Abstract

In this study, an oral minipig infection model was established to investigate the pathogenicity of Yersinia enterocolitica bioserotype 4/O:3. O:3 strains are highly prevalent in pigs, which are usually symptomless carriers, and they represent the most common cause of human yersiniosis. To assess the pathogenic potential of the O:3 serotype, we compared the colonization properties of Y. enterocolitica O:3 with O:8, a highly mouse-virulent Y. enterocolitica serotype, in minipigs and mice. We found that O:3 is a significantly better colonizer of swine than is O:8. Coinfection studies with O:3 mutant strains demonstrated that small variations within the O:3 genome leading to higher amounts of the primary adhesion factor invasin (InvA) improved colonization and/or survival of this serotype in swine but had only a minor effect on the colonization of mice. We further demonstrated that a deletion of the invA gene abolished long-term colonization in the pigs. Our results indicate a primary role for invasin in naturally occurring Y. enterocolitica O:3 infections in pigs and reveal a higher adaptation of O:3 than O:8 strains to their natural pig reservoir host.

INTRODUCTION

The Gram-negative enteropathogenic bacterium Yersinia enterocolitica is a fecal-oral zoonotic pathogen that is associated with a number of different enteric diseases collectively called yersiniosis. Symptoms include enteritis, enterocolitis, severe diarrhea, mesenteric lymphadenitis, pseudoappendicitis, and hepatic and splenic abscesses. The diseases are normally self-limiting. However, postinfectious extraintestinal sequelae, including reactive arthritis, erythema nodosum, and thyroiditis, are also common (1–3).

Yersiniosis is a frequent bacterial enteric disease in Europe (16.5 cases per million people), with a predilection for young children (4–7). The most frequently isolated Y. enterocolitica strains that are harmful to humans and animals are classified into the bioserotypes 1B/O:8, 2/O:5,27, 2/O:9, 3/O:3, and 4/O:3 (1). Bioserotype 1B/O:8 strains (O:8) are highly virulent for mice, and most studies on Y. enterocolitica pathogenesis have been performed using this strain type, in particular, Y. enterocolitica 8081v. However, by far most human yersiniosis in Europe, Canada, China, and Japan is caused by bioserotype 4/O:3 (O:3) strains, which have a low pathogenicity in mouse models (1, 4, 8). Y. enterocolitica O:8 infections are more common in North America, but food-borne outbreaks of serotype O:3 strains have emerged in recent years and have replaced O:8 as the predominant Y. enterocolitica serotype (9–13).

Y. enterocolitica can colonize a broad range of domestic animals (e.g., sheep, cattle, goats, and poultry) and wild animals (e.g., boars and wild rodents), but the most important reservoir is pigs, which are of major importance for transmission to humans (10, 14). In particular, O:3 strains, the most frequent source of human infections, can be routinely isolated from pigs, which are usually symptomless carriers (1, 15, 16). Pigs can carry these pathogens for long time periods in the oropharynx (tonsils) and the intestinal tract without any clinical signs, leading to a prevalence of 35% to 70% in fattening pig herds (17–19). As a consequence, outbreaks of yersiniosis are mostly associated with the consumption of raw or undercooked pork or pork products (e.g., chitterlings) (18, 20, 21).

The high prevalence of O:3 strains in pigs suggests bioserotype- and/or host-specific colonization properties. However, to date little is known about the bacterial components and pathogen-host cell interactions of O:3 isolates that determine their adaption to the intestines of pigs and their pathogenicity for humans. Analysis of O:8 strains has demonstrated that this serotype initiates infections by tight binding to the intestinal mucosa, which is frequently followed by transmigration through the epithelial layer of the ileum, resulting in the colonization of the underlying lymphoid tissues (Peyer's patches). Subsequently, Y. enterocolitica can spread via the lymph and/or blood into the mesenteric lymph nodes or to extraintestinal sites, such as liver and spleen (22). Several virulence factors of O:8 strains have been identified to promote colonization of host tissues. Among them are the surface-exposed outer membrane proteins invasin (InvA) and YadA. These proteins promote efficient adhesion to and invasion into intestinal cells via direct or indirect binding of β1-integrin receptors (23–26). In O:8 strains, InvA and YadA constitute independent colonization factors that are differentially expressed and appear to act during different stages of infection. The invasin protein is predominantly synthesized at moderate temperatures (15 to 28°C), whereas only low amounts of invasin are detectable at 37°C (27). In mice, the 50% lethal dose (LD50) values for the O:8 wild-type 8081v and the isogenic invA mutant were essentially identical but colonization of the lymphoid tissues was delayed (23). This suggested that InvA might prime the bacterium to support efficient and rapid transcytosis of the intestinal epithelium during the very early stages of infection. The YadA adhesin is a multifunctional bacterial invasin that also protects bacteria from complement lysis and phagocytosis. YadA is exclusively expressed at 37°C and acts together with a type III secretion system that is responsible for the injection of antiphagocytic effector proteins (Yops) into phagocytes to modulate the host immune response during later stages of the infection (25, 26, 28).

To gain more information about the pathogenic properties of the more frequent Y. enterocolitica O:3 serotypes, we previously compared the colonization mechanisms of different human and animal O:3 isolates with that of the well-characterized Y. enterocolitica O:8 8081v strain and found that Y. enterocolitica O:3 strains have unique cell adhesion and invasion properties (29, 30). These differences are mainly attributable to significant variations of the interplay and expression profile of the same repertoire of virulence factors in response to temperature. O:3 strains, but not O:8 strains, are able to invade human cells at 37°C due to highly activated and nearly constitutive expression of invasin caused by (i) an additional promoter provided by an IS1667 element inserted in the invA promoter region and (ii) a P98S substitution in the invA transcriptional activator protein RovA that renders the regulator less susceptible to proteolysis by the Lon protease (29, 30). In addition, efficient cell attachment by expression of YadA and downregulation of O-antigen synthesis are required to allow InvA-mediated entry into cultured human epithelial cells at body temperature. Most likely, interaction of the somewhat longer YadA molecules promotes initial host cell attachment to extracellular matrix (ECM) bound to β1-integrins, which facilitates subsequent high-affinity and direct binding of the shorter invasin molecules to β1-integrin receptors. Why this distinct colonization mechanism is restricted to pig-associated O:3 strains remained unclear. In this study, we established a novel experimental oral infection model for Yersinia in minipigs, and we demonstrate that the small variations in the expression profile of pathogenicity factors in O:3 strains provoke a fine-tuned readjustment of virulence-associated processes that confers better colonization and/or survival of this serotype in swine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

All animal work was performed in strict accordance with the German regulations of the Society for Laboratory Animal Science (GV-SOLAS) and the European Health Recommendations of the Federation of Laboratory Animal Science Associations (FELASA). The protocol was approved by the Niedersaechsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit, animal licensing committee, permission no. 33.9.42502-04-055/09 (mice), 33.12-42502-04-10/0173, and 33.9-42502-04-11/0462 (pigs). All efforts were made to minimize suffering of the animals.

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

The following strains (Table 1) were used in this study: Y. enterocolitica O:8 strain 8081v (bioserotype 1B/O:8; patient isolate; wild type); O:3 strains Y1 (bioserotype 4/O:3; patient isolate; wild type); YE13 (Y1, ΔrovA ProvAO:3::rovAS98, Clmr Kanr), YE14 (Y1, ΔrovA ProvAO:3::rovAP98, Clmr Kanr), YE15 (Y1, PinvAΔIS1667), and YE21 (Y1, ΔinvA, Kanr) (23, 29). Overnight cultures of Y. enterocolitica were grown at 25°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. The antibiotics used for bacterial selection were carbenicillin at 100 μg/ml, kanamycin at 50 μg/ml, and gentamicin at 50 μg/ml. For infection experiments, bacteria were grown at 25°C, washed, and diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to infections.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

Mouse infections.

Bacteria used for oral infections were grown overnight in LB medium at 25°C, washed, and resuspended in PBS. Six- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from Janvier (St. Beverthin, France). Two independent groups of 5 mice were orally infected with Y. enterocolitica strains in single-infection and coinfection experiments by using a ball-tipped feeding needle. For single-infection experiments, 5 × 108 bacteria of the Y. enterocolitica strains 8081v and Y1 were administered orogastrically. In coinfection experiments, mice were infected with a mixture of equal numbers of 5 × 108 bacteria of Y. enterocolitica strains Y1 and YE14, Y1 and YE21, or YE13 and YE15.

Three days after infection, mice were euthanized by CO2. Jejunum, ileum, Peyer's patches, cecum, colon, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, and spleen were isolated. The isolated tissues were rinsed with sterile PBS and incubated with 50 μg/ml gentamicin in order to kill bacteria on the luminal surface. After 30 min, gentamicin was removed by extensive washing with PBS three times. Subsequently, all organs were weighed and homogenized in sterile PBS at 30,000 rpm for 30 s by using a Polytron PT 2100 homogenizer (Kinematica, Switzerland). Bacterial numbers were determined by plating independent serial dilutions of the homogenates on LB plates with and without antibiotics. The CFU were counted and are reported as CFU/g of organ or tissue. The competitive index relative to result with the wild-type strain Y1 was calculated as described previously (31).

Minipig infections.

Bacteria used for oral infections were grown overnight in LB medium at 25°C, washed, and resuspended in PBS. Five- to 7-week-old Mini-Lewe minipigs were purchased from the Forschungsgut Ruthe of the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover. Minipigs were separated into independent groups and sampled by tonsil and rectal swabs 7 days prior to infection. The analyses of tonsil and rectal swabs confirmed that the minipigs were free of Y. enterocolitica prior to infection. For single infections, approximately 109 bacteria of Y. enterocolitica strain 8081v or Y1 were used for oral infection. In coinfection experiments, minipigs were orally infected with an equal mixture of 109 bacteria of Y. enterocolitica strains Y1 and YE14, Y1 and YE21, or YE13 and YE15.

Postinfection blood samples were taken once and rectal swabs were obtained twice a week. At the indicated times postinfection, minipigs were narcotized by azaperon (Stresnil) and ketamine (Ursotamin) before final blood sampling and then euthanized with pentobarbital (Release). Tonsils, jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, kidneys, and spleen were isolated. The tissues were rinsed with sterile PBS and incubated with 50 μg/ml gentamicin in order to kill bacteria on the luminal surface. After 30 min, gentamicin was removed by extensive washing with PBS three times. Subsequently, all organs were weighed and homogenized in sterile PBS at 30,000 rpm for 30 s by using a Polytron PT 2100 homogenizer (Kinematica, Switzerland). Bacterial numbers were determined by plating two independent serial dilutions of the homogenates on cefsulodin-irgasan-novobiocin (CIN) agar plates with and without antibiotics. The CFU were counted and are reported as CFU/g of organ or tissue. The competitive index relative to results with the wild-type strain Y1 was calculated as described previously (31).

Qualitative detection of bacteria in tissues and rectal swabs of the minipigs via cold enrichment.

Rectal and tonsil swabs were stored in 10 ml PBS at 4°C, streaked on CIN agar plates at days 7, 14, and 21, and incubated at 30°C for up to 48 h. Organ samples were homogenized in sterile PBS as described above, and 200 μl of the homogenate was added to 10 ml sterile PBS. This solution was stored at 4°C, streaked on CIN agar plates after 7, 14, and 21 days, and then incubated at 30°C for up to 48 h.

Detection of specific antibodies in pig sera.

Blood samples were taken weekly before and after oral infection of piglets by puncture of the cranial vena cava. Serum was extracted using serum Monovettes (Sarstedt, Germany). Serological examinations were performed using a commercial microtiter plate-based enzyme immunoassay (PigType YopScreen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] system; Labor Diagnostik Leipzig, Germany), based on recombinant Yersinia Yops. These antigens are expressed only by pathogenic Yersinia strains. The optical density (OD) was measured in a spectrophotometer, and an OD value of 20% was used as the cutoff value.

Histological analysis.

Samples of the euthanized minipigs (ileum and mesenteric lymph nodes [MLNs]) were collected and fixed in 10% nonbuffered formalin. Following a fixation period of 24 h, samples were embedded according to standard procedures. The tissue processing was performed automatically (Shandon Path Centre tissue processor; Thermo). One slide of each paraffin block was cut at 1.5- to 3-μm thickness by a microtome and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The degree of inflammation in the lamina propria of the ileum was assessed semiquantitatively by using the following scoring system: 0, no inflammation; 0.5, minimal inflammation; 1, very mild inflammation; 1.5, mild inflammation; 2, moderate inflammation; 2.5, moderate to severe inflammation; 3, severe inflammation. The statistical analysis of the data was performed by using the statistics program SPSS (Superior Performing Systems, version 20.0). A group-wise comparison with the Mann-Whitney U test was performed to determine the semiquantitative parameters for general inflammation and infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Establishment of minipig infection model for Y. enterocolitica.

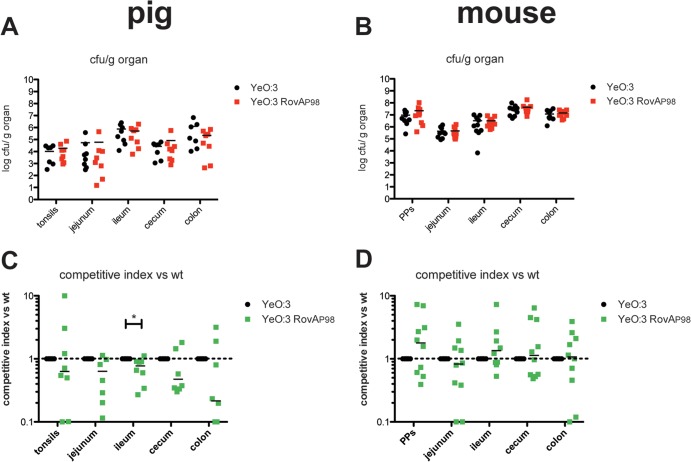

To investigate interactions of different Y. enterocolitica wild-type and mutant strains with their natural and most important animal reservoir, we established an oral infection model in miniature pigs (minipigs). Minipigs were chosen due to their advantages of their handling and housing and their increasing popularity as laboratory animals, as they develop human-sized organs between 6 and 8 months of age (32). First, minipigs were challenged with oral doses of 108, 109, and 1010 CFU of the O:3 wild-type strain Y1, a recent patient isolate that showed host cell interaction properties identical to other characterized human and porcine isolates (29, 30). All pigs appeared healthy and did not show any clinical signs of infection, i.e., increased temperature, diarrhea, or loss of appetite. The efficiency of the infection was monitored by reisolation of bacteria from tonsils, different gut sections (jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon), MLNs, and organs (liver, spleen, and kidney) 7 days postinfection. Treatment of the infected sections allowed in particular isolation of bacteria that had been internalized into the tissue. As shown in Fig. 1A , a comparable amount of bacteria was isolated from tonsils and the gut sections in all three different groups. We were able to detect yersiniae in the MLNs, liver, and kidney almost exclusively only in those animals that had been infected with the highest dose of bacteria (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

Establishment of the Y. enterocolitica minipig model. (A) Influence of the infectious dose on Y. enterocolitica O:3 colonization in minipigs. Mini-Lewe piglets were orally infected with O:3 strain Y1 (wt). The infection inoculum contained 108, 109, or 1010 CFU. The animals were sacrificed at day 7 postinfection, and the numbers of surviving bacteria in tonsils, jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and kidney were determined. (B) Seroconversion induced by Y. enterocolitica O:3. Mini-Lewe piglets were orally infected with 109 CFU of Y. enterocolitica serotype O:3 strain Y1 or mock infected with PBS. Sera were analyzed using an ELISA system based on recombinant Yops. Data are presented as the percentage of the mean OD relative to the control.

In agreement with these results, all infected animals shed bacteria in the feces at day 7 postinfection. In further experiments, we analyzed the time course of infection by using an oral dose of 109 CFU per piglet, in order to generate an infection with a low risk of provoking clinically apparent disease. Results showed that the bacteria were shed in feces from day 1 up to day 21 postinfection. Via cold enrichment, yersiniae could be reisolated from the different intestinal and extraintestinal organs from day 3 up to day 14 postinfection. Reisolation of the bacteria was still possible from the intestinal sections of all infected animals at day 21 postinfection. However, the organ burden was lower than on days 3 and 7. No severe pathological lesions were observed in any of the infected animals (see Fig. S1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). In addition, blood samples from piglets were taken weekly before and after oral infection with 109 CFU of the serotype O:3 strain Y1. Sera were tested for antibodies against Yops. Infected pigs showed clear seroconversion between day 7 and day 14 postinfection, whereas antibody titers of the control animals remained negative (Fig. 1B). Minimal to moderate inflammation of the lamina propria and submucosa of the small and large intestine is frequently observed in uninfected minipigs (33). In summary, we demonstrated that O:3 colonizes and persists in the lymphatic tissues of the tonsils and in the intestinal tracts of the minipigs, causing infections without severe inflammation and pathological changes, which is in accordance with natural infection in productive livestock.

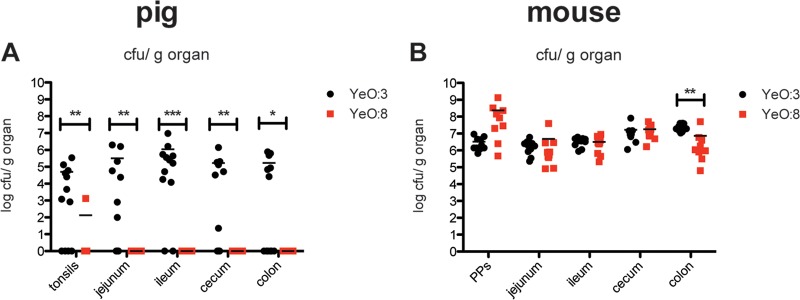

Y. enterocolitica O:3 colonization of minipigs differs significantly from that by O:8.

The newly established oral minipig model and the well-established BALB/c mouse model were used to assess and compare colonization and pathogenic properties of O:3 strain Y1 and O:8 strain 8081v. Colonization of the tonsils and different sections of the intestinal tract (jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon) was monitored by scoring the bacterial loads in the different tissue specimens. The O:8 strain could only be isolated from the tonsils of a single infected minipig, but it was not detectable in any of the intestinal sections at day 7 postinfection. In strong contrast, high numbers of O:3 bacteria (103 to 106 CFU/g of organ) were reisolated from all tested intestinal sections of all infected minipigs that remained symptomless, as in our previous experiments (Fig. 2A). Histological examinations revealed detection of bacterial colonies in intestinal wall sections only of O:3-infected, and not of O:8-infected piglets (see Fig. S1). Overall, no or only very mild signs of inflammation and symptoms of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) hyperplasia, like increased lymphoid tissue in the jejunum and colon wall, were observed, and occasionally very mild epithelial necrosis was evident, sometimes with atrophy/shortening of the villi. However, these findings were frequently also seen in uninfected control pigs (see Fig. S1A and Table S1) (33).

FIG 2.

Y. enterocolitica O:3 and O:8 infections of minipigs (A) and mice (B). (A) Mini-Lewe piglets were orally infected with 109 O:3 strain Y1 (wt) or O:8 strain 8081v (wt). Accordingly, BALB/c mice were infected orally with 5 × 108 of the described bacterial strains. Mice were sacrificed at day 3 and minipigs at day 7 postinfection. Numbers of surviving bacteria in the tonsils of the minipigs, in the Peyer′s patches of the mice, and in jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon of mice and minipigs were determined. Data are presented as scatter plots of numbers of CFU per gram of organ, determined by counts of viable bacteria after serial plating. Each spot represents the CFU count in the indicated tissue. The levels of statistical significance for differences between test groups were determined by using the Mann-Whitney test. Results that differed significantly from those of Y1 are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

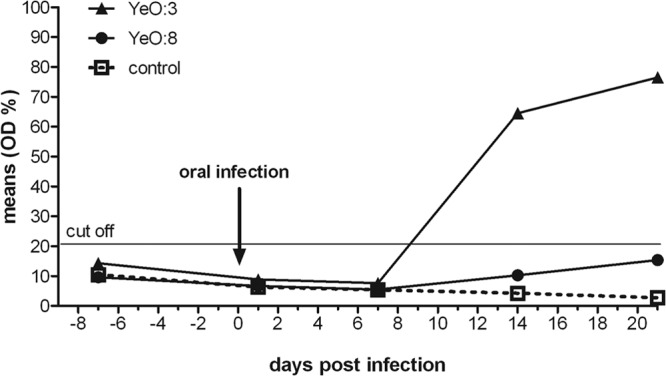

Detection by cold enrichment further demonstrated that the serotype O:3 strain could be reisolated from extraintestinal organs, such as the MLNs, spleen, and kidney of the minipigs 7 days postinfection, whereas O:8 was only found in the tonsils and ileum of 30% of the infected minipigs (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Blood samples obtained weekly were tested for the presence of anti-Yop antibodies, and they showed seroconversion in pigs infected with O:3 between days 7 and 14 postinfection, whereas titers of the O:8-infected piglets and control animals remained negative (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Comparison of seroconversion induced by Y. enterocolitica O:3 and O:8 in minipigs. Mini-Lewe piglets were orally infected with 109 CFU of Y. enterocolitica serotype O:3 strain Y1, Y. enterocolitica serotype O:8 strain 8081v, or mock infected with PBS. Sera were analyzed using an ELISA system based on recombinant Yops. Data are presented as the percentage of the mean OD relative to the control.

Strikingly, this difference in the colonization pattern was not observed in the BALB/c infection model. Comparable amounts of O:3 and O:8 cells were isolated from all tested intestinal tissues of the mice, and an even higher number of O:8 cells was detectable in the mouse Peyer's patches, compared to O:3 cells (Fig. 2B). Mice infected with O:8 showed severe signs of illness (weight loss, diarrhea, piloerection, and lethargy). In contrast, mice infected with O:3 remained clinically healthy.

To further investigate how long the different wild-type yersiniae were shed by the pigs via feces, rectal swabs were taken and cultivated using cold enrichment. The results showed that 40% of the minipigs infected with O:3 shed bacteria with their feces from day 1 and 100% shed bacteria from day 7 up to day 21 postinfection. In contrast, only 25% of the Y. enterocolitica serotype O:8-infected animals shed the bacteria at day 1, and no yersiniae were reisolated from feces of the O:8-infected group of pigs from day 10 to 21 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Taken together, these findings strongly indicate that, in contrast to O:8, O:3 is able to efficiently colonize and persist in the tonsils and the intestinal tracts of the pigs for much longer time periods.

Enhanced RovA levels are advantageous for the colonization of the porcine ileum by Y. enterocolitica O:3 in pigs.

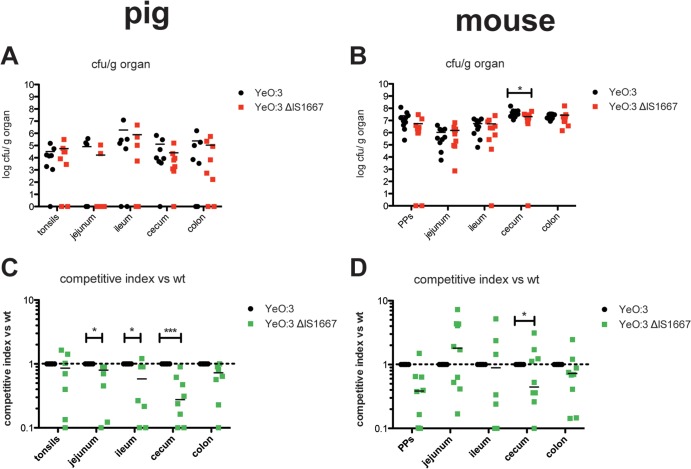

Our previous study highlighted important differences in the adhesion properties of O:3 strains from other Y. enterocolitica serotypes. One difference concerns the global virulence regulator RovA, which is known to regulate the expression of several Yersinia virulence factors, including the primary internalization factor invasin (29, 34–36). It was found that a thermal upshift rendered the RovA regulatory protein more susceptible to degradation in O:8 strains. In contrast, a single proline-to-serine substitution at position 98 (P98S) present in the majority of all characterized O:3 strains, including Y1, increased the stability of RovA without affecting the thermosensing ability of the regulator (29). As a consequence, considerably higher amounts of RovA were synthesized by the bacteria, and this could have compensated for the thermo-induced reduction of RovA DNA binding at elevated temperatures. Since O:3 is a much better colonizer of intestinal tissues of swine than is O:8, we tested whether a more temperature-stable RovA variant would be advantageous for persistence of the bacteria in pigs with an overall slightly higher body temperature (38°C to 40°C) compared to that of mice or humans (37°C), and we compared this with the effect of the more stable RovA on virulence in mice. We performed coinfection experiments to minimize inherent interanimal biological variations, thereby revealing even subtle differences of the colonization and persistence patterns. Mice and minipigs were infected with approximately 5 × 108 or 109 bacteria, respectively. Each inoculum comprised a mixture of equal numbers of the parental kanamycin (Kans) O:3 wild-type strain Y1 [rovAYeO:3(S98)] and the Kanr mutant strain YE14 [RovAYeO:3(P98)]. The latter expresses the RovAYeO:3(P98) mutant protein, which is rapidly degraded, similar to the RovAYeO:8(P98) variant. At day 7 postinfection, gut tissue colonization by the bacterium was monitored by scoring the bacterial load in the different intestinal parts (jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon) of mice and pigs, in the Peyer's patches (PPs) in mice, and in the tonsils of pigs. In both mice and pigs, the bacteria were able to invade into all examined organs (Fig. 4). Comparison of the calculated competitive indices revealed that, in general, slightly higher numbers of bacterial O:3 strain Y1 expressing the stable version of RovA [RovAYeO:3(S98)] than of strain YE14 were isolated from the infected tissues of the pigs (Fig. 4A). In contrast, identical or even more bacteria of the O:3 strain YE14 expressing the less-stable version of RovA [RovAYeO:3(P98)] were isolated from the infected mouse tissues (Fig. 4B to D). However, these results were only statistically significant for the infected ileum of the pigs, indicating that a stable RovA variant might cause a small, but not a major, competitive advantage for colonization of pigs.

FIG 4.

Influence of constitutive RovA expression on Y. enterocolitica O:3 infection. Mini-Lewe minipigs were infected orally with 109 bacteria (A and C), and BALB/c mice were coinfected via the orogastric route with 5 × 108 bacteria (B and D). The infection inoculum contained an equal mixture of the O:3 strains Y1 (wt; rovAS98) and YE14 (rovAP98). Mice were sacrificed on day 3 and minipigs on day 7 postinfection. Numbers of surviving bacteria in the tonsils of the minipigs, in Peyer′s patches of the mice, and in jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon of mice and minipigs were determined. (A and B) Data are presented as scatter plots of numbers of CFU per gram of organ, determined by counts of viable bacteria on plates. Each spot represents the CFU count in the indicated tissue. The levels of statistical significance for differences between test groups were determined by using the Mann-Whitney test. (C and D) Competitive index values for differences in virulence compared to Y1. Results that differed significantly from those of Y1 are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05.

Presence of IS1667 inserted into the invA promoter region of O:3 strains increases colonization of the intestinal tract of pigs.

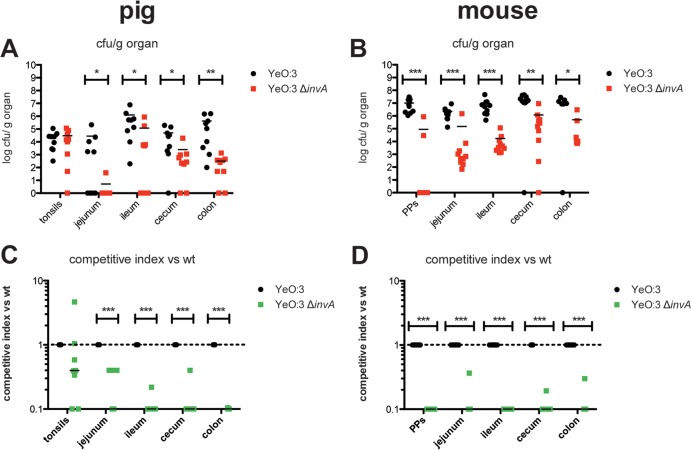

Another difference between O:3 and O:8 is that in O:3 the primary internalization factor, invasin, is highly and (nearly) constitutively synthesized, whereas it is strongly repressed at 37°C in O:8 (30). Constitutive expression of invasin in O:3 was acquired via IS1667 insertion into the rovA regulatory region harboring an IS-specific promoter. Its presence allowed invA expression at 37°C, even in the absence of RovA (30). To test whether constitutive invA expression would be beneficial for O:3, we performed coinfection experiments with the Kanr derivative of the O:3 wild-type strain (YE13) and the Kans mutant derivative, YE15 (PinvO:3ΔIS), in which the IS1667 element was deleted from the invA promoter region. The presence of IS1667 did not seem to have an impact on the colonization and persistence of O:3 in the intestinal tract of mice (Fig. 5B and D). In contrast, significantly lower numbers of the ΔIS1667 mutant were reisolated from different tissue sections of the intestinal tract (Fig. 5A and C). In particular. the calculated competitive index illustrated very clearly that O:3 IS1667 deletion mutants had a substantial disadvantage in invading the different tissues of the porcine intestinal tract, although the absence of the IS1667 element had no influence on the colonization of the tonsils (Fig. 5C) and did not lead to a reduction of fecal shedding during the first week after infection (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material).

FIG 5.

Impact of the insertion element IS1667 in the invA promoter region on Y. enterocolitica O:3 virulence. Coinfections with equal mixtures of YE13 (Y1 Kanr) and YE15 (Y1 ΔIS1667) were performed in Mini-Lewe minipigs and BALB/c mice. Mice were infected orogastrically with a total of 5 × 108 bacteria, and pigs were infected orally with 109 bacteria. Mice were sacrificed at 3 days and minipigs at 7 days postinfection. Numbers of surviving bacteria in the tonsils of the minipigs, in Peyer's patches of the mice, and in jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon of mice and minipigs were determined. (A and B) Data are presented as scatter plots of numbers of CFU per gram of organ, determined by counts of viable bacteria on plates. Each spot represents the CFU count in the indicated tissue. The levels of statistical significance for differences between test groups were determined by using the Mann-Whitney test. (C and D) Competitive index values for differences in virulence compared to Y13. Results that differed significantly from those of Y1 are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

Invasin is important for persistence of Y. enterocolitica O:3 in the intestinal tract of pigs and mice.

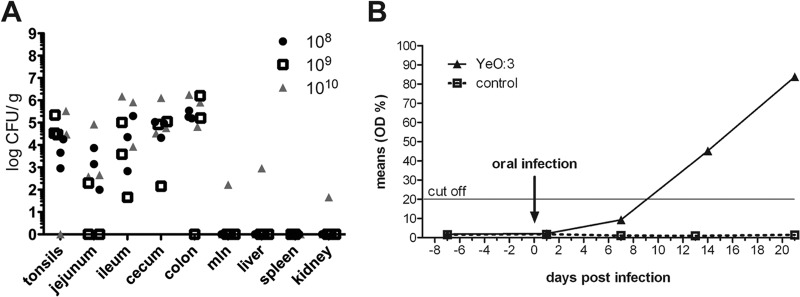

Since constitutive invA expression was found to be beneficial for bacterial colonization of the different tissues of the porcine intestinal tract, we also investigated whether invasin per se is an essential virulence factor for efficient colonization and persistence of O:3 within the tissues of the porcine intestinal tract. Equivalent to previous studies in this work, coinfection experiments were performed in minipigs and mice with an equal mixture of the Kans O:3 wild-type Y1 strain and the Kanr mutant derivative YE21 (ΔinvA). Tissue colonization of the intestinal tract by the invA mutant strain was drastically reduced in pigs and mice compared to the wild type (Fig. 6). About 101- to 104-fold less bacteria were recovered from the different tissue sections of the intestinal tract of pigs and mice and the Peyer's patches of mice. Calculation of the competitive indices further demonstrated that the decrease in the efficiency to persist in the intestinal tract was significant (Fig. 6), indicating that invasin is a very important colonization factor for Y. enterocolitica O:3. These findings were also confirmed by the analysis of bacterial shedding, demonstrating that only 30% and 50% of the minipigs shed the invA mutant bacteria at day 3 and 7 postinfection compared to 70% and 90% of the minipigs infected with the wild type, respectively (see Fig. S4B). In contrast, no significant difference of the bacterial load was observed in the tonsils of the pigs. This suggests that other adhesion factors of the pathogen are implicated in the colonization of the lymphatic tissue of the porcine throat. Y. enterocolitica O:3 strains encode additional adhesins (Ail, YadA, and PsaA) and other noncharacterized putative adhesion factors (e.g., another InvA-type protein) (37) that could contribute to this process.

FIG 6.

Invasin is important for persistence of Y. enterocolitica O:3 in the intestinal tracts of pigs and mice. BALB/c mice and Mini-Lewe minipigs were coinfected via the oral route with equal mixtures of Y1 (wt) and YE21 (Y1 ΔinvA). The total inoculum doses were 5 × 108 bacteria for mice and 109 bacteria for pigs. Mice were sacrificed at 3 days and minipigs at 7 days postinfection. Numbers of surviving bacteria in the tonsils of the minipigs, in Peyer's patches of the mice, and in jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon of mice and minipigs were determined. (A and B) Data are presented as scatter plots of the numbers of CFU per gram of organ, determined by counts of viable bacteria on plates. Each spot represents the CFU count in the indicated tissue. The levels of statistical significance for differences between test groups were determined by using the Mann-Whitney test. (C and D) Competitive index values for differences in virulence compared to Y1. Results that differed significantly from those of Y1 are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Y. enterocolitica causes enteric infections in a wide range of domestic and wild animals like dogs, goats, sheep, boars and pigs (21). In many countries, pigs are the predominant reservoir of bioserotype 4/O:3, the most frequent cause of human infections. Since O:3-infected pigs are usually asymptomatic carriers and as such represent a substantial disease-causing potential for humans, we developed an oral minipig model to characterize tissue colonization of Y. enterocolitica serotype O:3. As a high prevalence of O:3 strains in fattening pigs indicates serotype- and host-specific colonization strategies, we compared the persistence of a O:3 patient isolate with the best-characterized and highly mouse-virulent O:8 8081v strain in minipigs and mice.

This study, employing a novel minipig model for enteric Yersinia infections, clearly demonstrates that the porcine model is very suitable for the analysis of bacterial colonization and persistence of the bacterium in its natural reservoir. We found that O:3, but not O:8, was able to successfully colonize and persist in the different sections of the intestinal tract of the minipigs. The course of the O:3 infection was symptomless, although invasion of intestinal tissue sections and shedding of bacteria were observed during the first 3 weeks after oral challenge. In contrast, only the tonsils were efficiently colonized by O:8 in some of the infected minipigs. These results are in agreement with previous observations in surveys that reported that mainly serotype O:3 strains were isolated from the oral cavity, intestinal tract, and feces of pigs (21, 38, 39). Young pigs generally get infected within the first 3 weeks after entering contaminated areas (e.g., pens) or by other infected pigs, and they remain intestinal and pharyngeal carriers for long time periods (38). Experimental infections of 10- and 24-week-old pigs of larger breeds with Y. enterocolitica serotype O:3 confirmed this observation and showed that, similar to the infected minipigs in this study, large numbers of the bacteria were still shed 2 to 3 weeks after infection (40). In addition, in our study the minipigs had seroconverted at day 14, which corresponds to what has been described for experimentally infected large breeds (41).

Pigs, but also wild rodents and other wild animals, have been shown to be reservoirs for Y. enterocolitica O:8. Indistinguishable genotypes have been found among strains isolated from humans and wild rodents, and small rodents are considered responsible for human infections and outbreaks in monkeys in Japan (42, 43). In one single study, employing an experimental oral pig model, a conventional large breed was used to assess the pathogenic potential of a restriction-deficient (R− M+) derivative of strain O:8 8081v. Similar to the minipig model in this study, the 8081v derivative persisted mainly in the lymphoid tissues of the tonsils, and no bacteria were detected in the small intestine on day 7 postinfection (19). Challenge with a 500-fold-higher dose of bacteria also caused asymptomatic infections without major pathological signs in larger-breed pigs, and only a very slight enteric catarrhalic inflammation was detectable early during infection (19). However, several histological changes were observed in the brain (meningoencephalitits), lung (pneumonia catarrhalia), liver (lymphohistiocytic nodules), and several other tissues (hyperplasia of lymph follicles in the small intestine and the mesenteric lymph nodes) between days 14 and 45 postinfection (19).

Until now, it remained unclear which of the different virulence factors and regulators of Y. entercolitica O:3 are required for efficient colonization and persistence in pigs. Here, we have demonstrated that the internalization factor invasin (InvA) is crucial for the establishment of an intestinal infection in the minipigs. Invasin was shown to promote efficient colonization of all tested gut tissue sections (jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon). A O:3 invA mutant strain was still able to colonize the tonsils of the minipigs, but its ability to persist in the intestinal tract was strongly reduced. Interestingly, similar to the oral minipig model, also colonization of the different intestinal tissues and the Peyer's patches was reduced by up to 1,000-fold in the oral mouse model, suggesting that invasin plays a primary role in the initiation of the colonization of the intestinal tissue by O:3. Invasin is well-known to be necessary for rapid and efficient penetration of the intestinal barrier by Y. entercolitica in mice. However, a defect in the ability of O:8 invA mutants to colonize Peyer's patches has only been reported for the very early infection stages (23, 44). During the subsequent establishment of a systemic infection, invasin of O:8 seems of secondary importance, since the invA mutant started to colonize the Peyer's patches after a delay of 3 to 4 days and was able to reach the liver and spleen within essentially the same time frame and efficiency (23) as the respective wild-type strain. The observation that invA expression in O:8 is downregulated upon a temperature shift from 25°C to 37°C (27) supports this assumption and indicates that alternative entry pathways predominantly expressed at body temperature during later stages of the infection promote dissemination to deeper tissues and establishment of a systemic infection. Based on the results of this study, invasin seems to be more important for the initiation and establishment of a successful O:3 infection than previously observed for O:8.

In our preceding study, we demonstrated that O:3 constitutively expresses high levels of InvA, which is acquired through an IS1677 insertion in the invA regulatory region, and a more temperature-stable variant of the transcriptional activator of invA, RovA. In this study, we demonstrated that elevated InvA levels caused by these O:3-specific variations enhanced colonization of the intestinal tissues by O:3 in the pigs but not in mice. This strongly suggests that these differences between O:3 and O:8 strains confer better survival and/or persistence of O:3 in pigs. Whether this is (partially) due to a higher body temperature of pigs (38°C to 40°C) remains speculative.

The comparison of the colonization of pigs by O:3, O:3 ΔinvA, and O:8 also indicates that expression of invasin alone does not account for the huge difference between the O:3 and O:8 strains. Other virulence-associated traits identified in bioserotype 4/O:3 strains that are absent in 1B/O:8 isolates (37) are likely to provide a serious advantage for colonization of pigs. For example, Y. enterocolitica O:3 strain Y11 carries an alternative pattern of putative virulence determinants, i.e., an RtxA-like toxin, beta-fimbriae, a novel type III secretion system, a bacteriocin cluster, a four-gene cluster homologous to the aatPABCD operon of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli that plays a role in virulence by extransporting dispersin, and the agaVWEF operon, which supports the utilization of N-acetyl-galactosamine (GalNAc) (37). This sugar represents the majority of sugars in the mucin of the pig small intestine and can be used by O:3 strain Y11 as the single carbon source but not by the O:8/1B strain (37, 45). The ability to utilize GalNAc of the pig gut mucin might represent a crucial fitness factor of Y. enterocolitica O:3 that supports adaptation to its natural host, the pig (37).

Among the set of virulence traits for which an alteration between O:3 and O:8 strains was demonstrated, we showed that invasin upregulation plays a significant role in host colonization and successful persistence. It is well known that invasin promotes direct binding to β1-integrin receptors expressed on M cells in the intestinal epithelium in mice and induces uptake and transcytosis to reach subepithelial layers (24, 46). An overall alignment of the murine and porcine β1-integrin amino acid sequence indicated that both receptors are highly homologous (93.5% amino acid identity), indicating that an identical receptor family is used by the bacterium for colonization in swine. Not much is known about expression of β1-integrin receptors in porcine tissues. However, some evidence has shown that β1-integrins are expressed in the porcine intestine and in isolated intestinal epithelial cells of swine (47, 48). Efficient invasin-mediated engagement of β1-integrin receptors in the intestine could inhibit spread to other host sites and enable the pathogen to remain in the intestine of the pigs for extended time periods. Adhesion would also allow prolonged bacterial multiplication within the intestine, and this would exceed the rate of excretion from the lumen of the gut (49). Low expression of invasin in the O:8 strains at 37°C is disadvantageous for the adhesion process and would explain the low efficiency of O:8 to persist in the porcine intestinal tract. Besides, Y. enterocolitica has genes for several other adhesins, such as YadA and Ail (50). Alternative adhesion and invasion strategies have been shown to compensate for lack of InvA-mediated cell adhesion by O:8 in the mouse infection model, and this could account for the observation that LD50 values of both strains were very similar and that lack of invasin caused only subtle differences for systemic infection in mice (23, 44). Interestingly, although the alternative adhesins YadA and Ail of O:8 strains promote bacterial attachment to human epithelial cells independently of invasin (25, 51), none of them seems to be able to promote long-term persistence of O:8 in the intestinal tract of pigs. Since loss of invasin alone is sufficient to abolish efficient colonization of the porcine intestinal tract by O:3, neither YadA nor Ail seems to be able to fully complement this defect. This strongly suggests that, in particular, inactivation of invasin function might be sufficient to prevent O:3 colonization. This knowledge might help in the development of future strategies to reduce the high prevalence of O:3 strains in fattening pigs/pig herds and, thereby, to lower the risk of transmission of Y. enterocolitica to humans from pigs and pork products.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Martin Fenner for helpful discussions. We also thank Tatjana Stolz and Sandra Stengel for help with the animal infection experiments.

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry for Research and Education (BMBF; Consortium FBI-Zoo), the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, and the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF). Julia Schaake was also supported by the President's Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres (HGF) under contract number VH-GS-202. Anna Drees was funded by a fellowship of the Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony (Georg-Christoph-Lichtenberg Scholarship) within the framework of the Ph.D. program EWI-Zoonosen of the Hannover Graduate School for Veterinary Pathobiology, Neuroinfectiology, and Translational Medicine (HGNI).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 December 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01001-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bottone EJ. 1999. Yersinia enterocolitica: overview and epidemiologic correlates. Microbes Infect. 1:323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koornhof HJ, Smego RA, Jr, Nicol M. 1999. Yersiniosis. II. The pathogenesis of Yersinia infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:87–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smego RA, Frean J, Koornhof HJ. 1999. Yersiniosis. I. Microbiological and clinicoepidemiological aspects of plague and non-plague Yersinia infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosner BM, Stark K, Werber D. 2010. Epidemiology of reported Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Germany, 2001–2008. BMC Public Health 10:337. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koehler KM, Lasky T, Fein SB, Delong SM, Hawkins MA, Rabatsky-Ehr T, Ray SM, Shiferaw B, Swanson E, Vugia DJ. 2006. Population-based incidence of infection with selected bacterial enteric pathogens in children younger than five years of age, 1996–1998. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25:129–134. 10.1097/01.inf.0000199289.62733.d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.EFSA 2011. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses and zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2009. EFSA J. 9:2090 http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/2090.htm [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long C, Jones TF, Vugia DJ, Scheftel J, Strockbine N, Ryan P, Shiferaw B, Tauxe RV, Gould LH. 2010. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica infections, FoodNet, 1996–2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:566–567. 10.3201/eid1603.091106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Cui Z, Jin D, Tang L, Xia S, Wang H, Xiao Y, Qiu H, Hao Q, Kan B, Xu J, Jing H. 2009. Distribution of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in China. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:1237–1244. 10.1007/s10096-009-0773-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tauxe RV. 2002. Emerging foodborne pathogens. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 78:31–41. 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00232-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones TF. 2003. From pig to pacifier: chitterling-associated yersiniosis outbreak among black infants. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1007–1009. 10.3201/eid0908.030103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee LA, Gerber AR, Lonsway DR, Smith JD, Carter GP, Puhr ND, Parrish CM, Sikes RK, Finton RJ, Tauxe RV. 1990. Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 infections in infants and children, associated with the household preparation of chitterlings. N. Engl. J. Med. 322:984–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control 2009, posting date Annual epidemiological report on communicable diseases 2009. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm, Sweden [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bissett ML, Powers C, Abbott SL, Janda JM. 1990. Epidemiologic investigations of Yersinia enterocolitica and related species: sources, frequency, and serogroup distribution. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:910–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nesbakken T, Iversen T, Lium B. 2007. Pig herds free from human pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:1860–1864. 10.3201/eid1312.070531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M. 2012. Isolation of enteropathogenic Yersinia from non-human sources. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 954:97–105. 10.1007/978-1-4614-3561-7_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNally A, Cheasty T, Fearnley C, Dalziel RW, Paiba GA, Manning G, Newell DG. 2004. Comparison of the biotypes of Yersinia enterocolitica isolated from pigs, cattle and sheep at slaughter and from humans with yersiniosis in Great Britain during 1999–2000. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 39:103–108. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01548.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhaduri S, Wesley IV, Bush EJ. 2005. Prevalence of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains in pigs in the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7117–7121. 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7117-7121.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tauxe RV, Vandepitte J, Wauters G, Martin SM, Goossens V, De Mol Van Noyen PR, Thiers G. 1987. Yersinia enterocolitica infections and pork: the missing link. Lancet i:1129–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najdenski H, Golkocheva E, Kussovski V, Ivanova E, Manov V, Iliev M, Vesselinova A, Bengoechea JA, Skurnik M. 2006. Experimental pig yersiniosis to assess attenuation of Yersinia enterocolitica O:8 mutant strains. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 47:425–435. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Boer E, Nouws JF. 1991. Slaughter pigs and pork as a source of human pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 12:375–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Stolle A, Korkeala H. 2006. Molecular epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica infections. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 47:315–329. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dube P. 2009. Interaction of Yersinia with the gut: mechanisms of pathogenesis and immune evasion. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 337:61–91. 10.1007/978-3-642-01846-6_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pepe JC, Miller VL. 1993. Yersinia enterocolitica invasin: a primary role in the initiation of infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:6473–6477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isberg RR, Leong JM. 1990. Multiple beta 1 chain integrins are receptors for invasin, a protein that promotes bacterial penetration into mammalian cells. Cell 60:861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Tahir Y, Skurnik M. 2001. YadA, the multifaceted Yersinia adhesin. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:209–218 http://dx.doi.org/10.1078/1438-4221-00119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirjavainen V, Jarva H, Biedzka-Sarek M, Blom AM, Skurnik M, Meri S. 2008. Yersinia enterocolitica serum resistance proteins YadA and Ail bind the complement regulator C4b-binding protein. PLoS Pathog. 4(8):e1000140. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pepe JC, Badger JL, Miller VL. 1994. Growth phase and low pH affect the thermal regulation of the Yersinia enterocolitica inv gene. Mol. Microbiol. 11:123–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cornelis GR, Boland A, Boyd AP, Geuijen C, Iriarte M, Neyt C, Sory MP, Stainier I. 1998. The virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1315–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uliczka F, Pisano F, Schaake J, Stolz T, Rohde M, Fruth A, Strauch E, Skurnik M, Batzilla J, Rakin A, Heesemann J, Dersch P. 2011. Unique cell adhesion and invasion properties of Yersinia enterocolitica O:3, the most frequent cause of human Yersiniosis. PLoS Pathog. 7(7):e1002117. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uliczka F, Dersch P. 2012. Unique virulence properties of Yersinia enterocolitica O:3. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 954:281–287. 10.1007/978-1-4614-3561-7_35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monk IR, Casey PG, Cronin M, Gahan CG, Hill C. 2008. Development of multiple strain competitive index assays for Listeria monocytogenes using pIMC; a new site-specific integrative vector. BMC Microbiol. 8:96. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meurens F, Summerfield A, Nauwynck H, Saif L, Gerdts V. 2012. The pig: a model for human infectious diseases. Trends Microbiol. 20:50–57. 10.1016/j.tim.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McInnes EF. 2012. Minipigs, p 81–86 In McInnes EF. (ed), Background lesions in laboratory animals: a color atlas. Saunders Elsevier, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cathelyn JS, Ellison DW, Hinchliffe SJ, Wren BW, Miller VL. 2007. The RovA regulons of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pestis are distinct: evidence that many RovA-regulated genes were acquired more recently than the core genome. Mol. Microbiol. 66:189–205. 10.1111/j.1365-2958-2007.05907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagel G, Lahrz A, Dersch P. 2001. Environmental control of invasin expression in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is mediated by regulation of RovA, a transcriptional activator of the SlyA/Hor family. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1249–1269. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02522.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Revell PA, Miller VL. 2000. A chromosomally encoded regulator is required for expression of the Yersinia enterocolitica inv gene and for virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 35:677–685. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01740.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batzilla J, Antonenka U, Hoper D, Heesemann J, Rakin A. 2011. Yersinia enterocolitica palearctica serobiotype O:3/4: a successful group of emerging zoonotic pathogens. BMC Genomics 12:348. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukushima H, Nakamura R, Ito Y, Saito K, Tsubokura M, Otsuki K. 1983. Ecological studies of Yersinia enterocolitica. I. Dissemination of Y. enterocolitica in pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 8:469–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gürtler M, Alter T, Kasimir S, Linnebur M, Fehlhaber K. 2005. Prevalence of Yersinia enterocolitica in fattening pigs. J. Food Prot. 68:850–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukushima H, Nakamura R, Ito Y, Saito K, Tsubokura M, Otsuki K. 1984. Ecological studies of Yersinia enterocolitica. II. Experimental infection with Y. enterocolitica in pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 9:375–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nielsen B, Heisel C, Wingstrand A. 1996. Time course of the serological response to Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 in experimentally infected pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 48:293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayashidani H, Ohtomo Y, Toyokawa Y, Saito M, Kaneko K, Kosuge J, Kato M, Ogawa M, Kapperud G. 1995. Potential sources of sporadic human infection with Yersinia enterocolitica serovar O:8 in Aomori Prefecture, Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1253–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwata T, Une Y, Okatani AT, Kaneko S, Namai S, Yoshida S, Horisaka T, Horikita T, Nakadai A, Hayashidani H. 2005. Yersinia enterocolitica serovar O:8 infection in breeding monkeys in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 49:1–7. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03630.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pepe JC, Miller VL. 1993. The biological role of invasin during a Yersinia enterocolitica infection. Infect. Agents Dis. 2:236–241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mantle M, Pearson J, Allen A. 1980. Pig gastric and small-intestinal mucus glycoproteins: proposed role in polymeric structure for protein joined by disulphide bridges. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 8:715–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCormick BA, Nusrat A, Parkos CA, D'Andrea L, Hofman PM, Carnes D, Liang TW, Madara JL. 1997. Unmasking of intestinal epithelial lateral membrane beta1 integrin consequent to transepithelial neutrophil migration in vitro facilitates inv-mediated invasion by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 65:1414–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu B, Yin X, Feng Y, Chambers JR, Guo A, Gong J, Zhu J, Gyles CL. 2010. Verotoxin 2 enhances adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 to intestinal epithelial cells and expression of β1-integrin by IPEC-J2 cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4461–4468. 10.1128/AEM.00182-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jimenez-Marin A, Moreno A, de la Mulas JM, Millan Y, Morera L, Barbancho M, Llanes D, Garrido JJ. 2005. Localization of porcine CD29 transcripts and protein in pig cells and tissues by RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 104:281–288 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ricciardi ID, Pearson AD, Suckling WG, Klein C. 1978. Long-term fecal excretion and resistance induced in mice infected with Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect. Immun. 21:342–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pepe JC, Wachtel MR, Wagar E, Miller VL. 1995. Pathogenesis of defined invasion mutants of Yersinia enterocolitica in a BALB/c mouse model of infection. Infect. Immun. 63:4837–4848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paerregaard A, Espersen F, Skurnik M. 1991. Role of the Yersinia outer membrane protein YadA in adhesion to rabbit intestinal tissue and rabbit intestinal brush border membrane vesicles. APMIS 99:226–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.