-deficient humans were recently identified on the basis of their susceptibility to recurrent CMC (14). Antibodies against IL-17 and its receptor are currently in clinical trials for the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis (15–18), but the potential adverse effects of these therapies are still not well defined. On the basis of the evidence outlined above, OPC and CMC are obviously of particular concern for patients taking anti-IL-17 therapies. In fact, a recent report indicates that patients on anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drugs for inflammatory bowel disease show an increased risk of candidiasis, which had not been previously recognized (19).

Although IL-17 signaling is clearly essential for immunity to OPC, the downstream mechanisms by which IL-17 mediates immunity to this fungus remain largely unknown. IL-17 signaling induces a program of gene expression associated with innate immune responses, including cytokines (IL-6, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF]), chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, CCL20), and antimicrobial peptides (β-defensins and S100A8/9) (13). One of the most strongly induced IL-17 target genes encodes lipocalin 2 (Lcn2), which is regulated at the transcriptional level by IL-17 either alone or in conjunction with TNF-α (20–22). IL-17 signaling in a variety of cell types induces Lcn2 expression (20), and lcn2 mRNA is one of many IL-17 signature genes induced in the oral mucosa following C. albicans infection (7).

Lipocalin 2, also known as 24p3, uterocalin, or neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), is an acute-phase protein produced by the liver and also by mesenchymal and epithelial cells in response to inflammatory cytokines. Lcn2 plays a key role in preventing iron acquisition by bacteria that use catecholate-type siderophores (23, 24). Accordingly, Lcn2−/− mice are highly susceptible to infection by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae (25–27), bacterial species that use this type of iron-scavenging system. However, the role of Lcn2 in mediating immunity to fungi has not been a focus of investigation. Accordingly, in this study, we evaluated the role of Lcn2 in immunity to mucosal C. albicans infection. Surprisingly, Lcn2 was not required for the host defense against OPC, even though it was strongly upregulated in an IL-17-dependent manner following Candida infection. Moreover, Lcn2 deficiency appeared to mediate protection from oral thrush induced by immunosuppression, suggesting an immunoregulatory role for this protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice used and oropharyngeal candidiasis model.

Mice were on the C57BL/6 background and were age and sex matched. IL-23p19−/− mice were provided by Genentech (South San Francisco, CA), and IL-17RA−/− mice were from Amgen (Seattle, WA). Lcn2−/− mice were a kind gift from Tak Mak, University of Toronto, and have been described previously (25, 27). Act1−/− mice have been described previously (28). All mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. The genotypes of all mice were verified by PCR of ear biopsy specimens. Mice aged 7 to 10 weeks (n, 3 to 10 per experiment) were inoculated sublingually with a 0.0025-g cotton ball saturated with a C. albicans (strain CAF2-1) suspension of 2 × 107 CFU/ml for 75 min under anesthesia, as described previously (29). If indicated, mice were administered cortisone acetate intraperitoneally (i.p.) at 225 mg/kg of body weight at days −1, +1, and +3 relative to infection. The oral cavity was swabbed before each infection, and swabs were plated on YPD-AMP (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose agar plus ampicillin) agar plates to verify the absence of Candida. Mice were weighed daily. After sacrifice, the tongue of each mouse was homogenized on a gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), and serial dilutions were plated on YPD-AMP agar in triplicate for colony enumeration. Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism (version 5) by using t tests with the Mann-Whitney correction (a P value of <0.05 was considered significant). Protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh IACUC.

Histology.

Tongue tissue was prepared for histology by the Research Histology Services core of the University of Pittsburgh. Samples were stained with periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS) and were imaged at a magnification of ×10 to ×40.

RNA preparation and real-time reverse transcriptase PCR.

RNA was extracted with RNeasy kits, and cDNA was synthesized with a SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). Relative quantification of gene expression was carried out by real-time PCR with SYBR green (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD) and normalization to the expression of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene. All samples were analyzed in triplicate. Primers were from SABiosciences (Qiagen). Results were analyzed on an Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA) 7300 real-time PCR system.

RESULTS

Lcn2 is induced in an IL-17R-dependent manner during OPC.

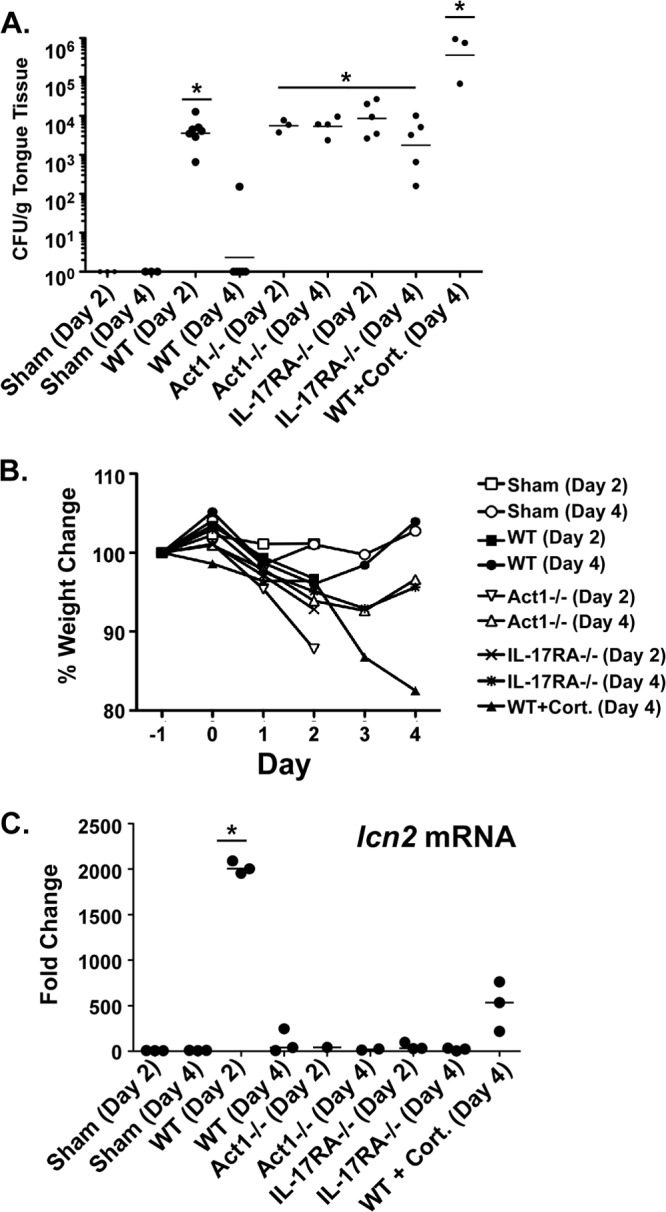

To evaluate Lcn2 expression during OPC, we infected C57BL/6 mice orally with Candida albicans (strain CAF2-1), using a standard OPC infection model with 75 min of sublingual exposure to C. albicans strain CAF2-1 (29). As controls, we subjected wild-type (WT) mice administered high-dose cortisone, IL-17RA−/− mice, and Act1−/− mice to OPC (28), since the IL-23/IL-17 pathway is known to be essential for immunity to oral candidiasis (7). We then measured the C. albicans load in the tongue at either day 2 or day 4 postinfection by plating serial dilutions of tongue homogenates onto YPD-AMP agar plates. At day 2, all animals, including WT mice, had similarly high fungal burdens, a result comparable to historical data with this model (Fig. 1A) (7). By day 4, WT mice had fully cleared the infection, whereas IL-17RA−/− and Act1−/− mice still had significant oral fungal loads. Weight loss measurements paralleled the fungal load data; WT mice fully recovered their original weight by day 4, correlating with fungal clearance, but IL-17RA−/− mice, Act1−/− mice, and cortisone-treated WT mice still showed reduced weight and persistent fungal loads (Fig. 1A and B). We then measured the expression of lcn2 mRNA from tongues taken from these mice at day 2 and day 4 postinfection. lcn2 expression was strongly induced in WT mice, but there was no detectable induction in IL-17RA−/− or Act1−/− mice, confirming that the regulation of this gene is almost entirely IL-17 dependent in this infection setting (Fig. 1C). The expression of lcn2 was not statistically different between untreated and cortisone-treated WT mice at day 4.

FIG 1.

Lcn2 mRNA is induced during oral candidiasis in an IL-17RA- and Act1-dependent manner. (A and B) IL-17RA−/− and Act1−/− mice are susceptible to OPC. The indicated groups of mice were subjected to oral infection with C. albicans. (A) At the indicated time point postinfection (day 2 or day 4), tongue tissue was harvested for colony enumeration. Each dot represents a single mouse. Horizontal lines within each set of data indicate geometric means. Asterisks indicate significant differences from results for sham-treated mice (P < 0.05) by the t test with the Mann-Whitney correction. (B) Mice were weighed daily, and the percentage of change from day −1 relative to infection is indicated. (C) lcn2 expression is impaired in IL-17RA−/− and Act1−/− mice. The expression of lcn2 at day 2 or 4 postinfection was assessed by quantitative PCR of RNA from tongue tissue from the indicated mice; the value obtained was normalized to that for GAPDH expression. Each result is the fold change from expression in sham-treated mice at the same time point. The asterisk indicates a significant difference from results for sham-treated mice (P, <0.05) by the t test with the Mann-Whitney correction.

Lipocalin 2 is dispensable for immunity to OPC.

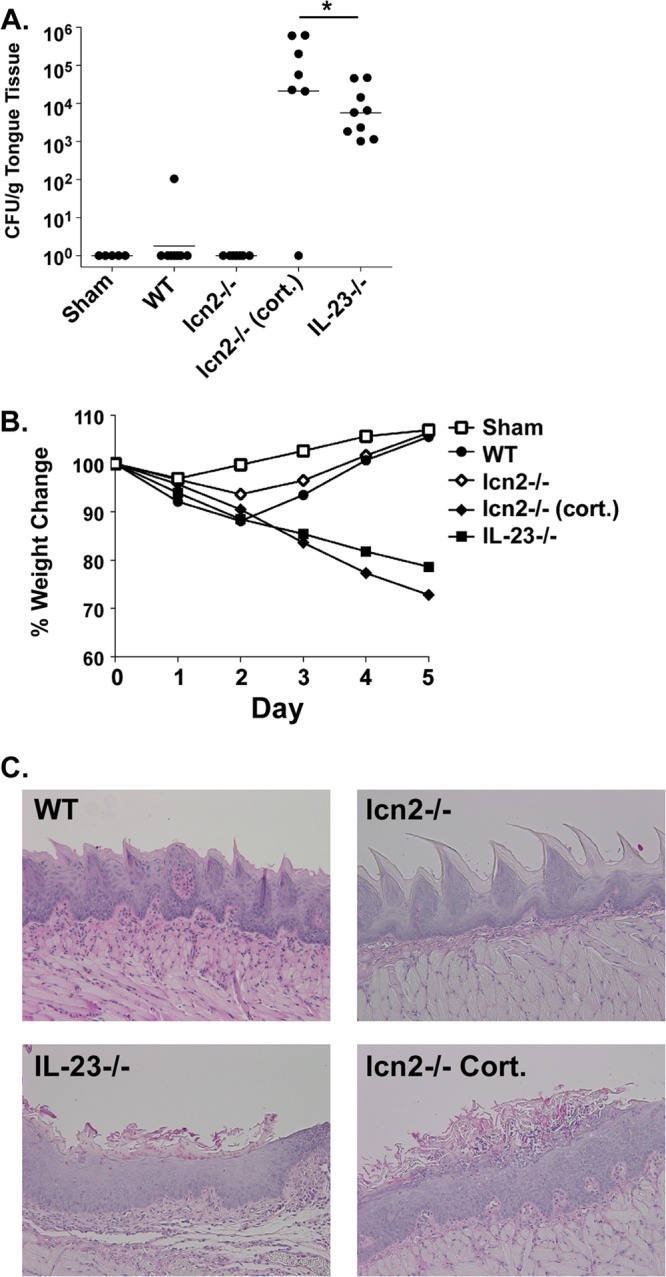

Since infection with OPC triggered upregulation of lcn2 in an IL-17- and Act1-dependent manner, we hypothesized that Lcn2 would be important for immunity to oral Candida albicans infection. Accordingly, WT or lcn2−/− mice (27) were subjected to OPC for 5 days, and fungal loads in the oral mucosa were assessed as described above. As controls, we also used IL-23−/− mice (which show the same susceptibility to OPC as IL-17RA−/− mice [8]). As an additional control, lcn2−/− mice were immunosuppressed with high-dose cortisone acetate. Both WT and lcn2−/− mice cleared the infection by day 5. However, cortisone-treated lcn2−/− mice were highly susceptible to disease, and so, to a lesser extent, were IL-23−/− mice (Fig. 2A). Weight loss tracked with susceptibility to disease; that is, mice that cleared C. albicans (WT and lcn2−/− mice) exhibited complete weight recovery, whereas IL-23−/− mice or cortisone-treated lcn2−/− mice showed progressive weight loss (Fig. 2B). In agreement with these findings, histological analysis of tongue tissue stained with periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS) (to detect yeast) showed that WT and lcn2−/− mice had normal tissue architecture, with no detectable fungal organisms, at day 5. In contrast, IL-23−/− and cortisone-treated lcn2−/− mice showed destruction of the superficial epithelial layer by hyphal and pseudohyphal forms of Candida albicans (Fig. 2C), in a manner similar to that which we observed previously for cortisone-treated WT mice or IL-17RA−/− mice (7). These results indicate that Lcn2, though strongly induced by IL-17 during the course of oral Candida exposure, is not required to mediate fungal clearance.

FIG 2.

Lcn2-deficient mice are resistant to OPC. (A) Lcn2−/− mice fully clear C. albicans after 5 days. The indicated groups of mice were subjected to oral infection with C. albicans. At 5 days postinfection, tongue tissue was harvested for colony enumeration. Each dot represents a single mouse. Horizontal lines within each set of data indicate geometric means. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (P, <0.05) by the t test with the Mann-Whitney correction. Where indicated, mice were administered cortisone acetate at days −1, 0, and +1 relative to infection (cort.). (B) Lcn2−/− mice regain weight following infection. Mice were weighed daily, and the percentage of change from day 0 relative to infection is indicated. (C) Lcn2−/− mice show clearance of C. albicans from the oral mucosa. Tongue sections from mice with the phenotypes indicated were stained with PAS.

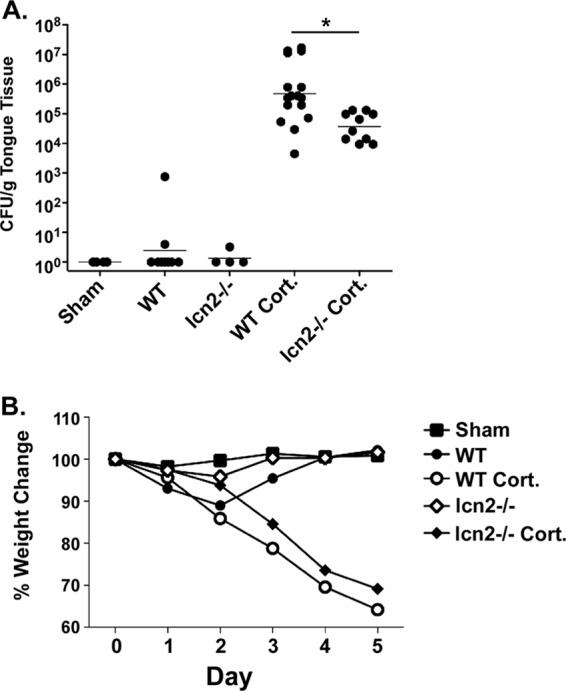

Lipocalin 2-deficient mice show enhanced resistance to OPC induced by cortisone treatment.

Since lcn2−/− mice were not susceptible to OPC, we questioned whether they might show enhanced resistance to infection. Accordingly, we compared the fungal susceptibilities of WT and lcn2−/− mice that were treated with cortisone acetate to induce immunosuppression. As shown, the fungal load in WT mice treated with cortisone was approximately 1 log unit greater than that in lcn2−/− mice treated with cortisone (4.8 × 105 compared with 3.72 × 104 CFU), a difference that was statistically significant (P, 0.0034) (Fig. 3A). In agreement with this observation, cortisone-treated lcn2−/− mice did not lose as much weight as cortisone-treated WT mice (Fig. 3B). Therefore, a deficiency in Lcn2 is associated with significant and reproducible, albeit modest, resistance to OPC.

FIG 3.

Lcn2 deficiency enhances resistance to OPC under conditions of chemical immunosuppression. (A) The indicated groups of mice were subjected to oral infection with C. albicans. At 5 days postinfection, tongue tissue was harvested for colony enumeration. Each dot represents a single mouse. Horizontal lines within each set of data indicate geometric means. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (P, <0.05) by the t test with the Mann-Whitney correction. Where indicated, mice were treated with cortisone acetate at days −1, 0, and +1 relative to infection (Cort.). (B) Following infection, Lcn2−/− mice treated with cortisone lose less weight than WT mice treated with cortisone. Mice were weighed daily, and the percentage of change from day 0 relative to infection is indicated.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, it has become clear that IL-17 is a central mediator of immunity to fungi, including C. albicans and other pathogens of fungal origin (30). The importance of IL-17 in mucocutaneous candidiasis is underscored by discoveries of patients with mutations in genes that impact the generation of Th17 cells (including STAT3, STAT1, and CARD9) or that block IL-17-mediated signaling (including IL17F, IL17RA, and ACT1) (6, 30, 31). Studies of humans also indicate that the vast majority of Candida-reactive Th cells express IL-17 (32). However, the downstream mechanisms by which IL-17 confers antifungal immunity are not well defined, and it is important to understand them in order to optimize therapies or intervention strategies for fungal diseases.

IL-17 induces numerous genes that could potentially participate in the immune response to Candida albicans. One of the most strongly induced genes in cell lines and in Candida-infected mucosal tissue encodes Lcn2 (7, 20). A variety of biological functions have been ascribed to Lcn2, including roles in the control of apoptosis and in tissue development (33, 34). Lcn2 is also a bacteriostatic factor that binds to soluble ferric siderophores expressed by Gram-negative bacteria. Siderophores help these microbes acquire nutritional iron and are essential for virulence. Consequently, mice lacking Lcn2 are sensitive to E. coli and K. pneumoniae infections (25, 26). Resistance to Lcn2 also confers a survival advantage on Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (35, 36). Thus, Lcn2 plays a role in counteracting the survival strategies used by bacteria to obtain iron.

Although Lcn2 is important in immunity to various bacteria, its role in fungal infections is poorly understood. Since lcn2 mRNA expression was strongly upregulated during oral candidiasis in a manner that was almost completely dependent on IL-17 signaling (Fig. 1) (7), we hypothesized that Lcn2 was required for immunity to OPC. However, Lcn2−/− mice were fully resistant to disease, showing the same kinetics of weight change that occur in WT mice and exhibiting no fungal load or histological evidence for fungal invasion at days 4 to 5 postinfection (Fig. 2). Our finding stands in contrast to a recent publication by Liu et al. reporting that Lcn2−/− mice are more susceptible to disseminated (bloodstream) candidiasis than WT mice (37). That report described a chemotactic defect in Lcn2−/− neutrophils, which was proposed to be the basis for their susceptibility to candidemia. Neutropenia is a more important risk factor for systemic candidiasis than for mucocutaneous candidiasis (3), which may explain why Lcn2 deficiency increases susceptibility to systemic but not mucosal C. albicans infections.

Although our finding that Lcn2 is not required for immunity to OPC was unexpected, the expression of Lcn2 in a setting where it is dispensable for immunity has a precedent. Lcn2 binds siderophores expressed by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (38), but Lcn2-deficient mice are not more susceptible to low-dose aerosol infection with M. tuberculosis than wild-type mice. In that setting, Lcn2 acts to constrain T cell activation, and Lcn2−/− mice consequently showed enhanced inflammation, which was associated with increased levels of certain gene products known to be regulated by IL-17, such as G-CSF and CXCL1 (39). Prompted by this observation, we hypothesized that Lcn2 deficiency might be associated with increased resistance to OPC. Therefore, we compared fungal loads in WT and Lcn2−/− mice subjected to chemical immunosuppression. Indeed, we found that Lcn2−/− mice had fungal burdens approximately 10-fold lower than those of WT mice, a result consistent with the reduced weight loss profile during infection (Fig. 3).

Why is Lcn2 so strongly upregulated if it is not required for fungal resistance? C. albicans infection induces a strong drive to recruit and expand neutrophils, which is mediated by other IL-17-regulated genes, such as csf3 (encoding G-CSF) and cxcl1, cxcl2, and cxcl5, encoding chemokines that recruit neutrophils and other myeloid cells to the oral mucosa. Lcn2 is expressed strongly in neutrophils as well as in epithelial cells, so its expression in the oral mucosa may simply reflect increased trafficking of neutrophils to the site of infection. C. albicans has a variety of ways to scavenge iron, including extracellular ferric reductases and a siderophore iron transporter system (CaArn1p) (40). It has been demonstrated recently that Lcn2 does not sequester the C. albicans siderophore (37). Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that the absence of Lcn2 does not impair the ability of C. albicans to survive and promote disease.

Fungal diseases are on the rise, as a result of an aging population and increasing use of immunosuppressive therapies for autoimmunity and cancer (4). Understanding the basis of antifungal immunity is critical for developing vaccines, immunomodulatory strategies, or new treatments for fungal pathogens. The lack of a role for Lcn2 in oral candidiasis underscores the complexity of the antifungal response and sheds light on the differing immune responses to different types of C. albicans-induced infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S.L.G. was supported by the NIH (DE022550 and DE023815) and Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). Y.R.C. was funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. U.S. was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIAID, NIH.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Amgen (Seattle, WA) for IL-17RA−/− mice and Genentech (South San Francisco, CA) for IL-23−/− mice. Lcn2−/− mice were generously provided by Tak Mak, University of Toronto (27).

S.L.G. discloses that she has received a research grant from, and consults for, Novartis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Fidel PL., Jr 2011. Candida-host interactions in HIV disease: implications for oropharyngeal candidiasis. Adv. Dent. Res. 23:45–49. 10.1177/0022034511399284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glocker E, Grimbacher B. 2010. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and congenital susceptibility to Candida. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 10:542–550. 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833fd74f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huppler AR, Bishu S, Gaffen SL. 2012. Mucocutaneous candidiasis: the IL-17 pathway and implications for targeted immunotherapy. Arthritis Res. Ther. 14:217. 10.1186/ar3893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. 2012. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 4:165rv13. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassone A. 2013. Development of vaccines for Candida albicans: fighting a skilled transformer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11:884–891. 10.1038/nrmicro3156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milner J, Holland S. 2013. The cup runneth over: lessons from the ever-expanding pool of primary immunodeficiency diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13:635–648. 10.1038/nri3493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, Stocum E, Sun JN, Lindemann MJ, Ho AW, Hai JH, Yu JJ, Jung JW, Filler SG, Masso-Welch P, Edgerton M, Gaffen SL. 2009. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J. Exp. Med. 206:299–311. 10.1084/jem.20081463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho AW, Shen F, Conti HR, Patel N, Childs EE, Peterson AC, Hernandez-Santos N, Kolls JK, Kane LP, Ouyang W, Gaffen SL. 2010. IL-17RC is required for immune signaling via an extended SEF/IL-17R signaling domain in the cytoplasmic tail. J. Immunol. 185:1063–1070. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farah CS, Hu Y, Riminton S, Ashman RB. 2006. Distinct roles for interleukin-12p40 and tumour necrosis factor in resistance to oral candidiasis defined by gene targeting. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 21:252–255. 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2006.00288.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puel A, Cypowji S, Bustamante J, Wright J, Liu L, Lim H, Migaud M, Israel L, Chrabieh M, Audry M, Gumbleton M, Toulon A, Bodemer C, El-Baghdadi J, Whitters M, Paradis T, Brooks J, Collins M, Wolfman N, Al-Muhsen S, Galicchio M, Abel L, Picard C, Casanova J-L. 2011. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science 332:65–68. 10.1126/science.1200439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puel A, Doffinger R, Natividad A, Chrabieh M, Barcenas-Morales G, Picard C, Cobat A, Ouachee-Chardin M, Toulon A, Bustamante J, Al-Muhsen S, Al-Owain M, Arkwright PD, Costigan C, McConnell V, Cant AJ, Abinun M, Polak M, Bougneres PF, Kumararatne D, Marodi L, Nahum A, Roifman C, Blanche S, Fischer A, Bodemer C, Abel L, Lilic D, Casanova JL. 2010. Autoantibodies against IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J. Exp. Med. 207:291–297. 10.1084/jem.20091983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kisand K, Boe Wolff AS, Podkrajsek KT, Tserel L, Link M, Kisand KV, Ersvaer E, Perheentupa J, Erichsen MM, Bratanic N, Meloni A, Cetani F, Perniola R, Ergun-Longmire B, Maclaren N, Krohn KJ, Pura M, Schalke B, Strobel P, Leite MI, Battelino T, Husebye ES, Peterson P, Willcox N, Meager A. 2010. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in APECED or thymoma patients correlates with autoimmunity to Th17-associated cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 207:299–308. 10.1084/jem.20091669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaffen SL. 2009. Structure and signalling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9:556–567. 10.1038/nri2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boisson B, Wang C, Pedergnana V, Wu L, Cypowyj S, Rybojad M, Belkadi A, Picard C, Abel L, Fieschi C, Puel A, Li X, Casanova J-L 2013. A biallelic ACT1 mutation selectively abolishes interleukin-17 responses in humans with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Immunity 39:676–686. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, Cameron G, Li L, Edson-Heredia E, Braun D, Banerjee S. 2012. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 366:1190–1199. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel DD, Lee DM, Kolbinger F, Antoni C. 2013. Effect of IL-17A blockade with secukinumab in autoimmune diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72(Suppl 2):iii116–iii123. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papp KA, Leonardi C, Menter A, Ortonne JP, Krueger JG, Kricorian G, Aras G, Li J, Russell CB, Thompson EH, Baumgartner S. 2012. Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 366:1181–1189. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miossec P, Kolls JK. 2012. Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11:763–776. 10.1038/nrd3794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford AC, Peyrin-Biroulet L. 2013. Opportunistic infections with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 108:1268–1276. 10.1038/ajg.2013.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen F, Ruddy MJ, Plamondon P, Gaffen SL. 2005. Cytokines link osteoblasts and inflammation: microarray analysis of interleukin-17- and TNF-α-induced genes in bone cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77:388–399. 10.1189/jlb.0904490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen F, Hu Z, Goswami J, Gaffen SL. 2006. Identification of common transcriptional regulatory elements in interleukin-17 target genes. J. Biol. Chem. 281:24138–24148. 10.1074/jbc.M604597200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsen JR, Borregaard N, Cowland JB. 2010. Induction of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin expression by co-stimulation with interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha is controlled by IκB-ζ but neither by C/EBP-β nor C/EBP-δ. J. Biol. Chem. 285:14088–14100. 10.1074/jbc.M109.017129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang J, Goetz D, Li JY, Wang W, Mori K, Setlik D, Du T, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Strong R, Barasch J. 2002. An iron delivery pathway mediated by a lipocalin. Mol. Cell 10:1045–1056. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00710-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goetz DH, Holmes MA, Borregaard N, Bluhm ME, Raymond KN, Strong RK. 2002. The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol. Cell 10:1033–1043. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00708-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan YR, Liu JS, Pociask DA, Zheng M, Mietzner TA, Berger T, Mak TW, Clifton MC, Strong RK, Ray P, Kolls JK. 2009. Lipocalin 2 is required for pulmonary host defense against Klebsiella infection. J. Immunol. 182:4947–4956. 10.4049/jimmunol.0803282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, Rodriguez DJ, Holmes MA, Strong RK, Akira S, Aderem A. 2004. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature 432:917–921. 10.1038/nature03104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger T, Togawa A, Duncan GS, Elia AJ, You-Ten A, Wakeham A, Fong HE, Cheung CC, Mak TW. 2006. Lipocalin 2-deficient mice exhibit increased sensitivity to Escherichia coli infection but not to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:1834–1839. 10.1073/pnas.0510847103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claudio E, Sonder SU, Saret S, Carvalho G, Ramalingam TR, Wynn TA, Chariot A, Garcia-Perganeda A, Leonardi A, Paun A, Chen A, Ren NY, Wang H, Siebenlist U. 2009. The adaptor protein CIKS/Act1 is essential for IL-25-mediated allergic airway inflammation. J. Immunol. 182:1617–1630 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/182/3/1617.long [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solis NV, Filler SG. 2012. Mouse model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Nat. Protoc. 7:637–642. 10.1038/nprot.2012.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernández-Santos N, Gaffen SL. 2012. Th17 cells in immunity to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 11:425–435. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puel A, Picard C, Cypowyj S, Lilic D, Abel L, Casanova JL. 2010. Inborn errors of mucocutaneous immunity to Candida albicans in humans: a role for IL-17 cytokines? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 22:467–474. 10.1016/j.coi.2010.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Rivino L, Geginat J, Jarrossay D, Gattorno M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, Napolitani G. 2007. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 8:639–646. 10.1038/ni1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devireddy LR, Gazin C, Zhu X, Green MR. 2005. A cell-surface receptor for lipocalin 24p3 selectively mediates apoptosis and iron uptake. Cell 123:1293–1305. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devireddy LR, Teodoro JG, Richard FA, Green MR. 2001. Induction of apoptosis by a secreted lipocalin that is transcriptionally regulated by IL-3 deprivation. Science 293:829–834. 10.1126/science.1061075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raffatellu M, George MD, Akiyama Y, Hornsby MJ, Nuccio SP, Paixao TA, Butler BP, Chu H, Santos RL, Berger T, Mak TW, Tsolis RM, Bevins CL, Solnick JV, Dandekar S, Baumler AJ. 2009. Lipocalin-2 resistance confers an advantage to Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium for growth and survival in the inflamed intestine. Cell Host Microbe 5:476–486. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu JZ, Pezeshki M, Raffatellu M. 2009. Th17 cytokines and host-pathogen interactions at the mucosa: dichotomies of help and harm. Cytokine 48:156–160. 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Z, Petersen R, Devireddy L. 2013. Impaired neutrophil function in 24p3 null mice contributes to enhanced susceptibility to bacterial infections. J. Immunol. 190:4692–4706. 10.4049/jimmunol.1202411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holmes MA, Paulsene W, Jide X, Ratledge C, Strong RK. 2005. Siderocalin (Lcn 2) also binds carboxymycobactins, potentially defending against mycobacterial infections through iron sequestration. Structure 13:29–41. 10.1016/j.str.2004.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guglani L, Gopal R, Rangel-Moreno J, Junecko BF, Lin Y, Berger T, Mak TW, Alcorn JF, Randall TD, Reinhart TA, Chan YR, Khader SA. 2012. Lipocalin 2 regulates inflammation during pulmonary mycobacterial infections. PLoS One 7:e50052. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu CJ, Bai C, Zheng XD, Wang YM, Wang Y. 2002. Characterization and functional analysis of the siderophore-iron transporter CaArn1p in Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30598–30605. 10.1074/jbc.M204545200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]